Alzheimer disease and related dementias (ADRDs) are a global medical and public health challenge.1 Early and accurate diagnosis of these conditions can mitigate costs and improve medical care and quality of life.1 Cognitive assessment is an important part of ADRD diagnosis, and as we move into an age of ADRD therapeutics, accurate syndromic classification and disease monitoring will be a critical component of identifying trial participants and managing these diseases.1 Since the advent of clinical neuropsychologic assessments, these evaluations have been conducted using paper-and-pencil measures. It is becoming clear, however, that there are myriad benefits to incorporating digital technologies into assessment. Paper-and-pencil tests have typically been administered face-to-face in the clinic. The necessity of validated remote evaluations is apparent, underscored by the recent limitations on in-person visits secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic. Digital technologies are well positioned for a role in remote evaluation.

In this review, we cover several topics we hope will guide clinical neurologists considering adoption of technology in their practice, with a focus on ADRD assessment. We discuss benefits and limitations of adopting digital assessment tools and considerations for deciding which to use. We then review advances in tablet- and smartphone-based digital assessments. Personal computer (PC)-based evaluations have been reviewed elsewhere.2,3 Passive digital phenotyping and virtual reality assessments are not covered here. We conclude with practical strategies for bringing digital devices into clinical workflows.

Benefits of Digital Assessments

Integrating digital technologies into clinical practice and research has several possible benefits.4–6 Digital assessments may reduce time and cost associated with cognitive testing. If self-administered, there is also potential for reducing costs associated with staffing. This benefit is further increased if testing is performed remotely, rather than in the office or research center. Adaptive tests, such as those using item response theory, could reduce the time associated with determining an individual’s performance level.5 Many digital assessments provide an automated scoring system, which can reduce clinician time and the likelihood of scoring errors.5 Some assessments take the additional step of providing interpretative reports and evidence-based care recommendations.6,7 Remotely administered (online) technologies can be deployed quickly to a large group of participants and allow for frequent repeated assessments, providing a richer, more accurate classification of cognitive performance and longitudinal change.4,8 Naturalistic data collection in a nonclinical uncontrolled environment with everyday distractions may provide a sampling of cognitive abilities that more closely reflects real-world cognitive function.8 Digital assessments could also increase the reach of our assessment capabilities, potentially addressing health care disparities. For example, self-administered digital tests easily can be administered in different languages,5,7 and remote assessments could help reach persons in underserved communities who have barriers to clinic evaluations. Caution must be exerted, however, to ensure that digital assessments do not unintentionally exacerbate health disparities, considering that people in vulnerable groups may have limited digital literacy or access.9 Digital technologies may improve assessment accuracy and validity. For example, digital assessments have the potential for more accurate quantification of reaction time and motor functioning,4,5 and analyzing passive data (eg, daily functioning and language) could supplement standard neuropsychologic assessments.4

Challenges and Outstanding Questions

Although there is great enthusiasm about augmenting traditional neuropsychologic assessment with innovative technologies, it is challenging to choose the most appropriate device for a given clinical or research use. Because this is a relatively nascent field, there are several potential pitfalls, and caution should be exerted when considering digital assessment tools.3–5

Choosing a Device

An initial decision point is whether the examination will be self-administered or if an examiner (eg, medical assistant or trained psychologist) will conduct the evaluation. Although self-administration methods could reduce time and costs, the benefits may be offset by several challenges. For example, it is difficult to control environmental factors and distractions, to ensure that the examinee understands the task instructions, and to evaluate feigned performance.3,5

For self-administered assessments, a second decision point is use of a “managed” vs “bring-your-own” device (BYOD) model. Using a managed device (ie, a dedicated device for the cognitive assessment rather than the examinee’s device) reduces error variance associated with different hardware and software. Limitations to using a managed device include the resources required for device purchase and reduced flexibility. Individuals will also have differing levels of familiarity with the chosen device, which might affect performance.4

