Abstract

Purpose:

Fatigue and anxiety are common and significant symptoms reported by cancer patients. Few studies have examined the trajectory of multidimensional fatigue and anxiety, the relationships between them and with quality of life.

Methods:

Breast cancer patients (n=580) from community oncology clinics and age-matched controls (n=364) completed fatigue and anxiety questionnaires prior to chemotherapy (A1), at chemotherapy completion (A2), and six months post-chemotherapy (A3). Linear mixed models (LMM) compared trajectories of fatigue /anxiety over time in patients and controls and estimated their relationship with quality of life. Models adjusted for age, education, race, BMI, marital status, menopausal status, and sleep symptoms.

Results:

Patients reported greater fatigue and anxiety compared to controls at all time points (p’s<0.001, 35% clinically meaningful anxiety at baseline). From A1 to A2 patients experienced a significant increase in fatigue (β=8.3 95%CI 6.6,10.0) which returned to A1 values at A3 but remained greater than controls’ (p<0.001). General, mental, and physical fatigue subscales increased from A1 to A2 remaining significantly higher than A1 at A3 (p<0.001). Anxiety improved over time (A1 to A3 β=−4.3 95%CI −2.6,−3.3) but remained higher than controls at A3 (p<0.001). Among patients, fatigue and anxiety significantly predicted one another and quality of life. Menopausal status, higher BMI, mastectomy, and sleep problems also significantly predicted change in fatigue.

Conclusion:

Breast cancer patients experience significant fatigue and anxiety up to six-months post-chemotherapy that is associated with worse quality of life. Future interventions should simultaneously address anxiety and fatigue; focusing on mental and physical fatigue sub-domains.

Introduction

Cancer and its treatments are associated with several common psychosocial symptoms that impact quality of life including cancer-related fatigue (CRF) and anxiety. CRF is often debilitating and is characterized by persistent physical, emotional, and/or cognitive tiredness that is not proportional to recent physical activity.[1] CRF and anxiety affect between 30% and 50% patients before, during and after treatment[2–9] and are associated with impairments in physical functioning, overall quality of life, and decision-making ability, as well as delayed return to work and poor adherence to treatment.[10–12] [13]

CRF is increasingly reported as multidimensional and is likely composed of several symptom domains including, general, emotional, mental, and physical fatigue.[14] However, studies characterizing the trajectory of CRF subdomains over time are lacking. Understanding both the timing of significant fatigue and which symptom domains are most affected can help to design tailored interventions. CRF and anxiety are often examined separately but are likely part of a complex symptom burden experienced by patients that may persist long-term. It is increasingly recognized that chronic fatigue has a large mental component with stress and anxiety predicting chronic fatigue syndrome in the general population.[15] Anxiety may contribute to CRF through dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which may increase cytokine production and subsequent fatigue.[16–18] No study to date has examined fatigue and anxiety together, including the subdomains of fatigue, over time in a nationwide sample of breast cancer patients with non-cancer controls to determine the magnitude of these symptoms relative to the non-cancer population and how long these problems persist. Characterizing the trajectories of fatigue and anxiety and how they relate to each other as well as quality of life can help clinicians and researchers develop effective interventions and determine the timing, design, and impact of interventions.

Therefore, we sought to characterize the change in clinically significant and domain-specific fatigue and anxiety in a large, well-controlled, cohort of breast cancer patients recruited from nationwide community oncology practices. We hypothesized that breast cancer patients would have more fatigue and anxiety prior to and after completion of chemotherapy compared to non-cancer controls and that baseline factors such as surgery and sleep problems would be associated with persistent fatigue. We hypothesized that the trajectory of fatigue and anxiety would be correlated, specifically that anxiety would correlate with the emotional subdomain of fatigue. Lastly, we sought to explore the associations between pre- and post-chemotherapy changes in fatigue, anxiety, and quality of life.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Breast cancer patients (n=580) were recruited as part of a longitudinal study designed to examine the impact of chemotherapy on cognitive function (URCC1055/NCT01382082). Three hundred and sixty four of these patients were 1:1 age-matched (within 5- years) to non-cancer controls (n=364) in order to balance age across the two groups; detailed methods for this study are described elsewhere. [19] Briefly, participants were recruited via 23 National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) locations nationwide between May 2011 and October 2013. Breast cancer patients had a diagnosis of invasive breast cancer (stage I to IIIC), had no metastatic or primary central nervous system disease, and were scheduled to receive chemotherapy (without concurrent radiation). Controls were female and age-matched (within 5 years). Both breast cancer patients and controls were chemotherapy naïve at baseline, ≥21 years old, and were not currently or has not been hospitalized within the past year for major psychiatric disease. Breast cancer patients completed three assessments: within 7 days prior to chemotherapy (A1), within 1 month after chemotherapy completion (A2), and six-months post-chemotherapy completion (A3). Controls were assessed at the same time intervals as patients. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Rochester Cancer Center NCORP Research Base and each NCORP location; all participants provided informed consent.

