Abstract

Introduction and purpose

Empyema thoracis (ET) is defined as the accumulation of pus in the pleural cavity. Early stages of ET are treated medically and the late stages surgically. Decortication, thoracoplasty, window procedure (Eloesser flap procedure) and rib resections are the open surgical procedures executed. There are no strict guidelines available in developing nations to guide surgical decision-making, as to which procedure is to be followed.

Methods

Details of all adult patients treated surgically for ET, between the years 2009 and 2019, and maintained in a live database in our institute, were retrieved and analysed. Medically managed patients were excluded.

Results

There were 437 patients in the study. The average age was 38 years. There was right side preponderance with a male:female ratio of 5:1. Tuberculosis was the commonest aetiology identified in 248 (57%) patients and diabetes was the commonest co-morbidity present in 97 (22%) patients. There was a higher incidence of a window procedure (WP) in tubercular patients 145 (59%). Only 26 (14%) of the non-tubercular patients underwent a WP. Post-operative complications were persistent air leak in 12 (6%) patients and premature closure of a window in 7 (4%) patients. There were 4 (0.9%) post-operative mortalities.

Conclusion

Surgical management of late stages of ET provides good results with minimal morbidity and mortality. In developing nations like India, the high incidence of tuberculosis and late presentations make the surgical management difficult and the strategies different from those in developed nations. No clear guidelines exist for the surgical management of ET in developing nations. There is a need for a consensus on the surgical management of empyema in such countries.

Keywords: Empyema, Tuberculosis, Decortication, Thoracoplasty, Window procedure, Rib resection

Introduction

Empyema thoracis (ET) is defined as the collection of pus in the pleural cavity [1]. The commonest cause of ET in developed countries is the infection of a para-pneumonic effusion complicating community-acquired pneumonia [2]. In developing countries like India, however, tuberculosis (TB) is one of the leading causes [3]. The evolution of empyema is in three stages: stage 1, the exudative phase; stage 2, the fibrino-purulent stage; and stage 3, the organising stage [4]. Stages 1 and 2 are managed medically by antibiotics and drainage. The management of stage 3 is essentially surgical. The four open surgical procedures commonly employed in the treatment of ET are (1) decortication, (2) thoracoplasty, (3) window procedure (Eloesser flap) and (4) rib resection.

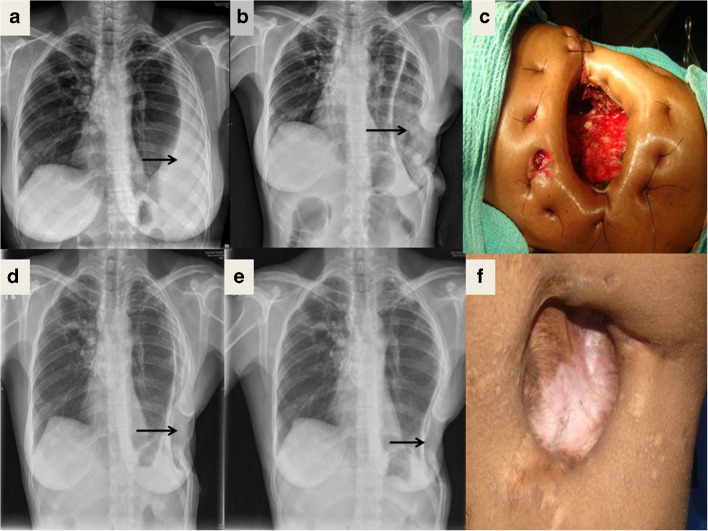

There are no clear guidelines available for the management of ET for countries like India. In an ET requiring surgery, the surgeon makes the decision as to which procedure to employ, based on patient factors, pathology involved, experience and expertise. The surgical management of empyema in a developed nation differs from that in a developing nation in some aspects. The patients in developed nations often present for surgery early in stage 3, with a non-tubercular bacterial aetiology, where a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical (VATS) decortication, wash out and tube drainage are sufficient [5]. In contrast, most Indian patients have TB as the aetiology and they often present late with established sequelae of the improperly or inadequately treated empyema, like severe rib crowding, a highly thickened calcified pleura and empyema necessitans (Fig. 1a, b, c, d). This necessitates a comprehensive surgical approach and VATS is seldom possible.

