Abstract

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) represent the standard treatment for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations. The duration of the response is, however, limited in time owing to the development of resistance mechanisms to both first- and second-generation agents such as MET oncogene amplification. This report describes the successful results obtained with the combination of the third-generation TKI osimertinib with the multitargeted TKI and MET inhibitor crizotinib in a patient with EGFR-mutant NSCLC with emerging MET amplification with a tolerable toxicity profile.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung cancer, EGFR mutation, MET amplification, Targeted therapy

Introduction

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations are detected in approximately 10–15% of non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs), and exon 19 deletion and exon 21 p.L858R mutations account for 85–90% of the activating variants predicting the response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) [1]. Despite good initial response, acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs unavoidably occurs, with disease progression after 10–12 months from treatment initiation in the majority of patients [2]. In approximately 60% of the cases, the treatment failure of first- and second-generation EGFR inhibitors occurs due to development of the EGFR mutation p.T790M in exon 20 [3]. Third-generation TKIs such as osimertinib have been specifically designed to overcome this resistance mechanism and maintain on-target capability in spite of the presence of the T790M resistance mutation. Nonetheless, disease progression occurs within a median of 10 months when osimertinib is used as second-line treatment [4].

Multiple mechanisms leading to resistance to third-generation EGFR-TKIs have been described, such as the activation of alternative pathways, phenotypic transformation, and further EGFR alterations [2]. Amplification of the MET oncogene is an important resistance mechanism to first- and second-generation TKIs, accounting for 5–20% of acquired resistance cases in this setting [5], and has also been identified as an acquired resistance mechanism to third-generation TKIs, even when used as first-line therapy [6].

We hereby report the case of a patient diagnosed with stage IV EGFR+ NSCLC treated with combined targeted therapies for concurrent EGFR and MET alterations with a very long survival.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old never-smoking Caucasian woman presented to the emergency department with dyspnea and right-sided thoracic pain in May 2010. Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax showed a 3.5-cm pulmonary lesion of the middle lobe and pleural carcinomatosis. A CT-guided percutaneous biopsy was performed, which revealed stage IV lung adenocarcinoma. An EGFR exon 19 deletion was detected in the biopsy specimen by PCR (polymerase chain reaction) amplification and bidirectional sequencing of exons 18–21.

The patient was treated with gefitinib 250 mg daily, with the achievement of a partial response (PR) that was maintained for approximately 4 years. The treatment was well tolerated, and no clinically relevant side effects were reported. In August 2014, a thorax CT scan demonstrated progressive disease, with an increase in the size of the lung lesion, and pemetrexed was added to gefitinib, with disease stability maintained for 6 months. In May 2015, the patient received palliative radiotherapy of the thorax for symptomatic infiltration of the chest wall. She experienced progressive disease with new contralateral nodules in December 2015. A re-biopsy was performed, which revealed the resistance mutation EGFR T790M by PCR amplification and bidirectional sequencing of exon 20. Treatment with osimertinib 80 mg was started within a clinical study. Two months later, a chest CT scan showed PR with a reduction in size of the bilateral lung nodules and stability of the lesion in the middle lobe, which was maintained for approximately 2 years.

