Abstract

Background

The MitraClip procedure was established as a therapeutic alternative to mitral valve surgery for symptomatic patients with severe mitral regurgitation (MR) at prohibitive surgical risk. In this study, the aim was to evaluate 5-year outcomes after MitraClip.

Methods

Consecutive patients undergoing the MitraClip system were prospectively included. All patients underwent clinical follow-up and transthoracic echocardiography.

Results

Two hundred sixty-five patients (age: 81.4 ± 8.1 years, 46.7% female, logistic EuroSCORE: 19.7 ± 16.7%) with symptomatic MR (60.5% secondary MR [sMR]). Although high procedural success of 91.3% was found, patients with primary MR (pMR) had a higher rate of procedural failure (sMR: 3.1%, pMR: 8.6%; p = 0.04). Five years after the MitraClip procedure, the majority of patients presented with reduced symptoms and improved functional capacity (functional NYHA class: p = 0.0001; 6 minutes walking test: p = 0.04). Sustained MR reduction (≤ grade 2) was found in 74% of patients, and right ventricular (RV) function was significantly increased (p = 0.03). Systolic pulmonary artery pressure (sPAP) was significantly reduced during follow-up only in sMR patients (p = 0.05, p = 0.3). Despite a pronounced clinical and echocardiographical amelioration and low interventional failure, 5-year mortality was significantly higher in patients with sMR (p = 0.05). The baseline level of creatinine (HR: 0.695), sPAP (HR: 0.96) and mean mitral valve gradient (MVG) (HR: 0.82) were found to be independent predictors for poor functional outcome and mortality.

Conclusions

Transcatheter mitral valve repair with the MitraClip system showed low complication rates and sustained MR reduction with improved RV function and sPAP 5 years after the procedure was found in all patients, predominantly in patients with sMR. Despite pronounced functional amelioration with low procedure failure, sMR patients had higher 5-year mortality and worse outcomes. Baseline creatinine, MVG, and sPAP were found to be independent predictors of poor functional outcomes and 5-year mortality.

Keywords: MitraClip, transcatheter mitral valve repair, long-term outcomes, mitral regurgitation

Introduction

Mitral regurgitation (MR) is the second most frequent valve disease, with an increasing prevalence in elderly (> 75 years) patients, and is related to reduced functional capacity and impaired quality of life. Transcatheter mitral valve repair (TMVR) with the MitraClip system (Abbot Vascular, Inc., Santa Clara, California) is a therapeutic alternative to mitral valve (MV) surgery in symptomatic patients with moderate to severe MR at prohibitive surgical risk [1–3]. TMVR with the MitraClip procedure can be successfully performed in patients with secondary MR (sMR) and primary MR (pMR) if mitral valve (MV) anatomy is suitable [4]. Its clinical efficacy and safety have been proven in a large number of patients [4–6].

Acute procedural success rates are reported to be up to 99% and are followed by symptomatic improvement in about 80% of cases [7].

A high baseline systolic pulmonary artery pressure (sPAP), an elevated baseline mitral valve mean gradient (MVG), concomitant chronic kidney disease, anemia, peripheral artery disease, and tricuspid regurgitation have been previously reported as independent predictors of poor short-term outcomes after MitraClip procedures [8, 9, 10].

Although more than 70,000 patients have undergone MitraClip procedures to date, data on long-term outcome and durability of MR reduction are limited, and parameters predicting adverse long-term outcomes are not well defined.

The objectives of the present study were to evaluate functional and echocardiographic long-term outcomes 5 years subsequent to transcatheter edge-to-edge mitral valve repair with the MitraClip procedure in a single high-volume center and assess predictors of poor outcomes.

Methods

Patients and endpoints

In this single-center study, consecutive patients undergoing TMVR with the MitraClip system were prospectively included. From February 2011 to February 2014 symptomatic (New York Heart Association [NYHA] functional class > II), and surgical high-risk patients with moderate-to-severe MR were evaluated for TMVR. All patients underwent TMVR following heart team judgement according to surgical high-risk (logistic EuroSCORE II > 10%).

