Key Points

Question

What is the association between age at onset of type 2 diabetes and subsequent risk of dementia?

Findings

In this prospective cohort study of 10 095 participants, younger age at onset of type 2 diabetes was significantly associated with higher risk for incident dementia; at age 70, the hazard ratio for every 5-year earlier age at type 2 diabetes onset was 1.24.

Meaning

Younger age at diabetes onset was associated with higher risk of subsequent dementia.

Abstract

Importance

Trends in type 2 diabetes show an increase in prevalence along with younger age of onset. While vascular complications of early-onset type 2 diabetes are known, the associations with dementia remains unclear.

Objective

To determine whether younger age at diabetes onset is more strongly associated with incidence of dementia.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Population-based study in the UK, the Whitehall II prospective cohort study, established in 1985-1988, with clinical examinations in 1991-1993, 1997-1999, 2002-2004, 2007-2009, 2012-2013, and 2015-2016, and linkage to electronic health records until March 2019. The date of final follow-up was March 31, 2019.

Exposures

Type 2 diabetes, defined as a fasting blood glucose level greater than or equal to 126 mg/dL at clinical examination, physician-diagnosed type 2 diabetes, use of diabetes medication, or hospital record of diabetes between 1985 and 2019.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Incident dementia ascertained through linkage to electronic health records.

Results

Among 10 095 participants (67.3% men; aged 35-55 years in 1985-1988), a total of 1710 cases of diabetes and 639 cases of dementia were recorded over a median follow-up of 31.7 years. Dementia rates per 1000 person-years were 8.9 in participants without diabetes at age 70 years, and rates were 10.0 per 1000 person-years for participants with diabetes onset up to 5 years earlier, 13.0 for 6 to 10 years earlier, and 18.3 for more than 10 years earlier. In multivariable-adjusted analyses, compared with participants without diabetes at age 70, the hazard ratio (HR) of dementia in participants with diabetes onset more than 10 years earlier was 2.12 (95% CI, 1.50-3.00), 1.49 (95% CI, 0.95-2.32) for diabetes onset 6 to 10 years earlier, and 1.11 (95% CI, 0.70-1.76) for diabetes onset 5 years earlier or less; linear trend test (P < .001) indicated a graded association between age at onset of type 2 diabetes and dementia. At age 70, every 5-year younger age at onset of type 2 diabetes was significantly associated with an HR of dementia of 1.24 (95% CI, 1.06-1.46) in analyses adjusted for sociodemographic factors, health behaviors, and health-related measures.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this longitudinal cohort study with a median follow-up of 31.7 years, younger age at onset of diabetes was significantly associated with higher risk of subsequent dementia.

This cohort study uses UK Whitehall cohort data to examine the association between age at type 2 diabetes onset and incident dementia.

Introduction

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes has risen due to population aging, increasing obesity, physical inactivity, and energy-dense diets.1 More than 90% of individuals with diabetes have type 2 diabetes, and among these individuals, there is considerable potential for disease management to reduce risk of subsequent health complications. Diabetes is associated with higher risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,2 along with mortality from nonvascular conditions.3

While the role of type 2 diabetes for cardiovascular outcomes is established, its importance for neurocognitive outcomes remains uncertain. Large-scale, multicohort meta-analyses published in 2012,4 2016,5 2017,6 and 20197,8 have shown the risk ratio of the association between diabetes and dementia to be between 1.43 and 1.62.4,5,6,7,8 The primary limitation of these studies was not being able to examine the importance of age at diabetes onset for dementia, particularly as younger age at type 2 diabetes onset is known to be important for mortality and cardiovascular outcomes.9,10,11 The most recent review of 12 modifiable risk factors for dementia carefully separated risk factors in early- (<45 years), mid- (45-65 years), and late-life (>65 years) age groups; diabetes was judged to be a risk factor only in late life, associated with a population-attributable fraction of 1.1%.12

Given evidence of younger age at onset of diabetes,13 the primary objective of this study was to examine the association between age at onset of diabetes and incident dementia using data spanning midlife to old age.

Methods

Study Population

The Whitehall II study is an ongoing cohort study established in 1985-1988 among 10 308 persons (6895 men and 3413 women, aged 35-55 years) employed in London-based government departments.14 Written informed consent from participants and research ethics approvals were renewed at each contact; the most recent approval was from the University College London Hospital Committee on the Ethics of Human Research (reference number 85/0938). The age, sex, and race distribution in the study reflects that in the target population; for race, it also reflects the UK population distribution in the 1980s. Since baseline, follow-up clinical examinations have taken place approximately every 4 to 5 years (1991-1993, 1997-1999, 2002-2004, 2007-2009, 2012-2013, and 2015-2016) with each wave taking 2 years to complete, with ongoing data collection at the 2020-2021 wave. In addition to data collection within the study, data over the follow-up were available using linkage to electronic health records of the UK National Health Service (NHS) for all but 10 of the 10 308 participants recruited to the study (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). The NHS provides most of the health care in the UK, including inpatient and outpatient care, and record linkage is undertaken using a unique NHS identifier held by all UK residents. Data from linked records were updated on an annual basis until March 31, 2019.

Primary Exposure

Type 2 Diabetes

At 7 clinical assessments between 1985 and 2016, venous blood samples were taken in the morning after at least 8 hours of fasting or at least 5 hours fasting after a light, fat-free breakfast; fasting glucose was measured using the glucose-oxidase method.15 At the clinical examination, data were also collected on self-reported physician-diagnosed type 2 diabetes and prescription of diabetes medication (insulin or oral glucose-lowering drugs) in the period between 2 clinical assessments. In addition, data on hospital-based consultations for type 2 diabetes were available via linkage to the national Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database over the entire follow-up on all participants, irrespective of their participation in study clinical assessments. Type 2 diabetes was defined using measures of fasting glucose (126 mg/dL [to convert to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0555]) at the clinical examination, use of diabetes medication, reported physician-diagnosed diabetes, or record of diabetes in the HES database (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] code E11).

Secondary Exposures

Three exposures were assessed in participants free of type 2 diabetes: the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC), fasting glucose, and prediabetes.

The FINDRISC16 was used to calculate the risk of diabetes based on the original scoring method (eTable 1 in the Supplement), which included age, family history of diabetes, fruit and vegetable consumption, physical activity, medication for high blood pressure, personal history of high blood glucose (clinical examination), body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), and measured waist circumference. The FINDRISC ranges from 0 to 26 (higher scores reflect higher risk of diabetes when the score is used as a continuous variable, as in these analyses).

