PURPOSE

Recurrently mutated genes and chromosomal abnormalities have been identified in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). We aim to integrate these genomic features into disease classification and prognostication.

METHODS

We retrospectively enrolled 2,043 patients. Using Bayesian networks and Dirichlet processes, we combined mutations in 47 genes with cytogenetic abnormalities to identify genetic associations and subgroups. Random-effects Cox proportional hazards multistate modeling was used for developing prognostic models. An independent validation on 318 cases was performed.

RESULTS

We identify eight MDS groups (clusters) according to specific genomic features. In five groups, dominant genomic features include splicing gene mutations (SF3B1, SRSF2, and U2AF1) that occur early in disease history, determine specific phenotypes, and drive disease evolution. These groups display different prognosis (groups with SF3B1 mutations being associated with better survival). Specific co-mutation patterns account for clinical heterogeneity within SF3B1- and SRSF2-related MDS. MDS with complex karyotype and/or TP53 gene abnormalities and MDS with acute leukemia–like mutations show poorest prognosis. MDS with 5q deletion are clustered into two distinct groups according to the number of mutated genes and/or presence of TP53 mutations. By integrating 63 clinical and genomic variables, we define a novel prognostic model that generates personally tailored predictions of survival. The predicted and observed outcomes correlate well in internal cross-validation and in an independent external cohort. This model substantially improves predictive accuracy of currently available prognostic tools. We have created a Web portal that allows outcome predictions to be generated for user-defined constellations of genomic and clinical features.

CONCLUSION

Genomic landscape in MDS reveals distinct subgroups associated with specific clinical features and discrete patterns of evolution, providing a proof of concept for next-generation disease classification and prognosis.

INTRODUCTION

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are heterogeneous clonal hematopoietic disorders characterized by peripheral blood cytopenia and increased risk of evolution into acute myeloid leukemia (AML).1 Current disease classification provided by WHO mainly uses morphological features to define MDS categories, leading to a clinical overlap between subtypes and to low interobserver reproducibility in the evaluation of marrow dysplasia.2-4

CONTEXT

Key Objective

In myeloid malignancies, classifications on the basis of clinical and morphological criteria are being complemented by genomic features that better capture clinical-pathological entities. In myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), there is clearly a need to define specific genotype-phenotype correlations and to estimate the independent effect of each genomic abnormality on clinical outcome.

Knowledge Generated

We provided evidence form a large, international database that MDS could be classified into eight distinct subtypes according to specific genomic features. These subgroups do not correlate with morphological categories defined by current WHO classification and displayed significantly different clinical phenotypes and outcome. By integrating clinical and genomic variables, we created a novel prognostic model that generated personally tailored predictions of survival.

Relevance

Comprehensive gene sequencing of patients with MDS is becoming increasingly accessible and routine. The integration of clinical data with diagnostic genome profiling improves the accuracy of currently available prognostic scores. Such information will support complex decision-making process in these patients.

MDS range from indolent conditions to cases rapidly progressing into AML.5,6 Disease-related risk is assessed by International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) on the basis of percentage of bone marrow blasts, number of peripheral blood cytopenias, and presence of specific clonal cytogenetic abnormalities.7 In 2012, a revised version of IPSS (IPSS-R) was proposed by introducing five cytogenetic risk groups together with refined categories for bone marrow blasts and cytopenias.7 Although IPSS and IPSS-R are excellent tools for clinical decision making, these scoring systems have their own weaknesses and may fail to capture reliable prognostic information at individual patient level. In particular, cytogenetics (which is the only biological parameter included in these scores) is not informative in a large proportion of patients and chromosomal abnormalities mostly refer to secondary, late genomic events occurring in the natural history of the disease.8

The development of MDS is driven by mutations on genes involved in RNA splicing, DNA methylation, chromatin modification, transcriptional regulation, and signal transduction.9-12 Chromosomal abnormalities also contribute to MDS pathophysiology.13 Despite recent progress in understanding the disease biology, MDS with isolated 5q deletion is the only category defined by a specific genomic abnormality in the WHO classification2 and only few genotype-phenotype associations have been reported until now, mainly referring to the close relationship between mutations in SF3B1 gene and MDS subtypes with ring sideroblasts.2,9-12

In myeloid malignancies, classifications on the basis of clinical and morphological criteria are being complemented by introducing genomic features that are closer to the disease biology and better capture clinical-pathological entities.2,14-16 In this study, we aim to define a new genomic classification of MDS and to improve individual prognostic assessment moving from systems on the basis of clinical parameters to models including genomic information.

METHODS

Study Populations

The Humanitas Research Hospital Ethics Committee approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. The study was conducted by EuroMDS consortium (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04174547). We analyzed an international retrospective cohort of 2,043 patients affected with primary MDS according to 2016 WHO criteria2 and an independent cohort of 318 patients prospectively diagnosed at Humanitas Research Hospital, Milan, Italy (Data Supplement 1, online only).

Genomic Screening

At diagnosis, cytogenetic analysis was performed using standard G-banding and karyotypes were classified using the International System for Cytogenetic Nomenclature Criteria. Mutation screening of 47 genes related to myeloid neoplasms was performed on DNA from peripheral blood granulocytes or bone marrow mononuclear cells (Data Supplement 1).

Statistical Methods

Detailed methods are reported in the Data Supplement 1.

Bradley-Terry models are used to estimate timing of mutation acquisition and to assess the prognostic value of clonal versus subclonal mutations.12

Bayesian network analysis and hierarchical Dirichlet processes are used to identify genomic associations and subgroups as a basis to define a molecular classification of MDS.14-16 Bayesian networks allow to infer the structure of conditional dependencies among mutations, that is, how the presence of a given mutation influences the probability of the others (causality). Dirichlet processes are applied to define clusters capturing broad dependencies among all gene mutations and cytogenetic abnormalities.12,14-16 Patients are clustered based on genomic components identified by Dirichlet processes. Multivariate logistic regression analysis is applied to compare clinical and hematological characteristics among different groups. Survival analyses are performed with Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between groups are evaluated by log-rank test. To carry out the analysis, R package available online17 is used.

Random-effects Cox proportional hazards multistate modeling was used for developing innovative prognostic tools including clinical parameters and genomics.18,19 With the aim to help clinicians to be familiar with such a next-generation prognostic tool, we have created a prototype Web portal that allows outcome predictions to be generated based on this data set for user-defined constellations of genomic features and clinical variables.

All the analyses were carried out on EuroMDS cohort. The Humanitas cohort was used to independently validate models for patient prognostication.

RESULTS

Genomic Landscape in Myelodysplastic Syndromes

Detailed results of this section are reported in the Data Supplement 1.