A BYOD model, often used in smartphone and browser-based testing, has the potential to reach a wider audience without the added expense of a managed device. Smartphones offer myriad novel data collection methods (see below). In a BYOD model, however, there are unresolved concerns about the effect of different hardware (eg, device size, type, touch screen, or touch-screen responsiveness) and software (eg, iOS vs Android, updates).3–5 Furthermore, browser-based tests may produce inaccurate stimulus-display timing and reaction-time capture when internet connectivity is suboptimal.5

When choosing a device, it is important to ensure that the software and hardware of the device are compatible with the minimum requirements specified in the software manual.3 It is also critical to review the required administrator qualifications (eg, medical assistant vs graduate degree).3

Scoring and Interpretation

Automated scoring and report generation are salient benefits of digital assessments. Boilerplate reports or diagnostic levels that are appealing for their simplicity, however, have the potential to mislead by giving the impression that supportive clinical history, imaging, lab studies, and more are unnecessary. Automated reports should be interpreted by qualified clinicians in the context of all other clinical data.3 When interpreting the scores, it is important to understand how the normative data for that test was derived. It cannot be assumed that digital versions of standard cognitive tests have the same reliability and validity as the original tests, nor should they be compared to the same normative data.3

Available Digital Assessments

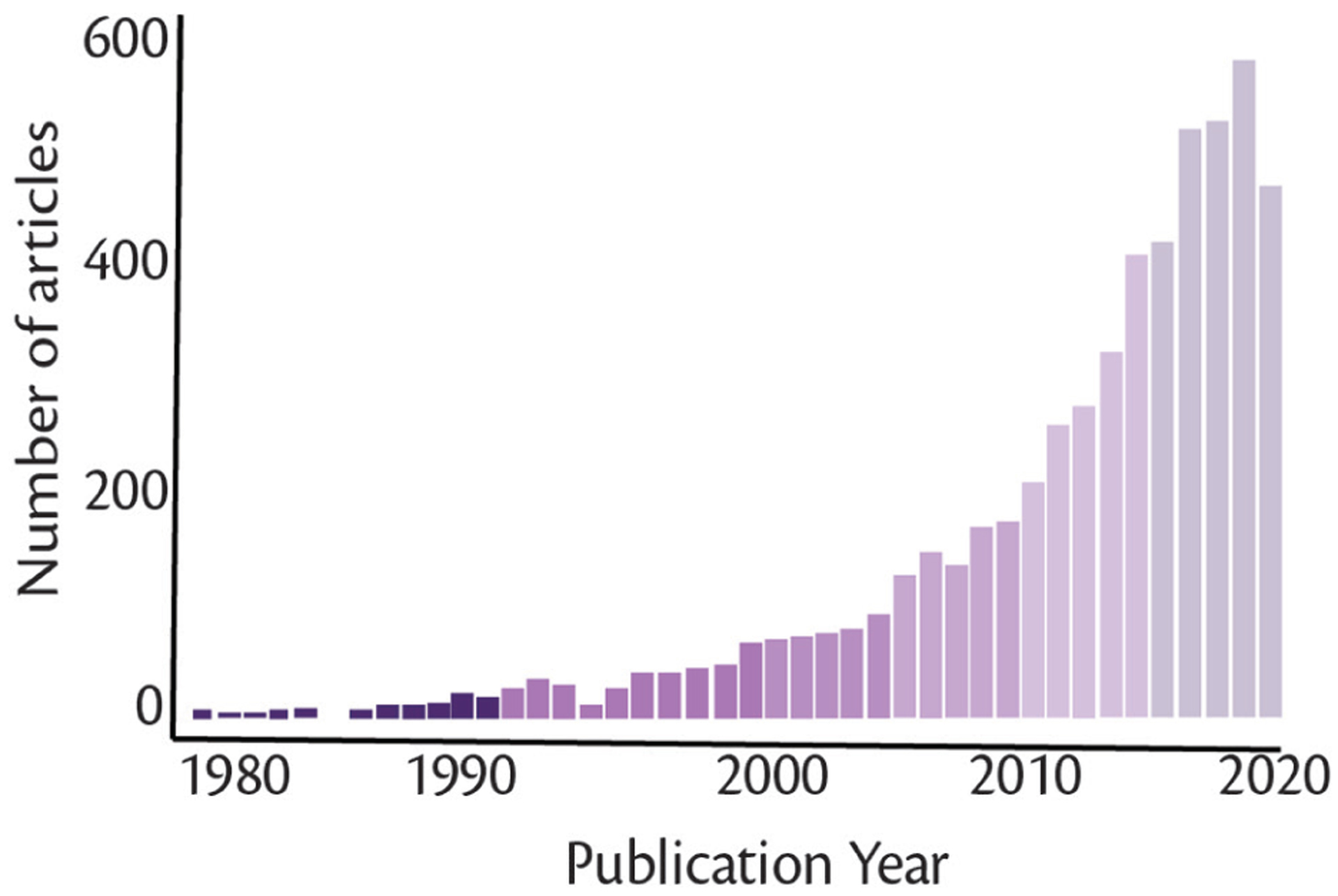

The list of digital cognitive assessment tools is large and expanding. Recent interest has grown exponentially (Figure). Because this article was written for a special issue on ADRD, we chose to highlight tablet-based measures and batteries validated for ADRD. Specifically, we highlight tools: 1) validated for differential diagnosis or early detection of ADRD, not simply being able to differentiate dementia from controls, 2) shown to be associated with ADRD biomarkers, or 3) evaluated for longitudinal disease monitoring. We loosened these criteria for our review of smartphone assessments, because of the lack of validated measures ready for clinical ADRD evaluations. This brief review is not meant to be exhaustive.

Figure.

