Abstract

Background

The study aimed to uncover the regulation mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) and provide novel prognostic biomarkers.

Methods

The dataset GSE62203 downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database was utilized in the present study. After pretreatment using the Affy package, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by the limma package, followed by functional enrichment analysis and protein–protein interaction (PPI) network analysis. Furthermore, module analysis was conducted using MCODE plug-in of Cytoscape, and functional enrichment analysis was also performed for genes in the modules.

Results

A set of 560 DEGs were screened, mainly enriched in the metabolic process and cell cycle related process. Hub nodes in the PPI network were LDHA (lactate dehydrogenase A), ALDOC (aldolase C, fructose-bisphosphate) and ABCE1 (ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily E Member 1), which were also highlighted in Module 1 or Module 2 and predominantly enriched in the processes of glycolysis and ribosome biogenesis. Additionally, LDHA were linked with ALDOC in the PPI network. Besides, activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) was prominent in Module 3; while myosin heavy chain 6 (MYH6) was highlighted in Module 4 and was mainly involved in muscle cells related biological processes.

Conclusions

Five potential biomarkers including LDHA, ALDOC, ABCE1, ATF4 and MYH6 were identified for DCM prognosis.

Keywords: diabetic cardiomyopathy, expression profile, differential analysis, module analysis, glycolysis, ribosome biogenesis

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) remains a life-threatening disease worldwide with increasing incidence [1, 2]. The predominant cause of death for T2DM patients was cardiovascular disease [3]. The diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) has been recognized as ventricular dysfunction in the absence of hypertension and coronary artery disease, may increase the risk of developing heart failure [4]. Moreover, DCM has been defined as a primary disease progressing into a metabolic disturbance that was mainly due to the elevation of free fatty acid (FFA) and the alteration of glucose metabolism, and would change the myocardial structure and function [5, 6]. It was reported that the mortality of patients with DCM was 42%, and the ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-STEMI mortality in diabetic patients were 72% and 67%, respectively [7]. Currently, there were no specific therapeutic interventions for this predominant complication, except a paucity of proposed drugs such as eplerenone [8]. The understanding of mechanisms on DCM progression would facilitate finding novel targets for treatment of this disease. Several mechanisms in charge of DCM were proposed. For instance, it was confirmed that FFA-mediated apoptosis, hypertrophy, and contractile dysfunction were the causative factors for DCM [6]. Oxidative stress was another major cause for the pathogenesis of DCM [9]. The overexpression of insulin like growth factor 1 was reported to act as an inhibitor in DCM development [10]. A more recent study elaborated molecular mechanisms that contributed to functional alterations in the diabetic heart and consequently identified several crucial advanced glycation end products (AGEs), fibrosis related genes including poly (ADP-Ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1), Otsuka Long Evans Tokushima fatty (OLETF) and matrix metalloproteinases 2 (MMP-2), inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and transforming growth factor beta1 (TGF-β1) and altered pathways like mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK signaling) and TGF-β signaling, as well as critical miRNAs (miR-143, miR-181, miR-103, miR-107 and miR-802) [11]. However, previous informative findings only partially elucidated the molecular mechanism involved in DCM, and future study for comprehensive illustrating the primary genes and the pathways for the prevention of DCM was needed.

So far, the patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) model has been applied to mimic the DCM condition and dilated cardiomyopathy, to investigate therapeutic strategies or epigenetic regulations in these diseases [12–14]. Among them, Drawnel et al. [13] used a patient-specific induced iPSC model to exhibit metabolic disorders during the progression of DCM and finally screened several remarkable molecular drugs such as W7 (calmodulin), penitrem A (sodium and potassium channel blocker) and MCBQ (PDE5 inhibitors) for the prevention of DCM. Although several gene alterations such as the elevated MYL2, MYL4 and PLN; and the decreased NPPA, NPPB and ACTA1 were validated, the interactions among them and their functions were not interpreted, and thus lacked evidence for the prediction of potent therapeutic targets. Therefore, the expression profile GSE62203 deposited by Drawnel et al. [13] was re-analyzed to identify critical genes by extensive bioinformatical methods including differential analysis, protein–protein interaction (PPI) network and module analysis. Based on the above analyses, the aim herein was to uncover the interrelated regulation mechanisms of DCM and provide novel biomarkers for detection and prevention of DCM.