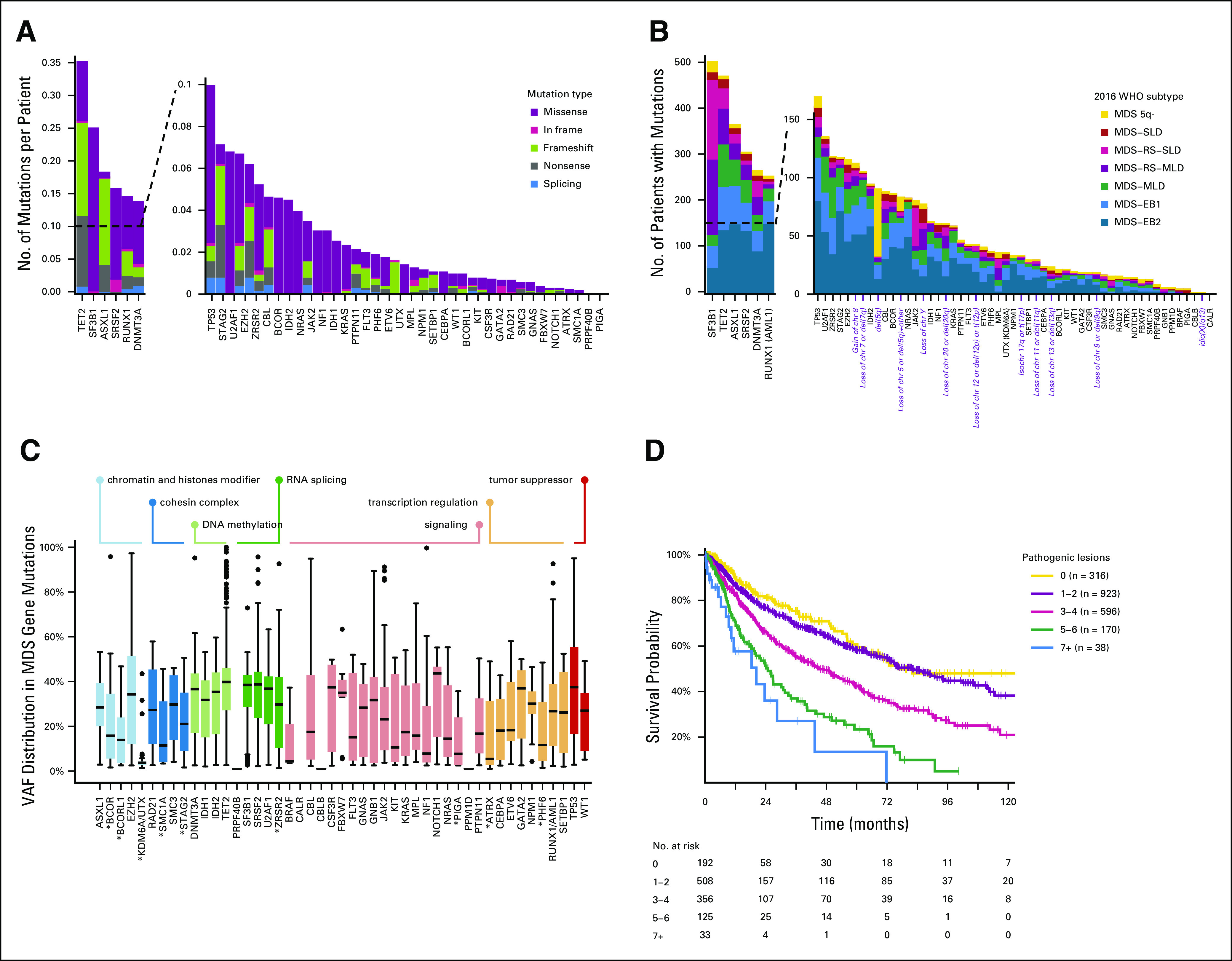

We studied 2,043 patients with MDS from EuroMDS consortium (Data Supplement 1). Normal karyotype is reported in 1,195 patients (59%), whereas 651 (32%) showed chromosomal abnormalities (Data Supplement). Mutations are identified in 45 of 47 genes. A total of 1,630 patients (80%) present one or more mutations (median, 2; range, 1-17). Only six genes are mutated in > 10% of patients, with five additional genes mutated in 5%-10%, and 36 mutated in < 5% of patients (Fig 1, Data Supplement 1 and Data Supplement 2).

FIG 1.

(A) Frequency of mutations and chromosomal abnormalities in the EuroMDS cohort (N = 2,043), stratified according to the type of mutation (missense, nonsense, affecting a splice site, or other). Insertions and deletions (del) were categorized according to whether they resulted in a shift in the codon reading frame (by either 1 or 2 base pairs [bp]) or were in frame. Splicing factor genes were the most frequently mutated (49%), followed by DNA methylation–related genes (37.9%), chromatin and histone modifier genes (31.3%), signaling genes (28.5%), transcription regulation genes (24%), tumor suppressor genes (11.1%), and cohesin complex genes (7.6%). (B) Frequency of recurrently mutated genes and chromosomal abnormalities in the EuroMDS cohort, broken down by MDS subtype according to 2016 WHO criteria. (C) VAF of driver mutations in the EuroMDS cohort, broken down by gene and gene function (boxplots reporting median, 25-75 percentiles, and ranges); VAF of X-linked genes (ATRX, BCOR, BCORL1, PHF6, PIGA, SMC1A, STAG2, UTX, and ZRSR2, highlighted by asterisk in the figure plot) was halved in male patients. (D) Relationship between the number of genomic abnormalities (mutations and chromosomal abnormalities) and outcome (overall survival). MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; MDS 5q-, MDS with isolated deletion of long arm of chromosome 5; MDS-EB1, MDS with excess of blasts, type 1; MDS-EB2, MDS with excess of blasts, type 2; MDS-MLD, MDS with multilineage dysplasia; MDS-RS-MLD, MDS with ring sideroblasts and multilineage dysplasia; MDS-RS-SLD, MDS with ring sideroblasts and single-lineage dysplasia; MDS-SLD, MDS with single-lineage dysplasia; VAF, variant allele frequencies.

Mutation Acquisition Order and Prognostic Value of Clonal Versus Subclonal Mutations

Detailed results are reported in the Data Supplement 1.

By using Bradley-Terry modeling, we calculate a global ranking of MDS genes reflecting how early in disease natural history they are mutated. Mutations in genes involved in RNA splicing and DNA methylation occur early, whereas mutations in genes involved in chromatin modification and signaling often occur later (Data Supplement 1).

A total of 14 genes are associated with worse prognosis if mutated, whereas one gene (SF3B1) is associated with better outcome (Data Supplement 1). Variant allele fractions are used to estimate the proportion of tumor cells carrying a given mutation and identify clonal or subclonal mutations. Accordingly, 58% of patients show only clonal mutations, whereas 42% have evidence for both clonal and subclonal mutations (Data Supplement 1). No significant differences in survival between clonal and subclonal mutations for the majority of the investigated genes are observed, highlighting the importance of including information on subclonal mutations in the predictive model (Data Supplement 1).

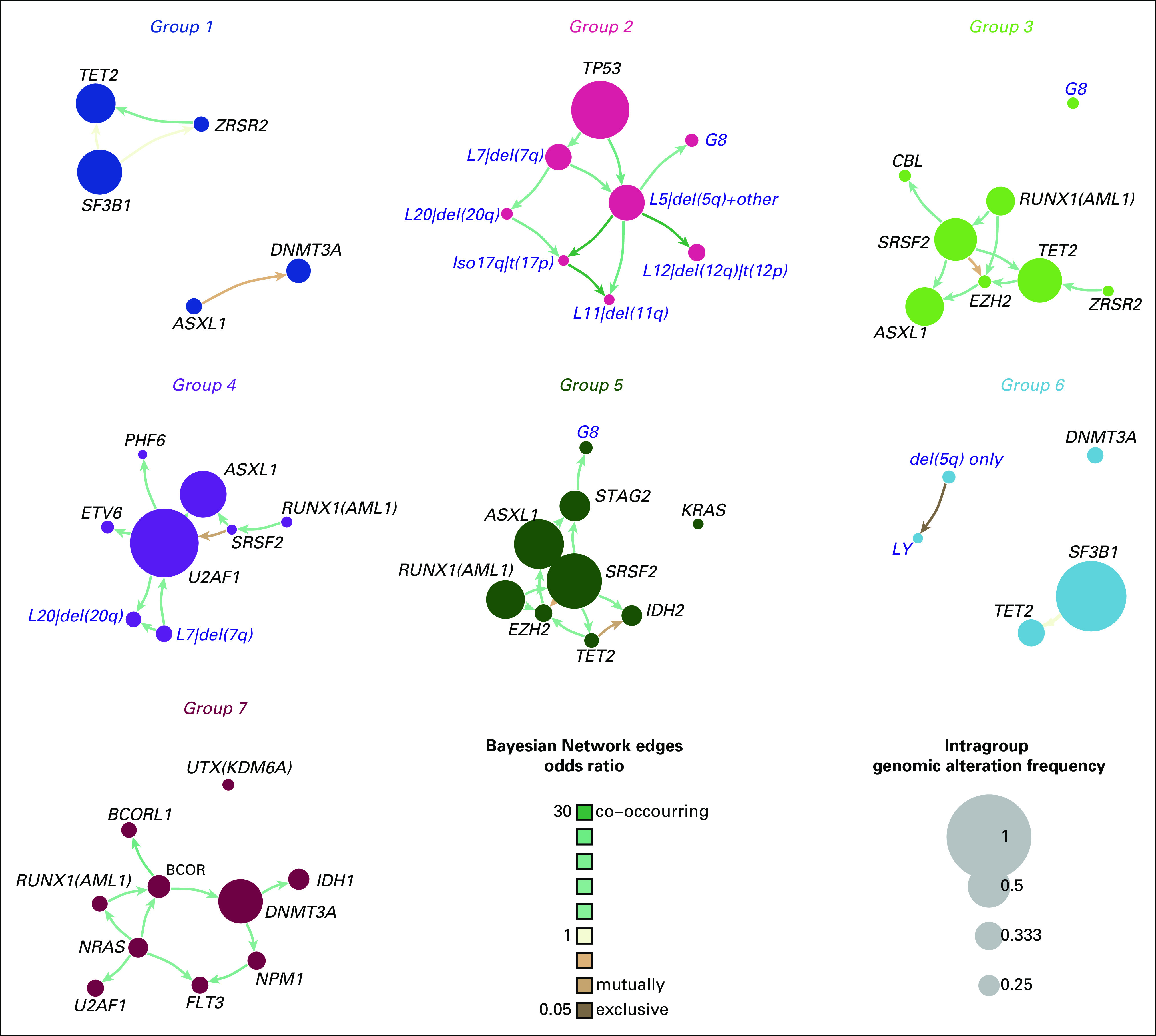

Identification of Genomic Associations and Subgroups in Myelodysplastic Syndromes

Detailed results are reported in the Data Supplement 1.