PubMed search results highlight increasing interest in digital cognitive assessments. The search terms for this PubMed query were: (digital or computerized) (cognitive or neuropsych*) assessment. The query was conducted on September 17, 2020.

Tablet-Based Assessments

There has been a growing interest in the development and validation of tablet-based cognitive assessment tools. These devices have undergone a major shift in adoption across different demographics and have less variable device characteristics compared with smartphones and PCs.4 In particular, prior evidence suggests that adults over age 55 have a greater preference for use of touchscreen devices because of the direct and intuitive interaction, lower motor demands, and relative ease of use, even by examinees without prior experience.10,11 Moreover, tablets offer greater mobility than PCs and may be more user-friendly than smartphones for older adults given larger screen sizes and response fields.12 The expanding market of these appliances warrants attention to variability in features such as response rate logging, screen size and resolution, rendering of visual display elements, and frame rates; all of these factors may contribute to measurement error.4 Taking these considerations into account, we provide a review of the most widely researched tablet-based cognitive assessments (Table).

TABLE.

TABLET-BASED COGNITIVE ASSESSMENT MEASURES

| Domains | Peer-reviewed publicationsa | Administration | Administration time | Automated report | Languages | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Att/EF | Mem | Lang | VS | ||||||

| BHA | X | X | X | X | 4 | Examiner | 10 min | Yes | 18 |

| CAMCI | X | X | X | 12 | Self | 20 min | Yes | 1 | |

| CANS-MCI | X | X | X | 3 | Selfs | 30 min | Yes | 4 | |

| CANTAB-PAL | X | 100+ | Self | 8 min | ND | 45 | |||

| CBB | X | X | 100+ | Self | 12–15 min | ND | 43 | ||

| NIH EXAMINER | X | 14 | Examiner | 20–30 min | No | 6 | |||

| NIHTB-CB | X | X | X | 100+ | Examiner | 31 min | Yesb | 2 | |

Abbreviations: Att/EF, attention and executive dysfunction; BHA, Brain Health Assessment; CAMCI, Computer Assessment of Mild Cognitive Impairment; CANS-MCI, Computer-Administered Neuropsychological Screen for Mild Cognitive Impairment; CANTAB-PAL, Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery Paired Associates Learning; CBB, CogState Brief Battery; Lang, language; Mem, memory; ND, no data; NIH-EXAMINER, National Institutes of Health Executive Abilities: Measures and Instruments for Neurobehavioral Evaluation and Research; NIHTB-CB, NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery; VS, visuospatial.

