Abstract

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a chronic genetic disease that requires lifelong therapy and monitoring. Low drug adherence and poor monitoring may lead to an increase in morbidities and low quality of life. In the era of digital technology, various mobile health (mHealth) apps are being tested for their potential in increasing drug adherence in patients with SCD. We herewith discuss the applicability and feasibility of these mHealth apps for the management of SCD in India.

Keywords: sickle cell disease, drug adherence, mHealth, India

Background

In recent years, a revolution in information technologies has greatly influenced health care practices under the broad definition of digital health. Digital health practices are becoming highly adaptable in both developed and developing countries [1]. Moreover, with the increasing use of smartphones, smart watches, and artificial intelligence–based devices, mobile health (mHealth) is expected to define the standard of health care delivery across the globe. Specifically, mHealth apps can be used to increase disease awareness, increase drug adherence, provide cognitive behavioral therapies, and track health care delivery [2-5]. There are more than 325,000 mHealth apps available for Android and Apple smartphones [6]. Various mHealth apps have been clinically tested for their effect on compliance for many chronic diseases worldwide [7-11] and there are mounting indications that support the feasibility and applicability of mHealth interventions for better compliance in managing chronic diseases in pediatric patients as well. During the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, mHealth has emerged as a silver bullet, not only for teleconsultations and telemonitoring of patients with chronic diseases, but also for increasing health care delivery in remote areas [12-14].

Sickle Cell Disease: A Life-threatening and Highly Morbid Disorder

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic and chronic ailment, highly prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, the Mediterranean region, India, and parts of Central and South America. Globally, more than 300,000 children are born each year with SCD and three countries (Nigeria, India, and the Democratic Republic of Congo) bear about half of the global burden [15]. Patients with SCD often present with acute complications (eg, bone pain crisis, acute abdominal pain, acute chest syndrome, visceral sequestration crisis, aplastic crisis, acute anemia, cerebrocardiovascular complications, priapism). Chronic morbidities in SCD (eg, chronic pain syndromes, immunological and infectious complications, chronic lung disease, hepatobiliary complications, renal complications, leg ulcer, musculoskeletal complications, and psychosocial or psychiatric issues) are often encountered [16].

The under-five mortality of SCD varies significantly depending on the availability of health care facilities and infrastructure. For example, in low-income countries with poor access to health care services, mortality can reach up to 90% [15]. There is now growing evidence that continuous interventions through disease-modifying drugs such as hydroxyurea and prophylactic antibiotics can decrease morbidities and increase life expectancy, thereby leading to increased health-related quality of life and reduced health burden [17-22]. However, the sustainability of drug adherence is a major challenge in public health, as an average of about 50% of patients with chronic illness (including SCD) do not adhere to proper treatment in developed countries [23,24]. Furthermore, the prevalence of medication nonadherence is much higher in developing countries due to their relative scarcity and inequities of health care resources in comparison to developed nations [25-27]. Low drug adherence not only is associated with increased morbidity and poor health-related quality of life for patients, but also increases burden on the health economy and increases health care utilization in a country setting.

Various factors govern drug adherence, including delivery of health care services, economic situation, and cultural factors of patients [28]. Behavioral factors like forgetfulness, inappropriate time management, lack of awareness of disease, and fear of drugs pose additional barriers to drug adherence [29-31]. It has been observed that parents of patients with SCD with mild symptoms are less willing to accept the risk associated with taking hydroxyurea, particularly with regard to the long-term side effects, which include birth defects and cancer [29]. Therefore, patients with mild symptoms are more unwilling to take medications. In addition, patients with poor drug adherence can experience a mild-to-moderate medication response, causing frustration in both patients and their parents, which further leads to increased drug nonadherence.

