Abstract

Background

Tobacco taxes, as with other ‘sin taxes’, are generally regarded as a highly cost-effective mechanism to reduce consumption but are often considered by policymakers to be regressive, undermining efforts to fully implement them at levels recommended by the WHO due to concerns of fairness. We aim to demonstrate whether there are circumstances in which the impacts of additional tobacco taxes are not regressive, using a standard income-share accounting definition of tax burden.

Methods and findings

We apply mathematical modelling and explore the hypothetical distributions in the net change in tobacco taxes and cigarette expenditures by income group, following an increase in tobacco taxation. The hypothetical distribution per income group of additional taxes and cigarette expenditures borne by individuals following tobacco tax hikes was calculated with respect to a selection of parameters including: the change in the retail price of cigarettes, the price elasticity of demand for tobacco, smoking prevalence, cigarette consumption and individual income. We determine the range of hypothetical parameter values for which increased tobacco taxation should not be considered to penalise the poorest income groups when examining marginal cigarette consumption expenditures and using an accounting definition of tax burden.

Conclusions

Our findings question the doctrine that tobacco taxes are uniformly regressive from a standard income-share accounting view and point to the importance of the specific features of tax policy to shape a progressive approach to tobacco taxation: tobacco tax increases are less likely to be regressive when accompanied by a broad framework of demand-side measures that enhance the capacity of low-income smokers to quit tobacco use.

Keywords: taxation, socioeconomic status, global health, disparities

Introduction

Globally, tobacco smoking is the largest single preventable cause of mortality for non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular diseases and cancer, and its death toll rose to an estimated 7 million premature deaths in 2017.1 As an illustration, China now counts more than 300 million adult smokers,2 resulting in an estimated 2 million premature deaths each year.1 The total number of smokers globally is estimated to be almost 1 billion persons and rising year on year in absolute terms.3

A comprehensive consensus array of evidence-informed tobacco control measures, including enforcement of smoke-free zones, advertising bans and taxation of tobacco products has been adopted with success in many global jurisdictions.4 Importantly, the World Health Organization’s (WHO)’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), now ratified by 181 countries, commits those countries to implement an array of tobacco control interventions summarised in specific articles of the FCTC through legislative or regulatory actions.5

Taxation of tobacco products is generally regarded as the single most cost-effective public health strategy for reducing smoking prevalence, through promotion of smoking cessation and prevention of smoking initiation.6–10 However, few countries have implemented taxation policies that meet the criteria outlined under the FCTC’s 2005 implementation platform, MPOWER,11 which calls for tax rates to constitute at least 75% of the final retail price.4 By 2008, about 20 countries had adopted the recommended taxation on tobacco products, yet in 2018, just 40 countries had adopted the FCTC standard.4 This situation underscores the deadly paradox that the most effective tobacco control policy is also the least widely implemented of the MPOWER recommendations.11 12

A major reason for the lack or delay in enforcement of large tax hikes on tobacco products is that often tobacco taxes are deemed to be inherently regressive.13 14 Qualifying taxes of regressive mean that they disproportionally hurt the poorest income groups: the traditional regressivity argument states that less affluent smokers incur proportionately greater expenditures on cigarettes compared with more affluent smokers; this is the accounting definition of tax burden,15 causing greater financial hardship to a population already impacted by problems of tobacco dependence and associated diseases.9 14 16 This view makes increasing tobacco taxation politically and morally less palatable than other measures. International agencies such as the WHO and the World Bank have nonetheless strongly supported tobacco taxation over the last three decades and pointed to the broader considerations of health benefits, mortality reduction, curbing out-of-pocket (OOP) health spending and reducing the economic burden of tobacco-related disease.17 18 However, some notable exceptions exist, including the International Monetary Fund, which had remained publicly agnostic on the question of tobacco taxes until recently. They have also now endorsed them.19

As Remler well documents,14 several definitions of tax burden can be employed to qualify tobacco taxes, including: comparing cigarette expenditures relative to income (the standard income-share accounting definition—the one we take in this paper); examining consumption changes and corresponding welfare-based willingness to pay of individuals; and considering welfare-based time-inconsistent preferences and ‘internalities’ of individuals (ie, smokers want to quit but cannot in the short term and want a commitment device (ie, higher taxes) forcing them to quit in the long term).20

Contesting the traditional view of tax regressivity, based on the sole examination of distributional cigarette consumption expenditures, a number of studies have examined broader outcomes of tobacco tax policy (including both financial and health measures, beyond simply the accounting burden of taxation) for individuals and households and have concluded that tobacco taxation can be ‘pro-poor’ in terms of its totality of effects.21–28 For example, tobacco taxation can reduce OOP health expenditures and the loss of income from smoking-related disease. Notably, analyses by the World Bank24 including from Fuchs and Meneses25 26 of tobacco taxes call into question the overall regressivity of tobacco taxation, and a number of extended cost-effectiveness analyses21 23 27 28 have demonstrated an overall progressive distributional impact across income groups of increased tobacco taxes when accounting for the additional outcomes of health benefits and financial risk protection.

Importantly, Remler,14 using the accounting definition of tax burden (net change in cigarette expenditures relative to income), qualitatively demonstrates that a tax increase can be progressive for certain income gradients in price elasticity of demand for tobacco and smoking prevalence. In this regard, a number of studies have quantitatively examined this distributional impact of higher tobacco taxes while accounting for differential price responsiveness across a range of income groups.14 29–35 Specifically, smokers of lower income have been shown to be more price sensitive to tobacco price increases than smokers of higher income.23 28 29 32 33 36–44 Likewise, adolescent and young adult smokers (aged 25 years and younger) are typically more price sensitive than adults to increased cigarette price.45 46 That is, as price increases, decrease in demand for cigarettes may be disproprortionately greater among price-sensitive populations. Therefore, increased tobacco taxes need not be inherently regressive when differential price sensitivity by income stratum is considered and thus provide a strategy to target price policies to populations with higher smoking prevalence.

In this paper, we aim to ascertain whether there are circumstances in which the impacts of additional tobacco taxes are not regressive, using a standard income-share accounting definition of tax burden. We employ the accounting definition of tax burden and study the distribution in the net change in tobacco taxes/expenditures following increased taxes. By focusing on such an incremental accounting measure of regressivity, many might disagree with this consideration of regressivity (ie, incremental vs baseline). We do not argue about how regressivity should be defined in the context of tobacco taxation, which we acknowledge is constitutive of the debate on whether tobacco taxes are deemed regressive, and multiple definitions of regressivity exist. Rather, our accounting focus contributes only one piece to this broader debate, which is beyond the scope of our paper, and has been well described.14 Specifically, we develop a mathematical model to examine the potential distributional impact of additional taxes and cigarette expenditures borne by individuals across income strata, using a range of hypothetical parameter values for the relative price change in cigarettes, the price elasticity of demand for tobacco and the prevalence of smoking and consumption of cigarettes. Subsequently, we highlight under which circumstances (ie, range of key parameter values), increased tobacco taxes may or may not be regressive from a standard income-share accounting point of view.

Methods

Modeling approach

We develop a simple mathematical model to examine the net change in the burden of tobacco tax across income groups following an increase in the retail price of cigarettes through taxation at the population level (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework summarising the distributional accounting model of increased tobacco taxation impacting on the net change in tobacco taxes (denoted ΔT(y), varying with income) and the net change in cigarette expenditures (denoted ΔC(y), varying with income) borne by individuals with income y.

