Abstract

Background:

The 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging introduced depth of invasion (DOI) into the pT category of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. However, we noted multiple practical obstacles in accurately measuring DOI histologically in our daily practice.

Objective and methods:

Aiming to compare the prognostic effects of DOI and tumor thickness (TT), a meticulous pathology review was conducted in a retrospective cohort of 293 patients with AJCC 7th edition pT1/T2 oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Overall survival (OS) and nodal metastasis rate at initial resection were the primary and secondary outcomes, respectively.

Results:

We found that TT and DOI were highly correlated with a correlation coefficient of 0.984. The upstage rate was merely 6% (18 out of 293 patients) when using TT in the pT stage compared with using DOI. More importantly, DOI, TT, as well as pT stage using DOI and pT stage using TT performed identically in predicting risk of nodal metastasis and OS.

Conclusions:

We therefore propose to replace DOI, a complicated measurement with many challenges, with TT in the pT staging system.

Keywords: Oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma, depth of invasion, tumor thickness, AJCC staging, prognosis

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), which includes oral tongue (OTSCC), is the most common malignancy in the head and neck region, with an increasing incidence and mortality rates in most developing countries 1. The American Cancer Society has estimated that approximately 53,260 new cases of oral and oropharyngeal cancer will be diagnosed in the US in 2020, with roughly 10,750 deaths, accounting for 90% of all head and neck cancers 1.

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) staging system is the most widely used staging scheme in patients with cancer, defining prognosis, and guiding the most appropriate treatment plans 2, 3. Two important related yet distinctly different pathologic parameters, being tumor thickness (TT) and depth of invasion (DOI), have been defined in the two most recent AJCC staging manuals (7th edition and 8th edition) for OSCC and OTSCC 2, 3. The AJCC 7th edition only defined TT, a parameter not included in the pT staging. TT is measured from the surface of the invasive squamous cell carcinoma for an endophytic or an exophytic tumor, and from the ulcer base for an ulcerated tumor to the deepest point of invasion 3.

In contrast, the current AJCC 8th edition provides a clearer definition of DOI and includes DOI as a parameter for T staging, whereas TT has been excluded from the most recent staging manual 2. DOI is defined as the measurement from the horizon of the basement membrane of the adjacent uninvolved mucosa perpendicularly to the deepest point of invasion 2. According to reviews and commentary published by the AJCC staging expert panel, the decision to include DOI as part of the pathology T (pT) category is largely based on an international collaborative retrospective study of 3149 patients with OSCC, which demonstrates that DOI with two different cut offs of 5 mm and 10 mm was an independent prognostic factor for disease specific survival (DSS) on multivariate analysis. However, this particular study did not address the prognostic significance of TT. Additionally, it was based upon center-specific definition and measuring techniques for DOI, which raise concerns on whether the study utilized a universal diagnostic criterion for DOI as described by AJCC 8th edition.

Prior to the introduction of the AJCC 8th edition, many studies have used the two terms TT and/or DOI interchangeably. Others did not include a clear definition of either measurement or simply defined each parameter inconsistently.4–9. As a result, the prognostic significance of TT and DOI data in OSCC and OTSCC were conflicting and have generated considerable discussion over the years.

Such remains even after the publication of the AJCC 8th edition. A recent survey of 159 surgeons has shown that 18% of the survey participants define DOI as the distance from the mucosal surface of the tumor to the deepest point of invasion, which is the exact definition of TT 10. Additionally, a large retrospective study published in 2019 has also defined DOI using the criterion of TT as length measured from the tumor surface to the deepest point of invasion 11.

Several studies have compared the performance of TT and DOI in OSCC and OTSCC with inconsistent results. Although some have claimed superior performance of DOI over TT in predicting nodal metastasis and survival 6, 12, 13; others found that both measurements were highly correlated and carried identical prognostic significance 14, 15.

In the past several years, we have encountered many situations in our daily practices where DOI assessment (as proposed by AJCC 8th edition) was problematic and difficult. In contrast, we found TT to be a straight forward and consistent measurement. In this study, a meticulous pathology review was undertaken to measure DOI and TT using AJCC definitions in a retrospective cohort of 293 patients with OTSCC with a tumor greatest dimension of ≤4 cm (i.e. AJCC 7th edition pT1 or pT2). The aims of this study are three fold: 1) to illustrate the problematic pathologic scenarios related to DOI measurement using AJCC 8th edition; 2) to compare DOI with TT and assess their individual prognostic significance; and 3) to assess the impact of including DOI and TT into AJCC pT category and evaluate the prognostic values of pT categories in both AJCC 7th and 8th editions.

Materials and Methods

Study cohort

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval, the surgical departmental database was searched for patients who fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: 1) patients underwent primary resection at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, NY, USA) from 2000 to 2012; 2) a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue; 3) the slides of primary resection were available for review; and 3) a pathologic staging of T1 or T2 using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) cancer staging manual 7th edition 3. Exclusion criteria were 1) synchronous head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, 2) prior treatment of the reference carcinoma, 3) distant metastasis at presentation, 4) prior history of non-endocrine head and neck cancer and 5) depth of invasion (DOI) as defined by AJCC 8th edition could not be measured (n=5) as no normal mucosa was identified in the entire specimen. A total of 293 patients were included in this retrospective study.

Pathologic review

A detailed pathologic review was conducted by three Head and Neck attending pathologists (RG, NK or BX). The following parameters were recorded for each case: 1) TT: defined as proposed by AJCC 7th edition from the surface epithelium or the surface of the tumor to the deepest point of invasion (Figure 1) 3; 2) DOI measured from the basement membrane of adjacent normal squamous mucosa to the deepest point of invasion (Figure 1) 2; 3) other pathologic parameters, e.g. tumor greatest dimension, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, margin status, pathologic nodal staging at the initial resection and extranodal extension. Additionally, all tumors were sub-classified into the following three categories: 1) ulcerated: if the tumor had an ulcerated surface (Figure 1B); 2) exophytic: if the tumor showed exophytic growth (Figures 1C); and 3) neither: if the tumor contained neither features.

