Abstract

Background

Flying Phobia (FP) is a prevalent disorder that can cause serious interference in a person's life. ICBT interventions have already shown their efficacy in several studies, but studies in the field of specific phobias are still scarce. Moreover, few studies have investigated the feasibility of using different types of images in exposure scenarios in ICBTs and no studies have been carried out on the role of sense of presence and reality judgement. The aim of the present study is to explore the feasibility of an ICBT for FP (NO-FEAR Airlines) using two types of images with different levels of immersion (still and navigable images). A secondary aim is to explore the potential effectiveness of the two experimental conditions using two types of images compared to a waiting list control group. Finally, the role of navigable images compared to the still images in the level of anxiety, sense of presence, and reality judgement will also be explored. This paper presents the study protocol.

Methods

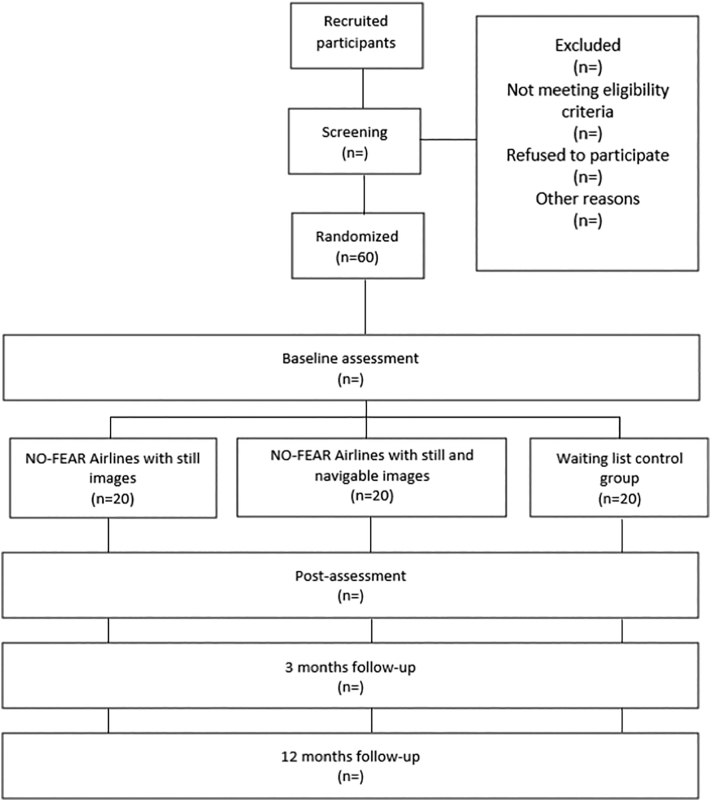

This study is a three-armed feasibility pilot study with the following conditions: NO-FEAR Airlines with navigable images, NO-FEAR Airlines with still images, and a waiting list group. A minimum of 60 participants will be recruited. The intervention will have a maximum duration of 6 weeks. Measurements will be taken at four different moments: baseline, post-intervention, and two follow-ups (3- and 12-month). Participants' opinions, preference, satisfaction and acceptance regarding the images used in the exposure scenarios will be assessed. FP symptomatology outcomes will also be considered for secondary analyses. The anxiety, sense of presence, and reality judgement in the exposure scenarios will also be analysed.

Discussion

This study will conduct a pilot study on the feasibility of an ICBT for FP and it is the first one to explore the evaluation of patients of the two type of images (still and navigable) and the role of presence and reality judgement in exposure scenarios delivered through the Internet. Research in this field can have an impact on the way these scenarios are designed and developed, as well as helping to explore whether they have any effect on adherence.

Trial registration

NCT03900559. Trial Registration date 3 April 2019, retrospectively registered.

Keywords: Flying Phobia, Internet-based intervention, Exposure therapy, Treatment preferences, Sense of presence, Reality judgement

Highlights

-

•

Interventions including exposure scenarios delivered through the Internet are limited.

-

•

This study is a pilot study about the feasibility of an ICBT for Flying Phobia.

-

•

Participants’ opinion and preferences of navigable exposure images delivered through the Internet are explored.

-

•

This study also explores the potential effectiveness of different degrees of immersion of the exposure images.

-

•

Presence and Reality Judgement have not been studied in ICBTs.

1. Introduction

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), Flying Phobia (FP) is considered a situational specific phobia. The person suffering from this problem might take medication or alcohol in order to cope with the emotional distress (Foreman et al., 2006), or avoid flying in general. FP can cause serious interference in daily life, social functioning, relationships, and the professional field (Busscher et al., 2013; Oakes and Bor, 2010). In terms of its prevalence, up to 13% of the general adult population report fear related to the flying situation, and around 2–5% of the population could meet the criteria for specific phobia (Eaton et al., 2018). Compared to other specific phobias, FP presents the highest rates of treatment-seeking (Wardenaar et al., 2017), which makes it clear that there is a need for well-established evidence-based treatments for this problem.

Research establishes that in vivo exposure is the most effective intervention for specific phobias (Choy et al., 2007; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2008). However, in the case of FP, it can be difficult and expensive to access the phobic situation but the incorporation of Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) has helped with this matter. Furthermore, VRET seems to be more accepted by patients than traditional exposure (Garcia-Palacios et al., 2007), and it has shown its efficacy for treating specific phobias (including FP) in several studies (Botella et al., 2017; Parsons and Rizzo, 2008) and results seem to be comparable to the ones found in in vivo exposure (Wechsler et al., 2019). However, VRET is an expensive tool that still does not reach the majority of the people in need of help. In this line, a more affordable way of delivering exposure treatment can be exposure through images related to the phobic object, in which the patient views photographs of the phobic stimuli in order to overcome the feared situation. This method of exposure therapy has already proved its efficacy in FP in a previous study (Tortella-Feliu et al., 2011) showing no significant differences compared to VRET.

