Abstract

Background

Subclinical Cushing’s disease (SCD) is defined by corticotroph adenoma-induced mild hypercortisolism without typical physical features of Cushing’s disease. Infection is an important complication associated with mortality in Cushing’s disease, while no reports on infection in SCD are available. To make clinicians aware of the risk of infection in SCD, we report a case of SCD with disseminated herpes zoster (DHZ) with the mortal outcome.

Case presentation

An 83-year-old Japanese woman was diagnosed with SCD, treated with cabergoline in the outpatient. She was hospitalized for acute pyelonephritis, and her fever gradually resolved with antibiotics. However, herpes zoster appeared on her chest, and the eruptions rapidly spread over the body. She suddenly went into cardiopulmonary arrest and died. Autopsy demonstrated adrenocorticotropic hormone-positive pituitary adenoma, renal abscess, and DHZ.

Conclusions

As immunosuppression caused by SCD may be one of the triggers of severe infection, the patients with SCD should be assessed not only for the metabolic but also for the immunodeficient status.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12902-021-00757-y.

Keywords: Subclinical Cushing’s disease, Disseminated herpes zoster, Infection

Background

Cushing’s syndrome (CS) is caused by chronic exposure to excess glucocorticoids. CS is divided between adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-dependent and ACTH-independent causes [1]. Among ACTH-dependent CS, Cushing’s disease (CD) caused by ACTH-producing pituitary adenoma is most common [1]. In addition to CD, subclinical Cushing’s disease (SCD) has been identified in recent years [2]. SCD is defined by ACTH-induced mild hypercortisolism without typical physical features of CD including moon face, central obesity, buffalo hump, purple striae, thin skin, easy bruising, and proximal myopathy [3]. Even when clinical signs of overt hypercortisolism are not present, mild hypercortisolism is associated with metabolic changes such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and obesity, resulting in increased risk of mortality [4, 5]. Infection is one of the major complications related to mortality in the patients with CD [6], while no detailed reports on the risk of infection in the patients with SCD are available. Therefore, the relationship between SCD and infection has remained unknown. We experienced a case in which SCD might be one of the triggers of severe infection. To make clinicians aware of the risk of infection in SCD, we report a case of SCD with disseminated herpes zoster (DHZ) ultimately with the mortal outcome.