Measures

Participants completed the multidimensional fatigue symptom inventory short form (MFSI) and Spielberger State/Trait Anxiety Inventory state subdomain (STAI) at each assessment. Clinical data such as body mass index (BMI), stage, and treatment information were extracted from the medical record while demographic information was self-reported by participants at A1. Patients may have had radiation or started hormone therapy (confirmed from clinic note documentation) after completion of chemotherapy (between A2 and A3).

The MFSI is a validated 30-item self-report questionnaire designed to capture to the complex ways fatigue may manifest.[14] The MFSI has a total score as well as five subscales that assess general, physical, emotional, and mental fatigue as well as vigor (patient’s energy level) subdomains. Notably, the emotional subscale asks participants endorse items such as “I feel nervous” and “I feel cheerful”. The total score ranges from −24 to 96; a higher total score, or general, physical, emotional or mental subscale scores indicates greater fatigue and a higher score on the vigor subscale indicates less fatigue.

Anxiety was assessed with the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), a widely used, well-validated measure of anxiety.[20] This self-report measure has scores ranging from 20–80, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety. A score of ≥40 is indicative of clinically meaningful anxiety.[21]

Patients also self-reported quality of life using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Treatment-General (FACT-G) at each time point.[22] Scores range from 0 to 108 with a higher score indicating better quality of life. Lastly, patients self-reported sleep symptoms at baseline on a single question: “how severe were your sleep problem symptoms in the last seven days” on a scale from 0 (not present) to 10 (as bad as you can imagine).

Statistical Analysis

Mean scores on the MFSI total score, each subscale, and the STAI in patients and controls were compared within each time point using two-sample t-tests. Linear mixed models were employed to examine the trajectories of MFSI and STAI scores of patients compared to controls over three time points controlling for a priori identified baseline covariates.[23–25] The fixed effects were time (assessment 1, 2, and 3 as nominal), group (patient or non-cancer control), group by time interaction, and covariates including: age, education, race, BMI, marital status, menopausal status, baseline sleep, and baseline anxiety (for fatigue models) or fatigue (for anxiety models). Subject-specific mean MFSI/STAI score was the random effect, independent of residual error.

Linear mixed models were also employed to identify predictors of fatigue and anxiety in breast cancer patients. These models utilized only breast cancer patients and in addition to the variables above included stage, chemotherapy regimen (anthracycline vs. not), surgery prior to A1 (none, lumpectomy, mastectomy) and time-dependent covariates for radiation and hormone therapy. These models were also used to estimate how changes in STAI scores affected each subscale of the MFSI. Additionally, LMM were run to assess how baseline MFSI and STAI scores predicted the FACT-G over time.

Adjusted marginal means were used to explore the trajectories and quantify changes in MFSI, STAI, and FACT-G scores between time points. Restricted maximum likelihood estimation was used for all models and significance was based on F testing using the Kenward-Roger denominator degrees of freedom procedure. Lastly, to preliminarily explore how trajectories of fatigue, anxiety, and quality of life overlap over time, we examined Pearson correlations between changes in MFSI, STAI, and FACT-G scores between each time point. All hypotheses testing was two-sided.

Results

Among the 944 participants included for analyses (97.9% participation rate), 504 breast cancer patients and 333 controls had MFSI and STAI data at all three assessments (88.3%, Figure 1). Group differences in the magnitude of loss to follow up were minimal and similar in both groups.[26]

Figure 1:

Participant Enrollment and Completion Flowchart

Baseline Characteristics and Analyses of Fatigue and Anxiety

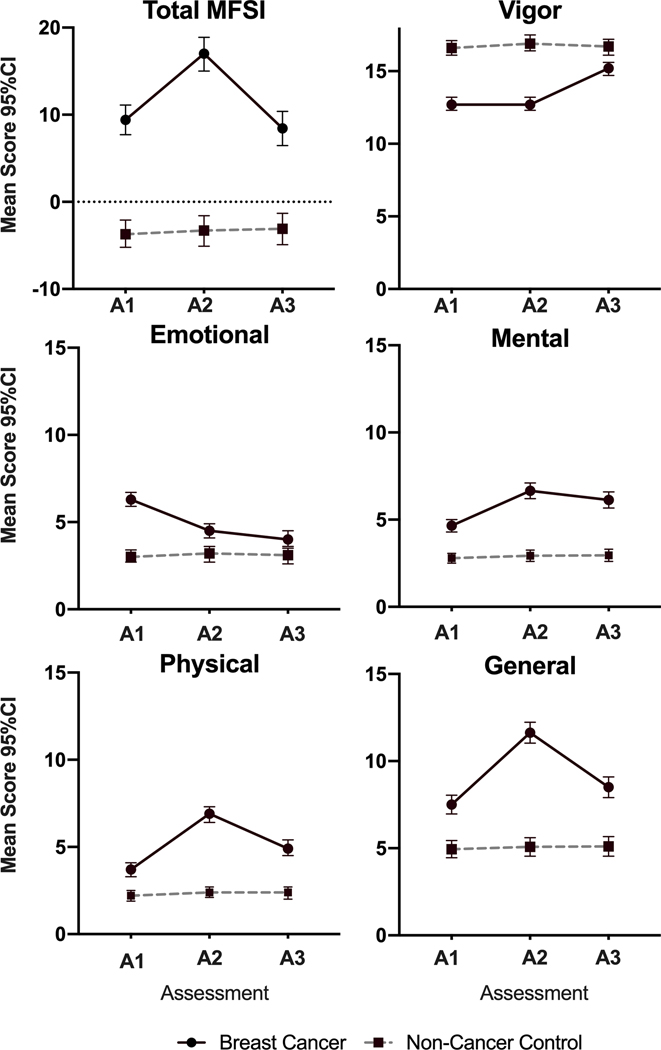

Breast cancer patients and non-cancer controls were similar in age, marital status, and menopausal status. Ten percent of breast cancer patients were not White compared to 5.8% in controls (p=0.025), however, Hispanic ethnicity was similar in the two groups (p=0.975). The majority of breast cancer patients were Stage II (49.1%) and had surgery prior to study initiation (82.8%). Total MFSI and STAI scores were significantly higher (worse) in the breast cancer patients compared to controls (9.42 vs −3.45 and 36.00 vs. 28.28 respectively, both p<0.001, Figures 2 and 3A). Additionally, scores on each subscale of the MFSI were significantly worse than controls (all p<0.001, Figure 2). Thirty-five percent of participants were classified as having clinically meaningful anxiety (score >40, Figure 3B), compared to only 12.9% of controls respectively (p<0.001).

Figure 2: Trajectories of MFSI total and subscale scores.

Mean total and subscale scores in breast cancer patients (solid line) and non-cancer controls (dotted line) for each of three time points. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Note: Breast cancer patients perform worse at all time points compared to non-cancer controls (all p<0.001). A1: Assessment 1 (pre-chemotherapy); A2: Assessment 2 (post chemotherapy); A3: Assessment 3 (6 months post-chemotherapy); MFSI: Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory.

Figure 3: Trajectories of STAI scores and percentages with clinically meaningful anxiety.

Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Breast cancer patients have higher STAI scores at all time points compared to non-cancer controls (all p<0.001). Assessment 1 (pre-chemotherapy); A2: Assessment 2 (post chemotherapy); A3: Assessment 3 (6 months post-chemotherapy); STAI: State Trait Anxiety Inventory

Longitudinal Analyses

At each time point, breast cancer patients had worse fatigue (on the total MFSI and all subscales) and anxiety compared to non-cancer controls (all p<0.001, Figures 2 and 3). In the adjusted LMMs, compared to controls, breast cancer patients had greater increases in fatigue (total MFSI) from A1 to A2 (β=7.87, 95%CI 5.81, 9.93) and a slight non-significant decrease in fatigue from A1 to A3 (β=−1.16, 95%CI-3.28, 0.95; Table 2). Importantly, total MFSI scores in breast cancer patients at A3 remained significantly higher than controls (p<0.001). This same pattern followed for the emotional and vigor subscales. For the general, mental, and physical subscales, LMMs revealed that patients experienced a greater increase from A1 to A2 and from A1 to A3 compared to controls (Table 2). A3 values remained higher than A1 values for all three subscales (p<0.001, Figure 2).

Table 2:

Linear mixed models results, estimated adjusted marginal mean difference (and 95% confidence intervals) in STAI and MFSI scores comparing breast cancer patients and controls over time.

| Total MFSI | MFSI General Subscale | MFSI Mental Subscale | MFSI Emotional Subscale | MFSI Physical Subscale | MFSI Vigor Subscale | Total STAI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparing A2 to A1 | β (95%CI) | β (95%CI) | β (95%CI) | β (95%CI) | β (95%CI) | β (95%CI) | β (95%CI) |

| Breast Cancer (BC) | 8.28(6.59,9.96)* | 4.29(3.69,4.90)* | 2.16(1.78,2.55)* | −1.64(−2.01,−1.26)* | 3.30(2.85,3.76)* | −0.13(−0.59,0.32) | −3.09 (−4.05, −2.13)* |

| Healthy Controls | 0.40(−0.79,1.60) | 0.21(−0.20,0.64) | 0.10(−0.15,0.35) | 0.14(−0.19,0.46) | 0.28(−0.01,0.56) | 0.31(−0.11,0.74) | −0.11 (−0.97, 0.75) |

| Change in BC vs. Healthy Controls | 7.87(5.81,9.93)* | 4.07(3.34,4.81)* | 2.07(1.61,2.52)* | −1.77(−2.52,−1.71)* | 3.02(2.49,3.56)* | −0.45(−1.07,0.17) | −2.98 (−4.26, −1.70)* |