In addition to continuous measures of fasting glucose, prediabetes was defined according to the American Diabetes Association criteria (fasting glucose between 100-125 mg/dL) and in additional analysis using World Health Organization criteria (110-125 mg/dL).

Outcome

Dementia cases were ascertained by linkage to 3 national registers (the HES database, the Mental Health Services Data Set, and the Office for National Statistics Mortality Register) until March 31, 2019, using the unique NHS identification number. All-cause dementia was identified based on ICD-10 codes (F00-F03, F05.1, G30, and G31). The sensitivity of dementia was 78% and the specificity was 92% using HES data.17 The sensitivity in our study is likely to be further improved due to use of the Mental Health Services Data Set, a national database that contains information on dementia for persons in contact with mental health services in hospitals, outpatient clinics, and the community.18 Cause-specific mortality data were drawn from the NHS national mortality register. Date of dementia was set at the first record of dementia diagnosis using all 3 databases.

Covariates

Sociodemographic

Variables included age, sex, race (assessed by questionnaire using the response categories White, South Asian, Black, Other), and education (≤partial secondary school, high school diploma, ≥university).

Health Behaviors

Variables included smoking (never smoker, current smoker, former smoker), alcohol consumption (none in the previous week, 1-14 units/week, >14 units/week; 1 unit reflects 10 mL [8 g] of pure alcohol), time spent in moderate and vigorous physical activity, and frequency of fruit and vegetable consumption (less than daily, once daily, ≥2 times/day).

Health-Related Variables

These variables included hypertension (systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg or use of antihypertensive medication), BMI (<25, 25-29.9, and ≥30), use of antidepressants and cardiovascular disease (CVD) medication (diuretics, β-blockers, RAAS inhibitors, calcium channel blockers or other antihypertensives, lipid-modifying drugs, nitrates, and antiplatelets).

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotyping DNA was extracted from whole blood samples and examined on a 7900HT analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Cardiovascular Disease

Variables included coronary heart disease (CHD), heart failure, and stroke. CHD was identified by 12-lead resting electrocardiogram recording coded using the Minnesota system and linkage to the HES database (ICD-10 codes I20-I25). Heart failure (ICD-10 code I50) and stroke (ICD-10 codes I60-I64) were determined using linkage to the HES database.

Statistical Analysis

Data on exposure (diabetes, prediabetes, fasting glucose, and FINDRISC) at ages 55, 60, 65, and 70 years were extracted using the total span of the study (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). The analyses were undertaken using Cox regression when the outcome was incidence of dementia; prevalent dementia at the start of follow-up was excluded in all the analyses. Participants were censored at the date of record of dementia, death, or March 31, 2019, whichever came first. Participants who died over the follow-up were censored at date of death to account for competing risk of death using cause-specific hazard models.19,20 Proportional hazards assumption was verified by plotting Schoenfeld residuals. Analyses were first adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and birth cohort in 5-year groups (model 1) to account for confounding due sociodemographic characteristics. The analyses were then additionally adjusted for health behaviors (model 2), and in the final model also for CVD, hypertension, BMI, use of antidepressants, and use of CVD medication (model 3).

Association of Type 2 Diabetes With Incident Dementia

This association was examined according to age at type 2 diabetes onset (at 55, 60, 65, and 70 years) with the reference group at each age being participants free of type 2 diabetes at that specific age. At age 55, this implied comparing those with type 2 diabetes at that point or earlier with those free of type 2 diabetes at 55 years and treating diabetes cases after age 55 as nondiabetes cases. Besides diabetes status at ages 55, 60, 65, and 70, we also examined diabetes as a time-varying measure. Subsequent analyses at ages 60, 65, and 70 years involved use of 5-year age bands for the onset of type 2 diabetes. For example, at age 70 years the group defined as having no type 2 diabetes at age 70 was compared with a group diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at 5 or fewer years earlier, 6-10 years earlier, and more than 10 years earlier. A test for trend using diabetes categories as a linear variable was used to examine whether the magnitude of associations of type 2 diabetes with dementia was higher with younger age at diabetes onset. In addition, using diabetes status at age 70, the association between every 5-year younger age at diabetes onset and incident dementia was estimated.

FINDRISC, Fasting Glucose, and Prediabetes in Participants Without Type 2 Diabetes

