Abstract

These are challenging times for physicians. Extensive changes in the practice environment have altered the nature of physicians’ interactions with patients and their role in the health care delivery system. Many physicians feel as if they are “cogs in the wheel” of austere corporations that care more about productivity and finances than compassion or quality. They often do not see how the strategy and plan of their organization align with the values of the profession. Despite their expertise, they frequently do not feel they have a voice or input in the operational plan of their work unit, department, or organization. At their core, the authors believe all of these factors represent leadership issues. Many models of leadership have been proposed, and there are a number of effective philosophies and approaches. Here, the authors propose a new integrative model of Wellness-Centered Leadership (WCL). WCL includes core skills and qualities from the foremost leadership philosophies along with evidence on the relationship between leadership and physician well-being and distills them into a single framework designed to cultivate leadership behaviors that promote engagement and professional fulfillment. The 3 elements of WCL are: care about people always, cultivate individual and team relationships, and inspire change. A summary of the mindset, behaviors, and outcomes of the elements of the WCL model is presented, and the application of the elements for physician leaders is discussed. The authors believe that learning and developing the skills that advance these elements should be the aspiration of all health care leaders and a foundational focus of leadership development programs. If cultivated, the authors believe that WCL will empower individual and team performance to address the current problems faced by health care organizations as well as the iterative innovation needed to address challenges that may arise in the decades to come.

These are challenging times for physicians. Numerous, complex factors have contributed to extensive changes in the practice environment that have altered the nature of physicians’ interactions with patients and their role in the health care delivery system. 1,2 Physicians are increasingly employed by large health care organizations, a fundamental shift from the solo or small-group practice model of the past. 3 The structure of these organizations is also more complex than in years past, often involving large integrated systems with a matrix structure.

This evolution has attenuated physicians’ sense of autonomy and control over their work. 4–6 While most physicians derive great meaning and purpose from their work, many also feel as if they are “cogs in the wheel” of austere corporations that care more about productivity and finances than compassion or quality. 1,2,7–9 Physician performance is now assessed by an array of metrics (e.g., measures of cost, patient satisfaction scores, how quickly they sign notes or answer electronic health record inbox messages) that can overshadow the appreciation and respect of patients and colleagues that has traditionally served as physicians’ main source of feedback. 1,2,10 Disturbingly, some organizations attempt to motivate change by relying on tactics that may shame physicians (e.g., posting a public hierarchical “leader” board of these metrics). Such tactics can leave physicians feeling disrespected and micromanaged by a bureaucracy that fails to recognize the nature of their work. 11

The problem is compounded by extensive regulatory oversight, administrative burden, 9,12,13 the implementation of suboptimal electronic health records used to enforce oversight mandates, 14,15 and other factors that can erode meaning and purpose in work. 16–18 Physicians have readily identified these and other problems in the clinical practice environment but often feel disempowered to improve the system. 9,19,20 Their suggestions often fall on deaf ears with operational leaders focusing on rigid standardization for predictable homogeneity rather than improving quality or service. 1,21–23 All of these factors contribute to high levels of burnout and a decline in professional fulfillment among physicians. 24–26

At their core, we believe all of these factors represent leadership issues. 27–32 Physician leaders who ignore these challenges perpetuate misalignment between organizational strategy and physicians’ deeply held professional values, even though these professional values are ones that these leaders themselves typically hold. 1,6,9,11 Despite their expertise, physicians often do not feel that they have a voice or input in the operational plan of their work unit, department, or organization. 9,23 They are not often afforded the flexibility or control commensurate with their expertise and professional status. 31 In many instances, physicians are also not being optimally developed or deployed and their expertise, which is needed to address and improve the health care system, is not being appropriately harnessed. 1,11,33 Fundamentally, many leaders are mismanaging some of the most talented professionals in their health care delivery systems and organizations. 31

How Did Health Care Organizations Get Here?

In many respects, this void of physician leadership in medicine should not be surprising. First, developing physician leaders was a low priority in the era of solo and small-group practice or in large academic practice models of the past where physicians were managed with benign neglect that allowed unfettered independence. 34,35 Over the last 1–2 decades, although some health care organizations have invested in the development of senior physician leaders, 36–39 they rarely invest in developing the leaders that have the greatest impact on physicians’ well-being and professional fulfillment—that is, the leaders most proximal to care delivery (or those closest to the physicians caring for patients). 27 These first-line leaders are typically appointed based on their clinical excellence, expertise, seniority, research and academic achievements, or willingness to lead. 34 They often have not been prepared for this role and may have had limited past leadership experience.

