Abstract

Background

Telephone communication is increasingly being accepted as a useful form of support within health care. There is some evidence that telephone support may be of benefit in specific areas of maternity care such as to support breastfeeding and for women at risk of depression. There is a plethora of telephone‐based interventions currently being used in maternity care. It is therefore timely to examine which interventions may be of benefit, which are ineffective, and which may be harmful.

Objectives

To assess the effects of telephone support during pregnancy and the first six weeks post birth, compared with routine care, on maternal and infant outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (23 January 2013) and reference lists of all retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials, comparing telephone support with routine care or with another supportive intervention aimed at pregnant women and women in the first six weeks post birth.

Data collection and analysis

Three review authors independently assessed studies identified by the search strategy, carried out data extraction and assessed risk of bias. Data were entered by one review author and checked by a second. Where necessary, we contacted trial authors for further information on methods or results.

Main results

We have included data from 27 randomised trials involving 12,256 women. All of the trials examined telephone support versus usual care (no additional telephone support). We did not identify any trials comparing different modes of telephone support (for example, text messaging versus one‐to‐one calls). All but one of the trials were carried out in high‐resource settings. The majority of studies examined support provided via telephone conversations between women and health professionals although a small number of trials included telephone support from peers. In two trials women received automated text messages. Many of the interventions aimed to address specific health problems and collected data on behavioural outcomes such as smoking cessation and relapse (seven trials) or breastfeeding continuation (seven trials). Other studies examined support interventions aimed at women at high risk of postnatal depression (two trials) or preterm birth (two trials); the rest of the interventions were designed to offer women more general support and advice.

For most of our pre‐specified outcomes few studies contributed data, and many of the results described in the review are based on findings from only one or two studies. Overall, results were inconsistent and inconclusive although there was some evidence that telephone support may be a promising intervention. Results suggest that telephone support may increase women's overall satisfaction with their care during pregnancy and the postnatal period, although results for both periods were derived from only two studies. There was no consistent evidence confirming that telephone support reduces maternal anxiety during pregnancy or after the birth of the baby, although results on anxiety outcomes were not easy to interpret as data were collected at different time points using a variety of measurement tools. There was evidence from two trials that women at high risk of depression who received support had lower mean depression scores in the postnatal period, although there was no clear evidence that women who received support were less likely to have a diagnosis of depression. Results from trials offering breastfeeding telephone support were also inconsistent, although the evidence suggests that telephone support may increase the duration of breastfeeding. There was no strong evidence that women receiving telephone support were less likely to be smoking at the end of pregnancy or during the postnatal period.

For infant outcomes, such as preterm birth and infant birthweight, overall, there was little evidence. Where evidence was available, there were no clear differences between groups. Results from two trials suggest that babies whose mothers received support may have been less likely to have been admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), although it is not easy to understand the mechanisms underpinning this finding.

Authors' conclusions

Despite some encouraging findings, there is insufficient evidence to recommend routine telephone support for women accessing maternity services, as the evidence from included trials is neither strong nor consistent. Although benefits were found in terms of reduced depression scores, breastfeeding duration and increased overall satisfaction, the current trials do not provide strong enough evidence to warrant investment in resources.

Plain language summary

Telephone support for women during pregnancy and up to six weeks after the birth

Telephone support may be of benefit to women with particular problems during pregnancy and in the first six weeks after the birth of the baby but it is not clear which interventions may be helpful, which are ineffective, and which may be harmful.

Telephone communication is increasingly being accepted as a useful form of support within health care, with many telephone‐based interventions currently being used in maternity care.

In this review we have included results from 27 randomised trials with more than 12,000 women. All of the trials examined telephone support versus usual care (no additional telephone support). In two trials women received automated text messages. We did not identify any trials comparing different types of telephone support (for example, text messaging versus one‐to‐one calls). All but one of the trials were carried out in high‐resource settings. The majority of studies examined support provided via telephone conversations between women and health professionals although a small number of trials included telephone support from peers. Many of the results described in the review are based on findings from only one or two studies. Overall, results were inconsistent and inconclusive. Telephone support may increase women's overall satisfaction with their care during pregnancy and the postnatal period; although results for both periods were from only two studies. There was no consistent evidence confirming that telephone support reduces anxiety during pregnancy or after the birth of the baby. Evidence from two trials showed that women who received support had lower average depression scores in the postnatal period but without clear evidence that women who were supported were less likely to have a diagnosis of depression. Results from trials encouraging breastfeeding through telephone support were also inconsistent, although there was some evidence that telephone support may increase the duration of breastfeeding. There was no strong evidence that women receiving telephone support were less likely to be smoking at the end of pregnancy or during the postnatal period.

For infant outcomes, such as preterm birth and infant birthweight, overall, there was little evidence. Where evidence was available, there were no clear differences between groups.

There remains uncertainty regarding the benefit of telephone support and despite some encouraging findings, there is insufficient evidence to recommend routine telephone support for women accessing maternity services.

Background

Telephone interventions as part of health services and M‐health (i.e. health‐service provision via mobile communication technologies) (Vital Wave Consulting 2009), have grown in popularity, reaching those who, previously, may not have been reached. M‐health is particularly important in a low‐resourced setting where women are isolated by geographical location, and often have to travel long distances to access health‐professional support. Approximately 64% of all mobile phone users are resident in low‐resourced settings (United Nations 2007). Furthermore, estimates show that by 2012, half of all individuals in remote areas of the world will have mobile phones (Vital Wave Consulting 2009).

The use of telephone communication as a means of providing support in health care is not new; the first report appeared in the Lancet in 1897 when a doctor used communication via the telephone to diagnose a child with croup (Fosarelli 1983). Over a decade ago researchers suggested that the telephone was one of the most under‐utilised resources in health care (Latimer 1998; Oda 1995). However, telephone communication is increasingly being accepted as a useful form of support within health care (Wootton 2001; Wyatt 2001). The boom in mobile phone technology, in particular, has enhanced this acceptance, leading to its use in a number of healthcare settings.

Within maternity care, telephone support has been provided in the antenatal and postnatal periods. In the antenatal period telephone support has been used to support women in different ways including: to assist pregnant women with smoking cessation (Solomon 2005); to support women at risk of preterm birth (Moore 2004) and as a means of conducting maternity triage (Kennedy 2007). The potential psychosocial benefits of telephone support for pregnant women have also been explored (Bullock 1995), offering some confirmation of benefit.

