We are more than 1 year into the COVID-19 pandemic and the need for better treatments for patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 remains great. Despite clear improvements in care, mortality for severely ill patients remains unacceptably high. Thus far, the only agents that have consistently been shown to reduce mortality in hypoxaemic patients are systemic corticosteroids (mainly dexamethasone).1 Yet, since early in the pandemic, modulating the immune response beyond steroids has been the source of a great deal of scientific attention, with the role of repurposed IL-6-blocking agents reported in a number of observational studies and randomised controlled trials.

In The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, two additional randomised controlled trials report results from IL-6 blockade in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: one using tocilizumab in India between May and August, 2020,2 and the other using sarilumab in 11 countries between March and July, 2020.3 Arvinder Soin and colleagues randomly assigned 180 patients to receive either tocilizumab plus standard care or standard care alone. François-Xavier Lescure and colleagues randomly assigned 420 patients to receive either sarilumab or placebo. Neither study achieved its primary outcome of either progression of disease up to day 14 for the tocilizumab study or time to clinical improvement in the sarilumab study (defined as an improvement of at least two points on a seven point ordinal scale). Neither study was powered for mortality. Yet, both make a useful contribution to our growing understanding of the role of IL-6 blockade in COVID-19.

First, having trials conducted in settings outside of western Europe and North America is fundamental for generalisability. Both trials were done in settings outside of regions where the bulk of the other IL-6 data is emerging. Second, given impending supply-chain shortages for tocilizumab, more data on sarilumab is required. Indeed, establishing whether there is a class effect or dose effect of IL-6 blockade on improving mortality is a crucial question to answer. Third, both trials add important safety data to the literature, bolstering estimates of the relative short-term safety of these agents in diverse settings and diverse populations.

Given the speed with which these trials were set up and implemented, some concerns are inevitable. The significance of a transition from a moderate to severe state in the study by Soin and colleagues is of questionable clinical significance in an open-label trial where the outcome could be achieved by a difference in oxygen saturation of a few percentage points. The use of a second dose for “clinician concern” in both trials, as with many of the IL-6 trials, is difficult to interpret as a post-randomisation event, and particularly so in the open-label context. The predominance of men in both trials reflects the burden of patients admitted to hospital (>80% in the tocilizumab study); the need for a better understanding of potential sex differences in treatment effect is underappreciated and could be the focus of targeted investigations in future.

One of the challenges in interpreting the COVID-19 literature is that the standard of care has been rapidly evolving. Changes in supportive care, coupled with evolving therapeutic evidence, mean that trials that began earlier in the pandemic could have markedly different standards of care. For example, treatment with steroids has now become standard for patients with hypoxaemia and treatment with hydroxychloroquine, which was often used earlier in the pandemic, has stopped in most regions.1, 4 These differences can be seen in these two studies, with steroid use more common in the tocilizumab study (91%) than in the sarilumab study (42% concomitant use at baseline, with a peak of 70% at 13 weeks). In REMAP-CAP5 and RECOVERY,6 the two largest clinical trials of IL-6 blockade and the only trials to show a mortality reduction, the benefit seemed predominantly in patients who received steroids. Hence, the contribution of negative studies that examined IL-6 blockade in the absence of routine administration of steroids is very useful, but more challenging to interpret at this stage.

