Abstract

Background

The use of digital health technologies was an integral part to China's early response to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Existing literatures have analyzed and discussed implemented digital health innovations from the perspective of technologies, whereas how policy mechanisms contributed to the formulation of the digital health landscape for COVID-19 was overlooked. This study aimed to examine the contexts and key mechanisms in China’s rapid mobilization of digital health interventions in response to COVID-19, and to document and share lessons learned.

Methods

Policy documents were identified and retrieved from government portals and recognized media outlets. Data on digital health interventions were collected through three consecutive surveys administered between 23 January 2020 and 31 March 2020 by China Academy of Information and Communication Technology (CAICT) affiliated to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT). Participants were member companies of the Internet Health alliance established by MIIT and the National Health Commission (NHC) in June 2016. Self-report digital interventions focusing on social and economic recovery were excluded. Two hundred and sixty-six unique digital health interventions meeting our criteria were extracted from 175 narratives on digital health interventions submitted by 116 participating companies. Thematic analysis was conducted to describe the scope and priority of policies advocating for the use of digital health technologies and the implementation pattern of digital health interventions. Data limitations precluded an evaluation of the impact of digital health interventions over a longer time frame.

Results

Between January and March 2020, national policy directives promoting the use of digital technologies for the containment of COVID-19 collectively advocated for use cases in emergency planning and preparedness, public health response, and clinical services. Interventions to strengthen clinical services were mentioned more than the other two themes (n = 15, 62.5% (15/24)). Using digital technologies for public health response was mentioned much less than clinical services (n = 5, 20.8% (5/24)). Emergency planning and preparedness was least mentioned (n = 4, 16.7% (4/24)). Interventions in support of clinical services disproportionately favored healthcare facilities in less resource-constraint settings. Digital health interventions shared the same pattern of distribution. More digital health technologies were implemented in clinical services (n = 103, 38.7% (103/266)) than that in public health response (n = 91, 34.2% (91/266)). Emergency planning and preparedness had the least self-reported digital health interventions (n = 72, 27.1% (72/266)). We further identified case studies under each theme in which the wide use of digital health technologies highlighted contextual factors and key enabling mechanisms.

Conclusions

The contextual factors and key enabling mechanisms through the use of policy instruments to promote digital health interventions for COVID-19 in China include pathway of policy directives influencing the private sector using a decentralized system, the booming digital health landscape before COVID-19, agility of the public sector in introducing regulatory flexibilities and incentives to mobilize the private sector.

Keywords: Digital health, Coronavirus disease 2019, Telemedicine, Big data, Artificial intelligence

1. Introduction

Advocacy and adoption of digital solutions has since become ubiquitous globally, with national strategies adapted to the stage of the outbreak in different countries [[1], [2]]. Digital interventions were used throughout China's response to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) to strengthen the health system, implement public health measures and engage society. These solutions and underlying strategies will play a role in the transition to living with COVID-19, in on-going risk assessment and helping health services cope with the challenges of global pulsed containment [[3], [4]].

Implemented applications have been analyzed and discussed from the perspective of technologies, potentially overlooking how formulation of the digital health landscape for COVID-19 was contributed by policy directives. This paper provides an analysis of China's policy interventions and application interventions on digital health in the early stage of COVID-19. Through the analysis, the paper aims to understand how the country's digital health strategy for COVID-19 came into being and its wider implications for future digital health policymaking.

2. Methods

2.1. Data collection

This study collected data on central policies and planning documents pertaining to the use of digital technologies in emergency response to COVID-19 and the digital health intervention landscape to understand how they interacted, adapted to each other, and how development actually happened. We did not collect or analyze policies or interventions focusing on social recovery as they very much went beyond the health sector and hence not of our immediate interest.

2.2. Policy data

Policies introduced between 23 January 2020 (Wuhan lockdown date) and 31 March 2020 (13 days after Wuhan first reported zero new cases on 18 March 2020) were retrieved from Chinese government portals and recognized local media outlets.

Government portals: The National Health Commission (NHC), Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC).

Recognized media outlets: People's Daily, Xinhua News, Guangming Daily, Economic Daily, China Daily, Science and Technology Daily.

Key search terms included “COVID-19″, “digital”, “online”, “big data”, “artificial intelligence (AI)”, “telemedicine”, “internet plus healthcare”.

