Abstract

Previous studies indicate that the presence of peers influences children’s food consumption. It is assumed that one factor producing this effect in children is child modeling of food intake. The present study assesses the effect of a video model on the food intake of overweight (n=22) and nonoverweight (n=22) preadolescent girls. A 2 (weight status)×2 (small vs large serving size) factorial design was used to test the hypothesis that youth model others’ food intake. Serving sizes were manipulated by showing a video model selecting and consuming either a small or a large serving of cookies. Results indicate a main effect of serving size condition, F(1,40)=5.1, P<0.05 (d=0.65; 95% confidence interval: 0.35 to 0.65), and a main effect of weight status, F(1,40)=4.9, P<0.05 (d=0.63; 95% confidence interval: 0.35 to 0.65). Participants exposed to the large serving-size condition consumed more cookies than participants exposed to the small serving-size condition and overweight participants consumed considerably more cookies than nonoverweight participants. The interaction of weight status by serving-size condition did not reach statistical significance (P=0.2). These results suggest that peer-modeling influences overweight and nonoverweight preadolescent girls’ snack consumption.

Childhood overweight and obesity results from positive energy balance in which energy intake exceeds expenditure. One factor that may influence youth’s eating behavior is the social environment (1–5) and, more specifically, the social influence from their peers (6,7). Previous studies indicate that overweight youth eat twice as much in the presence of overweight peers than in the presence of leaner peers (8). It is often assumed that the effect of others on youth’s eating result from children modeling the behaviors of others (1). However, previous studies did not systematically manipulate the amount of food the peers ate. Thus, it is not clear whether youth were modeling the behavior of their peers or whether the mere presence of peers impacted youth’s food consumption.

Modeling studies in adults have consistently found a relationship between modeling and food consumption as participants eat much less in the presence of a model who eats minimally than in the presence of one who eats a large amount (9). One explanation for these findings is that, in the absence of rules or guidelines, the best source of information is the behavior of others (9). Conceivably, people use the amount of food eaten by others as an indication of what is appropriate to eat in a given situation.

The present study assesses the hypothesis that modeling influences eating in overweight and nonoverweight preadolescent girls. Serving sizes were manipulated by showing a video in which a model selected and consumed either a small or a large serving of cookies. Based on modeling studies in adults, we predicted that the amount of food eaten by the model would influence how much participants eat. More specifically, participants exposed to the small serving-size condition were expected to eat less than participants exposed to the large serving-size condition.

METHODS

Participants

Twenty-two nonoverweight (between the 15th and the 85th body mass index [BMI; calculated as kg/m2]-for-age percentile) and 22 overweight or at risk for becoming overweight (≥85th BMI percentile) females between 8 and 12 years of age participated in this study. A trained staff member assessed weight and height using a digital scale and a SECA (Seca 214, Seca North America East, Hanover, MD) stadiometer. Participants were recruited from newspaper ads and from a database of families who have volunteered for previous laboratory studies. Preliminary eligibility screening was completed by telephone prior to scheduling for study session and parents completed a questionnaire about demographics and socioeconomic level on the day of the experiment (10). Parents were instructed that the study required participants to abstain from eating 2 hours before the experimental session to standardize participants’ food intake prior to the study session. All ethnic groups were eligible to participate.

On the day of the appointment, a trained staff member assessed weight (in pounds) using a digital scale and height (in inches) using a digital stadiometer to determine eligibility and group assignment. To ensure accuracy, height measurements were repeated three times. The three measurements had no more than a difference of 0.03 cm; the median measurement was used and recorded. Children were excluded from the study if they had any of the following: <10th percentile BMI-for-age; had a cold or upper respiratory distress on the day of the study; current psychopathology or developmental disability; food allergies to the study food; reported having less than a moderate (4 or less on a 7-point Likert-type scale) liking for the cookies used in the study to participate; and/or taking medications or had conditions that could influence taste or appetite (eg, methylphenidate).

