Abstract

Diverse researchers have considered by-products of food and agricultural processing industries as a source of antioxidants. Tamarind (Tamarindus indica) is a leguminous tree, native from tropical Africa bearing edible fruit. The fruit is composed of 30% pulp, 40% seed, and 30% pericarp. Currently, tamarind pericarp is a waste from tamarind processing (approximately 54,400 tons of pericarp in 2012 worldwide) and is contributing to environmental contamination. This research aimed to determine the effect of maceration, microwaves, and ultrasound on the increase in the antioxidant availability in tamarind pericarp and its incorporation as a functional ingredient in cookies (5 and 10% substitution). Antioxidant content, antioxidant activity, proximate, and sensorial analysis of the cookies were conducted. The microwave method was the best pretreatment compared with sonication and maceration since it showed 1.3-fold higher amounts of phenolic compounds and 1.2-fold higher antioxidant capacity. The 10% substitution of tamarind pericarp powder in cookies, significantly increased the fiber content (four-fold) and phenolic compounds content (2.6-fold) and the product presented good acceptance in a sensorial test. Thus, tamarind pericarp powder could be considered as an antioxidant and fiber source and could be used as a functional ingredient in food products.

Keywords: Tamarind pericarp, By-product, Microwave, Phenolic compounds, Antioxidant capacity, Cookie

Introduction

There has been increasing interest over the use of natural antioxidants primarily due to free radical scavenging ability of a variety of phytochemicals, mainly phenolic compounds. These compounds have attracted the attention of food biotechnologists and medical scientists due to their potent in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activities and their ability to scavenge free radicals. The latter is highly reactive, and unstable molecules are produced as a result of normal metabolism in higher organisms (Salara et al. 2016). Currently, industries are interested in developing value-added products developed from the by-products (seeds, peels, pericarp, stems, and leaves) of food and agricultural processing industries that contain appreciable amounts of phenolic compounds. Among these by-products, tamarind pericarp has been considered by different researchers as a source of antioxidants (Natukunda et al. 2016; Perez et al. 2017).

Tamarind (Tamarindus indica) originated in Africa but has spread widely throughout tropical countries (Tril et al. 2014). India is the main tamarind producer (more than 300,000 tons in 2012) followed by Costa Rica with 220,000 tons, Thailand with 150,000 and Mexico with 39,000 (Rao and Kumar 2015; Real-de-Colima 2017). Tamarind pulp is used in different dishes due to its sour taste and flavor (Singh et al. 2007). Every part of the Tamarindus indica plant (root, body, fruit, and leaves) has not only rich nutritional value and broad usage in medicine but also industrial and economic importance (Kuru 2014). Tamarind contains 30% pulp, 40% seed, and 30% pericarp. Conventionally farmers are selling pulp only, remaining seeds and shell as waste (Rao and Kumar 2015). This waste presents a high content of polyphenolic compounds (Ganesapillai et al. 2017).

The phenolic compounds in plants and their parts are influenced by chemical composition, variety, and heat treatments (He et al. 2015). Maximum availability of these phytochemicals requires optimized process parameter conditions. Different methods have been reported to increase the availability of polyphenols in plants using maceration, ultrasound, sonication and microwaves (Drosou et al. 2015); Dahmoune et al. 2015; Quiroz-Reyes et al. 2013). Currently, in order to save time, space and material, maceration, sonication and microwaving are simulated by experimental designs combined with response surface methodology (RSM) and a statistical system to determine the optimal values of independent variables, accomplishing a maximum response. The RSM permits the user to investigate the interaction of individual variables, which is considered more efficient than traditional single parameter optimization (Felix et al. 2018).

Cookies have become one of the most popular and well-accepted snacks among all age groups worldwide (Cheng and Bhat 2016). Consumers are looking for healthy products that are improved by adding nutritional properties (Perez et al. 2017). Traditionally, cookies are made of refined wheat flour (Kaur et al. 2017a, b; Sharma et al. 2016). Recently, cookies have been made with different types of fruits, seeds, cereals or vegetables, such as carrot pomace, jeering seed, fruit pomace, oat bran, water chestnut and alfalfa seeds, in order to improve texture, color, flavor, and aroma and reduce the energy content (Cheng and Bhat 2016; Giuberti et al. 2018; Shafi et al. 2016). Additionally, tamarind seed powder has been incorporated in cookie formulation resulting in a source of natural antioxidants for food products (Natukunda et al. 2016).

This work aimed to evaluate the effect of three different pretreatments (maceration, sonication, and microwave) on phenolic compound availability of tamarind pericarp and evaluate the application of tamarind pericarp powder as a functional ingredient in a cookie formulation.

