Abstract

Background

Acquired hemophilia A is a rare bleeding disorder caused by autoantibodies to coagulation factor VIII (FVIII). In most cases, bleeding episodes are spontaneous and severe at presentation. The optimal hemostatic therapy is controversial.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy of hemostatic therapies for acute bleeds in people with acquired hemophilia A; and to compare different forms of therapy for these bleeds.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2014, Issue 4) and MEDLINE (Ovid) (1948 to 30 April 2014). We searched the conference proceedings of the: American Society of Hematology; European Hematology Association; International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH); and the European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders (EAHAD) (from 2000 to 30 April 2014). In addition to this we searched clinical trials registers.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials and quasi‐randomised trials of hemostatic therapies for people with acquired hemophilia A, with no restrictions on gender, age or ethnicity.

Data collection and analysis

No trials matching the selection criteria were eligible for inclusion.

Main results

No trials matching the selection criteria were eligible for inclusion.

Authors' conclusions

No randomised clinical trials of hemostatic therapies for acquired hemophilia A were found. Thus, we are not able to draw any conclusions or make any recommendations on the optimal hemostatic therapies for acquired hemophilia A based on the highest quality of evidence. GIven that carrying out randomized controlled trials in this field is a complex task, the authors suggest that, while planning randomised controlled trials in which patients can be enrolled, clinicians treating the disease continue to base their choices on alternative, lower quality sources of evidence, which hopefully, in the future, will also be appraised and incorporated in a Cochrane Review.

Plain language summary

Treatments for acute bleeds in people with acquired hemophilia A

Acquired hemophilia A is a rare but severe bleeding disorder caused by the autoantibody directed against factor VIII (FVIII, a blood clotting protein) in patients with no previous history of a bleeding disorder. This bleeding disorder occurs more frequently in the elderly and may be associated with several other conditions, such as solid tumours, autoimmune diseases, or with drugs; it is also sometimes associated with pregnancy. However, in about half of the cases the causes are unknown. Bleeding occurs in the skin; mucous membranes; and muscles; with joint bleeds being unusual. Therapies for acquired hemophilia A include treatments to stop acute bleeds and to destroy the FVIII autoantibodies. Acute bleeds can be treated with recombinant activated FVII or activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC). If these are unavailable, FVIII concentrates or 1‐desamino‐8‐D‐arginine‐vasopressin (DDAVP) fresh frozen plasma can be attempted; however, these last two options are not usually effective, and it is not known if one of these products is better than the other.

We conducted a review of any treatment used in people with acquired hemophilia A during episodes of acute bleeding. After searching for all relevant trials, no randomised controlled trials could be identified, and no definitive conclusion on the best available treatment could be drawn.

Prospective randomised controlled trials are needed to evaluate the precise role of different drugs for acute bleeds in acquired hemophilia A, but the rarity of the condition is hindering their planning and execution. While waiting for better evidence, patients and doctors need to base treatment decisions on the largest and better conducted observational studies, which are referenced in the background of our review.

Background

Description of the condition

Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is a rare, but severe, hemorrhagic disorder. It is characterised by either a deficiency in the function of the coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) or the targeting of specific epitopes (that cause neutralization or accelerated clearance of FVIII from the plasma) by autoantibodies, or a combination of both (Franchini 2008). This condition, which affects both sexes (Buczma 2007), occurs in the general population with a reported incidence of one to four cases per million per year, increasing with age (Collins 2007a; Delgado 2003; Franchini 2008).

The well‐recognised risk factors for AHA are autoimmune disorders (systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis), solid tumors, lymphoproliferative diseases, and pregnancy (typically appearing in the postpartum period); however, in approximately 50% of patients, AHA occurs apparently in the absence of other concomitant disease, i.e. FVIII autoantibodies are of an idiopathic origin (Baudo 2004a; Baudo 2007; Collins 2007a; Delgado 2003; Green 1981; Franchini 2008a; Meiklejohn 2001).

The diagnosis of AHA is typically based on:

a negative personal or family history of bleeding events or abnormal coagulation assays until the present episode;

the initial detection of an isolated prolongation of activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), which cannot be corrected by performing mixing tests without and with incubation (Verbruggen 1995); and

subsequent identification of a reduced FVIII:C level with evidence of FVIII inhibitor activity (detected and measured by the Bethesda assay or its Nijmegen modification) (Baudo 2010; Coppola 2009; Delgado 2003).

Hemorrhages in AHA patients usually occur suddenly and spontaneously, although approximately 25% of cases occur after trauma or invasive procedures (Baudo 2003). While bleeding at presentation is usually severe or life‐threatening, requiring hemostatic treatment and transfusion; it can also be mild, with approximately 25% of patients not requiring hemostatic treatment (Baudo 2004a; Franchini 2008). The mortality rate resulting from bleeding is high and reported to be between 7.9% and 22% (with the best estimates most likely lying toward the lowest end of the range). This is particularly true in elderly patients and during the first weeks after the onset of symptoms for a number of reasons. These include underlying associated diseases, diagnostic delays, inadequate treatment of acute bleeds, bleeding complications during invasive procedures for controlling hemorrhages, or adverse events of treatment (Baudo 2004a; Collins 2007a; Green 1981; Franchini 2008).

Observed clinical bleeding does not correlate with FVIII level or inhibitor titer and differs from hereditary hemophilia. Bleeding into the skin, muscles or soft tissues, and mucous membranes (e.g. epistaxis, gastrointestinal and urologic bleeds, retroperitoneal hematomas, postpartum bleeding) are more common, whereas bleeding into joints (hemarthrosis), a typical feature of congenital factor VIII deficiency, is unusual (Boggio 2001; Green 1981).

