Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose of this study was to examine clinical characteristics and risk factors for critically-ill patients who develop pressure injuries, and identify the proportion of validated unavoidable pressure injuries associated with the proposed risk factors for acute skin failure (ASF).

Design:

Retrospective case-control comparative study.

Subjects and Setting:

The sample comprised adult critically ill participants hospitalized in critical care units such as surgical, trauma, cardiovascular surgical, cardiac, neuro- and medical intensive care and corresponding progressive care units in five acute care hospitals within a large mid-western academic/teaching healthcare system and who were. Participants who developed hospital-acquired pressure injuries (HAPI) and patients without HAPI (controls) were included.

Methods:

A secondary analysis of data from a previous study with HAPI and matching data for the control sample without HAPI was obtained from the electronic health record. Descriptive and multivariate logistic regression analysis were conducted.

Results:

The sample comprised 475 participants; 165 experienced a HAPI and acted as cases whereas the remaining 310 acted as controls. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) mean score (23.8, 8.7% P <.001), mortality (n = 45, 27.3% P = 0.002), history of liver disease (n =28, 17%, P <.001), and unintentional loss of 10 pounds or more in one month (n = 20, 12%, P = .002) were higher in the HAPI group. Multivariate logistic regression identified participants with respiratory failure (odds ratio, OR = 3.00, 95% confidence interval, CI 1.27-7.08, P = .012), renal failure (OR=7.48, 95% CI 3.49-16.01; P <.001), cardiac failure (OR=4.50, 95% CI 1.76-11.51, P = .002), severe anemia (OR=10.89, 95% CI 3.59-33.00, P <.001), any type of sepsis (OR=3.15, 95% CI 1.44-6.90, P =.004), and moisture documentation (OR=11.89, 95% CI 5.27-26.81, P <.001) as more likely to develop a HAPI. No differences between unavoidable HAPI, avoidable HAPI, or the control group were identified based on the proposed ASF risk factors.

Conclusion:

This study provides important information regarding avoidable and unavoidable HAPI, and ASF. Key clinical characteristics and risk factors, such as patient acuity, organ failure, tissue perfusion, sepsis and history of prior pressure injury, are associated with both avoidable and unavoidable HAPI development. In addition, we were unable to support a relationship between unavoidable HAPI and the proposed risk factors for ASF. HAPI unavoidability rests with the documentation of appropriate interventions and not necessarily with the identification of clinical risk factors.

Keywords: Pressure injury, pressure ulcer, unavoidable pressure injury, unavoidable pressure ulcer, critical care, hospital-acquired pressure ulcer/pressure injury, skin failure, case-control study

Introduction

Critically ill patients often exhibit poor tissue tolerance due to hypoperfusion, inadequate tissue oxygenation, poor nutrition, and immobility; and they have a 10-fold higher risk for developing a hospital-acquired pressure injury (HAPI).1 Numerous risk factors have been associated with the development of HAPI,2,3 yet a consistent combination of risk factors that best predict the development of HAPI is not completely understood.4,5 Some risk factors are non-modifiable, and HAPI can occur in high-risk patients despite all appropriate preventive interventions having been implemented and documented. HAPI that occur despite provision of appropriate care to mitigate modifiable risk factors are referred to as being unavoidable. Critically ill patients are especially at risk for unavoidable HAPI and are cared for within critical or intensive care units specifically designated for those with complex and severe illnesses. A critical care stay is often preceded or followed by a stay in a progressive care unit. The progressive care unit is a transitional or intermediate unit and is useful when the medical condition complexity and severity worsens or stabilizes. Moreover, there is often an overlap of care between critical care and progressive care units as complexity and severity of the patients’ status varies or changes. According to the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN), as the acuity of patients continues to increase and with it the increased need for critical care beds, progressive care units are used to ease the burden for complex care of the critically ill. Therefore, patients are often admitted to progressive care with the need for an increased level of care and close observation.6

The concept of acute skin failure (ASF) has emerged as potentially related to unavoidable pressure injury.1, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Some researchers hypothesize that unavoidable pressure injuries are more likely to occur in situations where the skin is failing and studies investigating a possible association between unavoidable pressure injuries and ASF in critical care patients have been published.1, 8, 10, 11 This association has sparked a debate over whether unavoidable pressure injuries are manifestations of ASF, or if skin failure is a potentially non-modifiable risk factor for unavoidable pressure injury. However, most experts agree that while a pressure injury must have a pressure and/or shear component as its etiology, a pressure injury is not necessarily a component of ASF.7, 9 Nevertheless, accurate classification of a pressure injury as unavoidable also requires confirmation that appropriate and consistent pressure injury preventive care is provided.12

Unavoidable pressure injuries are defined as those that develop even when the provider: 1) evaluated the individual’s clinical condition and pressure injury risk factors; 2) defined and implemented interventions that are consistent with individual needs, goals and recognized standards of practice; 3) monitored and evaluated the impact of the interventions; and 4) revised the approaches as appropriate.12 Even in these conditions, a pressure injury is deemed avoidable if preventive interventions are not provided. Until recently, research examining unavoidable HAPI has been limited due to the lack of a valid and reliable instrument for identifying unavoidable pressure injuries. For this reason, the Pressure Ulcer/Injury Prevention Inventory (PUPI) was developed and tested.13 The PUPI was then used in a recent study of 165 critical/progressive care patients in which 67 (41%) patients were identified with an unavoidable pressure injury.14

Coltart and Irvine15 broadly defined skin failure as an impairment of homeostatic and skin barrier function due to a diffuse cutaneous insult. Examples of skin failure in the dermatological literature include massive burns, erythroderma, epidermolysis bullosa, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.15 Langemo and Brown9 more narrowly identified skin failure in relation to pressure injury as either acute, chronic, or end stage and described ASF as death of the skin and underlying tissue due to hypoperfusion occurring in the context of a critical illness.9 Other researchers have expanded this definition to include pressure-related injury concurrent with major organ system dysfunction.8, 10 Delmore and colleagues, defined ASF as a pressure-related injury that occurs in combination with critical illness and presents due to the hypoperfusion that occurs with organ system compromise and/or failure.8 Olshansky16 concurred that hypoperfusion makes the skin more susceptible to pressure injury but questioned whether skin failure has become an all too common term clinicians use when other organs are failing and a pressure injury develops. No universally accepted diagnostic criterion for ASF currently exists,7, 8 and ASF is not included in the International Classification of Diseases medical classification system. Based on a systematic review of the concept, Dalgleish and colleagues17 concluded that there is a substantial evidence gap in the etiology, diagnostic biomarkers, and predictors of acute skin failure. Therefore, determining distinctive characteristics of ASF and any association with pressure injury remains extremely challenging.

In a retrospective case-control study and validation analysis, Delmore and colleagues8 evaluated 522 patients and identified the following independent predictors of ASF: (1) peripheral arterial disease (PAD) (2) mechanical ventilation greater than 72 hours, (3) respiratory failure, (4) liver failure, and (5) severe sepsis/septic shock. In order to avoid misconstruing ASF from a pressure injury, the investigators stated they excluded HAPIs where nonadherence to pressure injury prevention measures were identified, but they did not employ a validated tool to objectively identify unavoidability. We sought to build on Delmore and colleagues’ research by cross-validating their proposed ASF predictive model in a sample using an objective and systematic assessment of unavoidable versus avoidable pressure injuries, the PUPI.