Fig. 1.

a Late presentation of an empyema with a Malecot catheter in situ. b Sequelae of chronic empyema showing rib crowding, and thickened calcified pleura. c Right empyema extending across the mediastinum into the left side. d Empyema necessitans. e Ruptured hydatid cyst presenting as empyema. f Ruptured anterior mediastinal cyst presenting as empyema

Based on the observation that the details of our large cohort of patients are significantly different from those in other data available in literature, a study was proposed to retrospectively analyse our patient profiles, surgical management and outcomes.

Methodology

The live electronic database of case files of all adult patients who underwent surgery for ET in our institution between 2009 and 2019 was analysed. This study was a retrospective observational study. The approval of the institutional review board was obtained (IRB min no.: 13044 dated 24.06.2020). Written informed consent for study and publication were obtained from the patients prior to the surgery.

Aim of the study

The primary aims of the study were to assess the factors that aided in surgical decision-making and to evaluate the surgical outcomes in ET. The objectives were

To evaluate the characteristics of patients presenting with ET in a developing country.

To assess the etiological and risk factors associated with ET.

To analyse the difference in management and outcomes of TB and non TB ET.

Inclusion criteria

All patients, 12 years of age or more, who presented for surgical management of ET.

Exclusion criteria

Patients less than 12 years of age.

Patients who had medical treatment only, with or without tube drainage.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses of various parameters was done using the Excel worksheet and SPSS version 21 software. All comparative analyses were done by the chi-square test for qualitative variables and Student t test for quantitative variables. A “p” value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Details of management of stage 3 empyema thoracis

Pre-operative workup

On admission, all patients were investigated and evaluated as per protocol, with baseline blood tests, chest radiograph, computerised tomogram (CT) and fibre optic bronchoscopy. The CT helped to characterize the empyema cavity and the condition of the underlying lung, thus helping in deciding the type of surgery to be done. Bronchoscopy was done to rule out intra-bronchial pathology. Most of the patients underwent a trans-bronchial, trans-thoracic or thoracoscopic sampling of the empyema fluid and wall, by the pulmonologists, for microbiological and histopathological studies. A detailed informed consent was obtained from all patients before surgery, explaining the diagnosis and the details of the surgery that was to be performed. The pre-operative management included nutritional build up, cessation of smoking, initiation of appropriate antibiotics or anti-tubercular treatment (ATT), control of diabetes mellitus, blood transfusions, if the haemoglobin level was less than 9 gm%, and treatment of other co-morbidities, if any. Newly diagnosed patients of TB were treated with ATT for a minimum of 6 weeks prior to surgery. Post-operatively, the patients with TB were continued with the ATT course, to completion. The patients with other bacterial infections were treated with appropriate antibiotics for 6 weeks post-operatively.

Criteria to decide the type of surgery

Although at times it was difficult to ascertain pre-operatively the type of surgery to be performed, certain factors helped in the surgical decision-making. Decortication was predominantly done in patients who presented in early stage 3 ET, in patients with non-tubercular aetiology and in patients with minimal or no co-morbidities. Long-standing tubercular ET with CT showing a necrotic lung and thick calcified pleural peel were taken up for a window procedure (WP) electively. This decision to do a WP was further confirmed intra-operatively, when diseased and necrotic lung with multiple irreparable bronchopleural fistulae (BPF) was seen. When a pre-operative decision could not be made on the basis of CT, the patient, by default, was taken up for a decortication and decision for a WP was taken on table. A toxic, catabolic, febrile and septic patient was not considered a candidate for decortication or thoracoplasty, which are major procedures. WP was useful in such patients who required urgent control of sepsis [6]. Most of these decisions were based on clinical judgement. Investigations like leukocyte counts, C-reactive protein and procalcitonin could not be used pedantically to make surgical decisions. Thoracoplasty was usually done simultaneously along with a decortication, to complement it, if the lung expansion was noticed to be insufficient intra-operatively, usually due to chronic pulmonary fibrosis.

