Abstract

Introduction

The prognosis of patients undergoing transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is extremely variable, and a confounding factor is that TACE is often repeated several times. We retrospectively evaluated the accuracy of different prognostic scores and staging systems in estimating overall survival (OS) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Methods

An analysis considering prognostic models as time-varying variables was performed, calculating OS from the time of TACE to the time of the subsequent treatment. Total follow-up time for each patient was therefore split into several observation times accounting for each TACE procedure. Values of the likelihood ratio test (LRT) and Akaike information criterion (AIC) were used to compare different systems. Univariable and multivariable analyses were conducted to identify additional factors predictive of OS. We analyzed 1,610 TACE performed in 1,058 patients recorded in the Italian Liver Cancer database from 2008 through 2016.

Results

The median OS of the enrolled patients was 41 months. According to LRT χ<sup>2</sup> and AIC values based on the time-varying analysis, mHAP-III achieved the best values (41.72 and 4,625.49, respectively, p < 0.0001), indicating the highest predictive performance compared with all other scores (HAP, mHAP-II, ALBI, and pALBI) and staging systems (MELD, ITALICA, CLIP, MESH, MESIAH, JIS, HKLC, and BCLC). In the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model, mHAP-III maintained an independent effect on OS (hazard ratio 1.31, 95% CI: 1.10–1.55, p < 0.0001). Time-varying age, alcoholic etiology, radiologic response to TACE, and performing ablation or surgery after TACE were additional significant variables resulting from the multivariable model.

Conclusion

An innovative time-varying analysis revealed that mHAP-III was the most accurate model in predicting OS in patients with HCC undergoing TACE. Other clinical pre- and post-TACE variables were also found to be relevant for this prediction.

Keywords: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, ITALICA staging system, ALBI grade, MESIAH, Cancer of the Liver Italian Program

Introduction

Primary liver cancer is the fifth most common cancer worldwide and one of the most frequent causes of cancer-related death [1]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for about 90% of these tumors [1]. As for any tumor, staging plays an important role to prognosticate and manage HCC [2]. However, because >80% of HCC develops in patients with cirrhosis, prognosis and management of this cancer must take into account the severity of the underlying liver dysfunction. Over the years, various staging systems have been proposed to overcome the limitations affecting the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) system, which only consider tumor burden [3]. One of the most widely used staging systems for HCC is the Barcelona Clinic Liver Classification (BCLC), which includes variables related to tumor status, liver function, and performance status, also indicating a specific treatment modality for each stage of the disease [4]. In particular, patients belonging to the BCLC-B (intermediate) stage are recommended to be treated with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE). However, the intermediate stage includes a remarkably heterogeneous population, and several recent efforts to subclassify this group of patients according to tumor burden and liver function have been proposed, in an attempt to optimize their management and individuate the actual treatment benefit [5, 6, 7, 8]. Moreover, common clinical practice in both the Western and Eastern world shows that HCC may be frequently treated with TACE even when a patient belongs to a BCLC stage other than the intermediate one [9, 10, 11], and particularly BCLC-A patients not amenable to curative treatments. Indeed, the latest version of the EASL guidelines accepts the strategy called “therapeutic stage migration” recommending that whenever a patient cannot be treated with the stage-specific treatment (e.g., surgery or thermal ablation for stage A), or when this fails, he/she should undergo the treatment recommended for the subsequent stage [2]. Additionally, the approach to HCC patients based on the concept of “therapeutic hierarchy” expands the use of TACE to well-selected patients belonging to stage C [10, 11, 12]. As a result, in clinical practice, patients undergoing TACE form a very heterogeneous population, belonging to different cancer stages. This scenario, together with the variable response to TACE, makes their prognosis extremely dissimilar. Therefore, various pre- and posttreatment prognostic models, aimed at identifying patients who are more likely to have a valuable survival benefit from TACE, have been generated. Some of them, like the albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade, only take into account liver dysfunction, excluding any tumor features [13, 14], and other models are specifically dedicated to the TACE setting [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21]. In spite of considerable efforts, several questions concerning the management of patients with TACE remain open. Specifically, no studies have compared the performance of the ALBI model with that of “TACE-dedicated” systems in a large group of patients, and the possible additional information over the one conveyed by the available prognostic models is lacking. Moreover, in all published studies, survival was evaluated without taking into account the impact of post-TACE treatments which, in some cases, could be also hierarchically superior to TACE (e.g., liver transplantation, resection, or ablation), leading to a great overestimation of the benefit of TACE. In this study, we carried out a novel analysis considering prognostic scores as time-varying variables and calculated overall survival (OS) from the time of each TACE to the time of the subsequent treatment (additional TACE or alternative therapies) with the addition of the conclusive period on best supportive care, to compare the accuracy of the available scoring/staging systems in predicting OS in a large group of patients undergoing TACE.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the Italian Liver Cancer (ITA.LI.CA) database, which collects data from patients with HCC enrolled consecutively in 24 Italian centers. The inclusion criterion was to have undergone at least one TACE procedure between January 2008 and December 2016 (the date of the last database update) and the report of the related radiologic response. We excluded patients undergoing TACE before 2008, considering the improved results observed in TACE-treated patients over time [22]. Exclusion criteria were age <18 years, Child-Pugh score >7, diuretic-resistant ascites, tumor invasion of main portal branches or biliary tree, hepatofugal portal blood flow, and extrahepatic tumor spread. Nevertheless, 31 (out of 1,058) patients were found to have distant metastases, misinterpreted or missed at the pre-TACE evaluation. HCC was diagnosed histologically or through imaging techniques (magnetic resonance imaging and/or triphasic computed tomography) according to the version of EASL guidelines available at the time of diagnosis. Age, blood chemistries, tumor characteristics (tumor size and number, macrovascular invasion, and extrahepatic spread), and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) were evaluated before each TACE procedure. At the same time points, the following prognostic classes were calculated: hepatoma arterial embolization (HAP) [15], modified hepatoma arterial embolization II (mHAP-II) [16], modified hepatoma arterial embolization III (mHAP-III) [17], ALBI [13], platelet-albumin-bilirubin (pALBI) [23], model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) [24], and Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CPT) [25]. Moreover, patients were allocated to the pertinent stages of the following staging systems: BCLC [4], ITA.LI.CA [26], Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) [27], MESH [28], Model to Estimate Survival In Ambulatory HCC patients (MESIAH) [29], Japan Integrated Staging system (JIS) [30], and Hong Kong Liver Cancer (HKCL) [31]. Decision to perform a TACE was taken by the local multidisciplinary team of each center, and a selective or superselective procedure was used whenever feasible. We included both conventional, lipiodol-based, TACE and TACE with drug-eluting beads. Patients undergoing transarterial embolization were excluded. The outcome of TACE was categorized as follows: complete response, partial response, stable disease, or progressive disease [32]. Procedures different from TACE were analyzed considering both their timing (before or after TACE) and whether they were considered hierarchically superior (transplant, resection, and ablation), equal (radioembolization), or inferior (systemic treatment and best supportive care) to TACE [10].