The conceptual framework for differentiating unavoidable from avoidable pressure injuries, developed by Cuddigan, was used to guide this study.14 The new and unique aspects of this model incorporate: (1) epidemiological evidence on pressure injury risk factors; (2) risk-based prevention strategies consistent with the 2019 Pressure Ulcer International Guideline; and, (3) guidance for determining whether the pressure injury was avoidable or unavoidable based on the implementation of appropriate risk-based interventions. The purpose of this retrospective case-control study was to examine the clinical characteristics and risk factors for critically-ill patients who developed pressure injuries and to identify the proportion of validated unavoidable pressure injuries that were associated with proposed ASF risk factors. Our aims were to: 1) compare clinical characteristics and risk factors of critically-ill patients who developed a HAPI to those who did not; 2) examine the proportion of avoidable versus unavoidable HAPI among critically ill patients with proposed ASF risk factors; and, 3) identify potential predictive ASF risk factors among critically-ill patients that differentiate avoidable versus unavoidable pressure injuries.

Methods

This was a retrospective case-control study. The study setting was a large Midwestern, Magnet designated, healthcare organization; two large academic teaching hospitals and three community hospitals. Adult patients who were hospitalized in a variety of 15 intensive care including surgical, trauma, cardiovascular surgical, cardiac, neuro- and medical intensive care and corresponding progressive care units were included in this study. Medical records were considered eligible if the patient was >18 years of age and hospitalized in a critical or progressive level of care for at least four days during 2013-2015. Both populations were included in this sample because the progressive care population in this healthcare organization is very complex and similar to many smaller hospitals’ critical care populations.

Analysis of data collected during the previous study included data from 165 patients who developed a pressure injury while hospitalized in a critical or progressive care unit; 67 (41%) of these were determined to have unavoidable pressure injuries and 98 (59%) were avoidable based on the PUPI Tool.13 For purposes of this study, we matched the HAPI group (both avoidable and unavoidable) to data from 310 patients who had not developed a pressure injury (control group) while hospitalized. Participants were matched at a 1:2 ratio based on hospitalization in either a critical or progressive care unit used as the matching variable. The matching method alleviated any imbalance between the two groups based on acuity and allowed us to use a smaller sample size by using an a priori approach (based on eligibility criteria) instead of an a posteriori, stratified approach (based on post enrollment) analysis. The matching process was conducted using PROC SQL under SAS version 9.4. Eligible participants were identified using the electronic health record (EHR), quality reports and coding mechanisms. The study was approved as exempt by the Indiana University institutional review board (5/8/2018/#1803871236) before the start of data collection.

Instruments

The PUPI was used to determine whether a pressure injury was avoidable versus unavoidable. The instrument was developed by Pittman and colleagues;13 overall content validity of the PUPI was robust with a content validity index (CVI) of 0.99. Individual item CVI scores ranging from 0.9 to 1.0. The PUPI was also found to be reliable; interrater reliability was robust with a Cohen ⱪ=1.0 with 93% agreement among raters.13 The PUPI contains four main domains, and it is comprised of 13 items that reflect the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP) definition for unavoidable pressure injuries.11 If all items are answered as yes in the PUPI, indicating all prevention interventions were appropriately performed and documented, the HAPI is identified as unavoidable. The Braden inventory worksheet is an investigator-developed data collection tool used to collect Braden Scale for Pressure Sore Risk (Braden Scale) cumulative and subscale scores and preventive interventions. The pressure injury prevention interventions correspond to each Braden subscale. Using the PUPI and the Braden Inventory, data were collected for the three days prior to the first documentation of the HAPI for the HAPI group and data collection for the control (no HAPI) group was four days post critical/progressive care admission.

Study Procedures

Data were collected using secondary data and our EHR software (Cerner, North Kansas City MO). We collected data from our electronic medical record including demographic and pertinent clinical information. In addition, Braden subscale and cumulative scores, and additional risk factors identified as significant in epidemiological studies but not included in the Braden Scale such as poor perfusion and body temperature were collected.14 We also collected data regarding additional clinical factors postulated to be associated with ASF (respiratory failure, renal failure, cardiac failure, liver failure, myocardial infarction during current admission, severe anemia, vasopressor use resulting in peripheral necrosis, peripheral artery disease (PAD), cardiac arrest during current admission, severe sepsis/septic shock, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, diabetes mellitus, and mechanical ventilation greater than 72 hours).8 For analysis purposes, we grouped the proposed ASF variables into three main domains: organ failure (respiratory, renal, cardiac, and liver failure), limited tissue perfusion (myocardial infarction during current admission, severe anemia, vasopressor use resulting in peripheral necrosis, PAD, and cardiac arrest during current admission), and sepsis continuum (sepsis, severe sepsis, septic shock, and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). Data also included diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and mechanical ventilation greater than 72 hours.

Data Analysis

Demographic characteristics were summarized. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were reported for continuous variables and differences were examined between groups (all HAPI cases vs. matched controls) by using two sample t-tests. Number and percentage were reported for categorical variables as well as the proportions were compared between two groups using chi-square tests.

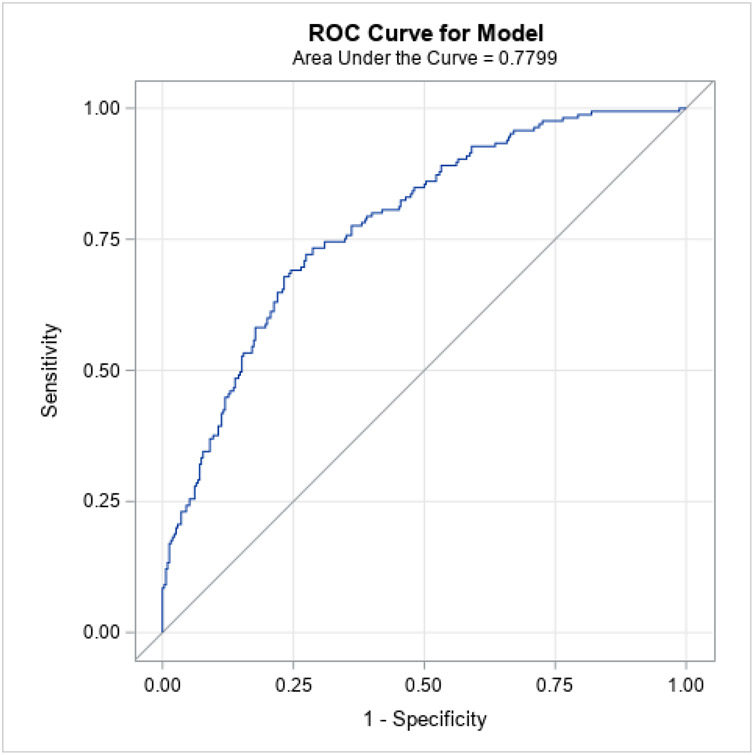

Univariate analyses were conducted for Aim 1 to evaluate the probability of developing a HAPI based on each factor. Multivariate logistic regression models were developed for variables that were significant at P < .05 and deemed clinically meaningful. The shape of a ROC curve and area under the curve (AUC) were examined to evaluate the accuracy of model.18 For Aim 2, the number and percentage were displayed for each proposed ASF risk factor by status of avoidable and unavoidable pressure injuries. The chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was employed to determine significant differences in ASF risk factors between avoidable and unavoidable HAPI. Similarly, for Aim 3, multivariate logistic regression was planned including those statistically significant ASF risk factors detected in Aim 2.