Decortication procedure

A complete decortication was done to free the entire lung from all around and to open up the fissures. Sites of air leak were repaired primarily or with a pedicle of pleura or intercostal muscle tissue. Three intercostal drainage tubes (ICD) were placed, two in the conventional positions at the apex and the base of the thoracic cavity and a third one in the retro-sternal space, traversing the sub-pulmonic route. In the post-operative period, a mild suction of 10 cc of water was applied to the ICD. The ICD were removed once the air leaks stopped, drainage had become minimal and serous (< 50 ml/day) and the lungs had expanded satisfactorily. Intra-operatively, if the lung was noticed to be fibrosed, small and not expanding fully post-operatively, the tubes were kept in place on suction for 21 days, to ensure that the residual space was obliterated completely by lung expansion and a strong pleural synechiae between the parietal and visceral pleurae was obtained. Biweekly chest x-rays were done to monitor progress. At the end of the stipulated 3 weeks, the ICD were exposed to air and a chest radiograph repeated. If the lung did not collapse, suggesting adequate pleural synechiae, the patients were discharged with the cut ICD in situ. These tubes were gradually withdrawn about 3 cm every week, over the next few weeks, until complete removal. A small benign residual space was best ignored [7]. If the lung collapsed when the tubes were exposed to air, indicating lack of pleural synechiae, the ICD were connected to an under-water seal bag and the patient discharged to be followed up as an outpatient with planned removal when the objective was achieved. If a significant residual space persists at the end of 3 weeks of suction drainage, with a recurrence of fever or an air-fluid level in the chest x-ray, a WP was performed to drain the residual space.

Thoracoplasty procedure

Segments of various lengths of varying numbers of ribs were resected extra-periostially to collapse the chest wall onto the underlying lung, thus obliterating the residual intra-pleural space (Fig. 2 a, b). Transposed pedicled muscle flaps or omentum was used in patients, where there were multiple or large irreparable BPF or when the collapsed chest wall was not sufficient to obliterate the space. The ICD were managed in the same way as for a decortication. Diligent and intense physiotherapy and adequate pain relief were mandatory post-operatively, since removal of multiple ribs might result in pulmonary complications by impairing chest wall mobility. It also reduced limb girdle mobility and could result in roto-scoliosis (Fig. 2 c, d).

Fig. 2.

a Chest x-ray after a thoracoplasty for a left-sided post-pneumonectomy empyema with BPF. b CT scan of the same patient showing a completely collapsed left chest wall. c Clinical photograph post thoracoplasty, showing the collapse of the chest wall along with the scapula. d Clinical photograph demonstrating the limited mobility of the shoulder

Window procedure

A WP was a drainage procedure, created on the chest wall, over the most anterior and inferior aspect of the empyema space by resecting overlying segments of ribs. The skin edges around the window were tucked into the wound and sutured in, so as to cover the cut bony edges and form a skin lined tract (Fig. 3 c). Windows could be created under local anaesthesia also, for patients who were not fit for general anaesthesia. During the period of hospital stay, the patients were taught to do dressings themselves. Patients were followed up after 6 months and then periodically until the windows closed (Fig. 3 f). Serial follow-up chest radiographs of a patient who underwent WP are shown in Fig. 3a, b, d and e.

Fig. 3.

Stages in treatment by a WP. a X-ray at presentation. b X-ray in the immediate post-operative period. c Clinical photograph of window at creation. d X-ray 3 months after surgery. e X-ray 6 months after surgery. f Clinical photograph of the healed window at 6 months

Rib resection

A simpler drainage procedure, in the form of rib resection, was resorted to in patients with empyema necessitans or in those with a pleuro-cutaneous fistula connecting to a small ET.

Post-operative pain management

Post-operative pain was controlled by intra-operative intercostal and para-vertebral nerve blocks, using 0.5% bupivacaine injection. Due to the presence of infection, epidural anaesthesia was avoided. Post-operatively, a continuous low-dose narcotic infusion or a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) was utilised for 48 h, supplemented by the standard non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and analgesic drugs. Anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesic mediations were continued post-operatively as per the patient’s requirements.

Results

Patient demographics

A total of 437 adult patients who underwent surgical treatment for ET were included in the study. The average age was 38 years with most of the patients, 307 (70%) in the age group between 21 and 50 years. There was a male preponderance, 368 (84.2%) patients. The right side was involved in 243 (55.6%) patients.

