Abstract

Nathan H. Azrin (1930–2013) contributed extensively to the fields of experimental and applied behavior analysis. His creative and prolific research programs covered a wide range of experimental and applied areas that resulted in 160 articles and several books published over a period of almost 6 decades. As a result, his career illustrates an unparalleled example of translational work in behavior analysis, which has had a major impact not only within our field, but across disciplines and outside academia. In the current article we present a summary of Azrin’s wide ranging contributions in the areas of punishment, behavioral engineering, conditioned reinforcement and token economies, feeding disorders, toilet training, overcorrection, habit disorders, in-class behavior, job finding, marital therapy, and substance abuse. In addition, we use scientometric evidence to gain an insight on Azrin’s general approach to treatment evaluation and programmatic research. The analysis of Azrin’s approach to research, we believe, holds important lessons to behavior analysts today with an interest in the applied and translational sectors of our science.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40614-020-00278-4.

Keywords: Azrin, scientometrics, sociology of scientific knowledge, translational research

Nathan H. Azrin was born in Boston on November 26, 1930, and died on March 29, 2013, in Pompano Beach, Florida. Few individuals have contributed so extensively to the fields of experimental and applied behavior analysis, and his reputation within and outside academia is evident in the obituaries that followed his death (Association of Behavior Analysis International [ABAI], 2013; Association of Professional Behavior Analysts [APBA], 2013; Ayllon, 2014; Ayllon & Kazdin, 2013; Brecher, 2013; COP España, 2013; Iwata, 2013; Kiffin, 2013; Lattal, 2013; Roustan, 2013; Vitello, 2013), some of them appearing in wide-circulation newspapers (Brecher, 2013; Vitello, 2013).

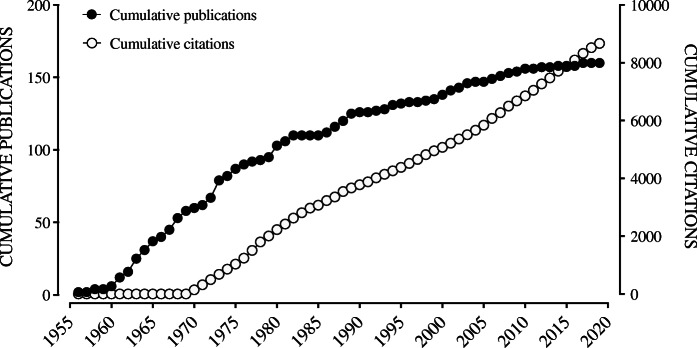

His creative and prolific research programs covered a wide range of experimental and applied areas, from aversive control, reinforcement schedules, and verbal behavior to enuresis, job finding, and clinical disorders such as tics, which resulted in 160 articles and several books published over a period of almost 6 decades (see Fig. 1 for a cumulative record of his publications). As a result, his career illustrates an unparalleled example of translational work in behavior analysis, which has had a major impact not only within our field, but across disciplines and outside academia. For example, SCOPUS® (Elsevier, B.V.) registers over 8,665 citations from psychology, medicine, neuroscience, pharmacology, nursing, and biological sciences sources (see Fig. 1 for a cumulative record of citations between 1955 and 2020). His books have been translated into several languages and have sold millions of copies. The purpose of this article is to provide a brief summary of his key contributions in the following areas: punishment, behavioral engineering, conditioned reinforcement and token economies, feeding disorders, toilet training, overcorrection, habit disorders, in-class behavior, job finding, marital therapy, and substance abuse for which we include the complete list of associated publications. A complete listing of his publications in these areas is available as a supplementary file to article. Table 1 presents selected bibliometric indices of N. Azrin’s work.

Fig. 1.

Azrin’s cumulative number of publications and citations, period 1956–2020 (Source: Scopus; Search date: September 12, 2020).

Table 1.

Nathan Azrin’s number of publications, citations, and period of activity across different areas of experimental and applied behavior analysis.

| Category | Number of publications | Number of citations | Period of activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Punishment and aversive control | 47 | 2320 | 1956–1973 |

| Habit reversal/tics/stuttering | 20 | 1800 | 1958–1994 |

| Conditioned reinforcement/Token economies | 2 | 6 | 1965–1977 |

| Behavioral Engineering | 7 | 216 | 1968–1971 |

| Enuresis/Toilet training | 9 | 588 | 1971–1980 |

| Overcorrection | 11 | 528 | 1971–1981 |

| Job-related behavior | 5 | 218 | 1973–1982 |

| Marital/family counseling | 3 | 248 | 1973–1981 |

| Substance abuse | 23 | 1804 | 1973–2014 |

| In-class behavior | 4 | 173 | 1975–2007 |

| Eating behavior/Bulimia | 6 | 130 | 1986–2008 |

Note. Citations count from Elsevier’s abstract and citation database Scopus (search date: September 12, 2020). The table does not include book citations. A total of 634 citations were allocated to an exclusion category and are not accounted for in the table.

Education and Career

Nathan Azrin was born on November 26, 1930, in Boston, Massachusetts, to Harold and Esther Azrin. His parents owned a modest grocery store where Azrin and his siblings worked. Azrin obtained his BA and MA degrees at Boston University in 1951 and 1952, respectively. While at Boston he was a research assistant at the Boston University School of Medicine where he studied the behavioral effects of radiation in animal models (Dimascio, Arzin, Fuller, & Jetter, 1956). Azrin also assisted in survey studies for the Public Relations and Communications Department. During this time Azrin was interested in clinical psychology, but was discouraged by the lack of an empirical basis for psychotherapy.

Azrin learned about the experimental analysis of behavior and decided to go to Harvard University to study punishment under B. F. Skinner. “[I told Skinner] ‘this is what I plan to do for my dissertation.’ [Skinner] had written extensively against the use of punishment and here there was someone in his own lab studying punishment. His reaction was as gratifying as it was positive. [Skinner] said ‘fantastic, that’s wonderful.’ I could not believe it” (Azrin, 2013). While at Harvard, Azrin also worked on automated educational procedures for teaching arithmetic in primary grade students. Skinner acknowledged some of this early work in The Technology of Teaching (Skinner, 1968, p. 7). Azrin also interacted with Ogden R. Lindsley at the Behavior Research Laboratory, the first human operant laboratory, which Lindsley founded in 1953. There he assisted with operant studies with children with schizophrenia and led a study on cooperation in children (Azrin & Lindsley, 1956). He obtained his PhD in record time in 1955 with a dissertation entitled “A Comparison of the Effects of Two Intermittent Schedules of Immediate and Non-Immediate Punishment.” Azrin had a clear goal upon graduating: “[M]y single-minded objective after graduating was to apply [behavior analysis] to humans to solve practical problems” (Azrin, 2013). Yet, he would still complete 2 postdoctoral years as a research psychologist, one under renowned neurosurgeon Karl H. Pribram at the Institute of Living (1955–1956) and a second year with the U.S. Army Ordnance studying human factors affecting fatigue (1956–1957). In 1958 he was appointed a professor at the Rehabilitation Institute at Southern Illinois University and research director in the Illinois Department of Mental Health. From 1958 to 1980, he was the director of treatment at Anna State Hospital, now known as Choate Mental Health and Development Center. In 1980 he joined Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, as professor of psychology, from which he retired in 2010, same year that he was named emeritus professor.

Areas of Interest

Punishment and Aversive Control

Although N. Azrin agreed with Skinner’s perspective on the advantages of positive reinforcement over aversive control, he felt that a systematic empirical analysis of aversive contingencies was still needed to produce a complete science of behavior (Azrin & Holz, 1966). Starting with his dissertation at Harvard (Azrin, 1956) and continuing through his early career years at Anna State Hospital, Azrin conducted the first and most thorough experimental analysis of the effects of punishment. Most of what is currently known about punishment is directly related to his work in collaboration with several authors, most frequently among them Donald Hake, William C. Holz, Ronald Hutchinson, and Roger E. Ulrich, which resulted in the publication of dozens of papers extending over 2 decades (1956 to 1973; see Table 1).

