Abstract

Objectives

Our study sought to determine the effects of valerian on sleep quality, depression, and state anxiety in hemodialysis (HD) patients.

Methods

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover clinical trial was conducted on 39 patients undergoing HD allocated into a valerian and placebo group. In the first phase of the study, group A (n = 19) received valerian and group B (n = 20) received a placebo one hour before sleep every night for a total of one month. Sleep quality, state anxiety, and depression were assessed in the patients at the beginning and end of the intervention using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, and Beck Depression Inventory. In the second phase, the two groups’ treatment regimen was swapped. After a one-month washout period, the same process was repeated on the crossover groups (i.e., group A received placebo and group B received valerian).

Results

In the first phase, the mean sleep quality, depression, and state anxiety scores showed significant reductions in both groups, but the reduction was significantly higher in group A compared to group B (7.6 vs. 3.2, p< 0.001; 6.5 vs. 2.3, p =0.013; 14.6 vs. 7.3, p =0.003, respectively). In the second phase, the mean sleep disorder, depression, and state anxiety scores showed significant reductions in both groups, but the reduction was significantly lower in group A compared to group B (1.4 vs. 4.6, p< 0.001; 1.2 vs. 3.8, p =0.002; 1.5 vs. 6.2, p< 0.001, respectively).

Conclusions

Valerian significantly improved sleep quality, the symptoms of state anxiety, and depression in HD patients.

Keywords: Depression, Renal Dialysis, Sleep, Anxiety, Valerian

Introduction

Sleep is one of the most vital physical, mental, and emotional needs of human beings, and many hemodialysis (HD) patients suffer from poor sleep quality.1 Sleep disorders may be an important risk factor for the incidence of mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety.2 Depression and sleep disorders are more prevalent in HD patients.3 The etiology of sleep and mental health disorders in patients on dialysis to be multi-factorial, including dialysis, metabolic abnormalities, muscle cramps, medications, fatigue, peripheral neuropathy, emotional problems, malnutrition,3,4 and body mass index (BMI).5 They, therefore, have a poor quality of life and two-times increased risk of mortality.6

In addition to sleep disorders, anxiety and depression are associated with a low quality of life in HD patients.7 The prevalence of sleep disorders, anxiety, and depression has been reported as 66.7%,8 67.5%,9 and 62%10 in HD patients in Iran. These complications can threaten patients’ health and quality of life but sometimes could be neglected in clinical practice.3

Sedatives and hypnotic drugs are frequently used to treat sleep disorders. These drugs’ most common side effects include impairment of the natural sleep cycle, reduced nervous system function, remaining sedative effect throughout the day, insomnia, respiratory problems, and immunity risks. The regular use of sleeping pills causes tolerance to the medications and creates sleep deprivation symptoms and insomnia after the drug is discontinued.11 The use of complementary medicine is growing in an attempt to improve sleep quality in these patients.12

Valerian is one of the medicinal plants used to reduce anxiety and sleep disorders.13 Valerian contains 150 to 200 different substances including volatile oils, ketones, phenols, iridoid esters such as valepotriates, alkaloids, valeric acid, amino acids like aminobutyric acid, arginine, tyrosine, glutamine, and noncyclic, monocyclic, and bicyclic hydrocarbons.14 Valerian/cascade mixture significantly decreased the latency time for sleeping and increased total sleeping time. The mixture significantly increased the non-rapid eye movement sleep time, while rapid eye movement sleeping time was decreased. Electroencephalography investigation indicated decreased awakening and increased total sleep time.15 It has also been administered as a sedative-hypnotic herb for many years. Valepotriates and valerenic acid found in valerian root are responsible for the plant’s sedative and anxiolytic effects.16 Assisting sleep effect of valerian/cascade mixture was shown to be due to the upregulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid A (GABA) receptor.15 The valerenic acid contained in valerian inhibits the enzyme system responsible for the catabolism of GABA.17 Valerian and its constituents (e.g., valerenic acid) serve as GABA agonists, and the effect of the plant on GABAA receptors is similar to the effect of benzodiazepines.18 The mechanism of action of valerian has been explained by several theories. The constituents of valerian may increase GABA concentrations and decrease central nervous system activity by inhibiting the enzyme system responsible for the central catabolism of GABA.19 Valerian may also stimulate the release and reuptake of GABA and bind directly to GABAA receptors.20 According to the available evidence, valerian may be the most promising agent for assisting sleep21 that is also considered a partial agonist of the 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor that boosts melatonin release.22 Antidepressant and mood-stabilizing effects have also been proposed for valerian,23 which could be due to the plant’s ability to interfere with noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmitters, especially serotonin and GABA.17 Over the past few decades, the root extract of valerian has been widely used as a flowering plant to treat sleeping disorders in Europe.24 Ziegler et al,25 compared the effects of a six-week treatment with valerian extract (600 mg/day) and oxazepam (10 mg/day) in 202 patients. They found that both groups enjoyed an enhanced sleep quality, while valerian was at least equally effective as oxazepam. The effects of valerian and oxazepam were perceived to be very good by 83% and 73% of the patients, respectively.