Pairwise associations among genes and cytogenetic abnormalities reveal a complex landscape of positive and negative associations (Data Supplement 1). Bayesian networks are applied to define in a more comprehensive way the relationships between genomic abnormalities (Data Supplement 1). Accordingly, mutations of splicing genes are mutually exclusive. SF3B1 mutations are mutually exclusive with TP53 mutations, whereas they co-occur with JAK/STAT pathway mutations. SRSF2 mutations co-occur with TET2, ASXL1, CBL, IDH1/2, RUNX1, and STAG2 mutations. U2AF1 mutations co-occur with abnormalities of chromosome 7 and 20 and NRAS mutations. TET2 mutations co-occur with SRSF2 and ZRSR2 mutations. DNMT3A mutations are mutually exclusive with ASXL1 mutations, whereas they co-occur with BCOR, IDH1, and NPM1 mutations. 5q deletion is frequently present as a single genomic abnormality, whereas a co-occurrence with TP53 mutations and with several single cytogenetic components of complex karyotype is observed (Data Supplement 1).

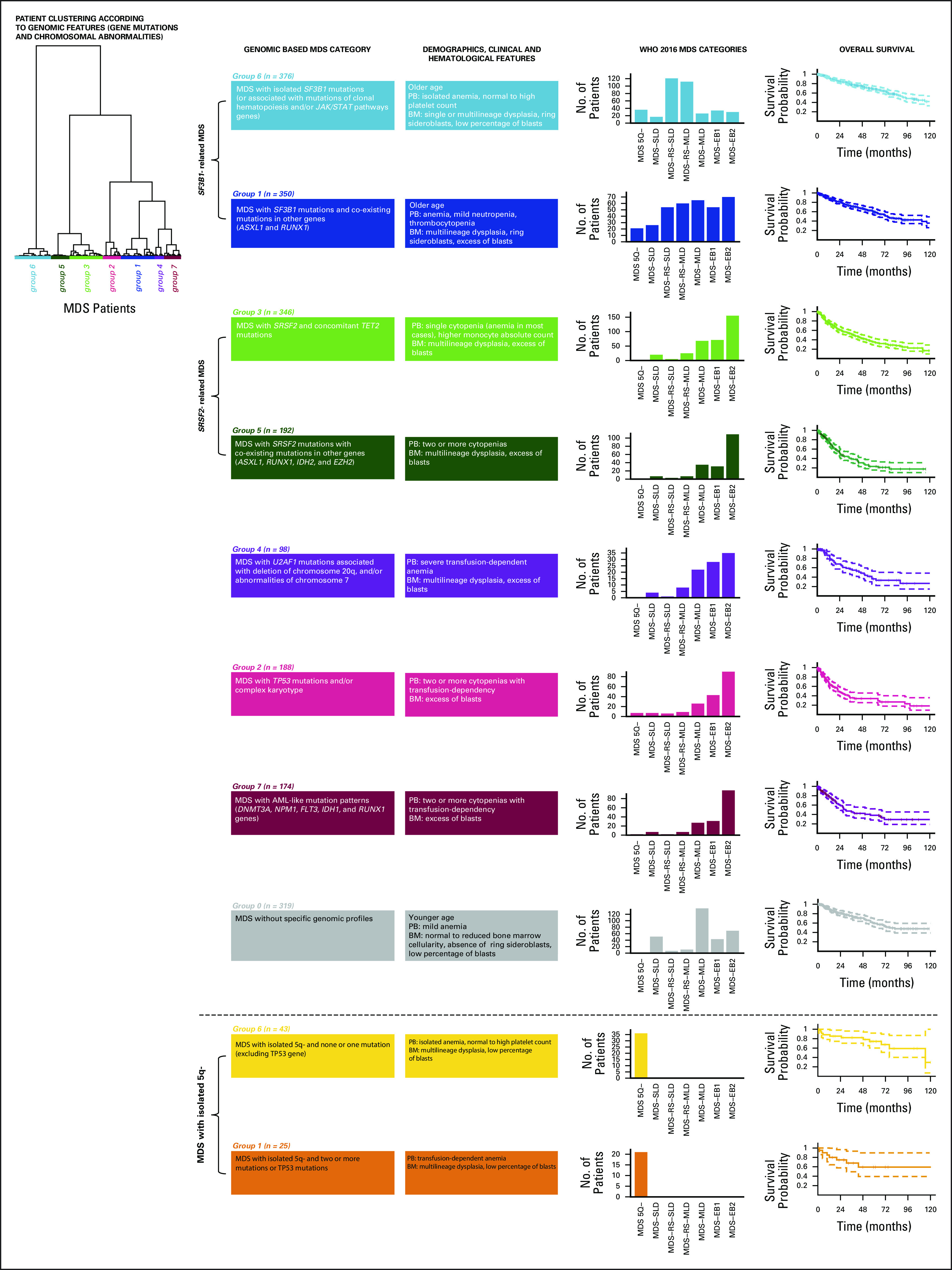

Definition of a Genomic Classification of Myelodysplastic Syndromes

Dirichlet processes are used to identify genomic subgroups among MDS (Data Supplement 1). We identify six components, each describing a specific distribution of variables included in the model (ie, cytogenetic abnormalities and gene mutations [Data Supplement 1]). Each patient is characterized by a weight vector indicating the contribution of each component to its genome. By performing hierarchical agglomerative clustering, we obtain eight groups (clusters) defined according to specific genomic features (Appendix [online only], Data Supplement 1).

One group includes patients without specific genomic profiles (ie, without recurrent mutations in the study genes and/or chromosomal abnormalities); strikingly, all the remaining groups are deeply characterized by a single (in some cases two) component of Dirichlet processes (Data Supplement 1). In many groups, dominant genomic features include splicing gene mutations. We identify two groups (1 and 6) in which dominant features are SF3B1 mutations, presence of ring sideroblasts, and transfusion-dependent anemia (Appendix). Group 6 includes patients with ring sideroblasts and isolated SF3B1 mutations (except for co-mutation patterns including TET2, DNMT3A, and JAK/STAT pathway genes) characterized by isolated anemia, normal or high platelet count, single or multilineage dysplasia, and low percentage of marrow blasts (median, 2%). Group 1 includes patients with SF3B1 with co-existing mutations in other genes (ASXL1 and RUNX1) characterized by anemia associated with mild neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, multilineage dysplasia, and higher marrow blast percentage with respect to group 6 (7% v 2%, P < .0001).

In two groups (3 and 5), dominant genomic features are represented by SRSF2 mutations (Appendix). In these groups, the most frequently reported chromosomal abnormality is trisomy 8 (Data Supplement 1). Group 3 includes patients with SRSF2 and concomitant TET2 mutations. Patients present single cytopenia (anemia in most cases) and higher monocyte absolute count with respect to the other groups (P < .0001). Bone marrow features include multilineage dysplasia and excess blasts (median, 8%). Group 5 is characterized by SRSF2 mutations with co-existing mutations in other genes (ASXL1, RUNX1, IDH2, and EZH2). Patients present two or more cytopenias, multilineage dysplasia, and excess blasts (median, 11%; significantly higher with respect to group 3; P = .0031).

Group 4 dominant features include U2AF1 mutations associated with 20q deletion and chromosome 7 abnormalities (Appendix, Data Supplement 1). Patients present a higher rate of transfusion-dependent anemia with respect to the other groups (P from .023 to < .0001). Marrow features include multilineage dysplasia and excess blasts in most cases.

Group 2 is characterized by TP53 mutations and/or complex karyotype. In most patients, two or more cytopenias (with high rate of transfusion dependency) and excess blasts are present (Appendix, Data Supplement 1).

Group 7 includes patients with AML-like mutation patterns (DNMT3A, NPM1, FLT3, IDH1, and RUNX1 genes). Patients are characterized by two or more cytopenias (with high rate of transfusion dependency) and excess blasts, in most cases (83%) ranging from 15% to 19% (Appendix).

Finally, group 0 includes MDS without specific genomic profiles. These patients are characterized by younger age, isolated anemia, normal or reduced marrow cellularity (with respect to age-adjusted normal ranges), absence of ring sideroblasts, and low percentage of marrow blasts (median, 2%) (Appendix).

A heterogeneous distribution of 2016 WHO disease subtypes is observed through the new groups defined by genomic features (P < .0001, Appendix). Interestingly, this new classification accounts for genomic heterogeneity of patients stratified according to WHO criteria. This is evident for MDS with isolated 5q deletion. Patients with none or one mutation (mainly including SF3B1 gene) are clustered into group 6, whereas those with two or more mutations or TP53 mutations are classified into group 1 (Appendix). MDS with 5q deletion included into group 6 show lower rate of transfusion dependency and lower percentage of marrow blasts with respect to patients classified into group 1 (P = .0043 and P < .0001).

