ABSTRACT

Binary expression systems are a powerful tool for tissue- and cell-specific research. Many of the currently available Drosophila eye-specific drivers have not been systematically characterized for their expression level and cell-type specificity in the adult eye or during development. Here, we used a luciferase reporter to measure expression levels of different drivers in the adult Drosophila eye, and characterized the cell type-specificity of each driver using a fluorescent reporter in live 10-day-old adult males. We also further characterized the expression pattern of these drivers in various developmental stages. We compared several Gal4 drivers from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) including GMR-Gal4, longGMR-Gal4 and Rh1-Gal4 with newly developed Gal4 and QF2 drivers that are specific to different cell types in the adult eye. In addition, we generated drug-inducible Rh1-GSGal4 lines and compared their induced expression with an available GMR-GSGal4 line. Although both lines had significant induction of gene expression measured by luciferase activity, Rh1-GSGal4 was expressed at levels below the detection of the fluorescent reporter by confocal microscopy, while GMR-GSGal4 showed substantial reporter expression in the absence of drug by microscopy. Overall, our study systematically characterizes and compares a large toolkit of eye- and photoreceptor-specific drivers, while also uncovering some of the limitations of currently available expression systems in the adult eye.

KEYWORDS: GMR, Rh1, Gal4 expression system, Geneswitch Gal4, QF2 expression system, Drosophila, photoreceptor

Introduction

The Drosophila melanogaster eye has been used as an important model system for studying cell-cell signalling during development, visual transduction, neurobiology, neurodegeneration, and ageing [1–3]. The Drosophila eye is particularly amenable to genetic screens because flies with cell-lethal mutations expressed eye-specifically remain viable[4]. Thus, genetic tools to enable expression specifically in various cell types in the eye provide an important resource for the Drosophila community. In recent years, several different binary expression systems that enable tissue-specific gene expression have been developed for Drosophila[5]. The most established of these is the Gal4/UAS system adopted from yeast that utilizes the Gal4 transcription factor and its upstream activating sequence (UAS) [6,7]. In this system, a temperature sensitive version of the Gal4 repressor, Gal80, allows for temporal regulation [8,9]. Recently, the QF/QUAS system derived from Neurospora crassa has emerged as another powerful binary expression system[10]. QF2/QUAS is analogous to the Gal4/UAS system, and uses the QF activator to drive expression of QUAS-transgenes. In addition, the QF/QUAS system offers a useful new means of temporal regulation in the form of a quinic acid inhibited QF repressor. This drug-inducible approach has advantages over the temperature-sensitive Gal80 system because increased temperature can impact behaviour, development and lifespan in Drosophila[11].

In this study, we focused on developing and characterizing several binary expression tools for use in the adult Drosophila eye. The Drosophila compound eye contains approximately 800 individual units called ommatidia, which are arranged in an orderly honeycomb like lattice[12]. This hexagonal lattice is composed of a total of 12 interommatidial cells (IOCs) surrounding each ommatidium: six secondary pigment cells, three tertiary pigment cells and three sensory bristle cells[12]. Contained within each ommatidium lies an ordered array of eight photoreceptor (retinula, R) cells; the primary sensory neurons necessary for vision. The R1-R6 photoreceptors make up the outer trapezoidal arrangement with R7 stacked atop R8 near the centre. Above these photoreceptor cells are two primary pigment cells and four cone cells, which are responsible for secreting the lens and pseudocone of each ommatidium. The adult Drosophila eye originates from the eye imaginal disc, a bi-layered invagination of the ectoderm that first forms in embryo[1]. This tissue continues to grow throughout larval development, and by early pupal development all cells of the adult eye are terminally differentiated[1].

There are several Gal4 drivers that have been widely used when studying eye development; however, many of these eye-specific Gal4 drivers have been less extensively characterized in tissues outside the developing eye and in specific cell types in the adult Drosophila eye. For instance, recent reports have noted that the commonly used Sev-Gal4 and GMR-Gal4 drivers have much broader expression profiles extending to neurons in the central nervous system (CNS) as well as in non-neuronal tissue such as the trachea and spiracles[13]. Additionally, the GMR-Gal4 driver has been reported to cause disrupted ommatidia patterning and a visible rough eye phenotype in adults[14]. Here, we sought to systematically characterize the expression pattern of some of the existing eye-specific Gal4 drivers in the adult Drosophila eye. We also describe several new eye-specific binary expression drivers generated by our lab that can be used for different cell type-specific expression.

Materials and methods

Cloning and transgenic flies

Transgenic Rh1-QF2 and Rh1-GSGal4 flies were generated in the w1118 background using P-element transformation by BestGene (CA), and the chromosomal location of each insertion was determined using standard genetic techniques and inverse PCR[15]. To generate the Rh1-QF2 flies, the QF2 (QF#7m1) coding sequence from pCasper-act(B)-QF2w-act_term (Addgene #46126)[16] was PCR amplified with 5ʹ XbaI and 3ʹ EcoRI restriction sites using the following primers: 5ʹ-CCTCTAGAATGCCACCCAAGCGCAAAACGC-3ʹ and 5ʹ-TTGAATTCTCATTTCTTCTTTTTGTATGTATTAATG-3ʹ. The QF2 PCR fragment was then cloned into pCaSpeR-ninaE-forward containing the ninaE promoter and 3ʹ region (kindly provided by J. O’Tousa) as an XbaI/EcoRI fragment to make pCaSpeR-ninaEp-QF2. To generate the Rh1-GSGal4 flies, the Gene-switch Gal4 (Gal4-hPR-p65 fusion protein) coding sequence from pSwitch #1 (DGRC #1047)[17] was cloned into pCaSpeR-ninaE-reverse containing the ninaE promoter and 3ʹ region (provided by J. O’Tousa) as a NotI fragment to make pCaSpeR-ninaEp-GeneswitchGal4. All plasmids generated in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Plasmids generated in this study

| Plasmid Name | Associated Fly stocks |

|---|---|

| pCaSpeR-ninaEp-QF2 | Rh1-QF2 |

| pCaSpeR-ninaEp-GeneswitchGal4 | Rh1-GSGal4 |

| pBMP-pRh1(−120/+67)-Gal4LWL | sRh1-Gal4 |

| pBMP-pRh1(−450/+62)-Gal4LWL | mRh1-Gal4 |

To generate the sRh1-Gal4 and mRh1-Gal4flies, the following regions of the ninaE promoter/enhancer region were PCR amplified with added 5ʹ NotI and 3ʹBglII restriction sites: sRh1 209 bp fragment (−120/+67 bp) was amplified using 5ʹ-CTTGCGGCCGCGTCGACACTTTCCTCTGCACATTG-3ʹ and 5ʹ-TTAAGATCTAGGGTTCCTGGATTCTGAATATTTC-3ʹ from Drosophila genomic DNA; mRh1 532bp fragment (−450/+62bp) was amplified using 5ʹ-CTTGCGGCCGCATAATCCAAGATTAGCAGAGCCCTC-3ʹ and 5ʹ-TTAAGATCTATTCTGAATATTTCACTGGGGCG-3ʹ from pJRG40 (provided by J. Rister)[18]. The sRh1 or mRh1 promoter fragments were cloned into pBMPGal4LWL (Addgene #26270)[19] as NotI/BglII fragments to generate the pBMP-pRh1(−120/+67)-Gal4LWL and pBMP-pRh1(−450/+62)-Gal4LWL vectors and integrated in the attP2 and attP-9A sites, respectively, using ΦC31-mediated transformation by BestGene (CA). All fly stocks used in this study are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Fly lines and chromosomal insertion sites. (*) indicates insertion sites determined by inverse PCR in this study