The US Food and Drug Administration lists valerian as a food supplement with no contraindications for its use.26 Valerian is a perennial herb native to North America, Asia, and Europe whose root is believed to possess sedative and hypnotic properties.27

Today, valerian root extract is an accepted over-the-counter medicine for treating stress and nervous tension, disturbed sleep patterns, and anxiety in Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, Italy, and France.28 Valerian can also affect sleep quality in patients with multiple sclerosis.29 Studies have indicated that valerian is effective in treating anxiety and depression in menopausal women.30 Valerian is a safe herbal remedy in HD.31 Valerian has also shown efficacy with few or no adverse effects when used correctly and following expert recommendations.28 But the evidence for natural remedies is controversial and weak and is not recommended for acute or chronic sleep disorders.2 Therefore, there is a tendency to use alternative and complementary therapies to assist sleep disorders.32 Further research that valerian assists sleep is required,33 and its use as an anti-anxiety and anti-depression agent also requires further investigations.34

It is thought valerian might be a safe herbal medicine for use in HD, considering the high prevalence of sleep disorders, depression, and state anxiety and their related complications in HD patients. To date, there are contradictory results on the effectiveness of valerian on these issues in this group. Previous studies have examined the effect of valerian on sleep disorders or depression and state anxiety in non-HD patients.29,30 In the present study, the effect of valerian on sleep quality, depression, and state anxiety was explored in HD patients.

METHODS

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover clinical trial was conducted on patients undergoing HD in Mehdishahr and Kowsar hospitals in Semnan, Iran. The randomization began by flipping a coin, where heads indicated allocation to group A and tails indicated allocation to group B. The next patient, who was similar to the first patient in terms of gender and age (difference of ±5 years), was assigned to the opposite group. Owing to the crossover design, both groups received both the valerian and placebo capsules. Also, the grouping of patients was performed by a nurse was blinded to other aspects of the study.

At the beginning of the study, we estimated a sample size of 15 data for each group. Since no changes were made to the study, the data of these 30 individuals were used in the final analysis. It is emphasized that no changes were made in any of the study components. For both valerian and placebo groups, respectively, the mean±standard deviation (SD) of changes were as follows: sleep quality score before and after intervention: 7.6±3.1 and 3.2±1.7, state anxiety scores: 14.6±7.3 and 7.3±5.1, and the depression score: 6.5±5.8 and 2.3±3.3.

The following equation was used to calculate the sample size. The sample size for each group in terms of sleep quality, state anxiety, and depression was estimated to be 6, 12, and 20, respectively, considering a 95% confidence interval and 80% power.

| n = [(S12 + S22) × (Z1-α/2 + Z1-β)2]/ (X1 − X2)2 |

Data were collected using a demographic questionnaire, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) to assess the neuropsychiatric status. Cigarette smoking, drinking tea per day, and respiratory disorders, which may affect sleep were entered in the demographic questionnaire.

The PSQI is a self-report questionnaire that evaluates the quality of sleep over one month.35 It consists of seven components including subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disorders, sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. The total score of the PSQI ranges from zero to 21, and scores greater than five indicate poor sleep quality.36 The validity of the Persian version of the questionnaire was confirmed with a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 93%, and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89.12

The BDI is a 21-item tool and uses 0–3 Likert scales for determining the severity of depression. The total scores in this scale range from zero to 63, and higher scores indicate higher severity of depression (scores showed mild (11–16), moderate (17–29), and severe (30–63)). It has been used in both the general and chronic kidney disease population.37 BDI intra-class correlation coefficient was 0.85, and by using Spearman-Brown formula, the validity of the scale was 0.81.38

The STAI is an instrument with two 20-item subscales for the measurement of state and trait anxiety. All the items in this inventory were scored based on a four-point Likert scale. The items in the state anxiety subscale assess the intensity of feelings ‘in the moment’. In this study, the STAI was used to measure state anxiety.39 The scores of state anxiety range from 20 to 80 classified as mild (20–39), moderate (40–59), and severe (60–80).

The inclusion criteria consisted of age > 18 years, undergoing HD three times a week for three hours or more, history of HD for at least three months,12 full consciousness, hearing and speech ability, and lack of sensitivity to plants.

The exclusion criteria consisted of physical disability, mental disorder, drug addiction, cancer, hearing or visual impairment, recent experience of stressful events, history of kidney transplantation, liver disease, hepatitis, cirrhosis or acute illnesses, BMI > 30 kg/m2, traveling, or death.