Etiological factors and co-morbidities

TB was the most common aetiology seen in 248 (56.75%) patients. The evidence for TB was based on pre-operative Gene Xpert test, smear and culture studies of sputum, pleural fluid, bronchial lavage fluid and the pleural tissue. Histopathology of the pleural tissue was also contributory. Other common aetiologies were infected para-pneumonic effusions (23.3%), trauma (5%) and previous thoracic surgeries (4.8%). Rarer causes included ruptured lung hydatid cysts (11) (Fig. 1e, f), infected malignant effusions (5), infected clotted chylothorax (4), ruptured liver abscesses or cysts (2), fungal infection (2) and ruptured lung abscesses (1) (Table 1). The common co-morbidities were diabetes mellitus (22%), hypoproteinemia (14.8%), smoking (12.35%) and anaemia (12.35%) (Table 2). More than half of the patients (51%) had pleurocentesis or ICD insertions done elsewhere earlier, as an initial management prior to surgery. The comparison of patient characteristics between the TB ET group and the para-pneumonic aetiology group is summarised in Table 3.

Table 1.

Aetiology of ET

| Aetiology | Numbers |

|---|---|

| TB | 248 (57%) |

| Infected para-pneumonic effusion | 102 (23.3%) |

| Trauma | 22 (5%) |

| Failed decortication surgery | 12 (2.7%) |

| Ruptured hydatid cyst | 11 (2.5%) |

| Post lung resections | 8 (1.8%) |

| Iatrogenic causes | 6 (1.4%) |

| Infected malignant effusion | 5 (1.1%) |

| Infected clotted chylothorax | 4 (0.9%) |

| Ruptured liver abscess | 2 (0.4%) |

| Fungal infection | 2 (0.4%) |

| Ruptured lung abscess | 1 (0.2%) |

| Post bullectomy surgery | 1 (0.2%) |

| Others | 13 (3%) |

Table 2.

Co-morbidities associated with ET

| Co-morbidities | Numbers |

|---|---|

| Past drainage procedures | 223 (51%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 97 (22%) |

| Hypoproteinemia | 65 (14.9%) |

| Anaemia | 54 (12.3%) |

| Smoking | 54 (12.3%) |

| Hypertension | 44 (10%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 16 (3.6%) |

| Connective tissue disorder | 6 (1.4%) |

| Haematological disorder | 3 (0.7%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3 (0.7%) |

| Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome | 1 (0.2%) |

Table 3.

Comparison of patient characteristics of the two major groups of patients

| Tuberculous aetiology (248) | Para-pneumonic aetiology (102) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean ± SD) | 33 ± 14.15 | 46 ± 13.75 | 0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 47 (19%) | 44 (43%) | 0.0001 |

| Anaemia | 22 (9%) | 12 (12%) | 0.42 |

| Hypoproteinemia | 24 (10%) | 22 (21.5%) | 0.005 |

| Smoking | 33 (13%) | 18 (17.6%) | 0.31 |

| Leucocytosis | 20 (8%) | 93 (91%) | 0.0001 |

Pre-operative investigations

Pre-operative leucocytosis was present in 117 (26.7%) patients of which 93 (79.5%) patients belonged to the infected para-pneumonic effusion group (Table 3). Pre-operative pleural fluid cultures were done in 350 (80%) patients. The commonest organism detected pre-operatively was Mycobacterium tuberculosis(MTB) in 107 (24.5%) patients, of which 8 were multi-drug-resistant (MDR) TB and 1 was an extensively drug-resistant (XDR) TB. No fungal organism was detected pre-operatively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Peri-operative microbiological analysis

Type of surgery performed

A total of 188 (43%) patients underwent decortication and 171 (39%) patients underwent a WP. A total of 61 (14%) patients had a thoracoplasty done to complement a decortication. A total of 13 (3%) patients had a rib resection for the management of a pleuro-cutaneousfistula or an empyema necessitans. Of the 188 patients that underwent a decortication, 108 (57.4%) had a non-tubercular aetiology and only 80 (42.5%) had TB. Of the 171 patients that underwent a WP, 145 (85%) had TB. Of the 61 thoracoplasties, 23 (38%) had TB, 14 (23%) had a para-pneumonic aetiology, 10 (16%) had post trauma, 6 (10%) had a decortication done elsewhere and the other minor aetiologies include post-pneumonectomy ET and infected clotted chylothoraces. The type of surgery performed in patients, where ET was due to TB and ET with para-pneumonic aetiology, is summarised in Table 4. Four (1%) patients, who were taken up for decortication, had only an ICD placement done after a careful intra-operative assessment.

Table 4.