| Comparing A3 to A1 | |||||||

| Breast Cancer (BC) | −0.23 (−1.89,1.43) | 1.13(0.59,1.67)* | 1.62(1.21,2.03)* | −2.11(−2.52,−1.71)* | 1.40(0.99,1.81)* | 2.30(1.84,2.77)* | −4.28 (−2.58, −3.28)* |

| Healthy Controls | 0.94(−0.40,2.25) | 0.40(−0.07,0.86) | 0.12(−0.14,0.38) | 0.07(−0.29,0.44) | 0.31(−0.01,0.62) | −0.04(−0.52,0.44) | −0.40 (−1.34, 0.54) |

| Change in BC vs. Healthy Controls | −1.16(−3.28,0.95) | 0.74(0.02,1.45)* | 1.50(1.02,1.98)* | −2.19(−2.73,−1.64)* | 1.09(0.57,1.60)* | 2.34(1.68,3.01)* | −3.88 (−5.25, −2.51)* |

| Type III effects | |||||||

| Time | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Group | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Time*Group | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

indicates p<0.05

A1: assessment 1 prior to chemotherapy, A2: assessment 2 after completion of therapy, A3: assessment 3 six months after completion of chemotherapy.

All models adjusted for age, BMI, race, education, marital status, menopausal status, baseline sleep and baseline anxiety (for the CRF models) or fatigue (for the anxiety (STAI) models).

Anxiety among breast cancer patients appeared highest at diagnosis and declined over time, but remained higher than controls (p<0.001, Figure 3A). Overall, controls experienced little change. At A2 and A3, 31% and 30% of patients had clinically significant anxiety compared to 16% and 19% of controls. In the adjusted LMMs, breast cancer patients had greater declines in anxiety from A1 to A2 (β=−2.98, 95%CI −4.26, −1.70) and A1 to A3 (β=−3.88, 95%CI −2.52, −2.51) compared to controls (Table 2). Statistically significant group by time interactions in both fatigue and anxiety models indicated that these differences in trajectory between patients and controls are statistically significant (Table 2).

Predictors of Fatigue and Anxiety in Breast Cancer Patients

In LMM analyses, time, menopausal status, higher BMI, surgery type, and sleep problems significantly predicted the total MFSI score (Supplemental Table 3). Compared to those who did not have surgery, those who had a mastectomy prior to A1 had significantly more fatigue (β=4.19, 95%CI 1.17, 5.66). There was no difference in fatigue among women who had a bilateral mastectomy compared to a unilateral mastectomy (β=−0.38, 95%CI −4.12, 3.37). Sleep problems were associated worse MFSI scores (β=1.85 95%CI 1.46, 2.04). Demographic and treatment covariates did not significantly predict STAI (Supplemental Table 3).

Interrelationship of Fatigue and Anxiety Across Time Points

In the adjusted LMM, baseline STAI score was associated with an increase in total MFSI score over time (β=1.03, 95%CI 0.94, 1.12, Supplemental Table 3) as well as each subscale of the MFSI (Supplemental Table 1). Interestingly, baseline STAI score was associated with an increase in the MFSI emotional subscale over time (β=0.25 95%CI 0.23, 0.27). Similarly, baseline total MFSI score was associated with an increase in STAI score over time (β=0.41 95%CI 0.38, 0.44 Supplemental Table 3).

Changes in STAI and MFSI scores correlated well from A1 to A2, A1 to A3, and A2 to A3 (Supplemental Table 2). The strongest correlation was between changes in STAI score and the emotional subscale of the MFSI at each interval (r=0.61, 0.64, 0.54 respectively). This was followed by moderate correlations between the STAI and the total MFSI (r=0.53, 0.59, 0.49) and vigor subscale (r=−0.49, −0.53, −0.48).

Quality of Life

Higher baseline total MFSI and STAI scores were significantly associated with worse quality of life at baseline as measured by the FACT-G (Supplemental Table 1; fatigue β=−0.45 95%CI −0.42,−0.49; anxiety β=−0.57, 95%CI −0.51,−0.63). Changes in total MFSI scores from A1 to A2, A1 to A3, and A2 to A3 correlated strongly with changes in FACT-G scores (r=−0.72, −0.78, and −0.73 respectively, all p<0.001, Supplemental Table 2). Changes in total STAI score correlated moderately with changes in FACT-G at these time points (r=−0.45, −0.51, −0.51 respectively, all p<0.001).

Discussion

The goal of this study was to characterize domain-specific fatigue and anxiety trajectories in a large nationwide cohort of community oncology patients. We report that breast cancer patients experienced significantly more fatigue pre-chemotherapy, and greater increases in fatigue from pre- to post-chemotherapy compared to non-cancer controls. Six months after chemotherapy, overall fatigue returned to baseline levels in breast cancer patients, however, this was still clinically significantly greater than non-cancer controls. Further, general, mental, and physical fatigue subscales worsened over time. Breast cancer patients experienced an improvement in anxiety symptoms from pre- to six months post-chemotherapy, however, anxiety levels remained significantly higher than non-cancer controls (30% of patients reported clinically meaningful anxiety vs. 18.7%). Fatigue and anxiety correlated with each other and predicted worse quality of life, highlighting the need for a multidimensional intervention in this population.

