Abstract

Nigerian gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) experience social marginalization, discrimination and violence due to their sexual orientation and same-sex attraction, which may affect mental health, substance use, and HIV sexual risk behavior. The goal of the current study was to conduct formative qualitative research to gain better understanding of these issues among GBMSM in Lagos, Nigeria. Face-to-face, semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted with 30 GBMSM in Lagos, Nigeria. Data were analyzed using a deductive content analysis approach. We found that Nigerian GBMSM experienced both general life stressors as well as proximal and distal sexual minority identity stressor, including rejection by family members and harassment and physical violence perpetrated by the general public and police officers. Participants described dealing with mental health problems within the context of family rejection, experienced stigma due to sexual orientation, and feelings of social isolation. Substance use was described as occurring within the context of social settings. Lastly, some participants mentioned that they engaged in risky sexual behavior while under the influence of alcohol and drugs. These findings call for comprehensive and innovative, GBMSM-affirming behavioral healthcare, substance cessation services, and innovative HIV prevention interventions specifically designed and tailored for Nigerian GBMSM.

Keywords: Minority Stress, GBMSM, Nigeria, Mental Health, Substance Use

Introduction

Nigerian gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) experience social marginalization, discrimination and violence due to their sexual orientation, same-sex attraction, and sexual activity (Allman et al., 2007; Melhado, 2015; Sekoni et al., 2015). These experiences may negatively impact the physical, mental, and sexual health (Makanjuola et al., 2018; Oginni et al., 2018; Ogunbajo, Oke, et al., 2019) of Nigerian GBMSM. A commissioned report on the human rights violations experienced by lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals in Nigeria between December 2017 and November 2018 found a total of 213 reported cases of battery, assault, arbitrary arrest/unlawful detention, mob attack, torture, threat to life, kidnapping, and forced evictions (TIERS, 2019). These incidents occurred within the context of the Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act (SSMPA), which was signed into law in January 2014 (Gladstone, 2014). While SSMPA primarily prohibits same-sex marriage, it further criminalizes the Nigerian LGBT community by prohibiting participation in civil organizations or events that “promote” homosexuality and by punishing sexual activity or public display of same-sex amorous relationships (Nwazuoke & Igwe, 2016). Experiencing discrimination—on the basis of gender identity and sexual orientation—may contribute to feelings of lower self-worth, impact one’s ability to cope, and has been shown to be associated with lower quality of life and maladaptive coping strategies among sexual and gender minority communities (Mays & Cochran, 2001; Omar Martinez et al.). For example, a study found that higher levels of internalized homophobia was associated with reduced reported quality of life among Nigerian GBMSM (Oginni et al., 2019). The culmination of experiences of prejudice, violence, and state-sanctioned discriminatory laws may worsen psychosocial health among Nigerian GBMSM.

Prior research has shown high prevalence of mental health problems—especially depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts—among African GBMSM (Ahaneku et al., 2016; Stahlman et al., 2016; Stoloff et al., 2013). While there is a dearth of literature on mental health outcomes among GBMSM in Nigeria, a few cross-sectional studies have shown high rates of mental health problems in this group. A study of GBMSM residing in Lagos and Abuja, Nigeria found that 29% of participants reported a history of suicidal ideation (Rodriguez-Hart et al., 2018). They also observed a dose-response relationship between lifetime experiences of enacted stigma (e.g., rejection from family and friends, physical violence, verbal harassment), felt stigma (fear of seeking healthcare), and suicidal ideation, with higher levels of stigma being associated with higher prevalence of suicidal ideation (Rodriguez-Hart et al., 2018). Another study found that Nigerian GBMSM—when compared to their heterosexual counterparts—were more likely to report having experienced parental neglect, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation (Oginni et al., 2018). A qualitative study that assessed the major sources of stress among Nigerian GBMSM found that they included concerns about physical safety, concealment of sexual orientation, and experiences of homophobia from healthcare providers (Makanjuola et al., 2018). All in all, empirical evidence demonstrate that Nigerian GBMSM experience a myriad of mental health problems, which might be exacerbated by societal antagonism and persecution perpetrated by societal prejudice.

Previous work show that GBMSM may engage in substance-using behaviors to cope with mental health problems (Bourne & Weatherburn, 2017; Feinstein & Newcomb, 2016). A systematic review on substance use among African GBMSM found that a prevalence of alcohol consumption ranging 50%−100% and that cannabis was the most frequently used substance, with a prevalence ranging from 8% to 29% (Sandfort et al., 2017). A study conducted among GBMSM in Lagos (N=320) found that 22% had a history of cigarette use, 15% were current smokers, and 37% of current smokers were heavy smokers (10+ cigarettes per day) (Odukoya et al., 2017). Additionally, 34% of the sample currently drank alcohol and 49% of current drinkers met CAGE criteria for problematic drinking (Odukoya et al., 2017). Lastly, a study of GBMSM in Lagos, Nigeria found that 57% currently consumed alcohol, 58% of those who consumed alcohol drank to get drunk, 11% reported hard drug use, with about a third (34%) reporting using cocaine use (Sekoni et al., 2015). These studies provide evidence that substance use is common among Nigerian GBMSM, which has implications for physical and mental health outcomes among this vulnerable group

Nigerian GBMSM bear a disproportionately higher burden of HIV, with an estimated prevalence of 11–35% (Vu et al., 2013). A study found that national HIV prevalence has steadily increased among Nigeria GBMSM, from 14% in 2007 to 17% in 2010 to 23% in 2014 (Eluwa et al., 2019). Factors associated with HIV seropositivity include being 25 years or older, engaging in receptive anal sex in the past 6 months, and self-reported symptoms of sexually transmitted infections in the past 6 months (Eluwa et al., 2019). Additionally, Nigerian GBMSM report avoidance of healthcare settings, lack of safe social spaces, and experiences of blackmail, physical and verbal harassment, all of which can impact utilization of HIV prevention services including routine testing and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), as well as treatment engagement for those living with HIV, contributing to increased GBMSM population-level HIV vulnerability (Schwartz et al., 2015).

