Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To characterize objective and subjective elements of the personal lives of diplomates of the American College of Veterinary Surgeons (ACVS) and identify elements of personal life associated with professional life or career success.

SAMPLE

836 ACVS diplomates.

PROCEDURES

An 81-item questionnaire was sent to 1,450 diplomates in 2015 via email and conducted by means of an online platform. Responses were analyzed to summarize trends and identify associations among selected variables.

RESULTS

Men were more likely than women to be married or in a domestic partnership (88% vs 68%, respectively) and to have children (77% vs 47%). Among women but not men, respondents in large animal practice were less likely than those in small animal practice to be represented in these categories. Women had children later in their career than men and indicated that their stage of training played an important role in family planning. Respondents with children worked significantly fewer hours than those without children, with a greater reduction in hours for women versus men (6.0 vs 3.1 hours, respectively). Women were more likely to require external childcare services than men. Women were more likely to report that having children had negatively impacted their professional lives. No negative associations between measures of professional success (eg, advancement or personal income) and parenthood were identified.

CONCLUSIONS AND CLINICAL RELEVANCE

Family demographics differed between male and female ACVS diplomates, yet no objective impact on career success was identified. Work-life balance may play an important role in recruitment, retention, and job satisfaction of veterinary surgeons.

A career in veterinary surgery can be demanding. Although the potential exists for substantial financial compensation, results of a recent survey of ACVS diplomates indicate that surgeons generally work more (in some situations, substantially more) than a traditional 40-hour work week, spend an average of 1 to 2 weeks on-call per month,1 and may also be subject to additional institutional expectations for research, teaching, and public speaking. These demands and others can make it challenging to find a balance between one’s professional career and one’s responsibilities outside of work. Achieving such balance may be even more challenging for professionals who wish to have children and who must consider financial implications, timing of childbirth and family leave, and division of labor at home.

In the United States, women with masters, PhD, or other postgraduate degrees are significantly less likely to have children than those without such advanced degrees.2–5 The mean age at which American women begin having children is approximately 26 years,6 which coincides with the most active years of professional training (veterinary school, internship, and/or residency) for most veterinary surgeons.22 However, older age in women is associated with decreased fertility and increased complications during pregnancy,7–10 and women surgical professionals specifically have lower fertility rates and higher pregnancy complication rates than the general population.5,11–13 In a dual-income household, these issues are of considerable concern to both income earners.

In many ways, the social changes triggered by the feminist movement of the 1960s and 70s are largely incomplete, as evidenced by the lingering income and advancement gap between men and women in various professional realms.14–16 Ample data demonstrate underrepresentation of women in certain surgical subspecialties in human medicine.15,17,18 In a study17 in which women who left their surgical training program were interviewed, many responded that it was too difficult to balance the clinical workload with starting a family. Furthermore, despite the legislative and societal changes of the past 5 decades, women are still more likely than men to serve as primary caregiver for children, even when they are also the primary income earner for the family.19–21

The reciprocal effects of pursuing a career as a veterinary surgeon and maintaining a rich personal life, particularly as it relates to family, have not previously been explored to our knowledge. The purpose of the study reported here was to examine the interface between career and family life in veterinary surgery, focusing on relationship status, family structure, timing and number of children, and other factors likely to affect work-life balance among ACVS diplomates with and without children. Another objective was to investigate whether having children had an objective or perceived impact on career success, and conversely, whether a career in veterinary surgery had an objective or perceived impact on family life. We believed the findings would be informative for veterinary students considering surgical specialization, particularly those who desire to have or raise children. We also anticipated such data would be useful for academic institutions and private specialty hospitals wishing to create an environment that is more conducive to successful integration of career and family life.

Materials and Methods

Study population

The study population comprised all ACVS diplomates who were in good standing as of February 2015 and for whom email addresses could be obtained from the ACVS diplomate directory, via publicly accessible websites (ie, websites for practices or universities), or through personal contact (n = 1,450). The Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin-Madison waived formal review of the protocol owing to the nature of the study in accordance with federal regulation 45 CFR 46.102(d).

Survey

An 81-item questionnaire was designed to elicit objective data about the respondent’s demographics, professional information, compensation, and personal and family information. Details of the survey content and method of administration are described elsewhere.1 Relevant to the present study, respondents were asked to share subjective information about their perceptions of their own career advancement, factors impacting their sense of career fulfillment, and the perceived effects of gender and family life on career success and vice versa. Both objective data (eg, marital status, children, childcare arrangements, and age at first child) and subjective data (perceptions, personal experiences, and professional or personal decision-making) were used.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by use of statistical software.a Response counts and percentages (for nonmissing responses) were calculated. For responses involving numeric data categories (eg, age or number of hours worked per week), category midpoints were used and treated as continuous values for analysis. For comparisons involving categorical responses, the χ2 test, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for adjustment by a single categorical covariate, or logistic regression for adjustment by single continuous covariates or multiple covariates was used. For comparisons involving numeric responses (including category midpoints for numeric data categories), linear regression models were used. For analyses involving how much time respondents with children took off from work for parental leave, if a respondent reported > 1 instance of parental leave owing to multiple children, the maximum total time taken for 1 leave period was used for analysis.

Smoothed estimates of the percentages of respondents having children as a function of the year that diplomate status was achieved (ie, diplomate year) were fit with a generalized linear (logistic) model in which a B-spline basis was used for diplomate year and gender was entered as a main effect; separate models were fit for ≥ 1 and ≥ 2 children. For personal income, for which the maximum possible response was $300,000 (resulting in right censoring of responses), regression models with adjustments for covariates were fit by means of parametric survival analysis with a Weibull distribution assumption. Single imputation of covariates (involving medians for numeric values and medians of category midpoints for numeric data categories) was used when respondents were missing values for numeric variables. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant for all analyses.