Case presentation

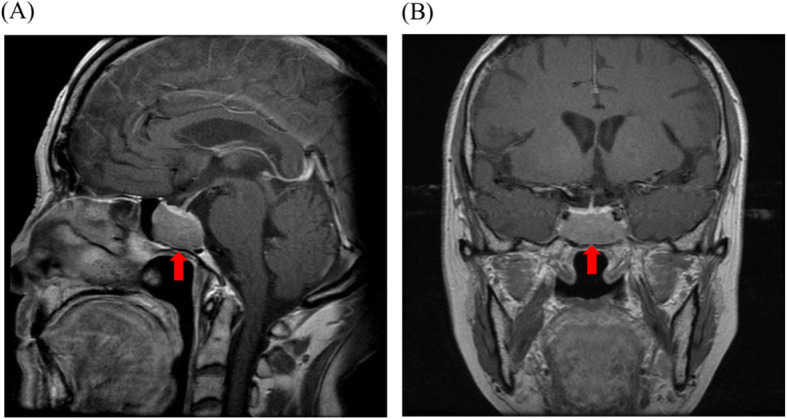

An 83-year-old Japanese woman was diagnosed with a 3-cm pituitary tumor by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in 2000 (Fig. 1). She was admitted to Hokkaido University Hospital because of general fatigue in 2014. She had no obvious Cushingoid appearance, but her plasma ACTH level and urinary free cortisol level were high. A low-dose (0.5 mg) overnight dexamethasone suppression test (DST) demonstrated incomplete suppression of plasma cortisol levels, and her plasma cortisol levels during night-time sleep remained high. Although her plasma cortisol levels remained high with a high-dose (8 mg) overnight DST, she was diagnosed with SCD because of the presence of a pituitary tumor in MRI (Table 1) [7]. Considering the risk of pituitary surgery at an advanced age and complications including diabetes mellitus, we initiated administration of 0.25 mg of cabergoline per week. The level of ACTH remained high after administration of cabergoline, and we gradually increased the dose of cabergoline from 0.25 mg to 1.5 mg per week in the outpatient. The size of the pituitary tumor did not change every year. Regarding diabetes mellitus, the glycemic control worsened in correlation with the ACTH and cortisol level. She was treated with insulin glargine 12 unit/day, liraglutide 0.9 mg/day, and mitiglinide calcium 30 mg/day and HbA1c level was approximately 8.0 % in the outpatient clinic.

Fig. 1.

Intracranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). a Sagittal view of contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI. b Coronal view of contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI. red arrows: pituitary adenoma

Table 1.

The results of endocrinological examinations for the diagnosis of SCD in 2014

| Basal levels of ACTH and cortisol | |

|---|---|

| ACTH (pg/mL) | 128.1 |

| plasma cortisol (µg/dL) | 11.2 |

| urinary cortisol (µg/day) | 116.6 |

| Screening tests | |

| plasma cortisol levels with 0.5 mg overnight DST (µg/dL) | 5.5 |

| ACTH levels with 0.5 mg overnight DST (pg/mL) | 99.55 |

| plasma cortisol levels during night time sleep (µg/dL) | 13.0 |

| Differential diagnosis of Cushing’s disease from EAS | |

| CRH test | Not performed |

| (With consideration for the risk of pituitary apoplexy) | |

| plasma cortisol levels with 8 mg overnight DST (µg/dL) | 7.1 |

| ACTH levels with 8 mg overnight DST (pg/mL) | 70.19 |

ACTH adrenocorticotropic hormone, CRH corticotropin releasing hormone, DST dexamethasone suppression test, EAS ectopic adrenocorticotropic syndrome, SCD subclinical Cushing’s disease

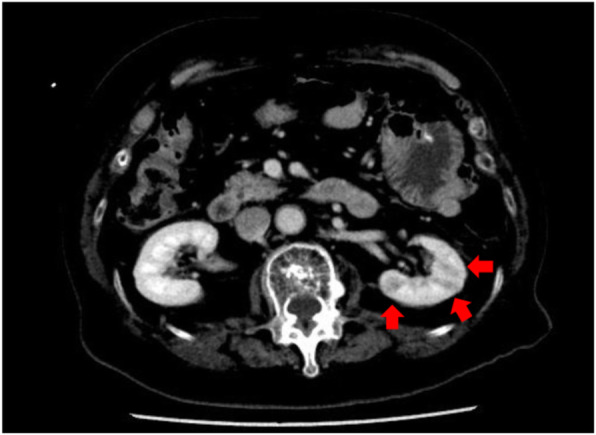

In May 2018, she was taken to our hospital because of decreased consciousness. Her body temperature was 37.7℃, pulse rate was 90 beats per minute, and blood pressure was 114/71 mmHg. She had a fever, but her physical examination was unremarkable. Laboratory tests showed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 35,900 /µL, C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 4.3 mg/dL, HbA1c level of 7.9 %, ACTH level of 300.7 pg/mL (normal range: 7.2–63.3 pg/mL) and cortisol level of 22.9 µg/dL (normal range: 4.0–23.3 µg/dL) (Table 2). Enhanced computed tomography showed a poor contrast of the left kidney (Fig. 2), and bacterial cultures from blood and urine were positive for Escherichia coli, demonstrating acute pyelonephritis. With antibiotics (meropenem 2 g/day), her fever gradually resolved and the CRP level decreased, while her glycemic control was poor despite intensive insulin therapy (casual blood glucose level was 200 to 300 mg/dL).