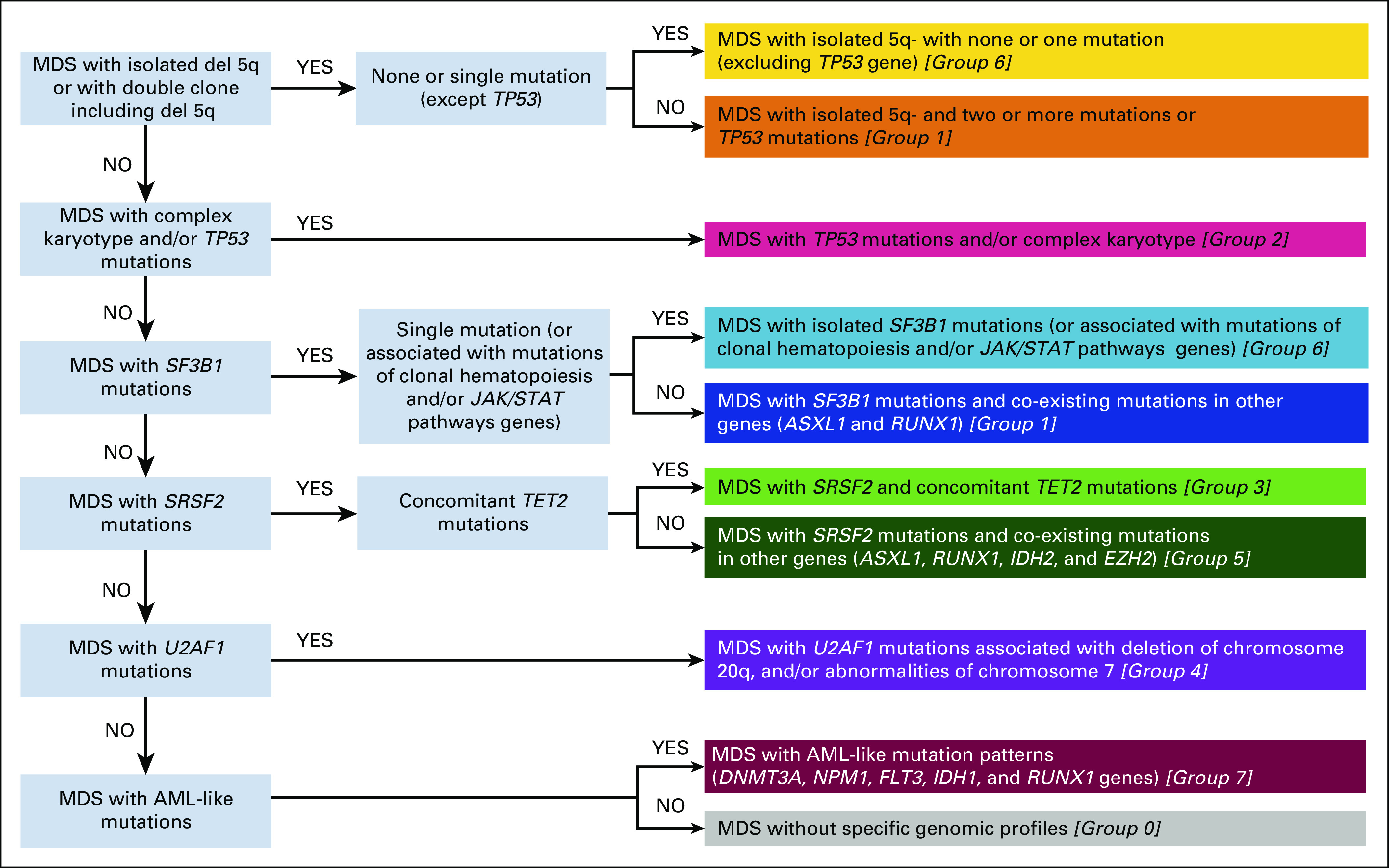

These findings provide the proof of concept for a new classification of MDS on the basis of entities defined according to specific genomic features. In the Appendix, we define a diagram to classify patients in the appropriate category on the basis of individual genomic profile.

Clinical Relevance of Genomic Classification of Myelodysplastic Syndromes in Predicting Survival and Response to Specific Treatments

Genomic-based MDS groups present different probability of survival (Appendix, P < .0001), suggesting that the integration of genomic features may improve the capability to capture prognostic information. Groups 1 and 6 characterized by SF3B1 mutations show better survival with respect to groups 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 (P from < .0001 to .0093), isolated SF3B1 (group 6) being associated with better outcome with respect to SF3B1 with co-mutated patterns (group 1, P = .0304). Group 0 including patients without specific genomic abnormalities is associated with good prognosis as well (P from < .0001 to .012 with respect to groups 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7). Groups defined by splicing mutations other than SF3B1 show worse survival; among them, group 5 (SRSF2 mutations with co-existing mutations in other genes) is associated with dismal outcome (P from < .0001 to .0177 with respect to groups 0, 1, 4, and 6). Group 2 including patients with TP53 mutations and complex karyotype shows the poorest outcome (P from < .0001 to .0473). Group 7 including patients with AML-like mutations shows high rate of leukemic evolution and worse prognosis as well (P < .0001 with respect to groups 1, 3, and 6). Finally, among patients with isolated 5q deletion, cases with none or single mutation are associated with a better prognosis with respect to those with two or more mutations or TP53 mutations (P = .0432).

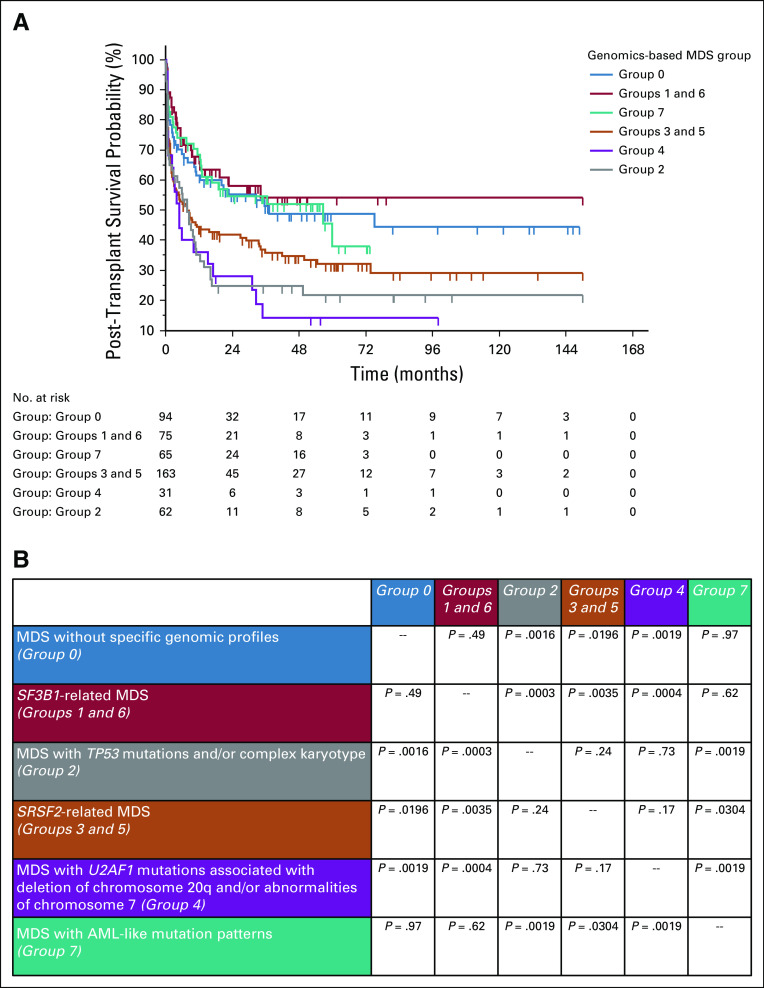

Then, we tested whether grouping MDS patients according to genomic features may provide information about response to specific treatments. We focused on 424 cases who underwent allogeneic transplantation and on 221 cases treated with hypomethylating agents. With the limit to analyze a retrospective cohort of selected patients, MDS groups on the basis of genomic features do not identify different probability of survival after hypomethylating agents (not shown), whereas they are able to significantly stratify post-transplantation outcome (Fig 2). SF3B1-related groups (groups 1 and 6), MDS with AML-like mutations (group 7), and MDS without specific genomic abnormalities (group 0) show a better outcome after transplant, whereas groups defined by TP53 mutation and/or complex karyotype (group 2) and by U2AF1 mutations (group 4) are associated with a high rate of transplantation failure (Fig 2).

