ABSTRACT

Hearing loss affects ∼10% of adults worldwide. Most sensorineural hearing loss is caused by the progressive loss of mechanosensitive hair cells (HCs) in the cochlea. The molecular mechanisms underlying HC maintenance and loss remain poorly understood. LBH, a transcription co-factor implicated in development, is abundantly expressed in outer hair cells (OHCs). We used Lbh-null mice to identify its role in HCs. Surprisingly, Lbh deletion did not affect differentiation and the early development of HCs, as nascent HCs in Lbh knockout mice had normal looking stereocilia. The stereocilia bundle was mechanosensitive and OHCs exhibited the characteristic electromotility. However, Lbh-null mice displayed progressive hearing loss, with stereocilia bundle degeneration and OHC loss as early as postnatal day 12. RNA-seq analysis showed significant gene enrichment of biological processes related to transcriptional regulation, cell cycle, DNA damage/repair and autophagy in Lbh-null OHCs. In addition, Wnt and Notch pathway-related genes were found to be dysregulated in Lbh-deficient OHCs. Our study implicates, for the first time, loss of LBH function in progressive hearing loss, and demonstrates a critical requirement of LBH in promoting HC survival in adult mice.

KEY WORDS: Hair cells, Hearing loss, LBH, Mechanotransduction, RNA-seq, Stereocilia

Summary: Loss of function of transcription co-factor LBH caused progressive hair cell loss in adult mice, likely mediated by dysregulation of genes promoting hair cell survival and DNA repair.

INTRODUCTION

There are 466 million people worldwide living with hearing loss, according to World Health Organization estimates (https://www.who.int/deafness/estimates/en/). Most sensorineural hearing loss is caused by progressive degeneration of hair cells (HCs) in the cochlea of the inner ear. These cells are specialized mechanoreceptors that transduce mechanical forces transmitted by sound to electrical activities (Hudspeth, 2014; Fettiplace, 2017). HCs in adult mammals are terminally differentiated and unable to regenerate once they are lost due to aging or exposure to noise and ototoxic drugs. Although HCs have been well characterized morphologically and biophysically, the key molecules that control their differentiation, homeostasis and aging remain to be identified.

Inner and outer HCs (IHCs and OHCs) are the two types of HCs, with distinct morphologies and functions in the mammalian cochlea (Dallos, 1992). IHCs are the true sensory receptor cells and transmit information to the brain, whereas the OHCs are a mammalian innovation with a unique capability of changing their length in response to changes in receptor potential (Brownell et al., 1985). OHC motility is believed to confer the mammalian cochlea with high sensitivity and exquisite frequency selectivity (Liberman et al., 2002; Dallos et al., 2008). We compared cell type-specific transcriptomes of IHC and OHC populations from adult mouse cochleae to identify genes commonly and differentially expressed in these two types of HCs (Liu et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018). Our analysis showed that Limb-bud-and-heart (Lbh), a transcription co-factor implicated in development (Briegel and Joyner, 2001; Briegel et al., 2005), is expressed in adult IHCs and OHCs. Lbh is also expressed in cochlear and vestibular HCs and weakly expressed in some supporting cells (SCs) between embryonic day (E)16 and postnatal day (P)7 (Scheffer et al., 2015; Elkon et al., 2015; Cai et al., 2015; Ranum et al., 2019; Kolla et al., 2020). Furthermore, Lbh expression is upregulated during transdifferentiation of SCs to HCs (Ebeid et al., 2017; Yamashita et al., 2018). Transcription factors are proteins that bind to specific DNA motifs to regulate the expression of target genes, whereas transcription co-factors interact with transcription factors to activate or repress the transcription of specific genes. As LBH is a transcription co-factor, we investigated whether LBH is necessary for regulating HC differentiation, development and maintenance. Because Lbh is differentially expressed in nascent and adult OHCs (Li et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Ranum et al., 2019; Kolla et al., 2020), we also investigated whether LBH plays a role in regulating cell specialization underlying OHC morphology and function.

Lbh knockout mice (hereafter referred to as Lbh−/− or Lbh-null mice) have been generated by crossing conditional Lbhflox mice with a Rosa26-Cre line, resulting in an ubiquitous germline deletion of Lbh and the abolishment of LBH protein expression during embryonic development (Lindley and Briegel, 2013). In this study, we examined the role of LBH in HCs by comparing changes in morphology, function and gene expression between HCs from Lbh-null mice and their wild-type littermates. Results showed that HC differentiation, maturation of mechanotransduction and OHC specialization were unaffected by the loss of LBH. However, stereocilia bundles and HCs, especially OHCs, showed signs of degeneration as early as P12. Moreover, adult Lbh-null mice displayed progressive loss of hearing and otoacoustic emissions, suggesting that LBH is critical for the survival of HCs. Cell-specific transcriptome and bioinformatics analyses showed a significant enrichment of genes associated with transcription, cell cycle, DNA damage/repair and autophagy in the Lbh-null OHCs. Wnt and Notch pathway-related genes, known for their important roles in regulating HC differentiation and regeneration in vertebrate HCs (Raft and Groves, 2015; Waqas et al., 2016), were found to be dysregulated. Our study implicates, for the first time, the loss of transcription co-factor LBH function in progressive hearing loss, and demonstrates a critical requirement of LBH in promoting cochlear HC survival.

RESULTS

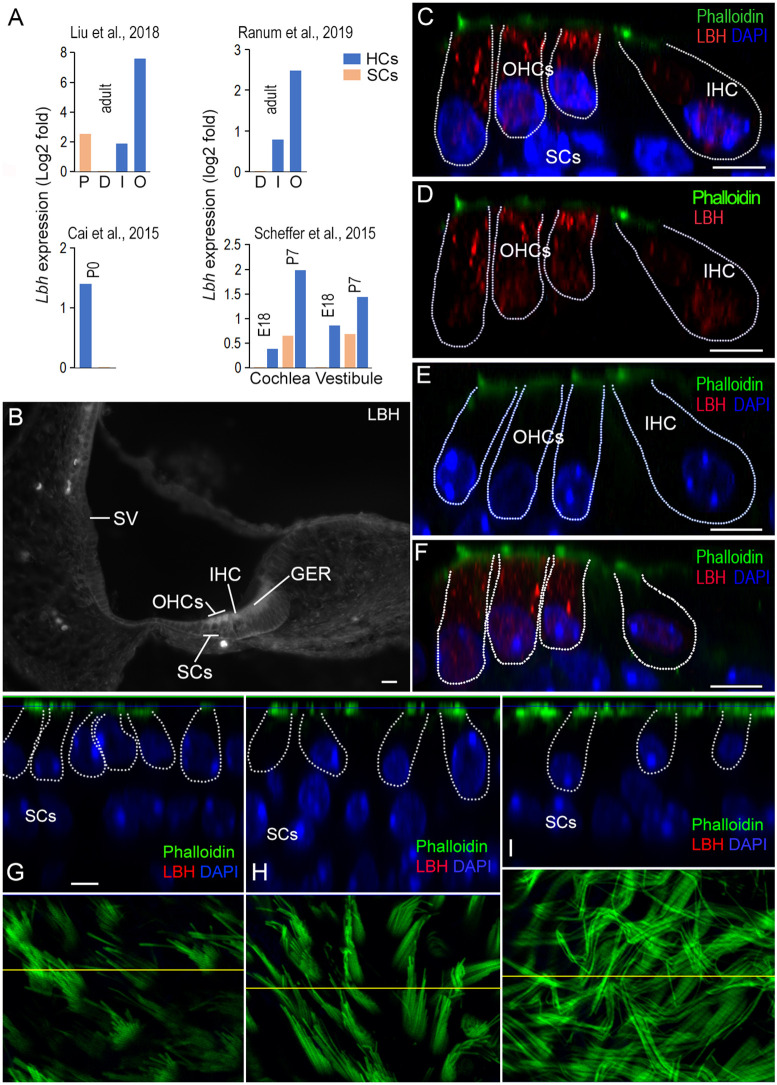

LBH mRNA and protein are highly expressed in cochlear HCs

Lbh gene expression in HCs and SCs in the adult murine organ of Corti was examined using our published cell type-specific RNA-seq data sets (Liu et al., 2018). This analysis showed that Lbh mRNA was expressed in all four cell types of the adult cochlea, IHCs, OHCs, pillar cells and Deiters’ cells; however, Lbh transcript levels were highest in OHCs (Fig. 1A, top left panel). This pattern of expression is consistent with single-cell RNA-seq data (Ranum et al., 2019; Kolla et al., 2020). We also examined Lbh expression during development using bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data sets from published studies (Scheffer et al., 2015; Elkon et al., 2015; Cai et al., 2015; Ranum et al., 2019; Kolla et al., 2020). As shown in Fig. 1A (bottom panels), Lbh was abundantly expressed in cochlear and vestibular HCs at E16 and upregulated at P7. In contrast, Lbh levels remained low in SCs compared to HCs (Fig. 1A, bottom panels). Taken together, these studies show that Lbh expression is substantially higher in HCs than in SCs during development and in adulthood.

Fig. 1.

Expression of LBH in cochlear and vestibular HCs. (A) Cell type-specific expression of Lbh mRNA in HCs and SCs from four published RNA-seq data sets. The expression RPKM value of SCs was used as reference. D, Deiters’ cells; P, pillar cells; I, IHCs; O, OHCs. (B) Fluorescent microscopy picture of antibody staining of LBH protein in a cryosection of the cochlea from a P3 wild-type mouse. The stria vascularis (SV), IHCs, OHCs and greater epithelium ridge (GER) are marked. (C,D) LBH expression (red) in the organ of Corti from a P12 wild-type mouse using confocal optical sectioning with (C) and without DAPI (D). LBH expression was observed in the cytosol and nuclei of IHCs and OHCs. (E) Lack of LBH protein expression in hair cells in a P12 Lbh-null mouse. (F) LBH expression in P30 cochlear HCs from wild-type mouse. (G-I) Optical section of the saccule, utricle and crista from an adult wild-type mouse. The HCs are outlined and nuclei of SCs are indicated. Phalloidin staining of stereocilia bundles of HCs in the saccule, utricle and crista are presented in the bottom panels. The yellow lines in each panel indicate where the optical section was made. Scale bars: 10 µm (B); 5 µm (C-I).