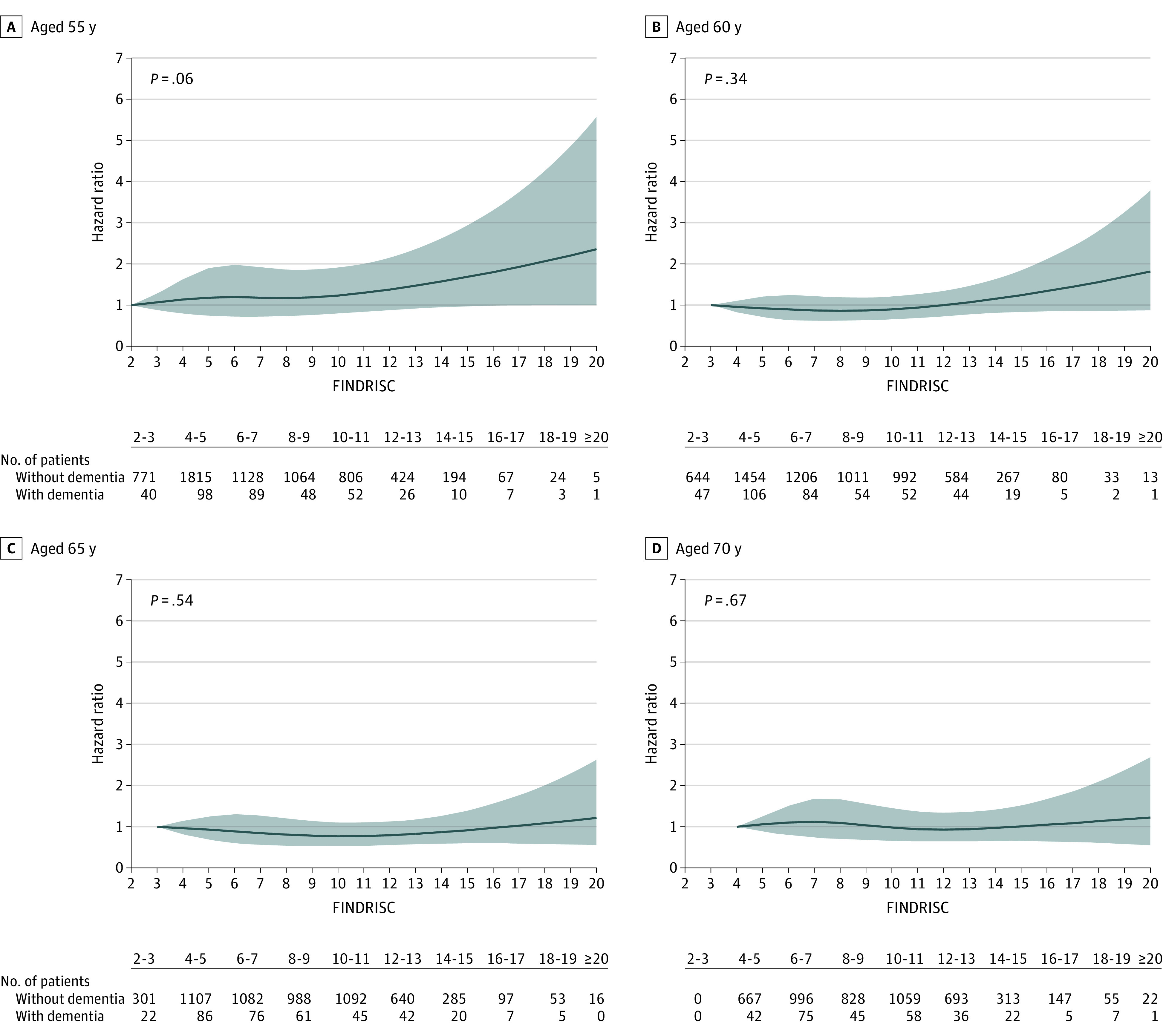

The shape of the association between continuous measures of FINDRISC, at ages 55, 60, 65, and 70 years and subsequent dementia was plotted using restricted cubic splines with Harrell knots,21 using the command mkspline in Stata. In the absence of nonlinearity (P = .61 at age 55, P = .16 at age 60, P = .26 at age 65, P = .56 at age 70), we examined the association of a 5-point higher FINDRISC score and subsequent dementia using Cox regression.

For analysis of prediabetes, 3 groups were defined: normoglycemic (<100 mg/dL), prediabetes (100-125 mg/dL), and type 2 diabetes. Cox regression was used to examine associations with dementia using the normoglycemic group as the reference standard. These analyses were repeated using the World Health Organization threshold to define prediabetes (110-125 mg/dL). The association of fasting glucose levels as a continuous measure between 90 and 126 mg/dL at a mean (SD) age of 60 (4) years and dementia was examined using restricted cubic splines21 with 4 knots. As there was no evidence of nonlinearity (P value for nonlinearity, .82), the hazard ratio (HR) for 18 mg/dL-higher fasting glucose was estimated.

Type 2 Diabetes, CVD Comorbidity, and Dementia

The risk of dementia among participants with type 2 diabetes without CVD was compared with participants who had type 2 diabetes and CVD comorbidity (CHD, heart failure, and stroke). Participants were followed up from the date at type 2 diabetes diagnosis with cardiovascular comorbidity (individually, 2 of 3, or all 3) as time-varying covariates.

Additional Analysis

First, in an alternative approach to take competing risk of mortality into account, the Fine and Gray subdistribution hazard models19,20 were used in analysis of the association between age at diabetes onset and dementia. Second, we examined whether the association of type 2 diabetes, treated as a time-varying measure, and incidence of dementia was similar in APOE ε4 allele carriers and non-carriers by introducing an interaction term between type 2 diabetes and APOE genotype (coded as no vs ≥1 APOE ε4 allele).

Because of the potential for type 1 error due to multiple comparisons, findings for secondary analyses should be interpreted as exploratory. Two-sided P values were used with an α = .05 threshold for statistical significance. All analyses were undertaken using STATA version 15.1 (StataCorp).

Results

A total of 10 308 persons were recruited to the study in 1985, the numbers in analyses and exclusions are shown in eFigure 1 in the Supplement. Characteristics of 10 095 participants in the analyses are presented in Table 1. The numbers of participants who were categorized as Black, South Asian, and other were small and were combined in the analyses. Between 1985 and 2019, 639 (6.3%) participants were diagnosed with dementia; these individuals were more likely to have chronic conditions over the follow-up period and to have a worse cardiovascular risk profile at age 60 (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of Participants According to Dementia Status at the End of the Follow-up, March 2019.

| Participant characteristics at the end of follow-upa | Dementia status, No. (%)b | |

|---|---|---|

| Dementia (n=639) | No dementia (n=9456) | |

| Men | 374 (58.5) | 6424 (67.9) |

| Women | 265 (41.5) | 3032 (32.1) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 76.8 (6.0) | 74.6 (7.2) |

| Education | ||

| ≤Partial secondary school | 378 (59.2) | 4398 (46.5) |

| High school diploma | 135 (21.1) | 2550 (27.0) |

| ≥University degree | 126 (19.7) | 2508 (26.5) |

| Racec | ||

| White | 547 (85.6) | 8546 (90.4) |

| South Asian | 47 (7.4) | 524 (5.5) |

| Black | 41 (6.4) | 315 (3.3) |

| Other | 4 (0.6) | 71 (0.8) |

| Health conditions | ||

| Coronary heart disease | 170 (26.6) | 1920 (20.3) |

| Diabetes | 153 (23.9) | 1557 (16.5) |

| Heart failure | 56 (8.8) | 520 (5.5) |

| Stroke | 57 (8.9) | 373 (3.9) |

| Risk factors in participants at age 60, No. (%)d | ||

| (n=633) | (n=9127) | |

| Hypertension | 256 (40.4) | 3069 (33.6) |

| Body mass indexe | ||

| <25 | 273 (43.1) | 3910 (42.8) |

| 25-29.9 | 251 (39.7) | 3782 (41.4) |

| ≥30 | 109 (17.2) | 1435 (15.7) |

| Smoking | ||

| Never | 303 (47.9) | 4301 (47.2) |

| Former | 234 (37.0) | 3688 (40.4) |

| Current | 96 (15.2) | 1138 (12.5) |

| Moderate and vigorous physical activity, mean (SD), h/wk | 3.4 (4.0) | 3.6 (3.7) |

| Alcohol consumption, units/wk | ||

| 0 | 192 (30.3) | 1772 (19.4) |

| 1-14 | 307 (48.5) | 4857 (53.2) |

| >14 | 134 (21.2) | 2498 (27.4) |

| Fruit and vegetable consumption/d | ||

| <1 | 229 (36.2) | 2778 (30.4) |

| 1 | 261 (41.2) | 3334 (36.5) |

| >1 | 143 (22.6) | 3015 (33.0) |

| Cardiovascular disease medication | 172 (27.2) | 2275 (24.9) |

| Use of antidepressants | 23 (3.6) | 285 (3.1) |

Median (interquartile range) overall follow-up was 31.7 (31.1-32.6) years; for participants with dementia, it was 27.6 (24.6-30.2) years, and for participants without dementia, it was 31.8 (31.2-32.7) years at end of follow-up.