It has been established that there is a clear need for new ways to deliver psychological interventions, and the Internet and self-help treatments might play a fundamental role in this endeavour (Kazdin and Blase, 2011). In recent years, the efficacy and acceptability of Internet-based Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (ICBTs) for anxiety disorders has been demonstrated in several studies (Andersson, 2016; Andrews et al., 2018; Andrews et al., 2010; Cuijpers, 2003; Olthuis Janine et al., 2015). However, in the particular case of specific phobias, the research in the field of ICBTs has been scarce. Some non-randomized controlled studies with specific phobias have been conducted, like a series of case studies in adults with small animal phobia (Botella et al., 2008), an open trial in children and adolescents with dental anxiety (Shahnavaz et al., 2018), and a pilot study in children with specific phobias whose parents helped with the intervention (Vigerland et al., 2013). Other controlled studies have included specific phobias along with other disorders in their ICBTs. This is the case of a transdiagnostic intervention for people with panic and phobias (Schröder et al., 2017), a study conducted in a sample of outpatients with specific phobia, agoraphobia, or social phobia (Kok et al., 2014), or the self-help program used in the context of mental health services in panic and phobias (Schneider et al., 2005). Regarding studies focused only on specific phobias, two Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT) were conducted in Sweden for animal phobia (Andersson et al., 2009, Andersson et al., 2013). In them, in vivo exposure was compared to a self-help ICBT with text modules and videos with guidelines to carry out the exposure therapy in their daily lives.

In the case of FP, to our knowledge, there is only one ICBT for this problem (NO-FEAR Airlines), and it was developed by our research group. This is a self-help program delivered through the Internet that has already shown its efficacy in a recent RCT comparing the online intervention with or without therapist support to a waiting list control group (Campos et al., 2019). However, in this study, the role of the degree of immersion of the images used for the exposure tasks in the program was not explored.

Sense of presence, described as the sense of being in a virtual environment (Steuer, 1992), has been widely studied in the context of VRET (Baños et al., 2000; Diemer et al., 2015; Krijn et al., 2004; Ling et al., 2014; Price and Anderson, 2007; Riva et al., 2007; Robillard et al., 2003). Although the first research findings in this field were contradictory, the literature indicates that emotions and presence are associated. Results show that when a VRET scenario engages emotions, the sense of presence immediately increases. Furthermore, this relationship appears to be bidirectional (Riva et al., 2007), which means that emotions increase the sense of presence, and presence is also a significant predictor of the emotional responses in virtual environments. The relationship between fear and presence has been recently studied (Gromer et al., 2019), confirming this bidirectional relationship and concluding that although presence did not have a direct causal relationship with fear, interpersonal variability of users in presence was linked to it and predicted later fear responses. In terms of treatment efficacy, research has also suggested that, although presence is linked to the anxiety experienced during the exposure, there is no direct relationship between sense of presence and treatment outcomes (Price et al., 2011; Price and Anderson, 2007; Tardif et al., 2019).

The immersion level of the technology is not the only variable that explains the subjective sense of presence, but it does play a role in this relationship. Immersive technology can reduce the “noise” of other individual or real-world factors in an exposure scenario, and, therefore, it can increase the presence and anxiety experienced in these virtual environments (Ling et al., 2014). In this line, it has been suggested that 360° panoramas could be useful because they can evoke more similar psychological responses (in terms of cognitive and emotional factors) to the ones experienced in the real physical environment that they recreate, and in comparison to still images (Higuera-Trujillo et al., 2017).

Reality judgement is another important construct to consider in virtual stimuli. Reality judgement is defined as the extent to which the experience is acknowledged as real, not in terms of the realism of the virtual world, but in terms of the willingness to interpret the whole virtual experience as veridical (Baños et al., 2000). Research on this construct has been scarce so far.

As mentioned above, the previous study using NO-FEAR Airlines was composed exclusively of still images. The aim of the present study is to conduct a feasibility pilot study with NO-FEAR Airlines ICBT (Campos et al., 2016) using two types of images in the exposure scenarios (still images vs 360° navigable images) in order to explore the feasibility and evaluation of the patients of the two active treatments arms. Participants' opinions, satisfaction, preference and acceptance of the different images will be assessed. A secondary aim is to explore the potential effectiveness of the two active treatment arms compared to a waiting list control group. Finally, we will explore the role of navigable images compared to the still images in the level of anxiety, sense of presence, and reality judgement in the exposure scenarios and whether the aforementioned variables mediate in treatment efficacy. If a mediation effect is found, we will also analyse the potential effectiveness of the navigable images versus the still images. Regarding the main aim of this study, we hypothesize that both treatment conditions will be well accepted by the participants, but participants will prefer 360° images over still images.

2. Methods/design

2.1. Study design

In this investigation we will carry out a pilot study on the feasibility of an ICBT intervention for FP using two types of images. Participants will be randomly allocated to one of three conditions: NO-FEAR Airlines with navigable images, NO-FEAR Airlines with still images, and a Waiting List (WL) Control Group. For ethical reasons, participants in the WL group will be offered treatment when they complete the post-waiting list assessment after a period of 6 weeks, which is the maximum period of time that participants in the experimental condition will have to complete the program. Assessments will be conducted at pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 3- and 12-month follow-ups. An online informed consent form will be signed by participants before randomization.

The trial has been registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT03900559 and will be conducted following the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement for pilot and feasibility studies (Eldridge et al., 2016), the CONSORT-EHEALTH guidelines (Eysenbach, 2011) and the SPIRIT guidelines (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials)(Chan et al., 2013). Fig. 1 shows the study flowchart.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of participants.