Methods

Gene expression data

A data set of the gene expression profile GSE62203 containing 4 treated samples (human iPS-derived CMs exposed to glucose, endothelin-1 and cortisol for 2 days in vitro) and 4 untreated samples (vehicle-control treated) was utilized in this study, which was deposited by Drawnel et al. [13] in the public Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) database. In the Drawnel study, CMs were derived from CDI-MRB iPSCs (cellular dynamics international [CDI]). After being cultured for 2 days with conditions of 37°C and 7% CO2, the plating medium for the CMs was changed for maturation medium (MM) for 3 days. After 3 days, the MM was exchanged for DM (MM+ glucose, endothelin and cortisol) for treated samples or MM+ vehicle control for untreated samples for another 2 days. Thus, the DCM condition was established. The platform for the expression profile was Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, California, USA).

Data preprocessing and differential analysis

The Affy package in Bioconductor (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/affy.html) [15] was employed to perform the pretreatment. The raw data were subjected to background correction, quantile data normalization and probe summarization recruiting the robust multi-array average (RMA) algorithm [16]. After obtaining the gene expression matrix, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the 2 kinds of samples were selected based on a t-test using linear models for microarray data (limma, http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html) package of Bioconductor R [17]. The cut-off values for the DEGs identification were p < 0.05 and |log2 fold change| > 0.5.

Functional enrichment analysis for the DEGs

To explore the altered biological process (BP) and pathways, the DEGs were mapped into gene ontology ([GO], http://www.geneontology.org/) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes ([KEGG], http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html) databases, using Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integration Discovery ([DAVID], http://david.abcc.Ncifcrf.gov/) online tool [18] with the Modified Fisher Exact test [19]. The p-value < 0.05 and the count (number of the genes) > 2 were set as the threshold for significant BP terms and pathways.

Construction of PPI network

To further explore potential correlations from the protein level, which facilitated to illustrate the underlying molecular mechanisms, identified DEGs were mapped into the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins ([STRING], http://string-db.org/) database [20]. The PPI network of protein products of the genes was established, containing pairwise interactions with required confidence (combined score) > 0.4. A protein in the network was considered as a ‘node’ and the ‘degree’ of a node referred to the interaction pair numbers of a protein. The degree was calculated for each node using connectivity degree analysis. The ‘hub’ node in the network was deemed as the node with high degrees.

Module analysis of the PPI network

Functional modules of the network was extracted using the MCODE [21] plug-in of Cytoscape software with default parameters (Degree Cutoff: 2, Node Score Cutoff: 0.2, K-Core: 2, Max. Depth: 100) for selection. Subsequently, high scored modules with substantial nodes were further screened out for enrichment analysis, as described above.

Results

DEGs between treated and untreated samples

Based on the aforementioned criteria, a cohort of 560 DEGs was identified between the treated and untreated samples, consisting of 264 up-regulated genes and 296 down-regulated genes (Supplementary material 1).

BPs and pathways altered in the treated sample

After GO and KEGG enrichment analysis, the up-regulated DEGs were mainly enriched in metabolic BP terms such as generation of precursor metabolites and energy (GO: 0006091), hexose metabolic process (GO: 0019318), monosaccharide metabolic process (GO: 0005996) and glucose metabolic process (GO: 0006006); and besides response to wounding (GO: 0009611); response to organic substance (GO: 0010033), regulation of cell proliferation (GO: 0042127); while the down-regulated DEGs were significantly enriched in the processes including positive regulation of macromolecule metabolic process (GO: 0010604), cellular response to stress (GO: 0033554), and the cell control related functions such as regulation of apoptosis (GO: 0042981), regulation of programmed cell death (GO:0043067), regulation of cell death (GO:0010941), cell cycle (GO:0007049) and positive regulation of cellular biosynthetic process (GO:0031328) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Biological processes significantly affected by the DEGs in treated samples. (Top ten, ranked by gene numbers enriched in a specific process).

| Category | Term | Description | Count | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated DEGs | ||||

| BP | GO:0006091 | Generation of precursor metabolites and energy | 28 | 1.37E-13 |

| BP | GO:0055114 | Oxidation reduction | 25 | 2.72E-05 |

| BP | GO:0009611 | Response to wounding | 24 | 3.98E-06 |

| BP | GO:0010033 | Response to organic substance | 23 | 1.07E-03 |

| BP | GO:0019318 | Hexose metabolic process | 22 | 8.75E-13 |

| BP | GO:0005996 | Monosaccharide metabolic process | 22 | 1.47E-11 |

| BP | GO:0042592 | Homeostatic process | 22 | 3.95E-03 |

| BP | GO:0006006 | Glucose metabolic process | 21 | 1.05E-13 |

| BP | GO:0042127 | Regulation of cell proliferation | 19 | 4.54E-02 |

| BP | GO:0044057 | Regulation of system process | 16 | 5.92E-05 |

| Down-regulated DEGs | ||||

| BP | GO:0010604 | Positive regulation of macromolecule metabolic process | 22 | 1.20E-02 |