Values are reported as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Assessed by questionnaire using the response categories shown in the table. Due to small numbers, values for Black, South Asian, and Other race/ethnicity groups were combined in analyses.

Data on risk factors at age 60 not shown for 335 participants; 6 were excluded due to dementia diagnosis before age 60 and 329 died before age 60.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Over the follow-up, 1710 participants (16.9%) developed diabetes, among whom 153 (8.9%) were subsequently diagnosed with dementia. Cumulative hazards of dementia as a function of diabetes status at ages 55, 60, 65, and 70 years are shown in eFigure 2 in the Supplement. At age 55, the dementia rate per 1000 person-years was 3.14 in participants without diabetes and 5.06 in participants with diabetes; the corresponding fully adjusted HR was 2.14 (95% CI, 1.44-3.17; eTable 2 in the Supplement). At age 70, the corresponding dementia rate was 8.85 per 1000 person-years in participants without diabetes and 13.88 in participants with diabetes (HR, 1.58 [95% CI, 1.22-2.03]). As 48.3% (826 of 1710) of diabetes cases occurred after 70 years of age, all diabetes cases were analyzed by treating diabetes and covariates as time-varying measures. In these analyses, the fully adjusted HR for dementia was 1.40 (95% CI, 1.15-1.70), and the dementia rates were 1.76 per 1000 person-years in participants without diabetes and 6.25 in participants with diabetes.

Table 2 shows results of age at onset of diabetes. At ages 60, 65, and 70 years, earlier age at diabetes onset was more strongly associated with dementia, as shown by the test for linear trend (all P < .001). In fully adjusted analyses compared with participants without diabetes at age 65 (dementia rate, 5.70/1000 person-years), diabetes onset from 0 to 5 years earlier was significantly associated with subsequent dementia (HR, 1.53 [95% CI, 1.03-2.29]; dementia rate, 8.63/1000 person-years), as well as diabetes onset 6 to 10 years earlier (HR, 2.03 [95% CI, 1.48-2.79]; dementia rate, 10.51/1000 person-years). When diabetes status at age 70 was considered, the HR of dementia in participants with diabetes onset more than 10 years earlier was 2.12 (95% CI, 1.50-3.00 [dementia rate, 18.30/1000 person-years]), in participants with diabetes onset 6 to 10 years earlier the HR was 1.49 (95% CI, 0.95-2.32 [dementia rate, 12.99/1000 person-years]), and in participants with diabetes onset 0 to 5 years earlier the HR was 1.11 (95% CI, 0.70-1.76 [dementia rate, 10.00/1000 person-years]). At age 70, every 5-year younger age at onset of type 2 diabetes was significantly associated with an HR of dementia of 1.24 (95% CI, 1.06-1.46) in fully adjusted analyses.

Table 2. Association Between Type 2 Diabetes and Incidence of Dementia and According to Age at Diabetes Onseta.

| No diabetes | Diabetes onset ≤5 y earlier | Diabetes onset 6-10 y earlier | Diabetes onset >10 y earlierb | P value for linear trendb | 5-y younger age at onsetb,c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At age 55 y | ||||||

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 19.6 (15.6-25.1) | |||||

| Dementia cases/total cases, No.d | 611/9621 | 27/316 | ||||

| Rate/1000 person-years | 3.14 | 5.06 | ||||

| Model, HR (95% CI)e | ||||||

| 1 | 1 [Reference] | 2.33 (1.58-3.45) | ||||

| 2 | 1 [Reference] | 2.25 (1.52-3.34) | ||||

| 3 | 1 [Reference] | 2.14 (1.44-3.17) | ||||

| At age 60 y | ||||||

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 14.8 (10.8-20.2) | |||||

| Dementia cases/total cases, No.d | 585/9217 | 21/239 | 27/304 | |||

| Rate/1000 person-years | 4.07 | 6.52 | 7.14 | |||

| Model, HR (95% CI)e | ||||||

| 1 | 1 [Reference] | 2.01 (1.29-3.13) | 2.45 (1.65-3.62) | NA | <.001 | NA |

| 2 | 1 [Reference] | 2.02 (1.30-3.14) | 2.34 (1.58-3.48) | NA | <.001 | NA |

| 3 | 1 [Reference] | 1.77 (1.13-2.77) | 2.19 (1.48-3.26) | NA | <.001 | NA |

| At age 65 y | ||||||

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 10.1 (6.1-15.4) | |||||

| Dementia cases/total cases, No.d | 543/8673 | 26/305 | 46/505 | |||

| Rate/1000 person-years | 5.70 | 8.63 | 10.51 | |||

| Model, HR (95% CI)e | ||||||

| 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1.72 (1.16-2.55) | 2.32 (1.70-3.16) | NA | <.001 | NA |

| 2 | 1 [Reference] | 1.61 (1.09-2.40) | 2.21 (1.62-3.02) | NA | <.001 | NA |

| 3 | 1 [Reference] | 1.53 (1.03-2.29) | 2.03 (1.48-2.79) | NA | <.001 | NA |

| At age 70 y | ||||||

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 6.7 (3.0-11.4) | |||||

| Dementia cases/total cases, No.d | 463/6900 | 20/284 | 21/232 | 38/368 | 542/7784 | |

| Rate/1000 person-years | 8.86 | 10.00 | 12.99 | 18.30 | 9.35 | |

| Model, HR (95% CI)e | ||||||

| 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1.21 (0.77-1.90) | 1.61 (1.04-2.50) | 2.32 (1.65-3.26) | <.001 | 1.25 (1.06-1.47) |

| 2 | 1 [Reference] | 1.20 (0.76-1.88) | 1.50 (0.97-2.34) | 2.22 (1.58-3.13) | <.001 | 1.24 (1.05-1.46) |

| 3 | 1 [Reference] | 1.11 (0.70-1.76) | 1.49 (0.95-2.32) | 2.12 (1.50-3.00) | <.001 | 1.24 (1.06-1.46) |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable.