FIG 2.

(A) Probability of overall survival after allogeneic transplantation in the EuroMDS cohort. Patients were stratified according to specific genomic features. A total of 424 cases with complete information about transplant procedures and clinical outcome entered the analysis. (B) Comparison of probability of survival among different genomic-based MDS groups (P values of log-rank test were reported). AML, acute myeloid leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes.

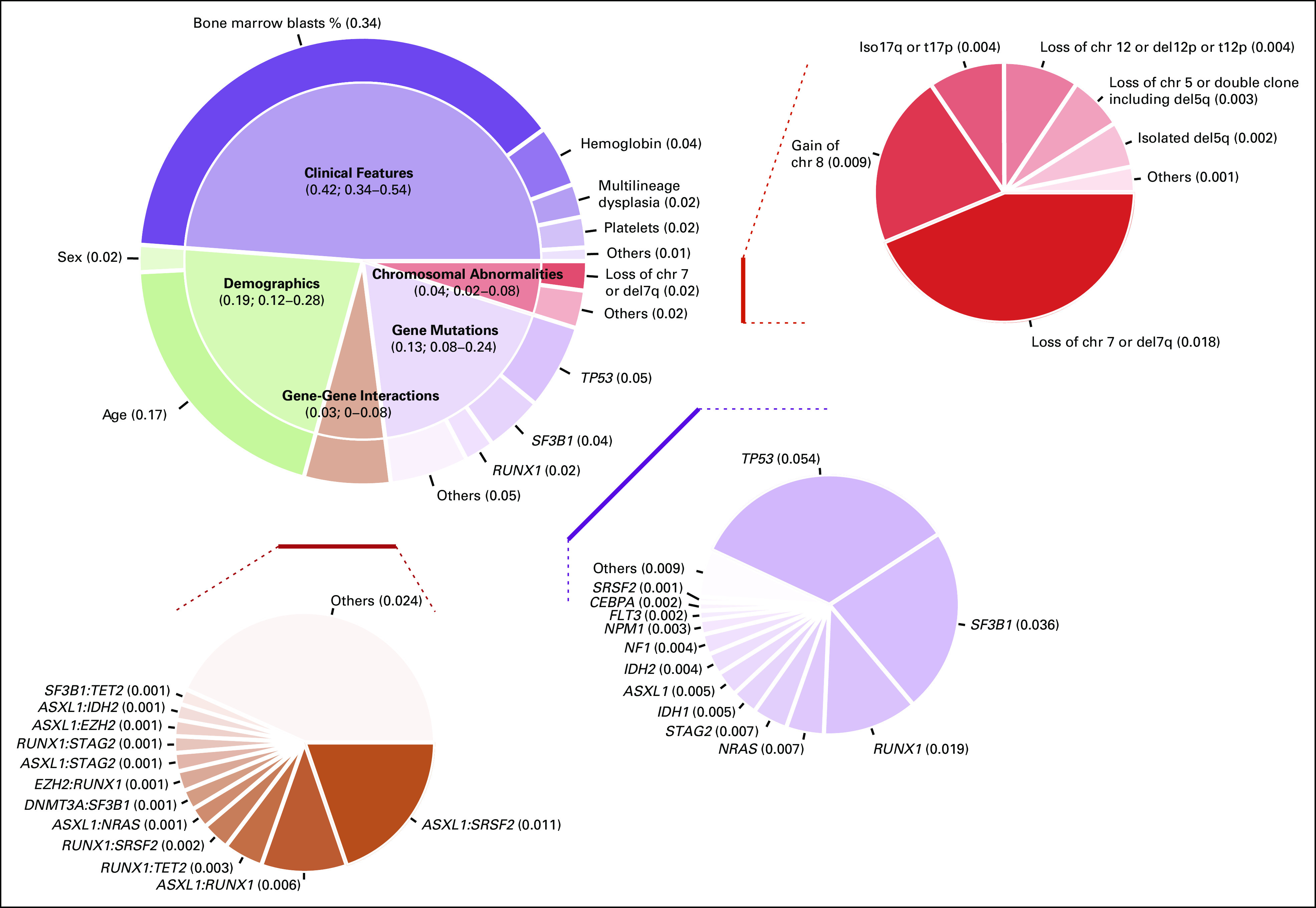

Personalized Prognostic Assessment on the Basis of Clinical and Genomic Features

Random-effects Cox multistate model incorporating 63 clinical and genomic variables are developed to estimate personalized probability of survival (Data Supplement 1).

First, we determined the fraction of explained variation for clinical outcome that was attributable to different prognostic factors (Fig 3). Demographic features (age and sex) have a high predictive prognostic power. Gene mutations and co-mutation patterns increase the prognostic power of cytogenetics. Clinical features (percentage of marrow blasts and anemia) still retain a strong independent predictive power for survival, suggesting that these variables reflect important features of the disease state that are not captured by genomic landscape (Fig 3, Data Supplement 1).

FIG 3.

Fraction of explained variation that was attributable to different prognostic factors for overall survival.

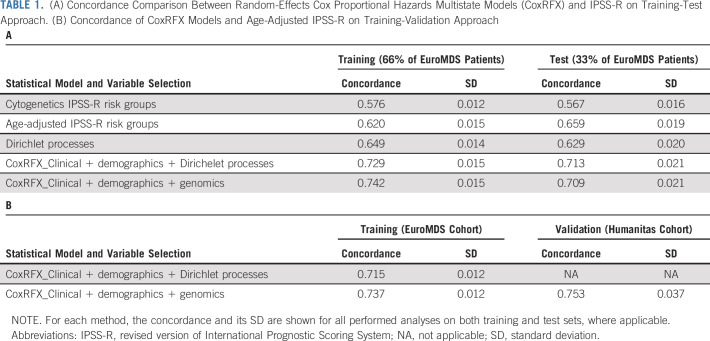

We then explored whether Random-effects Cox multistate model could generate accurate survival predictions for individual patients and if the obtained predictions are more informative than conventional age-adjusted IPSS-R (Data Supplement 1).

Random-effects Cox multistate model is able to generate a prediction for survival that correlated well with the observed outcomes in EuroMDS cohort (Table 1). Internal cross-validation shows a concordance of 0.74 and 0.71 for survival in training (67% of patients) and test (33% of patients) subsets, respectively. This model shows superior performance to conventional scoring systems (age-adjusted IPSS-R concordance is 0.62 and 0.65 in training and test subsets of EuroMDS cohort, respectively). Interestingly, the concordance of Dirichlet process components is similar to that of age-adjusted IPSS-R (0.65 and 0.62, respectively), thus underlying the relevance of accounting for genomic features into the prognostic model.

TABLE 1.

(A) Concordance Comparison Between Random-Effects Cox Proportional Hazards Multistate Models (CoxRFX) and IPSS-R on Training-Test Approach. (B) Concordance of CoxRFX Models and Age-Adjusted IPSS-R on Training-Validation Approach