A thorough discussion of Azrin’s contributions to the understanding of punishment goes beyond the scope of this article; in what follows, we summarize the most prominent points. First, Azrin proposed a functional definition in which punishment was considered as a primary process, i.e., “. . . a reduction of the future probability of a specific response as a result of the immediate delivery of a stimulus for that response. The stimulus is designated as a punishing stimulus; the entire process is designated as punishment” (Azrin & Holz, 1966, p. 382). This approach differed from other contemporary conceptualizations (e.g., Dinsmoor, 1954; Keller & Schoenfeld, 1950) in that there was no need of evidence that escape behavior could be maintained by the punishing stimulus, and the effects of the aversive contingency were directly measurable as a reduction in response rate. Second, Azrin and colleagues thoroughly analyzed different aspects of aversive stimulation (Azrin, 1958; Azrin & Holz, 1966; Flanagan, Goldiamond, & Azrin, 1958, 1959; Herman & Azrin, 1964; Holz & Azrin, 1961, 1962), including designing instruments for testing different stimuli across species (electric shock, noise), comparing unconditioned, conditioned, positive and negative punishment, and demonstrating how time out from reinforcement has under most circumstances punishing effects (Holz, Azrin, & Ayllon, 1963), but can have a reinforcing function in the context of very thin ratio schedules (Azrin, 1961). Third, they conducted a systematic analysis of variables that influence the effectiveness of punishment:

the effects of punishment intensity stimulus and its abrupt or progressive introduction (e.g., sudden introduction of punishment produces much larger response suppression than if the punishment intensity is increased gradually; Azrin, 1959a, 1959b, 1960a, 1960b; Azrin et al., 1963; Holz & Azrin, 1961, 1962; Holz et al., 1963);

the role of immediacy—the delay between the target response and delivery of the punishing stimulus (Azrin, 1956, 1958);

the effects of ratio and interval schedules of punishment (i.e., the rate of a punished response is a direct function of the fixed ratio schedule of punishment, whereas it drops as the moment of the delivery of the punisher approaches under a fixed-interval schedule (Azrin, 1956; Azrin et al., 1963);

the effects of discontinuing punishment (Azrin, 1959b, 1960a, 1960b; Azrin & Holz, 1966);

the schedule of reinforcement maintaining the punished response (e.g., continuous punishment of a response maintained on a variable interval schedule of positive reinforcement reduces the rate but not the uniform temporal patterns of responding; Azrin, 1959b, 1960a, 1960b; Holz & Azrin, 1961; Holz, Azrin, & Ulrich, 1963);

the combined effects of punishment and extinction, which were greater than those observed with punishment or extinction was used alone (Azrin, 1959b; Azrin & Holz, 1961; Holz et al., 1963);

motivating operations (e.g., under drastic food deprivation, punishment only slightly suppress a food-maintained operant response; Azrin et al., 1963);

the role of alternative responses (e.g., availability of an alternative response that produces the same positive reinforcer that maintains the punished response leads to greater suppression; Azrin & Holz, 1966; Herman & Azrin, 1964; Holz et al., 1963); and

the effects of punishment on escape behavior (e.g., a major effect of punishment is to generate a strong tendency to escape from the punishing situation entirely; Azrin, Hake, Holz, & Hutchinson, 1965).

Another key contribution of Azrin’s experimental work is the first demonstration of extinction-induced aggression in collaboration with Ronald Hutchinson and Don Hake (Azrin, Hutchinson, & Hake, 1966). This work is relevant today because it demonstrates the contextual nature of stimuli.

Azrin’s animal and human operant studies on punishment provided him with the experimental training to move into the applied arena. His studies on time-out illustrate this transition. Since his time at Harvard he had been interested in developing a punishment procedure that would not incur in the ethical concerns of punishment by stimulus presentation. His first study on time-out from positive reinforcement, also called “response-produced extinction” at the time, was published in Science in 1961 and was followed by a human operant study with psychiatric patients at Anne State Hospital (Azrin, 1961; Holz et al., 1963).1 Holz et al. has most of the elements of an applied study in that it solves some of the practical problems of implementing time-out such as minimizing the intensity of punishment and providing a concurrent reinforcement schedule for an alternative response. Ayllon and Azrin (1968) provide an almost narrative account of this transition period at Anne Hospital where multiple human operant and interventional studies are conducted with the aim of developing a set of rules to adapt reinforcement, extinction, and punishment procedures to applied settings. The analysis of Azrin’s work at Anne Hospital with Ted Ayllon and others clearly suggests that the basis of his applied work is in the experimental analysis of behavior.

Behavioral Engineering

As an extension of his early work in human factors engineering, Azrin and colleagues began developing in the late 1960s a series of technological behavioral innovations across a wide range of areas (smoking, enuresis, adherence to medical treatments and stuttering), and they used the term “behavioral engineering” to describe their general approach to intervention. Their efforts target the context and time restrictions of traditional psychological treatments (Azrin, Rubin, O’Brien, Ayllon, & Roll, 1968). Namely, behavioral engineering aimed to operate continuously in the natural context of the client by delivering the needed stimuli to produce behavior change. Six requirements were fundamental in the development of this type of innovation:

Behavioral definition: define the target behavior in specific behavioral terms; (2) Apparatus definition: isolate some essential aspect of that behavior that can be physically measured by an apparatus; (3) Response precision: the response output of the apparatus must be selective so that it is activated by all instances of the behavior (no false negatives) but by no instance of non-target behaviors; (no false positives) (4) Effective stimulus consequence: discover some stimulus event that is reinforcing or punishing and that can be delivered physically; (5) Programming the stimulus consequence: program that stimulus as a consequence for the undesired response; and (6) Portable device: construct a portable apparatus that performs the response definition and stimulus delivery and which allows the patient to engage in his normal activities (Azrin, Rubin, et al., 1968, p. 100).

The first effort in this line of research was the development of a technique for smoking cessation. Powell and Azrin (1968) designed a special cigarette case that counted the number of cigarettes consumed (removed) and, depending on the scheduled contingency, delivered electric shocks of different intensities. Using a single-case multiple baseline design, Powell and Azrin found that rates of cigarette smoking varied as a function of the intensity of the shock delivered in a fixed-ratio schedule (FR1)—i.e., 100%, 70%, and 30% with 1.0 mA, 1.5 mA, and 1.7 mA, respectively—and reversals to baseline rates after shock withdrawal. However, Powell and Azrin also found that the amount of time that the participants used the apparatus decreased as a function of the shock intensity, which indicated avoidance behavior, thus limiting the utility of the instrument. To address this issue, Azrin and Powell (1968) modified the protocol by removing the shock and using a fixed-interval reinforcement schedule instead. The system delivered a cue signaling the availability of a cigarette. After each cigarette, the case locked for a given period of time, during which access to the next cigarette was restricted. The authors progressively incremented the duration of locking period (0, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min), and found a systematic and important decrease in the number of smoked cigarettes following the gradual increase in the locking periods (e.g., from one cigarette pack to half a pack).

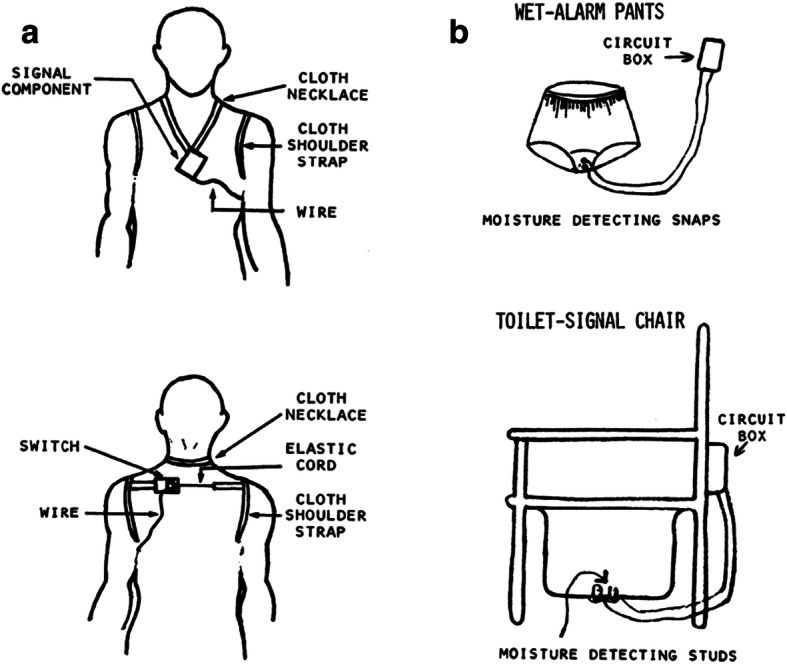

Using similar experimental designs, Azrin, Jones, and Flye (1968) examined the effects of portable devices aimed at modifying other socially relevant behaviors. In the case of slouching, Azrin, Rubin, et al. (1968) developed an apparatus with different sensors in the back that punished slouching postures with a loud tone and negatively reinforced nonslouching with termination and postponement of the tone (see Fig. 2, panel A). The results of this study showed a reduction in slouching time between 62% and 97%. This procedure was also used to increase the regularity with which ambulatory patients took their prescribed medicines (Azrin & Powell, 1969). A loud tone was correlated with the time the medication should be taken and was cancelled when the patient turned a knob that delivered the corresponding pill (escape response). This procedure secured that 97% of the doses were taken in the programmed schedule (Azrin & Powell, 1969).