2.3. Digital health intervention data

Digital health intervention narratives were collected from 3 batch of best practice collection report by China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT) released on 16 February, 1 March, and 24 March 2020 respectively. The case collection was finished by public surveys called by the Chinese Internet plus Health Industrial Alliance (an alliance established by MIIT and NHC in 2016, comprising of 138 leading companies in the digital health sector), and received more than 170 response from leading companies of the digital health industry in China. Survey participants were asked to provide information on: (a) intervention time, (b) intervention focus and utilization scenario, and (c) output. All self-reported narratives have been published and can be accessed on CAICT website (http://www.caict.ac.cn/). Self-report digital interventions focusing on social and economic recovery were excluded. 266 unique digital health interventions meeting our criteria were extracted from 175 narratives on digital health interventions submitted by 116 participating companies.

2.4. Data analysis

We used the Asia Pacific Strategy for emerging diseases and public health emergencies (APSED III) [5] as the framework to summarize the content of retrieved policy documents and self-reported text data. Of the eight focus areas for public health ermgency management identified in the framework, Focus area 3 (Laboratories) and 4 (Zoonoses) were two functional areas where biotechnology played a bigger role rather than digital technologies. Therefore in the context of this study, these two focus areas were excluded from our categories. Focus area 7 (Regional preparedness, alert and response) was an area that addresses emergency response beyond national boarders. As this study examined the intervention landscape in China, this focus area was excluded. Focus area 8 (Monitoring and evaluation) placed great emphasis on institutionalizing monitoring and evaluation (M&E) systems. As this study examined interim digital health interventions instead of long-term M&E capacity building, this focus area was also out of consideration. As the flexibility and functional extensibility of digital health interventions blur the line between the focus areas of “Public health emergency preparednes” and “Surveillance, risk assessment and response” defined from the public health perspective, the remaining four focus areas 1, 2, 5, and 6 were merged into three mutually exclusive categories of analysis (Table 1). In the adapted freamwork, we also added non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to the categories for their recognized potential to contribute to pandemic mitigation. Identified NPIs included personal protective measures, environmental measures such as surface and object cleaning, social distancing measures such as contact tracing, and travel-related measures such as entry and exit screening [6]. As digital health interventions using internet technologies by nature could carry out NPIs and risk communication together, we put both NPIs and focus area 6 under the same broad category.

Table 1.

Analysis categories for digital health interventions.

| Categories | Digital health interventions |

|---|---|

| Emergency planning and preparedness | Focus area 1 (Public health emergency preparedness) Focus area 2 (Surveillance, risk assessment and response) |

| Public health response | Focus area 6 (Risk communication) Non-pharmaceutical interventions (personal protective measures, environmental measures, travel-related measures) |

| Clinical services | Focus area 5 (Prevention through health care) |

To understand the contextual and enabling factors that contributed to the rollout of digital health technologies for COVID-19 containment, we further identified cases from narratives submitted to surveys which provide illustrations on interactions between policy directives and private sector engagement.

3. Results

3.1. Trends in policy interventions for the use of digital health technologies in COVID-19

On 25th January 2020, China's first Politburo Standing Committee meeting dealing with the outbreak called for using digital technologies to strengthen public health interventions. Following this, another six politburo meetings refined priorities for the use of digital technologies. On 5th February 2020, the NHC issued the first strategic guidance to outline priority areas for digital health intervention, which included the collection and integration of data from heterogenous sources, reinforcement of institutional capacity to provide telemedicine service, and assessment of existing digital infrastructure to guide local interventions. This all-encompassing guidance was followed by a set of coherent directives issued by multiple ministries involved in emergency management to guide local governments, health providers to develop, deploy, and improve digital applications with private sector involvement. The catalog of major national policies introduced can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

National digital health policies in response to COVID-19 in the early outbreak of 2020.

| Issuing body | Issuing date | Subject | Statement of objectives, priorities, and approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHC | 4 February | Notice on applying information technologies to support the prevention and control of COVID-19 [7] |

|

| NHC | 7 February | Notice on supporting the provision of online health consultation services [8] |

|

| CAC | 10 February | Notice on the protection of personal information and the use of big data to support the joint prevention and control of COVID-19 [9] |

|

| NHC | 19 February | Notice on follow-up with discharged COVID-19 cases [10] |

|

| NHC | 21 February | Notice on providing remote service to severe and critical cases from national telemedicine center [11] |

|

| MIIT | 19 February | Applying next generation of information technology to support COVID-19 control and social recovery [12] |

Apply Internet, big data, cloud computing, Artificial Intelligence and other digital technologies to:

|

| NHC, NHSA | 2 March | Guiding opinions on the provision and reimbursement of online health services during COVID-19 outbreak [13] |

|

| MCA, CAC, MIIT, NHC | 5 March | Recommendations on digital interventions for community infection prevention and control [14] |

|

| NHC | 13 March | Health management solution for discharged COVID- 19 cases [15] |

|

NHC: National Health Commission; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; CAC: Cyberspace Administration of China; MIIT: Ministry of Industry and Information Technology; NHSA: National Health Security Association; MCA: Ministry of Civil Affairs; PPE: personal protective equipment; R&D: research and development.

