Abstract

Background

Fibrosis of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is common and compromises both systolic and diastolic function. The aim of this study was to investigate the kinetics of ECM fibrosis markers over a 12 month follow-up in patients with DCM based on the severity of diastolic dysfunction (DD).

Methods

Seventy consecutive DCM patients (48 ± 12.1 years, ejection fraction 24.4 ± 7.4%) were included in the study. The grade of DD was determined using the ASE/EACVI algorithm. Markers of ECM fibrosis were measured at baseline and at 3 and 12 month follow-ups: collagen type I and III (PICP, PINP, PIIICP, PIIINP), transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF1-β), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and galectin-3 were measured.

Results

Patients were divided into three groups according to DD severity: 30 patients with grade I, 18 with grade II and 22 with grade III of DD. Levels of PICP, PINP were increased over a 12-month period, while PIIINP decreased and PIIICP unchanged. Levels of TGF1-β decreased from the 3 to the 12-month points in grade I and II DD, and in grade III they remained unchanged. Levels of CTGF decreased over 12 months in grade III DD but were unchanged in grades I and II. Galectin-3 levels remained the same over all observation periods, irrespective of DD grade.

Conclusions

Regardless of the DD grade, markers of collagen type I synthesis increased, markers of collagen type III decreased. Levels of TGF and CTGF had a tendency to decrease. Galectin-3 was revealed not to be a marker discriminating the severity of DD.

Keywords: dilated cardiomyopathy, diastolic dysfunction, markers of fibrosis

Introduction

The prevalence of heart failure (HF) is 1–2% of the adult population in developed countries [1]. According to the current classification of diastolic dysfunction (DD), virtually all patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) have at least a mild degree of DD [2]. Irrespective of HF etiology, e.g. ischemic or non-ischemic, progressive abnormalities in the extracellular matrix (ECM) result in a gradual worsening of both systolic and diastolic function. Reactive fibrosis of ECM typically is observed in dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and importantly contributes to HF progression. Altered components of ECM, e.g. relative increase of collagen type I over III, leads to the stiffening of the myocardium and further worsening DD. Thus, ECM fibrosis and DD seems to be interrelated.

Extracellular matrix fibrosis can be studied directly by means of endomyocardial biopsy or non-invasively with magnetic resonance. Furthermore, measurement of serum markers of fibrosis may provide insight into myocardial pathology. The dynamics of collagen turnover may be studied via circulating markers of collagen synthesis which are released into the bloodstream during conversion into the mature collagens [3–5]. In addition, levels of fibrosis controlling factors, including transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF1-β), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) or galectin-3 may also indicate ongoing ECM fibrosis [6]. Numerous studies have explored the role of serum markers of fibrosis in various cardiac disorders, including HF, DCM and hypertension. In the majority of these studies only single measurements of markers of interests were performed and, based on those baseline values, associations were investigated. Conversely, a minority of studies examined for the kinetics of those markers, which may be equally important as patterns of biomarkers over time may be more relevant than single measures.

Under a previous investigation, 12-month kinetics of serum markers of collagen synthesis, TGF and CTGF, in DCM patients were stratified according to duration of disease and fibrosis status [7]. Different patterns of these markers were observed over time in patients with and without ECM fibrosis. Despite an extensive literature search, no studies were found exploring the relationship between the kinetics of serum markers and DD in patients with DCM. Therefore, in this study, the aim was to investigate changes over time in selected markers of fibrosis in DCM patients stratified on the basis of DD over a 12-month observation period.

Methods

Study groups

From July 2014 to October 2015, 70 consecutive patients with DCM were included. DCM was diagnosed according to the current European Society of Cardiology 2007 guidelines after exclusion of significant coronary artery disease, primary heart valve disease, congenital heart disease and arterial hypertension [8]. All patients were in the New York Heart Association (NYHA) class I–III for at least 2 preceding weeks. An assessment of patient status, echocardiographic examinations and blood sampling were repeated at 3 and 12 months. The study protocol was approved by the relevant institutional committees and ethics committees. All patients gave written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study. During the study, 4 (5.7%) patients died within the first 3 months and another 2 (3%) within 12 months. Thus, there were 64 (94.3%) patients which comprised follow-up data.

Echocardiography

All measurements, including DD assessment, were performed according to the recommendations of the European Associations of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) [2]. Based on the EACVI algorithm, DCM patients were divided into three groups; grade I, II or III DD.

Laboratory measurements

Venous blood samples and laboratory testing of serum markers of fibrosis were conducted using methods described in recent papers [9]. The concentrations of collagen synthesis markers and fibrosis controlling markers were determined in plasma using a commercially available ELISA tests as follows: collagen type 1 (manufacture reference values 46.7–178.9 pg/mL), procollagen I N-terminal propeptide (PINP 30.2–55.1 pg/mL), procollagen III N-terminal propeptide (PIIINP 2.69–63.56 ng/mL), procollagen I C-terminal propeptide (PICP 64–186 pg/mL = 0.064–0.186 ng/mL), procollagen III C-terminal propeptide (PIIICP 5.2–35.5 ng/mL), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF 2.3–42.5 ng/mL) (all from Cloud Clone Corp. Houston, TX, USA); TGF1-β (4.639–14.757 pg/mL = 4.639–14.757 ng/mL) (Diaclone SAS, Besancon Cedex, France), galectin-3 (4–114 ng/mL) (Abbott Diagnostics, Vienna, Austria). All measurements were performed by technicians blinded to the sample status. Intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were < 7%.