| Stock Name | Source | Location (nearest gene) | Genotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| UAS-Luc | BDSC 61678 | 3 | w1118;; 1P{UAS-LUC.D}3 |

| 20XUAS-6XmCherry | BDSC 52268 | *3 L:11070538 (Mocs1) | y1 w*; wgSp−1/CyO, P{Wee-P.ph0}BaccWee-P20; P{y+t7.7 w[+mC] = 20XQUAS-6XmCherry-HA}attP2 |

| 10XQUAS-6XmCherry | BDSC 52270 | 2 L:2752799 (attP2) | y1 w*; wgSp−1/CyO, P{Wee-P.ph0}BaccWee-P20; P{y+t7.7 w[+mC] = 10XQUAS-6XmCherry-HA}attP2 |

| GMR-Gal4 | BDSC 1104 | *2 R:10535014 (lola) | w*; P{w+mC = GAL4-ninaE.GMR}12 |

| longGMR-Gal4 | BDSC 8121 | *3 R: 15343048 (CG6218) | cn bw; P{w+mC = longGMR-Gal4}3/MKRS |

| Rh1-Gal4 (3) | BDSC 8691 | *3 R: 6622632 (sowi) | ;;P{ry+t7.2 = Rh1-Gal4}3, ry506 |

| sRh1-Gal4 | this study | 3 L:11070538 (attP2) | w1118;;P{w+mC = pRh1(−120/+67)-GAL4}attP2 |

| mRh1-Gal4 | this study | *2 R:7224205 (pk) | w1118;P{w+mC = pRh1(−450/+62)-GAL4}attP-91(43A1) |

| GMR-GSGal4 | BDSC 6758 | *2 R: 24786883 (key) | w1118; P{w+mC = GMRinGS}11 |

| Rh1-GSGal4 (X) | this study | *X: 16278373 (eas) | w1118; P{w+mC = Rh1inGS}X-9 |

| Rh1-GSGal4 (2) | this study | *2 R: 24786883 (key) | w1118; P{w+mC = Rh1inGS}2-3/CyO |

| QUAS-Luc | BDSC 64773 | *3 R:11808359 (CIC-a) | y1 w*; M{w[+mC = QUAS-Ppyr\LUC.G}ZH-86Fb |

| Rh1-QF2 (2) | this study | *2 L: 12507855 (bun) | w1118; P{w+mC = ninaEp-QF2}/CyO |

| Rh1-QF2 (3–1) | this study | *3 L: 14205383 (nuf) | w1118;; P{w+mC = ninaEp-QF2} |

| Rh1-QF2 (3–2) | this study | *3 L: 20895359 (Sfp77F) | w1118;; P{w+mC = ninaEp-QF2} |

| Rh1-QF2 (3–3) | this study | *3 L: 14076958 (bt1) | w1118;; P{w+mC = ninaEp-QF2}/TM3, Sb |

Fly stock maintenance, crosses and drug treatment

Flies were raised under a 12:12 hour light:dark cycle at 25°C on cornmeal agar fly food. Gal4 or QF2 driver flies were crossed with UAS-Luc (BDSC 61678) or QUAS-Luc (BDSC 64773) for luciferase assays, or with 20XUAS-6XmCherry (BDSC 52268) or 10XQUAS-6XmCherry (BDSC 52270) for confocal microscopy, and male progeny of the appropriate genotype were selected using visible markers. Mated male flies were collected ±1 day after eclosion and aged for 10 days with transfer to fresh food every 2–3 days for assays unless otherwise described. To induce GSGal4 activity, 8-day-old flies were starved overnight and then placed in vials containing 3.2 mg/mL RU486 (Sigma) dissolved in 200 µL 1% (w/v) sucrose solution in ethanol or vehicle control (1% sucrose in ethanol) for 24 h prior to luciferase assays or microscopy.

Luciferase assays

Luciferase assays were performed as previously described[20]. Briefly, two heads from male flies of the appropriate age, genotype and/or drug treatment were homogenized in 100 μL of 1x Promega cell culture lysis reagent (#E153A, 25 mM Tris-phosphate pH 7.8, 2 mM DTT,10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100) and 25 µL of homogenate was added to 50 µL of luciferase reagent (Promega, #E1500). Four biological replicates were conducted per genotype/drug treatment (two biological replicates for GSGal4 drug duration experiments), and two technical replicates were conducted for each luciferase assay.

Confocal microscopy on live adult eyes

Confocal microscopy of mCherry fluorescent markers expressed in the eye was performed in live fly eyes as previously described[21]. Briefly, a small petri dish (60 × 15 mm) was filled halfway with 1.5% (w/v) agarose solution at 55°C. While the agarose was still unsolidified but slightly cooled, 5–10 anaesthetised male flies were embedded into the surface of the agarose. Petri dishes were stored on ice to solidify the agarose and keep the flies anaesthetised. To image flies, ice-cold water was added to the petri dish to cover the embedded flies. Using forceps under a dissecting microscope, the head of each fly was gently oriented to position the appearance of the pseudopupil into the middle of the eye. Although flies remain alive during imaging and can be recovered after this process, it is possible that this protocol results in some stress to the fly during the imaging process. Imaging was conducted with a Zeiss LSM780 confocal microscopy using a Zeiss Plan-Apochromat 40x/1.0 DIC M27 water dipping objective. Three biological replicates were conducted per genotype/drug treatment, and representative images are presented.

Embryo collection, fixation, and mounting

Embryos were collected by raising the appropriate mating cross in small cages on standard grape juice agar plates. Plates were changed every 18–24 h and stored at 4°C for up to 3 days. Embryos were fixed using standard formaldehyde fixation followed by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining[22], and mounted on a glass slide in VectaShield (Vector Laboratories, #H100010).

Larval and pupal mounting

Wandering third instar larvae or late-stage pupae of the appropriate genotype were collected from vials and transferred to Pyrex spot well plates. Larvae or pupae were then rinsed with PBS. For pupae, heads were dissected by cutting the most anterior section of the pupal case and then peeling back the case to reveal the heads. The heads were then cut and briefly washed in PBS. Either whole larvae or pupal heads were then mounted in VectaShield on a glass slide. A coverslip was secured over the larvae or pupal heads using dental wax as a bridge. Preparations were immediately imaged.