| BP | GO:0033554 | Cellular response to stress | 21 | 1.97E-04 |

| BP | GO:0042981 | Regulation of apoptosis | 20 | 2.32E-02 |

| BP | GO:0043067 | Regulation of programmed cell death | 20 | 2.54E-02 |

| BP | GO:0010941 | Regulation of cell death | 20 | 2.62E-02 |

| BP | GO:0009891 | Positive regulation of biosynthetic process | 19 | 1.17E-02 |

| BP | GO:0007049 | Cell cycle | 19 | 3.14E-02 |

| BP | GO:0006412 | Translation | 18 | 6.09E-06 |

| BP | GO:0006396 | RNA processing | 18 | 2.41E-03 |

| BP | GO:0031328 | Positive regulation of cellular biosynthetic process | 18 | 2.05E-02 |

DEG — differentially expressed genes; BP — biological process; GO — gene oncology; Count — gene numbers enriched in a specific BP term.

The over-represented pathways for the up-regulated DEGs were glycometabolism and proteometabolism related pathways including glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (hsa00010), fructose and mannose metabolism (hsa00051), pentose phosphate pathway (hsa00030), starch and sucrose metabolism (hsa00500), arginine and proline metabolism (hsa00330), cysteine and methionine metabolism (hsa00270); by contrast, the prominent ones for down-regulated DEGs were aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis (hsa00970) and arginine, and proline metabolism (hsa00330) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pathways significantly altered by the DEGs in treated samples.

| Category | Term | Description | Count | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated DEGs | ||||

| KEGG | hsa00010 | Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis | 15 | 3.66E-12 |

| KEGG | hsa00051 | Fructose and mannose metabolism | 6 | 4.49E-04 |

| KEGG | hsa00330 | Arginine and proline metabolism | 7 | 5.12E-04 |

| KEGG | hsa00500 | Starch and sucrose metabolism | 6 | 1.21E-03 |

| KEGG | hsa00030 | Pentose phosphate pathway | 5 | 1.25E-03 |

| KEGG | hsa04810 | Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | 12 | 2.84E-03 |

| KEGG | hsa04510 | Focal adhesion | 10 | 1.57E-02 |

| KEGG | hsa00270 | Cysteine and methionine metabolism | 4 | 2.77E-02 |

| KEGG | hsa05012 | Parkinson’s disease | 7 | 3.78E-02 |

| KEGG | hsa04610 | Complement and coagulation cascades | 5 | 4.46E-02 |

| KEGG | hsa05211 | Renal cell carcinoma | 5 | 4.67E-02 |

| Down-regulated DEGs | ||||

| KEGG | hsa00970 | Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis | 7 | 2.92E-05 |

| KEGG | hsa00330 | Arginine and proline metabolism | 4 | 4.56E-02 |

DEG — differentially expressed genes; KEGG — Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; Count — gene numbers enriched in a specific biological process term

The PPI network of the DEGs

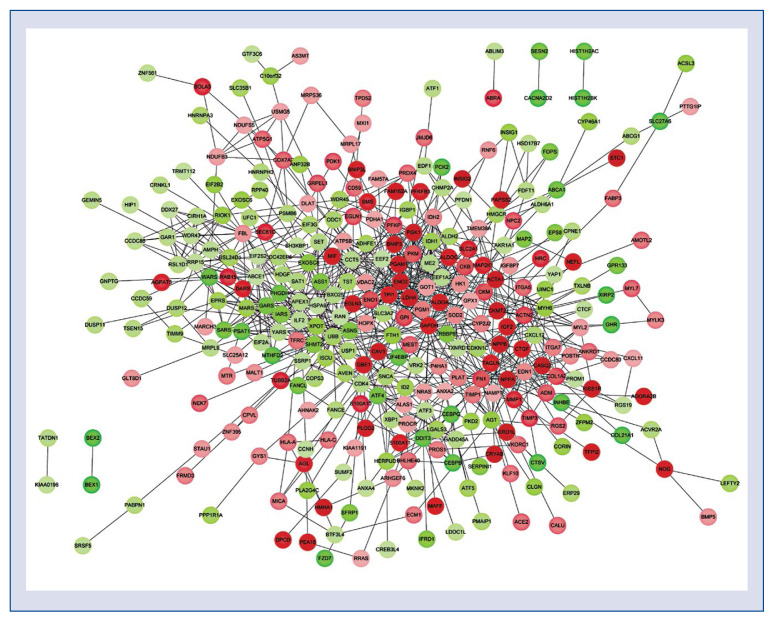

By mapping the DEGs into the STRING database, a PPI network was established, comprising of 317 nodes and 929 interactions. As revealed in Figure 1, the remarkable nodes with high degree (> 20) were GAPDH (degree = 49), FN1 (degree = = 30), LDHA (degree = 28), ENO1 (degree= 27), PGK1 (degree = 26), ABCE1 (degree = 25), SOD2 (degree = 23), PKM (degree = 23), GOT1 (degree = 22), HK1 (degree = 22), TPI1 (degree = 21), GPI (degree = 21) and ALDOA (degree = 21).