Study Aims

To the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies among Nigerian GBMSM that examine how negative experiences (e.g., harassment, discrimination, violence, etc.) brought on as a consequence of identifying or being perceived as a sexual minority influences psychological distress and substance use, which in turn may potentiate HIV spread. The specific aim of the current study was to explore how experiences of minority stress impact mental health problems, substance use, and vulnerability to HIV infection among GBMSM in Lagos, Nigeria. Understanding these relationships will be helpful for designing successful intervention programs to improve mental health, reduce substance use behavior, and sexual risk taking among this marginalized group.

Theoretical Framing

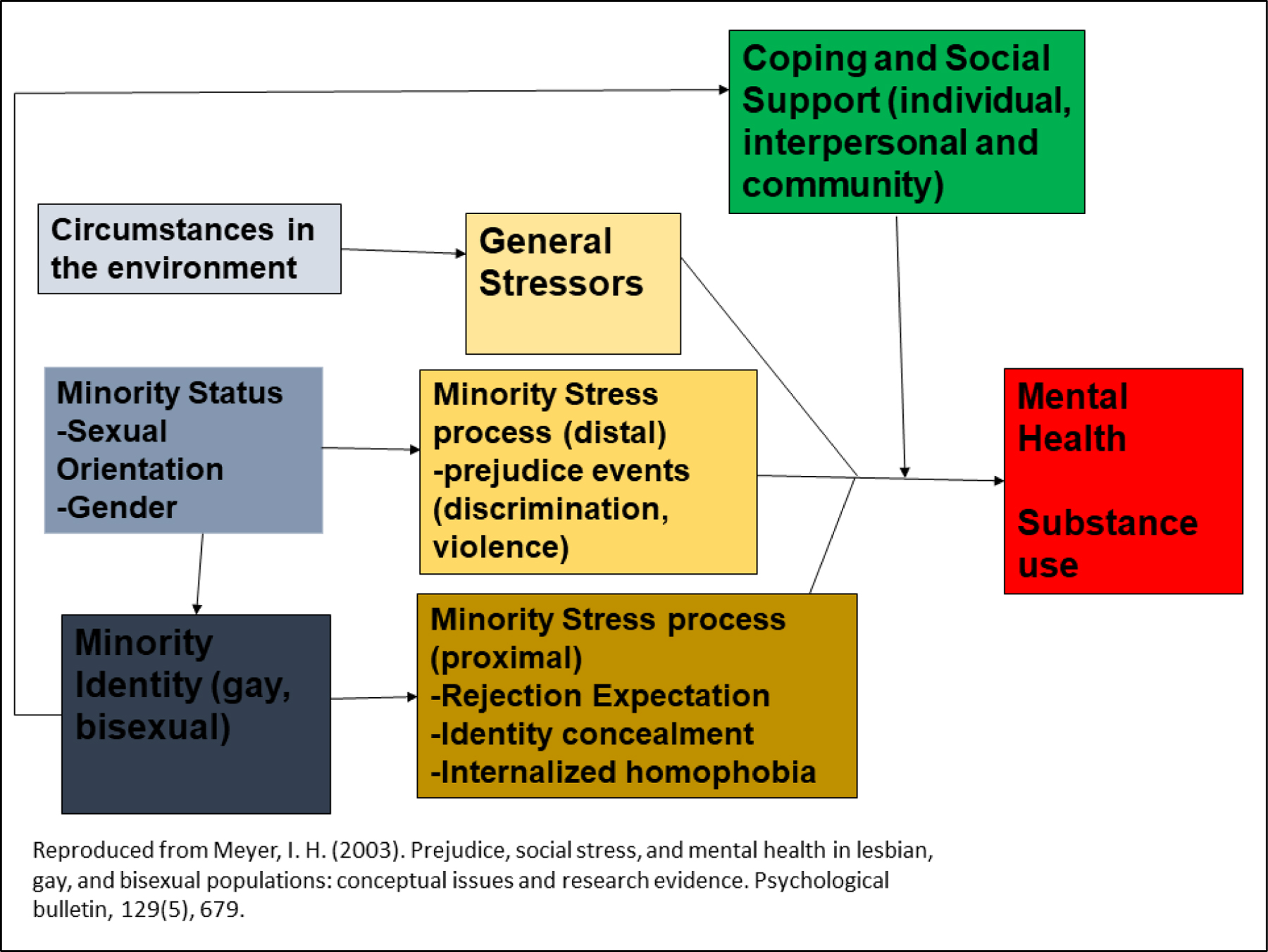

We applied the Meyer minority stress model (I. H. Meyer & D. M. Frost, 2013) as a conceptual framework to inform the interview guide development and thematic analysis of the current study. The minority stress model (Figure 1) proposes that the prejudice, discrimination, and stigma experienced by LGBT individuals cause them to experience higher levels of stress, compared to their heterosexuals counterparts, and that this increased stress, uniquely experienced by LGBT people, contributed to adverse health outcomes including mental illness (I. H. Meyer & D. Frost, 2013).

