Abstract

The present study attempted to analyse human papillomavirus (HPV) genotype distribution and its association with cervical cytology results in women in western China. The present retrospective analysis was performed in 1089 female outpatients with a positive HPV test result who had undergone a cervical cytology test at the gynaecological clinic, West China Second Hospital, Sichuan University, China, between January 2014 and December 2016. Of the 1089 patients with HPV infection, multiple HPV genotypes were detected in 220 patients (20.20%). Among the 1368 HPV genotypes detected, 1145 (83.70%) were high-risk subtypes. The most common genotypes were HPV-52 (18.64%), HPV-16 (16.59%), HPV-58 (13.23%), HPV-18 (6.80%), HPV-56 (5.56%) and HPV-59 (5.56%). Cervical cytology revealed abnormal cells in 430 (39.49%) patients. The most common diagnoses were atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US; 236 cases, 54.88%), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL; 151 cases, 35.12%), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL; 63 cases, 14.65%) and atypical glandular cells (AGC; 21 cases, 4.88%). HPV-66 was significantly associated (P = 0.037) with ASC; HPV-52 and HPV-56 were significantly associated with LSIL (P = 0.009 and 0.026, respectively); HPV-16 (P < 0.001), HPV-33 (P = 0.014) and HPV-58 (P = 0.003) were significantly associated with HSIL; and HPV-16 (P = 0.005) was significantly associated with AGC. HPV-16, HPV-52 and HPV-58 are associated with different diagnoses in patients with positive cervical cytological findings.

Key words: Cervical cytology, genotype, human papillomavirus, local, neoplasm recurrence, survival rate, uterine cervical neoplasms

Introduction

Cervical cancer is one of the most common malignancies in women [1], and its incidence in China in 2015 was 9.89% in 2015 [2]. Radical hysterectomy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and concurrent chemo-radiotherapy are some of the treatment options available for cervical cancer [3]. Despite the variety of treatment options, the tumour recurrence rate varies from 10% to 50%, and the 5-year survival rate is approximately 65% depending on the disease stage [4]. Cervical cancer screening to detect early-stage lesions has led to dramatic reductions in the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer [5].

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is established as an essential pathogenic factor in the development of cervical cancer [6, 7]. Screening tests for HPV infection generally include 13 high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) genotypes (HPV-16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 and 68) [8–12]. Among these genotypes, HPV-16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58 are thought to be responsible for more than 90% of cases of cervical cancer [13–16]. The latest US cervical cancer screening guideline recommends a screening scheme based on age, with no screening recommended for women aged <21 or >65 years, cytology alone every 3 years for women aged 21–29 years, and the combination of cytology with HR-HPV testing for women aged 30–65 years [17]. However, the implementation of cervical cancer screening and recommended guidelines vary between different geographical regions due to differences in factors such as population and economic conditions [18–20]. Furthermore, geographic variations are observed in the HPV genotype distribution [21].

Data regarding HPV genotype distribution in women with HPV infection in the Sichuan area of China are limited. Therefore, the present retrospective analysis attempted to evaluate the HPV genotype distribution and association between the HPV genotype and cervical cytology findings in women in the Sichuan Province, China to provide new insights into the distribution of HPV genotypes in this region and clarify the relationship between HPV genotype and cervical cytology.

Methods

Study design and study participants

The present retrospective analysis was conducted in 1089 female outpatients with a positive HPV genotyping test result who underwent a cervical cytology test at the gynaecological clinic of the West China Second Hospital of Sichuan University (Chengdu, Sichuan, China) between January 2014 and December 2016. The inclusion criteria were: (1) female aged 15–74 years; (2) HPV genotyping and cervical cytology tests were performed at the same time; and (3) a positive result was obtained for the HPV genotyping test. The exclusion criteria were: (1) previous surgical treatment of cervical cancer; (2) immune system diseases; (3) chronic wasting diseases; and (4) previous organ transplantation.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Second Hospital of Sichuan University. All patients provided informed consent for cervical cytology and HPV testing. Consent for inclusion in the study was waived by our institution's ethics committee because the analysis was retrospective and anonymised.