The researchers visited different wards of the HD department of the select hospitals. They evaluated the patients undergoing HD in different shifts (morning, evening, and night) to select the eligible candidates. The patients were briefed on the research objectives and methods. They recruited a sample of HD patients who experienced poor sleep quality as per their self-reported symptoms and had no medical or psychiatric conditions leading to sleep disorders. The PSQI was completed to assess the patients’ sleep quality in the past month. The eligible patients with PSQI scores equal to or greater than five participated in the study and sign consent forms. The participants completed the PSQI at the beginning of their HD sessions, and the demographic questionnaire, STAI, and BDI were completed later. The use of valerian and placebo capsules was examined by a nephrologist informed of intervention type for each participant. As the study was double-blind, participants, researchers, and statisticians were blind to the study groups until the analysis was completed.

The valerian capsules (Sedamin, Goldaru Co., Iran) contained 530 mg dried root of Valeriana officinalis (IRC 1228022753). The participants were randomly allocated to two groups to receive either valerian or placebo capsules (groups A andB, respectively).

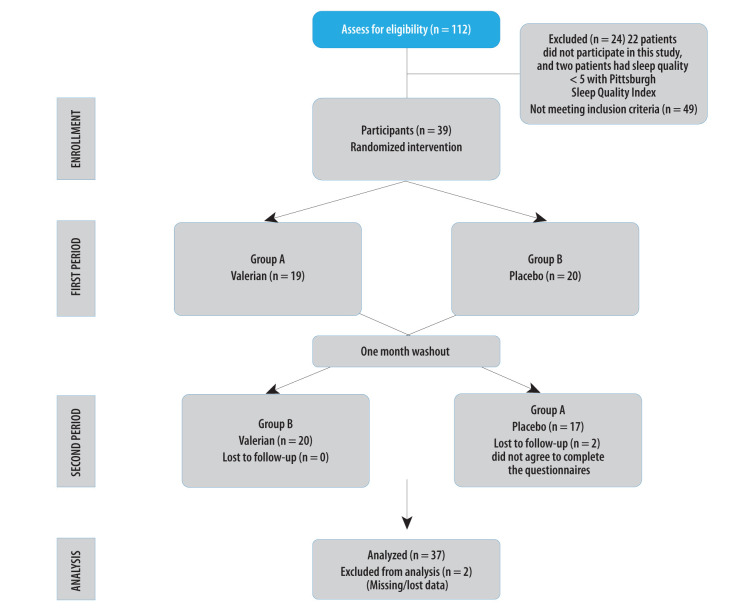

The placebo capsules contained 50 mg of starch and had a coating similar to the valerian capsules. Both groups were instructed to take the pills one hour before bedtime for one month. After a one-month washout period, each group’s medication regimen was swapped, and the procedure was repeated. Sleep quality, state anxiety, and depression were assessed using the questionnaires at the beginning and end of the two intervention phases [Figure 1]. The participants were asked to report any problems they faced that were linked to the drugs. The researchers followed up on the patients’ regular consumption of the capsules and possible side effects every week through a phone call and by visiting the HD ward.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study design, enrollment, randomization, follow-up, and analysis of study participants.

The ethical considerations of this research included obtaining the approval of the Ethics Committee of Semnan University of Medical Sciences IR.SEMUMSREC1394.145-2016-01-18, and registration of the trial at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials IRCT201601286318N5-2016-02-04. The Declaration of Helsinki assured patients that the data gathered has been kept confidential. Informed written consent was obtained. The participants were also ensured of their right to withdraw from the study at any time and that their participation would not affect their care process.

Data were first analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test for checking the normality assumption. If the normality assumption was met, the comparison of the two independent groups’ mean was carried out using a t-test; otherwise, Mann-Whitney U test was used. Further, the paired t-test was applied to compare the mean before and after concerning normality assumption, while Wilcoxon test was used for lack of normality in the data gathered. Also, in the case of nominal variables found in the qualitative findings, chi-square along with Cohen’s d for effect size were employed. All the analyses were performed in SPSS Statistics (SPSS Inc. Released 2009. PASW Statistics for Windows, Version 18.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc.), and p-values < 0.050 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The patients’ mean age was 66.4±14.0 years (range = 35–88 years) in group A and 65.6±12.4 years (range = 41–86) in group B. The two groups had no significant differences in their mean age (p = 0.857) using the Student’s t-test. A total of 52.6% of group A and 45.0% of group B were female (p = 0.634), using the chi-square test for nominal variables such as gender. The mean BMI was 23.6±3.3 kg/m2 in group A and 23.0±3.1 kg/m2 in group B (p = 0.549). None of the patients were obese in any of the two groups (BMI ≥ 30). The distribution of BMI was normal in both groups, which made the t-test useful. All the patients in both groups were married, and 31.6% in group A and 35.0% in group B were illiterate. The two groups had no significant differences in terms of education level distribution (p = 0.588). The income level was low in 21.1% of group A and 30.0% of group B (p = 0.513). Other variables such as the level of education and income were ranked using the Mann-Whitney test. Diabetes was the most common cause of dialysis in both groups (p = 0.618). The two groups were not significantly different in terms of the number of cups of tea drunk by the patients (p = 0.857). Due to the lack of a normal distribution in the two groups, the Mann-Whitney test was used [Table 1]. None of the patients in group A was a smoker, and only one patient (5.0%) smoked in group B (p = 1.000). The duration of HD in each dialysis session was four hours in all patients in both groups.