Comparison of the type of surgery performed and post-operative stay between the two major groups

| Tuberculous aetiology (248) | Para-pneumonic aetiology (102) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decortication | 80 (32%) | 66 (65%) | 0.0001 |

| WP | 145 (58.5%) | 22 (21.5%) | 0.0001 |

| Decortication + thoracoplasty | 23 (9.5%) | 14 (13.5%) | 0.25 |

| Post-operative stay in days (mean ± standard deviation) | |||

| Decortication | 17.2 ± 6.6 | 15.3 ± 6.75 | 0.01 |

| WP | 6.4 ± 6.17 | 6.5 ± 5.9 | 0.9 |

| Decortication + thoracoplasty | 18 ± 7.1 | 18.2 ± 6.1 | 0.8 |

Peri-operative microbiological analysis

No organisms were identified in 151 (35%) patients post-operatively. The most common organism isolated post-operatively was also MTB in 101 (23%) patients. Pseudomonas was isolated in 63 (14%) patients and a mixture of flora was identified in 7% (Fig. 4).

Histopathology findings

The common pathologies observed were chronic pleuritis in 243 (55.6%) patients and necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in 161 (36.8%) patients. There were 5 patients in whom malignancy, undetected pre-operatively, was diagnosed incidentally.

Post-operative complications

Twelve (6%) patients had persistent air leak after decortication. Two of them underwent a WP while the others were managed conservatively with prolonged ICD. Seven (4%) patients had premature stenosis of the os of the window on follow-up, requiring its refashioning. Four (0.9%) patients died in the immediate post-operative period. The mean post-operative stay of the patients of various groups of patients is mentioned in Table 4.

Follow-up

Only 277 (64%) patients were followed up here for an average of 11 months. All windows were allowed to heal by themselves by granulation of the cavity and epithelialisation, but for four patients who requested an early surgical closure of the window. These windows were closed with pedicled musculo-cutanous or by omental transposition with primary skin closure over it. The clinical photographs of two such patients are depicted in Fig. 5. The average time taken for closure of a window was 6 months, with or without TB.

Fig. 5.

Patient 1. a Healthy 5-year old window showing patent BPF. b Pedicled omentum being harvested by an upper midline laparotomy. c Healed window of the patient with primary closure of skin over transposed omentum. Patient 2. d TB right pyo-pneumothorax. e Healed window with an unsightly scar. f Elective repair of the scar after 5 years by a latissimus dorsi flap

Discussion

Our series of 437 patients who needed surgical management for ET is one of the largest single-centre experiences reported from India. Most of our patients were between 21 and 50 years of age (mean 38 years) with a male sex and right side preponderance conforming to other studies [8]. The available international literature states that an infected para-pneumonic effusion is the commonest cause of empyema [2]. But in our series, TB emerged as the commonest cause, like in other Indian studies [9]. Despite TB being the predominant aetiology, only one patient in our series had autoimmune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) associated with it. There was a high incidence of pseudomonas infection in our patients (14%). This was probably hospital acquired, since 51% of the patients have had multiple pleurocentesis and ICD placements done on them elsewhere, prior to surgery with us. Diabetes mellitus was the most common associated co-morbidity [10] followed by hypoproteinemia, smoking and anaemia. It was observed that the elderly, diabetics and those with hypoproteinemia were at a high risk of developing an ET after pneumonia (Table 3). These differences were statistically significant when compared with the group of TB ET.

The analysis indicates that the type of surgical procedure performed correlated with four major factors.

Stage of the empyema.

Aetiology of the empyema.

Condition of the underlying lung.

Condition of the patient and the co-morbidities.

Chronicity of the empyema indeed played a role in deciding the management. Most of the para-pneumonic empyemas were acute in nature and so a decortication was the appropriate procedure, as was performed on 65% of the patients with para-pneumonic aetiology. This higher incidence of decortication in infected para-pneumonic ET was statistically significant (Table 4). Long-standing empyema, especially tuberculous, resulted in severe rib crowding and a thick calcific pleural peel entrapping a diseased or fibrosed lung [11]. Most of these patients presented very late. In these patients, an attempt at decortication would be futile, morbid or lethal and a WP was considered to be more suitable, as WP was a relatively minor procedure, which resulted in immediate alleviation of sepsis. Thus, there was a higher incidence (59%) of WP in TB patients. This difference was statistically significant with a p value of 0.001 (Table 4). Other pre-operative risk factors also dictated the type of surgery performed on them. It was noted that 60% of the diabetics, 61.5% of patients with hypoproteinemia and 54% of the anaemic patients underwent a WP only. However, this association did not reach levels of statistical significance (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of major risk factors among the patients who underwent decortication only or a WP only