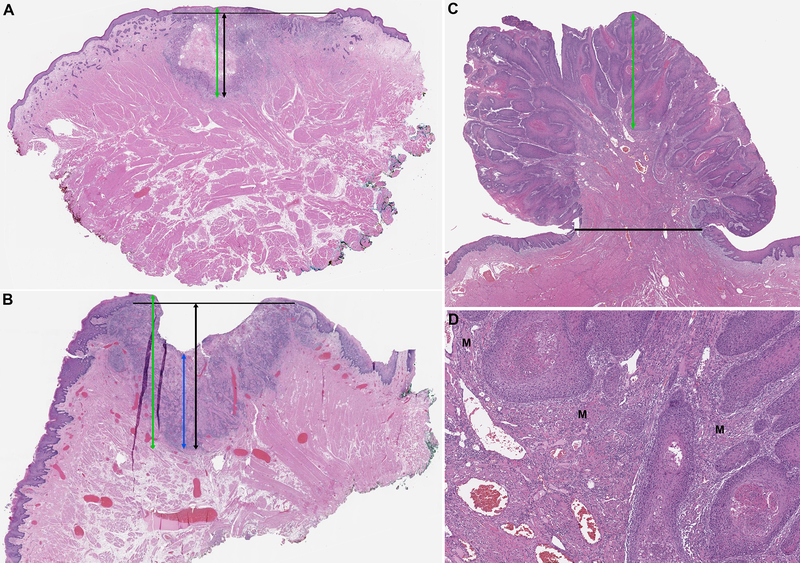

Figure 1. Definition of tumor thickness (TT) and depth of invasion (DOI) using AJCC staging manual 7th and 8th editions 2, 3 in tumor with a flat surface (A), an ulcerated endophytic surface (B), and a polypoid/exophytic architecture (C and D).

TT (green line) is measured from the surface of the tumor to the deepest point of invasion. In ulcerated tumor, an alternative definition of TT (blue line) measuring TT from ulcer bed to deepest point of invasion is also proposed by AJCC 7th edition. DOI (black lines) is measured from an imaginary line connecting the basement membrane of normal squamous mucosa on both sides of the tumors perpendicularly to the deepest point of invasion. In panel C: the DOI is 0 mm as the tumor is entirely exophytic. However, high power view shown in panel D clearly demonstrates invasion of the carcinoma into skeletal muscle (M). In scenarios A and B, TT is slightly greater than DOI. The alternative measurement of TT is much less than DOI in ulcerated lesions. In exophytic lesions, TT is much greater than DOI.

The pT stage was determined using AJCC 7th and AJCC 8th staging manual 2, 3. The pN stage was defined as pNx when neck dissection was not performed, pN0 when all resected lymph nodes showed no evidence of metastasis, and pN+ when one or more lymph nodes contained metastatic squamous cell carcinoma.

Clinical review and statistical analysis

Basic demographic data, treatment detail, and outcomes where extracted from an existing database on OSCC. All statistics were performed using SPSS software v25.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, U.S.) or SAS software (SAS institute, Cary, NC, U.S.)

Overall survival (OS) was the primary endpoint of this study. The prognostic values of tumor size, tumor thickness, DOI, AJCC 7th and 8th edition pT stage were determined using univariate Cox proportional hazard model. Kaplan Meier curves were plotted. Hazard ratio (HR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. Subsequent multivariate analysis was performed to adjust DOI, thickness or AJCC pT stages with other known prognostic factors e.g. age, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, margin status, nodal status and extranodal extension using Cox proportional models.

The risk of nodal metastasis at the time of initial resection was analyzed as a secondary outcome. The correlation between nodal metastasis and various pathologic parameters, including tumor size, DOI, tumor thickness, AJCC pT staging, perineural invasion, and margin status were calculated using univariate logistic regression model. Parameters that were significant on univariate analysis were subjected to the multivariate logistic regression model. Odds ratio (OR) and its 95% CI were calculated. P values less than 0.05 were considered as significant. Additionally, Pearson correlation was used to correlate tumor thickness with DOI.

Results

Obstacles in measuring DOI and TT for OTSCC

During the process of reviewing the histologic slides, the pathologists encountered several situations where the application of the AJCC criteria for TT and DOI was difficult and problematic.

The measurements of TT were straight forward in most cases with the only exception of ulcerated lesions (Figure 1B) as two different definitions were provided by the AJCC 7th edition: one recommends measuring TT from the surface of the most lateral extent of tumor to the deepest point of invasion; the other measures TT from the ulcer base to the deepest point of invasion. As AJCC 7th edition did not specifically state which of the 2 methods was the most preferable, both methods of TT were utilized.

In contrast, a number of challenges have been documented when evaluating DOI, predominantly as a result of plotting an imaginary horizontal straight line “that is at the level of basement membrane related to the closest intact squamous mucosa” 2, 16.