The Children and Youth Institutional Review Board of the University at Buffalo approved all procedures used in this study and all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during this research.

Study Design

The design of this study is a 2×2 between-group factorial design with serving size (large serving vs small serving) and weight status (overweight vs nonoverweight) as between factors. Overweight and nonoverweight participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. Both conditions involved the participants being exposed to a video showing a model selecting and consuming cookies. In one video, the model was shown selecting a large amount of mini bite-sized cookies; in the other video the model was shown selecting a smaller amount of mini bite-sized cookies.

Procedure

Upon arrival to the laboratory, all children heard an assent script and were asked if they were willing to take part in the study. Parents were asked to read and provide written consent. The participants completed a same-day food recall to ensure that they had abstained from eating 2 hours prior to the session time. Children were also asked to rate their liking of the cookies on a 7-point Likert-type scale anchored by “Do not like” and “Like very much.” This scale has been repeatedly used in our previous laboratory studies and it appropriately discriminates children who like the foods and are willing to eat them in the laboratory. Children also rated their hunger using 7-point Likert-type scales (anchored by “not hungry at all” and “really hungry”). Participants and their parents were then shown the experimental room. The room was equipped with a television monitor and a videocassette recorder, a table, and a chair. The experimenter described to the participants and their parents the experimental task, which involved sorting pictograms of different activities as described previously (10).

Under the rationale of making the task more pleasant, each participant was told to select a snack to eat while they worked on the task. The participant was casually shown an 8-oz preweighed bowl of mini bite-sized cookies (described later) and told that she could select as many cookies as she wanted. Once the participant understood the task and the instructions, the experimenter turned on the television monitor. The video model was seen entering the room. The experimenter left the room, allegedly to supervise another participant. At this point, the video model was shown selecting either a small or a large serving of cookies. The participant was further instructed through an intercom to select their snack and to sit at the table to start the sorting task. At this point, the video model was shown working on the sorting task and eating her cookies. After the 10-minute task, the experimenter returned to the room. Children and parents were debriefed and they received a $20 gift card for a shopping mall for their participation.

Video Model

The same 10-year-old girl modeled both serving sizes. The model was at the 75th percentile for BMI. She wore a light jacket over her clothes to conceal her bodyweight. In both videos, the model was shown selecting cookies in the same laboratory setting as the participants and she was shown working on the same sorting task that the participants completed. Both videotapes were standardized so that all participants were exposed to the video model for the same amount of time.

Food

Cookies used were Nabisco’s Mini Oreo Bite Size Cookies (Nabisco, East Hanover, NJ). Each cookie weighed approximately 2.9 g, yielding an average of 14.03 kcal (±0.3 g). In the small-portion condition, the model was shown selecting and eating 10 bite-sized cookies (29 g/1 oz), which is equivalent to 21⁄2 regular-sized Oreo cookies. In the large-portion condition, the model was selecting and consuming 77 bite-sized cookies (223 g/8 oz), which is equivalent to 20 regular-sized Oreo cookies. Uneaten snacks were weighed and discarded after each session. Each participant was provided with an 8-oz cup and a pitcher of fresh water.

Analytic Plan

A power analysis was conducted prior to the study to determine the sample size to achieve sufficient power. The analysis was based on a previous study on the effect of social influence on the intake of snack foods in lean (n=26) and overweight (n=24) preadolescent girls. This research showed that overweight youths eating with an overweight peer ate significantly more than overweight girls eating with a leaner peer (P<0.006), with an effect size for the main effect of group of 1.07. It was determined that with an α set at .05 and power of 0.80, a weight×condition interaction effect could be observed with 20 subjects per group.

Double data entry and quality check were performed prior to performing statistical analysis to ensure accuracy of the data. Statistical analyses were performed using SYSTAT software (version 11, 2004, Systat Software Inc, Richmond, CA). Preliminary analyses were performed on baseline variables (food intake prior to the session, hunger or liking of the study food) to determine whether there were differences between conditions.