For many of these tests, the majority of validation studies have occurred using personal computer (PC) versions as discussed in the text. It is critical that validation studies conducted on a paper-and-pencil or PC version of a test are not mistaken for validation in the tablet. Furthermore, the normative data gathered from paper-and-pencil or PC versions cannot be used for tablet-based adaptations.

Scores only.

Brain Health Assessment (BHA, memory.ucsf.edu/tabcat).

The BHA is a 10-minute 4-task battery developed and validated for the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and mild dementia. The battery is examiner-administered and features automated scoring and interpretation of results in an integrated report. BHA tests measure associative memory, executive functions and processing speed, language, and visuospatial skills and exhibit moderate-to-strong concurrent and neuroanatomic validity.7,13 At 85% specificity, the BHA has 100% sensitivity to dementia and 84% sensitivity to MCI in English speakers, and 81% sensitivity to MCI and dementia in Spanish speakers.14 The BHA has a particular advantage over the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in diagnosing MCI unlikely caused by AD.7 The BHA has also shown reliability measuring change over time in individuals with no cognitive impairment, MCI, and dementia and is sensitive to longitudinal cognitive decline in individuals who are positive for amyloid β on positron emission tomography (A β -PET+) but do not have ADRD.14 A self-administered version is forthcoming.

Computer Assessment of Mild Cognitive Impairment (CAMCI, https://pstnet.com/products/camci-research/).

The CAMCI is a 20-minute 8-task battery that can be self-administered and features automated scoring and result interpretation. The CAMCI measures attention, episodic memory, executive functions, visuospatial skills, and working memory.15 Test-retest reliability is good, and the CAMCI has 86% sensitivity and 94% specificity for detecting MCI.15 Studies support feasibility and practicality of implementing CAMCI in primary care settings.16

Computer-Administered Neuropsychological Screen for Mild Cognitive Impairment (CANS-MCI, https://screen-inc.com/).

The CANS-MCI is a 30-minute 8-task battery that can be self-administered with automated scoring, result interpretation, and care recommendations. The battery measures episodic memory, executive functions, and language6 with good test-retest reliability and moderate correlations with standard neuropsychologic measures.17 In a small study (n=35), the CANS-MCI had 89% sensitivity and 73% specificity to amnestic MCI.6

Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery Paired Associates Learning (CANTAB-PAL, https://www.cambridgecognition.com/cantab/cognitive-tests/memory/paired-associates-learning-pal/).

The CANTAB-PAL is a brief stand-alone portion of the much larger CANTAB battery. Within CANTAB, the CANTAB-PAL has the most validation in ADRD. CANTAB-PAL is an 8-minute nonverbal task of cued recall, widely studied across diagnostically, culturally, and linguistically diverse populations. This measure of visual associative memory has exhibited good reliability over time18 as well as correlations with conventional neuropsychologic tests19 and everyday functional measures.18 CANTAB-PAL showed a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 82% to MCI.18 Additionally, CANTAB-PAL has exhibited cross-sectional sensitivity to Aβ-cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels in a diagnostically mixed sample.20

CogState Brief Battery (CBB, https://www.cogstate.com/clinical-trials/computerized-cognitive-assessment/featured-batteries/).

