Abstract

Background

Individually, randomised trials have not shown conclusively whether adjuvant chemotherapy benefits adult patients with localised resectable soft‐tissue sarcoma.

Objectives

Adjuvant chemotherapy aims to lessen the recurrence of cancer after surgery with or without radiotherapy. The objective of this review was to assess the effects of adjuvant chemotherapy in adults with resectable soft tissue sarcoma after such local treatment.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, UKCCCR Register of Cancer Trials, Physicians Data Query, EMBASE, MEDLINE and CancerLit.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials of adjuvant chemotherapy after local treatment in adults with localised resectable soft tissue sarcoma were included. Only trials in which accrual was completed by December 1992 were included.

Data collection and analysis

Individual patient data were obtained. Accuracy of data and quality of randomisation and follow‐up of trials was assessed.

Main results

Fourteen trials of doxorubicin‐based adjuvant chemotherapy involving 1568 patients were included. Median follow‐up was 9.4 years. For local recurrence‐free interval the hazard ratio (HR) with chemotherapy was 0.73 (95% Confidence Interval (CI) 0.56 to 0.94). For distant recurrence‐free interval it was 0.70 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.85). For overall recurrence‐free survival it was 0.75 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.87). These correspond to significant absolute benefits of 6 to 10% at 10 years. For overall survival (OS) the HR of 0.89 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.03) was not significant but potentially represents an absolute benefit of 4% (95% CI 1 to 9) at 10 years. There was no consistent evidence of a difference in effect according to age, sex, stage, site, grade, histology, extent of resection, tumour size or exposure to radiotherapy. However, the strongest evidence of a beneficial effect on survival was shown in patients with sarcoma of the extremities.

Authors' conclusions

Doxorubicin‐based adjuvant chemotherapy appears to significantly improve time to local and distant recurrence and overall recurrence‐free survival in adults with localised resectable soft tissue sarcoma. There is some evidence of a trend towards improved overall survival.

Plain language summary

Doxorubicin after initial treatment for sarcoma reduces risk of recurrence

Usually at diagnosis sarcoma shows no sign of having spread outside the original site and treatment is surgery (with/without radiotherapy). In about half the patients the cancer recurs. There is evidence that doxorubicin‐based chemotherapy after initial treatment reduces recurrence, either at the original site or elsewhere in the body. Chemotherapy also seems to increase the length of time patients live, but this is less certain.Greater benefit was seen in men and those whose tumour originated in a limb, but these results may have occurred by chance.

Background

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare and complex tumours of mesenchymal origin. Although most patients present with apparently localised disease, which allows good local control, about 50% die from subsequent metastases (Delaney 1991). The reported activity of doxorubicin in this disorder (Blum 1974, Benjamin 1975, Gottlieb 1975) has led to much research on the use of doxorubicin‐based adjuvant chemotherapy. However, because of difficulties in accruing patients, few trials have been large enough to detect moderate treatment effects reliably and most have had equivocal results. Many qualitative reviews of trial publications (e.g., recently McGrath 1995, Mertens 1995) have failed to synthesise these results reliably. Three meta‐analyses of the published literature, one of which was restricted to sarcomas of the extremities (Zalupski 1993), have suggested that adjuvant chemotherapy may prolong the local recurrence‐free interval (local RFI) and distant recurrence‐free interval (distant RFI) (Jones 1994), recurrence‐free survival (Zalupski 1993, Jones 1994) and overall survival (Zalupski 1993, Jones 1994, Tierney 1995). However, such analyses, based on results extracted from the published reports are subject to several potential biases such as exclusion of unpublished trials, variable follow‐up, post‐randomisation exclusions and differing definitions of endpoints (Tierney 1995).

The most reliable way to assess the available evidence and establish the size of any effect of adjuvant chemotherapy is to collect individual data for all patients randomised, in all eligible trials, and to combine the results of these trials in an appropriate intention‐to‐treat analysis. This approach is the best for time‐to‐event analyses. Follow‐up can be brought up to date and more flexible and detailed analyses, including subgroup analyses are possible. Such a meta‐analysis was therefore initiated by the UK Medical Research Council Cancer Trials Office, Cambridge, in collaboration with the University College London Medical School (London), the Institut Curie (Paris), the Hamilton Regional Cancer Centre (Ontario), and the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC; Brussels). This meta‐analysis was conducted on behalf of the Sarcoma Meta‐analysis Collaboration (SMAC). Data was collated, checked and analysed by the MRC CTO. The collaborative group met in December 1995 to discuss preliminary results. This review was first published by SMAC in the Lancet (SMAC 1997) and is reproduced with their permission.

Objectives

Primarily, this meta‐analysis aimed to assess whether adjuvant chemotherapy improves survival of patients with localised soft tissue sarcoma and to quantify any effect of chemotherapy on the appearance of local and distant disease. It aimed also to investigate whether certain patient groups benefit more, or less, from chemotherapy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Trials (published and unpublished) were eligible for inclusion provided they randomised patients with localised resectable soft tissue sarcoma to receive either adjuvant chemotherapy or no chemotherapy following local treatment. The randomisation method should have precluded prior knowledge of the treatment assignment and accrual should have been completed by December 1992.

Types of participants

Adult patients with localised resectable soft tissue sarcoma. Individual data from all randomised patients were included in the meta‐analysis. Where possible data were obtained for individuals who had been excluded from the original trial analyses. These individuals were included in the meta‐analysis.

Types of interventions

Trials that compared either adjuvant chemotherapy or no chemotherapy following local treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Survival, local and distant recurrence‐free intervals and recurrence‐free survival.

Search methods for identification of studies

Trials were identified by searches of MEDLINE and CancerLit, with the optimal search strategy developed by the Cochrane Collaboration (Dickersin 1995) and EMBASE, and also by examination of the reference lists of trial publications, review articles and books. Trial investigators collaborating in the meta‐analysis and trial registers (United Kingdom Committee on Cancer Research Register of Clinical Trials and Physicians Data Query Clinical Protocols) were also consulted to help identify unpublished trials. Searches were updated to October 1999 to identify new trials and the status of ongoing trials.

Data collection and analysis

The methods used were prespecified in a protocol available from the corresponding author on request.

Data was sought for all patients randomised in all eligible randomised trials (published or unpublished) and updated follow‐up requested. The updated data requested were: date of birth or age, sex, disease status at randomisation, disease site, histology, grade, tumour size, primary treatment, allocated treatment, extent of resection, date of randomisation, survival status, cause of death, date of death or last follow‐up, local recurrence status, date of local recurrence, distant recurrence status and date of distant recurrence. All data received were checked thoroughly to ensure both the accuracy of the meta‐analysis database and the quality of randomisation and follow‐up. Any queries were resolved and the final database entries verified by the responsible trial investigator or statistician.