Fig. 2.

Illustrations of some of the designs by Azrin and colleagues in their studies on behavioral engineering. Panel A shows the apparatus designed for the treatment of slouching (Azrin, Rubin, et al., 1968, p. 102). Panel B illustrate the devices implemented for the treatment of toilet training in patients with cognitive disability (Azrin et al., 1971, p. 250). Reprinted with permission.

Daytime enuresis is a common concern among children with developmental and intellectual disability. To improve urinary continence in this population, Azrin, Bugle, and O’Brien (1971) developed two apparatuses, one that signaled correct toilet use (Toilet-signal chair, see Fig. 2, panel B), and another to detect and signal the presence of moisture in the patient’s underwear (Wet-alarm pants). The independent activation of these devices alerted caregivers to deliver positive reinforcement (e.g., the teacher praised and hugged the child and gave the child a bit of candy) or punishment (e.g., timeout from positive reinforcement by not interacting with the child for 10 min). Implementation of these technologies resulted in a 100% reduction in the rate of daily enuresis. Treatment gains persisted after withdrawing the intervention procedures.

For the treatment of stuttering, Azrin and colleagues instructed patients to synchronize their rate of speech with a tactile or auditory stimulus that was presented periodically via an apparatus specially designed for that purpose (Azrin, Jones, et al., 1968; Jones & Azrin, 1969). They found a 90% reduction in stuttering responses during periods that the clients’ speech was synchronized with the pulsating stimuli, showing natural and fluid vocalizations when the appropriate stimulus duration was adjusted (Azrin, Jones, et al., 1968; Jones & Azrin, 1969).

The success of the various innovations designed by Azrin and colleagues demonstrated the potential of behavioral engineering as treatment aids for a wide range of behavior deficit and excesses for which human-delivered antecedent- and reinforcement-based intervention would have been less contingent or costly.

Conditioned Reinforcement and Token Economies

As director of the Department of Treatment Development at Anna State Hospital, Azrin identified limitations in the application of learning principles in clinical practice, among them the use of single reinforcers for the treatment of single target responses, procedures implemented in a single patient during infrequent or single sessions, and the constant need of having available trained psychologists (Ayllon & Azrin, 1965). With these limitations in mind, Azrin and colleagues conducted experiments aimed at testing the potential use of conditioned reinforcers via token economies applied to multiple responses of groups of psychotic patients. They aggregated well-defined response classes and reinforcing stimuli, which could be incorporated in a general schedule of reinforcement that could be implemented across the entire hospital without losing sight of the preferences and needs of each patient (Ayllon & Azrin, 1965).

By the time of the classic work with Ted Ayllon, The Token Economy: A Motivational System for Therapy and Rehabilitation (Ayllon & Azrin, 1968), they have developed a sophisticated set of 23 rules to enhance the effects of token economies. Some of these rules draw interesting parallels with the dimensions of Baer, Wolf, and Risley (1968) published in the same year (cf., rule of terminal behavior and the behavioral dimension; behavior relevance rule and the applied dimension), but they go far beyond into aspects of measurement (e.g., time and place rule, behavior-effect relation rule) as well as practical aspects (e.g., individual responsibility rule, multiple reinforcing agents rule). Some of these rules predate in several decades the technology of preference and reinforcer assessments (e.g., reinforcer sampling rule, reinforcer variation rule). Their generality goes well beyond the context of using token economies with psychiatric inpatients.

The use of single-case reversal designs allowed them to demonstrate that the use of conditioned reinforcers via tokens were effective in the acquisition and maintenance of relevant behaviors in an applied setting. These findings led Azrin to expand his interests to other applied contexts, especially education (Azrin & Powers, 1975; Azrin, Vinas, & Ehle, 2007). He conducted studies on the development of complex behavior modification programs based on schedules of reinforcement, including token economies, feedback for parents and teachers, and self-correction. He demonstrated that the implementation of intervention programs that include the participation of students in cooperation with and under supervision of parents and teachers, were highly effective in diminishing problem behaviors in the classroom (near 90%), while keeping high indices of students’ satisfaction (Besalel-Azrin, Azrin, & Armstrong, 1977; see also “In-Class Behavior,” below).

Feeding Disorders

Azrin and Armstrong (1973) presented one of the earliest randomized controlled trials (RCT) in applied behavior analysis. The report described a challenging area of intervention in which no success had been attained in the past: teaching independent feeding to adult residents with severe to profound intellectual disability. None of the participants could dress or bath independently, all but one could not speak, and about half “received tranquilizers daily for behavior problems.” The study evaluated a series of novel interventions: small meals to maintain motivation by minimizing food satiation, escape extinction, blocking, and graduated prompting, among others, some of which had not been described previously. This piece of work is a case study on the implementation of a multicomponent behavioral intervention for a large group of individuals attaining large intervention gains both at the individual and group level.

Azrin, Jamner, and Besalel (1986) marked the beginning of a series of studies on rate of food intake as a precursor to vomiting among both individuals with intellectual disability and typically developed adults diagnosed with bulimia. The analytic nature of this line of work contrasts with the synthesis achieved by Azrin and Armstrong (1973). Azrin and his colleagues showed how slower rates of food consumption could reduce vomiting and its precursors (Azrin, Jamner, & Besalel, 1987; Azrin, Kellen, Ehle, & Brooks, 2006; Azrin, Brooks, Kellen, Ehle, & Vinas, 2008). Azrin and colleagues (Morin, Winter, Besalel, & Azrin, 1987) conducted an additional study on bulimia in which they examined the use of response prevention and a cognitive intervention as treatments for binging and vomiting. During the exposure phases, the client was encouraged to eat food portions that had evoked vomiting in the past while being encouraged to refrain from vomiting and to focus on the physical discomfort caused by excessive eating (i.e., DRO plus punishment). The study provided a within-subject demonstration of the superiority of a behavioral intervention for bulimia providing a small example of an experimentum crucis, a form of experimentation that we rarely see in our field.

A later study on eating rate showed that relatively slower eating induced self-reported satiety among weight-conscious individuals (Azrin, Kellen, Brooks, Ehle, & Vinas, 2008). This line of work set a unique precedent in a growing area of research on eating rate and eating awareness as they relate to obesity. It is interesting that the functional relation between eating rate and satiety reported by Azrin, Kellen, et al. (2008) has not been systematically replicated in later research. A meta-analysis by Robinson et al. (2014) suggested that although energy intake may be reduced by slow eating, eating rate has no significant effect on “hunger.” This lack of replication may be due to the unique methodological strategies developed by Azrin and his colleagues to monitor satiety. In particular, Azrin, Kellen, et al. (2008) monitored participants’ level of satiety upon completing 10%, 20%, 30% . . . 100% of the meal while systematically varying eating rates. By contrast, later studies have focused on self-reported hunger at the end of the meal or at a later time point (Robinson et al., 2014).

Toilet Training

Several behavioral approaches to toilet training had been available for some years when Azrin and Foxx developed their program for individuals with intellectual disability (Azrin & Foxx, 1971) and typical children (Azrin & Foxx, 1974; Foxx & Azrin, 1973a). For example, Mahoney and his colleagues at Arizona State University had evaluated a multiphase procedure intended to train the toileting behavior chain sequentially (approaching, undressing, sitting, etc.). Although Azrin and Foxx incorporated some of the strategies that Mahoney and others had developed (i.e., moisture detection apparatuses, frequent liquid ingestion; see also Van Wagenen, Meyerson, Kerr, & Mahoney, 1969), they were critical of the fact that the programs available required extended training often exceeding 1 month, had been evaluated in small case series, and required continuous reminders after the end of training. As often seen in Azrin’s work, his initial approach to an applied problem was the development and evaluation of a multicomponent intervention, followed by systematic replications across populations and settings. Azrin identified a series of acquisition factors whose consideration resulted intervention components: a distraction-free environment, sustained motivation to engage in voiding (frequent drinking), a large number of trials (dense sitting schedule), training the complete toileting chain, reinforcement of correct responses, use of varied reinforcers, frequency and immediacy of reinforcement, antecedent factors including physical guidance and instructions, and consequences for incorrect responses. In their original studies, Azrin and Fox reported a mean 80% decrease in toileting accidents in both normal children and individuals with severe and profound intellectual disabilities within the first day of training, with further reductions in subsequent days maintained over follow-ups conducted over several months.