Cervical cytology

All procedures were performed in accordance with the Cytology Room Work Regulations of our hospital in clinical laboratories with ISO15189 and the College of American Pathologists accreditation. Patients were asked not to rinse the vagina, administer vaginal drugs or have sexual intercourse for 3 days before the test. Samples of the exfoliated cervical cells were collected by trained and experienced specialists. The cervix was exposed with a disposable colposcope, the cervix mouth and surrounding secretion was wiped off, the cervical sample plate was used to rotate 360 degrees at the cervical orifice, and the exfoliated cells were immediately smeared on to a clean slide. The slide was then placed in a specimen bottle containing 95% ethanol. Papanicolaou smear cytology was performed using Papaniculaou stain, Gill's haematoxylin and EA-50 counterstain prepared in the cytology laboratory of our hospital using standardised procedures. The 2001 Bethesda System [22] was used to report the cervical cytological diagnosis using the following terminology: (1) atypical squamous cells (ASC), including ASC of undetermined significance (ASC-US) and ASC-cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (ASC-H); (2) low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL); (3) high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL); (4) squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); (5) atypical glandular cells (AGC); (6) adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS); (7) endocervical adenocarcinoma (Endo-CA); (8) endometrial adenocarcinoma (Endo-MA); (9) extrauterine adenocarcinoma (Extr-AA); (10) unclassified cancer cells (UCC); or (11) negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy.

HPV detection

Multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with universal primers was used together with flow cytometric detection of in situ hybridisation to simultaneously detect 26 HPV types. Sample collection was performed using a dedicated cervical exfoliated cell collector (Shanghai Toujing Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China). The cervix was exposed with a disposable colposcope, and the sampling brush was inserted into the cervical mouth, rotated thrice in the same direction and stay for 10 s. Then, the cervical brush containing the secretion was removed from the cervix and then inserted into a cell preservation solution. The collected samples were then subjected to nucleic acid extraction, amplification and hybridisation using multiple HPV gene typing kits. The PCR hybridisation products were analysed using a bead-based multiplexed immunoassay system in a microplate format (Luminex xMAP technology with a Luminex Liquid Chip 200 flow cytometer; Luminex Corp., Austin, TX, USA). A total of 26 HPV subtypes were identified as being closely related to cervical cancer development, including 13 high-risk types (HPV-16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 and 68), six intermediate-risk types (HPV-26, 53, 55, 66, 82 and 83) and seven low-risk types (HPV-6, 11, 40, 42, 44, 61 and 73) recognised by the World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer. The HPV subtype corresponding to the probe was considered to be positive if the signal corresponding to the type-specific probe was >150.

Data collection

Medical records were used to extract relevant patient clinical information such as age, cervical cytology findings and HPV genotype.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive statistical method was adopted for categorical data. The correlations between the various cervical cytological diagnoses and HPV genotypes were analysed using the χ2 test (sample size >40 and minimal theoretical frequency >5), χ2 test with correction for continuity (sample size >40 and minimal theoretical frequency ⩾1 and <5) or Fisher's exact test (if the conditions for the χ2 test were not satisfied). A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analysed using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