We next used LBH-specific antibodies to examine LBH protein expression in inner ears from neonatal and adult C57BL/6 mice. Fig. 1B shows a micrograph obtained from a cryosection of a P3 cochlea. LBH was expressed in both OHCs and IHCs, with no obvious expression in SCs (Fig. 1B). LBH positivity was also detected in some cells in the greater epithelial ridge at this stage. In P12 cochlea, LBH was still expressed in both IHCs and OHCs; however, expression was stronger in OHCs (Fig. 1C). Of note, LBH was predominately cytoplasmic, although weaker expression was also seen in the nuclei (Fig. 1C,D). In the age-matched Lbh-null mice, no LBH protein was detected in IHCs and OHCs (Fig. 1E), confirming specificity of LBH expression in these cells, as well as deletion of LBH function in these mice (Lindley and Briegel, 2013). Robust LBH expression persisted in adult OHCs, whereas LBH expression in IHCs remained weak (Fig. 1F). This pattern of expression is consistent with the predominant expression of Lbh mRNA in adult OHCs (Liu et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Ranum et al., 2019; Kolla et al., 2020). Interestingly, no LBH immunopositivity was detected in HCs of saccule, utricle and crista in the vestibular end organs in neonatal and adult mice (Fig. 1G-I). Thus, LBH appears to be only expressed in cochlear HCs.

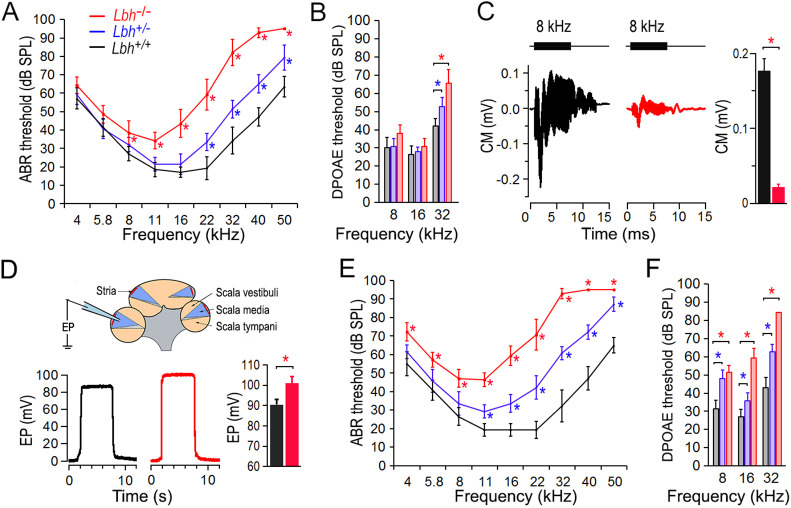

Auditory function of Lbh-mutant mice indicates progressive hearing loss

To determine whether LBH expression in cochlear HCs is required for hearing, we examined auditory function in Lbh-null mice by measuring auditory brainstem response (ABR). In Lbh-null mice (mixed 129/SvEv and C57BL/6 background), Lbh was ubiquitously deleted during embryonic development, and the absence of LBH protein expression was validated by western blot and negative LBH antibody staining in mammary glands (Lindley and Briegel, 2013). Lack of LBH expression in HCs of Lbh-null mice is presented in Fig. 1D. Fig. 2A shows the ABR thresholds of homozygous (Lbh−/−), heterozygous (Lbh+/−) and wild-type (Lbh+/+) mice at 1 month of age. As shown, the threshold of Lbh−/− mice was elevated by ∼10 dB at lower frequencies to ∼40 dB in higher frequencies relative to their wild-type littermates. The ABR thresholds of Lbh−/− mice at 8 kHz and above were significantly elevated compared to Lbh+/+ mice. Heterozygous Lbh+/− mice also showed 10 to 25 dB hearing loss at higher frequencies when compared with the wild-type controls. The significant elevation of ABR thresholds between Lbh+/− and Lbh+/+ mice at 22 kHz and above, suggests that a single functional allele is insufficient to retain normal hearing function. We next measured distortion product otoacoustic emission (DPOAE) thresholds at 8, 16 and 32 kHz in these mice. DPOAEs are generated by motor activity of OHCs (Liberman et al., 2002; Dallos et al., 2008) and reflect OHC function and condition. Similar to ABR thresholds, DPOAE thresholds (Fig. 2B) were also elevated at 32 kHz in Lbh−/− and Lbh+/− mice. We further measured cochlear microphonic (CM) in response to an 8 kHz tone burst in Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ mice. The CM is a receptor potential believed to be generated primarily by OHCs (Dallos, 1992). A significant reduction of the CM magnitude was observed in Lbh−/− mice (P=4.29×10−6, n=6) (Fig. 2C). As weak expression of Lbh was detected in the intermediate cells of the stria vascularis during development (Liu et al., 2018), we measured endocochlear potential (EP) in 1-month-old Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ mice to determine whether stria development and function are affected by the deletion of Lbh. This is necessary as stria function (i.e. EP) can influence HC survival (Liu et al., 2016). The mean magnitude of EP was 100.6±2.3 mV for Lbh−/− and 90.5±2.6 mV for Lbh+/+ mice (Fig. 2D; P=2.92×10−4, n=6). This increase is likely due to loss of HCs, which diminished the leaky transduction current and increased the resistance between the scala media and scala tympani, leading to an increase in EP (Zhang et al., 2014). The fact that no EP reduction was observed suggests that loss of LBH does not affect stria function. Finally, ABR and DPOAE measurements at 3 months of age showed that the thresholds were further elevated in both Lbh−/− and Lbh+/− mice (Fig. 2E,F), indicating that LBH deficiency causes progressive hearing loss.

Fig. 2.

Auditory function of Lbh-mutant mice. (A) ABR thresholds of Lbh−/−, Lbh+/− and Lbh+/+ mice (color-coded) at 1 month of age. Eight mice for each genotype from three different litters were used. (B) DPOAE thresholds at 1 month (n=7 for each genotype). (C) Representative CM responses obtained from Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ mice. Tone bursts (8 kHz, 80 dB SPL) were used to evoke the response. The mean of peak-to-peak magnitude of the CM was 0.021±0.0035 mV (s.d.) and 0.177±0.015 mV, respectively, for the Lbh+/+ and Lbh−/− mice (n=6 per genotype) between the two genotypes. (D) Representative EP measured from Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ mice at 1 month. The mean of EP magnitude was 90.5±2.6 mV (Lbh+/+) and 100.6±2.3 mV (Lbh−/−) (n=6 per genotype). (E) ABR thresholds at 3 months (n=7 for each genotype). (F) DPOAE thresholds at 3 months (n=7 for each genotype). For all ABR and DPOAE comparisons, a two-way ANOVA with multiple t-tests was used. Data are mean±s.d. *P≤0.05 is the threshold (at these frequencies) or the magnitude of the response that is statistically significant compared with Lbh+/+ mice (n=7 for each genotype). The reported P-value is the adjusted P-value.

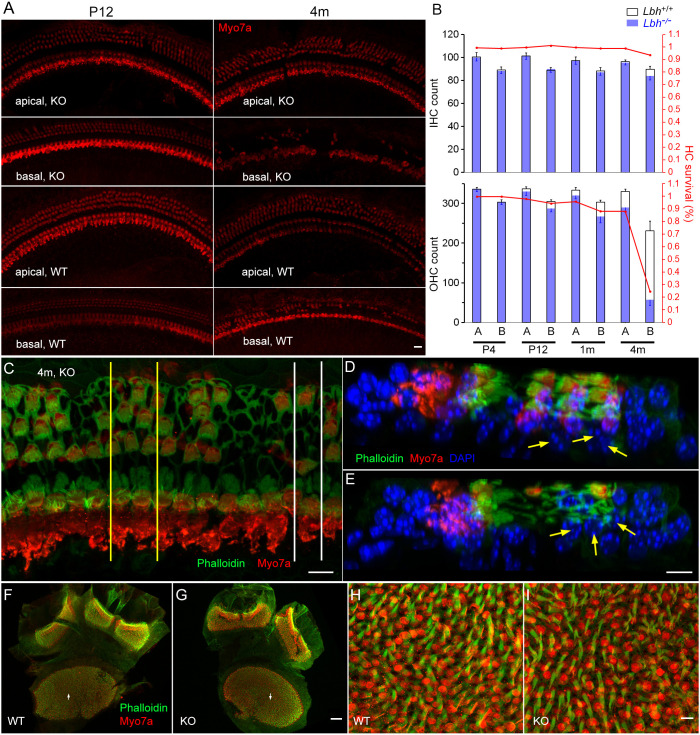

Morphological changes of HCs in Lbh−/− mice

We next investigated whether there was progressive HC loss in Lbh-deficient mice. To this end, we examined HC loss at the base and apex of the cochleae at four different ages in Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ mice (n=3 each). Fig. 3A shows representative confocal images at P12 and 4 months. The total number of IHCs and OHCs at the two cochlear locations was counted. Fig. 3B shows the HC count and percentage of surviving IHCs and OHCs at P3, P12, 1 and 4 months. No HC loss was apparent at either location in P3 Lbh−/− or Lbh+/+ cochleae. At P12, Lbh−/− cochleae exhibited sporadic OHC loss in the basal turn region. At 1 month, more OHC loss was seen in the basal turn region, and sporadic OHC loss was also seen in the apical turn (Fig. 3B). Finally, more OHCs were lost in both apical and basal turns at 4 months, with only ∼24% of OHCs remaining in the basal turn region of Lbh−/− cochleae (Fig. 3B). IHCs survived in the basal and apical turns, despite OHC loss. At 4 months, some IHC loss (∼8%) was seen in the basal turn. We also examined Deiters’ cell survival in a mid-cochlear region in which 50% of OHCs were lost at 4 months (Fig. 3C-E). As shown in Fig. 3D,E, the Deiters’ cells were still present despite loss of OHCs, suggesting that deletion of Lbh has no direct impact on the survival of Deiters’ cells. We also examined HC survival in the vestibular end organs at 3 months (Fig. 3F,G), but did not find any noticeable HC loss in the utricle and crista ampullaris of Lbh−/− mice. Representative high magnification images of utricle HCs are shown in Fig. 3H,I.