Systematic replication of the toilet training program across typical and atypical populations illustrated Azrin’s versatile approach to designing intervention programs. It is noteworthy that the intervention with individuals with intellectual disabilities relied heavily on physical guidance and staff management procedures. For example, staff members were required to complete and sign toileting accidents reports to be submitted to their supervisors (Azrin & Foxx, 1971; Azrin, Sneed, & Foxx, 1973, 1974). By contrast, the procedure, as adapted for typical children, made use of least-intensive methods including graduated instructions, imitation, and symbolic practice.

Although Azrin initially emphasized the behavioral engineering side of the problem (Azrin et al., 1971), he later acknowledged that “some parents won’t allow anything electrical near their children” (Azrin, 2013). In subsequent studies, he developed procedures that did not rely on moisture detection apparatuses (Azrin & Thienes, 1978) and that could be delivered by parents after one in-office information session achieving outcomes comparable to those reported in the original studies (Azrin, Thienes, & Besalel-Azrin, 1979). He and his colleagues later published a manual for parents that could be implemented in the absence of any direct professional support (Besalel, Azrin, Thienes, & McMorrow, 1980).

Azrin rarely revisited toilet training after the early 1980s and left the finer component and comparative analyses of his program to others. For example, a component analysis by Greer, Neidert, and Dozier (2016) reported only modest and gradual gains in toileting accidents and self-initiations in a group of children when the sitting schedule and differential reinforcement components were used in isolation. Although a detailed component analysis of the toilet training program developed by Azrin and Foxx has yet to be done, later analyses have recommended only minor modifications to the original procedure. For example, studies by LeBlanc, Carr, Crossett, Bennett, and Detweiler (2005) and Hanney, Jostad, LeBlanc, Carr, and Castile (2013) suggested that some individuals may benefit from a graduated sitting schedule.

In spite of its effectiveness and relevance to solving a highly prevalent problem, Azrin’s toilet training program has not gained widespread acceptance outside of the field of behavior analysis, perhaps due to a tendency in medical and mainstream psychological literature to continue to emphasize more traditional approaches to child rearing. A review published a few years ago in Neurourology and Urodynamics concluded that “there is limited research concerning the effectiveness of different methods, which makes it difficult to guide clinicians in advising parents on how to toilet train their children” (Vermandel, Van Kampen, Van Gorp, & Wyndaele, 2008). At a societal level, epidemiological surveys suggest that knowledge transfer in the area has been limited. A U.S.-based survey indicated that 50% of children remain “untrained” at 36 months of age (Schum et al., 2002; see Juris, 2010, for a transnational replication). These findings suggest a social regression in that earlier ages for toilet training had been reported in the 1950s and 1960s (Brazelton, 1962).

Overcorrection

A major byproduct of Azrin’s work on toilet training was the development of a class of procedures that became one of the most widely used interventions for problem behavior throughout the 1970s and 1980s—overcorrection. One of the components of the Azrin and Foxx (1971) program was a set of consequences for toileting accidents. After receiving a reprimand for being incontinent, the individual was required to (1) shower, (2) wash his soiled clothing, and (3) clean the area (floor, chair, etc.) of any traces of urine. Thus, contingent on an accident, an individual was required to engage in effortful behavior that was related to the context of target problem behavior, and this general procedure served as the underlying basis for overcorrection.

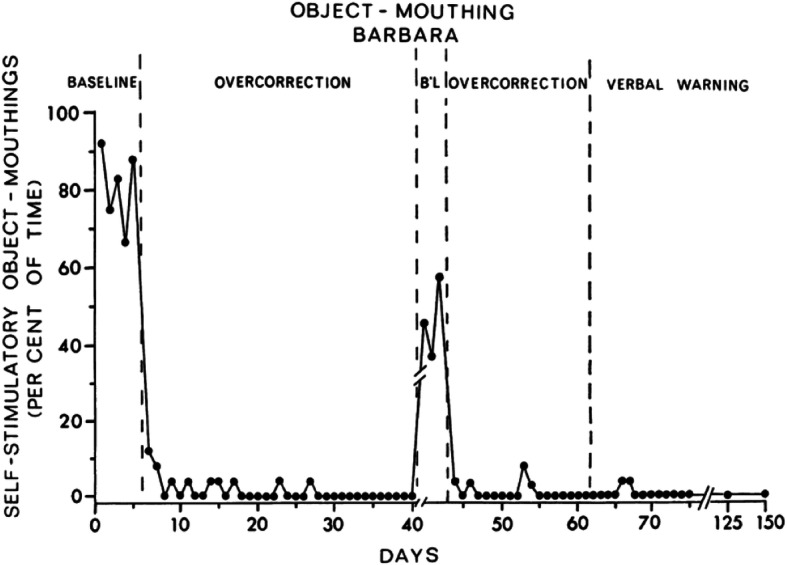

In subsequent studies, Foxx and Azrin (1972, 1973b) distinguished between two types of overcorrection. Restitution involved remedial activity to repair any environmental or physical damage caused by the problem behavior (i.e., property destruction, aggression), whereas positive practice involved sustained, effortful engagement in an appropriate alternative to the problem behavior. In the 1972 study, they implemented both types of overcorrection in replicated AB designs across three individuals for problem behaviors consisting of property destruction, aggression, and screaming. In the 1973 study, they used only positive practice with four individuals who engaged in stereotypy, which did not result in any environmental disruption. They compared the effects of overcorrection with several alternative interventions: two types of punishment (slap, distasteful solution for mouthing), differential reinforcement of other behavior (DRO), and noncontingent reinforcement (NCR) in two studies using reversal designs. Overcorrection was the only procedure that suppressed problem behavior to zero or near-zero levels (first study), and suppression maintained under a verbal-reprimand condition during follow-up ranging from 90 to 150 days (second study; see Fig. 3 as an example for one subject).

Fig. 3.

The effect of the overcorrective oral hygiene and verbal warning procedures on mouthing in a child with intellectual disability. The ordinate is labeled in terms of the percent of time samples in which mouthing was observed. The first slash marks on the abscissa indicates a three-month period. During the baseline periods, no contingencies were in effect for mouthing. From Foxx and Azrin (1973b). Reprinted with permission.

Additional studies by Azrin applied numerous variations of overcorrection with a high degree of success to a wide range problem behaviors, including eating disorders (Azrin & Armstrong, 1973), stereotypy (Azrin, Kaplan, & Foxx, 1973), self-injurious behavior (Azrin, Gottlieb, Hughart, Wesolowski, & Rahn, 1975), stealing (Azrin & Wesolowski, 1974), vomiting (Azrin, Gottlieb, et al., 1975), agitated behavior (Webster & Azrin, 1973), and disruptive classroom behavior (Azrin & Powers, 1975; see further discussion below). Azrin also developed another general type of overcorrection in addition to restitution and positive practice. Described as habit reversal, the procedure was shown to be highly effective in eliminating tics and related “nervous” habits (Azrin & Nunn, 1973; see further discussion below).

Azrin’s studies on overcorrection sparked a number of replications and extensions by others, which established the generality of the procedures across client population, behavior, and setting. Overcorrection quickly gained widespread popularity among applied researchers. For example, it was estimated that one out of every five studies on the treatment of problem behavior in individuals with intellectual disabilities published between 1971 and 1975 involved overcorrection (Bates & Wehman, 1977), and that more than 50 studies on overcorrection were published between the years of 1972 and 1980 (Marholin, Luiseli, & Townsend, 1980).

As was characteristic of much of Azrin’s applied work, overcorrection was a multicomponent intervention that incorporated a variety of procedures and behavioral processes: detailed instructions to engage in a series of responses (stimulus control, chaining), termination of the reinforcing consequences for problem behavior (extinction), programmed consequences for engaging in appropriate behavior (positive and negative reinforcement) and reprimands followed by a period of sustained effort contingent on problem behavior punishment). Because Azrin designed overcorrection as an intervention package, he did not pursue more fine-grained analyses to identify its critical components or the primary processes responsible for its effectiveness. These types of studies were conducted subsequently by other researchers, and the general conclusion based on this work has been that, although the educative aspects of overcorrection contribute to its effectiveness, the major active ingredient of overcorrection is suppression of behavior through punishment. Summaries of this research can be found in numerous reviews published on the topic (e.g., MacKenzie-Keating & McDonald, 1990; Miltenberger & Fuqua, 1981).