2.2. Participants, recruitment, and eligibility criteria

Participants in this trial will be community sample adult patients who meet DSM-5 criteria for FP and volunteer to engage in the study via email, by making contact through the research website (http://fobiavolar.labpsitec.es) or by calling the emotional disorders university clinic. To reach more potential participants, the study will be announced on local media, social networks, and on the university website. Information brochures will also be placed at nearby universities and towns. Participants from any part of the world can benefit from the intervention, as long as they understand Spanish.

The clinical team involved in the study (composed of trained psychologists) will explain the study conditions and clarify any doubts the participant may have. The team will arrange a telephone interview with people interested in receiving the treatment. In the interview, they will assess the participant's symptomatology and ensure that the patient fulfils the study inclusion criteria. This call will last approximately 30–45 min.

Participants must meet the following inclusion criteria to be included in the present study: (1) be at least 18 years old; (2) meet diagnostic criteria for FP; (3) be able to use a computer and have Internet connection; (4) have an e-mail address; and (5) be able to understand and read Spanish. On the other hand, exclusion criteria for the study will be as follows: (1) currently receiving psychological treatment for FP; (2) meeting the criteria for another severe mental disorder: abuse/dependence of alcohol or other substances, psychotic disorder, dementia, bipolar disorder; (3) severe personality disorder; (4) presence of depressive symptomatology, suicidal ideation or plan; (5) presence of heart disease; (6) pregnant women (from the fourth month).

The clinical team will discuss the inclusion or exclusion of each participant assessed in the study to ensure a more reliable diagnosis. If the team decides that the participant meets the FP diagnosis, the participant will be randomly allocated to one of the study conditions after signing the informed consent form.

2.3. Randomization and blinding

Participants will have to agree to participate in the study without knowing to which condition they will be allocated. The randomization will be conducted by an independent researcher who will be unaware of the characteristics and will not be involved in the study. This independent researcher will not have information about the participants, apart from the ID code number assigned to each of them to protect their confidentiality. Participants will be allocated to one of the three conditions using a computer-generated random number sequence originated with https://www.randomizer.org/ in a 1:1:1 ratio. Study researchers will also be blind to the condition to which the participants are allocated. Randomization will be conducted in the order of the participants' signing of the informed consent form. Participants will know the condition in which they are allocated after signing consent form and randomization, and they will be given a brief explanation of the characteristics of their condition before beginning the treatment or waiting period.

2.4. Sample size

Considering the main aim of this feasibility study, the sample size was based on practical considerations and our previous study (Campos et al., 2016) including participants seeking help for FP at our emotional disorders university clinic. The expected dropout rate in internet-based internet interventions has also been considered (around 20%; Carlbring et al., 2018). Therefore, the number of participants needed to reasonably evaluate feasibility goals is 60 (20 participants per condition). In addition, this sample size coincides with the recommendation proposed by Viechtbauer et al. (2015).

2.5. Ethics

This study will follow the international standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice. The study will also be carried out following Spanish and European Union guidelines and legislation on data protection and privacy. The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Universitat Jaume I (Castellón, Spain) (7/2017). Participation will be completely voluntary, and participants will be able to leave the study at any time. Participants in the WL condition will also have the opportunity to access the intervention program once the waiting period ends. All the participants will have to sign an informed consent form before randomization. Each participant will have a unique username and password to access the Internet platform, and data from their outcome measures will be secured via the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES-256). Each participant will also be assigned an ID code for the project. Participants' personal data will be stored separately from other data, and they will only be available to the researcher responsible for their supervision.

2.6. Interventions

NO-FEAR Airlines is an ICBT for the treatment of FP hosted on a web platform (http://fobiavolar.labpsitec.es). The program has six different scenarios related to the flying process, with real images and sounds so that the patient can carry out the exposure. The intervention has three main components: psychoeducation, exposure, and overlearning.

In the psychoeducation component, the FP symptomatology and characteristics are explained, as well as some other information that can help the participants to understand their problem.

The exposure component is the main component of this intervention. This component consists of videos where different images are presented to the patient. The six exposure scenarios included in the program are:

Flight preparation: Images about the preparation process for taking a flight such as pictures of preparing clothes, packing everything in the suitcase, the plane ticket, and getting ready to leave for the airport are presented.

Airport: Images of the check in process at the airport are presented in this scenario.

Boarding and take off: Images of the different stages of the boarding and taking off process are displayed, such as the flight attendant helping everyone sitting down, the safety instructions or the view from the window.

Flight: Images of the flying process (understood as the time where the plane is in the air) are presented.

Landing: Pictures of the plane preparing to land, and different stages of the landing process are presented.

News related to plane accidents: Different reports about plane accidents are presented. It is important to note that not all of the news showed here are bad news. For example, there are reports about difficulties experienced by planes where the flying crew was able to handle the situation and passengers were safe. Although the rest of scenarios can vary in the order they appear, this scenario is always the last one to be presented.

The order of appearance of the exposure scenarios will change depending on the participant. Before starting the intervention, the program assesses the level of anxiety of the different flight situations and arranges the exposure scenarios that will be shown later in the intervention so that the patient can start with the scenario that has the lowest level of anxiety and end with the scenario that causes the highest level of anxiety, thus building a personalised exposure hierarchy. The exposure scenarios are composed of cycles; one cycle consists of 3 min of images and sounds, and each exposure scenario contains a maximum of twenty cycles. After each cycle in each scenario, the program asks the patient about the level of anxiety experienced during the situation. If the anxiety is moderate or high (3 or more on a scale from 0 to 10), the program will show the same cycle of that scenario again until the anxiety level decreases. The participant can take a break from the exposure scenarios after a cycle finishes, but the next scenario in the hierarchy will not be shown until the anxiety level decreases (under 3). Participants will be given the recommendation to do two exposure scenarios per week, but they will be reminded that, because this is a self-applied program, they are free to advance at their own pace. Also, before each exposure scenario, participants will be given the instruction to imagine that the situation that they are going to face is real.