Description of the intervention

The therapeutic strategy for patients with AHA involves two aspects of treatment:

to control actual bleeding episodes (hemostatic agents); and

to eradicate FVIII autoantibodies (immunosuppressive treatment), the cause of coagulation abnormalities and of bleeding (Collins 2007a; Baudo 2010; Baudo 2012; Collins 2012; Coppola 2009; Franchini 2008; Huth‐Kühne 2009; Knoebl 2012; Tengborn 2012).

Available therapeutic interventions to control bleeding in patients with AHA are: bypassing agents (recombinant activated FVII (rFVIIa) (NovoSeven®) or activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC) (FEIBA®)); or FVIII replacement therapy with human or porcine FVIII concentrates; or induction of FVIII release using 1‐desamino‐8‐D‐arginine‐vasopressin (DDAVP) (Baudo 2010; Baudo 2012; Coppola 2009; Franchini 2008; Huth‐Kühne 2009; Knoebl 2012; Tengborn 2012).

Bypassing agents are the most commonly used first‐line treatment, particularly for severe bleeds in patients with high‐titer inhibitors. In several retrospective analyses, both aPCC and rFVIIa had been shown to be effective in these patients (Baudo 2012; Collins 2007b; Goudemand 2004; Franchini 2008; Hay 1997; Sallah 2004; Sumner 2007). Treatment with rFVIIa is administered as a bolus injection every two to six hours until hemostasis is achieved at average doses of 90 ug/kg (range 40 to 180 ug/kg) (Baudo 2012; Hay 1997; Huth‐Kühne 2009; Franchini 2008; Sallah 2004; Sumner 2007); whereas aPCC is administered as a bolus injection every 8 to 12 hours to a maximum of 200 IU/kg/day (with the standard dose ranging between 50 and 100 IU/kg) (Baudo 2012; Franchini 2008; Huth‐Kühne 2009; Sallah 2004).

Therapy with FVIII can only be advocated for the treatment of acute bleeding in patients with low‐titer inhibitors (i.e. less than five Bethesda units (BU)) and non‐severe bleeds (Baudo 2010; Huth‐Kühne 2009). Patients with low‐titer inhibitors can be treated with plasma‐derived or recombinant human FVIII concentrates, which should be administered at doses sufficient to overwhelm the inhibitor and thus achieve hemostatic levels of factor VIII. Human FVIII concentrates are usually administered as an intravenous bolus dose of 20 IU/kg for each BU of the inhibitor plus an additional 40 IU/kg, with monitoring of FVIII activity (FVIII:C) levels 10 minutes after the initial dose, and the subsequent administration of an additional bolus dose if the incremental recovery is not adequate (Collins 2007b; Franchini 2008; Huth‐Kühne 2009). Treatment with DDAVP releases FVIII/von Willebrand factor from the vascular endothelium; it is administered subcutaneously at a dose of 0.3 g/kg per day for three to five days (Franchini 2008; Mudad 1993).

Before the publication of the EACH2 results (Baudo 2012; Knoebl 2012; Tengborn 2012; Collins 2012) retrospective observational evidence was generated for rFVIIa (Baudo 2004b ; Hay 1997; Sumner 2007), for aPCC (Goudemand 2004; Sallah 2004), for FVIII (Collins 2007b) and for DDAVP (Chistolini 1987; de la Fuente 1995; Franchini 2011; Mudad 1993; Muhm 1990; Naarose‐Abidi 1988; Nilsson 1991; Vincente 1985). All these results were confirmed and superseded by the publication of the EACH2, the largest observational dataset reported to date, providing information on how the first bleeding episode of this rare but serious hemorrhagic condition was managed in over 300 cases in Europe. Among 307 patients treated with a first‐line hemostatic agent, 174 (56.7%) received rFVIIa, 63 (20.5%) aPCC, 56 (18.2%) FVIII, and 14 (4.6%) DDAVP. Bleeding was controlled in 269 of 338 (79.6%) AHA patients treated with a first‐line hemostatic agent. Bleeding control was significantly higher in patients treated with bypassing agents versus FVIII or DDAVP (93.3% versus 68.3%; P = 0.003). Bleeding control was similar between rFVIIa and aPCC (93.0%; P = 1). Arterial or venous thromboembolic events were reported in 3.6% of treated patients with a similar incidence between rFVIIa (2.9%) and aPCC (4.8%) but not with FVIII or DDAVP (Baudo 2012).

How the intervention might work

In pharmacological concentrations, rFVIIa can bind to the surface of activated platelets and directly activate factor X (FXa) in the absence of tissue factor (TF). The platelet surface FXa can then, in combination with activate factor V (FVa), lead to a thrombin burst in the absence of FVIII or FIX. As more thrombin is generated, positive feedback loops with FV, FVIII, and factor XI (FXI) occur. Cross‐linked fibrin is formed by thrombin activation of factor XIII (FXIII) to FXIIIa, producing a more stable, covalently linked clot, protected from degradation by the thrombin‐activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) (Abshire 2004; Ananyeva 2009).

The aPCC contains the proenzymes of the prothrombin complex factors, prothrombin, FVII, FIX and FX, but with only very small amounts of their activation products; with the exception of FVIIa, which is contained in aPCC in greater amounts. The aPCC controls bleeding by the induction and facilitation of thrombin generation (prothrombin is converted into thrombin), by FXa on a phospholipid surface mediated by calcium, but only if FV or its activated form, FVa, is present (Turecek 2004).

Treatment with DDAVP increases the plasma concentration of factor VIII and vWF through the endogenous release of the patient's own stores (Baudo 2010; Lethagen 1987). By increasing the concentration of the FVIII to values within the normal range, human FVIII concentrates or DDAVP administration normalises the hemorrhagic risk or stops the bleeding in responsive patients (Baudo 2010; Lethagen 1987).

Why it is important to do this review

Acute bleeding is a common clinical problem in people with AHA and the optimal therapy is controversial. At this stage, no systematic review or meta‐analysis of hemostatic therapies in people with AHA is available. We are aiming to better appraise and ideally to generate new evidence regarding the clinical benefit by systematically analysing and assessing the reliability and validity of the data and by considering only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs for our review.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy and safety of different hemostatic therapies for acute bleeds in people with AHA.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs.

