BACKGROUND

Fibrous septae play a role in contour alterations associated with cellulite.

OBJECTIVE

To assess collagenase clostridium histolyticum-aaes (CCH) for the treatment of cellulite.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Two identically designed phase 3, double-blind, randomized studies (RELEASE-1 and RELEASE-2) were conducted. Adult women with moderate/severe cellulite (rating 3–4 on the Patient Reported Photonumeric Cellulite Severity Scale [PR-PCSS] and Clinician Reported PCSS [CR-PCSS]) on the buttocks received up to 3 treatment sessions of subcutaneous CCH 0.84 mg or placebo per treatment area. Composite response (≥2-level or ≥1-level improvement from baseline in both PR-PCSS and CR-PCSS) was determined at Day 71.

RESULTS

Eight hundred forty-three women received ≥1 injection (CCH vs placebo: RELEASE-1, n = 210 vs n = 213; RELEASE-2, n = 214 vs n = 206). Greater percentages of CCH-treated women were ≥2-level composite responders versus placebo in RELEASE-1 (7.6% vs 1.9%; p = .006) and RELEASE-2 (5.6% vs 0.5%; p = .002) and ≥1-level composite responders in RELEASE-1 (37.1% vs 17.8%; p < .001) and RELEASE-2 (41.6% vs 11.2%; p < .001). Most adverse events (AEs) in the CCH group were injection site related; few CCH-treated women discontinued because of an AE (≤4.3%).

CONCLUSION

Collagenase clostridium histolyticum-aaes significantly improved cellulite appearance and was generally well tolerated.

Cellulite is an alteration in skin topography that affects between 80% and 98% of postpubertal women and results in a dimpled appearance of the affected skin.1–4 The high prevalence of cellulite in women is associated with sex-specific differences in the anatomy of the skin and subcutaneous tissue and may be driven by estrogen.2,4,5 These differences include a less regular dermal–subcutaneous interface or different configuration of subcutaneous tissue and fat-cell chambers, allowing fat herniation6; differences in fat lobulation, amount, and distribution4,5; and differences in the number, type, orientation, and inter-relatedness of fibrous septae.4–7 Women with cellulite can experience emotional distress and negative feelings that can detrimentally affect self-esteem and quality of life.8

Fibrous septae play an important role in contour alterations associated with cellulite.9,10 Successful clinical outcomes with cellulite treatments that target the fibrous septae10–16 provide evidence that the pathophysiology of cellulite can be attributed to structural and biomechanical properties at the subdermal junction, leading to an imbalance between containment and extrusion forces.5 Even with this understanding of the pathophysiology of cellulite, there remains an unmet need for safe and effective microinvasive, injectable therapies to improve aesthetic outcomes for women.

Collagenase clostridium histolyticum-aaes (CCH; QWO, Endo Aesthetics LLC, Malvern, PA) for injection is composed of 2 purified bacterial collagenases (AUX-I and AUX-II [Clostridial class I and II collagenases]) that hydrolyze Type I and III collagen with high specificity under physiologic conditions, resulting in disruption of targeted collagen structures.17 It was approved in the United States in July 2020 for the treatment of moderate-to-severe cellulite in the buttocks of adult women. A different formulation of collagenase clostridium histolyticum (0.58 mg; Xiaflex, Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc., Malvern, PA) is indicated in the United States for the treatment of collagen-associated disorders (i.e., adults with Dupuytren contracture with a palpable cord or Peyronie's disease [PD] in adult men with palpable plaque and penile curvature deformity of ≥30° at treatment initiation).17 The mechanism of action of CCH for cellulite-related contour alterations in women is enzymatic disruption of the fibrous septae, to create a skin-smoothing effect.18 In a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 375 women with moderate to severe cellulite on the buttocks or posterolateral thighs, subcutaneous CCH administered at a dose of 0.84 mg per treatment area every 21 days for up to 3 sessions significantly improved the appearance of cellulite versus placebo based on both clinician and patient ratings; CCH was generally well tolerated.18 Most adverse events (AEs) occurred at the site of injection, were mild to moderate in intensity, and resolved within 2 to 3 weeks without intervention. The objectives of the current studies were to assess the efficacy and safety of CCH in the treatment of cellulite on the buttocks.