Fig. 3.

HC survival in the cochlear and vestibular sensory epithelia. (A) Representative confocal micrographs of HCs from an apical and a basal region in the cochleae of Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ mice at P12 and 4 months. (B) IHC and OHC count from the two apical and basal areas (∼4.5 and 1.4 mm from the hook, each with 850 µm in length) of three Lbh−/− and three Lbh+/+ mice at P3, P12, 1 and 4 months. HC count from age marched Lbh+/+ mice was used as a reference and is presented as percentage of HC survival. A represents apical turn and B represents basal turn HCs in the plot. (C) Confocal image obtained from a 4-month-old Lbh−/− cochlea. Yellow lines and white lines mark the areas that were optical sectioned and are presented in D and E. (D,E) Optical sections of the two areas in C. Deiters’ cells’ nuclei are marked by yellow arrows. The nuclei of Deiters’ cells are still present at this stage despite the loss of OHCs. (F,G) Utricle macula and crista ampullaris of Lbh+/+ and Lbh−/− mice at 3 months. (H,I) Higher magnification images of areas marked by arrows in F and G. Scale bars: 10 µm (A,C-E,H,I); 50 µm (F,G).

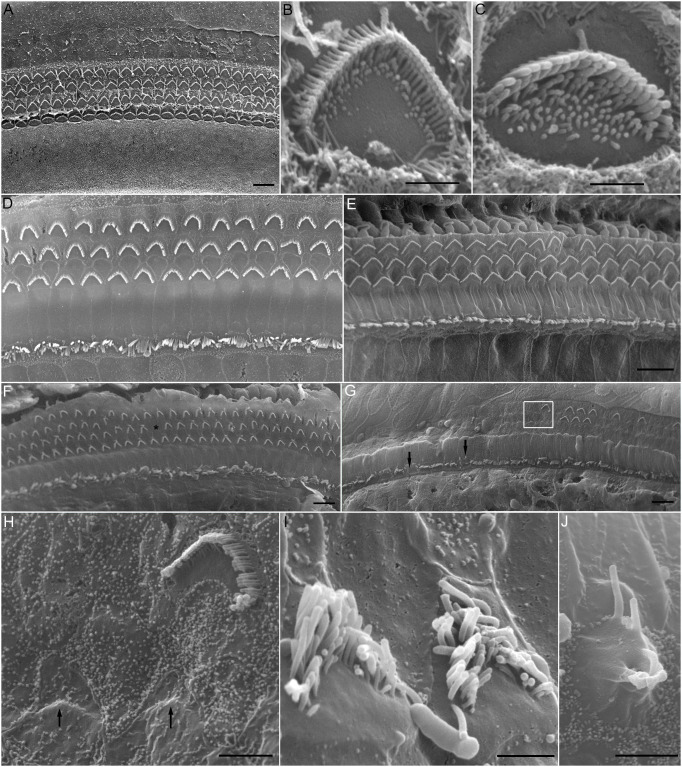

Scanning electron microscopy was used to examine stereocilia bundle morphology in Lbh−/− mice to determine whether LBH is necessary for the morphogenesis and maintenance of stereocilia, and for the differentiation of IHCs and OHCs. Fig. 4A shows an electron micrograph of stereocilia bundles in a P5 Lbh−/− cochlea. The characteristic one row of IHC and three rows of OHC stereocilia bundles were well organized and properly oriented. The stereocilia were arranged in a normal staircase fashion, with OHCs (Fig. 4B) and IHCs (Fig. 4C) having distinct morphologies when examined at higher magnification (Fig. 4B,C). Thus, no signs of abnormality or degeneration of stereocilia bundles were visible at P5. We also examined stereocilia bundle morphology of Lbh+/+ and Lbh−/− mice at 1 month and representative images are presented from Fig. 4D-J. As shown in Fig. 4D,E, no signs of stereocilia bundle degeneration and loss were observed in Lbh+/+ mice. In Lbh−/− cochleae, stereocilia bundles in the apical turn appeared largely normal (Fig. 4F), although sporadic OHC stereocilia bundle loss was observed (asterisk in Fig. 4F). However, degeneration and loss of OHC stereocilia bundles in the basal turn were more pronounced (Fig. 4G). Some of the remaining bundles showed signs of degeneration, such as absorption (marked by arrows in Fig. 4H), corruption and recession of the stereocilia on the edge of the bundle (Fig. 4I). Although the majority of IHC stereocilia bundles in the basal turn were present (Fig. 4G), some signs of IHC degeneration (such as fusion of the stereocilia in Fig. 4G,J) were also observed. The fact that the stereocilia bundles of IHCs and OHCs looked normal in P5 Lbh−/− mice suggests that LBH is not essential for morphogenesis of the stereocilia bundle. However, degeneration and loss of stereocilia bundles in adult Lbh−/− HCs suggest that the survival of HCs, especially OHCs, depends on LBH.

Fig. 4.

Scanning electron micrographs of stereocilia bundles of cochlear HCs in Lbh−/− null mice. (A) Micrograph of stereocilia bundles from the low-apical region of a cochlea at P5. (B,C) Higher magnification images of the stereocilia bundle of an OHC (B) and an IHC (C) from the basal turn of the same cochlea shown in panel A. (D,E) Micrographs of stereocilia bundles from mid-apical turn and basal turn of 1-month-old wild-type mouse. (F,G) Micrographs of stereocilia bundles from an apical turn region (F) and basal turn region (G) from a 1-month-old Lbh−/− mouse. Asterisk marks a missing OHC, and black arrows mark signs of degeneration of stereocilia bundles, such as fusion of stereocilia. A magnified image of the area within the white frame is highlighted in panel H. (H-J) Representative images of degenerating stereocilia bundles of OHCs (H,I) and an IHC (J) from mid-basal turn region of a 1-month-old Lbh−/− mouse. Black arrows in panel H indicate the complete absorption of stereocilia bundles due to degeneration. Scale bars: 10 µm (A,D-G); 1 µm (B,C); 2 µm (H); 1.5 µm (I); and 2.5 µm (J).

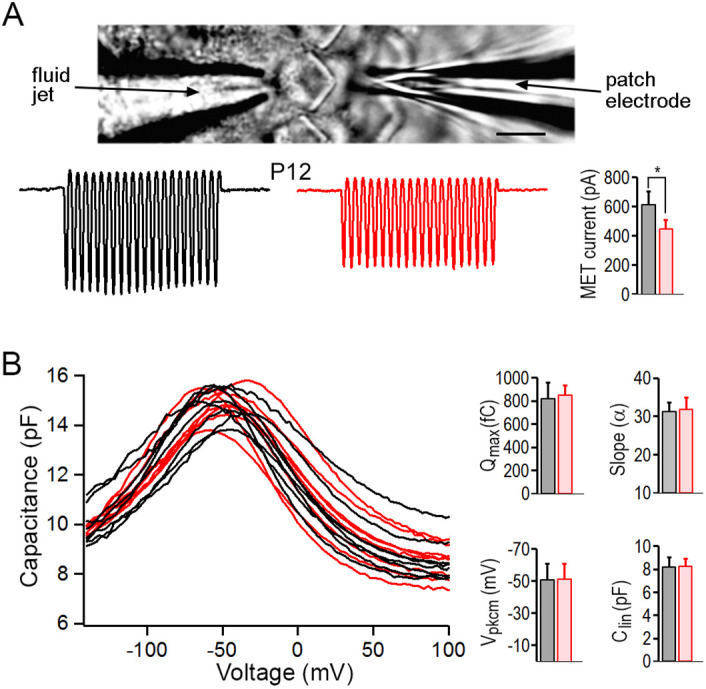

Mechanotransduction and electromotility of OHCs in Lbh−/− mice were not significantly changed

We investigated whether LBH plays a role in the development of mechanotransduction apparatus as LBH expression was upregulated in HCs. The voltage-clamp technique was used to measure the mechanoelectrical transduction (MET) current of OHC stereocilia bundles in response to bundle deflection in Lbh−/− mice. A coil preparation from the mid-cochlear region was used for recording (Jia and He, 2005). The bundle was deflected using the fluid jet technique (Kros et al., 1992; Jia et al., 2009) and the deflection-evoked MET current was recorded (Fig. 5A). Two examples of the maximal MET current from OHCs of Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ mice at P12 are shown in Fig. 5A. We compared maximal MET currents obtained from nine and eight OHCs from four Lbh+/+ and four Lbh−/− mice, respectively. The magnitude of the current was 614±90 pA (mean±s.d.) for Lbh+/+ and 449±57 pA for Lbh−/− OHCs. Despite a significant reduction (P=4.8×10−4), the presence of MET current suggests that the mechanotransduction apparatus is functional in Lbh−/− OHCs.

Fig. 5.