Table 2.

Laboratory findings on admission

| Complete blood cell count | |

|---|---|

| WBC (/µL) | 35,900 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 96 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 1.5 |

| RBC (/µL) | 4,290,000 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.5 |

| Plt (/µL) | 114,000 |

| Biochemistry | |

| TP/Alb (g/dL) | 4.9/2.5 |

| T-Bil (mg/dL) | 1.0 |

| AST/ALT/ALP (U/L) | 50/22/169 |

| BUN/Cr (mg/dL) | 21/0.66 |

| Na/K/Cl (mEq/L) | 143/2.2/97 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 4.3 |

| FPG (mg/dL) | 111 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.9 |

| Endocrine | |

| ACTH (pg/mL) | 300.7 |

| cortisol (µg/dL) | 22.5 |

WBC white blood cell, RBC red blood cell, Hb hemoglobin, Plt platelet, TP total protein, Alb albumin, T-Bil total bilirubin, AST aspartate amino transferase, ALT alanine amino transferase, ALP alkaline phosphatase, BUN blood urea nitrogen, Cr creatinine, CRP C-reactive protein, FPG fasting plasma glucose, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, ACTH adrenocorticotropic hormone

Fig. 2.

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) on admission. Poor contrast of the left kidney on enhanced CT demonstrating pyelonephritis. red arrows: poor contrast area

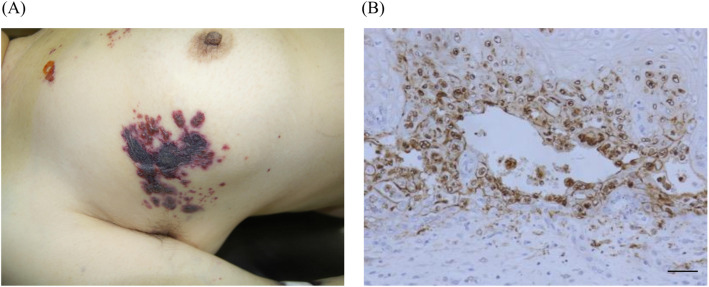

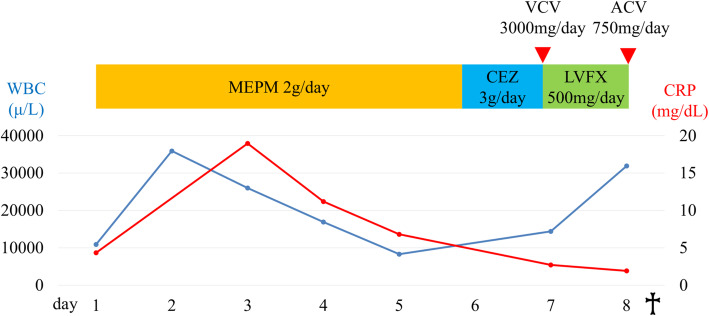

Unexpectedly, erythematous vesicles appeared on her chest on the seventh day (Fig. 3a). As skin eruptions rapidly spread over the entire body on the eighth day, we diagnosed the patient with herpes zoster, and started administering antiviral drugs (valacyclovir 3000 mg/day). She did not take steroids or any immunosuppressants. Laboratory tests showed an elevated WBC level, coagulation disorders, liver enzyme elevation and acute kidney injury, suggesting multiple organ insufficiency (Table 3). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody was negative. She suddenly went into cardiopulmonary arrest because of circulatory failure caused by septic shock and died despite all our efforts to save her life in the intensive care unit (Fig. 4). As a result of autopsy, the pituitary tumor was ACTH-positive, and other anterior pituitary hormones were negative on immunohistochemical staining. There were no malignant tumors suspected of ectopic ACTH-producing tumor. In addition, autopsy demonstrated renal abscess and varicella zoster virus (VZV) esophagitis (Fig. 3b), suggesting DHZ.

Fig. 3.