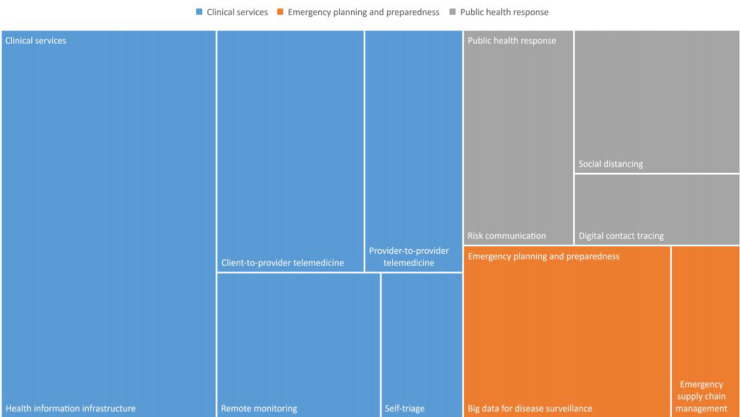

Most policy documents were expansive rather than focusing on one use of digital health technologies. However, as presented in Figure 1, the use of digital health technologies to support clinical services were more frequently mentioned than the other two categories. Of all advocated uses of digital health technologies, telemedicine was addressed more often than all other use cases. Key concern of policy makers was to increase the supply of both provider-to-provider and client-to-provider telemedicine for COVID-19 management and outpatient visit reduction, and to strengthen the information infrastructure and data governance in healthcare facilities to support implementation. Self-triage app and remote monitoring for discharged patient cases were less emphasized. With surge under control, policy emphasis shifted towards the use and regulation of big data for disease surveillance and digital contact tracing.

Figure 1.

Distribution of policy themes.

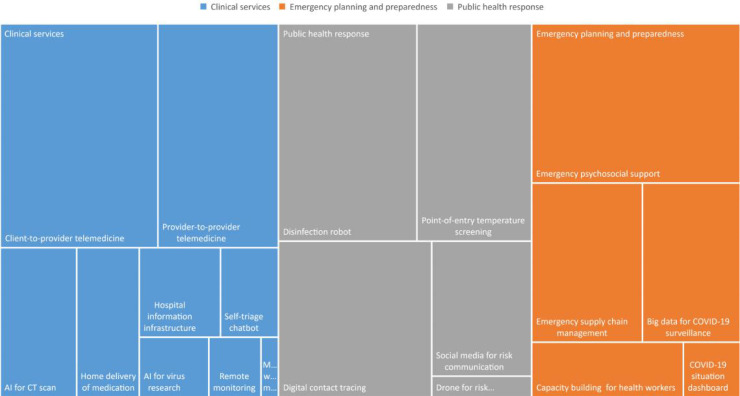

3.2. Characteristics of digital health intervention

Figure 2 provides a treemap view of digital health interventions in our survey data. The overall distribution of interventions by themes shared a similar pattern with policy directives analyzed above. The most common theme for the use of digital health technologies is clinical sevices. In this category, more implementations of telemedicine were seen than others. Though not strictly defined as either of the two types of telemedicine, both AI for computerized tomography (CT) scan, remote monitoring, and home delivery of medication were increasingly being offered as an augmented service of telemedicine systems in resourceful hospitals.

Figure 2.

Digital health intervention themes. COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; Mwm: Medical waste management.

The category of public health response had more disinfection robots, AI tools for point-of-entry temperature screening, and digital applications for contact tracing and mobility restriction than other types of interventions. The popularity of disinfection robots reflected the interest of healthcare facilities and public spaces in environmental measures, and the relatively sufficient supply and maturity of commercial robots to execute the task. Digital applications for contact tracing and mobility restriction were less in number and mostly provided by large technology companies, because the implementation relied on massive data and computing capacities, the wide impact of these applications will be discussed in the section of case studies.