Materials and methods

Materials

Tamarind (native, big pod) was provided by Real de Colima who is the largest producers of tamarind in Mexico. The tamarind was harvested in summer 2016.

Preparation of tamarind pericarp powder

Pericarps were removed from pulp manually and rinsed with tap water to remove impurities and insect defects. The pericarps were ground in a rotary mill (Brabender GmbH & Co. KG, Germany) during 2 h until 100% of the powder passed through a 0.042 mm sieve. The grinding yield of tamarind pericarp is approximately 96% per kg.

Proximate analysis

Proximate analysis was performed using the following standard AOAC (2000) methods: moisture content was determined by method 979.09; crude protein by the Kjeldahl method (46-1249); crude fat by the Soxhlet extraction method (30-10) and ash content by a dry method (968.08). Carbohydrate content was calculated by difference to 100%.

Pretreatment of tamarind pericarp powder

Response surface methodology (RSM) was used to find the best pretreatment conditions and their effects on phenolic compounds availability. The independent factors were time and temperature and, in the case of the microwave, different power levels, and the response was total phenolic content. An orthogonal routable central composite design for two factors was performed, resulting in sixteen combinations for each pretreatment method. An equation of linear regression for the optimal response was calculated by a second-degree polynomial equation and was used to fit the experimental data of the studied variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was executed to calculate the regression coefficient of the response surface equation and verify the validity of the RSM. The experimental design was carried out using Design Expert® software (version 11.0)

The optimized conditions of the independent variables were further applied to validate the model, using the same experimental procedure as reported previously. Triplicate samples of the optimized proportion were prepared and analyzed. The pretreatments were conducted as follows:

Maceration Pretreatment was performed under the following conditions: 0.5 g of tamarind pericarp was added to 10 mL of 60% ethanol and stirred at 4, 20, 37 and 60 °C for 0, 720 and 1440 min.

Microwave Pretreatment was performed in a domestic microwave oven (LG mod MS1744XT/00). 0.5 g of sample was weighed and heated at power levels of 20, 40, 80 and 100% for 0.5, 1 and 3 min and later, 10 mL of 60% ethanol was added.

Sonication Pretreatment was performed in ultrasound equipment (Ultrasonic Cleaner, mod SB-5200 DTN). 0.5 g of the sample was weighed and ultrasonicated at 20, 30, 40 and 50 °C for 20, 40 and 60 min in 10 mL of 60% ethanol.

After the samples were pretreated with the three methods and stirred at 200 rpm for 1 h (Thermo scientific mod. 135935, China), the samples were centrifuged (Hermle Z326, Germany) at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity were determined from the supernatant.

Cookie elaboration

Raw materials for cookies were purchased from local supermarkets in Mexico City and stored or refrigerated according to the supplier instructions. Tamarind pericarp powder pretreated with microwaves was incorporated into the cookie formulation to substitute wheat flour by 5% and 10% based on wheat flour weight. The ingredients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cookie formulation

| % of tamarid pericarp powder substitution | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ingredients (g) | Control | 5% | 10% |

| Wheat flour | 800 | 760 | 720 |

| Tamarind pericarp powder | – | 40 | 80 |

| Butter | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| Brown sugar | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| Egg white | 112.5 | 112.5 | 112.5 |

| Milk powder | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 |

| Baking powder | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Salt | 3 | 3 | 3 |

The dough was prepared by mixing the ingredients in an electric mixer (KitchenAid, model K5SS, USA). In a container, milk powder, salt and baking powder were mixed. In a separate container, butter and brown sugar were mixed for 2 min at medium speed; then, fresh egg whites were added and mixed for two more min. Tamarind pericarp powder was added, and after 2 min, wheat flour was incorporated and combined for 3 min at high speed; then, the baking powder, salt and milk powder were added. Water was added slowly until the dough was homogenous. The mixture was kneaded and molded to a uniform thickness of 1 cm and cut into circular shapes (5 cm diameter) using a cookie cutter. Baking was carried out at 180 °C for 15 min in an electrical oven (Turbofan model E32D5, New Zealand). The average weight of the cookies was 10 g. Cookies made from wheat flour served as the control.

Bioactive compound content and antioxidant capacity of the dough and baked cookies were analyzed as explained in the following sections. The caloric content was calculated according to the amounts obtained for protein, ethereal extract and non-nitrogen extract determined by proximate analysis as described previously.

Total phenolic compounds (TPC)

The total phenolic content was estimated by the Folin-Ciocalteu method (Cortez-García et al. 2015). The reaction mixture contained 100 µL of sample extract, 900 µL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and 750 µL of 7% sodium bicarbonate solution. After 90 min at room temperature, the absorbance at 725 nm was measured by a Jenway 6705/UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Staffordshire, UK) and used to calculate the phenolic content using a calibration curve of gallic acid as the standard. The results were expressed as mg gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per gram of dry weight (DW) sample.