Due to a general movement in the field away from the use of punishment in favor of reinforcement-based approaches to behavior reduction, relatively few studies have been published on overcorrection in recent years. However, it is important to note that problem behavior maintained by automatic reinforcement, such as stereotypy and, on occasion, self-injurious behavior, often have been unresponsive to reinforcement-based interventions. As a result, procedures containing various aspects of overcorrection have continued to appear in the literature. Perhaps the best example is a procedure known as response interruption and redirection (RIRD), first described by Ahearn, Clark, MacDonald, and Chung (2007). They designed the procedure as a treatment for vocal stereotypy, and it involved first terminating the response by way of a reprimand and then requiring the individual to answer a series of questions while refraining from stereotypy. In an interesting extension of the Ahearn et al. (2007) study, Ahrens, Lerman, Kodak, Worsdell, and Keegan (2011) found that RIRD was equally effective in treating motor stereotypy and, further, that it did not matter which type of RIRD (involving vocal or motor practice) was applied to which type of stereotypy (vocal or motor). A summary of recent studies on RIRD (Martinez & Betz, 2013) shows its close relation to the overcorrection procedures developed by Azrin.

Habit Disorders

The habit reversal procedure is one of the most widespread applications developed by Azrin. He has been said to select “problems that won’t go away” as preferred areas for research (personal communication to B. A. Iwata, from Iwata, 2013, p. 378). Indeed, tics and nervous habits had been the subject of various laboratory analyses by the early 1970s, but no effective interventions had been developed. Azrin and Nunn (1973) acknowledged that several studies had demonstrated functional relations between nervous habits and various manipulations including self-monitoring, video feedback, and contingent noise termination (Barrett, 1962; Bernhardt, Hersen, & Barlow, 1972; Thomas, Abrams, & Johnson, 1971). However, they were concerned “only with methods that have produced clinical benefits that have occurred in the clients’ everyday life” (p. 627), and those had yet to be developed.

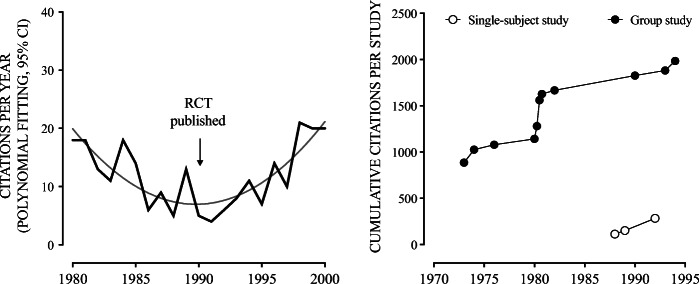

Development of the habit reversal procedure reveals a pattern of clinical innovation evident throughout Azrin’s career. First, an original multicomponent intervention was evaluated with a relatively small number of participants reporting both single-subject and aggregated data. Larger clinical outcome studies, laboratory and comparative analyses, and single-subject component analyses followed (see Fig. 4). This strategy for sequencing research methods may have an incremental effect on the overall impact of a program of research. For example, conducting a randomized controlled trial could galvanize the impact of a treatment model created by other means years before (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Left: Citations per year of Azrin and Nunn's Habit Reversal: A Method for Eliminating Nervous Habits and Tics before and after the first randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the habit reversal method. Right: Cumulative all-time citations of Azrin's publications on habit reversal (1973–1995) disaggregated by research design.

The habit reversal procedure helps to illustrate one further guiding principle of Azrin’s approach to applied research: speed of treatment benefit. “Consider speed of the treatment, which is of obvious importance to the patient and in terms of the cost of professional time. . . . For nervous habits, tics, and stuttering, only a single counseling session was given” (Azrin, 1977, pp. 145–146).

In their original report, Azrin and Nunn (1973) identified four basic elements of the habit reversal procedure: awareness training (comprising response description, response detection, and early warning), competing response training, social support, and motivation strategies. As usual, Azrin did not emphasize the likely governing principles of the procedure (cf. discrimination training, contingent punishment, positive social reinforcement). Azrin’s talent seemed to lie in translating general principles into an algorithm—a set of rules to follow in order to solve a practical problem. Thus, the competing response was described as isometric muscle contraction for motor tics or as regulated breathing in the case of stuttering (Azrin, Nunn, & Frantz, 1979). The multidisciplinary audiences that Azrin targeted in most of his publications were likely to pay more attention to detailed descriptions of procedures. The underlying operant principles were often omitted.

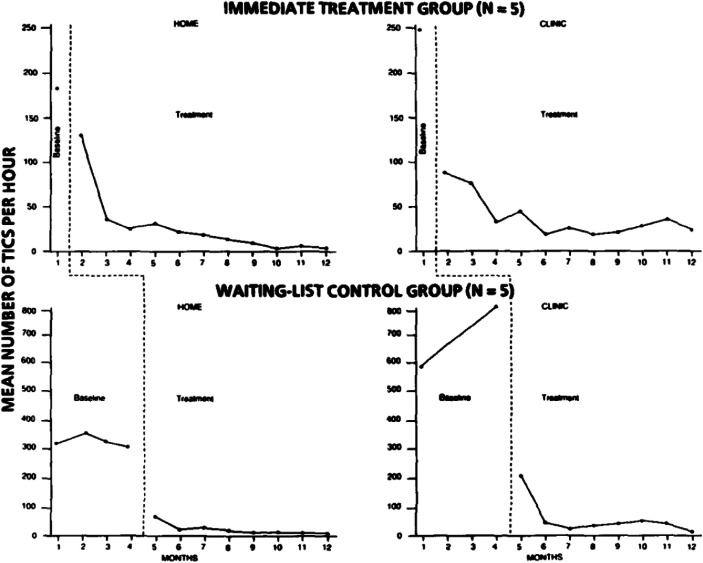

Over the years, Azrin extended the evidence supporting the habit reversal and produced several systematic replications. It is noteworthy that he conducted a series of studies with children and adults diagnosed with Tourette syndrome. For example, Azrin and Peterson (1990) presented a randomized 3-month waiting-list control group design with 10 children and adults diagnosed with Tourette syndrome. It is interesting that the design was fully compatible with the logic of both a single-subject experimental design and a randomized controlled trial (Fig. 5). Azrin and Peterson showed the frequency of tics for each participant as well as the aggregated reductive effects across participants. The study attained an average 93% reduction in the frequency of tics across participants. Azrin also conducted several laboratory analyses and systematic reviews that helped ascertain the relative weight of the procedure and its components against other interventions. Peterson and Azrin (1992) used a reversal design in which six participants were sequentially and repeatedly exposed to series of brief sessions of self-monitoring, relaxation training, and habit reversal (competing response component only) in a laboratory setting. This line of work had been followed by Miltenberger and others with the aim to establish the key effective components of habit reversal (see, e.g., Miltenberger, Fuqua, & McKinley, 1985).

Figure 5.

A 3-month wait-list randomized controlled trial by Azrin and Peterson (1990) illustrates a compromise between single-subject analysis and RCT methodology. Reprinted with permission.

Decades after the original development of the habit reversal procedure, Azrin remained interested in measuring its effects against other pharmacological and behavioral interventions (Peterson & Azrin, 1993; Peterson, Campise, & Azrin, 1994). The concluding remarks from one of these studies continue to be highly relevant today:

Although many behavioral approaches have been demonstrated to be effective and may be useful in the treatment of an individual case, habit reversal is the one behavioral approach with the most consistently demonstrated treatment efficacy. Some of the advantages of habit reversal include its (1) brevity, with some treatments being performed in one 2-hour session; (2) immediacy, with significant reductions often occurring the first day of treatment; (3) efficacy, with symptoms being reduced by over 80% in most cases; (4) durability, with treatment gains being maintained at follow-up; (5) flexibility, with treatment success resulting in some cases whether subjects are treated by a behavior therapist or simply provided with a detailed treatment manual; and (6) consistency, with similar results being obtained by several independent research groups (Peterson et al., 1994, p. 439).

In-Class Behavior

The development of interventions that could be implemented across different populations, contexts, and problem behaviors was a common interest throughout Azrin’s career. Thus, he subsequently refined procedures based on contingencies originally designed for hospital contexts (Ayllon & Azrin, 1965) and extended them in a research program that focused on the acquisition and maintenance of behavioral skills in a school context.