Local recurrence‐free and distant recurrence‐free intervals were defined as the time from randomisation until first local or distant recurrence. Patients without recurrence by the time of last follow‐up were censored on that date and patients who died without recurrence were censored on the date of death. Patients who had a local recurrence were not censored in the analysis of distant recurrence or vice versa (except for two trials where only the first recurrence was recorded), because local recurrence did not seem to preclude the possibility of later distant recurrence and vice versa. Recurrence‐free survival was taken as the time from randomisation until any recurrence or death (by any cause), whichever happened first. Patients alive without recurrence were censored on the date of last follow‐up. Overall survival was defined as the time from randomisation until death (by any cause). Surviving patients and those lost to follow‐up were censored on the date of last follow‐up. In each case, unless otherwise specified by the investigators, the date of last follow‐up was taken to refer to both disease status and survival status.

Survival analyses were stratified by trial and the log‐rank‐expected number of events and variance were used to calculate the hazard ratios for individual trials and combined across all trials by the fixed‐effects model (Yusuf 1985). Thus, the time‐to‐event for individual patients was used within trials to calculate hazard ratios, representing the overall risk of death or recurrence on adjuvant chemotherapy as compared to control. Within pre‐specified subgroups of patients, similar stratified analyses were done for all endpoints except local recurrence‐free interval, for which there were too few events for any meaningful analyses to be done. As defined above, some patients were excluded from the main analyses. All other randomised patients were included in the main analyses, which were carried out on intention to treat. The impact of patient exclusions were explored by sensitivity analyses. Simple (non‐stratified) Kaplan‐Meier curves were generated (Kaplan 1958). These are not currently reproducible in the Cochrane Library but can be found in the meta‐analysis publication. Control group baseline probabilities for each endpoint, derived from these curves at 10 years, together with overall hazard ratios, were used to calculate the absolute effects of treatment (Freedman 1982).

Chi‐square tests for heterogeneity were used to test for gross statistical heterogeneity over all trials (chi‐square tests for heterogeneity) and the consistency of effect across different subsets of trials and across different subgroups of patients (chi‐square tests for interaction). These tests are aimed primarily at detecting quantitative differences (differences in size rather than direction), because there was no a‐priori reason to expect qualitative differences. Where subgroups had a natural order the chi‐square test for trend was used. In all tests of significance the two‐sided p‐value is given.

Results

Description of studies

Of 23 potentially eligible trials, four were excluded because they were not adjuvant studies (Schoenfeld 1982, Pinedo 1988, Baker 1987), one because all patients received preoperative intra‐arterial induction chemotherapy before randomisation (Eilber 1988) and one because the patients were deemed non‐resectable (EST‐3782). Three further trials were not eligible: one because it is still accruing patients (EORTC 62931); and two because they closed after the December, 1992 cut‐off for inclusion in first cycle of analyses (Frustaci 1987, NCI‐92‐C‐0210). It is unlikely at this stage that inclusion of the relatively immature results of the Italian trial (Frustaci 1987) and the small number of patients from the American trial (NCI‐92‐C‐0210) will impact on the results and conclusions of the review and so an update of the analysis is not planned until the EORTC study has closed (EORTC 62931). Data could not be obtained for two published studies (Kinsella 1988, Piver 1988) and one unpublished study (SWOG‐8791) accounting for a total of 31 patients. The meta‐analysis is therefore based on 14 trials (13 published, one unpublished) including 1568 patients (Table of included studies). This total represents 98% of patients from known, eligible and completed randomised trials. Follow‐up for most trials was updated giving a median of 9.4 years (median for individual trials of 4.9 to 17.6 years).

All identified trials used chemotherapy with doxorubicin alone or in combination with other drugs. Total planned doses ranged from 200mg/m2 to 550mg/m2 with a dose per cycle of 50 to 90mg/m2. The patients reflect the eligibility criteria of these individual trials, although it should be noted that some were excluded from the main analyses.

All treatment comparisons were between patients assigned local treatment plus adjuvant chemotherapy and patients assigned local treatment only (controls). Local treatment was surgery with or without radiotherapy.

Risk of bias in included studies

Only properly randomised trials were included, where the randomisation method precluded prior knowledge of the treatment assignment and accrual was completed by December 1992. All data received were checked thoroughly to ensure both the accuracy of the meta‐analysis database and the quality of randomisation and follow‐up. Any queries were resolved and the final database entries verified by the responsible trial investigator or statistician.

Effects of interventions

Effects of adjuvant chemotherapy

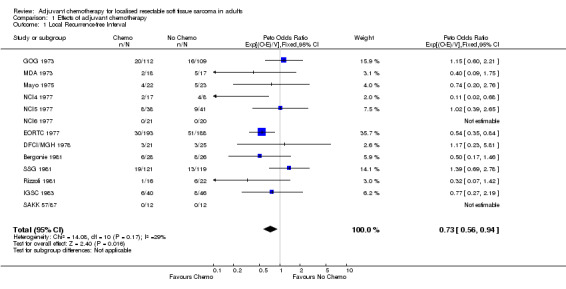

Local recurrence‐free interval

Data from 13 trials on 1315 patients and 229 local recurrences were included in this analysis. One trial (ECOG 1978) recorded recurrence but did not distinguish between local and distant recurrence; it could not therefore, be included in analyses of local and distant RFI. The results for individual trials had wide confidence intervals and were inconclusive but, for the results combined, the overall hazard ratio was significantly in favour of chemotherapy (chi‐square = 5.78, df = 1, p = 0.016). There was no clear evidence of heterogeneity in the effect of chemotherapy between trials (chi‐square = 14.06, df = 10, p = 0.17). The overall hazard ratio of 0.73 (95% Confidence IntervaI 0.56‐0.94) represents a 27% reduction in the risk of local recurrence and translates into an absolute benefit of 6% (95% CI 1‐10) at 10 years, with the local recurrence‐free interval improved from 75% to 81%. Most local recurrences took place in the first four years after randomisation.