Low drug adherence in SCD is also a major issue in India, where the majority of patients with SCD belong to scheduled communities (both the scheduled caste and scheduled tribes) [32,33], who face many barriers in accessing quality health care services. The scheduled caste and scheduled tribes are groups of people scheduled in the Constitution of India on the basis of economic, social, and educational disadvantage. Tribes are the most marginalized communities and mostly live in hard-to-reach remote hilly and forested areas. Many of the tribal communities are still dependent upon hunting and gathering and primitive agricultural practices. Poor accessibility, social disconnection, inconvenient timing, longer waiting times in government health care facilities, and poor economic conditions are some of the major roadblocks to accessing quality health care services in tribal areas in India [34]. Further, due to the different environments and terrains in which tribes live, inequalities in sociocultural behavior, and lack of participation, a universal design of health care services becomes inappropriate in tribal communities. Various nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)—such as SEARCH (in Gadchiroli, Maharashtra, India) [35], MAHAN (Melghat, Maharashtra) [36], Seva Rural (Jhagadia, Gujarat) [37], Jan Swasthya Sahyog (Ganiyari, Chhattisgarh) [38], and ASHWINI (Gudalur, Tamil Nadu) [39]—have developed different locally appropriate customized models for providing better health care services in hard-to-reach remote tribal areas.

With regard to SCD, various control programs have been in operation in India for an extended period of time. However, due to the lack of an organizational referral system and standard treatment guidelines for the management of SCD, most of these programs are limited to the screening of patients [40]. It has been observed that most patients seek treatment only when they have an acute sickle cell crisis. Moreover, the low accessibility and affordability of drugs is a major obstacle in the management of SCD in Indian tribes [41,42].

The Role of mHealth in SCD Management: Indian Context

Disease interventions using mHealth have been tried for several diseases in tribal and rural India. For example, in a recent clinical trial, accredited social health activists (ASHAs) who used an mHealth app (ImTecho) as a job aid were able to provide better maternal and child health services in tribal areas in the state of Gujarat [43]. Similarly, presumptive tuberculosis referrals increased when rural health care providers used mHealth technology in tribal areas of Khuntu District of Jharkhand state [44]. Based on different models, a framework of digital health for increasing referrals, monitoring patients, and increasing the accessibility of malaria drugs in rural areas has been suggested [45]. A similar approach can be adopted for increasing drug availability and improving the referral system for SCD as well. Intervention measures (eg, sending reminders, allowing pain and symptom reporting, enabling self-management, and providing cognitive behavioral therapy) through mHealth apps for increasing drug adherence for SCD have been tested in several parts of the globe and have shown promising results in terms of disease outcome [46-48]. In addition, self-management practices in SCD have been found to be increased by the use of mHealth apps. However, no such intervention measures have previously been tried for patients with SCD in India. Considering SCD in India is mostly prevalent in scheduled communities living in rural and hard-to-reach areas, mHealth might be especially useful for SCD management. This is because access to health care services in hard-to-reach rural and forested areas remains meagre due to poor local transport systems. In these circumstances, mHealth apps can be used to improve the referral system in inaccessible areas by increasing knowledge among ASHAs, community health workers, and the traditional healers in the tribal communities.