OHC function examined using whole-cell voltage-clamp technique. (A) Recording of MET current in vitro and representative MET current recorded from OHCs in lower apical turn of Lbh−/− (red) and Lbh+/+ (black) mice at P12. *P<0.05. Scale bar: 5 µm. (B) NLC measured from 9 and 8 OHCs in the lower apical turn of Lbh−/− (red) and Lbh+/+ (black) mice, respectively, at P12. Curve fitting using a two-states Boltzmann function yielded four parameters: Qmax; slope (α); Vpkcm; and Clin. Data are mean±s.d. P=0.29, 0.33, 0.47 and 0.42, respectively, for the four parameters (one-tailed distribution, two-sample unequal variance Student's t-tests).

Prestin-based somatic motility is a unique property of OHCs (Zheng et al., 2000). As LBH is predominantly expressed in OHCs, we investigated whether LBH regulates prestin expression. OHC electromotility occurs after birth (He et al., 1994; He, 1997); thus, we measured non-linear capacitance (NLC), an electric signature of electromotility (Ashmore, 1989; Santos-Sacchi, 1991; He et al., 2010), from Lbh−/− OHCs at P12 when OHC degeneration was still mild. Fig. 5B shows NLC measured from OHCs isolated from the mid-cochlear region in Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ mice. A two-state Boltzmann function relating non-linear charge movement to voltage (Santos-Sacchi, 1991; He et al., 2010) was used to compute four parameters: the maximum charge transferred through the membrane's electric field (Qmax); the slope factor of the voltage dependence (α); the voltage at peak capacitance (Vpkcm); and the linear membrane capacitance (Clin). No significant differences in any of these parameters were found between Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ OHCs (Fig. 5B). Thus, OHC motility does not appear to be affected by loss of LBH.

Changes in OHC gene expression after deletion of Lbh

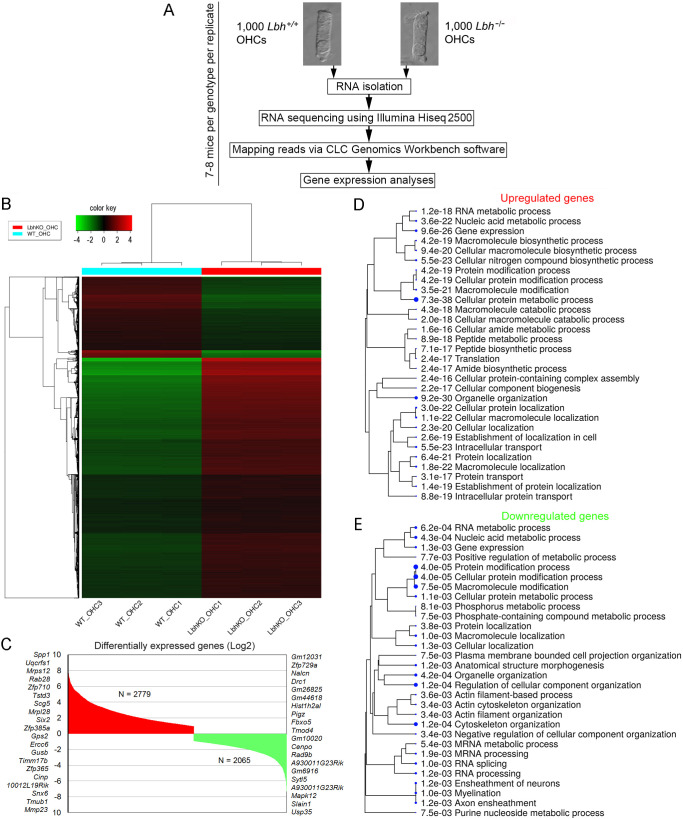

To identify the molecular mechanism underlying the observed hearing and HC loss in Lbh-null mice, we performed OHC-specific RNA-seq transcriptome analyses. Although IHC degeneration and loss were also seen in Lbh-null mice, OHC degeneration and loss were more prominent. OHCs were isolated from P12 Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ mice (Fig. 6A), as HC degeneration in Lbh- null mice had just begun at this stage (Fig. 3). The normalized RPKM values are provided as Table S1. Fig. 6B shows a correlation between the datasets by Euclidean distance in a heatmap of 10,000 genes with a cutoff z-score calculated as the absolute values from the mean. Comparison of the gene expression profiles between Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ OHCs identified 2779 differentially upregulated and 2065 downregulated genes {defined as those with ≥1.0 log2 fold change in expression between the two cell types with statistical significance [false discovery rate (FDR) P≤0.05]} in Lbh−/− OHCs (Fig. 6C; Table S2). Among those genes, biological processes related to gene expression, protein metabolic process and organelle organization were significantly enriched in Lbh−/− OHCs, as assessed by ShinyGO analysis (Fig. 6D,E). In contrast, Lbh+/+ OHCs showed greater enrichment in genes associated with cytoskeletal and actin filament organization, membrane-bound cell projection organization, anatomical structure morphogenesis, RNA splicing and axon ensheathment (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

RNA-seq transcriptome analysis of Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ OHCs. (A) Workflow of the experimental design for RNA-seq analysis of OHCs isolated from Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ mice. (B) Euclidean distance heatmap of 10,000 genes (z-score cutoff=4), depicting the average linkage between genes expressed in Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ OHCs. (C) Upregulated and downregulated genes in Lbh−/− compared to Lbh+/+ OHCs. The top 20 genes upregulated or downregulated are shown on either side of the plot. (D) ShinyGO biological processes enriched in upregulated genes in Lbh−/− compared to Lbh+/+ OHCs. (E) ShinyGO biological processes enriched in downregulated genes in Lbh−/− compared to Lbh+/+ OHCs.

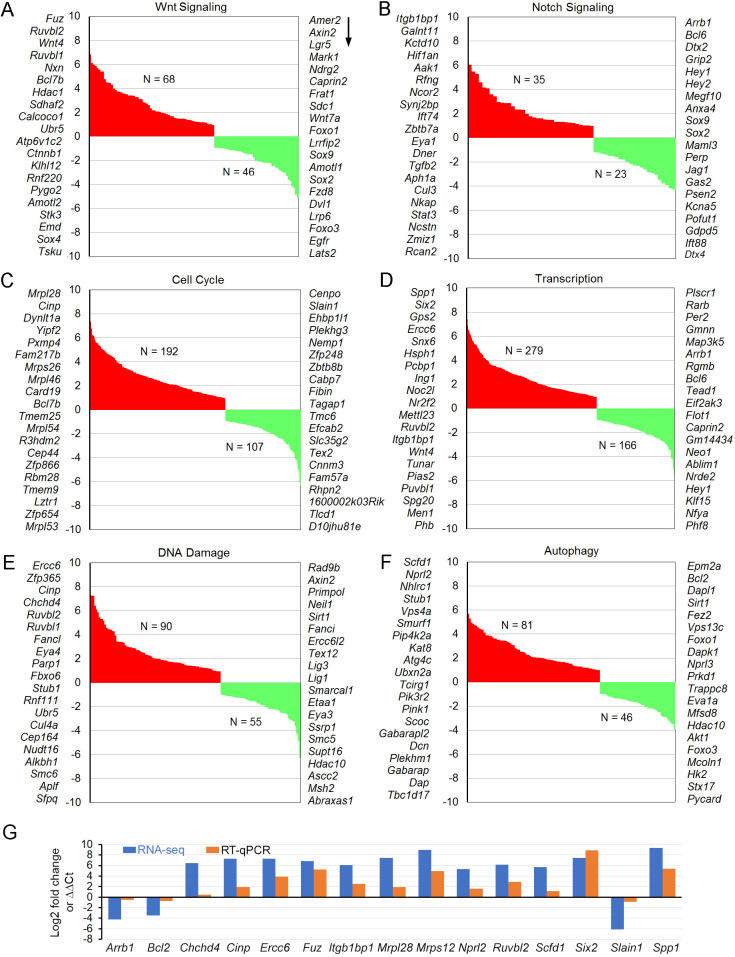

Additionally, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using the Broad Institute software. Enriched pathways in Lbh−/− compared to Lbh+/+ OHCs, including Wnt and Notch signaling pathways (Table S3), cell cycle regulation (Table S4), regulation of nucleic acid-templated transcription (Table S4), DNA damage/repair and autophagy (Table S5) are presented in Fig. 7. As Wnt and Notch play important roles in HC differentiation and regeneration, and LBH is a Wnt target gene known to regulate cell differentiation states in other cell types (Conen et al., 2009; Rieger et al., 2010; Lindley et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015), the expression of genes related to Wnt and Notch signaling was examined in more detail. Although Notch1 (although not among the top 20 presented in Fig. 7), Wnt4, Fzd4, Ctnnb1 (β-catenin) and Fuz were all significantly upregulated, some key target genes of Wnt (e.g. Axin2, Lgr5 and Lrp6) and Notch (i.e. Hey1 and Hey2) that mirror signaling activity, were downregulated in Lbh-null OHCs (Fig. 7A,B). For cell cycle control, 192 genes were upregulated and 107 were downregulated (Fig. 7C). Analysis of transcription factors showed that 430 and 281 transcription factors were upregulated or downregulated in the Lbh−/− OHCs, respectively (Fig. 7D). The top ten upregulated transcription factors include Spp1, Six2, Gps2, Ercc6, Snx6, Tob1, Hsph1, Pcbp1, Ing1 and Noc2l; whereas the top ten downregulated are Plscr1, Rarb, Per2, Gmnn, Map3k5, Arrb1, Rgmb, Bcl6, Tead1 and Eif2ak3. As LBH is implicated in DNA damage/repair in some cells (Deng et al., 2010; Matsuda et al., 2017), the enrichment in these genes was also analyzed (Fig. 7E,F). Ninety and 55 genes associated with DNA damage/repair were upregulated and downregulated in Lbh−/− OHCs, respectively. Interestingly, autophagy-related genes were also found to be enriched, whereby 81 genes were upregulated and 46 were downregulated in Lbh−/− OHCs. Tables S2-S5 include the differentially expressed genes and significantly enriched genes associated with Wnt and Notch signaling, transcription, cell cycle, DNA damage/repair and autophagy in the Lbh-null OHCs.

Fig. 7.

