Abstract

Objective

The eradication of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) reduces the risk for gastric cancer (GC) development, but it cannot prevent GC completely. We investigated the risk factors of early GC development after the eradication of H. pylori, based on the histological characteristics of gastric mucosa.

Methods

Sixty-one patients who underwent endoscopic submucosal dissection for early GC after successful H. pylori eradication (Group A) and 122 patients without developing a gastric neoplasm over 3 years after successful H. pylori eradication (Group B) were analyzed. We compared the histological findings of the patients enrolled in Group A and Group B before and after the propensity score-matching.

Results

Comparing the characteristics of two the groups, Group A consisted predominantly of males, had significantly more elderly patients, and the years after successful eradication tended to be longer. We performed score matching for these three factors to reduce the influence of any confounding factors. After matching, the scores of inflammation for Group A (n=54) was significantly higher than those of Group B (n=54) at the greater curvature of the antrum, the lesser curvature of the corpus, and the greater curvature of the corpus. According to a multivariate analysis, inflammation of the greater curvature of the antrum and lesser curvature of the corpus were found to be independent risk factors. The risk ratio and 95% CI were 5.92 (2.11-16.6) (p<0.01), and 3.56 (1.05-13.2) (p=0.04), respectively.

Conclusion

A continuous high level of inflammation of the background gastric mucosa may be a risk factor for gastric cancer onset after H. pylori eradication.

Keywords: background gastric mucosa, gastric cancer, inflammation, Helicobacter pylori, propensity score matching

Introduction

It is well known that the eradication of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) reduces the risk for gastric cancer (GC) development (1-5). In Japan, the eradication of H. pylori-associated gastritis has been included in national health insurance coverage since February 2013, aiming to suppress the new onset of GC. It is already known that H. pylori eradication does not completely prevent GC development in all individuals (6). GC after H. pylori eradication is very interesting in that it develops and advances in different environments and conditions, in comparison to H. pylori-positive GC. Therefore, it is important to characterize the clinicopathological features of GC after H. pylori eradication and identify its developmental differences with GC with ongoing H. pylori infection.

Several studies have been reported regarding the risk factors for the development of GC after eradication, regarding the gastric mucosa, gastric mucosal atrophy and intestinal metaplasia (IM) (7-10). Kodama et al. performed a histological evaluation of the background gastric mucosa before the eradication of H. pylori, using the updated Sydney scoring system. They reported that inflammation, as well as the atrophy scores and IM scores at the greater curvature of the corpus were significantly higher in the GC group who underwent the successful eradication of H. pylori than in the matched non-GC group, and they mentioned that inflammation might promote the onset of GC (8).

However, the histological features of the background gastric mucosa at the time of GC detection after the eradication of H. pylori are not well known. Thus, we performed a retrospective analysis to investigate the risk factors for early GC development after H. pylori eradication, based on the histological characteristics of the gastric mucosa. Especially, we focused on chronic inflammation, and compared GC patients after successful eradication and non-GC patients.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We enrolled 426 patients who underwent endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for early initial GC at Okayama University Hospital between January 2013 and June 2017, excluding postoperative stomach cancer, stomach tube cancer, and cases with a history of endoscopic resection for gastric cancer. Six patients who tested negative for H. pylori infection without any previous definite eradication and four patients who were histologically diagnosed with gastric carcinoma with lymphoid stroma, were excluded. For gastric carcinoma with lymphoid stroma it was considered to be difficult to evaluate the background mucosa accurately because of the dense infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages from mucosa to submucosa.

Additionally, we excluded 209 patients who were H. pylori positive and 42 patients with insufficient eradication data. One hundred and sixty-five patients had achieved successful eradication before the detection of their initial GC.

