Abstract

Objective

We aimed to determine the criterion validity of using diagnosis codes for hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) to identify infections.

Methods

Using linked laboratory and administrative data in Ontario, Canada, from January 2004 to December 2014, we validated HBV/HCV diagnosis codes against laboratory-confirmed infections. Performance measures (sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value) were estimated via cross-validated logistic regression and we explored variations by varying time windows from 1 to 5 years before (i.e., prognostic prediction) and after (i.e., diagnostic prediction) the date of laboratory confirmation. Subgroup analyses were performed among immigrants, males, baby boomers, and females to examine the robustness of these measures.

Results

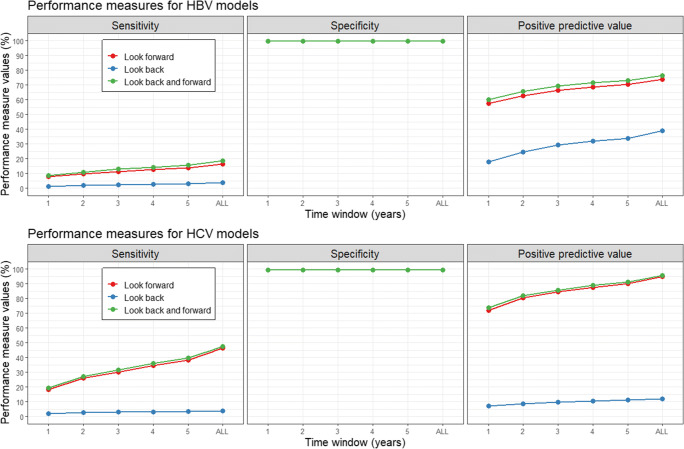

A total of 1,599,023 individuals were tested for HBV and 840,924 for HCV, with a resulting 41,714 (2.7%) and 58,563 (7.0%) infections identified, respectively. HBV/HCV diagnosis codes ± 3 years of laboratory confirmation showed high specificity (99.9% HBV; 99.8% HCV), moderate positive predictive value (70.3% HBV; 85.8% HCV), and low sensitivity (12.8% HBV; 30.8% HCV). Varying the time window resulted in limited changes to performance measures. Diagnostic models consistently outperformed prognostic models. No major differences were observed among subgroups.

Conclusion

HBV/HCV codes should not be the only source used for monitoring the population burden of these infections, due to low sensitivity and moderate positive predictive values. These results underscore the importance of ongoing laboratory and reportable disease surveillance systems for monitoring viral hepatitis in Ontario.

Supplementary Information

The online version of this article (10.17269/s41997-020-00435-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Viral hepatitis, Validation study, Health administrative data, Immigrants

Résumé

Objectif

Nous avons cherché à déterminer le critère de validité de l’utilisation des codes de diagnostic du virus de l’hépatite B (VHB) et du virus de l’hépatite C (VHC) pour identifier les infections.

Méthodes

En utilisant des données de laboratoire et administratives couplées en Ontario, au Canada, de janvier 2004 à décembre 2014, nous avons validé les codes de diagnostic du VHB/VHC contre les infections confirmées en laboratoire. Les mesures du rendement (sensibilité, spécificité et valeur prédictive positive) ont été estimées par régression logistique croisée et nous avons exploré les variations en variant les fenêtres temporelles de 1 à 5 ans avant (c.-à-d. prédiction pronostique) et après (c.-à-d. prédiction diagnostique) la date de confirmation en laboratoire. Des analyses de sous-groupes ont été effectuées auprès d’immigrants, d’hommes, de baby-boomers et de femmes pour examiner la robustesse de ces mesures.

Résultats

1 599 023 individus ont été testés pour le VHB et 840 924 pour le VHC, dont 41 714 (2,7 %) et 58 563 (7,0 %) infections ont été identifiées, respectivement. Les codes de diagnostic VHB/VHC ± 3 ans de confirmation en laboratoire ont montré une spécificité élevée (99,9 % VHB; 99,8 % VHC), une valeur prédictive positive modérée (70,3 % VHB; 85,8 % VHC) et une faible sensibilité (12,8 % VHB; 30,8 % VHC). La variation de la fenêtre temporelle a entraîné des changements limités aux mesures du rendement. Les modèles diagnostiques ont constamment surpassé les modèles pronostiques. Aucune différence majeure n’a été observée entre les sous-groupes.

Conclusion

Les codes VHB/VHC ne devraient pas être la seule source utilisée pour surveiller la charge de population de ces infections, en raison de la faible sensibilité et des valeurs prédictives positives modérées. Ces résultats soulignent l’importance des systèmes continus de surveillance des maladies à déclaration obligatoire en laboratoire pour surveiller l’hépatite virale en Ontario.

Mots-clés: Hépatite virale, étude de validation, données administratives sur la santé, immigrants

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are among the most burdensome infectious diseases in Ontario, Canada (Kwong et al. 2012). Infections are usually asymptomatic in the initial stages and often go undiagnosed for decades until liver damage, cirrhosis, hepatic failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma develop (Lee et al. 2014; Raffetti et al. 2016). Current therapies can significantly mitigate or eliminate viral progression if initiated early enough (Mutimer et al. 2014; Papatheodoridis et al. 2012); thus, early detection and treatment are paramount to reducing disease burden (Aschengrau and Sage III 2008).