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as median and interquartile ranges and categorical variables as number and percentages. The missing data for the study covariates, which can comprise up to 10% of patients, were estimated using the maximum likelihood estimation method [33]. The OS was calculated from the date of initial TACE procedure to the date of death or last follow-up visit, and patients were censored at December 31, 2016. Follow-up was censored at the time of liver transplant. Since only a small portion of patients (71, 6.7%) underwent transplant after TACE, this limited number of censored patients had a minimal effect on survival analysis. Kaplan-Meier estimator survival curves and log-rank tests were used to evaluate and compare OS. We carried out a time-varying survival analysis to compare the prognostic accuracy of the different scores and staging systems in predicting OS. In the time-varying analysis, we accounted for each distinct TACE treatment the patient received. In this way, the total follow-up time for each patient was split into several observation periods accounting for each TACE treatment. Before each TACE, patients were restaged so that all reassessed variables (i.e., liver function, tumor characteristics, and therapy) were studied as time-varying parameters. This methodology allows us to test the accuracy of prognostic models not only at the start of TACE treatment but also at any time of the patient history. An example of the time-varying survival analysis is shown in online suppl. Fig. 1; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000513404. Likelihood ratio test (LRT) and Akaike information criterion (AIC) values were used to compare different scoring and staging systems. Lower AIC and higher likelihood ratio values indicate better prognostic discrimination ability of a given staging/scoring system. We also performed univariable and multivariable survival analyses using a time-varying Cox proportional hazards model. Covariates for time-varying models were chosen if the p value was <0.15 in univariable analyses. A 2-sided p value of <0.05 was defined to be considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed in JMP® 9.0.1 package (1989–2010 SAS Institute Inc.), STATA 13.0 (Copyright 1985–2013 StataCorp LP), and R.app GUI 1.51 (S. Urbanek & H.-J. Bibiko, © R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2012).

Results

Patient Characteristics

We analyzed 1,610 TACE procedures performed in 1,058 patients. Age at HCC diagnosis, gender, and clinical characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. Most of the patients were in the seventh or eighth decade of life, and 1,367 procedures were performed in patients aged over 60. The median age was 71 years, and more than two-thirds of patients were male. The most common cause of liver disease was hepatitis virus C (HCV) infection, followed by alcohol use disorder, hepatitis virus B (HBV) infection, and NASH. Because the time-varying analysis relies on data collected before each TACE procedure, we reported tumor characteristics and biochemical parameters related to all the 1610 TACE procedures (shown in Table 2). At the time of each procedure, >90% of patients belonged to Child-Pugh class A, and the MELD score was ≤10 in >80% of cases. Nearly all patients (98%) had a preserved ECOG PS, being 0 in most cases and 1 in approximately one-fifth of patients. According to the Italian guidelines for HCC management, a PS = 1 was not considered per se sufficient to allocate the patient to BCLC stage C [12, 34]. The distribution across BCLC stages showed that the intermediate stage (BCLC-B) was the most represented. Nevertheless, the antecedent stages accounted for a large proportion of cases, and TACE was sometimes utilized even in the advanced stage. For the purpose of analysis, the 3 patients with a PS = 3 were considered belonging to the BCLC-C group. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) values were highly variable, with values >400 ng/mL in one-third of patients and >1,000 ng/mL in 15% of cases. Regarding tumor features, patients were almost equally distributed among the subsets we created according to the number of lesions (single, double, and multifocal).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 1,058 patients enrolled in the study

| Variable | Median (IQR) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at first TACE procedure, years | 71 (12) |

| Age at diagnosis, years | 69 (13) |

| Gender (male) | 809 (76) |

| Etiology of chronic liver disease | |

| HBV | 123 (11.6) |

| HCV | 655 (61.9) |

| Alcohol | 312 (29.4) |

| NASH | 47 (4.4) |

| Bilirubin, mg/dL | 1.1 (0.66) |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.58 (0.55) |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 113 (48) |

| Alpha-fetoprotein, ng/mL | 62.8 (527.3) |

| Patients with encephalopathy | 12 (1.1) |

| Diameter of the largest tumor, mm | 32.4 (20) |

| Tumor characteristics | |

| Monofocal | 444 (42.0) |

| Bifocal | 341 (32.2) |

| Multifocal | 273 (25.8) |

| Portal vein thrombosis | |

| Present | 57 (5.3) |

| Absent | 1,001 (94.7) |

| Extrahepatic spread | |

| Present | 20 (1.9) |

| Absent | 1,038 (98.1) |

| Performance status | |

| Grade 0 | 858 (81.1) |

| Grade 1 | 173 (16.3) |

| Grade 2 | 24 (2.3) |

| Grade 3 | 3 (0.3) |

| Child-Turcotte-Pugh class | |

| A | 965 (91.2) |

| B | 93 (8.8) |

| MELD score | 9 (2) |

| TACE, n | |

| 1 procedure | 697 (66.0) |

| 2 procedures | 232 (21.9) |

| 3 procedures | 91 (8.6) |

| 4 procedures | 21 (2.0) |

| 5 procedures | 12 (1.1) |

| 6 procedures | 3 (0.2) |

| 7 procedures | 2 (0.2) |

Some of the patients had >1 etiologic factor. HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study group