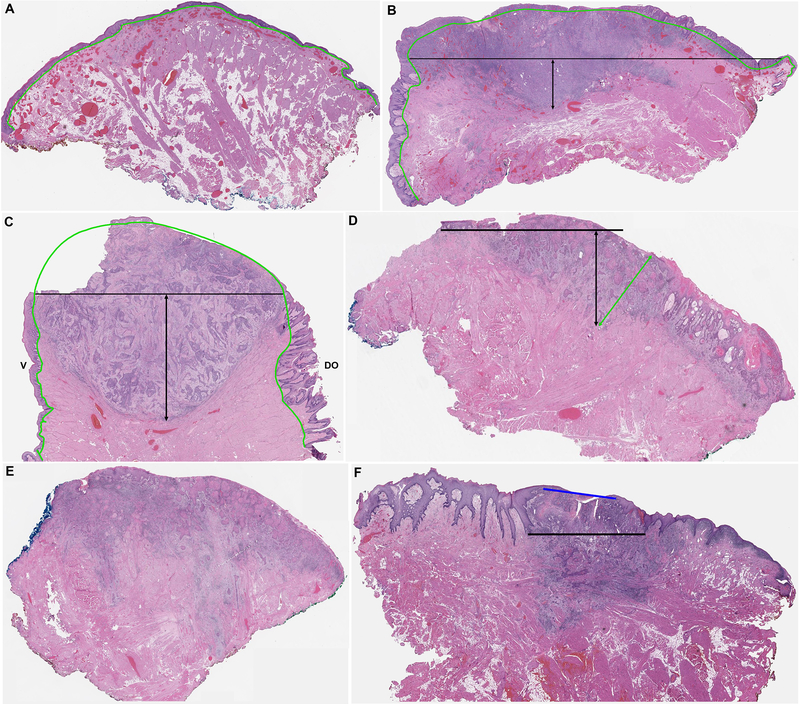

First and foremost, the oral tongue mucosa is curved (convex) rather than a straight line (Figure 2A). In large tumors (e.g. with a greatest dimension of > 2 cm), the imaginary straight line to connect basement membrane of adjacent normal mucosa from both sides of the tumor resulted in significant underestimate of the actual depth of invasion given the convex nature of the oral tongue surface (Figures 2B and 2C).

Figure 2. Pathologic challenges in measuring depth of invasion (DOI) in oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma.

(A) The normal tongue mucosa has a curved (convex) surface with a wavy and curved basement membrane (green contour). (B-C) and DOI measured perpendicularly from the imaginary straight line connecting the basement membrane of the rete of adjacent normal squamous mucosa (black lines) results in marked underestimation of the actual DOI for a lateral tongue tumor (B) and an anterior tongue tumor (C). Note the elongated retes of papillae of the dorsum of the tongue (DO) compared to the rete of the ventral tongue (V). (D) A carcinoma with normal mucosa limited to one side of the tumor. The other side does not contain normal mucosa due to positive surgical resection margin. DOI measured perpendicularly from the straight line of basement membrane of normal mucosa results in an oblique measurement (black lines). Green line: tumor thickness measured perpendicular to the tumor surface. (E) DOI cannot be measured in this tumor as there is no adjacent normal mucosa within the section. (F) The adjacent normal squamous mucosa has elongated rete ridges. Measuring DOI from the very end of the rete as defined by AJCC 8th edition disregards the invasive carcinoma located between the upper boundary (blue line) and lower boundary (black line) of basement membrane.

Second, the tumor block with deepest point of invasion frequently contained only normal mucosa at one side of the tumor (Figure 2D); or did not contain any normal mucosa, especially for larger tumors (Figure 2E). These situations were related either to positive peripheral surgical resection margins at one end, or limitation of tissue size during tissue prosection. A paraffin block maximally holds a tissue section of ≤2cm in size. As a result, a large tumor is often transected or trimmed at the time of prosection to obtain the appropriate size for processing and staining. As illustrated in Figure 2D, an imaginary horizontal line along the basement membrane of the mucosa that existed only on one side of the tumor resulted in oblique and inaccurate measurement of the DOI, compared with TT which is always measured perpendicularly from the surface. Additionally, DOI using the adjuvant normal mucosa for reference would not seem representative if the deepest (thickest) part of the tumor might not be included in the same cassette with normal adjacent mucosa.

Third, the absence of any normal adjacent mucosa in the block precluded the measurement of DOI. Five cases were excluded from the current study because DOI could not be measured as the entire background mucosa showed either dysplasia or verrucous hyperplasia.

Fourth, the mucosa of oral tongue contains papillae and taste buds, and may show hyperplastic changes. As a result, the rete might be markedly elongated to an extent of 1 to 2 mm. In such situation, DOI measured from the very end of rete as defined by AJCC 8th edition disregarded 1 to 2 mm of invasive carcinoma that existed between the upper limit and lower limit of the rete basement membrane (Figure 2F).

Lastly, in an exophytic/polypoid lesion with obvious invasion into the lamina propria or skeletal muscle, DOI may results in a measure of 0. In this particular scenario, TT is obviously a more accurate measurement to reflect the invasive nature of the lesion compared with DOI (Figures 1C and 1D).

Realizing the limitations of DOI as defined by AJCC 8th edition, for this study we had modified the criteria of DOI from an imaginary horizontal straight line from adjacent basement membrane to an imaginary straight or curved line along the basement membrane of rete to account for the curvature of oral tongue in this study.

Correlation between TT and DOI

Among the cases studied, the median TT was 5.5 mm (range: 0.3 to 30.0), and the median DOI was 4.8 mm (range 0.0 to 30.0). The median difference between TT and DOI is 0.5 mm (range −6.0 to 5.0 mm). Twenty-seven cases (9%) had identical TT and DOI, whereas 199 tumors (68%) showed a difference between −1 to 1 mm. A total of 67 cases showed a difference between DOI and TT of more than 1 mm, including 64 cases with a TT value larger than DOI, and 3 cases with a TT value less than DOI.