Antioxidant capacity

The antioxidant capacity in the tamarind pericarp extracts and cookies were performed via three different methods: 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 2,2′-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP). Briefly, in the DPPH method, each sample extract (50 µL) was mixed with 1950 µL of DPPH solution and left in the dark at room temperature for 60 min, and the absorbance reading was taken at 515 nm. The ABTS test was carried out to measure the antioxidant capacity. A total of 20 µL of the extract was mixed with 3 mL of ABTS solution, and the absorbance was monitored at 734 nm after 6 min of incubation following the addition of each sample extract. The FRAP method was conducted by preparing a solution of 10 mM TPTZ and 20 mM ferric chloride, diluted in 300 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 3.6) at a ratio of 1:1:10. Samples (50 µL) were added to 1.5 mL of the TPTZ solution, and the absorbance at 595 nm was determined after the samples were incubated for 20 min. The results of the three methods were expressed as µmol Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid) equivalents/100 g DW.

Sensory evaluation

The sensory evaluation was carried out by 100 untrained panelists without previous experience with cookies. The panelists rated the sensorial attributes, such as color, texture, taste and aroma, of the tamarind pericarp cookies. The ratings were carried on a 9-point hedonic scale ranging from 9 (like extremely) to 1 (dislike extremely). Cookies were offered in a random order. The control cookies were made from wheat flour.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean values ± standard deviations. The data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 5.0 (2015, CA, USA) using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey test to validate any significant differences between the group means (p ≤ 0.05).

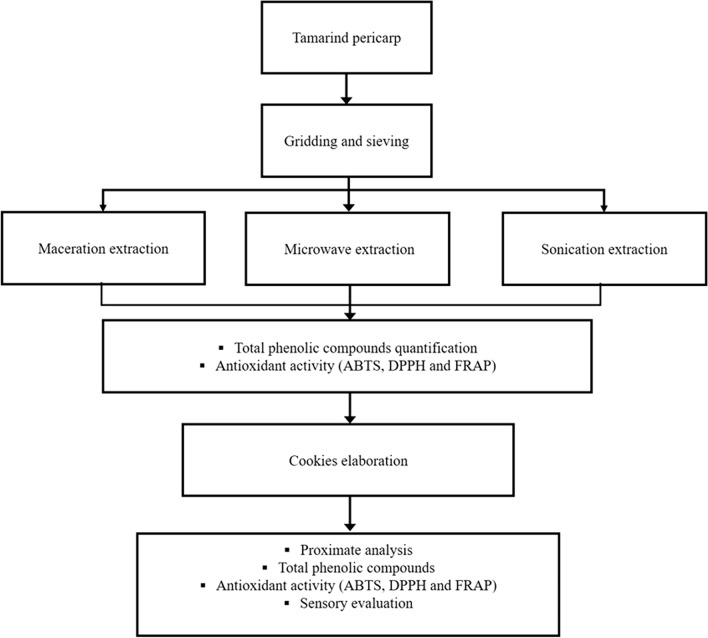

The general scheme of the processing and analysis of the tamarind pericarp in this study is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

General scheme of the processing and analysis of the tamarind pericarp

Results and discussion

Optimum conditions of pretreatment methods for tamarind pericarp and total phenolic content

The second order model-equation given as Eqs. 1, 2 and 3 were used to fit the independent and dependent variables and examined for goodness of fit.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

where A = time (in microwave is power), B = temperature, AB = time–temperature or power–time interaction, AB2 = quadratic effects and AB = time and temperature interaction. It was reported that the R2 should be at least 80% for a good fit model (Alifakı and Şakıyan 2017). The results showed that the models for all the response variables were adequate since R2 was > 80%.

According to the multiple regression analysis for maceration, both time and temperature had a significant influence on TPC extraction (p < 0.05). The impact of extraction temperature on phenolic compounds is higher when temperature increases (Castro-López et al. 2017); this improves extraction by decreasing the viscosity of the liquid, elevating the diffusion coefficient and improving the solubility of the polyphenols. Maceration extraction time is another factor that influences efficiency because a longer extraction time has a positive effect on the extraction of the compounds of interest (Boonchu and Utama 2015).

In the ultrasound pretreatment, temperature was a significant factor in TPC extraction. Higher temperatures may increase the rate of diffusion and solubility of many compounds, including antioxidant compounds. Extraction assisted by ultrasound reduces extraction times compared to extraction by maceration, which reduces the operating time of the equipment and therefore energy consumption. In the extraction assisted by ultrasound, a cavitation effect occurs, which favors the rupture of cell walls, releasing the phenolic compounds found in the pericarp (Šic Žlabur et al. 2015).