| Variable | Median (IQR) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Bilirubin, mg/dL | 1.03 (0.71) |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.57 (0.55) |

| Platelet count, × | 113 (48) |

| Alpha-fetoprotein, ng/mL | 64.6 (527.4) |

| Presence of encephalopathy | 18 (1.1) |

| Maximum tumor diameter, cm | 2.9 (1.5) |

| Tumor characteristics | |

| Monofocal | 643 (39.9) |

| Bifocal | 543 (33.7) |

| Multifocal | 424 (26.4) |

| Portal vein thrombosis | |

| Present | 122 (7.6) |

| Absent | 1,488 (92.4) |

| Extrahepatic spread | |

| Present | 31 (1.9) |

| Absent | 1,579 (98.1) |

| Performance status | |

| 0 | 1,271 (78.9) |

| 1 | 300 (18.6) |

| 2 | 35 (2.2) |

| 3 | 4 (0.3) |

| Child-Turcotte-Pugh class | |

| A | 1,475 (91.6) |

| B | 135 (8.4) |

| MELD score | 9 (2) |

| BCLC stage | |

| 0 | 178 (11.1) |

| A | 569 (35.3) |

| B | 716 (44.5) |

| C | 147 (9.1) |

1,610 procedures were performed in 1,058 patients. The table reports the characteristics of the patients at the time of each procedure. Therefore, data from the same patient may have been included >1 time. BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease.

Distribution across Categories for Prognostic Scoring and Staging Systems

Approximately 80% of patients belonged to the ALBI grade 2, while almost all the remainders were ALBI grade 1 (shown in Table 3). Similarly, most patients were in grade 2 of pALBI. Conversely, patients were more homogeneously distributed across the different HAP and mHAP-II categories. Because the mHAP-III score is continuous, we reported the distribution of patients in quartiles, providing the relative intervals (shown in Table 3). The distribution of patients according to the HCC staging systems is shown in Table 4. Patients were homogeneously distributed in all 4 groups of the ITALICA staging system, while >90% belonged to the classes 0–2 for the CLIP and MESH systems. MESIAH and MELD distribution was also divided in quartiles with relative intervals (shown in Table 4). Approximately 90% of patients were concentrated in stages 0–2 for JIS and in classes I–II for HKCL.

Table 3.

Distribution of patients in the different prognostic models at the time of each procedure

| ALBI grade, n (%) | |

| Grade 1 | 295 (18.3) |

| Grade 2 | 1,272 (79) |

| Grade 3 | 43 (2.7) |

| pALBI grade, n (%) | |

| Grade 1 | 446 (27.7) |

| Grade 2 | 956 (59.4) |

| Grade 3 | 208 (12.9) |

| HAP class, n (%) | |

| Class A | 680 (42.2) |

| Class B | 561 (34.8) |

| Class C | 341 (21.2) |

| Class D | 28 (1.8) |

| mHAP-II class, n (%) | |

| Class A | 394 (24.5) |

| Class B | 632 (39.2) |

| Class C | 430 (26.7) |

| Class D | 154 (9.6) |

| mHAP-III | |

| Minimum value | −1.5478 |

| 1st quartile | −0.3438 |

| Median | 0.0294 |

| 3rd quartile | 0.4444 |

| Maximum value | 6.9163 |

1,610 procedures were performed in 1,058 patients. The table reports the distribution of patients at the time of each procedure. Therefore, data from the same patient may have been included >1 time. ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; pALBI, platelet-albumin-bilirubin; HAP, hepatoma arterial embolization; mHAP-II, modified hepatoma arterial embolization II; mHAP-III, modified hepatoma arterial embolization III.

Table 4.

Distribution of patients in the different staging systems at the time of each procedure

| MELD | Points |

| Minimum value | 6 |

| 1st quartile | 8 |

| Median | 9 |

| 3rd quartile | 10 |

| Maximum value | 29 |

| ITA.LI.CA, n (%) | |

| 0–1 | 307 (19.1) |

| 2 | 395 (24.5) |

| 3 | 433 (26.9) |

| ≥4 | 475 (29.5) |

| CLIP, n (%) | |

| 0 | 470 (29.2) |

| 1 | 633 (39.3) |

| 2 | 436 (27.1) |

| 3 | 65 (4.1) |

| 4 | 6 (0.3) |

| 5 | 0 (0) |

| MESH, n (%) | |

| 0 | 394 (24.5) |

| 1 | 682 (42.4) |

| 2 | 396 (24.6) |

| 3 | 122 (7.5) |

| 4 | 15 (0.9) |

| 5 | 1 (0.1) |

| MESIAH | |

| Minimum value | 3.759 |

| 1st quartile | 5.222 |

| Median | 5.641 |

| 3rd quartile | 6.032 |

| Maximum value | 8.876 |

| JIS, n (%) | |

| 0 | 155 (9.6) |

| 1 | 603 (37.5) |

| 2 | 743 (46.2) |

| 3 | 105 (6.5) |

| 4 | 4 (0.2) |

| 5 | 0 (0) |

| HKCL, n (%) | |

| I | 888 (55.2) |

| IIa | 281 (17.4) |

| IIb | 243 (15.1) |

| IIIa | 29 (1.8) |

| IIIb | 65 (4.1) |

| IVa | 56 (3.5) |

| IVb | 8 (0.5) |

| Va | 30 (1.8) |

| Vb | 10 (0.6) |

1,610 procedures were performed in 1,058 patients. The table reports the distribution of patients at the time of each procedure. Therefore, data from the same patient may have been included >1 time. ITA.LI.CA, Italian Liver Cancer; CLIP, Cancer of the Liver Italian Program; MESH, model to estimate survival for hepatocellular carcinoma; MESIAH, Model to Estimate Survival In Ambulatory HCC patients; JIS, Japan Integrated Staging system; HKLC, Hong Kong Liver Cancer.