Methods

Trial Design and Study Population

Two identically designed, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 studies, Randomized Evaluation of Cellulite Reduction by Collagenase Clostridium Histolyticum (RELEASE-1 and RELEASE-2), were conducted at 26 and 25 US study centers (See Supplemental Digital Content 1, Supplementary Table S1, http://links.lww.com/DSS/A686), respectively (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT03428750 [RELEASE-1]; NCT03446781 [RELEASE-2]). Participants were healthy women ≥18 years of age who were not pregnant or lactating and who had a rating of 3 or 4 on the Clinician Reported Photonumeric Cellulite Severity Scale (CR-PCSS) and Patient Reported Photonumeric Cellulite Severity Scale (PR-PCSS) on both buttocks.18 Women with severe skin laxity, flaccidity, or sagging skin; with inflammation or an active infection; and/or with tattoo(s) located within 2 cm of the areas to be evaluated were excluded. Women were willing to apply sunscreen on the buttocks before each sun exposure for the study duration. Additional exclusion criteria were current treatment for cellulite or use, within the previous 12 months, of injectables, laser treatment, liposuction, radiofrequency treatment, implants, cryolipolysis, or surgery for cellulite in the areas to be evaluated. Women who used an anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication within 7 days before injection, as well as those who needed to receive anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication (except aspirin ≤150 mg/d) during the study, were excluded. During the study, women were not permitted to use tanning spray or tanning booths, or to initiate intense sports, exercise, or weight-loss programs. The study protocols were reviewed and approved by a central institutional review board (Advarra, Columbia, MD) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. All women provided written informed consent.

Treatment

On Day 1 after participant eligibility was confirmed, 1 buttock was randomly assigned, in a double-blind manner, as the target for evaluating the primary efficacy end point. The remaining buttock was identified as the nontarget buttock. Subsequently, the women were randomly assigned in a double-blind manner (1:1 ratio within each study center) using an interactive web response system to receive either subcutaneous CCH 0.84 mg or placebo for both the target and nontarget buttock. For the target and nontarget buttock, investigators identified dimples for treatment that were visible and well defined when the woman was standing. Each woman received up to 3 treatment sessions in the prone position (i.e., lying face down) separated by approximately 21 days (e.g., Days 1, 22, and 43). Each injection was administered as three 0.1-mL aliquots with 1 aliquot perpendicular to the skin and 2 aliquots at a 45-degree angle superior or inferior to the perpendicular axis; the same injection technique was used for all dimples. The depth of injection corresponded to the length of the treatment needle (0.5 inches) from the tip of the needle to the hub or base of the needle, without downward pressure. Figure 1 depicts the injection technique in the trials (see Supplemental Digital Content 2, video online [Supplemental Digital Video], http://links.lww.com/DSS/A687 which demonstrates the injection technique). Up to 12 dimples in each buttock were injected during a treatment session using this technique.

Figure 1.

Still shot from an injection technique video used to train study investigators. (To view the full video, please see the link in the article text.) The video demonstrates that the CCH injections are administered as three 0.1-mL aliquots, with 1 aliquot administered perpendicular to the skin and the other 2 aliquots administered at a 45-degree angle superior or inferior to the perpendicular axis. Reprinted with permission from Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. 2020 All rights reserved.

Assessments

Standardized, identical digital photographic set-up and process procedures were followed in the 2 trials to ensure consistent evaluation of cellulite severity. At screening and scheduled treatment or unscheduled clinical visits, the entire right or left buttock was individually photographed (with relaxed gluteus muscles while standing) using the Vectra M1 IntelliStudio system (Canfield Scientific, Inc., Parsippany, NJ). Parameters standardized for each photographic session included lighting, reference photograph on screen to assist with alignment, feet positioning, relaxed posture of individual being photographed, distance of camera to buttock being photographed (2 convergent laser beams were aligned on the buttock surface), and camera height.