The multiple regression analysis for the microwave pretreatment showed that power and time were significant for TPC tamarind pericarp extraction (p < 0.05). In the microwave treatment, the extraction time diminishes because when exposed to non-ionizable electromagnetic waves, the humidity contained in the pericarp begins to evaporate, generating pressure inside the cell wall, causing a cellular rupture, facilitating the release of active compounds and allowing dissolution in solvent. Additionally, this increase in temperature causes a decrease in the viscosity of the solvent and an increase in its diffusion, increasing extraction efficiency (Ho et al. 2008).

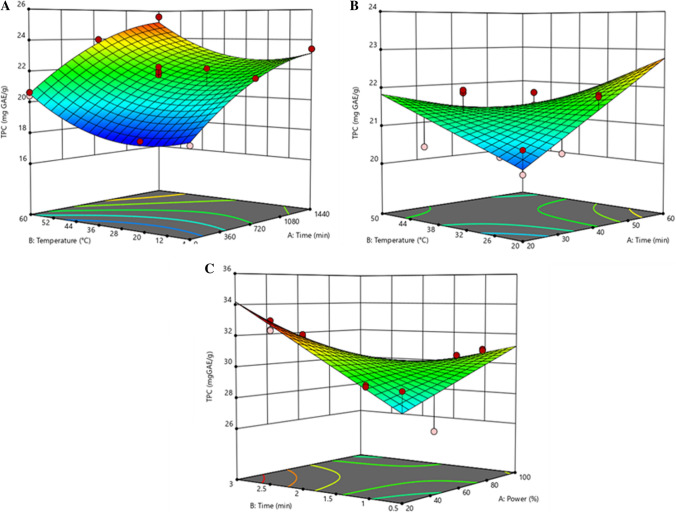

Figure 2a–c show the response surface graphs for pretreatment optimization of TPC availability in tamarind pericarp. Figure 2a shows that optimum maceration conditions were 1440 min and 60 °C. Using the optimum conditions found in the experimental designs, the TPC predicted in the present study was 25.17 mg GAE/g. The predicted total phenolic content was confirmed and validated by experimenting with optimized conditions, with an amount of 25.58 ± 0.51 mg GAE/g. Optimum conditions for ultrasound pretreatment were 54 min and 44 °C (Fig. 2b), with a predicted value of TPC of 23.27 mg GAE/g and an experimental value of 23.52 ± 0.38 mg GAE/g. Concerning microwave pretreatment, the best conditions for tamarind pericarp were 2.6 min and 224.9 W; the predicted value was 33.03 mg GAE/g and the TPC quantification was 33.61 ± 0.43 mg GAE/g (Fig. 2c). The predicted values agreed with the experimental values and were found to be not significantly different (p ≤ 0.5) using a paired t test, confirming that the model adequately reflected the expected optimization.

Fig. 2.

Response surface graphs for pretreatment optimization of total phenolic content (TPC) extraction from tamarind pericarp: a maceration, b ultrasound and c microwave

Microwaved tamarind pericarp presented significantly higher TPC availability than did the other two pretreatments. Drosou et al. (2015) and He et al. (2015) reported a similar result in which microwave processing, compared with the ultrasound method, presented better polyphenolic extraction from grape pomace. The highest availability of TPC after microwave pretreatment could be attributed to the microwave energy that may disrupt the cell wall and enhance the release of bioactive compounds from cell walls (Castro-López et al. 2017).

Additionally, the higher availability of TPC with a shorter extraction time by microwaves could be due to the molecular interaction with the electromagnetic field and a rapid transfer of energy to the raw sample water content (Dahmoune et al. 2015). Although ultrasound can break the cell wall with its cavitation power, releasing phenolic compounds into the extraction solvent, the quantity of release depends on the intensity and duration of application (Nayak et al. 2015). In our study, the ultrasound and maceration parameters selected for pretreatment produces a lower recovery of phenols.

Antioxidant capacity of tamarind pericarp powder

The results of the antioxidant capacity of tamarind pericarp obtained under the three pretreatment conditions measured by DPPH, ABTS and FRAP are shown in Table 2. The sample with the highest DPPH radical-scavenging capacity was pretreated with microwaves (282.50 ± 4.47 µmol TE/g), followed by the samples pretreated with sonication (232.19 ± 4.06 µmol TE/g) and maceration (202.00 ± 4.87 µmol TE/g). These results agree with Nayak et al. (2015), who reported that microwaved orange peels had better antioxidant capacity than ultrasound-treated orange peels.

Table 2.