Sample Size Considerations

The sample size (N = 165) for patients with HAPI was predetermined using the secondary data set. For the control group, 310 critical/progressive care patients matched to the HAPI group were enrolled. For the binary variables, we used chi-square test to estimate the power. Given the sample size and case-control ratio, if the odds ratio (OR) is greater or equal to 2, the statistical power to detect the association is greater than 80% at .05 significance level. For continuous variables, we used two sample t-test to estimate the power. Given the sample size and HAPI-control ratio, an effect size of 0.3 will yield > 80% statistical power to detect the association at 0.05 significance level.

Results

The sample comprised 475 participants. Participants consisted of records of 165 patients who developed HAPI and 310 who acted as controls (Table 1). The mean Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score is an instrument that measures illness severity and predict mortality in critically ill patients.19 Scores range from 0 (low severity) to 71 (highest severity). The mean APACHE II score for our sample was 20.1 (SD 8.8) indicating an estimated mortality rate of 40% in non-operative patients and 30% in post-operative patients.19 The actual mortality rate in this study was 19.7%. The majority of HAPIs were deep tissue pressure injuries (n = 102, 63%), followed by stage 2 (n = 34, 21%) and unstageable (n = 25, 15%). Approximately 36% (n = 60) of the HAPIs were related to medical devices. Most of the HAPIs were on the sacrum (n = 70, 42%) or heel (n = 23, 14%).14

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Comorbid Conditions

| Characteristic | Category | HAPI Group (N = 165) |

Control Group (N = 310) |

Total (N = 475) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), Mean (SD) | 59.9 (16.4) | 56.7 (18.3) | 57.8 (17.7) | 0.060 | |

| Apache IIa, Mean (SD) | 23.8 (8.7) | 18.2 (8.3) | 20.1 (8.8) | 0.000 | |

| Mortality | No | 120 (72.7%) | 259 (84.4%) | 379 (80.3%) | 0.002 |

| Yes | 45 (27.3%) | 48 (15.6%) | 93 (19.7%) | ||

| Race | White | 132 (80.0%) | 254 (82.7%) | 386 (81.8%) | 0.307 |

| Black or African American | 22 (13.3%) | 43 (14.0%) | 65 (13.8%) | ||

| Asian | 3 (1.8%) | 5 (1.6%) | 8 (1.7%) | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | ||

| More Than One Race | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | ||

| Unknown / Not Reported | 6 (3.6%) | 5 (1.6%) | 11 (2.3%) | ||

| Sex | Female | 67 (40.6%) | 153 (49.4%) | 220 (46.3%) | 0.069 |

| Male | 98 (59.4%) | 157 (50.6%) | 255 (53.7%) | ||

| Comorbid Conditions | |||||

| Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) | No | 142 (87.1%) | 240 (86.0%) | 382 (86.4%) | 0.746 |

| Yes | 21 (12.9%) | 39 (14.0%) | 60 (13.6%) | ||

| Cerebrovascular Disease | No | 145 (89.0%) | 233 (83.5%) | 378 (85.5%) | 0.117 |

| Yes | 18 (11.0%) | 46 (16.5%) | 64 (14.5%) | ||

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | No | 124 (76.1%) | 211 (75.9%) | 335 (76.0%) | 0.967 |

| Yes | 39 (23.9%) | 67 (24.1%) | 106 (24.0%) | ||

| Diabetes Mellitus | No | 117 (71.8%) | 196 (70.3%) | 313 (70.8%) | 0.733 |

| Yes | 46 (28.2%) | 83 (29.7%) | 129 (29.2%) | ||

| Dementia | No | 161 (98.8%) | 266 (96.0%) | 427 (97.0%) | 0.145 |

| Yes | 2 (1.2%) | 11 (4.0%) | 13 (3.0%) | ||

| Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) | No | 159 (97.5%) | 271 (98.9%) | 430 (98.4%) | 0.432 |

| Yes | 4 (2.5%) | 3 (1.1%) | 7 (1.6%) | ||

| Hemiplegia/ Paraplegia | No | 161 (98.8%) | 271 (98.5%) | 432 (98.6%) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 2 (1.2%) | 4 (1.5%) | 6 (1.4%) | ||

| Liver Disease | No | 135 (82.8%) | 258 (93.5%) | 393 (89.5%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 28 (17.2%) | 18 (6.5%) | 46 (10.5%) | ||

| Myocardial Infarction (MI) | No | 144 (88.3%) | 250 (91.2%) | 394 (90.2%) | 0.325 |

| Yes | 19 (11.7%) | 24 (8.8%) | 43 (9.8%) | ||

| Malignancy | No | 139 (85.3%) | 221 (77.5%) | 360 (80.4%) | 0.047 |

| Yes | 24 (14.7%) | 64 (22.5%) | 88 (19.6%) | ||

| Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD) | No | 159 (97.5%) | 273 (99.3%) | 432 (98.6%) | 0.201 |

| Yes | 4 (2.5%) | 2 (0.7%) | 6 (1.4%) | ||

| History of Peripheral Vascular Disease (PAD) | No | 152 (93.3%) | 264 (95.7%) | 416 (94.8%) | 0.275 |

| Yes | 11 (6.7%) | 12 (4.3%) | 23 (5.2%) | ||

| Renal Disease | No | 134 (82.2%) | 227 (82.5%) | 361 (82.4%) | 0.929 |

| Yes | 29 (17.8%) | 48 (17.5%) | 77 (17.6%) | ||

| Rheumatic Diseases | No | 161 (98.8%) | 273 (99.6%) | 434 (99.3%) | 0.559 |

| Yes | 2 (1.2%) | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (0.7%) | ||

| Total Number of Comorbidities, Mean (SD) | 1.5 (1.2) | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.5 (1.3) | 0.506 | |

| Smoker | Current | 33 (22.0%) | 83 (28.7%) | 116 (26.4%) | 0.309 |

| Past | 49 (32.7%) | 89 (30.8%) | 138 (31.4%) | ||

| Never | 68 (45.3%) | 117 (40.5%) | 185 (42.1%) | ||

| History of Pressure Injury | No | 114 (69.1%) | 60 (19.9%) | 174 (37.3%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 18 (10.9%) | 2 (0.7%) | 20 (4.3%) | ||

| Unknown | 33 (20.0%) | 239 (79.4%) | 272 (58.4%) | ||

Aim 1: Characteristics of Cases who developed a HAPI versus Controls who did not

Analysis revealed clinically relevant differences among demographic characteristics and comorbid condition of patients who developed HAPI group versus control group. The APACHE II mean (SD) score was higher (worse) in the HAPI group compared to the control group (23.8, SD 8.7 versus 18.2, SD 8.3, P = .000), and the actual mortality was higher in the HAPI group (n= 45, 27%) than the control group (n= 48, 16%, P =.002). In addition, history of a previous pressure injury (11% versus 0.7%, P <.001) and history of liver disease (17% versus 7%, P <.001) were higher in the HAPI group than in the control group.