Population-based surveillance is important for estimating HBV/HCV incidence and prevalence, and can be used to evaluate preventive and therapeutic strategies for management at the clinical and public health levels. However, due to costs, few large-scale studies use laboratory-confirmed measures of disease status, with most relying on health administrative data. Health administrative data are useful for monitoring disease burden and evaluating long-term health outcomes in a cost-effective and efficient manner, particularly when assessing completeness and equity of access to care and immunization coverage. Often, such information is needed to assess hard-to-reach subgroups or recognize where access to care may be suboptimal. However, such data may not always be valid or appropriate for use in public health settings, since diagnosis codes can be biased or systematically incorrect in an unbiased (random) way (Benchimol et al. 2011; Muggah et al. 2013; Park et al. 2018). This can lead to an inaccurate representation of population-level characteristics and produce spurious results that may be misleading at best, and result in wasted resources and attention of policy makers and public health practitioners (Van Walraven and Austin 2012).

To address this concern, in this study we sought to establish the criterion validity of using HBV/HCV diagnosis codes to identify viral hepatitis infections. This work aims to facilitate viral hepatitis surveillance and determine whether it is appropriate to use administrative data to produce population-based estimates of HBV/HCV disease burden overall and among underserved subpopulations. To achieve this objective, we used laboratory testing information from a large public health laboratory in Ontario, Canada, linked to health administrative data sources and explored the potential for variability in performance by time and various demographic subgroups.

Methods

Study design and linked data sources

In this retrospective study, we validated health administrative diagnosis codes against laboratory-confirmed results among a cohort of individuals tested at Public Health Ontario (PHO) between January 2004 and December 2014. PHO conducts primary serologic and nucleic acid amplification testing on serum, plasma, or whole blood specimens submitted by health professionals to verify the presence and status of HBV/HCV infections (PHO 2019). In addition, PHO serves as a reference laboratory for HBV and HCV testing to confirm the results obtained in hospital and community laboratories across Ontario. These records were linked to health administrative data held at ICES, including information on diagnosis codes from physician office visits, emergency department visits, same-day surgeries, and hospitalizations. ICES is an independent, non-profit research institute whose legal status under Ontario’s health information privacy law allows it to collect and analyze health care and demographic data, without consent, for health system evaluation and improvement. Physician office diagnosis and fee codes were recorded with an Ontario-specific modified version 8 of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) coding system, known as Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) codes. Emergency department visits, same-day surgeries, and hospitalizations were categorized by version 10 of the ICD coding system. Additionally, information on covariates and subgroups were obtained from linked data sources (see “Covariates” section). These datasets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES and administrative records were taken within the time window of January 1999 to December 2018.

Case definitions

Based on pre-defined Canadian case definitions, laboratory-confirmed infections were defined as a reactive antigen (HBsAg, HBeAg) test or HBV DNA detected for HBV, and a reactive HCV Ab test or HCV RNA detected for HCV (Public Health Agency of Canada 2014). Individuals meeting these criteria at any time during the study period were considered to have an infection at the time of testing, and the earliest date of infection was considered the date of laboratory confirmation. Diagnosis codes for HBV and HCV infections were identified through a systematic search of the annotated descriptors of ICD-9, ICD-10, and OHIP codes, using the following search terms: “hep*”, “hbv”, “hcv”, “chb”, “chc”, “type b”, and “type c”. A preliminary list of codes was compiled and reviewed prior to use. Any codes specifically identifying HBV or HCV infections were categorized as HBV- or HCV-specific codes. This yielded 8 HBV- and 3 HCV-specific diagnosis codes (Appendix 1), all from ICD-10 since Ontario switched from ICD-9 to ICD-10 in 2002 (Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) 2018). This is in contrast with other validation studies that have typically used ICD-9 or a mixture of ICD-9 and ICD-10.

Covariates

Additional demographic information on age, sex, and rural/urban place of residence was obtained from the Registered Persons Database. Year of birth was categorized into 10-year birth cohorts, and further grouped into baby boomer (i.e., the 1945–1965 birth cohort) (Galbraith et al. 2015) and those younger and older than baby boomers. Laboratory encounters compiled by PHO contain a free-text field indicating the reason for testing. Individuals undergoing prenatal testing were identified by scanning this field for the following search terms: “Prenatal”, “Pregnancy”, “Perinatal”, “Obstetr*”, and “Gynecol*”. As women may have multiple laboratory encounters, which may or may not be for prenatal reasons, the prenatal testing variable was dichotomized into those with and without a history of prenatal testing. Urban/rural place of residence was obtained via a 6-digit postal code, representing their place of residence at the date of their first test documented by PHO. Similarly, residential instability and material deprivation quintiles were obtained using the Ontario Marginalization Index (ON-MARG), multifaceted aggregate measures of socio-economic position that have been validated within the Canadian context at the neighbourhood census level (Pampalon et al. 2012). Immigration status was derived from the Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) permanent resident dataset. This includes information on country and world region of birth, which was further categorized into HBV-endemic (i.e., HBsAg prevalence > 8%) and HCV-endemic (i.e., HCV Ab prevalence > 2%) countries (Greenaway et al. 2018; Rossi et al. 2012). Since IRCC records only date back to January 1985, we were unable to identify individuals who migrated to Ontario prior to this date. We therefore grouped the study population into immigrants (i.e., foreign-born individuals migrating to Ontario after January 1985) and long-term residents (i.e., those born in Canada or who migrated to Canada prior to 1985).