Results

Respondents

Of the 1,450 ACVS diplomates invited to participate, 836 (58%) completed the survey via the online platform. Personal and professional demographics of these respondents are reported elsewhere1 and were considered representative of the target population.

Marital status and spousal information

Overall, 79% (621/783) of respondents reported that they were married or in a domestic partnership at the time of the survey, 14% (107/783) were single, 5% (43/783) were divorced, 1% (8/783) were widowed, and < 1% (4/783) were separated. Significant (P < 0.001, after adjustment for age) differences were identified in relationship status by gender, with those who identified as men more likely than those who identified as women to be married or in a domestic partnership (88% [365/416] vs 68% [200/294], respectively), and women more likely than men to be single and never previously married (24% [71/294] vs 6% [27/416]). Men were significantly (P = 0.002) more likely than women to report that their spouse or partner was also a veterinarian (45% [170/382] vs 35% [76/217], respectively). The proportion of men who were (ever) married or in a domestic partnership did not differ significantly (P = 0.87) between those practicing large animal (including equine) surgery versus small animal surgery (94% [136/145] and 93% [252/270], respectively); however, women in small animal surgery were significantly (P = 0.003) more likely to be or have been married or in a domestic partnership than women in large animal surgery (81% [156/192] vs 66% [67/102]). There were no differences in the prevalence of marriage or domestic partnerships between respondents in academia and those in private practice for either gender (Table 1).

Table 1—

Proportion (%) of ACVS diplomates who responded to a survey regarding career-life balance and indicated they were (ever) married or in a domestic partnership (n = 710) or had ≥ 1 child (709).

| Married or domestic partnership | ≥ 1 child | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practice type | Species | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Any | Large animal | 136/145(94) | 67/102 (66) | 110/146 (75) | 35/101 (35) | |

| Small animal | 252/270 (93) | 156/192 (81) | 209/271 (77) | 101/190 (53) | ||

| Overall | 389/416 (94) | 223/294 (76) | 320/418 (77) | 136/291 (47) | ||

| Academia | Large animal | 64/68 (94) | 39/57 (68) | 49/68 (72) | 18/56 (32) | |

| Small animal | 54/60 (90) | 46/56 (82) | 43/60 (72) | 28/56 (50) | ||

| Overall | 118/128 (92) | 85/113 (75) | 92/128 (72) | 46/112 (41) | ||

| Private practice | Large animal | 67/72 (93) | 22/36 (61) | 56/73 (77) | 12/36 (33) | |

| Small animal | 188/200 (94) | 103/127 (81) | 157/200 (79) | 69/125 (55) | ||

| Overall | 255/272 (94) | 125/163 (77) | 213/273 (78) | 81/161 (50) | ||

Number and timing of children

Overall, 65% (510/781) of respondents reported having children, with a significantly (P < 0.001) higher prevalence of parenthood among men versus women (77% [320/418] vs 47% [136/291], respectively; Figure 1). This difference remained significant after adjustment for age. In particular, among respondents ≥ 36 years of age, 77% (287/371) of men had children, compared with 52% (125/242) of women. Even after adjustment for relationship status, fewer women ≥ 36 years of age who identified themselves as “not single” had children than did men of that same demographic (66% [123/187] vs 82% [284/348], respectively; P = 0.01). Among women, large animal surgeons were less likely to have children than small animal surgeons (35% [35/101] vs 53% [101/190], respectively; P = 0.003). This difference was not observed among men (75% [110/146] vs 77% [209/271], respectively; P = 0.68; Table 1).