| Risk factors | Decortication | WP | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TB—248 (57%) | 80 | 145 | 0.0001 |

| Diabetes—97 (22%) | 34 | 58 | 0.15 |

| Anaemia—54 (12.3%) | 24 | 29 | 0.76 |

| Hypoproteinemia—65 (14.8%) | 23 | 40 | 0.27 |

Leucocytosis was present mostly in patients with infected para-pneumonic effusions, which was statistically significant (Table 3). This is due to the fact that most infected para-pneumonic effusions were acute in nature leading to an elevated leukocyte count, whereas TB was a chronic process. However, the presence or absence of leucocytosis was not a criterion in deciding the type of surgery in a patient already planned for surgical management, based on other relevant findings. The most common organism isolated pre-operatively was MTB. In the study by Mohanty et al., Acinetobacter was the most common organism isolated followed by pseudomonas [12]. In the study by Dwari et al., Streptococcus pneumoniae was the most common organism isolated [13]. Diagnosis of TB was based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) positivity, smear, and culture and biopsy reports. TB PCR had the highest yield in identifying tuberculosis, as in other studies [14]. The other bacteria isolated commonly were Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella and Streptococcus pneumoniae. There were one case each of salmonellosis and melioidosis. The most common organism isolated post-operatively was also MTB (23%) followed by pseudomonas (14%). No organisms were isolated in the intra-operative cultures of 151 (35%) patients, which may indicate appropriate and adequate pre-operative antibiotic treatment. It was noted that even among the patients with TB empyema, pseudomonas was the commonest super-added infection (24%). This was probably hospital acquired, as mentioned earlier.

Peri-operative pleural biopsy was sent in 423 (97%) patients. Histopathological study was not done in the patients who underwent open ICD drainage or a minor procedure only, since they already had their pathology proven. The commonest histopathological finding was chronic non-specific pleuritis and not necrotizing granulomatous inflammation due to TB, contrary to the microbiological findings. This might be attributed to the changes in histopathology after adequate treatment with ATT. Seok et al. had also demonstrated that in extra-pulmonary TB, such a pathological change did occur [15]. Of the 101 patients with culture proved TB, 15 patients did not have histopathological evidence of TB. Adenocarcinoma was diagnosed in 5 patients by histopathology only. Fungal empyema was diagnosed only in the post-operative period by culture and histopathology.

In four patients taken up for decortication, the procedure was abandoned and only an ICD was placed instead. In two of these patients, upon thoracotomy, intense active TB was noticed inside the pleural cavity despite having been on ATT for the preceding 8 weeks. The tissues were friable and were bleeding briskly to touch due to the uncontrolled disease precluding a definitive surgery. The third patient had a valvular heart disease and became haemodynamically unstable at the induction of anaesthesia. A limited thoracotomy was done under local anaesthesia to suck out the pus and infected debris and to place an ICD. The fourth patient’s empyema cavity had shrunk rapidly and a decortication was considered unnecessary, and hence, only an ICD was placed.

The mortality of 4 (0.9%) patients was lesser than that in other studies [16]. All the deaths were from the decortication group. Out of the 4 deaths, two were because of multi-organ failure due to persistent sepsis. The third patient had a myocardial infarction in the immediate post-operative period. The fourth one had a pre-operatively undetected mycotic aneurysm of the inferior pulmonary vein extending into the left atrium, which ruptured during surgery. There was no mortality in the patients who underwent a thoracoplasty or a WP, which was lesser than what is observed in other studies [16].