Cellulite severity was rated for the target and nontarget buttocks using the CR-PCSS (live assessment) and PR-PCSS (digital images) at screening; before treatment on Days 1, 22, and 43 (±3 days for Days 22 and 43) and 28 days post-treatment on Day 71 (+5 days). After completion of the PR-PCSS assessment on Days 22, 43, and 71, women also rated improvement after treatment compared with baseline (digital images) using the Subject Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (S-GAIS)19 for the target and nontarget buttock. On Days 1 and 71, the Patient Reported Cellulite Impact Scale (PR-CIS) assessment was also completed (digital images). This PR-CIS encompasses a 6-item questionnaire (domains of happy, bothered, self-conscious, embarrassed, looking older, or looking overweight or out of shape) to assess the visual and emotional impact of cellulite (See Supplemental Digital Content 1, Table S2, http://links.lww.com/DSS/A686). Each item is rated on a Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely). On Day 71, women rated their satisfaction with their cellulite treatment on a 5-point scale that ranged from “very satisfied” to “very dissatisfied” (See Supplemental Digital Content 1, Supplemental Table S3, http://links.lww.com/DSS/A686).

Safety assessments included monitoring of treatment-emergent AEs, vital signs, and clinical laboratory parameters, as well as immunogenicity testing. Adverse events coded as injection-site hemorrhage, ecchymosis, or bruising were classified together as injection-site bruising. Binding AUX-I and binding AUX-II antibody levels were determined on Days 1, 22, 43 (±3 days for Days 22 and 43), and 71 (+5 days).

Study End Points

The primary efficacy end point was the percentage of ≥2-level composite responders (women with ≥2-level severity improvement from baseline in both CR-PCSS rating and PR-PCSS rating) in the target buttock at Day 71 in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population. Key secondary efficacy end points (ITT population) included the percentage of ≥1-level composite responders (women with ≥1-level severity improvement from baseline in both CR-PCSS rating and PR-PCSS rating) in the target buttock at Day 71, the percentage of ≥2-level composite responders in the nontarget buttock at Day 71, the percentage of women with a ≥2-level or ≥1-level improvement in PR-PCSS rating in the target buttock at Day 71, the percentage of women with a ≥2-level or ≥1-level improvement in the S-GAIS score in the target buttock at Day 71, and the change from baseline to Day 71 in the total PR-CIS score. The percentage of women with subject satisfaction of “satisfied” or “very satisfied” and the percentage of ≥1-level composite responders in the nontarget buttock at Day 71 were supportive end points.

Statistical Analysis

For each of the identically designed trials, the sample size was estimated based on the assumption that the percentage of ≥2-level composite responders for the target buttock would be ≥ 12% in the CCH group and ≤3% in the placebo group (odds ratio ≥4.4), with a participant discontinuation rate of ∼10%. With these assumptions, each trial needed a sample size of 420 women randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to the 2 treatment groups. This distribution of women was intended to provide ≥90% power with a type 1 error of 0.05 to detect statistically significant changes in the primary and key secondary end points. All women randomly assigned to treatment who received ≥1 injection of study medication were included in the ITT and safety populations. Data for the primary and key secondary efficacy end points and for the percentage of women who were satisfaction responders (i.e., “satisfied” or “very satisfied”) were analyzed using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test, with adjustment for study center. The change from baseline to Day 71 in the PR-CIS total score was evaluated by analysis of covariance with the treatment group and analysis center as factors after adjustment for the baseline value. Women with missing efficacy data at Day 71 were considered nonresponders. Demographics, safety, and immunogenicity data were summarized using descriptive statistics. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS statistical software package Version 9.3 or higher (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Clinically meaningful change was estimated using anchor-based methods, based on guidance from the US FDA.20 The S-GAIS served as the anchor for the PR-PCSS. The ability of the PR-PCSS to detect change in cellulite severity was analyzed using pooled data from the 2 studies. Outcomes were determined using PR-PCSS (dependent variable) and S-GAIS (independent variable) data analyzed with a Kruskal–Wallis 1-way analysis of variance model to determine the clinically meaningful change thresholds.

Results

Study Disposition

RELEASE-1 was conducted from February 5, 2018, to September 26, 2018, and RELEASE-2 was conducted from February 8, 2018, to September 26, 2018. Of 1,319 women screened, 845 were enrolled (n = 2 discontinued before treatment), and 843 women (CCH 0.84 mg, n = 424; placebo, n = 419) were included in the ITT population for the 2 studies (See Supplemental Digital Content 1, Figure S1, http://links.lww.com/DSS/A686). The most common reasons for study discontinuation in either treatment group in the 2 studies were withdrawal of consent and lost to follow-up (See Supplemental Digital Content 1, Supplemental Figure S1, http://links.lww.com/DSS/A686). A total of 755 women completed the 2 studies. Demographic and baseline characteristics in the ITT population were similar between the 2 treatment groups for both studies (See Supplemental Digital Content 3, Table S4, http://links.lww.com/DSS/A755). The mean age was ∼47 years for women in both studies. Approximately 60% and 40% of women were assigned to the Fitzpatrick scale categories I–III and IV–VI, respectively.