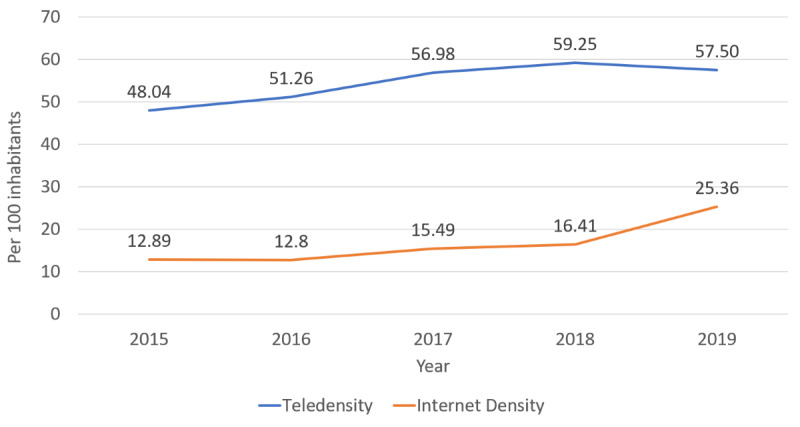

Is it practically feasible to use mHealth apps for patients with SCD in India? Several broad factors might limit the adoption of mHealth in patients with SCD in India (Textbox 1). One of the major roadblocks is poor internet availability in rural India. Although the number of mobile and internet users in rural areas is said to have increased substantially in recent years (Figure 1) [49], by the year 2018, just 14.9% of rural households had internet access [50]. Furthermore, mobile and internet connectivity are considered poor in hard-to-reach forested areas, which could hinder access to mHealth apps. In addition, the poor socioeconomic status of tribes further limits their ability to sustain the cost of smartphones and internet data plans for a longer duration. Moreover, a low level of digital literacy among rural and tribal people also impedes the usability of mHealth apps. Apart from this, people living in rural areas, especially tribes, have their own social beliefs and customs that are different from other populations in India, thereby limiting the use of such mHealth apps due to hesitation and stigma. In addition, privacy and cybersecurity issues related to the online use of any mobile app (including mHealth) may be a concern of people who are inadequately digitally literate and economically disadvantaged. Further, most mHealth apps require manual use; therefore, after a certain time period, patient engagement may decrease. Therefore, not only the feasibility, but also the long-term sustainability of mHealth apps in patients with SCD residing in rural and tribal areas is presently uncertain.

Utility of and roadblocks to mobile health apps for the management of sickle cell disease in India.

Utility

Enhancement of referral system

Strengthens public health delivery

Augments drug adherence

Creates disease awareness

Improves self-management abilities during a primary sickle cell crisis

Roadblocks

Low digital literacy

Poor telecommunication connectivity in remote areas

Cost of data plans for economically disadvantaged communities

Digital privacy and data security

Figure 1.

Telephone and internet density in rural India.

In spite of the above mentioned barriers to the use of mHealth apps in India, there is a light at the end of the tunnel. Based on the applicability of disease management and growing digitalization in India, measures should be taken to implement mHealth technology for SCD interventions with locally appropriate customized solutions. For example, mHealth apps with artificial intelligence that require little manual intervention may be helpful for patients with low digital literacy. In addition, for better management of SCD, user-specific customizable mHealth apps should be made, not only for increasing drug adherence but also for informing the patient about disease precipitating factors through daily activity monitoring and environmental conditions, thereby reducing acute crises. Such customization requires field-based and need-based approaches through direct inputs from patients as well as their caregivers in terms of expectations, needs, and experiences in combatting SCD to improve short-term engagement. Once such customized and user-friendly mHealth apps are in use by patients, regular feedback in terms of usage, technicality, and user-friendliness can be obtained from users at regular intervals for long-term sustainability. Furthermore, considering the poor economic conditions of many rural and tribal people, the provision of incentives (in term of free smartphones and internet data packs) may also serve as a boon for increased sustainability of mHealth apps for SCD intervention in India. In addition, encouragement through community engagement as part of a drive for increased use of mHealth apps could prove useful, as could the involvement of health ambassadors (eg, ASHAs, community health workers, community leaders, traditional healers, and/or adult SCD champions). These health ambassadors can be trained on the operation and use of mHealth apps, who in turn can train patients with SCD and their caregivers to use mHealth apps effectively. Moreover, socioeducational drives for increasing digital literacy among patients with SCD residing in rural and tribal areas can prove highly rewarding in terms of effective management. Furthermore, studies aiming to evaluate the cost effectiveness of mHealth interventions in improving health care delivery and drug adherence for patients with SCD living in remote areas are needed to assess the sustainability of such interventions.

