The transition to competency-based medical education (CBME) began in earnest for accredited graduate medical education (GME) programs with the introduction of the Outcome Project in 2001.1 In 2007, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) began exploring Milestones.2 The Next Accreditation System (NAS) launched in 2013 with 3 core aims: strengthen the peer-review accreditation system to prepare physicians for practice in the 21st century, promote the transition to outcomes-based accreditation and medical education, and reduce the burden of traditional structure and process-based approaches.3 The NAS implemented multiple major changes. First, the Milestones defined the 6 general competencies in developmental narrative terms. By 2014, almost all participating GME programs were required to submit semiannual resident Milestones evaluations within the accreditation process. Second, all programs were also required to implement clinical competency committees (CCCs) to use group-based decision-making for judging learner progress.3

Prior to the NAS launch, an international group in 2010 identified 4 overarching principles required for effective CBME: focus on outcomes of the educational process, emphasis on acquirable abilities, learner-centeredness, and deemphasis on time-based education.4 van Melle and colleagues extended these principles with their CBME Core Components Framework.5 This framework (Table 1) identifies 5 essential components for competency-based training programs medical educators must, ideally, address to implement CBME. Table 1 also provides gaps in implementation of these components and offers potential goals and approaches to close those gaps. While this discussion will focus on the fifth core component, programmatic assessment, each of these components is essential in implementing CBME.

Table 1.

Core Components Framework for Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME)a

| Component | Description | Perceived Gap(s) | Goals and Approaches |

| An outcomes-based competency framework |

|

|

|

| Progressive sequencing of competencies |

|

|

|

| Learning experiences tailored to competencies in CBME |

|

|

|

| Teaching tailored to competencies |

|

|

|

| Programmatic assessment |

|

|

|

Adapted from Reference 6.

Operationalizing the NAS continues to be a work in progress. The transition from a time-based model that relies on time and volume proxies to judge competence to an outcomes-based medical education remains a major challenge for the US GME system. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exposed many limitations of a time-based system and disrupted traditional faculty-learner interactions, time-based rotation schedules using fixed learning venues, and previously developed approaches to assessment. Prior to the pandemic, a number of studies showed significant gaps and variability in the assessments used to make decisions about the progression of their learners on the Milestones.6,7 For example, in a study of 14 CCCs by Schumacher and colleagues, only one program reported using multisource feedback, and no programs reported using clinical performance data as part of their program of assessment.8 The ACGME also released guidance last fall for assessment during the pandemic and highlighted the importance of programmatic assessment and the need to still assess all the competencies to ensure graduates are prepared for unsupervised practice.9

Due to the shifting landscape of training venues and individuals conducting direct observation (secondary to redeployment), assessment opportunities have become more challenging.10–12 These new and evolving realities create an opportunity to redouble efforts to realize an outcomes-based GME system. To accelerate change, the GME system and the NAS need to further integrate the original 4 principles with the 5 core components of CBME. One essential area requiring heightened effort is programmatic assessment, essential to fully achieve the promise of outcomes-based education to meet the needs of the public. This perspective presents key aspects of successful programmatic assessment for residencies and fellowships, with a focus on newer concepts to enhance effectiveness.

Programmatic Assessment in the NAS

A core principle of CBME is a program must know that the learner demonstrates the expected level of competence to advance as a trainee. To do so requires clear definitions of desired outcomes and assessment systems that accurately identify whether learners have made sufficient progress and ultimately achieve graduation outcomes. The components of programmatic assessment described in Table 1 are essential to this process.5 High-quality assessment can generate data and insights to support and drive effective feedback, coaching, self-regulated learning, and professional growth.13