The model incorporates the following parameters essential in the understanding of increased tobacco taxation: the prevalence of smoking ; the consumption of cigarettes per year (eg, the number of cigarette packs consumed by smokers); the retail price of cigarettes ( before increased taxation; after); the share of tobacco taxes within the retail price of cigarettes ( before increased taxation; after); the change in price (equal to the amount of increased taxation ); the price elasticity of demand for cigarettes ; and , the income of a given individual in the population. Smoking prevalence, cigarette consumption and price elasticity of demand all can vary with , hence, we denote: , and . Often, though not always, lower income groups smoke more29 47–49 and are more price sensitive than more affluent income groups.6 22 28 29 32 33 36–44 In what follows, for simplicity, we group smoking prevalence and consumption in one variable , which corresponds to total cigarette consumption (table 1). Importantly, we use an accounting definition to assess progressivity/regressivity of increased taxation (eg, net change in taxes and expenditures relative to income), which is one (among several possible) definition of tax burden as described elsewhere.14

Table 1.

Key input variables used in the mathematical model depicting the distributional impact of increased tobacco taxation using a standard income-share accounting definition of tax burden

| Input variable | Description |

| Individual income. | |

| s (y) | Smoking prevalence, varies with income. |

| c (y) | Consumption of cigarettes per year, varies with income. |

|

: before increased taxation. : after increased taxation. |

|

| Price elasticity of demand for cigarettes, varies with income. | |

| Retail price of cigarettes : before increased taxation. : after increased taxation. |

|

| Share of taxes within retail price of cigarettes : before increased taxation. : after increased taxation. |

|

| Change in retail price due to increased taxation. | |

| Relative change in retail price |

We now present the main elements of the mathematical model. Before increased taxation, at the population level, the total annual taxes borne by an individual with income (denoted ) corresponds to the total number of cigarettes consumed annually by the individual times the retail price of cigarettes and the tax share within the retail price:

| (1) |

After increased taxation, at the population level, the total annual taxes borne by an individual of income (denoted ) corresponds to the reduced number of cigarettes consumed annually by the individual () times the new taxes included in the new retail price ():

| (2) |

Subsequently, we can derive, at the population level, the net change in taxes borne by an individual of income (denoted ) in the following way:

| (3) |

Studying the regressivity (income-share accounting view) of the net change in taxes implies examining whether as a proportion of is greater for lower incomes than for higher incomes: this would mean that the tax increase is regressive. On the contrary, if as a proportion of is greater for higher incomes, this would mean that the tax increase is progressive. Given the mathematical formulation of , studying the regressivity implies exploring the monotonous character, with respect to , of the function . That is, regressivity would imply that decreases as increases. Mathematically, this means that we need to explore the sign of the first derivative with respect to of the function (see online supplementary webappendix, section 1).

tobaccocontrol-2019-055315supp001.pdf (274KB, pdf)

Similarly, we can study the net change in cigarette expenditures across incomes (denoted ) at the population level. Importantly, the net change in cigarette expenditures captures the net financial burden borne (seen) by individuals via increased taxation. Given the mathematical proximity between the retail price () and the tax share within the retail price (), we can derive mathematical expressions for the net change in cigarette expenditures that are consistent with those for the net change in cigarette taxes (see online supplementary webappendix, section 2).

Estimates for price elasticity of demand and smoking prevalence

There exists an abundant literature that has derived estimates for the price elasticity of demand for tobacco products, mostly for high-income countries and for low-income and middle-income countries.50–52 These studies exhibit aggregate demand estimates generally ranging between −1.20 and 0.00. For the USA, aggregate estimates were clustered around −0.60 to −0.20; and for low-income and middle-income countries, they varied from −1.00 to −0.20. In addition, it was found that lower income groups would be substantially more price responsive than higher income groups.29 For instance, demand estimates could range from −1.00 among the lowest income group to 0.00 among the highest income group in the UK and Thailand36 53, and/or they could be twice as high among the lowest (vs highest) income group in the USA, Canada, Korea, Indonesia and Turkey.33 35 43 44 54 Lastly, young people are more responsive (two to three times45) than older adults to changes in prices of tobacco products: demand estimates among young people could be as high (in absolute value) as −2.20 or −1.50.46 55 In light of these empirical estimates (table 2), in our model, we conservatively assumed that price elasticity of demand for tobacco (; ) could vary within −1.00 to −0.20.

Table 2.

Selected observed estimates for the price elasticity of demand for tobacco products and the prevalence of smoking across income groups, various countries and time-periods

| Country | Time-period of study | Data, population and geographical setting | Estimates of price elasticity of demand for tobacco products | Comments | Source |

| Aggregate demand estimates | |||||

| International | Various studies 1993–2004 | Cross-sectional, nationally representative studies. | The central theme of this report is an examination of the effectiveness of tobacco taxation, and an in-depth summary of published literature is reviewed and synthesised. | 50 | |

| USA | As above. | As above. | −1.00 to −0.10 (clustered around −0.60 to −0.20) | As above. | 50 |

| Other high-income countries | As above. | As above. | −1.20 to 0.00 (clustered around −0.60 to −0.20) | As above. | 50 |

| Low-income and middle-income countries | As above. | As above. | −1.00 to −0.20 | As above. | 50 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | Not restricted. | Various: systematic review and meta-analysis including 23 studies published between 1998 and 2015. | −0.51 to −0.35 | Analyses included: 10 studies classified as ‘poor methodology/reporting’; five cross-country studies; five using aggregate-level data; two using household-level data. No studies with individual-level data. Limited data quality; quality assessment not formally conducted. | 51 |

| China | 1990–2007 | Used official national level statistics from China's statistics yearbook, China National Bureau of Statistics, China Tobacco Statistics Yearbook and China National Tobacco Company. | −0.84 to −0.01 | China’s state-owned tobacco monopoly set prices for much of time-period but since 2001 foreign brands being sold. Prior to 2005 tobacco leaf was taxed at 31% of the retail price but reduced to 20% in 2006; cigarette taxes before 2009 included specific excise tax+ad valorem tax for higher priced products (class A). Tax structure has in 2009 changed (increased), but this is not covered by study time-period. | 52 |

| Demand estimates among the poor* | |||||

| USA | 1993–2003 | Six pooled cross-sections from Current Population Survey (CPS) Tobacco Use Supplements merged with CPS March Income Supplements. Complete data for 294 693 adult respondents. | -0.37 (poor) to -0.20 (rich) | Published data for weighted average state price converted into real 1997 values using Consumer Price Index. Prices per cigarette and consumption of cigarettes per day. | 33 |

| USA | 1976–1993 | Six pooled cross-sections of data from the National Health Interview Survey administered to a nationally representative multistage probability sample of the non-institutionalised civilian population aged ≥18 years. | −0.29 to −0.17 | Average real price of cigarettes for each state obtained using data reported by Tobacco Institute. 80% of overall response rate. | 37 |

| UK | 1972–1990 | Pooled biennial cross-sections using a random sample of UK adults interviewed for general household surveys. | −1.00 to 0.00 | Tracks real price of cigarettes over time-period relative to other prices and average incomes. Prevalence defined by proportion of adults smoking >1 cigarette a day and combining number of cigarettes smoked per smoker by sex/age/SES group to yield average consumption per adult per group. | 36 |

| Canada | 1981–1999 | Eight cross-sections of household-level data from Canadian Survey of Family Expenditure, later renamed Survey of Household spending, comprising a total of 81 479 observations. | −0.99 to −0.36 | Significant cross-province and time-series variation in both federal and provincial cigarette taxes over time-period including in excise taxes, excise duties and sales taxes. Average prices per 200 cigarettes for each province between 1989 and 1993 obtained from Statistics Canada and province-specific prices in other years used to extrapolate these figures to the rest of the period and combined with data on the total legal sales of cigarettes for each province. | 35 |