GSEA of Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ OHCs transcriptomes. Enriched pathways (FDR <0.25) Lbh−/− null OHCs include regulation of Wnt signaling (A), Notch signaling (B), cell cycle (C), nucleic acid-templated transcription (D), DNA damage/repair (E) and autophagy (F). The total numbers of upregulated (red) and downregulated (green) genes within each pathway are indicated, and the top 20 genes in each category are listed on either side of the graph, with greatest to least fold change in downward direction (arrow). (G) Validation of differentially expressed cell survival genes using RT-qPCR. Log2 fold changes (Lbh−/− versus Lbh+/+) from RNA-seq and ΔΔCt values (normalized to Actb) from RT-qPCR for each gene are shown.

RT-qPCR was used to validate selected differentially expressed genes (between P12 Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ OHCs) identified by the RNA-seq analysis. Seventeen genes involved in key biological processes related to HC maintenance/degeneration were chosen for comparison. As shown in Fig. 7G, the trend of differential expression of these genes is highly consistent between RNA-seq analyses and RT-qPCR, confirming LBH-dependent gene expression changes in the global RNA-seq analysis.

DISCUSSION

LBH, a transcriptional regulator highly conserved in evolution from zebrafish to human, is implicated in the development of heart (Briegel and Joyner, 2001; Briegel et al., 2005; Al-Ali et al., 2010), bone (Conen et al., 2009) and mammary gland (Lindley et al., 2015). A zebrafish LBH homologue, lbh-like, is necessary for photoreceptor differentiation Li et al., 2015). Here, we identified a novel role for LBH in the maintenance of the adult auditory sensory epithelium.

Unlike in heart, bone, mammary gland and eye development, in which LBH or lbh-like proteins control progenitor/stem cell fate, self-renewal and/or differentiation, LBH does not appear to be critical for cochlear HC differentiation, specification and stereocilia morphogenesis. This is supported by the fact that morphologically distinct IHCs and OHCs were present in Lbh-null cochleae before P12. Stereocilia bundles of Lbh-null HCs appeared normal and were functional, as mechanical stimulus was able to evoke MET currents. Furthermore, LBH is not necessary for the expression of prestin to confer electromotility, a specialization of OHCs (Zheng et al., 2000; He et al., 2014). Therefore, we conclude that LBH is not necessary for stereocilia morphogenesis and HC differentiation, specification and development.

However, we found that LBH is critical for stereocilia bundle maintenance and HC survival in adult mice. When Lbh was deleted, stereocilia and HCs began to degenerate as early as P12. The degeneration was progressive from OHCs to IHCs and from cochlear base to apex, similar to the pattern seen during age-related hearing loss in some animal models, such as C57BL/6 mice. Consistent with these morphological changes, gene pathways of actin filament and cell projection organization underlying stereocilia maintenance were upregulated in the wild-type OHCs but not in the Lbh-null OHCs. Our findings, to the best of our knowledge, are the first demonstration that loss of LBH causes degeneration of cochlear HCs, leading to progressive hearing loss. Furthermore, these results provide evidence that LBH is required for adult tissue maintenance. Although LBH has been previously implicated in tissue maintenance and the regeneration of the postnatal mammary gland by promoting the self-renewal and maintenance of the basal mammary epithelial stem cell pool (Lindley et al., 2015), HCs are different because they are terminally differentiated postmitotic cells that have lost the ability to proliferate and regenerate. In this regard, it is worth noting that the loss of LBH is also associated with Alzheimer's, a neurodegenerative disease affecting postmitotic neurons (Yamaguchi-Kabata et al., 2018). Thus, LBH appears to be required for tissue maintenance in both regenerative and non-regenerative adult tissues.

OHC-specific RNA-seq and bioinformatic analyses examined the potential molecular mechanisms underlying HC degeneration after Lbh deletion. Our analyses showed that a greater number of genes were upregulated in Lbh-null OHCs compared to wild-type littermate OHCs. Importantly, genes and pathways associated with transcriptional regulation, cell cycle, DNA repair/maintenance and autophagy, as well as Wnt and Notch signaling, were significantly enriched in Lbh-null OHCs. Notch and Wnt signaling are known to be critical for the differentiation and specification of HCs and SCs during inner ear morphogenesis and development (Raft and Groves, 2015). Although Notch and Wnt signaling are known to be downregulated in the inner ear after birth (Kiernan, 2013), low level expression of Notch and Wnt signaling is still necessary for the survival for HCs. As normal adult OHCs retain low levels of Notch and Wnt signaling, we speculate that LBH is required for maintaining low level Notch and Wnt activity in OHCs via a feedback mechanism, and that diminished Notch/Wnt activity following LBH ablation, as measured by reduced Wnt/Notch target gene expression in Lbh-null OHCs, may lead to OHC degeneration. In other words, LBH may promote the maintenance of HCs by regulating Notch and Wnt signaling activity. Similarly, previous studies have also shown that dysregulation of Notch and Wnt signaling, and alterations in LBH levels can perturb the balance between proliferation, differentiation and maintenance in different tissues (Rieger et al., 2010; Li et al., 2015; Ashad-Bishop et al., 2019).

LBH function as a transcription co-factor has been shown by multiple studies (Briegel and Joyner, 2001; Briegel et al., 2005; Deng et al., 2010; Al-Ali et al., 2010). Co-factors do not bind DNA directly, but rather interact specifically and non-covalently with a transcription factor to activate or repress the transcription of specific genes. So far, 513 genes are assumed to be co-factors based on the curated GO Molecular Function Annotations dataset (Rouillard et al., 2016). The transcription factor(s) that LBH interacts with are yet to be identified. This study identified 430 and 281 transcription factors being upregulated and downregulated in the Lbh−/− OHCs, respectively. Six2, which is associated with the development of several organs, including kidney, stomach and limb (Self et al., 2006; Kobayashi et al., 2008), is one of the top ten upregulated transcription factors (Fig. 7D,G). SIX2 has been shown to act through its interaction with TCF7L2 and OSR1 in a canonical Wnt signaling independent manner, preventing transcription of differentiation genes in cap mesenchyme, such as WNT4 (Xu et al., 2014; Park et al., 2012). We note that Six2 is differentially expressed in OHCs of neonatal and adult mice (Li et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Kolla et al., 2020). It is possible that LBH interacts with SIX2 to alter Notch signaling. Higher expression of Six2 in OHCs than in IHCs and vestibular HCs may also explain why Lbh deletion has a larger effect on OHCs than other HC types.

Although we observed deregulation of Wnt and Notch pathway genes in Lbh-null OHCs, many genes that are involved in cell cycle regulation, regulation of nucleic acid-templated transcription, DNA repair/maintenance and autophagy were also de-regulated. Noticeably, Plekhg3, Hdac1, Hdac10, Zfp365, Ercc6, Foxo1, Foxo3 and Bcl2 were among those genes that had expression that was significantly upregulated or downregulated in Lbh-null OHCs. PLEKHG3 has been shown to be indispensable for inducing and maintaining cell polarity by promoting Rac small GTPase and actin polymerization (Nguyen et al., 2016). We speculate that Plekhg3 may be involved with actin polymerization in the cytoskeleton and stereocilia in HCs. Hdac1 and Hdac10 are components of the histone deacetylase complex and play a key role in transcriptional regulation, cell cycle progression and apoptosis. Zfp365 (ZNF365 in humans) encodes a zinc finger protein that may play a role in the repair of DNA damage and maintenance of genome stability. The encoded protein of Ercc6 has ATP-stimulated ATPase activity and interacts with several transcription and excision repair proteins. Foxo1 is the main target of insulin signaling and regulates metabolic homeostasis in response to oxidative stress, whereas Foxo3 likely functions as a trigger for apoptosis through the expression of genes necessary for cell death. Bcl2 encodes an integral outer mitochondrial membrane protein that blocks the apoptotic death of some cells, such as lymphocytes. Interestingly, all these genes were also found to be dysregulated in aging HCs (our unpublished observation). Therefore, although we speculate that diminished Notch/Wnt activity is involved in HC degeneration in Lbh-null mice, it is also possible that HC degeneration and loss are due to an increased genotoxic and cell stress as a result of a change in metabolic processes, DNA damage/repair and autophagy. Indeed, a recent study showed that LBH is involved in cell cycle regulation and LBH-deficiency induced S-phase arrest, and increased DNA damage in articular cartilage (Matsuda et al., 2017). Cell-based transcriptional reporter assays further indicate LBH may repress the transcriptional activation of p53 (Deng et al., 2010), a key regulator of DNA damage control and apoptosis. Our analyses showed that Trp53 (p53) was upregulated in Lbh-null OHCs (Table S1). We would like to emphasize that cell degeneration and death involve the complex regulation of many genes and pathways turned on or off at different time points. Thus, it is difficult to pinpoint which pathway(s) play a key role in OHC degeneration and loss in Lbh-null mice.

LBH is predominantly localized to the nucleus in most cells (Briegel and Joyner, 2001; Briegel et al., 2005; Ai et al., 2008; Lindley and Briegel, 2013; Lindley et al., 2015; Garikapati et al., 2021 preprint); however, LBH expression in HCs was predominantly cytoplasmic, although weak nuclear LBH positivity was also observed. In fibroblast-like COS-7 cells, co-localization analysis shows that LBH proteins are localized to both the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Briegel and Joyner, 2001; Ai et al., 2008). In postmitotic neurons, LBH is also found to be more cytoplasmic than nuclear (unpublished observation). Some transcriptional co-factors, such as TAZ/YAP, are detected in the cytoplasm and can translocate into the nucleus upon mechanostimulation (Low et al., 2014). For example, the STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) transcription factors are constantly shuttling between nucleus and cytoplasm irrespective of cytokine stimulation (Low et al., 2014; Meyer and Vinkemeier, 2004). It is therefore plausible that cytoplasmic LBH in OHCs may translocate to the nucleus when needed. It is also possible that cytoplasmic LBH may interact with different proteins and have a different function than in the nucleus.