Figure 1.

Protein–protein interaction network of differentially expressed genes in iPS-derived cardiomyocytes treated by glucose, endothelin-1 and cortisol. Circles represent protein products of differentially expressed genes, and red denotes up-regulated, green denotes down-regulated; color depth indicates the significance of differential expressed genes.

Functional module network and the enrichment analysis for genes in the modules

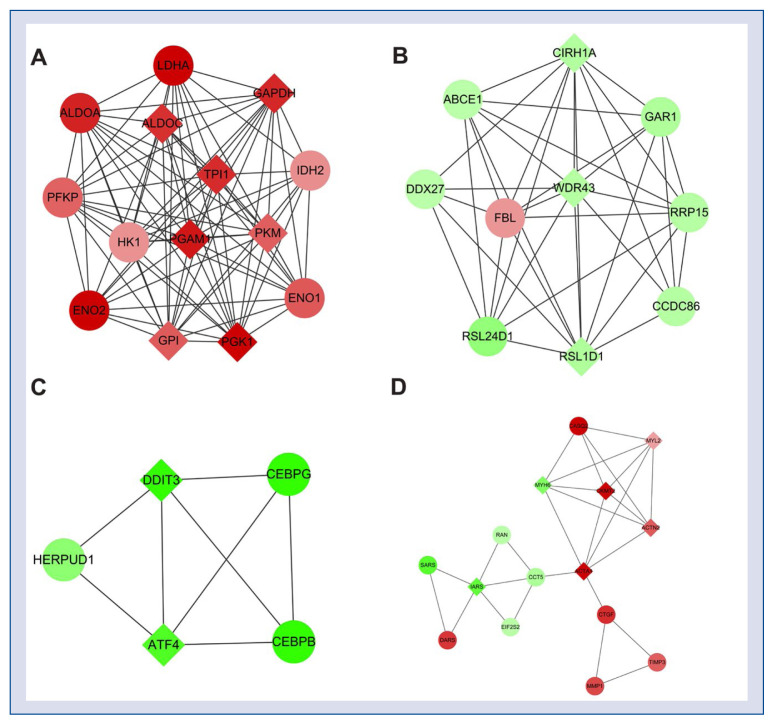

According to module analysis of the PPI network, four modules with a high score (> 3) were extracted from the PPI network. There were 14 up-regulated nodes such as ALDOC, LDHA, PGK1 and TPI1 in Module 1 with a final score of 12.923; and 10 nodes including ABCE1, GAR1 and FBL in Module 2 with a final score of 8.222. The Module 3 contained five down-regulated nodes as DDIF3, ATF4, CEBPG, CEBPB and HERPUD1 and achieved a score of 4, while Module 4 consisted of 15 nodes such as CASQ2, CKMT2, IARS, CCT5, ACTA1, CKMT2 and MYH6 and had a score of 3.857 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Modules of the protein–protein interaction network. A. Module 1; B. Module 2; C. Module 3; D. Module 4. Circles represent protein products of differentially expressed genes, and red denotes up-regulated genes, green denotes down-regulated genes, as well as diamonds stand for hub nodes; color depth indicates the significance of differentially expressed genes.

The BP functions of the genes (which encode proteins in the modules) in the four modules were further analyzed. As presented in Table 3, the over-represented BPs for genes in Module 1 were predominantly correlated with the catabolic process of various carbohydrates such as glycolysis (GO:0006096), glucose catabolic process (GO:0006007), monosaccharide catabolic process (GO:0046365) and alcohol catabolic process (GO:0046164); while that for genes in Module 2 were mainly related to ribosome biogenesis and processing functions including ribosome biogenesis (GO:0042254), RNA processing (GO:0006396) and rRNA metabolic process (GO:0016072). Genes in the Module 3 were significantly correlated with the metabolic process involved in the cellular biosynthesis such as positive regulation of nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolic process (GO:0045935), positive regulation of nitrogen compound metabolic process (GO:0051173), positive regulation of cellular biosynthetic process (GO:0031328); and besides the cell control related BPs including regulation of apoptosis (GO:0042981) and regulation of programmed cell death (GO:0043067); whereas the prominent BPs for the genes in the Module 4 were involved in the processes relating to muscle cells such as muscle contraction (GO:0006936), muscle system process (GO:0003012) and muscle cell development (GO:0055001).