Thirteen tumors (4.4%) were classified as exophytic, 78 (26.6%) were ulcerated, and the remaining 203 (68.9%) contained neither features. Among the 78 ulcerated lesions, the ulceration was superficial and/or focal with no impacts on TT in 74 (95%) of cases. In 4 (5%) cases, the ulceration had an impact on the measurement of TT. The difference between TT measured from the surface of the ulcer edge (green line in figure 1B) and TT measured from the ulcer base (blue line in figure 1B) was 6 mm, 3 mm, 1.6 mm, and 0.8 mm respectively. All 13 exophytic tumors had a TT greater than DOI.

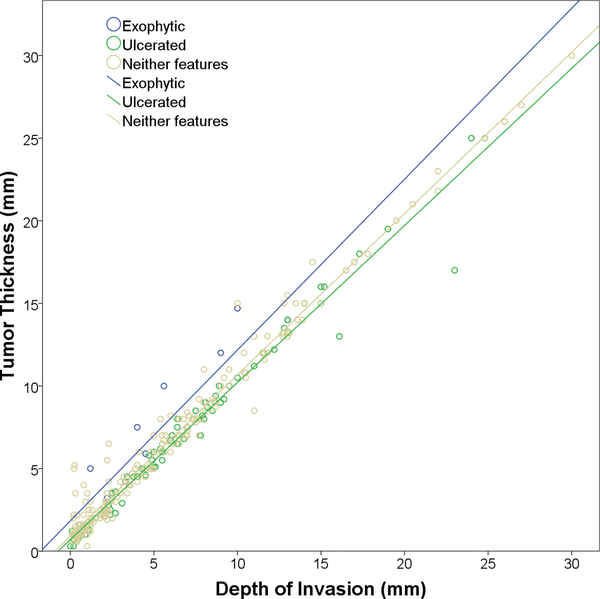

There was a strong positive correlation between TT and DOI in the entire cohort (Pearson correlation coefficient r=0.984), as well as in the subgroups of tumors with exophytic (r=0.930), ulcerated (r=0.986), and neither feature (r=0.987, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Correlation between tumor thickness and depth of invasion.

When using the cutoff of DOI proposed by AJCC 8th edition, being ≤5 mm, 5.1 to 10 mm, and >10 mm, 271 cases (92%) showed a TT and a DOI of the same category, whereas 23 cases (8%) had discordant results. Among them, 22 cases demonstrated an increased TT compared with DOI and a single case had a TT smaller than DOI.

The impact of DOI and TT on AJCC pT staging and/or prognosis

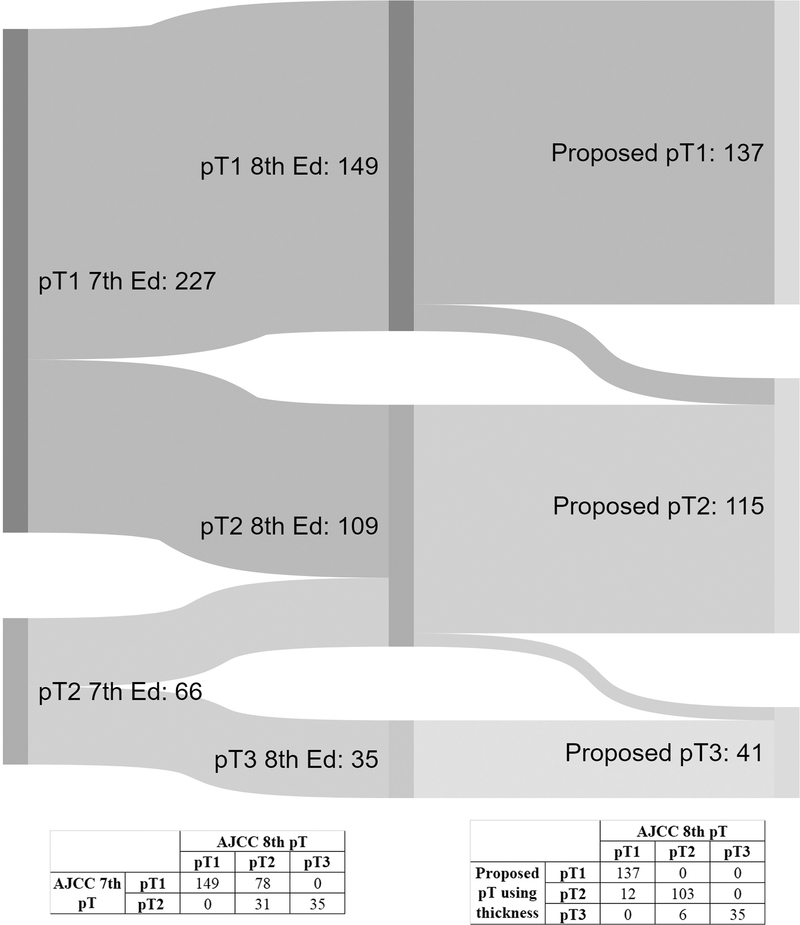

Based on the strong correlation between TT and DOI, we studied a proposed pT staging system using TT instead of DOI. All other staging parameters remained the same as AJCC 8th edition. The number of patients staged using AJCC 7th edition, AJCC 8th edition, and the proposed pT staging system are shown using an Alluvial flow plot in Figure 4. Within the study cohort, 113 patients (39%) were upstaged using AJCC 8th edition compared with 7th edition, including 78 upstaged from pT1 to pT2 and 35 upstaged from pT2 to pT3.

Figure 4.

Staging of the study cohort using AJCC 7th, AJCC 8th and proposed pT categories, Alluvial flow diagram 33.

When comparing the proposed staging with AJCC 8th edition, the pT category remained unchanged in 275 cases (94%). Only 18 patients (6%) were upstaged using the proposed pT categories, including 12 cases upstaged from pT1 to pT2 and 6 upstaged from pT2 to pT3.