| Korea | 1998–2011 | Seven pooled cross-sections of individual smoking-related records from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. | −0.81 to −0.34 | Real price of a typical 20-cigarette pack used. Cigarette manufacturing industry was a government-owned monopoly setting prices until 2002, when the industry was privatised and prices deregulated. Premium brands introduced after 2002, but price of a typical pack remained unchanged with no substantial changes in cigarette taxes over time-period. Individual-level data. | 43 |

| Indonesia | 1999 | Single cross-section using Social and Economic Survey household data combining core and module questionnaires of 60 602 households. Average per person data derived using average household size. | −0.67 to −0.31 | Information on cigarette price not available, but information on household expenditures and cigarettes consumption by brand available. Prices paid by smoker households estimated from data. Non-smoker household prices assumed similar to smoker households with similar SES and demographic profiles. | 54 |

| South Africa | 1990–1998 | Combination of subset of nationally representative cross-sectional datasets for urban respondents: income and expenditure surveys of 1990 and 1995; 1993 Southern African Labour and Development Research Unit survey; 1998 KwaZulu-Natal Income Dynamics Survey. Analyses performed on 16 903 observations. 1990 surveys are primarily urban based for the whole country; rural respondents are thus excluded from analyses. | −1.39 to −0.81 | Price variation between brands noted to be remarkably low during time-period. Analyses investigate consumption patterns, and tobacco expenditures on cigarettes and other products but focus on cigarette expenditures given that these make the majority of total tobacco expenditures. | 39 |

| Thailand | 2000 | Cross-sectional household-level data from household socioeconomic survey (SES2000) with analyses based on 11 968 households spending some amount on tobacco monthly. | −1.00 to −0.04 | Thais spend 3% of total expenditures on cigarettes. Since March 2001 excise tax has been 75% of the retail price. Cigarette expenditures compared with expenditures on other goods at the household level. | 53 |

| Turkey | 2003 | Single cross-section using Turkish Household Expenditure Survey (nationally representative, randomly selected households) for urban and rural areas in 12 regions. Total number of households of 25 764. | −1.41 to −0.74 | Self-reported cigarette expenditures, and consumption and general expenditure patterns recorded at household level along demographic and other SES indicators. | 44 |

| Demand estimates among young people | |||||

| International | Various. | Various. | −1.44 to 0.00 | 29 45 50 | |

| Low-income and middle-income countries | 1999–2006 | Various: merged individual-level data from Global Youth Tobacco Survey with country-level data on local cigarette prices from Economist Intelligence Unit's World Cost of Living Survey. Final dataset with 315 355 individuals of 17 countries corresponding to 113 cities or provinces. | −2.11 | 46 55 | |

| Low-income and middle-income countries | 1999–2008 | Various: estimates on cigarette prices on youth smoking derived in 38 countries having completed more than 1 wave of school-based Global Youth Tobacco Survey, and with income and price data. | −2.20 | 55 | |

| High-income and low-income and middle-income countries | As above. | As above. | −1.50 | 55 | |

| Difference in smoking prevalence across income† | Difference in smoking prevalence across income | ||||

| Low-income and middle-income countries | Not restricted. | Various: summary of published studies. | 1–2 times higher prevalence among the poor (vs rich) | 29 | |

| WHO regional analyses | Not restricted. | Various: systematic review and meta-analysis of 93 studies forming 164 datasets for 6 WHO regions. Time-period not specified, studies published between 1989 and 2013 included. | 47 | ||

| WHO Americas region | As above. | As above. | 1.4–1.7 times higher among poor | ||

| WHO Europe region | As above. | As above. | 1.3–1.6 times higher among poor | ||

| WHO Southeast Asia region | As above. | As above. | 1.1–2.0 times higher among poor | ||

| WHO Western Pacific region | As above. | As above. | 1.2–1.6 times higher among poor | ||

| WHO African region | As above. | As above. | 1.0–1.6 times higher among poor | ||

For WHO definition of regional grouping: https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/regional-offices.

*The price elasticity of demand is reported from the lowest (poor) to the highest (rich) income group for which it was estimated in the study.

†The ratio of smoking prevalence between the lowest (poor) and highest (rich) income group is reported for a group of countries as estimated in the study.

SES, socioeconomic status.

With respect to smoking prevalence, our literature review29 47–49 found that in a wide variety of countries (high income, low income and middle income), there could be as many as one to two times more smokers among the lowest (vs highest) income group (table 2). Therefore, in our model, we assumed that smoking prevalence would decrease as income increases, and we applied a variety of negative income gradients in smoking prevalence.

Case studies examined

For ease of interpretation, we assumed that price elasticity was linearly changing with income : ; is the income gradient in elasticity and the elasticity for individuals with lower income (ie, the poorest) (note that the young, with less disposable income, would be more concentrated among the poorest). This is consistent with the expectation that elasticity would decrease (in absolute value) with income (table 2). We also assumed that smoking and consumption (total cigarette consumption) would vary linearly with : ; is the income gradient in cigarette consumption and the consumption for the poorest. This would be consistent with the expectation that smoking prevalence and consumption decrease with income (table 2). Potentially, other mathematical expressions (in lieu of linear functions) for and could be selected but would unnecessarily complicate our analysis without giving additional insight. The resulting mathematical expressions are detailed in the online supplementary webappendix, section 3.

We studied parametrically two scenarios. Scenario 1 assumed total cigarette consumption constant across income: . Scenario 2 relaxed this assumption with . In our study, income was normalised: ; and defined lower (poorest) and higher (richest) incomes, respectively. We denoted the relative change in cigarette price. We then examined when the resulting net cigarette taxes and expenditures would be regressive, progressive or neutral across income, and we quantified the extent of those situations.

Lastly, we applied our model to a number of country case studies including specific populations, time-periods, cigarette retail prices and tax regimes, which covered a parameter space drawn from empirical studies and reasonable assumptions (table 3).

Table 3.

Selection of country case studies including specific populations, time-periods, cigarette retail prices and cigarette tax regimes

| Country | Philippines | Colombia | Bulgaria | Sweden | UK | |

| Rationale* | Lower middle-income country; moderate smoking (high among males); doubled excise tax rate over 2012–2017. | Upper middle-income country; recent advances in TC policies; introduced tax hike in 2016. | Upper middle-income country; high tax rate; generally strong TC response. | High-income country; lower tax rate relative to other European countries; generally strong TC response. | High-income country; high tax rate; strong TC response. | |

|

Income†

GNI per capita (current 2018 USD) |

3830 | 6190 | 8860 | 55 040 | 41 340 | |

| Smoking prevalence* | ||||||

| WHO age-standardised estimated prevalence of current cigarette smoking (% of ages 15 years and above, 2017) | Adult Male Female |

22.4 38.4 6.4 |

7.3 11.2 3.5 |

36.0 45.0 28.0 |

12.9 11.0 14.8 |

15.1 17.0 13.3 |

| Cigarette consumption* | ||||||

| Per person per year (ages 15 years and above, 2016)‡ | Number of cigarettes | 1132 | 351 | 1282 | 666 | 828 |

| Number of 20-cigarette packs | 57 | 18 | 64 | 33 | 41 | |

| Retail price and taxes*§ | ||||||

| Retail price, 20-cigarette pack, most sold brand (USD, 2014–2018) | 1.08 | 1.39 | 3.21 | 8.55 | 12.37 | |

| Total taxes on most sold brand, 2018 | 71.3% | 78.4% | 82.7% | 68.8% | 82.2% | |

| Tobacco tax hike*§¶ | ||||||

| Year of tax hike (pre and post)** |

Pre: 2012. Post: 2014. |

Pre: 2016. Post: 2018. |

2005–2014 | 2005–2014 | 2005–2014 | |

| Retail price of most sold brand, prehike (USD) | 0.36 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 4.93 | 7.87 | |

| Retail price of most sold brand, posthike (USD) | 0.62 | 1.39 | 1.60 | 6.37 | 9.48 | |

| Change in price (USD) |

0.26 | 0.51 | 0.80 | 1.44 | 1.61 | |

| Price elasticity§††‡‡ | ||||||

| Aggregate demand estimates | −0.87 | -0.51 to -0.35 | -1.33 to -0.52 | −0.50 | −0.50 |

All mathematical derivations and computations are provided in the online supplementary webappendix and were conducted using Mathematica (version 11.2.0.0, Wolfram Research, Inc).