Eligibility

Ontario residents undergoing HBsAg, HBeAg, HBV DNA, HCV Ab, or HCV RNA confirmatory, screening, or follow-up testing by PHO laboratory during the study period were eligible for enrollment into this study. Excluded were laboratory records not linked to health administrative data (e.g., non-OHIP recipients of PHO testing), and individuals with inadequate laboratory testing information to define a laboratory-confirmed infection. Those with laboratory-confirmed infections documented by PHO before January 2004 were also excluded from further analyses, including subsequent hospitalization or emergency visits.

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics of the HBV and HCV laboratory cohorts were compared to the population of Ontario. Performance measures, including sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value, were estimated using cross-validated logistic regression models, where the dependent and independent variables were laboratory-confirmed infections and health administrative HBV-/HCV-specific diagnosis codes, respectively. We also computed the F-score (i.e., a harmonic mean of sensitivity and positive predictive value), which is a useful measure of test accuracy. Models were parameterized on a random sample of 75% of the data and used to predict infections within the remaining 25%; performance measures were estimated from the prediction process. Histograms were used to illustrate the temporal distribution of diagnosis codes relative to the date of laboratory testing, including contrasts between the earliest and nearest recorded diagnosis code. Variations in performance were examined in 1-year increments before and after the date of laboratory testing, up to and including 5 years. Models only including codes that occur before the date of laboratory testing are known as prognostic prediction models, whereas all other models are considered diagnostic prediction models. Stratified analyses were conducted by sex, immigrant status, HBV-/HCV-endemic country of birth, birth cohort, and those with a history of prenatal testing. Additionally, true negatives vs. false negatives and true positives vs. false positives were compared to assess the potential for systematic biases.

All statistical comparisons of demographic groups were made using standardized difference measures. Data management was conducted using SAS-Enterprise guide software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). All other analyses and comparisons were conducted in the R statistical software environment. Ethics board approval was obtained from the University of Toronto (Protocol #37273 and #33766).

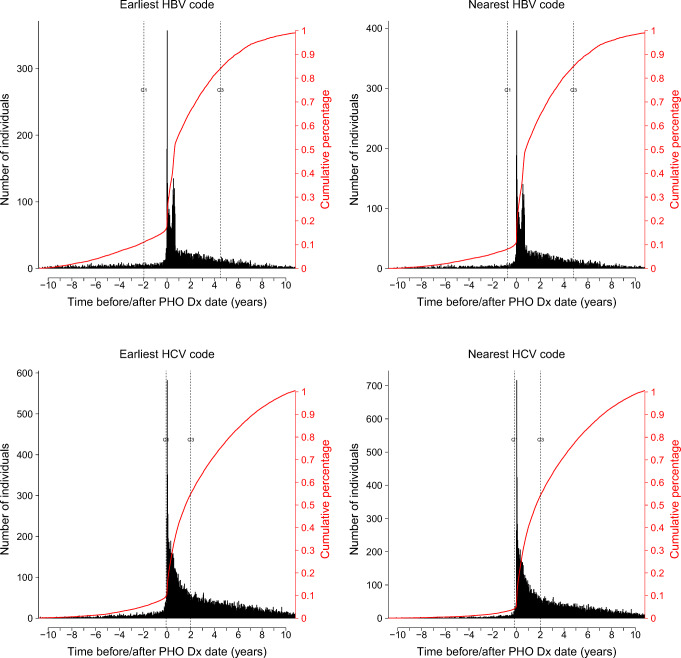

Results

In total, there were 2,029,940 individuals considered for inclusion into this study: 29,834 (1.5%) were excluded since they had laboratory-confirmed infections documented by PHO prior to December 2003, leaving 2,000,106 individuals who were grouped into two overlapping cohorts of 1,831,203 for HBV and 840,924 for HCV. For HBV, 232,180 (12.7%) had inadequate test results to define a laboratory-confirmed infection (i.e., only immunology was assessed) leaving 1,599,023 individuals who were tested for HBsAg, HBeAg, or HBV DNA tests, which yielded 41,714 (2.7%) infections. For HCV, all individuals were tested for presence of HCV Ab or HCV RNA, with 58,563 (7.0%) infections identified. Those tested for HBV tended to be younger, female, living in the highest instability and deprivation quintile neighbourhoods, and less likely to be migrants from European and HCV endemic countries, compared with the Ontario general population (Table 1). Those tested for HCV tended to be younger, more likely to reside in higher instability and deprivation quintile neighbourhoods, and less likely to be migrants from European and HBV/HCV endemic countries. Those excluded tended to be younger, less likely to have a history of prenatal testing, and less likely to be classified as an immigrant (Appendix 2). Histogram plots show that most diagnosis codes occur after the date of laboratory testing, with no major difference between the earliest and nearest codes (Fig. 1). There were 3256 (0.2%) individuals with administrative codes before HBV diagnosis and 8373 (1.0%) individuals with admin codes before HCV diagnosis.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic characteristics of the HBV and HCV cohorts against the Ontario population

| Tested for HBV (n = 1,599,023) | Standardized difference (tested for HBV vs. Ontario) | Tested for HCV (n = 840,924) | Standardized difference (tested for HCV vs. Ontario) | Ontario population* (n = 12,160,290) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth cohort | |||||