We report here a clinically meaningful increase in fatigue from pre- to post-chemotherapy.[27] Importantly, at six-months post-chemotherapy, general, mental, and physical fatigue subscale scores all remained significantly worse than pre-chemotherapy values in breast cancer patients (controls experienced no change) while the emotional and vigor subscales showed a steady improvement over all three time points. Of the two other existing longitudinal studies of fatigue in patients with breast cancer with non-cancer controls [9, 28] only Liu and colleagues examined the longitudinal trajectory of fatigue symptoms domains. They report similar significant increases in the general, physical, and mental subscales of the MFSI from pre-chemotherapy to chemotherapy completion (e.g. A2). They also report a non-significant improvement in the emotional subscale similar in magnitude to our findings. Ours is the first longitudinal study to describe improvement but not complete resolution of symptom domain specific fatigue in the post-chemotherapy period (e.g. 6 months post-chemotherapy). Future studies are needed to characterize whether overall fatigue and symptom domains of fatigue persist or improve to pre-chemotherapy levels or better beyond 6 months post-chemotherapy.

Similar to published studies, we report that breast cancer patients experience anxiety pre-chemotherapy and anxiety declines up to six months after chemotherapy.[7, 29–34] However, the average level of anxiety remains significantly higher 6 months after chemotherapy than non-cancer controls, consistent with data from a small longitudinal cohort of breast cancer patients and non-cancer controls.[35] Baseline fatigue was the only significant predictor of anxiety; stage, treatment exposures, and demographics did not appear to influence anxiety levels. Interestingly, baseline anxiety significantly predicted fatigue at all time points and the trajectory of anxiety mirrored the trajectory of the emotional subscale, and to a lesser degree, the vigor subscale of the MFSI. Anxiety and fatigue may be associated due to shared biologic mechanisms. Specifically, anxiety may induce fatigue through dysregulation of the HPA-axis. Continued stimulation of the HPA-axis from external and internal stressors during treatment may result in depletion of cortisol and impaired cortisol secretion.[36] Low cortisol levels have been associated with increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines among those with underactive HPA-axes[37] and pro-inflammatory cytokines have been implicated in the etiology of CRF.[17, 18] Our novel data suggests interventions aimed at alleviating anxiety may also help to alleviate symptoms of fatigue and vice versa.

While some interventions have been shown to be effective in reducing fatigue, targeted, refined, and more effective interventions are needed. Understanding both the timing of significant fatigue, which symptom domains are most affected, and who is at highest risk of fatigue can help to not only design effective interventions at appropriate time points but also help to identify underlying physiologic mechanisms. For example, if physical fatigue persists at six months and emotional fatigue does not, interventions that involve physical activity may be most effective, compared to interventions for emotional fatigue. However, prior to chemotherapy and during chemotherapy when emotional fatigue is higher, interventions aimed at alleviating anxiety may be most useful. Given the meaningful increase in fatigue at completion of therapy reported here and previously reported associations between physical and emotional fatigue and ability to return to work,[38, 39] intervention studies should focus on alleviating fatigue and anxiety during treatment to increase a patient’s ability to complete all recommended treatment cycles and return to work and prior activities.

Understanding predictors of fatigue can aid in targeting appropriate populations for intervention. Similar to previous studies, women who had a mastectomy reported significantly more fatigue at all time points and represent a potential population to target and design specific interventions for.[40] Further, our data suggests that those with a higher BMI have worse fatigue and might benefit from exercise interventions aimed at lowering fatigue and improving overall health.[41, 42] Consistent with our results, other studies have reported associations between sleep and fatigue warranting additional research on alleviating fatigue via improved sleep.[43–47]

These data are limited by the lack of a true treatment naïve baseline. As mentioned, factors such as surgery were significantly associated with fatigue and we may therefore be overestimating the true magnitude of fatigue. However, recent data from the Nurse’s Health Study report significant functional declines from pre-breast cancer diagnosis to post-treatment.[48] Additionally, we lack a measure of depression and depressive symptoms in this population, which are likely associated with both fatigue and anxiety. Despite the wide geographic representation throughout the nation, our sample was comprised of only 11% racial minorities limiting the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, metastatic breast cancer patients were excluded from this cohort. Fatigue and anxiety may manifest differently this population and warrants further study. The current study only extends to six months post-chemotherapy. Long-term cross-sectional studies of breast cancer patients suggest that fatigue can persist for many years after treatment and additional studies are warranted to determine the biological and psychological predictors of chronic fatigue.[49–51] A subset of participants from the URCC10055 studyare being followed currently to examine the trajectory of longer-term fatigue and anxiety up to 10 years post treatment. We also noted that change in fatigue correlated strongly with decreasing quality of life scores, but that baseline fatigue and anxiety predicted quality of life similarly. This suggests that increases in fatigue are important for quality of life and additional research on individual trajectories of fatigue and anxiety and their association with quality of life are needed. Given the complex interplay between sleep, mood, and fatigue additional large-scale well-controlled studies are needed to fully characterize the long-term impact and burden of these symptom clusters, predictors of long-term symptoms, and potential interventions.