Results

We report in this section on the examination of the evolution of the net changes in additional taxes and cigarette expenditures, respectively.

Net change in additional taxes

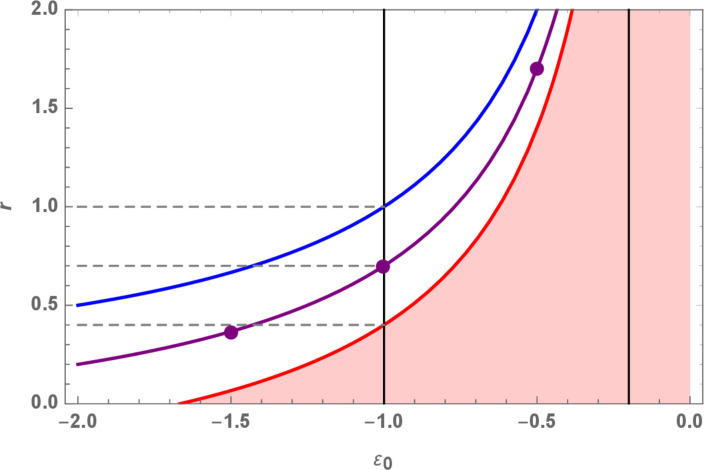

For scenario 1 (constant consumption across income: ), for the net change in additional taxes to be progressive, the relative price change would need to increase as decreases (in absolute value) (to remain above the beam of curves; figure 2). The beam of curves (blue, purple and red) indicate when the ratio of net taxes divided by income is equal across all income groups (which we call the ‘neutrality’ frontier). Above the curves (‘progressivity’ area), the ratio will increase with income increasing; below (‘regressivity’ area), it will decrease with income increasing.

Figure 2.

Neutrality frontier (blue, purple or red): relative price increase () as a function of price elasticity of demand for the poorest individuals () for different values of the initial tax share within the retail price (0=blue (top), 0.30=purple (middle), 0.60=red (bottom)) for which the ratio of net taxes with income is equal across all income groups. Note: the vertical black lines (at and ) delimit a plausible range of price elasticity estimates for the poorest individuals (see estimates from table 2). The bottom-right pink-shaded area indicates a () parameter space for which the net change in taxes will always be regressive (for an initial tax share within the retail price of ). The purple points display three combinations of the (; ) parameters ({−1.50; 0.37}, {−1.00; 0.70} and {−0.50; 1.70}) located on the neutrality frontier when the initial tax share within the retail price is (purple curve).

For example, according to the purple curve (figure 2): when and (at least a 37% price increase), when and or when and , then the net change in taxes would be progressive (these and r estimates (−1.50 and 0.37; −1.00 and 0.70; −0.50 and 1.70) are for an initial tax share t 1=0.30 (30%) within the retail price (neutrality frontier marked by the purple curve on figure 2)). This means that progressivity in net taxes would be obtained as long as and are sufficiently large (spanning the parameter space above the beam of curves), and this progressivity would be mitigated by the initial tax share within the retail price: a higher would require lower neutrality frontier values for and (shift from blue to purple to red curve). The bottom-right pink-shaded area indicates the parameter space of and for which net taxes would be regressive with . With a null initial tax share , when price elasticity among the poorest equals −1.00, reaching the neutrality frontier would require a 100% relative price change (); with , when , it would require ; and with , when , it would require . Where initial levels of taxes () are low, larger increases in retail price are necessary to yield progressivity in net taxes.

In scenario 2, when total cigarette consumption varies across income (), the net taxes would be progressive as long as two conditions are fulfilled. First, consistent with scenario 1, and would need to be sufficiently large (same condition as described above; figure 2): for example, (elasticity among the poorest of −1.00) and (price increase of 60%) would fulfil this first condition (with ). Second, provided the former condition is realised, the income gradient in price elasticity (, from poorest to richest) and the income gradient in cigarette consumption (, from poorest to richest) would need to evolve within a certain parameter space.

For instance, take , , and cigarette consumption among the poorest of (equivalent to smoking prevalence of 30% and daily consumption of 10 cigarettes). When consumption gradients (eg, corresponding to prevalence spanning from 30% (among the poorest) to 10% (among the richest); blue curve on figure 3a), reaching full progressivity (horizontal black line) would require elasticity gradients (range spanning within −1.00 (among the poorest) to −0.86 (among the richest)). When (prevalence from 30% to 20%; comparable with gradients in table 2; red curve), reaching full progressivity would require (elasticity spanning within −1.00 to −0.73).

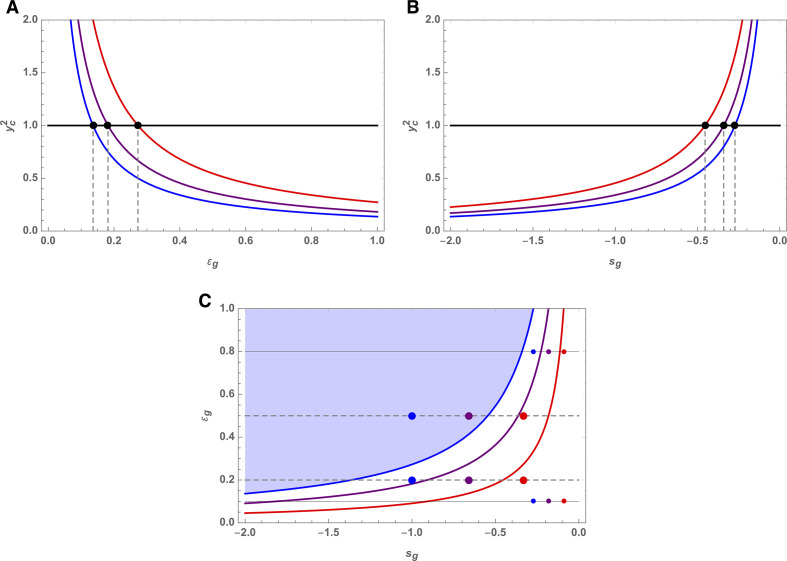

Figure 3.