TPC, DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP of tamarind pericarp samples with optimal pretreatment conditions

| Conditions | Maceration | Ultrasound | Microwave |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time: 1440 min | Time: 54 min | Time: 2.6 min | |

| Temperature: 60 °C | Temperature: 44 °C | Power: 224.9 W | |

| TPC mg GAE/g | 25.99 ± 0.37a | 23.70 ± 0.15b | 34.12 ± 0.55c |

| DPPH (µmol TE/g) | 202.00 ± 4.87a | 232.19 ± 4.06b | 282.50 ± 4.47c |

| ABTS (µmol TE/g) | 243.42 ± 24.27a | 327.60 ± 24.11b | 348.44 ± 23.81c |

| FRAP (µmol TE/g) | 285.88 ± 14.98a | 326.38 ± 10.28b | 371.71 ± 11.07c |

Values represent the mean ± standard deviation. Results in dry weight (DW)

TE Trolox equivalents

Mean values in the same row that are not followed by the same letter are significantly different (p ≤ 0.05) according to the Tukey test

The ABTS assay showed that microwave-pretreated tamarind pericarp had a higher antioxidant capacity compared to ultrasound and macerated extracts (348.44 ± 23.81, 327.60 ± 24.11 and 243.42 ± 24.47 µmol TE/g, respectively). The higher antioxidant capacity of microwaved tamarind pericarp could be explained by the breaking down of plant cells in a short time due to electromagnetic wave exposure (Dahmoune et al. 2015) that liberates greater amounts of bio compounds that can influence antioxidant capacity (Castro-López et al. 2017).

The FRAP results for maceration and ultrasound pretreatments were 285.88 ± 14.98 and 326.37 ± 10.28 µmol TE/g, respectively. Microwave pretreatment exhibited a higher antioxidant capacity in the reducing power assay (371.71 ± 11.07 µmol TE/g). This result could be attributed to the higher content of total phenolic compounds because of the action of hydroxyl groups, which might act as electron donors (Castro-López et al. 2017).

Proximate composition of tamarind pericarp

The proximal composition of raw tamarind pericarp was as follows (per 100 g): moisture 9.8 g, fat 2.0 g, protein 4.9 g, ash 3.4 g, carbohydrate 36 g and crude fiber 44 g. Crude fiber in tamarind pericarp was 1.2-fold higher than that in olive waste (34.14/100 g) (Uribe et al. 2014) and 1.8-fold more than that in roselle seed powder (24.7/100 g) (Nyam et al. 2014), whereby tamarind pericarp could even be a potential source of fiber, which is known for its health properties (Tril et al. 2014). Additionally, fiber traverses the small intestine linked to polyphenols, which enhances their absorption (Saura-Calixto 2011).

Antioxidant properties of doughs and cookies

Table 3 shows the phenolic compound and antioxidant capacity results for doughs and cookies with and without wheat flour substitution. The total phenolic content of the dough (D10TP) and cookies substituted with 10% of tamarind pericarp powder (C10TP) were 2.6-fold higher than those of control dough (CD) and cookies and 1.3-fold higher than dough and cookies with 5% tamarind pericarp substitution (C5TP).

Table 3.

Total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of control dough and doughs and cookies with 5 and 10% substitution per 100 g

| Sample | TPC (mg GAE) | DPPH (µmol TE) | ABTS (µmol TE) | FRAP (µmol TE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | 114.99 ± 0.02a | 7.82 ± 0.09a | 11.74 ± 0.23a | 12.51 ± 0.13a |

| D5TP | 183.98 ± 0.01b | 10.24 ± 0.09a | 14.08 ± 0.00a | 14.88 ± 0.20a |

| D10TP | 298.97 ± 0.03c | 21.14 ± 0.09b | 31.74 ± 0.30b | 33.86 ± 0.10b |

| CC | 155.38 ± 0.02a | 10.57 ± 0.09a | 15.87 ± 0.30a | 16.93 ± 0.13a |

| C5TP | 203.54 ± 0.02b | 13.85 ± 0.09a | 20.76 ± 0.00a | 22.43 ± 0.05a |

| C10TP | 407.18 ± 0.02c | 27.71 ± 0.09b | 41.59 ± 0.51b | 44.36 ± 0.15b |

Data expressed as the mean ± standard error. Results in dry weight

CD control dough, D5TP dough with 5% tamarind pericarp substitution, D10TP dough with 10% tamarind pericarp substitution, CC control cookie, C5TP cookie with 5% tamarind pericarp substitution, C10TP cookie with 10% tamarind pericarp substitution, GAE gallic acid equivalents, TE Trolox equivalents

Means with different superscripts in the same column differ significantly by Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05

As expected, the phenolic content in the dough in which the wheat flour was substituted for 10% tamarind pericarp increased significantly (p ≤ 0.05) compared with the control dough. Since wheat polyphenols are mainly concentrated in the bran fraction, refined wheat flour is low in polyphenolic content (Shafi et al. 2016). Thus, the 10% tamarind pericarp powder added to the cookies with refined wheat flour increased their phenolic content by 260%.