Statistical analysis

The normality of distribution of variables was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Comparisons of clinical parameters in the three groups were conducted with the Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA nonparametric analysis of variance, with repeated measurements since differences between the time-points were not distributed normally. A post-hoc analysis was conducted with the Dunnett test which is designed for heterogeneous covariance. All results were considered statistically significant when p value was < 0.05. Statistical analysis was conducted with Statistica version 13.1 software.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of patients in the three groups of patients stratified according to DD grade. Patients with grade II DD had significantly larger left ventricular end-systolic diameter as assessed by body surface area (34.1 mm/m2), while there were no differences in patients with grade I and III DD. E-wave and A-wave had significantly higher values in grade II and grade III DD in comparison to grade I DD while E/A ratio was highest in patients with grade III DD [2, 9]. There were no differences in age, gender, NYHA classification or body mass index between the groups. Patients with grade I DD had the highest concentration of hemoglobin (15.1 g/dL), while patients with grade II and grade III DD had significantly higher level of amino-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (5627.8 pg/mL and 6802 pg/mL, respectively). No differences were observed in the frequency of sinus rhythm, atrial fibrillation or duration of QRS between the groups. All patients were receiving optimal HF pharmacotherapy but patients with grade III DD required a loop diuretic more often. There were also no differences in implantable cardioverter-defibrillator or cardiac resynchronization therapy with cardioverter-defibrillator implantations between groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population divided according to diastolic dysfunction grade.

| Parameter | Diastolic dysfunction | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Grade I | Grade II | Grade III | ||

| Number | 30 | 18 | 22 | |

| Age [years] | 48.4 (42–53) | 47.61 (39–56) | 47.96 (36–61) | 0.99 |

| Sex (male/female) | 27/3 | 18/0 | 18/4 | 0.16 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 28.166 (24.5–31.2) | 25.3 (21–30) | 27.6 (22.3–30.9) | 0.16 |

| NYHA class (I–IV) | 2.37 ± 0.76 | 2.57 ± 0.73 | 2.77 ± 0.61 | 0.08 |

| LVESD/BSA [mm/m2] | 27.6 (24.4–30.5)*** | 34.10 (26–39) | 31.43 (29.3–35.5) | 0.01 |

| LVEDD/BSA [mm/m2] | 33.9 (29.5–36) | 39.7 (33–43.5) | 35.99 (32.2–40.5) | 0.06 |

| E-wave [m/s] | 0.6 (0.48–0.7)*** | 0.79 (0.62–0.9) | 0.94 (0.77–1.04)* | 0.00 |

| A-wave [m/s] | 0.7 (0.6–0.76)*** | 0.44 (0.34–0.59) | 0.34 (0.25–0.4)* | 0.00 |

| E/A ratio | 0.86* | 1.43 | 2.9** | 0.00 |

| LVEF [%] | 26.4 (20–33) | 23.39 (17–30) | 22.46 (17–25) | 0.14 |

| ECG rhythm sinus/AFL/cardiac stimulator | 26/4/0 | 11/5/2 | 19/2/1 | 0.06 |

| QRS complex [ms] | 103.67(80–120) | 115.56(80–140) | 22.46 (17–25) | 0.14 |

| Hemoglobin [g/dL] | 15.10 (14.6–16.0)*** | 13.76 (12.6–15.2) | 14.1 (13.2–15) | 0.004 |

| Creatinine [μmol/L] | 83.43 (68–96) | 92.11 (72–112) | 114.41 (13.2–15) | 0.07 |

| eGFR [mL/min] | 94.07 (81–107) | 82.19 (65.5–102) | 76.3 (57–104) | 0.04 |

| NT-proBNP [pg/mL] | 1917 (296–1898)*** | 5627.8 (1736–5060) | 6802 (1211–4924)* | 0.00 |

| Beta-blocker | 29 (96.7%) | 18 (100%) | 22 (100%) | 0.51 |

| ACEI/ARB | 28 (93.3%)/1 (6.7%) | 16 (88.9%)/1 (1.1%) | 22 (100%)/0 (0%) | 0.31/0.57 |

| MRA | 28 (93.3%) | 18 (100%) | 20 (90.9%) | 0.45 |

| Furosemidum | 9 (30%)*** | 15 (83.3%) | 17 (77.3%)* | 0.00 |

| Vitamin K antagonist | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.5%) | 0.68 |

| NOAC | 3 (10%) | 3 (16.7%) | 1 (4.5) | 0.45 |

| ICD/CRT-D | 7 (23.3%) | 10 (55.6%) | 9 (40.9%) | 0.13 |

p-values for comparison between grades I, II, and III diastolic dysfunction (DD): p < 0.05 (grade I DD vs. grade III DD);

p-values for comparison between grades I, II, and III diastolic dysfunction (DD): p < 0.05 (grade II DD vs. grade III DD);

p-values for comparison between grade I, II, and III diastolic dysfunction (DD): p < 0.05 (grade I DD vs. grade II DD);