The HAPI group demonstrated significantly higher (P <.001) proportions of proposed ASF domains of organ failure (respiratory, renal, cardiac, and liver), mechanical ventilation (greater than 72 hours), limited tissue perfusion (severe anemia), and sepsis continuum (sepsis, severe sepsis, septic shock, and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (P =.014) than did controls. However, there was no statistical difference between groups in the proportions of limited tissue perfusion variables of myocardial infarction during current admission, vasopressor use with peripheral necrosis, PAD, and cardiac arrest during current admission. Furthermore, there was no difference between groups in the proportion of patients with diabetes (P =.129). See Table 2.

Table 2:

Proposed Acute Skin Failure Variables by Domain

| ASF Domain (bolded)/Risk Factor |

Category | HAPI (N = 165) |

Control (N = 310) |

Total (N = 475) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organ Failure | |||||

| Any Type Organ Failure | No | 9 (5.5%) | 161 (51.9%) | 170 (35.8%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 156 (94.5%) | 149 (48.1%) | 305 (64.2%) | ||

| Respiratory Failurea | No | 32 (19.4%) | 187 (60.3%) | 219(46.1%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 133 (80.6%) | 123 (39.7%) | 256 (53.9%) | ||

| Renal (Acute or Chronic) Failurea | No | 61 (37.0%) | 266 (85.8%) | 327 (68.8%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 104 (63.0%) | 44 (14.2%) | 148 (31.2%) | ||

| Cardiac Failurea | No | 125 (75.8%) | 283 (91.3%) | 408 (85.9%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 40 (24.2%) | 27 (8.7%) | 67 (14.1%) | ||

| Liver Failurea | No | 145 (87.9%) | 303 (97.7%) | 448 (94.3%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 20 (12.1%) | 7 (2.3%) | 27 (5.7%) | ||

| Limited Tissue Perfusion | |||||

| Any Type | No | 110 (66.7%) | 278 (89.7%) | 388 (81.7%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 55 (33.3%) | 32 (10.3%) | 87 (18.3%) | ||

| Myocardial Infarction Diagnosed during Current Admission | No | 161 (97.6%) | 295 (95.2%) | 456 (96.0%) | 0.201 |

| Yes | 4 (2.4%) | 15 (4.8%) | 19 (4.0%) | ||

| Severe Anemia (Hemoglobin < 7 g/dL) a | No | 115 (69.7%) | 301 (97.1%) | 416 (87.6%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 50 (30.3%) | 9 (2.9%) | 59 (12.4%) | ||

| Vasopressor Use Resulting in Peripheral Necrosis (Toes, Fingers) | No | 164 (99.4%) | 310 (100.0%) | 474 (99.8%) | 0.347 |

| Yes | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | ||

| Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD) | No | 165 (100.0%) | 310 (100.0%) | 475 (100.0%) | NA |

| Cardiac Arrest Sustained during Current Admission | No | 162 (98.2%) | 300 (96.8%) | 462 (97.3%) | 0.557 |

| Yes | 3 (1.8%) | 10 (3.2%) | 13 (2.7%) | ||

| Sepsis Continuum | |||||

| Any Type Sepsisa | No | 98 (59.4%) | 274 (88.4%) | 372 (78.3%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 67 (40.6%) | 36 (11.6%) | 103 (21.7%) | ||

| Sepsis | No | 100 (60.6%) | 289 (93.2%) | 389 (81.9%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 65 (39.4%) | 21 (6.8%) | 86 (18.1%) | ||

| Severe Sepsis | No | 123 (74.5%) | 297 (95.8%) | 420 (88.4%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 42 (25.5%) | 13 (4.2%) | 55 (11.6%) | ||

| Septic Shock | No | 127 (77.0%) | 300 (96.8%) | 427 (89.9%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 38 (23.0%) | 10 (3.2%) | 48 (10.1%) | ||

| MODS | No | 161 (97.6%) | 310 (100.0%) | 471 (99.2%) | 0.014 |

| Yes | 4 (2.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (0.8%) | ||

| Diabetes Diagnosisa | No | 111 (67.3%) | 229 (73.9%) | 340 (71.6%) | 0.129 |

| Yes | 54 (32.7%) | 81 (26.1%) | 135 (28.4%) | ||

| Mechanical Ventilation - Greater than 72 Hours? a | No | 77 (46.7%) | 230 (74.2%) | 307 (64.6%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 88 (53.3%) | 80 (25.8%) | 168 (35.4%) | ||

Note:

Variables were included in multivariate logistic regression in Table 6.

Additional significant differences between the groups are summarized in Table 3. Patients who developed HAPI had higher proportions of unintentional weight loss in one month (12% versus 6%, P =.002). They were more likely to have required dialysis (29% versus 4%, P < .001), used a bowel management system (21% versus 9%, P <.001), and required chemical sedation (56% 46%, P = .046). They were also more likely to have experienced lower mean serum hemoglobin levels (7.9, SD 1.6 versus 9.7, SD 2.1, P <.001), mean arterial pressure (MAP) <60 mmHg (61% versus 46%, P =.003), mechanical ventilation (79% versus 48%, P < .001), and nursing documentation of moisture (n= 55% versus 11%, P <.001). Patients with HAPI were also more likely to have received steroids (30% versus 17%, P = .001), had lower mean body temperature (35.9, SD 0.8 versus 36.2, SD 0.8, P = .004), and required vasopressors (41% versus 25%, P <.001). In contrast, the proportion of patients who experienced systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 90 mmHg was lower in the HAPI group (64% versus 83%, P <.001).

Table 3.

Effect of Comorbid Conditions on HAPI Occurrences

| Clinical Data | Category | HAPI (N = 165) |

Control (N = 310) |

Total (N = 475) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any type of dialysis | No | 118 (71.5%) | 296 (95.8%) | 414 (87.3%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 47 (28.5%) | 13 (4.2%) | 60 (12.7%) | ||

| Body Mass Index, Mean (SD) | 30.6 (12.1) | 30.6 (10.1) | 30.6 (10.9) | 0.987 | |

| Blood pH (lowest) , Mean (SD) | 7.3 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.1) | 0.907 | |

| Bowel Management system | No | 131 (79.4%) | 282 (91.3%) | 413 (87.1%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 34 (20.6%) | 27 (8.7%) | 61 (12.9%) | ||

| Capillary refill > 3 seconds | No | 133 (84.7%) | 217 (89.3%) | 350 (87.5%) | 0.176 |

| Yes | 24 (15.3%) | 26 (10.7%) | 50 (12.5%) | ||

| Chemically Sedated (IV Drip) | No | 73 (44.2%) | 167 (53.9%) | 240 (50.5%) | 0.046 |

| Yes | 92 (55.8%) | 143 (46.1%) | 235 (49.5%) | ||

| Daily Weight (kg), Mean (SD) | 88.4 (32.5) | 89.3 (29.2) | 88.9 (30.5) | 0.803 | |