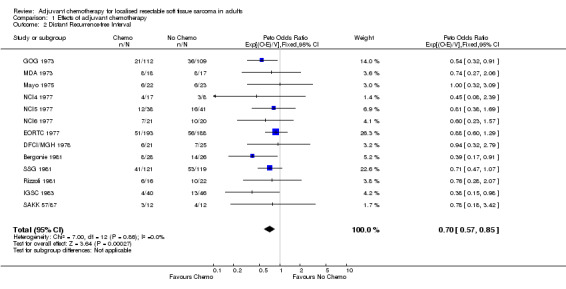

Distant recurrence‐free interval

Data from 13 trials on 1315 patients and 413 distant recurrences were included in this analysis. All individual trial estimates favoured chemotherapy, but CIs were wide. Three reached conventional levels of significance (p < 0.05), but none was significant at p < 0.01. The combined results gave a highly significant overall benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy (chi‐square = 13.23, df = 1, p = 0.0003) with little evidence of statistical heterogeneity (chi‐square = 7.00, df = 12, p = 0.86). The overall hazard ratio of 0.70 (95% CI 0.57‐0.85) or 30% reduction in the risk of metastases, suggests an absolute benefit of 10% (95% CI 5‐15) at 10 years, with distant recurrence‐free interval improved from 60% to 70%.

Overall recurrence‐free survival

Data were available for all 14 trials; 1366 patients and 707 recurrences or deaths were included in this analysis. The overall hazard ratio of 0.75 (95% CI 0.64‐0.87) was strongly in favour of adjuvant chemotherapy (chi‐square = 14.59, df = 1, p = 0.0001) with little evidence of statistical heterogeneity between trials (chi‐square = 9.26, df = 13, p = 0.75), equivalent to a 25% reduction in the risk of recurrence or death. The absolute improvement is 10% at 10 years (95% CI 5‐15), such that overall recurrence‐free survival would be improved from 45‐55%.

Overall survival

For the primary endpoint of overall survival, data were available for all 14 trials, and 1544 patients and 691 deaths were included. The trend for overall survival was in favour of chemotherapy with a hazard ratio of 0.89 (95% CI 0.76‐1.03), but it was not significant (chi‐square = 2.41, df = 1, p = 0.12). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity across trials (chi‐square = 11.8, df = 13, p = 0.54), nor any evidence that the result was influenced by whether the trials used doxorubicin singly or in combination with other drugs (interaction chi‐square = 0.17, df = 1, p = 0.68). The results were similar in an analysis of death from soft tissue sarcoma only for the 10 trials that gave cause of death (hazard ratio = 0.88, chi‐square = 1.72, df = 1, p = 0.19). The potential absolute benefit was 4% (95% CI ‐1 to 9%) at 10 years, representing a possible survival improvement from 50% to 54%.

For local recurrence‐free interval, distant recurrence‐free interval, overall recurrence‐free survival and survival, the results were not affected by the inclusion or exclusion of various groups of patients, despite some large changes in the number of events.

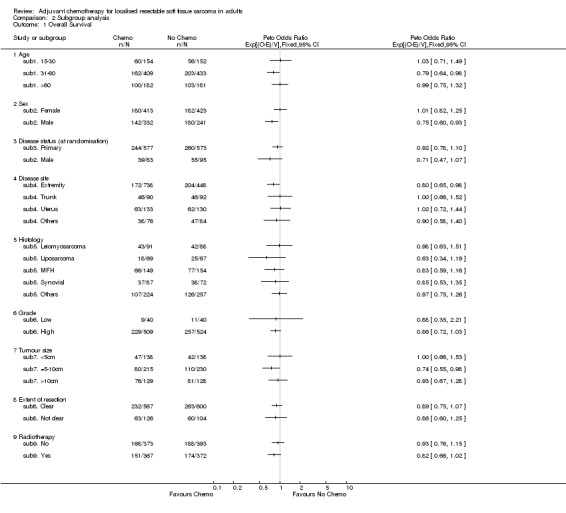

Subgroup analyses

Although data for most variables were available for more than 90% of patients, fewer data were available for histology (82%, of which 59% had undergone review), grade (72%, of which 25% had undergone review) and tumour size (63%).

For overall survival, there was no clear evidence to suggest that any subgroup benefited more or less from adjuvant chemotherapy (Age class:interaction chi‐square=2.32, df = 2, p = 0.31; trend chi‐square = 0.02, df = 2, p = 0.88; disease status at randomisation: interaction chi‐square = 1.36, df = 1, p = 0.24; disease site: interaction chi‐square = 1.96, df = 3, p = 0.58; histology: interaction chi‐square = 1.91, df = 4, p = 0.75; grade: interaction chi‐square = 0.001, df = 1, p = 0.97, tumour size class: interaction chi‐square = 1.81, df = 2, p = 0.40, trend chi‐square = 0.002, df = 1, p = 0.96; extent of resection: interaction chi‐square = 0.02, df = 1, p = 0.88 and radiotherapy: interaction chi‐square = 0.71, df = 1, p = 0.40). There was some suggestion that men benefited more than women from chemotherapy (interaction chi‐square = 3.86, df = 1, p = 0.049).

Among patients with lesions of the extremities (376 deaths and 886 patients) the hazard ratio was 0.80 (p = 0.029), equivalent to a 7% absolute benefit at 10 years. This group had the clearest evidence of a treatment effect on survival. The wide confidence intervals for the other sites reflects the small numbers, and there was no clear evidence that the results are different from those for extremity sarcomas (p = 0.58).

The effect of chemotherapy was greater for both distant recurrence‐free interval and overall recurrence‐free survival than for overall survival and so there may be a greater possibility of detecting differences between subgroups; there was, however, no evidence of a differential effect of chemotherapy in any of the subgroups defined above.

Owing to clinical interest, additional subgroup analyses were specified a posteriori to examine whether there was a differential effect of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with large, high grade tumours of the extremity compared to others and also across patients defined by tumour size greater or less than 8cm. However, less data were available for these definitions (60% and 56% respectively) and for both overall survival and overall recurrence‐free survival the relative effect of chemotherapy was similar.

Figures and results not shown are available from the corresponding author on request.

Discussion

This meta‐analysis provides the most reliable, up‐to‐date and comprehensive summary of the average effect of adjuvant chemotherapy for localised soft tissue sarcoma.

We found good evidence that adjuvant doxorubicin‐based chemotherapy improves the time to local and distant recurrence and overall‐recurrence‐free survival with a trend toward improved overall survival. In each case, estimates of the effect of adjuvant chemotherapy were not affected by the exclusion of sometimes quite large numbers of patients. Furthermore, the effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on overall survival was not affected by whether doxorubicin was given alone or in combination with other drugs or by whether deaths from all causes or only soft‐tissue sarcoma deaths were considered.