HPV genotype distribution

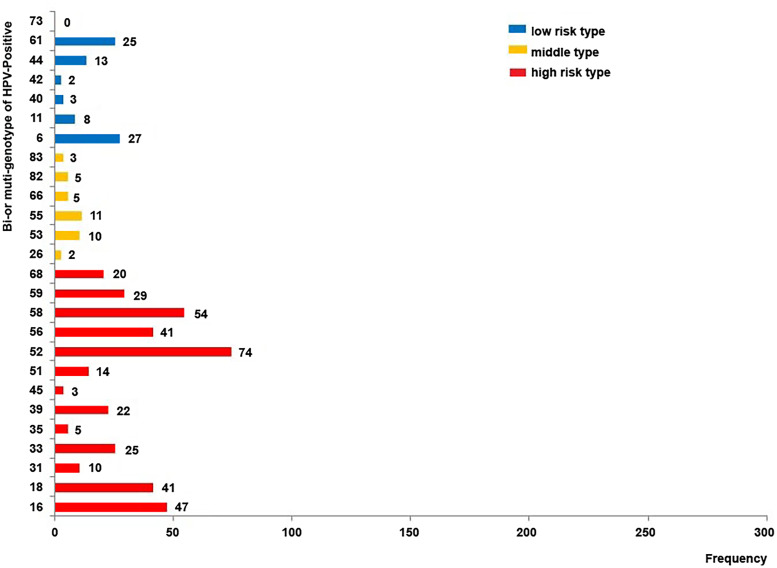

HPV genotyping was performed in 4517 outpatients, of which 1089 (24.1%) were positive for HPV infection. A total of 1368 HPV genotypes were detected (Fig. 1), of which 1145 (83.70%) were high-risk type. The genotypes detected most frequently were HPV-52 (18.64%), HPV-16 (16.59%), HPV-58 (13.23%), HPV-18 (6.80%), HPV-56 (5.56%) and HPV-59 (5.56%), all of which are considered high-risk subtypes (Fig. 1). HPV-53 (1.75%) and HPV-61 (3.44%) were the most common intermediate-risk and low-risk genotypes, respectively (Fig. 1). Table 1 presented the frequency of each HPV genotype according to age. The difference in the HPV genotype distribution between age groups was statistically non-significant.

Fig. 1.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) genotype distribution in 1089 women who tested positive for infection. The numerical value next to each bar illustrates the number of cases in which the genotype was detected. High-risk types: HPV-16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 and 68; intermediate-risk types: HPV-26, 53, 55, 66, 82 and 83; low-risk types: HPV-6, 11, 40, 42, 44, 61 and 73.

Table 1.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) genotype frequency stratified by age

| Age (years) | No. of patients | HPV genotype | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV-16 | HPV-18 | HPV-31 | HPV-33 | HPV-35 | HPV-39 | HPV-45 | HPV-51 | HPV-52 | HPV-56 | HPV-58 | HPV-59 | HPV-68 | Total | ||

| 15–24 | 95 | 17 (17.89%) | 6 (6.32%) | 0 (0.00%) | 8 (8.42%) | 1 (1.05%) | 6 (6.32%) | 0 (0.00%) | 3 (3.16%) | 27 (28.42%) | 9 (9.47%) | 12 (12.63%) | 8 (8.42%) | 3 (3.16%) | 102 |

| 25–34 | 347 | 65 (18.73%) | 26 (7.49%) | 9 (2.59%) | 12 (3.46%) | 4 (1.15%) | 20 (5.76%) | 7 (2.01%) | 17 (4.90%) | 86 (24.78%) | 24 (6.92%) | 46 (13.26%) | 23 (6.63%) | 13 (3.75%) | 352 |

| 35–44 | 421 | 86 (20.43%) | 38 (9.03%) | 7 (1.66%) | 27 (6.41%) | 6 (1.43%) | 18 (4.28%) | 2 (0.48%) | 10 (2.38%) | 91 (21.62%) | 24 (5.70%) | 74 (17.58%) | 36 (8.55%) | 19 (4.51%) | 438 |

| 45–59 | 206 | 51 (24.76%) | 19 (9.22%) | 6 (2.91%) | 8 (3.88%) | 0 (0.00%) | 11 (5.34%) | 0 (0.00%) | 3 (1.46%) | 48 (23.30%) | 16 (7.77%) | 40 (19.42%) | 9 (4.37%) | 11 (5.34%) | 222 |

| 60–74 | 20 | 6 (30.00%) | 2 (10.00%) | 2 (10.00%) | 2 (10.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (5.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 3 (15.00%) | 3 (15.00%) | 6 (30.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (5.00%) | 26 |

Data are presented as the number of patients in that age group positive for the HPV genotype (% of patients in that age group positive for the HPV genotype). Note that the percentage values for each row total >100% since some of the patients were positive for more than one genotype.