Table 3.

Significantly enriched processes of genes in the module network.

| Category | Term | Description | Count | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Module 1 | ||||

| BP | GO:0006096 | Glycolysis | 13 | 8.68E-30 |

| BP | GO:0006007 | Glucose catabolic process | 13 | 1.48E-28 |

| BP | GO:0019320 | Hexose catabolic process | 13 | 1.46E-27 |

| BP | GO:0046365 | Monosaccharide catabolic process | 13 | 2.12E-27 |

| BP | GO:0046164 | Alcohol catabolic process | 13 | 1.17E-26 |

| BP | GO:0044275 | Cellular carbohydrate catabolic process | 13 | 2.18E-26 |

| BP | GO:0016052 | Carbohydrate catabolic process | 13 | 5.18E-25 |

| BP | GO:0006006 | Glucose metabolic process | 13 | 3.64E-23 |

| BP | GO:0006091 | Generation of precursor metabolites and energy | 14 | 4.25E-22 |

| BP | GO:0019318 | Hexose metabolic process | 13 | 6.06E-22 |

| Module 2 | ||||

| BP | GO:0042254 | Ribosome biogenesis | 3 | 4.78E-04 |

| BP | GO:0022613 | Ribonucleoprotein complex biogenesis | 3 | 1.04E-03 |

| BP | GO:0006396 | RNA processing | 3 | 9.27E-03 |

| BP | GO:0006364 | rRNA processing | 2 | 2.69E-02 |

| BP | GO:0016072 | rRNA metabolic process | 2 | 2.81E-02 |

| Module 3 | ||||

| BP | GO:0034976 | Response to endoplasmic reticulum stress | 3 | 3.67E-05 |

| BP | GO:0045935 | Positive regulation of nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolic process | 4 | 3.77E-04 |

| BP | GO:0051173 | Positive regulation of nitrogen compound metabolic process | 4 | 4.14E-04 |

| BP | GO:0010557 | Positive regulation of macromolecule biosynthetic process | 4 | 4.34E-04 |

| BP | GO:0031328 | Positive regulation of cellular biosynthetic process | 4 | 4.98E-04 |

| BP | GO:0009891 | Positive regulation of biosynthetic process | 4 | 5.19E-04 |

| BP | GO:0042981 | Regulation of apoptosis | 4 | 8.00E-04 |

| BP | GO:0043067 | Regulation of programmed cell death | 4 | 8.23E-04 |

| BP | GO:0010941 | Regulation of cell death | 4 | 8.32E-04 |

| BP | GO:0010604 | Positive regulation of macromolecule metabolic process | 4 | 9.66E-04 |

| Module 4 | ||||

| BP | GO:0006936 | Muscle contraction | 5 | 1.44E-05 |

| BP | GO:0003012 | Muscle system process | 5 | 2.08E-05 |

| BP | GO:0030239 | Myofibril assembly | 3 | 2.07E-04 |

| BP | GO:0031032 | Actomyosin structure organization | 3 | 3.70E-04 |

| BP | GO:0010927 | Cellular component assembly involved in morphogenesis | 3 | 6.14E-04 |

| BP | GO:0006418 | tRNA aminoacylation for protein translation | 3 | 1.00E-03 |

| BP | GO:0043039 | tRNA aminoacylation | 3 | 1.00E-03 |

| BP | GO:0043038 | Amino acid activation | 3 | 1.00E-03 |

| BP | GO:0055002 | Striated muscle cell development | 3 | 1.28E-03 |

| BP | GO:0055001 | Muscle cell development | 3 | 1.48E-03 |

BP — biological process; GO — gene oncology; Count — gene numbers enriched in a specific BP term

Discussion

The DCM is defined as ventricular dysfunction that occurs in diabetic patients [22] and the iPSC model was applied to detect the metabolic alterations and screen potential genes and molecular drugs [13, 23]. In the present study, the expression profile GSE62203 was utilized to conduct a series of bioinformatic analyses and as a result, identify a cohort of 560 DEGs between treated and untreated samples. The hub nodes in the PPI network were LDHA, ALDOC and ABCE1, which were also highlighted in Module 1 or Module 2 and predominantly enriched in the glycolysis and ribosome biogenesis. Besides, ATF4 was prominent in Module 3; while MYH6 was highlighted in Module 4 which was mainly involved in muscle cells related BPs.