| < 1945 | 84,384 (5.3) | 0.26 | 103,199 (12.3) | 0.08 | 1,987,035 (16.3) |

| 1945–1954 | 67,116 (4.2) | 0.22 | 84,875 (10.1) | 0.05 | 1,522,125 (12.5) |

| 1955–1964 | 113,202 (7.1) | 0.21 | 123,638 (14.7) | 0.03 | 1,990,495 (16.4) |

| 1965–1974 | 372,273 (23.3) | 0.16 | 147,508 (17.5) | 0.06 | 1,766,005 (14.5) |

| 1975–1984 | 362,020 (22.6) | 0.19 | 194,273 (23.1) | 0.20 | 1,522,260 (12.5) |

| 1985–1994 | 295,340 (18.5) | 0.09 | 159,812 (19.0) | 0.10 | 1,658,190 (13.6) |

| > 1994 | 33,044 (2.1) | 0.32 | 26,780 (3.2) | 0.28 | 1,714,180 (14.1) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 1,251,521 (78.3) | 0.42 | 435,158 (51.7) | 0.01 | 6,229,555 (51.2) |

| Male | 345,857 (21.6) | 0.42 | 404,927 (48.2) | 0.01 | 5,930,735 (48.8) |

| History of prenatal screening | |||||

| No | 683,358 (42.7) | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 915,665 (57.3) | – | – | – | – |

| Rural place of residence | |||||

| No | 1,412,452 (88.3) | 0.07 | 724,238 (86.1) | 0.02 | 10,351,143 (85.1) |

| Yes | 173,116 (10.8) | 0.09 | 107,421 (12.8) | 0.04 | 1,809,147 (14.9) |

| Immigration status | |||||

| Long-term resident | 1,225,771 (76.7) | 0.09 | 709,644 (84.4) | 0.23 | 8,606,355 (70.8) |

| Immigrant† | 373,252 (23.3) | 0.07 | 131,280 (15.6) | 0.21 | 3,398,725 (27.9) |

| African | 31,882 (2.0) | 0.04 | 13,830 (1.6) | 0.02 | 164,795 (1.4) |

| Americas | 59,466 (3.7) | 0.02 | 25,579 (3.0) | 0.05 | 534,460 (4.4) |

| Asia and Middle East | 223,266 (14.0) | 0.06 | 65,769 (7.8) | 0.08 | 1,376,595 (11.3) |

| Europe | 52,379 (3.3) | 0.21 | 21,513 (2.6) | 0.24 | 1,307,885 (10.8) |

| Oceania | 799 (0.0) | 0.01 | 215 (0.0) | 0.02 | 11,870 (0.1) |

| HBV endemic | 137,123 (8.6) | 0.02 | 44,663 (5.3) | 0.11 | 1,142,685 (9.4) |

| HCV endemic | 54,382 (3.4) | 0.11 | 20,500 (2.4) | 0.15 | 849,010 (7.0) |

| Neighbourhood instability quintile | |||||

| Q1 (lowest) | 267,300 (16.7) | 0.17 | 124,409 (14.8) | 0.21 | 3,239,963 (26.6) |

| Q2 | 276,902 (17.3) | 0.05 | 137,978 (16.4) | 0.07 | 2,448,836 (20.1) |

| Q3 | 268,463 (16.8) | 0.02 | 140,890 (16.8) | 0.02 | 1,935,119 (15.9) |

| Q4 | 310,566 (19.4) | 0.02 | 165,479 (19.7) | 0.03 | 2,202,858 (18.1) |

| Q5 (highest) | 428,108 (26.8) | 0.15 | 239,704 (28.5) | 0.18 | 2,178,304 (17.9) |

| Neighbourhood deprivation quintile | |||||

| Q1 (lowest) | 327,934 (20.5) | 0.07 | 161,256 (19.2) | 0.10 | 3,032,107 (24.9) |

| Q2 | 276,153 (17.3) | 0.09 | 143,284 (17.0) | 0.10 | 2,730,484 (22.5) |

| Q3 | 285,908 (17.9) | 0.04 | 147,848 (17.6) | 0.04 | 2,439,314 (20.1) |

| Q4 | 297,738 (18.6) | 0.03 | 156,843 (18.7) | 0.04 | 2,036,021 (16.7) |

| Q5 (highest) | 363,606 (22.7) | 0.15 | 199,229 (23.7) | 0.17 | 1,767,154 (14.5) |

Frequencies may not sum to the total for selected variables due to variables with missing information

*Information for the population of Ontario taken from the Canadian Socioeconomic Database (CANSIM) from Statistics Canada for 2006 (Catalogue number: 97-551-XCB2006008 and 97-557-XCB2006007)

†For those tested for HBV and HCV, this represents individuals immigrating to Canada after 1985. Proportions among world regions add up to foreign-born immigrants

Fig. 1.

Histograms showing the time between the nearest and earliest HBV-/HCV-specific administrative code and the date of PHO laboratory-confirmed diagnosis

For HBV, low sensitivity (1.3–20.7%), high specificity (99.8%), and moderate positive predictive values (18.0–78.0%) were observed across all models and time windows, with diagnostic models generally showing increased performance (Fig. 2). Similar trends were observed for HCV models: low sensitivity (2.2–43.9%), high specificity (99.3%), moderate positive predictive values (7.2–62.0%), and increased performance for diagnostic models. Higher sensitivity and positive predictive values were observed for both HBV and HCV when increasing the time window, with stable specificity values throughout. Performance values were relatively consistent across all subgroups using a time window of ± 3 years (Table 2). For HBV, those who were incorrectly classified (i.e., false negatives and false positives) were more likely to be older, males, classified as immigrants from Asia and Middle Eastern countries or from HBV-endemic countries, and residing in urban areas and neighbourhoods with the lowest instability quintile, compared with those who were correctly classified (Table 3). Similar age-sex trends were observed for HCV, along with a higher concentration of those incorrectly classified among higher neighbourhood instability and deprivation quintiles. These observations were more pronounced among true negative to false negative comparisons, as compared with true positive to false positive comparisons (Appendix 3). Parameter estimates for the trained logistic regression models are presented for the interested reader (Appendix 4).