GC of patients who have eradicated within 1 year might have been cancer undetected prior to successful eradication, and thus might have been affected by H. pylori infection (8,11,12). In the present study, we defined GC after successful H. pylori eradication as that which was detected and diagnosed at least 1 year after the therapy. Therefore, we also excluded 94 patients without a previous history of eradication and 10 patients who were discharged after eradication for less than 1 year. Finally, the remaining 61 patients who underwent ESD with post H. pylori eradication were analyzed in the present study and defined as Group A (GC group) (Fig. 1). In cases with multiple lesions, the largest lesion was selected.

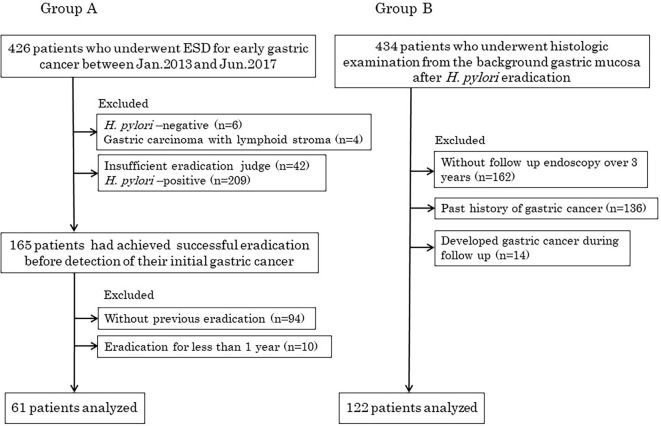

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients.

In the control group, we enrolled 434 patients who underwent a histologic examination from the background gastric mucosa after H. pylori eradication. However, patients who had not received follow-up endoscopy over 3 years (n=162), had a history of gastric cancer (n=136), and developed GC during the follow-up (n=14) were excluded. Finally, we enrolled 122 patients. This group was defined as Group B (a non-GC group) (Fig. 1).

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Okayama University Hospital. Informed consent was acquired by the opt-out method.

Evaluation of H. pylori status

In most of the cases of group A, H. Pylori eradication had been performed by another institution. Therefore, we checked that the success of the eradication was clearly described in the medical records, and verified before ESD when anti-H. pylori antibody titers was <3 (Eiken E-plate test) and the histologic examination from the background gastric mucosa were negative. On the other hand, for Group B, H. pylori eradication was confirmed by a urea breath test (cutoff value, 2.5 per mil) and a histologic examination.

Endoscopic atrophy

We evaluated endoscopic gastric atrophy according to the Kimura-Takemoto classification (13), and classified the results into three grades: mild (C-1 and C-2 patterns), moderate (C-3 and O-1 patterns), and severe (O-2 and O-3 patterns).

Histological analysis

Three biopsy specimens were obtained from the greater curvature of the antrum, the lesser curvature of the corpus, and the greater curvature of the corpus. The gastric mucosa samples were evaluated according to the updated Sydney system, with the degree of inflammation (mononuclear cell infiltration), neutrophil activity, atrophy, and IM classified and scored as ‘normal,’ 0; ‘mild,’ 1; ‘moderate,’ 2; and ‘marked,’ 3; according to a visual analogue scale (14). In Group B (control group), biopsy specimens were obtained at every follow up endoscopy, and the newest data was enrolled. In Group A (cancer group), biopsy specimens were obtained at the time of preoperative endoscopy (approximately 1-2 months before ESD).

Furthermore, we conducted a pilot study using an immunohistochemical analysis to elucidate the type of mononuclear cell infiltration. Sections were immunohistochemically stained using an automated Bond Max stainer (Leica Biosystems, Melborne, Australia). The following primary antibodies were used: CD79a (JCB79a, dilution 1:50; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), CD3 (LN10, dilution 1:100; ABCAM, Cambridge, UK).

Experienced pathologists from Okayama University Hospital performed the histological evaluations. We compared the scores from the histological evaluations of the gastric mucosa between the two groups.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as numbers for categorical variables. The continuous variables were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U-test. The categorical variables were evaluated with the chi-square test and Fisher's exact tests.