Second, physicians’ natural tendencies and professional training can be an Achilles’ heel to being an effective leader. 34,40 For example, physicians tend to be attentive to detail, and, in leadership positions, this tendency can lead some to be micromanagers. 41,42 Their reliance on evidence for clinical decision making can often lead them down “evidence rabbit holes” when considering leadership decisions and can cause them to be overreliant on data, as opposed to consensus building, in leadership decision making. Additionally, because of their problem-solving role in clinical contexts, physician leaders often assume it is their responsibility to come up with the answers and to drive change through authority rather than influence. This can lead to the mindset that the leader is a great individual surrounded by a supporting cast. 40 When combined with a lack of leadership development and an absence of feedback on their leadership behaviors, it is no wonder that first-line physician leaders often struggle in this role.

Finally, leading physicians can be quite challenging. Leaders of physicians must help oversee and direct a group of experts who are trained to think critically, be problem solvers, have opinions, and demand evidence for decision making. Effective leadership of such a group requires skills that are counter to many of the natural tendencies and training experiences of physicians.

Where Do Health Care Organizations Go From Here?

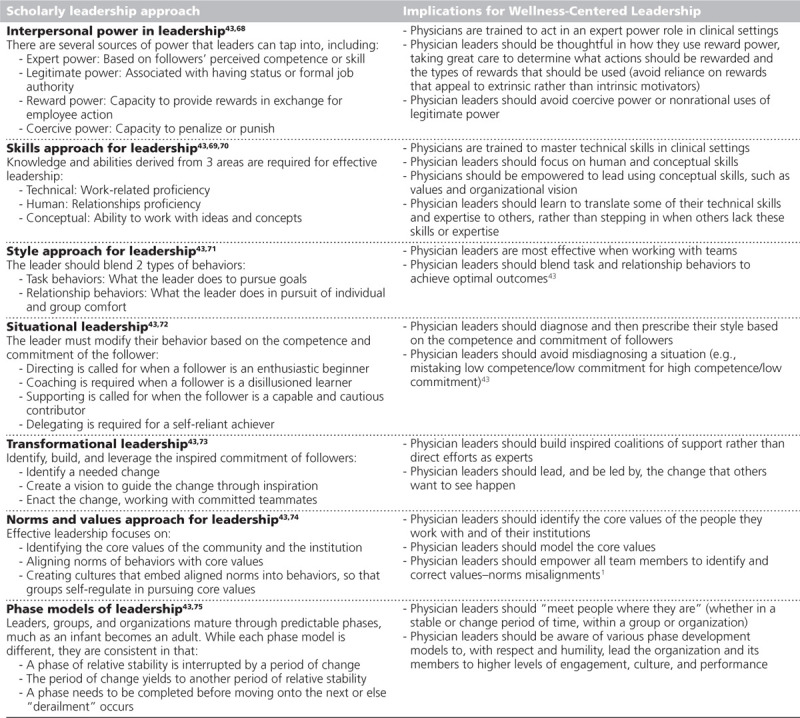

Many models of leadership have been proposed, and there is a reason why there is no single model of effective leadership or leadership development. 43 There are a number of effective philosophies and approaches. The major schools of leadership philosophy over the last 70 years are summarized in Table 1. We have attempted to harness the key components and contributions of each of these schools along with evidence on the relationship between leadership and physician well-being to construct a new integrative model of Wellness-Centered Leadership (WCL).

Table 1.

Major Scholarly Approaches to Leadership Over the Last 70 Years and Their Implications for the Wellness-Centered Leadership Model

Leadership requires a broad set of skills, and some leadership styles may work better in some situations than others. Thankfully, the skills that physician leaders must master to effectively promote the engagement and professional fulfillment of physicians and other highly trained professionals are a limited set that are not predicated on charisma or a certain personality. Some of the key skills and qualities of WCL include inclusion, keeping people informed, humble inquiry, developing individuals, empowering individuals and teams, and focusing on intrinsic motivators rather than extrinsic rewards or punishment. 27 These skills can be learned, strengthened, and developed. The most essential element is empowering, relational leadership that produces outcomes consistent with the altruistic values of the profession. This involves identifying and enabling implementation of improvements that advance the ability of physicians to provide high-quality compassionate care to patients in an equitable and just practice environment.