Fluorescence microscopy of embryos, larvae and pupal heads

All developmental tissues were imaged by fluorescence microscopy using a Leica DM6B-Z microscope equipped with a Leica DFC9000 camera using either an HC PL APO 10x/0.40 DRY (larvae, pupal heads) or HC PL APO 20x/0.70 DRY (embryos) objective.

Results

Driver design for eye and photoreceptor-specific expression

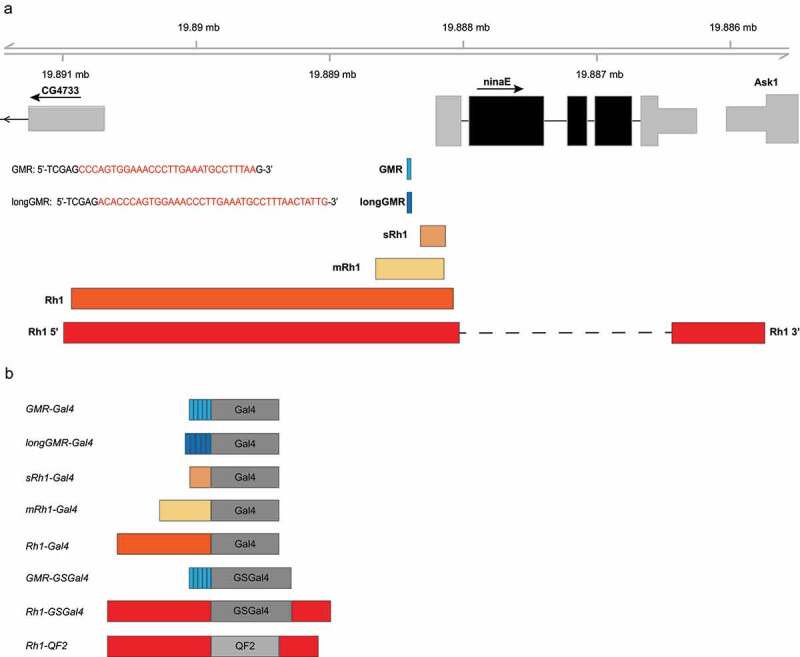

We initially sought to develop a set of binary expression tools for the outer photoreceptors (R1 – R6) in the adult compound eye by taking advantage of regulatory elements in the ninaE gene, which encodes Rhodopsin 1, the light-sensing G-protein coupled receptor necessary for phototransduction[23]. Expression of the ninaE transcript is present at very low levels in pre-pupa, rises to high levels in 3-day-old pupa, and persists at high levels throughout the life-span of adult flies[24]. In the larva, ninaE is expressed only in the light sensing Bolwig organ, while expression in adult eye is limited to R1 – R6, although expression has also been detected in the sensory neurons of the antennal Johnston’s organ[25]. There are three Gal4 driver lines available from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) that include regulatory elements from ninaE: GMR-Gal4, longGMR-Gal4, and Rh1-Gal4 (Table 2). The GMR-Gal4 driver contains five copies of a 29 bp region of the ninaE promoter that includes a binding site for the Glass transcription factor (gl) flanked by the XhoI restriction site (35 bp total fragment size; Figure 1)[26]. In larva, GMR-Gal4 has been reported to drive expression in all cells posterior to the morphogenic furrow of the eye imaginal disc[27], and is also expressed in the midgut and salivary glands [28,29]. The expression in the midgut and salivary glands likely results from the presence of the hsp70 minimal promoter in GMR-Gal4[30]. In adult flies, GMR-Gal4 drives expression in R1 – R8 photoreceptor cells[27]. Although GMR-Gal4 has been extensively used to drive expression in the developing eye [7,31], its high expression levels in the adult eye are associated with toxicity and retinal degeneration[14]. In contrast, the longGMR-Gal4 driver contains five copies of a longer 38 bp fragment from the ninaE promoter containing the gl binding motif flanked by XhoI (43 bp total fragment size; Figure 1)[32]. LongGMR-Gal4 is generally reported to be more photoreceptor specific than GMR-Gal4 [32,33], however to our knowledge an extensive characterization of this driver has never been published. Whereas both the GMR-Gal4 and longGMR-Gal4 drivers are expressed during larval development in the eye imaginal disc [27,32], the longer 3 kb ninaE promoter fragment used in the Rh1-Gal4 driver results in an expression pattern more similar to that of the endogenous ninaE gene, which is R1 – R6 specific [23,34,35]. ninaE is not expressed in the eye imaginal disc of larvae since its expression begins later into pupal development, after R cells are already differentiated, and persists through adulthood[35].

Figure 1.

Overview of the ninaE regulatory regions used in the Gal4 and QF2 driver constructs. a) Schematic of the ninaE locus on chromosome 3 (3 R:19,888,206) showing relative positions of the regulatory elements used in each of the driver constructs. Inset text shows the sequences of the Glass transcription factor binding site in the ninaE promoter that were pentamerized to generate the GMR or longGMR sequences. b) The different regulatory elements described in panel A drive expression of the Gal4, GSGal4 or QF2 drivers. The sRh1-Gal4, mRh1-Gal4, Rh1-GSGal4 and Rh1-QF2 drivers were generated in this study, and compared with the Rh1-Gal4, GMR-Gal4 and longGMR-Gal4 drivers available from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center

Here, we focused on developing Gal4 drivers that were specific to outer photoreceptors but had varied expression levels compared to the existing Rh1-Gal4 drivers. To do this, we used two fragments of the ninaE promoter that had previously been shown to control photoreceptor-specific expression but at much lower levels than that of the full-length region[36]. The smaller fragment (sRh1) consists of 189 bp of the ninaE promoter (3 R:19888134–19888322, ninaE −120/+67) and the larger fragment (mRh1) consists of 512 bp (3 R: 19888145–19888656), ninaE −450/+62) (Figure 1(a)). These two ninaE fragments, termed small (s) and medium (m), control Gal4 expression using the Integrase Swappable In vivo Targeting Element (INSITE) system[19]. INSITE allows for the Gal4 activator to be swapped out for other activators from an established library of activator donor plasmids using a system of Cre-Lox and phi31C recombination, all while maintaining the regulatory element. Thus, the sRh1-Gal4 and mRh1-Gal4 drivers described in this study can be readily crossed with other flies to generate Gal80, -QF or -LexA drivers, as necessary[37].