After all six exposure scenarios are completed, the program gives the participant the option to do an “overlearning” module where they can choose to repeat any of the exposure scenarios or even add more difficult conditions (for example, bad weather conditions or turbulences). For a more detailed description of the program, see Campos et al. (2016).

Participants will have a maximum period of 6 weeks to complete the Internet program, but because this is a self-applied treatment, they can finish it sooner. Therapist support will not be provided in this study, based on previous results showing no differences in treatment efficacy with or without therapist support (Campos et al., 2019). However, participants in the two treatment conditions will receive emails every two weeks reminding them to log into the program to ensure adherence, and they will be able to contact the therapist via mail if they have any problems or questions about the program.

In this study, the exposure scenarios will be implemented in two formats:

-

1)

NO-FEAR Airlines with still images

In this condition, the images shown in the exposure scenarios will be a succession of different still pictures related to the scenario on display, along with sounds, depending on the situation. The images will be shown for a full cycle (3 min), and then the patient will have to report the maximum level of anxiety they experienced during the exposure. In one cycle, 25 photographs will be shown to the patient, each one appearing on screen for around 7 s. The participant has no control over these images.

-

2)

NO-FEAR Airlines with still and navigable images

In this condition, two out of the six exposure scenarios will present “navigable” images, that is, 360° panoramic images. The two exposure scenarios where these images will be displayed are the airport scenario and the flight scenario. Navigable images allow the participant to look at the surroundings of the scenario in all directions (up, down, right, and left), broadening the field of view. The participant will be in control of rotating the image with the keyboard or the mouse, choosing the pace and direction for looking around the scene. Only one image will be shown for the full cycle (3 min), and the patient can look around while hearing sounds related to the exposure scenario, thus, having control of what is appearing on the screen. The sounds in the two conditions will be the same.

For more details about the intervention program, see Campos et al., 2016, Campos et al., 2018, Campos et al., 2019. A sample of the flight exposure scenario in both still and navigable images conditions is available online: (http://repositori.uji.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10234/189216/Navegables%20avio%CC%81n.mp4?sequence=2&isAllowed=y).

2.7. Waiting list control group

Participants in this group will be assessed before and after the six-week waiting period. After completing a post-waiting period assessment, they will be offered NO-FEAR Airlines treatment in the navigable images condition.

2.8. Assessment

The participants will be assessed at four different times during the study: baseline, post-treatment, and 3- and 12-month follow-ups. The diagnostic interview will be administered by a trained clinician via phone, and self-report questionnaires will be administered online on the program web page or, in the case of the WL group, via SurveyMonkey (https://es.surveymonkey.com/). All assessment instruments and periods in this study can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study measures and assessment times.

| Pre-treatment | Time of assessment | Source of assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic data | BL | Phone call |

| ADIS-IV | BL, Post-T, FU | Phone call |

| Preferences Scale | BL, Post-T, FU | Phone call |

| Treatment's opinion | Post-T | Phone call |

| Qualitative interview | Post-T | Phone call |

| FFQ-II | BL, Post-T, FU | NO-FEAR Airlines/SurveyMonkey |

| FFS | BL, Post-T, FU | Phone call |

| Fear and Avoidance Scales | BL, Post-T, FU | Phone call |

| Clinician Severity Scale | BL, Post-T, FU | Phone call |

| Expectations Scale/Satisfaction Scale | BL, Post-T, FU | Phone call |

| FP particularities | BL, Post-T, FU | NO-FEAR Airlines |

| Anxiety during exposure | During exposure scenarios | NO-FEAR Airlines |

| Sense of presence and reality judgement | After exposure scenarios | NO-FEAR Airlines |

| Exposure cycles | After exposure scenarios | NO-FEAR Airlines |

| Patient's Improvement Scale | Post-T, FU | Phone call |

| RJPQ | Post-T | NO-FEAR Airlines |

ADIS-IV: Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule; FFQ-II: Fear of Flying Questionnaire; FFS: Fear of Flying Scale; FP: Flying Phobia; RJPQ: Reality Judgement and Presence Questionnaire.

2.8.1. Diagnostic Interview and participants' characteristics

2.8.1.1. Sociodemographic variables

The gender, age, marital status, work status, and educational level of each participant will be registered.

2.8.1.2. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS-IV; Brown et al., 1994))

This interview will be administered via phone to diagnose FP and check the fulfilment of the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The same interview will be administered at pre-, post-treatment and follow-ups. DSM-5 criteria will also be considered. This semi-structured interview will help with the differential diagnosis of other phobias or anxiety-related disorders because it has shown adequate psychometric properties and good to excellent reliability for the majority of the anxiety disorders (Antony et al., 2001).

2.8.2. Primary outcome measures of feasibility

2.8.2.1. Participant adherence (i.e., attrition and dropout percentages) will be assessed in the two iCBT groups

Moreover, the number of exposure scenarios completed will be counted.

2.8.2.2. Expectations Scale and Satisfaction Scale (adapted from Borkovec and Nau, 1972)

This self-report inventory measures the patients' expectations before they start the treatment and after they receive a brief explanation about the intervention and their experimental condition. The same questions have to be answered when the patient completes the treatment in order to assess satisfaction. The 6 items are rated from 1 (“Not at all”) to 10 (“Highly”), and they provide information about the extent to which: 1) the treatment is perceived as logical; 2) patients are satisfied with the treatment; 3) they would recommend the treatment to a friend with the same problem; 4) the treatment would be useful to treat other psychological problems; 5) patients perceive the treatment as useful for their particular problem; and 6) the treatment is perceived as aversive.