By the 1970s, research already had shown the need for procedures to manage students’ disruptive in-class behavior and offered data supporting the notion that certain schedules of reinforcement (e.g., positive reinforcement and token economies; Ayllon & Azrin, 1968) and teachers’ disapproval increased desired in-class behaviors and reduced responses that interrupted the course of the sessions (Azrin & Powers, 1975). However, Azrin considered that teachers’ disapproval may generate motivational states detrimental to the student–teacher relationship. The following quote summarizes his position:

The problem with all of these negative reinforcers is that they seem punitive in intent rather than being seen as educative. Loosely speaking, the student often feels that the primary intent of the teacher who imposes a token fine, a reprimand, or a time-out, is to make him feel bad and the teacher similarly may feel that the primary intent is to make the student feel bad. (Azrin & Powers, 1975, p. 526)

Another variable examined by Azrin et al. to improve in-class learning was the motivational influence of the instructors. Using a multiple-baseline design, Azrin, Jamner, and Besalel (1989) assessed the effects of solely reinforcing teachers’ instruction, or reinforcing instructions related to students’ improvement. Azrin et al. found that reinforcement of instructors’ behavior alone increased those responses but did not lead to improvement in students’ performance. In contrast, reinforcement of effective instruction resulted in improvement in both teachers’ and students’ performance. Moreover, this approach led several teachers to request more guided instruction to improve their performance.

The findings of these studies underscored the need for designing and implementing educational programs based on schedules of reinforcement that entailed multiple contingencies and the active participation of both students and teachers alike. For instance, the study by Besalel-Azrin et al. (1977) focused not only on maximizing the role of students by including behavioral contracts, token economies, individualized selection of target behaviors and reinforcers, and self-correction, but also on parents’ feedback, and an extensive and personalized interaction student–teacher. Besalel-Azrin et al. reported important reductions of students’ in-class problem behavior, which was found to be socially valid according to the reports by students, teachers, and parents.

Job Finding

Having a gratifying job provides access to many of the benefits and satisfactions that society offers, whereas unemployment often contributes to a number of problems, including social isolation or discrimination, poverty, mental and physical illness, alcoholism, and crime. Jones and Azrin (1973) acknowledged the scope of this problem and concluded that behavior analysis could contribute to an area in which little empirical work had been done: there was the possibility of designing a technology that could help individuals efficiently find jobs.

At the time, a job search was seen as a linear process, in which positions became available and were publicized, candidates applied, and positions were filled with the most suitable applicant. However, Jones and Azrin noted that a more comprehensive view based on a social reinforcement approach would entail reinforcing exchanges among employers, advertisers, and candidates:

When an employer, presumably motivated by personal profit, offers a job, he is offering the opportunity for another person to obtain monetary reinforcement. Several consequences other than financial profit to the employer may follow the act of hiring. The employer may gain a friend, a pleasant and socially rewarding working colleague, or the satisfaction of repaying a social or familial debt. . . . Unlike employers, however, the motivation of non-employer job informants may be ascribed entirely to social factors, since these individuals are not directly concerned with business success or profit. Thus, social reinforcement theory portrays the employment process as an informal job-information network in which persons with early knowledge of job openings (employers and employed persons) selectively and privately pass this rewarding information on to their unemployed acquaintances who are then likely to reward the job informants in social ways. (Jones & Azrin, 1973, p. 346)

With this idea in mind, Jones and Azrin (1973) conducted a pioneering study. They distributed an occupational survey and found that out of 120 positions filled, 63% of the chosen candidates came from the close circle of individuals who knew about the opening, 71% were past employees of the hiring company, and 53% exerted some degree of influence in the hiring process. They subsequently implemented an advertisement procedure that reinforced sharing information about the job openings, which produced 10 times more dissemination of the vacant positions and eight times more hiring (Jones & Azrin, 1973). These findings supported Azrin, Flores, et al.’s (1975) notion that finding a job is more than a function of a candidate’s skills because other sources of social influence are crucially important. The resulting system they developed has been referred to as the Job-Finding Club, which extended traditional counseling approaches by training skills needed in complex job-search contexts that entail motivational, feedback, imitation, and practice variables. This package was combined with continuous support centered on the job-seeker using group protocols and a “friends” and family system through which job-search information was shared.

The job-finding club was effective in securing positions in 90% of the participants who followed the program consistently for 2 months, obtaining salaries a third higher than those obtained by participants who were not assisted with the program, of which 44% were still unemployed 3 months after starting their job search.

The success of this first implementation of the program resulted in that Azrin, Philip, Thienes-Hontos, and Besalel (1980) obtained a grant from the Employment and Training Administration of the U.S. Department of Labor that supported the application and assessment of this technological innovation across five U.S. cities. Azrin et al. found that 87% of the participants enrolled in the job club secured a position during the first 12 months of the program versus 54% of job-seekers assigned to the control group. Participants started finding jobs on average after 11 sessions of the program, and 90% of them were hired after the 23 sessions that the intervention entailed. These findings were replicated irrespective of sex, age cohort, educational level, and diagnosis of a disability (Azrin et al., 1980).

The job-finding club developed by Azrin and colleagues changed how the job search process was understood and intervened from a behavioral perspective. Not only was effective in helping participants finding jobs, but also in securing better employee satisfaction (Azrin, Flores, & Kaplan, 1975; Azrin et al., 1980). This important innovation not only benefited the general population with the subsequent publication of the book Finding a Job (Azrin & Besalel-Azrin, 1982), but also governmental agencies by reducing in half the payments of social-welfare benefits after 6 months of being implemented (Azrin, Philip, Thienes-Hontos, & Besalel, 1981).

Marital Therapy

Richard B. Stuart, a social worker by training, published an article entitled “Operant-Interpersonal Treatment of Marital Discord” in 1969, which stressed the use of contingency contracting and reciprocal social reinforcement between spouses to solve problems resulting in marital discord. Azrin recalled reading Stuart’s work and finding much room for improvement in the procedures, but above all, he was impressed with the use of objective behavioral measures in this context (e.g., daily hours of conversation, weekly rate of sex; Azrin, 2013).

Azrin extended Stuart’s operant approach to marital discord: “[I took] a reinforcement point of view. Why do people get married? Because more reinforcers would be available to them in marriage than in single state. What are those reinforcers? Sex, communication, social relationships, vocational assistance. . .” (Azrin, 2013). Once the reinforcers had been identified, the intervention was aimed at increasing the rate of reinforcement. Azrin called the program “reciprocity counseling” because the partners were considered complementary sources of reinforcement for each other (Azrin, Naster, & Jones, 1973). Reinforcement had to be reciprocal for the intervention gains to be sustainable. Couples received instruction and feedback on how to specify the behavioral expectations that they placed on each other. In an attempt to minimize the social punishment that often follows the expression of desires, Azrin encouraged couples to indicate the gratifications they expected from their partners selfishly. Yet, all behavioral expectations had to be agreed upon in writing as part of a contingency contract.

The program incorporated ingenious features to maximize access to reinforcement. For example, Azrin developed written feedback forms that helped to indirectly communicate sexual preferences, thereby bypassing the “frequent, and often extreme, reluctance of partners to communicate the details of their sexual desires to each other” (Azrin, Flores, et al., 1975, p. 375). Although couples identified reinforcers idiosyncratically, the sex feedback procedure and a positive statement procedure (balancing negative and positive verbal statements) were relatively standard across all participating couples. Over successive sessions in which professional support was gradually faded, couples targeted a total of nine problem areas. The program was designed to be completed in eight sessions over a 4-week span. By the end of the program couples were expected to generalize their newly acquired skillset to other problem areas (Azrin, Naster, et al., 1973).

Azrin initially relied on a multidimensional, self-report measure of happiness as the key outcome of the intervention, although he considered it a nonbehavioral approach to measurement. In a subsequent randomized controlled trial with a larger number of couples, Azrin incorporated a standardized outcome of marital satisfaction that would be more typical of the mainstream marital therapy literature (Kimmel & Van der Veen, 1974).

In spite of the large effects reported by Azrin and his colleagues through several systematic replications (Besalel-Azrin & Azrin, 1981), “reciprocity counseling” is a term unknown to marital therapists and behavior analysts alike and is one of Azrin’s contributions that has not yet been widely disseminated.