Treatments after TACE

Four hundred and sixty-four of the 1,058 patients included in the study had further treatments after TACE. Considering treatments hierarchically superior to TACE [10], 40 patients (3.8%) underwent percutaneous ethanol injection, 2 patients (0.2%) surgical resection, and 40 patients (3.8%) ablative therapies (comprising radiofrequency, laser, or microwave ablation). Seventy-one patients (6.7%) received TACE as a bridge to liver transplantation. As far as treatments hierarchically inferior to TACE are concerned, 248 (23.4%) of the 1,058 patients received a systemic treatment after TACE, 16 patients (1.5%) were treated with external radiation therapy, 13 (1.2%) with radioembolization, and 88 (8.3%) with other treatments not specified in the database.

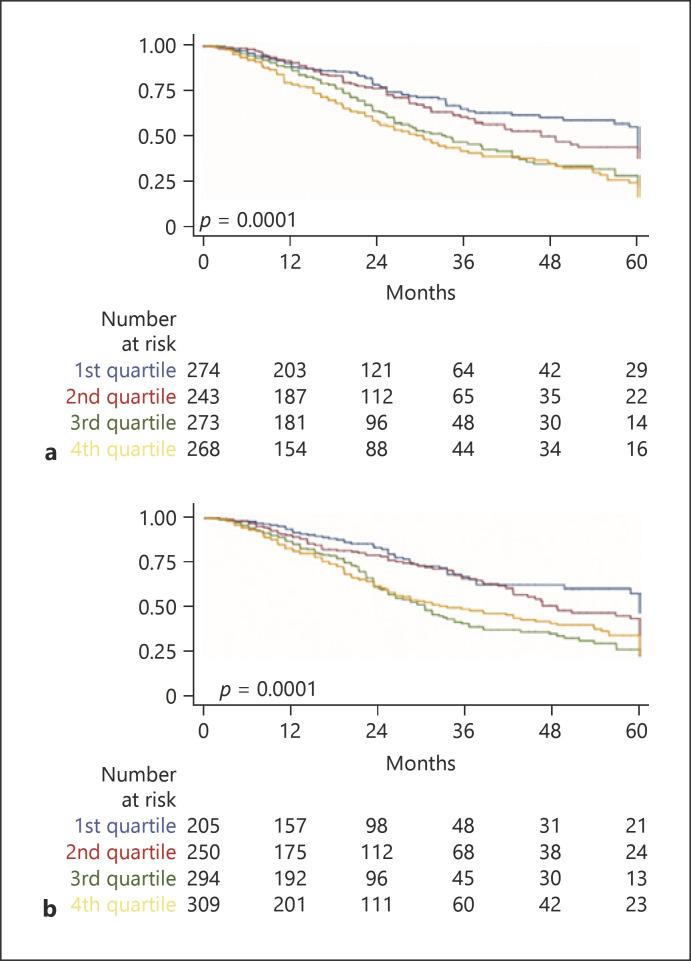

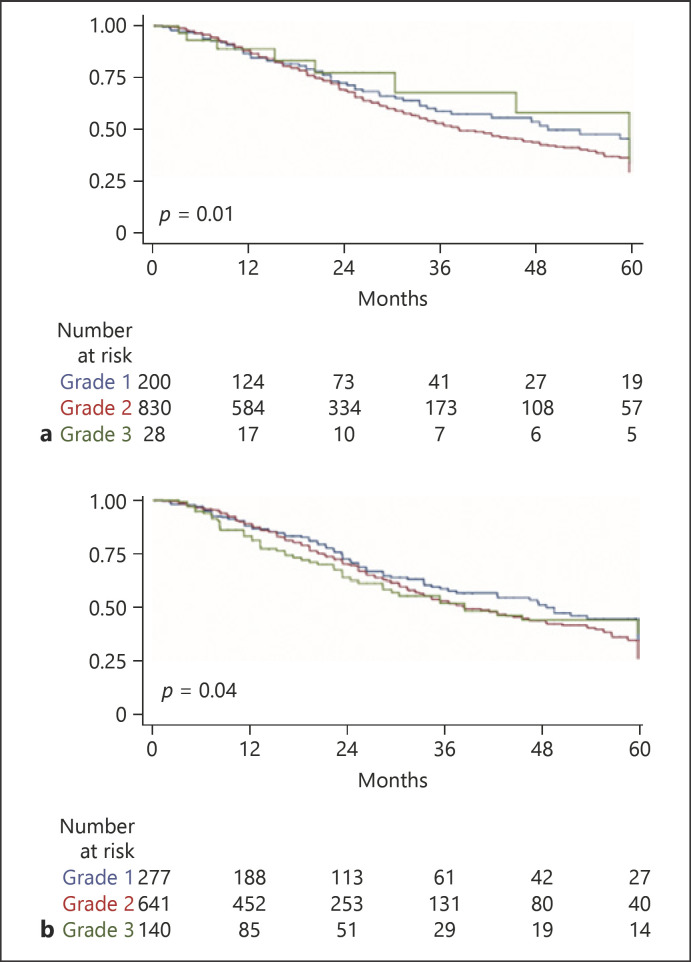

Prediction of Survival

Considering the 1,058 patients, the median OS was 41 months (IQR 26–109). Pretreatment scores and staging systems were tested applying a time-varying survival analysis accounting for each TACE procedure (see Experimental Procedures). Survival according to the stages was significantly different for mHAP-III (shown in Fig. 1a), ITALICA (shown in Fig. 1b), ALBI (shown in Fig. 2a), pALBI (shown in Fig. 2b), and HAP and mHAP-II (not shown). Similarly, the different classes of Child-Pugh score, MELD, ITA.LI.CA, CLIP, MESH, MESIAH, JIS, and HKCL were associated with different survival times.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve representing the discrimination ability of mHAP-III (a) or the ITALICA staging system (b) on survival of 1,058 patients subjected to TACE for hepatocellular carcinoma 141 × 202 mm (96 × 96 DPI). TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; mHAP-III, modified hepatoma arterial embolization III.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve representing the discrimination ability of the ALBI grade (a) or pALBI (b) on survival of 1,058 patients subjected to TACE for hepatocellular carcinoma 138 × 201 mm (96 × 96 DPI). TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; pALBI, platelet-albumin-bilirubin.