In the postnatal period telephone ‘hot lines’ have grown in popularity, partly in response to early hospital discharge policies, in an attempt to provide continuity and support to parents (Rush 1991; Siegel 1992). These ‘hotlines’ appear to be valued by women, particularly for advice on breastfeeding and newborn care (Osman 2010). Some of these services were established exclusively as means of providing breastfeeding support (Chamberlain 2005; Wang 2008); others focused on mothers who were considered to be at risk of complications, for example, following caesarean birth (David 2010).

Description of the intervention

Telephone support presents itself in different ways. Support may be passive, whereby support is only available when requested, or it may be proactively offered. Scheduled and unscheduled telephone interactions have also been reported (Knight 2010). The medium for the support may be text messaging (Jareethum 2008) or verbal communication. Furthermore, support may be offered by a healthcare professional or a lay person. Telephone support may target a particular sample population, with the commonality of a particular medical condition, e.g. diabetes, or it may be used in health promotion, e.g. to support smoking cessation.

An earlier systematic review of telephone support for pregnant and postnatal women included 14 randomised controlled trials involving 8037 women (Dennis 2008) The authors reviewed telephone support interventions in which the primary focus was smoking, preterm birth, low birthweight, breastfeeding, or postpartum depression. Although there were methodological weaknesses in some of the reported trials, the review authors concluded that proactive telephone support may (a) assist in preventing smoking relapse, (b) play a role in preventing low birthweight, (c) increase breastfeeding duration and exclusivity, and (d) decrease postpartum depression symptoms. None of the telephone interventions were effective in improving preterm birth or smoking cessation rates.

Why it is important to do this review

Telephones are now an integral tool in mother and health‐professional communication. Given the increase in telephone communications, coupled with extensive global resource deficits, this trend it likely to continue. Although an earlier systematic review (Dennis 2008) provided some evidence of benefit in specific areas of maternity care, there is a plethora of telephone‐based interventions currently being used in maternity care. It is therefore timely to build on previous assessments to examine which interventions may be of benefit, which are ineffective, and which may be harmful.

Objectives

The primary objective is to assess the effects of telephone support during pregnancy and the first six weeks post birth, compared with routine care, on maternal and infant outcomes.

The secondary objective is to compare the effect of different types of telephone support, on maternal and infant outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all published and unpublished randomised controlled trials, comparing telephone support with routine care or with another supportive intervention. We also considered cluster‐randomised trials. Quasi‐randomised trials and cross‐over studies were excluded.

Types of participants

Pregnant women and postnatal women in the first six weeks post birth.

Types of interventions

All interventions aimed at supporting women by using telephones, whether for general support/information or for a specific medical/social reason (e.g. diabetes, smoking). We have included studies where the intervention is introduced in pregnancy or in the first six weeks post birth, or both. The intervention may, or may not, have extended from the antenatal to postnatal period. Interventions may have been in any setting and delivered by healthcare staff, peer supporters or using automated messaging.

We planned to make the following comparisons.

Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support.

Verbal telephone support versus text support.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Maternal satisfaction with support during pregnancy and the first six months postpartum (as defined by trial authors).

Maternal anxiety (measures as defined by trial authors, e.g. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale).

Secondary outcomes

Maternal outcomes

Mother‐infant attachment.

General health (e.g. as defined by standardised measures such as general health questionnaires).

Mortality and serious morbidity (e.g. perineal haematoma or deep surgical infection).

Health service utilisation (presentation/attendance at clinics, accident and emergency departments or general practices).

Postpartum depression (measures as defined by author, e.g. the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)).

Positive behaviour change (as defined by trial authors, e.g. smoking reduction).

Infant outcomes

Preterm birth/low birthweight.

Breastfeeding duration (exclusive or combined feeding).

Infant developmental measures (physical and cognitive as defined by trial authors).

Neonatal/infant mortality.

Major neonatal/infant morbidity (as defined by trial authors, e.g. prolonged admission to special care baby unit).

Service

Intervention cost.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We contacted the Trials Search Co‐ordinator to search the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (23 January 2013).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We included abstracts provided sufficient data and methodological detail were available. Where necessary, we contacted the authors of abstracts to obtain further information.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of all retrieved trial reports.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Three review authors (T Lavender (TL), S Milan (SM) and R Smyth (RS)) independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion with the whole team.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, three review authors (T Dowswell (TD), R Smyth (RS) and S Milan (SM)) extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the remaining authors. TD entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2012) and data were checked for accuracy by RS.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three review authors (TD, SM, RS) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving the remaining authors.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence and determined whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

It is very difficult to blind staff and participants to randomisation group for this type of intervention. Theoretically, it may be possible to randomise participants to two different phone interventions with one of them designated as the control intervention. We have described for each included study the methods used, if any, to attempt to blind study participants or staff from knowledge of which intervention a participant received, and we have noted where any information was provided on the success of blinding. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

It may be possible to blind outcome assessors, and we have described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind them from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We have described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We state whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or was supplied by the trial authors, we have re‐included missing data in our analyses.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated' analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting bias (checking for reporting bias)

We have described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other sources of bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We have also described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We have made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions(Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings. We planned to explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses. In this version of the review, too few studies contributed data to allow this planned analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we have presented results as summary risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference (MD) if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We planned to include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. In this version of the review we identified one cluster‐randomised trials that was eligible for inclusion. The author reported adjusted data for this trial and these data are presented in an additional table (Table 1).

1. Mobile phone intervention and skilled attendance at the birth.

| OUTCOME | Intervention (Total 1311 women) | Control (Total 1239 women) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (OR) |

| Skilled attendant at the birth (all) Unadjusted data |

766 (60%) | 560 (47%) | |

| Skilled attendant at the birth (rural residence) OR adjusted to take account of cluster‐design effect |

317 (43%) | 313 (44%) | 0.85 (95% CI 0.42 to 1.71) |

| Skilled attendant at the birth (urban residence) OR adjusted to take account of cluster‐design effect |

449 (82%) | 247 (50%) | 5.73 (95% CI 1.51 to 21.81) P < 0.01 |

CI: confidence interval

In updates of the review if more such trials are included, we will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook using an estimate of the intra‐cluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

We have not included cross‐over trials as these are not an appropriate study design for the interventions in this review.

Other unit of analysis issues

For studies including multiple pregnancies, we have treated the infants as independent and noted the effects of estimates of CIs in the review.