All patients underwent clinical and echocardiographic examinations before and 5 years after the MitraClip procedure.

According to Mitral Valve Academic Research Consortium (MVARC) definitions, the primary endpoint was defined as all-cause mortality [11]. The secondary endpoint was an improvement in functional capacity: NYHA functional class at follow-up was < II; 25% amelioration in exercise capacity (six minute walk test [6MWT]).

The study was authorized by the local ethics committee and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed written, informed consent before study inclusion.

Echocardiography and follow-up assessment

Echocardiographic assessment before and after TMVR was done following current recommendations and guidelines which included a comprehensive echocardiography [4, 12]. The severity of MR was graded using the radius of proximal isovelocity surface area (PISA radius), effective regurgitant orifice area (EROA), as well as vena contracta (VC) width and regurgitant volume. EROA and regurgitation volume were calculated using the semi-quantitative PISA-method [13]. The echocardiographic studies were performed with a commercially available echocardiographic system (iE 33, Philips Medical Systems, Andover, Massachusetts) and echocardiography probes (X5-1, X7-2t) allowing acquisition of two- (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) data sets. sPAP was estimated from Doppler-based tricuspid regurgitation systolic peak velocity according to use of the modified Bernoulli equation (Delta-pressure: 4 × velocity) to approximate differences of pressure between the right ventricle and the right atrium.

The echocardiographer who performed follow-up evaluation was blinded to procedural outcomes and patient characteristics. Trained personnel carried out clinical follow-up evaluation, unattended by the interventionalists or procedural echocardiographer.

Interventional edge-to-edge repair of MR

Procedural details of TMVR with the MitraClip system have been described previously [14, 15]. During the MitraClip procedure, acute changes of MR severity were assessed by intraprocedural transesophageal echocardiography as supposed by Armstrong and Foster [16], and Wunderlich and Siegel [17]. Acute procedural success was defined as a reduction of MR by at least one grade having a residual MR < 2+. The number of clips required for procedural success was left to the discretion of the treating physician. Before the clip release, echocardiography was performed to exclude clinically relevant MV stenosis (mean MVG > 5 mmHg).

Statistical analysis

Normal distribution of continuous variables was examined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous data were expressed as mean values ± standard deviation. The Student two-sample t-test or the Mann-Whitney-U test was performed to compare continuous variables. The Fisher exact test or χ2 test was used to compare categorical data. Two-tailed p-values were considered to be significant if ranging below 0.05. Univariate analysis was performed to assess the impact of etiology of MR on clinical outcomes. The predictors of 5-year mortality were estimated employing the Cox proportional regression analysis. Survival and cumulative incidence of re-do in groups were compared using the Log-rank test and were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier curve. The regression and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis were performed to determine independent predictors with cut-off values of functional outcomes and mortality.

Statistics were performed using SPSS for Windows (PASW statistic, Version 20.0.0.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Baseline data and procedural outcomes

Two hundred sixty-five consecutive, surgical high-risk patients (81.4 ± 8.1 years, 46.7% female, Logistic EuroSCORE: 19.7 ± 6.7%, 60.5% sMR) underwent TMVR with the MitraClip system, and the majority of patients (88%, n = 233) completed a 5-year follow-up including physical, laboratory and echocardiographical examinations. Patients lost to follow-up (n = 32) were contacted concerning quality of life, complaints and hospitalization via telephone.