Collectively, this is the first study showing that transcription co-factor LBH can influence stereocilia bundle maintenance and the survival of cochlear HCs, especially OHCs. Although the underlying mechanisms of how LBH interacts with transcription factor(s) remain to be further investigated, our analyses showed significant gene enrichment of biological processes related to transcriptional regulation and dysregulation of signaling pathways controlling cell maintenance. Importantly, our work points to LBH as a novel causative factor and putative molecular target in progressive hearing loss. It also identifies LBH as paramount for adult tissue maintenance, which could be exploited therapeutically to slow the onset and progression of HC aging.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Lbh knockout mice

Male and female Lbh-mutant mice (provided by Dr Karoline Briegel at University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, FL, USA) were used for experiments. Mice with a conditional null allele of Lbh were generated by flanking exon 2 with loxP sites (Lbhflox). LbhloxP mice were then crossed with a Rosa26-Cre line, resulting in the ubiquitous deletion of exon 2 and the abolishment of LBH protein expression. Details for generating the mice have been described previously (Lindley and Briegel, 2013). Mice homozygous for the Lbh null allele were viable and fertile but displayed abnormal mammary gland development after birth (Lindley and Briegel, 2013). All animal experiments were performed according to approved guidelines.

ABR and DPOAE measurements

ABRs were recorded in response to tone bursts from 4 to 50 kHz using standard procedures described previously (Zhang et al., 2013). Response signals were amplified (100,000×), filtered, averaged and acquired by TDT RZ6 (Tucker-Davis Technologies, Alachua, FL, USA). Threshold is defined visually as the lowest sound pressure level (in decibel) at which any wave (wave I to wave IV) is detected and reproducible above the noise level.

The DPOAE at the frequency of 2f1 -f2 was recorded in response to f1 and f2, with f2/f1=1.2 and the f2 level 10 dB lower than the f1 level. The sound pressure obtained from the microphone in the ear canal was amplified and fast Fourier transforms were computed from averaged waveforms of ear canal sound pressure. The DPOAE threshold is defined as the f1 sound pressure level (measured in decibels) required to produce a response above the noise level at the frequency of 2f1-f2.

Recording of CM and EP

Procedures for recording CM and EP have been described previously (Zhang et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016). A silver electrode was placed on the ridge near the round window for recording CM. An 8 kHz tone burst (90 dB) was delivered through a calibrated TDT MF1 multi-field magnetic speaker. The biological signals were amplified using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and acquired by pClamp 9.2 software (Molecular Devices) running on an IBM-compatible computer. The sampling frequency was 50 kHz.

For recording the EP, a basal turn location was chosen. A hole was made using a fine drill. A glass capillary pipette electrode (10 MΩ) was mounted on a hydraulic micromanipulator and advanced until a stable positive potential was observed. The signals were filtered and amplified under current-clamp mode using an Axopatch 200B amplifier and acquired using pClamp 9.2 software. The sampling frequency was 10 kHz.

Immunocytochemistry and HC count

The cochlea and vestibule from Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ were fixed for 24 h with 4% paraformaldehyde. The basilar member, including the organ of Corti, the utricle and ampulla were dissected out. Antibodies against MYO7A (Proteus, 25-6790, 1:300 dilution) or LBH (Sigma-Aldrich, HPA034669, 1:200 dilution) and secondary antibody (Life Technologies, 1579044, 1:400 dilution) were used. Alexa Fluorescent Phalloidin (Invitrogen, 565227, 1:400 dilution) was used to label F-actin (stereocilia bundles), and DAPI was used to stain nuclei. Tissues were mounted on glass microscopy slides and imaged using a Leica TCS SP8 MP confocal microscope. HC counts from two areas [∼1.4 and 4.5 mm from the hook, each 850 µm (425 µm per frame×2) in length] were obtained for HC count from confocal images offline (Liu et al., 2016).

Scanning electron microscopy

The cochleae from Lbh-mutant mice were fixed for 24 h with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 2 mM CaCl2 washed in buffer. After the cochlear wall was removed, the cochleae were then post-fixed for 1 h with 1% OsO4 in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer and washed. The cochleae were dehydrated via an ethanol series, critical point dried from CO2 and sputter-coated with gold. The morphology of the HCs was examined using a FEI Quanta 200 scanning electron microscope and photographed.

Whole-cell voltage-clamp techniques for recording MET current and NLC

Details for recording MET currents from auditory sensory epithelium have been described previously (Kros et al., 1992; Jia and He, 2005). A segment of auditory sensory epithelium was prepared from the mid-cochlear and bathed in extracellular solution containing 120 mM NaCl, 20 mM TEA-Cl, 2 mM CoCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 5 mM glucose (pH 7.4). The patch electrodes were back-filled with internal solution, which contains 140 mM CsCl, 0.1 mMCaCl2, 3.5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM MgATP, 5 mM EGTA-KOH and 10 mM HEPES-KOH. The solution was adjusted to pH 7.4 and the osmolarity was adjusted to 300 mOsm with glucose. The pipettes had initial bath resistances of ∼3-5 MΩ. After the whole-cell configuration was established and series resistance was ∼70% compensated, the cell was held under voltage-clamp mode to record MET currents in response to bundle deflection by a fluid jet positioned ∼10-15 µm away from the bundle. Sinusoidal bursts (100 Hz) with different magnitudes were used to drive the fluid jet as described previously. Holding potential was normally set near −70 mV. The currents (filtered at 2 kHz) were amplified using an Axopatch 200B amplifier and acquired using pClamp 9.2. Data were analyzed using Clampfit in the pClamp software package and Igor Pro (WaveMetrics).

For recording NLC, the cells were bathed in extracellular solution containing 120 mM NaCl, 20VmM TEA-Cl, 2 mM CoCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 5 mM glucose (pH 7.4). The internal solution contains 140 mM CsCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM EGTA and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). The two-sine voltage stimulus protocol (10 mV peak at both 390.6 and 781.2 Hz) with subsequent fast Fourier transform-based admittance analysis (jClamp, version 15.1, SciSoft) was used to measure membrane capacitance using jClamp software. Fits to the capacitance data were made using IgorPro (Wavemetrics). The maximum charge transferred through the membrane's electric field (Qmax), the slope factor of the voltage dependence (α), the voltage at peak capacitance (Vpkcm) and the linear membrane capacitance (Clin) were calculated.

Cell isolation, RNA preparation and RNA-seq

Homozygous and wild-type mice at P12 were used for gene expression analysis. Details for cell isolation and collection have been described previously (Li et al., 2018). Approximately 1000 OHCs were collected from 7-8 mice for one biological repeat per genotype. Three biological replicates were prepared for each genotype.

Total RNA, including small RNAs (> ∼18 nucleotides), were extracted and purified using the Qiagen RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). To eliminate DNA contamination in the collected RNA, on-column DNase digestion was performed. The quality and quantity of RNA were examined using an Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Genome-wide transcriptome libraries were prepared from three biological replicates separately for Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ OHCs. The SMART-Seq V4 Ultra Low Input RNA kit (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA, USA) and the Nextera Library preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) were used. An Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and a Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used to assess library size and concentration before sequencing. Transcriptome libraries were sequenced using the HiSeq 2500 Sequencing System (Illumina). Four samples per lane were sequenced, generating ∼60 million, 100 bp single-end reads per sample. The files from the multiplexed RNA-seq samples were demulitplexed and fastq files were obtained.

The CLC Genomics Workbench software (CLC Bio, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to individually map the reads to the exonic, intronic and intergenic sections of the mouse genome (mm10, build name GRCm38). Gene expression values were normalized as reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM). Log fold changes and FDR P-values were calculated, and the dataset was exported for further analysis.

Real-time quantitative PCR for validation

OHCs were collected as described above from 14 additional P12 Lbh−/− mice and 15 age-matched Lbh+/+ mice for RT-qPCR. Total RNA was isolated using the Qiagen miRNeasy kit and quantified using a nanodrop spectrophotometer. cDNA libraries were prepared from isolated RNA with the iSCRIPT master mix (Bio-Rad). Oligonucleotide primers were acquired from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA). The sequences (forward and reverse) of oligonucleotide primers are: Actb (5′-GTACTCTGTGTGGATCGGTGG-3′, 5′-ACGCAGCTCAGTAACAGTCC-3′), Arrb1 (′5-AAGGGACACGAGTGTTCAAGA-3′, 5′-GATCCACCAGGACCACACCA-3′), Bcl2 (5′-GAGTTCGGTGGGGTCATGTG-3′, 5′-AGTTCCACAAAGGCATCCCAG-3′), Chchd4 (5′-CGGGAACAACCATGTCCTACT-3′, 5′-GGCAGTATCAACCCGTGCTC-3′), Cinp (5′-CCATCTTGGACGGCTTGACTA-3′, 5′-ACGTGTGAAATAGAGGGGGC-3′), Ercc6 (5′-TGAGCAGGTCTTATTTTGCCG-3′, 5′-AAAGAGGTCAGGGTGGTTGC-3′), Fuz (5′-CTGAAGAAAGAATTGAGGGCCAG-3′, 5′-CCTCTGCAAACCCTGAAAGG-3′), Itgb1bp1 (5′-ACACTTGTTCCACTGCGGC-3′, 5′-CCACAGACTTGCTCTTTGTACTG-3′), Mrpl28 (5′-CACTCGGGAGCTTTACAGTGA-3′, 5′-GCTTCAGGTCCATGCCAAAC-3′), Mrps12 (5′-CCGCTAGGTTGGTGAGGTG-3′, 5′-AAAACAGAAAGTCCCCTCGCA-3′), Nprl2 (5′-CTGTCCTACGTCACCAAGCA-3′, 5′-CTGGATCAGCTTCCTTTCATCA-3′), Ruvbl2 (5′-CACACCATTCACAGCCATCG-3′, 5′-CTCTGTCTCCTCCTTGATCCG-3′), Scfd1 (5′-CGTCCGAGGTTGATTTGGAG-3′, 5′-TAGTGTTTCCGTAGCTGGCA-3′), Six2 (5-CGCAAGTCAGCAACTGGTTC-3, 5′-GAACTGCCTAGCACCGACTT-3′), Slain1 (5′-TCAGCCCTTATAGCAATGGCA-3′, 5′-ACTGTCGATGGATGACTGCG-3′), Spp1 (5′-ATCCTTGCTTGGGTTTGCAG-3′, 5′-TGGTCGTAGTTAGTCCCTCAGA-3′), Uqcrfs1 (5′-TTCTGGATGTGAAGCGACCC-3′, 5′-CAGAGAAGTCGGGCACCTTG-3′), Zfp365 (5-GAAGCCCAGATGCCTAAGCC-3′, 5′-GACTCAGCCGGTTCGTGAAT-3′).