Value of the cut-off function .(A) Varying with income gradient in price elasticity (while , , , are held constant).(B) Varying with income gradient in cigarette consumption (while , , , are held constant). Full progressivity, where the ratio of net taxes with income increases with income across all income groups, is obtained when . Partial progressivity, when and where: the ratio of net taxes with income increases with income for incomes within ; and the ratio of net taxes with income decreases with income for incomes within .(C) Full progressivity frontier (blue (top), purple (middle), and red (bottom) curves, where ): income gradient in price elasticity () as a function of income gradient in cigarette consumption () for which the ratio of net taxes with income increases with income across all income groups. Note: figure parts A and B use the following parameter values: initial tax share , price elasticity for the poorest , relative price increase and total cigarette consumption for the poorest (ie, 30% smoking prevalence and 10-cigarette daily consumption). In figure part A, varies from −2.0 (blue (bottom), prevalence from 30% to 10% from poorest to richest), −1.5 (purple (middle), from 30% to 15%), to −1.0 (red (top), from 30% to 20%). In figure part B, varies from 1.00 (blue (bottom), elasticity span of −1.00 to 0.00, from poorest to richest), 0.80 (purple (middle), span of −1.00 to −0.20) to 0.60 (red (top), span of −1.00 to −0.40). When (horizontal black line), the net change in additional taxes will be fully progressive. Figure part C uses the following parameter values: , , and various values of : (blue (top), ie, 30% smoking prevalence and 10-cigarette daily consumption), (purple (middle), ie, 20% prevalence and 10-cigarette daily consumption) and (red (bottom), ie, 10% prevalence and 10-cigarette daily consumption). The top-left blue-shaded area indicates a () parameter space for which the net change in taxes will be partially progressive (for ). The beam of curves (blue, purple and red) indicate the full progressivity frontier: below the beam of curves, the net change in taxes will be fully progressive; above, it will be partially progressive. The large coloured points (for ) display larger consumption gradients () corresponding to 1.5 times greater consumption among the poorest versus richest; the small coloured points () display smaller consumption gradients (), that is, 1.1 times greater consumption among the poorest versus richest.

Conversely, when (elasticity spanning from −1.00 (poorest) to 0.00 (richest); comparable with gradients in table 2; blue curve on figure 3b), reaching full progressivity (horizontal black line) would require (prevalence from poorest to richest within 30% to 27%). When (elasticity spanning from −1.00 to −0.40; comparable with table 2 gradients; red curve), reaching full progressivity would require (prevalence spanning within 30% to 25%).

In sum, when gradients in cigarette consumption () are large (say 1.5 times greater consumption among the poorest than the richest; see large coloured points on figure 3c), gradients in price elasticity () need to be smaller (see 0.20 vs 0.50 points) for net taxes to be fully progressive. Conversely, when gradients are small (say 1.1 times greater consumption among poorest; see small coloured points on figure 3c), gradients can be either small or large (see 0.10 and 0.80 points) for net taxes to be fully progressive. Otherwise, net taxes will only be partially progressive within a certain subgroup of incomes (from (poorest) until a cut-off normalised income ).

Net change in cigarette expenditures

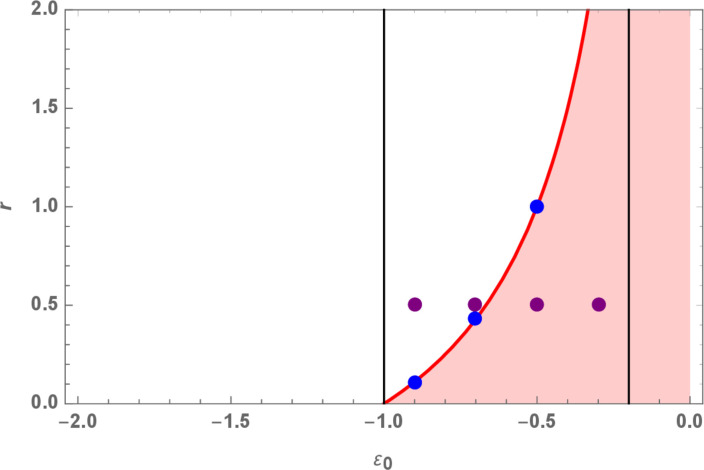

We now turn to net cigarette expenditures, which captures the net financial burden borne (observed) by individuals. In scenario 1, constant consumption across income (), figure 4 shows the relationship between relative price increase () and price elasticity for the poorest individuals () for which the ratio of net expenditures divided by income is equal across income (which we call the neutrality frontier). As increases, would need to increase (to remain above the red curve) so that net expenditures are progressive: for example, to increase from when , to when , and to when . Progressivity would require sufficiently high price elasticity (large absolute values): for instance, for , would need to be so that net cigarette expenditures are progressive.

Figure 4.

Neutrality frontier (red curve including blue points): relative price increase () as a function of price elasticity of demand for the poorest () for which the ratio of net cigarette expenditures with income is equal across all income groups. Note: the vertical black lines (at and ) delimit a plausible range of price elasticity estimates for the poorest (see estimates from table 2). The bottom-right pink-shaded area indicates a () parameter space for which the net change in cigarette expenditures will always be regressive. The horizontal purple points display four combinations of the (; ) parameters (all for a relative price increase ): {−0.90; 0.50}, {−0.70; 0.50}, {−0.50; 0.50} and {−0.30; 0.50}. For {−0.90; 0.50}, {−0.70; 0.50}, the net cigarette expenditures will be progressive (beyond pink-shaded area), while for {−0.50; 0.50} and {−0.30; 0.50}, the net cigarette expenditures will be regressive (within pink-shaded area).

In scenario 2, when consumption varies across income (), the net change in cigarette expenditures will be progressive as long as two conditions are fulfilled. First, consistent with scenario 1, and need to be sufficiently large (same condition as above; figure 4): for example, when and , this first condition is realised. Second, provided this former condition is fulfilled, (gradient in elasticity) and (gradient in consumption) need to remain within a certain parameter space (figure 5).

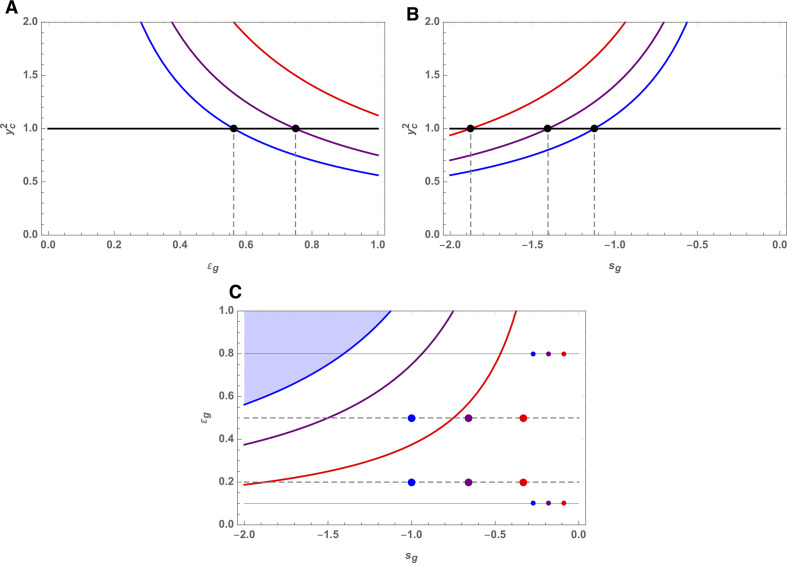

Figure 5.