Next, we developed inducible Gal4 drivers for eye specific expression. An inducible GMR-GSGal4 driver had previously been developed[38] and is available from the BDSC. Gene-switch Gal4 (GSGal4) contains the GMR regulatory elements, as described for GMR-Gal4 above, that control expression of a fusion protein consisting of a mutant human progesterone receptor, the DNA binding domain of GAL4, and the activating domain of herpes simplex VP16 (GSGal4)[9]. Upon feeding flies with RU486 (mifepristone), GSGal4 is activated and results in the expression of target genes under control of the UAS regulatory element [17,39]. GMR-GSGal4 expression is reported to be specific to the eye and ocelli in adult flies[27]. We created Rh1-GSGal4 driver lines for outer photoreceptor-specific inducible expression using the GSGal4 fusion protein under the control of a 3.8 kb fragment of the promoter (3 R:19890993–19888031) and 3ʹ (3 R: 19886438–19885743) regulatory elements of ninaE (Figure 1).

Finally, we generated QF2 drivers expressed in outer photoreceptors to provide an alternative binary expression system to Gal4. To generate Rh1-QF2 driver lines, we placed the QF2 gene under the control of the same 3.8 kb fragment containing the 5ʹ and 3ʹ regulatory elements of ninaE used for Rh1-GSGal4 (Figure 1).

We used targeted ΦC31 integration for the sRh1-Gal4 and mRh1-Gal4 drivers to generate lines on chromosomes 3 and 2, respectively[40] (Table 2). We then used P-element integration to generate multiple lines for both the Rh1-GSGal4 and Rh1-QF2 drivers on different chromosomes. We selected at least one line on each of the chromosomes 2 and 3 for follow-up characterization of each driver, and determined the insertion position of each transgene using inverse PCR (Table 2). In addition, since the insertion position for the GMR-Gal4, GMR-GSGal4, longGMR-Gal4 and Rh1-Gal4 drivers had not previously been described and was not available on FlyBase, we also characterized the insertion position for each of these transgenes using inverse PCR (Table 2). As expected, all driver transgenes map to single insertion sites on the predicted chromosome. Importantly, no insertion sites mapped near genes that are involved in eye development or function.

Characterization of driver expression pattern in the adult eye using a fluorescent reporter

Next, we examined the expression pattern of each of our newly generated drivers in the adult eye and compared this with the available GMR-, longGMR- and Rh1-Gal4 drivers. To do this, we crossed each of the Gal4 and QF2 driver lines with 20XUAS-6XmCherry (UAS-mCherry) or 10XQUAS-6XmCherry (QUAS-mCherry) reporter lines, respectively, and examined the pattern of red fluorescence in live 10-day-old adult male eyes using confocal microscopy. Three independent flies were examined for each driver cross, and conclusions regarding cell-type expression were determined by evaluating the mCherry expression across the whole eye. Due to the curvature of the eye, the images presented show a progression from more distal outer ommatidial cells to the more proximal R cells along a centre in radius. Likely due to the various levels of expression and therefore fluorescence intensity, differing laser strengths were used to image samples. Therefore, fluorescence intensity should only be compared between cells within the eye of a single fly, rather than between genotypes. To ensure that the higher laser strengths did not result in the misinterpretation of background signal, we have displayed our control lines (UAS/QUAS-mCherry alone) at the highest laser strength used. Using this approach, we observed GMR-Gal4 driven mCherry expression in R1-R8 photoreceptors, as well as in the surrounding IOCs (Figure 2(b)). When we compared the mCherry expression pattern driven by longGMR-Gal4 with GMR-Gal4, these were remarkably similar apart from the more obvious R cell patterning in longGMR-Gal4. In contrast to GMR-Gal4 and longGMR-Gal4, the Rh1-Gal4 driver resulted in mCherry expression specifically in R1 – R6 cells, as previously published, with no expression observed elsewhere in the eye (Figure 2(b)). Although the ninaE regulatory elements used to develop the sRh1-Gal4 and mRh1-Gal4 were originally described as photoreceptor-specific[36], these drivers show a broader expression profile in multiple cell types in the eye. The sRh1-Gal4 driver resulted in distinct mCherry fluorescence in IOCs and relatively dim signal in photoreceptor cells. In contrast, the mRh1-Gal4 driver had an mCherry expression profile closely resembling that of Rh1-Gal4; however, sparse mCherry fluorescence in IOCs was also present. Strikingly, the newly developed Rh1-QF2 driver resulted in R1 – R6 photoreceptor specific mCherry expression, similar to that observed in the Rh1-Gal4 driver (Figure 2(c)). Thus, the Rh1-Gal4 and Rh1-QF2 drivers are both specifically expressed in the outer photoreceptors R1 – R6, but not in other cells in the adult eye. Surprisingly, our newly developed sRh1-Gal4 and mRh1-Gal4, although expressed in photoreceptors, are also expressed in other cells of the adult eye. Although the longGMR-Gal4 driver was originally suggested to be more photoreceptor specific than GMR-Gal4, under our conditions, both longGMR-Gal4 and GMR-Gal4 show expression in multiple cell types in the adult eye including photoreceptors and the IOCs.

Figure 2.

Rh1 drivers are expressed specifically in adult photoreceptors, whereas GMR, longGMR, sRh1 and mRh1 drivers are expressed throughout the adult eye. The indicated Gal4 and QF2 driver lines were crossed to UAS-mCherry or 10XQUAS-QUAS-mCherry flies, respectively, and confocal microscopy was conducted on 10-day-old live adult male progeny. Representative images for each driver are shown (n = 3). Inset images show a magnified section of the eye. (a) Schematic depicting the location of cells in each ommatidium at a similar focal plane to that shown in each image. mCherry expression pattern for the (b) GMR-Gal4, longGMR-Gal4, sRh1-Gal4, mRh1-Gal4, and Rh1-Gal4 drivers, relative to the UAS-mCherry control; (c) Rh1-QF2 drivers and QUAS-mCherry control; (d) GMR-GSGal4 + drug versus vehicle only control. Open and closed arrow heads point to interommatidial cells (IOCs) and R cells, respectively. Scale bar, 50 µm

To test the cell specificity of the inducible GSGAL4 drivers, we used a similar approach by crossing GSGAL4 driver lines to UAS-mCherry and imaging 10-day-old adult flies 24 hours after supplementing food with mifepristone. We observed GMR-GSGal4 driven reporter fluorescence in all photoreceptor cells as well as in the pigment cells (Figure 2(d)). However, mCherry expression was also present in flies fed vehicle only, suggesting that GSGAL4 is also active independent of drug treatment in the eye (Figure 2(d)). Unfortunately, we were unable to detect reporter fluorescence in our Rh1-GSGal4 lines, suggesting that the expression of, or induction by, this driver is below the limits of detection using the fluorescent reporter. Due to these results, we did not include the GMR-GSGal4 or Rh1-GSGal4 drivers in our developmental expression characterization (see next section).