For studies using one or more treatment groups (multi‐arm studies), where appropriate, we combined groups to create a single pair‐wise comparison using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. For primary outcomes, we planned to explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis. In this version of the review, too few studies contributed data to allow this planned analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we have attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if an I² is greater than 30% and either T² is greater than zero, or there is a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

In this version of the review insufficient studies contributed data to allow us to explore possible reporting biases. In updates, if more data become available, for those outcomes where there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we plan to investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2012). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies estimate the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials examined the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar. If we considered that there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects would differ between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary provided that an average treatment effect was considered clinically meaningful. If the average treatment effect was not considered to be clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials.

Where we used random‐effects analyses, we have presented the results as the average treatment effect with its 95% CI, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we had identified substantial heterogeneity, we planned to investigate it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses.

We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

Younger women versus older women (as defined by trial authors).

Low‐resource versus high‐resource settings.

Primigravidae versus multigravidae.

Women as the active initiators of support versus women as the passive recipients of support.

Health‐professional support versus lay support.

Timing and duration of telephone‐based support.

We planned to use the following outcomes in subgroup analysis: maternal satisfaction and maternal anxiety/stress. In this version of the review, due to lack of data we did not carry out this planned analysis. In updates if more data become available, we will assess differences between subgroups by interaction tests.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analyses as appropriate to evaluate the effect of trial quality; in this version of the review we did not carry out this analysis due to the paucity of data for most outcomes.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (23 January 2013) identified 86 reports representing 62 different studies (several studies resulted in more than one publication). Altogether, 29 trials met the inclusion criteria, 29 studies were excluded, and four trials are still ongoing (Dennis 2012; Evans 2012; Moniz 2012; Patel 2011).

Included studies

Twenty‐nine trials met the inclusion criteria for the review. The trials all included pregnant women or women in the early postpartum period (up to six weeks postpartum) and examined interventions that involved telephone support. Trials that included telephone support as one part of more complex interventions were only included if we judged that the telephone support was the key difference between women in the intervention and control groups, or if women in control groups received all other parts of complex interventions apart from telephone support. Two trials, which were otherwise eligible for inclusion, did not report results by randomisation group or the data were not presented in a way that allowed us to include results in the data and analysis tables (Parker 2007; Stotts 2002). We have set out more information about these trials in Characteristics of included studies tables but these studies are not discussed further in the results below. Results are therefore based on 27 trials including a total of more than 12000 women which contribute data to the review.

The included trials were published between 1982 and 2012; 13 of the trials were carried out in the USA (Boehm 1996; Bullock 2009; Bunik 2010; Di Meglio 2010; Donaldson 1988; Ershoff 1999; Ferrara 2011; Little 2002; McBride 1999; Moore 1998; Pugh 2002; Rasmussen 2011; Rigotti 2006), five in Canada (Bloom 1982; Dennis 2002; Dennis 2009; Johnson 2000; Mongeon 1995), two in Australia (Bryce 1991; Milgrom 2011) two in England (Naughton 2012; Smith 2008) and one each in Thailand (Jareethum 2008), New Zealand (Bullock 1995), Italy (Simonetti 2012), Zanzibar (Lund 2012) and Scotland (Hoddinott 2012).

All of the trials recruited women during pregnancy or the early postpartum period. Many of the trials recruited women from high‐risk groups (e.g. women at high risk of depression, or women who were smokers) and the intervention was specifically designed to address the risk factor.

Interventions

Nine of the trials were designed to support breastfeeding women (Bloom 1982; Bunik 2010; Dennis 2002; Di Meglio 2010; Hoddinott 2012; Mongeon 1995; Pugh 2002; Rasmussen 2011; Simonetti 2012). In all but the Rasmussen 2011 trial, women were recruited after the birth of the baby and interventions took place during the postnatal period. In the trials by Bloom 1982, Bunik 2010, Hoddinott 2012, Rasmussen 2011 and Simonetti 2012 the telephone support intervention was carried out by healthcare professionals (nurses, midwives or lactation consultants), whereas in the Dennis 2002, Di Meglio 2010 and Mongeon 1995 trials, the telephone intervention was delivered by trained volunteers (in the Di Meglio 2010 study both participants and volunteers were under 20 years of age). In the Pugh 2002 trial telephone support was from both nurses and peer counsellors.

Six studies aimed to encourage women to quit smoking, or to prevent smoking relapse (Bullock 2009; Ershoff 1999; Johnson 2000; McBride 1999; Naughton 2012; Rigotti 2006). In three of these studies the interventions were provided during pregnancy only (Bullock 2009; Ershoff 1999; Naughton 2012), while in McBride 1999 and Rigotti 2006 telephone support started in pregnancy and continued after the birth of the baby. Johnson 2000 focused on the prevention of smoking relapse in the postnatal period. In the Naughton 2012 trial, women received automated text messages encouraging smoking cessation, whereas in the other trials telephone support was from health professionals (nurses or trained counsellors).

Two trials focused specifically on women at high risk of postnatal depression (Dennis 2009; Milgrom 2011). In both cases the telephone support intervention was delivered by health professionals. In the Dennis 2009 trial women received the support intervention during the postnatal period only. Participants in the Milgrom 2011 study were assessed during pregnancy and those at high risk of depression and randomised to the intervention group received supportive telephone calls from a psychologist during pregnancy and the early postpartum period.

Two studies focused on women who were at high risk of preterm birth (Boehm 1996; Bryce 1991) and in both of these trials women received phone calls during pregnancy from trained staff. In the Boehm 1996 trial calls were made daily to assess symptoms and provide support. In the Bryce 1991 trial, women received supportive phone calls between antenatal visits, which aimed to provide emotional support rather than education.

Ferrara 2011 recruited women at high risk of gestational diabetes and the intervention aimed to increase exercise, encourage a healthy diet and promote breastfeeding; the intervention was delivered by professionals including dieticians and lactation consultants.

Six of the studies examined more general telephone support interventions. In the trial by Jareethum 2008, women received text messages giving advice on health in pregnancy and signs and symptoms which were tailored for gestational age. In the trial by Moore 1998, women aged under 18 or at high risk received general advice from a nurse on health during pregnancy. Little 2002 also focused on high‐risk women with support during the antenatal period only from nurses. Similarly, Smith 2008 examined telephone support from midwives during the antenatal period. In the Bullock 1995 trial, women received general advice and support during both the antenatal and postnatal periods from trained volunteers. In a cluster‐randomised trial in Zanzibar, women in the intervention group received automated mobile phone messages tailored to gestational age; messages provided general health education and encouraged women to attend antenatal care appointments and to seek skilled attendance for the birth (Lund 2012). Finally, the Donaldson 1988 trial focused on the early postnatal period, and again women received general advice and support from nurse educators.