Of the 1089 patients who tested positive for HPV infection, 869 (79.80%) were infected by a single HPV type (Fig. 2). High-risk genotypes accounted for 87.46% of the HPV infections in these 869 women, with the most common genotypes being HPV-52 (20.83%), HPV-16 (20.71%), HPV-58 (14.61%), HPV-18 (5.98%), HPV-59 (5.41%) and HPV-56 (4.03%) (Fig. 2). Of the 220 patients who tested positive for multiple (2–5) genotypes (Fig. 3), 172 (78.2%) were infected with two types, 39 (17.7%) were infected with three types, and nine (4.1%) were infected with four or five types of HPV. Therefore, the average infection rate was 2.27 genotypes/patient. High-risk genotypes accounted for 77.15% of the HPV types in patients with multiple infections, and the most common genotypes were HPV-52 (14.83%), HPV-58 (10.82%), HPV-16 (9.42%), HPV-18 (8.22%), HPV-56 (8.22%) and HPV-59 (5.81%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) genotype distribution in 869 women who tested positive for a single HPV genotype. The numerical value next to each bar illustrates the number of cases in which the genotype was detected. High-risk types: HPV-16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 and 68; intermediate-risk types: HPV-26, 53, 55, 66, 82 and 83; low-risk types: HPV-6, 11, 40, 42, 44, 61 and 73.

Fig. 3.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) genotype distribution in 220 women who tested positive for multiple HPV genotypes. The numerical value next to each bar illustrates the number of cases in which the genotype was detected. High-risk types: HPV-16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 and 68; intermediate-risk types: HPV-26, 53, 55, 66, 82 and 83; low-risk types: HPV-6, 11, 40, 42, 44, 61 and 73.

Cervical cytology findings

Of the 1089 patients with HPV infection, cervical cytology revealed abnormal cells in 430 (39.49%) patients. Of the 430 patients, 384 (89.30%) were diagnosed with one type of abnormality, 45 (10.47%) were diagnosed with two types of abnormality, and one (0.23%) was diagnosed with three types of abnormality. The abnormalities detected in the 430 patients with positive cytology findings were ASC-US (236 cases, 54.88%), LSIL (151 cases, 35.12%), HSIL (63 cases, 14.65%), AGC (21 cases, 4.88%), ASC-H (10 cases, 2.33%) and UCC (four cases, 0.93%). Therefore, HSIL was observed in 5.79% of all patients with HPV infection. SCC, AIS, Endo-CA, Endo-MA and Extr-AA were not observed in any patients. Table 2 presented the cervical cytology diagnoses stratified by age.

Table 2.

Cervical cytological diagnoses stratified by age

| Age (years) | Number of patients | Abnormal cervical cytology findings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASC-US | ASC-H | LSIL | HSIL | AGC | UCC | Total | ||

| 15–24 | 28 | 14 (50.00%) | 0 | 14 (50.00%) | 1 (3.57%) | 0 | 0 | 29 |

| 25–34 | 129 | 75 (54.74%) | 1 (0.73%) | 45 (32.85%) | 12 (8.76%) | 4 (2.92%) | 0 | 137 |

| 35–44 | 177 | 90 (42.86%) | 6 (2.86%) | 65 (30.95%) | 34 (16.19%) | 13 (6.19%) | 2 (0.95%) | 210 |

| 45–59 | 85 | 52 (54.17%) | 3 (3.13%) | 24 (25.00%) | 12 (12.50%) | 3 (3.13%) | 2 (2.08%) | 96 |

| 60–74 | 11 | 5 (38.46%) | 0 (0.00%) | 3 (23.08%) | 4 (30.77%) | 1 (7.69%) | 0 (0.00%) | 13 |

Data are presented as the number of patients in that age group positive for the cervical cytology diagnosis (% of patients in that age group positive for the cervical cytology diagnosis). Note that the percentage values for each row total to >100% as some of the patients exhibit more than one type of cervical cytological abnormality. AGC, atypical glandular cells; ASC-H, atypical squamous cells – cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; ASC-US, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; UCC, unclassified cancer cells.