The Way Forward

In 2016, the Indian government aimed to increase the accessibility of hydroxyurea in district hospitals located in high-prevalence areas and issued guidelines for the prevention and control of hemoglobinopathies [51]. However, due to implementation gaps, the program could not be initiated in the majority of states, particularly in tribal areas [40]. Recently, a draft policy was prepared, which advocates for the improvement of SCD treatment centers in all districts and ensures a free supply of hydroxyurea and penicillin to low-income patients [52]. Furthermore, the recent introduction of the Ayushman Bharat scheme promulgating universal health coverage ensures free treatment of low-income patients admitted in hospitals [53]. For the successful implementation of these schemes, there is a pressing need for the development of an organizational referral system and a strong communication system for increasing awareness about diseases and the treatment and monitoring of patients. In this context, mHealth can appropriately establish itself as a game changer in the management of SCD in India. Therefore, the introduction of mHealth for SCD has huge potential in terms of enhancing health care delivery and management, and providing a better quality of life to patients globally, including in India. However, the feasibility, acceptability, and sustainability of such mHealth apps for the management of SCD in India is uncertain at present. For this, the keys to success are the following: a strong inclination from the government through health policy reform for socially and economically marginalized populations living in rural and hard-to-reach areas; a significant investment in infrastructure development for the strengthening of mobile and internet connectivity in these areas; and promulgation of digital literacy using intersectoral coordination and public-private partnerships in rural and tribal populations. The recent introduction of the Prime Minister’s Digital India Movement and the Prime Minister’s Rural Digital Literacy Movement—with a view to ensuring the availability of cost-effective high-speed internet to every citizen and empowering the rural population in the use of digital technologies, including the marginalized scheduled castes/tribes and differently abled persons—is one such welcome move in this direction. Furthermore, with advances in digital technologies, a reduction in the cost of internet data plans and a higher penetration of mobile and internet connectivity in rural and hard-to-reach areas are expected in the future. In light of the above developments, the future of mHealth in India seems bright, and this will lead to a better prognosis and improved health-related quality of life for patients with SCD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Secretary, Department of Health Research and the Director General, Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) for providing encouragement and facilities. The authors are also thankful to Dr Nishant Saxena and Dr Anil Kumar Verma, ICMR-NIRTH, Jabalpur, for providing valuable suggestions. Critical comments from three anonymous reviewers helped us improve the manuscript. The manuscript has been approved by the Publication Screening Committee of ICMR-NIRTH, Jabalpur, and assigned the number ICMR-NIRTH/PSC/06/2021.