Excluded studies

Several other studies were considered but excluded for various reasons. These included recruitment to the trial beyond six weeks postpartum (Dennis 2003; Edwards 1997; Fjeldsoe 2010; Kersten‐Alvarez 2010; van Doesum 2008), telephone support not being the trial intervention (Bartholomew 2011; Brooten 1994; Haider 1997; Janssen 2006; Langer 1993; Lewis 2011; Sink 2001), or only a small component of the overall intervention (Brooten 2001; Frank 1986; Katz 2011; Norbeck 1996; Oakley 1990), or the telephone support was provided to both study groups (Alemi 1996; Gagnon 2002; Iams 1988). Trials that evaluated the frequency of telephone support (Rush 1991), or as a screening tool (Steel O'Conner 2003), or the intervention included several elements in addition to telephone support (Gjerdingen 2009) were also excluded. In addition, we excluded studies based on trial methodology; two were quasi‐randomised (Jang 2008; Lando 2001), one used alternate allocation (Chen 1993), and the remaining trial was not randomised (Ershoff 2000). The two remaining reports were trial protocols (Caramlau 2011; Stomp‐van den Berg 2007). Details of excluded studies are given in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Risk of bias in included studies

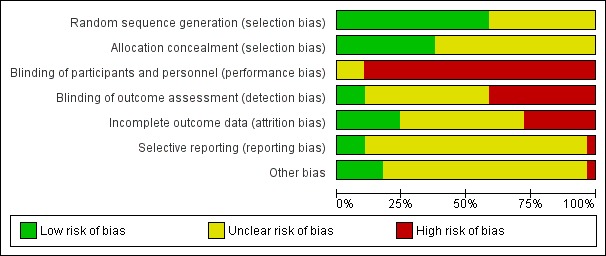

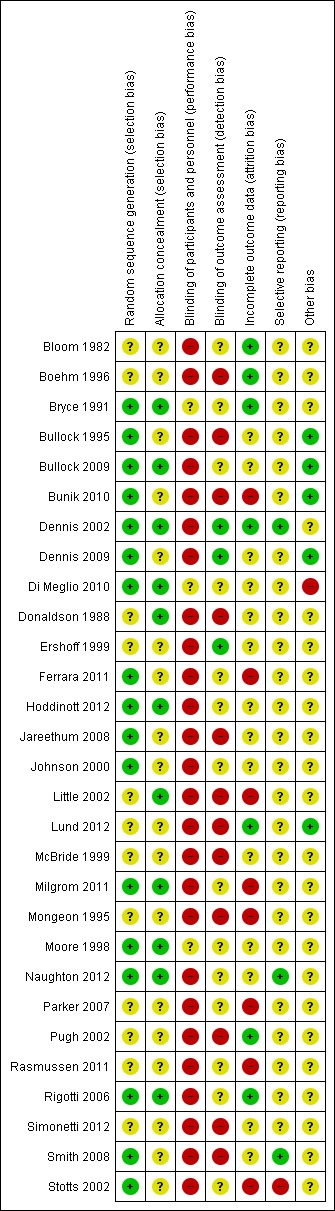

Overall, the studies were of mixed methodological quality. We have summarised findings for risk of bias for each bias domain in Figure 1, and in Figure 2 we have set out 'Risk of bias' assessments for each included study.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We assessed that 16 of the 27 trials used methods that were of low risk of bias for generation of the randomisation sequence (Bryce 1991; Bullock 1995; Bullock 2009; Bunik 2010; Dennis 2002; Dennis 2009; Di Meglio 2010; Ferrara 2011; Hoddinott 2012; Jareethum 2008; Johnson 2000; Milgrom 2011; Moore 1998; Naughton 2012; Rigotti 2006; Smith 2008). These trials used methods such as computer‐generated randomisation, random number tables, or web‐based or telephone external randomisation services. The remaining trials used methods that were either not described or descriptions were not clear (Bloom 1982; Boehm 1996; Donaldson 1988; Ershoff 1999; Little 2002; Lund 2012; McBride 1999; Mongeon 1995; Pugh 2002; Rasmussen 2011; Simonetti 2012). No studies used methods that we assessed as inadequate.

Eleven studies used methods of concealing group allocation at the point of randomisation, which we judged were at low risk of bias such as allocations concealed in opaque, sealed and numbered envelopes or external services (Bryce 1991; Bullock 2009; Dennis 2002; Di Meglio 2010; Donaldson 1988; Hoddinott 2012; Little 2002; Milgrom 2011; Moore 1998; Naughton 2012; Rigotti 2006). The remaining studies did not describe methods or methods were unclear with regard to risk of bias for this domain.

Blinding

Blinding women or those delivering support for this type of intervention is not easy to achieve, and this lack of blinding may have an important impact depending on what sort of outcomes were measured, and for self‐report measures there may have been a high risk of response bias. For outcome assessment, blinding may be more feasible. Twelve of the studies did not mention any attempt to blind those collecting outcome data (Boehm 1996; Bullock 1995; Bunik 2010; Donaldson 1988; Jareethum 2008; Little 2002; Lund 2012; McBride 1999; Mongeon 1995; Pugh 2002; Simonetti 2012, Smith 2008). In 11 studies, trial authors said that outcome assessors were blind to group allocation (Bloom 1982; Bryce 1991; Dennis 2002; Dennis 2009; Di Meglio 2010; Ferrara 2011; Hoddinott 2012; Johnson 2000; Milgrom 2011; Moore 1998; Rasmussen 2011). However, it is possible that women revealed their allocation to interviewers, and so it is difficult to judge whether these attempts at blinding were successful in practice. In only one trial did the author describe attempts to test the effectiveness of blinding, and in this case it appeared that most of those collecting outcome data were unaware of randomisation group (Dennis 2009). In four trials where the primary outcome was smoking cessation outcome assessment was by cotinine analysis, and it is likely that staff carrying out tests were blind to group allocation (Bullock 2009; Ershoff 1999; Naughton 2012; Rigotti 2006).