Value of the cut-off function .(A) Varying with income gradient in price elasticity (while , , are held constant).(B) Varying with income gradient in cigarette consumption (while , , are held constant). Full progressivity, where the ratio of net cigarette expenditures with income increases with income across all income groups, is obtained when . Partial progressivity, when and where: the ratio of net expenditures with income increases with income for incomes within ; and the ratio of net expenditures with income decreases with income for incomes within .(C) Full progressivity frontier (blue (top), purple (middle) and red (bottom) curves, where ): income gradient in price elasticity () as a function of gradient in cigarette consumption () for which the ratio of net cigarette expenditures with income increases with income across all income groups. Note: figure parts A and B use the following parameter values: price elasticity for the poorest , relative price increase , and total cigarette consumption for the poorest (ie, 30% smoking prevalence and 10-cigarette daily consumption). In figure part A, varies from −2.0 (blue (bottom), prevalence from 30% to 10% from poorest to richest), −1.5 (purple (middle), from 30% to 15%), to −1.0 (red (top), from 30% to 20%). In figure part B, varies from 1.00 (blue (bottom), elasticity span of −1.00 to 0.00, from poorest to richest), 0.80 (purple (middle), span of −1.00 to −0.20), to 0.60 (red (top), span of −1.00 to −0.40). When (horizontal black line), the net change in cigarette expenditures will be fully progressive. Figure part C uses the following parameter values: , and various values of : (blue (top), ie, 30% smoking prevalence and 10-cigarette daily consumption), (purple (middle), ie, 20% prevalence and 10-cigarette daily consumption) and (red (bottom), ie, 10% prevalence and 10-cigarette daily consumption). The top-left blue-shaded area indicates a () parameter space for which the net change in cigarette expenditures will be partially progressive (when ). The beam of curves (blue, purple and red) indicate the full progressivity frontier: below the beam of curves, the net change in expenditures will be fully progressive; above, it will be partially progressive. The large coloured points (for ) display larger consumption gradients () corresponding to 1.5 times greater consumption among the poorest versus richest; the small coloured points () display smaller consumption gradients (), that is, 1.1 times greater consumption among the poorest versus richest.

For instance, take , and (corresponding to smoking prevalence of 30% and daily consumption of 10 cigarettes for the poorest). When consumption gradients (smoking prevalence spanning from 30% (among the poorest) to 10% (among the richest); blue curve on figure 5a) reaching full progressivity would require elasiticity gradients (elasticity span within −1.00 to −0.44 from poorest to richest; comparable to gradients in table 2). When (smoking prevalence spanning from 30% to 15%; purple curve), it would require (elasticity span within −1.00 to −0.25; comparable with table 2 gradients).

Conversely, when (elasticity span of −1.00 (among the poorest) to 0.00 (among the richest); comparable with table 2 gradients; blue curve on figure 5b), reaching full progressivity would require (smoking prevalence >19% among the richest). When (elasticity span of −1.00 to −0.40; comparable to gradients in table 2; red curve), it would require (smoking prevalence >11% among the richest).

In sum, when consumption gradients are large (say 1.5 times greater among the poorest than the richest; see large coloured points on figure 5c), elasticity gradients can span the whole parameter space (from 0.00 to 1.00) and net expenditures will be fully progressive. Likewise, when gradients are small (say 1.1 times greater among the poorest; see small coloured points), gradients can also span the whole parameter space and net expenditures will be fully progressive. Solely when larger gradients (say 2.0 times greater among the poorest) coexist with large gradients (within 0.60 to 1.00) (see blue-shaded area on figure 5c), net cigarette expenditures will only be partially progressive within a certain subgroup of incomes (from (poorest) to a cut-off normalised income ).

Instances of progressivity, regressivity and neutrality

We synthesise here our findings by reporting on parameter spaces for which we would observe progressivity, regressivity or neutrality for the net cigarette expenditures.

First, consider when (figure 4), we would obtain neutrality in net expenditures for the following situations (see blue points on the neutrality frontier): , and . Thus, for , the ratio of net expenditures divided by income would be equal (neutral) for . When , the ratio would be larger for the poorest than for the richest; when , the ratio would be smaller for the poorest. Similarly, for , the ratio would be neutral for . When , the ratio would be larger for the poorest; when , it would be smaller for the poorest. For , neutrality would be obtained for . When , regressivity would incur; otherwise, progressivity would incur. In sum, for large price hikes (50% and more) and observable elasticity estimates ( within −1.00 to −0.50; see table 2), net cigarette expenditures would be progressive.

Conversely (examining horizontal purple points on figure 4), when setting price increase , when , progressivity would incur, with potentially net negative expenditures for the poorer () compared with other income groups () (recall income was normalised: 0≤y≤1; y=0 and y=1 would define lower (poorest) and higher (richest) incomes, respectively. Therefore, y=0.5 would define median (middle) income; while y=0.1<0.5 would define poorer incomes and y=0.9>0.5 would define richer incomes). When , we would still observe progressivity, with a share-income of expenditures 1.8 times greater among the richer () than the poorer (). However, when , we would see regressivity, with a share-income of expenditures 3.2 times greater among the poorer than the richer. Likewise, when , we would see a share-income of expenditures 5.6 times greater among the poorer. Lastly, when , we would observe regressivity, with a share-income of expenditures 7.9 times greater among the poorer.

Second, consider when and take (elasticity among the poorest) and (price increase of 60%). We could observe full progressivity (figure 5; online supplementary webappendix figure S3) for different values of , and (online supplementary webappendix, section 4). The likelihood of progressivity would increase when: values of consumption gradients are small (combined with either small or large elasticity gradients ); or large values of are combined with small values of .

Third, take selected country case studies (table 3; online supplementary webappendix, section 5), we would see a variety of outcomes. On the one hand, relative price increases of 72% and 100% in the Philippines and Bulgaria, respectively, would lead to progressivity in net cigarette expenditures; on the other hand, price increases of 58%, 29% and 20% in Colombia, Sweden and the UK, respectively, would lead to regressivity in net cigarette expenditures.

If addiction were added to our model, it could affect overall price elasticity of demand. One could envision a fraction of smokers with strong addiction, hence who would not quit or reduce consumption with increased taxation (for each income , which we could denote ; see online supplementary webappendix, section 6). In this case, if poor smokers were more addicted than rich smokers, progressivity in net expenditures could be impacted proportionally to the relative fraction of addicted smokers among the poor compared with the rich.

Lastly, in the rare cases of settings where smoking prevalence and consumption increase with income (eg, Georgia and Mexico),48 for sufficiently large price increases and price elasticity among lower incomes, net cigarette expenditures would be progressive.

Discussion

We developed a mathematical model to demonstrate the circumstances in which the impacts of additional tobacco taxes are not regressive, using a standard income-share accounting definition of tax burden. Using an accounting definition of tax burden (net expenditures relative to income), we find that increased tobacco taxes are not inherently regressive in consumption. We demonstrated that for sufficiently large price elasticity of demand for tobacco products and large price increases (eg, 50% and more), the distribution in net cigarette expenditures could be progressive. That is, the model shows that when a susbantial price increase (50%–100%) is applied, we can expect a progressive decrease in demand (with ranges in price elasiticity across income groups of between −1.00 and −0.20), which would translate into fewer people smoking with direct implications for improved health outcomes. Such progressivity is conceivable as large price elasticities of demand for tobacco among the poor, and especially among the young, have been observed in many countries (tables 2 and 3), and policies of 50% increases and above in the price of tobacco have been enacted in numerous countries and would be necessary to bring taxation levels up to MPOWER recommendations in many settings.7

Fundamentally, our findings rest on the use of one (among many possible) definition of tax burden: the standard income-share accounting definition.14 Therefore, using other interpretations of tax burden, increased tobacco taxes could well be categorised differently. For example, in spite of progressive increases, an already regressive baseline tobacco tax (before increased taxation) may remain. Also, our income-share accounting ignores individual valuation of consumption changes and associated welfare-based willingness to pay of individuals who may see foregone utility in reduced cigarette consumption. Likewise, income-share accounting does not consider welfare-based time-inconsistent preferences and internalities of individuals who may regard taxes as a commitment device forcing them to quit in the long term, which they cannot realise in the short term.20 In summary, we acknowledge that we approached the question of regressivity of tobacco tax from a standard technical accounting point of view only, even though this question could be scrutinised via multiple economical and philosophical lenses, all of which are subject to controversy.