Emergency planning and preparedness has less self-reported use of digital health technologies by participating companies than the two forementioned categories. Digital innovators provided more social platform-based psychosocial support to the public than other interventions to get the health system prepared. This could partially be explained by the friendly ecosystem mainstream digital platforms developed for third-party developers, the huge volume of volunteering professionals. Yet there could also be implication for the professionalism in the kind of support provided. Leading logistics and delivery companies intervened in resource and risk mapping for central and local health authorities. Big data from Internet companies was used to support disease surveillance at all levels of health authorities. Capacity building for health workers to be ready for emergency response was much less digitally intervened. COVID-19 situation dashboards, requiring a strict process of data collection, cleaning, standardization, validation, analysis, and visualization based on information that can only be retrieved from daily news updates on portals of local health authorities, has the least self-reported interventions.

3.3. Case studies of public-private sector interaction in intervention implementation

Most digital health interventions were implemented during the extended Chinese New Year (24 January to 10 February 2020), around the time when policy interventions were actively introduced by central and local governments. Here we present and summarize case studies for each category of interventions which highlighted contextual factors and public-private interacting mechanisms in their critical supporting role to contain of virus transmission.

3.4. Emergency planning and preparedness

The persisting shortage of personal protection equipment (PPE) first few months into COVID-19 demanded a drastic response. Leading e-commerce, logistics and delivery companies developed PPE supply chain management platforms and coordinated with health authorities in Hubei to source and procure PPE from a global network of suppliers. Big data technology was used to forecast and automate matchmaking. One business-to-business (B2B) e-commerce company launched a digital supply chain management system (29 January 2020) with more than 3000 suppliers and delivery services, securing essential volume of PPE early in the outbreak. Industrial Internet Software as a Service (SaaS) platforms connected suppliers not only of PPE, but of essential materials, parts and manufacturing devices to boost PPE production. A leading smart home solution provider repurposed its Industrial Internet platform to connect more than 1600 institutions, 930 hospitals and 500 communities and facilitate 50 million PPE requests. The platform later evolved to and expanded services to support the economic recovery [16].

3.5. Public health response

Health Code is a class of smartphone quick response (QR) code-generating apps developed to provide an assessment of users’ risk profile based on travel and exposure history. These apps help enforce quarantine and reduce interaction between the healthy population and high-risk individuals during the process of reopening the economy and returning to normal life. These apps use green, amber, and red codes for mobility control. A green code enables individuals to travel and go to work; an amber code enforces 7-day home isolation; while a red code enforces 14-day quarantine under medical observation. Using name and personal identity card (ID) as identifiers, these apps collect self-reported health data, travel history and location data in the last 14 days. Risk assessment algorithms are used for data matching to identify close contacts of known cases and generate codes. Information is integrated into data platforms under local government jurisdiction [17]. By design, health code apps were intended to collect case data for risk assessment at reopened workplaces and inform regional policy makers. Yet in practice, they had gatekeeping functions for contact tracing: movement restrictions were enforced not just by contact tracers but the community (e.g. point-of-entry controls at workplaces and in public spaces). They were meant to keep communities vigilant and thus expand the points in society at which high-risk individuals could be detected and the interaction between them and the healthy population minimized.

The first such app was deployed in Zhejiang province through collaboration between Alibaba and the provincial health authority. Tencent launched a functionally equivalent app in WeChat (one social networking platform) in the city of Shenzhen. Subsequently, hundreds of health code apps were commissioned by regional governments and health authorities. Alibaba and Tencent were two major partners of local governments, given the penetration of their flagship mobile apps Alipay and WeChat, and their technological capability to manage apps processing personal data. Localized apps implemented in these two platforms have covered more than 500 cities and counties nationwide [[18], [19]].

Central government also experimented with approaches requiring less self-report data from individual users. The State Council released an alternative contact tracing app, Itinerary Card, with support from MIIT. The app uses mobile phone number as identifier and does not require self-reported data. The weakness is its single data source (location data from the three major telecom providers) and lack of data on exposure history and health status; the strength is its nationwide applicability, given interoperability among telecom operators. In its latest version, Bluetooth-based proximity tracking and integration with the national health code apps were added to extend its utility [20].