Types of participants

We planned to include people with AHA, with no restrictions on gender, age or ethnicity.

Types of interventions

We considered the following interventions:

experimental intervention: first‐line hemostatic therapy (bypassing agent (recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa) or activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC)), replacement therapy (factor VIII (FVIII) or desmopressin (DDAVP));

comparator intervention: aPCC, fresh frozen plasma, a different experimental intervention (e.g. rFVII versus FEIBA, or FEIBA versus DDAVP).

We considered the following comparisons:

any hemostatic therapy, alone or in combination, versus no treatment

bypassing agent (rFVIIa or aPCC) versus replacement therapy (FVIII or DDAVP)

rFVIIa versus aPCC

FVIII versus DDAVP

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Bleeding control (the response to therapy judged by a clinician as bleeding resolved with date or bleeding not resolved)

Secondary outcomes

Number of participants with adverse effects (thromboses; allergic reactions)

Overall survival (defined as the time interval from randomisation or study entry to death from any cause or to last follow up)

Search methods for identification of studies

We did not adopt any language or publication restrictions.

Electronic searches

Search strategies have been adapted from those suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Lefebvre 2011). No language restriction were applied.

The following databases of medical literature were searched:

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2014, Issue 4) (Appendix 1);

MEDLINE (Ovid) (1948 to 30 April 2014) (Appendix 2);

Searching other resources

We handsearched citations from identified trials and relevant review articles as well as the following conference proceedings:

ASH (American Society of Hematology) 2009 to 30 April 2014;

European Hematology Association 2009 to 30 April 2014;

ISTH (International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis) 2009 to 30 April 2014;

EAHAD (European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders) 2009 to 30 April 2014;

WFH (World Federation of Haemophilia) 2009 to 30 April 2014.

We also searched clinical trial registers for ongoing trials (accessed 30 April 2014):

ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/);

The metaRegister of Controlled Trials (http://www.controlled-trials.com/mrct/)

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors independently checked the titles and abstracts identified from the searches. However, to date, the authors have not identified any eligible RCTs. For future updates, should any trials be included, the authors will adhere to the protocol outlined below.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (ZY, ZR) will independently extract data according to chapter 7 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions by using a standardized data extraction form containing the following items (Higgins 2011a).

General information: title; authors; journal or source; contact address; country of origin; language; publication type; year of publication; setting of trial.

Trial characteristics including: design; sample size; setting; location of trial; randomization method; concealment of allocation; blinding of patients and clinicians; withdrawals; median length of follow up; funding; conflict of interest statement.

Study interventions (basic information): disease(s) and stage(s) studied; category of treatment investigated; inclusion criteria; exclusion criteria; experimental intervention; control intervention; type of control; additional treatment; compliance; outcomes assessed; subgroup evaluated; confounders.

Baseline characteristics of patients: number of patients; age; ethnicity; gender; diagnosis; definition of diagnosis; extent of disease; organ involvement; additional diagnoses in group; stage; previous treatment; concurrent conditions.

Interventions: setting; dose and duration of hemostatic therapy; supportive treatment; additional treatment.

Outcomes: overall survival; bleeding control; adverse events.

We plan to combine data at the following time‐points: up to three months of follow up and over three months and up to two years of follow up.

If necessary, we will contact the principal trial investigators to clarify data and obtain any additional information needed.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (ZY and ZR) will independently assess the risk of bias of each included trial as per the recommendations in chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions using the following criteria (Higgins 2011b):

sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding;

incomplete outcome data;

selective outcome reporting;

other sources of bias.

We will assess each criterion as having either a low, unclear or high risk of bias. We will resolve any disagreements by discussion with a third author (LD).

Measures of treatment effect

We will use Review Manager 5.2 to conduct the analysis (RevMan 2013). For dichotomous (binary) outcomes, we will use the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the effect measure. For continuous outcome data, we will use the mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs, except where continuous data are reported using different units. In such cases we will calculate a standardised mean difference (SMD) and corresponding CIs. For survival data, we will estimate the treatment effects of individual studies as hazards ratios (HR) using the methods described by Parmar and Tierney (Parmar 1998; Tierney 2007).

Unit of analysis issues

We will include data from any eligible cross‐over trials in the review; we plan to analyse these using a method recommended by Elbourne (Elbourne 2002).

Dealing with missing data

If data are missing or unavailable, we will contact the corresponding author of trials to obtain further information. This may include missing outcomes (primary or secondary), missing participants due to dropout, and missing statistics such as standard deviations or correlation coefficients. If this is not possible and if we assume that these data are 'missing at random', we will perform an available case analysis (i.e. ignoring the missing data) and discuss the impact of missing data on our results. When we assume the missing outcome data are not 'missing at random', we will conduct an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis by imputing the missing data with replacement values, and treating these as if they were observed (e.g. last observation carried forward, imputing an assumed outcome such as assuming all were poor outcomes, imputing the mean, imputing based on predicted values from a regression analysis). We will perform a sensitivity analysis by including or excluding trials with significant dropouts to assess how sensitive results are to reasonable changes in the assumptions that are made (Higgins 2011c).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We will assess heterogeneity among trials by inspecting the forest plots and using the Chi2 test and I2 statistic for heterogeneity with a statistical significance level of P < 0.10 and interpret I2 as follows (Higgins 2003):

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If we include at least 10 trials in any meta‐analysis, we will explore potential publication bias by generating a funnel plot and statistically testing by means of a linear regression test. We considered P < 0.1 as significant for this test (Sterne 2011). If we detect asymmetry, we will explore causes other than publication bias.