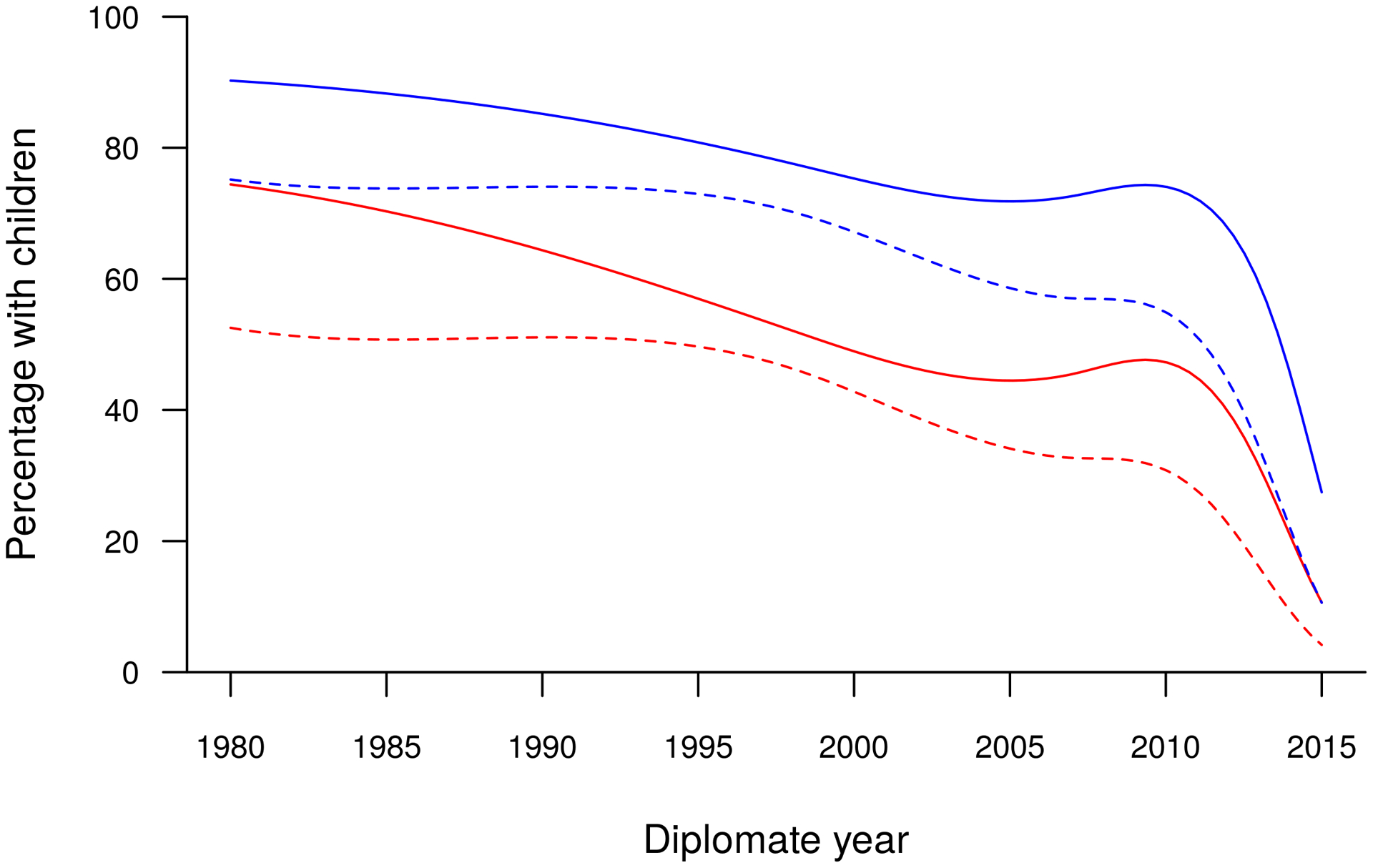

Figure 1—

Smoothed estimates for the percentage of male (blue; n = 416) and female (red; 289) ACVS diplomates who responded to a survey regarding career-life balance and indicated that they had children, by year of diplomate status achievement. Solid lines represent those with ≥ 1 child, and dashed lines represent those with ≥ 2 children.

Among respondents who reported having children, the mean number of children was 2.2, with no significant (P = 0.17) difference by gender after adjustment for age. Among those with children, women reported having or adopting their first child at a slightly later mean age than did men (34.6 vs 33.2 years, respectively; P = 0.02).

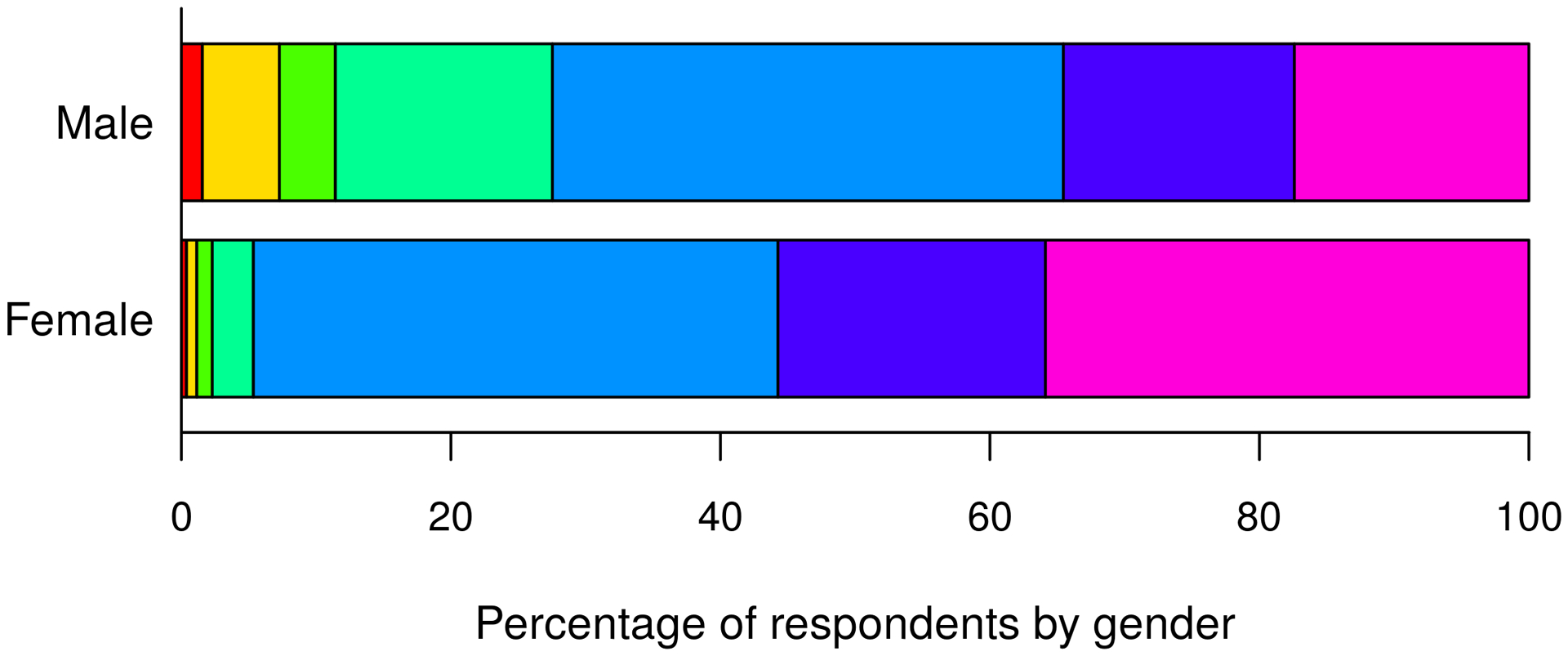

The timing relative to career training of when ACVS diplomates had or adopted children differed significantly (P < 0.001) between men and women, with women having had their first child or planning to have their first child later in their career than men (Figure 2). In particular, more women than men (95% [261/275] vs 74% [290/393], respectively) had or adopted, or planned on having or adopting, their first child after finishing their residency training. After adjustment for diplomate year, men were significantly (P < 0.001) more likely to have children than were women (Figure 1). Of those responding, significantly (P < 0.001) more women than men agreed or strongly agreed that their stage of career (in training vs employment or number of years practicing) played or would play an important role in family planning (68% [199/294] vs 59% [246/418], respectively).