3. Characterization of Gal4 and QF2 driver expression pattern during development

To further characterize these eye drivers, we sought to determine their expression patterns throughout different stages of fly development. Using the same genetic approach to evaluate the adult eye expression pattern, each driver line was crossed to the appropriate mCherry reporter. Late stage embryos (Figure 3), wandering third instar larvae (Figure 4), and late-stage pupae (Figure 5) were then imaged using fluorescence microscopy to examine the expression pattern of each driver in various tissues at these three developmental stages. We imaged whole embryos and larvae to obtain a broad overview of the expression pattern of each driver in these developmental stages, and thus these images only provide general information about the expression pattern without the high spatial resolution like that obtained using the confocal imaging (Figure 2). Similar to imaging conducted on the adult eye, differing laser strengths were used between drivers and developmental stages. As such, mCherry fluorescence intensity should only be evaluated for expression pattern, and not as a readout for expression level between driver lines. The relative expression level between drivers was evaluated in adult heads using a quantitative luciferase assay, which will be described in the next section (see Figure 6).

Figure 3.

GMR, longGMR, sRh1 and mRh1 drivers are expressed in embryonic tissue, whereas Rh1 drivers are not. The indicated GAL4 and QF2 driver lines were crossed to UAS-mCherry or QUAS-mCherry flies, respectively, and fluorescent microscopy was conducted on late-stage embryos. (a, b) mCherry and (A’, B’) merged mCherry, DAPI and transmitted light (TL) images for (A, A’) GMR-Gal4, longGMR-Gal4, sRh1-Gal4, mRh1-Gal4, Rh1-Gal4, UAS-mCherry control and (B, B’) Rh1-QF2 drivers and QUAS-mCherry control. Abbreviations for labelled tissues are as follows: (CNS) central nervous system; (VNC) ventral nerve cord; (PN) peripheral nervous system; (BO) Bolwig’s organ; (RG) ring gland. Scale bar, 100 µm

Figure 4.

GMR, longGMR, sRh1 and mRh1 drivers are expressed in various larval tissues, whereas Rh1 drivers have no detectable expression. The indicated GAL4 and QF2 driver lines were crossed to UAS-mCherry or QUAS-mCherry flies, respectively, and fluorescent microscopy was conducted on wandering third instar larvae. (a) mCherry and (A’) merged mCherry, DAPI and transmitted light (TL) images for (A) UAS-mCherry control, GMR-Gal4, longGMR-Gal4, sRh1-Gal4, mRh1-Gal4, Rh1-Gal4, QUAS-mCherry control, and Rh1-QF2 drivers. Abbreviations for labelled tissues are as follows: (VNC) ventral nerve cord; (EAD) eye antennal disc; (SG) salivary glands; (t) tracheal system; Scale bar, 500 µm

Figure 5.

GMR, longGMR and Rh1 drivers are expressed eye-specifically, while sRh1 and mRh1 are expressed elsewhere in the late stage pupal head and brain. The indicated GAL4 and QF2 driver lines were crossed to UAS-mCherry or QUAS-mCherry flies, respectively, and fluorescent microscopy was conducted on dissected late stage pupal heads. (a, b) mCherry and (A’, B’) merged mCherry and transmitted light (TL) images for (A, A’) GMR-Gal4, longGMR-Gal4, sRh1-Gal4, mRh1-Gal4, Rh1-Gal4, UAS-mCherry control, and (B, B’) Rh1-QF2 drivers and QUAS-mCherry control. Abbreviations for labelled tissues are as follows: (CB) central brain; (l) lamina; (a) antenna; (MP) mouth parts. Scale bar, 100 µm

Figure 6.

Gal4 drivers expressed in multiple cell types induce higher expression levels relative to photoreceptor-specific Gal4 or QF2 drivers. The indicated eye- or photoreceptor-specific driver lines were crossed to flies containing UAS-Luc (QUAS-Luc for QF2 drivers), and luciferase activity was assayed in heads from adult male progeny expressing UAS-Luc under control of the indicated driver at 10 days post-eclosion. Data are shown as bar plots of means with individual biological replicates overlaid as dots (n = 4, 2 heads/experiment). Luciferase activity for the (a) GMR-Gal4, longGMR-Gal4; (b) Rh1-Gal4, sRh1-Gal4, and mRh1-Gal4 compared to UAS-Luc alone; (c) photoreceptor-specific Rh1-QF2 drivers on chromosomes 2 or 3, compared to QUAS-Luc alone

In embryos, we observed fluorescence for several of the eye drivers.GMR-Gal4 had mCherry expression in the Bolwig’s organ and Ring gland (Figure 3(a)), while longGMR-Gal4 mCherry expression also appeared in the Bolwig’s organ, as well as all major regions of the central nervous system, which include the central brain, optic lobes and ventral nerve cord (Figure 3(a)). Interesting, both the sRh1-Gal4 and mRh1-Gal4 drivers showed mCherry expression in the sensory neurons of the peripheral nervous system (Figure 3(a)). In contrast, we did not detect mCherry expression in either the Rh1-Gal4 or Rh1-QF2 drivers (Figure 3(a,b)). Thus, four of the drivers designed for expression in the developing and/or adult eye also show expression in late-stage embryos: GMR-Gal4, longGMR-Gal4, sRh1-Gal4, and mRh1-Gal4.

We next characterized the pattern of mCherry expression controlled by each driver in whole mounted wandering third instar larvae (Figure 4). GMR-Gal4 resulted in mCherry expression in the eye antennal imaginal disc behind the propagating wave of the morphogenic furrow that begins to pattern the developing eye, in the optic stalk and optic lobe growth cones, as well as the trachea. LongGMR-Gal4 resulted in mCherry expression in the salivary glands, tissue around the cephaloskeleton (mouth parts) and central nervous system (data for central nervous system not shown but available from PURR; see Data Availability). Interestingly, sRh1-Gal4 also resulted in mCherry expression in salivary glands, which was so strong that salivary glands appeared violet in colour under the dissecting scope (data not shown). mRh1-Gal4 mCherry expression appeared in the ventral nerve cord and was also visible in the axonal projections and external sensory neurons of the peripheral nervous system. Similar to embryos, we did not observe any detectable mCherry expression driven by either the Rh1-Gal4 driver or any of the Rh1-QF2 drivers. Thus, as in embryos, GMR-Gal4, longGMR-Gal4, sRh1-Gal4, and mRh1-Gal4 show expression patterns in additional larval tissues that are not related to eye development.