Data synthesis

We plan to perform analyses according to the recommendations of chapter 9 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011). We will use aggregated data for analysis. For statistical analysis, we will enter data into Review Manager 5.2 (RevMan 2013). One review author will enter data into the software and a second review author will check it for accuracy. We will perform meta‐analyses using a fixed‐effect model (e.g. the generic inverse variance method for survival data outcomes, the inverse variance method for continuous outcomes, and the Mantel‐Haenszel method for dichotomous data outcomes). We will use the random‐effects model in terms of sensitivity analyses. We will explore causes of heterogeneity by subgroup analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We plan to perform subgroup analyses on the following characteristics:

severe bleeds versus non‐severe bleeds;

high‐titer inhibitors versus low‐titer inhibitors.

Sensitivity analysis

We plan to undertake the following sensitivity analyses if possible:

quality components, including full text publications or abstracts, preliminary results versus mature results;

random‐effects modelling;

imputation of missing values.

Results

Description of studies

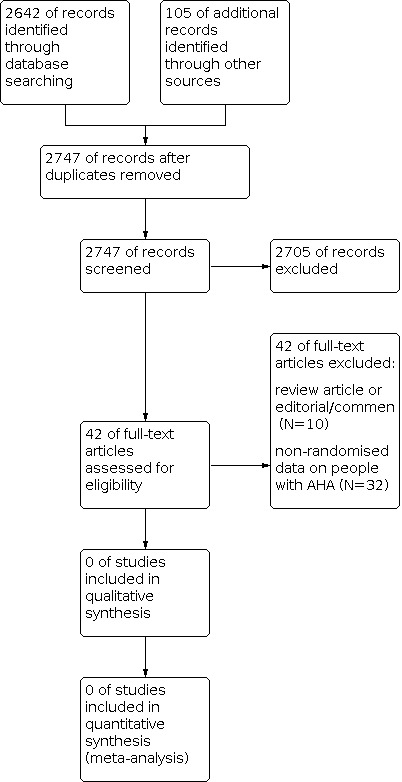

Results of the search

A total of 2747 references were identified by the search. Of these, 2705 were discarded as not being relevant and 42 were selected for closer inspection, but were ultimately excluded. Therefore, no RCTs were identified which met the inclusion criteria for this review.

Included studies

No trials were identified which were eligible for inclusion in the review.

Excluded studies

Reasons for exclusion were as follows (also see Figure 1):

1.

Study flow diagram.

review article, editorial or comment (N = 10); non‐randomised data on people with AHA (N = 32).

Risk of bias in included studies

No trials were identified which were eligible for inclusion in the review.

Effects of interventions

No trials were identified which were eligible for inclusion in the review.

Discussion

Summary of main results

No data from RCTs are available to show the optimal hemostatic therapy for treating bleeding episodes in people with AHA. This may be due to the rarity of AHA and the lack of development of consistent treatment protocols. Therefore, no conclusions and recommendations for clinical practice can currently be provided based on RCT‐derived evidence. Treatment guidelines and treatment decisions will continue to be supported by lower quality observational evidence (case‐series and a large prospective registry), which has been summarized in the Background section of this review and suggest that bypassing agents could cautiously be considered as the treatment most commonly used for bleeding in AHA. While caution and careful consideration on a case‐by‐case basis is needed, it has been noted that the recent prospective data collection of the EACH2 registry, while confirming the role of available agents in controlling bleeding, has found that treatment for hemorrhage is required less commonly than previously expected.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This review was unable to produce a novel synthesis of the evidence, given evidence from RCTs was unavailable. The available published evidence is based on observational studies of lower quality.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Due to an absence of RCTs eligible for inclusion, no implications for practice are generated by this review for or against any form of treatment. Given that carrying out RCTs in this field is a complex task, the authors suggest that, while planning RCTs in which patients can be enrolled, clinicians treating the disease continue to base their choices on alternative, lower quality sources of evidence, which hopefully, in the future, will also be appraised and incorporated in a Cochrane Review.

Implications for research.

This systematic review has identified the lack of well‐designed, adequately‐powered RCTs to assess the benefits and risks of the use of hemostatic therapies as a means of preventing or reducing bleeding in patients with AHA. However, formidable barriers exist to the proper planning and co‐ordination of comparative trials. Due to the low absolute number of patients and moderate occurrences of acute bleeding episodes in people with AHA, trials of similar design can only be conducted over a long period of time and across several centres in order to achieve the needed statistical power. Also, ethical considerations make designing such trials very complex (Temple 1982). Nonetheless, any active drug could be compared with alternative treatment modalities, and specific controlled study designs (risk allocation designs, sequential design, parallel cohort design) can be used to address particular issues of safety and efficacy (Lilford 1995; National Academies Press 2001).

Meanwhile, international prospective registries, collecting and maintaining data in agreement with high scientific standards, would be beneficial, as long as they allow the evaluation of patient‐important outcomes (Dreyer 2009). Simultaneously, patient registries designed explicitly to examine questions of comparative effectiveness could provide epidemiological, safety, comparative‐effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness data and could serve a wide spectrum of decision‐making purposes (Lipscomb 2009; Temple 1982). We strongly advocate the development and adoption of objective methods to assess, appraise and synthesise observational evidence as a base for systematic reviews when RCTs are not feasible.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 8 April 2021 | Review declared as stable | This is not an active area of research, therefore, we do not plan to update the review. Date of the most recent search: 30 April 2014. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 10, 2013 Review first published: Issue 8, 2014

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group for their help, and to Nikki Jahnke and Tracey Remmington for their expertise and technical support.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

1. MeSH descriptor hemophilia, factor VIII, inhibitor explode all trees

2. MeSH descriptor hemophilia, A, acquired, factor VIII, inhibitor explode all trees

3. (hemo*phi* NEAR/ A*)

4. (factor VIII* NEAR/ inhibitor*) or (factor VIII* NEAR/ autoantibodies*) or (factor VIII* NEAR/antibodies*) or (factor VIII* NEAR/autoimmune*)