Figure 1:

Minority Stress Model (Meyer, 2003)

Methods

Sample

Between June and August 2017, we recruited thirty GBMSM residing in Lagos, Nigeria to participate in face-to-face, semi-structured interviews to explore their experiences with minority stress, mental health, substance use, and HIV sexual risk, followed by a brief demographic questionnaire. Eligibility criteria included: 1) being 18 years of age or older, 2) reporting a history of sex with another birth-assigned male, and 3) currently residing in Lagos. Participants were recruited through a local community-based organization (CBO) that provides sexual health services to GBMSM in Lagos (Centre for the Right to Health). Outreach workers and peer educators at the CBO shared information about the study with the target population during programming events and provided study contact information to individuals who were interested.

Study Procedures

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to conducting any study procedures. All participants were assigned unique identifier numbers and no identifying information was collected to maintain confidentiality. Semi-structured interviews were conducted in private offices of the CBO. The first author and a team of 3 trained qualitative researchers based in Nigeria carried out all study procedures. Interviews were conducted entirely in English and digitally recorded. Interviews ranged in duration between 1–1.5 hours. Informed by the Minority Stress Model, the interview guide was initially drafted by the first author and reviewed by the authorship team. The interviews explored topics including: cultural context and lived experiences of GBMSM in Nigeria, substance use (typology, motivations, and consequences), mental health (past experiences with mental illness and factors influencing mental illness), access to substance use and mental health services, and resilience. We also collected data on demographic characteristics, mental health, substance use, and sexual risk from all participants. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards at Brown University and the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research. Upon completion of the interview, participants were compensated in Nigerian naira with the equivalence of ten U.S. dollars ($10).

Data Analysis

The data analysis was informed by constructs in the minority stress model and coded data were organized into higher-level themes through a deductive approach (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). All transcripts were organized and analyzed using NVIVO 12 software. First, the lead author read through the transcripts and documented how the emerging themes matched on to constructs in the minority stress model. Next, we developed a draft codebook from the preliminary analysis and the semi-structured interview guide. This codebook was shared with the study team for feedback and revised accordingly. Next, we coded all transcripts with the final codebook and new codes were added as needed. After initial coding was completed, 10% of randomly selected transcripts were double coded by a second senior research investigator. Coding disagreements were discussed by both coders and recoded upon consensus.

Results

Participant Demographics

Sample demographics are presented in Table 1. The average age of participants was 27.9 years. A majority of participants had some college education or higher (73%), self-identified as gay/homosexual (73%), and reported being single (70%). 63% of participants were currently employed and 40% self-reported being HIV-positive.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Sample (N = 30).

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 27.1 | 4.9 |

|

| ||

| Number of male sexual partners in past month | 2.4 | 2.2 |

|

| ||

| N | % | |

|

|

||

| Education | ||

| Less than University | 8 | 26.7 |

| Some University or higher | 22 | 73.3 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Gay/Homosexual | 22 | 73.3 |

| Bisexual | 8 | 26.7 |

| Relationship Status | ||

| Single, never married | 21 | 70.0 |

| Currently in a relationship | 9 | 30.0 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Currently employed | 19 | 63.3 |

| Currently unemployed | 11 | 36.7 |

| HIV Status | ||

| Negative/Unknown | 18 | 60.0 |

| Positive | 12 | 40.0 |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (lifetime) | ||

| Yes | 23 | 76.7 |

| No | 7 | 23.3 |

| Depressive Symptoms (past week) | ||

| Yes | 18 | 60.0 |

| No | 12 | 40.0 |

| Hazardous drinking (past 3 months) | ||

| Yes | 15 | 50.0 |

| No | 15 | 50.0 |

| Any history of sexually transmitted infection | ||

| Yes | 16 | 53.3 |

| No | 14 | 46.7 |

| Exchange Sex (lifetime) | ||

| Yes | 15 | 50.0 |

| No | 15 | 50.0 |

Mental Health, Substance Use, and Sexual Risk

A majority of the sample (77%) met criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (Cameron & Gusman, 2003) and 60% had clinically significant depressive symptoms . Half of the sample were indicated for possible hazardous drinking.

More than half (53%) of the sample reported a history of sexually transmitted infection diagnosis. The mean number of male sexual partners in the past month ranged was 2.4 (SD=2.2) and 50% reported a history of exchange sex.

Qualitative Findings

General Stressors

Most participants identified lacking adequate financial resources to support everyday expenses as a major general stressor. This includes the inability to secure a steady job, pay for housing and related utilities (such as electricity, water, etc.) and fulfill other financial responsibilities:

“Having an apartment, once they bring the electricity bill, I think ‘how am I going to pay the bill?’, ‘how am I going to come up with the rent and all that stuff without a steady job?’, it has always been an issue that is stressing, so I keep squatting with people for me to dodge those responsibilities.” 30-year-old gay man

For many participants, financial stressors were related to their sexual and gender identity living in Nigeria. Many participants described actively looking for employment opportunities with the goal of attaining financial independence but encountering obstacles due to discriminatory employment practices on the basis of sexual orientation:

“Getting a job in Nigeria is hard because if you are the feminine type and you go for an interview, they won’t want to pick you because of your sexuality. They won’t want to mingle with you because of your sexuality. It causes me a lot of stress.” 23-year-old gay man

A vast majority of participants described experiencing stress due to the daily navigation of hostile environments created by societal unacceptance of their sexual orientation and inability to freely express themselves:

“It has really been so challenging and stressful. As long as you are gay in a society like Nigeria where you’re not being accepted for being who you are… you’re not being celebrated for being who you are. It has been full of challenges, growing up as a gay man on a daily basis… I’m being bullied and insulted and it has been dehumanizing.” 33-year-old gay man

Minority Stress processes (distal): Prejudice events (discrimination, violence)