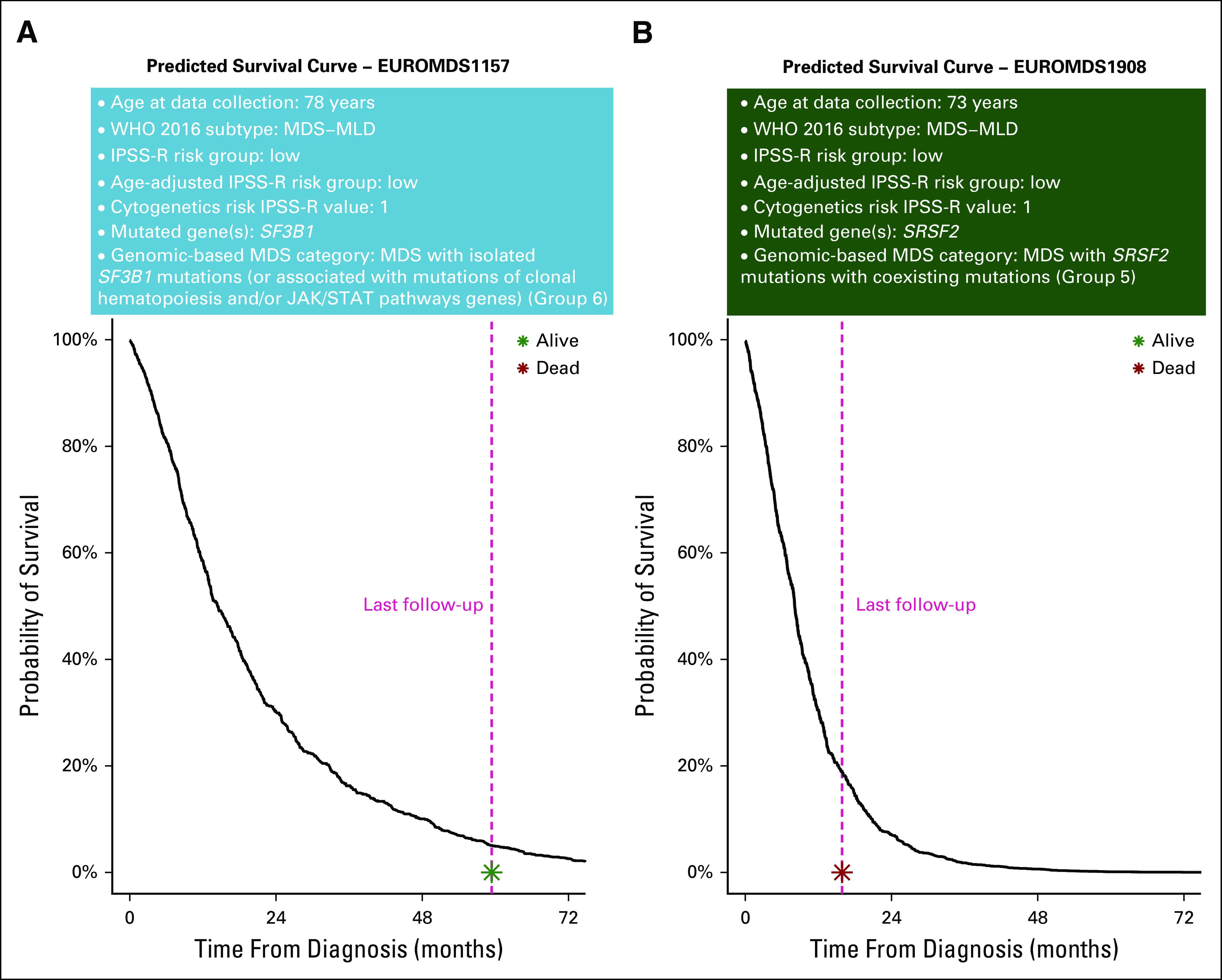

In Figure 4, we illustrate an example of the calculations to obtain a personalized prediction of survival by using patients from EuroMDS cohort; in two patients with same clinical phenotype and similar predicted prognosis according to age-adjusted IPSS-R, Random-effects Cox multistate model is able to capture additional prognostic information and efficiently predicts clinical outcome.

FIG 4.

Personalized prediction of overall survival using a multistate prognostic model including clinical and genomic features and their interactions in two patients from the EuroMDS cohort (labeled as patient A and patient B), both classified as MDS with multilineage dysplasia according to 2016 WHO classification and belonging to low-risk group according to age-adjusted revised version of International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-R). Using currently available prognostication, both patients are predicted to have an indolent clinical course without significant risk of disease evolution and death (in the EuroMDS cohort, Kaplan-Meier curves show a median survival of 79 months for low-risk age-adjusted IPSS-R). When looking at mutational profile, driver mutations involved different splicing factor genes in these patients: patient A carries SF3B1 mutation, whereas patient B presents SRSF2 mutation. We then calculated expected survival by using the novel genomic-based prognostic model (exponential survival curves are reported in the figure). Patient A was classified into genomic-based group 6, and patient B was classified into group 5. Accordingly, the estimation of life expectancy is now significantly different in these two patients, as underlined by the slope of the two exponential curves. The model predicts a better probability of survival for patient A (with SF3B1 mutation) with respect to patient B (with SRSF2 mutation), thus reflecting more precisely the observed clinical outcome. In fact, patient B died 16 months after the diagnosis as a result of leukemic evolution, whereas patient A was still alive without evidence of disease progression after 60 months of follow-up. IPSS-R fails to capture such a difference in clinical outcome. The interpretation of the predicted survival curves by genomic-based predictive model is meaningful also considering that we are in the context of a cohort of elderly patients: patient A (age 78 years) has a 30% survival probability at the age of 80, whereas patient B (age 73 years) has a 30% survival probability at the age of 74.

Because the underlying survival model is complex, specific information technology support is needed to combine all the information at individual patient level and to translate it into a personalized outcome prediction. With the aim to help clinicians to be familiar with such a next-generation prognostic tool, we have created a prototype Web portal20 that allows outcome predictions to be generated based on EuroMDS data set for user-defined constellations of genomic features and clinical variables.

Independent Validation of Personalized Prognostic Assessment

An independent validation of Random-effects Cox multistate model is performed on Humanitas cohort (a single-center prospective population of 318 patients showing significantly different hematological features with respect to EuroMDS cohort [Data Supplement 1]). Concordance for survival in Humanitas cohort was similar to that observed in EuroMDS cohort (0.75 and 0.74, respectively), suggesting that the model provides considerable discriminatory power that accurately generalizes to other real-world populations (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

We developed computational approaches to define genotype-phenotype correlations in MDS and to measure combined prognostic information of gene mutations and clinical variables.

RNA splicing is the most commonly mutated pathway in MDS10-12 and occurs early in disease evolution. These mutations play a major role in determining the disease phenotype, with differences in morphological features and survival.12 Splicing mutations may also influence the subsequent genomic evolution of the disease because the patterns of cooperating mutations are different between SF3B1, SRSF2, and U2AF1 genes.12,21 Overall, these findings suggest that a genomic classification in MDS is advisable.

We identify eight subgroups of MDS based on specific genomic features. WHO subtypes are heterogeneously distributed across these new genomic categories, suggesting that the current classification is unable to capture distinct MDS biological features.

SF3B1 mutations define a specific MDS subtype characterized by ring sideroblasts, low blast count, and favorable outcome.2,10-12,22 Among SF3B1-mutated patients, JAK/STAT pathway coexisting mutations can induce the acquisition of a myeloproliferative phenotype.23 A distinct disease subtype includes patients with SF3B1 mutations and co-existing mutations in other genes (RUNX1 and ASXL1), characterized by multilineage dysplasia.22 This disease subgroup is associated with poorer outcome. SRSF2 and U2AF1 mutations identify distinct disease subtypes with specific co-mutation patterns, hematological phenotype, and reduced probability of survival with respect to SF3B1-defined categories.24-28

The subgroup with TP53 mutations and complex karyotype has very poor outcomes29; this same subgroup has been identified in AML and myeloproliferative neoplasms.14-16 We identify an MDS subtype including cases with mutations that are recurrently described in de novo AML2,14; this category shows a very high risk of leukemic transformation and poor outcome, suggesting that the current threshold of 20% marrow blasts might be not suitable to recognize different disease entities from a biological point of view. Moreover, we notice a high percentage of patients with marrow hypocellularity in the group without specific genomic features; these MDS show overlapping clinical features with aplastic anemia.2,30 Overall, these findings suggest that a genomic classification could transcend the boundaries of MDS and help categorization of cases bordering with other myeloid conditions where current morphological criteria are often inadequate.

Moving to prognostication, we have built statistical models that can generate personally tailored survival prediction using information from both clinical and genomic features.15 We show that the inclusion of gene mutations and co-mutational patterns significantly improves patient prognostication with respect to IPSS-R, which considers only cytogenetics abnormalities. Although conventional prognostic systems provide an outcome prediction based on the median survival of patients with similar clinical features, our new prognostic model is based on individual patient genotype and phenotype, thus improving the capability of capturing prognostic information in such a heterogeneous disease. Finally, genomic features are relevant for predicting survival after transplantation, supporting the rationale to include this information to support transplantation decision making in MDS.31,32

The most critical issue for this novel prognostic model is sample size, which is particularly relevant in MDS showing a long tail of genes mutated in a low proportion of cases. According to previous data, for a gene mutated in 5%-10% of patients, a training set of 500-1,000 patients would suffice, but for a gene mutated in < 1% of patients, a cohort of > 5,000 would be needed.15 Additional cooperative efforts are therefore needed to improve the reliability and generalizability of these models.

The integration of clinical data with diagnostic genome profiling in MDS may provide prognostic predictions that are personally tailored to individual patients. Such information will empower the clinician and support complex decision-making process in these patients.

Appendix

FIG A1.