ACEI — angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; AFL — atrial flutter; ARB — angiotensin receptor type 1 blocker; A-wave — late mitral inflow velocity; BMI — body mass index; CRT-D — cardiac resynchronization therapy with cardioverter-defibrillator; E/A — ratio of early mitral inflow E-wave and late mitral inflow A-wave velocity; ECG — electrocardiogram; eGFR — estimated glomerular filtration rate; E-wave — early mitral inflow velocity, ICD— implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LVEDD/BSA — indexed to body surface area left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF — left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD/BSA — indexed to body surface area left ventricular end-systolic diameter; MRA — mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NOAC — non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants; NT-proBNP — amino-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA — New York Heart Association class

Kinetics of the serum markers of fibrosis in patients with grade I diastolic dysfunction

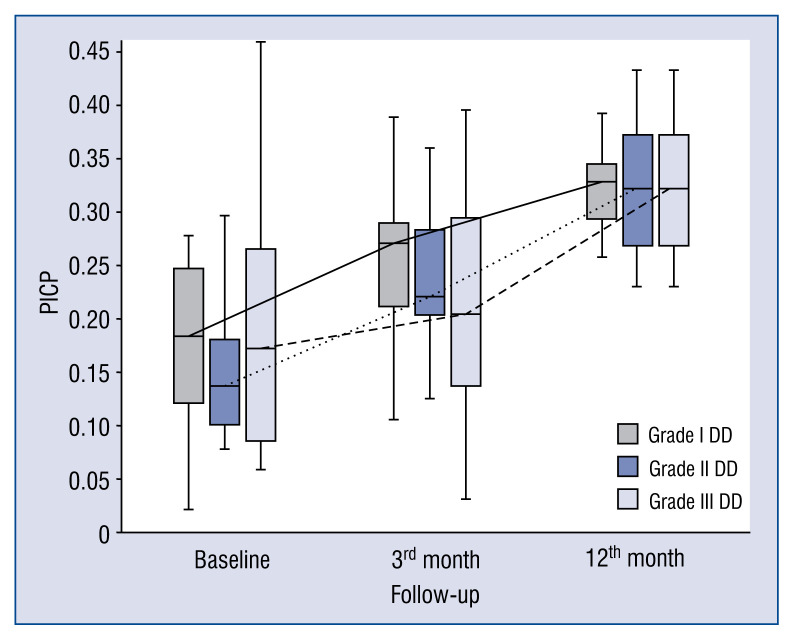

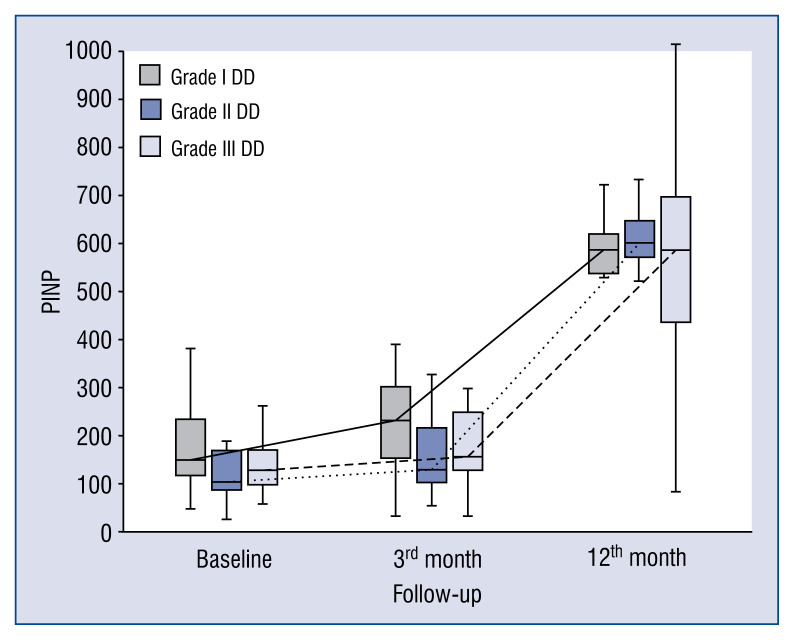

Baseline, 3 and 12-month levels of serum markers of collagen synthesis, TGF1-β, CTGF and galectin-3 in patients with DD grade I are presented in the Figure 1. Blood levels of markers of collagen type I synthesis (PICP and PINP) consistently increased from baseline to the 3- and 12-month observation points. In contrast, dynamics of markers of collagen type III synthesis behaved in the opposite manner. Changes in markers of collagen type III synthesis (PIIICP) were not significant, whereas PIIINP levels decreased during the observation period. TGF1-β values were unchanged from baseline to the 3-month time-point but decreased significantly between the 3- and 12-month time-point. Finally, levels of CTGF and galectin-3 did not change over the observational period.

Figure 1.

Comparison of baseline, 3- and 12-month serum levels of procollagen type I carboxy-terminal peptide (PICP) in patients with different diastolic dysfunction (DD) grades.