TPC in tamarind pericarp is mainly attributable to the presence of catechin, epicatechin and procyanidin, as reported by Kuru (2014), and gallic, vanillic, coumaric and protocatechuic acids and luteolin. Our result was 3.6-fold higher than that found by Giuberti et al. (2018) for alfalfa seed cookies (112.9 mg GAE/100 g). Similar increases in the bioactive content in biscuits was observed with the addition of flaxseed flour (Kaur et al. 2017a, b), water chestnut flour (Shafi et al. 2016) and Chenopodium album flour (Jan et al. 2016).

DPPH, ABTS and FRAP values for doughs and cookies are shown in Table 3. D10TP and C10TP presented 2.6-fold higher (p ≤ 0.05) levels of DPPH, ABTS and FRAP determinations compared to CD and CC. Moreover, there was a significant (p ≤ 0.05) 1.3-fold antioxidant capacity increase for D10TP and C10TP compared to C5TP. These results agreed with those found by Nyam et al. (2014), who made cookies with the addition of 20% seed powder from roselle pretreated with microwaves and dehydrated in a conventional oven, resulting in an increase in its nutritional and antioxidant properties compared with the biscuit made only with wheat flour.

In addition to the tamarind pericarp addition, the higher antioxidant capacity of C10TP may be due to the baking effect (Jan et al. 2016) and related with bound phenolics releasing from cellular constituents (Awolu et al. 2017); baking induces the production of Maillard reaction products such as melanoidins, which have been reported to have an antioxidant capacity (Awolu et al. 2017; Chauhan et al. 2015; Giuberti et al. 2018; Jan et al. 2016; Shafi et al. 2016; Žilić et al. 2016).

Sensory evaluation of cookies

According to the results, cookies with 10% substitution scored better than cookies with 5% pericarp substitution.

There are no significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) between C10TP and CC regarding texture, color, aroma and flavor. However, C10TP had an overall acceptability score of 9, “like extremely”, by the panelists. Comparable results were obtained by Giuberti et al. (2018), who made cookies using alfalfa seed flour and rice flour that received positive scores for overall acceptance, as well as Jan et al. (2016), who developed well-accepted cookies prepared with quinoa flour.

Proximate analysis of cookies

Proximate composition analysis, including moisture, fat, ash, protein, carbohydrates and fiber, was carried out on the most preferred cookie (C10TP) and the CC (Table 4).

Table 4.

Proximate composition of cookies with 10% tamarind pericarp substitution and control cookies per 100 g

| CC | C10TP | |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 7.21 ± 0.15* | 7.93 ± 0.05 |

| Fat | 5.57 ± 0.35 | 5.32 ± 0.26 |

| Fiber | 1.69 ± 0.36 | 7.05 ± 0.15 |

| Ash | 1.06 ± 0.02 | 1.21 ± 0.01 |

| Protein | 10.03 ± 0.29 | 9.50 ± 0.37 |

| Carbohydrate | 74.45 ± 0.97 | 68.99 ± 0.84 |

| Caloric content (kcal/100 g) | 388.01* | 361.83 |

Data expressed as the mean ± standard error

C10TP cookie with 10% substitution, CC control cookie

*Significate difference (p ≤ 0.05)

C10TP, compared with CC, did not present significant differences in fat and protein values. However, moisture, crude fiber, ash, carbohydrate values and energy content presented significant differences (p ≤ 0.05). The difference in moisture content between samples might be associated with the fiber content, as more hydroxyl groups from cellulose in fiber were able to bind with free water molecules through hydrogen bonding, resulting in a higher water holding capacity (Arun et al. 2015; Uthumporn et al. 2015). The higher ash content of the substituted cookies indicates that the cookies contain a higher mineral content than the control cookies (Cheng and Bhat 2016).

Cookie with 10% substitution presented a fourfold higher fiber value compared that of the control cookie. It is well-known that dietary fiber plays an essential role in the prevention of different diseases. Furthermore, diets with a high fiber content, such as those including cereals, fruits, and vegetables, have a positive effect on health; its consumption has been related to a lower incidence of several types of cancer (Awolu et al. 2017). Moreover, baking improves the fiber content of cookies due to the formation of fiber-protein complexes that are resistant to heating (Chauhan et al. 2015). The fiber content obtained in this study allows the tamarind pericarp cookie to be labeled as “high fiber” in the European Union (at least 6 g of fiber per 100 g) (Perez et al. 2017). Additionally, this high fiber content agrees with Mexican norm parameters (at least 2.5 g per portion).