This study tests the effect of a model on the energy consumption of overweight and normal-weight participants. The Levene’s test of equality of variance was performed to test the assumption of homogeneity of variance across conditions. A 2 (weight status)×2 (portion size) analysis of variance was used to assess differences in food consumption as a function of the conditions. The significance was set at P<0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characteristics of the study population are presented in the Table. Three participants were African American and five were Hispanic or Latino. The rest of the sample was white. There were no significant differences between groups in self-reported hunger or liking of the study food (all P values were >0.15).

Table.

Age and anthropometric characteristics of normal-weight and overweight participants exposed to a model eating a large serving of cookies

| Large Portion | Small Portion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Normal weight (n=11) |

Overweight (n=11) |

Normal weight (n=11) |

Overweight (n=11) |

| mean±standard deviation | ||||

| Age | 11.4±1.2 | 10.6±1.4 | 11.0±1.5 | 10.3±1.3 |

| Height (in) | 56.6±3.6 | 57.6±2.8 | 56.5±4.7 | 58.6±4.0 |

| Weight (lb) | 75.5±13.4* | 120.5±27.7* | 81.9±22.1* | 122.5±29.1* |

| BMIa | 16.4±1.4* | 25.2±3.6* | 17.6±2.3* | 24.7±3.2* |

| BMI-for-age percentilesb | 30.4±8.4* | 95.0±2.7* | 49.5±22.9* | 95.4±2.1* |

BMI=body mass index; calculated as kg/m2.

BMI-for-age percentiles; ≥85th percentile considered at risk or overweight; ≥15th and <85th percentile considered normal weight.

Significant difference between groups (P<0.001).