Table 1. Distribution of gender, body mass index (BMI), education level, income, dialysis causes, number of cups of tea consumed daily, and smoking in both groups.

| Indexes | Group | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A* | B | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | 0.634a | ||||

| Female | 10 | 52.6 | 9 | 45.0 | |

| Male | 9 | 47.4 | 11 | 55.0 | |

| BMI | 0.549b | ||||

| < 18.5 | 1 | 5.3 | 3 | 15.0 | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 12 | 63.2 | 12 | 60.0 | |

| 25–29.9 | 6 | 31.6 | 5 | 25.0 | |

| Education level | 0.588c | ||||

| Illiterate | 6 | 31.6 | 7 | 35.0 | |

| Elementary | 9 | 47.4 | 6 | 30.0 | |

| Diploma or higher | 4 | 21.1 | 7 | 35.0 | |

| Income | 0.513c | ||||

| Low | 4 | 21.1 | 6 | 30.0 | |

| Average | 14 | 73.7 | 14 | 70.0 | |

| Good | 1 | 5.3 | - | - | |

| Dialysis causes | 0.618a | ||||

| DM | 7 | 36.8 | 5 | 25.0 | |

| HTN | 4 | 21.1 | 4 | 20.0 | |

| DM, HTN | 4 | 21.1 | 8 | 40.0 | |

| Other | 4 | 21.1 | 3 | 15.0 | |

| Number of cups of tea | 0.857c | ||||

| 0 | - | - | 2 | 10.0 | |

| 1 | 5 | 26.3 | 5 | 25.0 | |

| 2 | 13 | 68.4 | 10 | 50.0 | |

| ≥ 3 | 1 | 5.3 | 3 | 15.0 | |

| Smoking | 1.000d | ||||

| No | 19 | 100 | 19 | 95.0 | |

| Yes | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.0 | |

DM: diabetes mellitus; HTN: hypertension.

*Group A took valerian capsules in the first month and placebo in the second month, and vice versa in group B.

a: Chi-square; b: student’s t-test; c: Mann-Whitney; d: McNemar test.

None of the patients in group A had a history of lung disease, while two patients (10.0%) in group B reported a history of lung disease (p = 0.487). There was no history of gastrointestinal diseases in any of the groups (p = 0.925). Ten (52.6%) patients in group A and seven (35.0%) in group B took hypnotic drugs (p = 0.267). None of the patients used anti-anxiety drugs and antidepressants. There was no significant difference between 52.6% of group A patients and 35.0% of group B patients using hypnotics. It should be noted that there were no alterations in patients’ medications during the study, and no side effects during and after the interventions were reported. There was no significant difference in patients’ dialysis adequacy scores in groups A and B in the first month of treatment, before(p = 0.411) and after the intervention (p = 0.659). Also, in the second month of treatment, the adequacy of dialysis was not significantly different between the two groups, before the intervention (p = 0.565) and also after the intervention (p = 0.605) [Table 2]. Table 3 shows the severity of depression and anxiety in patients. In this table, the frequency distribution of depression severity is reported based on the lowest level of depression (scores 11–16).

Table 2. Mean and standard deviation (SD) of dialysis adequacy score of patients before and after the intervention in both groups, first and second treatment periods.

| Group | First month | Second month | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Before intervention | After intervention | p-value | n | Before intervention | After intervention | p-value | |

| mean ± SD | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | |||||

| A* | 19 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 0.010 | 17 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.801 |

| B | 20 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 0.493 | 20 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 0.537 |

| p-value | - | 0.411 | 0.659 | - | - | 0.565 | 0.605 | - |

*Group A took valerian capsules in the first month and placebo in the second month, and vice versa in group B.

Table 3. Mild, moderate, and severe state anxiety and depression scores before and after the intervention in both groups, first and second treatment periods.

| Groups | First period | Second period | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | After intervention | Before intervention | After intervention | |||||||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| State anxiety | ||||||||||||

| A* | 2 (10.5) | 14 (73.7) |

3 (15.8) | 15 (78.9) |

4 (21.1) |

- | 10 (58.8) | 7 (41.2) |

- | 11 (64.7) | 6 (35.3) |

- |

| B | 1 (5.0) | 18 (90.0) |

1 (5.0) | 8 (40.0) |

12 (60.0) |

- | 6 (30.0) | 14 (70.0) |

- | 13 (65.0) | 7 (35.0) |

- |

| Depression | ||||||||||||

| A* | 4 (33.3) | 8 (66.7) |

- | 5 (100) |

- | - | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) |

- | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) |

- |

| B | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) |

- | 8 (72.7) |

3 (27.3) |

- | 12 (80.0) | 3 (20.0) |

- | 5 (100) |

- | - |

*Group A took valerian capsules in the first month and placebo in the second month, and vice versa in group B.

Data were given as n (%).