This large, nationally representative, well-controlled study of fatigue and anxiety in breast cancer patients confirms previous research on the trajectory of fatigue, specifically that fatigue persists up to 6 months after chemotherapy compared to non-cancer controls. Our sample was recruited from nationwide community oncology sites that were not in academic medical centers, increasing the generalizability of this patient population and is representative of where the majority of breast cancer patients are treated. We also used a multidimensional assessment of fatigue which takes into account the physical, mental, and emotional manifestations of fatigue. We explored relationships between fatigue, anxiety, and quality of life over time in breast cancer patients. Our study expands the current literature by demonstrating the interrelatedness of fatigue and anxiety and highlights the need for multidimensional interventions that can simultaneously improve fatigue and anxiety.

Conclusion

These results from the largest well-controlled study to date showed that breast cancer patients experience significantly more fatigue and anxiety prior to and after chemotherapy compared to non-cancer controls and these symptoms are associated with one another and quality of life. Specifically, we showed that anxiety and emotional fatigue are most prevalent early on in treatment and physical and mental fatigue persists for months after treatment. Further research should aim to identify effective time-specific interventions to mitigate fatigue and anxiety at various points in the disease course to improve patient outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Table 1:

Participant characteristics

| All | Breast Cancer Patients | Healthy Controls | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | ||

| N (%) | 944 | 580 | 364 | |

| Age (mean (SD)) | 53.1 (10.5) | 53.4 (10.6) | 52.6 (10.3) | 0.250 |

| BMI (mean (SD)) 1 | 29.74 (7.2) | 30.20 (7.4) | 29.00 (6.8) | 0.013 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 860 (91.1) | 517 (89.1) | 343 (94.2) | 0.024 |

| Black | 64 (6.8) | 47 (8.1) | 17 (4.7) | |

| Other | 20 (2.1) | 16 (2.8) | 4 (1.1) | |

| Ethnicity2 | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 12 (1.3) | 7 (1.2) | 5(2.7) | 0.975 |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 919 (98.7) | 565 (98.8) | 354 (97.3) | |

| Education | ||||

| <8th Grade | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Some High School | 10 (1.1) | 10 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| High School GED | 173 (18.3) | 130 (22.4) | 43 (11.8) | |

| Some College | 351 (37.2) | 194 (33.5) | 157 (43.1) | |

| College | 248 (26.3) | 140 (24.1) | 108 (29.7) | |

| Graduate | 161 (17.0) | 105 (18.1) | 56 (15.4) | |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married or Long-term Relationship | 698 (69.4) | 421 (72.6) | 277 (76.1) | 0.293 |

| Divorced or Separated | 126 (11.2) | 86 (14.8) | 40(11.0) | |

| Widowed | 45 (4.8) | 28 (4.8) | 17 (4.7) | |

| Single | 75 (7.9) | 45 (7.8) | 30 (8.2) | |

| Menopausal Status | ||||

| Pre-Menopausal | 286 (30.3) | 181 (31.2) | 105 (28.9) | 0.139 |

| Peri-Menopausal | 88 (9.3) | 45 (7.8) | 43 (11.8) | |

| Post-Menopausal | 481 (51.0) | 303 (52.2) | 178 (48.9) | |

| Medically induced | 89 (9.4) | 51 (8.8) | 38 (10.4) | |

| Stage | ||||

| I | N/A | 157 (27.1) | N/A | |

| II | 285 (49.1) | |||

| III | 108 (18.6) | |||

| Unknown | 30 (5.2) | |||

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| Anthracycline | N/A | 279 (48.1) | N/A | |

| Non-Anthracycline | 301 (51.9) | |||

| Surgery prior to Chemotherapy (A1)3 | ||||

| None | N/A | 100 (17.2) | N/A | |

| Lumpectomy | 184 (31.7) | |||

| Mastectomy | 296 (51.0) | |||

| Radiotherapy (from A2 to A3)4 | ||||

| Yes | N/A | 285 (56.5) | N/A | |

| No or unknown (unknown is <5%) | 219 (43.5) | |||

| Hormone therapy (from A2 to A3)4 | ||||

| Yes | N/A | 329 (56.7) | N/A | |

| No or unknown (unknown is <5%) | 251 (43.3) |

BMI: body mass index, GED: graduate education development, A1:assessment 1 prior to chemotherapy, A2: assessment 2 after completion of therapy, A3: assessment 3 six months after completion of chemotherapy.