Several hypotheses could explain why the impact of adjuvant chemotherapy appears less for overall survival than for other endpoints. On relapse, patients may receive effective salvage therapy that improves survival. Where relapse is treated by local therapy, in particular thoracotomy for lung metastases, differences in rates of recurrence on treatment and control could affect our estimates. When this is modelled on the assumption that thoracotomy is offered equally and is effective on both groups, then the impact on estimates of survival are minimal (details available on request). By contrast, the use of chemotherapy on relapse is probably more common and perhaps more effective in the control arm (since tumours previously exposed to adjuvant chemotherapy may be drug resistant) and survival for relapsed patients would therefore be proportionately greater. Therefore, as for many adjuvant trials, the comparison becomes one of immediate versus deferred chemotherapy. Another possibility, is that adjuvant chemotherapy genuinely has no effect on overall survival (either as adjuvant or second line treatment), but does have an effect on recurrence of local and distant disease. Alternatively, adverse effects of adjuvant chemotherapy on overall survival could mask underlying survival benefits. However, when only sarcoma deaths were analysed, thus excluding serious late and early toxic effects associated with doxorubicin, the estimate of treatment effect was similar to the main results, suggesting that this hypothesis is not correct.

The analyses did not provide consistent evidence that the relative effect of adjuvant chemotherapy was smaller or larger for any particular type of patient. There was some suggestion that men might benefit more than women. Also, the clearest evidence and the largest observed effect was in patients with extremity lesions. This does not necessarily mean it is less effective in other sites, for which there were substantially fewer patients. However, the results of subgroup analyses must always be interpreted cautiously (Collins 1987), especially when multiple analyses have been done and the overall result shows no significant difference, or data is limited, as in these analyses. Nevertheless, the prognoses for different tumour types varies considerably, such that the same relative effect of chemotherapy can have a different absolute effect and perhaps a different clinical interpretation. At 10 years, baseline survival ranged from 35% to 80% and baseline recurrence‐free survival from 35% to 75% across the various subgroups. Thus, the hazard ratios of 0.89 for survival and 0.75 for recurrence‐free survival are equivalent to absolute potential benefits from adjuvant chemotherapy of between 2 and 4% and 6 and 11% respectively.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Although this meta‐analysis can provide only average estimates of the effect of adjuvant chemotherapy for localised resectable soft tissue sarcoma, it is probably the best evidence on which to base treatment policy. Overall, the analyses suggest that immediate doxorubicin‐based chemotherapy can lengthen the time alive without recurrence, and there is a trend toward improved survival. However, the analyses cannot provide any guidance with respect to particular drug regimens and doses. Although the trials included in the meta‐analysis did not collect data on patient‐reported quality‐of‐life measures, doxorubicin toxicity was reported. Common acute effects were leucopenia, alopecia, nausea and vomiting, sometimes leading to lack of compliance or reduction in doxorubicin dose. Serious cardiac complications associated with doxorubicin were observed in some trials, but cardiotoxic death was relatively uncommon. Furthermore, such deaths will have been accounted for in our analyses, which included deaths by all causes.

There was little evidence that certain types of patients benefited more or less from adjuvant chemotherapy. However, soft‐tissue sarcomas are a heterogeneous group, affecting a broad patient population and their underlying prognoses will assist both clinicians and patients in assessing whether the net benefit of treatment is clinically worthwhile, particularly in the light of doxorubicin toxicity.

Implications for research.

Further follow‐up, particularly of the later trials and inclusion of current randomised trials of adjuvant chemotherapy, will add to the evidence in future updates of this meta‐analysis.

The rarity and complexity of soft tissue sarcomas has meant that accrual of sufficient numbers of patients into trials has been, and continues to be, difficult. Our results may convince some researchers that future trials should contain a doxorubicin‐based chemotherapy control arm. Others may consider that an overall survival advantage of doxorubicin‐based chemotherapy is still in question (except perhaps for extremity sarcomas). In either case, future randomised trials must be larger than those undertaken previously, if they are to reliably detect treatment effects of moderate size ‐ generally the best that can be expected from new treatments. For example, to detect differences of around 10% in overall survival or recurrence‐free survival would require around 900 patients. This is clearly not possible without large‐scale collaboration between research groups and preferential entry of patients into sarcoma trials.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 February 2015 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 22 February 2011 | Review declared as stable | IPD data |

History

Review first published: Issue 1, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 March 2014 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 19 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 3 July 2000 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Notes

This review was converted from an Individual Patient Data review originally intended for paper publication. It will, therefore, be updated as per the schedule of the IPD reviewers, rather than according to Cochrane guidelines.

It is unlikely at this stage that inclusion of the relatively immature results of the Italian trial (Frustaci 1987) and the small number of patients from the American trial (NCI‐92‐C‐0210) will impact on the results and conclusions of the review and so an update of the analysis is not planned until the EORTC study has closed (EORTC 62931). This is not expected until at least 2003. ‐ 24/05/02

Acknowledgements

The following institutions, investigators (groups) and secretariat† form the Sarcoma Meta‐analysis Collaboration and participated in this meta‐analysis: The Jubileum Institute, Lund University Hospital ‐ T.A. Alvegård, H. Sigurdsson (Scandinavian Sarcoma Group); Columbia‐Presbyterian Medical Center, Columbia University, New York ‐ K. Antman (Dana‐Farber Cancer Institute / Massachusetts General Hospital); SIAK Coordinating Center, Bern ‐ M. Bacchi; Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Michigan, Michigan ‐ L. H. Baker (Intergroup Sarcoma Committee); M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, University of Texas, Texas ‐ R. S. Benjamin (M.D. Anderson Cancer Center); Gynecologic Oncology Group Statistical Office, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo ‐ M. F. Brady (Gynecologic Oncology Group); Christie Hospital, Manchester (currently London Regional Cancer Center, Ontario) ‐ V. Bramwell (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer); Institut Bergonie, Bordeaux ‐ B. N. Bui (Institut Bergonie) ; Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota ‐ J. H. Edmonson (Mayo Clinic); Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston ‐ C. D. M. Fletcher†; Istituti Ortopedici Rizzoli, Bologna ‐ F. Gherlinzoni (Istituti Ortopedici Rizzoli); Hamilton Regional Cancer Center, Ontario ‐ G. Jones†, M. Patel†; University Hospital, Lausanne ‐ S. Leyvraz (Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research) ; Department of Biostatistics, Institut Curie, Paris ‐ V. Mosseri†; The University of Alabama at Birmingham, Alabama ‐ G. A. Omura (Gynecologic Oncology Group); Medical Research Council Cancer Trials Office, Cambridge ‐ M. K. B. Parmar†, L. A. Stewart†, J. F. Tierney†; Centre René Huguenin, St. Cloud ‐ J. Rouëssé (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer); European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, University College London, London ‐ M. C. Ruiz de Elvira†; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Statistical Office, Dana‐Farber Cancer Institute, Boston ‐ L. Ryan (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group); Department of Oncology, University College London Medical School, London ‐ R. L. Souhami†; Meta‐analysis Unit, EORTC Data Center, Brussels ‐ R. Sylvester†; Institut Gustave‐Roussy, Villejuif ‐ T. Tursz† (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer); Department of Oncology, Universitaire Ziekenhuizen, Leuven ‐ A. T. van Oosterom (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer); Surgery Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda ‐ J. C. Yang (National Cancer Institute).