Foundations of WCL

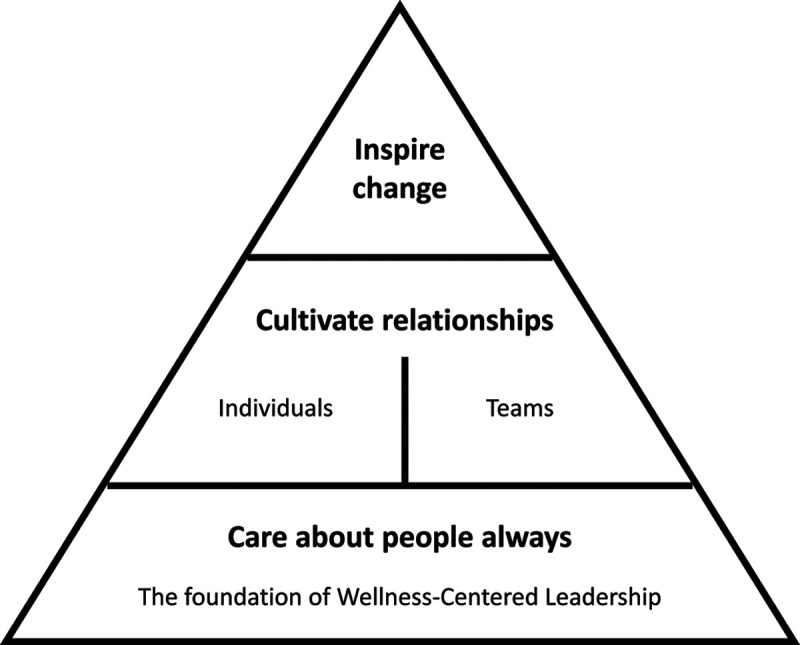

Our model for WCL is inclusive of the core skills and qualities ascertained from the foremost leadership philosophies (see Table 1) along with evidence on the relationship between leadership and physician well-being and distills them into a single framework designed to cultivate leadership behaviors that promote engagement and professional fulfillment. The 3 elements of WCL are: care about people always, cultivate individual and team relationships, and inspire change (Figure 1). A more detailed summary of the 3 elements of the WCL model is presented in Table 2. Each element is broken down into mindset, behaviors, and outcomes. Mindset focuses on the attitude and intention of the leader, and as Carol Dweck noted, “how they perceive their abilities.” 44 Leaders who show up with curiosity and humility, open to opinions and opportunities, are far more effective at promoting wellness than “experts who think they know best.” 44,45 Behaviors focus on the leadership actions that bring about desired outcomes. Outcomes are interim measures of effectiveness that, when taken together, can lead to cultures of wellness for individuals, teams, and organizations. Specific examples of what the 3 elements of the WCL model may look like in practice are presented in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Diagram showing the 3 elements of the Wellness-Centered Leadership model.

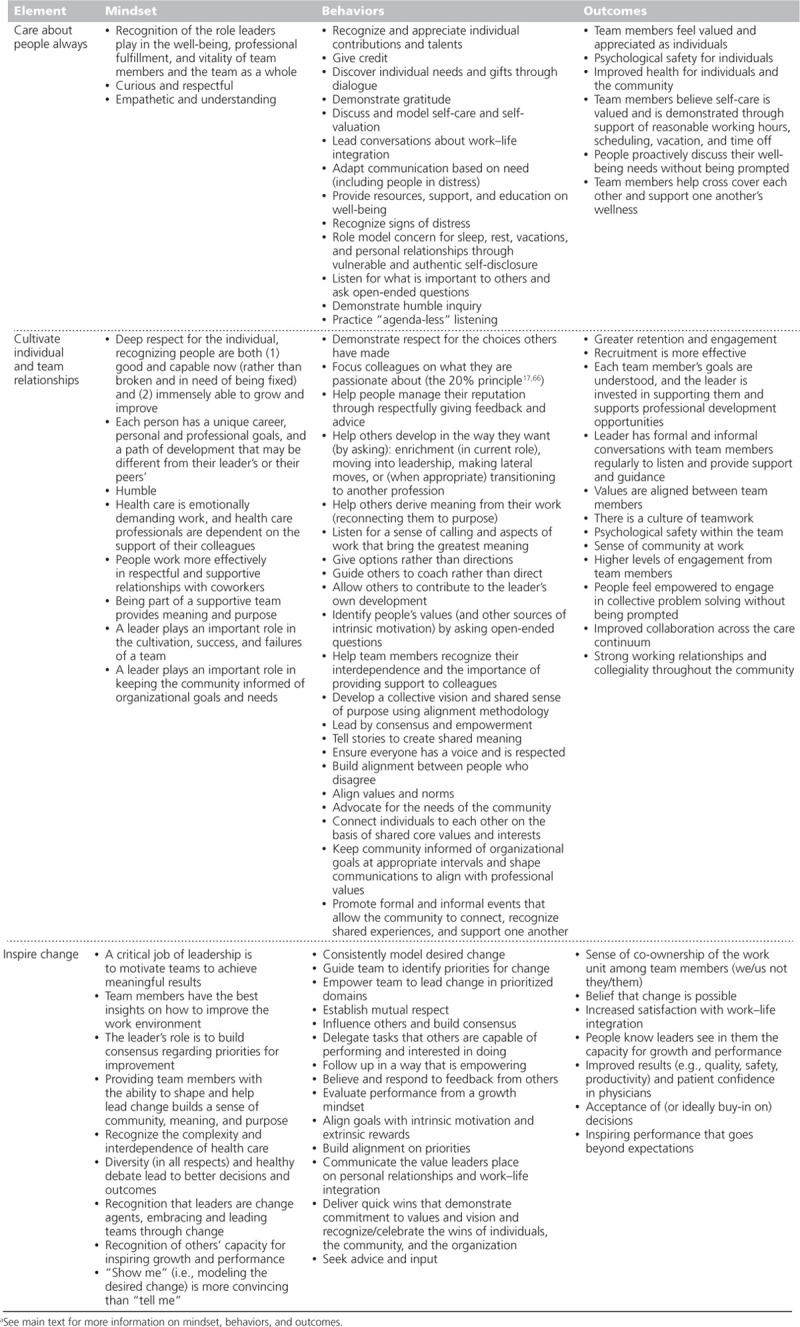

Table 2.