System of Programmatic Assessment

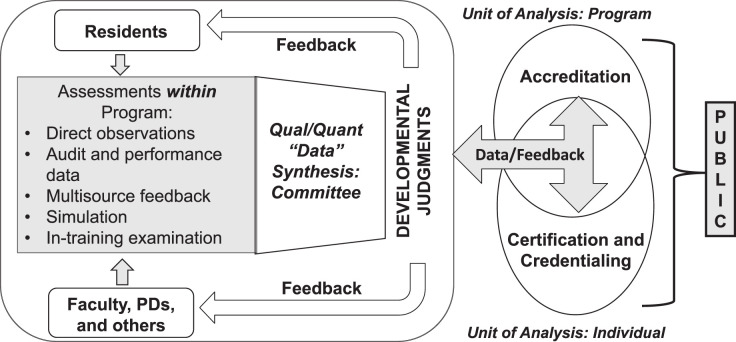

Systems thinking is necessary for effective programmatic assessment. A programmatic assessment system can be defined as a group of individuals who work together on a regular and longitudinal basis to perform, review, and improve assessments.14 Individuals involved in this system include program directors/associate program directors, core faculty, peers, staff, and patients. Additionally, clinical competency committees (CCCs) and program evaluation committees (PECs) convene subgroups of this assessment system to provide individual learner assessment and overall training program assessment. This group must share goals of programmatic assessment, possess shared understanding of clinical and educational outcomes, create interdependent links between individual learner assessments and program evaluation, process information about learner performance (ie, both feedback and feed-forward mechanisms), and commit to producing trainees fully prepared to enter the next phase of their professional careers. Done correctly, systematic programmatic assessment utilizes both qualitative and quantitative data and professional judgement to optimize learning, facilitates decision-making regarding learner progression toward desired outcomes, and informs programmatic quality improvement activities.14

An idealized GME assessment system is represented in Figure 1. As conceptualized in this figure, programmatic assessment includes all the activities within the box and allows for robust data generation using multiple assessment methods and tools to generate data that informs the judgment of the CCC regarding learner progression. This judgement is then presented as a recommendation to the program director while also providing feedback to both faculty and learners. Building programmatic assessment requires implementing an integrated combination of assessment methods and tools for determining a learner's developmental progression in each of the 6 general competencies. While not a complete list, Table 2 provides a core menu of assessment tools/methods appropriate for each general competency.

Figure 1.

The GME Assessment System

Table 2.

Examples of Recommended Core Assessment Tools/Methods By Competency to Support Programmatic Assessment

| Competency | Competency-Based Assessment Options |

| Medical knowledge and clinical reasoning |

|

| Patient care and procedural skills |

|

| Professionalism |

|

| Communication |

|

| Practice-based learning and improvement |

|

| Systems-based practice |

|

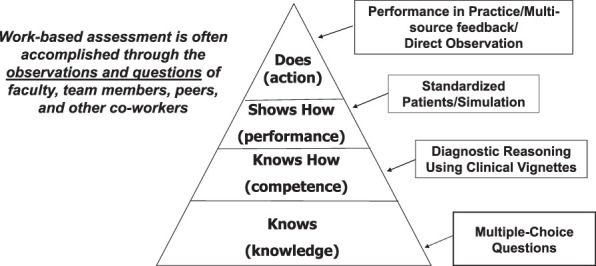

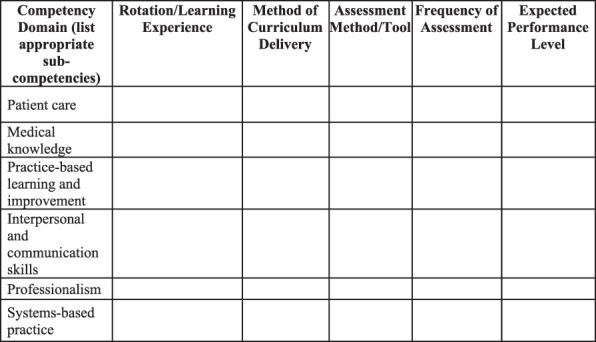

Programmatic assessment should also sample appropriately across all learning venues and at expected levels of learning. The Milestones provide a basic rubric for developmental progression within the competencies. Miller's Pyramid constitutes a useful framework to assist the program in choosing the right type of assessment for the developmental stage of the learner (Figure 2).15 While the emphasis of assessment at the GME level should focus on the “does” of Miller's Pyramid, programmatic assessment should include appropriate approaches across the full continuum of “knows” to “does.” Ultimately, the majority of assessment should focus on work-based assessments such as direct observation, multisource feedback, clinical performance measures, and methods to probe clinical reasoning in patient care. Finally, tracking where, how, and how frequently assessments are being completed will ensure that robust assessment is completed across all necessary competency domains throughout the program (Figure 3). This programmatic assessment “map” is essential in ensuring the core abilities needed by the learner are being taught and assessed.

Figure 2.

Assessing for the Desired Outcome

Figure 3.