Comparison between Pretreatment Prognostic Models

The prognostic performance of each pretreatment score or system was evaluated with the LRT χ2 and AIC values (shown in Table 5). The mHAP-III achieved the highest χ2 and lowest AIC values, testifying the best predictive performance among all models. Good performance values were also obtained analyzing complex staging systems not dedicated to TACE, such as ITA.LI.CA, CLIP, JIS, MESIAH, and MESH. In contrast, most prognostic scores did not show good performances. The time-varying univariable analysis showed an association between OS and the following variables not included in the prognostic model: age (p = 0.041), alcoholic etiology (p = 0.099), platelet count (p = 0.072), radiologic response (p = 0.000), and main post-TACE treatment (p = 0.000). The solidity of each prognostic model was tested by including these variables and the model in the time-varying multivariable Cox proportional hazards model. While mHAP-III maintained an independent effect on OS (shown in Table 6), all other prognostic models were not independently associated with the OS adjusted for the above mentioned pre- and post-TACE variables. Other independent prognosticators were age, alcoholic etiology, radiologic response to TACE, and performing curative treatments (liver transplantation, surgery, or ablation) after TACE.

Table 5.

Performance of each score in the prediction of survival after TACE

| Model | LRT χ2 | AIC |

|---|---|---|

| mHAP-III | 41.72 | 4,625.49 |

| ITA.LI.CA | 40.39 | 4,642.82 |

| JIS | 33.48 | 4,639.73 |

| MESIAH | 33.41 | 4,633.80 |

| CLIP | 30.89 | 4,642.32 |

| MESH | 22.35 | 4,646.86 |

| mHAP-II | 22.15 | 4,649.06 |

| HAP | 20.57 | 4,650.64 |

| HKLC | 20.21 | 4,660.99 |

| BCLC | 18.72 | 4,652.49 |

| MELD | 5.52 | 4,661.69 |

| pALBI | 4.42 | 4,664.79 |

| ALBI | 1.95 | 4,667.26 |

| CTP | 1.39 | 4,667.82 |

LRT χ2 and AIC values were used to compare different scoring and staging systems. Lower AIC and higher likelihood ratio values indicate better prognostic discrimination ability of a given staging/scoring system. TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; LRT χ2, likelihood ratio test; AIC, Akaike information criterion; mHAP-III, modified hepatoma arterial embolization III; ITA.LI.CA, Italian Liver Cancer; MESIAH, Model to Estimate Survival In Ambulatory HCC patients; JIS, Japan Integrated Staging system; CLIP, Cancer of the Liver Italian Program; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; MESH, model to estimate survival for hepatocellular carcinoma; mHAP-II, modified hepatoma arterial embolization II; HKLC, Hong Kong Liver Cancer; HAP, hepatoma arterial embolization; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; PALBI, platelet-albumin-bilirubin; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh.

Table 6.

Independent predictors of survival after TACE as evaluated by multivariable analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model

| HR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mHAP-III (per class) | 1.31 | 1.10–1.55 | 0.000 |

| Age-tv (per 1 year) | 1.02 | 1.01–1.03 | 0.003 |

| Alcoholic etiology | 1.26 | 1.02–1.57 | 0.037 |

| Radiologic response | |||

| Complete response | Ref. | ||

| Partial response | 1.87 | 1.45–2.41 | 0.000 |

| Stable disease | 1.99 | 1.29–3.07 | 0.002 |

| Progressive disease | 2.81 | 2.09–3.78 | 0.000 |

| Main post-TACE treatment (curative) | 0.44 | 0.33–0.59 | 0.000 |

TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; mHAP-III, modified hepatoma arterial embolization III; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; tv, time-varying variable; main post-TACE treatment, patients who underwent liver transplantation, ablation, or surgery after TACE.