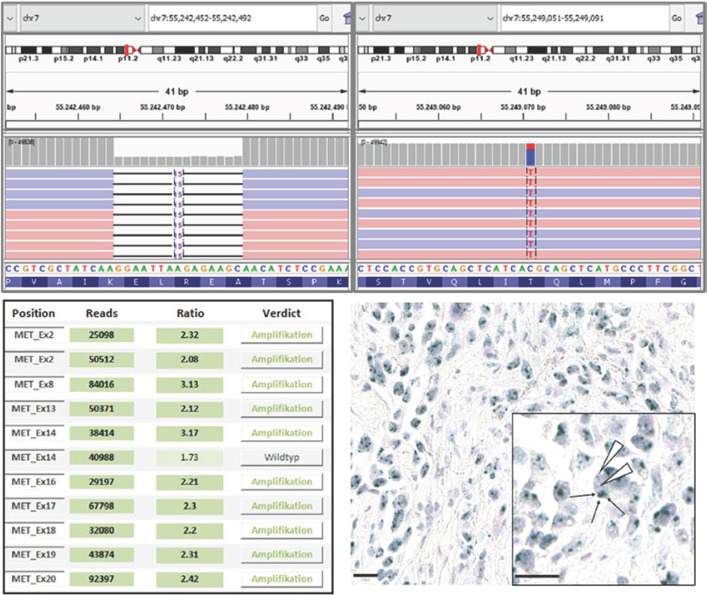

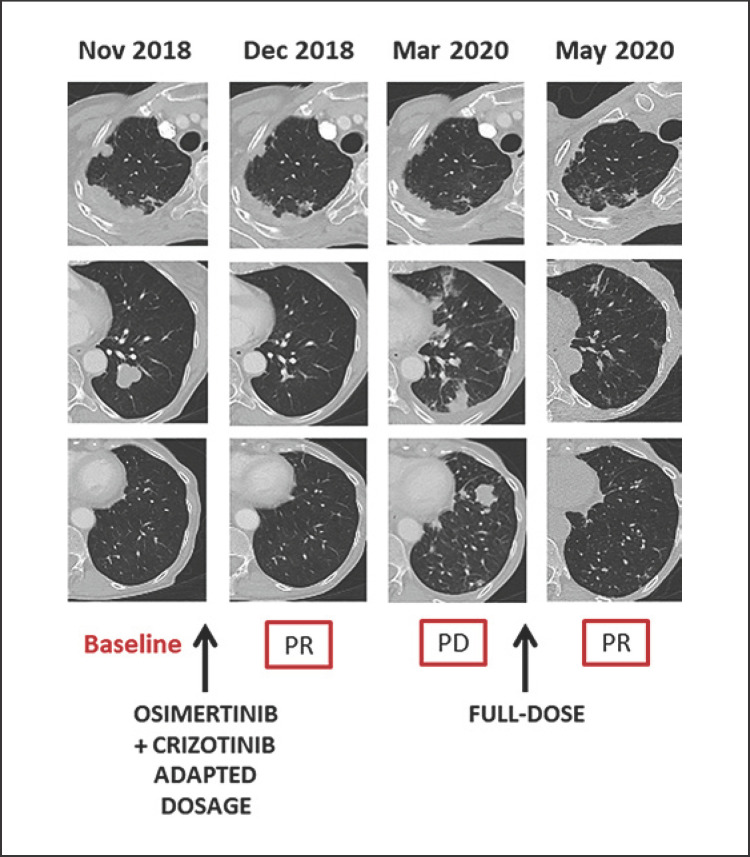

However, a chest CT scan performed in August 2018 showed an increase in the size of the middle-lobe lesion and a new re-biopsy was performed. The result of next-generation sequencing confirmed the presence of EGFR exon 19 deletion and T790M mutation and indicated a low-level amplification of MET. Confirmatory chromogenic in situ hybridization showed a clear increase in the MET signal with a clustered pattern (Fig. 1) and a 6.9 MET/CEP7 (centromeric probe of chromosome 7) ratio. Crizotinib, a multitargeted TKI inhibiting MET, ALK, and ROS1 was added to osimertinib in November 2018. Osimertinib was started at a dose of 80/40 mg on alternate days, and crizotinib at a dose of 200 mg twice a day in order to avoid unexpected drug interactions and adverse events in this patient with a very low body mass index (15 kg/m2). A CT scan after 4 weeks showed an impressive response with a complete resolution of the left lung nodules (Fig. 2). The patient experienced grade 2 fatigue, grade 2 vomiting, and decreased appetite, which improved upon reduction of the crizotinib dose to an alternate-day schedule of 200 mg twice/once daily.

Fig. 1.