Figure 2—

Strip plots showing the distribution of male (n = 385) and female (262) ACVS diplomates who responded to the question “When during your career did you/do you plan to have or adopt your first child?” Each strip shows the proportions of respondents who planned to have or adopt their first child before (red) or during (yellow) veterinary school, during internship (lime green), during residency (turquoise), or within (blue) or after (purple) the first 5 years of full-time work or had no plans for children (pink).

Employment status

The median category for number of hours worked per week for both men and women was 50 to 59, with no consistent differences by gender across practice types (ie, private practice versus academia) and species (ie, large animal versus small animal); (data reported elsewhere1). Respondents with children worked fewer hours than those without children (P < 0.001), with evidence of a greater reduction for women than men (estimated reduction, 6.0 hours and 3.1 hours, respectively; P = 0.01) after adjustment for age and practice type. In particular, women were more likely to indicate that they worked < 40 h/wk if they had children than were women who did not have children (18% [24/130] vs 7% [11/154], respectively; P = 0.003). Among male respondents, the proportion working < 40 h/wk was not significantly (P = 0.31) different between those with versus without children (13% [41/312] vs 9% [9/97], respectively).

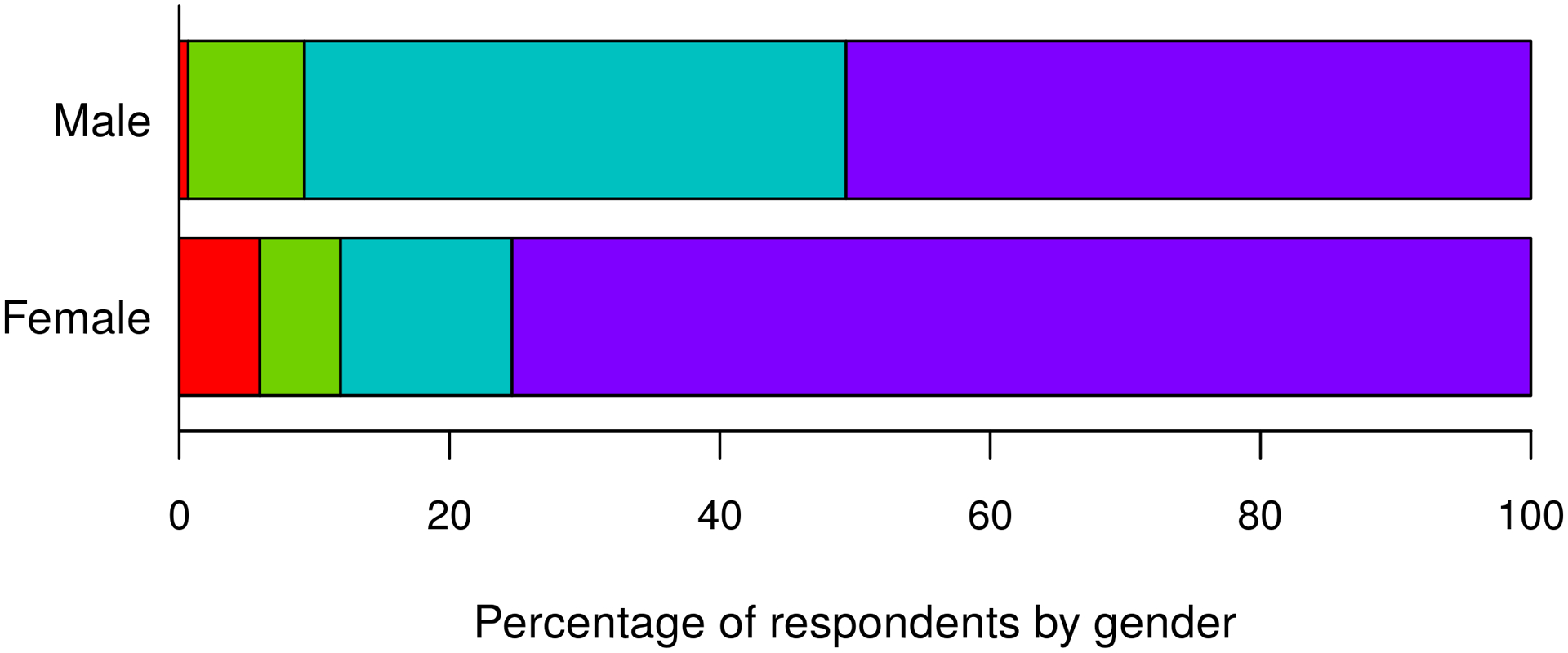

Work flexibility and responsibilities in the home

When asked about flexibility in work schedules, more men than women felt that their significant other had a more flexible schedule (67% [255/382] vs 49% [117/239], respectively; P < 0.001). Among respondents with children, this gap was similar (72% [221/305] vs 53% [68/129], respectively), with more men than women indicating their “significant other” worked from home or stayed at home (31% [95/305] vs 11% [14/129]) or had a job that was part-time or otherwise allowed for “significant time off” (21% [65/305] vs 9% [12/129]). Among respondents without children, 44% (34/77) of men and 44% (48/108) of women felt that their “significant other” had more flexibility in their work schedule (P = 0.97). When asked about provision of child care, more women than men indicated they had required the use of external childcare services (75% [101/134] vs 51% [153/302], respectively), and more men than women indicated their partner or spouse stayed home with the children (40% [121/302] vs 13% [17/134]; P < 0.001 for both comparisons; Figure 3). Among respondents with children, gender differences in responsibility for childcare were also evident outside of normal working hours (P < 0.001), whereby 28% (37/133) of women and 3% (8/300) of men indicated that they were the primary caregiver, and 6% (8/133) of women and 33% (13/300) of men reported that their spouse filled this role. Approximately equal proportions of female and male respondents reported sharing this responsibility equally with their partner (51% [68/133] vs 46% [138/300], respectively).