5. (coagulation factors* NEAR/inhibitor*) or (coagulation factors* NEAR/ autoantibodies*) or (coagulation factors* NEAR/antibodies*) or (coagulation factors* NEAR/autoimmune*)

6. (acquired*) or (acquire*)

7. (#6 AND ( #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6))

8. (AH or AHA)

9. MeSH descriptor hemostatic explode all trees

10. (hemo*sta*NEAR/ agent*) or (hemo*sta* NEAR/ therapy*) or (hemo*sta* NEAR/ treatment*)

11. (bypassing agent*)

12. (rFVII* or recombinant activated FVII*)

13. (aPCC* or activated prothrombin complex concentrate*)

14. (FVIII* NEAR/human) or (FVIII* NEAR/porcine)

15. (DDAVP* or 1‐desamino‐8‐D‐arginine‐vasopressin*)

16. (#9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15)

17. ((#7 OR #8) AND #16)

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

1. exp HEMOPHILIA A/

2. exp ACQUIRED HEMOPHILIA A/

3. ((hemo?phi$ or haemo?phi$) adj (A)).tw,kf,ot.

4. (acquire$ or acquired$).tw,kf,ot.

5. 3 and 4

6. AH.tw.

7. AHA.tw.

8. or/6‐7

9. 1 or 2 or 5 or 8

10. exp HEMOSTATIC/

11. (hemostatic$ adj2 hemostasis$).tw,kf,ot.

12. 10 or 11

13. bypassing agent$.tw,kf,ot,nm.

14. FVII$.tw,kf,ot,nm.

15. aPCC$.tw,kf,ot,nm.

16. FVIII$.tw,kf,ot,nm.

17.DDAVP$.tw,kf,ot,nm.

18.or/13‐17

19.9 and 18

20.9 and (12 or 18)

21. randomized controlled trial.pt.

22. controlled clinical trial.pt.

23. randomized.ab.

24. placebo.ab.

25. drug therapy.fs.

26. randomly.ab.

27. trial.ab.

28. groups.ab.

29. or/21‐28

30. humans.sh.

31. 29 and 30

32. 19 and 31

33. 20 and 31

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Baudo 2004b | Not a RCT. Case series of 15 people with AHA treated with rFVII. |

| Baudo 2010 | Review article about diagnosis and treatment of AH. |

| Bossi 1998 | Not a RCT. Case series of 34 people with AHA. |

| Buczma 2007 | Review article about AH. |

| Burnet 2001 | Not a RCT. Case series of 8 people with AHA. |

| Chai‐Adisaksopha 2014 | Not a RCT. A single‐centre study and systematic review of 111 people with AHA. |

| Chistolini 1987 | Case report of a person with AHA treated with DDAVP. |

| Collins 2004 | Not a RCT. Case series of 18 people with AHA. |

| Collins 2007a | Not a RCT. Prospective analysis of 172 people with AHA. |

| Collins 2010 | Current guideline for AHA. |

| Coppola 2009 | Review article about diagnosis and treatment of AH. |

| de la Fuente 1985 | Case report of a person with AHA treated with DDAVP. |

| Delgado 2002 | Not a RCT. Retrospective analysis of 17 people with AHA. |

| Delgado 2003 | A systematic review and meta‐analysis about AHA therapy. |

| Di Bona 1997 | Not a RCT. Retrospective analysis of 17 people with AHA. |

| Di Capua 2014 | Case report of 4 people with AHA treated with rFVIIa. |

| EACH2 2012 | Not a RCT. Prospective analysis of 501 people with AHA. |

| Franchini 2008 | Review article about AHA. |

| Franchini 2011 | A systematic review about DDAVP in 37 people with AHA. |

| Franchini 2013 | Review article about AHA. |

| Goudemand 2004 | Not a RCT. Retrospective analysis of people with AHA treated with aPCC. |

| Hasson 1986 | Case report of 2 people with AHA. |

| Hay 1997 | Not a RCT. Retrospective analysis of 38 people with AHA treated with rFVII. |

| Hay 2006 | Current guideline for AHA. |

| Howland 2002 | Case report of 1 person with AHA treated with DDAVP. |

| Huth‐Kühne 2009 | Current guideline for AHA. |

| Ilkhchoui 2013 | Case report of a person with AHA treated with aPCC. |

| Kyaw 2013 | Case report of 3 people with AHA. |

| Ma 2011 | Not a RCT. Retrospective analysis of 87 people with AHA treated with rFVII. |

| Morrison 1993 | Not a RCT. Retrospective analysis of 65 people with AHA treated with porcine factor Vlll concentrate. |

| Mudad 1993 | Case report of a person with AHA treated with DDAVP. |

| Muhm 1990 | Case report of 3 people with AHA treated with DDAVP. |

| Naarose‐Abidi 1988 | Case report of 3 people with AHA treated with DDAVP. |

| Nilsson 1991 | Not a RCT. Retrospective analysis of 11 people with AHA treated with DDAVP. |

| Sallah 2004 | Not a RCT. Retrospective analysis of 87 people with AHA treated with aPCC. |

| Sborov 2013 | Second‐line therapeutic options for acute bleeding and inhibitor eradication. |

| Sumner 2007 | Not a RCT. Retrospective analysis of 139 people with AHA treated with rFVII. |

| Vincente 1985 | Case report of a person with AHA treated with DDAVP. |

| Vivaldi 1993 | Case report of 2 elderly people with AHA. |

| Yang 2013 | Not a RCT. Retrospective analysis of 49 people with AHA. |

| Yee 2000 | Not a RCT. Retrospective analysis of 24 people with AHA and 4 people with acquired von Willebrand disease treated with porcine factor VIII and aPCC. |

| Zanon 2013 | Not a RCT. Case report of 4 people with AHA treated with FVIII‐von Willebrand factor. |