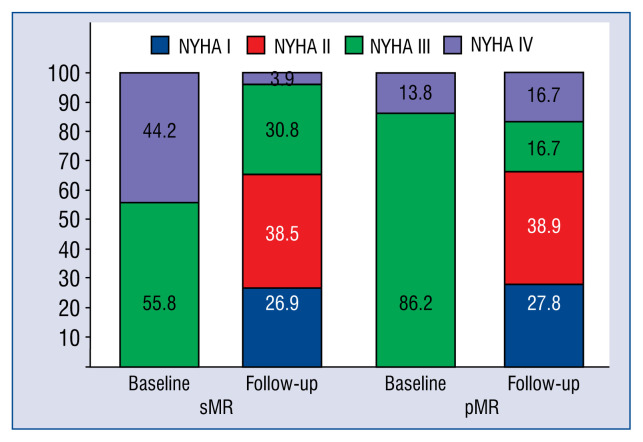

The baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. There were no differences between groups in demographic baseline characteristics. However, at baseline, patients with sMR presented worse functional capacity (6MWT: 253.3 ± 107.7 m vs. 267.1 ± 160.2 m; p = 0.2; NYHA > III: 44.2% vs. 13.8%; p = 0.06) compared to patients with pMR.

Table 1.

Baseline demographical characteristics.

| All patients (n = 265) | sMR (n = 160) | pMR (n = 105) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (female) | 46.7% | 40.9% | 56.7% | 0.1 |

| Age [years] | 81.4 ± 8.1 | 79.1 ± 8.7 | 84.6 ± 5.7 | 0.1 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 25.4 ± 4.2 | 26 ± 4.6 | 24.5 ± 3.4 | 0.1 |

| Logistic EuroScorE [%] | 19.7 ± 16.7 | 21.4 ± 17.5 | 16.9 ± 15.2 | 0.3 |

| NYHA ≥ II | 100% | 100% | 100% | 1 |

| NYHA III | 68.1% | 55.8% | 86.2% | |

| NYHA IV | 31.9% | 44.2% | 13.8% | 0.06 |

| chronic heart failure | 70.7% | 81.4% | 66.7% | 0.1 |

| coronary heart diesease | 71.4% | 75.9% | 65% | 0.3 |

| Arterial hypertension | 66.7% | 70.5% | 61.3% | 0.3 |

| History of stroke | 4% | 2.3% | 6.5% | 0.4 |

| Peripheral artery diesease | 10.7% | 11.4% | 9.7% | 0.6 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 34.7% | 45.5% | 29.4% | 0.09 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 36% | 45.5% | 31.6% | 0.1 |

| Nicotine | 24% | 25% | 22.6% | 0.5 |

| creatinine [mg/dL] | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 0.2 |

sMr — secondary mitral regurgitation; pMr — primary mitral regurgitation; BMI — body mass index; NYHA — New York Heart Association functional classification

The procedure was successfully performed in 242 (91.3%) patients with implantation of more than one clip in 32% of cases. Six MitraClip procedures were aborted due to relevant MV stenosis (MVG > 5 mmHg) after the clip closure. Four of those patients were treated for pMR. 13 procedures were aborted due to irreducible MR.

Of note, there was no procedural-related mortality, 10 (23.8%) patients had minor bleeding, and one patient had pericardial tamponade, which could be effectively treated with pericardiocentesis. All acute complications could be successfully managed before discharge. Overall, interventional failure rates were low, however, patients with pMR showed statistically significant higher interventional failure rates (pMR: 8.6%, sMR: 3.1%; p = 0.04).

During 5-year follow-up three patients underwent surgery for recurrent MR (pMR: 1.9%, sMR: 0.6%; p = 0.3), 16 patients required a second clipping (sMR: 6.8%, pMR: 4.7%, p = 0.5) and four patients were treated with additional catheter-based approaches (Carillon®, Cardiac Dimension, Kirkland, The USA; Cardioband®, Edwards Life-sciences, United Kingdom) due to recurrent severe MR and decompensated heart failure (sMR: 1.8%, pMR: 0.9%, p = 0.6) (Suppl. Fig. 4).