Physical and histological findings demonstrating varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection. a Erythematous vesicles appeared on the patient’s chest. b VZV immunostaining demonstrating disseminated herpes zoster esophagitis (×200), Scale bar: 50 µm

Table 3.

Laboratory findings when skin eruptions spread over the body (day 8)

| Complete blood cell count | |

|---|---|

| WBC (/µL) | 31,900 |

| seg. (%) | 50 |

| stab. (%) | 28 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 3.5 |

| RBC (/µL) | 4,770,000 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 14.0 |

| Plt (/µL) | 88,000 |

| Coagulation | |

| PT-INR | 4.65 |

| APTT (sec) | 70.1 |

| Fib (mg/dL) | <50 |

| D-dimer (μg/mL) | 750 |

| Biochemistry | |

| TP/Alb (g/dL) | 5.4/2.5 |

| T-Bil (mg/dL) | 2.1 |

| AST/ALT/ALP (U/L) | 2953/742/855 |

| BUN/Cr (mg/dL) | 27/1.2 |

| Na/K/Cl (mEq/L) | 133/3.4/91 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 1.9 |

WBC white blood cell, seg. segmented cell, stab. stab cell, RBC red blood cell, Hb hemoglobin, Plt platelet, PT-INR prothrombin time international normalized ration, APTT activated partial thromboplastin time, Fib fibrinogen, TP total protein, Alb albumin, T-Bil total bilirubin, AST aspartate amino transferase, ALT alanine amino transferase, ALP alkaline phosphatase, BUN blood urea nitrogen, Cr creatinine, CRP C-reactive protein

Fig. 4.

Clinical course after admission. blue line: WBC, white blood cell, led line: CRP, C-reactive protein. MEPM, meropenem; CEZ, cefazolin; LVFX, levofloxacin; VCV, valacyclovir; ACV, acyclovir

Discussion and conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report in which SCD might be one of the triggers of severe infection including DHZ. SCD could cause immunosuppression despite mild hypercortisolism, leading to renal abscess followed by sudden onset of DHZ. These severe infections induced septic shock and multiple organ failure, ultimately resulted in mortal outcome.

Infection is one of the major causes of death in patients with CD. A previous report has shown that 28/311 (9 %) of patients with CD that were followed up for a median period of 9 years died from cardiovascular causes in 14/28 (50 %), infection in 6/28 (21.4 %), and malignancy in 7/28 (25 %) [8]. Although no reports on the mortality of SCD are available, adrenal adenomas with mild hypercortisolism cause infection-related mortal outcomes [9]. We may need to pay attention to infection in patients with SCD as well as patients with CD.

DHZ infection often invades other organs, and occurs in patients with immunosuppression [10]. Immunosuppression caused by malignancy, HIV infection, and immunosuppressive therapy such as steroids increases the risk for herpes zoster infection [11]. Also, aging and diabetes mellitus were reported to increase the risk of herpes zoster infection [12]. In this case, hypercortisolism caused by SCD made it difficult to maintain normal blood glucose level. Although malignancy, HIV infection, and history of immunosuppressive therapy were not observed in this case, aging and secondary diabetes mellitus caused by SCD might be associated with the onset of DHZ.

On the other hand, infection in CD is a consequence of the immunosuppression induced by hypercortisolism [6]. In addition, disorders of circadian cortisol rhythm are associated with immunosuppression. Excess and dysrhythmic cortisol exposure can lead neutrophil dysfunction, decreased lymphocytes, and inactivation of lymphocytes, resulting in impaired immune function [9, 13]. In this case, the plasma cortisol level remained high at night-time, suggesting disappearance of the circadian rhythm of cortisol and lymphocytes. Furthermore, laboratory tests before admission showed that lymphocyte counts and IgG level were decreased (Supplementary Table 1), suggesting impaired immune function caused by SCD. As well as aging or diabetes, mild hypercortisolism and dysrhythmic cortisol exposure caused by SCD can be one of the triggers of severe infections including DHZ.