3.6. Clinical services

With policy directives repeatedly addressing the urgency of using telemedicine for COVID-19 case management and outpatient routine care, many provincial health authorities intervened and collaborated with telecommunications and digital health companies to implement provider-to-provider and client-to-provider telemedicine. In Sichuan province, the provincial health commission facilitated the collaboration with telecommunications companies to set up provider-to-provider telemedicine services that allows the telemedicine center housed in China West Hospital, a major hospital in the region, to be the hub offering a full array of COVID-19 case management services to resource-constraint healthcare facilities. The technical challenge of implementation was to rapidly deploy 4 G/5 G base stations and set up all necessary infrastructure for low-level healthcare facilities. With technical support from local branches of national telecommunications companies, the 5 G base stations was deployed in China West Hospital in 2 days, extension of 4 G/5 G base stations to 26 hospitals in another 5 days, and by 24 February, 208 health facilities were covered for virtual rounds and remote CT scans [21]. Later, the central health authority lifted the ban on initial consultations online for public hospitals. Provincial health authorities introduced flexibilities in insurance policies, waiving the cost for COVID-19 or developing interim reimbursement policies. Local health authorities expedited the registration approval process and retrofitted mobile apps to reflect flexibilities in reimbursement policies [22]. Flexible arrangements as such stimulated implementation of telemedicine at scale.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test shortage in first few months into the pandemic demanded alternative solutions for COVID-19 diagnosis. The local office of MIIT in Shanghai engaged the private sector and sourced more than 300 big data and AI products and applications to strengthen surge capacity and public health interventions with promises on funding and other incentives [23]. Health authorities in Shanghai designated prominent hospitals to test use and evaluate these applications. Competitive solutions that could prove usefulness and effectiveness would be recommended for implementation in hospitals in Wuhan. One of the hospitals collaborated with an established AI company to develop a tool using chest CT scans in COVID-19 detection and prognosis monitoring. The company's previous experience in developing China's first full-range AI system for lung cancer detection and first lung cancer database provided a strong foundation. The AI product for CT scans was launched (28 January) with 97.3% sensitivity and 99.0% specificity in typical COVID-19 pneumonic pattern detection, shortening quantitative analysis of CT imaging from hours to seconds without compromising accuracy. In less than a week, it was implemented in Wuhan. Benefiting from media coverage and more financial incentives from local governments, similar products were developed by AI startups and implemented in hundreds of hospitals nationwide [24].

4. Discussion

In this study, national policy directives and self-reported digital health interventions between late January and March 2020 yielded the following four important findings.

4.1. Policy directives stimulate private sector engagement

The development and execution of digital health policy directives between January and March 2020 conformed to a common Chinese policy process, with high-level leadership ambitions translated into concrete actions by actors lower down the system, deliberate piloting and scale-up of solutions, and national adoption of comprehensive policies following evaluation. This semi-decentralized system can catalyze widespread, innovative activity, but also creates variation, linked to regional differences, including infrastructure and capacity; political economy, market and industry structures; the maturity of digital infrastructure and specific interventions; and regulatory and other barriers, including social acceptance [[25], [26]]. It also allowed flexibilities in using policy instruments and experimentation to tighten or loosen regulation of digital health solutions. In the case of COVID-19, central policy directives trickled down into provincial and municipal policies, setting out priorities and steering activities by a wider group of digital technologists in the private sector in line with government priorities. Regional departments of science and technology, finance bureaus and other government units issued requests for digital interventions and introduced related incentives for the private sector and academia to develop interventions in priority areas. Funding modalities, incentive models, and digital solutions varied across regions.

4.2. Decentralized interventions preceded top-level introduction of binding rules

Rapid, experimental, decentrailized implementations were useful for community-level prevention during the pandemic, but they resulted in fragmentation of standards, privacy policies, data validity and risk assessment algorithms, requiring regulators to catch up. These challenges were epitomized by the health code app. Its wide use stipulated the concern and urgency for privacy protection. Though the national standard for personal information security was introduced in 2018, it was not mandated by government bodies and therefore no overarching regulatory framework was in place [27]. CAC made a timely introduction of a guidance (Table 2) outlining requirements on the collection and use of personal data for COVID-19 management. The requirements accelerated the transformation of local versions of the health code app and the conformity of local implementations in including privacy policies and informed consent. However, the introduction of privacy-protecting policies also exposed the challenge in interoperability as data from localized versions of the health code app was difficult to harmonize. Effort was made by NHC in developing a common data model and achieve technological harmonization between different versions. An interim step in pursuing cross-province interoperability was via memoranda of understanding. An early intervention of top-level planning in developing binding rules would have avoided much of the localization and ensured greater protection of privacy and security.