Echocardiographic measures at baseline and five-year follow-up

Concerning baseline echocardiographic characteristics, there were no significant differences in MR defining parameters and sPAP between sMR and pMR. Patients with sMR had larger baseline left ventricle (LV) volumes (LVEDV: 165.3 ± 62.6 mL, 135.8 ± 49.2 mL; p = 0.03; LVESV: 106.4 ± 53.3 mL, 59.3 ± 36.6 mL; p = 0.001) and significantly impaired baseline LV systolic function (38.3 ± 14.1%, 58.1 ± 15%; p = 0.0001). Patients with sMR showed impaired right ventricle (RV) function at baseline as well (TAPSE: 1.7 ± 0.4 cm, 2 ± 0.2 cm; p = 0.09) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline echocardiographical characteristics.

| All patients (n=265) | sMR (n = 160) | pMR (n = 105) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVEDV [mL] | 154.4 ± 59 | 165.3 ± 62.6 | 135.8 ± 49.2 | 0.03 |

| LVESV [mL] | 87.3 ± 52.4 | 106.4 ± 53.3 | 59.3 ± 36.6 | 0.0001 |

| LVEF [%] | 46.3 ± 17.4 | 38.3 ± 14.1 | 58.1 ± 15 | 0.0001 |

| sPAP [mmHg] | 47.5 ± 15 | 46.2 ± 15.7 | 50 ± 14 | 0.4 |

| MV gradient [mmHg] | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 1.8 ± 1 | 0.03 |

| Severity of Mr | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 0.1 |

| Mr grade III | 79.7% | 90.9% | 63.3% | 0.02 |

| Mr grade IV | 18.9% | 6.8% | 36.7% | 0.03 |

| E/A ratio | 2.4 ± 1 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 0.2 |

| PISA radius [cm] | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Vc width [cm] | 1.4 ± 4.4 | 1.5 ± 5.3 | 1.2 ± 2.3 | 0.7 |

| EroA [cm2] | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 0.3 |

| regurgitation volume [mL] | 54.4 ± 16 | 53.2 ± 16 | 56.3 ± 16.2 | 0.4 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 2 ± 0.8 | 0.6 |

| TAPSE [cm] | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 2 ± 0.2 | 0.09 |

sMr — secondary mitral regurgitation; pMr — primary mitral regurgitation; LVEDV — left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVESV — left ventricular end-systolic volume; LVEF — left ventricular ejection fraction; sPAP — systolic pulmonary artery pressure; MV — mitral valve: Mr — mitral regurgitation; PISA — proximal isovelocity surface area; Vc — vena contracta; EroA — effective regurgitant orifice area; TAPSE — tricuspid annular systolic excursion

At 5-year follow-up a sustained reduction of MR (MR ≤ 2) was found in 74% of patients (sMR: 77%, pMR: 71.5%; p = 0.9) (Fig. 1). There were no significant changes in LV volumes (LVEDVsMR: 162.4 ± 56.7 mL, 154.5 ± 66.9 mL; p = 0.5; LVEDVpMR: 127.8 ± 47.3 mL, 116.6 ± 26.4 mL; p = 0.3; LVES-VsMR: 105.2 ± 45.5 mL, 99.6 ± 57.8 mL; p = 0.6; LVESVpMR: 56.2 ± 34.5 mL, 51.6 ± 20.2 mL; p = 0.5). Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was not significantly changed 5 years after the MitraClip procedure (EFsMR 36.9 ± 12.6%, 38.7 ± 13.6%, p = 0.5; EFpMR 58.1 ± 12.2%, 58.4 ± 9.7%, p = 0.9). In sMR patients, sPAP was significantly reduced at follow-up (50 ± 17.4 mmHg, 39.3 ± 17.3 mmHg, p = 0.05), however, not significantly in pMR patients (49.4 ± 18.3 mmHg; 41.6 ± 18.7 mmHg, p = 0.3) (Table 3). RV function increased significantly just in patients with sMR (1.7 ± 0.4 cm, 1.9 ± 0.4 cm, p = 0.03; 2 ± 0.2 cm, 2.1 ± 0.4 cm, p = 0.5). MVG significantly increased after MitraClip procedures (1.4 ± 0.8 mmHg, 3.5 ± 2.9 mmHg; p = 0.001) without incidence of clinically relevant MV stenosis.