The caloric content calculated for C10TP (361.83 kcal/100 g), was significantly different (p ≤ 0.05) from the caloric content calculated for CC (388.01 kcal/100 g).

Conclusion

Tamarind pericarp pretreated with microwaves could be considered a source of natural antioxidants and fiber. Microwave pretreatment of tamarind pericarp exhibited a higher increase in phenolic availability than did pericarp pretreated with sonication and maceration. It was possible to enhance the nutritional value of wheat flour cookies by adding 10% microwaved tamarind pericarp as a functional ingredient without significant sensory changes. In summary, tamarind pericarp could be a suitable option for functional food formulations. The results of this study might be useful for revealing the functional value of tamarind pericarp. However, a detailed cost analysis of pericarp processing with microwaves must be performed to determine the scale-up feasibility of this new process.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the financial support from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) Scholarship 574220 and Secretaría de Investigación y Posgrado (SIP)-Instituto Politécnico Nacional (IPN), Project No. 20170459.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alifakı YÖ, Şakıyan Ö. Dielectric properties, optimum formulation and microwave baking conditions of chickpea cakes. J Food Sci Technol. 2017;54(4):944–953. doi: 10.1007/s13197-016-2371-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . Official methods of analysis. 17. Washington: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arun KB, Persia F, Aswathy PS, Chandran J, Sajeev MS, Jayamurthy P, Nisha P. Plantain peel: a potential source of antioxidant dietary fibre for developing functional cookies. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52(10):6355–6364. doi: 10.1007/s13197-015-1727-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awolu OO, Omoba OS, Olawoye O, Dairo M. Optimization of production and quality evaluation of maize-based snack supplemented with soybean and tiger-nut (Cyperus esculenta) flour. Food Sci Nutr. 2017;5(1):3–13. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-López C, Ventura-Sobrevilla JM, González-Hernández MD, Rojas R, Ascacio-Valdés JA, Aguilar CN, Martínez-Ávila GCG. Impact of extraction techniques on antioxidant capacities and phytochemical composition of polyphenol-rich extracts. Food Chem. 2017;237:1139–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan A, Saxena DC, Singh S. Total dietary fibre and antioxidant activity of gluten free cookies made from raw and germinated amaranth (Amaranthus spp.) flour. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2015;63(2):939–945. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.03.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YF, Bhat R. Functional, physicochemical and sensory properties of novel cookies produced by utilizing underutilized jering (Pithecellobium jiringa Jack.) legume flour. Food Biosci. 2016;14:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2016.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cortez-García RM, Ortiz-Moreno A, Zepeda-Vallejo LG, Necoechea-Mondragón H. Effects of cooking methods on phenolic compounds in Xoconostle (Opuntia joconostle) Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2015;70(1):85–90. doi: 10.1007/s11130-014-0465-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahmoune F, Nayak B, Moussi K, Remini H, Madani K. Optimization of microwave-assisted extraction of polyphenols from Myrtus communis L. leaves. Food Chem. 2015;166:585–595. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drosou C, Kyriakopoulou K, Bimpilas A, Tsimogiannis D, Krokida M. A comparative study on different extraction techniques to recover red grape pomace polyphenols from vinification byproducts. Ind Crops Prod. 2015;75:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.05.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felix ACS, Santana RA, Valasques Junior GL, Bezerra MA, de Oliveira Neto NM, de Oliveira Lima E, de Oliveira Filho AA, Franco M, do Nascimento Junior BB. Application of experimental designs to evaluate the total phenolics content and antioxidant activity of cashew apple bagasse. Rev Mex Ing Quim. 2018;17(1):65–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesapillai M, Venugopal A, Simha P. Preliminary isolation, recovery and characterization of polyphenols from waste Tamarindus indica L. Mater Today Proc. 2017;4(9):10658–10661. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2017.06.438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giuberti G, Rocchetti G, Sigolo S, Fortunati P, Lucini L, Gallo A. Exploitation of alfalfa seed (Medicago sativa L.) flour into gluten-free rice cookies: nutritional, antioxidant and quality characteristics. Food Chem. 2018;239:679–687. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Lu Q, Liviu G. Effects of extraction processes on the antioxidant activity of apple polyphenols. CyTA J Food. 2015;13(4):603–606. doi: 10.1080/19476337.2015.1026403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CHL, Cacace JE, Mazza G. Mass transfer during pressurized low polarity water extraction of lignans from flaxseed meal. J Food Eng. 2008;89(1):64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2008.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jan R, Saxena DC, Singh S. Physico-chemical, textural, sensory and antioxidant characteristics of gluten: free cookies made from raw and germinated Chenopodium (Chenopodium album) flour. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2016;71:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur M, Singh V, Kaur R. Effect of partial replacement of wheat flour with varying levels of flaxseed flour on physicochemical, antioxidant and sensory characteristics of cookies. Bioact Carbohydr Diet Fibre. 2017;9:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bcdf.2016.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur P, Sharma P, Kumar V, Panghal A, Kaur J, Gat Y. Effect of addition of flaxseed flour on phytochemical, physicochemical, nutritional, and textural properties of cookies. J Saudi Soc Agric Sci. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jssas.2017.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuru P. Tamarindus indica and its health related effects. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4(9):676–681. doi: 10.12980/APJTB.4.2014APJTB-2014-0173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Natukunda S, Muyonga JH, Mukisa IM. Effect of tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.) seed on antioxidant activity, phytocompounds, physicochemical characteristics, and sensory acceptability of enriched cookies and mango juice. Food Sci Nutr. 2016;4(4):494–507. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak B, Dahmoune F, Moussi K, Remini H, Dairi S, Aoun O, Khodir M. Comparison of microwave, ultrasound and accelerated-assisted solvent extraction for recovery of polyphenols from Citrus sinensis peels. Food Chem. 2015;187:507–516. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.04.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyam KL, Leao SY, Tan CP, Long K. Functional properties of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) seed and its application as bakery product. J Food Sci Technol. 2014;51(12):3830–3837. doi: 10.1007/s13197-012-0902-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez C, Tagliani C, Arcia P, Cozzano S, Curutchet A. Blueberry by-product used as an ingredient in the development of functional cookies. Food Sci Technol Int. 2017;24(4):301–308. doi: 10.1177/1082013217748729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiroz-Reyes CN, Aguilar-Méndez MA, Ramírez-Ortíz ME, Ronquillo-De Jesús E. Comparative study of ultrasound and maceration techniques for the extraction of polyphenols from cacao beans (Theobroma cacao) Rev Mex Ing Quim. 2013;12(1):11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rao AS, Kumar AA. Tamarind seed processing and by-products. Agric Eng Int CIGR J. 2015;17(2):200–204. [Google Scholar]