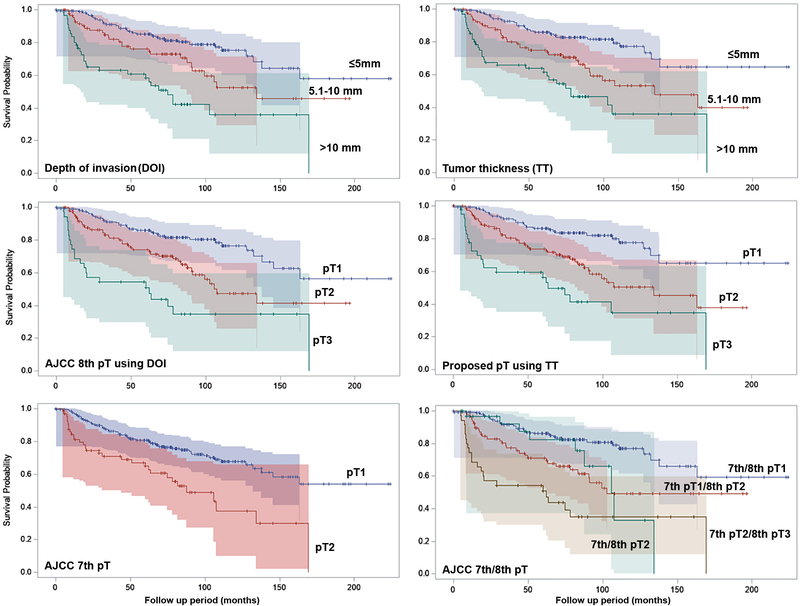

The median follow up period of the study cohort was 59.2 months (interquartile Range IQR = 21.3–91.5 months). TT, DOI, AJCC 7th pT, AJCC 8th pT and the proposed pT categories were significant predictors for OS on univariate analysis. Hazard ratio (HR), 95% confidence interval (CI) and Kaplan Meier curves are shown in Table 1 and Figure 5. The 3-year, 5-year, and 10-year OS are provided in supplementary Table 1. Overall, TT and DOI showed similar performance in predicting OS.

Table 1.

Prognostic significance of tumor thickness (TT), depth of invasion (DOI), AJCC 7th pT, AJCC 8th pT, and proposed pT categories.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| TT | ||||

| ≤5mm | Reference | ND | ||

| 5.1–10mm | 2.132 (1.092 – 4.164) | 0.004 | ||

| >10mm | 3.973 (2.010 –7.855) | <0.001 | ||

| DOI | ||||

| ≤5mm | Reference | ND | ||

| 5.1–10mm | 1.810 (0.933 –3.510) | 0.021 | ||

| >10mm | 3.854 (2.004 –7.411) | <0.001 | ||

| AJCC 7th edition pT | ||||

| pT1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| pT2 | 2.433 (1.373 – 4.313) | <0.001 | 1.609 (0.854 – 3.032) | 0.053 |

| AJCC 8th edition pT | ||||

| pT1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| pT2 | 2.185 (1.167 –4.090) | 0.001 | 1.583 (0.786 – 3.185) | 0.091 |

| pT3 | 4.842 (2.344 –10.003) | <0.001 | 3.017 (1.232 – 7.389) | 0.002 |

| Proposed pT using TT | ||||

| pT1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| pT2 | 2.309 (1.213 –4.397) | <0.001 | 1.670 (0.833 – 3.350) | 0.058 |

| pT3 | 4.601 (2.196 – 9.643) | <0.001 | 2.612 (1.071 – 6.369) | 0.006 |

HR: hazard ratio, CI: confidence interval, ND: not done.

Figure 5.

Kaplan Meier curves for overall survival. Shaded areas represent 95% Hall-Wellner Bands.

When adjusted for age, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, margin status, lymph node status and extranodal extension using multivariate Cox proportional hazard model, AJCC 8th edition and the proposed pT categories using TT remained as independent prognostic factors when comparing T3 with T1, whereas pT stage defined using AJCC 7th edition based on tumor greatest dimension alone failed to reach statistical significance (Table 1). The HR of AJCC 8th edition pT2 and pT3 compared with pT1 were 1.583 (95% CI: 0.786 – 3.185) and 3.017 (95% CI: 1.232 – 7.389) respectively, whereas the HR of the proposed pT2 and pT3 using TT were 1.670 (95% CI: 0.833–3.350) and 2.612 (95% CI: 1.071 – 6.369) respectively.

Exophytic growth did not impact OS on univariate and multivariate analyses (univariate analysis: p=0.281, multivariate analysis: p=0.410). Ulceration was an independent prognostic factor for OS on multivariate analysis when adjusted for age, nodal status, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion and margin status (hazard ratio=1.942, 95% confidence interval 1.236–3.051, p=0.004).

The impacts of various pathologic parameters on the risk of nodal metastasis at initial resection

The clinico-pathologic characteristics of the study cohort substratified by pathologic lymph node stage at the time of initial resection are shown in Table 2. Univariable logistic regression analysis shows that pathology-confirmed nodal metastasis was significantly associated with the following pathologic characteristics: TT, DOI, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, AJCC 7th pT (based solely on tumor size), AJCC 8th pT and the proposed pT stage (p<0.001). Exophytic growth or ulceration did not impact the risk of nodal metastasis (p>0.05). Multivariable logistic regression showed that both TT and DOI were independently associated with the risk of nodal metastasis with similar OR (TT: OR=1.121, 95% CI 1.044–1.204, p=0.002; DOI: OR=1.126, 95% CI 1.052–1.204, p=0.001; Table 3).

Table 2.