Our mathematical exploration confirms the fact that in specific circumstances increased tobacco taxes could lead to reductions in the burden of cigarette expenditures borne by individuals, as seen under certain scenarios tested via simulation models.23 In this respect, particularly large tax increases could prevent tobacco taxes from being regressive in terms of consumption and net cigarette expenditures. This is in addition to large tax increases leading to broader health benefits (reduction in premature mortality and morbidity) and financial risk protection benefits (reduction of impoverishment related to tobacco-related disease care and work productivity losses).21 Furthermore, revenues raised via tobacco tax hikes could be redistributed progressively to lower income populations.

Nevertheless, our model presents a number of limitations. First, we have made a number of simplifications in the parameter selection, such as the monotonous nature of some of the inputs, for ease of interpretation. However, this would not affect the generalisability of our findings. Second, we examined regressivity in consumption across income groups at the population level and did not examine regressivity within the individuals who continue smoking or those individuals who quit smoking. Evidently, as rightly pointed by Remler,14 in the absence of other demand-side measures, any individual with inelastic demand (which would include those smokers most addicted) would be economically burdened. Consequently, for the subset of persons across income groups who are price inelastic and continue smoking, increased tobacco taxes will always be regressive.14 For instance, poorer individuals who do not quit or reduce consumption would be financially harmed. When a greater proportion of those most addicted exists among lower (vs higher) income groups, regressivity could be enhanced proportionally with the relatively greater fraction of addicted among lower income groups. This can be observed in terms of reduced overall price elasticity among lower income groups, thus reduced variation in price elasticity across income groups.56 Yet, in the absence of empirical data on the distribution of addiction levels among smokers of different incomes, such disaggregated analyses remain difficult to implement. Overall, this underscores the importance of implementing tax policy within a broad framework of demand-side measures, particularly those that reduce the burden of addiction associated with socioeconomic deprivation. Third, we used a static model, which assumes immediate impact of the tax on consumption and did not look at transition periods. For example, we did not consider the ‘stage’ of the cigarette epidemic on a per-country basis,57 the prevalence of smoking or factors that are associated with future cessation, such as social acceptability of smoking, health communications and smoke-free laws.58 Neither did we examine long-term net impacts of increased taxes (eg, reduction in future tobacco-related medical costs and associated catastrophic expenditures; use of new fiscal revenues to roll-out interventions promoting equity), which could further improve progressivity.24 Fourth, our model did not account for the variety in cigarette brands consumed differentially across income groups. As lower income individuals would consume cheaper brands, increased taxes would likely have a larger impact on the price of cheap (vs expensive) cigarettes, thus contributing to a greater price response among lower income groups and enhancing tax progressivity. This could also occur in the (rare) instances where smoking consumption increases with income (eg, Georgia and Mexico).48 Lastly, as we used an accounting definition of tax burden, our model would not capture welfare dimensions of taxation (willingness to pay for foregone cigarettes, time-inconsisent preferences and internalities), estimations of deadweight losses and losses of consumer surpluses among lower income individuals no longer consuming tobacco that they would value otherwise, all of which could enhance regressivity.14 33

However, while relaxing the inherent regressivity of tobacco taxes (from a standard accounting viewpoint), our analysis supports the importance of increased tobacco taxes in reducing demand for smoking, and thus comprising a critical strategy in curbing the predicted tobacco death toll for the 21st century.59 In particular, specific excise taxes that narrow the gap between cheaper and more expensive cigarettes are still underused globally,4 especially in emerging economies where they could prevent a burgeoning epidemic.

Finally, tobacco taxes are just one type of ‘sin tax’, like taxes on alcohol, fats and sugary drinks, where arguments for regressivity have hampered broad adoption. Our analysis furthers the case for implementation of large increases in tobacco taxation: in addition to being life saving, revenue raising and progressive in the totality of their effects, we show that under certain circumstances and when appropriately targeted to subpopulations with disparate rates of smoking, tobacco excise taxes need not be inherently regressive in consumption.

What this paper adds?

Tobacco taxes are often considered regressive, undermining efforts to fully implement them at levels recommended by WHO.

We point to a set of circumstances in which increased tobacco taxation should not be considered to penalise the poorest income groups, using a standard income-share accounting definition of tax burden when examining marginal cigarette consumption expenditures.

Our findings question the doctrine that tobacco taxes are uniformly regressive from a standard income-share accounting view.

Footnotes

Presented at: Earlier versions of this paper were presented during seminars at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Centre for the Evaluation of Value and Risk in Health, Tufts Medical Centre, where we received valuable comments from seminar participants. We are indebted to three anonymous reviewers for constructive and helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Contributors: SV conceived and designed the study. SV conducted the analysis with inputs from VWR amd PKAK. SV wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which VWR and PKAK reviewed and edited.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation . GBD compare. Available: http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare [Accessed 26 May 2019].

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for the Western Pacific, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) . The bill China cannot afford: health, economic and social costs of China’s tobacco epidemic. Manilla: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. GBD 2015 Tobacco Collaborators . Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet 2017;389:1885–906. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30819-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization (WHO) . WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization (WHO) . WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Available: http://www.who.int/fctc/en/ [Accessed 14 Jul 2018].

- 6. Chaloupka FJ, Yurekli A, Fong GT. Tobacco taxes as a tobacco control strategy. Tob Control 2012;21:172–80. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jha P, Peto R. Global effects of smoking, of quitting, and of taxing tobacco. N Engl J Med 2014;370:60–8. 10.1056/NEJMra1308383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Linegar DJ, van Walbeek C. The effect of excise tax increases on cigarette prices in South Africa. Tob Control 2018;27:65–71. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. United States National Cancer Institute and World Health Organization . The economics of tobacco and tobacco control. NCI monograph # 21. NIH publication No. 16-CA-8029A. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; and Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), World Health Organization . Chapter 7: Tax, price and tobacco use among the poor.. : IARC Handbook of cancer prevention, volume 14: effectiveness of Tax and price policies for tobacco control. Lyon, France: World Health organization, 2011. https://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/prev/handbook14/handbook14.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization . MPOWER. Available: http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/en/ [Accessed 7 Sep 2018].

- 12. Van Walbeek C, Filby S. Analysis of Article 6 (tax and price measures to reduce the demand for tobacco products) of the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Tobacco Control 2019;28:s97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Warner KE. The economics of tobacco: myths and realities. Tob Control 2000;9:78–89. 10.1136/tc.9.1.78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Remler DK. Poor smokers, poor quitters, and cigarette tax regressivity. Am J Public Health 2004;94:225–9. 10.2105/AJPH.94.2.225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stiglitz J. Economics of the public sector. 3rd edn. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ross H, Chaloupka FJ. Economic policies for tobacco control in developing countries. Salud Publica Mex 2006;48:s113–20. 10.1590/S0036-36342006000700014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Bank . Curbing the epidemic - governments and the economics of tobacco control. Washington, DC: World Bank, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Furman J. Six lessons from the U.S. experience with tobacco taxes. World Bank conference: “Winning the Tax Wars: Global Solutions for Developing Countries”, 2016. Available: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/page/files/20160524_cea_tobacco_tax_speech.pdf [Accessed 14 Jul 2018].