In conclusion, we reported a case in which SCD might be one of the triggers of severe infection including DHZ. As our case emphasized the risk of severe infections in the patients with SCD, the patients should be assessed not only for the metabolic but also for the immunodeficient status.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 1. Laboratory data before admission

Acknowledgements

We thank Michal Bell, PhD, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript. We thank Dr. Kenta Takahashi, Yoshiko Sato, and Harutaka Katano (National Institute for Infectious Disease in Japan) for immunostaining of VZV.

Abbreviations

- ACTH

Adrenocorticotropic hormone

- CD

Cushing’s disease

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CS

Cushing’s syndrome

- DHZ

Disseminated herpes zoster

- DST

Dexamethasone suppression test

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- SCD

Subclinical Cushing’s disease

- VZV

Varicella zoster virus

- WBC

White blood cell

Authors’ contributions

YY interpreted the patient data, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. MT and ST performed and analyzed the histological examination. HK is the guarantor of this work. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data from this article are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was waived from the ethics committee of Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine because of a case report.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the family for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lacroix A, Feelders RA, Stratakis CA, Nieman LK. Cushing’s syndrome. Lancet. 2015;386(9996):913–27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takao T, Mimoto T, Yamamoto M, Hashimoto K. Preclinical Cushing disease. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(6):892–3. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.6.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kageyama K, Moriyama T, Sakihara S, Kawashima S, Suda T. A case of preclinical Cushing’s disease, accompanied with thyroid papillary carcinoma and adrenal incidentaloma. Endocr J. 2003;50(3):325–31. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.50.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Dalmazi G, Vicennati V, Garelli S, Casadio E, Rinaldi E, Giampalma E, Mosconi C, Golfieri R, Paccapelo A, Pagotto U, Pasquali R. Cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with adrenal incidentalomas that are either non-secreting or associated with intermediate phenotype or subclinical Cushing’s syndrome: a 15-year retrospective study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(5):396–405. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70211-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ivović M, Marina LV, Šojat AS, Tančić-Gajić M, Arizanović Z, Kendereški A, Vujović S. Approach to the patient with subclinical Cushing’s syndrome. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(43):5584–90. doi: 10.2174/1381612826666200813134328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pivonello R, De Leo M, Cozzolino A, Colao A. The treatment of Cushing’s disease. Endocr Rev. 2015;36(4):385–486. doi: 10.1210/er.2013-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kageyama K, Oki Y, Sakihara S, Nigawara T, Terui K, Suda T. Evaluation of the diagnostic criteria for Cushing’s disease in Japan. Endocr J. 2013;60(2):127–35. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ12-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ntali G, Asimakopoulou A, Siamatras T, Komninos J, Vassiliadi D, Tzanela M, Tsagarakis S, Grossman AB, Wass JA, Karavitaki N. Mortality in Cushing’s syndrome: systematic analysis of a large series with prolonged follow-up. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;169(5):715–23. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Debono M, Bradburn M, Bull M, Harrison B, Ross RJ, Newell-Price J. Cortisol as a marker for increased mortality in patients with incidental adrenocortical adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(12):4462–70. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujisato S, Urushibara T, Kasai H, Ishi D, Inafuku K, Fujinuma Y, Shinozaki T. A fatal case of atypical disseminated herpes zoster in a patient with meningoencephalitis and seizures associated with steroid immunosuppression. Am J Case Rep. 2018;19:1162–7. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.910521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen JI. Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:255–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1302674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saadatian-Elahi M, Bauduceau B, Del-Signore C, Vanhems P. Diabetes as a risk factor for herpes zoster in adults: a synthetic literature review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;159:107983. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chrousos GP. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and immune-mediated inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(20):1351–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Laboratory data before admission

Data Availability Statement

All data from this article are available from the corresponding authors upon request.