2.8.2.3. Preferences questionnaire

This questionnaire collects the patient's preferences regarding the two types of images included in this study (navigable and still images) through 5 dichotomous questions where they have to choose one of the two conditions. The questions are: (1) Preference (“If you could choose between the two images, which one would you choose?”); (2) Subjective effectiveness (“Which of these two images do you think would be more effective in helping you to overcome your problem?”); (3) Logic (“Which of these two images do you think would be more logical to help you overcome your problem”); (4) Subjective aversion (“Which of these two images do you think would be more aversive?”); and (5) Recommendation (“Which of these two images would you recommend to a friend with the same problem?”). Participants will answer these questions before the treatment and before knowing the condition to which they are allocated (after the characteristics of each type of image are explained) and after they have completed the treatment (and after seeing a short video showing the image condition they did not receive).

2.8.2.4. Qualitative interview

This interview assesses the participant's opinion of the intervention program after finishing it. The interview contains 13 items that the patient has to rate on a scale ranging from 1 (“very little”) to 5 (“very much”) and explain the reasons for their rating on each question. There are also two open questions where the participants have to give their overall opinion about the intervention program and the program images. In this interview, the perceived sense of presence and reality judgement in each scenario will also be assessed.

2.8.3. FP symptomatology outcomes

2.8.3.1. Fear of Flying Questionnaire (FFQ-II; Bornas et al., 1999)

The FFQ is a 30-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the anxiety the person feels in different situations of the flight process: anxiety during the flight, anxiety experienced getting on the plane, and anxiety experienced due to the observation of neutral or unpleasant flying-related situations. For each item, respondents rate their degree of discomfort associated with the situation on a scale from 1 to 9 (1 = not at all, 9 = very much). Scores range from 30 to 270. Internal consistency was α = 0.97, and test-retest reliability (15-day retest period) was r = 0.92 (Bornas et al., 1999).

2.8.3.2. Fear of Flying Scale (FFS; Haug et al., 1987)

The FFS is a 21-item self-report measure to assess fear in different flying situations. Fear elicited by each situation was rated on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all, 4 = very much), with scores ranging from 21 to 84. The original FFS reported a Cronbach's alpha of 0.94 and retest reliability (after a three-month period) of 0.86 (Haug et al., 1987).

2.8.3.3. Measures related to FP recorded by the system

The program assesses information related to the history of the problem, such as the duration, safety behaviours, the number of times the patient has taken a flight, or if they have ever had any negative experiences with flying.

2.8.3.4. Fear and Avoidance Scales (adapted from Marks and Mathews, 1979)

Fear and avoidance of the flight situation will be measured on a scale ranging from 0 (“No fear at all,” “I never avoid it”) to 10 (“Severe fear,” “I always avoid it”). The degree of belief in catastrophic thoughts is also assessed on a scale from 0 to 10. This scale has shown good reliability and sensitivity to change (Marks and Mathews, 1979).

2.8.3.5. The Clinician Severity Scale (adapted from Di Nardo et al., 1994)

The clinician rates the severity of the patient's symptomatology on a scale from 0 to 8, where 0 is symptom-free and 8 is extremely severe.

2.8.3.6. Patient's Improvement Scale (adapted from the Clinical Global Impression scale, CGI; Guy, 1976)

One item on the CGI scale was adapted in order to assess the participant's degree of improvement (compared to baseline) on a 7-point scale (1 “much worse” to 7 “much better”). This scale is answered by the patient.

2.8.4. Sense of presence and reality judgement measures

2.8.4.1. Sense of presence and reality judgement

When the exposure scenario is completed (anxiety level less than 3), the program will assess, on scales from 0 to 10, the extent to which the patients feel present in the situation and the extent to which they feel the situation is real.

2.8.4.2. Reality Judgement and Presence Questionnaire (RJPQ) (adapted from Baños et al., 2005)

The original questionnaire showed a three-factor solution, and in this adapted version of 18 items, the questions assessing reality judgement and sense will be administered. A 0–10 Likert scale is used to respond to all items.

2.8.5. Other measures recorded by the system

2.8.5.1. Anxiety level after the scenario

After each exposure cycle, the program will ask the patient to rate the maximum level of anxiety experienced during the exposure situation on a scale ranging from 0 (“no anxiety”) to 10 (“maximum level of anxiety”). If the anxiety level is not less than 3, another cycle of the same scenario will be repeated until the anxiety level is low enough.

2.8.5.2. Cycles in each exposure scenario

The program will record the number of cycles each participant performs in each exposure scenario. Each cycle is 3 min long.

2.9. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics will be conducted in order to examine participants' satisfaction, preferences, opinion and acceptance in both experimental conditions. Drop-out rates and attrition will also be calculated.

Analyses of the sociodemographic and baseline measures will be conducted to verify that there are no significant differences between the groups. For this purpose, one-way ANOVAs for continuous data and chi-square tests for categorical variables will be used.

Mixed-model analysis will be conducted to test the potential effectiveness of the intervention for the FP symptomatology outcomes measures at post-treatment and the 3- and 12-month follow-ups in order to handle missing data (Salim et al., 2008). The results will be reported following CONSORT recommendations and SPIRIT guidelines (Chan et al., 2013; Eysenbach, 2011). Effect sizes will be calculated using Cohen's d to assess between- and within-group changes. Chi-square tests will also be calculated to assess group differences in behavioural outcomes (number of flights taken after treatment and safety behaviours) at post-treatment and follow-ups.

Furthermore, Bootstrap regression analysis will be carried out using PROCESS approach (https://afhayes.com/) (Preacher and Hayes, 2004), in order to explore the relationship between the group condition and the FP symptomatology outcome measures, considering the sense of presence and reality judgement at post-treatment as the proposed mediator. In addition, separate mediation and moderation analyses will be conducted to explore the association between the experimental condition and the sense of presence and reality judgement assessed at post-treatment, and test whether the questions on sense of presence and reality judgement assessed after each exposure scenario would be significant mediators/moderators in this relationship.

Statistical analyses will be conducted with the IBM SPSS version 26.0 and with process PROGRAM.