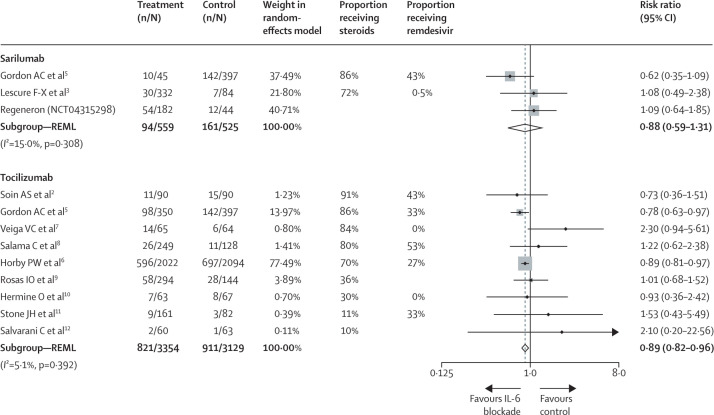

By including all trials based on individual publications,2, 3, 5 industry data, or the analysis presented in the RECOVERY manuscript,6 a conservative random-effects meta-analysis for patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (figure ) yields a risk ratio for mortality of 0·88 (95% CI 0·59–1·31) for sarilumab and 0·89 (0·82–0·96) for tocilizumab. Although the point estimates are very similar, the smaller sample size for sarilumab leaves room to question whether the effect of IL-6 blockade is a class effect, or whether specific agents have a differential benefit. Further data is expected on sarilumab (NCT04315298) but the total sample size will remain well below that for tocilizumab.

Figure.

Mortality risk in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 and treated with IL-6 inhibitors (tocilizumab or sarilumab) or a control

Heterogeneity between groups p=0·976. Studies are weighted in terms of their contribution to the overall estimate. Weights are taken from the random effects model using REML. The vertical dotted line shows the point estimate of the combined effect for reference to the null line (solid) and the point estimates of the individual studies. REML=restricted maximum likelihood.

Accepting that IL-6 blockade reduces mortality in patients like those in REMAP-CAP5 or RECOVERY,6 the question will inevitably become which populations are most likely to benefit. The absolute risk reduction (and corresponding number needed to treat) could vary considerably depending on the baseline risk of death. Given the worldwide burden of COVID-19, a dramatic upswing in prescribing will almost certainly challenge supply chains and health system budgets. It is not hard to imagine low-income and middle-income countries being disproportionately affected in both regards, and solutions to both steward and increase the available supply must be rapidly considered.

For informing these decisions, it is vital that all trial teams urgently participate in a carefully planned meta-analysis, incorporating analyses for heterogeneous treatment effects and standardised subgroups, and focusing on the important clinical outcome of mortality.

Definitions of treatment strategies for COVID-19 have improved greatly over the past 14 months. These two reports add more pieces to the puzzle, and they need to be integrated with all the evidence available to establish the best strategies for patients around the world.

Acknowledgments

SM is a co-investigator of REMAP-CAP and is the co-chair of the WHO Clinical Characterization and Management research committee for COVID-19. TCL reports salary support from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec—Sante.

References

- 1.Sterne JAC, Murthy S, Diaz JV, et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324:1330–1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soin AS, Kumar K, Choudhary NS, et al. Tocilizumab plus standard care versus standard care in patients in India with moderate to severe COVID-19-associated cytokine release syndrome (COVINTOC): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00081-3. published online March 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lescure F-X, Honda H, Fowler RA, et al. Sarilumab in patients admitted to hospital with severe or critical COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00099-0. published online March 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan H, Peto R, Henao-Restrepo A-M, et al. Repurposed antiviral drugs for Covid-19—interim WHO solidarity trial results. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:497–511. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2023184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon AC, Mouncey PR, Al-Beidh F, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor antagonists in critically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl Med J. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100433. published online Feb 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horby PW, Pessoa-Amorim G, Peto L, et al. Tocilizumab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): preliminary results of a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.02.11.21249258. published online Feb 11. (preprint). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Uncited References

- 7.Veiga VC, Prats JAGG, Farias DLC, et al. Effect of tocilizumab on clinical outcomes at 15 days in patients with severe or critical coronavirus disease 2019: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2021;372:n84. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salama C, Han J, Yau L, et al. Tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:20–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2030340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosas IO, Bräu N, Waters M, et al. Tocilizumab in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028700. published online Feb 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hermine O, Mariette X, Tharaux P-L, et al. Effect of tocilizumab vs usual care in adults hospitalized with COVID-19 and moderate or severe pneumonia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:32–40. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone JH, Frigault MJ, Serling-Boyd NJ, et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2333–2344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salvarani C, Dolci G, Massari M, et al. Effect of tocilizumab vs standard care on clinical worsening in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:24–31. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]