We performed a multivariate analysis to assess the strength and independence of mucosal inflammation. A multivariate analysis was performed using a logistic regression analysis. In order to perform the analysis, we changed each score grade (from normal to marked by updated Sydney system) to two groups (normal vs. mild-marked).

We used a propensity score-matching analysis to adjust any significant differences in the baseline clinical characteristics of the patients and to reduce those that were considered to be potentially confounding factors (15,16), including age, gender, and years after successful eradication. The propensity score model was well calibrated and clearly distinguished between Group A and Group B (c-statistic = 0.69). The c-statistic was calculated by measuring the receiver operating characteristic curve to assess the validity of the model. Before and after propensity score-matching, we compared the histological findings of the enrolled patients in Group A and Group B within a caliper of width of 0.2 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score.

The statistical analysis was performed using the JMPⓇ13 software package (SAS Institute, Cary, USA), and a value of p<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Characteristics of the gastric cancer group after successful eradication

Table 1 shows the lesion characteristics of GC group (Group A) after successful eradication. Of the 61 cases of Group A, 35 GCs were located in the middle third of the stomach, thus being the most numerous. We also found that the tumor size was small (14.7±1.1 mm), the macroscopic type of tumor was mostly flat/depressed, and the histological type was mostly differentiated-type adenocarcinoma with intramucosal invasion. These characteristics did not differ from the characteristics of GC after eradication as previously reported (7,12,17,18).

Table 1.

Lesion Characteristics of Gastric Cancer Group after Successful Eradication.

| n=61 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Location | ||

| Upper third | 5 | |

| Middle third | 35 | |

| Lower third | 21 | |

| Tumor size (mm, mean±SD) | 14.7±1.1 | |

| Macroscopic type | ||

| Protruding | 9 | |

| Depressed/Flat | 52 | |

| Histological type | ||

| Differentiated | 55 | |

| Undifferentiated/mixed | 6 | |

| Depth | ||

| M/SM1† | 58 | |

| SM2‡ | 3 | |

| Curability of endoscopic resection | ||

| Curative | 54 | |

| Non curative | 7 |

Data are presented as numbers or mean±SD, SD: standard deviation, M: mucosal invasion

†SM1; submucosal invasion depth<500 μm from muscularis mucosa laye

‡SM2; submucosal invasion depth ≥500 μm from muscularis mucosa layer

Comparison of the clinical characteristics

Comparing the characteristics of Group A and Group B, we found that Group A consisted predominantly of males (44 males vs. 17 females), while patients from Group B had an equal gender distribution (61 males vs. 61 females) (p<0.01). There were also significantly more elderly patients (median age, 71 years vs. 68 years, p<0.01). Although the difference was not significant, the years after successful eradication were longer in Group A than in Group B (4.64±4.4 vs. 4.16±2.2, p=0.33) (Table 2). There may have been some bias, because of the difference depending on gender, age, and the years after successful eradication. Therefore, we reconsidered the histologic evaluation of the background gastric mucosa by propensity score-matching the age, gender, and years after H. pylori eradication.

Table 2.

Comparison of the Clinical Characteristics between Gastric Cancer Group (Group A) and Non-gastric Cancer Group (Group B) before and after Propensity-score Matching.

| All patients | Propensity-matched patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (n=61) |

Group B (n=122) |

p value | ASD | Group A (n=54) |

Group B (n=54) |

p value | ASD | |

| Gender (male/female) | 44/17 | 61/61 | <0.01 | 0.421 | 37/17 | 34/20 | 0.68 | 0.111 |

| Age (years, median) | 71 (53-85) | 68 (29-87) | <0.01 | 0.601 | 70 (53-83) | 71 (51-83) | 0.62 | 0.107 |

| Years after successful eradication (years, mean±SD) | 4.6±4.4 | 4.2±2.2 | 0.33 | 0.115 | 4.5±4.4 | 4.6±2.5 | 0.87 | 0.028 |

Data are presented as numbers, mean±SD or median (range), SD: standard deviation, ASD: absolute standardized difference

After propensity score-matching, 54 patients with GC and 54 patients without GC were included in each group. There was no significant difference in age, gender, and the years after successful eradication between the two groups (Table 2).