Clinico-pathologic characteristics of the study cohort substratified using lymph node status.

| All (n=293) | pN0/pNx (n=243) | pN+ (n=50) (a) | P value (b) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age, median (range) | 57 (18–96) | 57 (18–96) | 58 (24–84) | 0.725 |

| Maximal TT | <0.001 | |||

| ≤5 mm | 140 | 135 (96%) | 5 (4%) | |

| 5.1–10 mm | 92 | 74 (80%) | 18 (20%) | |

| >10 mm | 61 | 34 (56%) | 27 (44%) | |

| DOI | <0.001 | |||

| ≤5 mm | 154 | 149 (97%) | 5 (3%) | |

| 5.1–10 mm | 84 | 65 (77%) | 19 (23%) | |

| >10 mm | 55 | 29 (53%) | 26 (47%) | |

| AJCC 7th pT | <0.001 | |||

| pT1 (tumor size≤2 cm) | 227 | 204 (90%) | 23 (10%) | |

| pT2 (tumor size 2.1 – 4 cm) | 66 | 39 (59%) | 27 (41%) | |

| AJCC 8th pT | <0.001 | |||

| pT1 | 149 | 144 (97%) | 5 (3%) | |

| pT2 | 109 | 85 (78%) | 24 (22%) | |

| pT3 | 35 | 14 (40%) | 21 (60%) | |

| Proposed pT using thickness (c) | <0.001 | |||

| pT1 | 137 | 132 (96%) | 5 (4%) | |

| pT2 | 115 | 92 (80%) | 23 (20%) | |

| pT3 | 41 | 19 (46%) | 22 (54%) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | <0.001 | |||

| Absent | 264 | 227 (86%) | 37 (14%) | |

| Present | 29 | 16 (55%) | 13 (45%) | |

| Perineural invasion | <0.001 | |||

| Absent | 220 | 197 (90%) | 23 (10%) | |

| Present | 73 | 46 (63%) | 27 (37%) | |

| Margin status | 1.000 | |||

| Absent | 287 | 238 (83%) | 49 (17%) | |

| Present | 6 | 5 (83%) | 1 (17%) | |

All values are expressed as N (row percentage) unless otherwise specified.

pN+ is defined as metastatic carcinoma in one or more lymph nodes at the time of primary resection.

P values are obtained using univariate logistic regression model.

The proposed pT stage is derived using TT rather than DOI. All other staging parameters are the same as AJCC 8th pT stage.

Table 3.

Multivariable log regression model for nodal metastasis.

| OR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariable logistic regression with tumor thickness (TT) | |||

| Margin status | 2.256 | 0.238–21.337 | 0.478 |

| Perineural invasion | 2.484 | 1.196–5.160 | 0.015 |

| AJCC 7th edition pT stage | 2.087 | 0.904–4.816 | 0.085 |

| Thickness (as continuous variable) | 1.121 | 1.044–1.204 | 0.002 |

| Multivariable logistic regression with depth of invasion (DOI) | |||

| Margin status | 2.110 | 0.212–21.023 | 0.525 |

| Perineural invasion | 2.487 | 1.201–5.149 | 0.014 |

| AJCC 7th edition pT stage | 2.098 | 0.929–4.739 | 0.075 |

| DOI (as continuous variable) | 1.126 | 1.052–1.204 | 0.001 |

OR: odds ratio, 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

The AJCC 8th edition published in 2017 has included DOI in the pathologic T staging of OSCC 2. Soon thereafter, DOI was incorporated into major pathology 17, 18 and clinical management guidelines 19, and has become a mandatory reporting element in the pathology report of OSCC. For example, the current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines strongly recommend elective neck dissection for an OSCC with a DOI greater than 4 mm 19, as multiple studies have shown an association between DOI and risk of neck metastasis 6, 13, 14, 20–24.

Prior to the publication of AJCC 8th edition, TT and DOI were often used interchangeably in research articles, and most did not include a clear definition of either parameter. Despite the lack of a clear distinction and definition, both TT and DOI were shown to significantly correlate with rate of neck metastasis, local recurrence, regional recurrence, OS, and DSS 4–9, 25, 26. The decision to include DOI rather than TT in the AJCC pT stage was largely based on a large-scale multi-center retrospective study of 3149 OTCC patients demonstrating the independent prognostic value of DOI in predictor DSS 24.

After DOI was included in the AJCC pT staging, most recent studies for OSCC and OTSCC have incorporated clear definitions of DOI and TT using the criteria proposed by the AJCC 12, 13, 15, 20–22, 27, 28. However, studies which have confused these two measurements 11 or did not provide a definition 14, 27, 29–31 continued to be reported in the literature. Additionally, a recent survey of 159 surgeons has shown that 18% of survey participants confused the definition of DOI with TT 10.

Several studies have compared the prognostic values of TT and DOI directly, and reported conflicting results: while two retrospective studies with a cohort size of 95 T1/2N0 OSCC patients 12 and 336 cT1/T2N0M0 OSCC patients 13 reported superior performance of DOI compared to TT in predicting nodal metastasis 15 and disease free survival 12, two other studies with a cohort size of 456 OSCC (any T, any N) 15 and 109 T1/T2 OTSCC 14 demonstrated high correlation and identical performance of DOI and TT in predicting nodal metastasis 14, OS15, and DSS 15.

Recently, Kukreja et al. 12 reported the challenges faced by pathologists when measuring DOI using the AJCC 8th definition. The authors stated that DOI could not be measured in 52 out of 95 tumors (55%) in their study due to a variety of reasons. The most common ones were the presence of adjacent mucosa on only one side of the tumor only limiting assessment of the horizon in 32 cases (44%), rounded/arcuate horizon in 26 (29%), distance between benign mucosa and tumor in 15 (21%), and absence of adjacent mucosa in 18 (20%).