In the first treatment phase, the mean score of sleep quality decreased significantly in both groups (p < 0.001), but the reduction was significantly higher in group A compared to group B (7.6 vs. 3.2; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 1.93). Likewise, the mean scores of depression decreased significantly in both groups (p < 0.001), but the reduction was significantly higher in group A compared to group B (6.6 vs. 2.4; p = 0.013; Cohen’s d = 0.86). Similar significant reductions were observed in the mean scores of state anxiety in both groups (p < 0.001), but the reduction was significantly higher in group A (14.7 vs. 7.3; p = 0.003; Cohen’s d = 1.17).

In the second treatment phase, the analysis was performed on 37 participants (minus two patients in group A). The mean scores of sleep quality decreased significantly in groups A (p = 0.021) and B (p < 0.001), but the reduction was significantly lower in group A compared to group B (0.9 vs. 4.6; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 1.46). Again, the mean scores of depression decreased significantly in groups A (p = 0.006) and B (p < 0.001), but the reduction was significantly smaller in group A (1.3 vs. 3.8; p = 0.002; Cohen’s d = 1.13). The mean scores of state anxiety decreased significantly in groups A (p = 0.042) and B (p < 0.001), but the reduction was significantly lower in group A (1.6 vs. 6.2;p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 1.73). Tables 4 and 5 present the changes in the mean scores of sleep quality, depression, and state anxiety before and after the first and second treatment phases in groups A and B.

Table 4. The mean score of sleep quality, depression, and state anxiety before and after the intervention.

| Group | First month | Second month | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Before intervention |

After intervention |

p-value | n | Before intervention |

After intervention |

p-value | |||||

| mean±SD | mean±SD | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | |||||||||

| Sleep quality | ||||||||||||

| A* | 19 | 14.1 ± 2.7 | 6.5 ± 2.3 | < 0.00c | 17 | 8.4 ± 2.7 | 7.5 ± 2.5 | 0.021 | ||||

| B | 20 | 14.5 ± 3.4 | 11.3 ± 3.2 | < 0.00d | 20 | 12.1 ± 3.4 | 7.5 ± 2.2 | < 0.001 | ||||

| p-value^ | 0.496b | < 0.00a | - | 0.496b | 0.970a | |||||||

| Depression | ||||||||||||

| A* | 19 | 14.9 ± 7.4 | 8.3 ± 3.6 | < 0.001c | 17 | 10.2 ± 7.4 | 8.9 ± 4.2 | 0.006 | ||||

| B | 20 | 13.5 ± 7.1 | 11.1 ± 4.9 | 0.005c | 20 | 12.4 ± 7.1 | 8.6 ± 3.3 | < 0.001 | ||||

| p-value^ | 0.539a | 0.055a | - | 0.539a | 0.787a | |||||||

| State anxiety | ||||||||||||

| A* | 19 | 51.1 ± 7.9 | 36.4 ± 5.2 | < 0.001c | 17 | 39.4 ± 7.9 | 37.8 ± 5.0 | 0.042 | ||||

| B | 20 | 48.7 ± 6.7 | 41.4 ± 6.2 | < 0.001c | 20 | 43.9 ± 6.7 | 37.7 ± 4.3 | < 0.001 | ||||

| p-value^ | 0.305a | 0.012a | - | - | 0.305a | 0.907a | - | |||||

SD: standard deviation.

*Group A took valerian capsules in the first month and placebo in the second month, and vice versa in group B. ^p-value between groups A and B.

a: Student’s t-test; b: Mann-Whitney test; c: Paired t-test; d: Wilcoxon test.

Table 5. Mean and standard deviation (SD) score of sleep quality, depression, and state anxiety before and after the intervention in both groups A and B in the first and second treatment periods.

| Group | First month | Second month | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | ||

| Changes in sleep quality scores | |||||

| A* | 19 | 7.6 ± 3.1 | 17 | 0.9 ± 2.1 | |

| B | 20 | 3.2 ± 1.7 | 20 | 4.6 ± 2.3 | |

| p -value | < 0.001a | - | < 0.001a | ||

| Changes in depression scores | |||||

| A* | 19 | 6.6 ± 6.0 | 17 | 1.3 ± 1.6 | |

| B | 20 | 2.4 ± 3.3 | 20 | 3.8 ± 2.6 | |

| p -value | 0.013a | - | 0.002a | ||

| Changes in state anxiety scores | |||||

| A* | 19 | 14.7 ± 7.3 | 17 | 1.6 ± 2.8 | |

| B | 20 | 7.3 ± 5.1 | 20 | 6.2 ± 2.5 | |

| p -value | 0.003b | - | < 0.00b | ||

*Group A took valerian capsules in the first month and placebo in the second month, and vice versa in group B.