Genomic groups in EuroMDS cohort (N = 2,043) and their relationship with WHO category (defined according to 2016 classification criteria) and overall survival. According to a Bayesian clustering algorithm (Dirichlet processes), patients are classified into eight distinct genomic groups on the basis of the presence or specific mutations and/or chromosomal abnormalities: Group 0, MDS without specific genomic profile; Group 1, MDS with SF3B1 mutations and co-existing mutations in other genes (ASXL1 and RUNX1); Group 2, MDS with TP53 mutations and/or complex karyotype; Group 3, MDS with SRSF2 and concomitant TET2 mutations; Group 4, MDS with U2AF1 mutations associated with deletion of chromosome 20q and/or abnormalities of chromosome 7; Group 5, MDS with SRSF2 mutations with co-existing mutations in other genes (ASXL1, RUNX1, IDH2, and EZH2); Group 6, MDS with isolated SF3B1 mutations (or associated with mutations of TET2 and/or JAK/STAT pathways genes); Group 7, MDS with AML-like mutation patterns (DNMT3A, NPM1, FLT3, IDH1, and RUNX1 genes). These genomic MDS groups significantly differ in WHO MDS categories distribution and in cumulative probability of survival. AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; MDS-EB1, MDS with excess of blasts, type 1; MDS-EB2, MDS with excess of blasts, type 2; MDS-MLD, MDS with multilineage dysplasia; MDS-RS-MLD, MDS with ring sideroblasts and multilineage dysplasia; MDS-RS-SLD, MDS with ring sideroblasts and single-lineage dysplasia; MDS-SLD, MDS with single-lineage dysplasia; PB, peripheral blood; WHO, World Health Organization.

FIG A2.

Extrapolation of genomic landscape of MDS genomic groups through Bayesian Networks, applied to the whole MDS cohort. The size of each node accounts for the number of correspondent genomic or cytogenetic alterations. The color of each link reflects odds ratio (shades of brown represent mutual exclusivity while shades of green color degree co-occurrence). The thickness of edges grows with increasing significance of mutual exclusivity/co-occurrence between alterations. MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes.

FIG A3.

Wide-ranging genomic heterogeneity of 2016 WHO categories within MDS genomic groups. MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; MDS-EB1, MDS with excess of blasts, type 1; MDS-EB2, MDS with excess of blasts, type 2; MDS-MLD, MDS with multilineage dysplasia; MDS-RS-MLD, MDS with ring sideroblasts and multilineage dysplasia; MDS-RS-SLD, MDS with ring sideroblasts and single-lineage dysplasia; MDS-SLD, MDS with single-lineage dysplasia.

FIG A4.

Diagram to correctly classify MDS patients into the appropriate genomic group according to individual profile. AML, acute myeloid leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes.

Manja Meggendorfer

Employment: MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory

Marianna Rossi

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Celgene, IQvia, Janssen

Emanuele Angelucci

Honoraria: Celgene, Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated (MA) and CRISPR Therapeutics AG (CH)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Bluebird Bio

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen-Cilag

Massimo Bernardi

Honoraria: Celgene

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Medac, Amgen, Sanofi, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, BioTest, Abbvie, Takeda

Lorenza Borin

Leadership: Celgene

Speakers' Bureau: Genzyme

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genzyme

Benedetto Bruno

Honoraria: Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Amgen

Research Funding: Amgen

Valeria Santini

Honoraria: Celgene/Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Janssen-Cilag

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene/Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Menarini, Takeda, Pfizer

Research Funding: Celgene

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen-Cilag, Celgene

Andrea Bacigalupo

Honoraria: Pfizer, Therakos, Novartis, Sanofi, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Riemser, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Janssen-Cilag, Gilead Sciences, Kiadis Pharma, Astellas Pharma

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Kiadis Pharma, Gilead Sciences, Astellas Pharma

Speakers' Bureau: Pfizer, Therakos, Novartis, Sanofi, Riemser, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Adienne, Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Sanofi, Therakos, Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Maria Teresa Voso

Honoraria: Celgene/Jazz, Abbvie

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene/Jazz

Speakers' Bureau: Celgene

Research Funding: Celgene

Esther Oliva

Honoraria: Celgene, Novartis, Amgen, Alexion Pharmaceuticals

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Celgene, Novartis

Speakers' Bureau: Celgene, Novartis

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Royalties for QOL-E instrument

Francesco Passamonti

Speakers' Bureau: Novartis, AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals

Niccolò Bolli

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen

Speakers' Bureau: Celgene, Amgen

Alessandro Rambaldi

Honoraria: Amgen, Omeros

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Omeros, Novartis, Astellas Pharma, Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene

Wolfgang Kern

Employment: MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory

Leadership: MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory

Shahram Kordasti

Honoraria: Beckman Coulter, GWT-TUD, Alexion Pharmaceuticals

Consulting or Advisory Role: Syneos Health

Research Funding: Celgene, Novartis

Guillermo Sanz

Honoraria: Celgene

Consulting or Advisory Role: Abbvie, Celgene, Helsinn Healthcare, Janssen, Roche, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Takeda

Speakers' Bureau: Takeda

Research Funding: Celgene

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene, Takeda, Gilead Sciences, Roche Pharma AG

Armando Santoro

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Servier, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, Eisai, Bayer AG, MSD, Sanofi, ArQule

Speakers' Bureau: Takeda, Roche, Abbvie, Amgen, Celgene, AstraZeneca, ArQule, Lilly, Sandoz, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Servier, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, Eisai, Bayer AG, MSD

Uwe Platzbecker

Honoraria: Celgene/Jazz

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene/Jazz

Research Funding: Amgen, Janssen, Novartis, BerGenBio, Celgene

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: part of a patent for a TFR-2 antibody (Rauner et al. Nature Metabolics 2019)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene

Pierre Fenaux

Honoraria: Celgene

Research Funding: Celgene

Torsten Haferlach

Employment: MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory

Leadership: MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory

Consulting or Advisory Role: Illumina

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

Supported by: European Union (Transcan_7_Horizon 2020—EuroMDS project #20180424 to M.G.D.P., F.S., U.P., and P.F.); AIRC Foundation (Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca contro il Cancro, Milan Italy—Project # 22053 to M.G.D.P.); PRIN 2017 (Ministry of University & Research, Italy—Project 2017WXR7ZT to M.G.D.P.); Ricerca Finalizzata 2016 (Italian Ministry of Health, Italy—Project RF2016-02364918 to M.G.D.P.); Cariplo Foundation (Milan Italy—Project # 2016-0860 to M.G.D.P.); H2020 European Union (HARMONY project # 116026 to G.C.) and H2020-MSCA-ITN (IMforFUTURE project # 721815 to G.C.).

M.B. and E.T. equal contribution as first authors; G.C. and M.G.D.P. equal contribution as last senior authors.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

According to data sharing guidelines for the Journal of Clinical Oncology, with the aim to help clinicians to be familiar with proposed next-generation prognostic tool, we provide public access to a web portal that allows outcome predictions to be generated based on EuroMDS data set for user-defined constellations of genomic features and clinical variables.20

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Matteo Bersanelli, Erica Travaglino, Marianna Rossi, Emanuele Angelucci, Francesco Passamonti, Fabio Ciceri, Wolfgang Kern, Shahram Kordasti, Francesc Sole, Armando Santoro, Uwe Platzbecker, Pierre Fenaux, Matteo G. Della Porta

Financial support: Gastone Castellani

Administrative support: Uwe Platzbecker, Torsten Haferlach

Provision of study materials or patients: Matteo Gnocchi, Emanuele Angelucci, Massimo Bernardi, Lorenza Borin, Benedetto Bruno, Francesca Bonifazi, Valeria Santini, Andrea Bacigalupo, Maria Teresa Voso, Esther Oliva, Marta Riva, Francesco Passamonti, Fabio Ciceri, Niccolò Bolli, Alessandro Rambaldi, Francesc Sole, Armando Santoro, Uwe Platzbecker, Luciano Milanesi, Torsten Haferlach, Matteo G. Della Porta

Collection and assembly of data: Matteo Bersanelli, Erica Travaglino, Manja Meggendorfer, Chiara Chiereghin, Giulia Maggioni, Emanuele Angelucci, Massimo Bernardi, Lorenza Borin, Benedetto Bruno, Francesca Bonifazi, Valeria Santini, Maria Teresa Voso, Esther Oliva, Marta Riva, Marta Ubezio, Lucio Morabito, Alessia Campagna, Claudia Saitta, Alessandro Rambaldi, Wolfgang Kern, Laura Palomo, Guillermo Sanz, Uwe Platzbecker, Torsten Haferlach, Matteo G. Della Porta

Data analysis and interpretation: Matteo Bersanelli, Erica Travaglino, Tommaso Matteuzzi, Claudia Sala, Ettore Mosca, Noemi Di Nanni, Matteo Gnocchi, Matteo Zampini, Alberto Termanini, Emanuele Angelucci, Lorenza Borin, Benedetto Bruno, Valeria Santini, Andrea Bacigalupo, Lucio Morabito, Alessia Campagna, Claudia Saitta, Victor Savevski, Enrico Giampieri, Daniel Remondini, Francesco Passamonti, Fabio Ciceri, Niccolò Bolli, Wolfgang Kern, Shahram Kordasti, Francesc Sole, Guillermo Sanz, Armando Santoro, Uwe Platzbecker, Pierre Fenaux, Luciano Milanesi, Gastone Castellani, Matteo G. Della Porta