Kinetics of the serum markers of fibrosis in patients with grade II diastolic dysfunction

Baseline, 3- and 12-month levels of serum markers of collagen synthesis, TGF1-β, CTGF and galectin-3 in patients with DD grade I are presented in Figure 2. Blood levels of collagen type I synthesis marker — PICP consistently increased from baseline to the 3- and 12-month time-points, whereas PINP increased from the 3- to 12-month time-point. Markers of collagen type III synthesis, PIIICP and PIIINP, behaved differently. PIIICP increased significantly over the period of observation but PIIINP decreased over a longer observation period between 3 to 12 months. TGF1-β blood levels did not differ between baseline and 3-month follow-up, however it decreased between 3- and 12-month time-points. Levels of CTGF and galectin-3 remained unchanged over 12-months of observation.

Figure 2.

Comparison of baseline, 3- and 12-month serum levels of procollagen type I amino-terminal peptide (PINP) in patients with different diastolic dysfunction (DD) grades.

Kinetics of the serum markers of fibrosis in patients with grade III diastolic dysfunction

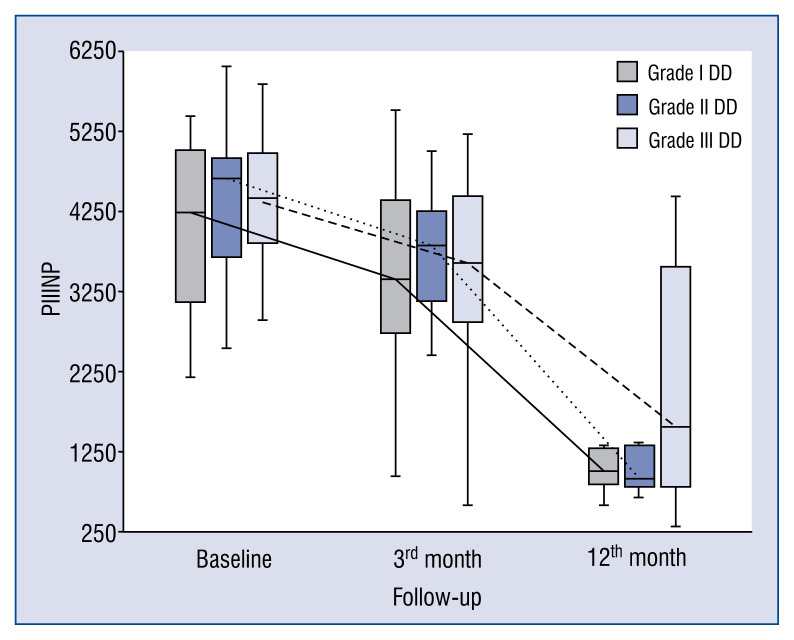

Baseline, 3- and 12-month levels of serum markers of collagen synthesis, TGF1-β, CTGF and galectin-3 in patients with DD grade I are presented in the Figure 3. Levels of markers of collagen type I synthesis PICP and PINP remained unchanged from baseline to 3-month time-point but both increased between 3- and 12-month time-points. Changes in PIIICP were not significant, whereas values of PIIINP significantly decreased over a longer period of observation from baseline to 12 months and from 3 to 12 months. TGF1-β blood levels remained unchanged over 12 months of observation, whereas CTGF levels decreased between baseline and 12 months. Finally, levels of galectin-3 did not differ between baseline, 3- and 12-month time-points.

Figure 3.

Comparison of baseline, 3- and 12-month serum levels of procollagen type III amino-terminal peptide (PIIINP) in patients with different diastolic dysfunction (DD) grades.

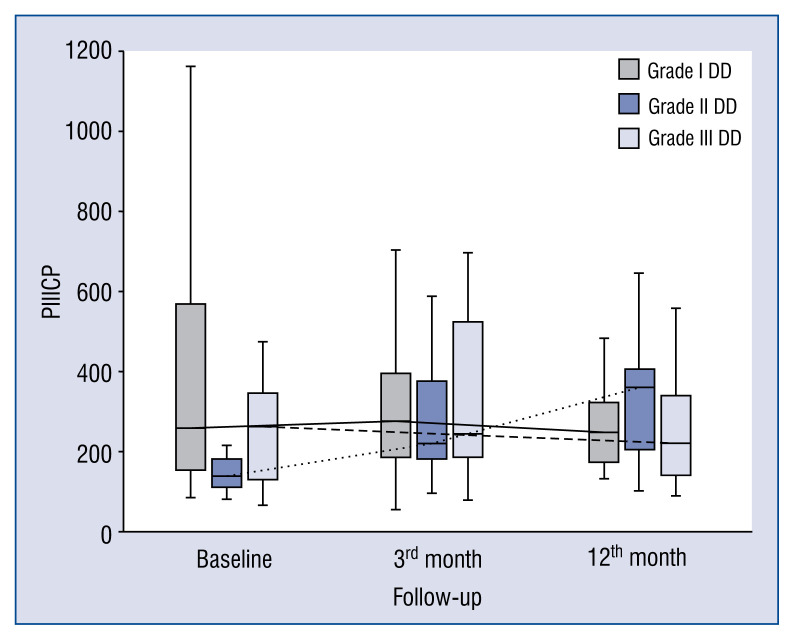

Comparison of kinetics of serum markers of fibrosis between patients with various grades of diastolic dysfunction