Diabetes defined as fasting blood glucose of at least 126 mg/dL (to convert to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0555), physician-diagnosed diabetes, use of antidiabetic medication, or hospital record of diabetes.

Cells marked as NA were not included in these analyses due to lack of sufficient data in these categories.

Indicates values at age 70 years, using data on diabetes over the study period, and the association between every 5-year younger age at diabetes onset and incidence of dementia.

Differences in the number of cases and noncases across age groups are due to death, dementia onset, or participants not reaching the target age at the end of follow-up (March 2019), flowchart in eFigure 1 in the Supplement.

Model 1 indicates that analysis was adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and birth cohort (5-year groups). Model 2 indicates model 1 adjustment plus adjustment for health-related behaviors (smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and diet). Model 3 indicates model 2 adjustment plus adjustment for CVD (coronary heart disease, heart failure, or stroke), hypertension, body mass index, use of antidepressants, and use of CVD drugs.

Those with younger-onset diabetes were younger at onset of dementia (eTable 3 in the Supplement). For example, when diabetes status was examined at age 65, the mean (SD) age of dementia diagnosis was 77.5 (5.3) years in participants without diabetes, 76.7 (5.5) years in participants with diabetes onset between 61 and 65 years, and 75.8 (5.5) years in participants with diabetes onset at 60 years of age or younger (P for linear trend, .02).

In additional analyses, Fine and Gray subdistribution hazard yielded results similar to that in the main analyses (eTable 4 in the Supplement). In the subsample with data on APOE genotype (6069 of 10 095), the fully adjusted HR for the association of diabetes with the incidence of dementia (eTable 5 in the Supplement) in APOE ε4 carriers was 1.34 (95% CI, 0.89-2.00; model 3) and in noncarriers, the HR was 1.39 (95% CI, 0.99-1.96; model 3) with no significant difference in associations in these 2 groups (P for interaction, .21; model 3).

The association between FINDRISC, adjusted for sociodemographic covariates, and incidence of dementia is shown in the Figure. The HR for every 5-point higher FINDRISC at ages 55, 60, 65, and 70 years did not show significant associations with dementia. Prediabetes was not significantly associated with dementia, irrespective of the age at which prediabetes was assessed (Table 3). Use of the World Health Organization threshold to define prediabetes (110-125 mg/dL) did not alter findings (eTable 6 in the Supplement). Further analysis of continuous measure of fasting blood glucose at mean (SD) age of 60 (4 years) in the 90 to 126 mg/dL range showed an HR of incident dementia of 1.31 (95% CI, 1.02-1.68) for 18 mg/dL higher fasting glucose (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). The analyses on prediabetes, fasting glucose, and FINDRISC were based on smaller numbers due to use of data from the clinical examinations, but the association between diabetes and incidence of dementia in this population (Table 3) was similar to that in the total population (Table 2).

Figure. Association of Finnish Diabetes Risk Score at Ages 55, 60, 65, and 70 Years With Incidence of Dementia.

Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and birth cohort (5-year groups). The gray shading indicates the 95% CI. All figures were produced using restricted cubic spline (4 knots) and the untransformed Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC; score range, 0-26 [age, 0-4 points; family history of diabetes, 0-5 points; vegetable and fruit intake, 0-2 points; physical activity, 0-2 points; medical treatment of hypertension, 0-2 points; history of high blood glucose, 0-5 points; body mass index, 0-3 points; and waist circumference, 0-4 points]). A rating score between 0 and 14 points indicates a low to moderate risk of diabetes, 15 to 20 points indicates a high risk of diabetes, and greater than 20 points indicates a very high risk of diabetes. The hazard ratio (HR) estimates are for a 5-point higher FINDRISC score (for age 55 y: HR, 1.16 [95% CI, 0.99-1.35]; for age 60 y: HR, 1.08 [95% CI, 0.93-1.25]; for age 65 y: HR, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.82-1.11]; and for age 70 y: HR, 0.96 [95% CI, 0.82-1.14].

Table 3. Association of Fasting Glucose–Based Prediabetes and Diabetes With Risk of Dementiaa.

| No diabetes | Prediabetes | Diabetes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| At age 55 yb | |||

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 20.7 (15.6-25.8) | ||

| Dementia cases/total cases, No.c | 276/5175 | 77/1363 | 30/318 |

| Rate/1000 person-years | 2.72 | 2.89 | 5.45 |

| Model, HR (95% CI)d | |||

| 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1.04 (0.81-1.35) | 2.16 (1.46-3.18) |

| 2 | 1 [Reference] | 1.03 (0.80-1.34) | 2.13 (1.44-3.14) |

| 3 | 1 [Reference] | 0.99 (0.76-1.28) | 2.01 (1.36-2.97) |

| At age 60 yb | |||

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 15.6 (10.7-21.0) | ||

| Dementia cases/total cases, No.c | 309/5137 | 91/1352 | 42/450 |

| Rate/1000 person-years | 3.75 | 4.15 | 7.06 |

| Model, HR (95% CI)d | |||

| 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1.10 (0.87-1.39) | 2.36 (1.69-3.30) |

| 2 | 1 [Reference] | 1.08 (0.86-1.37) | 2.34 (1.67-3.27) |

| 3 | 1 [Reference] | 1.05 (0.83-1.34) | 2.14 (1.52-3.01) |

| At age 65 yb | |||

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 10.6 (6.5-15.8) | ||

| Dementia cases/total cases, No.c | 277/4525 | 78/1166 | 46/586 |

| Rate/1000 person-years | 5.33 | 6.05 | 7.97 |

| Model, HR (95% CI)d | |||

| 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1.28 (0.99-1.65) | 1.74 (1.26-2.41) |

| 2 | 1 [Reference] | 1.27 (0.99-1.64) | 1.65 (1.19-2.29) |

| 3 | 1 [Reference] | 1.28 (0.98-1.65) | 1.60 (1.15-2.23) |

| At age 70 yb | |||

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 6.5 (3.5-10.9) | ||

| Dementia cases/total cases, No.c | 199/3607 | 66/983 | 47/620 |

| Rate/1000 person-years | 7.16 | 8.09 | 10.80 |

| Model, HR (95% CI)d | |||

| 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1.06 (0.80-1.40) | 1.55 (1.11-2.15) |

| 2 | 1 [Reference] | 1.07 (0.81-1.42) | 1.47 (1.05-2.05) |

| 3 | 1 [Reference] | 1.09 (0.82-1.45) | 1.47 (1.04-2.06) |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio; IQR, interquartile range.