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Classification and Personalized Prognostic Assessment on the Basis of Clinical and Genomic Features in Myelodysplastic Syndromes

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Manja Meggendorfer

Employment: MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory

Marianna Rossi

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Celgene, IQvia, Janssen

Emanuele Angelucci

Honoraria: Celgene, Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated (MA) and CRISPR Therapeutics AG (CH)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Bluebird Bio

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen-Cilag

Massimo Bernardi

Honoraria: Celgene

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Medac, Amgen, Sanofi, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, BioTest, Abbvie, Takeda

Lorenza Borin

Leadership: Celgene

Speakers' Bureau: Genzyme

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genzyme

Benedetto Bruno

Honoraria: Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Amgen

Research Funding: Amgen

Valeria Santini

Honoraria: Celgene/Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Janssen-Cilag

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene/Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Menarini, Takeda, Pfizer

Research Funding: Celgene

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen-Cilag, Celgene

Andrea Bacigalupo

Honoraria: Pfizer, Therakos, Novartis, Sanofi, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Riemser, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Janssen-Cilag, Gilead Sciences, Kiadis Pharma, Astellas Pharma

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Kiadis Pharma, Gilead Sciences, Astellas Pharma

Speakers' Bureau: Pfizer, Therakos, Novartis, Sanofi, Riemser, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Adienne, Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Sanofi, Therakos, Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Maria Teresa Voso

Honoraria: Celgene/Jazz, Abbvie

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene/Jazz

Speakers' Bureau: Celgene

Research Funding: Celgene

Esther Oliva

Honoraria: Celgene, Novartis, Amgen, Alexion Pharmaceuticals

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Celgene, Novartis

Speakers' Bureau: Celgene, Novartis

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Royalties for QOL-E instrument

Francesco Passamonti

Speakers' Bureau: Novartis, AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals

Niccolò Bolli

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen

Speakers' Bureau: Celgene, Amgen

Alessandro Rambaldi

Honoraria: Amgen, Omeros

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Omeros, Novartis, Astellas Pharma, Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene

Wolfgang Kern

Employment: MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory

Leadership: MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory

Shahram Kordasti

Honoraria: Beckman Coulter, GWT-TUD, Alexion Pharmaceuticals

Consulting or Advisory Role: Syneos Health

Research Funding: Celgene, Novartis

Guillermo Sanz

Honoraria: Celgene

Consulting or Advisory Role: Abbvie, Celgene, Helsinn Healthcare, Janssen, Roche, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Takeda

Speakers' Bureau: Takeda

Research Funding: Celgene

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene, Takeda, Gilead Sciences, Roche Pharma AG

Armando Santoro

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Servier, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, Eisai, Bayer AG, MSD, Sanofi, ArQule

Speakers' Bureau: Takeda, Roche, Abbvie, Amgen, Celgene, AstraZeneca, ArQule, Lilly, Sandoz, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Servier, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, Eisai, Bayer AG, MSD

Uwe Platzbecker

Honoraria: Celgene/Jazz

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene/Jazz

Research Funding: Amgen, Janssen, Novartis, BerGenBio, Celgene

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: part of a patent for a TFR-2 antibody (Rauner et al. Nature Metabolics 2019)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene

Pierre Fenaux

Honoraria: Celgene

Research Funding: Celgene

Torsten Haferlach

Employment: MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory

Leadership: MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory

Consulting or Advisory Role: Illumina

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adès L, Itzykson R, Fenaux P: Myelodysplastic syndromes. Lancet 383:2239-2252, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arber DA Orazi A Hasserjian R, et al. : The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 127:2391-2405, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Della Porta MG Travaglino E Boveri E, et al. : Minimal morphological criteria for defining bone marrow dysplasia: A basis for clinical implementation of WHO classification of myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia 29:66-75, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Senent L Arenillas L Luno E, et al. : Reproducibility of the World Health Organization 2008 criteria for myelodysplastic syndromes. Haematologica 98:568-575, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malcovati L Della Porta MG Pascutto C, et al. : Prognostic factors and life expectancy in myelodysplastic syndromes classified according to WHO criteria: A basis for clinical decision making. J Clin Oncol 23:7594-7603, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malcovati L Hellström-Lindberg E Bowen D, et al. : Diagnosis and treatment of primary myelodysplastic syndromes in adults: Recommendations from the European LeukemiaNet. Blood 122:2943-2964, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenberg PL Tuechler H Schanz J, et al. : Revised international prognostic scoring system for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 120:2454-2465, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Della Porta MG Tuechler H Malcovati L, et al. : Validation of WHO classification-based prognostic scoring system (WPSS) for myelodysplastic syndromes and comparison with the revised International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-R). A study of the International Working Group for prognosis in myelodysplasia. Leukemia 29:1502-1513, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cazzola M, Della Porta MG, Malcovati L: The genetic basis of myelodysplasia and its clinical relevance. Blood 122:4021-4034, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papaemmanuil E Cazzola M Boultwood J, et al. : Somatic SF3B1 mutation in myelodysplasia with ring sideroblasts. N Engl J Med 365:1384-1395, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshida K Sanada M Shiraishi Y, et al. : Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature 478:64-69, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papaemmanuil E Gerstung M Malcovati L, et al. : Clinical and biological implications of driver mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 122:3616-3627, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schanz J Tüchler H Solé F, et al. : New comprehensive cytogenetic scoring system for primary myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia after MDS derived from an international database merge. J Clin Oncol 30:820-829, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papaemmanuil E Gerstung M Bullinger L, et al. : Genomic classification and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 374:2209-2221, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerstung M Papaemmanuil E Martincorena I, et al. : Precision oncology for acute myeloid leukemia using a knowledge bank approach. Nat Genet 49:332-340, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grinfeld J Nangalia J Baxter EJ, et al. : Classification and personalized prognosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med 379:1416-1430, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grinfeld J Nangalia J Baxter EJ, et al. R package for Hierarchical Dirichlet Process. https://github.com/nicolaroberts/hdp

- 18.Harrell FE, Lee KL, Mark DB: Multivariable prognostic models: Issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 15:361-387, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perperoglou A: Cox models with dynamic ridge penalties on time-varying effects of the covariates Stat Med 33:170-180, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grinfeld J Nangalia J Baxter EJ, et al. EUROMDS Project: Personalized prediction of clinical outcome in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome according to genomic and clinical features. https://mds.itb.cnr.it/#/mds

- 21.Pellagatti A Armstrong RN Steeples V, et al. : Impact of spliceosome mutations on RNA splicing in myelodysplasia: Dysregulated genes/pathways and clinical associations. Blood 132:1225-1240, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malcovati L Papaemmanuil E Bowen DT, et al. : Clinical significance of SF3B1 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes and myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood 118:6239-6246, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klampfl T Gisslinger H Harutyunyan AS, et al. : Somatic mutations of calreticulin in myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med 369:2379-2390, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reilly B Tanaka TN Diep D, et al. : DNA methylation identifies genetically and prognostically distinct subtypes of myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood Adv 3:2845-2858, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masaki S Ikeda S Hata A, et al. : Myelodysplastic syndrome-associated SRSF2 mutations cause splicing changes by altering binding motif sequences. Front Genet 10:338, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang Y Tebaldi T Rejeski K, et al. : SRSF2 mutations drive oncogenesis by activating a global program of aberrant alternative splicing in hematopoietic cells. Leukemia 32:2659-2671, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haferlach T Nagata Y Grossmann V, et al. : Landscape of genetic lesions in 944 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia 28:241-247, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bacher U Haferlach T Schnittger S, et al. : Investigation of 305 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and 20q deletion for associated cytogenetic and molecular genetic lesions and their prognostic impact. Br J Haematol 164:822-833, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haase D Stevenson KE Neuberg D, et al. : TP53 mutation status divides myelodysplastic syndromes with complex karyotypes into distinct prognostic subgroups. Leukemia 33:1747-1758, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kulasekararaj AG Jiang J Smith AE, et al. : Somatic mutations identify a subgroup of aplastic anemia patients who progress to myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood 124:2698-2704, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Della Porta MG Gallì A Bacigalupo A, et al. : Clinical effects of driver somatic mutations on the outcomes of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes treated with allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 34:3627-3637, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindsley RC Saber W Mar BG, et al. : Prognostic mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome after stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 376:536-547, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

According to data sharing guidelines for the Journal of Clinical Oncology, with the aim to help clinicians to be familiar with proposed next-generation prognostic tool, we provide public access to a web portal that allows outcome predictions to be generated based on EuroMDS data set for user-defined constellations of genomic features and clinical variables.20