Programmatic Assessment Mapping Matrix

Programmatic Assessment and the Human Element

The quality of data generated by assessment programs and individual assessment methods/tools are highly dependent on faculty's capability with them. While energy is routinely spent designing and perfecting assessment tools, most data variability generated by these instruments is due to the human element.16 Rather than pursuing the “perfect tool,” programs are better served ensuring that faculty understand the educational goals and outcomes and have a shared understanding, or mental model, of how the assessment program documents the developmental progression of learners toward those outcomes. It is no longer adequate for assessment to document only what has been learned. This same information must be shared with learners to help catalyze and define their future learning path.17 Assessment and the feedback should address both what has been learned (assessment “of learning”) and the next step in development (assessment “for learning”).

Learner Role in Assessment

The learner's role in assessment has received woefully little attention in medical education. The NAS includes the requirement that residents and fellows develop individualized learning plans and leverage assessment data longitudinally to support their professional development. Learners must understand the role of assessment and utilize assessment data during their training and in preparation for unsupervised practice to support continuous professional development. A philosophy beginning to gain traction in medical education is coproduction.18 Coproduction is based on the principle of restoring individual agency for learning and assessment to the trainee, rather than assuming it rests only with faculty. Coproduction in assessment positions the learner as an active partner generating their own self-assessments, with agency to seek assessment, feedback, and coaching, and help determine what approaches to future learning will be most helpful. These behaviors help struggling learners meet expectations, while ensuring that learners at or above the expected level of competency continue to pursue mastery. Coproduction extends and refines the CBME concept of tailored learning, or learner-centeredness.5

The Role of Milestones and Entrustable Professional Activities in Programmatic Assessment

The NAS Milestones provide a framework for assessing learners' developmental progression in the 6 general competencies. Description of an individual's Milestones progress provides a road map for interpreting rotation-based assessment data (especially work-based assessments) to define that individual's learning trajectories. The Milestones should guide the synthetic judgement completed biannually at the level of the CCC. Milestones were not designed to be used as stand-alone faculty evaluation forms.19 If learner trajectories are consistently missing expected targets in any area of general competency growth, programs should critically review curriculum content, delivery, and assessment to ensure the educational program is providing the appropriate learning environment.20 Through this process, programs can identify and remove or improve ineffective learning and assessment activities as part of programmatic quality improvement.

The Milestones can and will also need to improve. In 2016, the ACGME launched the Milestones 2.0 project to refine and revise all initial Milestones sets.21 Milestones 2.0 addresses the substantial variability in content and developmental progression in the initial subspecialty Milestones and simplifies and standardizes language used to describe developmental progression. The ongoing Milestones 2.0 initiative has identified a set of standardized, or harmonized, subcompetencies in the 4 non–patient care and medical knowledge general competencies. Once complete, this evolution of the subspecialty Milestones will guide programs as they review and update their educational programs to ensure they continue to meet educational outcomes.

As the NAS has evolved, interest in entrustable professional activities (EPAs) has also grown. While use of EPAs is not required for ACGME accreditation, EPAs have gained support as a strategy for structuring clinical assessment. EPAs were introduced by ten Cate as a framework to define and assess essential clinical activities required of the profession.22 EPAs describe the essential work of the profession, whereas Milestones and competencies frame attributes of the learner's abilities. While such EPAs are valuable, programs can also develop customized EPAs to document achievement of desired outcomes for specific rotations (Box 1).

Box 1 EPAs for an Internal Medicine Cardiology Rotationa

-

▪

Evaluate and manage a patient admitted with chest pain.

-

▪

Manage a patient with acute atrial fibrillation and rapid ventricular response.

-

▪

Accurately interpret an ECG.

-

▪

Optimize medical therapy for acute and chronic coronary artery disease.

-

▪

Optimize medical therapy to treat systolic or diastolic heart failure.

-

▪

Manage oral and intravenous anticoagulation therapy.

With permission from John McPherson, MD.

Programmatic Assessment Success

Programmatic assessment must be “fit for purpose.”14 Does an assessment program's combination of tools and methods help determine and guide learners' developmental progression and allow for feedback that informs individual learning plans and program-level improvement? If an assessment is elegantly designed and deployed but does not generate data informing these outcomes, it is insufficient. Hauer and colleagues identified 6 principles of programmatic assessment that can help avoid inadequate programmatic assessment and should be used by all programs as they implement and continuously improve programmatic assessment (Box 2).23

Box 2 Programmatic Assessment Success Principlesa

Ensure a centrally coordinated plan for assessment that aligns with and supports curricular vision.

Utilize multiple assessment tools longitudinally to generate multiple data points.

Ensure learners have ready access to information-rich feedback to promote reflection and informed self-assessment.