Among the patients who underwent decortication, 6% had persistent air leak like in other studies [17]. Persistent air leak was defined as an air leak that persists for a week after surgery [18]. Two of these patients were treated by a WP, while others were managed with prolonged use of ICD tubes only. A WP to treat a failed primary procedure was best carried out after a delay of 3 weeks, since it ensures that the mediastinum gets fixed and the visceral pleura thickened, in order to avoid further collapse of the lungs when a WP was resorted to. The average post-operative hospital stay was significantly longer for TB patients undergoing decortication (Table 4) due to the fact that they present late with established sequelae that it takes longer for the lung to expand and obliterate the space. The average post-operative hospital stay was longer in patients undergoing thoracoplasty, since in these patients with a highly fibrosed lung, the ICD were retained in situ for up to 3 weeks. This conservative management with ICD was perhaps the reason for the paucity of post-operative complications and failed surgical management in our patients. In most patients undergoing complicated decortications, besides the conventional apical and basal tubes, a third tube was also placed, positioned as mentioned earlier, since it had been noticed that in some patients with chronic empyema and fibrosed lungs, loculations of infected fluid developed in the retro-sternal or sub-pulmonic spaces post-operatively, complicating recovery. These loculations were difficult to access for drainage, if and when they occurred. However there were no studies supporting the use of a third drain and it was based on our observations only.

Seven patients, who had undergone a WP, required a refashioning of the os of the window during follow-up. The dictum was that the window should be larger than what was considered just adequate for the size of the empyema cavity. The cavity of the empyema, after the infections cleared up, and the BPF closed, rapidly granulated, with simultaneous expansion of the lungs (Fig. 3a, b, d, e). Re-epithelialisation occurred starting from the skin edges around the os. However, a refashioning of a prematurely closing os might be necessary, as in seven (4%) of our patients. The large scar at the site of a healed window site was often unsightly (Fig. 5e). In our experience, the shortest time, a window closed was 3 months and some windows were still patent for more than 10 years. The average time it took for a window to close was 6 months. Patients from remote areas with uncomplicated surgeries were requested to follow up with local doctors and correspond by email only and hence not included in the hospital follow-up statistics. Out of the patients who returned for review, 62% were from the WP group and only 38% were from the decorticated group.

The guidelines available for the management of empyema are the American Association of Thoracic Surgery (AATS) and the European Association of Cardiothoracic Surgery (EACTS) guidelines [19, 20]. The AATS guidelines suggest decortication for chronic empyema as a class IIa recommendation [19]. WP can be performed in medically unfit patients and patients with large BPF (class IIa) [19]. Thoracoplasty with resection of ribs may be considered in select cases to obliterate the infected pleural space where previous measures have failed (class IIb) [19]. There are no class I recommendations, as there are no adequate prospective studies to suggest a recommendation. It has to be reiterated that these recommendations are for non-tubercular empyema only. The EACTS guidelines suggest VATS decortication and drainage as a class 1b recommendation for chronic empyema [20]. Open decortication is recommended as a class IIb recommendation [20]. There are no recommendations given for the indication of thoracoplasty or a WP. TB empyema remains an area in which there is no level A evidence to guide practice [20]. Dewan, in a large single-centre experience from India, had presented that in TB empyema, WP and thoracoplasty were performed in 86% of patients and decortications only in 14% of the patients [11]. In our study, 59% of TB patients underwent a WP and 32% underwent decortication only. In the presence of a chronic TB with well-established sequelae of chronic empyema, it would be prudent to do a WP, rather than attempt a decortication. Both our study and the study by Dewan indicate the salient role of WP in the management of TB empyema. Both the studies are retrospective in nature. Based on our extensive experience and good results, the protocol that was followed by us as detailed in the “Methodology” section may be adopted for the management of ET in India. But it has to be emphasized that the outcome was dependent on a number of factors that include surgeons’ experience and expertise, the infrastructure of the institution, and the input of the surgical team and support staff.

Limitations of the study

The major limitations of the study are its retrospective nature and inadequate follow-up. As there are no established guidelines for the management of ET secondary to TB, the decision-making relied mainly on the experience and expertise of the surgeon. Since most of our patients were from remote areas, they were advised to follow up in their local hospitals only, accounting for the poor follow-up in our study. Late mortality and late complications were also not analysed due to the poor follow-up. VATS was not considered in any of our patients due to the intrinsic characteristics of our disease spectrum, mentioned earlier. The algorithm proposed was based on observation and proper prospective studies may be needed to validate it.