Substance Abuse

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, part of Azrin’s research efforts were directed toward the development of an intervention program based on operant principles for patients with alcoholism (Hunt & Azrin, 1973). Azrin and colleagues designed, assessed, and refined a community-reinforcement approach (CRA), which focused on the rearrangement of reinforcers on a personal and community level via implementation of a multicomponent program (Azrin, 1976):

The community-reinforcement program contained four separate components each of which provided satisfactions that would interfere with drinking. (1) The counselor placed alcoholics in jobs which had characteristics that interfered with drinking such as being full-time, steady, satisfying and well-paying. (2) Marriage and family counseling procedures were used, which increased the alcoholic’s satisfactions in his marriage or family such that he would be involved more continuously and pleasurably in family activities. (3) A self-governing social club for abstinent alcoholics was organized for providing the clients with enjoyable social events especially during the evening hours and on weekends. (4) The alcoholic was primed into engaging in pleasurable hobbies and recreational activities that would provide an alternative to drinking. (p. 339)

Implementation of the program showed positive results for patients diagnosed as alcoholic, with substantial decrease in (1) time they spent consuming alcohol (14% CRA vs. 79% control); (2) periods without employment (5% CRA vs. 62% control); (3) time away from their families (16% CRA vs. 36% control); and (4) number of hospitalizations related to alcohol consumption (2% CRA vs. 27% control). Although in general these effects were maintained after 6 months (Hunt & Azrin, 1973), several patients did not remain fully abstinent, showing periods of alcohol consumption often related to adverse events (e.g., job loss or family crisis). Azrin (1976) adjusted the program by adding a myriad of new intervention components including disulfiram, a pharmacological agent inducing alcohol hypersensitivity. The enhanced version of the program reduced the time spent consuming alcohol to 2% in the intervention group. The study illustrated the potential for integrating behavioral and pharmacological interventions: according to a subsequent analysis those receiving disulfiram alone showed near-zero adherence 6 months into the program (Azrin, Sisson, Meyers, & Godley, 1982).

The success of the CRA program with alcoholism led to subsequent efforts by Azrin and colleagues to develop analogue interventions for other types of substance abuse (e.g., marihuana, cocaine, methamphetamines, LSD, and benzodiazepines). This research program focused primarily on adolescent population (Donohue et al., 2009) and evaluated a new set of intervention components: (1) stimulus control—reducing the patient’s contact with contexts, individuals, or situations associated with drug consumption via incrementing the patient’s engagement in activities and contact with situations that were incompatible; (2) urge control—interrupting private stimuli such as proprioceptive sensations and thoughts associated with drug consumption via activation of private or public stimuli (e.g., relaxation, competing activities, and evaluation of consequences); and (3) social control/behavioral contracts—formalizing agreements by which the patient acquired support and motivation to maintain abstinence via the influence of significant others (Azrin, Donohue, Besalel, Kogan, & Aciemo, 1994; Azrin, McMahon et al., 1994; Azrin, Donohue, Besalel, Acierno, & Kogan, 1995).

Azrin’s work with adolescents led to the development of the family behavior therapy (FBT), which not only focuses on the consumption behavior of the client, but also addresses concurrent problems in the family context, such as behavioral disorders, abuse or neglect, unemployment, and depression (Donohue et al., 2009; Donohue et al., 2010; Donohue & Azrin, 2002). FBT has been endorsed by the National Registry of Evidence-Based Practices and Programs (NREPP) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (Donohue et al., 2009) and has been recognized as a treatment for addictions by the National Institutes of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (2005).

Current Issues of Translational Research and Final Remarks

Although the fields of basic and applied behavior analysis share a common theoretical orientation and research methodology, their goals are distinct (Kyonka & Subramaniam, 2018). Basic research asks general questions about environment–behavior relations in an attempt to isolate the effects of independent variables. Precision and control, therefore, are of paramount concern, and the response usually is selected as a matter of convenience. By contrast, applied research asks questions about variables that influence socially important behavior (Baer et al., 1968), and greater emphasis is placed on those who engage in adaptive or maladaptive responses and how their situations can be improved (or how they are worsened). As a result, it is rare to find individuals who develop significant research programs in both areas. Nathan Azrin was one of those individuals. Azrin was a pioneer in translational research for his efforts to “break new ground by uniting a concern for fundamental principles with a concern for everyday problems and outcomes” (Mace & Critchfield, 2010, p. 296). Across his body of work, there is a constant effort to apply a wide range of operant contingencies that had been extensively studied in the laboratory. Azrin’s translational work was instrumental to the emergence of applied behavior analysis as a distinct field. Azrin’s successful record of research translation may have been a function of his training in both the basic and applied sectors, which contrasts with the current professional contingencies, which strongly reinforce specialization. The recent emphasis of the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (2017) on basic coursework signals professional contingencies that could help shape scientific behavior resembling Azrin’s in future generations of behavior analysts. We need more of this behavior.

To say that Nathan Azrin was a pioneer hardly does justice to the lasting impact he has had because his work appears in every textbook in basic and applied behavior analysis. Moreover, the procedures he developed continue to influence research to the present time, and many interventions commonly used by behavior analysts on a daily basis are the direct result of his work. In recognition of his contributions, Azrin served as president of the major societies for experimental behavior analysis, applied behavior analysis, and clinical behavior therapy. He also received no less than 15 awards and citations from various organizations, including the prestigious Award for Distinguished Contributions to the Application of Psychology from the American Psychological Association. In summary, Nathan Azrin’s work serves as a model for basic and applied science and will continue to be a catalyst as the field develops and matures.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 28 kb)

Footnotes

Azrin’s work on time-out from positive reinforcement predates that of Arthur W. Staats and Montrose M. Wolf by several years (Staats, 1971; Allen, Hart, Buell, Harris, & Wolf, 1964). However, most sources attribute the procedure to Staats (see, for example, Kuriakose, Koegel, & Koegel, 2013, and Schaaff, 2019).

An earlier and partial version of this manuscript has been published in Portuguese in Zilio, D. and Carrara, K. (Eds.), Behaviorismos: Reflexôes Históricas e Conceituais (Vol. 3; pp. 19–56). São Paulo, Brazil: Centro Paradigma de Ciências do Comportamiento.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahearn WH, Clark KM, MacDonald RPF, Chung BI. Assessing and treating vocal stereotypy in children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40(2):263–275. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.30-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens EN, Lerman DC, Kodak T, Worsdell AS, Keegan C. Further evaluation of response interruption and redirection as treatment for stereotypy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44(1):95–108. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen KE, Hart B, Buell JS, Harris FR, Wolf M. Effects of social reinforcement on isolate behavior of a nursery school child. Child Development. 1964;35:511–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1964.tb05188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI). (2013). Nathan Azrin. Retrieved from https://www.abainternational.org/constituents/bios/nathanazrin.aspx

- Association of Professional Behavior Analysts (APBA). (2013). Nathan Azrin dies at 82. Retrieved from http://www.apbahome.net/news/352801/Nathan-Azrin-dies-at-82.htm

- Ayllon T. Working with Nathan Azrin: A remembrance. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2014;101:181–185. doi: 10.1002/jeab.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayllon T, Azrin NH. The measurement and reinforcement of behavior of psychotics. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1965;8:357–383. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1965.8-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayllon, T., & Azrin, N. H. (1968). The token economy: A motivational system for therapy and rehabilitation. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Ayllon T, Kazdin A. Nathan H. Azrin (1930 –2013) American Psychologist. 2013;68:33763. doi: 10.1037/a0033763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin N, Jones RJ, Flye B. A synchronization effect and its application to stuttering by a portable apparatus. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1:283–295. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH. Some effects of two intermittent schedules of immediate and non-immediate punishment. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary & Applied. 1956;42:3–21. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1956.9713020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH. Some effects of noise on human behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1958;1:183–200. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1958.1-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH. A technique for delivering shock to pigeons. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1959;2:161–163. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1959.2-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH. Punishment and recovery during fixed-ratio performance. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1959;2:301–305. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1959.2-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH. Effects of punishment intensity during variable-interval reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1960;3:123–142. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1960.3-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH. Sequential effects of punishment. Science. 1960;131:605–606. doi: 10.1126/science.131.3400.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH. Time-out from positive reinforcement. Science. 1961;133:382–383. doi: 10.1126/science.133.3450.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH. Improvements in the community-reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1976;14:339–348. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(76)90021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH. A strategy for applied research: Learning based but outcome oriented. American Psychologist. 1977;32:140–149. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.32.2.140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin, N. H. (2013). Colloquium given at Florida International University. Full video available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pe1JFo1mp9g&t=1173s