Efficacy

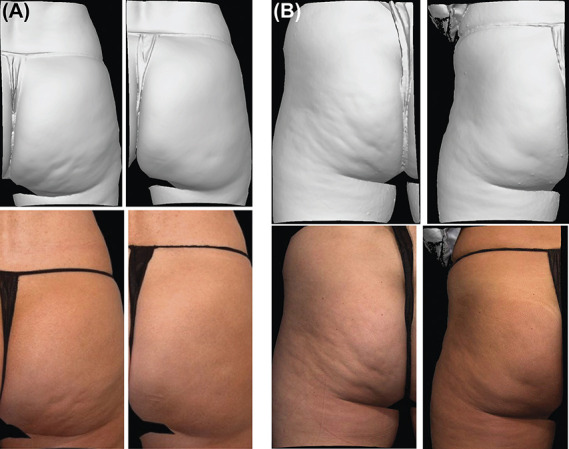

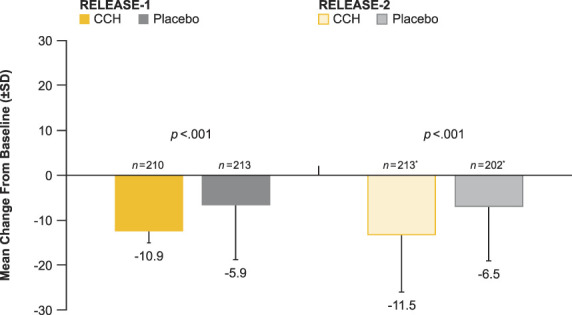

Significantly greater percentages of women treated with CCH were ≥2-level composite responders in both the CR-PCSS and PR-PCSS for the target buttock at Day 71 (primary efficacy end point) compared with placebo in both studies (RELEASE-1, p = .006; RELEASE-2, p = .002). In addition, a significantly greater percentage of women were ≥1-level composite responders for the target buttock at Day 71 compared with placebo (RELEASE-1 and -2, p < .001 for both; Figure 2). The percentages of ≥2-level and ≥1-level composite responders at Day 71 in the nontarget buttock (See Supplemental Digital Content 1, Figure S2, http://links.lww.com/DSS/A686) were similar to the percentages for the target buttock in both studies. Photographic images of a 2-level (Figure 3A) and 1-level (Figure 3B) composite response show improvement in skin topography at Day 71 after treatment with CCH compared with baseline. In addition, both studies showed significant improvements (p < .001 for all) from baseline to Day 71 for women treated with CCH compared with those receiving placebo for PR-PCSS (≥1-level improvement), S-GAIS (≥1- and ≥2-level improvements; Figure 4), and PR-CIS total score (Figure 5) ratings.

Figure 2.

Composite responders, defined as patients with ≥2-level or ≥1-level severity improvement from baseline in both CR-PCSS and PR-PCSS ratings at Day 71. CCH, collagenase clostridium histolyticum-aaes; CR-PCSS, Clinician Reported Photonumeric Cellulite Severity Scale; PR-PCSS, Patient Reported Photonumeric Cellulite Severity Scale; RELEASE, Randomized Evaluation of Cellulite Reduction by Collagenase Clostridium Histolyticum.

Figure 3.

Photographs of composite response with CCH 0.84 mg compared with baseline. Baseline and Day 71 photographs demonstrate a 2-level improvement in both the CR-PCSS and PR-PCSS (A) and a 1-level improvement in both the CR-PCSS and PR-PCSS (B). CCH, collagenase clostridium histolyticum-aaes; CR-PCSS, Clinician Reported Photonumeric Cellulite Severity Scale; PR-PCSS, Patient Reported Photonumeric Cellulite Severity Scale. Reprinted with permission from Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. © 2020 All rights reserved.

Figure 4.