RT-qPCR reactions were prepared as 10 µl reactions, including Lbh−/− or Lbh+/+ OHC cDNA, PowerUp SYBR green master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), gene-specific forward and reverse primers, and run in triplicate on a Bio-Rad CFX96 Touch real-time PCR machine. Primer specificity was confirmed by melt curve analysis. Quantified expression (Ct) of each gene (gene of interest or GOI) was normalized to the Ct value of a housekeeping gene (Actb) [ΔCt=Ct(GOI) — CtAVG Actb]. Then differential expression of the gene between Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ OHCs was calculated as ΔΔCt (ΔΔCt=ΔCt Lbh−/− - ΔCt Lbh+/+). The relationships between the RNA-seq derived-log2 fold change values and ΔΔCq values from RT-qPCR between Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ OHCs were compared to confirm trends in expression.

Bioinformatic analyses

The expressed genes were examined for enrichment using Broad Institute GSEA v. 3.0 (Mootha et al., 2003; Subramanian et al., 2005), iDEP 0.85 and ShinyGO (Ge-lab.org) (Ge et al., 2018). Enriched biological processes and molecular functions, classified according to gene ontology terms, as well as signaling pathways in the Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ OHCs were examined (FDR cutoff <0.05). With the RPKM expression value arbitrarily set at ≥0.10 (FDR, P≤0.05), expression values from Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ OHCs were inputted into iDEP for analysis and log transformed. For reference and verification, additional resources, such as the Ensembl database, AmiGO (http://amigo.geneontology.org/amigo), gEAR (www.umgear.org) and SHIELD (https://shield.hms.harvard.edu/index.html), were also used. No custom code was used in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Mean±s.d. was calculated based on measurements from three different types of mice. Student's t-test was used to determine statistical significance between two different conditions or two genotypes for each parameter. Two-way ANOVA with multiple t-tests using the Holm–Sidak correction for multiple comparisons was also used to determine statistical significance. P≤0.05 was regarded as significant. For transcriptome analysis, mean±s.d. was calculated for three biological repeats from Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ OHCs. ANOVA FDR-corrected P-values were used to compare average expression (RPKM) values for each transcript and a FDR of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Nebraska DNA Sequencing Core Facility for performing RNA-seq. The University of Nebraska DNA Sequencing Core and Imaging Core receive partial support from the National Center for Research Resources (RR018788). We also thank Tom Bargar and Nicholas Conoan of the Electron Microscopy Core Facility at the University of Nebraska Medical Center for technical assistance. The facility is supported by state funds from the Nebraska Research Initiative and the University of Nebraska Foundation, and institutionally by the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: K.J.B., D.Z.H.; Methodology: H.L., M.G., S.W.M., Y.L., X.L., K.J.B., D.Z.H.; Validation: K.P.G., S.W.M., Y.L.; Formal analysis: K.P.G., Y.L., K.J.B., D.Z.H.; Investigation: H.L., M.G., K.J.B., D.Z.H.; Resources: X.L.; Data curation: H.L., K.P.G.; Writing - original draft: D.Z.H.; Writing - review & editing: K.J.B., D.Z.H.; Supervision: K.J.B., D.Z.H.; Funding acquisition: K.J.B., D.Z.H.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (R01 DC016807 to D.Z.H., and R01 DC005575 to X.L.) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01 GM113256 to K.J.B.). Y.L. is supported by the National Science Foundation of China (81600798 and 81770996). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Data availability

The raw RNA-seq data of P12 OHCs from Lbh−/− and Lbh+/+ mice are available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive under accession SRP212389. The project metadata is available under BioProject accession PRJNA552016.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at https://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.254458.supplemental

Peer review history

The peer review history is available online at https://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.254458.reviewer-comments.pdf