4.3. Digital health interventions benefitted from pre-outbreak digital landscape, interim incentives, and regulatory flexibility

Digital health experienced robust growth in a largely enabling policy environment before the outbreak. Information infrastructure strengthening and health service digitization gained importance in China's health system reforms since 2009 [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39]. Supporting policies focusing on implementing electronic health records and health information exchange, and, more recently, developing Internet-based services, and health big data and AI applications [[40], [41]], as well as increased non-state investment, gave the COVID-19 response a head start [42].

Health Code-like interventions for public health response may be new to the health system, but its rapid implementation benefited from the whole society's digitization before the pandemic, and the practice of digital technology companies offering support to governments at all levels to design, develop, operate and promote digitized public services [[43], [44]]. Super apps like Alipay and WeChat had been one major channel for authorities to offer public services before the creation of Health code app. The pervasiveness of these digital platforms also lowered the barrier for user acceptance of the Health Code app.

The use of AI technologies was not specifically addressed by national policy directives. This could be partially explained by the pre-pandemic landscape where piloting, effectiveness evaluation and regulation of AI software as medical devices were all in early stages where much uncertainty existed [45]. But regulators did not step in when AI interventions for COVID-19 made its way in to provide support. AI systems for CT scans were implemented to assist COVID-19 detection where polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests alone could not meet the demand [46] in hospitals for emergency use, with little debate over clinical effectiveness or discouragement from regulators throughout February. In March, when the immense pressure on the health system decreased, the regulator issued guidelines for AI companies to apply for premarket evaluation and approval.

Provider-to-provider telemedicine was an integral part of China's ten-year health system reform to improve access to quality care in rural areas and primary care settings [[47], [48]]. Prior to the outbreak, more than 13,000 health facilities across the country had some form of telemedicine system in place. Retrofitting telemedicine for COVID-19 was easier than to begin with nothing.

Before COVID-19, client-to-provider telemedicine for outpatient and primary care service in public hospitals was under cautious planning and piloting. Policy directives necessitated the regulation of private providers and encouraged public hospitals with “Internet hospital” credentials to provide non-initial consultations online. As our findings suggested, COVID-19 accelerated the process of making changes and introduced interim flexibilities into the space.

4.4. Patterns of digital health interventions may reinforce disparities across different levels of healthcare facilities

During the health system reform, China emphasized digitizing and reforming public hospitals, leading to disparities between hospitals and lower-level primary care facilities in digital infrastructure and budget resources [[49], [50]]. Interventions built on AI technologies would be difficult to be adapted and implemented in resource-constrained environments due to infrastructure and other constraints. Use of AI for CT scans may be more useful in resource-constrained environments where many patients present moderate-severe clinical features and a high pre-test probability of COVID-19 than in managing an asymptomatic patient population [51]. Yet such environments have less chance to sustain investment for an AI system.

Despite all pre-COVID-19 achievements made in telemedicine infrastructure across different levels of healthcare facilities and that resource-constraint primary care facilities were receiving remote assistance during COVID-19, consequential investment in retrofitting telemedicine for more service delivery are more likely to happen in higher-level hospitals. Expanded digital access to more and better health services from reputable hospitals may further divert people from primary care facilities and reinforce existing disparities.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this research is to analyze the impact of policy instruments to promote digital health interventions for COVID-19 containment and to identify the contextual factors and mechanisms associated during the early stage of COVID-19 in China. A distribution correlation between the policy themes and digital health interventions was proven to be consistent under the APSED III framework. We have further analyzed major national policies which mobilized the private sector on different fronts fighting against COVID-19, mapped consequentially emerged digital health interventions, presented and summarized case studies to highlight contextual factors. The contextual factors include booming digital health landscape before COVID-19, agility of the public sector in realizing and adopting the benefits of digital health technologies, and established pathway of policy directives influencing the industry, which had not been previously prominent in the literature on digital health innovations during the pandemic. These critical contextual factors shaped key mechanisms, including the introduction of regulatory flexibilities and incentives. These mechanisms catalyzed the abundance of digital health response to COVID-19 to strengthen emergency response, public health response, and clinical services.

While China's response showcased a wide range of solutions, there are effectiveness and efficiency implications, including duplication of efforts, divergence in standards and challenges of interoperability. As digital solutions are rolled out, the national experience also shows the need to balance speed and privacy considerations. Further performance evaluations of digital interventions in effectiveness, efficiency and equity are needed. The analysis also extended the disucssion about how rapid, decentralized innovation processes can be streamlined to overcome these challenges in the future, and how extraordinary periods can drive changes supporting longer-term goals of strengthening health security and universal health coverage .