| FiO2a, Mean (SD) | 59.6 (27.7) | 52.3 (25.1) | 55.6 (26.5) | 0.008 | |

| Hemoglobin (lowest) , Mean (SD) | 7.9 (1.6) | 9.7 (2.1) | 9.1 (2.1) | <.001 | |

| MAP < 60 a | No | 65 (39.4%) | 166 (53.7%) | 231 (48.7%) | 0.003 |

| Yes | 100 (60.6%) | 143 (46.3%) | 243 (51.3%) | ||

| Mechanical Ventilation | No | 35 (21.2%) | 161 (51.9%) | 196 (41.3%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 130 (78.8%) | 149 (48.1%) | 279 (58.7%) | ||

| Moisture a | No | 74 (44.8%) | 273 (88.9%) | 347 (73.5%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 91 (55.2%) | 34 (11.1%) | 125 (26.5%) | ||

| O2 stat (lowest) , Mean (SD) | 87.8 (9.2) | 86.7 (12.7) | 87.1 (11.6) | 0.295 | |

| Paralytic Agent > 2 hrs | No | 148 (90.2%) | 260 (85.5%) | 408 (87.2%) | 0.145 |

| Yes | 16 (9.8%) | 44 (14.5%) | 60 (12.8%) | ||

| Periop/ Procedure > or = to 4 hr | No | 150 (90.9%) | 48 (84.2%) | 198 (89.2%) | 0.160 |

| Yes | 15 (9.1%) | 9 (15.8%) | 24 (10.8%) | ||

| SBP < 90 mmHg a | No | 59 (35.8%) | 25 (8.1%) | 84 (17.7%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 106 (64.2%) | 285 (91.9%) | 391 (82.3%) | ||

| Specialty bed type | No | 149 (90.3%) | 301 (97.7%) | 450 (95.1%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 16 (9.7%) | 7 (2.3%) | 23 (4.9%) | ||

| Steroids | No | 116 (70.3%) | 258 (83.2%) | 374 (78.7%) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 49 (29.7%) | 52 (16.8%) | 101 (21.3%) | ||

| Temperature (highest-Celsius), Mean (SD) | 38.0 (0.9) | 37.9 (0.8) | 38.0 (0.8) | 0.067 | |

| Temperature (lowest-Celsius), Mean (SD) | 35.9 (0.8) | 36.2 (0.8) | 36.1 (0.8) | 0.004 | |

| Unintentional Weight loss of 10 or more pounds in one month? | No Yes |

121 (73.3%) 20 (12.1%) |

198 (66.7%) 19 (6.4%) |

319 (69%) 39 (8.4%) |

0.002 |

| Vasopressors (concurrently) | No | 97 (58.8%) | 234 (75.5%) | 331 (69.7%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 68 (41.2%) | 76 (24.5%) | 144 (30.3%) | ||

| Waffle mattress | No | 145 (87.9%) | 300 (98.4%) | 445 (94.7%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 20 (12.1%) | 5 (1.6%) | 25 (5.3%) |

Note:

Variables were included in multivariate logistic regression in Table 5.

The HAPI group displayed lower (worse) mean (SD) Braden subscale and total scores than the control group except for nutrition subscale (Table 4). The mean number of interventions targeted to activity, friction/shear and mobility subscales were higher in the control group (P <.001). In contrast, the mean number of interventions related to moisture (P <.001) and nutrition (NS) were higher in the HAPI group (Table 5).

Table 4.

Univariate Comparison of Braden Scale Scores

| Braden Inventory Outcome |

HAPI (N = 165) |

Control (N = 310) |

Total (N = 475) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.6 (0.8) | <.001 |

| Friction and Shear | 1.9 (0.5) | 2.3 (0.5) | 2.2 (0.5) | <.001 |

| Mobility | 2.1 (0.7) | 2.7 (0.9) | 2.5 (0.9) | <.001 |

| Moisture | 3.2 (0.5) | 3.6 (0.4) | 3.5 (0.5) | <.001 |

| Nutrition | 2.6 (0.4) | 2.7 (0.4) | 2.6 (0.4) | 0.104 |

| Sensory Perception | 2.7 (0.8) | 3.2 (0.8) | 3.0 (0.8) | <.001 |

| Braden Total Scorea | 13.8 (2.6) | 16.2 (3.1) | 15.4 (3.2) | <.001 |

Variables were included in multivariate logistic regression in Table 5.

Table 5.

Univariate Comparison of Preventive Interventions Based on Braden Scale Subscale Scores

| Braden Subscale Interventions | HAPI (N = 165) |

Control (N = 310) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity Interventions | 3.7 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.7) | <.001 |

| Friction/Shear Interventions | 4.9 (1.1) | 5.2 (1.1) | 0.032 |

| Mobility Interventions | 2.8 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.6) | <.001 |

| Moisture Interventions | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.5 (1.0) | <.001 |

| Nutrition Interventions | 2.1 (0.6) | 1.6 (0.5) | 0.104 |

| Sensory Perception Interventions | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.7) | 0.605 |

Variables were included in multivariate logistic regression in Table 6.

Scores were derived as the mean of total across 3 days prior.

Multivariate logistic regression showing the probability of developing HAPI for various clinical factors are summarized in Table 6. Specifically, participants with respiratory failure (OR= 3.00, 95% CI 1.27-7.08, P =.012), renal failure (OR=7.48, 95% CI 3.49-16.01; P <.001), cardiac failure (OR=4.50, 95% CI 1.76-11.51, P =.002), severe anemia (OR=10.89, 95% CI 3.59-33.00, P <.001), any type of sepsis (OR=3.15, 95% CI 1.44-6.90, P =.004), and moisture documentation (OR=11.89, 95% CI 5.27-26.81, P <.001) were more likely to develop a HAPI. In contrast, patients who had SBP < 90 mmHg were less likely to develop a HAPI. The ROC curve based on this model is presented in Figure 1. The accuracy of the model was excellent (AUC=.93). The cumulative Braden score did not emerge in the final model in the presence of multiple physiological risk factors.

Table 6.

Multivariate Logistic Regression of Effect of Comorbid Conditions on HAPI Development

| Clinical Data | DF | Estimate (SE) |

Test Statistic |

P Value |

OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory Failure | Yes | 1 | 1.10 (0.44) | 6.25 | 0.012 | 3.00 (1.27, 7.08) |

| Renal (Acute or Chronic) Failure | Yes | 1 | 2.01 (0.39) | 26.81 | <.001 | 7.48 (3.49, 16.01) |

| Cardiac Failure | Yes | 1 | 1.50 (0.48) | 9.85 | 0.002 | 4.50 (1.76, 11.51) |

| Liver Failure | Yes | 1 | 0.43 (0.76) | 0.32 | 0.571 | 1.54 (0.35, 6.77) |

| Severe Anemia (Hemoglobin < 7 g/dL) | Yes | 1 | 2.39 (0.57) | 17.82 | <.001 | 10.89 (3.59, 33.00) |

| Any Type of Sepsis Diagnosis | Yes | 1 | 1.15 (0.40) | 8.27 | 0.004 | 3.15 (1.44, 6.90) |

| Diabetes Diagnosis | Yes | 1 | −0.51 (0.40) | 1.63 | 0.202 | 0.60 (0.28, 1.31) |