Figure 3—

Strip plots showing the distribution of male and female ACVS diplomates who responded to the questions “If one or more of your children are under the age of 13, do you require childcare?” (n = 192 and 102, respectively) and “If one or more of your children are older than 13, did you require childcare before they were 13?” (n = 189 and 69, respectively). When respondents answered both questions, the answer from the first question was used in the analysis. Response options included “No, I stay home with them” (red), “My partner and I share this responsibility” (lime green), “No, my partner/spouse stays home with them” (turquoise), and “Yes” (purple).

Women with children took significantly (P < 0.001) more maternal leave than did men (mean, 13.8 weeks vs 2.4 weeks, respectively), and this difference remained significant after adjustment for practice type and species. There was no difference between genders in the use of paid versus unpaid leave by gender (P = 0.91). Among both genders, respondents working in academia were significantly (P < 0.001 for both comparisons) more likely to take paid leave than those working in private practice (91% [100/110] vs 35% [54/154], respectively for women; 88% [105/120] vs 42% [101/239] for men). Self-assessment of adequacy of parental leave did not differ by gender, practice type, or species, with 38% (167/443) of respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing that their parental leave had been adequate and 29% (130/443) disagreeing or strongly disagreeing.

Objective measures of professional success

In an analysis stratified by gender, respondents with children were more likely to be more advanced in their careers (academic rank/title or practice ownership) than were respondents without children; however, this difference was no longer significant (P = 0.29) after adjustment for species, age, and relationship status. Nevertheless, even after adjustment for multiple covariates, including gender, age, diplomate year, practice type, species, employment status, job title, and others, respondents with children reported a higher salary than those without children (mean, 9.6% higher; P = 0.007), with no evidence that this relationship between having children and higher salary differed by gender (P = 0.57).

Subjective measures of the relationship between personal life and a successful career

Overall, 25% (186/754) of respondents reported that their career had positively affected their relationship, and 41% (311/754) reported a negative effect. Women were significantly (P < 0.001 for both comparisons) more likely than men to report a negative effect (50% [141/283] vs 35% [147/415], respectively) and less likely to report a positive effect (16% [45/283] vs 30% [125/415]).