Fig. 2.

Performance measures of HBV/HCV diagnosis codes for identifying laboratory-confirmed infections

Table 2.

Performance measures of HBV/HCV diagnosis codes for identifying laboratory-confirmed HBV/HCV infections, stratified by at-risk subgroups, using a ± 3-year time window

| HBV | HCV | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | F score | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | F score | |

| Overall | 12.8 | 99.9 | 70.3 | 0.216 | 30.8 | 99.8 | 85.8 | 0.454 |

| Males | 12.5 | 99.9 | 69.9 | 0.212 | 29.4 | 99.8 | 86.5 | 0.438 |

| Females | 12.8 | 99.9 | 70.3 | 0.216 | 31.4 | 99.8 | 85.6 | 0.46 |

| Long-term residents | 13.2 | 99.9 | 71.6 | 0.222 | 30.6 | 99.8 | 85.6 | 0.45 |

| Immigrants | 11.1 | 99.9 | 65.1 | 0.19 | 31.6 | 99.8 | 86.7 | 0.464 |

| HBV non-endemic countries | 10.9 | 99.9 | 65.4 | 0.186 | – | – | – | – |

| HBV endemic countries | 11.6 | 99.9 | 64.6 | 0.196 | – | – | – | – |

| HCV non-endemic countries | – | – | – | – | 31.8 | 99.8 | 86.7 | 0.466 |

| HCV endemic countries | – | – | – | – | 30.8 | 99.8 | 86.5 | 0.454 |

| Older than baby boomers | 10.9 | 99.9 | 67.3 | 0.188 | 28.4 | 99.8 | 84.6 | 0.426 |

| Baby boomers | 11.3 | 99.9 | 68.1 | 0.194 | 31.7 | 99.8 | 89.3 | 0.468 |

| Younger than baby boomers | 13.2 | 99.9 | 70.8 | 0.222 | 30.8 | 99.8 | 85.3 | 0.452 |

| Non-prenatal testers | 12.2 | 99.9 | 69.5 | 0.208 | – | – | – | – |

| Prenatal testers | 13.3 | 99.9 | 71.1 | 0.224 | – | – | – | – |

Table 3.

Comparison of demographic characteristics of discordant pairs

| HBV | HCV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correctly classified | Incorrectly classified | Standardized difference | Correctly classified | Incorrectly classified | Standardized difference | |

| (n = 448,168) | (n = 9668) | (n = 198,743) | (n = 11,104) | |||

| Birth cohort | ||||||

| < 1945 | 23,106 (5.2) | 788 (8.2) | 0.09 | 24,984 (12.6) | 799 (7.2) | 0.13 |

| 1945–1954 | 20,628 (4.6) | 1366 (14.1) | 0.23 | 19,120 (9.6) | 1863 (16.8) | 0.15 |

| 1955–1964 | 35,788 (8.0) | 2337 (24.2) | 0.32 | 27,688 (13.9) | 3391 (30.5) | 0.29 |

| 1965–1974 | 100,508 (22.4) | 2294 (23.7) | 0.02 | 34,480 (17.3) | 2256 (20.3) | 0.05 |

| 1975–1984 | 166,922 (37.2) | 2001 (20.7) | 0.26 | 46,841 (23.6) | 1692 (15.2) | 0.15 |

| 1985–1994 | 89,623 (20.0) | 764 (7.9) | 0.25 | 39,083 (19.7) | 834 (7.5) | 0.25 |

| > 1994 | 11,142 (2.5) | 101 (1.0) | 0.08 | 6396 (3.2) | 226 (2.0) | 0.05 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 344,007 (76.8) | 4374 (45.2) | 0.48 | 104,453 (52.6) | 3993 (36.0) | 0.24 |

| Male | 103,710 (23.1) | 5277 (54.6) | 0.48 | 94,139 (47.4) | 7068 (63.7) | 0.23 |

| History of prenatal screening | ||||||

| No | 220,295 (49.2) | 8459 (87.5) | 0.64 | – | – | – |

| Yes | 227,873 (50.8) | 1209 (12.5) | 0.64 | – | – | – |

| Rural place of residence | ||||||

| No | 392,938 (87.7) | 9460 (97.8) | 0.28 | 171,107 (86.1) | 9716 (87.5) | 0.03 |

| Yes | 51,450 (11.5) | 130 (1.3) | 0.30 | 25,746 (13.0) | 1066 (9.6) | 0.08 |

| Immigration status | ||||||

| Long-term resident | 350,804 (78.3) | 4200 (43.4) | 0.54 | 167,585 (84.3) | 9498 (85.5) | 0.02 |

| Immigrant* | 97,365 (21.7) | 5468 (56.6) | 0.54 | 31,158 (15.7) | 1606 (14.5) | 0.02 |

| African | 8446 (1.9) | 370 (3.8) | 0.08 | 3327 (1.7) | 164 (1.5) | 0.01 |

| Americas | 16,536 (3.7) | 137 (1.4) | 0.10 | 6212 (3.1) | 124 (1.1) | 0.10 |

| Asia and Middle East | 56,302 (12.6) | 4586 (47.4) | 0.58 | 15,550 (7.8) | 902 (8.1) | 0.01 |

| Europe | 14,375 (3.2) | 280 (2.9) | 0.01 | 5018 (2.5) | 342 (3.1) | 0.02 |

| Oceania | 208 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.02 | 49 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.02 |