References

- Ai, J., Wang, Y., Tan, K., Deng, Y., Luo, N., Yuan, W.Wang, Z., Li, Y., Wang, Y., Mo, X.et al. (2008). A human homolog of mouse Lbh gene, hLBH, expresses in heart and activates SRE and AP-1 mediated MAPK signaling pathway. Mol. Biol. Rep. 35, 179-187. 10.1007/s11033-007-9068-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ali, H., Rieger, M. E., Seldeen, K. L., Harris, T. K., Farooq, A. and Briegel, K. J. (2010). Biophysical characterization reveals structural disorder in the developmental transcriptional regulator LBH. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 391, 1104-1109. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashad-Bishop, K., Garikapati, K., Lindley, L. E., Jorda, M. and Briegel, K. J. (2019). Loss of Limb-Bud-and-Heart (LBH) attenuates mammary hyperplasia and tumor development in MMTV-Wnt1 transgenic mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 508, 536-542. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.11.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore, J. F. (1989). Motor coupling in mammalian outer hair cells. In Cochlear Mechanisms (ed. Wilson J. P. and Kemp D. T.), pp. 107-114. New York: Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Briegel, K. J. and Joyner, A. L. (2001). Identification and characterization of Lbh, a novel conserved nuclear protein expressed during early limb and heart development. Dev. Biol. 233, 291-304. 10.1006/dbio.2001.0225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briegel, K. J., Baldwin, H. S., Epstein, J. A. and Joyner, A. L. (2005). Congenital heart disease reminiscent of partial trisomy 2p syndrome in mice transgenic for the transcription factor Lbh. Development 132, 3305-3316. 10.1242/dev.01887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell, W. E., Bader, C. R., Bertrand, D. and de Ribaupierre, Y. (1985). Evoked mechanical responses of isolated cochlear outer hair cells. Science 227, 194-196. 10.1126/science.3966153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, T., Jen, H.-I., Kang, H., Klisch, T. J., Zoghbi, H. Y. and Groves, A. K. (2015). Characterization of the transcriptome of nascent hair cells and identification of direct targets of the Atoh1 transcription factor. J. Neurosci. 35, 5870-5883. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5083-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conen, K. L., Nishimori, S., Provot, S. and Kronenberg, H. M. (2009). The transcriptional cofactor Lbh regulates angiogenesis and endochondral bone formation during fetal bone development. Dev. Biol. 333, 348-358. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos, P. (1992). The active cochlea. J. Neurosci. 12, 4575-4585. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-12-04575.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos, P., Wu, X., Cheatham, M. A., Gao, J., Zheng, J., Anderson, C. T., Jia, S., Wang, X., Cheng, W. H. Y., Sengupta, S.et al. (2008). Prestin-based outer hair cell motility is necessary for mammalian cochlear amplification. Neuron 58, 333-339. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y., Li, Y., Fan, X., Yuan, W., Xie, H., Mo, X.Yan, Y., Zhou, J., Wang, Y., Ye, X.et al. (2010). Synergistic efficacy of LBH and αB-crystallin through inhibiting transcriptional activities of p53 and p21. BMB Rep. 43, 432-437. 10.5483/BMBRep.2010.43.6.432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebeid, M., Sripal, P., Pecka, J., Beisel, K. W., Kwan, K. and Soukup, G. A. (2017). Transcriptome-wide comparison of the impact of Atoh1 and miR-183 family on pluripotent stem cells and multipotent otic progenitor cells. PLoS ONE 12, e0180855. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkon, R., Milon, B., Morrison, L., Shah, M., Vijayakumar, S., Racherla, M., Leitch, C. C., Silipino, L., Hadi, S., Weiss-Gayet, M.et al. (2015). RFX transcription factors are essential for hearing in mice. Nat. Commun. 6, 8549. 10.1038/ncomms9549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fettiplace, R. (2017). Hair cell transduction, tuning, and synaptic transmission in the mammalian cochlea. Compr. Physiol. 7, 1197-1227. 10.1002/cphy.c160049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garikapati, K., Ashad-Bishop, K., Hong, S., Qureshi, R., Rieger, M. E., Lindley, L. E., Wang, B., Azzam, D. J., Khanlari, M., Nadji, M. et al. (2021). LBH is a cancer stem cell- and metastasis-promoting oncogene essential for WNT stem cell function in breast cancer. bioRxiv 2021.01.29.428659. 10.1101/2021.01.29.428659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge, S. X., Son, E. W. and Yao, R. (2018). iDEP: an integrated web application for differential expression and pathway analysis of RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics 19, 534. 10.1186/s12859-018-2486-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, D. Z. Z. (1997). Relationship between the development of outer hair cell electromotility and efferent innervation: a study in cultured organ of corti of neonatal gerbils. J. Neurosci. 17, 3634-3643. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03634.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, D. Z. Z., Evans, B. N. and Dallos, P. (1994). First appearance and development of electromotility in neonatal gerbil outer hair cells. Hear. Res. 78, 77-90. 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90046-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, D. Z. Z., Jia, S., Sato, T., Zuo, J., Andrade, L. R., Riordan, G. P. and Kachar, B. (2010). Changes in plasma membrane structure and electromotile properties in prestin deficient outer hair cells. Cytoskeleton 67, 43-55. 10.1002/cm.20423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, D. Z. Z., Lovas, S., Ai, Y., Li, Y. and Beisel, K. W. (2014). Prestin at year 14: progress and prospect. Hear. Res. 311, 25-35. 10.1016/j.heares.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudspeth, A. J. (2014). Integrating the active process of hair cells with cochlear function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 600-614. 10.1038/nrn3786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, S. and He, D. Z. Z. (2005). Motility-associated hair-bundle motion in mammalian outer hair cells. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1028-1034. 10.1038/nn1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, S., Yang, S., Guo, W. and He, D. Z. Z. (2009). Fate of mammalian cochlear hair cells and stereocilia after loss of the stereocilia. J. Neurosci. 29, 15277-15285. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3231-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan, A. E. (2013). Notch signaling during cell fate determination in the inner ear. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 24, 470-479. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, A., Valerius, M. T., Mugford, J. W., Carroll, T. J., Self, M., Oliver, G. and McMahon, A. P. (2008). Six2 defines and regulates a multipotent self-renewing nephron progenitor population throughout mammalian kidney development. Cell Stem Cell 3, 169-181. 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolla, L., Kelly, M. C., Mann, Z. F., Anaya-Rocha, A., Ellis, K., Lemons, A., Palwermo, A. T., So, K. S., Mays, J. C., Orvis, J.et al. (2020). Characterization of the development of the mouse cochlear epithelium at the single cell level. Nat. Commun. 11, 2389. 10.1038/s41467-020-16113-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kros, C. J., Rüsch, A. and Richardson, G. P. (1992). Mechano-electrical transducer currents in hair cells of the cultured neonatal mouse cochlea. Proc. R. Soc. Biol. Sci. 249, 185-193. 10.1098/rspb.1992.0102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.-H., Zhou, L., Li, Z., Wang, Y., Shi, J.-T., Yang, Y.-J. and Gui, J.-F. (2015). Zebrafish Lbh-like is required for Otx2-mediated photoreceptor differentiation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 11, 688-700. 10.7150/ijbs.11244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., Liu, H., Giffen, K. P., Chen, L., Beisel, K. W. and He, D. Z. Z. (2018). Transcriptomes of cochlear inner and outer hair cells from adult mice. Sci. Data 5, 180199. 10.1038/sdata.2018.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., Liu, H., Barta, C. L., Judge, P. D., Zhao, L., Zhang, W .J., Gong, S., Beisel, K.W. and He, D.Z. (2016). Transcription factors expressed in mouse cochlear inner and outer hair cells. PLoS ONE 11, e0151291. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman, M. C., Gao, J., He, D. Z. Z., Wu, X., Jia, S. and Zuo, J. (2002). Prestin is required for electromotility of the outer hair cell and for the cochlear amplifier. Nature 419, 300-304. 10.1038/nature01059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindley, L. E. and Briegel, K. J. (2013). Generation of mice with a conditional Lbh null allele. Genesis 51, 491-497. 10.1002/dvg.22390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindley, L. E., Curtis, K. M., Sanchez-Mejias, A., Rieger, M. E., Robbins, D. J. and Briegel, K. J. (2015). The WNT-controlled transcriptional regulator LBH is required for mammary stem cell expansion and maintenance of the basal lineage. Development 142, 893-904. 10.1242/dev.110403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H., Pecka, J. L., Zhang, Q., Soukup, G. A., Beisel, K. W. and He, D. Z. Z. (2014). Characterization of transcriptomes of cochlear inner and outer hair cells. J. Neurosci. 34, 11085-11095. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1690-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H., Li, Y., Chen, L., Zhang, Q., Pan, N., Nichols, D. H., Zhang, W. J., Fritzsch, B. and He, D. Z. Z. (2016). Organ of Corti and stria vascularis: is there an interdependence for survival? PLoS ONE 11, e0168953. 10.1371/journal.pone.0168953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H., Chen, L., Giffen, K. P., Stringham, S. T., Li, Y., Judge, P. D., Beisel, K. W. and He, D. Z. Z. (2018). Cell-specific transcriptome analysis shows that adult pillar and Deiters’ cells express genes encoding machinery for specializations of cochlear hair cells. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11, 356. 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low, B. C., Pan, C. Q., Shivashankar, G. V., Bershadsky, A., Sudol, M. and Sheetz, M. (2014). YAP/TAZ as mechanosensors and mechanotransducers in regulating organ size and tumor growth. FEBS Lett. 588, 2663-2670. 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, S., Hammaker, D., Topolewski, K., Briegel, K. J., Boyle, D. L., Dowdy, S., Wang, W. and Firestein, G. S. (2017). Regulation of the cell cycle and inflammatory arthritis by the transcription cofactor LBH gene. J. Immunol. 199, 2316-2322. 10.4049/jimmunol.1700719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, T. and Vinkemeier, U. (2004). Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of STAT transcription factors. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 4606-4612. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04423.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mootha, V. K., Lindgren, C. M., Eriksson, K.-F., Subramanian, A., Sihag, S., Lehar, J., Pujgserver, P., Carlsson, E., Ridderstrale, M., Laurila, E.et al. (2003). PGC-1α-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat. Genet. 34, 267-273. 10.1038/ng1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. T. T., Park, W. S., Park, B. O., Kim, C. Y., Oh, Y., Kim, J. M., Choi, H., Kyung, T., Kim, C.-H., Lee, G.et al. (2016). PLEKHG3 enhances polarized cell migration by activating actin filaments at the cell front. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 10091-10096. 10.1073/pnas.1604720113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.-S., Ma, W., O'Brien, L. L., Chung, E., Guo, J.-J., Cheng, J.-G., Valerius, M. T., McMahon, J. A., Wong, H. W. and Mcmahon, A. P. (2012). Six2 and Wnt regulate self-renewal and commitment of nephron progenitors through shared gene regulatory networks. Dev. Cell 23, 637-651. 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raft, S. and Groves, A. K. (2015). Segregating neural and mechanosensory fates in the developing ear: patterning, signaling, and transcriptional control. Cell Tissue Res. 359, 315-332. 10.1007/s00441-014-1917-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranum, P. T., Goodwin, A. T., Yoshimura, H., Kolbe, D. L., Walls, W. D., Koh, J.-Y., He, D. Z. and Smith, R. J. H. (2019). Insights into the biology of hearing and deafness revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Cell Rep. 26, 3160-3171.e3. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.02.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger, M. E., Sims, A. H., Coats, E. R., Clarke, R. B. and Briegel, K. J. (2010). The embryonic transcription cofactor LBH is a direct target of the Wnt signaling pathway in epithelial development and in aggressive basal subtype breast cancers. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 4267-4279. 10.1128/MCB.01418-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouillard, A. D., Gundersen, G. W., Fernandez, N. F., Wang, Z., Monteiro, C. D., McDermott, M. G. and Ma'ayan, A. (2016). The harmonizome: a collection of processed datasets gathered to serve and mine knowledge about genes and proteins. Database 2016, baw100. 10.1093/database/baw100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi, J. (1991). Reversible inhibition of voltage-dependent outer hair cell motility and capacitance. J. Neurosci. 11, 3096-3110. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03096.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer, D. I., Shen, J., Corey, D. P. and Chen, Z.-Y. (2015). Gene expression by mouse inner ear hair cells during development. J. Neurosci. 35, 6366-6380. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5126-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self, M., Lagutin, O. V., Bowling, B., Hendrix, J., Cai, Y., Dressler, G. R. and Oliver, G. (2006). Six2 is required for suppression of nephrogenesis and progenitor renewal in the developing kidney. EMBO J. 25, 5214-5228. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, A., Tamayo, P., Mootha, V. K., Mukherjee, S., Ebert, B. L., Gillette, M. A., Paulovich, A., Golbu, T. R., Lander, E. S. and Mesirov, J. P. (2005). Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545-15550. 10.1073/pnas.0506580102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waqas, M., Zhang, S., He, Z., Tang, M. and Chai, R. (2016). Role of Wnt and Notch signaling in regulating hair cell regeneration in the cochlea. Front. Med. 10, 237-249. 10.1007/s11684-016-0464-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J., Liu, H., Park, J.-S., Lan, Y. and Jiang, R. (2014). Osr1 acts downstream of and interacts synergistically with Six2 to maintain nephron progenitor cells during kidney organogenesis. Development 141,1442-1452. 10.1242/dev.103283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi-Kabata, Y., Morihara, T., Ohara, T., Ninomiya, T., Takahashi, A., Akatsu, H., Hashizume, Y., Hayashi, N., Shigemizu, D., Boroevich, K. A.et al. (2018). Integrated analysis of human genetic association study and mouse transcriptome suggests LBH and SHF genes as novel susceptible genes for amyloid-β accumulation in Alzheimer's disease. Hum. Genet. 137, 521-533. 10.1007/s00439-018-1906-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, T., Zheng, F., Finkelstein, D., Kellard, Z., Carter, R., Rosencrance, C. D., Sugino, K., Easton, J., Gawad, C. and Zuo, J. (2018). High-resolution transcriptional dissection of in vivo Atoh1-mediated hair cell conversion in mature cochleae identifies Isl1 as a co-reprogramming factor. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007552. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q., Liu, H., McGee, J., Walsh, E. J., Soukup, G. A. and He, D. Z. Z. (2013). Identifying microRNAs involved in degeneration of the organ of corti during age-related hearing loss. PLoS ONE 8, e62786. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q., Liu, H., Soukup, G. A. and He, D. Z. Z. (2014). Identifying microRNAs involved in aging of the lateral wall of the cochlear duct. PLoS ONE 9, e112857. 10.1371/journal.pone.0112857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J., Shen, W., He, D. Z. Z., Long, K. B., Madison, L. D. and Dallos, P. (2000). Prestin is the motor protein of cochlear outer hair cells. Nature 405, 149-155. 10.1038/35012009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.