Our study further supports these findings. As illustrated in the results section and in Figures 1 and 2, there are several major obstacles in accurately and consistently measuring DOI as currently defined by the AJCC 8th edition. First, the oral tongue has a curved natural surface: drawing an arbitrary straight line from the basement membrane of adjacent normal squamous epithelium may significantly underestimate the actual DOI, especially when the tumor is large and/or when the normal mucosa is farther apart from the tumor intervened by dysplastic mucosa. Second, there are cases in which normal squamous mucosa is not present in the blocks with the deepest level of invasion or in the entire specimen (e.g. when the background mucosa shows diffuse dysplastic changes). Lastly, in an exophytic/polypoid lesion with obvious invasion into the lamina propria or skeletal muscle, DOI may result in a measurement of 0. In this particular scenario, TT is obviously a more accurate measurement to reflect the invasive nature of the lesion compared with DOI.

Interestingly enough, despite the fact that 55% (52/95) of the study cohort were found to have identical DOI and TT, Kukjera et al. reported that DOI but not TT was associated with risk of nodal metastasis 12. In contrast, using a larger cohort of 293 patients of OTSCC with a tumor size of 4 cm or less (i.e. AJCC 7th edition T1/T2), we have found that DOI and TT are nearly perfectly correlated and both factors predict nodal metastasis and OS identically. Our data is consistent with what has been previously reported by Dirven et al. 15 and Liu et al. 14. Both groups also reported high correlation and same prognostic power of TT and DOI. Together, these data suggest that TT could be used as an alternative parameter for pT staging. Compared to DOI, TT is a simpler and a more consistent measurement; as it does not require identification of adjacent normal mucosa or drawing of an imaginary horizon. The upstage rate using TT compared with DOI was small, being 6% (18/293) in our cohort, and 5.5% (25/456) in a cohort of 456 oral SCC 15. None of the patients were downstaged in our cohort, whereas one patient (0.3%) was downstaged in Dirven et al. from T2 to T1. The percentage of cases with a difference between TT and DOI of ≤ 1 mm was 77% in Dirven et al. 15, and 68% in our study. Both studies show that the performance of pT staging to predict OS was equivalent using either DOI or TT 15.

Taken all evidences together, we propose the following changes in regard to the measurement and staging of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Given the near identical prognostic significance of TT and DOI and the feasibility of measuring TT compared with DOI, we propose to use TT instead of DOI in the T staging. If DOI remains as a staging-determining factor, we propose DOI to be measured from an imaginary straight or curved line along the basement membrane of adjacent squamous mucosa. Similar to what we proposed, Berdugo et al. also suggested adjust the measurement of DOI to accommodate the curved surface of oral tongue in a recent study 32. We also suggest using TT as an additional parameter for staging when DOI cannot be measured.

One potential weakness of the study is that we only included T1/T2 (defined using AJCC 7th edition) OTSCC. Therefore, the results may not be generalized to more advanced OTSCC or OSCC originated from a primary site other than oral tongue.

Since the publication of AJCC 8th, two retrospective studies have investigated the rate of upstaging using AJCC 8th edition compared with AJCC 7th edition 15, 28. Dirven et al. reported an upstage rate of 34% (102/298) in T1/T2 OSCC; whereas Sridharan et al. reported an upstage rate of 38% 28. The stage-specific upstage rate was 27% and 39% for AJCC 7th pT1, and 40% and 35% for pT2 tumors. The upstage rate in our cohort was similar, being 39% in the entire cohort, 34% in AJCC pT1 and 53% for pT2 tumors. Clearly, incorporation of DOI into the pT stage results in a large rate of upstaging. Therefore, it is important to determine whether the AJCC 8th pT stage performs superiorly compared with AJCC 7th pT stage to justify the high upstage rate. Recently, using local recurrence and locoregional recurrence as the primary outcomes, Sridharan et al. reported that AJCC 8th pT stage did not improve prognostication compared with AJCC 7th edition in 494 AJCC 7th pT1/T2 N0 OTSCC patients 28. In contrast, we report that AJCC 8th pT stage is an independent predictor for OS, while AJCC 7th pT staging failed to reach statistical significance on multivariate analysis. The group of patients upstaged from AJCC 7th pT1 to AJCC 8th pT2 showed a decreased survival compared with those remaining as pT1. These discrepant results may be explained in part by several major differences between the two studies. First, our study included node positive patients; whereas Sridharan et al. only studied pN0 patients. Second, our primary outcome was OS, while Sridharan et al. studied local and locoregional recurrence. Lastly, the present study was a unicenter study allowing more uniformity of patient population, compared with the international multicenter study of Sridharan et al. Both studies included expert pathology review to accurately determine DOI and other pathologic parameters. Additional future large-scale studies including pathology review to carefully evaluate DOI are needed to further elucidate the performance of AJCC 8th edition compared with 7th edition.