Disclosure statement

The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Schwamm LH, Erskine A, Licurse A. A digital embrace to blunt the curve of COVID19 pandemic. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:64. doi: 10.1038/s41746-020-0279-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pérez Sust P, Solans O, Fajardo JC. Turning the crisis into an opportunity: digital health strategies deployed during the COVID-19 outbreak. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e19106. doi: 10.2196/19106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loeb AE, Rao SS, Ficke JR. Departmental experience and lessons learned with accelerated introduction of telemedicine during the COVID-19 crisis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(11):e469–e476. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamel Boulos MN, Geraghty EM. Geographical tracking and mapping of coronavirus disease COVID-19/severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) epidemic and associated events around the world: how 21st century GIS technologies are supporting the global fight against outbreaks and epidemics. Int J Health Geogr. 2020;19(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12942-020-00202-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asia Pacific strategy for emerging diseases and public health emergencies: advancing implementation of the International Health Regulations . World Health Organization; 2005. Regional office for the western pacific.https://iris.wpro.who.int/handle/10665.1/13654 2017. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization; 2019. Non-pharmaceutical public health measures for mitigating the risk and impact of epidemic and pandemic influenza.https://www.who.int/influenza/publications/public_health_measures/publication/en/ Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China; 2020. Notice of the general office of the national health commission on strengthening information support to novel coronavirus epidemic prevention and control.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/gon11/202002/5ea1b9fca8b04225bbaad5978a91f49f.shtml Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China; 2020. Notice on effective online diagnosis, treatment and consultation services in the prevention and control of the epidemic.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/ec5e345814e744398c2adef17b657fb8.shtml Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The State Council of the People's Republic of China; 2020. A notice on the protection of personal information and the use of big data to support joint prevention and control.http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-02/10/content_5476711.htm Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China; 2020. Notice on follow-up of COVID-19 discharged patients.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/0572eef930d5441c96181c44a1fca878.shtml Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China; 2020. Notice on conducting national teleconferencing of COVID-19 critically ill patients at the national telemedicine and internet medical center.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7658/202002/69b24672365043eebc379c8bab30c90d.shtml Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People's Republic of China; 2020. Notice on the application of next-generation information technology to support epidemic prevention and control and economic recovery.http://www.miit.gov.cn/n1146295/n1652858/n1652930/n3757022/c7683415/content.html Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Medical Insurance Administration of the People's Republic of China; 2020. Guidelines on promoting internet plus health care services during COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control.http://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2020/3/2/art_37_2750.html Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China; 2020. Notice on issuing guidelines on informatization construction and application of covid-19 epidemic prevention and control in communities.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jws/s7882g/202003/8c5db796fea24a62ba4d1242b353e140.shtml Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China; 2020. Notice on the issuance of the health management plan for COVID-19 discharged patients (Trial)http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653pd/202003/056b2ce9e13142e6a70ec08ef970f1e8.shtml Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 16.COSMOPlat launched online platform for COVID-19 resource matching. 2020. Available from https://www.cosmoplat.com/news/detail/?newsid=4497.

- 17.How China is using QR code apps to contain Covid-19. Technode, 2020. Available from https://technode.com/2020/02/25/how-china-is-using-qr-code-apps-to-contain-covid-19/.

- 18.Alipay health code has covered public facility use cases in more than 200 cities. Sina News, 2020. Available from https://finance.sina.com.cn/money/bank/bank_hydt/2020-02-26/doc-iimxyqvz5693418.shtml.

- 19.Tencent epidemic prevention and health code has broken 1.6 billion times. Tencent News, 2020. Available from https://tech.qq.com/a/20200310/016327.htm.