Summary of the 3 Wellness-Centered Leadership Elementsa

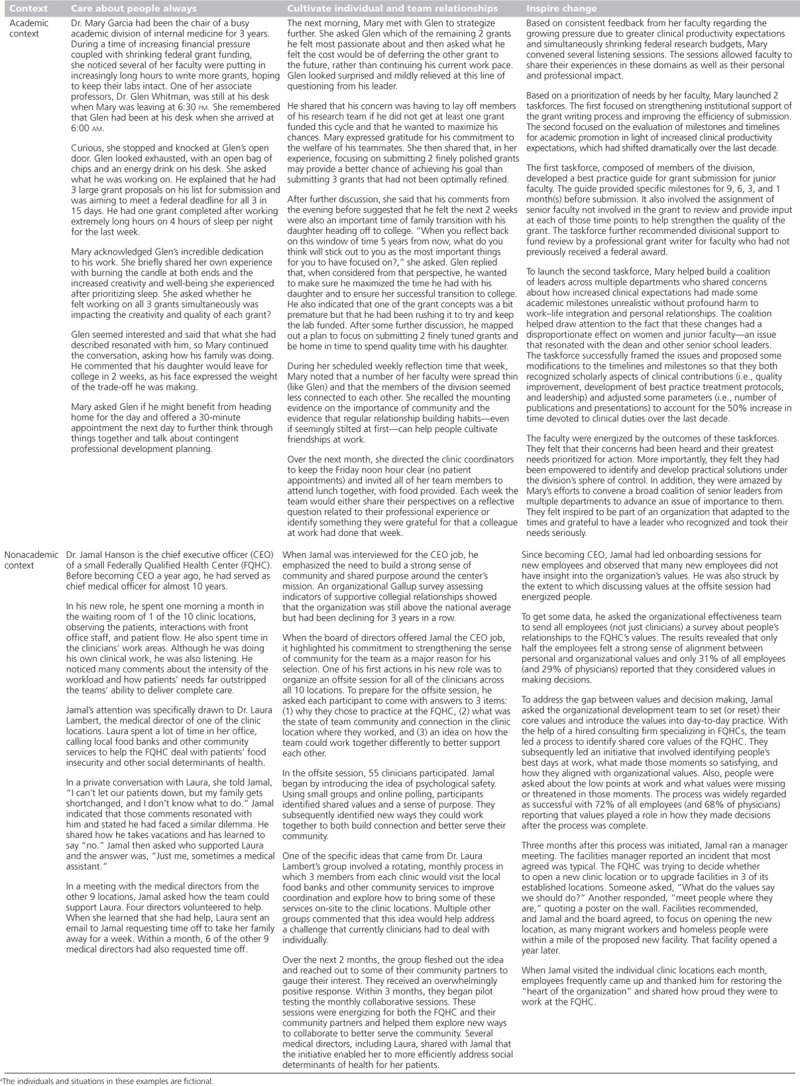

Table 3.

Examples of What the 3 Wellness-Centered Leadership Elements May Look Like in Practicea

Element 1: Care about people always

At its foundation, and underpinning the success of the subsequent elements, WCL requires that leaders care about people always. This starts with leaders recognizing the pivotal role their behaviors play in the professional fulfillment, vitality, and wellness of their team members. 27,46 Caring about people always is the only reliable foundation on which to build relational leadership skills that inspire individual and team performance.

Leaders must emphasize integrity, servanthood, and seeking the best for people. Caring leaders demonstrate respect, empathy, and curiosity, and they continually seek to understand and validate the complex needs and contributions of individuals and teams. 30,39,47–51

Care about people always begins with caring for self. Leaders who wish to cultivate well-being, professional fulfillment, and vitality in their team and team members must also recognize the importance of nurturing these qualities for themselves. This begins with the fundamental premise that caring for self is integral to performance. 52 Indeed, recent research from Stanford University demonstrates that a leader’s personal level of burnout, professional fulfillment, and self-valuation predicts their independently rated leadership behavior scores, as assessed by the members of their team. 53 In turn, those leadership behavior scores have been shown to be one of the largest drivers of professional fulfillment among members of the work unit. 27 Thus, leaders’ personal wellness impacts their performance as leaders.