The LDHA (lactate dehydrogenase A) is one of the subunits of LDH which play significant roles in the final step of anaerobic glycolysis by interconversion of pyruvate and lactate using NADH/NAD+ as a co-substrate to allow continuous energy production [24]. It was reported that overexpression of LDHA activity may influence normal glucose metabolism and insulin secretion in the islet beta-cell type, and also result in insulin secretory defects in some forms of T2DM [25, 26]. In addition, the overexpression of LDHA activity might increase the lactate level and lactate–pyruvate interconversion rates in diabetes patients [27]. Similarly, the increased level of LDH was observed in the diabetic group, while luteolin exerted a protective effect against DCM by reducing the content of LDH in serum [28]. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1, was a crucial transcription factor in brain ischemic pre-conditioning [29] and the expression of HIF-1α was decreased by a diabetic environment [30]. Partial deficiency of HIF-1α was proposed to increase the risk of DCM, and interestingly, LDHA was one of the target genes of HIF-1 that is involved in glucose metabolism and was upregulated in the HIF-1α heterozygous-null mutants [31]. In the present study, LDHA was the striking node in both PPI network and Module 1, and significantly enriched in glycolysis, giving potent evidence that LDHA might emerge as a central regulator in the progression of DCM via disturbing the glycolysis process.

ALDOC (aldolase C, fructose-bisphosphate) encodes a member of the class I fructose-biphosphate aldolase family gene, which acts as a catalyst that catalyzes the reversible aldol cleavage of fructose-1,6-biphosphate and fructose 1-phosphate to dihydroxyacetone phosphate and either glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate or glyceraldehyde, respectively in the glycolysis process [32]. Increased glucose was one hallmark of diabetes mellitus (DM) and ALDOC was one of the enzymes that promoted glycolysis and was induced by the elevated glucose [33]. Then, the up-regulated ALDOC was a positive correlation with the increase of FFA in plasma which might impair insulin secretion to develop T2DM [34, 35]. Additionally, ALDOC was up-regulated in the heart tissue in a rodent model of myocardial I/R injury [36]. Though no direct evidence existed that ALDOC and LDHA were interplayed with regard to diabetes or cardiomyopathy, it was indicated that ALDOC and LDHA were both up-regulated in a cervical cancer cell line of paclitaxel-resistant HeLa sublines [37]. On the other hand, DM was tightly related to the risk of various cancers including cervical cancer [38]. Notably, ALDOC and LDHA were both linked to HIF-1, which was associated with the risk of DCM as mentioned above [31]. These findings collectively suggested that the interacted ALDOC and LDHA might be involved in the regulation of the glycolysis process during DCM progression, as predicted by the current module analysis and enrichment analysis. However, more validations are needed to confirm the regulatory relationship between the two genes.

The ABCE1 encoded ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily E Member 1 which belongs to a family member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters and is primarily known as RNase L inhibitor (RLI) [39]. Zeng et al. [40] had indicated that RNase L activation was responsible for type I diabetes, and it was also suggested that the increased expression of RNase L or down-regulated of its inhibitor (RLI) might enhance the insulin response in muscle cells of obese people [41]. Additionally, further studies demonstrated that the mutation of ABCB and gene polymorphisms of ABCG8 and ABCG5 have been linked to T2DM [42, 43]. Moreover, ABC transporters are energy-dependent when transporting various molecules across the biological membranes, while HF is the consequence of insufficient energy supplement of the cardiac pump. Therefore, it was hypothesized that the expression alterations of ABC transporters occurred during human HF [44, 45]. Due to ABCE1 is a member of ABC transporters, and the present results indicated that the ABCE1 was a prominent down-regulated node in Module 2. Thus, it was predicted that the defective ABCE1 might have a significant influence on the progression of DCM. However, there is no direct evidence to prove that ABCE1 had interplayed with DCM, and it still needs further validation to confirm the relationship between the ABCE1 and DCM.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a cell system consisting of the lipid synthesis, calcium homeostasis, protein folding, and maturation. The ER stress has been reported in the development of DCM [47, 48]. Moreover, it has been confirmed that ER-triggered apoptosis would contribute to the pathology of DCM [49]. Activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) is a DNA binding protein. The glucagon-like peptide-1 analog liraglutide (LIRA) was confirmed to protect against DCM by inactivating the ER stress pathway, meanwhile the expression of ATF4 was decreased with the treatment of LIRA [50], implying that ATF4 might play significant roles in the progression of DCM, as predicted in the present result that ATF4 was a prominent node in Module 3.

The cardiac muscle myosin MYH6 was decreased in type 2 Zucker diabetic fatty rats [51]. Strikingly, MYH6 was diminished under the hypertrophic stress (DM-treated with CMs) [13] and was considered a cardiac marker by fluorescent immunostaining [52]. The current results indicated that MYH6 was highlighted in Module 4 and correlated with muscle cells related BPs, suggesting that MYH6 might also be used as a biomarker for the prognosis of DCM.