Frequency of responders for PR-PCSS and S-GAIS at Day 71 in the ITT population. CCH, collagenase clostridium histolyticum-aaes; ITT, intent-to-treat; PR-PCSS, Patient Reported Photonumeric Cellulite Severity Scale; RELEASE, Randomized Evaluation of Cellulite Reduction by Collagenase Clostridium Histolyticum; S-GAIS, Subject Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale.

Figure 5.

Mean improvement from baseline in the PR-CIS total score at Day 71 in the mITT population. CCH, collagenase clostridium histolyticum-aaes; mITT, modified intent-to-treat; PR-CIS, Patient Reported Cellulite Impact Scale; RELEASE, Randomized Evaluation of Cellulite Reduction by Collagenase Clostridium Histolyticum. *Baseline values were used for women who did not have a Day 71 PR-CIS assessment.

Ability to detect change for the PR-PCSS demonstrated that the 1-level improvement change threshold was indicative of clinically meaningful change for women because this level of change was associated with ratings of improvement on the S-GAIS as an external anchor variable. In both studies, a greater percentage of patients treated with CCH versus placebo also experienced a ≥2-level improvement in PR-PCSS (RELEASE-1, p = .001; RELEASE-2, p < .001). Significantly more women treated with CCH than placebo were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with their treatment at Day 71 (RELEASE-1, 54.3% [n = 100] vs 25.8% [n = 49; p < .001]; RELEASE-2, 46.8% [n = 87] vs 13.6% [n = 26; p < .001]).

Safety

Collagenase clostridium histolyticum-aaes was generally well tolerated in both studies, with a low rate of discontinuations due to AEs (See Supplemental Digital Content 3, Table S5, http://links.lww.com/DSS/A755). Ten women discontinued the study because of an AE in RELEASE-1 (CCH 0.84 mg, n = 9 [4.3%]; placebo, n = 1 [0.5%]) and in RELEASE-2 (CCH 0.84 mg, n = 8 [3.7%]; placebo, n = 2 [1.0%]; See Supplemental Digital Content 3, Table S5, http://links.lww.com/DSS/A755). The most common AEs leading to discontinuation with CCH were injection-site reactions. Most AEs in the 2 studies were injection site related, occurred more frequently with CCH versus placebo, were mild to moderate in intensity, and resolved without treatment (See Supplemental Digital Content 3, Table S5, http://links.lww.com/DSS/A755). Of the treatment-related AEs reported, 81.8% (RELEASE-1) and 84.1% (RELEASE-2) resolved within 21 days, with most treatment-related AEs in CCH-treated women resolving within 14 days (60.5% and 65.9% in CCH-treated women in RELEASE-1 and RELEASE-2, respectively). More specifically, most (54.6% [RELEASE-1] and 53.6% [RELEASE-2]) treatment-related injection-site bruising resolved within 14 days, and most (55.0% [RELEASE-1] and 60.0% [RELEASE-2]) injection-site pain AEs resolved within 7 days in CCH-treated women. Notably, the rate of these 2 AEs numerically decreased with subsequent treatment sessions. A higher percentage of women reported injection-site bruising after the first treatment session (RELEASE-1, 74.8%; RELEASE-2, 86.9%) compared with the second (RELEASE-1, 61.1%; RELEASE-2, 67.9%) or third treatment sessions (RELEASE-1, 40.6%; RELEASE-1, 47.5%). For injection-site pain, a similar trend to decrease was observed (first treatment session: RELEASE-1, 33.3%; RELEASE-2, 55.1%; second treatment session: RELEASE-1, 22.7%; RELEASE-2, 37.8%; third treatment session: RELEASE-1, 10.2%; RELEASE-2, 27.1%). No deaths were reported in either study. In RELEASE-1, one woman treated with placebo experienced a serious AE of ischemic colitis; in RELEASE-2, one woman treated with CCH experienced serious AEs of hypokalemia, hypotension, and syncope, which were not considered by the investigator to be related to CCH treatment. No clinically meaningful changes in body weight or body mass index were observed, and no serious hypersensitivity reactions were reported in either study.

In the CCH treatment group at Day 71, 100% (n = 182 for both antibodies, RELEASE-1; n = 180 for both antibodies, RELEASE-2) of women in both studies who received treatment during all 3 of the possible sessions developed binding AUX-I and binding AUX-II antibodies. The presence of neutralizing antibodies in RELEASE-1 to AUX-I and AUX-II was observed in 66.7% (n = 32) and 78.3% (n = 36) of women, respectively; in RELEASE-2, the presence of neutralizing antibodies to AUX-I and AUX-II was observed in 68.8% (n = 33) and 87.5% (n = 42) of women, respectively.