4 participants missing BMI,

13 participants missing ethnicity,

1 participant missing surgery type,

N=504 from A2 to A3.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DP2CA195765 to M.C.J.), and the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (F99CA222742 to A.M.W., R01CA231014 to M.C.J.). We thank the participants in this study and all staff at the University of Rochester Cancer Center National Cancer Institute (NCI) Community Clinical Oncology Research Program (NCORP) Research Base and our NCORP affiliate sites who recruited and observed participants. We thank the National Cancer Institute Clinical Community Oncology Program (CCOP) and NCORP programs for their funding and support of this project. The following CCOP/NCORPs participated in this study: Central Illinois, Columbus, Cancer Research Consortium of West Michigan, Dayton, Delaware, Grand Rapids, Greenville, Hematology-Oncology Associates of Central New York, Kalamazoo, Kansas City, Marshfield, Metro Minnesota, Nevada, North Shore, Pacific Cancer Research Consortium, Southeast Cancer Control Consortium, Southeast Clinical Oncology Research Consortium, Upstate Carolina, Virginia Mason, Wichita, Wisconsin NCORP, and Western Oncology Research Consortium.

Declarations

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DP2CA195765 to M.C.J.), and the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (F99CA222742 to A.M.W., R01CA231014 to M.C.J.).

The role of the funder: The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decisions to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Rochester Cancer Center NCORP Research Base and each NCORP location; the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments

Consent to Participate: All participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for Publication: Not Applicable.

Availability of Data and Material: Please contact the authors for any questions related to data.