We would like to thank all those patients who took part in the trials and contributed to this research. The meta‐analysis would not have been possible without their help or without the collaborating institutions who kindly supplied their trial data. For their helpful comments on the manuscript and general contribution to the project we also thank Luc Bijnens, Derek Crowther, William Kraybill and Burton Eisenberg. This meta‐analysis and the collaborators meeting was supported by the British Medical Research Council.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Effects of adjuvant chemotherapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Local Recurrence‐free Interval | 13 | 1315 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.73 [0.56, 0.94] |

| 2 Distant Recurrence‐free Interval | 13 | 1315 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.70 [0.57, 0.85] |

| 3 Overall Recurrence‐free Survival | 14 | 1366 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.75 [0.64, 0.87] |

| 4 Overall Survival | 14 | 1544 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.89 [0.76, 1.03] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Effects of adjuvant chemotherapy, Outcome 1 Local Recurrence‐free Interval.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Effects of adjuvant chemotherapy, Outcome 2 Distant Recurrence‐free Interval.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Effects of adjuvant chemotherapy, Outcome 3 Overall Recurrence‐free Survival.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Effects of adjuvant chemotherapy, Outcome 4 Overall Survival.

Comparison 2. Subgroup analysis.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall Survival | 24 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Age | 3 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Sex | 2 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Disease status (at randomisation) | 2 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 Disease site | 4 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.5 Histology | 5 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.6 Grade | 2 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.7 Tumour size | 3 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.8 Extent of resection | 2 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.9 Radiotherapy | 2 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subgroup analysis, Outcome 1 Overall Survival.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bergonie 1981.

| Methods | RCT, 1981‐88 | |

| Participants | 65 adults with sarcoma of the extremities, trunk, head, neck, retroperitoneum or pelvis | |

| Interventions | Local treatment (surgery with or without radiotherapy) plus doxorubicin*‐based combination (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, dacarbazine) chemotherapy vs local treatment alone *50 mg/m2 per cycle, 400‐500 mg/m2 total | |

| Outcomes | Local recurrence, distant recurrence, survival | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

DFCI/MGH 1978.

| Methods | RCT, 1978‐83 | |

| Participants | 46 adults with sarcoma of the extremities, trunk, head, neck, or retroperitoneum | |

| Interventions | Local treatment (surgery with or without radiotherapy) plus doxorubicin* chemotherapy vs local treatment alone *60 mg/m2 per cycle, 450 mg/m2 total | |

| Outcomes | Local recurrence, distant recurrence, survival | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

ECOG 1978.

| Methods | RCT, 1978‐82 | |

| Participants | 47 adults with sarcoma of the extremities, trunk, head, neck or retroperitoneum | |

| Interventions | Local treatment (surgery with or without radiotherapy) plus doxorubicin* chemotherapy vs local treatment alone *70mg/m2 per cylcle, 490mg/m2 total | |

| Outcomes | Any recurrence, survival | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

EORTC 1977.

| Methods | RCT, 1977‐88 | |

| Participants | 468 adults with sarcoma of the extremities, trunk, head, neck | |

| Interventions | Local treatment (surgery with or without radiotherapy) plus doxorubicin*‐based combination (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, dacarbazine) chemotherapy vs local treatment alone *50 mg/m2 per cycle, 400 mg/m2 total | |

| Outcomes | Local recurrence, distant recurrence, survival | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

GOG 1973.

| Methods | RCT, 1973‐82 | |

| Participants | 225 adults with sarcoma of the uterus | |

| Interventions | Local treatment (surgery with or without radiotherapy) plus doxorubicin* chemotherapy vs local treatment alone *60 mg/m2 per cycle, 480 mg/m2 total | |

| Outcomes | Local recurrence, distant recurrence, survival | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

IGSC 1983.

| Methods | RCT, 1983‐86 | |

| Participants | 92 adults with sarcoma of the extremities, trunk, head, neck or retroperitoneum | |

| Interventions | Local treatment (surgery with or without radiotherapy) plus doxorubicin* chemotherapy vs local treatment alone *70 mg/m2 per cycle, 420 mg/m2 total | |

| Outcomes | Local recurrence, distant recurrence, survival | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Mayo 1975.

| Methods | RCT, 1975‐81 | |

| Participants | 76 adults with sarcoma of the extremities or trunk | |

| Interventions | Local treatment (surgery) plus doxorubicin*‐based combination (vincristine, cyclophosphamide, dactinomycin, dacarbazine) chemotherapy vs local treatment alone *50 mg/m2 per cycle, 200 mg/m2 total | |

| Outcomes | Local recurrence, distant recurrence, survival | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

MDA 1973.

| Methods | RCT, 1973‐76 | |

| Participants | 59 adults with sarcoma of the extremities or trunk | |

| Interventions | Local treatment (surgery with or without radiotherapy) plus doxorubicin*‐based combination (cyclophosphamide, dactinomycin, vincristine) chemotherapy vs local treatment alone *60 mg/m2 per cycle, 420 mg/m2 total | |

| Outcomes | Local recurrence, distant recurrence, survival | |

| Notes | Data not available for 3 patients | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

NCI4 1977.

| Methods | RCT, 1977‐81 | |

| Participants | 26 adults with sarcoma of the extremities | |

| Interventions | Local treatment (surgery with or without radiotherapy) plus doxorubicin*‐based combination (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate) chemotherapy vs local treatment alone *50‐70 mg/m2 per cycle, 500‐550 mg/m2 total | |

| Outcomes | Local recurrence, distant recurrence, survival | |

| Notes | Time to event taken from the time of definitive surgery rather than the date of randomisation | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

NCI5 1977.