Discussion

To meet the primary efficacy end point of RELEASE-1 and RELEASE-2, patients were required to have a ≥2-level improvement from baseline in cellulite severity for both PCSS scales (CR-PCSS and PR-PCSS). This is a stringent criterion for clinical practice. However, significant improvements were observed with CCH versus placebo for the treatment of cellulite in both of these identically designed, randomized, placebo-controlled studies. It is challenging to compare results across studies using different cellulite severity scales and place the findings in context to treatment of women in clinical practice, but generally a 1-point reduction in cellulite severity (6-point cellulite severity scale based on number and depth of dimples) is typically an acceptable response in clinical practice.13,18 Anchor-based analyses in the current studies indicated a PR-PCSS score change ≥1 was clinically meaningful. Over half of the women treated with CCH in both studies had an improvement in PR-PCSS rating ≥1 (54.3% and 57.9%). A composite ≥1-level response in both PR-PCSS and CR-PCSS was observed in >35% of women, and a ≥1-level S-GAIS response was observed in >55% of women. Furthermore, based on the change from baseline in PR-CIS total scores, women treated with CCH reported a lower overall visual and emotional impact of cellulite post-treatment compared with placebo-treated women. This is consistent with other studies that have shown patients' perceptions of cellulite improvement after treatment can improve quality of life and self-esteem.13,21

Several studies have reported on the potential benefit of cellulite treatments that target the fibrous septae by subcision.10–16 Collagenase clostridium histolyticum-aaes is a different approach that improves topography of the skin through enzymatic disruption of the fibrous septae.18 Recent findings suggest that the pathophysiology of cellulite can be attributed to structural and biomechanical properties at the subdermal junction that lead to an imbalance between containment and extrusion forces5 which, in turn, produce the dimpled appearance characteristic of cellulite.1,2,4 One type of skin irregularity, laxity, is characterized by the skin that is permanently distended and sags.22 In a study of the reliability of the Hexsel Cellulite Severity Scale, skin laxity did not contribute to the internal consistency of the scale, and therefore, contour alterations because of skin laxity should not be mischaracterized as cellulite.23,24

Collagenase clostridium histolyticum-aaes was safe and generally well tolerated in both studies. The most common AEs with CCH administration were injection site-related. Adverse events resolved quickly, were mild to moderate in intensity, and were infrequent causes of study discontinuation (<5% of women in either study). Injection site–related AEs such as injection-site pain and bruising were the most common AEs and occurred more often in women treated with CCH. Given that most CCH-treated patients experienced ≥1 injection-site AE (e.g., bruising), this may have impacted the decision of some patients to withdraw or become lost from follow-up to the study, in addition to other unknown reasons. However, the combined percentage of patients with consent withdrawn or lost to follow-up was generally similar between CCH (6.7% and 9.3% for RELEASE-1 and RELEASE-2, respectively) and placebo (8.9% and 5.8%, respectively). There was a trend in the number of women who reported injection-site pain and bruising to decrease after subsequent treatment sessions. Formal assessment of whether women considered bruising AEs painful was not carried out as part of the study protocol, although anecdotal reports from investigators suggested that the bruising observed following CCH injection was not painful for patients. Further investigation is needed to determine the mechanism of action associated with CCH-related bruising. The intensity, duration, and characteristics of injection-site AEs reported after CCH administration in the current 2 studies were similar to results from a phase 2 study with CCH18 and also similar to data reported after collagenase injection in patients with Dupuytren disease [DD] or PD,25–27 using a different formulation from that being evaluated for the treatment of cellulite.

All women in both studies were seropositive for binding AUX-I and binding AUX-II antibodies; this was not unexpected, based on findings of a phase 2 study with CCH18 and clinical and postmarketing surveillance of collagenase administration.25 Immunogenicity profiling has shown that administration of collagenase25 or CCH18 can result in seropositivity for binding AUX-I and/or binding AUX-II antibodies. Although patients with DD may continue to be seropositive for binding AUX-I and binding AUX-II antibodies at 5 years post-treatment,25 there is no evidence that the presence of neutralizing antibodies has an effect on clinical response or the frequency of AEs.17,25 A completed open-label extension study of CCH for cellulite addresses long-term immunogenicity and potential for tachyphylaxis with repeated exposure to CCH (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02942160).