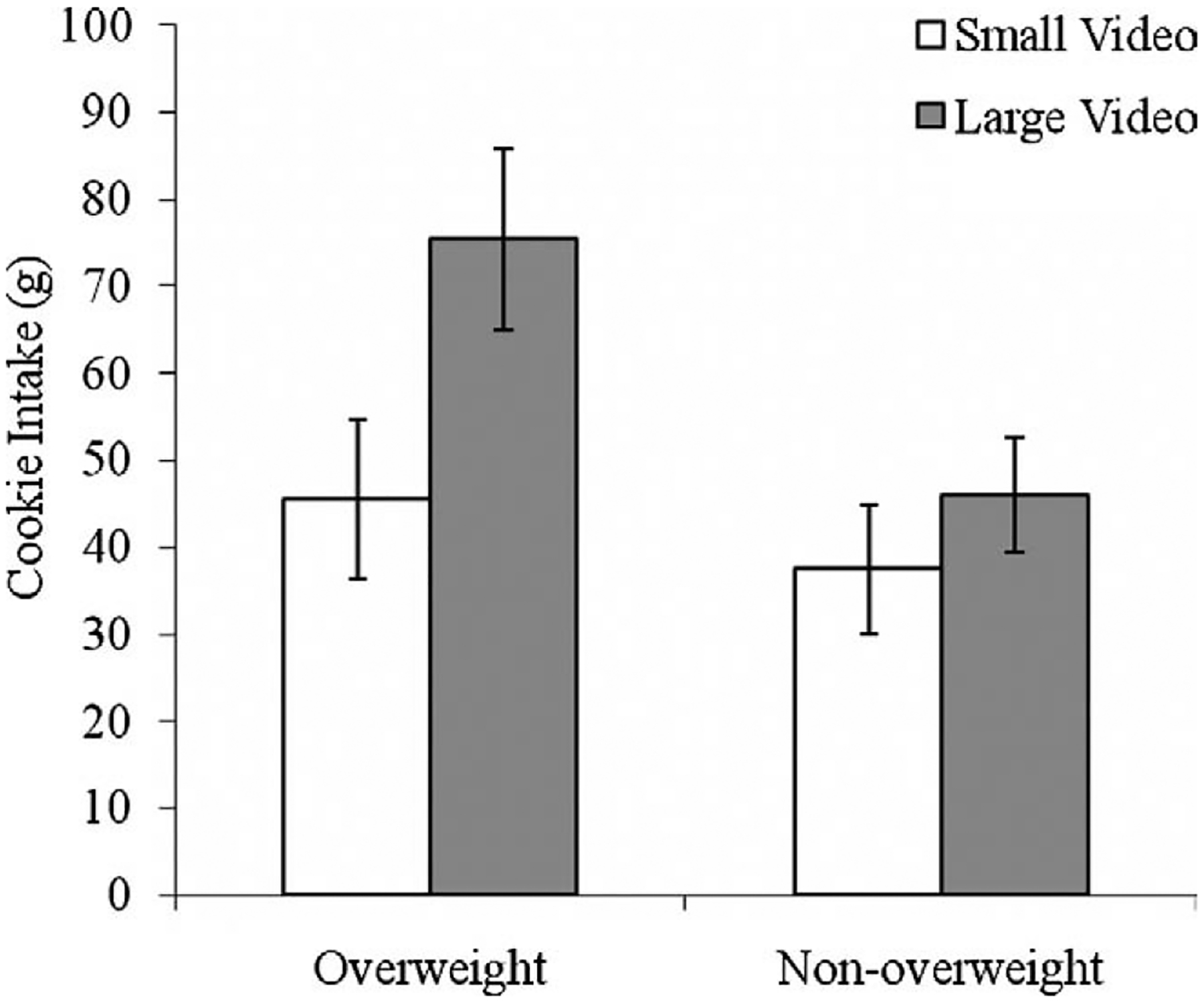

Results of the analysis of variance presented in the Figure indicate that overweight participants (mean [M]=60.5, standard deviation=35.1) consumed significantly more cookies than nonoverweight participants (M=41.7, standard deviation=23.2; F[1,40]=4.9; P<0.05; d=0.63; 95% confidence interval: 0.35 to 0.65). Furthermore, participants exposed to the small serving-size condition consumed fewer cookies (M=41.5, standard deviation=27.2) than participants exposed to the large serving size condition (M=60.7, SD=32.0; F[1,40]=5.1; P<0.05; d=0.65; 95% confidence interval: 0.35 to 0.65). The power analysis indicated that our sample was sufficient to detect the two main effects and the interaction of weight×condition. However, the interaction was not statistically significant.

Figure.

Mean and standard error of measurement of cookies (in grams) consumed as a function of weight status and video condition.

Previous research in adults has shown that individuals will conform or match how much they eat to the amount of food eaten by others around them (9). The present results indicate that similar processes operate in children. Use of a video allows a test of informational conformity rather than impression management (11) or normative conformity (12), which could occur if the peer model was in the presence of the participants. The participants apparently relied on the example set by the model in the video to determine how much they should eat. Participants exposed to the small conditions ate close to the amount modeled in the video. Participants exposed to the large serving-size condition ate a considerably larger amount of cookies than the participants exposed to the small serving-size condition. However, they did not eat the same amount of cookies as the video model. It is possible that participants saw the very large amount of cookies in this condition as an excessive and unrealistic amount of food to consume.

Earlier research suggests that overweight individuals might be more responsive than nonoverweight individuals to external factors that regulate their food intake (13,14). In the present study, the weight status of participants did not interact with the serving-size conditions, indicating that the video model had a similar effect on overweight and nonoverweight participants. There is evidence that modeling is influenced by the observer’s perceived similarity to the model (15,16). Similarity is hypothesized to serve as a source of information for gauging behavioral appropriateness (17). Although attempts were made to keep the model’s weight status ambiguous to minimize the effects of perceived weight status on modeling, the participants’ perceptions of the model were not assessed. It is possible that perceived similarity or the extent to which participants identified with the model impacted the amount of snack consumed.