CBB is a 15-minute 4-task battery of attention, episodic memory, speed, and working memory that is self-administered with automated scoring. The PC-version of the CBB has shown test-retest reliability21 and moderate-to-strong correlations with conventional neuropsychologic tests.22 CBB measures showed a sensitivity of 41% to 80% and specificity of 85% to 86% to MCI, and sensitivity of 53% to 100% and specificity of 85% to 86% to AD.23 The battery has also exhibited sensitivity to longitudinal decline in those with Aβ-positive test results with normal cognition and MCI24 and mild dementia25 but was not associated with Aβ-or tau-PET positivity in a cross-sectional study.26 Notably, CBB is accessed via a web browser, and the majority of validation studies have been conducted on a PC platform.21–25

Computerized Cognitive Composite for Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease (C3-PAD).

Designed as an exploratory endpoint for the A4 trial,a the C3-PAD includes CBB measures plus 2 memory paradigms: associative memory and pattern separation.27 At-home administration of the C3-PAD in 49 adults showed feasibility, alternate-form reliability (Cronbach alpha=0.93), a strong association between in-clinic and at-home versions (r2=0.51), and concurrent validity with standard paper-and-pencil tests.28 In 3,163 clinically normal adults, in-clinic C3-PAD assessments were moderately correlated with another cognitive composite, and participants who were Aβ-PET+ had poorer performance statistically, with small effect sizes (unadjusted Cohen d=−0.22, demographic-adjusted d=−0.11).27

National Institutes of Health Executive Abilities: Measures and Instruments for Neurobehavioral Evaluation and Research (NIH-EXAMINER, https://memory.ucsf.edu/research-trials/professional/examiner).

This 13-task battery, designed and validated on a PC, comprises measures of executive function, social cognition, and behavior; 6 of these executive tasks are considered core and combined into a psychometrically robust composite score.29 The PC version is sensitive to executive dysfunction in presymptomatic frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD),30 premanifest Huntington disease,31 symptomatic FTLD and AD,32 and associated with brain atrophy.30 Adaptation for tablet is complete for 4 of the NIH-EXAMINER tasks in TabCAT, and validation studies in ADRD are underway.

NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery (NIHTB-CB, https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/nih-toolbox/intro-to-nih-toolbox/cognition).

NIHTB-CB is a 31-minute 7-task battery validated across ages and clinical conditions. Designed for PC administration, NIHTB-CB has been adapted for tablets. The battery measures attention, episodic memory, executive functions, processing speed, and language, and the PC version has shown good reliability over time and moderate-to-strong correlations with standard neuropsychologic measures.33 The PC NIHTB-CB was 85% accurate in discriminating cognitively unimpaired adults mean age 52.5 (SD±12.0) from individuals with MCI and dementia,34 and poorer performances were associated with decreased hippocampal volumes in adults without cognitive impairment.35 Most recently, iPad-versions of NIHTB-CB tasks were shown to associate with tau-PET signal.36 Development and norming of smartphone versions are underway (https://www.mobiletoolbox.org/).

Smartphone Assessments

Smartphones assessments offer unique advantages and are being evaluated as digital cognitive assessments for ADRD. Among the first feasibility, reliability, and validity study of a mobile phone (iPhone 4)-delivered cognitive test in adults was a processing speed measure that showed strong test-retest reliability (r=0.73) and moderate correlations with the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) and measures of processing speed and executive functions.37 Smartphone software and hardware capabilities have improved since then, and now phones are often equipped with accelerometers, gyroscopes, global positioning systems (GPS), microphones, and cameras offering a multitude of data collection options, including audio capture and passive digital phenotyping. The relatively widespread availability of smartphones may position them well for broad adoption.38 Although this is an exciting area of development, there is much less empiric data on the validity and reliability of smartphone assessments, and insufficient data to recommend their use as clinical decision-making tools in ADRD. Many published studies only validate individual tests on the phone, often in specific populations. We briefly review several platforms that support a battery of smartphone cognitive assessments.

Ambulatory Cognitive Assessments.

In an assessment of the reliability and validity of 3 very brief cognitive tasks (each <1 minute) administered via smartphones, (the symbol search, dot memory, and n-back tests), adults age 25 to 65 (n=219) were provided with a smartphone and asked to complete a remote 14-day burst protocol with 5 assessment periods per day.8 Analyses indicated a between-person reliability greater than 0.97 and within-person reliabilities from 0.41 to 0.53, when assessed across all 14 days of measurements. Remote assessments exhibited significant, often strong correlations with in-person assessments of the same cognitive constructs. Validation in ADRD is needed.