Prediabetes is defined as (per the American Diabetes Association) fasting blood glucose between 100 mg/dL and 125 mg/dL (to convert to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0555).

A 5-year range was allowed around the target age to improve numbers in analyses.

Differences in the number of cases and noncases across age groups are due to death, dementia onset, or participants not reaching the target age at the end of follow-up (March 2019), flowchart in eFigure 1 in the Supplement.

Model 1 indicates that analysis was adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and birth cohort (5-year groups). Model 2 indicates model 1 adjustment plus adjustment for health-related behaviors (smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and diet). Model 3 indicates model 2 adjustment plus adjustment for CVD (coronary heart disease, heart failure, or stroke), hypertension, body mass index, use of antidepressants, and use of CVD drugs.

The analyses on cardiovascular comorbidity (CHD, heart failure, and stroke) in participants with diabetes (N = 1710) are shown in Table 4. Compared with diabetes alone (75 dementia cases in 992 persons; dementia rate, 5.18/1000 person-years), diabetes accompanied by stroke was significantly associated with higher risk of dementia (9 dementia cases in 58 persons; dementia rate, 24.32/1000 person-years; HR, 2.17 [95% CI, 1.05-4.48]). The HR was 4.99 (95% CI, 2.19-11.37) in the presence of all 3 conditions (7 dementia cases in 22 persons; dementia rate, 77.77/1000 person-years), although these analyses were based on small numbers.

Table 4. Role of Cardiovascular Comorbidities in the Association Between Diabetes (N = 1710) and Incidence of Dementiaa.

| Diabetes without stroke, CHD, or heart failure | Diabetes and CHD | Diabetes and heart failure | Diabetes and stroke | Diabetes and 2 of stroke, CHD, or heart failure | Diabetes with stroke, CHD, and heart failure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia cases/total cases, No. | 75/992 | 37/435 | 5/50 | 9/58 | 20/153 | 7/22 |

| Rate/1000 person-years | 5.18 | 8.03 | 22.01 | 24.32 | 23.18 | 77.77 |

| Model, hazard ratio (95% CI)b | ||||||

| 1 | 1 [Reference] | 0.94 (0.63-1.40) | 1.57 (0.63-3.92) | 2.07 (1.02-4.22) | 1.92 (1.16-3.18) | 5.36 (2.41-11.90) |

| 2 | 1 [Reference] | 0.92 (0.62-1.38) | 1.57 (0.63-3.95) | 1.99 (0.97-4.08) | 1.82 (1.10-3.03) | 5.08 (2.26-11.41) |

| 3 | 1 [Reference] | 0.96 (0.64-1.44) | 1.74 (0.68-4.42) | 2.17 (1.05-4.48) | 1.98 (1.18-3.33) | 4.99 (2.19-11.37) |

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio.

All cardiovascular conditions (stroke, CHD, and heart failure) and covariates are entered as time-varying variables in these analyses.

Model 1 indicates that analysis was adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and birth cohort (5-year groups). Model 2 indicates model 1 adjustment plus adjustment for health-related behaviors (smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and diet). Model 3 indicates model 2 adjustment plus adjustment for hypertension, body mass index, use of antidepressants, and use of CVD drugs.

Discussion

In this longitudinal study, younger age at onset of diabetes was significantly associated with a higher HR of dementia. Data spanning 35 to 75 years for age of diabetes onset showed every 5-year earlier onset of diabetes was significantly associated with higher hazard of dementia. Late-onset diabetes was not significantly associated with subsequent dementia. Other key findings include the lack of a robust association of dementia with preclinical diabetes (prediabetes or fasting glucose) or the FINDRISC in participants without diabetes, irrespective of age at assessment. In addition, in individuals with diabetes, stroke comorbidity was associated with additional increased risk of dementia. Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of age at onset of diabetes and cardiovascular comorbidity in persons with diabetes for risk of dementia.

Meta-analyses of the association between type 2 diabetes and dementia reported a risk ratio between 1.43 and 1.62.4,5,6,7,8 These estimates are in line with results in the present study of a hazard ratio of 1.52 (model 1 in eTable 2 in the Supplement) when all diabetes cases were considered in the analyses, including those occurring after 70 years of age. The population-attributable fraction of 1.1% for diabetes in the recent Lancet Commission was based on a risk ratio of 1.5 and prevalence of diabetes at 6.4%.12 Both the risk ratio and the prevalence of type 2 diabetes may not be generalizable. The HR of dementia for diabetes onset at or before age 60 in the present study was 1.99 in fully adjusted analyses. The global prevalence of diabetes is estimated at 15% at ages 55 to 59 years and at 20% or greater starting from age 65.22 In the UK, prevalence was 19.3% in 2014/2015.23 The results of the present study suggest that a population-attributable fraction of 1.1% in the study by Livingston and colleagues12 is likely to be an underestimate, particularly in settings where the prevalence of early onset type 2 diabetes is high.

To date, studies that explicitly consider age at diabetes onset or diabetes duration remain scarce, primarily because studies on dementia recruit participants older than 65 years and age at diabetes onset is not known with precision or not taken into consideration. One exception is the Swedish Twin Registry study in which record of diabetes before 65 years (OR, 2.41 [95% CI 1.05-5.51]) but not after 65 years (OR, 0.68 [95% CI, 0.30-1.53]) was associated with higher risk of dementia.24 Results from the US ARIC study, based on persons aged 66 to 90 years at start of follow-up, suggest longer diabetes duration to be associated with higher risk of dementia only in the youngest age tertile.25 Longer duration of diabetes has also been associated with faster cognitive decline.26,27 Careful analysis of age of diabetes onset in the present study, along with explicit examination of duration of diabetes, showed a graded association between age at onset of diabetes and dementia risk.