Incomplete outcome data

Follow‐up was a problem in several of the included trials. In seven studies sample attrition was low and most of those randomised provided outcome data (Boehm 1996; Bloom 1982; Bryce 1991; Dennis 2002; Lund 2012; Pugh 2002; Rigotti 2006). In 14 trials the impact of sample attrition was not clear (Bullock 1995; Bullock 2009; Dennis 2009; Di Meglio 2010; Donaldson 1988; Ershoff 1999; Hoddinott 2012; Jareethum 2008; Johnson 2000; McBride 1999; Moore 1998; Naughton 2012; Simonetti 2012; Smith 2008). For some outcomes even relatively low attrition can mean that results are difficult to interpret (Higgins 2011). Sample attrition is not generally random, and it is possible that women at most risk of poor outcomes were less likely to respond (e.g. women at risk of depression, or who continue smoking, or abandon breast feeding). In four of the trials there were high levels of attrition, or there were missing data for some outcomes; in the Bunik 2010 trial, women in the intervention group who did not receive the intervention as planned were excluded from the analysis (27% loss to follow‐up). For some outcomes only 71/175 of the women randomised provided data in the trial by Little 2002. In the Rasmussen 2011 study loss to follow‐up was 20%, in Mongeon 1995 there were 30% missing data for some outcomes, and finally in the Milgrom 2011 trial, complete data were available for only 62% of those randomised, although there was an intention‐to‐treat analysis for the primary outcome. In Ferrara 2011, the loss in the intervention and control groups was not balanced (10% of controls were lost to follow‐up compared with 20% of the intervention group).

Selective reporting

Assessing outcome reporting bias is very difficult without access to study protocols and most of the studies were assessed as unclear for outcome reporting bias. Several authors provided us with additional information or data (Bullock 2009; Dennis 2009; Hoddinott 2012; Little 2002; Lund 2012; Milgrom 2011; Rigotti 2006; Smith 2008).

Other potential sources of bias

There were no obvious other sources of bias in most of the studies. Some baseline imbalance between groups was reported by Dennis 2002, Hoddinott 2012, Little 2002, Rasmussen 2011 and Rigotti 2006; even where baseline imbalance was not statistically significant it may affect the interpretation of results. In the trials by Bunik 2010, Di Meglio 2010, Milgrom 2011 and Smith 2008, it was reported that many women in the intervention group did not receive, or received only a small part of the intervention; this again means that it was difficult to interpret any differences, or lack of differences identified between groups.

Effects of interventions

Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support (27 studies with 12,256 women)

All of the studies included in the review compared telephone support with routine care/no telephone support. We have included results from 24 studies in the meta‐analyses, results from a cluster‐randomised trial are set out in an additional table (Lund 2012), and results from a further two studies are discussed in the text (Bunik 2010; Di Meglio 2010).

Primary outcomes

Maternal satisfaction with support during pregnancy and the first six months postpartum (as defined by trial authors)

Two studies reported mean satisfaction scores with care during pregnancy; Little 2002 and Jareethum 2008 reported scores for overall satisfaction with care, although in the Jareethum 2008 trial women were not asked about their care until after the birth. Compared with those receiving telephone support, women in the control group had lower mean levels of satisfaction (standardised mean difference (SMD) 1.16, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.79 to 1.54; two studies with 132 women) (Analysis 1.1). In addition, Mongeon 1995 reported the number of women in each group who said they were not satisfied with their care; there were no clear differences between groups (risk ratio (RR) 0.84, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.64; one study with 181 women) (Analysis 1.2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 1 Maternal satisfaction with support during pregnancy.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 2 Maternal satisfaction with support in postnatal period (number feeling they were not supported).

Two trials reported mean scores for satisfaction with support in the postnatal period; women who received telephone support had higher mean satisfaction scores (SMD 0.54, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.91; two studies with 119 women) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 3 Maternal satisfaction with support in postnatal period.

Maternal anxiety (measures as defined by trial authors)

Mean scores for anxiety during pregnancy were reported in two studies (Jareethum 2008; Smith 2008), although women rated their anxiety during pregnancy during the early postpartum period in the Jareethum 2008 study, which makes results from this trial difficult to interpret. There were no clear differences between groups for this outcome (SMD ‐0.09, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.11; two studies with 386 women) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 4 Maternal anxiety in pregnancy.

The number of women with anxiety in the postnatal period (12 weeks postpartum) was reported in two trials (Dennis 2009; Milgrom 2011); there were no clear differences between those receiving the telephone intervention versus controls (average RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.46; two studies with 702 women) (Analysis 1.5). Anxiety was defined in different ways in these two trials. Dennis 2009 reported the number of women with STAI (State/Trait Axiety Inventory) scores greater than 44, whereas Milgrom 2011 reported on the number with DASS (Depression and Anxiety Short Scale) anxiety scores greater than, or equal to eight. These differences in measurement tools may account for the high statistical heterogeneity observed for this outcome (I2 = 69%) (Analysis 1.5). Mean scores for maternal anxiety in the postnatal period were reported in three trials; again, there were differences between studies in measurement tools and when outcomes were recorded. Anxiety scores were, on average, slightly lower in the intervention group (SMD ‐0.15, 95% CI ‐0.27 to ‐0.02; three studies with 952 women) (Analysis 1.6).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 5 Maternal anxiety (number of women with anxiety) at last postpartum assessment.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 6 Maternal anxiety in postnatal period.

One study reported on the number of women with high scores (260 or more) on the Parenting Stress Index at three months postpartum. Women who had received telephone support were less likely to have high stress scores; the difference between groups approached statistical significance (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.09 to 1.00, one study with 94 women, P = 0.05) (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 7 Parenting stress: high score on parenting stress index at 12 weeks postpartum.

Secondary outcomes

Maternal outcomes

Mother‐infant attachment

This outcome was not reported in any of the included trials.

General health (e.g. as defined by standardised measures such as general health questionnaires)

This outcome was reported in one of the included trials; Donaldson 1988 collected data on the number of women rating their general health as good or very good at six weeks postpartum. The majority of women in both groups reported good general health (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.21, one study with 37 women) (Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 8 General health: general health at 8 weeks postpartum rated as good or very good.

Mortality and serious morbidity (e.g. perineal haematoma or deep surgical infection)

This outcome was not reported in any of the included trials.

Health service utilisation (presentation/attendance at clinics, accident and emergency departments or general practices)

Four studies reported maternal health service utilisation during pregnancy, the birth, or the postnatal period. Studies focused on different aspects of care and many of the data on particular outcomes were derived from only one or two studies. Overall, there was no strong evidence of differences between groups for health service utilisation.