Datacubed Health.

A commercial company, Datacubed Health, has developed a smartphone assessment platform (Linkt Health). The app currently supports over 10 cognitive tasks modeled after standard assessment paradigms, can collect audio recordings of individuals performing speech and language tasks, and includes a survey builder. The app also integrates passive data including GPS and pedometer data. Data collection is underway in a large cohort with familial (f-FTLD) and sporadic FTLD. The first 20 cases included 10 healthy adults (mean age 73.6±10), 4 participants with symptoms of corticobasal syndrome, behavioral variant FTD, logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia (PPA) and semantic variant PPA), and 6 participants from f-FTLD families who were asymptomatic. Participants were asked to complete 5 tasks 3 times over the course of 10 days. Compliance was approximately 88%.39 Reliability was assessed by correlating performance on the first assessment (typically done in clinic) with the average performance of the second and third (at-home) assessments. Most measures showed moderate-to-strong test-retest reliability, and the Flanker task, already promising as a sensitive measure for presymptomatic f-FTLD,30 showed excellent test-retest reliability.39

iVitality.

The iVitality app includes 5 assessments, modeled after verbal list learning, Trail Making, Stroop, reaction time, go/no-go, and n-back paradigms.40 Participants with a parental history of dementia completed a battery of tests at baseline and were notified to complete the tasks 3 more times over the course of 6 months (n=139 with follow-up).40 Mean adherence was 60% and moderate correlations were shown with standard paper-and-pencil evaluations. Validation in ADRD is needed.

Recommendations for Clinicians

The wide range of psychometrically sound computerized cognitive measures allows flexible implementation of these tools into clinical practice depending on the clinical question and needs of the populations served. Most experts agree “ideal” tools for MCI or dementia diagnosis should have affordable cost and reimbursement potential, reliable measurement of multiple cognitive domains across diverse populations, minimization of examiner’s involvement in scoring and interpretation, and sensitivity to longitudinal decline and disease biomarkers.41 Logistically, tools with high potential for scalable implementation should be brief (≤10 minutes), not require a physician for administration (ie, be self-administered by the patient or administered by trained clinical staff), and have the functionality to automatically generate an interpretive report with instant electronic medical record (EMR) integration.41 A number of the computerized measures covered in this review meet many of these criteria, and clinicians may consider developing a stepwise workflow to maximize efficient use of digital tools. For example, when the clinical question is whether the patient has a neurodegenerative disorder, the following steps may be used: 1) following the identification of a cognitive concern by the clinician, the patient takes the computerized test either at home (self-administered) or at a quiet place at the clinic (self-administered or administered by trained clinic staff); 2) test results are automatically generated and reported in the EMR, and the clinician reviews the findings; 3) if the results support possible cognitive impairment, the clinician conducts in-depth review of functional and neurologic domains based on the pattern of observed difficulties and completes an evaluation for treatable causes; 4) the clinician integrates all clinical data to determine diagnostic impressions; and 5) the patient retakes the cognitive tests at subsequent visits for monitoring of cognitive functions, particularly if a nonneurodegenerative cause is considered and an intervention is introduced.

Conclusions

Digital assessments may enhance the efficiency of evaluations in neurology and other clinics. Clinicians must choose from a panoply of digital assessments. Selecting an assessment platform requires a careful consideration of the empiric evidence, required device, user qualifications, and the logistics of clinical implementation. Tablet-based assessments are being rapidly validated for use in ADRD populations, and we reviewed several batteries with the greatest empiric support. Smartphone and other BYOD assessments offer several unique benefits, but more validation studies are required before understanding whether they may play a role in clinical evaluations, and until then they should be considered as research tools. We present a potential clinic workflow, acknowledging that greater research on implementation is required.