Caring for self must encompass attention to exercise, nutrition, health, and rest (e.g., breaks, time off, vacation). Mounting evidence also demonstrates the critical role sleep plays in leadership effectiveness. 54–56 Studies indicate that sleep deprivation in leaders damages their relationships with their subordinates and also increases the likelihood that subordinates will engage in unethical practices. 54 Leaders’ devaluation of sleep (e.g., bragging about how little they sleep) also appears to adversely impact their team members’ sleep behaviors. 56

It should be emphasized that caring for self is foundationally necessary but, on its own, grossly insufficient to achieve the first element of WCL. Leaders must also nurture the leadership behaviors that demonstrate they are committed to the professional development and well-being of individuals and have empathy for team members. Empathy for others promotes leadership effectiveness more than cognitive task proficiency—the historical yardstick for entry into medical school. 57 Empathetic concern and capacity for perspective taking drive relational leadership behaviors that inspire change and achievements that go beyond expectations. 58

Element 2: Cultivate individual and team relationships

WCL also requires that leaders engage in behaviors that cultivate individual and team relationships (i.e., that they nurture relationships with the individuals they lead as well as the interrelationships of the team as a whole). Health care is emotionally demanding work, and health care professionals are dependent on the support of their leaders and colleagues. Physicians work most effectively when they are part of a team that supports respectful relationships and provides meaning and purpose.

WCL demands a deep respect for individuals, recognizing that people are both good and capable now (rather than broken and in need of being fixed) and immensely able to grow and improve. Leaders must embrace that the primary function of a leader is to unleash the talent of those they lead and harness that talent to accomplish the mission of the group. 46 To achieve this, they must recognize people as individuals, gain insight into their values, and nurture professional development. 27,30

WCL requires that leaders treat each team member as an individual with unique needs, interests, challenges, and ambitions. 30 Leaders should view their charge as investing in and developing that person, nurturing their talents, and directing that talent and passion to serve the needs of the team. Doing so requires an understanding of what motivates each individual, the aspects of their work that bring them the greatest meaning, and their professional ambitions.

Physician leaders have at least one distinct advantage: physicians typically derive tremendous meaning from their work. 17,59–61 They approach their work with a sense of calling, which leads to high levels of dedication, commitment, and discretionary effort. 59,61 This allows leaders the opportunity to harness the inspirational power of why people became physicians in the first place. Indeed, studies indicate that physicians who approach their work with a sense of calling may be at less risk for professional burnout. 62

Evidence also indicates that individuals who spend at least 20% of their professional effort dedicated to the activity they find the most meaningful are at markedly lower risk for burnout. 17 Thus, a critical leadership opportunity is helping harness each individual’s passion and talents in ways that serve the needs of the team. There are specific organizational needs that must be met and tasks that must be completed. Leaders do, however, have the ability to deploy their team, identify new opportunities, help people develop new skills, and look for ways to optimize fit over time. Even small increases in the amount of time an individual dedicates to activities they find meaningful build alignment and strengthen intrinsic motivation. 59 Such efforts by leaders to optimize career fit also typically make individuals more willing to take on other tasks for the good of the team since their personal needs have been overtly recognized and respected.

WCL, however, goes far beyond individual development. Leaders must help develop and articulate the vision and mission for the team and guide the process of achieving it. 39,63 Even if the goals have been prescribed from above, it is important for leaders to seek input from their team in developing the plan for how to accomplish those goals. 31 Further, leaders play an important role in keeping the team informed of organizational goals and needs. This requires judgment to discern what information should be transparently shared with the team and what to shield them from or share only intermittently to avoid undermining their sense of purpose and shared values (e.g., avoiding monthly updates on productivity [e.g., number of visits, relative value units, payor mix] relative to the financial plan).

At the team level, leadership that cultivates well-being and professional fulfillment requires attending to the interrelationships among team members to create a shared sense of alignment toward the team’s mission and goals. 23,46,64 This includes both relationships between physicians as well as between physicians and other members of the interdisciplinary team. Teams develop their own subcultures. The current culture of many health care teams is characterized by cynicism, commitment to the work but not the organization, and low levels of trust in the organization. 1,2,7–9 The role of the leader is to diagnose the relational health of the team as well as the degree of alignment of the team toward a common mission and goals. Once relational health and degree of alignment are determined, specific tactics can be deployed to cultivate relationships, teamwork, alignment, and a shared sense of purpose. 65

At the system level, organizations committed to WCL must integrate attention to productivity with concern for people, resulting in efficiency-focused cultures that encourage strong working relationships and make it easy for physicians to provide the care their patients need. Such organizations believe part of their purpose is to provide meaningful work and professional development for their people. 31 The organization’s core values must align with the values of health care professionals, and their actions and behaviors must be congruent with those values. 46 Consistent with these principles, senior leaders must consistently communicate—with their words and actions—the message that the primary purpose of leadership is to develop the talent of their team members, build alignment, and empower the team so the organization can achieve its mission. 31 Although many organizations claim (with words) to have this view, their methods for evaluating leader performance often reveal (with actions) that they actually view leaders’ primary responsibility as enforcing top-down edicts, increasing standardization, and ensuring physicians deliver on productivity targets.