Boehm 1996 and Smith 2008 reported the mean number of antenatal visits; there were no clear differences between women receiving or not receiving telephone support (mean difference (MD) 0.24. 95% CI ‐0.26 to 0.74; two studies 563 women) (Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 10 Health service utilisation: mean number of antenatal visits.

Smith 2008 reported on antenatal hospital admissions; there were no clear differences between groups (RR 1.61, 95% CI 0.95 to 2.75; one study with data for 554 women) (Analysis 1.11).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 11 Health service utilisation: admission to hospital during pregnancy.

Boehm 1996 provided data on mean length of hospital stay at the time of the birth; there was no strong evidence that the average length of stay varied by randomisation group (MD 0.81, 95% CI ‐1.56 to 3.18; one study with 42 women) (Analysis 1.12).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 12 Health service utilisation: maternal length of hospital stay.

The mean number of contacts with community midwives and health visitors up to eight weeks postpartum were described by Hoddinott 2012. There was no significant evidence of differences in the number of contacts with either type of health professional (MD ‐0.40, 95 % CI ‐1.46 to 0.66, and MD ‐0.50, 95% CI ‐1.33 to 0.33, respectively; one study with data for 58 women) (Analysis 1.13).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 13 Health service utilisation up to 8 weeks postpartum (mean contacts).

Dennis 2009 did not reveal statistically significant differences between women in the two randomised groups in terms of the mean number of health service contacts up to six months postpartum (MD ‐ 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.28 to 0.22; one study with 600 women) (Analysis 1.14).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 14 Health service utilisation in postnatal period (last assessment up to 6 months) Mean number of contact.

Postpartum depression (measures as defined by author, e.g. the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS))

Dennis 2009 reported on the number of women with a diagnosis of depression at three months postpartum following a telephone intervention to support women at high risk of depression; there was no clear difference between groups (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.23; one study, data for 612 women) (Analysis 1.15). The number of women with scores on the EPDS greater than 12, and those with scores of 14 or more on the Becks Depression scale, (both indicating a high risk of depression) were reported by Dennis 2009 and Milgrom 2011 respectively. Pooled results suggest that women receiving telephone support interventions were less likely to have scores above the cut‐offs denoting high risk at three months postpartum (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.70; two studies with data for 701 women) (Analysis 1.16). Dennis 2009 also reported mean scores on the EPDS at three months, and average scores were lower in the group receiving telephone support (MD ‐ 0.96, 95% CI ‐1.75 to ‐0.17; one study 612 women) (Analysis 1.17).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 15 Postnatal depression: clinical diagnosis of depression at 3 months postpartum.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 16 Postnatal depression symptoms (high risk on scale) at 3 months postpartum.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 17 Postnatal depression symptoms (mean score on EPDS) at 3 months postpartum.

Positive behaviour change (as defined by trial authors, e.g. smoking reduction)

Trials reported on several different types of behavioural change following telephone support interventions. Broadly, depending on the focus of the intervention, behaviour change was examined for smoking (cessation or relapse); breastfeeding (any or exclusive breastfeeding), alcohol consumption and general lifestyle changes (e.g. increase in exercise).

Seven trials reported on one or more outcomes relating to smoking (Bullock 1995; Bullock 2009; Ershoff 1999; Johnson 2000; McBride 1999; Naughton 2012; Rigotti 2006). Cotinine‐validated smoking cessation in pregnancy was reported in four trials; there was no strong evidence that women receiving telephone support interventions were less likely to be smoking at the end of pregnancy (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.44; four trials with data for 1361 women) (Analysis 1.18). Similarly, there was no strong evidence that interventions reduced the number of women themselves reporting that they had stopped smoking at the end of pregnancy (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.23; four studies with data for 1638 women) (Analysis 1.19). Two trials reported cotinine‐validated results for women who had stopped smoking (or had not relapsed) in the early postpartum period; there was no strong evidence that the intervention was effective (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.32, two studies with 949 women) (Analysis 1.20); similarly, self‐reported smoking cessation was not significantly different in women receiving or not receiving telephone support (RR 1.28, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.73, two studies with data for 670 women) (Analysis 1.21).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 18 Positive behaviour change: stopped smoking by the end of pregnancy (cotinine validated).

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 19 Positive behaviour change: stopped/not smoking by the end of pregnancy (self‐report).

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 20 Positive behaviour change: stopped smoking at last postpartum assessment (cotinine validated).

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 21 Positive behaviour change: stopped smoking at last postpartum assessment (self‐report).

Eight trials reported outcomes relating to breastfeeding (any, and or exclusive breastfeeding) (Bloom 1982; Dennis 2002; Ferrara 2011; Hoddinott 2012; Mongeon 1995; Pugh 2002; Rasmussen 2011; Simonetti 2012). There was no clear evidence that interventions had a positive effect on the number of women breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum although results were inconsistent between trials (average RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.12, five trials with 735 women, I2 69%) (Analysis 1.22). At six months postpartum it appeared that results favoured the intervention group, with those women receiving telephone support being more likely to be still breastfeeding (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.38, five trials with 691 women) (Analysis 1.23).

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 22 Any breastfeeding at up to 6 weeks postpartum.

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 23 Any breastfeeding up to 6 months postpartum.

Four trials examined exclusive breastfeeding at four to eight weeks postpartum. Three of the four trials reported results favouring the group receiving telephone support; however, results were inconsistent and there was high heterogeneity for this outcome. Pooled results showed no statistically significant difference between groups (average RR 1.27, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.83, four trials with 465 women) (Analysis 1.24). Three trials examined exclusive breastfeeding at three to six months postpartum; pooled results showed a statistically significant difference between groups, with women who had received the support intervention being more likely to be exclusively breastfeeding (RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.93, three trials with 411 women) (Analysis 1.25).

1.24. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 24 Exclusive breastfeeding at 4‐8 weeks.

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 25 Exclusive breastfeeding at 3 ‐6 months.

Bloom 1982 reported that mean breastfeeding duration was 7.6 days longer for women receiving the telephone intervention and the difference between groups approached statistical significance (5% CI 0.06 to 15.14, P = 0.05, 99 women) (Analysis 1.26). Duration of breastfeeding was also measured by Di Meglio 2010 who reported that "duration did not differ significantly between the intervention group and the control group (median, 77 versus 35 days; hazard ratio 0.71, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.30, P = 0.26)." (Data not shown in data and analysis tables.) Bunik 2010 also reported breastfeeding duration and stated that by one month postpartum 71% of women in both the intervention and control group had introduced infant formula (data not shown).