| Methods | RCT, 1977‐81 | |

| Participants | 80 adults with sarcomas of the trunk, head, neck, breast or retroperitoneum | |

| Interventions | Local treatment (surgery with or without radiotherapy) plus doxorubicin*‐based combination (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate) chemotherapy vs local treatment alone *50‐70 mg/m2 per cycle, 500‐550 mg/m2 total | |

| Outcomes | Local recurrence, distant recurrence, survival | |

| Notes | Time to event taken from date of definitive surgery rather than date of randomisation | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

NCI6 1977.

| Methods | RCT, 1977‐81 | |

| Participants | 41 adults with sarcoma of the extremities | |

| Interventions | Local treatment (surgery with or without radiotherapy) plus doxorubicin*‐based combination (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate) chemotherapy vs local treatment alone *50‐70 mg/m2 per cycle, 500‐550 mg/m2 total | |

| Outcomes | Local recurrence, distant recurrence, survival | |

| Notes | Time to event taken from the date of definitive surgery rather than the date of randomisation | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Rizzoli 1981.

| Methods | RCT, 1981‐86 | |

| Participants | 77 adults with sarcoma of the extremities | |

| Interventions | Local treatment (surgery with or without radiotherapy) plus doxorubicin* chemotherapy vs local treatment alone *75mg/m2 per cycle, 450mg/m2 total | |

| Outcomes | Local recurrence, distant recurrence, survival | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

SAKK 57/87.

| Methods | RCT, 1987‐90 | |

| Participants | 29 adults with sarcoma of the extremities or trunk | |

| Interventions | Local treatment (surgery with or without radiotherapy) plus doxorubicin*‐based combination (ifosfamide) chemotherapy vs local treatment alone *50‐90 mg/m2 per cycle, 550 mg/m2 total | |

| Outcomes | Local recurrence, distant recurrence, survival | |

| Notes | Unpublished | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

SSG 1981.

| Methods | RCT, 1981‐86 | |

| Participants | 240 adults with sarcoma of the extremities, trunk, head, neck, breast, thorax, abdomen | |

| Interventions | Local treatment (surgery with or without radiotherapy) plus doxorubicin* chemotherapy vs local treatment alone *60 mg/m2 per cycle, 540 mg/m2 total | |

| Outcomes | Local recurrence, distant recurrence, recurrence‐free survival, survival | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

sub1. 15‐30.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by age (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub1. 31‐60.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by age (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub1. >60.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by age (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub2. Female.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by sex (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub2. Male.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by sex (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub3. Primary.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by disease status at randomisation (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub3. Recurrent.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by disease status at randomisation (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub4. Extremity.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by disease site (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub4. Others.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by disease site (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub4. Trunk.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by disease site (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub4. Uterus.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by disease site (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub5. Leiomyosarcoma.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by histology (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub5. Liposarcoma.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by histology (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub5. MFH.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by histology (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub5. Others.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by histology (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub5. Synovial.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by histology (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub6. High.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by grade (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | High grade: AJC grades 2 and 3, FNLCC grades 2 and 3 and Broder's grades 3 and 4. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub6. Low.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by grade (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | Low grade: American Joint Cancer Committee (AJC) grade 1, Federation Nationale des Centre de Lutte Contre le Cancer (FNLCC) grade 1 and Broder's (B) grades 1 and 2. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub7. <5cm.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by tumour size (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub7. =5‐10cm.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by tumour size (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub7. >10cm.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by tumour size (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub8. Clear.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by extent of resection (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub8. Not clear.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by extent of resection (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub9. No.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by radiotherapy (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

sub9. Yes.

| Methods | Subgroup analysis by radiotherapy (stratified by trial) | |

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

GOG: Gynecologic Oncology Group; DFCI/MGH: Dana‐Farber Cancer Institute / Massachusetts General Hospital; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; SSG: Scandinavian Sarcoma Group; Rizzoli: Istituti Ortopedici Rizzoli; IGSC: Intergroup Sarcoma Committee; MDA: M.D. Anderson Cancer Center; Mayo: Mayo Clinic; NCI: National Cancer Institute, EORTC: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; Bergonie: Institut Bergonie, SAKK: Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Baker 1987 | Ineligible: Not an adjuvant study, but a chemotherapy comparison in advanced disease |

| Borden 1990 | Ineligible: Not an adjuvant study, but a chemotherapy comparison in advanced disease |

| Eilber 1988 | Ineligible: All patients received intra‐arterial induction chemotherapy before randomisation |

| EST‐3782 | Ineligible: Only patients with inoperable, unresectable, or incompletely resected pimaries included |

| Frustaci 1987 | Ineligible: Trial closed after the cut‐off date described in inclusion criteria, but is eligible for inclusion in an update |

| Kinsella 1988 | Eligible: Data could not be obtained |

| NCI‐92‐C‐0210 | Ineligible: Trial closed after the cut‐off date described in inclusion criteria, but is eligible for inclusion in an update |

| Pinedo 1988 | Ineligible: Not a RCT, but a review of chemotherapy |

| Piver 1988 | Eligible: Data could not be obtained |

| Schoenfeld 1982 | Ineligible: Not an adjuvant study, but a chemotherapy comparsion in advanced disease |

| SWOG‐8791 | Eligible: Data could not be obtained |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

EORTC 62931.

| Trial name or title | Phase II randomized study of adjuvant high‐dose DOX/IFF with G‐CSFvs no adjuvant chemotherapy for high‐grade soft tissue sarcoma |

| Methods | |

| Participants | Patients with high‐grade sarcoma following definitive surgery |

| Interventions | High‐dose doxorubicin* + ifosfamide + G‐CSF chemotherapy vs *75 mg/m2 per cycle, 375 mg/m2 total |

| Outcomes | Local recurrence, recurrence‐free survival, survival, toxicity, morbidity |

| Starting date | |

| Contact information | EORTC |

| Notes |

Contributions of authors

All reviewers participated in the design, execution, and analysis of the review and reviewed twice commented on the overall intellectual content.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Medical Research Council, UK.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

There is no known conflict of interest.