| HBV endemic | 33,332 (7.4) | 4240 (43.9) | 0.65 | 10,691 (5.4) | 508 (4.6) | 0.03 |

| HCV endemic | 14,699 (3.3) | 318 (3.3) | 0.00 | 4668 (2.3) | 451 (4.1) | 0.07 |

| Neighbourhood instability quintile | ||||||

| Q1 (lowest) | 74,817 (16.7) | 2388 (24.7) | 0.14 | 29,615 (14.9) | 1185 (10.7) | 0.09 |

| Q2 | 78,850 (17.6) | 1545 (16.0) | 0.03 | 3303 (1.7) | 1380 (12.4) | 0.30 |

| Q3 | 76,580 (17.1) | 1212 (12.5) | 0.09 | 33,655 (16.9) | 1540 (13.9) | 0.06 |

| Q4 | 86,874 (19.4) | 1528 (15.8) | 0.07 | 39,150 (19.7) | 2382 (21.5) | 0.03 |

| Q5 (highest) | 118,001 (26.3) | 2832 (29.3) | 0.05 | 56,016 (28.2) | 3950 (35.6) | 0.11 |

| Neighbourhood deprivation quintile | ||||||

| Q1 (lowest) | 93,030 (20.8) | 1644 (17.0) | 0.07 | 38,786 (19.5) | 1281 (11.5) | 0.16 |

| Q2 | 78,893 (17.6) | 1572 (16.3) | 0.03 | 34,344 (17.3) | 1428 (12.9) | 0.09 |

| Q3 | 80,156 (17.9) | 1784 (18.5) | 0.01 | 34,991 (17.6) | 1860 (16.8) | 0.02 |

| Q4 | 82,925 (18.5) | 2126 (22.0) | 0.06 | 36,888 (18.6) | 2204 (19.8) | 0.02 |

| Q5 (highest) | 100,118 (22.3) | 2379 (24.6) | 0.04 | 46,430 (23.4) | 3664 (33.0) | 0.15 |

Frequencies may not sum to the total for selected variables due to variables with missing information

*For those tested for HBV and HCV, this represents individuals immigrating to Canada after 1985. Proportions among world regions add up to foreign-born immigrants

Discussion

Health administrative data has the potential to be a valuable resource for public health purposes, including monitoring and surveillance of viral hepatitis in Ontario; however, this potential is not yet realized as the HBV-/HCV-specific diagnosis codes are suboptimal for producing population-level incidence/prevalence measures. The main concern regarding the validity of HBV-/HCV-specific diagnosis codes is that they do not identify a large proportion of individuals with laboratory-confirmed HBV/HCV infections diagnosed by PHO. These codes are not appropriate for estimating population prevalence but may be suitable for establishing a cohort of individuals living with infections because they are accurate among those who are identified and appear to be robust across different demographic subgroups. These results are consistent with validation studies conducted in the United States and England, which show comparable specificity and positive predictive value estimates (Allen-Dicker and Klompas 2012; Klompas et al. 2008; Kramer et al. 2008; Lattimore et al. 2014; Mahajan et al. 2013; Nui et al. 2015). However, the low sensitivity observed in Ontario contrasts with their findings, which generally ranged between 73% and 98%. Several system-level characteristics in Ontario may explain these differences. There are few HBV-/HCV-specific diagnosis codes in Ontario’s health administrative management systems, none of which can be used to identify physician office visits. Most physician office visits in Ontario are captured in the OHIP database, which does not contain codes specific to HBV or HCV infections, unlike health records management systems in the USA or England. In a post hoc analysis, we identified all individuals in Ontario with at least one inpatient HBV or HCV administrative code present on their health administrative record, and showed that the overall results do not substantially change (Appendix 5). This further emphasizes the importance of adopting HBV-/HCV-specific outpatient diagnosis or fee codes before low-cost viral hepatitis surveillance is a reality. The only potentially relevant code in this database is the “070” code—defined as any viral hepatitis—and was not considered for this study due to its ambiguity. Individuals with less severe infections may be diagnosed with HBV or HCV but do not appear in the health administrative records because they only present to physician office settings, leading to low sensitivity of the administrative data. This observation underscores the need for updated diagnosis codes for physician office visits in Ontario, not only to improve oversight of the health care system but also to enable evaluation of important treatment and prevention programs.

HBV/HCV prevalence is known to be higher among migrants from specific endemic world regions (Sharma et al. 2015) and testing for HBV/HCV among these groups is recommended rather than mandated by screening guidelines in Canada (Pottie et al. 2011; Swinkels et al. 2011). Immigrants may be getting tested, but do not attend subsequent health care follow-up visits, possibly due to access-to-care issues including language barriers, unfamiliarity with the health care system, or stigma and fear of deportation or persecution (Reitmanova et al. 2015). This supposition is supported by results from the discordant pair subanalysis, which shows that for HBV there was a higher proportion of foreign-born immigrants among those classified as false negatives, compared with true negatives. Stratification by world region reinforces this point, showing that those migrating from Asia and Middle Eastern countries and HBV-endemic countries were predominantly driving this difference. Additionally, during the study period, the Canadian screening guidelines for HCV did not recommend screening among the baby boomer generation (Grad et al. 2017; Shah et al. 2018). Baby boomers account for approximately 25% of those tested for HCV and approximately 50% of infections. This subgroup is known to have elevated rates of HCV infections for multiple reasons (Galbraith et al. 2015; Ti et al. 2017), and is over-represented among those classified as false negatives, more specifically among those born between 1955 and 1964. Boomers may be getting tested for HCV but not subsequently followed up or accessing care, and thus not being registered in the health administrative data and are classified as false negatives. We speculate that this may be due to a higher prevalence of lifetime injection drug use among boomers compared to subsequent birth cohorts (Armstrong 2007; Shiffman 2018), which potentially creates barriers due to stigma from previous at-risk behaviours, or that they may have developed other co-morbidities that are prioritized over HCV care.