AH: acquired hemophilia AHA: acquired hemophilia A aPCC: activated prothrombin complex concentrate DDAVP: 1‐desamino‐8‐D‐arginine‐vasopressin RCT: randomised controlled trial

Contributions of authors

Yan Zeng and Ruiqing Zhou have made the same contribution to this review.

| Roles and responsibilities | |

| TASK | WHO WILL UNDERTAKE THE TASK? |

| Protocol stage: draft the protocol | Zeng Yan, Zhou Ruiqing, Duan Xin |

| Review stage: select which trials to include (2 + 1 arbiter) | Zeng Yan, Zhou Ruiqing+ Long Dan |

| Review stage: extract data from trials (2 people) | Zeng Yan, Zhou Ruiqing |

| Review stage: enter data into RevMan | Zeng Yan |

| Review stage: carry out the analysis | Zeng Yan, Zhou Ruiqing |

| Review stage: interpret the analysis | Zeng Yan, Zhou Ruiqing, Yang Songtao |

| Review stage: draft the final review | Zeng Yan, Zhou Ruiqing, Duan Xin |

| Update stage: update the review | Zeng Yan, Zhou Ruiqing |

Sources of support

Internal sources

General Hospital of Chengdu Military Region, China

No. 4 West China Teaching Hospital, Sichuan University, China

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

None known.

Yan Zeng and Ruiqing Zhou have made the same contribution to this review.

Stable (no update expected for reasons given in 'What's new')

References

References to studies excluded from this review

Baudo 2004b {published data only}

- Baudo F, Cataldo F, Gaidano G. Treatment of acquired factor VIII inhibitor with recombinant activated factor VIIa: data from the Italian registry of acquired hemophilia. Haematologica 2004;89(6):759–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Baudo 2010 {published data only}

- Baudo F, Caimi T, Cataldo FDE. Diagnosis and treatment of acquired haemophilia. Haemophilia 2010;16(102):102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bossi 1998 {published data only}

- Bossi P, Cabane J, Ninet J, Dhote R, Hanslik T, Chosidow O, et al. Acquired hemophilia due to factor VIII inhibitors in 34 patients. American Journal of Medicine 1998 Nov;105(5):400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Buczma 2007 {published data only}

- Buczma A, Windyga J. Acquired haemophilia. Polskie Archiwum Medycyny Wewnętrznej 2007;117(5-6):241-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Burnet 2001 {published data only}

- Burnet SP, Duncan EM, Lloyd JV, Han P. Acquired haemophilia in South Australia: a case series. Internal Medicine Journal 2001;31(9):556-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chai‐Adisaksopha 2014 {published data only}

- Chai-Adisaksopha C, Rattarittamrong E, Norasetthada L, Tantiworawit A, Nawarawong W. Younger age at presentation of acquired haemophilia A in Asian countries: a single-centre study and systematic review. Haemophilia 2014;20(3):e205-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chistolini 1987 {published data only}

- Chistolini A, Ghirardini A, Tirindelli MC, et al. Inhibitor to factor VIII in a non-haemophilic patient: evaluation of the response to DDAVP and the in vitro kinetics of factor VIII. A case report. Nouvelle Revue Francaise d'Hematologie 1987;29(4):221-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collins 2004 {published data only}

- Collins P, Macartney N, Davies R, Lees S, Giddings J, Majer R. A population based, unselected, consecutive cohort of patients with acquired haemophilia A. British Journal of Haematology 2004;124(1):86-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collins 2007a {published data only}

- Collins PW, Hirsch S, Baglin TP, Dolan G, Hanley J, Makris M, et al. Acquired hemophilia A in the United Kingdom: a 2-year national surveillance study by the United Kingdom Haemophilia Centre Doctors' Organisation. Blood 2007;109(5):1870-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collins 2010 {published data only}

- Collins P, Baudo F, Huth-Kuhne A, Ingerslev J, Kessler CM, Castellano ME, et al. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of acquired hemophilia A. BMC Research Notes 2010;3:161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Coppola 2009 {published data only}

- Coppola A, Capua MD, Di Minno MND, Cerbone AM. Acquired Hemophilia: An Overview on Diagnosis and Treatment. Open Atherosclerosis & Thrombosis Journal 2009;2(2):29-32. [Google Scholar]

de la Fuente 1985 {published data only}

- la Fuente B, Panek S, Hoyer LW. The effect of 1-deamino 8 D-arginine vasopressin (DDAVP) in a nonhaemophilic patient with an acquired type II factor VIII inhibitor. British Journal of Haematology 1985;59(1):127-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Delgado 2002 {published data only}

- Delgado J, Villar A, Jimenez-Yuste V, Gago J, Quintana M, Hernandez-Navarro F. Acquired hemophilia: a single-center survey with emphasis on immunotherapy and treatment-related side-effects. European Journal of Haematology 2002;69(3):158-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Delgado 2003 {published data only}

- Delgado J, Jimenez-Yuste V, Hernandez-Navarro F, Villar A. Acquired haemophilia: review and meta-analysis focused on therapy and prognostic factors. British Journal of Haematology 2003;121(1):21-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Di Bona 1997 {published data only}

- Di Bona E, Schiavoni M, Castaman G, et al. Acquired hemophilia: experience of two Italian centres with 17 new cases. Haemophilia 1997;3:183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Di Capua 2014 {published data only}

- Di Capua M, Coppola A, Nardo A, Cimino E, Di Minno MN, Tufano A, et al. Management of bleeding in acquired haemophilia A with recombinant activated factor VII: does one size fit all? A report of four cases. Blood Transfusion 2014;19:1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