3. Discussion

FP is a prevalent disorder, but people suffering from it do not always seek help due to rejection of in vivo exposure. Based on the guidelines to find new ways to deliver psychological treatments, NO-FEAR Airlines can be a useful tool. The program has already demonstrated its efficacy in reducing phobic symptoms in a previous study, and there are data showing that it is a well-accepted program (Campos et al., 2018). However, more of the program variables can be explored and improved. This study protocol describes a pilot study on the feasibility of an ICBT for FP, but using two types of images with different degrees of immersion in order to explore feasibility and patients' satisfaction, acceptance and opinion and evaluate if a change in the exposure images used in the program will be feasible in a future RCT. Secondary goals are to explore the potential effectiveness of both treatment conditions compared to a WL control group, and the role of sense of presence and reality judgement in the exposure scenarios and their possible relationship with FP symptomatology outcomes.

The acceptability data of the previous study (Campos et al., 2018) showed that participants rated still images as less useful than psychoeducation and overlearning, and referred that they would prefer 360° images or short videos with movement. As still images have already shown its efficacy in NO-FEAR Airlines (Campos et al., 2019), we want to explore the participants' opinion and preferences about navigable images before changing them all. This is the reason why only two of the six scenarios are navigable in one of the conditions.

To our knowledge, there are no previous studies on the role of 360° images versus still images, or presence and reality judgement, in exposure scenarios delivered through the Internet, and their impact on anxiety. As mentioned before, still images have already shown their efficacy (Campos et al., 2019), but whether the sense of presence and reality judgement increase with a wider field of view and mediate in the treatment outcome remains unexplored. There is evidence of the efficacy of online image-based exposure therapy (Matthews et al., 2015), but the level of immersion needed in these images has yet to be explored in these interventions. In the case of VRET, there is a positive correlation between immersive technology and presence and anxiety (Ling et al., 2014), but research with participants with clinical symptoms also suggests that, although some level of presence is needed, higher levels of immersion do not lead to higher levels of anxiety than medium levels of immersion (Kwon et al., 2013). There is also evidence that visual realism is not an important factor in presence (Gromer et al., 2019), but a wide field of view is (Zikic, 2007). Whether a similar process occurs in online exposure is still unknown.

This study has some strengths: as mentioned above, this is the first study to explore the feasibility, acceptance and satisfaction with different type of images used in an ICBT for FP, and continues to be one of the few interventions where the exposure technique is directly delivered through the Internet. Additionally, this is also the first study to analyse the role of presence and reality judgement in an ICBT and explore the role of 360-degree images in exposure scenarios delivered through the Internet. In this line, the literature on reality judgement is still scarce, even in VRET, and so this study will contribute to the knowledge in this field as well. The program is based on two previous studies in the field of computer-based interventions that have already demonstrated their efficacy (Campos et al., 2019; Tortella-Feliu et al., 2008). This study aims to keep improving the intervention offered to people suffering from FP in order to increase their satisfaction with the program.

Some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. In this study, telephone support will not be used, based on the results related to weekly support in the previous study using NO-FEAR Airlines, where therapist support did not show better treatment efficacy than the totally self-applied condition. However, encouraging messages will be sent to participants by email every two weeks. Second, not all the exposure scenarios in the navigable image condition will be 360° photographs. However, this means that participants in this condition will see both types of images, which will help to explore their preferences. Third, FP presents high comorbidity with other phobic and anxiety disorders, and this can interfere with the outcome measures. Lastly, COVID-19 may impact in the results of this study as flights have been restricted in some countries. This will be taken into consideration on the patients' assessments and, if they have not flied, they will be asked whether the reason has to do with flight restrictions due to COVID-19 or to any other reason derived from the pandemic.

4. Conclusion

Despite its limitations, this study is the first one to explore the use of 360° images in a treatment for FP delivered through the Internet. If this type of images is found to be useful, this study will contribute to the way ICBT programs are designed and developed, and, specifically, it will help with the way exposure scenarios are delivered in ICBTs. As a secondary aim, it will also contribute to explore the potential effectiveness of an image-based exposure therapy through the Internet using two types of images, and to the knowledge about the role of sense of presence and reality judgement in an ICBT. The use of more immersive images might help to enhance adherence to the program. This study will also add more evidence about the use of self-applied ICBTs that employ the exposure technique for specific phobias in a field where studies have been scarce.

Abbreviations

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (Programa Estatal I + D + i. RTI2018-100993-B-100), Personal Technologies for Affective Health (AffecTech. H2020-MSCA-ITN-2016 722022), Excellence Research Program PROMETEO ("INTERSABIAS" project-PROMETEO/2018/110/Conselleria d'Educació, Investigació, Cultura i Esport, Generalitat Valenciana), CIBEROBN, an initiative of the ISCIII (ISC III CB06 03/0052), and Plan 2018 de Promoción de la Investigación de la Universitat Jaume I (UJI-2018-57).

Funding

This research is supported by Generalitat Valenciana through a pre-doctoral grant (VALi + d) (ACIF/2017/191) provided to one of the authors. The funding body did not play any role in the design of the study, nor will it play any role in data collection, analysis, interpretation of data or the writing of manuscripts.

Contributor Information

Sonia Mor, Email: smor@uji.es.

Cristina Botella, Email: botella@uji.es.

Daniel Campos, Email: camposdcb@gmail.com.

Cintia Tur, Email: ctur@uji.es.

Diana Castilla, Email: diana.castilla@uv.es.

Carla Soler, Email: carla.soler@hotmail.com.