Diagnostic and prognostic prediction

Prognostic models can provide valuable information to public health practitioners and researchers for forecasting as they may identify laboratory-confirmed infections before they occur. Such models are useful for making predictions outside of the study period/population and speak to the generalizability and robustness of the predictions. These models are useful for determining the incidence of viral hepatitis, since they conserve the temporal relationship between diagnosis codes and laboratory-confirmed infections. Diagnostic models are equally important but do not provide the same level of information, since they ignore the temporal relationship between diagnosis codes and laboratory-confirmed infections. Rather, diagnostic models determine whether an individual has a laboratory-confirmed infection given that they have a diagnosis code present in their health administrative record. These models can be used to determine disease prevalence in the absence of laboratory confirmation and are useful to public health researchers for planning interventions. We show that HBV-/HCV-specific codes generally occur after a PHO confirmation, which is likely a consequence of physicians using test results from PHO to assign diagnosis codes on patients’ health administrative records. Possible reasons for HBV-/HCV-specific administrative codes occurring prior to laboratory tests could be a diagnosis that was not captured by PHO or where the attending physician had enough evidence to make a diagnosis without confirmatory testing by PHO. It is also possible that delays in documentation of health administrative codes could contribute to the observed results, as is evident from an increase in the frequency seen just before the diagnosis time point in Fig. 1. We conducted a post hoc sensitivity analysis to look at changes in the number of those diagnosed prior to laboratory-confirmed infections over time and noticed minor differences across the study period (Appendix 5). As a result of these limitations, prognostic models should be interpreted with caution.

Limitations

The main limitation in this study is that PHO does not perform all viral hepatitis serology in Ontario, and due to the dependence of laboratory testing and diagnosis code assignment, there is the possibility of introducing bias. PHO does perform the vast majority of nucleic acid testing for HBV and HCV in the province. We cannot rule out the possibility of selection bias within the study population, as there is evidence of age and sex differences between the PHO cohort and the population of Ontario, which is to be expected since laboratory tests are prioritized among certain groups. It is possible that gold standard used for our study may be imperfect, as false negative and false positive results could be obtained from antibody, serology, and NAATs used to confirm infections. However, since the sensitivity and specificity for all antibody, serology, and NAATs across the study period was > 98%, we do not expect the overall results to change drastically. Those with laboratory-confirmed diagnoses occurring in 2014 only had a maximum of 4 years of follow-up after their diagnosis. However, we do not expect that the observed results would be affected in any major way by this limitation as relatively few individuals had their first health administrative diagnosis code occurring > 4 years after their laboratory diagnosis. These limitations highlight the inherent difficulties of working with secondarily collected data.

Conclusion

The health administrative diagnosis codes in Ontario predict HBV/HCV infections with varying performance values. With low sensitivity, these codes should be used with caution for measuring burden of disease, program monitoring, or evaluation at the population level, since the results are most likely an under-representation of the true burden. However, with the information presented in this study, public health researchers can have an approximate estimate of the proportion of HBV/HCV infections not captured by health administrative data. They can additionally have a look at the temporal consistency of predicted trends and use context-specific knowledge of their population(s) to guide practice. With moderate positive predictive values, these codes may be used for cohort creation, as those individuals identified by health administrative data as having an HBV/HCV infection are likely to have laboratory-confirmed infections. However, the created cohort is not likely to be representative of the larger population of Ontario due to the selective exclusion of individuals from physician office visits, which is suspected to include mostly younger individuals with less severe infections.

These findings highlight that health administrative data alone are insufficient for suitable public health surveillance and reinforce the importance of ongoing laboratory and reportable disease surveillance systems for monitoring the burden of viral hepatitis. Potential gains in diagnostic performance by combining HBV-/HCV-specific codes with additional information from the health administrative records has yet to be explored. Such information from the health administrative record could include pharmaceutical codes, demographic characteristics, documented comorbidities, at-risk behaviours, or other variables potentially related to viral hepatitis infections. We preliminarily investigated some of these factors in our analyses through stratification, but further work is needed to fully explore this space. Initiatives that could provide increased public health access to private and hospital laboratory data, in addition to PHO confirmatory testing, would vastly improve surveillance capabilities. The Ontario health care system should also consider improving documentation of its diagnosis and fee codes. This could include modernizing the current billing claim management system to record diagnoses with a more updated version of ICD, or at the least introduce specific viral hepatitis diagnosis codes to more accurately document infections. Such efforts could help inform improvements to equitable access to care among those living with HBV/HCV infections.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOC 237 kb)

Acknowledgements

Abdool Yasseen conducted this research in partial fulfilment of his PhD dissertation at the University of Toronto. A Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant (Grant #: 130553) facilitated the migration and linkage of laboratory data from PHO to ICES. In addition, Abdool Yasseen is supported by a national scholarship from the Canadian Hepatitis C Research Network (CanHepC). CanHepC is funded by a joint initiative of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (NHC-142832) and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC).