Results from previous studies on prediabetes and dementia are inconsistent; a meta-analysis found associations with incident dementia (RR, 1.18 [95% CI, 1.02-1.36]) but not cognitive impairment (RR, 0.96 [95% CI, 0.85-1.09]).8 Another study on fasting glucose in adults older than 65 years without diabetes found higher average rather than fasting glucose levels within the preceding 5 years to be related to a higher risk of dementia (HR, 1.18 [95% CI, 1.04-1.33]) at 115 mg/dL compared with 99 mg/dL.28 The present study did not show robust evidence of an association between prediabetes and dementia. It is possible that fasting glucose within the normal range does not adversely affect brain function. Fasting blood glucose in those without diabetes has been shown to be only modestly associated with risk of vascular disease.2 A certain threshold of high glucose levels may be necessary for hyperglycemia-induced brain injury.29

As diabetes is associated with higher risk for a wide range of vascular diseases,2 it is important to consider whether vascular comorbidity is associated with onset of dementia in those with diabetes. The Swedish National Study on Aging30 examined the risk of dementia in participants with diabetes and any cardiovascular comorbidity compared with nondiabetic participants and found that the higher risk among those with diabetes could not be attributed to cardiovascular comorbidity on its own. This finding led to use of an analysis strategy in the present study that allowed the examination of risk for 1 or more cardiovascular comorbidities in participants with diabetes. Stroke combined with diabetes was associated with a higher risk of dementia, and the highest risk of dementia was seen in those with stroke, CHD, and heart failure. These results highlight the need to address cardiovascular comorbidity in individuals with diabetes.

The precise mechanisms underlying the association between type 2 diabetes and dementia remain unclear. Further, studies do not always show a consistent association between diabetes and hallmarks of Alzheimer disease, such as amyloid and tau pathology.31 Although the histopathological, molecular, and biochemical abnormalities in Alzheimer disease are well characterized, a unified framework that links these features is lacking. There are several possible explanations for the association between type 2 diabetes and dementia. One hypothesis is that brain metabolic dysfunction is the primary driver of Alzheimer disease,32 highlighting the role of decreased transport of insulin through the blood-brain barrier, impairments in insulin signaling, and consequently decreased cerebral glucose utilization.33,34 Insulin resistance is a key feature of diabetes but also dementia, as suggested by the widespread distribution of insulin receptors in the brain.34 This assumes that systemic and brain insulin resistance are linked, a hypothesis supported by a recent cross-sectional study on middle-aged adults that reported insulin resistance to be associated with lower regional cerebral glucose metabolism, determined using fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET).35 Impaired peripheral insulin action leads to hyperglycemia, which may affect dementia risk due to glucose neurotoxicity, vascular injury, and accumulation of advanced glycation end products.29 Another hypothesis highlights the role of microvascular dysfunction, which leads to inflammatory and immune responses, oxidative stress, increased blood-brain permeability, and altered blood flow regulation.36 In addition, episodes of hypoglycemia,37 particularly in relation to type 2 diabetes treatment using insulin,38 are more likely to occur in longer duration diabetes thereby increasing risk of dementia. The pathophysiological changes in dementia unfold over a long period and how diabetes in early and midlife contributes to these processes needs further research.

The strengths of this study include precise measures of diabetes from midlife to old age and the long follow-up for dementia. Ascertainment of dementia in all participants rather than those who continue to participate in the study was possible due to linkage to electronic health records and is likely to yield results that are less affected by selection bias. Undiagnosed diabetes, estimated to be 50% globally and between 20% and 35% in Europe,22 was unlikely to be a concern in the present study due to repeated clinical examinations. Furthermore, the availability of a range of covariates via repeated clinical examinations allowed minimization of bias due to confounders.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the inability to distinguish dementia subtypes precluded estimation of the association of diabetes with Alzheimer disease and major subtypes of dementia such as vascular dementia. Second, participants in longitudinal studies tend to be healthier than the general population; in the present study, rates of diabetes (16.5%) and dementia (6.3%) were lower than the general UK population. While representative studies are necessary for estimating prevalence and incidence of disease, this is not the case when the aim of the analysis is to examine the association between an exposure and an outcome,39,40 as shown by the association between diabetes (time-varying exposure) and dementia in the present study (being in the range of previous findings from meta-analyses). Third, data on glycated hemoglobin, a more stable marker of diabetes status, were available only in the later study waves and could not be used for diabetes diagnosis. Fourth, dementia ascertainment was based on linkage to electronic health records rather than an in-person screening. This method is likely to miss milder cases of dementia, but it has the advantage of allowing analysis on everyone recruited to the study rather than only those who continue to participate over the course of the study. Electronic health records used in this study contain information on both health and social care, and have national coverage precluding major bias in estimation of the association between type 2 diabetes and dementia. Fifth, the age of participants at the end of the follow-up (69-89 years) implies that younger participants have not yet reached an age when dementia is more prevalent. Continuing follow-up in the study will allow further examination of the importance of age at onset of type 2 diabetes for dementia.

Conclusions

In this longitudinal cohort study with a median follow-up of 31.7 years, younger age at onset of diabetes was significantly associated with higher risk of subsequent dementia.

eTable 1. Scoring of the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC)

eTable 2. Association of Diabetes* Status at 55, 60, 65, and 70 Years and Over the Total Follow-up With the Risk of Dementia

eTable 3. Age at Onset of Dementia as a Function of Age at Diabetes Onset (55, 60, 65, and 70 Years)

eTable 4. Association Between Type 2 Diabetes and Incidence of Dementia Using Fine & Gray Models for Competing Risk

eTable 5. Association of Diabetes With Incidence of Dementia (Analyses Restricted to Those With Data on APOE Genotype; N=6069)

eTable 6. Association of Fasting Glucose-Based Prediabetes (WHO Definition) and Diabetes With Risk of Dementia

eFigure 1. Flow Chart of Sample Selection

eFigure 2. Cumulative Hazards (Nonadjusted Nelson-Aalen) of Dementia as a Function of Age at Onset of Diabetes

eFigure 3. Association (95% CI) of Fasting Blood Glucose (5 to 7 mmol/l) With Incidence of Dementia in Those Without Diabetes Diagnosis at 60 Years