| Mechanical Ventilation - Greater than 72 Hours | Yes | 1 | −0.02 (0.42) | 0.003 | 0.955 | 0.98 (0.43, 2.22) |

| APACHE II | 1 | −0.03 (0.02) | 2.21 | 0.137 | 0.97 (0.92, 1.01) | |

| FiO2 | 1 | 0.004 (0.01) | 0.34 | 0.559 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | |

| MAP < 60 | Yes | 1 | 0.66 (0.38) | 2.98 | 0.085 | 1.94 (0.91, 4.12) |

| Moisture | Yes | 1 | 2.48 (0.42) | 35.58 | <.001 | 11.89 (5.27, 26.81) |

| SBP < 90 mmHg | Yes | 1 | −2.87 (0.52) | 30.85 | <.001 | 0.06 (0.02, 0.16) |

| Braden Total Score | 1 | −0.06 (0.08) | 0.57 | 0.451 | 0.95 (0.82, 1.10) |

Abbreviation: DF = degree freedom, SE = Standard Error, OR = odds ratio, and CI = confidence interval.

For categorical variables, the reference level is NO.

Figure 1.

ROC Curve for Participants’ Clinical Factors

In order to examine the effects of risk factors and preventive interventions that mitigate those risk factors, separate multivariate logistic regression analyses incorporating all Braden subscale scores (AUC=.76) and the number of interventions by subscale (AUC=.78) were performed. The accuracy of the models was good, indicating that Braden subscale scores were predictive of pressure injury outcomes, and that interventions by subscale have a role in mitigating risks, particularly in the case of friction-shear-mobility-activity interventions.

Both Braden subscales and preventive interventions were then combined in a multivariate logistic model showing the probability of developing a HAPI (Table 7). Subscale scores and number of interventions per subscale that were significant on univariate analysis (P = .05) were included in the model. Because the interventions targeted to activity, friction/shear and mobility are all related to redistribution of pressure and are similar across subscales, only friction/shear interventions were included in the multivariate logistic regression model to avoid duplication. The multivariate logistic regression analysis found for a one-unit increase in the moisture subscale of the Braden Scale, there was 67% decrease in the odds of having a HAPI (OR=.33, 95% CI 0.19-0.57, P <.001). Patients with higher subscales scores of friction/shear (OR=.42, 95% CI .23-.77, P =0.005) and mobility (OR=.52, 95% CI .30-.93, P =.026) were less likely to have a HAPI. In addition, patients with more friction/shear interventions were less likely to have a HAPI (OR=.63, 95% CI .51-.79, P <.001). See Figure 2. The accuracy of the combined subscale-intervention model was good (AUC=.78).

Table 7.

Multivariate Analysis* of Preventive Intervention Based on Braden Scale Subscale Scores

| Subscale/Intervention | DFa | Estimate (SEa) |

Test Statistic |

P Value | OR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity subscaleb | 1 | −0.19 (0.28) | 0.45 | 0.502 | 0.83 (0.48, 1.43) |

| Sensory perception subscaleb | 1 | 0.36 (0.23) | 2.36 | 0.124 | 1.43 (0.91, 2.27) |

| Moisture subscaleb | 1 | −1.11 (0.28) | 15.87 | <.001 | 0.33 (0.19, 0.57) |

| Friction/Shear subscaleb | 1 | −0.88 (0.31) | 7.93 | 0.005 | 0.42 (0.23, 0.77) |

| Mobility subscaleb | 1 | −0.65 (0.29) | 4.97 | 0.026 | 0.52 (0.30, 0.93) |

| Moisture interventionb | 1 | −0.06 (0.18) | 0.12 | 0.728 | 0.94 (0.67, 1.33) |

| Friction-shear interventionb,c | 1 | −0.46 (0.11) | 16.11 | <.001 | 0.63 (0.51, 0.79) |

Abbreviation: DF = degree freedom, SE = Standard Error, OR = odds ratio, and CI = confidence interval.

Scores were derived as the mean of total across 3 days prior.

There was an overlap in the interventions that address low subscale scores (i.e. higher risk) for activity, mobility, friction-shear and sensory perception. The friction-shear intervention set on the PUPI tool incorporated all of these interventions and was therefore used for this analysis.

=Logistic Regression Analysis

Figure 2.

ROC Curve for Participants’ Braden Subscale Scores and Interventions

Aim 2: Avoidable versus Unavoidable HAPI: Influence of ASF Risk Factors

The secondary data indicated, using the PUPI, 41% (n=67) of the HAPI were unavoidable and 59% (n=98) were avoidable. The proportions of unavoidable HAPI among critically-ill patients are illustrated in Table 8 based on the proposed ASF risk factors described earlier. In patients with unavoidable pressure injuries, there was a paradoxically lower proportion of cardiac failure (15% versus 31%, P =.021) and any type of organ failure (90% versus 98%, P =.032). There were no statistically significant differences between unavoidable and avoidable HAPI groups related to the other proposed ASF risk factors.

Table 8.

Univariate Acute Skin Failure Proposed Risk Factors by Domain and Unavoidable and Avoidable HAPI

| ASF Domain (bolded)/Risk Factor |

Category | Unavoidable (N = 67) |

Avoidable (N = 98) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organ Failure | |||||

| Any type | No | 7 (10.5%) | 2 (2.0%) | ||

| Yes | 60 (90.0%) | 96 (98.0%) | 0.032 | ||

| Respiratory failure | No | 16 (23.9%) | 16 (16.3%) | ||

| Yes | 51 (76.1%) | 82 (83.7%) | 0.228 | ||

| Renal (Acute or Chronic) Failure | No | 26 (38.8%) | 35 (35.7%) | ||

| Yes | 41 (61.2%) | 63 (64.3%) | 0.682 | ||

| Cardiac Failure | No | 57 (85.1%) | 68 (69.4%) | ||

| Yes | 10 (14.9%) | 30 (30.6%) | 0.021 | ||

| Liver Failure | No | 58 (86.6%) | 87 (88.8%) | ||

| Yes | 9 (13.4%) | 11 (11.2%) | 0.670 | ||

| Limited Tissue Perfusion | |||||

| Any type | No | 47 (70.2%) | 63 (64.3%) | ||

| Yes | 20 (29.9%) | 35 (35.7%) | 0.433 | ||

| Myocardial Infarction Diagnosed during Current Admission | No | 65 (97.0%) | 96 (98.0%) | ||

| Yes | 2 (3.0%) | 2 (2.0%) | 1.000 | ||

| Severe Anemia (Hemoglobin < 7 g/dL) | No | 50 (74.6%) | 33 (33.7%) | ||

| Yes | 17 (25.4%) | 65 (66.3%) | 0.255 | ||

| Vasopressor Use Resulting in Peripheral Necrosis (Toes, Fingers) | No | 67 (100.0%) | 97 (99.0%) | ||

| Yes | 0 | 1 (1.0%) | 1.000 | ||

| Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD) | No | 67 (100.0%) | 98 (100.0%) | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | NA | ||

| Cardiac Arrest Sustained during Current Admission) | No | 65 (97.0%) | 97 (99.0%) | ||