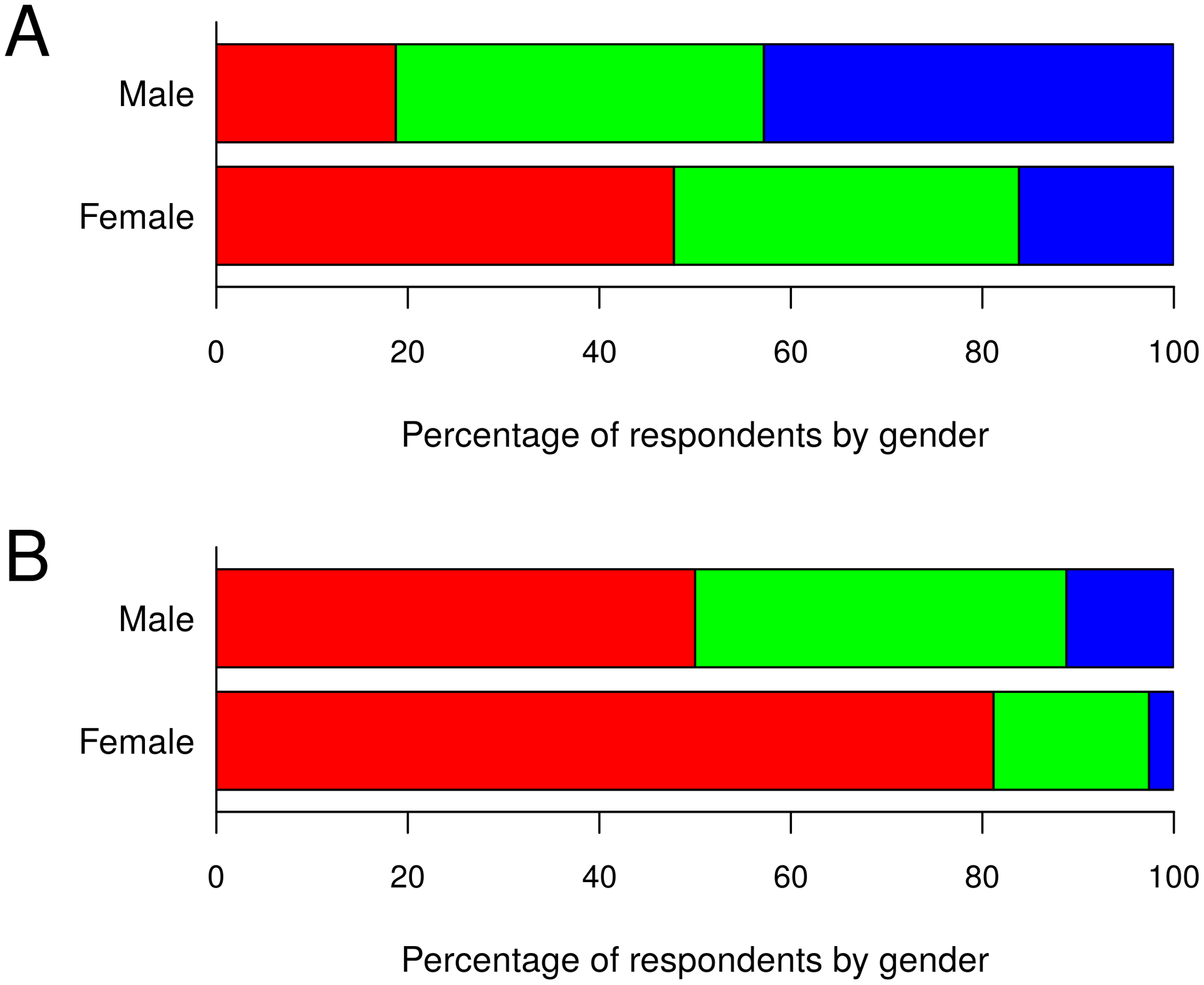

When respondents with children were asked if having children had affected the type of practice or career path they had chosen, significantly (P < 0.001) more women than men indicated it had (51% [70/136] vs 34% [109/319], respectively). In addition, more women than men perceived that family had an overall negative impact on their career development (48% [65/136] vs 19% [60/320], respectively), whereas more men than women perceived a positive impact (43% [137/320] vs 16% [22/136]; P < 0.001). Similarly, when respondents who had not had children (or not had children yet) were asked what sort of impact they believed having children would have had (or would have) on their career path, women were significantly (P < 0.001) more likely to expect a negative impact than men (81% [125/154] vs 50% [49/98], respectively). Overall, a significantly (P < 0.001) greater proportion of respondents without children expected a negative impact of having a family on their career compared with the perceived experiences of those who were already parents (Figure 4).

Figure 4—

Split plots showing the distribution of male and female ACVS diplomates who responded to the question “Do you feel that having a family has had an impact on your career?” (for those with children; n = 320 and 136, respectively) or “Do you feel that having a family will impact/would have impacted your career?” (for those without children; n = 98 and 154, respectively). Response options included “negative” (red), “neutral” (green), and “positive” (blue).

When asked whether maintaining their professional occupation had had a negative impact on their ability to participate in family life, especially with respect to raising children, many respondents (with or without children) agreed (49% [241/487]) or strongly agreed (23% [110/487]), with no significant (P = 0.24) difference identified between genders.

Discussion

In 2017, the proportion of first-year class seats occupied by women in US veterinary schools surpassed 80%.22 This demographic change has been accompanied by a generational shift of priority, given that both male and female millennials believe women are more focused on their careers than men.14 In 2015, nearly half of 2-parent households featured 2 working parents, compared with 31% in 1970,23 and this situation can pose a challenge to achieving work-life balance. In human medicine, incompatibility between work and family life has been identified as a leading cause for physician dissatisfaction, particularly among those who discontinue a career in the clinical or academic sector.2,24,25 The results of the study reported here, unsurprisingly, suggested that a similar struggle may exist for ACVS diplomates with the competing devotions of professional and personal lives.

One of the most striking findings of the study reported here was the gender disparity in the proportion of respondents who were married. Men were significantly more likely than women to be married or in a domestic partnership, a difference that was further highlighted within the large animal surgical specialty. A similar pattern has been noted in human surgical disciplines as well.3,4,26,27 The reason underlying this disparity between genders is unclear because there is a longstanding trend for educated women to be more likely to be married than educated men.28 Female ACVS diplomates participating in the survey reported here were significantly more likely than male diplomates to indicate that they perceived their career to have had a negative impact on their personal relationships; this finding offered a possible explanation for our observations. Specifically with respect to large animal surgeons, the time burden (eg, mean number of hours worked and number of on call shifts per month) was greater than that of small animal surgeons,1 and this factor may have contributed to the lower prevalence of marriage for women in large animal surgery in the present study.

We also found dramatic differences in the prevalence of parenthood between male and female respondents, independent of relationship status and age. Similar findings have been reported in human surgical fields and among women with PhDs or other postgraduate degrees.2–5 Echoing the pattern seen across all human surgical fields,4,26,29–33 most (95%) female ACVS diplomates in the present study began having children in the first 5 years after surgical residency training (vs 74% of male diplomates). This statistic corresponded with a mean age of 34.6 years at the time the first child was born. Although having children after residency training may be considered ideal to avoid a break in career development,30,31,34 advanced maternal age is associated with increased risks to maternal and fetal health during pregnancy.7–10 In addition to advanced age, the physical and emotional stress associated with high-intensity jobs (such as surgery) can adversely impact fertility.4,35–37 Physical stress may be an especially important factor for large animal surgeons and may have contributed to our observations that female diplomates working in large animal surgery were the least likely to have children. Although already demonstrated among human surgeons,5,11–13 evaluation of fertility and pregnancy complications among veterinary surgeons may help to delineate the role these factors play in the gender differences observed in the veterinary surgical profession.

The design of the present study did not allow evaluation of the role of personal choice in the prevalence of marriage and parenthood among ACVS diplomates. While time constraints and biological factors may have affected these outcome measures for specific individuals, our results also likely represented lifestyle choices made by ACVS members. In 2016, the prevalence of marriage among US adults > 18 years old was 50% and among those > 25 years old with a bachelor degree was 65%.38 Our results indicated a perceived negative impact of children on career advancement among respondents, and thus some graduating veterinary students who plan to raise children may opt out of a career in surgery. Studies4,39,40 of physicians in human medicine show that those rejecting a career in surgical specialties are more likely to specify reasons related to quality of life. Because we surveyed only current ACVS diplomates, we could not analyze the population of veterinarians who chose not to pursue a career in surgery or opted to leave this field. The unmeasurable role of personal choice must be considered when interpreting our findings.

Another finding of note in the present study was the pattern of childcare responsibilities among male and female diplomates. With a continued increase in dual-career families in the United States, responsibilities at home have shifted, with both men and women participating in childcare duties.41 Despite this trend, studies26,29 in human medicine show that only 25% to 58% of male physicians with children have a spouse who works outside of the home, whereas 90% of female physicians with children report the same. The results from our survey echoed these findings, whereby more male than female ACVS diplomates indicated that their “significant other” worked from home, stayed at home, or worked part time. Not surprisingly, we also found that more women than men required external childcare services and more men than women indicated that their partner or spouse stayed home with the children. Gender differences in childcare responsibilities were also evident outside working hours, whereby more women than men indicated that they were the primary caregiver. These findings suggested that both the need or desire to provide childcare personally and the need to secure it externally differs between men and women in the profession. In our analysis of other elements of career and personal life evaluated in the survey,1 men were more likely than women to be the primary earners in their household (81% vs 65%, respectively), providing a possible explanation for the observed discrepancy in division of labor.