Soledad Quero, Email: squero@uji.es.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Author; Washington, DC: 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G. Internet-delivered psychological treatments. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2016;12(1):157–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Waara J., Jonsson U., Malmaeus F., Carlbring P., Öst L.G. Internet-based self-help versus one-session exposure in the treatment of spider phobia: a randomized controlled trial. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2009;38(2):114–120. doi: 10.1080/16506070902931326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Waara J., Jonsson U., Malmaeus F., Carlbring P., Öst L.G. Internet-based exposure treatment versus one-session exposure treatment of snake phobia: a randomized controlled trial. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2013;42(4):284–291. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2013.844202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews Gavin, Cuijpers P., Craske M.G., McEvoy P., Titov N. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2010;5(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G., Basu A., Cuijpers P., Craske M.G., McEvoy P., English C.L., Newby J.M. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: an updated meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disorders. 2018;55:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony M.M., Orsillo S.M., Roemer L., editors. Practitioner’s Guide to Empirically Based Measures of Anxiety. Springer Science & Business Media; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baños R.M., Botella C., Garcia-Palacios A., Villa H., Perpiña C., Alcañiz M. Presence and reality judgment in virtual environments: a unitary construct? CyberPsychol. Behav. 2000;3(3):327–335. doi: 10.1089/10949310050078760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baños R., Quero S., Salvador S., Botella C. The role of presence and reality judgement in virtual environments in clinical psychology. Cyberpsych. Behav. 2005;8(4):303–304. [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec T.D., Nau S.D. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 1972;3(4):257–260. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(72)90045-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bornas X., Tortella-Feliu M., De la Banda G. Factor validity of the fear of flying questionnaire. Anal. Modification Conducta. 1999;25:885–907. [Google Scholar]

- Botella C., Quero S., Banos R.M., Garcia-Palacios A., Breton-Lopez J., Alcaniz M., Fabregat S. Telepsychology and self-help: the treatment of phobias using the internet. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2008;11(6):659–664. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botella C., Fernández-Álvarez J., Guillén V., García-Palacios A., Baños R. Recent progress in virtual reality exposure therapy for phobias: a systematic review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(7) doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0788-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T.A., Di Nardo P.A., Barlow D.H. Clinician’s Manual. Graywind Publications; 1994. Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM - IV (ADIS - IV) [Google Scholar]

- Busscher B., Spinhoven P., van Gerwen L.J., de Geus E.J.C. Anxiety sensitivity moderates the relationship of changes in physiological arousal with flight anxiety during in vivo exposure therapy. Behav. Res. Ther. 2013;51(2):98–105. doi: 10.1016/J.BRAT.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos D., Bretón-López J., Botella C., Mira A., Castilla D., Baños R., Tortella-Feliu M., Quero S. An internet-based treatment for flying phobia (NO-FEAR Airlines): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0996-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos D., Mira A., Bretón-López J., Castilla D., Botella C., Baños R.M., Quero S. The acceptability of an internet-based exposure treatment for flying phobia with and without therapist guidance: patients’ expectations, satisfaction, treatment preferences, and usability. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018;14:879–892. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S153041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos D., Bretón-López J., Botella C., Mira A., Castilla D., Mor S., Baños R., Quero S. Efficacy of an internet-based exposure treatment for flying phobia (NO-FEAR Airlines) with and without therapist guidance: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2060-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlbring P., Andersson G., Cuijpers P., Riper H., Hedman-Lagerlöf E. Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2018;47(1):1–18. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2017.1401115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A.-W., Tetzlaff J.M., Gotzsche P.C., Altman D.G., Mann H., Berlin J.A., Dickersin K., Hrobjartsson A., Schulz K.F., Parulekar W.R., Krleza-Jeric K., Laupacis A., Moher D. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346(jan08 15):e7586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy Y., Fyer A.J., Lipsitz J.D. Treatment of specific phobia in adults. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007;27(3):266–286. doi: 10.1016/J.CPR.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers Examining the effects of prevention programs on the incidence of new cases of mental disorders: the lack of statistical power. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2003;160(8):1385–1391. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo P., Brown T., Barlow D. Graywind Publications Inc; New York: 1994. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime Version (ADIS-IV-L) [Google Scholar]