Finally, we investigated the expression pattern of these drivers in late stage pupal heads in which all cells of the eye have been terminally differentiated. These images provide data on the expression pattern in the eye, and within other tissues in the head including the brain. Using this approach, we observed strong mCherry expression in the eye and ocelli of GMR-Gal4 and longGMR-Gal4 drivers (additional data for ocelli is available in original z-stack images in PURR; see Data Availability) (Figure 5). LongGMR-Gal4 also resulted in expression in small groups of cells in the mouth parts. We also observed expression of mCherry in the eyes of sRh1-Gal4 flies, as well as in various regions of the antenna and mouth parts. mRh1-Gal4 also resulted in mCherry expression in cells of the eye, as well as the lamina and central brain. As expected, Rh1-QF2 drivers resulted in mCherry expression in eyes, without detectable expression in other regions of the head. Although some mCherry signal appears in the brain and punctae around the mouth parts in these images, comparison of all biological replicates with the QUAS control (-QF2) indicates that the weak signal is due to background from the QUAS transgene. Surprisingly, we could not detect fluorescence in the eye using the Rh1-Gal4 driver, although confocal images in live flies confirmed that Rh1-Gal4 drives expression in outer photoreceptors (Figure 2). The lack of detection of Rh1-Gal4 may reflect its relatively low expression level (~fivefold lower than sRh1-Gal4 in head extracts) when compared with the other drivers in this study (see below). Although we cannot exclude the possibility that Rh1-Gal4 or the other drivers are expressed in other cells in the head, or indeed in other tissues during development, this expression level is below the detection of the fluorescent reporter used in our assays.

Characterization of driver expression levels in the adult head

We next sought to characterize the relative expression level of each of the newly generated drivers in the adult eye, as compared with the currently available eye-specific drivers. To do this, we crossed the Gal4 and QF2 driver lines with UAS-Luc and QUAS-Luc respectively and performed luciferase assays on whole head extracts of 10-day-old male flies. Because we used whole head extracts for these quantitative luciferase assays, these data represent the sum of expression in all cell types within the adult head including both the eye and brain. Using this approach, GMR-Gal4 and longGMR-Gal4 showed the highest luciferase activity of all the eye drivers (Figure 6(a)). Our sRh1-Gal4 and mRh1-Gal4 resulted in a 5- and 20-fold higher luciferase activity than the full-length Rh1-Gal4 driver, respectively (Figure 6(b)). Since we observed expression of the sRh1-Gal4 and mRh1-Gal4 drivers elsewhere in the adult head, these data cannot be compared directly with Rh1-Gal4 to determine relative photoreceptor expression. However, all three of these drivers were expressed at least an order of magnitude lower than GMR-Gal4 and longGMR-Gal4 (see y axis scale differences between Figure 6(a-c)). We note that the insertion site of Rh1-Gal4 is approximately 5 kb from the nearest gene, suggesting that position effects could account for the lower levels of driver activity than expected relative to the sRh1-Gal4 and mRh1-Gal4 drivers, which were generated by ΦC31 integrase-mediated transformation. We also characterized multiple independently transformed Rh1-QF2 lines (different integration sites on chromosomes 2 and 3), all of which resulted in similar luciferase activity (Figure 6(c)). Unexpectedly, the expression levels of these drivers are nearly 30-fold higher than the Rh1-Gal4 driver, suggesting that the Rh1-QF2 driver provides a robust tool for inducing high levels of transgene expression specifically in the outer photoreceptors of the adult eye. This Rh1-QF2 driver contains additional 3ʹ regulatory elements (see Figure 1), which might also increase the expression of this driver relative to Rh1-Gal4.

Finally, to characterize the expression levels of our GSGal4 drivers we first established the drug feeding conditions for maximal transgene induction. To do this, we crossed GMR-GSGal4 with UAS-Luc flies and fed seven-day-old adult progeny for either 24, 48 or 72 hours and then performed luciferase activity assays from head extracts. We observed maximum luciferase activity at 24 hours, with a slight decrease in luciferase activity after longer duration feedings (Figure 7(a)). We next compared the GMR-GSGal4 driver with our Rh1-GSGal4 driver. Both drivers were crossed to UAS-Luc and nine-day-old adult progeny were fed drug for 24 hours followed by luciferase activity assays. Although all GSGal4 driver lines had statistically significant induction when treated with drug compared to vehicle control, luciferase activity in the Rh1-GSGal4 lines was 7- to 8-fold lower than that of the GMR-GSGal4 line, which itself is approximately threefold lower than Rh1-Gal4, and more than 300-fold lower than either GMR-Gal4 or longGMR-Gal4 (Figure 7(b)).

Figure 7.

Gene Switch drivers induce gene expression weakly in the adult eye. (a) GMR-GSGal4 flies were crossed to UAS-Luc flies and seven-day old adult progeny were fed food supplemented with RU486 or vehicle only for 24, 48, 72 hours followed by luciferase activity assays on heads to establish maximum GSGal4 induction. Data are shown as bar plots of means with individual biological replicates overlaid as dots (n = 2, 2 heads/experiment) (b) GMR-GSGAL4 and Rh1-GSGal4 flies crossed to UAS-Luc flies and resulting nine-day old progeny were fed food supplemented with RU486 for 24 hours or vehicle only followed by luciferase activity assays on heads. Data are shown as bar plots of means with individual biological replicates overlaid as dots (n = 4, 2 heads/experiment). p-value (**<0.005, ****<0.00005), Students t-test

Discussion

In this study, we characterized the expression and cell specificity of both previously available and newly created Drosophila eye- and photoreceptor-specific drivers with the goal of assembling a binary expression toolkit for adult Drosophila eye expression. We compared several of the available Gal4 drivers from the BDSC for expression in the eye (GMR-Gal4, Long-GMR-Gal4 and Rh1-Gal4), with Gal4 drivers generated by our lab (sRh1-Gal4, mRh1-Gal4, Rh1-QF2). Although many of these drivers have been best characterized in terms of their expression patterns in the developing and/or adult eye, all, except for Rh1-Gal4 and Rh1-QF2, had expression in additional cell types. Specifically, GMR-Gal4 expression was detected in the embryo Bolwig’s organ and ring gland, as well as the trachea of third instar larvae. To our knowledge, we are the first to identify GMR-Gal4 expression in the late embryo ring gland, while previous reports have also noted the expression in the Bolwig’s organ and larval trachea[13]. Interestingly, we did not detect the previously described expression of GMR-Gal4 in the central nervous system of larvae[13] or in the wing and leg imaginal discs[28].This may be due to the limitations of our imaging technique, where the high mCherry fluorescence in specific tissues masks the weaker mCherry fluorescence in more lowly expressing tissues. Intriguingly, a previous report also showed that two GMR-Gal4 lines with different integration sites have slight differences in expression pattern[13], suggesting that the local chromatin landscape or the expression level of GMR-Gal4 may also play a role in its expression pattern. Similar to GMR-Gal4, longGMR-Gal4 resulted in high levels of expression in all cells of the adult eye. As the initial report noted, the expression of longGMR-Gal4 appears to be more photoreceptor specific as seen by the higher relative mCherry expression in the R cells of this driver when compared to other cells in the eye[32]. Unlike GMR-Gal4, longGMR-Gal4 lacks characterization for expression outside of the adult eye. We report broad developmental expression similar to GMR-Gal4 with some marked differences; longGMR-Gal4 lacked the larval trachea expression of GMR-Gal4 but showed strong expression in larval salivary glands and mouth parts as well as in the central nervous system of embryos. However, due to the strong mCherry expression driven by longGMR-Gal4 in salivary glands, expression in the eye-antennal imaginal disc is likely masked in our imaging of the whole larvae. Future dissections of GMR-Gal4 and longGMR-Gal4 larvae could further characterize the developmental expression pattern of these drivers using this strong mCherry reporter. Thus, while GMR-Gal4 and longGMR-Gal4 provide suitable tools for expressing transgenes broadly throughout the adult eye, caution should be used in attributing their effects to expression in particular cell types.