DISCUSSION

We sought to determine the effects of valerian on sleep quality, depression, and state anxiety in HD patients. We found that valerian use improves sleep quality, state anxiety, and depression symptoms significantly in HD patients. A Spanish study concluded that valerian can be used as a supplement to encourage sleep.40 An Australian study reported that treatment with valerian accelerates sleep onset and improves sleep quality in children with mental disorders.41 In the US, one study examined the effects of valerian on sleep quality in cancer patients undergoing treatment and observed reductions in sleeping problems and daytime sleepiness following the use of this herbal medicine.42 In contrast, another study found that taking valerian cannot improve sleep status significantly.43 In Norway, Oxman et al,44 rejected any significant differences in sleep quality between the valerian and placebo groups. Since the design of these two studies differs, the results of the study are not generalizable. Likewise, another US study reported that valerian extract has no significant effects on assisting sleep disorders in people with arthritis.45 Sleeping problems in HD patients differed from other patients. Although the exact mechanism of valerian on sleep disorders is unknown, the plant is believed to have important interactions with the neurotransmitter GABA. Valerian is thought to inhibit the uptake and stimulate the release of GABA.46 Moreover, this plant has recently been identified as a partial agonist of adenosine and serotonin receptors.47,48 These findings may explain the main mechanisms through which valerian enhances sleep quality. Valerian is also accepted as a partial agonist of the 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor that boosts melatonin release,22 which may be another mechanism through which the plant improves sleep quality. Nonetheless, considering the conflicting evidence, further research is required to clarify valerian’s effects on sleep and determine its exact mechanisms of action.

The results of this study showed that valerian decreases state anxiety and depression symptoms significantly in HD patients. In 2003, Müller et al,49 demonstrated that depressive disorders comorbid with anxiety disorders could be more quickly improved with a combination of St. John’s wort and valerian extracts compared to when undergoing monotherapy with St. John’s wort. Nevertheless, the evidence regarding the effectiveness of valerian application in the treatment of anxiety disorders is currently inadequate. There is no sufficient evidence on the efficacy of valerian in the treatment of anxiety disorders and sleep problems.50

The limitation of our study is the small number of participants. Although low sleep quality was a significant and prevalent disorder in HD patients in the studied centers, few people were willing to take the drug and participate in the study. In general, drug adherence was low in the patients. The reason for some HD patients (n = 22) in this study was their reluctance to participate. At the end of the study, two people were reluctant to complete the questionnaires. The rate of drug adherence in patients undergoing HD was low. The problem of non-adherence to drug therapy in HD patients can be further addressed in other studies. Appropriate interventions and strategies can be implemented to help enhance the patients’ motivation for adherence to medications.51 Also, sleep was quantified by symptom checklist, which is inferior to sleep lab or sleep architecture. Similarly, other checklists (depressive symptoms and anxiety traits) often give spurious results.

CONCLUSION

Valerian use improved sleep quality, state anxiety, and depression significantly in HD patients. Therefore, our results could help plan novel non-chemical approaches for decreasing sleep disorders, depression, and state anxiety. Further research is recommended to remove the limitations of this study.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Funding for this project was provided by Semnan University of Medical Sciences (No: 961).

Acknowledgment

This paper was part of the master's thesis of Zaynab Hydarinia Naieni in intensive care nursing. Hereby, we would like to express our gratitude to the Research and Technology Deputy of Semnan University of Medical Sciences and relevant authorities for their financial and support of this study (Grant No, 961). Also, we would like to show our appreciation to all the participating patients.

References

- 1.Eslami AA, Rabiei L, Khayri F, Rashidi Nooshabadi MR, Masoudi R. Sleep quality and spiritual well-being in hemodialysis patients. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2014. Jul;16(7):e17155. 10.5812/ircmj.17155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rios P, Cardoso R, Morra D, Nincic V, Goodarzi Z, Farah B, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for insomnia: an overview of reviews. Syst Rev 2019. Nov;8(1):281. 10.1186/s13643-019-1163-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu W. Nervous system disorders in chronic kidney disease: neurocognitive dysfunction, depression, and sleep disorder. Chronic Kidney Disease: Springer; 2020:161-169. [cited date]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-981-32-9131-7_13.