Discussion

TACE is the most commonly used modality for the treatment of HCC [35]. Guidelines recommend this treatment for the intermediate (BCLC-B) stage, but its wide application across nearly all HCC stages and the heterogeneity of BCLC-B patients make it difficult to identify the patients who more likely benefit from the procedure, and to estimate the possible survival advantage afforded by TACE. Over the last few years, this has stimulated the creation of a number of prognostic scores for patients undergoing this therapy. However, they all derive from analyses which consider survival after the first TACE procedure, regardless of post-TACE treatments that patients may have received. Indeed, important confounding factors derive from the fact that TACE is often repeated several times and the patient may have subsequently received treatments which are hierarchically superior to TACE. For example, this is the case of a patient undergoing thermal ablation after cancer debulking with TACE or, even more dramatically, if he/she undergoes transplantation or resection after downstaging with TACE. No available studies have been designed to capture these peculiarities related to sequential HCC management. In the present study, we used, for the first time in the setting of TACE for HCC, a time-varying analysis that takes into account the prognostic score/stage recalculated before each procedure and considers the sum of these survival intervals to determine the benefit of TACE. Time-varying analysis appears to be more appropriate to assess the OS in a disease like HCC, where the sequential use of different treatment modalities is very common. As most HCCs develop in a cirrhotic liver, cirrhosis itself is a major hurdle in the prognostic assessment and management of patients because both the therapeutic decision and its outcome are conditioned by the residual liver function. For these reasons, the TNM classification, the main staging system used in oncology, is not appropriate for HCC. Thus, we evaluated the prognostic performances not only of systems that take into account tumor characteristics together with indicators of liver function but also of systems that uniquely assess liver function, such as the ALBI grade. Using the time-varying approach, the TACE-dedicated mHAP-III score emerged as the best predictor of survival after this procedure. Such a model is the latest modification of the original HAP score, which classifies patients in 4 groups based on albumin, bilirubin, AFP, and tumor size [15]. Patients in groups C and D had a poor prognosis, and, importantly, they showed a higher benefit from systemic therapy or supportive care than from TACE. In 2015, Park developed the mHAP-II score, adding to the same variables the number of tumors. Even mHAP-II identifies 4 risk groups (A-D) with different prognosis after TACE [16]. The last modification of the HAP score, named mHAP-III, was proposed by Cappelli et al. [17] in 2016 and relies on the same parameters of mHAP-II, but managed as continuous variables except for the number of tumors, which is analyzed as dichotomic variable. The reasons for the highest accuracy of mHAP-III could rely on the fact that this model includes parameters related to liver function, tumor burden, tumor aggressiveness (AFP), and a calibration of its components as continuous, instead of dichotomized, variables. This advantage can be exemplified considering that using mHAP-II, a patient with an HCC of 20 cm and albumin 2.1 mg/dL would have received the same points as a patient with a tumor of 6 cm and 3.5 mg/dL albumin. ALBI and pALBI are 2 scores proposed to overcome the limitations of the CPT score in assessing liver function [13, 14, 23]. In CPT class A, ALBI succeeded in distinguishing 2 prognostic subgroups, ALBI grade 1 and ALBI grade 2, with a 10-month difference in survival. More recently, Pinato et al. [18] validated the prognostic role of the ALBI grade across all BCLC stages. In pALBI, platelet count was added to include a surrogate marker of portal hypertension, and this prognostic model was proposed for CPT-A patients undergoing TACE [23]. However, these 2 scores did not perform very well in our TACE series, and the reason for this poor performance could rely on the fact that most (nearly 80%) of our patients belonged to ALBI grade 2. The same considerations apply to pALBI, the performance of which was nearly identical to the one of ALBI. Therefore, despite the promising results reported by other groups, ALBI and pALBI do not appear to be suitable tools to stratify candidates to TACE. We also evaluated the predictive ability of non-TACE-dedicated staging systems containing indicators of liver function. As already mentioned, the BCLC system indicates TACE as front-line treatment for BCLC-B patients. However, the BCLC-B box contains a considerably heterogeneous population in terms of liver function and tumor burden, making it possibly a highly variable outcome of this therapy. Indeed, the prognostic performance of BCLC was fairly poor in our study. Another pertinent consideration is that in clinical practice, TACE is performed in patients belonging to different BCLC stages, either as a result of a treatment stage migration (e.g., for a patient in whom resection or thermal ablation is unfeasible) or because of the preference/availability of the center. This habit was once more testified by our study, where the number of patients belonging to the BCLC-A and BCLC-B stages was comparable, yielding a stage distribution that can explain the excellent median OS of our patients. Similarly, in a large group of patients who received care through the Veterans Administration, TACE was the preferred treatment modality for BCLC-A patients [9]. Other staging systems, such as MESIAH (partitioned in quartiles) and ITA.LI.CA, performed better than BCLC, possibly because they offer a more complete assessment of the patient, including an indicator of tumor aggressiveness, like AFP. Moreover, the ITA.LI.CA staging system had the second highest χ2 and a low AIC value, confirming the excellent prognostic accuracy of this model. In 2014, Hucke et al. [20] proposed the “START strategy” to identify the best candidates for multiple TACE sessions. However, the accuracy of START model could not be examined in our study, since it includes serial measurements of C-reactive protein, not available in a sufficient proportion of our patients. Also, we could not consider the recent SNAVCORN score [21] because it includes the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, not systematically recorded in the ITA.LI.CA database. To our knowledge, the comparison of the performances of prognostic models in the setting of TACE is still largely unexplored. In fact, this topic has been addressed by a single-center study, including a small number of patients, that demonstrated the superiority of MESH over HAP, mHAP, JIS, and TNM [36]. Moreover, great caution should be applied in generalizing its results because only patients with HBV-related cirrhosis were enrolled and most of them belonged to the BCLC-C stage. In a multicenter study, Park et al. [37] evaluated the prognostic value of 3 HAP-related scores (HAP, mHAP, and mHAP-II) before the first and second round of TACE in 619 patients, showing that mHAP-II had the greatest accuracy in predicting OS. However, also this study included Asian patients, two-thirds of whom had chronic HBV infection. Remarkably, our multicentric study included >1,000 patients with different cancer stages and different forms of chronic liver disease, among which HCV infection prevailed. The identification of mHAP-III as the best predictor of the outcome of TACE suggests that the good performance of this score should be validated by prospective studies recruiting an appropriate number of patients. Moreover, the identification of other independent prognosticators beside mHAP-III, such as age, alcoholic etiology, radiologic response to TACE, and post-TACE curative treatments, could be the background for the development of a novel and more efficient score starting from the mHAP-III one.

Some limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. As for all studies based on the ITA.LI.CA database, the present one is retrospective, making it impossible to exclude that unintended biases affected its results. Additionally, the patient management was not a priori standardized among participating centers and it is plausible that it was not uniform across them. However, this element, together with the high number of enrolled patients, implies that the observed performances of prognostic models may be confidently considered valid for our nationwide clinical practice. Conversely, as the number of non-Caucasian patients was extremely low, the validity of our results cannot be extrapolated to different ethnic populations. In conclusion, among the large number of tested models, mHAP-III showed the best accuracy in predicting OS of HCC patients undergoing TACE. Other clinical features were also found to be relevant for this prediction. These data emphasize the importance of including not only tumor characteristics and liver function tests but also age, response to treatment, and potential amenability to post-TACE curative therapies in order to assemble an optimal model measuring the survival benefit provided by TACE.

