In the United States, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Milestones represent a substantial change in graduate medical education (GME) by explicitly defining trainees' developmental progression toward expertise in narrative terms.1 Although this sparked innovation and study in the realm of assessment, there was little accompanying effort to unpack the implications this change would have on the way feedback is approached in GME. The ultimate impact of the Milestones framework depends on the evolution and implementation of an effective longitudinal iterative process for engaging in feedback. Assessment without an effective feedback process is a task half done.

Definitions of feedback in medical education have varied over time. Ende first described feedback as “information describing students' or house officers' performance in an activity that is intended to guide their future performance in that same or related activity.”2 Van de Ridder and colleagues identified the need for an “operational definition” to be used for teaching, faculty development, and research.3 They defined feedback as “specific information about the comparison between a trainee's observed performance and a standard, given with the intent to improve the trainee's performance.”3 More recent studies describe feedback as more than just information, and stress the role of the trainee in the process.4

The Milestones present new challenges to traditional approaches to feedback in medical education. First, the process must allow for trainees and faculty to develop a shared understanding of the Milestones and trainees' developmental progression. Second, Milestones-based feedback must facilitate trainees' growth along their learning trajectory. Third, Milestones assessments and entrustment decisions are generated largely through the work of clinical competency committees (CCCs). This poses the challenge of engaging trainees in feedback from a group, sometimes accomplished through an intermediary such as a program director or designated faculty member. Feedback between the CCC and an individual trainee can be thought of as occurring in a “group-to-trainee” relationship, as opposed to an individual faculty to trainee “one-to-one relationship.”

The existing research on feedback processes provides insight into strategies to meet these challenges.5 These studies provide an understanding of the role of the trainee, their relationship with the feedback provider, and the perceptions they both bring to the process.6–8 The R2C2 feedback model (building relationships, exploring reactions, exploring content of the feedback, and coaching for performance change) by Sargeant and colleagues9 has been studied across multiple specialties and institutions and has been shown to be feasible and adaptable.10 In particular, R2C2 has been studied in the context of Milestones.11 It employs relationship development through a supportive conversation and includes coaching to facilitate trainee implementation of feedback to improve practice. The addition of coaching into the feedback process has been endorsed by others in the field; however, coaching is plagued by the lack of a unified definition.12,13 Here we use the following definition by Armson et al: “Coaching moves a step beyond providing feedback and focuses upon identifying performance goals in response to feedback and developing plans to address them.”14

In this perspective, using the R2C2 model, we present 3 guiding concepts for implementing an effective feedback process in the Milestones era (Box).

Box Take-Home Points for Optimizing Feedback in the Milestones Era

Approach feedback as a coaching activity.

Establish feedback as an iterative process of facilitated self-reflection.

Conceptualize feedback as a group-to-trainee process.

1. Feedback as a Coaching Activity

Incorporating coaching into the feedback process represents a powerful strategy for Milestones-based feedback. Coaching skills should be differentiated from feedback skills. While feedback cultivates insight into current performance, coaching focuses on promoting future improved performance. Faculty serving as coaches help trainees self-reflect on their own assessments. They collaborate in the identification of priority performance gaps and areas for improvement.14 This empowers trainees to drive their own professional development. Coaches ensure plans are viable and confirm that goals are achieved. Faculty as coaches are invested in a longitudinal relationship with trainees. Watling and LaDonna identified shared “philosophies” of coaches across contexts involving medicine and other fields (ie, coaches strive to unlock the potential of their trainees, encourage reflective practice skills, and recognize that failure is a key motivator for improvement).15 In addition, coaches use the language of partnership to achieve goals.15 Successful outcomes utilizing a coaching approach depend on faculty maintaining a balance between encouraging self-direction, while ensuring patient safety and progression to competence.14

2. Feedback as an Iterative Process of Facilitated Self-Reflection

Role of Iteration

Medical educators often engage in a feedback process that is a content-delivery activity from faculty to trainee.8 They may measure the success of feedback by the verbal acceptance of the learner, not by the incorporation of feedback into improved performance. However, feedback is not realized until the learner has done something with it.16 A successful Milestones feedback process must be iterative, and reassessment of previously identified goals must serve to link each feedback conversation. The R2C2 model lends itself well to this end. Faculty begin by asking probing questions of trainees such as: “What do you want to get out of this feedback session?” “Did anything in your assessment surprise you? Tell me more about that…”11 This builds relationships and requires self-assessment. The process provides the opportunity for faculty and trainee to start creating a shared understanding of performance relative to the Milestones. Also, faculty inferences can be dispelled and contextual factors that impact observed performance are revealed. Content in the form of external assessments, including those coming from a CCC, are woven into a shared understanding of current performance. In the coaching phase faculty and trainee work together to generate a learning action plan.17 Subsequently, this learning plan becomes part of the next feedback conversation.11 This supports feedback as a coproduced process between the trainee, CCC, and faculty.11,14