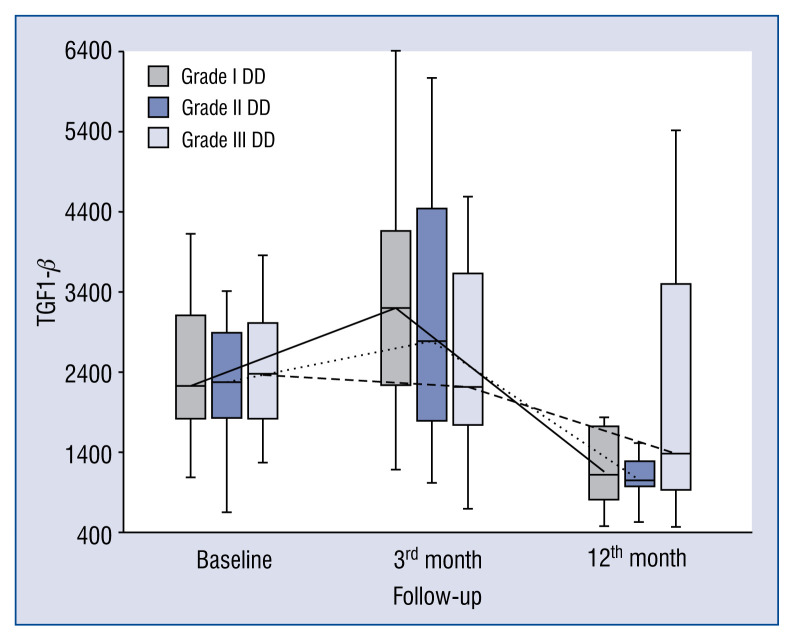

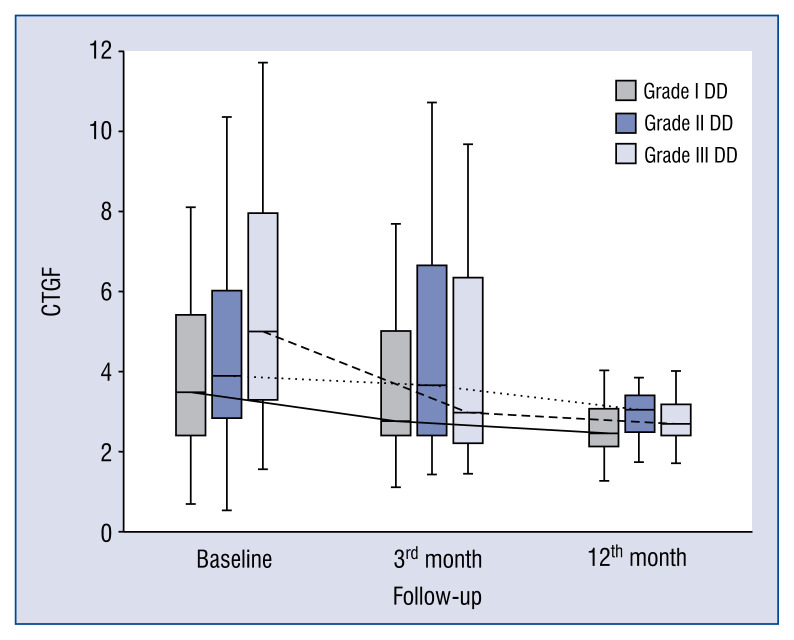

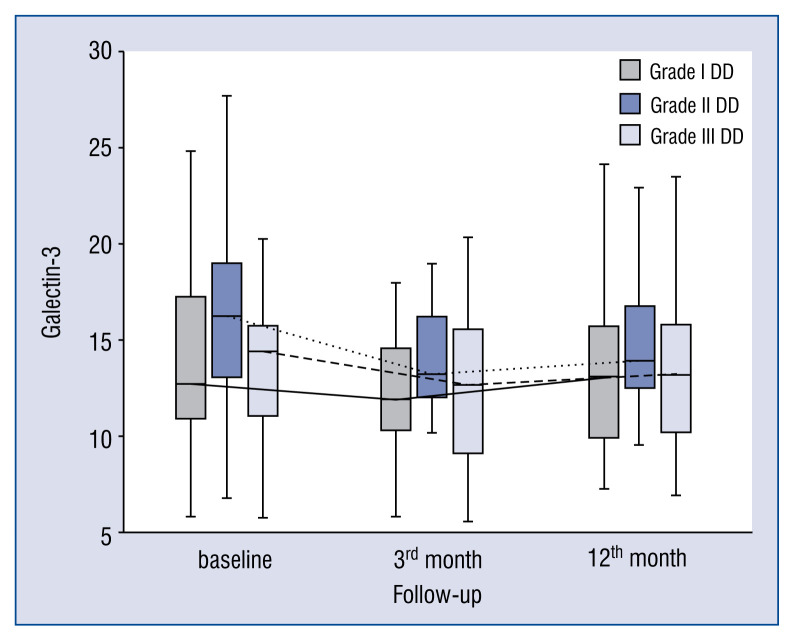

In general, the kinetics of markers of collagen type I and III synthesis did not differ between patients with different DD grades, e.g. markers of collagen type I synthesis (PICP, PINP) increased (Figs. 1, 2), whereas markers of collagen type III synthesis (PIIINP) decreased over the 12-month period of observation regardless of DD grade (Fig. 3). However, it should be noted that the baseline values of PIIICP were higher and similar in grade I and grade III DD in comparison to patients with grade II DD (Fig. 4). Conversely, levels of PINP at the 3 months were significantly higher in grade I compared to grade II and III DD. Blood levels of TGF1-β and CTGF did not differ at baseline, at 3- and 12-months of observation, regardless of DD grade. The kinetics of TGF1-β were initially unchanged (during the first 3 months) of observation and then decreased (between 3 to 12 months) in patients with grade I and II DD, but the kinetics did not change during the observation period in patients with grade III DD (Fig. 5). The kinetics of CTGF were similar in patients with different DD grades and, while levels had a tendency to decrease, significant changes could only be observed in patients with grade III DD (Fig. 6). Finally, galectin-3 levels did not differ between patients with different DD grades either at baseline nor at 3- and 12-month observational points (Fig. 7).

Figure 4.

Comparison of baseline, 3- and 12-month serum levels of procollagen type III carboxy-terminal peptide (PIIICP) in patients with different diastolic dysfunction (DD) grades.

Figure 5.

Comparison of baseline, 3- and 12-month serum levels of transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF1-β) in patients with different diastolic dysfunction (DD) grades.

Figure 6.

Comparison of baseline, 3- and 12-month serum levels of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in patients with different diastolic dysfunction (DD) grades.

Figure 7.

Comparison of baseline, 3- and 12-month serum levels of galectin-3 in patients with different diastolic dysfunction (DD) grades.

Correlations between serum markers of fibrosis and diastolic function parameters