Results of the molecular pathological analysis. Upper panels: IGV (Integrative Genomics Viewer) displays of the detected EGFR mutations (referred to refseq ID NM_005228); left: exon 19 deletion EGFR:p.E746_A750delELREA with a frequency of 68%; right: point mutation EGFR:p.T790M with a frequency of 29%. Lower panels: detection of the MET amplification; left: CNV analysis based on the coverage of the next-generation sequencing data; right: representative image of chromogenic in situ hybridization with a nucleic signal for the centromeric region of chromosome 7 (CEP7; red) and the MET gene locus (green). An evaluation of more than 20 tumor cells in two distinct regions of the tumor showed a clear increase in MET signals with a clustered pattern and a MET/CEP7 ratio of 6.9.

Fig. 2.

Schematic summary of the combined treatment and the clinical course.

The response was maintained until March 2020, when the patient developed dyspnea, cough, and thoracic pain and a CT scan documented bilateral thoracic progression. A re-biopsy was performed, and the known EGFR mutations and MET amplification were confirmed. No new targetable molecular alterations were reported. The patient began receiving the full-dose combination therapy with osimertinib 80 mg and crizotinib 200 mg twice daily, resulting in a rapid symptom improvement. Repeat CT scanning after 2 months showed a PR on both lungs (Fig. 2).

The patient has undergone 19 months of combination therapy. Administration of the full-dose combination was associated with grade 2 anemia, grade 2 fatigue, and grade 2 lower extremity edema, but could be sustained by the patient.

Discussion

MET amplification leads to EGFR-independent phosphorylation of ERBB3, and thereby to activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway and transmission of the same downstream signaling, bypassing the effect of EGFR inhibitors. Thus, to overcome this resistance mechanism, the concomitant inhibition of EGFR and MET is required [7]. Many preclinical studies have confirmed the role of MET amplification in the development of resistance to third-generation EGFR-TKIs, suggesting the use of MET inhibitors, alone or in combination, to overcome this mechanism [6, 8].

While no significant clinical efficacy has been demonstrated for MET receptor monoclonal antibodies, MET-TKIs have shown encouraging results. Clinical examples have demonstrated effective responses when crizotinib is added to first- or second-generation EGFR inhibitors [9, 10] as well as to osimertinib [11, 12, 13]. Among the cited examples, Zhu et al. [13] reported a sustained PR without significant toxicity after closed monitored escalation to full-dose combination treatment, while York et al. [12] described a case in which the dose escalation was associated with a clinical benefit without significant changes in tolerability except for grade 2 fatigue.

Prospective clinical trials testing the combination of third-generation EGFR inhibitors with MET- or MEK-TKIs in patients that experienced progression under EGFR-TKIs are ongoing. TATTON is a phase Ib study testing osimertinib in combination with novel therapeutics such as savolitinib in patients with EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC who have progressed on first- or second-generation EGFR-TKIs or after treatment with osimertinib or another experimental third-generation EGFR-TKI. Interim data have shown a response rate of 52% for patients who had previously received first- or second-generation TKIs and 28% for those who had previously received third-generation EGFR-TKIs, with an acceptable safety profile [14]. Based on these data, SAVANNAH, a phase II study that is further investigating osimertinib in combination with savolitinib in patients with EGFR-mutant and MET-amplified NSCLC after progression on osimertinib, is ongoing [15]. NCT02335944 is a phase Ib/II study testing the combination of capmatinib, a highly selective and potent MET inhibitor, and nazartinib, a third-generation EGFR-TKI, while the multidrug phase II platform study ORCHARD is studying different treatment modalities depending on the resistance mechanism involved in the development of resistance to first-line osimertinib, including osimertinib in combination with savolitinib, in patients with MET amplification.