Abbreviations

- ASHA

accredited social health activist

- mHealth

mobile health

- SCD

sickle cell disease

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Radbron E, Wilson V, McCance T, Middleton R. The Use of Data Collected From mHealth Apps to Inform Evidence-Based Quality Improvement: An Integrative Review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2019 Feb;16(1):70–77. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hossain MM, Tasnim S, Sharma R, Sultana A, Shaik AF, Faizah F, Kaur R, Uppuluri M, Sribhashyam M, Bhattacharya S. Digital interventions for people living with non-communicable diseases in India: A systematic review of intervention studies and recommendations for future research and development. Digit Health. 2019;5:2055207619896153. doi: 10.1177/2055207619896153. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2055207619896153?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu H, Long H. The Effect of Smartphone App-Based Interventions for Patients With Hypertension: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2020 Oct 19;8(10):e21759. doi: 10.2196/21759. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/10/e21759/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabi K, Randhawa AS, Choi F, Mithani Z, Albers F, Schnieder M, Nikoo M, Vigo D, Jang K, Demlova R, Krausz M. Mobile Apps for Medication Management: Review and Analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2019 Sep 11;7(9):e13608. doi: 10.2196/13608. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2019/9/e13608/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Psihogios AM, Stiles-Shields C, Neary M. The Needle in the Haystack: Identifying Credible Mobile Health Apps for Pediatric Populations during a Pandemic and beyond. J Pediatr Psychol. 2020 Nov 01;45(10):1106–1113. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa094. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33068424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larson RS. A Path to Better-Quality mHealth Apps. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2018 Jul 30;6(7):e10414. doi: 10.2196/10414. http://mhealth.jmir.org/2018/7/e10414/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Y, Chen H, Qazi H, Morita PP. Intervention and Evaluation of Mobile Health Technologies in Management of Patients Undergoing Chronic Dialysis: Scoping Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2020 Apr;8(4):e15549. doi: 10.2196/15549. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/4/e15549/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kompala T, Neinstein AB. Telehealth in type 1 diabetes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2021 Feb 01;28(1):21–29. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agarwal RK, Sedai A, Ankita K, Parmar L, Dhanya R, Dhimal S, Sriniwas R, Gowda A, Gujjal P, Jain S, Ramaiah JD, Jali S, Tallur NR, Ramprakash S, Faulkner L. Information Technology-Assisted Treatment Planning and Performance Assessment for Severe Thalassemia Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Observational Study. JMIR Med Inform. 2019 Jan 23;7(1):e9291. doi: 10.2196/medinform.9291. https://medinform.jmir.org/2019/1/e9291/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi H, Van Riper M. mHealth Family Adaptation Intervention for Families of Young Children with Down Syndrome: A Feasibility Study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2020;50:e69–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsey WA, Heidelberg RE, Gilbert AM, Heneghan MB, Badawy SM, Alberts NM. eHealth and mHealth interventions in pediatric cancer: A systematic review of interventions across the cancer continuum. Psychooncology. 2020 Jan;29(1):17–37. doi: 10.1002/pon.5280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doraiswamy S, Abraham A, Mamtani R, Cheema S. Use of Telehealth During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Dec 01;22(12):e24087. doi: 10.2196/24087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrews E, Berghofer K, Long J, Prescott A, Caboral-Stevens M. Satisfaction with the use of telehealth during COVID-19: An integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2020 Nov;2:100008. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnsa.2020.100008. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2666-142X(20)30007-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badawy SM, Radovic A. Digital Approaches to Remote Pediatric Health Care Delivery During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Existing Evidence and a Call for Further Research. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2020 Jun 25;3(1):e20049. doi: 10.2196/20049. doi: 10.2196/20049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piel FB, Hay SI, Gupta S, Weatherall DJ, Williams TN. Global burden of sickle cell anaemia in children under five, 2010-2050: modelling based on demographics, excess mortality, and interventions. PLoS Med. 2013 Jul;10(7):e1001484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001484. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piel FB, Steinberg MH, Rees DC. Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017 Apr 20;376(16):1561–1573. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1510865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Candrilli SD, O'Brien SH, Ware RE, Nahata MC, Seiber EE, Balkrishnan R. Hydroxyurea adherence and associated outcomes among Medicaid enrollees with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2011 Mar;86(3):273–7. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21968. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Badawy SM, Thompson AA, Lai J, Penedo FJ, Rychlik K, Liem RI. Adherence to hydroxyurea, health-related quality of life domains, and patients' perceptions of sickle cell disease and hydroxyurea: a cross-sectional study in adolescents and young adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017 Jul 05;15(1):136. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0713-x. https://hqlo.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12955-017-0713-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badawy SM, Thompson AA, Holl JL, Penedo FJ, Liem RI. Healthcare utilization and hydroxyurea adherence in youth with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2018;35(5-6):297–308. doi: 10.1080/08880018.2018.1505988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh KE, Cutrona SL, Kavanagh PL, Crosby LE, Malone C, Lobner K, Bundy DG. Medication adherence among pediatric patients with sickle cell disease: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2014 Dec;134(6):1175–83. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0177. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=25404717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loiselle K, Lee JL, Szulczewski L, Drake S, Crosby LE, Pai ALH. Systematic and Meta-Analytic Review: Medication Adherence Among Pediatric Patients With Sickle Cell Disease. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016 May;41(4):406–18. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv084. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26384715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shih S, Cohen LL. A Systematic Review of Medication Adherence Interventions in Pediatric Sickle Cell Disease. J Pediatr Psychol. 2020 Jul 01;45(6):593–606. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. [2020-12-28]. https://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandez-Lazaro CI, García-González JM, Adams DP, Fernandez-Lazaro D, Mielgo-Ayuso J, Caballero-Garcia A, Moreno Racionero F, Córdova A, Miron-Canelo JA. Adherence to treatment and related factors among patients with chronic conditions in primary care: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2019 Sep 14;20(1):132. doi: 10.1186/s12875-019-1019-3. https://bmcfampract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-019-1019-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santra G. Assessment of adherence to cardiovascular medicines in rural population: An observational study in patients attending a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Pharmacol. 2015;47(6):600–4. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.169573. http://www.ijp-online.com/article.asp?issn=0253-7613;year=2015;volume=47;issue=6;spage=600;epage=604;aulast=Santra. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saqlain M, Riaz A, Malik MN, Khan S, Ahmed A, Kamran S, Ali H. Medication Adherence and Its Association with Health Literacy and Performance in Activities of Daily Livings among Elderly Hypertensive Patients in Islamabad, Pakistan. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019 May 18;55(5):163. doi: 10.3390/medicina55050163. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=medicina55050163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nonogaki A, Heang H, Yi S, van Pelt M, Yamashina H, Taniguchi C, Nishida T, Sakakibara H. Factors associated with medication adherence among people with diabetes mellitus in poor urban areas of Cambodia: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2019 Nov 19;14(11):e0225000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225000. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McQuaid EL, Landier W. Cultural Issues in Medication Adherence: Disparities and Directions. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 Feb;33(2):200–206. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4199-3. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29204971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Badawy SM, Thompson AA, Liem RI. Beliefs about hydroxyurea in youth with sickle cell disease. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2018 Sep;11(3):142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2018.01.001. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1658-3876(18)30002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Badawy SM, Shah R, Beg U, Heneghan MB. Habit Strength, Medication Adherence, and Habit-Based Mobile Health Interventions Across Chronic Medical Conditions: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Apr 28;22(4):e17883. doi: 10.2196/17883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Badawy SM, Thompson AA, Liem RI. Technology Access and Smartphone App Preferences for Medication Adherence in Adolescents and Young Adults With Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016 May;63(5):848–52. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hockham C, Bhatt S, Colah R, Mukherjee MB, Penman BS, Gupta S, Piel FB. The spatial epidemiology of sickle-cell anaemia in India. Sci Rep. 2018 Dec 06;8(1):17685. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36077-w. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36077-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colah R, Mukherjee M, Ghosh K. Sickle cell disease in India. Curr Opin Hematol. 2014 May;21(3):215–23. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Narain JP. Health of tribal populations in India: How long can we afford to neglect? Indian J Med Res. 2019 Mar;149(3):313–316. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_2079_18. http://www.ijmr.org.in/article.asp?issn=0971-5916;year=2019;volume=149;issue=3;spage=313;epage=316;aulast=Narain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bang AT, Reddy HM, Deshmukh MD, Baitule SB, Bang RA. Neonatal and infant mortality in the ten years (1993 to 2003) of the Gadchiroli field trial: effect of home-based neonatal care. J Perinatol. 2005 Mar;25 Suppl 1:S92–107. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Report of MAHAN Trust 1997-2019. [2020-12-28]. https://www.mahantrust.org/policy-changes.