A weak negative correlation was observed between baseline serum levels of PINP and baseline left atrial volume index (LAVI) (r = −0.3; p < 0.05) and between baseline PINP and LAVI at 3 months (r = −0.29; p < 0.05). At 12 months, there was a moderate correlation between PINP and E/A ratio (r = 0.46; p < 0.05). As markers of collagen type III synthesis, PIIINP negatively correlated with E/E’ ratio and E’ (r = −0.4 and r = −0.34; p < 0.05) at 3 months and with E’ at 12 months (r = −0.31; p < 0.05), whereas PIIICP at 12 months correlated with E/E’ and LAVI (r = 0.34; r = 0.36; p < 0.05, respectively). TGF1-β at baseline correlated with LAVI (r = −0.33; p < 0.05). CTGF at 3 months correlated with E/E’ at 12 months (r = 0.3; p < 0.05) and CTGF at 12 months correlated with E/E’ at 12 months (r = 0.31; p < 0.05). Galectin-3 at baseline correlated with tricuspid regurgitation velocity and E-wave (r = 0.3 and r = 0.26; p < 0.05, respectively). Galectin-3 at 3 months correlated with 3-month E’ velocity (r = 0.42; p < 0.05) and between 3-month and baseline E/A ratio and tricuspid regurgitation velocity (r = 0.28; p < 0.05 and r = 0.27; p < 0.05, respectively).

Discussion

Kinetics of collagen synthesis markers in patients with various grades of diastolic dysfunction

The process of ECM fibrosis in DCM has been extensively studied. However, the kinetics of collagen synthesis markers and its relationship to DD are poorly understood. While several papers discussed selected markers of fibrosis and the development of DD, few refer to DD in DCM. The present study is the first to report that long term (12th-month period) synthesis of collagen type I is enhanced, whereas synthesis of collagen type III is diminished in DCM patients, regardless of diastolic dysfunction degree. Intuitively, it may be thought that patients with more advanced DD (restrictive filling) have higher collagen synthesis but in fact collagen type I synthesis is uniformly increased in all DD groups. Collagens types I and III have different physical properties, e.g. collagen type I has a higher tensile strength and collagen type III is more elastic and complaint [10, 11]. Thus, an increase in collagen type I may contribute to further worsening of DD. Consequently, collagen I and III ratios remained the same in patients with various DD grades. Of note, among markers of collagen type III synthesis (PIIICP and PIIINP), only PIIINP levels significantly decreased during the whole period, while PIIICP behaved differently, with a tendency to decrease and only increase in grade II DD. This observation cannot be easily explained, but it should be emphasized that only PIIINP is a truly proven marker of collagen synthesis, while the role of PIIICP is less clear [12].