Comparison of the histological findings of the background gastric mucosa

We compared the scores in the background gastric mucosa between Group A and Group B using the updated Sydney scoring system. In the background gastric mucosa evaluation, neutrophils were not described because almost all of them had disappeared after H. pylori eradication in both groups. Inflammation (mononuclear cell infiltration) (0.77±0.56 vs. 0.33±0.47, p<0.01), atrophy (1.17±0.90 vs. 0.58±0.77, p<0.01), and IM (0.80±0.85 vs. 0.38±0.71, p<0.01) scores at the greater curvature of the antrum were significantly higher in Group A than in Group B. Similarly, inflammation (0.89±0.45 vs. 0.62±0.57, p<0.01), atrophy (1.59±0.99 vs. 0.84±0.96, p<0.01), and IM (1.52±1.16 vs. 0.77±0.95, p<0.01) scores at the lesser curvature of the corpus were significantly higher in Group A than in Group B. Furthermore, the inflammation (0.57±0.59 vs. 0.31±0.47, p<0.01) and atrophy (0.41±0.72 vs. 0.17±0.42, p=0.02) scores at the greater curvature of the corpus were significantly higher in Group A (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of the Histological Findings between Group A and B.

| Group A (n=61) |

Group B (n=122) |

p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greater curvature of the antrum | ||||||

| Inflammation | 0.77±0.56 | 0.33±0.47 | <0.01 | |||

| Atrophy | 1.17±0.90 | 0.58±0.77 | <0.01 | |||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 0.80±0.85 | 0.38±0.71 | <0.01 | |||

| Lesser curvature of the corpus | ||||||

| Inflammation | 0.89±0.45 | 0.62±0.57 | <0.01 | |||

| Atrophy | 1.59±0.99 | 0.84±0.96 | <0.01 | |||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 1.52±1.16 | 0.77±0.95 | <0.01 | |||

| Greater curvature of the corpus | ||||||

| Inflammation | 0.57±0.59 | 0.31±0.47 | <0.01 | |||

| Atrophy | 0.41±0.72 | 0.17±0.42 | 0.02 | |||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 0.35±0.76 | 0.18±0.53 | 0.10 |

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation.

Inflammation of the background gastric mucosa of the GC group after eradication was significantly higher than the scores for the matched Group B with the greater curvature of the antrum (0.78±0.57 vs. 0.28±0.45, p<0.01), the lesser curvature of the corpus (0.89±0.42 vs. 0.64±0.59, p<0.01), and the greater curvature of the corpus (0.59±0.60 vs. 0.35±0.48, p=0.03), respectively.

Other significant differences were observed in the atrophy of the greater curvature of the antrum (1.13±0.87 vs. 0.64±0.77, p<0.01), the lesser curvature of the corpus (1.62±1.02 vs. 0.92±1.01, p<0.01), and in IM of the greater curvature of the antrum (0.78±0.82 vs. 0.46±0.77, p=0.02), the lesser curvature of the corpus (1.57±1.19 vs. 0.85±0.98, p<0.01) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of the Histological Findings between Group A and B (after Matching).

| Group A (n=54) |

Group B (n=54) |

p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greater curvature of the antrum | ||||||

| Inflammation | 0.78±0.57 | 0.28±0.45 | <0.01 | |||

| Atrophy | 1.13±0.87 | 0.64±0.77 | <0.01 | |||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 0.78±0.82 | 0.46±0.77 | 0.02 | |||

| Lesser curvature of the corpus | ||||||

| Inflammation | 0.89±0.42 | 0.64±0.59 | <0.01 | |||

| Atrophy | 1.62±1.01 | 0.92±1.01 | <0.01 | |||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 1.57±1.19 | 0.85±0.98 | <0.01 | |||

| Greater curvature of the corpus | ||||||

| Inflammation | 0.59±0.60 | 0.35±0.48 | 0.03 | |||

| Atrophy | 0.44±0.75 | 0.19±0.49 | 0.06 | |||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 0.40±0.79 | 0.17±0.47 | 0.11 |

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation.