Ensure that coaching programs play an essential role in the facilitation of effective data use for reflection and learning planning.

Develop a program of assessment that fosters self-regulated learning behaviors.

Ensure that expert groups (through faculty development) make summative decisions about grades and readiness for advancement.

Adapted from Reference 14.

Conclusions

Programmatic assessment, using a systems-lens, is essential to assure desired outcomes in GME. The elements include high-quality multifaceted assessment methods and tools, group decision-making using best practices in group dynamics, longitudinal and developmental thinking in assessment, and a philosophy of coproduction, with learners as active partners. Without each of these, especially learners as active partners, GME risks production of learners with a limited capacity for self-directed, lifelong learning. The disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has further reinforced the importance of programmatic assessment.

References

- 1.Batalden P, Leach D, Swing S, Dreyfus H, Dreyfus S. General competencies and accreditation in graduate medical education. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21(5):103–111. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green ML, Aagaard EM, Caverzagie KJ, et al. Charting the road to competence: developmental milestones for internal medicine residency training. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(1):5–20. doi: 10.4300/01.01.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1051–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1200117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank JR, Snell LS, ten Cate O, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638–645. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Melle E, Frank JR, Holmboe ES, et al. A core components framework for evaluating implementation of competency-based medical education programs. Acad Med. 2019;94(7):1002–1009. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson RS, Borgert AJ, O'Herion CT, et al. A multicenter prospective comparison of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education milestones: clinical competency committee vs. resident self-assessment. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):e8–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conforti LN, Yaghmour NA, Hamstra SJ, et al. The effect and use of milestones in the assessment of neurological surgery residents and residency programs. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(1):147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schumacher DJ, Michelson C, Poynter S, et al. Thresholds and interpretations: how clinical competency committees identify pediatric residents with performance concerns. Med Teach. 2018;40(1):70–79. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1394576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Guidance Statement on CompetencyBased Medical Education during COVID19 Residency and Fellowship Disruptions. 2021 https://www.acgme.org/Newsroom/Newsroom-Details/ArticleID/10639/Guidance-Statement-on-Competency-Based-Medical-Education-during-COVID-19-Residency-and-Fellowship-Disruptions Accessed February 25.

- 10.American Medical Association. Murphy B. Residency in a pandemic: how COVID-19 is affecting trainees. 2021 https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/residency/residency-pandemic-how-covid-19-affecting-trainees Accessed February 25.

- 11.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Koso R, Siow M. The impact of COVID-19 on orthopaedic residency training. 2021 https://www.aaos.org/aaosnow/2020/jul/covid19/covid-19-res-training/ Accessed February 25.

- 12.Rosen G, Murray S, Greene K, Pruthi R, Richstone L, Mirza M. Effect of COVID-19 on urology residency training: a nationwide survey of program directors by the Society of Academic Urologists. J Uro. 2020;204(5):1039–1045. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Houten-Schat MA, Berkhout JJ, van Dijk N, Endedijk MD, Jaarsma ADC, Diemers AD. Self-regulated learning in clinical context: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2018;52(10):1008–1015. doi: 10.1111/medu.13615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Vleuten CP, Schuwirth LW, Driessen EW, et al. A model for programmatic assessment fit for purpose. Med Teach. 2012;34(3):205–214. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.652239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller G. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9 Suppl):63–67. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams RG, Klamen DA, McGaghie WC. Cognitive, social and environmental sources of bias in clinical performance ratings. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15(4):270–292. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1504_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norcini JM, Anderson B, Bollela V, et al. 2018 consensus framework for good assessment. Med Teach. 2018;40(11):1102–1109. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1500016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Englander R, Holmboe E, Batalden P, et al. Coproducing health professions education: a requisite to coproducing health care service? Acad Med. 2020;95(7):1006–1013. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. The Milestones Guidebook. 2021 https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/MilestonesGuidebook.pdf?ver=2020-06-11-100958-330 Accessed February 25.

- 20.Holmboe ES, Yamazaki K, Nasca TJ, Hamstra SJ. Longitudinal milestones data and learning analytics to facilitate the professional development of residents: early lessons from three specialties. Acad Med. 2020;95(1):97–103. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edgar L, Roberts S, Holmboe E. Milestones 2.0: a step forward. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(3):367–369. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-18-00372.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ten Cate O. Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Med Educ. 2005;39(12):1176–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hauer KE, OSullivan PS, Fitzhenry K, Boscardin C. Translating theory into practice: implementing a program of assessment. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):444–450. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]