Participants discussed various experiences of prejudice (i.e., discrimination and violence because of their sexual orientation or gender identity) on a regular basis by family members, strangers, and police officers. These prejudicial acts occurred where GBMSM socialized or isolated events where individual GBMSM were targeted due to suspicion of them being gay:

“The last party we did, some straight guys were there, but they started fighting us because we were gay and I had to stand up to them.’” 34-year-old gay man

Another participant described prejudicial treatment from his family members due to his sexual orientation:

“My family, they don’t use the plate I use when eating, Me and my elder brothers, we share clothes, whenever I wear the cloth, they go and wash their clothes and they don’t want anything to do with me. They don’t even call, they don’t check up on me, they don’t want to know where I am.” 36-year-old bisexual man

Lastly, several participants described police harassment and discrimination, which were often tied to being perceived as homosexual or not conforming to male gender expectations, resulting in arrest and bribes in exchange for release from police custody:

“I was assaulted by police. The policeman wanted to see my phone. I said ‘you cannot see my phone’. He took me to the vehicle. He said he wanted to see my phone. I said ‘you cannot see my phone, are you the one that bought it for me?’. He said, ‘I know you’re a gay and I want to see your phone.’ From there they took me to their holding cell and I called for someone to come and bail me out.” 23-year-old gay man

Minority Stress processes (proximal): Expectations of rejection, concealment, internalized homophobia

Participants described experiencing proximal stressors, including expectations of rejection, concealment of their same sex attraction, and internalized homophobia, as described in the minority stress model.

Expectations (and experiences) of Rejection

Several participants expressed expectations of rejections from their family members, familiar acquaintances and complete strangers. They expected to be rejected due to other people’s perception of their sexual orientation, being viewed as too feminine, or not conforming to the gender norms expected of a male in modern day Nigerian society. This 23-year-old gay participant described being cautious of where to socialize due to fear of being rejected because of his sexuality:

“I have to watch where I go and who I associate with because I fear they will reject me because of who I am. I can’t hang out in a beer parlor because maybe a straight guy will perceive me as gay. We might exchange words. I never know what will end up happening so I just avoid it all together.”

Another participant described rejection by family members due to them becoming aware of his same-sex attraction:

“My family is aware that I am attracted to men and they rejected me. My rights were taken from me. I was not recognized as human being. I was recognized as a taboo. I was rejected and I left home.” 36-year-old bisexual man

Due to the stress of dealing with the daily struggles of harassment and persecution for being perceived as gay, a few participants described concealing their sexual orientation to avoid any potentially harmful encounters. This was often achieved by wearing clothing perceived to be “masculine”, self-regulating mannerism to conform to those perceived to be more traditionally masculine, and being discreet in both public and private spaces:

“I am trying to curtail myself to what I am not. When going out I have to wear all those excesses baggage that make me masculine, and sometimes it’s mentally disturbing.” 23-year-old gay man

Another participant described experiences with a friend who went to extreme lengths to conceal his sexual orientation from family members while remaining active within the gay community:

“I have a friend, whenever he wants to meet me, he will say I should not come to his house, he did not want people to think he is still in the ‘game’, he told everyone he is not doing anymore, but he still comes to parties and has sex with guys. He is hiding his sexual orientation.” 26-year-old gay man

Lastly, a participant detailed how he had to behave less feminine to avoid being accosted, harassed, and possibly arrested by police:

“As a gay man I have to deprive myself of feminine behavior. The police could arrest me for being a bit girly. If I walk like a man, I might not be disturbed. Once, I became a bit of the girly in physique and characteristics, I got attacked and called names. Those of us who have this girly physique, we get into problems at all times whether we go out or hide ourselves, they still come to us, humiliating us and fighting us.” 24-year-old gay man

A few participants described how the negative experiences—due to identifying as a GBMSM in Nigeria—made them wish they weren’t gay (internalized homophobia). This participant described wishing he was born straight and the mental toll his experiences as a gay man in Nigeria has taken on him:

“If I chose sexuality at the point of conception, I will have chosen to be straight because I would not want to go through all these things. I have tried committing suicide so many times. I am seeing a mental health counselor.” 23-year-old gay man

Coping and social support

Despite being confronted with the daily stressors of being a sexual minority in Nigeria, many participants described exhibiting resilience and adapting coping strategies. Resilience was described by several participants as having a sense of worth and pride in one’s identity, in spite of negative experiences and social isolation:

“My half-sisters and half-brothers neglect and insult me. Some talk about me so badly, ‘he’s a gay! The only son is a gay! I start thinking ‘am I not human?’ But I don’t let anything depress me, to hold me down.” 25-year-old gay, male

Also, several participants mentioned getting social support primarily from other members of the GBMSM community, who served as a support system especially during hard times:

“I go to my friend’s house, they are within my community, I feel happy whenever I wake up and see them that we are all together, I feel happy, that’s what keeps me alive.” 25-year-old gay man

Mental Health

Most participants discussed a history of dealing with mental health problems including depression, anxiety, social withdrawal, suicide thoughts and suicide attempts. These mental health problems were discussed within the context of lack of societal acceptance of homosexuality, family rejection, experienced stigma due to sexual orientation, and feelings of social isolation.