Conclusions

Our case report provides further evidence of the successful administration of crizotinib in combination with osimertinib to target MET amplification-derived resistance to third-generation EGFR-TKIs in T790M+ advanced NSCLC. Reductions in the starting dosage are suggested, but escalation to the full dose has been associated with clinical benefit without significant modifications in tolerability. To our knowledge, the observed survival of 10 years after the initiation of anti-EGFR therapy is the longest that has been reported for this treatment modality so far. The impressive survival time of this patient underlines the huge potential for clinical benefit from comprehensive molecular profiling after failure of third-generation EGFR-TKIs in order to identify and target any genetic alterations causing the acquired resistance, as well as the urgent need for prospective clinical trials investigating new targeted agents and combinations in this setting.

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No financial support was used for this case report.

Author Contributions

All authors have made significant contributions to the manuscript and have reviewed it before submission. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Fang S, Wang Z. EGFR mutations as a prognostic and predictive marker in non-small-cell lung cancer. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:1595–611. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S69690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minari R, Bordi P, Tiseo M. Third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in T790M-positive non-small cell lung cancer: review on emerged mechanisms of resistance. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2016;5((6)):695–708. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2016.12.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias-Santagata D, Digumarthy S, Turke AB, Fidias P, et al. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3((75)):75ra26. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jänne PA, Yang JC, Kim DW, Planchard D, Ohe Y, Ramalingam SS, et al. AZD9291 in EGFR inhibitor-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372((18)):1689–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgillo F, Della Corte CM, Fasano M, Ciardiello F. Mechanisms of resistance to EGFR-targeted drugs: lung cancer. ESMO Open. 2016;1((3)):e000060. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2016-000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Q, Yang S, Wang K, Sun S-Y. MET inhibitors for targeted therapy of EGFR TKI-resistant lung cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12((1)):63. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0759-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, Song Y, Hyland C, Park JO, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316((5827)):1039–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mizuuchi H, Suda K, Murakami I, Sakai K, Sato K, Kobayashi Y, et al. Oncogene swap as a novel mechanism of acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor in lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2016;107((4)):461–8. doi: 10.1111/cas.12905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng X, Zhang G, Li P, Zhang M, Yan X, Zhang X, et al. Mutation tracking of a patient with EGFR-mutant lung cancer harboring de novo MET amplification: successful treatment with gefitinib and crizotinib. Lung Cancer. 2019;129:72–4. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Zhang R, Zhou Y, Song J, Luo W, Tian P, et al. Combined use of crizotinib and gefitinib in advanced lung adenocarcinoma with leptomeningeal metastases harboring MET amplification after the development of gefitinib resistance: a case report and literature review. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019;20((3)):e251–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ou SI, Agarwal N, Ali SM. High MET amplification level as a resistance mechanism to osimertinib (AZD9291) in a patient that symptomatically responded to crizotinib treatment post-osimertinib progression. Lung Cancer. 2016;98:59. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.York ER, Varella-Garcia M, Bang TJ, Aisner DL, Camidge DR. Tolerable and effective combination of full-dose crizotinib and osimertinib targeting MET amplification sequentially emerging after T790M positivity in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12((7)):e85–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu VW, Schrock AB, Ali SM, Ou S-HI. Differential response to a combination of fulldose osimertinib and crizotinib in a patient with EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer and emergent MET amplification. Lung Cancer Targets Ther. 2019;10:21–6. doi: 10.2147/LCTT.S190403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sequist LV, Lee JS, Han J-Y, Su W-C, Yang JC-H, Yu H, et al. Abstract CT033: TATTON phase Ib expansion cohort: osimertinib plus savolitinib for patients (pts) with EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified NSCLC after progression on prior third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) Cancer Res. 2019;79((13 Suppl)):CT033. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oxnard GR, Cantarini M, Frewer P, Hawkins G, Peters J, Howarth P, et al. SAVANNAH: a phase II trial of osimertinib plus savolitinib for patients (pts) with EGFR-mutant, MET-driven (MET+), locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), following disease progression on osimertinib. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:TPS9119. [Google Scholar]