The risk factors for the development of GC from the histological findings of the background gastric mucosa are shown in Table 5. According to a multivariate analysis, not only atrophy of the lesser curvature of the corpus, but also inflammation of the greater curvature of the antrum and lesser curvature of the corpus, were found to be independent risk factors. The risk ratio and 95% CI were 6.05 (1.28-35.5) (p=0.03), 5.92 (2.11-16.6) (p<0.01), and 3.56 (1.05-13.2) (p=0.04), respectively.

Table 5.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of the Histological Findings.

| Group A (n=54) |

Group B (n=54) |

Univariate analysis p value |

Risk ratio (95%CI) |

Multivariate analysis p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greater curvature of the antrum | |||||

| Inflammation | 39 | 15 | <0.01 | 5.92 (2.11-16.6) | <0.01 |

| Atrophy | 35 | 21 | <0.01 | ||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 31 | 18 | 0.01 | ||

| Lesser curvature of the corpus | |||||

| Inflammation | 46 | 30 | <0.01 | 3.56 (1.05-13.2) | 0.04 |

| Atrophy | 44 | 27 | <0.01 | 6.05 (1.28-35.5) | 0.03 |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 39 | 26 | <0.01 | ||

| Greater curvature of the corpus | |||||

| Inflammation | 30 | 19 | 0.03 | 2.31(0.93-5.96) | 0.07 |

| Atrophy | 15 | 9 | 0.15 | ||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 13 | 7 | 0.13 |

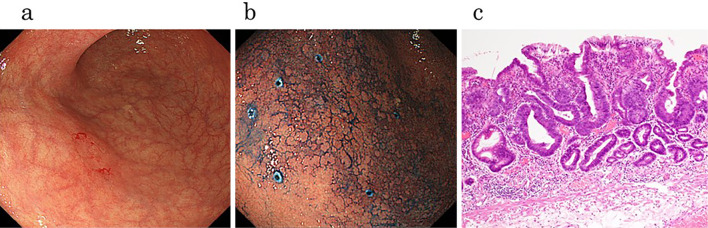

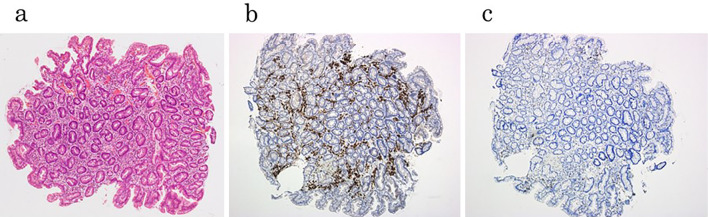

We present a typical case of GC that was detected 10 years after eradication. It was difficult to determine the border line of the lesion in this case (Fig. 2a), because the metaplasia of the mucosa was remarkable (Fig. 2b). The histological examination confirmed the presence of an epithelium with a low degree of atypicality (ELA) in the surface layer of a low cancerous lesion (Fig. 2c), which Masuda et al. reported as the characteristic feature in patients who have undergone successful eradication (19). We examined the background gastric mucosa before ESD. Inflammation was observed in all three biopsy specimens as well as around the lesion (Supplementary material), with the tissue of the lesser curvature of the corpus being the most remarkable of these three specimens (Fig. 3a). We performed an immunohistochemical analysis, and revealed that CD79 was strongly positive (Fig. 3b), while CD3 was partially positive (Fig. 3c). We performed the same analysis on several other cases, and these results were also recorded.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic and pathological features of gastric cancer after successful H. pylori eradication therapy. (a) Conventional endoscopic view showed a flat reddish lesion, but there was no marked difference between the cancerous area and surrounding non-cancerous area. (b) Chromoendoscopy by indigo carmine was used and it was still difficult to determine the border line of the lesion because of the metaplasia of mucosal background. (c) Histological examination confirmed epithelium with a low degree of atypicality (ELA) in the surface layer of a low cancerous lesion.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical analysis of the tissue of lesser curvature of the corpus. (a) Inflammatory cells were found by Hematoxylin and Eosin staining. (b) CD79a was strongly positive. (c) CD3 was partially positive.