Conclusion

Our study establishes that surgical management of ET provides very good results with negligible mortality and morbidity, even in those with late presentations and established late sequelae. We assert that in a developing nation like India, the details of the patient cohort are remarkably different from those in developed areas or countries. Here, TB remains the commonest aetiology and it is often associated with co-morbidities like diabetes, anaemia and hypo-proteinaemia. WP or thoracoplasties are frequently employed in treating our patients with ET. These older surgical techniques are rarely used in developed countries where the patients present early, mostly with a non-tubercular aetiology. Thus, the international guidelines meant for developed regions are seldom relevant in the Indian scenario. Our concerns with the chronicity, aetiology, condition of the underlying lungs, and the established sequelae play an important role in our surgical management of ET. Another major factor that determines the surgical management of chronic ET in India is the non-availability of surgeons experienced in this field in remote areas.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Santhosh R Benjamin. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Santhosh R Benjamin and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. The final manuscript was written by Santhosh R Benjamin and Birla Roy Gnanamuthu. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The approval of the institutional review board has been obtained.

Informed consent

Written consent for studies and publication were obtained from the patients prior to the surgery.

Human and animal rights

The study has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Frank S, Pedro DN, Scott JS. Benign pleural diseases: empyema thoracis. In: Sabiston and Spencer surgery of the chest, 9th Edition. Elsevier Company; 2015:467–75.

- 2.Light RW. Parapneumonic effusions and empyema. In: Rhyner S, Winter N, Koleth J, editors. Pleural diseases. 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. pp. 179–210. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malhotra P, Aggarwal AN, Agarwal R, Ray P, Gupta D, Jindal SK. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of empyema thoracis in 117 patients. A comparative analysis of tubercular vs. non tubercular aetiologies. Respir Med. 2007;101:423–430. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrews NC, Parker EF, Shaw RR, Wilson NJ, Webb WR. Management of nontuberculous empyema. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1962;85:935–936. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wait MA, Beckles DL, Paul M, Hotze M, Dimaio MJ. Thoracoscopic management of empyema thoracis. J Minim Access Surg. 2007;3:141–148. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.38908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thourani VH, Lancaster RT, Mansour KA, Miller JI., Jr Twenty-six years of experience with the modified Eloesser flap. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:401–405. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)00470-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirsh MM, Rotman H, Behrendt DM, Orringer MB, Sloan H. Complications of pulmonary resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 1975;20:215–236. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(10)63878-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marks DJ, Fisk MD, Koo CY, et al. Thoracic empyema: a 12-year study from a UK tertiary cardiothoracic referral centre. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Acharya PR, Shah KV. Empyema thoracis: a clinical study. Ann Thorac Med. 2007;2:14–17. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.30356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kundu S, Mitra S, Mukherjee S, Das S. Adult thoracic empyema: a comparative analysis of tuberculous and nontuberculous etiology in 75 patients. Lung India. 2010;27:196–201. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.71939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dewan RK. Surgery for pulmonary tuberculosis - a 15-year experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:473–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohanty S, Kapil A, Das BK. Bacteriology of parapneumonic pleural effusions in an Indian hospital. Trop Doct. 2007;37:228–9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Dwari AK, Jha S, Sarkar S, Misra S, Chakraborty S, Mandal A. A study of bacterial isolates and their sensitivity pattern to antibiotics in empyema thoracis cases in a tertiary care hospital. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2018;7:4178–4181. doi: 10.14260/jemds/2018/934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tueller C, Chhajed PN, Buitrago-Tellez C, Frei R, Frey M, Tamm M. Value of smear and PCR in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in culture positive pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:767–772. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00046105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seok H, Jeon JH, Oh KH, Choi HK, Choi WS, Lee YH, Seo HS, Kwon SY, Park DW. Characteristics of residual lymph nodes after six months of antituberculous therapy in HIV-negative individuals with cervical tuberculous lymphadenitis. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:867. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4507-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molnar TF. Current surgical treatment of thoracic empyema in adults. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;32:422–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrade-Alegre R, Garisto JD, Zebede S. Open thoracotomy and decortication for chronic empyema. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2008;63:789–793. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322008000600014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazarus DR, Casal RF. Persistent air leaks: a review with an emphasis on bronchoscopic management. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:4660–4670. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.10.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen KR, Bribriesco A, Crabtree T, Denlinger C, Eby J, Eiken P, Jones DR, Keshavjee S, Maldonado F, Paul S, Kozower B. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery consensus guidelines for the management of empyema. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:e129–e146. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scarci M, Abah U, Solli P, Page A, Waller D, van Schil P, Melfi F, Schmid RA, Athanassiadi K, Sousa Uva M, Cardillo G. EACTS expert consensus statement for surgical management of pleural empyema. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;48:642–653. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezv272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]