- 37.Shah SP, Shah P, Desai S, Modi D, Desai G, Arora H. Effectiveness and Feasibility of Weekly Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation to Adolescent Girls and Boys through Peer Educators at Community Level in the Tribal Area of Gujarat. Indian J Community Med. 2016;41(2):158–61. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.173498. http://www.ijcm.org.in/article.asp?issn=0970-0218;year=2016;volume=41;issue=2;spage=158;epage=161;aulast=Shah. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jain Y, Kataria R, Patil S, Kadam S, Kataria A, Jain R, Kurbude R, Shinde S. Indian J Med Res. 2015 May;141(5):663–72. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.159582. http://www.ijmr.org.in/article.asp?issn=0971-5916;year=2015;volume=141;issue=5;spage=663;epage=672;aulast=Jain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nimgaonkar V, Krishnamurti L, Prabhakar H, Menon N. Comprehensive integrated care for patients with sickle cell disease in a remote aboriginal tribal population in southern India. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014 Apr;61(4):702–5. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geethakumari K, Kusuma YS, Babu BV. Beyond the screening: The need for health systems intervention for prevention and management of sickle cell disease among tribal population of India. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2021 Mar;36(2):236–243. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jain D, Lothe A, Colah R. Sickle Cell Disease: Current Challenges. J Hematol Thrombo Dis. 2015;03(06):224. doi: 10.4172/2329-8790.1000224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Odame I, Jain D. Indian J Med Res. 2020 Jun;151(6):505–508. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_2064_20. http://www.ijmr.org.in/article.asp?issn=0971-5916;year=2020;volume=151;issue=6;spage=505;epage=508;aulast=Odame. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Modi D, Dholakia N, Gopalan R, Venkatraman S, Dave K, Shah S, Desai G, Qazi SA, Sinha A, Pandey RM, Anand A, Desai S, Shah P. mHealth intervention "ImTeCHO" to improve delivery of maternal, neonatal, and child care services-A cluster-randomized trial in tribal areas of Gujarat, India. PLoS Med. 2019 Oct;16(10):e1002939. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002939. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chadha S, Trivedi A, Nagaraja SB, Sagili K. Using mHealth to enhance TB referrals in a tribal district of India. Public Health Action. 2017 Jun 21;7(2):123–126. doi: 10.5588/pha.16.0080. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28695085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nema S, Verma AK, Tiwari A, Bharti PK. Digital Health Care Services to Control and Eliminate Malaria in India. Trends Parasitol. 2021 Feb;37(2):96–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Badawy SM, Thompson AA, Liem RI. Technology Access and Smartphone App Preferences for Medication Adherence in Adolescents and Young Adults With Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016 May;63(5):848–52. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Badawy SM, Cronin RM, Hankins J, Crosby L, DeBaun M, Thompson AA, Shah N. Patient-Centered eHealth Interventions for Children, Adolescents, and Adults With Sickle Cell Disease: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2018 Jul 19;20(7):e10940. doi: 10.2196/10940. https://doi.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hankins JS, Shah N. Tackling adherence in sickle cell disease with mHealth. Lancet Haematol. 2020 Oct;7(10):e713–e714. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Economics Research Unit, Department of Telecommunications, Ministry of Communications, Government of India Telecom Statistics India 2019. [2020-12-28]. https://dot.gov.in/sites/default/files/Telecom%20Statistics%20India-2019.pdf?download=1.

- 50.Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India Household Social Consumption on Education in India. NSS 75th Round report. [2020-12-28]. http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/Report_585_ 75th_round_Education_final_1507_0.pdf.

- 51.National Health Mission, Ministry of Heath and Family Welfare, Government of India Prevention and Control of Hemoglobinopathies in India - Thalassemias, Sickle Disease and Other Variant Hemoglobins. Guidelines on Hemoglobinopathies in India. [2020-12-28]. https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/RBSK/Resource_Documents/Guidelines_on_Hemoglobinopathies_in%20India.pdf.

- 52.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India Draft Policy for Prevention and Control of Hemoglobinopathies - Thalassemia, Sickle Cell Disease and Variant Hemoglobins in India. [2020-12-28]. https://www.nhp.gov.in/NHPfiles/1.pdf.

- 53.Bhargava B, Paul Vk. Informing NCD control efforts in India on the eve of Ayushman Bharat. Lancet. 2018 Sep 11;:S0140-6736(18)32172-X. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32172-X. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140-6736(18)32172-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]