Element 3: Inspire change

The final component of WCL requires that leaders inspire change by encouraging teams to think beyond the status quo, empowering them to drive change, and helping them achieve meaningful results. Teams and individual team members should be provided the greatest possible flexibility and control over how they accomplish group and organizational aims. 1,33,66,67 This does not mean that these individuals have unfettered autonomy to deliver care however they want, practice in a manner that is inconsistent with the needs of patients or other team members, or fail to do their share of the collective work required of the group. Best practices must be followed, adequate access to care provided, equity ensured, and collegiality valued. However, the concept that all variability is waste, that standardization should be pursued simply to facilitate easy scheduling and staffing, or that most aspects of clinical care can be homogeneous and reduced to algorithmic recipes must be rejected. 9 These beliefs are antithetical to the expertise and professionalism of physicians, the complexity of modern medicine, the coexistent health conditions and unique preferences of individual patients, and the different personal life demands and responsibilities of individual physicians. 1,31

Organizations that cultivate WCL primarily rely on intrinsic motivators to drive results rather than primarily focusing on aligning incentives using a carrot-and-stick model (e.g., rewarding physicians for relative value unit generation and high patient throughput). 2,7,9,17,59–61 Intrinsic motivators include meaning, purpose, values, voice, input, control, and professional development. Extrinsic motivators include financial incentives, titles, and awards. Which approach an organization relies on can be determined by their compensation plan, incentives, communication, and what they recognize people for. Unfortunately, many health care organizations have overrelied on extrinsic rewards to increase productivity and enhance performance in spite of compelling evidence that this approach has limited effectiveness. 31 Over time, relying on extrinsic motivators lowers motivation and can transform self-motivated individuals who pursue their work with a sense of calling into disengaged workers who view their work through a transactional lens (e.g., they work to earn a paycheck). 31

The format and structure of team discussions to identify opportunities for improvement are also critical. Leaders should begin by identifying a list of possible areas in which improvement may be pursued and allowing the group to determine which of those areas are the most important place to start. Once the team has identified an area for improvement, the primary focus should be on improvement in that area at the work unit level. 33,66,67 Although it is often helpful to give the group a few moments to identify some of the factors that may contribute to this challenge that are outside of the work unit’s control, dwelling on such factors often leads to a sense of victimization. Focusing on work unit opportunities to drive improvement in a specified time frame helps team members feel empowered and leads to identification of actionable improvement targets. 33,66 Focusing on factors that are under local control that can be altered to improve the work life of team members within the next 3 to 6 months can result in meaningful progress that builds momentum that can then help to tackle more challenging and longer-term objectives.

The Call to Action

Many of the skills and qualities essential for WCL have not traditionally been part of the selection criteria for physician leaders. In addition, evaluation of performance and opportunities for building skills and expertise in these domains has not been the focus of most leadership development programs for health care leaders. To advance WCL, organizations will need to consider the mindset and skills pertinent to WCL as part of the leader selection process. They will also need to consider how they will assess leader performance in these domains and determine which of the elements of WCL may need further development. Training programs and opportunities to build skills in the elements of WCL need to be incorporated into leadership development programs, and studies evaluating the most effective ways to develop these skills are needed. Further research evaluating the impact of WCL on individual, team, and organizational performance would be enlightening.

Conclusions

Here, we propose the new integrative model of WCL. Leadership is a complex set of skills that are required to motivate individuals and teams to help an organization accomplish its mission. We believe the elements of WCL have broad relevance for leaders in many fields but have applied the model here to physician leaders with the aim of addressing the epidemic of occupational distress in physicians. 24,25 We believe that the elements of WCL must be central to how organizations select, develop, and assess health care leaders. Only by attending to these elements can the health care delivery system achieve optimal outcomes for patients, communities, physicians, and health care workers. Thus, learning and developing the skills that advance these elements should be the aspiration of all health care leaders and a foundational focus of leadership development programs. If cultivated, we believe that WCL will empower individual and team performance to address the current problems faced by health care organizations as well as the iterative innovation needed to address challenges that may arise in the decades to come.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: Funding provided by the California Medical Association and Stanford WellMD Center.