- 19. Gupta S. Response of the International monetary fund to its critics. Int J Health Serv 2010;40:323–6. 10.2190/HS.40.2.l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gruber J. Smoking’s internalities. Regulation 2002;2003:52–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Verguet S, Gauvreau CL, Mishra S, et al. The consequences of tobacco tax on household health and finances in rich and poor smokers in China: an extended cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e206–16. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70095-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blakely T, Cobiac LJ, Cleghorn CL, et al. Health, health inequality, and cost impacts of annual increases in tobacco tax: multistate life table modeling in New Zealand. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1002211. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Salti N, Brouwer E, Verguet S. The health, financial and distributional consequences of increases in the tobacco excise tax among smokers in Lebanon. Soc Sci Med 2016;170:161–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fuchs A, Márquez PV, Dutta S, et al. Is tobacco taxation regressive? evidence on public health, domestic resource mobilization, and equity improvements. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fuchs A, Meneses FJ. Are tobacco taxes really regressive?: evidence from Chile. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fuchs A, Meneses FJ. Regressive or progressive? the effect of tobacco taxes in Ukraine. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27. James EK, Saxena A, Franco Restrepo C, et al. Distributional health and financial benefits of increased tobacco taxes in Colombia. Tobacco Control 2019;28(4):374–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Postolovska I, Lavado R, Tarr G, et al. The health gains, financial risk protection benefits, and distributional impact of increased tobacco taxes in Armenia. Health Systems & Reform 2018;4:30–41. 10.1080/23288604.2017.1413494 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), World Health Organization . IARC Handbook of cancer prevention, volume 14: effectiveness of tax and price policies for tobacco control, chapter 7: tax, price and tobacco use among the poor. Lyon: World Health Organization, 2011: pp.259–296. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chaloupka FJ, T-w H, Warner KE, et al. The taxation of tobacco products. : Jha P, Chaloupka FJ, . Tobacco control in developing countries. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2000: 237–72. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arunatilake N, Opatha M. The economics of tobacco control in Sri Lanka. HNP discussion paper, economics of tobacco control paper No.12. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Borren P, Sutton M. Are increases in cigarette taxation regressive? Health Econ 1992;1:245–53. 10.1002/hec.4730010406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Colman GJ, Remler DK. Vertical equity consequences of very high cigarette tax increases: if the poor are the ones smoking, how could cigarette tax increases be progressive? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 2008;27:376–400. 10.1002/pam.20329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Farrelly MC, Nonnemaker JM, Watson KA. The consequences of high cigarette excise taxes for low-income smokers. PLoS One 2012;7:e43838. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gruber J, Sen A, Stabile M. Estimating price elasticities when there is smuggling: the sensitivity of smoking to price in Canada. J Health Econ 2003;22:821–42. 10.1016/S0167-6296(03)00058-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Townsend J, Roderick P, Cooper J. Cigarette smoking by socioeconomic group, sex, and age: effects of price, income, and health publicity. BMJ 1994;309:923–7. 10.1136/bmj.309.6959.923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Response to increases in cigarette prices by race/ethnicity, income, and age groups--United States, 1976-1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1998;47:605–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Siahpush M, Wakefield MA, Spittal MJ, et al. Taxation reduces social disparities in adult smoking prevalence. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:285–91. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Van Walbeek CP. The Distributional Impact of Tobacco Excise Increases*(1). South African J Economics 2002;70:258–67. 10.1111/j.1813-6982.2002.tb01304.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. John RM. Price elasticity estimates for tobacco products in India. Health Policy Plan 2008;23:200–9. 10.1093/heapol/czn007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tabuchi T, Fujiwara T, Shinozaki T. Tobacco price increase and smoking behaviour changes in various subgroups: a nationwide longitudinal 7-year follow-up study among a middle-aged Japanese population. Tob Control 2017;26:69–77. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fuchs A, Meneses FJ. Tobacco price elasticity and Tax progressivity in Moldova. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Choi SE. Are lower income smokers more price sensitive?: the evidence from Korean cigarette tax increases. Tob Control 2016;25:141–6. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Önder Z, Yürekli AA. Who pays the most cigarette tax in Turkey. Tob Control 2016;25:39–45. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), World Health Organization . IARC Handbook of cancer prevention, volume 14: effectiveness of Tax and price policies for tobacco control, chapter 6: Tax, price and tobacco use among young people. Lyon: World Health Organization, 2011: pp.201–258. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kostova D, Ross H, Blecher E, et al. Is youth smoking responsive to cigarette prices? Evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Tob Control 2011;20:419–24. 10.1136/tc.2010.038786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Casetta B, Videla AJ, Bardach A, et al. Association between cigarette smoking prevalence and income level: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res 2017;19:1401–7. 10.1093/ntr/ntw266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hosseinpoor AR, Parker LA, Tursan d'Espaignet E, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in smoking in low-income and middle-income countries: results from the World Health Survey. PLoS One 2012;7:e42843. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sreeramareddy CT, Pradhan PM, Sin S. Prevalence, distribution, and social determinants of tobacco use in 30 sub-Saharan African countries. BMC Med 2014;12:243. 10.1186/s12916-014-0243-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), World Health Organization . IARC Handbook of cancer prevention, volume 14: effectiveness of Tax and price policies for tobacco control, chapter 4: Tax, price and aggregate demand for tobacco products. Lyon: World Health Organization, 2011: 91–136. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Guindon GE, Paraje GR, Chaloupka FJ. The impact of prices and taxes on the use of tobacco products in Latin America and the Caribbean. Am J Public Health 2015;105:e9–19. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hu T-W, Mao Z, Shi J, et al. The role of taxation in tobacco control and its potential economic impact in China. Tob Control 2010;19:58–64. 10.1136/tc.2009.031799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sarntisart I. The economics of tobacco in Thailand. HNP discussion paper, economics of tobacco control paper No.15. Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Adioetomo M, Djutaharta T. Cigarette consumption, taxation and household income: Indonesia case study. HNP discussion paper series, economics of tobacco control paper No. 26. Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nikaj S, Chaloupka FJ. The effect of prices on cigarette use among youths in the global youth tobacco survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16:S16–23. 10.1093/ntr/ntt019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kaestner R, Callison K. An assessment of the forward-looking hypothesis of the demand for cigarettes. South Econ J 2018;85:48–70. 10.1002/soej.12284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lopez AD, Collishaw NE, Piha T. A descriptive model of the cigarette epidemic in developed countries. Tob Control 1994;3:242–7. 10.1136/tc.3.3.242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gravely S, Giovino GA, Craig L, et al. Implementation of key demand-reduction measures of the WHO framework convention on tobacco control and change in smoking prevalence in 126 countries: an association study. Lancet Public Health 2017;2:e166–74. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30045-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jha P, MacLennan M, Palipudi K, et al. Global hazards of tobacco and benefits of cessation. : Gelband H, Jha P, Sankaranarayanan R, et al., . Cancer: disease control priorities. 3rd edn (volume 3). Washington, DC: World Bank, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 60. World Health Organization, Tobacco Free Initiative . Tobacco control profiles - countries, territories and areas. Available: https://www.who.int/tobacco/surveillance/policy/country_profile/en/#P

- 61. World Bank . World development indicators database. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD?view=chart

- 62. Yeh C-Y, Schafferer C, Lee J-M, et al. The effects of a rise in cigarette price on cigarette consumption, tobacco taxation revenues, and of smoking-related deaths in 28 EU countries-- applying threshold regression modelling. BMC Public Health 2017;17:676. 10.1186/s12889-017-4685-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. World Health Organization . WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2019 (table 9.1). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Quimbo SLA, Casorla AA, Miguel-Baquilod M, et al. The economics of tobacco and tobacco taxation in the Philippines. Paris: International Union against tuberculosis and lung disease, 2012. Available: https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/global/pdfs/en/Philippines_tobacco_taxes_annex_en.pdf

- 65. Sayginsoy O, Yurekli AA, de Beye J. Cigarette demand, taxation & the poor: A case study of Bulgaria. HNP Discussion Paper, Economics of Tobacco Control, Paper 4. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2002. Available: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/13629/multi0page.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

tobaccocontrol-2019-055315supp001.pdf (274KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.