Associations between cervical cytology diagnoses and HPV subtypes

The associations between cervical cytology diagnoses and HPV genotypes are presented in Table 3. HPV-66 (continuity-corrected χ2 = 4.35, P = 0.037) was significantly associated with ASC. HPV-52 (χ2 = 6.85, P = 0.009) and HPV-56 (χ2 = 4.95, P = 0.026) were significantly associated with LSIL. HPV-16 (χ2 = 36.35, P < 0.001), HPV-33 (continuity-corrected χ2 = 6.00, P = 0.014) and HPV-58 (χ2 = 8.84, P = 0.003) were significantly associated with HSIL, and when each of these genotypes was detected, the rate of HSIL diagnosis was 14.09%, 14.04% and 10.50%, respectively. HPV-16 (continuity-corrected χ2 = 7.72, P = 0.005) was also significantly associated with AGC (Table 4).

Table 3.

HPV type prevalence with abnormal cervical cytology

| HPV types | Total (n = 430) | ASCUS (n = 236) | ASC (n = 10) | LSIL (n = 151) | HSIL (n = 63) | UCC (n = 4) | AGC (n = 21) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV52 | 80 (18.64%) | 64 (27.5%) | 1 (8.3%) | 40 (30.5%) | 9 (16.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (9.1%) |

| HPV16 | 71 (23.1%) | 41 (17.6%) | 7 (58.3%) | 23 (17.6%) | 28 (50.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 11 (50.0%) |

| HPV58 | 78 (18.0%) | 39 (16.7%) | 2 (16.7%) | 19 (14.5%) | 18 (32.1%) | 1 (20.0%) | 6 (27.3%) |

| HPV56 | 34 (7.9%) | 16 (6.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 17 (13.0%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV18 | 31 (7.2%) | 21 (9.0%) | 1 (8.3%) | 7 (5.3%) | 2 (3.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (18.2%) |

| HPV33 | 27 (6.2%) | 7 (3.0%) | 2 (16.7%) | 10 (7.6%) | 8 (14.3%) | 1 (20.0%) | 2 (9.1%) |

| HPV39 | 27 (6.2%) | 15 (6.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (8.4%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV59 | 24 (5.5%) | 17 (7.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (5.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV51 | 17 (3.9%) | 8 (3.4%) | 1 (8.3%) | 8 (6.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV68 | 15 (3.5%) | 7 (3.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (6.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV53 | 14 (3.2%) | 8 (3.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (4.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV66 | 13 (3.0%) | 9 (3.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (3.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV55 | 11 (2.5%) | 6 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (3.1%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV31 | 8 (1.8%) | 6 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV35 | 8 (1.8%) | 4 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (3.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV82 | 3 (0.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV45 | 2 (0.5%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV83 | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV26 | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV6 | 16 (3.7%) | 10 (4.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 5 (3.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.5%) |

| HPV61 | 9 (2.1%) | 6 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (2.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV11 | 8 (1.8%) | 7 (3.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV44 | 7 (1.6%) | 4 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (2.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV40 | 3 (0.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV42 | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 00 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| HPV73 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 00 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

HPV genotype attributable fraction in the total of 340 HPV and cytology both positive patients.

HPV, human papillomavirus; ASC-US, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; ASC-H, atypical squamous cells, cannot rule out HSIL; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; AGC, atypical glandular cell. HR-HPVs include HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51,52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 6 putative high-risk types (26, 53, 55, 68, 82 and 83), LR-HPVs include HPV 6, 11, 40, 42, 44, 61 and 73.