Key strengths of the current studies included them constituting the largest combined patient population (N = 843) for cellulite research purposes to date, and the multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design of each study. Another strength was the broad study entry criteria, including women with severe cellulite. Among women with severe cellulite at baseline who were then treated with CCH, >15% assessed by the CR-PCSS and >35% assessed by the PR-PCSS had improvement in the target buttock at Day 71. As noted previously, the primary end point, a ≥2-level composite improvement from baseline, is considered a stringent criterion; this is a limitation, given this outcome is difficult to achieve in clinical practice. Despite this stringent criterion, however, a significantly larger percentage of women receiving CCH met the primary end point compared with placebo. An additional limitation was the use of the same injection technique regardless of dimple depth, which was necessary to standardize the procedure across study sites in the 2 trials. Additional injection technique approaches are being investigated in clinical trials. In conclusion, based on 2 phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled studies, CCH is a safe and efficacious treatment for women with moderate to severe cellulite of the buttocks.

Acknowledgments

Mary Beth Moncrief, PhD, and Julie B. Stimmel, PhD, Synchrony Medical Communications, LLC, West Chester, PA, were compensated by Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc., Malvern, PA, to work collaboratively with the authors in developing the article. Data interpretation and final content included in the publication were determined solely by the authors. The authors thank the following Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. employees for their contributions toward these clinical trials: Clinical Operations: Rosalie Filling, Vice President, and Davina Cupo, Associate Director; Clinical Data Management: Jamie Kistner, Director; and Medical Writing: Laura Sheppard, Director. The authors also thank the investigators who participated in the 2 trials (See Supplemental Digital Content 1, Supplemental Table S1, http://links.lww.com/DSS/A686).

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the full text and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (www.dermatologicsurgery.org).

Supported by Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc., Malvern, PA.

J. H. Joseph is a shareholder and an investigator for Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. J. Kaufman-Janette, M. S. Kaminer, M. H. Gold, B. E. Katz, J. Schlessinger, and V. Leroy Young are investigators and consultants for Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. J. Clark and K. Peddy are also investigators for Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. M. Davis, D. Hurley, G. Liu, M. P. McLane, and S. Vijayan are employees of Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. L. S. Bass is an advisory board participant and consultant for Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. S. G. Fabi and M. P. Goldman received research grants from Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. V Leroy Young has also received registration and travel expenses from Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Contributor Information

John H. Joseph, Email: drjohnjoseph@sbcglobal.net.

Michael S. Kaminer, Email: mkaminer@skincarephysicians.net.

James Clark, Email: clarkmd@cvillemedresearch.com.

Sabrina G. Fabi, Email: sfabi@clderm.com.

Michael H. Gold, Email: drgold@goldskincare.com.

Mitchel P. Goldman, Email: mgoldman@clderm.com.

Bruce E. Katz, Email: brukatz@gmail.com.

Kappa Peddy, Email: kappapeddy@icloud.com.

Joel Schlessinger, Email: skindoc@lovelyskin.com.

V. Leroy Young, Email: leroy.young@mercy.net.

Matthew Davis, Email: Davis.Matthew2@endo.com.

David Hurley, Email: Hurley.David@endo.com.

Genzhou Liu, Email: Liu.Genzhou@endo.com.

Michael P. McLane, Email: McLane.Michael@endo.com.