In conclusion, we illustrate in detail multiple practical challenges pathologists encounter when measuring DOI compared with TT. We have shown that TT and DOI are nearly perfectly correlated, and a proposed pT stage using TT instead of DOI performed identically as the AJCC 8th edition using DOI in prognostication for lymph node metastasis and survival. We therefore propose to use TT, a straight-forward and reliable histologic measurement, in assessing the pT stage for OSCC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Cancer Center Support Grant of the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute under award number P30CA008748. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additionally, CV reports receiving a research grant from Fundación Alfonso Martín Escudero.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: No competing financial interests exist for all contributory authors. No competing financial interests exist for all contributory authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bray F, Colombet M, Mery L et al. Cancer incidence in five continents, vol. Xi, iarc cancerbase no. 14: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amin MB, Edge SB, GF L et al. Ajcc cancer staging manual. Eighth edition. New York: Springer Nature, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Torotti A. Ajcc cancer staging manual. Seventh edition. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spiro RH, Huvos AG, Wong GY, Spiro JD, Gnecco CA, Strong EW. Predictive value of tumor thickness in squamous carcinoma confined to the tongue and floor of the mouth. Am J Surg 1986;152;345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang SH, Hwang D, Lockwood G, Goldstein DP, O’Sullivan B. Predictive value of tumor thickness for cervical lymph-node involvement in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity: A meta-analysis of reported studies. Cancer 2009;115;1489–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pentenero M, Gandolfo S, Carrozzo M. Importance of tumor thickness and depth of invasion in nodal involvement and prognosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma: A review of the literature. Head & neck 2005;27;1080–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durr ML, van Zante A, Li D, Kezirian EJ, Wang SJ. Oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma in never-smokers: Analysis of clinicopathologic characteristics and survival. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 2013;149;89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ling W, Mijiti A, Moming A. Survival pattern and prognostic factors of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue: A retrospective analysis of 210 cases. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons 2013;71;775–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almangush A, Bello IO, Keski-Santti H et al. Depth of invasion, tumor budding, and worst pattern of invasion: Prognostic indicators in early-stage oral tongue cancer. Head & neck 2014;36;811–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bulbul MG, Zenga J, Puram SV, Tarabichi O, Parikh AS, Varvares MA. Understanding approaches to measurement and impact of depth of invasion of oral cavity cancers: A survey of american head and neck society membership. Oral Oncol 2019;99;104461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mann J, Julie D, Mahase SS et al. Elective neck dissection, but not adjuvant radiation therapy, improves survival in stage i and ii oral tongue cancer with depth of invasion >4 mm. Cureus 2019;11;e6288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kukreja P, Parekh D, Roy P. Practical challenges in measurement of depth of invasion in oral squamous cell carcinoma: Pictographical documentation to improve consistency of reporting per the ajcc 8th edition recommendations. Head Neck Pathol 2020;14;419–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arora A, Husain N, Bansal A et al. Development of a new outcome prediction model in early-stage squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity based on histopathologic parameters with multivariate analysis: The aditi-nuzhat lymph-node prediction score (anlps) system. Am J Surg Pathol 2017;41;950–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu B, Amaratunga R, Veness M et al. Tumor depth of invasion versus tumor thickness in guiding regional nodal treatment in early oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2020;129;45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dirven R, Ebrahimi A, Moeckelmann N, Palme CE, Gupta R, Clark J. Tumor thickness versus depth of invasion - analysis of the 8th edition american joint committee on cancer staging for oral cancer. Oral Oncol 2017;74;30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lydiatt WM, Patel SG, O’Sullivan B et al. Head and neck cancers-major changes in the american joint committee on cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2017;67;122–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seethala RR, Weinreb I, BM J et al. College of american pathologist (cap) protocol for the examination of specimens for patients with cancers of the lip and oral cavity. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Müller S, Boy SC, Day TA et al. Data set for the reporting of oral cavity carcinomas: Explanations and recommendations of the guidelines from the international collaboration of cancer reporting. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2019;143;439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahoo A, Panda S, Mohanty N et al. Perinerural, lymphovascular and depths of invasion in extrapolating nodal metastasis in oral cancer. Clinical oral investigations 2020;24;747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tam S, Amit M, Zafereo M, Bell D, Weber RS. Depth of invasion as a predictor of nodal disease and survival in patients with oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Head & neck 2019;41;177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faisal M, Abu Bakar M, Sarwar A et al. Depth of invasion (doi) as a predictor of cervical nodal metastasis and local recurrence in early stage squamous cell carcinoma of oral tongue (esscot). PLoS One 2018;13;e0202632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larson AR, Kemmer J, Formeister E et al. Beyond depth of invasion: Adverse pathologic tumor features in early oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope 2020;130;1715–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mucke T, Kanatas A, Ritschl LM et al. Tumor thickness and risk of lymph node metastasis in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Oral Oncol 2016;53;80–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ebrahimi A, Gil Z, Amit M et al. Primary tumor staging for oral cancer and a proposed modification incorporating depth of invasion: An international multicenter retrospective study. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery 2014;140;1138–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asakage T, Yokose T, Mukai K et al. Tumor thickness predicts cervical metastasis in patients with stage i/ii carcinoma of the tongue. Cancer 1998;82;1443–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tai SK, Li WY, Chu PY et al. Risks and clinical implications of perineural invasion in t1–2 oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Head & neck 2012;34;994–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang B, He W, Ouyang H et al. A prognostic nomogram incorporating depth of tumor invasion to predict long-term overall survival for tongue squamous cell carcinoma with r0 resection. J Cancer 2018;9;2107–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sridharan S, Thompson LDR, Purgina B et al. Early squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue with histologically benign lymph nodes: A model predicting local control and vetting of the eighth edition of the american joint committee on cancer pathologic t stage. Cancer 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin SJ, Gurary EB, Qureshi MM et al. Stage ii oral tongue cancer: Survival impact of adjuvant radiation based on depth of invasion. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 2019;160;77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu K, Wei J, Liu Z et al. Can pattern and depth of invasion predict lymph node relapse and prognosis in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2019;19;714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shin JH, Yoon HJ, Kim SM, Lee JH, Myoung H. Analyzing the factors that influence occult metastasis in oral tongue cancer. Journal of the Korean Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons 2020;46;99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berdugo J, Thompson LDR, Purgina B et al. Measuring depth of invasion in early squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue: Positive deep margin, extratumoral perineural invasion, and other challenges. Head Neck Pathol 2019;13;154–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.SankeyMATIC. Alluvial diagram. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.