Code Availability: SAS Code is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bower JE, Bak K, Berger A, et al. Screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: an American Society of Clinical oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol 2014;32(17):1840–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butt Z, Rosenbloom SK, Abernethy AP, et al. Fatigue is the most important symptom for advanced cancer patients who have had chemotherapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2008;6(5):448–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yi JC, Syrjala KL. Anxiety and Depression in Cancer Survivors. The Medical clinics of North America 2017;101(6):1099–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganz PA, Bower JE. Cancer related fatigue: a focus on breast cancer and Hodgkin’s disease survivors. Acta Oncol 2007;46(4):474–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minton O, Stone P. How common is fatigue in disease-free breast cancer survivors? A systematic review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;112(1):5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puigpinos-Riera R, Graells-Sans A, Serral G, et al. Anxiety and depression in women with breast cancer: Social and clinical determinants and influence of the social network and social support (DAMA cohort). Cancer Epidemiol 2018;55:123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saboonchi F, Petersson LM, Wennman-Larsen A, et al. Changes in caseness of anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients during the first year following surgery: patterns of transiency and severity of the distress response. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2014;18(6):598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsaras K, Papathanasiou IV, Mitsi D, et al. Assessment of Depression and Anxiety in Breast Cancer Patients: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2018;19(6):1661–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ancoli-Israel S, Liu L, Rissling M, et al. Sleep, fatigue, depression, and circadian activity rhythms in women with breast cancer before and after treatment: a 1-year longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer 2014;22(9):2535–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curt GA. Impact of fatigue on quality of life in oncology patients. Semin Hematol 2000;37(4 Suppl 6):14–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolvers MDJ, Leensen MCJ, Groeneveld IF, et al. Predictors for earlier return to work of cancer patients. J Cancer Surviv 2018;12(2):169–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee MK, Kang HS, Lee KS, et al. Three-Year Prospective Cohort Study of Factors Associated with Return to Work After Breast Cancer Diagnosis. J Occup Rehabil 2017;27(4):547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, et al. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol 2000;18(4):743–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stein KD, Jacobsen PB, Blanchard CM, et al. Further validation of the multidimensional fatigue symptom inventory-short form. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004;27(1):14–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, et al. Fatigue in Breast Cancer Survivors: Occurrence, Correlates, and Impact on Quality of Life. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2000;18(4):743–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris G, Anderson G, Maes M. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Hypofunction in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) as a Consequence of Activated Immune-Inflammatory and Oxidative and Nitrosative Pathways. Mol Neurobiol 2017;54(9):6806–6819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bower JE. The role of neuro-immune interactions in cancer-related fatigue: Biobehavioral risk factors and mechanisms. Cancer 2019;125(3):353–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Aziz N, et al. Fatigue and proinflammatory cytokine activity in breast cancer survivors. Psychosom Med 2002;64(4):604–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janelsins MC, Heckler CE, Peppone LJ, et al. Longitudinal Trajectory and Characterization of Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment in a Nationwide Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol 2018; 10.1200/jco.2018.78.6624:Jco2018786624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R., Vagg PR, & Jacobs GA (1983). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Addolorato G, Ancona C, Capristo E, et al. State and trait anxiety in women affected by allergic and vasomotor rhinitis. J Psychosom Res 1999;46(3):283–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 1993;11(3):570–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerber LH, Stout N, McGarvey C, et al. Factors predicting clinically significant fatigue in women following treatment for primary breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 2011;19(10):1581–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inglis JE, Janelsins MC, Culakova E, et al. Longitudinal assessment of the impact of higher body mass index on cancer-related fatigue in patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2019; 10.1007/s00520-019-04953-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsaras K, Papathanasiou IV, Mitsi D, et al. Assessment of Depression and Anxiety in Breast Cancer Patients: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP 2018;19(6):1661–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janelsins MC, Heckler CE, Peppone LJ, et al. Cognitive Complaints in Survivors of Breast Cancer After Chemotherapy Compared With Age-Matched Controls: An Analysis From a Nationwide, Multicenter, Prospective Longitudinal Study. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(5):506–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan A, Yo TE, Wang XJ, et al. Minimal Clinically Important Difference of the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form (MFSI-SF) for Fatigue Worsening in Asian Breast Cancer Patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55(3):992–997.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu L, Rissling M, Neikrug A, et al. Fatigue and Circadian Activity Rhythms in Breast Cancer Patients Before and After Chemotherapy: A Controlled Study. Fatigue 2013;1(1–2):12–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villar RR, Fernandez SP, Garea CC, et al. Quality of life and anxiety in women with breast cancer before and after treatment. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2017;25:e2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ng CG, Mohamed S, See MH, et al. Anxiety, depression, perceived social support and quality of life in Malaysian breast cancer patients: a 1-year prospective study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015;13:205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyranou M, Puntillo K, Dunn LB, et al. Predictors of initial levels and trajectories of anxiety in women before and for 6 months after breast cancer surgery. Cancer Nurs 2014;37(6):406–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis LE, Bubis LD, Mahar AL, et al. Patient-reported symptoms after breast cancer diagnosis and treatment: A retrospective cohort study. Eur J Cancer 2018;101:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hopwood P, Sumo G, Mills J, et al. The course of anxiety and depression over 5 years of follow-up and risk factors in women with early breast cancer: results from the UK Standardisation of Radiotherapy Trials (START). Breast 2010;19(2):84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saboonchi F, Petersson LM, Wennman-Larsen A, et al. Trajectories of Anxiety Among Women with Breast Cancer: A Proxy for Adjustment from Acute to Transitional Survivorship. J Psychosoc Oncol 2015;33(6):603–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kreukels BP, van Dam FS, Ridderinkhof KR, et al. Persistent neurocognitive problems after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer 2008;8(1):80–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fries E, Hesse J, Hellhammer J, et al. A new view on hypocortisolism. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005;30(10):1010–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaudhuri A, Behan PO. Fatigue in neurological disorders. Lancet 2004;363(9413):978–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dumas A, Luis IMVD, Bovagnet T, et al. Return to work after breast cancer: Comprehensive longitudinal analyses of its determinants. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2019;37(15_suppl):11564–11564. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindbohm ML, Kuosma E, Taskila T, et al. Early retirement and non-employment after breast cancer. Psychooncology 2014;23(6):634–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bower JE, Asher A, Garet D, et al. Testing a biobehavioral model of fatigue before adjuvant therapy in women with breast cancer. Cancer 2019;125(4):633–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mustian KM, Alfano CM, Heckler C, et al. Comparison of Pharmaceutical, Psychological, and Exercise Treatments for Cancer-Related Fatigue: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 2017;3(7):961–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kleckner IR, Dunne RF, Asare M, et al. Exercise for Toxicity Management in Cancer-A Narrative Review. Oncol Hematol Rev 2018;14(1):28–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu L, Mills PJ, Rissling M, et al. Fatigue and sleep quality are associated with changes in inflammatory markers in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Brain Behav Immun 2012;26(5):706–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roscoe JA, Kaufman ME, Matteson-Rusby SE, et al. Cancer-related fatigue and sleep disorders. Oncologist 2007;12 Suppl 1:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ancoli-Israel S, Moore PJ, Jones V. The relationship between fatigue and sleep in cancer patients: a review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2001;10(4):245–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berger AM, Kuhn BR, Farr LA, et al. Behavioral therapy intervention trial to improve sleep quality and cancer-related fatigue. Psychooncology 2009;18(6):634–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu LM, Amidi A, Valdimarsdottir H, et al. The Effect of Systematic Light Exposure on Sleep in a Mixed Group of Fatigued Cancer Survivors. J Clin Sleep Med 2018;14(1):31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kroenke CH, Rosner B, Chen WY, et al. Functional impact of breast cancer by age at diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 2004;22(10):1849–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andrykowski MA, Donovan KA, Laronga C, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and characteristics of off-treatment fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Cancer 2010;116(24):5740–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, et al. Fatigue in long-term breast carcinoma survivors: a longitudinal investigation. Cancer 2006;106(4):751–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alfano CM, Imayama I, Neuhouser ML, et al. Fatigue, inflammation, and omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid intake among breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(12):1280–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.