- 20.People's Daily online; 2020. Travel card 2.0 goes online with bluetooth “black technology” to help normalize epidemic prevention and control.http://finance.people.com.cn/n1/2020/0511/c1004-31704810.html?from=timeline&isappinstalled=0 Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xinhua News Agency; 2020. Upgrading provider-to-provider telemedicine: 5G plus tele-radiology for COVID-19 diagnosis.http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020-03/04/c_1125662616.htm Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 22.People's Daily; 2020. Sichuan health insurance mobile app launched online reimbursement for telemedicine.http://sc.people.com.cn/n2/2020/0302/c345509-33841667.html Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shanghai Economic and Information Technology Commission; 2020. Notice on soliciting the first batch of new technologies, products and applications for novel coronavirus infection prevention and control.http://www.shanghai.gov.cn/nw12344/20200813/0001-12344_63479.html Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yitu AI. People’s Daily; 2020. AI for CT scan.http://sh.people.com.cn/n2/2020/0225/c396182-33827929.html Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heilmann Sebastian. Harvard University Asia Center.; 2011. Mao's invisible hand: the political foundations of adaptive governance in China. Available from. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Husain L. Policy experimentation and innovation as a response to complexity in China's management of health reforms. Global Health. 2017;13(1):54. doi: 10.1186/s12992-017-0277-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cyberspace Administration of China; 2018. National information security standardization technical committee. personal information security standards to fill the gap of regulations.http://www.cac.gov.cn/2018-05/14/c_1122776896.htm Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The State Council of the People's People's Republic of China; 2018. Opinions on deepening the reform of the medical and health care system.http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2009-04/06/content_1278721.htm Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China; 2010. Notice of the pilot work on electronic medical records.http://www.gov.cn/gzdt/2010-10/14/content_1722508.htm Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 30.The State Council of the People's Republic of China; 2015. Guidelines on actively promoting the “Internet plus” action.http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-07/04/content_10002.htm Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 31.The State Council of the People's Republic of China; 2015. The issuance of the platform to promote the development of big data.http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-09/05/content_10137.htm Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Science and Technology, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Cyberspace Administration of the CPC Central Committee of the People's Republic of China; 2016. Three-year action plan for “Internet plus” artificial intelligence.http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-05/23/content_5075944.htm Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 33.The State Council of the People's Republic of China; 2016. Guidelines on promoting and standardizing the application and development of big data in health care.http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-06/24/content_5085091.htm Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 34.The State Council of the People's Republic of China; 2016. Outline of a healthy China 2030 plan.http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2016-10/25/content_5124174.htm Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China; 2017. The issuance of the “13th five-year” national population health information development plan notice.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/s10741/201702/ef9ba6fbe2ef46a49c333de32275074f.shtml Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 36.The State Council of the People's Republic of China; 2017. The issuance of a new generation of artificial intelligence development plan.http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2017-07/20/content_5211996.htm Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 37.The State Council of the People's Republic of China; 2018. Opinions on promoting the development of “Internet plus healthcare.http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2018-04/28/content_5286645.htm Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China; 2018. Notice on further promoting the information infrastructure of health institutions with electronic medical records.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7659/201808/a924c197326440cdaaa0e563f5b111c2.shtml Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Health Commission, Bureau of traditional Chinese medicine of the People's Republic of China; 2018. The issuance of three documents including the measures for the administration of online diagnosis and treatment (trial)http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2019/content_5358684.htm Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang L, Wang H, Li Q. Big data and medical research in China. BMJ. 2018;360:j5910. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kong X, Ai B, Kong Y. Artificial intelligence: a key to relieve China’s insufficient and unequally-distributed medical resources. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11(5):2632–2640. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The World Bank; 2019. Innovative China: new drivers of growth.http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/833871568732137448/Innovative-China-New-Drivers-of-Growth Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hswen Y, Brownstein JS, Liu J. Use of a Digital health application for influenza surveillance in China. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(7):1130–1136. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Su K, Xu L, Li G. Forecasting influenza activity using self-adaptive AI model and multi-source data in Chongqing. China EBioMedicine. 2019;47:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luo H, Xu G, Li C. Real-time artificial intelligence for detection of upper gastrointestinal cancer by endoscopy: a multicentre, case-control, diagnostic study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(12):1645–1654. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30637-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He J, Baxter SL, Xu J. The practical implementation of artificial intelligence technologies in medicine. Nat Med. 2019;25(1):30–36. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0307-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao G, Huang H, Yang F. The progress of telestroke in China. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2017;2(3):168–171. doi: 10.1136/svn-2017-000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang TT, Li JM, Zhu CR. Assessment of utilization and cost-effectiveness of telemedicine program in western regions of China: a 12-year study of 249 hospitals across 112 Cities. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(11):909–920. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2015.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang T, Xu Y, Ren J. Inequality in the distribution of health resources and health services in China: hospitals versus primary care institutions. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0543-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li X, Lu J, Hu S. The primary health-care system in China. Lancet. 2017;390(10112):2584–2594. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rubin GD, Ryerson CJ, Haramati LB. The role of chest imaging in patient management during the covid-19 pandemic: a multinational consensus statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2020;296(1):172–180. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]