Depression was the most discussed mental health condition during our interviews. Participants vividly described feeling depressive symptoms as a result of not being able to fully live their truth as sexual minorities in Nigeria and having to deal with the stigma and violence they were confronted with on a daily basis:

“Whenever I’m home alone, I feel depressed. When I’m with my straight friends, I feel like they are living the lives they want to live, no one accuses them of doing bad or good but me, people stigmatize me, they put me aside and say that what I’m doing is so bad” 29-year-old bisexual man

Many participants explained experiencing anxiety, characterized by a fear of an immediate and imminent danger of which they could not provide a logical explanation:

“I’m the kind of person that forgets things easily, I can’t sleep, I live in fear that I might die at any time.” 36-year-old bisexual man

Several participants mentioned withdrawing themselves from people and social settings that they engaged with in the past. This occurred as a result of feelings of isolation and the inability to express themselves in a judgmental society:

“Sometimes I withdraw, I don’t want to talk to anybody even if I’m dying inside I don’t want to talk about it, I don’t want to see anybody. Because of that I start to neglect myself. It is because my lifestyle is not accepted and I cannot discuss it with anybody” 32-year-old gay man

Lastly, a few participants described having suicidal thoughts and having attempted suicide:

“When I’m walking down the street, people call me several names. I had a bad childhood. Sometimes I wanted to hang myself up.” 26-year-old gay man

“I decided to kill myself. I drank kerosene… It didn’t work. I drank IZAL (disinfectant) and started having running stomach. Thank God some people came in at that moment. They gave me Oralite. I was rushed to the hospital.” 27-year-old gay man

Substance Use

Several themes emerged around alcohol and drug use. These themes are subcategorized into context of substance use (alcohol and recreational drugs), reasons for substance use, substance use within the context of sexual experiences, and sexual risk-taking due to substance use behavior.

Context of Alcohol Use

The majority of participants described alcohol use within the context of social gathering with friends both in private and public settings. Many characterized themselves as social drinkers and would consume alcohol during celebratory events at someone’s private residence or during social outings at clubs or bars:

“I normally go out clubbing with my community people, few of us will drink while the other ones will just have fun, I drink a lot” 34-year-old gay man

In contrast, a few participants described solitary alcohol use as a way of dealing with specific life stressors:

“I was by myself, I just need to relax and get away from all the troubles and all

the worries, I will drink some alcohol and sleep off.” 27-year-old bisexual man

Context of Recreational Drug Use

Similar to alcohol use, most participants described recreational drug use occurring in social settings. Additionally, drug use was often reported to occur together with alcohol use:

“During the parties, we buy drinks and drugs like codeine, marijuana and tramadol and share it together.” 29-year-old gay man

Some participants described attending social events with other GBMSM and subsequently engaging in recreational drug use:

“Sometimes community members have a party and it is strictly for people who use drugs and alcohol. If you don’t drink alcohol sit in your house. So since then I started using drugs and its now part of me. Without taking drugs I cannot be myself.” 23-year-old gay man

Reasons for Alcohol Use

Participants provided an array of reasons for alcohol use. They included: coping with stress and to achieve relaxation, feeling happier, conforming to gender expectations, and improving self-esteem.

Several participants described consuming alcohol to cope with stressful life events:

“I had issues at my place of work, I was so mad with myself, I regretted what happened. I went back home I drank vodka and because I felt like the world was over. There was nothing I could do so I drank.” 37 years old, bisexual

Some participants discussed drinking alcohol to feel happy, particularly during times when they felt down:

“Alcohol makes me feel happier, I might be angry now but as soon as go to a nearby bar and begin to drink beer, I will begin to remember the good times and it makes me feel good.” 30-year-old bisexual man

A few participants mentioned drinking alcohol to conform to cultural expectations of men within Nigerian society. To avoid being suspected as gay or feminine, this participant drank alcohol:

“I was with a couple of straight friends and I asked for malt (non-alcoholic drink) and the guy asked me ‘are you a lady?’ I said ‘ok, let me have beer instead.’ I didn’t want them to think that I was feminine or gay.” 30-year-old gay man

One participant mentioned personally dealing with low self-esteem and using alcohol as an aid to stay actively engaged in social situations:

“I have low self-esteem. To look at people straight in their eyes and say what I want to say. I can’t face a crowd without drinking.” 23-year-old gay man

Reasons for Recreational Drug Use

Reasons for recreational drug use included: for social belongingness, to improve self-esteem, and for coping with problems.

Several participants described using recreational drugs as an outward expression of social group membership. Many mentioned a desire to feel accepted while occupying social spaces with other GBMSM and this was achieved through engaging in communal recreational drug use:

“When you go to a party, you want to show them that you belong. You want to show them that you take drugs. You do things that you don’t want to do.” 27-year-old gay man

Some participants noted that they engaged in recreational drug use to help boost their self-esteem. Many attributed their low self-esteem to the negative and hurtful messages they had heard about GBMSM:

“Some people say: ‘this guy is gay, they are animals and devils, they are evil’, I started thinking about it and started having low self-esteem, so I started taking marijuana, it helps boost me up.” 25-year-old gay man

A few participants mentioned that recreational drug were used to cope with difficult situation, in line with the sentiments expressed for alcohol usage:

“The major reason for using drug is maybe I have something that is bothering me, and I can’t control it, I look for something to take it off my mind.” 32-year-old gay man

Substance Use and Sexual Risk

Participants reported engaging in sexual behavior while using alcohol and/or recreational drugs. The reasons for substance use during sex were to: reduce pain during sex, heighten sexual pleasure, and tolerate sex with an undesirable partner. Several participants described engaging in condomless anal sex and group sex, while under the influence of substances.