Conclusions

In conclusion, five potential biomarkers including LDHA, ALDOC, ABCE1, ATF4 and MYH6 were identified for DCM prognosis. During DCM progression, LDHA and ALDOC might have interplayed and play significant roles via regulation of the glycolysis process. However, these findings need to be further confirmed via extensive validation.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81100208).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

References

- 1.Sharma M, Nazareth I, Petersen I. Trends in incidence, prevalence and prescribing in type 2 diabetes mellitus between 2000 and 2013 in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e010210. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heather LC, Clarke K. Metabolism, hypoxia and the diabetic heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50(4):598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scirica B, Bhatt D, Braunwald E, et al. Saxagliptin and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1317–1326. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1307684.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acar E, Ural D, Bildirici U, et al. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2011;11(8):732–737. doi: 10.5152/akd.2011.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asghar O, Al-Sunni A, Khavandi K, et al. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. Clin Sci (Lond) 2009;116(10):741–760. doi: 10.1042/CS20080500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chavali V, Tyagi SC, Mishra PK. Predictors and prevention of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2013;6:151–160. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S30968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alabas OA, Hall M, Dondo TB, et al. Long-term excess mortality associated with diabetes following acute myocardial infarction: a population-based cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(1):25–32. doi: 10.1136/jech-2016-207402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung M, Wong VW, Heritier S, et al. Rationale and design of a randomized trial on the impact of aldosterone antagonism on cardiac structure and function in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013;12:139. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-12-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Q, Wang S, Cai Lu. Diabetic cardiomyopathy and its mechanisms: Role of oxidative stress and damage. J Diabetes Investig. 2014;5(6):623–634. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kajstura J, Fiordaliso F, Andreoli AM, et al. IGF-1 overexpression inhibits the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy and angiotensin II-mediated oxidative stress. Diabetes. 2001;50(6):1414–1424. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.6.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bugger H, Abel E. Molecular mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetologia. 2014;57(4):660–671. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3171-6.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu H, Lee J, Vincent LG, et al. Epigenetic regulation of phosphodiesterases 2A and 3A underlies compromised β-adrenergic signaling in an iPSC model of dilated cardiomyopathy. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17(1):89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drawnel FM, Boccardo S, Prummer M, et al. Disease modeling and phenotypic drug screening for diabetic cardiomyopathy using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Rep. 2014;9(3):810–821. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Churko JM, Sallam KI, Matsa E, et al. Epigenetic regulation of phosphodiesterases 2a and 3a underlies compromised b-adrenergic signaling in an iPSC model of dilated cardiomyopathy. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gautier L, Cope L, Bolstad BM, et al. Affy-analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(3):307–315. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horiuchi Y, Kano SI, Ishizuka K, et al. Olfactory cells via nasal biopsy reflect the developing brain in gene expression profiles: utility and limitation of the surrogate tissues in research for brain disorders. Neurosci Res. 2013;77(4):247–250. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smyth GK. Limma: Linear models for microarray data; Bioinformatics and computational biology solutions using r and bioconductor. Springer; 2005. pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang DaW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grossmann S, Bauer S, Robinson PN, et al. Improved detection of overrepresentation of Gene-Ontology annotations with parent child analysis. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(22):3024–3031. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Kuhn M, et al. 2011 functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D561–D568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhrissorrakrai K, Gunsalus KC, Rhrissorrakrai K, et al. MINE: Module Identification in Networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:192. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falcão-Pires I, Leite-Moreira AF. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: understanding the molecular and cellular basis to progress in diagnosis and treatment. Heart Fail Rev. 2012;17(3):325–344. doi: 10.1007/s10741-011-9257-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi SuMi, Kim Y, Shim JS, et al. Efficient drug screening and gene correction for treating liver disease using patient-specific stem cells. Hepatology. 2013;57(6):2458–2468. doi: 10.1002/hep.26237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolappan S, Shen DL, Mosi R, et al. Structures of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) in apo, ternary and inhibitor-bound forms. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2015;71(Pt 2):185–195. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714024791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ainscow EK, Zhao C, Rutter GA. Acute overexpression of lactate dehydrogenase-A perturbs beta-cell mitochondrial metabolism and insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2000;49(7):1149–1155. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.7.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y, Wang X, Shao X. A combination of human embryonic stem cell-derived pancreatic endoderm transplant with ldha-repressing miRNA can attenuate high-fat diet induced type II diabetes in mice. J Diabetes Res. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/796912. 796912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avogaro A, Toffolo G, Miola M, et al. Intracellular lactate- and pyruvate-interconversion rates are increased in muscle tissue of non-insulin-dependent diabetic individuals. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(1):108–115. doi: 10.1172/JCI118754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang G, Li W, Lu X, et al. Luteolin ameliorates cardiac failure in type I diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26(4):259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scornavacca G, Gesuete R, Orsini F, et al. Proteomic analysis of mouse brain cortex identifies metabolic down-regulation as a general feature of ischemic pre-conditioning. J Neurochem. 2012;122(6):1219–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thangarajah H, Yao D, Chang EI, et al. The molecular basis for impaired hypoxia-induced VEGF expression in diabetic tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(32):13505–13510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906670106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bohuslavova R, Kolar F, Sedmera D, et al. Partial deficiency of HIF-1α stimulates pathological cardiac changes in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-14-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang CF, Yuan CZ, Wang SH, et al. Differential gene expression of aldolase C (ALDOC) and hypoxic adaptation in chickens. Anim Genet. 2007;38(3):203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2007.01605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim ES, Isoda F, Kurland I, et al. Glucose-induced metabolic memory in Schwann cells: prevention by PPAR agonists. Endocrinology. 2013;154(9):3054–3066. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camps SG, Verhoef SPM, Roumans N, et al. Weight loss-induced changes in adipose tissue proteins associated with fatty acid and glucose metabolism correlate with adaptations in energy expenditure. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2015;12:37. doi: 10.1186/s12986-015-0034-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kashyap S, Belfort R, Gastaldelli A, et al. A sustained increase in plasma free fatty acids impairs insulin secretion in nondiabetic subjects genetically predisposed to develop type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52(10):2461–2474. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.10.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bao W, Aravindhan K, Alsaid H, et al. Albiglutide, a long lasting glucagon-like peptide-1 analog, protects the rat heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury: evidence for improving cardiac metabolic efficiency. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peng X, Gong F, Chen Y, et al. Autophagy promotes paclitaxel resistance of cervical cancer cells: involvement of Warburg effect activated hypoxia-induced factor 1-α-mediated signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1367. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szablewski L. Diabetes mellitus: influences on cancer risk. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2014;30(7):543–553. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen ZQ, Dong J, Ishimura A, et al. The essential vertebrate ABCE1 protein interacts with eukaryotic initiation factors. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(11):7452–7457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510603200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeng C, Yi X, Zipris D, et al. RNase L contributes to experimentally induced type 1 diabetes onset in mice. J Endocrinol. 2014;223(3):277–287. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fabre O, Breuker C, Amouzou C, et al. Defects in TLR3 expression and RNase L activation lead to decreased MnSOD expression and insulin resistance in muscle cells of obese people Cell Death Dis 20145e1136 10.1038/cddis.2014.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vasiliou V, Vasiliou K, Nebert DW. Human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family. Hum Genomics. 2009;3(3):281–290. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-3-3-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gok O, Karaali ZE, Acar L, et al. ABCG5 and ABCG8 gene polymorphisms in type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Turkish population. Can J Diabetes. 2015;39(5):405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ventura-Clapier R, Garnier A, Veksler V. Energy metabolism in heart failure. J Physiology. 2004;555(1):1–13. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.055095.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Solbach TF, Paulus B, Weyand M, et al. ATP-binding cassette transporters in human heart failure. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2008;377(3):231–243. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Licht A, Schneider E. ATP binding cassette systems: structures, mechanisms, and functions. Open Life Sciences. 2011;6(5):785–801. doi: 10.2478/s11535-011-0054-4.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Z, Zhang T, Dai H, et al. Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress in myocardial apoptosis of streptozocin-induced diabetic rats. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2007;41(1):58–67. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.2007008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Z, Zhang T, Dai H, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is involved in myocardial apoptosis of streptozocin-induced diabetic rats. J Endocrinology. 2010;207(1):123. doi: 10.1677/joe-07-0230r.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu J, Zhou Qi, Xu W, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and diabetic cardiomyopathy. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/827971. 827971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu J, Liu Yu, Chen Li, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 analog liraglutide protects against diabetic cardiomyopathy by the inhibition of the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. J Diabetes Res. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/630537. 630537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Howarth FC, Qureshi MA, Hassan Z, et al. Changing pattern of gene expression is associated with ventricular myocyte dysfunction and altered mechanisms of Ca2+ signalling in young type 2 Zucker diabetic fatty rat heart. Exp Physiol. 2011;96(3):325–337. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2010.055574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shinozawa T, Imahashi K, Sawada H, et al. Determination of appropriate stage of human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes for drug screening and pharmacological evaluation in vitro. J Biomol Screen. 2012;17(9):1192–1203. doi: 10.1177/1087057112449864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.