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 26 Mean breastfeeding duration (any breastfeeding) in days.

Dennis 2002 reported mean scores for women's satisfaction with their experience of breastfeeding their babies (this was not one of our pre‐specified outcomes); women receiving the intervention were not shown to be significantly more satisfied (MD 0.83, 95% CI ‐0.60 to 2.26, 256 women) (Analysis 1.38).

1.38. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 38 Non prespecified outcome: satisfaction with infant feeding experience.

Bullock 1995 reported the number of women who were not consuming alcohol in late pregnancy; there were no clear differences between the intervention and control groups in the number of women who reported that they had not consumed any alcohol in the last month (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.20, 122 women) (Analysis 1.27). Ferrara 2011 provided data on the number of women who achieved weight goals at six months postpartum; there was no strong evidence that the intervention had a positive effect (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.67 to 2.17, 189 women) (Analysis 1.28).

1.27. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 27 Positive behaviour change: not drinking in the last month (late pregnancy).

1.28. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 28 Positive behavioural change: women meeting postpartum weight goals at 6 months postpartum.

Infant outcomes

Preterm birth/low birthweight

Four studies provided data on the number of preterm births (before 37 weeks' gestation). Although the intervention was associated with a decrease in the number of preterm births the difference between groups was not statistically significant (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.08, 3992 women) (Analysis 1.29). Boehm 1996 reported the mean gestational age at delivery which was identical in the two groups (MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐1.49 to 1.49, 42 women) (Analysis 1.30).

1.29. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 29 Preterm birth < 37 weeks.

1.30. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 30 Mean gestational age at delivery.

Three trials provided data on the number of low birthweight babies (less than 2500 g); and while results slightly favoured the intervention group, the difference was not statistically significant (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.07, 3862 women) (Analysis 1.31). There were no clear differences between groups for mean infant birthweight (MD ‐42.11g, 95% CI ‐130.36 to 46.14, two trials with 592 women) (Analysis 1.32).

1.31. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 31 Low birthweight < 2500 g.

1.32. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 32 Mean birthweight.

Infant developmental measures (physical and cognitive as defined by trial authors)

Outcomes relating to infant development were not reported in included trials.

Neonatal/infant mortality and major neonatal/infant morbidity (as defined by trial authors, e.g. prolonged admission to special care baby unit)

Only one trial provided data on neonatal and infant mortality; the number of deaths was higher where woman had received telephone support but the difference between groups was not statistically significant (RR 1.40, 95% CI 0.82 to 2.42, 1884 women) (Analysis 1.34).

1.34. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 34 Neonatal/infant mortality..

Two studies reported on admissions to neonatal intensive care units; there appeared to be fewer admissions if women had received telephone support (0.71, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.97; two studies, 2403 women) (Analysis 1.35).

1.35. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 35 Major neonatal/infant morbidity/admission to NICU.

Service outcome

Intervention cost

This outcome was not reported.

Non‐prespecified outcomes

One study used a cluster‐randomised design, and 24 healthcare facilities in Zanzibar were randomised (Lund 2012). The study reported results for 2550 women. The primary outcome in this study was the number of women with skilled attendance at the birth. Results for this outcome are set out in Table 1. Overall, 60% of women in the group receiving the mobile phone support intervention had skilled help at the birth compared with 47% of women in the control group (unadjusted data). The difference between groups was almost all due to the increased number of women in the intervention group living in urban areas having skilled attendance; the intervention did not seem to make much difference for women living in rural areas where more than half of the women in both groups had no skilled help at the birth. Other outcomes from this trial will be reported in future papers and we hope to include them in updates of the review.

Other non‐prespecified outcomes

Three studies reported on infant health service utilisation. Boehm 1996 reported on infant length of hospital stay following the birth; there were no clear differences between groups (MD 0.80, 95% CI ‐0.31 to 1.91, 42 women) (Analysis 1.36). Pugh 2002 described the number of infant healthcare visits for a sample of 41 women; the babies of women who received telephone support were reported to receive a mean of 1.4 fewer healthcare visits (3.6 versus five visits, 95% CI ‐2.57 to ‐0.23) (Analysis 1.37). Bunik 2010 reported that by one month postpartum, similar numbers of babies in the intervention and control group had attended well‐baby clinic visits, however, 25% of babies in the intervention group and 36% in the control group had had at least one sick visit (data not shown).

1.36. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 36 Non‐prespecified: infant length of hospital stay.

1.37. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 37 Non prespecified: mean number of infant healthcare visits.

Boehm 1996 reported on the diagnosis of preterm labour; there was no evidence of differences between groups (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.50 to 2.01) (Analysis 1.40).

1.40. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 40 Non prespecified outcome: diagnosis of preterm labour.

Three studies reported the number of women having caesarean births; overall numbers were similar in intervention and control groups (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.34, 2480 women) (Analysis 1.39).

1.39. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support, Outcome 39 Caesarean section.

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this review we have included data from 27 randomised trials with more than 12,000 women. All of the trials examined telephone support versus usual care (no additional telephone support). We did not identify any trials comparing different modes of telephone support (for example, text messaging versus one‐to‐one calls). All but two of the trials were carried out in high‐resource settings. The majority of studies examined support provided via telephone conversations between women and health professionals although a small number of trials included telephone support from peers. In three trials women received automated text messages. Many of the interventions aimed to address specific health problems and collected data on behavioural outcomes such as smoking cessation and relapse (seven trials) or breastfeeding continuation (eight trials). Other studies examined support interventions aimed at women at high risk of postnatal depression (two trials) or preterm birth (two trials); the rest of the interventions were designed to offer women more general support and advice.

For most of our pre‐specified outcomes few studies contributed data, and many of the results described in the review are based on findings from only one or two studies. Overall, results were inconsistent and inconclusive although there was some evidence that telephone support may be a promising intervention. Results suggest that telephone support may increase women's overall satisfaction with their care during pregnancy and the postnatal period; although results for both periods were derived from only two studies. There was no consistent evidence confirming that telephone support reduces maternal anxiety during pregnancy or after the birth of the baby although results on anxiety outcomes were not easy to interpret as data were collected at different time points and using a variety of measurement tools. One trial with a small sample size suggested that support may reduce parenting stress, although the difference between groups was not statistically significant. There was evidence from two trials that women who received support had lower mean depression scores in the postnatal period although there was no clear evidence that women who were supported were less likely to have a diagnosis of depression. Results from trials encouraging breastfeeding through telephone support were also inconsistent, although for longer‐term breastfeeding outcomes (up to six months postpartum), results suggested that women receiving telephone support were more likely to continue any breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding for longer. There was no strong evidence that women receiving telephone support interventions were less likely to be smoking at the end of pregnancy or during the postnatal period, nor was it clear that interventions reduced smoking relapse.