Several participants described alcohol usage and/or recreational drug use to help ease the pain associated with engaging in bottoming (receptive anal intercourse):

“Before sex, I’ll ask the person ‘do you have a big dick?’ if he says ‘yes,’ then I’ll go to the bar to have a smoke, take some drinks just to make me high, so I won’t feel the pain.” 34-year-old gay man

Some participants noted that substances were utilized with sex to heighten the sexual experience:

“Sex without alcohol and drugs is not enjoyable and not memorable. But when I have it with drugs, I go crazy, I do something that I don’t want to do, styles that I have not done before.” 23-year-old gay man

A few participants used substances during sex to tolerate sex with an undesirable sexual partner:

“When I come across a partner I don’t like so well, or I’m not really up for and I just have to do it. If I want to get the thought of the person I am having sex with off my mind, I drink alcohol.” 23-year-old gay man

Several participants described engaging in sexual risk behavior while under the influence of alcohol and other drugs. They describe the inability to make conscious decisions about condom use due to being too drunk or high on drugs:

“Sometimes when you are on it (drugs), maybe you are high, and having sex with your partner, the first time you use a condom. The second time you are high and you don’t know what you are doing, you won’t use a condom anymore.” 25-year-old gay man

“There were about 16 of us in one room. We invited some guys over for sex. One guy brought some drugs for us to us. I didn’t know the name [of the drug]. I kept asking them what we were taking. They said, ‘it’s what’s going to make us high.’ We started having sex from there all night. To be honest, I don’t remember us using condoms since we were all high.” 29-year-old gay man

Discussion

In this study, we examined the interconnectedness of minority stress, mental health, substance use, and HIV sexual risk among Nigerian GBMSM. We found that Nigerian GBMSM experienced general life stressors and proximal and distal stressors tied to their sexual orientation and gender expression. Despite these stressors, participants identified resilience factors and social support systems that helped them cope with stressful situations. Various mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts were discussed within the context of family rejection, experienced stigma due to sexual orientation, and feelings of social isolation. Substance use was described within the context of social settings and utilized both for personal and social reasons. Lastly, participants noted engaging in risky sexual behavior due to substance use.

In discussing minority stress experiences (general, proximal and distal), Nigerian GBMSM provided personal accounts of experiencing various types of prejudicial events due to their sexual orientation and exhibiting identity concealment and anticipated stigma in response to these experiences. These findings are consistent with prior research that has demonstrated that experience of minority stress is common among GBMSM (Hamilton & Mahalik, 2009; Lewis et al., 2003; McAdams-Mahmoud et al., 2014). General life stressors coupled with stress as a result of one’s sexual orientation might exacerbate the stress load of GBMSM in Nigeria and further drive proliferation of negative mental health outcomes. Additionally, accounts of unlawful police harassment, arrests, and extortion further demonstrates how discriminatory laws, such as SSMPA, might further contribute to the marginalization of sexual minority populations. It is imperative that community members are educated on their legal rights as Nigerian citizens, especially in situations that involve law enforcement officials.

Despite experiencing discrimination and prejudice, participants reported being resilient and having sources of social support. It is important that community-based organizations and healthcare providers who interact with Nigerian GBMSM help identify coping strategies to deal with stress as a result of homophobia and living in a hostile society. Interventions that help community members build coping skills and strategies and support networks are desperately needed. These interventions should be conceptualized, developed, and implemented in consultation with key stakeholders while centering and prioritizing the needs of Nigeria GBMSM. A study of mental health providers with expertise in gay and bisexual men’s mental health and gay and bisexual men identified important interventions elements that might be effective in reducing minority stress and mental health problems among gay and bisexual men (Pachankis, 2014). They found that facilitating supporting relationships, affirming sexual minority identity, validating the unique strengths and resiliency of sexual minority men, amongst other things, were important to reducing impacts of minority stress on mental health of gay and bisexual men (Pachankis, 2014). This work could serve as a framework for the development of an adapted intervention to reduce the effects of minority stress on the mental health of Nigerian GBMSM.

We found high levels of mental health problems as a result of negative experiences due to their sexual orientation. These findings offer qualitative evidence on the theoretical association between minority stress and psychological distress as demonstrated in the Meyer minority stress model (I. H. Meyer & D. M. Frost, 2013). This is consistent with various studies that have shown an association between minority stress and negative psychosocial mental health outcomes among GBMSM (Bostwick et al., 2014; Kelleher, 2009; Lewis et al., 2003; McAdams-Mahmoud et al., 2014). Our study adds to the existing literature by providing insight into the unique experiences of Nigerian GBMSM. These findings suggest the need for comprehensive, GBMSM-affirming behavioral health interventions specifically tailored for Nigerian GBMSM. These interventions should help community members identify sources of stress, how they impact their mental health, and brainstorm solutions to reduces their effects. A randomized control trial of cognitive-behavioral treatment for gay and bisexual men in the United States found a significant reduction in depressive symptoms, substance use, sexual compulsivity, and increased condom use efficacy in the treatment group compared to the waitlist group (Pachankis et al., 2015). These findings provide evidence for how mental health interventions can improve outcomes across the minority stress model, including mental health, substance use, and sexual risk.

In this study, participants described using substances as a result of poor mental health and experiencing minority stress, including to cope with negative life experiences and to improve self-esteem. These findings are in line with previous studies that have found experiences of minority stress are associated with substance use behavior among GBMSM (Goldbach et al., 2014; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008). These findings illuminate the need for substance use disorder treatment providers who are sensitive to the lived experiences of GBMSM, especially in Nigeria. Interventions that aim to reduce substance use among Nigeria should draw from the scientific literature for evidence-based approaches while tailoring the intervention to the everyday realities of being GBMSM in Nigeria. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of gay-specific cognitive therapy in reducing substance abuse among GBMSM found a significant and sustained reduction in substance use behavior (Shoptaw et al., 2008). This suggests that tailoring substance use treatment programs to the unique needs and circumstances of GBMSM might result in significant decrease in substance use.