Stable (no update expected for reasons given in 'What's new')

References

References to studies included in this review

Bergonie 1981 {published and unpublished data}

- Ravaud A, Bui BB, Coindre J‐M, Kantor G, Stöckle E, Lagarde P, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with cyvadic in high risk soft tissue sarcoma: a randomised prospective trial. In: Salmon SE editor(s). Adjuvant therapy of cancer VI. Philadelphia: Saunders, W.B., 1990:556‐66. [Google Scholar]

DFCI/MGH 1978 {published and unpublished data}

- Antman K, Suit H, Amato D, Corson J, Wood W, Proppe K, et al. Preliminary results of a randomized trial of adjuvant doxorubicin for sarcomas: lack of apparent difference between treatment groups. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1984;2(6):601‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ECOG 1978 {published and unpublished data}

- Lerner HJ, Amato DA, Savlov ED, DeWys WD, Mittelman A, Urtasun RC, et al. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group: A comparison of adjuvant doxorubicin and observation for patients with localized soft tissue sarcoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1987;5(4):613‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

EORTC 1977 {published and unpublished data}

- Bramwell V, Rouesse J, Steward W, Santoro A, Schraffordt‐Koops H, Buesa J, et al. Adjuvant CYVADIC chemotherapy for adult soft tissue sarcoma ‐ reduced local recurrence but no improvement in survival: a study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1994;12(6):1137‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

GOG 1973 {published and unpublished data}

- Omura GA, Blessing JA, Major F, Liftshitz S, Ehrlich CE, Mangan C, et al. A randomized clinical trial of adjuvant adriamycin in uterine sarcomas: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1985;3(9):1240‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

IGSC 1983 {published and unpublished data}

- Antman K, Ryan L, Borden E, Wood WC, Lerner HJ, Corson JM, et al. Pooled results from three randomized adjuvant studies of doxorubicin versus observation in soft tissue sarcoma: 10 year results and review of the literature. In: Salmon SE editor(s). Adjuvant therapy of cancer VII. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1990:529‐43. [Google Scholar]

- Baker LH. Adjuvant therapy for soft tissue sarcomas. In: Ryan JR, Baker LH editor(s). Recent Concepts in Sarcoma Treatment. Dordecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1988:130‐5. [Google Scholar]

Mayo 1975 {published and unpublished data}

- Edmonson JH. Systemic chemotherapy following complete excision of nonosseous sarcomas: Mayo Clinic Experience. Cancer Treatment Symposia 1985;3:89‐97. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonson JH, Fleming TR, Ivins JC, Burgert EO, Jr, Soule EH, O'Connell MJ, et al. Randomized study of systemic chemotherapy following complere excision of nonosseous sarcomas. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1984;2(12):1390‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MDA 1973 {published and unpublished data}

- Benjamin RS, Terjanian TO, Fenoglio CJ, Barkley HT, Evans HL, Murphy WK, et al. The importance of combination chemotherapy for adjuvant treatment of high‐risk patients with soft‐tissue sarcomas of the extremities. In: Salmon SE editor(s). Adjuvant therapy of cancer V. Orlando: Grune & Stratton, 1987:735‐44. [Google Scholar]

NCI4 1977 {published and unpublished data}

- Chang AE, Kinsella T, Glatstein E, Baker AR, Sindelar WF, Lotze MT, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with high‐grade soft‐tissue sarcomas of the extremity. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1988;6(9):1491‐500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SA, Tepper J, Glatstein E, Costa J, Baker A, Brennan M, et al. Prospective randomized evaluation of adjuvant chemotherapy in adults with soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities. Cancer 1983;52:424‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NCI5 1977 {published and unpublished data}

- Glenn J, Kinsella T, Glatstein E, Tepper J, Baker A, Sugarbaker P, et al. A randomized prospective trial of adjuvant chemotherapy in adults with soft tissue sarcomas of the head and neck, breast, and trunk. Cancer 1985;55:1206‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn J, Sindelar WF, Kinsella T, Glatstein E, Tepper J, Gosta J, et al. Results of multimodality therapy of resectable soft‐tissue sarcomas of the retroperitoneum. Surgery 1985;97(3):316‐25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NCI6 1977 {published and unpublished data}

- Chang AE, Kinsella T, Glatstein E, Baker AR, Sindelar WF, Lotze MT, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with high‐grade soft‐tissue sarcomas of the extremity. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1988;6(9):1491‐500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SA, Tepper J, Glatstein E, et al. Prospective randomized evaluation of adjuvant chemotherapy in adults with soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities. Cancer 1983;52:424‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rizzoli 1981 {published and unpublished data}

- Gherlinzoni F, Bacci G, Picci P, Capanna R, Calderoni P, Lorenzi EG, et al. A randomized trial for the treatment of high‐grade soft‐tissue sarcomas of the extremities: preliminary observations. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1986;4(4):552‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picci P, Bacci G, Gherlinzoni F, Capanna R, Mercuri M, Ruggieri P, et al. Results of a randomised trial for the treatment of localized soft tissue tumors (STS) of the extremities in adult patients. In: Ryan JR, Baker LH editor(s). Recent Concepts in Sarcoma Treatment. Dordecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1988:144‐8. [Google Scholar]

SAKK 57/87 {unpublished data only}

- SAKK. Randomized study of adjuvant chemotherapy with adriamycin and ifosfamide versus observation in patients with soft‐tissue sarcomas of extremity and trunk. Data on file Unpublished.

SSG 1981 {published and unpublished data}

- Alvegård TA, Sigurdsson H, Mouridsen H, Solheim Ø, Unsgaard B, Ringborg U, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin in high‐grade soft tissue sarcoma: a randomized trial of the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1989;7(10):1504‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

sub1. 15‐30 {published and unpublished data}

sub1. 31‐60 {published and unpublished data}

sub1. >60 {published and unpublished data}

sub2. Female {published and unpublished data}

sub2. Male {published and unpublished data}

sub3. Primary {published and unpublished data}

sub3. Recurrent {published and unpublished data}

sub4. Extremity {published and unpublished data}

sub4. Others {published and unpublished data}

sub4. Trunk {published and unpublished data}

sub4. Uterus {published and unpublished data}

sub5. Leiomyosarcoma {published and unpublished data}

sub5. Liposarcoma {published and unpublished data}

sub5. MFH {published and unpublished data}

sub5. Others {published and unpublished data}

sub5. Synovial {published and unpublished data}

sub6. High {published and unpublished data}

sub6. Low {published and unpublished data}

sub7. <5cm {published and unpublished data}

sub7. =5‐10cm {published and unpublished data}

sub7. >10cm {published and unpublished data}

sub8. Clear {published and unpublished data}

sub8. Not clear {published and unpublished data}

sub9. No {published and unpublished data}

sub9. Yes {published and unpublished data}

References to studies excluded from this review

Baker 1987 {published data only}

- Baker LH, Franks J, Fine G, Balcerzak SP, Stephens RL, Stuckey WJ, et al. Combination chemotherapy using Adriamycin, DTIC, cyclophosphamide, and actinomycin D for advanced soft tissue sarcomas: a randomised comparative trial, A phase III, Southwest Oncology Group Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1987;5(6):851‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Borden 1990 {published data only}