Statement of Ethics

The ITA.LI.CA database management conforms to the current Italian legislation on patient confidentiality, and its assembly and related retrospective studies were approved by all participating institutions (approval of the permanent ITA.LI.CA registry released on May 15, 2012, Protocol No. 99/2012/O/Oss; local study approval ref. CEAVC 14555). This study conforms to the ethics guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients or their guardians provided written informed consent to having their data recorded in an anonymous way in the ITA.LI.CA database.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors report the following conflicts of interest related to the present work: Francesco Tovoli: consultant for Bayer and LaForce Guerbet. Fabio Marra: consultant for Bayer, Ipsen, and Eisai and received travel support from Bayer.

Funding Sources

This work was supported in part by grants from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) and from the University of Florence, to F.M.

Author Contributions

C.C. and A.V. equally contributed to the present study and are joint first authors. F.T. and F.M. equally contributed to the present study and are joint senior authors. G.D., U.A., G.L., U.C., E.G.G., F.T., G.L.R., M.D.M., E.C., M.Z., R.S., G.C., A.M., M.G., A.G., G.S.B., F.G.F., G.M., A.M., G.N., G.R., F.A., G.V., M.R.B., and F.F. managed patients in each center, contributed the data, and revised and approved the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

Non-author contributors belonging to the ITA.LI.CA group are listed as a footnote.

Appendix

Collaborators of the ITA.LI.CA group.

Francesca Avanzato, Maurizio Biselli, Paolo Caraceni, Francesca Garuti, Annagiulia Gramenzi, Andrea Neri, Valentina Santi − Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, Semeiotics Unit, University of Bologna.

Filippo Pellizzaro, Angela Imondi, Anna Sartori, Barbara Penzo, Ambra Sanmarco − Department of Surgery, Oncology and Gastroenterology, University of Padova.

Alessandro Granito, Luca Muratori, Fabio Piscaglia, Vito Sansone − Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria S. Orsola-Malpighi, Internal Medicine-Piscaglia Unit, Bologna.

Elton Dajti, Giovanni Marasco, Federico Ravaioli − Department of Surgical and Medical Sciences, Gastroenterology Unit, Alma Mater Studiorum-University of Bologna.

Alberta Cappelli, Rita Golfieri, Cristina Mosconi, Matteo Renzulli − Department of Specialist, Diagnostic and Experimental Medicine, Radiology Unit, University of Bologna.

Ester Marina Cela, Antonio Facciorusso − Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy Unit, Foggia University Hospital.

Valentina Cacciato, Edoardo Casagrande, Alessandro Moscatelli, Gaia Pellegatta − Department of Internal Medicine, Gastroenterology Unit, University of Genova, IRCCS Policlinico San Martino, Genova.

Nicoletta de Matthaeis Gastroenterology Unit, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, IRCCS, Roma.

Nicoletta de Matthaeis Gastroenterology Unit, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, IRCCS, Roma.Gloria Allegrini − Department of Gastroenterology, Polytechnic University of Marche, Ancona.

Valentina Lauria, Giorgia Ghittoni, Giorgio Pelecca − Gastroenterology Unit, Belcolle Hospital, Viterbo.

Fabrizio Chegai, Fabio Coratella, Mariano Ortenzi − Vascular and Interventional Radiology Unit, Belcolle hospital, Viterbo.

Gabriele Missale − Department of Medicine and Surgery, Infectious Diseases and Hepatology Unit, University of Parma and Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria of Parma.

Alessandro Inno, Fabiana Marchetti − Gastroenterology Unit, IRCCS Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Hospital, Negrar.

Anita Busacca, Giuseppe Cabibbo, Calogero Cammà, Vincenzo Di Martino, Giacomo Emanuele Maria Rizzo − Department of Health Promotion, Mother & Child Care, Internal Medicine & Medical Specialties, PROMISE, Gastroenterology & Hepatology Unit, University of Palermo.

Maria Stella Franzè, Carlo Saitta − Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Clinical and Molecular Hepatology Unit, University of Messina.

Assunta Sauchella − Department of Medical, Surgical and Experimental Sciences, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria of Sassari.

Vittoria Bevilacqua, Alberto Borghi, Andrea Casadei Gardini, Fabio Conti, Anna Chiara Dall'Aglio, Giorgio Ercolani, Federica Mirici − Department of Internal Medicine, Ospedale per gli Infermi di Faenza.

Chiara Di Bonaventura, Stefano Gitto, Valentina Adotti − Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, Internal Medicine and Hepatology Unit, University of Firenze.

Pietro Coccoli, Antonio Malerba − Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery, Hepato-Gastroenterology Unit, University of Napoli “Federico II”.

Filomena Morisco − Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery, Gastroenterology Unit, University of Napoli “Federico II”.

Filippo Oliveri, Veronica Romagnoli − Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Hepatology and Liver Physiopathology Laboratory, University Hospital of Pisa.