Because we also observed broad expression patterns for sRh1-Gal4 and mRh1-Gal4 drivers in the adult eye, pupal head and other larval and embryonic tissues, while Rh1-Gal4 is specific to the R1-R6 cells in the adult eye, we suspect that a complex group of regulatory elements in the ninaE promoter contribute to its outer photoreceptor-specific expression. Both the sRh1-Gal4 and mRh1-Gal4 include the TATA box and another short regulatory element named the Rhodopsin Conserved Sequence I (RCSI). This element has been shown to bind the Pax6 proteins eyeless (ey) and twin of eyeless (toy) [41,42], as well as the homeodomain protein Pph13[43]. Together, these two sequence elements have been shown to be necessary for the general photoreceptor specificity of all rh genes [36,44,45]. Therefore, we were surprised to find much broader expression profiles for the sRh1-Gal4 and mRh1-Gal4 drivers than expected. Moreover, sRh1-Gal4 and mRh1-Gal4 have multiple differences in expression throughout development and in the adult head and eye. For example, mRh1-Gal4 has more obvious photoreceptor expression in the adult eye compared to sRh1-Gal4. This and other expression differences likely result from the 300 nucleotides of additional upstream ninaE enhancer contained within mRh1-Gal4, which also includes the entirety of the gl binding site. Multiple conserved elements in the ninaE promoter remain uncharacterized[42], which upon additional testing may yield promising eye and photoreceptor-specific drivers of various expression levels. Further, neither sRh1-Gal4 nor mRh1-Gal4 results in obvious rough eye phenotypes in homozygous flies. This is unlike the more highly expressed GMR-Gal4 driver, which has a rough eye phenotype in homozygous flies or in heterozygous flies reared in temperatures exceeding 25°C[46], making these drivers appealing alternatives for expressing transgenes broadly in the adult eye.

In this study, we incorporated the Q-system into our expanding toolkit of eye drivers. Rh1-QF2 to our knowledge is the first characterized photoreceptor-specific QF2 driver. Surprisingly, Rh1-QF2 activates photoreceptor-specific expression nearly 30-fold higher than that of the currently available Rh1-Gal4 driver. While Rh1-Gal4 uses a 3 kb fragment of the ninaE promoter as its regulatory element, Rh1-QF2 includes both the 5ʹ and 3ʹ regulatory elements, suggesting that the 3ʹ regulatory element may be important for high expression level. Rh1-QF2 opens the door to an exciting alternative to the currently available Gal4/UAS-based expression systems because of the many advantages the Q-system offers. Additional optimization of the temporal regulation of eye-specific QF2 drivers as well as the integration of both Gal4 and QF2 drivers will further expand the utility of these systems for complex eye-specific expression.

To allow for inducible photoreceptor-specific expression, we created a Rh1-GSGal4 driver and compared its temporal induction in adult eyes with that of a currently available GMR-GSGal4 driver. We showed that both Rh1-GSGal4 and GMR-GSGal4 induced significant expression of the luciferase reporter upon RU feeding. However, Rh1-GSGal4 driven expression of our mCherry reporter assay was under the detection limit of our microscopy analysis, and while drug induced GMR-GSGal4 resulted in mCherry fluorescence, mCherry was also detected in the vehicle only control. Therefore, while we and others have reported GMR-GSGal4 induced expression in the adult eye, it appears that limitations may exist for robust GSGal4 activation in particular cell types in this tissue, such as photoreceptors.

In this study, we have systematically characterized various binary expression system drivers. We have summarized our findings for the expression patterns of these drivers throughout development (Figure 8(a)) as well as their expression patterns in the adult eye and expression levels in the adult head (Figure 8(b)). This allows for the straightforward comparison of each driver’s relative expression and cell specificity. Together, these fly stocks represent a useful binary expression toolkit for adult Drosophila eye expression.

Figure 8.

Overview of Drosophila Gal4 and QF2 drivers for fine-tuned eye- and photoreceptor- specific expression. (a) Summary table describing each driver’s expression pattern in embryo, wandering third instar larvae, pupal heads, and adult eyes. (√*) indicates expression patterns from data not shown in the figures of this manuscript but acquired in these data sets publicly available from the associated Purdue University Research Repository (PURR) website (see Data Availability). (b) Schematic of an adult Drosophila ommatidium cross section colour coded by cell type; yellow, R1 – R6 photoreceptor cells; green, R7 photoreceptor cell; purple, R8 photoreceptor cell; red, secondary pigment cells; pink, tertiary pigment cells; blue, sensory bristles. The key displays each driver’s cell-specific expression and is defined as follows: (√), expression; (-), no expression; (ND), not defined. The relative expression between drivers assessed by luciferase activity from head extracts is shown to the right using a scale of one (low) to five (high) bars

Acknowledgments

We thank J.E. O’Tousa and J. Rister for plasmids. We thank Dr. Andy Schaber for assistance with confocal microscopy, and Dr. Donald Ready for assistance with Drosophila eye microscopy and critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by NIH Grants [R01EY024905 and R21EY031024] to VW. Fly images were obtained at the Bindley Bioscience Imaging Facility, Purdue University, supported by [NIH P30 CA023168] to the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research. Fly stocks from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center [NIH P40OD018537] and information from FlyBase [NIH U41 HG000739] were used in this study.