Facilitated Self-Reflection

Simply providing assessment data, including the detailed Milestones narratives, to the trainee without conversation can be unhelpful and frustrating.18,19 Kluger and DeNisi's review of feedback interventions demonstrated that feedback can be harmful or at best unproductive depending on the intervention.20 Additional research from the health services domain revealed that providing quality data without support or guidance has minimal effects on behavioral change.21 Milestones narratives were envisioned to provide clarity to both trainees and faculty with respect to what competency looks like as it is achieved through stages. However, as these studies have suggested, the value of the Milestones can only be realized through a supportive conversation that enhances the trainees' understanding. The feedback process that best enables this exercise is facilitated self-reflection.22,23 R2C2 employs facilitated self-reflection using probing questions that illicit the trainee's evaluation of their own performance. Faculty subsequently help the trainee reconcile that self-assessment with the assessment of others through dialogue. Engaging in this process iteratively should increase the possibility that trainees develop necessary self-assessment skills and employ those skills for continued professional development post-training.16

3. Feedback as a “Group-to-Trainee” Process

In medical education, feedback has traditionally been conceptualized as occurring in a one-on-one configuration (ie, between a faculty member and a trainee).2,5 However, in the Milestones era, feedback also occurs between decision-making groups and learners (ie, between a CCC and a trainee). There are important considerations that the “group-to-trainee” feedback scenario uncovers. For example, depending on the size of the training program, faculty on these committees may find themselves in a dual role (ie, as both judge and coach); feedback generated for multiple trainees at a time may no longer be timely or specific, and trainees' receptivity to the feedback may depend on their relationship to the members of the CCC. Acceptance of feedback by the trainee is affected by the perceived credibility of the source4; however, the manner in which trainees perceive the credibility of feedback content when the source is a committee and not an individual is unclear. Trainees' acceptance of feedback is also influenced by their perceptions about their relationship to faculty, manner of feedback delivery, intentions of the faculty, whether performance was observed, and alignment between self-assessment and feedback.4,24 This evidence suggests issues that may be problematic as we embark on feedback between CCCs and trainees, even if the feedback from the CCC is delivered via a single individual. Using the R2C2 model to envision the feedback relationship between a group and a trainee, the following are some ideas for implementation:

-

▪

Relationship building between CCCs and trainees can occur by fostering “buy-in” to the feedback process. CCCs need to be transparent about their processes, including who the committee members are, which assessment data are used for decision-making, and how the committee approaches the rating process.

-

▪

Reactions to the feedback: Trainees should be encouraged to respond to the feedback, including their understanding of the main points and document their reactions. Such documentation can aid in defining the content of their individualized learning plans.

-

▪

Content: CCCs will need to consider how their feedback based on data aggregated over multiple learning experiences is different from that generated by a single faculty member over a single experience.

-

▪

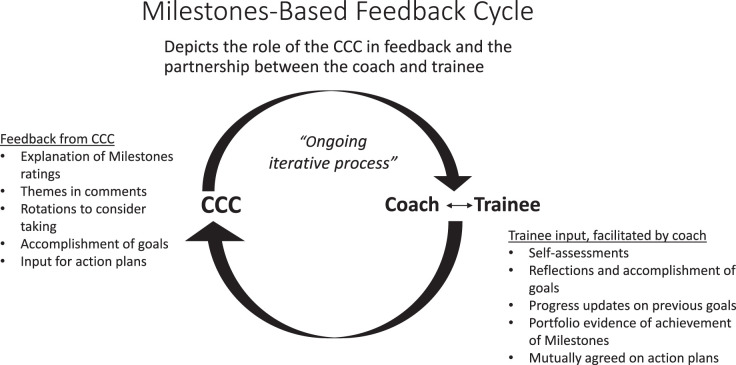

Coaching: Depending on the training program, CCC members may or may not be directly involved in coaching trainees. Regardless, they have an opportunity to collaborate with those that do to ensure that the CCC feedback is clear and there is a plan to work with the trainee on the key elements. Watling and colleagues found that the use of a coach not only facilitates the perception of accurate assessments of trainee performance but also of feedback that is well intentioned.12 A dedicated longitudinal clinical coach can enhance transparency for the learner around the “black Box” of committee assessment. This is in accord with Voyer and colleagues who found that trainees perceived the feedback process to be more credible when it was rooted in direct observation of their performance and delivered in a nonassessment longitudinal format.25 The addition of a coach may lend credibility to the group process necessary for acceptance of feedback (Figure).