Additionally, substance use was described within the context of sexual risk, specifically engaging in condomless anal sex and group sex. Previous studies among African GBMSM have found substance use behavior being strongly associated with HIV sexual risk among African GBMSM (Lane et al., 2008; Ogunbajo, Oke, et al., 2019). This finding has major implications for HIV prevention and treatment programming for Nigerian GBMSM, especially since HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis is not widely available in Nigeria but has been demonstrated to be highly acceptable among African GBMSM (Ogunbajo, Iwuagwu, et al., 2019; Ogunbajo, Kang, et al., 2019; Ogunbajo, Leblanc, et al., 2019). It is important that HIV prevention programs for Nigerian GBMSM include services related to substance use disorders and mental health. Additionally, integrated health interventions aimed at reducing substance use, improving mental health and decreasing HIV sexual risk among GBMSM have been proven to be highly effective (Lauby et al., 2017; Reback et al., 2019). Consequently, engagement in these auxiliary services might both improve mental health and substance use behavior and reduce HIV sexual risk.

This study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Participants were recruited though community-based organizations and snowball sampling. Consequently, the findings of this study may not be generalizable to Nigerian GBMSM who may not be engaged with these CBOs. However, with purposive sampling, we recruited a sample that was diverse across ethnic groups, sexual orientation, education level, HIV status, and religious affiliation. Secondly, participants were relatively young (mean age = 27.9 years), which might exclude the experiences of older Nigerian GBMSM. While we attempted to recruit GBMSM who were older than 30 years, we found that they did not frequently seek services or attend programming events organized by our partner CBO. Thirdly, the study was conducted in Lagos, Nigeria, thereby limiting the generalizability of the results to other regions of Nigeria. However, since the implementation of this study, we have conducted a subsequent quantitative that sampled GBMSM from four different states in Nigeria.

Despite these limitations, this is the first known study to examine the interconnectedness of minority stress, mental health, substance use, and HIV sexual risk taking among Nigerian GBMSM. Our findings underscore the importance of developing community informed, evidence-based health interventions aimed at reducing the effect of minority stress on mental health problem, substance use, and HIV sexual risk behavior, in order to improve the overall health and quality of life for Nigerian GBMSM.

Acknowledgments

We will like to thank all the participants of the study for their time and efforts. We would also like to thank the staff at Centre for Right to Health (Abuja) Equality Triangle Initiative (Delta), Improved Sexual Health and Rights Advocacy Initiative (ISHRAI, Lagos) and Hope Alive Health Awareness Initiative (Plateau). We also extend our gratitude to Olubiyi Oludipe (ISHRAI), Bala Mohammed Salisu (Hope Alive Health Awareness Initiative), Chucks Onuoha, Prince Bethel, Eke Chukwudi, Tochukwu Okereke, Josiah Djagvidi, and Odi Iorfa Agev, for providing logistical support to the project. This work was supported by grant R36 DA047216 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (PI: Adedotun Ogunbajo), and the Robert Wood Johnson Health Policy Research Scholars Program. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Dr. Sandfort’s contribution to this work was supported by grant P30-MH43520.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest Statement

There are no potential conflict of interest to report.

References

- Ahaneku H, Ross MW, Nyoni JE, Selwyn B, Troisi C, Mbwambo J, Adeboye A, & McCurdy S (2016). Depression and HIV risk among men who have sex with men in Tanzania. AIDS care, 28(sup1), 140–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allman D, Adebajo S, Myers T, Odumuye O, & Ogunsola S (2007). Challenges for the sexual health and social acceptance of men who have sex with men in Nigeria. Culture, health & sexuality, 9(2), 153–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, West BT, & McCabe SE (2014). Discrimination and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(1), 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne A, & Weatherburn P (2017). Substance use among men who have sex with men: patterns, motivations, impacts and intervention development need. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 93(5), 342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron RP, & Gusman D (2003). The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Primary care psychiatry, 9(1), 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Eluwa GI, Adebajo SB, Eluwa T, Ogbanufe O, Ilesanmi O, & Nzelu C (2019). Rising HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Nigeria: a trend analysis. BMC public health, 19(1), 1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, & Newcomb ME (2016). The role of substance use motives in the associations between minority stressors and substance use problems among young men who have sex with men. Psychology of sexual orientation and gender diversity, 3(3), 357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fereday J, & Muir-Cochrane E (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International journal of qualitative methods, 5(1), 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone R (2014). Nigerian President signs ban on same-sex relationships. The New York Times.

- Goldbach JT, Tanner-Smith EE, Bagwell M, & Dunlap S (2014). Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: A meta-analysis. Prevention Science, 15(3), 350–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton CJ, & Mahalik JR (2009). Minority stress, masculinity, and social norms predicting gay men’s health risk behaviors. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(1), 132. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Erickson SJ (2008). Minority stress predictors of HIV risk behavior, substance use, and depressive symptoms: results from a prospective study of bereaved gay men. Health Psychology, 27(4), 455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher C (2009). Minority stress and health: Implications for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) young people. Counselling psychology quarterly, 22(4), 373–379. [Google Scholar]

- Lane T, Shade SB, McIntyre J, & Morin SF (2008). Alcohol and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men in South African township communities. AIDS and Behavior, 12(1), 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauby J, Zhu L, Milnamow M, Batson H, Bond L, Curran-Groome W, & Carson L (2017). Get real: evaluation of a community-level HIV prevention intervention for young MSM who engage in episodic substance use. AIDS Education and Prevention, 29(3), 191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Derlega VJ, Griffin JL, & Krowinski AC (2003). Stressors for gay men and lesbians: Life stress, gay-related stress, stigma consciousness, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 22(6), 716–729. [Google Scholar]

- Makanjuola O, Folayan MO, & Oginni OA (2018). On being gay in Nigeria: Discrimination, mental health distress, and coping. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 22(4), 372–384. [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, & Cochran SD (2001). Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American journal of public health, 91(11), 1869–1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams-Mahmoud A, Stephenson R, Rentsch C, Cooper H, Arriola KJ, Jobson G, De Swardt G, Struthers H, & McIntyre J (2014). Minority stress in the lives of men who have sex with men in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of homosexuality, 61(6), 847–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melhado L (2015). In Nigeria, anti-gay law associated with increased stigma and discrimination. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 41(3), 167. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, & Frost D (2013). Minority stress and the health of sexual minorities. Handbook of psychology and sexual orientation, 252–266.