- Azrin NH, Armstrong PM. The “Mini-Meal”: A method for teaching eating skills to the profoundly retarded. Mental Retardation. 1973;11(1):9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Besalel-Azrin VA. Finding a job. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Brooks J, Kellen MJ, Ehle C, Vinas V. Speed of eating as a determinant of the bulimic desire to vomit. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2008;30:263–270. doi: 10.1080/07317100802275728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Bugle C, O’Brien F. Behavioral engineering: Two apparatuses for toilet training retarded children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1971;4:249–253. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1971.4-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Donohue B, Besalel VA, Kogan ES, Aciemo R. Youth drug abuse treatment: A controlled outcome study. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 1994;3:1–16. doi: 10.1300/J029v03n03_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Donohue BC, Besalel VA, Acierno R, Kogan ES. A new role for psychology in the treatment of drug abuse. Psychotherapy in Private Practice. 1995;13(3):73–80. doi: 10.1080/J294v13n03_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Flores T, Kaplan SJ. Job-finding club: A group-assisted program for obtaining employment. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1975;13:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(75)90048-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Foxx RM. A rapid method of toilet training the institutionalized retarded. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1971;4:89–99. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1971.4-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Foxx RM. Toilet training in less than a day. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Gottlieb L, Hughart L, Wesolowski MD, Rahn T. Eliminating self-injurious behavior by educative procedures. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1975;13:101–111. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(75)90004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Hake DF, Holz WC, Hutchinson RR. Motivational aspects of escape from punishment. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1965;8:31–44. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1965.8-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Holz WC. Punishment during fixed-interval reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1961;4:343–347. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1961.4-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin, N. H., & Holz, W. C. (1966). Punishment. In W. Honig (Ed.), Operant behavior: Areas of research and application (pp. 380–447). New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Azrin NH, Holz WC, Hake DF. Fixed-ratio punishment. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1963;6:141–148. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1963.6-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Hutchinson RR, Hake DF. Extinction-induced aggression. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1966;9:191–204. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1966.9-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Jamner JP, Besalel VA. Vomiting reduction by slower food intake. Applied Research in Mental Retardation. 1986;7:409–413. doi: 10.1016/S0270-3092(86)80014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Jamner JP, Besalel VA. The rate and amount of food intake as determinants of vomiting. Behavioral Interventions. 1987;2(4):211–221. doi: 10.1002/bin.2360020404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Jamner JP, Besalel VA. Student learning as the basis for reinforcement to the instructor. Behavioral Residential Treatment. 1989;4:159–170. doi: 10.1002/bin.2360040302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Kaplan SJ, Foxx RM. Autism reversal: Eliminating stereotyped self-stimulation of retarded individuals. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1973;78(3):241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Kellen MJ, Brooks J, Ehle C, Vinas V. Relationship between rate of eating and degree of satiation. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2008;30:355–364. doi: 10.1080/0731710080248322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Kellen MJ, Ehle CT, Brooks JS. Speed of eating as a determinant of bulimic desire to vomit: A controlled study. Behavior Modification. 2006;30:673–680. doi: 10.1177/0145445505277149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Lindsley OR. Reinforcement of cooperation between children. Journal of Abnormal & Social Psychology. 1956;52:100–102. doi: 10.1037/h0042490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin, N. H., McMahon, P. T., Donohue, B., Besalel, V. A., Lapinski, K. J., Kogan, E. S., … Galloway, E. (1994). Behavior therapy for drug abuse: A controlled treatment outcome study. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 32, 857–866. 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90166-X. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Azrin NH, Naster BJ, Jones R. Reciprocity counseling: A rapid learning-based procedure for marital counseling. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1973;11:365–382. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(73)90095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Nunn RG. Habit-reversal: A method of eliminating nervous habits and tics. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1973;11:619–628. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(73)90119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Nunn RG, Frantz SE. Comparison of regulated-breathing versus abbreviated desensitization on reported stuttering episodes. Journal of Speech & Hearing Disorders. 1979;44:331–339. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4403.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Peterson AL. Treatment of Tourette Syndrome by habit reversal: A waiting-list control group comparison. Behavior Therapy. 1990;21:305–318. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80333-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Philip RA, Thienes-Hontos P, Besalel VA. Comparative evaluation of the Job Club program with welfare recipients. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1980;16(2):133–145. doi: 10.1016/0001-8791(80)90044-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Philip RA, Thienes-Hontos P, Besalel VA. Follow-up on welfare benefits received by Job Club clients. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1981;18:253–254. doi: 10.1016/0001-8791(81)90012-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Powell J. Behavioral engineering: The reduction of smoking behavior by a conditioning apparatus and procedure. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1:193–200. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Powell J. Behavioral engineering: The use of response priming to improve prescribed self-medication. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1969;2:39–42. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1969.2-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Powers MA. Eliminating classroom disturbances of emotionally disturbed children by positive practice procedures. Behavior Therapy. 1975;6:525–534. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(75)80009-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin N, Rubin H, O’Brien F, Ayllon T, Roll D. Behavioral engineering; postural control by a portable operant apparatus. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1:99–108. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Sisson RW, Meyers R, Godley M. Alcoholism treatment by disulfiram and community reinforcement therapy. Journal of Behavior Therapy & Experimental Psychiatry. 1982;13:105–112. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(82)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Sneed TJ, Foxx RM. Dry bed: A rapid method of eliminating bedwetting (enuresis) of the retarded. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1973;11:427–434. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(73)90101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Sneed TJ, Foxx RM. Dry-bed training: Rapid elimination of childhood enuresis. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1974;12:147–156. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(74)90111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Thienes PM. Rapid elimination of enuresis by intensive learning without a conditioning apparatus. Behavior Therapy. 1978;9:342–354. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(78)80077-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Thienes PM, Besalel-Azrin V. Elimination of enuresis without a conditioning apparatus: An extension by office instruction of the child and parents. Behavior Therapy. 1979;10:14–19. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(79)80004-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Vinas V, Ehle CT. Physical activity as reinforcement for classroom calmness of ADHD children: A preliminary study. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2007;29:1–8. doi: 10.1300/J019v29n02_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Wesolowski MD. Theft reversal: An overcorrection procedure for eliminating stealing by retarded persons. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1974;7:577–581. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1974.7-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1:91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1987.20-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett BH. Reduction in rate of multiple tics by free operant conditioning methods. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disorders. 1962;135:187–195. doi: 10.1097/00005053-196209000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates P, Wehman P. Behavior management with the mentally retarded: An empirical analysis of the research. Mental Retardation. 1977;15:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2017, January). Introducing the BCBA/BCaBA Task List (5th ed.). BACB Newsletter. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/170113-newsletter.pdf

- Bernhardt AJ, Hersen M, Barlow DH. Measurement and modification of spasmodic torticollis: an experimental analysis. Behavior Therapy. 1972;3:294–297. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(72)80094-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Besalel VA, Azrin NH, Thienes PM, McMorrow M. Evaluation of a parent’s manual for training enuretic children. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1980;18:358–360. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(80)90096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besalel-Azrin V, Azrin NH, Armstrong PM. The student-oriented classroom: A method of improving student conduct and satisfaction. Behavior Therapy. 1977;8:193–204. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(77)80268-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Besalel-Azrin VA, Azrin NH. The reduction of parent–youth problems by reciprocity counseling. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1981;19:297–301. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(81)90050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazelton TB. A child-oriented approach to toilet training. Pediatrics. 1962;29:121–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecher, E. J. (2013, April 10). Psychologist Nathan Azrin wrote “potty training manual,” dies of cancer. Miami Herald, 1–3. Retrieved from http://www.nathanazrin.com/uploads/5/8/0/9/5

- COP España. (2013, April). Obituario: Nathan Azrin. InfoCop Online, 1–2. Retrieved from http://www.infocop.es/view_article.asp?id=4505

- Dimascio A, Arzin NH, Fuller JL, Jetter W. The effect of total-body X irradiation on delayed-response performance of dogs. Journal of Comparative & Physiological Psychology. 1956;49:600–604. doi: 10.1037/h0039954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinsmoor JA. Punishment: I. The avoidance hypothesis. Psychological Review. 1954;61:34–46. doi: 10.1037/h0062725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue, B., Azrin, N., Allen, D. N., Romero, V., Hill, H. H., Tracy, K., … Van Hasselt, V. B. (2009). Family behavior therapy for substance abuse and other associated problems: A review of its intervention components and applicability. Behavior Modification, 33(5), 495–519. 10.1177/0145445509340019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Donohue B, Azrin NH. Family behavior therapy in a conduct-disordered and substance-abusing adolescent: A case example. Clinical Case Studies. 2002;1:299–323. doi: 10.1177/153465002236506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]