Few studies have demonstrated the relationship between markers of collagen synthesis and DD under differing cardiac conditions. The most frequently described marker, which exhibited an association with DD was PICP. Demir et al. [13] has shown that hypertensive patients with DD had a significantly higher serum level of PICP compared to those without DD. Another group reported that the serum level of PICP was related to DD in patients with early stage type 2 diabetes mellitus [14]. Roongsritong and colleagues also described the relationship between PICP and DD in elderly patients [15]. It should be emphasized that those studies reported associations between particular markers of fibrosis and DD but no relationships were found between those markers and degree of DD. Only a few researchers have discussed this issue. Roongsritong et al. [16] has shown that PICP was related to the severity of DD in patients with HFrEF. They observed that the PICP level was significantly higher among patients with a more severe degree of DD compared to those with less severe DD. In the present study, no correlation was observed between PICP and DD grade. However, it should be noted that the authors used a currently outdated approach to DD classification and consequently compared only two groups of patients with non-severe (mild to moderate) and severe DD [16]. Therefore, from a methodological point of view it is impossible to compare the results of the present study to those observed by Roongsritong et al. [16]. The current observations showed that PINP correlated with the E/A ratio, a crucial parameter in the DD algorithm. This may suggest that patients with advanced DD and a higher E/A ratio had a higher level of PINP. Further, Rossi et al. [17] compared serum levels of PIIINP between three groups with DD with non-restrictive, reversible restrictive and irreversible restrictive filling patterns. The authors observed that PIIINP was significantly higher in patients with a restrictive mitral inflow pattern [17]. However, the classification of patients according to mitral inflow pattern, described in the cited study, varies from the current grading of DD. In addition to the fact that this classification of DD is no longer used, the authors compared unmatched patient groups, with 9 patients having restrictive versus 88 patients having a non-restrictive filling pattern. In the present study, a negative correlation between PIIINP and E/E’ ratio was demonstrated. This may suggest that patients with grade I DD and a lower E/E’ ratio had higher serum levels of PIIINP. This observation seems accurate, since a heart muscle rich in collagen III is characterized by greater flexibility and elasticity and therefore has an improved diastolic function.

Kinetics of TGF, CTGF and galectin-3 in patients with various diastolic dysfunction grades

Levels of TGF1-β were similar regardless of the DD grade and the kinetics of TGF1-β did not differ between the subgroups. Numerous studies have confirmed that TGF and its downstream mediator — CTGF are crucial molecules stimulating cardiac fibrosis [18]. Thus, one may speculate that TGF1-β would be highest in patients with grade III DD. However, observed herein was that TGF levels were similar in all three DD groups. One possible explanation is that serum levels of TGF are not equivalent to the expression of TGF in the myocardium [19]. Additionally, not all of TGF1-β but only its active forms are involved in biological processes, and, as confirmed earlier, levels of TGF1-β and its active metabolites may not be correlated [20]. Conversely, the pro-fibrotic mechanisms of TGF1-β includes not only differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, which have higher activity for collagen production, but also a differentiation throughout its effector cytokine — CTGF [21, 22]. In the present study, serum levels of CTGF did not differ significantly between the subgroups but a positive correlation was observed between CTGF and E/E’ ratio. This may suggest that patients with more advanced DD (higher E/E’ ratio) had higher levels of CTGF. Wu et al. [23] reached similar conclusions and demonstrated that serum levels of CTGF were the highest among patients with severe DD. With respect to the 12-month kinetics of CTGF levels were found to decrease homogenously in all patients regardless of DD severity but significant changes were only observed in grade III of DD.

Galectin-3 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of left ventricular remodeling [24]. Only a few studies have examined the relationship between galectin-3 and DD in HF. Wu et al. [25] reported correlations between plasma galectin-3 and E/E’ in advanced HFpEF. Gurel et al. [26] demonstrated that galectin-3 was an independent predictor of DD in patients with end-stage renal failure undergoing dialyses. Another study compared serum levels of galectin-3 in patients with HFrEF and HFpEF and demonstrated that it was higher in patients with HFrEF and correlated with E/E’ ratio [27]. Observed herein, was that galectin-3 levels were similar regardless of DD grade and remained stable over 12 months. However, a positive correlation between galectin-3 and E’-wave which reflects the rate of myocardial relaxation [28] was also observed. Nevertheless, based on the analysis, serum levels of galectin-3 seemed not to be a good marker of DD severity in DCM. One possible explanation could be that circulating galectin-3 does not correlate with its myocardial expression as has been recently reported by Besler et al. [29].

In summary, 12-month kinetics of fibrosis controlling molecules (TGF, CTGF, and galectin-3) were similar in three DD groups. Furthermore, the pattern of TGF and CTGF was the same and decreasing, and as such is probably not a good target for eventual anti-TGF or anti-CTGF agents, provided that blood expression of those molecules have any relations with their myocardial counterparts or fibrosis progression, which at present is uncertain. What is more, it should be reiterated that the fact that none of the seven markers of fibrosis under study turned out to have a different pattern in all three DD groups and thus, none can serve as a marker of DD degree.

Limitations of the study

There are several potential limitations to this study. The division of DCM patients was based on the current DD classification, resulting in relatively small subgroups, which may have impacted statistical relevance. As reported in previous studies, serum levels of ECM fibrosis markers might not reflect their myocardial expression and thereby may only be weakly correlated with myocardial function.

Conclusions

Twelve-month kinetics of serum markers of fibrosis in DCM patients with various grades of DD is characterized with similar patterns. Regardless of the DD grade, markers of collagen type I synthesis increased and markers of collagen type III decreased (mainly PIIINP). Levels of TGF and CTGF had a tendency to decrease over the observation period, whereas kinetics of galectin-3 was stable. This observation may indicate that the presence of myocardial fibrosis is just one component, among others, that affects DD.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded through the National Science Center, Poland (Grant 2013/09/D/NZ5/00252) and the Department of Scientific Research and Structural Funds of Medical College, Jagiellonian University (Grant K/ZDS/004596).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