EACH2 2012 {published data only}

- Baudo F, Collins P, Huth-Kühne A, Lévesque H, Marco P, Nemes L, et al. Management of bleeding in acquired hemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia (EACH2) Registry. Blood 2012;120(1):39-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P, Baudo F, Knoebl P, Lévesque H, Nemes L, Pellegrini F, et al. Immunosuppression for acquired hemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia Registry (EACH2). Blood 2012;120(1):47-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoebl P, Marco P, Baudo F, Collins P, Huth-Kühne A, Nemes L, et al. Demographic and clinical data in acquired hemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia Registry (EACH2). Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2012;10(4):622-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tengborn L, Baudo F, Huth-Kühne A, Knoebl P, Lévesque H, Marco P, et al. Pregnancy-associated acquired haemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia (EACH2) registry. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2012;119(12):1529–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Franchini 2008 {published data only}

- Franchini M, Lippi G. Acquired factor VIII inhibitors. Blood 2008;112(2):250-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Franchini 2011 {published data only}

- Franchini M, Lippi G. The use of desmopressin in acquired haemophilia A: a systematic review. Blood Transfusion 2011;9(4):377-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Franchini 2013 {published data only}

- Franchini M, Mannucci PM. Acquired haemophilia A: a 2013 update. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2013;110(6):1114-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goudemand 2004 {published data only}

- Goudemand J. Treatment of bleeding episodes occurring in patients with acquired haemophilia with FEIBA: the French experience. Haemophilia 2004;10 Suppl 3:14. [Google Scholar]

Hasson 1986 {published data only}

- Hasson DM, Poole AE, la Fuente B, Hoyer LW. Dental management of patients with spontaneous acquired factor VIII inhibitors. Journal of the American Dental Association 1986;113(4):633-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hay 1997 {published data only}

- Hay CRM, Negrier C, Ludlam CA. The treatment of bleeding in acquired haemophilia with recombinant factor VIIa: a multicentre study. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 1997;78(6):3-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hay 2006 {published data only}

- Hay CR, Brown S, Collins PW, KeelingDM, Liesner R. The diagnosis and management of factor VIII and IX inhibitors: a guideline from the United Kingdom Haemophilia Centre Doctors Organisation. British Journal of Haematology 2006;133(6):591-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Howland 2002 {published data only}

- Howland EJ, Palmer J, Lumley M, Keay SD. Acquired factor VIII inhibitors as a cause of primary post-partum haemorrhage. European Jouurnal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 2002;103(1):97-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Huth‐Kühne 2009 {published data only}

- Huth-Kühne A, Baudo F, Collins P, Ingerslev J, Kessler CM, Lévesque H, et al. International recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of patients with acquired hemophilia A. Haematologica 2009;94(4):566-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ilkhchoui 2013 {published data only}

- Ilkhchoui Y, Koshkin E, Windsor JJ, Petersen TR, Charles M, Pack JD. Perioperative management of acquired hemophilia a: a case report and review of literature. Anestheisiology and Pain Medicine 2013;4(1):e11906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kyaw 2013 {published data only}

- Kyaw TZ, Jayaranee S, Bee PC, Chin EF. Acquired Factor VIII Inhibitors: Three Cases. Turkish Journal of Hematology 2013;30(1):76-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ma 2011 {published data only}

- Ma A, Kessler CM, Gut RZ, Cooper DL. Treatment of acquired haemophilia with recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa): an updated analysis from the hemophilia and thrombosis research society (HTRS) registry. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2011;9(Suppl 2):476. [Google Scholar]

Morrison 1993 {published data only}

- Morrison AE, Ludlam CA, Kessler C. Use of Porcine Factor VIII in the Treatment of Patients With Acquired Hemophilia. Blood 1993;81(6):1513-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mudad 1993 {published data only}

- Mudad R, Kane WH. DDAVP in acquired hemophilia A: case report and review of the literature. American Journal of Hematology 1993;43(4):295-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Muhm 1990 {published data only}

- Muhm M, Grois N, Kier P, Stümpflen A, et al. 1-Deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin in the treatment of non-haemophilic patients with acquired factor VIII inhibitor. Haemostasis 1990;20(1):15-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Naarose‐Abidi 1988 {published data only}

- Naarose-Abidi SM, Bond LR, Chitolie A, Bevan DH. Desmopressin therapy in patients with acquired factor VIII inhibitors. Lancet 1988;1(8581):366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nilsson 1991 {published data only}

- Nilsson IM, Lethagen S. Current status of DDAVP formulations and their use. Excerpta Medica 1991;943:443-53. [Google Scholar]

Sallah 2004 {published data only}

- Sallah S. Treatment of acquired haemophilia with factor eight inhibitor bypassing activity. Haemophilia 2004;10(2):169-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sborov 2013 {published data only}

- Sborov DW, Rodgers GM. How I manage patients with acquired haemophilia A. British Journal of Haematology 2013;161(2):157-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sumner 2007 {published data only}

- Sumner MJ, Geldziler BD, Pedersen M, Seremetis S. Treatment of acquired haemophilia with recombinant activated FVII: a critical appraisal. Haemophilia 2007;13(5):451-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vincente 1985 {published data only}

- Vincente V, Corrales J, Miralles J, Alberca I. DDAVP in a non-haemophiliac patient with an acquired factor VIII inhibitor. British Journal of Haematology 1985;60:585-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vivaldi 1993 {published data only}

- Vivaldi P, Savino M, Mazzon C, Rubertelli M. A hemorrhagic syndrome of the elderly patient caused by anti-factor VIII antibodies. Haematologica 1993;78:245-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yang 2013 {published data only}

Yee 2000 {published data only}

- Yee TT, Taher A, Pasi KJ, Lee CA. A survey of patients with acquired haemophilia in a haemophilia centre over a 28-year period. Clinical and Laboratory Haematology 2000;22(5):275-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zanon 2013 {published data only}

- Zanon E, Milan M, Brandolin B, Barbar S, Spiezia L, Saggiorato G, et al. High dose of human plasma-derived FVIII-VWF as first-line therapy in patients affected by acquired haemophilia A and concomitant cardiovascular disease: four case reports and a literature review. Haemophilia 2013;19(1):e50-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Abshire 2004