Figure 1.

Reduction of mitral regurgitation (MR) at 5-year follow-up; pMR — primary mitral regurgitation; sMR — secondary mitral regurgitation.

Table 3.

Echocardiographical and clinical outcomes at follow-up.

| Baseline | Follow-up | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEDV [mL] | 150 ± 55.5 | 140.9 ± 58.4 | 0.3 |

| sMr | 162.4 ± 56.7 | 154.5 ± 66.9 | 0.5 |

| pMr | 127.8 ± 47.3 | 116.5 ± 26.4 | 0.3 |

| LVESV [mL] | 87.6 ± 47.7 | 82.4 ± 52.8 | 0.4 |

| sMr | 105.2 ± 45.5 | 99.6 ± 57.8 | 0.6 |

| pMr | 56.2 ± 34.5 | 51.6 ± 20.2 | 0.5 |

| LVEF [%] | 44.5 ± 16.1 | 45.8 ± 15.5 | 0.5 |

| sMr | 36.9 ± 12.6 | 38.7 ± 13.6 | 0.5 |

| pMr | 58.1 ± 12.2 | 58.4 ± 9.7 | 0.9 |

| IVSDD [cm] | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 0.2 | 0.04 |

| sMr | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 0.2 | 0.04 |

| pMr | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Mr | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 0.0001 |

| sMr | 3 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 0.0001 |

| pMr | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 2 ± 0.4 | 0.0001 |

| Mr ≤ II [%] | 0 | 97.4 | 0.0001 |

| sMr | 0 | 100 | 0.0001 |

| pMr | 0 | 92.9 | 0.0001 |

| Mr > II [%] | 100 | 2.6 | 0.0001 |

| sMr | 100 | 0 | 0.0001 |

| pMr | 100 | 7.1 | 0.0001 |

| Mitral gradient [mmHg] | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 3.5 ± 2.9 | 0.0001 |

| sMr | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 2.8 ± 1.3 | 0.0001 |

| pMr | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 4.8 ± 4.5 | 0.02 |

| TAPSE [cm] | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 0.008 |

| sMr | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 0.03 |

| pMr | 2 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 0.5 |

| sPAP [mmHg] | 49.7 ± 17.3 | 40.7 ± 17.5 | 0.02 |

| sMr | 50 ± 17.4 | 39.3 ± 17.3 | 0.05 |

| pMr | 49.4 ± 18.3 | 41.6 ± 18.7 | 0.3 |

| NYHA functional class | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 0.0001 |

| sMr | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 0.0001 |

| pMr | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 1 | 0.004 |

| 6MWT [m] | 243.8 ± 121.3 | 298.1 ± 118.6 | 0.04 |

| sMr | 235.3 ± 107.7 | 305.3 ± 123.1 | 0.03 |

| pMr | 267.1 ± 160.2 | 278.6 ± 111.9 | 0.8 |

| NT-proBNP [pg/mL] | 5987.3 ± 9989.3 | 4614.7 ± 5596.6 | 0.5 |

| sMr | 3844.7 ± 3099.4 | 4581.1 ± 4356.1 | 0.2 |

| pMr | 10510.6 ± 16770.4 | 4685.8 ± 7939.8 | 0.4 |

sMr — secondary mitral regurgitation; pMr — primary mitral regurgitation; LVEDV — left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVESV — left ventricular end-systolic volume; LVEF — left ventricular ejection fraction; IVSDD — diastolic interventricular septum diameter; Mr — mitral regurgitation; TAPSE — tricuspid annular systolic excursion; sPAP — systolic pulmonary artery pressure; NYHA — New York Heart Association; 6MWT — six minutes walking test; NTpro-BNP — N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