References

- 1.Friedmann DP, Vick GL, Mishra V. Cellulite: a review with a focus on subcision. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2017;10:17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossi AB, Vergnanini AL. Cellulite: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2000;14:251–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avram MM. Cellulite: a review of its physiology and treatment. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2005;6:181–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nürnberger F, Müller G. So-called cellulite: an invented disease. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1978;4:221–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudolph C, Hladik C, Hamade H, Frank K, et al. Structural gender-dimorphism and the biomechanics of the gluteal subcutaneous tissue—implications for the pathophysiology of cellulite. Plast Reconstr Surg 2019;143:1077–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirrashed F, Sharp JC, Krause V, Morgan J, et al. Pilot study of dermal and subcutaneous fat structures by MRI in individuals who differ in gender, BMI, and cellulite grading. Skin Res Technol 2004;10:161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Querleux B, Cornillon C, Jolivet O, Bittoun J. Anatomy and physiology of subcutaneous adipose tissue by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy: relationships with sex and presence of cellulite. Skin Res Technol 2002;8:118–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hexsel D, Siega C, Schilling-Souza J, Stapenhorst A, et al. Assessment of psychological, psychiatric, and behavioral aspects of patients with cellulite: a pilot study. Surg Cosmet Dermatol 2012;4:131–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hexsel DM, Abreu M, Rodrigues TC, Soirefmann M, et al. Side-by-side comparison of areas with and without cellulite depressions using magnetic resonance imaging. Dermatol Surg 2009;35:1471–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hexsel D, Dal Forno T, Hexsel C, Schilling-Souza J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of cellulite depressed lesions successfully treated by subcision. Dermatol Surg 2016;42:693–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hexsel DM, Mazzuco R. Subcision: a treatment for cellulite. Int J Dermatol 2000;39:539–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amore R, Amuso D, Leonardi V, Sbarbati A, et al. Treatment of dimpling from cellulite. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2018;6:e1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaminer MS, Coleman WP, III, Weiss RA, Robinson DM, et al. Multicenter pivotal study of vacuum-assisted precise tissue release for the treatment of cellulite. Dermatol Surg 2015;41:336–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brauer JA, Christman MP, Bae YSC, Bernstein LJ, et al. Three-dimensional analysis of minimally invasive vacuum-assisted subcision treatment of cellulite. J Drugs Dermatol 2018;17:960–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaminer MS, Coleman WP, III, Weiss RA, Robinson DM, et al. A multicenter pivotal study to evaluate tissue stabilized-guided subcision using the Cellfina device for the treatment of cellulite with 3-year follow-up. Dermatol Surg 2017;43:1240–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaminer M. Multi-center Pivotal Study of the Safety & Effectiveness of a Tissue Stabilized-Guided Subcision Procedure for the Treatment of Cellulite―5-Year Update. Presented at American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Annual Meeting; October 11–14, 2018; Phoenix, AZ.

- 17.Xiaflex (collagenase clostridium histolyticum) for Injection, for Intralesional Use [package Insert]. Malvern, PA: Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadick NS, Goldman MP, Liu G, Shusterman NH, et al. Collagenase clostridium histolyticum for the treatment of edematous fibrosclerotic panniculopathy (cellulite): a randomized trial. Dermatol Surg 2019;45:1047–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Narins RS, Brandt F, Leyden J, Lorenc ZP, et al. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of Restylane versus Zyplast for the correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg 2003;29:588–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. 2009. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm193282.pdf. Accessed April 23, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hexsel DM, Siega C, Schilling-Souza J, Porto MD, et al. A bipolar radiofrequency, infrared, vacuum and mechanical massage device for treatment of cellulite: a pilot study. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2011;13:297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hexsel DM, Dal'Forno T, Hexsel CL. A validated photonumeric cellulite severity scale. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23:523–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De La Casa Almeida M, Suarez Serrano C, Jiménez Rejano JJ, Chillón Martinez R, et al. Intra- and inter-observer reliability of the application of the cellulite severity scale to a Spanish female population. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:694–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis DS, Boen M, Fabi SG. Cellulite: patient selection and combination treatments for optimal results—a review and our experience. Dermatol Surg 2019;45:1171–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peimer CA, Blazar P, Coleman S, Kaplan FT, et al. Dupuytren contracture recurrence following treatment with collagenase clostridium histolyticum (CORDLESS [Collagenase Option for Reduction of Dupuytren Long-term Evaluation of Safety Study]): 5-year data. J Hand Surg Am 2015;40:1597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carson CC, III, Sadeghi-Nejad H, Tursi JP, Smith TM, et al. Analysis of the clinical safety of intralesional injection of collagenase Clostridium histolyticum (CCH) for adults with Peyronie's disease (PD). BJU Int 2015;116:815–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peimer CA, Wilbrand S, Gerber RA, Chapman D, et al. Safety and tolerability of collagenase Clostridium histolyticum and fasciectomy for Dupuytren's contracture. J Hand Surg Eur 2015;40:141–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]