| Yes | 2 (3.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0.567 | ||

| Diagnosis of sepsis | |||||

| Any type | No | 39 (58.2%) | 59 (60.2%) | ||

| Yes | 28 (41.8%) | 39 (39.8%) | 0.798 | ||

| Sepsis | No | 39 (58.2%) | 61 (62.2%) | ||

| Yes | 28 (41.8%) | 37 (37.8%) | 0.602 | ||

| Severe Sepsis | No | 51 (76.1%) | 72 (73.5%) | ||

| Yes | 16 (23.9%) | 26 (26.5%) | 0.701 | ||

| Septic Shock | No | 53 (79.1%) | 74 (75.5%) | ||

| Yes | 14 (20.9%) | 24 (24.5%) | 0.590 | ||

| MODS | No | 65 (97.0%) | 96 (98.0%) | ||

| Yes | 2 (3.0%) | 2 (2.0%) | 1.000 | ||

| Diabetes Diagnosis | No | 44 (65.7%) | 64 (67.4%) | ||

| Yes | 23 (34.3%) | 31 (32.6%) | 0.822 | ||

|

Mechanical Ventilation - Greater than 72 Hours |

No | 33 (49.3%) | 43 (44.3%) | ||

| Yes | 34 (50.8%) | 54 (55.7%) | 0.534 | ||

Aim 3: Identify potential predictive ASF risk factors

In Aim 2, we did not find statistically significant and clinically meaningful differences in proposed ASF risk factors between those with unavoidable HAPI and avoidable HAPI. Therefore, predictive analyses were not appropriate and were not performed specific to ASF.

Discussion

In our case-control study, we found that patients who developed a HAPI were generally sicker than the control group. They had higher APACHE II scores (P=.000) indicating more severe illness and a higher actual mortality rate (P=.002). This is consistent with a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Song and colleagues who evaluated a pooled sample of 5,523 patients.20 They found an increased risk for death (HR: 1.96, 95% CI: 1.79-2.14) in older adult patients with pressure injuries. Our analysis indicated that patients who developed HAPI were more likely to have a history of a previous pressure injury, liver disease, and recent unintentional weight loss. However, there were a high number of “unknown” with regard to prior history of pressure injury (272 of 475) rendering this finding inconclusive. Nevertheless, our findings may alert the clinician to identify these factors and implement prevention strategies sooner.

Critically-ill patients are often physiologically and hemodynamically unstable requiring complex treatment supporting perfusion and circulation. Perfusion and circulation deficits were identified in our study as being associated with an increased likelihood of developing a HAPI. Specifically, patients with HAPI had lower mean hemoglobin (P <.001), episodes of low mean arterial pressure (MAP) < 60 (P =.003) and required mechanical ventilation for more than 72 hours (P <.001). Patients with respiratory failure, cardiac failure, and severe anemia were also more likely to develop HAPI (P <.001). Similar results were detected for patients who had renal failure or any type of sepsis diagnosis. Our findings support the 2019 International Guideline on prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries.4

We also found that fewer patients in the HAPI group had SBP < 90 mmHg compared to the control group. This finding might be attributable to a significantly higher usage of vasopressors among patients who developed HAPI. Vasopressors are commonly used in critically-ill patients to raise blood pressure and to improve central organ perfusion (brain, heart, lung, kidney). Conversely vasopressors divert blood flow away from the skin, which alters the mechanical properties of the tissue and increases susceptibility to higher mechanical loads (pressure) thus increasing the likelihood of pressure injury.4

Unintentional weight loss was associated with having a HAPI in our study. Nursing documentation of the Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST), which is completed once upon admission, was used to identify recent weight loss.21 This finding confirms the importance of nutritional screening in the critically-ill patient. There are limited biological markers for malnutrition,22 and the markers commonly used do not correlate well with clinical observation of nutritional status. However, a weight history is a common item in most nutrition screening tools, and it is simple and easy to collect. Early malnutrition screening leads to timely nutrition recommendations.4 In our study, the Braden nutrition subscale scores did not significantly differ between the HAPI and control groups. The association between unintentional weight loss (MST) and Braden Nutrition subscale scores was anticipated. A nutritional consult and interventions are implemented once the malnutrition risk is identified upon admission. Conversely, the Braden is completed every 12 hours and is an ongoing risk assessment during the hospital stay. Therefore, the MST and Braden nutrition subscale score in our study should not be compared as they are measured very differently.

Our findings related to HAPI and Braden scores support the value of the Braden scale for identification of pressure injury risk. Patients with a HAPI had significantly lower mean Braden subscale scores for sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, and friction/shear and lower Braden total scores indicating a higher risk for HAPI. There was no difference between HAPI and control groups related to nutrition subscale scores. In spite of higher risk, significantly fewer prevention interventions targeted to activity, mobility, and friction/shear subscales were documented in the HAPI group, indicating a possible link to the HAPI development. There was no statistically significant difference between HAPI and control groups in the mean number of sensory perception prevention interventions. One possible explanation for these findings is that there is some overlap between sensory perception interventions and other subscale-based interventions.

We found that patients with presence of moisture (as documented by nursing in EHR) were more likely to have a HAPI (OR=11.89, 95% CI 5.27-26.81, P <.001). This supports the work of Lachenbruch and colleagues23 who analyzed 176,689 patients and found an association between urinary and fecal incontinence and pressure injury occurrences, along with higher facility acquired pressure injury rate (P <.0001).23 Incontinence (moisture) increases susceptibility for soft tissue damage from friction, chemical and physical irritation and pressure.24, 25

The HAPI group as compared to the control group in our study had more clinical documentation of moisture from incontinence (55.2%, P <.001), more bowel management (fecal) devices (22.4%, P <.001), and more documented linen changes (15%, P <.001). There was no difference between groups in urinary management interventions such as urinary device (internal or external) or scheduled voiding, indicating moisture was more likely related to fecal rather than urinary incontinence. Incontinence, specifically fecal incontinence, has been identified in the literature as a key risk factor for pressure injury development.23, 25, 26, 27 Our findings support the findings of multiple investigators who examined fecal incontinence in the critical care patient and found a relationship between fecal incontinence, incontinence associated dermatitis and development of pressure injuries.23, 24, 25, 26, 27

While diabetes mellitus is also associated with an increased likelihood of pressure injury4 it did not emerge as a risk factor for HAPI in our study. This difference may have occurred because we defined this as dichotomous (diagnosis of diabetes: yes or no) and did not collect more specific data related to diabetes such as duration of diabetes, type diabetes, glycemic control/HbA1c, and insulin use.

Multivariate analysis of the Braden Scale subscale scores and number of subscale risk-based interventions provided clinically relevant information and supports the use of the Braden Scale to drive care. Lower Braden subscale scores in moisture, friction-shear and mobility subscales were predictive of having a HAPI. Because those interventions targeted to activity, friction/shear and mobility were similar across subscales, only friction/shear interventions were included in the multivariate logistic regression model to avoid duplication. Subsequently, in our study those patients with more friction/shear interventions were less likely to have a HAPI. This makes sense as subscale-targeted interventions should mitigate the risk factors represented in subscale scores and our findings support this.