References

- 1.Chatterjee S, Khunti K, Davies MJ. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2017;389(10085):2239-2251. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30058-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SR, et al. ; Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration . Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet. 2010;375(9733):2215-2222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60484-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao Kondapally Seshasai S, Kaptoge S, Thompson A, et al. ; Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration . Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(9):829-841. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng G, Huang C, Deng H, Wang H. Diabetes as a risk factor for dementia and mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Intern Med J. 2012;42(5):484-491. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02758.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterjee S, Peters SA, Woodward M, et al. Type 2 diabetes as a risk factor for dementia in women compared with men: a pooled analysis of 2.3 million people comprising more than 100 000 cases of dementia. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(2):300-307. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, Chen C, Hua S, et al. An updated meta-analysis of cohort studies: diabetes and risk of alzheimer’s disease. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;124:41-47. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kivimäki M, Singh-Manoux A, Pentti J, et al. ; IPD-Work consortium . Physical inactivity, cardiometabolic disease, and risk of dementia: an individual-participant meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;365:l1495. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xue M, Xu W, Ou YN, et al. Diabetes mellitus and risks of cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 144 prospective studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;55:100944. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2019.100944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sattar N, Rawshani A, Franzén S, et al. Age at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus and associations with cardiovascular and mortality risks. Circulation. 2019;139(19):2228-2237. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huo X, Gao L, Guo L, et al. Risk of non-fatal cardiovascular diseases in early-onset versus late-onset type 2 diabetes in China: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(2):115-124. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00508-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tancredi M, Rosengren A, Svensson AM, et al. Excess mortality among persons with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(18):1720-1732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413-446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koopman RJ, Mainous AG III, Diaz VA, Geesey ME. Changes in age at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the United States, 1988 to 2000. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(1):60-63. doi: 10.1370/afm.214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marmot MG, Smith GD, Stansfeld S, et al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 1991;337(8754):1387-1393. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabák AG, Jokela M, Akbaraly TN, Brunner EJ, Kivimäki M, Witte DR. Trajectories of glycaemia, insulin sensitivity, and insulin secretion before diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: an analysis from the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2215-2221. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60619-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindström J, Tuomilehto J. The diabetes risk score: a practical tool to predict type 2 diabetes risk. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):725-731. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sommerlad A, Perera G, Singh-Manoux A, Lewis G, Stewart R, Livingston G. Accuracy of general hospital dementia diagnoses in England: sensitivity, specificity, and predictors of diagnostic accuracy 2008-2016. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(7):933-943. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkinson T, Ly A, Schnier C, et al. ; UK Biobank Neurodegenerative Outcomes Group and Dementias Platform UK . Identifying dementia cases with routinely collected health data: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(8):1038-1051. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. 2016;133(6):601-609. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau B, Cole SR, Gange SJ. Competing risk regression models for epidemiologic data. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(2):244-256. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrell FE, Jr. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. Springer; 2001. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3462-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Standl E, Khunti K, Hansen TB, Schnell O. The global epidemics of diabetes in the 21st century: current situation and perspectives. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26(2_suppl):7-14. doi: 10.1177/2047487319881021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diabetes UK . Facts and Stats. Revised October 2016. Accessed April 6, 2021. https://diabetes-resources-production.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/diabetes-storage/migration/pdf/DiabetesUK_Facts_Stats_Oct16.pdf

- 24.Xu W, Qiu C, Gatz M, Pedersen NL, Johansson B, Fratiglioni L. Mid- and late-life diabetes in relation to the risk of dementia: a population-based twin study. Diabetes. 2009;58(1):71-77. doi: 10.2337/db08-0586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rawlings AM, Sharrett AR, Albert MS, et al. The association of late-life diabetes status and hyperglycemia with incident mild cognitive impairment and dementia: the ARIC study. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(7):1248-1254. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rawlings AM, Sharrett AR, Schneider AL, et al. Diabetes in midlife and cognitive change over 20 years: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):785-793. doi: 10.7326/M14-0737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuligenga RH, Dugravot A, Tabák AG, et al. Midlife type 2 diabetes and poor glycaemic control as risk factors for cognitive decline in early old age: a post-hoc analysis of the Whitehall II cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(3):228-235. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70192-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crane PK, Walker R, Hubbard RA, et al. Glucose levels and risk of dementia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(6):540-548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamed SA. Brain injury with diabetes mellitus: evidence, mechanisms and treatment implications. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2017;10(4):409-428. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2017.1293521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z, Marseglia A, Shang Y, Dintica C, Patrone C, Xu W. Leisure activity and social integration mitigate the risk of dementia related to cardiometabolic diseases: a population-based longitudinal study. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(2):316-325. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beeri MS, Bendlin BB. The link between type 2 diabetes and dementia: from biomarkers to treatment. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(9):736-738. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30267-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cunnane SC, Trushina E, Morland C, et al. Brain energy rescue: an emerging therapeutic concept for neurodegenerative disorders of ageing. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(9):609-633. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-0072-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kellar D, Craft S. Brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders: mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(9):758-766. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30231-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnold SE, Arvanitakis Z, Macauley-Rambach SL, et al. Brain insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer disease: concepts and conundrums. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(3):168-181. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willette AA, Bendlin BB, Starks EJ, et al. Association of insulin resistance with cerebral glucose uptake in late middle-aged adults at risk for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):1013-1020. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.0613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Sloten TT, Sedaghat S, Carnethon MR, Launer LJ, Stehouwer CDA. Cerebral microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes: stroke, cognitive dysfunction, and depression. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(4):325-336. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30405-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yaffe K, Falvey CM, Hamilton N, et al. ; Health ABC Study . Association between hypoglycemia and dementia in a biracial cohort of older adults with diabetes mellitus. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(14):1300-1306. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McMillan JM, Mele BS, Hogan DB, Leung AA. Impact of pharmacological treatment of diabetes mellitus on dementia risk: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2018;6(1):e000563. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2018-000563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rothman KJ, Gallacher JE, Hatch EE. Why representativeness should be avoided. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):1012-1014. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Batty GD, Shipley M, Tabák A, et al. Generalizability of occupational cohort study findings. Epidemiology. 2014;25(6):932-933. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Scoring of the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC)

eTable 2. Association of Diabetes* Status at 55, 60, 65, and 70 Years and Over the Total Follow-up With the Risk of Dementia

eTable 3. Age at Onset of Dementia as a Function of Age at Diabetes Onset (55, 60, 65, and 70 Years)

eTable 4. Association Between Type 2 Diabetes and Incidence of Dementia Using Fine & Gray Models for Competing Risk

eTable 5. Association of Diabetes With Incidence of Dementia (Analyses Restricted to Those With Data on APOE Genotype; N=6069)

eTable 6. Association of Fasting Glucose-Based Prediabetes (WHO Definition) and Diabetes With Risk of Dementia

eFigure 1. Flow Chart of Sample Selection

eFigure 2. Cumulative Hazards (Nonadjusted Nelson-Aalen) of Dementia as a Function of Age at Onset of Diabetes

eFigure 3. Association (95% CI) of Fasting Blood Glucose (5 to 7 mmol/l) With Incidence of Dementia in Those Without Diabetes Diagnosis at 60 Years