References

- 1.Ponikowski P, Voorse AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:891–975. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016;29(4):277–314. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubiś P, Totoń-Żurańska J, Wiśniowska-Śmiałek S, et al. Right ventricular morphology and function is not related with microRNAs and fibrosis markers in dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiol J. 2017 doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2017.0099. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Querejeta R, López B, González A, et al. Increased collagen type I synthesis in patients with heart failure of hypertensive origin: relation to myocardial fibrosis. Circulation. 2004;110(10):1263–1268. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140973.60992.9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klappacher G, Franzen P, Haab D, et al. Measuring extracellular matrix turnover in the serum of patients with idiopathic or ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy and impact on diagnosis and prognosis. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75(14)(99):913–918. 80686–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobaczewski M, Chen W, Frangogiannis NG. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling in cardiac remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51(4):600–606. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubiś P, Wiśniowska-Smiałek S, Wypasek E, et al. 12-month patterns of serum markers of collagen synthesis, transforming growth factor and connective tissue growth factor are similar in new-onset and chronic dilated cardiomyopathy in patients both with and without cardiac fibrosis. Cytokine. 2017;96:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lang R, Badano L, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16(3):233–271. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev014.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubiś P, Wiśniowska-Śmialek S, Wypasek E, et al. Fibrosis of extracellular matrix is related to the duration of the disease but is unrelated to the dynamics of collagen metabolism in dilated cardiomyopathy. Inflamm Res. 2016;65(12):941–949. doi: 10.1007/s00011-016-0977-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marijianowski MM, Teeling P, Mann J, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy is associated with an increase in the type I/type III collagen ratio: a quantitative assessment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25(6)(94):1263–1272. 00557–7. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pauschinger M, Knopf D, Petschauer S, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy is associated with significant changes in collagen type I/III ratio. Circulation. 1999;99(21):2750–2756. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.21.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Izawa H, Murohara T, Nagata K, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism ameliorates left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and myocardial fibrosis in mildly symptomatic patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: a pilot study. Circulation. 2005;112(19):2940–2945. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.571653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demir M, Acartürk E, Inal T, et al. Procollagen type I carboxy-terminal peptide shows left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction in hypertensive patients. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2007;16(2):69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ihm SH, Youn HJ, Shin DI, et al. Serum carboxy-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen (PIP) is a marker of diastolic dysfunction in patients with early type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Cardiol. 2007;122(3):e36–e38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roongsritong C, Bradley J, Sutthiwan P, et al. Elevated carboxy-terminal peptide of procollagen type I in elderly patients with diastolic dysfunction. Am J Med Sci. 2006;331(3):131–133. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roongsritong C, Sadhu A, Pierce M, et al. Plasma carboxy-terminal peptide of procollagen type I is an independent predictor of diastolic function in patients with advanced systolic heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2008;14(6):302–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2008.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossi A, Cicoira M, Golia G, et al. Amino-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen is associated with restrictive mitral filling pattern in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: a possible link between diastolic dysfunction and prognosis. Heart. 2004;90(6):650–654. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2002.005371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glazer NL, Macy EM, Lumley T, et al. Transforming growth factor beta-1 and incidence of heart failure in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Cytokine. 2012;60(2):341–345. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hein S, Arnon E, Kostin S, et al. Progression from compensated hypertrophy to failure in the pressure-overloaded human heart: structural deterioration and compensatory mechanisms. Circulation. 2003;107(7):984–991. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051865.66123.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan SA, Joyce J, Tsuda T. Quantification of active and total transforming growth factor-β levels in serum and solid organ tissues by bioassay. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:636. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petrov VV, Fagard RH, Lijnen PJ. Stimulation of collagen production by transforming growth factor-beta1 during differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. Hypertension. 2002;39(2):258–263. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Accornero F, van Berlo JH, Correll RN, et al. Genetic analysis of connective tissue growth factor as an effector of transforming growth factor β signaling and cardiac remodeling. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35(12):2154–2164. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00199-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu CK, Wang YC, Lee JK, et al. Connective tissue growth factor and cardiac diastolic dysfunction: human data from the Taiwan diastolic heart failure registry and molecular basis by cellular and animal models. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16(2):163–172. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Boer RA, Yu L, van Veldhuisen DJ. Galectin-3 in cardiac remodeling and heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2010;7(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11897-010-0004-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu CK, Su MY, Lee JK, et al. Galectin-3 level and the severity of cardiac diastolic dysfunction using cellular and animal models and clinical indices. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17007. doi: 10.1038/srep17007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gurel OM, Yilmaz H, Celik TH, et al. Galectin-3 as a new biomarker of diastolic dysfunction in hemodialysis patients. Herz. 2015;40(5):788–794. doi: 10.1007/s00059-015-4303-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michalski B, Trzciński P, Kupczyńska K, et al. The differences in the relationship between diastolic dysfunction, selected biomarkers and collagen turn-over in heart failure patients with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Cardiol J. 2017;24(1):35–42. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2016.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ommen SR, Nishimura RA, Appleton CP, et al. Clinical utility of Doppler echocardiography and tissue Doppler imaging in the estimation of left ventricular filling pressures: A comparative simultaneous Doppler-catheterization study. Circulation. 2000;102(15):1788–1794. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.15.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Besler C, Lang D, Urban D, et al. Plasma and cardiac galectin-3 in patients with heart failure reflects both inflammation and fibrosis: implications for its use as a biomarker. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10(3) doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]