Other disclosures: T. Shanafelt is co-inventor of the Participatory Management Leadership Index and the Well-being Index instruments. Mayo Clinic holds the copyright for these instruments and has licensed them for use outside of Mayo Clinic. T. Shanafelt receives a portion of royalties from Mayo Clinic. T. Shanafelt also receives royalties from the book Mayo Clinic Strategies to Reduce Burnout: 12 Actions to Create the Ideal Workplace. A. Rodriguez is also employed at Heritage Provider Network and has performed contracted work for CultureSync and the California Medical Association’s CMA Wellness Services. D. Logan is cofounder of the management consulting firm CultureSync. Although he is no longer involved in day-to-day business of the firm, both he and his wife have an ownership stake in the company.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

References

- 1.Shanafelt TD, Schein E, Minor LB, Trockel M, Schein P, Kirch D. Healing the professional culture of medicine. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:1556–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwenk TL. What does it mean to be a physician? JAMA. 2020;323:1037–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kane CK. Updated Data on Physician Practice Arrangements: For the First Time, Fewer Physicians Are Owners Than Employees. 2019. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-07/prp-fewer-owners-benchmark-survey-2018.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, et al. Managed care, time pressure, and physician job satisfaction: Results from the physician worklife study. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:441–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linzer M, Manwell LB, Williams ES, et al. ; MEMO (Minimizing Error, Maximizing Outcome) Investigators. Working conditions in primary care: Physician reactions and care quality. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoddard JJ, Hargraves JL, Reed M, Vratil A. Managed care, professional autonomy, and income: Effects on physician career satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:675–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nurok M, Gewertz B. Relative value units and the measurement of physician performance. JAMA. 2019;332:1139–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Souba WW. Academic medicine and the search for meaning and purpose. Acad Med. 2002;77:139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agarwal SD, Pabo E, Rozenblum R, Sherritt KM. Professional dissonance and burnout in primary care: A qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khullar D, Wolfson D, Casalino LP. Professionalism, performance, and the future of physician incentives. JAMA. 2018;320:2419–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunderman RB. Poor care is the root of physician disengagement. NEJM Catalyst. http://contentmanager.med.uvm.edu/docs/physician_burnout_the_root_of_the_problem_and_the_path_to_solutions/faculty-affairs-documents/physician_burnout_the_root_of_the_problem_and_the_path_to_solutions.pdf?sfvrsn=2. Published January 10, 2017. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 12.Erickson SM, Rockwern B, Koltov M, McLean RM; Medical Practice and Quality Committee of the American College of Physicians. Putting patients first by reducing administrative tasks in health care: A position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:659–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:836–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: A time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melnick ER, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky CA, et al. The association between perceived electronic health record usability and professional burnout among US physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:476–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shanafelt TD. Enhancing meaning in work: A prescription for preventing physician burnout and promoting patient-centered care. JAMA. 2009;302:1338–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sloan JA, et al. Career fit and burnout among academic faculty. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:990–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konrad TR, Williams ES, Linzer M, et al. Measuring physician job satisfaction in a changing workplace and a challenging environment. SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. Society of General Internal Medicine. Med Care. 1999;37:1174–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMurray JE, Williams E, Schwartz MD, et al. ; SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. Physician job satisfaction: Developing a model using qualitative data. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:711–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linzer M, Poplau S, Babbott S, et al. Worklife and wellness in academic general internal medicine: Results from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:1004–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keller EJ, Giafaglione B, Chrisman HB, Collins JD, Vogelzang RL. The growing pains of physician-administration relationships in an academic medical center and the effects on physician engagement. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0212014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz RW, Pogge C. Physician leadership: Essential skills in a changing environment. Am J Surg. 2000;180:187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnetz BB. Physicians’ view of their work environment and organisation. Psychother Psychosom. 1997;66:155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1377–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:1681–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: Contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shanafelt TD, Gorringe G, Menaker R, et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:432–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seppala E. Good Bosses Create More Wellness Than Wellness Plans Do. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/04/good-bosses-create-more-wellness-than-wellness-plans-do. Published April 8, 2016. Accessed December 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westerlund H, Nyberg A, Bernin P, et al. Managerial leadership is associated with employee stress, health, and sickness absence independently of the demand-control-support model. Work. 2010;37:71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Demmy TL, Kivlahan C, Stone TT, Teague L, Sapienza P. Physicians’ perceptions of institutional and leadership factors influencing their job satisfaction at one academic medical center. Acad Med. 2002;77:1235–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swensen SJ, Shanafelt TD. Mayo Clinic Strategies to Reduce Burnout: 12 Actions to Create the Ideal Workplace. 2020.New York, NY: Oxford University Press; [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dyrbye LN, Major-Elechi B, Hays JT, Fraser CH, Buskirk SJ, West CP. Relationship between organizational leadership and health care employee burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:698–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swensen S, Kabcenell A, Shanafelt T. Physician-organization collaboration reduces physician burnout and promotes engagement: The Mayo Clinic experience. J Healthc Manag. 2016;61:105–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stoller JK. Developing physician-leaders: A call to action. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:876–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee TH. Turning doctors into leaders. Harv Bus Rev. 2010;88:50–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lucas R, Goldman EF, Scott AR, Dandar V. Leadership development programs at academic health centers: Results of a national survey. Acad Med. 2018;93:229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palmer M, Hoffmann-Longtin K, Walvoord E, Bogdewic SP, Dankoski ME. A competency-based approach to recruiting, developing, and giving feedback to department chairs. Acad Med. 2015;90:425–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Straus SE, Soobiah C, Levinson W. The impact of leadership training programs on physicians in academic medical centers: A systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88:710–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lobas JG. Leadership in academic medicine: Capabilities and conditions for organizational success. Am J Med. 2006;119:617–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stoller JK. Developing physician leaders: A perspective on rationale, current experience, and needs. Chest. 2018;154:16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gabbard GO. The role of compulsiveness in the normal physician. JAMA. 1985;254:2926–2929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lemaire JB, Wallace JE. How physicians identify with predetermined personalities and links to perceived performance and wellness outcomes: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Northouse PJ. Leadership: Theory and Practice. 2016.7th ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications; [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dweck CS. Growth mindset, revisited. Educ Week. 2015;35:20–24. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dweck CS. Growth. Br J Educ Psychol. 2015;85:242–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Souba WW. The new leader: New demands in a changing, turbulent environment. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waldron AL, Ebbeck V. The relationship of mindfulness and self-compassion to desired wildland fire leadership. Int J Wildland Fire. 2015;24:201–211. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heffernan M, Quinn Griffin MT, McNulty Sister Rita, Fitzpatrick JJ. Self-compassion and emotional intelligence in nurses. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16:366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singer T, Klimecki OM. Empathy and compassion. Curr Biol. 2014;24:R875–R878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coskun O, Ulutas I, Budakoglu II, Ugurlu M, Ustu Y. Emotional intelligence and leadership traits among family physicians. Postgrad Med. 2018;130:644–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gregory PJ, Robbins B, Schwaitzberg SD, Harmon L. Leadership development in a professional medical society using 360-degree survey feedback to assess emotional intelligence. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:3565–3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trockel MT, Hamidi MS, Menon NK, et al. Self-valuation: Attending to the most important instrument in the practice of medicine. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:2022–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shanafelt TD, Makowski MS, Wang H, et al. Association of burnout, professional fulfillment, and self-care practices of physician leaders with their independently rated leadership effectiveness. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e207961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guarana CL, Barnes CM. Lack of sleep and the development of leader-follower relationships over time. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2017;141:57–73. [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Dam N, van der Helm E. There’s a Proven Link Between Effective Leadership and Getting Enough Sleep. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/02/theres-a-proven-link-between-effective-leadership-and-getting-enough-sleep. Published February 16, 2016. Accessed December 10, 2020.