Funding

This research, conducted as part of the Canadian Network on Hepatitis C (CanHepC), is funded by a joint initiative of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (NHC-142832) and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Abdool Yasseen received a fellowship from CanHepC along with the Ontario Graduate Studentship award, and a departmental scholarship from the University of Toronto. This study was supported by Public Health Ontario (PHO) and ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC).

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethics board approval was obtained from the University of Toronto (Protocol #37273 and #33766).

Disclaimer

The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by CIHI, PHO, ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. The analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statement expressed herein are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of CIHI.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Allen-Dicker J, Klompas M. Comparison of electronic laboratory reports, administrative claims, and electronic health record data for acute viral hepatitis surveillance. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2012;18(3):209–214. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e31821f2d73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong GL. Injection drug users in the United States, 1979–2002: an aging population. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167(2):166–173. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschengrau, A., & Sage III, G. R. (2008). Essentials of epidemiology in public health (2nd ed.). Sudbury: Jones and Bartlett.

- Benchimol EI, et al. Development and use of reporting guidelines for assessing the quality of validation studies of health administrative data. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011;64(8):821–829. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). 2018. ICD-10-CA/CCI implementation schedule. https://www.cihi.ca/en/icd-10-cacci-implementation-schedule.

- Galbraith JW, et al. Unrecognized chronic hepatitis C virus infection among baby boomers in the emergency department. Hepatology. 2015;61(3):776–782. doi: 10.1002/hep.27410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grad, R., et al. (2017). Recommendations on hepatitis C screening for adults. CMAJ, 189(16), E594–E604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Greenaway, C., Makarenko, I., Tanveer, F., & Janjua, N. Z. (2018). Addressing hepatitis C in the foreign-born population: a key to hepatitis C virus elimination in Canada. Canadian Liver Journal, 1(2), 34–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Klompas M, et al. Automated identification of acute hepatitis B using electronic medical record data to facilitate public health surveillance. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):3–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JR, et al. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2008;27(3):274–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong, J. C., Ratnasingham, S., Campitelli, M. A., Daneman, N., Deeks, S. L., Manuel, D. G., Allen, V. G., Bayoumi, A. M., Fazil, A., Fisman, D. N., Gershon, A. S. (2012). The impact of infection on population health: results of the Ontario Burden of Infectious Diseases Study. PLoS One, 7(9), e44103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lattimore S, et al. Using surveillance data to determine treatment rates and outcomes for patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2014;59(4):1343–1350. doi: 10.1002/hep.26926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M-H, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of hepatitis C virus infection. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20(28):9270–9280. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan R, et al. Use of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, coding in identifying chronic hepatitis B virus infection in health system data: implications for national surveillance. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2013;20(3):441–445. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muggah E, Graves E, Bennett C, Manuel DG. Ascertainment of chronic diseases using population health data: a comparison of health administrative data and patient self-report. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutimer D, et al. Clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. Journal of Hepatology. 2014;60(2):392–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nui B, Forde KA, Goldberg DS. Coding algorithms for identifying patients with cirrhosis and hepatitis B or C virus using administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2015;24:107–111. doi: 10.1002/pds.3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampalon R, et al. An area-based material and social deprivation index for public health in Quebec and Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2012;103(Suppl. 2):S17–S22. doi: 10.1007/BF03403824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papatheodoridis G, et al. Clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Journal of Hepatology. 2012;57(1):167–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H-A, et al. Digital epidemiology: use of digital data collected for non-epidemiological purposes in epidemiological studies. Healthcare Informatics Research. 2018;24(4):253–262. doi: 10.4258/hir.2018.24.4.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PHO (2019) Public Health Ontario (PHO) laboratories keep Ontarians safe and healthy. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/Pages/default.aspx (January 29, 2019).

- Pottie K, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E1–E102. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada (2014) Report on hepatitis B and C in Canada: 2014. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/health/publications/diseases-conditions/report-hepatitis-b-c-canada-2014.html#fn1. Accessed January 2020.

- Raffetti, E., Fattovich, G., & Donato, F. (2016). Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in untreated subjects with chronic hepatitis B: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Liver International : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver, 36(9), 1239–1251. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Reitmanova S, Gustafson DL, Ahmed R. ‘ Immigrants can be deadly ’: critical discourse analysis of racialization of immigrant health in the Canadian press and public health policies. Canadian Journal of Communication. 2015;40:471–487. doi: 10.22230/cjc.2015v40n3a2831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, C., Shrier, I., Marshall, L., Cnossen, S., Schwartzman, K., Klein, M. B., Schwarzer, G., Greenaway, C. (2012). Seroprevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection and prior immunity in immigrants and refugees: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 7(9), e44611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shah H, et al. The management of chronic hepatitis C: 2018 guideline update from the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver. CMAJ. 2018;190(22):677–687. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Carballo M, Feld JJ, Janssen HLA. Immigration and viral hepatitis. Journal of Hepatology. 2015;63(2):515–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman ML. The next wave of hepatitis C virus: the epidemic of intravenous drug use. Liver International. 2018;38:34–39. doi: 10.1111/liv.13647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinkels H, Pottie K, Tugwell P, Rashid M. Development of guidelines for recently arrived immigrants and refugees to Canada: Delphi consensus on selecting preventable and treatable conditions. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E928–E932. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ti, L., et al. (2017). Hepatitis C testing in Canada: don’t leave baby boomers behind. CMAJ, 189(25), E870–E871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Van Walraven C, Austin P. Administrative database research has unique characteristics that can risk biased results. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2012;65(2):126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC 237 kb)