For infant outcomes, such as preterm birth and infant birthweight, there was little evidence overall. Where evidence was available, there were no clear differences between groups. Results from two trials suggest that babies whose mothers received support may have been less likely to have been admitted to neonatal intensive care unit, although it is not easy to understand the mechanisms underpinning this finding.

Results from one cluster‐randomised trial examined whether women receiving a mobile phone intervention were more likely to have skilled attendance at the birth and for women living in urban areas results favoured the intervention group; although this was not one of our prespecified outcomes skilled attendance at the birth may have an impact on both maternal and infant health outcomes. We hope to include further results from this trial in updates of the review.

Based on the limited evidence from the 27 trials that provided data for this review, there remains uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of telephone support.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The studies included in this review were from a variety of countries; however, all but two were from a high‐resourced setting. This limits the applicability of the findings, particularly as it is conceivable that telephone support has the potential for greater impact in environments where health services are unavailable or hard to access. In the postnatal period, for example, this may change the intervention from supplementary support to the only support, in some environments.

As mentioned previously, the review included trials with a variety of aims; some offering general support and others intent on improving behaviour. However, even within these trial groupings, there were variations in the choice of outcomes measured, when they were measured, and the ways in which they were measured. This made it difficult to draw meaningful conclusions. Moreover, important clinical outcomes, such as serious maternal morbidity and mother‐infant attachment, were absent from the included trials.

We had hoped to compare conversational telephone support with the use of text or instant messaging. We were unable to find any randomised controlled trials that had compared alternative modes.

Quality of the evidence

The overall methodological quality of the studies included in the review was mixed; approximately half of the trials used methods to randomise women to experimental and control groups using methods that we judged were at low risk of bias. None of the trials achieved effective blinding of women or those providing care; in four of the trials looking at smoking cessation cotinine analysis was carried out to confirm smoking status and this would be likely to be at low risk of bias for this particular outcome. However, for most outcomes there was a high risk of bias associated with the lack of blinding. Even where authors reported that outcome assessors were blinded it is possible that women revealed their allocation; only one trial author reported attempts to assess the success of blinding outcome assessors. The overall impact of sample attrition was difficult to assess; for most of the trials we judged that attrition was unclear, or that results were at high risk of bias due to loss to follow‐up.

Most of the results of this review are derived from one or two studies and several of the studies had small sample sizes; we were therefore unable to pool many of the data in meta‐analyses. There was a lack of consistency between studies in terms of the outcomes reported, and the time and way in which outcomes were measured. In addition, there was considerable diversity in terms of the aims of interventions and the way they were delivered. These differences mean that for any one outcome there were few data and most of our results were inconclusive.

Potential biases in the review process

We are aware that the review process itself may introduce bias. We took various steps to reduce bias; at least two review authors independently carried out data extraction and assessed risk of bias. If study methods or results were unclear, we attempted to contact trial authors and several authors provided additional data or clarified study methods.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This study builds on an earlier review by Dennis 2008, which had similar inclusion criteria to this review, and included 14 trials. We excluded some of the studies that were included by Dennis 2008 because we were unconvinced that the telephone support made a substantial contribution to the intervention being assessed (e.g. Brooten 2001; Frank 1986). Nevertheless, the findings were not dissimilar. Both reviews suggest potential benefits without any evidence of harm, and both reviews recommend the need for further research in this area.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Despite some encouraging findings, there is insufficient evidence to recommend routine telephone support for women accessing maternity services, as the evidence from included trials is neither strong nor consistent. Although benefits were found in terms of reduced depression scores and increased overall satisfaction, the current trials do not provide strong enough evidence to warrant investment in resources.

Implications for research.

This review has highlighted the need for further research to assess the effects of telephone support during pregnancy and the first six weeks post birth. Further research is required to assess its application for general support of women, and for those with specific needs, such as high risk of preterm birth.

The review has raised a number of questions regarding the actual intervention. Further research is needed to explore the optimum intervention, in terms of mode of delivery (text or conversation), style of support (proactive or reactive), deliverer (health professional, trained volunteer, automated), frequency, duration and timing of delivery. A clear audit trail of intervention development should be apparent; this should include consumer input.

Standardisation of outcomes in future trials would aid synthesis and transferability. Important outcomes were absent from existing trials (maternal mortality/severe morbidity, maternal‐infant attachment and infant development); these should be considered in future studies. Furthermore, there was no information on the costs associated with telephone support; future studies should include cost effectiveness as an integral part of the trial design.

Despite a plethora of m‐health programmes implementing mobile phone support, particularly in low‐resourced settings, many of these have not yet been subjected to randomised controlled trials. This is a particular area of need.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge an earlier version of this protocol by Cindy‐Lee Dennis and Debra Creedy.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by four peers (an editor and three referees who are external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Telephone support versus any other supportive intervention, or no telephone support.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Maternal satisfaction with support during pregnancy | 2 | 132 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.79, 1.54] |

| 2 Maternal satisfaction with support in postnatal period (number feeling they were not supported) | 1 | 181 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.43, 1.64] |

| 3 Maternal satisfaction with support in postnatal period | 2 | 119 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.17, 0.91] |

| 4 Maternal anxiety in pregnancy | 2 | 386 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.09 [‐0.29, 0.11] |

| 5 Maternal anxiety (number of women with anxiety) at last postpartum assessment | 2 | 702 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.17, 1.46] |

| 6 Maternal anxiety in postnatal period | 3 | 952 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.15 [‐0.27, ‐0.02] |

| 7 Parenting stress: high score on parenting stress index at 12 weeks postpartum | 1 | 94 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.30 [0.09, 1.00] |

| 8 General health: general health at 8 weeks postpartum rated as good or very good | 1 | 37 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.72, 1.21] |

| 9 Mortality and serious morbidity | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Health service utilisation: mean number of antenatal visits | 2 | 563 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [‐0.26, 0.74] |

| 11 Health service utilisation: admission to hospital during pregnancy | 1 | 554 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.61 [0.95, 2.75] |

| 12 Health service utilisation: maternal length of hospital stay | 1 | 42 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [‐1.56, 3.18] |