- 56.Barnes C. Sleep well lead better. Harv Bus Rev. 2018;September-October:140–143. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kellett JB, Humphrey RH, Sleeth RG. Empathy and complex task performance: Two routes to leadership. Leadership Q. 2002;13:523–544. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skinner C, Spurgeon P. Valuing empathy and emotional intelligence in health leadership: A study of empathy, leadership behaviour and outcome effectiveness. Health Serv Manage Res. 2005;18:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tak HJ, Curlin FA, Yoon JD. Association of intrinsic motivating factors and markers of physician well-being: A national physician survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:739–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horowitz CR, Suchman AL, Branch WT, Jr, Frankel RM. What do doctors find meaningful about their work? Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:772–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Serwint JR, Stewart MT. Cultivating the joy of medicine: A focus on intrinsic factors and the meaning of our work. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2019;49:100665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Souba WW. New ways of understanding and accomplishing leadership in academic medicine. J Surg Res. 2004;117:177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosenthal DI, Verghese A. Meaning and the nature of physicians’ work. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1813–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Logan D, King J, Fischer-Wright H. Tribal Leadership: Leveraging Natural Groups to Build a Thriving Organization. 2008.New York, NY: Harper Business; [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:129–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, Sinsky TA, Margolius D, Bodenheimer T. In search of joy in practice: A report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:272–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References cited in Table 1 only

- 68.Sturm RE, Antonakis J. Interpersonal power: A review, critique, and research agenda. J Manage. 2015;41:136–163. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peterson TO, Van Fleet DD. The ongoing legacy of R.L. Katz: An updated typology of management skills. Manage Decis. 2004;42:1297–1308. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hackworth J, Steel S, Cooksey E, DePalma M, Kahn JA. Faculty members’ self-awareness, leadership confidence, and leadership skills improve after an evidence-based leadership training program. J Pediatr. 2018;199:4–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blake RR, McKee RK. The leadership of corporate change. J Leadership Organ Stud. 1993;1:71–89. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Blank W. A test of the situation of leadership theory. Personnel Psychol. 1990;43:579–597. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bennis WG. The Essential Bennis. 2009.San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; [Google Scholar]

- 74.Graham JR, Harvey CR, Popdak J, Rajgopal S. Corporate Culture: Evidence From the Field. NBER Working Paper 23255. 2017. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; https://www.nber.org/papers/w23255. Accessed December 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Greiner LE. Evolution and revolution as organizations grow. 1972. Harv Bus Rev. 1998;76:55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]