The subjective opinions of male and female ACVS diplomates about the perceived impact of children on career success also differed significantly in the present study. More women than men believed that having a family had negatively impacted their career development, whereas men were more likely to believe that having a family resulted in a positive impact on their career. Even among those who did not have children, women were significantly more likely to expect a negative impact than men. Although the expectations of diplomates were more likely to be negative than the actual experiences of those with children, 49% of women (vs 19% of men) still believed that they had experienced some negative impact on their career. The aforementioned perceptions likely contributed to more women than men choosing not to have children. This information is important because perception differs from reality and, therefore, mentorship and education can be valuable to new veterinary graduates considering starting families. In this study and others, women have subjectively experienced more difficulty in balancing work and family than men,18,27 so it would be important to address these barriers in the veterinary surgical profession, in which the proportion of women is increasing.

Despite the characterized perceptions, we did not find any measurable difference in career success for ACVS diplomates, men or women, with or without children, in any practice setting or species specialty.1 On the contrary, after adjustment for covariates such as age, years in practice, and relationship status, among others, the prevalence of parenthood was associated with a higher personal income (and no significant differences in level of career advancement) for both men and women. The phenomenon in the US Labor force termed the motherhood penalty was first described in 2001 and indicated that, for each child a woman had, her mean income would decrease by 5% to 7%, depending on years of job experience and social class.42 The opposite effect, termed the fatherhood bonus, indicated an increase in annual income for fathers during the years in which they were having children.42 It was interesting that our study showed no effect of gender on the personal income of diplomates with children. The cause for the income discrepancy between those with and without children could not be determined from the collected data; however, the proportionally greater financial needs of a larger household might be expected to lead to efforts or decisions that would result in greater income.

The present study had several limitations that warrant consideration. As a survey-based study, some response bias would be expected. For example, people who were more passionate about the subject matter may have been more likely to respond than others. Because only current ACVS diplomates were surveyed, we are unable to investigate factors that might influence the decision to pursue a career in veterinary surgery. In a survey27 of female pediatric surgeons, respondents expressed concerns about lifestyle issues imposed by a career in surgery as a barrier to their overall quality of life and suggested that these concerns are likely to influence individuals considering the career path. In addition, workload and lifestyle of surgical residents are reportedly deterrents for fourth-year medical students from pursuing a surgical career.43 Overall, lack of female mentors, difficulties related to childbearing and childcare, and workload and lifestyle issues, have all been implicated as possible disincentives to a career in human surgery.27,29,41,43 A more complete picture would be captured through longitudinal evaluation of veterinary students in their final year to determine not only what the deterrents might be in veterinary medicine but also how those deterrents might affect the changing generational and gender demographic of new veterinarians. Finally, although questions were included in the survey to characterize family structure as it related to partnership and having children and responses were considered in depth, other responsibilities such as care of special-needs family members and other relationships of a personal nature were not specifically defined and investigated. Ongoing efforts to consider the broader elements of life as veterinary surgical professionals will help to identify a wider variety of issues and needs.

To achieve career-life integration and overall satisfaction, it seems likely that change is needed so that veterinary surgeons, both men and women, can be more involved in their personal lives and families without a detrimental effect on their career. Methods to achieve this in human medical fields include part-time and fixed-time schedules, flexible tenure programs for part-time faculty, and set parental leave packages for both men and women.41 Although initially met with criticism, reduced working hours for physicians with children has been associated with stronger family relationships, greater achievement of professional goals, and greater overall career satisfaction.2,44 In veterinary medicine, importance is placed on the training years, including veterinary school and residency, leaving many veterinary surgeons to balance starting a family with developing themselves professionally during the early stages of their surgical career. Arguably, the first 5 years of practice as a veterinary surgeon is important for gaining competence, establishing a caseload, and launching a successful research or teaching program, among other things. Modernizing career development programs, work schedules, and employment benefits to accommodate professional and family obligations will allow veterinary surgery to continue to be an attractive and competitive career choice for men and women alike.

In conclusion, both male and female ACVS diplomates in the present study experienced some difficulty in balancing a demanding career with a satisfying personal and family life, and women appeared to experience more difficulty with this process. Parenthood was not shown to have a negative association with elements of career success by any quantitative metric. What was apparent, in both the present study and the companion study,1 was that the personal lives and the professional success of men and women in veterinary surgery were not identical. Whether owing to implicit bias, explicit bias, personal choices, or other motivations or constraints, female diplomates constituted a different professional workforce than male diplomates did, and this difference may be likely to be augmented by generational differences as well. Understanding and accounting for these differences may be a valuable, if not critical, exercise as the demographics of the veterinary surgical workforce shift toward greater proportions of women diplomates and diplomates of a newer generation.

Acknowledgments

Statistical analysis was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR002373. No other funding or support was received in connection with this study or the writing or publication of the manuscript. The authors declare that there were no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

R: A language and environment for statistical computing, version 3.3.3. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available at: www.R-project.org. Accessed April, 2017.