- Borden EC, Amato DA, Edmonson JH, Ritch PS, Shiraki M. Randomized comparison of doxorubicin and vindesinme to doxorubicin for patients with metastatic soft‐tissue sarcomas. Cancer 1990;66:862‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eilber 1988 {published data only}

- Eilber FR, Giuliano AE, Huth JF, Morton DL. A randomised prospective trial using postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy (Adriamycin) in high‐grade extremity soft‐tissue sarcoma. American Journal of Clinical Oncology 1988;11(1):39‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

EST‐3782 {unpublished data only}

- IGSC. A randomized trial of adjuvant doxorubicin (Adriamycin) versus standard therapy (a delay of chemotherapy until the time of possible relapse. Data on file Unpublished.

Frustaci 1987 {published data only}

- Frustaci S, Gherlinzoni F, Paoli A, Pignatti G, Zmerly H, Azzarelli A, Comandone A, Buonadonna A, Olmi P, Ippolito V, Barbieri E, Apice G, Zakotnic B, Bacci G, Picci P, on behalf of the National Research Council (Italy). Preliminary results of an adjuvant randomized trial on high risk extremity soft tissue sarcomas (STS). The interim analysis. Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1997; Vol. 16:696a, A1785.

Kinsella 1988 {published data only}

- Kinsella T, Sindelar W, Lack E, Glatstein E, Rosenberg SA. Kinsella T, Sindelar W, Lack E, Glatstein E, Rosenberg SA. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1988;6:18‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NCI‐92‐C‐0210 {unpublished data only}

- NCI. Phase III randomized trial of adjuvant DOX/IFF vs no adjuvant chemotherapy following complete resection of adult high‐grade soft tissue sarcoma confined to an extremity. Data on file Unpublished.

Pinedo 1988 {published data only}

- Pinedo HM, Verweij J. The treatment of soft tissue sarcomas with focus on chemotherapy: a review. Radiotherapeutic Oncology 1986;5:193‐205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Piver 1988 {published data only}

- Piver MS, Lele SB, Marchetti DL, Emrich LJ. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on time to recurrence and survival of stage I uterine sarcomas. Journal of Surgical Oncology 1988;38:233‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schoenfeld 1982 {published data only}

- Schoenfeld DA, Roesenbaum C, Horton J, Wolter JM, Falkson G, DeConti RC. A comparison of Adriamycin versus Vincristine and Adraimycin, and Cyclosphosphamide versus Vincristine, Actinomycin‐D, and Cyclophosphamide for advanced sarcoma. Cancer 1982;50:2757‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

SWOG‐8791 {unpublished data only}

- SWOG. Phase III randomized study of adjuvant chemotherapy with ADR/DTIC/IPP vs no adjuvant therapy following resection with or without irradiation of adult grage III soft tissue sarcomas. Data on file Unpublished.

References to ongoing studies

EORTC 62931 {published data only}

- Phase II randomized study of adjuvant high‐dose DOX/IFF with G‐CSFvs no adjuvant chemotherapy for high‐grade soft tissue sarcoma. Ongoing study Starting date of trial not provided. Contact author for more information.

Additional references

Benjamin 1975

- Benjamin R, Weirnick P, Bachur N. Adriamycin: a new effective agent in the therapy of disseminated sarcomas. Medical and Pediatric Oncology 1975;1:63‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Blum 1974

- Blum RH, Carter SK. A new anticancer drug with significant clinical activity. Annals of Internal Medicine 1974;80(2):249‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collins 1987

- Collins R, Gray R, Godwin J, Peto R. Avoidance of large biases and large random errors in the assessment of moderate effects of treatment effects: the need for systematic overviews. Statistics in Medicine 1987;6:245‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Delaney 1991

- Delaney TF, Yang JC, Glatstein E. Adjuvant therapy for adult patients with soft tissue sarcomas. Oncology 1991;5(6):105‐18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dickersin 1995

- Dickersin K, Scherer R, Lefebvre C. Identifying relevant studies for systematic reviews. In: Chalmers I, Altman DG editor(s). Systematic Reviews. London: BMJ Publishing Group, 1995:17‐36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Freedman 1982

- Freedman LS. Tables of the number of patients required in clinical trials using the logrank test. Statistics in Medicine 1982;1:121‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gottlieb 1975

- Gottlieb JA, Baker LH, O'Bryan RM, Sinkovics JG, Hoogstraten B, Quagliana JM, et al. Adriamycin (NSC‐123127) used alone and in combination for soft tissue and bony sarcomas. Cancer Chemotherapy Reports Part 3 1975;6(2):271‐82. [Google Scholar]

Jones 1994

- Jones GW, Chouinard M, Patel M. Adjuvant adriamycin (doxorubicin) in adult patients with soft‐tissue sarcomas: A systematic overview and quantitative meta‐analysis. Clinical Investigations in Medicine 1994;14 Suppl 19:A772. [Google Scholar]

Kaplan 1958

- Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observation. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1958;53:457‐81. [Google Scholar]

McGrath 1995

- McGrath PC, Sloan DA, Kenady DE. Adjuvant therapy of soft‐tissue sarcomas. Clinics in Plastic Surgery 1995;22(1):21‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mertens 1995

- Mertens WC, Bramwell VHC. Adjuvant chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcomas. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America 1995;9(4):801‐15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tierney 1995

- Tierney JF, Mosseri V, Stewart LA, Souhami RL, Parmar MKB. Adjuvant chemotherapy for soft‐tissue sarcoma: review and meta‐analysis of the published results of randomised clinical trials. British Journal of Cancer 1995;72:469‐75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yusuf 1985

- Yusuf S, Peto R, Lewis J, Collins R, Sleight P. Beta‐blockade during and after myocardial infarction: An overview of the randomised trials. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 1985;27(5):335‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zalupski 1993

- Zalupski MM, Ryan JR, Hussein ME, Baker LH. Defining the role of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities. In: Salmon SE editor(s). Adjuvant Therapy of Cancer VII. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Company, 1993:385‐92. [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

SMAC 1997

- Sarcoma Meta‐analysis Collaboration. Adjuvant chemotherapy for localised resectable soft‐tissue sarcoma of adults: meta‐analysis of individual data. The Lancet 1997;350:1647‐54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]