Clinical outcomes and predictors of outcome

At 5-year follow-up the majority of patients (65.4%) presented with improved heart failure related symptoms (functional NYHA class ≤ II) and improved exercise tolerance (6MWT: 243.8 ± 121.3 m, 298.1 ± 118.6 m; p = 0.04). The functional capacity at follow-up did not differ between the groups (NYHA > II: sMR 34.6%, pMR 33.3%; p = 0.6). However, functional amelioration was more pronounced in sMR patients as assessed by functional NYHA class (sMR: 3.5 ± 0.5, 2.1 ± 0.9, p = 0.0001; pMR: 3.2 ± 0.4, 2.2 ± 1; p = 0.04) (Fig. 2) and 6MWT (sMR: 235.3 ± 107.7 m, 305.3 ±123.1 m; p = 0.03; pMR: 267.1 ± 160.2 m, 278.6 ± 111.9 m; p = 0.8). Decreased levels of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide were documented in both groups (sMR: 7635.3 ± 13639.8 pg/mL, 3943.4 ± 4190.5 pg/mL; p = 0.01; pMR: 7157.2 ± 10920 pg/mL, 4313.7 ± 7574.8 pg/mL; p = 0.02) (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Changes in functional New York Heart Association (NYHA) class; pMR — primary mitral regurgitation; sMR — secondary mitral regurgitation.

All-cause mortality was 16% at 5-year follow-up and was significantly higher in patients with sMR (sMR: 19%, pMR: 10%; p = 0.05) (Suppl. Table 1, Suppl. Fig. 3).

According to the ROC analysis baseline sPAP > 45 mmHg, baseline MVG > 1.5 mmHg and baseline level of creatinine > 2 mg/dL were found to be independent predictors for all-cause mortality at 5-year follow-up. Furthermore, baseline level of creatinine (cut-off value: 1.33 mg/dL; HR: 0.695), baseline sPAP (cut-off value: 50 mmHg; HR: 0.96) and baseline MVG (cut-off value: 1.4 mmHg; HR: 0.82) were used as independent predictors for poor functional outcomes at 5-year follow-up (Suppl. Figs. 1, 2).

Discussion

The main findings of the present study are as follows: (1) Acute procedural failure was higher in pMR patients. (2) A majority of patients (74%) showed sustained MR reduction, increased RV function and reduced sPAP at 5-year follow-up. (3) Despite pronounced clinical and echocardiographic amelioration at follow-up and lower interventional failure rates, all-cause 5-year mortality was significantly higher in sMR patients. Baseline levels of creatinine > 2 mg/dL, MVG > 1.5 mmHg and sPAP > 50 mmHg were independent predictors of the 5-year mortality and poor functional outcomes.

Survival and re-intervention rates

Mortality after TMVR with the MitraClip device has been evaluated previously in different studies. Toggweiler et al. [18] found in 75 patients, a patient mortality of 4% at 30 days, 9% at 1 year and 25% (sMR 28%, pMR 18%) at 2 years after the MitraClip procedure. Comparable data were presented in 304 patients by Capodanno et al. [19] (4% at 30 days, 11% at 1-year, and 19% at 2-years). The EVEREST II study found a 20% 5-year mortality without statistical difference between MR etiologies [20].

In line with those studies, sustained MR reduction was found with improved functional capacity and quality of life 5 years after the MitraClip procedure. Although patients in the present study were considerably older (mean age: 81 years), they had more often sMR and in higher baseline NYHA functional classes, long-term mortality rates (16%) were comparable to the cited studies. In contrast to EVEREST II, higher mortality in patients with sMR was found despite noticeable improvement of functional capacity at follow-up. Of note, in the early EVEREST studies, echocardiographic feasibility criterias were far more restrictive, and the majority of patients were treated for pMR, which might account for different acute and long-term procedural success rates.

Higher all-cause mortality at follow-up in sMR patients was found, and might be explained by the advanced age of sMR patients, a more impaired baseline LV and RV function compared to pMR patients. Similar findings were presented in the COAPT (Cardiovascular Assessment of the MitraClip Percutaneous Therapy for Heart Failure Patients with Functional Mitral Regurgitation) trial. In this trial, Stone et al. [21] found 29.1% 2-year mortality in 302 patients with sMR despite being younger patients, was relevantly higher than the present collective. This might be explained through the present findings “predictors of mortality” such as impaired baseline renal function (creatinine clearance < 51 mL/min), advanced systolic heart failure (LVEF 31%), and elevated RV systolic pressure (> 44 mmHg).