- Meyer IH, & Frost DM (2013). Minority stress and the health of sexual minorities. Handbook of psychology and sexual orientation, 252–266.

- Nwazuoke AN, & Igwe CA (2016). A Critical Review of Nigeria’s Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act. JL Pol’y & Globalization, 45, 179. [Google Scholar]

- Odukoya OO, Sekoni AO, Alagbe SO, & Odeyemi K (2017). Tobacco and Alcohol Use among a Sample of Men who have Sex with Men in Lagos state, Nigeria. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research, 7(1), 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Oginni OA, Mapayi BM, Afolabi OT, Obiajunwa C, & Oloniniyi IO (2019). Internalized Homophobia, Coping, and Quality of Life Among Nigerian Gay and Bisexual Men. Journal of homosexuality, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Oginni OA, Mosaku KS, Mapayi BM, Akinsulore A, & Afolabi TO (2018). Depression and associated factors among gay and heterosexual male university students in Nigeria. Archives of sexual behavior, 47(4), 1119–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunbajo A, Iwuagwu S, Williams R, Biello K, & Mimiaga MJ (2019). Awareness, willingness to use, and history of HIV PrEP use among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Nigeria. PloS one, 14(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunbajo A, Kang A, Shangani S, Wade RM, Onyango DP, Odero WW, & Harper GW (2019). Awareness and Acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) in Kenya. AIDS care, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ogunbajo A, Leblanc NM, Kushwaha S, Boakye F, Hanson S, Smith MD, & Nelson LE (2019). Knowledge and Acceptability of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Ghana. AIDS care, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ogunbajo A, Oke T, Jin H, Rashidi W, Iwuagwu S, Harper GW, Biello KB, & Mimiaga MJ (2019). A syndemic of psychosocial health problems is associated with increased HIV sexual risk among Nigerian gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM). AIDS care, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Omar Martinez J, Wilson K, & Arreola S High Prevalence of Social and Structural Syndemic Conditions Associated with Poor Psychological Quality of Life Among a Large Global Sample of Gay, Bisexual and Other Men who Have sex with Men. Oceania, 88, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE (2014). Uncovering clinical principles and techniques to address minority stress, mental health, and related health risks among gay and bisexual men. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 21(4), 313–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Rendina HJ, Safren SA, & Parsons JT (2015). LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 83(5), 875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reback CJ, Fletcher JB, Swendeman DA, & Metzner M (2019). Theory-based text-messaging to reduce methamphetamine use and HIV sexual risk behaviors among men who have sex with men: Automated unidirectional delivery outperforms bidirectional peer interactive delivery. AIDS and Behavior, 23(1), 37–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Hart C, Bradley C, German D, Musci R, Orazulike I, Baral S, Liu H, Crowell TA, Charurat M, & Nowak RG (2018). The Synergistic Impact of Sexual Stigma and Psychosocial Well-Being on HIV Testing: A Mixed-Methods Study Among Nigerian Men who have Sex with Men. AIDS and Behavior, 22(12), 3905–3915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandfort TG, Knox JR, Alcala C, El-Bassel N, Kuo I, & Smith LR (2017). Substance use and HIV risk among men who have sex with men in Africa: a systematic review. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999), 76(2), e34–e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SR, Nowak RG, Orazulike I, Keshinro B, Ake J, Kennedy S, Njoku O, Blattner WA, Charurat ME, & Baral SD (2015). The immediate effect of the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act on stigma, discrimination, and engagement on HIV prevention and treatment services in men who have sex with men in Nigeria: analysis of prospective data from the TRUST cohort. The lancet HIV, 2(7), e299–e306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekoni AO, Ayoola OO, & Somefun EO (2015). Experiences of social oppression among men who have sex with men in a cosmopolitan city in Nigeria. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, NZ), 7, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S, Reback CJ, Larkins S, Wang P-C, Rotheram-Fuller E, Dang J, & Yang X (2008). Outcomes using two tailored behavioral treatments for substance abuse in urban gay and bisexual men. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 35(3), 285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahlman S, Grosso A, Ketende S, Pitche V, Kouanda S, Ceesay N, Ouedraogo HG, Ky-Zerbo O, Lougue M, & Diouf D (2016). Suicidal ideation among MSM in three West African countries: associations with stigma and social capital. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 62(6), 522–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoloff K, Joska JA, Feast D, De Swardt G, Hugo J, Struthers H, McIntyre J, & Rebe K (2013). A description of common mental disorders in men who have sex with men (MSM) referred for assessment and intervention at an MSM clinic in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 17(1), 77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIERS. (2019). 2018 Report on Human Rights Violations based on Real or Perceived Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Nigeria 1–40.

- Vu L, Adebajo S, Tun W, Sheehy M, Karlyn A, Njab J, Azeez A, & Ahonsi B (2013). High HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Nigeria: implications for combination prevention. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 63(2), 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]