- Diemer J., Alpers G.W., Peperkorn H.M., Shiban Y., Mühlberger A. The impact of perception and presence on emotional reactions: a review of research in virtual reality. Front. Psychol. 2015;6 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton W.W., Bienvenu O.J., Miloyan B. Specific phobias. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(8):678–686. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30169-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge S.M., Chan C.L., Campbell M.J., Bond C.M., Hopewell S., Thabane L., Lancaster G.A. 2016. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Extension to Randomised Pilot and Feasibility Trials. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G. CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of web-based and mobile health interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011;13(4) doi: 10.2196/jmir.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman E.I., Bor R., van Gerwen L. The nature, characteristics, impact and personal implications of fear of flying. In: Bor R., Hubbard T., editors. Aviation Mental Health: Psychological Implications for Air Transportation. Ashgate; Aldershot: 2006. pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Palacios A., Botella C., Hoffman H., Fabregat S. Comparing acceptance and refusal rates of virtual reality exposure vs. in vivo exposure by patients with specific phobias. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2007;10(5):722–724. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.9962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromer D., Reinke M., Christner I., Pauli P. Causal interactive links between presence and fear in virtual reality height exposure. Front. Psychol. 2019;10(JAN):141. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W.B. Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. 1976. Clinical global impression; pp. 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Haug T., Berntzen D., Götestam K.G., Brenne L., Johnsen B.H., Hugdahl K. A three-systems analysis of fear of flying: a comparison of a consonant vs a non-consonant treatment method. Behav. Res. Ther. 1987;25(3):187–194. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(87)90045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuera-Trujillo J.L., López-Tarruella Maldonado J., Llinares Millán C. Psychological and physiological human responses to simulated and real environments: a comparison between photographs, 360° panoramas, and virtual reality. Appl. Ergon. 2017;65:398–409. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin A.E., Blase S.L. Rebooting psychotherapy research and practice to reduce the burden of mental illness. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011;6(1):21–37. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok R.N., van Straten A., Beekman A.T.F., Cuijpers P. Short-term effectiveness of web-based guided self-help for phobic outpatients: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014;16(9) doi: 10.2196/jmir.3429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krijn M., Emmelkamp P.M., Biemond R., de Wilde de Ligny C., Schuemie M.J., van der Mast C.A.P. Treatment of acrophobia in virtual reality: the role of immersion and presence. Behav. Res. Ther. 2004;42(2):229–239. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon J.H., Powell J., Chalmers A. How level of realism influences anxiety in virtual reality environments for a job interview. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2013;71(10):978–987. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2013.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Y., Nefs H.T., Morina N., Heynderickx I., Brinkman W.-P. A meta-analysis on the relationship between self-reported presence and anxiety in virtual reality exposure therapy for anxiety disorders. PLoS One. 2014;9(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks I.M., Mathews A.M. Brief standard self-rating for phobic patients. Behav. Res. Ther. 1979;17(3):263–267. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90041-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews A., Naran N., Kirkby K.C. Symbolic online exposure for spider fear: habituation of fear, disgust and physiological arousal and predictors of symptom improvement. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes M., Bor R. The psychology of fear of flying (part I): a critical evaluation of current perspectives on the nature, prevalence and etiology of fear of flying. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2010;8(6):339–363. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olthuis Janine V., Watt Margo C., Bailey K., Hayden Jill A., Stewart Sherry H. Therapist-supported Internet cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons T.D., Rizzo A.A. Affective outcomes of virtual reality exposure therapy for anxiety and specific phobias: a meta-analysis. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 2008;39(3):250–261. doi: 10.1016/J.JBTEP.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K.J., Hayes A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M., Anderson P. The role of presence in virtual reality exposure therapy. J. Anxiety Disorders. 2007;21(5):742–751. doi: 10.1016/J.JANXDIS.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M., Mehta N., Tone E.B., Anderson P.L. Does engagement with exposure yield better outcomes? Components of presence as a predictor of treatment response for virtual reality exposure therapy for social phobia. J. Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25(6):763–770. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva G., Mantovani F., Capideville C.S., Preziosa A., Morganti F., Villani D., Gaggioli A., Botella C., Alcañiz M. Affective interactions using virtual reality: the link between presence and emotions. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2007;10(1):45–56. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robillard G., Bouchard S., Fournier T., Renaud P. Anxiety and presence during VR immersion: a comparative study of the reactions of phobic and non-phobic participants in therapeutic virtual environments derived from computer games. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2003;6(5):467–476. doi: 10.1089/109493103769710497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salim A., Mackinnon A., Christensen H., Griffiths K. Comparison of data analysis strategies for intent-to-treat analysis in pre-test–post-test designs with substantial dropout rates. Psychiatry Res. 2008;160(3):335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A.J., Mataix-Cols D., Marks I.M., Bachofen M. Internet-guided self-help with or without exposure therapy for phobic and panic disorders: a randomised controlled trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 2005;74(3):154–164. doi: 10.1159/000084000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder J., Jelinek L., Moritz S. A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic Internet intervention for individuals with panic and phobias – one size fits all. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 2017;54:17–24. doi: 10.1016/J.JBTEP.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahnavaz S., Hedman-Lagerlöf E., Hasselblad T., Reuterskiöld L., Kaldo V., Dahllöf G. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for children and adolescents with dental anxiety: open trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018;20(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.7803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steuer J. Defining virtual reality: characteristics determining telepresence. J. Commun. 1992;42(4):73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Tardif N., Therrien C.-É., Bouchard S. Re-examining psychological mechanisms underlying virtual reality-based exposure for spider phobia. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019;22(1):39–45. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2017.0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortella-Feliu M., Bornas X., Llabres J. Computer-assisted exposure treatment for flight phobia. Int. J. Behav. Consult. Ther. 2008;4(2):158–171. doi: 10.1037/h0100840. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tortella-Feliu M., Botella C., Llabrés J., Bretón-López J.M., del Amo A.R., Baños R.M., Gelabert J.M. Virtual reality versus computer-aided exposure treatments for fear of flying. Behav. Modif. 2011;35(1):3–30. doi: 10.1177/0145445510390801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viechtbauer W., Smits L., Kotz D., Budé L., Spigt M., Serroyen J., Crutzen R. A simple formula for the calculation of sample size in pilot studies. J. Clin. Epidem. 2015;68(11):1375–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigerland S., Thulin U., Ljótsson B., Svirsky L., Öst L.G., Lindefors N., Andersson G., Serlachius E. Internet-delivered CBT for children with specific phobia: a pilot study. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2013;42(4):303–314. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2013.844201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardenaar K.J., Lim C.C.W., Al-Hamzawi A.O., Alonso J., Andrade L.H., Benjet C., Bunting B., de Girolamo G., Demyttenaere K., Florescu S.E., Gureje O., Hisateru T., Hu C., Huang Y., Karam E., Kiejna A., Lepine J.P., Navarro-Mateu F., Oakley Browne M., de Jonge P. The cross-national epidemiology of specific phobia in the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol. Med. 2017;47(10):1744–1760. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler T.F., Mühlberger A., Kümpers F. Frontiers in Psychology. Vol. 10. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2019. Inferiority or even superiority of virtual reality exposure therapy in phobias? - a systematic review and quantitative meta-analysis on randomized controlled trials specifically comparing the efficacy of virtual reality exposure to gold standard in vivo exposure in agoraphobia, specific phobia and social phobia; p. 1758. Issue JULY. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitzky-Taylor K.B., Horowitz J.D., Powers M.B., Telch M.J. Psychological approaches in the treatment of specific phobias: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008;28(6):1021–1037. doi: 10.1016/J.CPR.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zikic N. Pennsylvania State University; 2007. Evaluating Relative Impact of VR Components Screen Size, Stereoscopy and Field of View on Spatial Comprehension and Presence in Architecture. (Doctoral dissertation) [Google Scholar]