Buzzatti et al. [22] showed higher 5-year mortality (about 50%) with good mid-term results including reduction of MR and improved symptoms in 339 patients with relevant MR. In line with current results, they found pronouncedly worse outcomes and higher mortality in patients with secondary MR associated with worse LV remodelling and function.

Predictors of adverse outcome

Azzalini et al. [23] showed that an impaired LV function was associated with increased mortality in 77 patients with sMR 1 year after the MitraClip procedure. This finding is in line with the present data. A higher 5-year mortality in sMR patients with reduced baseline LV function was found (EF < 40%) compared to pMR patients with a baseline LVEF > 55%.

Another independent marker for secondary endpoint was the baseline level of creatinine (> 2 mg/dL) in the current study. This finding is supported by a study from Ohno et al. [24]. They found a significant adverse effect of concomitant chronic kidney disease on MR reduction, functional capacity (NYHA functional class), survival and frequency of re-repair in 214 patients with severe MR one year after the MitraClip procedure.

Toggweiler et al. [18] (baseline MVG > 3 mmHg) and Neuss et al. [9] (post-procedural MVG > 5 mmHg) showed a devastating impact of higher MVG on clinical outcomes and procedural success. In concordance with those results, baseline MVG (> 1.5 mmHg) as an independent predictor for both primary and secondary endpoints at 5-year follow-up was found in the present study.

Moreover, Matsumoto et al. [10] found that pre-existing pulmonary hypertension was a strong predictor of higher all-cause mortality 12 months after the MitraClip procedure. The association between worse outcomes and advanced heart disease and symptoms have been presented by Buzzatti et al. [22] in more than 300 patients with relevant MR at 5-year follow-up. The cited study validates present findings; elevated baseline sPAP values are an independent predictor of (> 45 mmHg) adverse outcomes and (> 50 mmHg) all-cause mortality at 5-year follow-up.

Limitations of the study

This single-center retrospective study has several limitations. Data was reported from a single-center experience, and all echocardiographic analyses were not verified by an independent core lab. Furthermore, the 5-year follow-up was sufficiently completed in 233 (88%) patients. Because of this, the present results should be proven in multi-center studies with a larger patient collective.

Conclusions

Transcatheter mitral valve repair with the MitraClip procedure was found to be safe, lead to sustained MR reduction, and increase RV function during 5 years subsequent to the procedure. Despite pronounced functional and echocardiographical amelioration and lower procedural failure, sMR patients showed a higher all-cause mortality at 5-year follow-up compared to patients with pMR. Elevated baseline creatinine, baseline levels of MVG and baseline sPAP were associated with poor functional outcome and high all-cause mortality 5-year after MitraClip.