References

- 1.Morello S, Colopy SA, Brucker K, et al. Specialty demographics and measures of professional achievement for American College of Veterinary Surgeons diplomates in 2015. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2019;XX:XX–XX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckett L, Nettiksimmons J, Howell LP, et al. Do family responsibilities and a clinical versus research faculty position affect satisfaction with career and work-life balance for medical school faculty? J Womens Health 2015;24:471–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Troppmann KM, Palis BE, Goodnight JE Jr, et al. Women surgeons in the new millennium. Arch Surg 2009;144:635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halperin TJ, Werler MM, Mulliken JB. Gender differences in the professional and private lives of plastic surgeons. Ann Plastic Surg 2010;64:775–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips EA, Nimeh T, Braga J, et al. Does a surgical career affect a woman’s childbearing and fertility? A report on pregnancy and fertility trends among female surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 2014;219:944–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. Mean age of mothers is on the rise: United States, 2000–2015. NCHS Data Brief 2016;232. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db232.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobsson B, Ladfors L, Milsom I. Advanced maternal age and adverse perinatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104:727–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauria L, Ballard TJ, Caldora M, et al. Reproductive disorders and pregnancy outcomes among female flight attendants. Aviat Space Environ Med 2006;77:533–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbert WM, Nesbitt TS, Danielsen B. Childbearing beyond age 40: pregnancy outcome in 24,032 cases. Obstet Gynecol 1999;93:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cleary-Goldman J, Malone FD, Vidaver J, et al. Impact of maternal age on obstetric outcome. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:983–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stentz NC, Griffith KA, Perkins E, et al. Fertility and childbearing among American female physicians. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2016;25:1059–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton AR, Tyson MD, Braga JA, et al. Childbearing and pregnancy characteristics of female orthopaedic surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94:e77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lerner LB, Stolzmann KL, Gulla VD. Birth trends and pregnancy complications among women urologists. J Am Coll Surg 2009;208:293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pew Research Center. The narrowing of the gender wage gap, 1980–2012. Available at: www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/12/11/on-pay-gap-millennial-women-near-parity-for-now/sdt-gender-and-work-12-2013-0-02. Accessed May 7, 2018.

- 15.Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1294–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.West M, Curtis JW. AAUP Faculty gender equity indicators 2006. Available at: www.aaup.org/NR/rdonlyres/63396944-44BE-4ABA-9815-5792D93856F1/0/AAUPGenderEquityIndicators2006.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2017.

- 17.Gjerberg E. Gender similarities in doctors’ preferences—and gender differences in final specialization. Soc Sci Med 2002; 54:591–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gjerberg E. Women doctors in Norway: the challenging balance between career and family life. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:1327–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jovic E, Wallace JE, Lemaire J. The generation and gender shifts in medicine: an exploratory survey of internal medicine physicians. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ergeneli A Ilsev A, Karapinar PB. Work-family conflict and job satisfaction relationship: the roles of gender and interpretive habits. Gend Work Organ 2010;17:679–695. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carnes M Morrissey C, Geller SE. Women’s health and women’s leadership in academic medicine: hitting the same glass ceiling? J Womens Health 2008;17:1453–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges. Annual data report 2016–2017. Available at: www.aavmc.org/About-AAVMC/Public-Data.aspx. Accessed May 7, 2018.

- 23.Pew Research Center. Raising kids and running a household: how working parents share the load. Available at: www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/11/04/raising-kids-and-running-a-household-how-working-parents-share-the-load. Accessed May 7, 2018.

- 24.Mache S, Bernburg M, Vitzthum K, et al. Managing work-family conflict in the medical profession: working conditions and individual resources as related factors. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schroen AT, Brownstein MR, Sheldon GF. Women in academic general surgery. Acad Med 2004;79:310–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pana AL, McShane J. Gender influences on career opportunities, practice choices, and job satisfaction in a cohort of physicians with certification in sports medicine. Clin J Sports Med 2001;11:96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caniano DA, Sonnino RE, Paolo AM. Keys to career satisfaction: insights from a survey of women pediatric surgeons. J Pediatr Surg 2004;39:984–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reeves RV, Krause E. Why are you, educated men working less? Available at: www.brookings.edu/blog/social-mobility-memos/2018/02/23/why-are-young-educated-men-working-less. Accessed May 7, 2019.

- 29.Zutshi M, Hammel J, Hull T. Colorectal surgeons: differences in perceptions of a career. J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:830–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dresler CM, Padgett DL, MacKinnon SE, et al. Experiences of women in cardiothoracic surgery. A gender comparison. Arch Surg 1996;131:1128–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith NP, Dykes EH, Youngson GS, et al. Is the grass greener: a survey of female pediatric surgeons in the United Kingdom. J Pediatr Surg 2006;41:1879–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willett LL, Wellons MF, Hartig JR, et al. Do women residents delay childbearing due to perceived career threats? Acad Med 2010;85:640–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pham DT, Stephens EH, Antonoff MB, et al. Birth trends and factors affecting childbearing among thoracic surgeons. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;98:890–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sinal S, Weavil P, Camp MG. Survey of women physicians on issues relating to pregnancy during a medical career. J Med Educ 1988;63:531–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eskenazi L, Weston J. The pregnant plastic surgical resident: results of a survey of women plastic surgeons and plastic surgery residency directors. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995;95:330–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dvali L, Brenner MJ, Mackinnon SE. The surgical workforce crisis: rising to the challenge of caring for an aging America. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;113:893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young-Shumate L, Kramer T, Beresin E. Pregnancy during graduate medical training. Acad Med 1993;68:792–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pew Research Center. As US marriage rate hovers at 50%, education gap in marital status widens. Available at: www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/14/as-u-s-marriage-rate-hovers-at-50-education-gap-in-marital-status-widens. Accessed May 7, 2018.

- 39.van der Horst K, Siegrist M, Orlow P, et al. Residents’ reasons for specialty choice: influence of gender, time, patient and career. Med Educ 2010;44:595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lambert TW, Davidson JM, Evans J, et al. Doctors’ reasons for rejecting initial choices of specialties as long-term careers. Med Educ 2003;37:312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown JB, Fluit M, Lent B, et al. Surgical culture in transition: gender matters and generation counts. Can J Surg 2013;56:153–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Budig M, England P. The wage penalty for motherhood. Am Sociol Rev 2001;66:204–225. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cochran A, Melby S, Neumayer LA. An internet-based survey of factors influencing medical student selection of a general surgery career. Am J Surg 2005;189:742–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barnett RC, Gareis KC, Carr PL. Career satisfaction and retention of a sample of women physicians who work reduced hours. J Women Health 2005;14:146–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]