There were limitations to this study. First, the small sample was one of convenience and these results need to be replicated with larger, more representative samples before generalizing these findings. Second, the present study did not involve a “no video” comparison group to assess the participants’ usual intake, which makes it difficult to determine whether the participants were eating more or less than what they would normally eat at home. This information would have been useful to assess participants’ knowledge of portion sizes prior to exposure to the video model. Third, although the time limitation of the sorting task (ie, 10 minutes) was useful for experimental control, it may have affected the amount eaten and limited the interpretation of the findings. Future studies might benefit from using a similar paradigm to look at longer eating periods and at meal rather than snack intake. Similarly, future studies are needed to assess whether the effects of social influence persist beyond the immediate effects observed in this study.

CONCLUSION

These findings support the effect of peer modeling on overweight and nonoverweight preadolescent girls’ snack consumption. However, explanatory mechanisms responsible for eating conformity in children were not directly tested in the present study. Future research would benefit from exploring social motives in children and examining how these factors impact their selection and regulation of food intake. As the serving sizes of prepackaged and restaurant foods increase, it becomes much more difficult for individuals to accurately estimate what constitutes appropriate portion sizes. Based on the present results, as well as on previous work (6–8,18), peer modeling can be seen as a suitable medium to teach children appropriate portion sizes and healthy behaviors. Applications include interventions designed to test whether peers and friends may be used to modify youths’ eating consumption and preferences as part as a more comprehensive weight-loss program.

References

- 1.Addessi E, Galloway AT, Visalberghi E, Birch LL. Specific social influences on the acceptance of novel foods in 2–5-year-old children. Appetite. 2005;45:264–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harper LV, Sanders KM. The effects of adults’ eating on young children’s acceptance of unfamiliar foods. J Exp Child Psychol. 1975;20: 206–214. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klesges RC, Coates TJ, Brown G, Sturgeon-Tillisch J, Moldenhauer-Klesges LM, Holzer B, Woolfrey J, Vollmer J. Parental influences on children’s eating behavior and relative weight. J App Behav Anal. 1983;16:371–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klesges RC, Stein RJ, Eck LH, Isbell TR, Klesges LM. Parental influence on food selection in young children and its relationships to childhood obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53:859–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendy HM, Raudenbush B. Effectiveness of teacher modeling to encourage food acceptance in preschool children. Appetite. 2000;34: 61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birch LL. Effects of peer models’ food choices and eating behaviors on preschoolers’ food preferences. Child Dev. 1980;51:489–496. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hendy HM. Effectiveness of trained peer models to encourage food acceptance in preschool children. Appetite. 2002;39:217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salvy SJ, Romero N, Paluch R, Epstein LH. Peer influence on preadolescent girls’ snack intake: Effects of weight status. Appetite. 2007; 49:177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herman CP, Roth DA, Polivy J. Effects of the presence of others on food intake: A normative interpretation. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:873–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vartanian LR, Herman CP, Polivy J. Consumption stereotypes and impression management: How you are what you eat. Appetite. 2007; 48:265–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deutsch M, Gerard H. A study of normative and informational influences upon individual judgment. J Abnorm Soc Psychol. 1955;51:629–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nisbett RE. Taste, deprivation, and weight determinants of eating behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1968;10:107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schachter S. Obesity and eating. Science. 1968;16:751–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gould D, Weiss M. The effects of model similarity and model task on self-efficacy and muscular endurance: A second look. J Sport Psychol. 1981;3:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss MR, Wiese DM, Klint KA. Head over heels with success: The relationship between self-efficacy and performance in competitive youth gymnastics. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1989;11:444–451. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandura A Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salvy SJ, Coelho JS, Kieffer E, Epstein LH. Effects of social contexts on overweight and normal-weight children’s food intake. Physiol Behav. 2007;92:840–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]