Seven cases of AGC complicated with ASCUS, three cases of AGC complicated with ASC, and 11 cases of AGC complicated with HSIL.

Table 4.

Associations between cervical cytology diagnoses and human papillomavirus (HPV) genotypes

| ASC | LSIL | HSIL | AGC | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With | Without | P | With | Without | P | With | Without | P | With | Without | P | ||

| HPV-66 | Positive | 9 | 12 | 0.037 | 4 | 17 | 0.708 | 0 | 21 | 0.500 | 0 | 21 | 1.000 |

| Negative | 229 | 839 | 147 | 921 | 63 | 1005 | 21 | 1047 | |||||

| HPV-52 | Positive | 65 | 190 | 0.108 | 48 | 207 | 0.009 | 10 | 245 | 0.145 | 2 | 253 | 0.208 |

| Negative | 173 | 661 | 103 | 731 | 53 | 781 | 19 | 815 | |||||

| HPV-56 | Positive | 16 | 60 | 0.861 | 17 | 59 | 0.026 | 1 | 75 | 0.140 | 0 | 76 | 0.404 |

| Negative | 222 | 791 | 134 | 879 | 62 | 951 | 21 | 992 | |||||

| HPV-16 | Positive | 44 | 183 | 0.311 | 28 | 199 | 0.453 | 32 | 195 | <0.001 | 10 | 217 | 0.005 |

| Negative | 194 | 668 | 123 | 739 | 31 | 831 | 11 | 851 | |||||

| HPV-33 | Positive | 9 | 48 | 0.255 | 12 | 45 | 0.107 | 8 | 49 | 0.014 | 2 | 55 | 0.692 |

| Negative | 229 | 803 | 139 | 893 | 55 | 977 | 19 | 1013 | |||||

| HPV-58 | Positive | 39 | 142 | 0.913 | 25 | 156 | 0.982 | 19 | 162 | 0.003 | 6 | 175 | 0.234 |

| Negative | 199 | 709 | 126 | 782 | 44 | 864 | 15 | 893 | |||||

AGC, atypical glandular cells; ASC, atypical squamous cells; HPV, human papillomavirus; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion.

Discussion

Cervical cancer is the third most common cancer in women worldwide [23]. Studies have reported a 9.6/100 000 morbidity rate and a 4.3/100 000 mortality rate of cervical cancer in China. The mortality has increased in lower socioeconomic areas [24, 25].

HR-HPV infection is recognised as a significant factor for cervical cancer pathogenesis. Over 150 HPV subtypes have been identified currently, with 40 possessing the ability to cause a reproductive tract infection [26, 27]. The present study identified HPV-52, HPV-16, HPV-58, HPV-18, HPV-56 and HPV-59 as the six most common HPV subtypes in 1089 women with HPV infection in the Sichuan Province. Studies have identified HPV-52, HPV-16, HPV-58 and HPV-18 among the seven HPV genotypes responsible for the vast majority of cervical cancer cases worldwide [13–16]. This finding is mirrored in the present study, too. However, the present study identified HPV-56 and HPV-59 as the fifth and sixth most common subtypes. This finding differed from other studies, suggesting that the distribution of HPV genotypes in patients differed from those reported for other regions of China or other countries. This finding is concurrent with other studies demonstrating geographic variation in the distribution of HPV genotypes associated with cervical cancer [21].

The present study demonstrated a high rate of infection with HPV-58, which is consistent with other reports from other areas in China [28–31]. However, regional disparities in HPV subtype distribution exist [28–31]. The infection rates with HPV-31 and HPV-33 in the present study were lower for our cohort than for those in European and American countries [32]. The present study identified HPV-45 as the least common of all the HR-HPV subtypes. This finding is in contrast with the study by de Sanjosé et al., who reported HPV-45 as the third most common subtype detected in association with cervical cancer, accounting for 12% of HPV subtypes in women with cervical adenocarcinoma [16].