Data availability

All raw and supporting data (confocal and fluorescence microscopy images, luciferase activity data, plasmid maps/sequences) have been deposited at the Purdue University Research Repository (PURR) as a publicly available, archived data set and can be accessed using: doi:10.4231/6AF9-3085.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Cagan R. Principles of Drosophila eye differentiation. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2009;89:115–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ugur B, Chen K, Bellen HJ. Drosophila tools and assays for the study of human diseases. Dis Model Mech. 2016;9:235–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].McGurk L, Berson A, Bonini NM. Drosophila as an in vivo model for human neurodegenerative disease. Genetics. 2015;201:377–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Newsome TP, Asling B, Dickson BJ. Analysis of Drosophila photoreceptor axon guidance in eye-specific mosaics. Development. 2000;127:851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Viktorinová I, Wimmer EA. Comparative analysis of binary expression systems for directed gene expression in transgenic insects. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;37:246–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Webster N, Jin JR, Green S, et al. The yeast UASG is a transcriptional enhancer in human hela cells in the presence of the GAL4 trans-activator. Cell. 1988;52:169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Duffy JB. GAL4 system in Drosophila: a fly geneticist’s Swiss army knife. Genesis. 2002;34:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].McGuire SE, Le PT, Osborn AJ, et al. Spatiotemporal rescue of memory dysfunction in Drosophila. Science. 2003;302:1765–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Osterwalder T, Yoon KS, White BH, et al. A conditional tissue-specific transgene expression system using inducible GAL4. PNAS. 2001;98:12596–12601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Potter CJ, Tasic B, Russler EV, et al. Q system: a repressible binary system for transgene expression, lineage tracing, and mosaic analysis. Cell. 2010;141:536–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dillon ME, Wang G, Garrity PA, et al. Review: thermal preference in Drosophila. J Therm Biol. 2009;34:109–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ready DF, Hanson TE, Benzer S. Development of the Drosophila retina, a neurocrystalline lattice. Dev Biol. 1976;53:217–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ray M, Sc LAKHOTIA. The commonly used eye-specific sev-GAL4 and GMR-GAL4 drivers in Drosophila melanogaster are expressed in tissues other than eyes also. J Genet. 2015;94:407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kramer JM, Staveley BE. GAL4 causes developmental defects and apoptosis when expressed in the developing eye of Drosophila melanogaster. Genet Mol Res. 2003;2:43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Huang AM, Rehm EJ, Rubin GM. Recovery of DNA sequences flanking P-element insertions in Drosophila: inverse PCR and plasmid rescue. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2009; 2009:pdb.prot5199. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [16].Riabinina O, Luginbuhl D, Marr E, et al. Improved and expanded Q-system reagents for genetic manipulations. Nat Methods. 2015;12:219–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Roman G, Endo K, Zong L, et al. P{Switch}, a system for spatial and temporal control of gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster. PNAS. 2001;98:12602–12607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rister J, Razzaq A, Boodram P, et al. Single–base pair differences in a shared motif determine differential Rhodopsin expression. Science. 2015;350:1258–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gohl DM, Silies MA, Gao XJ, et al. A versatile in vivo system for directed dissection of gene expression patterns. Nat Methods. 2011;8:231–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Stegeman R, Hall H, Escobedo SE, et al. Proper splicing contributes to visual function in the aging Drosophila eye. Aging Cell Internet] 2018. [cited 2020 May19]; 17:e12817. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6156539/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dourlen P, Levet C, Mejat A, et al. The tomato/GFP-FLP/FRT method for live imaging of mosaic adult Drosophila photoreceptor cells. J Vis Exp. 2013;124:e50610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rothwell WF, Sullivan W. Fixation of Drosophila embryos. CSH Protoc 2007; 2007:pdb.prot4827. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [23].O’Tousa JE, Baehr W, Martin RL, et al. The Drosophila ninaE gene encodes an opsin. Cell. 1985;40:839–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kumar JP, Ready DF. Rhodopsin plays an essential structural role in Drosophila photoreceptor development. Development. 1995;121:4359–4370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hall H, Medina P, Cooper DA, et al. Transcriptome profiling of aging Drosophila photoreceptors reveals gene expression trends that correlate with visual senescence. BMC Genomics. 2017;18:894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ellis MC, O’Neill EM, Rubin GM. Expression of Drosophila glass protein and evidence for negative regulation of its activity in non-neuronal cells by another DNA-binding protein. Development. 1993;119:855–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Freeman M. Reiterative use of the EGF receptor triggers differentiation of all cell types in the Drosophila eye. Cell. 1996;87:651–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Li W-Z, Li S-L, Zheng HY, et al. A broad expression profile of the GMR-GAL4 driver in Drosophila melanogaster. Genet Mol Res. 2012;11:1997–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cherbas L, Hu X, Zhimulev I, et al. EcR isoforms in Drosophila: testing tissue-specific requirements by targeted blockade and rescue. Development. 2003;130:271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hrdlicka L, Gibson M, Kiger A, et al. Analysis of twenty-four Gal4 lines in Drosophila melanogaster. Genesis. 2002;34:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Freeman M. Cell determination strategies in the Drosophila eye. Development. 1997;124:261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wernet MF, Labhart T, Baumann F, et al. Homothorax switches function of Drosophila photoreceptors from color to polarized light sensors. Cell. 2003;115:267–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Mazzoni EO, Celik A, Wernet MF, et al. Iroquois complex genes induce co-expression of rhodopsins in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Pollock JA, Benzer S. Transcript localization of four opsin genes in the three visual organs of Drosophila; RH2 is ocellus specific. Nature. 1988;333:779–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Mollereau B, Wernet MF, Beaufils P, et al. A green fluorescent protein enhancer trap screen in Drosophila photoreceptor cells. Mech Dev. 2000;93:151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mismer D, Rubin GM. Analysis of the promoter of the ninaE Opsin gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1987;116:565–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Riabinina O, Potter CJ. The Q-system: a versatile expression system for Drosophila. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1478:53–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Roman G, Davis RL. Conditional expression of UAS-transgenes in the adult eye with a new gene-switch vector system. genesis. 2002;34:127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wang Y, O’Malley BW, Tsai SY, et al. A regulatory system for use in gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8180–8184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bateman JR, Lee AM, Wu C-T. Site-specific transformation of Drosophila via φC31 integrase-mediated cassette exchange. Genetics. 2006;173:769–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sheng G, Thouvenot E, Schmucker D, et al. Direct regulation of rhodopsin 1 by Pax-6/eyeless in Drosophila: evidence for a conserved function in photoreceptors. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1122–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Papatsenko D, Nazina A, Desplan C. A conserved regulatory element present in all Drosophila rhodopsin genes mediates Pax6 functions and participates in the fine-tuning of cell-specific expression. Mech Dev. 2001;101:143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Mishra M, Oke A, Lebel C, et al. Pph13 and Orthodenticle define a dual regulatory pathway for photoreceptor cell morphogenesis and function. Development. 2010;137:2895–2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mismer D, Rubin GM. Definition of cis-acting elements regulating expression of the Drosophila melanogaster ninae opsin gene by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis. Genetics. 1989;121:77–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fortini ME, Rubin GM. Analysis of cis-acting requirements of the Rh3 and Rh4 genes reveals a bipartite organization to rhodopsin promoters in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 1990;4:444–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].FlyBase Reference Report: freeman, 1996.10.3, GMR-GAL4. [Internet]. [cited 2021. March 14]; Available from: http://flybase.org/reports/FBrf0089999.html#reference

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All raw and supporting data (confocal and fluorescence microscopy images, luciferase activity data, plasmid maps/sequences) have been deposited at the Purdue University Research Repository (PURR) as a publicly available, archived data set and can be accessed using: doi:10.4231/6AF9-3085.