References

- 1.Akinyemiju T, Akinyemiju T, Abera S, Ahmed M, Alam N, Alemayohu MA, et al. The burden of primary liver cancer and underlying etiologies from 1990 to 2015 at the global, regional, and national level: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3((12)):1683–91. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumours. 8th ed 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;391((10127)):1301–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolondi L, Burroughs A, Dufour JF, Galle PR, Mazzaferro V, Piscaglia F, et al. Heterogeneity of patients with intermediate (BCLC B) hepatocellular carcinoma: proposal for a subclassification to facilitate treatment decisions. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32((4)):348–59. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1329906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JH, Shim JH, Lee HC, Sung KB, Ko HK, Ko GY, et al. New intermediate-stage subclassification for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization. Liver Int. 2017;37((12)):1861–8. doi: 10.1111/liv.13487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogasawara S, Chiba T, Ooka Y, Kanogawa N, Motoyama T, Suzuki E, et al. A prognostic score for patients with intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization. PLoS One. 2015;10((4)):e0125244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giannini EG, Moscatelli A, Pellegatta G, Vitale A, Farinati F, Ciccarese F, et al. Application of the intermediate-stage subclassification to patients with untreated hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111((1)):70–7. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serper M, Taddei TH, Mehta R, D'Addeo K, Dai F, Aytaman A, et al. Association of provider specialty and multidisciplinary care with hepatocellular carcinoma treatment and mortality. Gastroenterology. 2017;152((8)):1954–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitale A, Trevisani F, Farinati F, Cillo U. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in the precision medicine era: from treatment stage migration to therapeutic hierarchy. Hepatology. 2020;72((6)):2206–2218. doi: 10.1002/hep.31187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park JW, Chen M, Colombo M, Roberts LR, Schwartz M, Chen PJ, et al. Global patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma management from diagnosis to death: the BRIDGE Study. Liver Int. 2015;35((9)):2155–66. doi: 10.1111/liv.12818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giannini EG, Bucci L, Garuti F, Brunacci M, Lenzi B, Valente M, et al. Patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma need a personalized management: a lesson from clinical practice. Hepatology. 2018;67((5)):1784–96. doi: 10.1002/hep.29668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson PJ, Berhane S, Kagebayashi C, Satomura S, Teng M, Reeves HL, et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33((6)):550–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinato DJ, Sharma R, Allara E, Yen C, Arizumi T, Kubota K, et al. The ALBI grade provides objective hepatic reserve estimation across each BCLC stage of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;66((2)):338–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadalayil L, Benini R, Pallan L, O'Beirne J, Marelli L, Yu D, et al. A simple prognostic scoring system for patients receiving transarterial embolisation for hepatocellular cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24((10)):2565–70. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park Y, Kim SU, Kim BK, Park JY, Kim DY, Ahn SH, et al. Addition of tumor multiplicity improves the prognostic performance of the hepatoma arterial-embolization prognostic score. Liver Int. 2016;36((1)):100–7. doi: 10.1111/liv.12878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cappelli A, Cucchetti A, Cabibbo G, Mosconi C, Maida M, Attardo S, et al. Refining prognosis after trans-arterial chemo-embolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2016;36((5)):729–36. doi: 10.1111/liv.13029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinato DJ, Arizumi T, Allara E, Jang JW, Smirne C, Kim YW, et al. Validation of the hepatoma arterial embolization prognostic score in European and Asian populations and proposed modification. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13((6)):1204–8.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sieghart W, Hucke F, Pinter M, Graziadei I, Vogel W, Müller C, et al. The ART of decision making: retreatment with transarterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2013;57((6)):2261–73. doi: 10.1002/hep.26256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hucke F, Pinter M, Graziadei I, Bota S, Vogel W, Müller C, et al. How to STATE suitability and START transarterial chemoembolization in patients with intermediate stage hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2014;61((6)):1287–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chon YE, Park H, Hyun HK, Ha Y, Kim MN, Kim BK, et al. Development of a new nomogram including neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio to predict survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization. Cancers. 2019;11((4)):509. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trevisani F, Golfieri R. Lipiodol transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: where are we now? Hepatology. 2016;64((1)):23–5. doi: 10.1002/hep.28554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carling U, Røsok B, Line PD, Dorenberg EJ. ALBI and P-ALBI grade in Child-Pugh A patients treated with drug eluting embolic chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Radiol. 2019;60((6)):702–9. doi: 10.1177/0284185118799519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Gordon FD, Peine CJ, Rank J, ter Borg PC. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology. 2000;31((4)):864–71. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60((8)):646–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farinati F, Vitale A, Spolverato G, Pawlik TM, Huo TL, Lee YH, et al. Development and validation of a new prognostic system for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS Med. 2016;13((4)):e1002006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.A new prognostic system for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 435 patients: the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) investigators. Hepatology. 1998;28:751–5. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu PH, Hsu CY, Hsia CY, Lee YH, Huang YH, Su CW, et al. Proposal and validation of a new model to estimate survival for hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Eur J Cancer. 2016;63:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang JD, Kim WR, Park KW, Chaiteerakij R, Kim B, Sanderson SO, et al. Model to estimate survival in ambulatory patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2012;56((2)):614–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.25680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kokudo N, Hasegawa K, Akahane M, Igaki H, Izumi N, Ichida T, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for hepatocellular carcinoma: the Japan Society of Hepatology 2013 update (3rd JSH-HCC Guidelines) Hepatol Res. 2015;45((2)):123–7. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yau T, Tang VY, Yao TJ, Fan ST, Lo CM, Poon RT. Development of Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging system with treatment stratification for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2014;146((7)):1691–700.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30((1)):52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baraldi AN, Enders CK. An introduction to modern missing data analyses. J Sch Psychol. 2010;48((1)):5–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolondi L, Cillo U, Colombo M, Bolondi L, Cillo U, Colombo M, et al. Position paper of the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF): the multidisciplinary clinical approach to hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45((9)):712–23. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sieghart W, Hucke F, Peck-Radosavljevic M. Transarterial chemoembolization: modalities, indication, and patient selection. J Hepatol. 2015;62((5)):1187–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen ZH, Hong YF, Chen X, Chen J, Lin Q, Lin J, et al. Comparison of five staging systems in predicting the survival rate of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing trans-arterial chemoembolization therapy. Oncol Lett. 2018;15((1)):855–62. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park Y, Kim BK, Park JY, Kim DY, Ahn SH, Han K-H, et al. Feasibility of dynamic risk assessment for patients with repeated trans-arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2019;19((1)):363. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5495-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data