- 4.Masoumi M, Naini AE, Aghaghazvini R, Amra B, Gholamrezaei A. Sleep quality in patients on maintenance hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Int J Prev Med 2013. Feb;4(2):165-172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pojatić Đ, Pezerović D, Mihaljević D. Factors associated with sleep disorders in patients on chronic hemodialysis treatment. Southeastern European Medical Journal 2020;4(1):74-86. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brekke FB, Waldum B, Amro A, Østhus TB, Dammen T, Gudmundsdottir H, et al. Self-perceived quality of sleep and mortality in Norwegian dialysis patients. Hemodial Int 2014. Jan;18(1):87-94. 10.1111/hdi.12066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasilopoulou C, Bourtsi E, Giaple S, Koutelekos I, Theofilou P, Polikandrioti M. The impact of anxiety and depression on the quality of life of hemodialysis patients. Glob J Health Sci 2015. May;8(1):45-55. 10.5539/gjhs.v8n1p45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hydarinia Naieni Z, Nobahar M, Ghorbani R. The relationship between sleep quality in patients’ undergoing hemodialysis at different therapeutic’ shifts. Koomesh. 2016;18(1):42-50. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davaridolatabadi E, Abdeyazdan G. The relation between perceived social support and anxiety in patients under hemodialysis. Electron Physician 2016. Mar;8(3):2144-2149. 10.19082/2144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ravaghi H, Behzadifar M, Behzadifar M, Taheri Mirghaed M, Aryankhesal A, Salemi M, et al. Prevalence of depression in hemodialysis patients in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Kidney Dis 2017. Mar;11(2):90-98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dabirian A, Sadeghim M, Mojab F, Talebi A. The effect of lavender aromatherapy on sleep quality in hemodialysis patients. J Nurse Midwifery 2013;22(79):6-16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shariati A, Jahani S, Hooshmand M, Khalili N. The effect of acupressure on sleep quality in hemodialysis patients. Complement Ther Med 2012. Dec;20(6):417-423. 10.1016/j.ctim.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimazaki M, Martin JL. Do herbal agents have a place in the treatment of sleep problems in long-term care? J Am Med Dir Assoc 2007. May;8(4):248-252. 10.1016/j.jamda.2006.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao M, Ritchie HE, Brown-Woodman PD. A developmental toxicity-screening test of valerian. J Ethnopharmacol 2007. Sep;113(2):204-209. 10.1016/j.jep.2007.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi H-S, Hong K-B, Han SH, Suh HJ. Valerian/Cascade mixture promotes sleep by increasing non-rapid eye movement (NREM) in rodent model. Biomed Pharmacother 2018. Mar;99:913-920. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.01.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moline ML, Broch L, Zak R, Gross V. Sleep in women across the life cycle from adulthood through menopause. Sleep Med Rev 2003. Apr;7(2):155-177. 10.1053/smrv.2001.0228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felgentreff F, Becker A, Meier B, Brattström A. Valerian extract characterized by high valerenic acid and low acetoxy valerenic acid contents demonstrates anxiolytic activity. Phytomedicine 2012. Oct;19(13):1216-1222. 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trauner G, Khom S, Baburin I, Benedek B, Hering S, Kopp B. Modulation of GABAA receptors by valerian extracts is related to the content of valerenic acid. Planta Med 2008. Jan;74(1):19-24. 10.1055/s-2007-993761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plushner SL. Valerian: Valeriana officinalis. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2000. Feb;57(4):328-335, 333, 335. 10.1093/ajhp/57.4.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lefebvre T, Foster BC, Drouin CE, Krantis A, Livesey JF, Jordan SA. In vitro activity of commercial valerian root extracts against human cytochrome P450 3A4. J Pharm Pharm Sci 2004. Aug;7(2):265-273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baek JH, Nierenberg AA, Kinrys G. Clinical applications of herbal medicines for anxiety and insomnia; targeting patients with bipolar disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2014. Aug;48(8):705-715. 10.1177/0004867414539198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schroeck JL, Ford J, Conway EL, Kurtzhalts KE, Gee ME, Vollmer KA, et al. Review of safety and efficacy of sleep medicines in older adults. Clin Ther 2016. Nov;38(11):2340-2372. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jariani M, Saki M, Saki K, Ahmadi H, Tarahi M, Moumeni F. Effectiveness of Valerian as a complementary medicine on bipolar mood disorders. Journal of Ilam university of medical sciences 2009;17(1):19-24.