- Abshire T, Kenet G. Recombinant factor VIIa: review of efficacy, dosing regimens and safety in patients with congenital and acquired factor VIIIor IX inhibitors. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2004;2(6):899-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ananyeva 2009

- Ananyeva NM, Lee TK, Jain N, Shima M, Saenko EL. Inhibitors in hemophilia A: advances in elucidation of inhibitory mechanisms and in inhibitor management with bypassing agents. Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis 2009;35(8):735-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Baudo 2003

- Baudo F, Mostarda G, Cataldo F. Acquired factor VIII and factor IX inhibitors: survey of the Italian haemophila centers (AICE). Haematologica 2003;88 Suppl 12:93-9. [Google Scholar]

Baudo 2004a

- Baudo F, Cataldo F. Acquired hemophilia: acritical bleeding syndrome. Haematologica 2004;89(1):96-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Baudo 2007

- Baudo F, Cataldo F. Acquired haemophilia in the elderly. In: Balducci L, Ershler W, Gaetano G, editors(s). Blood Disorders in the Elderly. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007:389–407. [Google Scholar]

Baudo 2012

- Baudo F, Collins P, Huth-Kühne A, Lévesque H, Marco P, Nemes L, et al. Management of bleeding in acquired hemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia (EACH2) Registry. Blood 2012;120(1):39-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boggio 2001

- Boggio LN, Green D. Acquired hemophilia. Reviews in Clinical and Experimental Hematology 2001;5(4):389-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collins 2007b

- Collins PW. Treatment of acquired hemophilia A. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2007;5(5):893-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collins 2012

- Collins P, Baudo F, Knoebl P, Lévesque H, Nemes L, Pellegrini F, et al. Immunosuppression for acquired hemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia Registry (EACH2). Blood 2012;120(1):47-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deeks 2011

- Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG, on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. Chapter 9: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analysis. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.

de la Fuente 1995

- la Fuente B, Panek S, Hoyer LW. The effect of 1-deamino 8 D-arginine vasopressin (DDAVP) in a nonhaemophilic patient with an acquired type II factor VIII inhibitor. British Journal of Haematology 1985;59(1):127-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dreyer 2009

- Dreyer NA, Garner S. Registries for robust evidence. JAMA 2009;302(7):790-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Elbourne 2002

- Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Higgins JPT, Curtin F, Worthington HV, Vail A. Meta-analysis involving cross-over trials:methodological issues. International Journal of Epidemiology 2002;31(1):140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Franchini 2008a

- Franchini M, Tragher G, Manzato F, Lippi G. Acquired factor VIII inhibitors in oncohematology: a systematic review. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2008;66(3):194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Green 1981

- Green D, Lechner K. A survey of 215 non-hemophilic patients with inhibitors to factor VIII. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 1981;45(3):200-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327(7414):557-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011a

- Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ (editors). Chapter 7: Selecting studies and collecting data. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Higgins 2011b

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC, on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group and the Cochrane Bias Methods Group (editors). Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Higgins 2011c

- Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ, Altman DG, on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. Chapter 16: Special topics in statistics. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Knoebl 2012

- Knoebl P, Marco P, Baudo F, Collins P, Huth-Kühne A, Nemes L, et al. Demographic and clinical data in acquired hemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia Registry (EACH2). Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2012;10(4):622-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lefebvre 2011

- Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J. Chapter 6: Searching for studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Lethagen 1987

- Lethagen S, Harris AS, Sjorin E, Nilsson IM. Intranasal and intravenous administration of desmopressin: effect on FVIII/vWF, pharmacokinetics and reproducibility. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 1987;58(4):1033-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lilford 1995

- Lilford RJ, Thornton JG, Braunholtz D. Clinical trials and rare diseases: a way out of a conundrum. BMJ 1995;311(7020):1621-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lipscomb 2009

- Lipscomb J, Yabroff R, Brown ML. Health care costing: data, methods, current applications. Medical Care 2009;47(7 Suppl 1):S1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meiklejohn 2001

- Meiklejohn DJ, Watson HG. Acquired haemophilia in association with organ-specific autoimmune disease. Haemophilia 2001;7(5):523-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Naarose‐Abidi 1988

- Naarose-Abidi SM, Bond LR, Chitolie A, Bevan DH. Desmopressin therapy in patients with acquired factor VIII inhibitors. Lancet 1988;1(8581):366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

National Academies Press 2001

- Committee on Strategies for Small-Number-Participant Clinical Research Trials, Board on Health Sciences Policy. Small Clinical Trials: Issues and Challenges (The National Academies Press). http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=10078 (accessed 30 January 2014).

Parmar 1998

- Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Statistics in Medicine 1998;17(24):2815-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2013 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.2. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012.

Sterne 2011

- Sterne JAC, Egger M, Moher D, on behalf of the Cochrane Bias Methods Group. Chapter 10: Addressing reporting biases. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Temple 1982

- Temple RJ. Government viewpoint of clinical trials. Drug Information Journal 1982;16:10-7. [Google Scholar]

Tengborn 2012

- Tengborn L, Baudo F, Huth-Kuhne A, Knoebl P, Levesque H, Marco P, et al. Pregnancy-associated acquired haemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia (EACH2) registry. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2012;119(12):1529-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tierney 2007

- Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 2007;8:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Turecek 2004

- Turecek PL, Váradi K, Gritsch H, Schwarz HP. FEIBA: mode of action. Haemophilia 2004;10 Suppl 2:3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Verbruggen 1995

- Verbruggen B, Novakova I, Wessels H, Boezeman J, den Berg M, Mauser-Bunschoten E. The Nijmegen modification of the Bethesda assay for factor VIII:C inhibitors: improved specificity and reliability. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 1995;73(2):247-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]