Studies conducted outside of China have suggested that HPV-18 is the second most carcinogenic genotype among the HPV subtypes and that infection with HPV-18 is observed in approximately 10–15% of cervical cancer cases [16, 33, 34]. Furthermore, HPV-18 tends to be associated more with SCC than with adenocarcinoma of the cervix. This finding is in contrast with the findings of the present study, which indicated that HPV-18 was not associated with any particular type of cervical cytological abnormality. Li et al. observed that the HPV-16 and HPV-58 infection rates among females in western China were higher than those in other areas of the world [35, 36]. Moreover, a meta-analysis based on the global HPV subtype distribution observed East Asian countries such as China, Korea and Japan exhibited higher HPV-52 and HPV-58 infection rates in association with HSIL and ICC than African countries [30, 37, 38]. The HPV-52 and HPV-58 subtypes are highly distributed in many regions, identifying them as significant causes of local cervical lesions. Simultaneously, we also observed that 220 HPV-positive patients were positive for multiple genotypes, of which 211 (95.9%) were co-infected with types 2–3, and the average infection rate was 2.27 genotypes per patient. High-risk genotypes accounted for 77.15% of HPV types in patients with multiple infections, and HPV-52 and HPV-58 were the most commonly associated. Therefore, future research on HPV infection in local populations must consider these two subtypes.

The present study also observed that HPV-16 was associated with HSIL and AGC, which are considered high-grade lesions. Notably, AGC was only associated with HPV-16 infection, revealing that HPV-16 may be a particularly carcinogenic subtype among the various HPV genotypes. Since HPV infection could potentially be detected before the development of any cervical cytological abnormalities, testing for HPV infection must be performed and the genotype involved must be identified to prevent the development of cervical cancer. In particular, testing and immunisation strategies that target HR-HPV genotypes such as HPV-16 could effectively prevent the development of cervical cancer or allow early curative treatment.

The present study has some limitations. The single-centre design of the study prevents the generalisation of the findings to the entire region of Sichuan or Southwest China. Nevertheless, given that the study site is the largest maternity and children's hospital in the southwestern region of China, the patient population was from various regions of Sichuan Province, and the sample size was relatively large. Additionally, the retrospective design of the study exposes the results to information or selection bias.

In conclusion, the present study illustrates that HPV infection in the Sichuan region of China has specific characteristics that differ from those in other geographic regions. Furthermore, HPV-16, HPV-58 and HPV-52 were the major subtypes associated with cervical lesions identified by cytological tests. The findings of this study extend our knowledge of the epidemiology of HPV infection in Sichuan Province and hence provide a basis for the formulation of health policies aimed at controlling HPV infection locally. Additionally, the present study can serve as a reference in the planning and implementation of future large-scale, multicentre, prospective studies on the distribution of HPV genotypes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the study participants.

Financial support

Key R & D Projects of Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province in 2020, 2020YFS0106.