Discussion

Many studies have been conducted to investigate the risk factors for GC after the eradication of H. pylori. Age at eradication (6,8), severe atrophic gastritis, and intestinal metaplasia especially of the corpus (1,20,21), among others, have been evaluated. In this study, significant differences were observed in atrophy and IM of the greater curvature of the antrum, the lesser curvature of the corpus. These results are compatible with previous reports that recommended early eradication before the occurrence of atrophy and IM progression. Furthermore, we have focused on the histological characteristics of the background gastric mucosa after H. pylori eradication. Only the inflammation score of every background gastric mucosa specimen of the GC group was significantly higher than that of the non-GC group. On the other hand, the significant difference in atrophy and IM in the greater curvature of the corpus disappeared after propensity score matching. We consider the reason for this phenomenon to be due to the fact that the cases with atrophy and IM in the greater curvature of the corpus were relatively rare.

Moreover, the degree of mononuclear cell infiltration in the IM mucosa is considered to be greater than in the non-metaplastic mucosa because inflammation of the gastric mucosa thought to have a close association with atrophy and IM. Therefore, we added a multivariate analysis, and thereby identified that inflammation of the greater curvature of the antrum and lesser curvature of the corpus tended to be independent risk factors.

Chronic inflammation is characterized by the infiltration of mononuclear cells. It has been reported that the inflammation score of the gastric mucosa showed significant degradation after the eradication of H. pylori infection from about 6 months to 5 years (8,22). We also showed that the inflammation of the greater curvature of the antrum, and the lesser curvature and the greater curvature of the corpus was significantly higher in the GC group compared to the age, sex, and the years after successful eradication in the matched non-GC group. Therefore, we consider that the continuous mononuclear cell infiltration of the gastric mucosa could be a risk factor for GC after successful H. pylori eradication.

Several reasons can be considered as to why mononuclear cell infiltration remains after successful eradication and it may therefore become a risk factor for the onset of GC. Kodama et al. reported that the background gastric mucosa of the GC group had greater mononuclear cell infiltration than the non-GC group before the eradication of H. pylori, and they hypothesized that the continuous inflammation after eradication might promote the onset of GC (8). In this study, mononuclear cell infiltration at the time when GC was detected was significantly higher than that of the non-GC group. Thus, we demonstrated that continuous inflammation before and after eradication can promote the onset of GC.

Continuous chronic inflammation with mononuclear cell infiltration could accelerate the levels of DNA hypermethylation in the gastric mucosa, and could thereby promote the onset of GC. Reports on GC studies have shown that aberrant DNA methylation plays an important role, and the degree of accumulation of aberrant DNA methylation correlates highly with GC risk (23,24).

Once H. pylori has been eradicated, the DNA methylation level decreases somewhat but it does not disappear completely (25,26). Persistent methylation levels after eradication are considered to reflect methylation in the stem cells (27) and the degree of residual DNA methylation could closely correlate with GC risk (28).

Schneider et al. demonstrated that chronic inflammation, as measured by the level of infiltration of mononuclear cells, was a significant factor for methylation after adjusting the other variables (29). From this study, it is possible that, in the case of the GC groups, chronic inflammation remained even after H. pylori eradication, and they also demonstrated higher DNA methylation levels than the non-GC groups.