Supplementary Information

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

References

- 1.Baldus S, Schillinger W, Franzen O, et al. MitraClip therapy in daily clinical practice: initial results from the German transcatheter mitral valve interventions (TRAMI) registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(9):1050–1055. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franzen O, van der Heyden J, Baldus S, et al. MitraClip® therapy in patients with end-stage systolic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13(5):569–576. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garatti A, Castelvecchio S, Bandera F, et al. Mitraclip procedure as a bridge therapy in a patient with heart failure listed for heart transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99(5):1796–1799. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.07.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silvestry FE, Rodriguez LL, Herrmann HC, et al. Echocardiographic guidance and assessment of percutaneous repair for mitral regurgitation with the Evalve MitraClip: lessons learned from EVEREST I. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2007;20(10):1131–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman T, Kar S, Rinaldi M, et al. Percutaneous mitral repair with the MitraClip system: safety and midterm durability in the initial EVEREST (Endovascular Valve Edge-to-Edge REpair Study) cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(8):686–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.077. www.cardiologyjournal.org . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mauri L, Garg P, Massaro JM, et al. The EVEREST II Trial: design and rationale for a randomized study of the evalve mitraclip system compared with mitral valve surgery for mitral regurgitation. Am Heart J. 2010;160(1):23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mauri L, Foster E, Glower DD, et al. 4-year results of a randomized controlled trial of percutaneous repair versus surgery for mitral regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(4):317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puls M, Lubos E, Boekstegers P, et al. One-year outcomes and predictors of mortality after MitraClip therapy in contemporary clinical practice: results from the German transcatheter mitral valve interventions registry. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(8):703–712. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuss M, Schau T, Isotani A, et al. Elevated mitral valve pressure gradient after mitraclip implantation deteriorates long-term outcome in patients with severe mitral regurgitation and severe heart failure. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(9):931–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.12.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsumoto T, Nakamura M, Yeow WL, et al. Impact of pulmonary hypertension on outcomes in patients with functional mitral regurgitation undergoing percutaneous edge-to-edge repair. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114(11):1735–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone GW, Adams DH, Abraham WT, et al. Clinical Trial Design Principles and Endpoint Definitions for Transcatheter Mitral Valve Repair and Replacement: Part 1: Clinical Trial Design Principles: A Consensus Document From the Mitral Valve Academic Research Consortium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(3):278–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zoghbi WA, Enriquez-Sarano M, Foster E, et al. Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003;16(7):777–802. doi: 10.1016/S0894-7317(03)00335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashikhmina E, Shook D, Cobey F, et al. Three-dimensional versus two-dimensional echocardiographic assessment of functional mitral regurgitation proximal isovelocity surface area. Anesth Analg. 2015;120(3):534–542. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherif MA, Paranskaya L, Yuecel S, et al. MitraClip step by step; how to simplify the procedure. Neth Heart J. 2017;25(2):125–130. doi: 10.1007/s12471-016-0930-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thornton T, McDermott L. MitraClip® system design and history of development. Percutaneous Mitral Leaflet Repair. 2013:36–44. doi: 10.3109/9781841849669-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armstrong EJ, Foster E. Echocardiographic evaluation for mitral regurgitation grading and patient selection. Percutaneous Mitral Leaflet Repair: MitraClip Therapy for Mitral Regurgitation, vol. 17. First Informa Healthcare. 2012:73–79. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wunderlich NC, Siegel RJ. Peri-interventional echo assessment for the MitraClip procedure. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14(10):935–949. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toggweiler S, Zuber M, Sürder D, et al. Two-year outcomes after percutaneous mitral valve repair with the MitraClip system: durability of the procedure and predictors of outcome. Open Heart. 2014;1(1):e000056. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capodanno D, Adamo M, Barbanti M, et al. Predictors of clinical outcomes after edge-to-edge percutaneous mitral valve repair. Am Heart J. 2015;170(1):187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldman T, Kar S, Elmariah S, et al. Randomized comparison of percutaneous repair and surgery for mitral regurgitation: 5-year results of EVEREST II. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(25):2844–2854. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stone G, Lindenfeld J, Abraham W, et al. Transcatheter mitral-valve repair in patients with heart failure. New Engl J Med. 2018;379(24):2307–2318. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1806640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buzzatti N, Denti P, Scarfò IS, et al. Mid-term outcomes (up to 5 years) of percutaneous edge-to-edge mitral repair in the real-world according to regurgitation mechanism: A single-center experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018 doi: 10.1002/ccd.28029. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azzalini L, Millán X, Khan R, et al. Impact of left ventricular function on clinical outcomes of functional mitral regurgitation patients undergoing transcatheter mitral valve repair. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;88(7):1124–1133. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohno Y, Attizzani GF, Capodanno D, et al. Impact of chronic kidney disease on outcomes after percutaneous mitral valve repair with the MitraClip system: insights from the GRASP registry. EuroIntervention. 2016;11(14):e1649–e1657. doi: 10.4244/EIJV11I14A316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.