Data

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Torre LA et al. (2015) Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 65, 87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W et al. (2016) Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 66, 115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Somashekhar SP and Ashwin KR (2015) Management of early stage cervical cancer. Reviews on Recent Clinical Trials 10, 302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carneiro SR et al. (2017) Five-year survival and associated factors in women treated for cervical cancer at a reference hospital in the Brazilian Amazon. PLoS ONE 12, e0187579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landy R et al. (2016) Impact of cervical screening on cervical cancer mortality: estimation using stage-specific results from a nested case-control study. British Journal of Cancer 115, 1140–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouvard V et al. (2009) A review of human carcinogens – part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncology 10, 321–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Sanjosé S, Brotons M and Pavón MA (2018) The natural history of human papillomavirus infection. Best Practice & Research: Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 47, 2–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poljak M and Kocjan BJ (2010) Commercially available assays for multiplex detection of alpha human papillomaviruses. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy 8, 1139–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arbyn M et al. (2016) VALGENT: a protocol for clinical validation of human papillomavirus assays. Journal of Clinical Virology 76(Suppl 1), S14–s21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan PK et al. (2012) Laboratory and clinical aspects of human papillomavirus testing. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences 49, 117–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuzick J and Wheeler C (2016) Need for expanded HPV genotyping for cervical screening. Papillomavirus Research 2, 112–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaliamurthi S et al. (2019) Exploring the papillomaviral proteome to identify potential candidates for a chimeric vaccine against cervix papilloma using immunomics and computational structural vaccinology. Viruses 11, 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosch FX (2008) HPV vaccines and cervical cancer. Annals of Oncology 19(Suppl 5), v48–v51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joura EA et al. (2014) Attribution of 12 high-risk human papillomavirus genotypes to infection and cervical disease. Cancer Epidemiology. Biomarkers & Prevention 23, 1997–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serrano B et al. (2015) Human papillomavirus genotype attribution for HPVs 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58 in female anogenital lesions. European Journal of Cancer 51, 1732–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Sanjosé S et al. (2010) Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in invasive cervical cancer: a retrospective cross-sectional worldwide study. Lancet Oncology 11, 1048–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saslow D et al. (2012) American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 62, 147–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chrysostomou AC et al. (2018) Cervical cancer screening programs in Europe: the transition towards HPV vaccination and population-based HPV testing. Viruses 10, 729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Catarino R et al. (2015) Cervical cancer screening in developing countries at a crossroad: emerging technologies and policy choices. World Journal of Clinical Oncology 6, 281–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaliamurthi S et al. (2018) Cancer immunoinformatics: a promising era in the development of peptide vaccines for human papillomavirus-induced cervical cancer. Current Pharmaceutical Design 24, 3791–3817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Husain RS and Ramakrishnan V (2015) Global variation of human papillomavirus genotypes and selected genes involved in cervical malignancies. Annals of Global Health 81, 675–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nayar R and Wilbur DC (2017) The Bethesda system for reporting cervical cytology: a historical perspective. Acta Cytologica 61, 359–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arbyn M et al. (2011) Worldwide burden of cervical cancer in 2008. Annals of Oncology 22, 2675–2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferlay J et al. (2010) Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. International Journal of Cancer 127, 2893–2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang L et al. (2003) Time trends in cancer mortality in China: 1987–1999. International Journal of Cancer 106, 771–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Villiers EM et al. (2004) Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology 324, 17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernard HU et al. (2010) Classification of papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virology 401, 70–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai HB, Ding XH and Chen CC (2009) Prevalence of single and multiple human papillomavirus types in cervical cancer and precursor lesions in Hubei, China. Oncology 76, 157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan PK et al. (2012) Attribution of human papillomavirus types to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive cancers in Southern China. International Journal of Cancer 131, 692–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan PK et al. (2009) Distribution of human papillomavirus types in cervical cancers in Hong Kong: current situation and changes over the last decades. International Journal of Cancer 125, 1671–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chao A et al. (2011) Human papillomavirus genotype in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 2 and 3 of Taiwanese women. International Journal of Cancer 128, 653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crow JM (2012) HPV: the global burden. Nature 488, S2–S3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walboomers JM et al. (1999) Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. Journal of Pathology 189, 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muñoz N et al. (2003) Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 348, 518–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J et al. (2011) Prevalence and genotype distribution of human papillomavirus in women with cervical cancer or high-grade precancerous lesions in Chengdu, western China. International Journal of Gynaecology Obstetrics 112, 131–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J et al. (2012) Human papillomavirus type-specific prevalence in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasm in Western China. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 50, 1079–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ding DC et al. (2008) Type-specific distribution of HPV along the full spectrum of cervical carcinogenesis in Taiwan: an indication of viral oncogenic potential. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 140, 245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asato T et al. (2004) A large case-control study of cervical cancer risk associated with human papillomavirus infection in Japan, by nucleotide sequencing-based genotyping. Journal of Infectious Diseases 189, 1829–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.