This cohort study had a single center retrospective design. Therefore, there are several limitations associated with this study. First, the patients' background of each group such as BMI, history of alcohol intake, smoking, family history, and so on were not considered. Sun et al. demonstrated that GC risk was affected by lifestyle factors, which may regulate the expression of inflammatory cytokines and promote gastric carcinogenesis (30). There has been no report on the relationship between GC developing after eradication and lifestyle factors. However, chronic inflammation caused by lifestyle factors may have affected our results as chronic inflammation of the background gastric mucosa is an important factor in GC development.

Second, there was not sufficient data available on the background gastric mucosa before H. pylori eradication in the GC group. Therefore, it is difficult to compare between the two groups before eradication. Third, we could not adequately assess and provide details on the presence of mononuclear cells. Nonetheless, we conducted a pilot study using an immunohistochemical analysis to elucidate the type of mononuclear cell infiltration, and as a result, CD79a was strongly positive. CD79a serves as a pan-B cell marker. In animal models, CD79a invasion has been reported to be observed in the gastric mucosal model of H. pylori infection (31). Several studies have reported that the spontaneous activation of B cells promoted de novo epithelial carcinogenesis by initiating chronic inflammation (32-34). Our immunostaining results suggest the possibility that the development of GC after H. pylori eradication is connected to the persistence of chronic inflammation after eradication. In the future, a more detailed study, based on an immunohistochemical analysis of mononuclear cell infiltration, should be conducted.

Finally, because of the short period of time for the development of new gastric cancer after eradication therapy, this study may have sometimes identified the tumor progression of a preexisting precursor rather than tumor initiation after eradication therapy. Take et al. described in a recent manuscript that the risk of gastric cancer developing after eradication of H. pylori was greater in the second decade of follow-up than in the previous 10-year period, and endoscopic surveillance for gastric cancer should thus be continued beyond 10 years after the eradication of H. pylori infection (35). Therefore, to investigate the association between persistent mucosal inflammation and new tumor development, a long-term cohort study is needed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study suggested that the high level of mononuclear cell infiltration of the background gastric mucosa may be a risk factor for GC onset after eradication, in addition to gastric atrophy and intestinal epithelialization. In the future, more intensive endoscopic follow-up is needed for patients who have been identified as a high-risk group based on their background gastric mucosa after the eradication of H. pylori.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Supplementary Material

Histological examination of Fig.2 case that was evaluated by the updated Sydney system.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Ms. Tokumitsu for conducting the data collection.