Footnotes

Disclosures

ET,and JT report no disclosures; AMS, ALB, and KLP have disclosures at www.practicalneurology.com

Clinical Trial of Solanezumab for Older Individuals Who May be at Risk for Memory Loss (NCT02008357)

Contributor Information

Adam M. Staffaroni, Department of Neurology, Memory and Aging Center, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

Elena Tsoy, Department of Neurology, Memory and Aging Center, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

Jack Taylor, Department of Neurology, Memory and Aging Center, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

Adam L. Boxer, Department of Neurology, Memory and Aging Center, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

Katherine L. Possin, Department of Neurology, Memory and Aging Center, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, Global Brain Health Institute, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. Facts and Figures. Published 2018. Accessed October 8, 2020. https://www.alz.org/media/homeoffice/factsandfigures/facts-and-figures.pdf.

- 2.Zygouris S, Tsolaki M. Computerized cognitive testing for older adults: a review. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2015;30(1):13–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer RM, Iverson GL, Cernich AN, Binder LM, Ruff RM, Naugle RI. Computerized neuropsychological assessment devices: joint position paper of the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology and the National Academy of Neuropsychology. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2012;27(3):362–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Germine L, Reinecke K, Chaytor NS. Digital neuropsychology: challenges and opportunities at the intersection of science and software. Clin Neuropsychol. 2019;33(2):271–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parsons TD, McMahan T, Kane R. Practice parameters facilitating adoption of advanced technologies for enhancing neuropsychological assessment paradigms. Clin Neuropsychol. 2018;32(1):16–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed S, de Jager C, Wilcock G. A comparison of screening tools for the assessment of mild cognitive impairment: preliminary findings. Neurocase. 2012;18(4):336–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Possin KL, Moskowitz T, Erlhoff SJ, et al. The brain health assessment for detecting and diagnosing neurocognitive disorders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(1):150–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sliwinski MJ, Mogle JA, Hyun J, Munoz E, Smyth JM, Lipton RB. Reliability and validity of ambulatory cognitive assessments. Assessment. 2018;25(1):14–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nouri S, Khoong EC, Lyles CR, Karliner L. Addressing equity in telemedicine for chronic disease management during the Covid-19 pandemic. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. 2020;1(3). https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0123 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canini M, Battista P, Della Rosa PA, et al. Computerized neuropsychological assessment in aging: testing efficacy and clinical ecology of different interfaces. Comput Math Methods Med. 2014;2014:804723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsoy E, Possin KL, Thompson N, et al. Self-administered cognitive testing by older adults at-risk for cognitive decline. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2020;7(4):283–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaportzis E, Clausen MG, Gow AJ. Older adults perceptions of technology and barriers to interacting with tablet computers: a focus group study. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1687. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alioto AG, Mumford P, Wolf A, et al. White matter correlates of cognitive performance on the UCSF brain health assessment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2019;25(6):654–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsoy E, Erlhoff SJ, Goode CA, et al. BHA-CS: A novel cognitive composite for Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12(1):e12042. doi: 10.1002/dad2.12042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saxton J, Morrow L, Eschman A, Archer G, Luther J, Zuccolotto A. Computer assessment of mild cognitive impairment. Postgrad Med. 2009;121(2):177–185. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2009.03.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millett G, Naglie G, Upshur R, Jaakkimainen L, Charles J, Tierney MC. Computerized cognitive testing in primary care. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2018;32(2):114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tornatore JB, Hill E, Laboff JA, McGann ME. Self-administered screening for mild cognitive impairment: initial validation of a computerized test battery. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17(1):98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnett JH, Blackwell AD, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. The paired associates learning (PAL) test: 30 years of CANTAB translational neuroscience from laboratory to bedside in dementia research. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2016;28:449–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matos Gonçalves M, Pinho MS, Simões MR. Construct and concurrent validity of the Cambridge neuropsychological automated tests in Portuguese older adults without neuropsychiatric diagnoses and with Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2018;25(2):290–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reijs BLR, Ramakers IHGB, Köhler S, et al. Memory correlates of Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid markers: a longitudinal cohort study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;60(3):1119–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammers D, Spurgeon E, Ryan K, et al. Reliability of repeated cognitive assessment of dementia using a brief computerized battery. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2011;26(4):326–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maruff P, Thomas E, Cysique L, et al. Validity of the cogstate brief battery: relationship to standardized tests and sensitivity to cognitive impairment in mild traumatic brain injury, schizophrenia, and AIDS dementia complex. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;24(2):165–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maruff P, Lim YY, Darby D, et al. Clinical utility of the cogstate brief battery in identifying cognitive impairment in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Psychol. 2013;1(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim YY, Pietrzak RH, Bourgeat P, et al. Relationships between performance on the cogstate brief battery, neurodegeneration, and Aβ accumulation in cognitively normal older adults and adults with MCI. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2015;30(1):49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim YY, Villemagne VL, Laws SM, et al. Performance on the cogstate brief battery is related to amyloid levels and hippocampal volume in very mild dementia. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;60(3):362–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stricker NH, Lundt ES, Albertson SM, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic accuracy of the cogstate brief battery and auditory verbal learning test in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and incident mild cognitive impairment: implications for defining subtle objective cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(1):261–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papp KV, Rentz DM, Maruff P, et al. ;on behalf of the A4 Study Team. The computerized cognitive composite (C3) in A4, an Alzheimer’s disease secondary prevention trial. J Prev Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020: 10.14283/jpad.2020.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Rentz DM, Dekhtyar M, Sherman J, et al. The feasibility of at-home iPad cognitive testing for use in clinical trials. J Prev Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016;3(1):8–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kramer JH, Mungas D, Possin KL, et al. NIH EXAMINER: conceptualization and development of an executive function battery. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2014;20(1):11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Staffaroni AM, Bajorek L, Casaletto KB, et al. Assessment of executive function declines in presymptomatic and mildly symptomatic familial frontotemporal dementia: NIH-EXAMINER as a potential clinical trial endpoint. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(1):11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.You SC, Geschwind MD, Sha SJ, et al. Executive functions in premanifest Huntington’s disease. Mov Disord. 2014;29(3):405–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Possin KL, Feigenbaum D, Rankin KP, et al. Dissociable executive functions in behavioral variant frontotemporal and Alzheimer dementias. Neurology. 2013;80(24):2180–2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weintraub S, Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, et al. Cognition assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology. 2013;80(11 S3):S54–S64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hackett K, Krikorian R, Giovannetti T, et al. Utility of the NIH Toolbox for assessment of prodromal Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement (Amst). 2018;10:764–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Shea A, Cohen RA, Porges EC, Nissim NR, Woods AJ. Cognitive aging and the hippocampus in older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Snitz BE, Tudorascu DL, Yu Z, et al. Associations between NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery and in vivo brain amyloid and tau pathology in non-demented older adults. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12(1):e12018. doi: 10.1002/dad2.12018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brouillette RM, Foil H, Fontenot S, et al. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of a smartphone based application for the assessment of cognitive function in the elderly. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pew Research Center. Internet and Mobile Technology: Mobile Fact Sheet. Published June 12, 2019. Accessed October 10, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/

- 39.Taylor JC, Staffaroni AM, Heuer HW, et al. Remote monitoring technologies for frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Paper presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2020. July 27–30, 2020. Accessed October 10, 2020. https://alz.confex.com/alz/20amsterdam/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/45694 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jongstra S, Wijsman LW, Cachucho R, Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Mooijaart SP, Richard E. Cognitive testing in people at increased risk of dementia using a smartphone app: the iVitality proof-of-principle study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2017;5(5):e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sabbagh MN, Boada M, Borson S, et al. Early detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in primary care. J Prev Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020;7(3):165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]