The association of unavoidable HAPI with ASF remains unclear as evidenced in other studies.28, 29 In our study, we found no significant relationship between unavoidable HAPI and ASF. While a consistent link between patients with unavoidable HAPI and proposed ASF risk factors was not demonstrated, it is important to note that, in our study, patients with a HAPI (both avoidable and unavoidable) had more statistically significant clinical factors consistent with proposed ASF risk factors than the control group (no HAPI). The proposed ASF risk factors may differentiate those with and without pressure injuries, but in our study, did not differentiate unavoidable from avoidable pressure injuries or serve as markers or predictors of acute skin failure. Additional research is needed in this area.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study may influence generalizability of findings. This study was a retrospective design relying on accuracy of documentation and not allowing for confirmation of findings through observation. In addition, the study was conducted at a large healthcare system with high patient acuity and may not be generalized to other settings. Data retrieval to complete the PUPI relied on the accuracy of the documentation in the EHR. Timing for data collection for the control group (no HAPI) was 4 days post critical/progressive care admission, contrasting with the HAPI group which may have been longer into the critical care stay (3 days pre-HAPI first documentation) before the HAPI was first documented. The complexity of the EHR and nursing documentation was evident during data collection even though the EHR used in this study is a commonly used international EHR software. Another limitation was the inclusion of progressive care patients, however, the acuity of the progressive care patients in this healthcare organization are complex and considered to be very similar to other smaller hospitals’ critical care settings.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that key clinical characteristics and risk factors, such as patient acuity, organ failure, tissue perfusion, sepsis and history of prior pressure injury, are associated with development of HAPI, including both avoidable and unavoidable HAPI. We were unable to support a relationship between unavoidable HAPI and the proposed risk factors for acute skin failure (ASF). This is important information and supports the need for further research in this area. Our study findings support that HAPI unavoidability rests with the documentation of appropriate interventions and not necessarily with the identification of clinical risk factors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Association of Critical Care Nurses Research Impact Grant.

The contributions of Michelle Mravec and Caeli Malloy were partially supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award number T32NR018407. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Norwicki J, Mullany D, Spooner A, Norwicki T, McKay P, Corley A, Fulbrook P, Fraser J. Are pressure injuries related to skin failure in critically ill patients? Australian Critical Care. 2018; 31: 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox J Predictors of pressure ulcers in adult critical care patients. Americal Journal of Critical Care. 2011; 20(5): 364–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alderden J, Whitney J, Taylor S, Zaratkiewicz S. Risk profile characteristics associated with outcomes of Hospital-Acquired Pressure Ulcers: A retrospective review. Critical Care Nurse. 2011; 31(4): 30–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel NPIAPaPPPIA. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline. The International Guideline. In: Haesler E, ed.: EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edsberg LE, Langemo D, Baharestani MM, Posthauer ME, Goldberg M. Unavoidable pressure injury: state of the science and consensus outcomes. Journal of Wound, Ostomy & Continence Nursing. 2014; 41(4): 313–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Association of Critical Care Nurses (AACN). Frequently asked questions about PCCN certification. AACN.org. Accessed Dec 3, 2020.

- 7.Ayello E, Levine J, Langemo D, Kenneddy-Evans K, Brennan M, Sibbald G. Reexamining the Literature on Terminal Ulcers, SCALE, Skin Failure, and Unavoidable Pressure Injuries. Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 2019; 32(3): 109–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delmore B, Cox J, Rolnitzky L, Chu A, Stolfi A. Differentiating a pressure ulcer from acute skin failure in the adult critical care patient. Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 2015; 28(11): 514–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langemo DK, Brown G. Skin fails too: acute, chronic, and end-stage skin failure. Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 2006; 19(4): 206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shanks HT, Kleinhelter P, Baker J. Skin failure: a retrospective review of patients with hospital-acquired pressure ulcers. WCET. 2009; 29(1): 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine J Unavoidable Pressure Injuries, Terminal Ulceration, and Skin Failure: In Search of a Unifying Classification System. Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 2017; 30(5): 200–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Black J, Edsberg L, Baharestani M, Langemo D, Goldberg M, McNichol L, Cuddigan J, National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Pressure ulcers: Avoidable or unavoidable? Results of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Consensus Conference. Ostomy Wound Management. 2011; 57(2): 24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pittman J, Beeson T, Terry C, Dillon J, Hampton C, Kerley D, Mosier J, Gumiela E, Tucker J. Unavoidable pressure ulcers: development and testing of the Indiana University Health pressure ulcer prevention inventory. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing. 2016; 43(1): 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pittman J, Beeson T, Dillon J, Yang Z, Cuddigan J Hospital-acquired pressure injuries in critical and progressive care: avoidable versus unavoidable. Am J Crit Care. 2019; 28(5): 338–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coltart GS, Irvine C. Skin Failure. Skinmed. 2018; 16(3): 155–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olshansky K Classifying Skin Failure. Advances in skin & wound care. 2017; 30(9): 392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dalgleish L, Campbell J, Finlayson K, Coyer F. Acute Skin Failure in the Critically Ill Adult Population: A Systematic Review. Advances in Skin and Wound Care. 2020; 33(2): 76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simundic AM. Measures of diagnostic accuracy: basic definitions. Journal of the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. 2009; 19(4): 203–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Critical Care Medicine. 1985; 13(10): 818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song Y, Shen H, Cai J, Zha M, Chen H. The relationship between pressure injury complication and mortality risk of older patients in follow-up: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Wound Journal. 2019; October:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferguson M, Capra S, Bauer J, Banks M. Development of a valid and reliable malnutrition screening tool for adult acute hospital patient. Nutrition 1999; 15: 458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richards J, Litchford M, & Pittman J. Nutrition to aid wound healing in the aging adult. The Journal of Active Aging. 2019; Jan-Feb. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lachenbruch C, Ribble D, Emmons K, VanGilder C. Pressure ulcer risk in the incontinent patient. Journal Wound Ostomy Continence Nursing. 2016; 43(3): 235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beeckman D, Van Damme N, Schoonhoven L, Van Lancker A, Kottner J, Beele H, Gray M, Woodward S, Fader M, Van den Bussche K, Van Hecke A, De Meyer D, Verhaeghe S. Interventions for preventing and treating incontinence-associated dermatitis in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016; 11 (Art. No.: CD011627). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray M & Giuliano KK. Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis, Characteristics and Relationship to Pressure Injury A Multisite Epidemiologic Analysis. Journal Wound Ostomy Continence Nursing. 2017; 45(1):63–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bliss D, Savik K, Thorson M, Ehman S, Lebak K, Beilman G. Incontinence-associated dermatitis in critically ill adults. Journal Wound Ostomy Continence Nursing. 2011; 38(4): 433–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park K, Choi H. Prospective study on Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis and its Severity instrument for verifying its ability to predict the development of pressure ulcers in patients with fecal incontinence. International Wound Journal. 2016; 13 Suppl 1: 20–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curry K, Kutash M, Chambers T, Evans A, Holt M, Purcell S. A prospective, descriptive study of characteristics associated with skin failure in critically ill adults. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2012; 58(5): 35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delmore B, Cox J, Smith D, Chu A, Rolnitsky L. Acute skin failure in the critical care patient. Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 2019; 32(12). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.