References

- 1. Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med 345: 784-789, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fukase K, Kato M, Kikuchi S, et al. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 372: 392-397, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, et al. The effect of eradicating Helicobacter pylori on the development of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Am J Gastroenterol 100: 1037-1042, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takenaka R, Okada H, Kato J, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication reduced the incidence of gastric cancer, especially of the intestinal type. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25: 805-812, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choi IJ, Kim YI, Park B. Helicobacter pylori and prevention of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med 378: 2244-2245, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, et al. The long-term risk of gastric cancer after the successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori. J Gastroenterol 46: 318-324, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mori G, Nakajima T, Asada K, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection and successful Helicobacter pylori eradication: results of a large-scale, multicenter cohort study in Japan. Gastric Cancer 19: 911-918, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kodama M, Murakami K, Okimoto T. Histological characteristics of gastric mucosa prior to Helicobacter pylori eradication may predict gastric cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol 48: 1249-1256, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shichijo S, Hirata Y, Niikura R, et al. Histologic intestinal metaplasia and endoscopic atrophy are predictors of gastric cancer development after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gastrointest Endosc 84: 618-624, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murakami K, Kodama M, Sato R, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication and associated changes in the gastric mucosa. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy 3: 757-764, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Asada K, Nakajima T, Shimazu T, et al. Demonstration of the usefulness of epigenetic cancer risk prediction by a multicentre prospective cohort study. Gut 64: 388-396, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Saka A, Yagi K, Nimura S. Endoscopic and histological features of gastric cancers after successful Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Gastric Cancer 19: 524-530, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy 1: 87-97, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol 20: 1161-1181, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nagami Y, Tominaga K, Machida H, et al. Usefulness of non-magnifying narrow-band imaging in screening of early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective comparative study using propensity score matching. Am J Gastroenterol 109: 845-854, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Suzuki S, Gotoda T, Kobayashi Y, et al. Usefulness of a traction method using dental floss and a hemoclip for gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: a propensity score matching analysis (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 83: 337-346, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kamada T, Hata J, Sugiu K, et al. Clinical features of gastric cancer discovered after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori: results from a 9-year prospective follow-up study in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 21: 1121-1126, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Horiguchi N, Tahara T, Kawamura T, et al. Distinct clinic-pathological features of early differentiated-type gastric cancers after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2016: 8230815, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Masuda K, Urabe Y, Ito M, et al. Genomic landscape of epithelium with low-grade atypia on gastric cancer after Helicobacter pylori eradiation therapy. J Gastroenterol 54: 907-915, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, et al. Baseline gastric mucosal atrophy is a risk factor associated with the development of gastric cancer after Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in patients with peptic ulcer diseases. J Gastroenterol 42: 21-27, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shiotani A, Uedo N, Iishi H, et al. Predictive factors for metachronous gastric cancer in high-risk patients after successful Helicobacter pylori eradication. Digestion 78: 113-119, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kodama M, Murakami K, Okimoto T, et al. Ten-year prospective follow-up of histological changes at five points on the gastric mucosa as recommended by the updated Sydney system after Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Gastroenterol 47: 394-403, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nakajima T, Enomoto S, Yamashita S, et al. Persistence of a component of DNA methylation in gastric mucosae after Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Gastroenterol 45: 37-44, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shin CM, Kim N, Lee HS, et al. Changes in aberrant DNA methylation after Helicobacter pylori eradication: a long-term follow-up study. Int J Cancer 133: 2034-2042, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ushijima T. Epigenetic field for cancerization. J Biochem Mol Biol 40: 142-150, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ushijima T, Hattori N. Molecular pathways: involvement of Helicobacter pylori-triggered inflammation in the formation of an epigenetic field defect, and its usefulness as cancer risk and exposure markers. Clin Cancer Res 18: 923-929, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maeda M, Moro H, Ushijima T. Mechanisms for the induction of gastric cancer by Helicobacter pylori infection: aberrant DNA methylation pathway. Gastric Cancer 20: 8-15, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maeda M, Yamashita S, Shimazu T, et al. Novel epigenetic markers for gastric cancer risk stratification in individuals after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gastric Cancer 21: 745-755, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schneider BG, Piazuelo MB, Sicinschi LA, et al. Virulence of infecting Helicobacter pylori strains and intensity of mononuclear cell infiltration are associated with levels of DNA hypermethylation in gastric mucosae. Epigenetics 8: 1153-1161, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sun X, Xiang CJ, Wu J, et al. Relationship between serum inflammatory cytokines and lifestyle factors in gastric cancer. Molecular and Clinical Oncology: 10: 401-414, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Straubinger RK, Greiter A, McDonough SP, et al. Quantitative evaluation of inflammatory and immune responses in the early stages of chronic Helicobacter pylori infection. Infect Immun 71: 2693-2703, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. De Visser KE, Korets LV, Coussens LM. De novo carcinogenesis promoted by chronic inflammation is B lymphocyte dependent. Cancer Cell 7: 411-423, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schwartz M, Zhang Y, Rosenblatt JD. B cell regulation of the anti-tumor response and role in carcinogenesis. J Immunother Cancer 4: 40, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shen M, Sun Q, Wang J, Pan W, Ren X. Positive and negative functions of B lymphocytes in tumors. Oncotarget 7: 55828-55839, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, et al. Risk of gastric cancer in the second decade of follow-up after Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Gastroenterol 55: 281-288, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Histological examination of Fig.2 case that was evaluated by the updated Sydney system.