- 24.Houghton PJ. The scientific basis for the reputed activity of Valerian. J Pharm Pharmacol 1999. May;51(5):505-512. 10.1211/0022357991772772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ziegler G, Ploch M, Miettinen-Baumann A, Collet W. Efficacy and tolerability of valerian extract LI 156 compared with oxazepam in the treatment of non-organic insomnia–a randomized, double-blind, comparative clinical study. Eur J Med Res 2002. Nov;7(11):480-486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blumenthal M. Blumenthal M. The complete German commission E monographs-therapeutic guide to herbal medicines. Boston, MA: Integrative Medicine Communications; Austin, TX: American Botanical Council; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris CA, Avorn J. Internet marketing of herbal products. JAMA 2003. Sep;290(11):1505-1509. 10.1001/jama.290.11.1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross SM. Psychophytomedicine: an overview of clinical efficacy and phytopharmacology for treatment of depression, anxiety and insomnia. Holist Nurs Pract 2014. Jul-Aug;28(4):275-280. 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dalvanai A, Shojaeei A. Effect of Valerian on sleep quality in patients with multiple sclerosis. Iranian Journal of Rehabilitation Research 2018;4(3):18-24. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kazemian A, Parvin N, Raeisi Dehkordi Z, Rafieian-Kopaei M. The effect of valerian on the anxiety and depression symptoms of the menopause in women referred to shahrekord medical centers. Faslnamah-i Giyahan-i Daruyi 2017;16:96-101. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samaei A, Nobahar M, Hydarinia-Naieni Z, Ebrahimian AA, Tammadon MR, Ghorbani R, et al. Effect of valerian on cognitive disorders and electroencephalography in hemodialysis patients: a randomized, cross over, double-blind clinical trial. BMC Nephrol 2018. Dec;19(1):379. 10.1186/s12882-018-1134-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haghjoo E, Shojaii A, Parvizi M. Efficacy of topical herbal remedies for insomnia in Iranian traditional medicine. Pharmacognosy Res 2019;11(2):188-191 . 10.4103/pr.pr_163_18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooke M, Ritmala-Castrén M, Dwan T, Mitchell M. Effectiveness of complementary and alternative medicine interventions for sleep quality in adult intensive care patients: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2020. Jul;107:103582. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyasaka LS, Atallah AN, Soares BG. Valerian for anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006. Oct;(4):CD004515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roustaei N, Jamali H, Jamali MR, Nourshargh P, Jamali J. The association between quality of sleep and health-related quality of life in military and non-military women in Tehran, Iran. Oman Med J 2017. Mar;32(2):134-130. 10.5001/omj.2017.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Broocks A, Riemann D, Hohagen F. Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in primary insomnia. J Psychosom Res 2002. Sep;53(3):737-740. 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00330-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brekke FB, Waldum-Grevbo B, von der Lippe N, Os I. The effect of renal transplantation on quality of sleep in former dialysis patients. Transpl Int 2017. Jan;30(1):49-56. 10.1111/tri.12866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teles F, Azevedo VF, Miranda CT, Miranda MP, Teixeira MdoC, Elias RM. Depression in hemodialysis patients: the role of dialysis shift. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2014. Mar;69(3):198-202. 10.6061/clinics/2014(03)10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holm L, Fitzmaurice L. Emergency department waiting room stress: can music or aromatherapy improve anxiety scores? Pediatr Emerg Care 2008. Dec;24(12):836-838. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31818ea04c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dominguez RA, Bravo-Valverde RL, Kaplowitz BR, Cott JM. Valerian as a hypnotic for Hispanic patients. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2000. Feb;6(1):84-92. 10.1037/1099-9809.6.1.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Francis AJ, Dempster RJ. Effect of valerian, Valeriana edulis, on sleep difficulties in children with intellectual deficits: randomised trial. Phytomedicine 2002. May;9(4):273-279. 10.1078/0944-7113-00110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barton DL, Atherton PJ, Bauer BA, Moore DF, Jr, Mattar BI, Lavasseur BI, et al. The use of Valeriana officinalis (Valerian) in improving sleep in patients who are undergoing treatment for cancer: a phase III randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study (NCCTG Trial, N01C5). J Support Oncol 2011. Jan-Feb;9(1):24-31. 10.1016/j.suponc.2010.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobs BP, Bent S, Tice JA, Blackwell T, Cummings SR. An internet-based randomized, placebo-controlled trial of kava and valerian for anxiety and insomnia. Medicine (Baltimore) 2005. Jul;84(4):197-207. 10.1097/01.md.0000172299.72364.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oxman AD, Flottorp S, Håvelsrud K, Fretheim A, Odgaard-Jensen J, Austvoll-Dahlgren A, et al. A televised, web-based randomised trial of an herbal remedy (valerian) for insomnia. PLoS One 2007. Oct;2(10):e1040. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taibi DM, Bourguignon C, Gill Taylor A. A feasibility study of valerian extract for sleep disturbance in person with arthritis. Biol Res Nurs 2009. Apr;10(4):409-417. 10.1177/1099800408324252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santos MS, Ferreira F, Cunha AP, Carvalho AP, Ribeiro CF, Macedo T. Synaptosomal GABA release as influenced by valerian root extract–involvement of the GABA carrier. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther 1994. Mar-Apr;327(2):220-231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Müller CE, Schumacher B, Brattström A, Abourashed EA, Koetter U. Interactions of valerian extracts and a fixed valerian-hop extract combination with adenosine receptors. Life Sci 2002. Sep;71(16):1939-1949. 10.1016/S0024-3205(02)01964-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dietz BM, Mahady GB, Pauli GF, Farnsworth NR. Valerian extract and valerenic acid are partial agonists of the 5-HT5a receptor in vitro. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2005. Aug;138(2):191-197. 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Müller D, Pfeil T, von den Driesch V. Treating depression comorbid with anxiety–results of an open, practice-oriented study with St John’s wort WS 5572 and valerian extract in high doses. Phytomedicine 2003;10(Suppl 4):25-30. 10.1078/1433-187X-00305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nunes A, Sousa M. [Use of valerian in anxiety and sleep disorders: what is the best evidence?]. Acta Med Port 2011. Dec;24(Suppl 4):961-966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nobahar M. Exploration the experiences of hemodialysis patients about drug consumption: A content analysis. Majallah-i Danishgah-i Ulum-i Pizishki-i Mazandaran 2017;26(145):345-363. [Google Scholar]