Figure.

Milestones-Based Feedback Cycle

Conclusions

The Milestones framework is developmental, which implies that the progression to unsupervised practice is a process of longitudinal growth. We advocate reenvisioning feedback as an iterative process, supported by the philosophy and skills of a coaching relationship, which encourages the acceptance and credibility of the “group-to-trainee” dynamic. Approaching Milestones feedback in this manner may empower faculty and trainees to partner in a process that fosters professional growth.

References

- 1.Nasca T, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn T. The next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1051–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1200117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983. 250(6)777–781. [PubMed]

- 3.Van de Ridder M, Stokking J, McGaghie W, ten Cate O. What is feedback in clinical education? Med Educ 42(2):189–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02973.x. . 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramani S, Koenings K, Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten C. Twelve tips to promote a feedback culture with a growth mind-set: Swinging the feedback pendulum from recipes to relationships. Med Teach. 2019;41(6):625–631. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1432850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bing-You R, Varaklis K, Hayes V, Trowbridge R, Kemp H, McKelvy D. The feedback tango: an integrative review and analysis of the content of the teacher-learner feedback exchange. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):657–663. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watling C, Lingard L. Toward meaningful evaluation of medical trainees: the influence of participants' perceptions of the process. Adv in Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2012;17(2):183–194. doi: 10.1007/s10459-010-9223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boud D. Feedback: ensuring that it leads to enhanced learning. Clin Teach. 2015;12(1):3–7. doi: 10.1111/tct.12345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Telio S, Ajjawi R, Regeher G. The “educational alliance” as a framework for reconceptualizing feedback in medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):609–614. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sargeant J, Lockyer J, Mann K, et al. Facilitated reflective performance feedback: developing an evidence- and theory-based model that builds relationship, explores reactions and content, and coaches for performance change (R2C2) Acad Med. 2015;90(12):1698–1706. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lockyer J, Armson H, Konings K, et al. In-the-moment feedback and coaching: improving R2C2 for a new context. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(1):27–35. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-19-00508.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sargeant J, Lockyer JM, Mann K, et al. The R2C2 Model in residency education: how does it foster coaching and promote feedback use? Acad Med. 2018;93(7):1055–1063. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watling C, Driessen E, van der Vleuten CPM, Lingard L. Learning culture and feedback: an international study of medical athletes and musicians. Med Educ. 2014;48(7):713–723. doi: 10.1111/medu.12407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lovell B. Bringing meaning to coaching in medical education. Med Educ. 2019;53(5):426–427. doi: 10.1111/medu.13833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armson H, Lockyer JM, Zetkulic MG, Konings KD, Sargeant J. Identifying coaching skills to improve feedback use in postgraduate medical education. Med Educ. 2019;53(5):477–493. doi: 10.1111/medu.13818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watling C, LaDonna K. Where philosophy meets culture: exploring how coaches conceptualize their roles. Med Educ. 2019;53(5):467–476. doi: 10.1111/medu.13799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinstein D. Feedback in medical education: untying the Gordian knot. Acad Med. 2015 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000559. 90(5)559–561. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Wakefield J. Commitment to change: exploring its role in changing physician behavior through continuing education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2004;24(4):197–204. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340240403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boud D, Molloy E. Feedback in Higher and Professional Education Understanding it and Doing it Well 1st ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raaum S, Lappe K, Colbert-Getz JM, Milne C. Milestone implementation's impact on narrative comments and perception of feedback for internal medicine residents: a mixed methods study. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):929–935. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04946-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kluger A, DeNisi A. The effects of feedback interventions on performance: a historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychol Bull. 1996;119(2):254–284. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3. (6):CD000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Sargeant J, Armson H, Chesluk B, et al. The processes and dimensions of informed self-assessment: a conceptual model. Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1212–1220. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d85a4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lefroy J, Watling C, Teunissen PW, Brand P. Guidelines: the do's, don'ts and the do not knows of feedback for clinical education. Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4(6):284–299. doi: 10.1007/s40037-015-0231-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watling C. Cognition, culture, and credibility: deconstructing feedback in medical education. Perspect Med Educ. 2014;3(2):124–128. doi: 10.1007/s40037-014-0115-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voyer S, Cuncic C, Butler DL, MacNeil K, Watling C, Hatala R. Investigating conditions for meaningful feedback in the context of an evidence-based feedback programme. Med Educ. 2016;50(9):943–954. doi: 10.1111/medu.13067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]