- Real-de-Colima (2017) Tamarindo. http://realdecolima.mx/tamarind/estadisticas-tamarindo.html

- Salara RK, Purewala SS, Bhattiba MS. Optimization of extraction conditions and enhancement of phenolic content and antioxidant activity of pearl millet fermented with Aspergillus awamori MTCC-548. Resour Effic Technol. 2016;2(3):148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.reffit.2016.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saura-Calixto F. Dietary fiber as a carrier of dietary antioxidants: an essential physiological function. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59(1):43–49. doi: 10.1021/jf1036596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafi M, Baba WN, Masoodi FA, Bazaz R. Wheat-water chestnut flour blends: effect of baking on antioxidant properties of cookies. J Food Sci Technol. 2016;53(12):4278–4288. doi: 10.1007/s13197-016-2423-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Saxena DC, Riar CS. Nutritional, sensory and in vitro antioxidant characteristics of gluten free cookies prepared from flour blends of minor millets. J Cereal Sci. 2016;72:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2016.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Šic Žlabur J, Voća S, Dobričević N, Brncic M, Dujmić F, Rimac S. Optimization of ultrasound assisted extraction of functional ingredients from Stevia Rebaudiana Bertoni leaves. Int Agrophys. 2015;29:231–237. doi: 10.1515/intag-2015-0017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D, Wangchu L, Moond SK. Processed products of tamarind. Nat Prod Radiance. 2007;6(4):315–321. [Google Scholar]

- Tril U, Fernández-López J, Álvarez JÁP, Viuda-Martos M. Chemical, physicochemical, technological, antibacterial and antioxidant properties of rich-fibre powder extract obtained from tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.) Ind Crops Prod. 2014;55:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.01.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uribe E, Lemus-Mondaca R, Vega-Gálvez A, Zamorano M, Quispe-Fuentes I, Pasten A, Di Scala K. Influence of process temperature on drying kinetics, physicochemical properties and antioxidant capacity of the olive-waste cake. Food Chem. 2014;147:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.09.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uthumporn U, Woo WL, Tajul AY, Fazilah A. Physico-chemical and nutritional evaluation of cookies with different levels of eggplant flour substitution. CyTA J Food. 2015;13(2):220–226. doi: 10.1080/19476337.2014.942700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Žilić S, Kocadağlı T, Vančetović J, Gökmen V. Effects of baking conditions and dough formulations on phenolic compound stability, antioxidant capacity and color of cookies made from anthocyanin-rich corn flour. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2016;65:597–603. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.08.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]