Abstract

The movement of tropomyosin over filamentous actin regulates the cross-bridge cycle of the thick with thin filament of cardiac muscle by blocking and revealing myosin binding sites. Tropomyosin exists in three, distinct equilibrium states with one state blocking myosin-actin interactions (blocked position) and the remaining two allowing for weak (closed position) and strong myosin binding (open position). However, experimental information illuminating how myosin binds to the thin filament and influences tropomyosin’s transition across the actin surface is lacking. Using metadynamics, we mimic the effect of a single myosin head binding by determining the work required to pull small segments of tropomyosin toward the open position in several distinct regions of the thin filament. We find differences in required work due to the influence of cardiac troponin T lead to preferential binding sites and determine the mechanism of further myosin head recruitment.

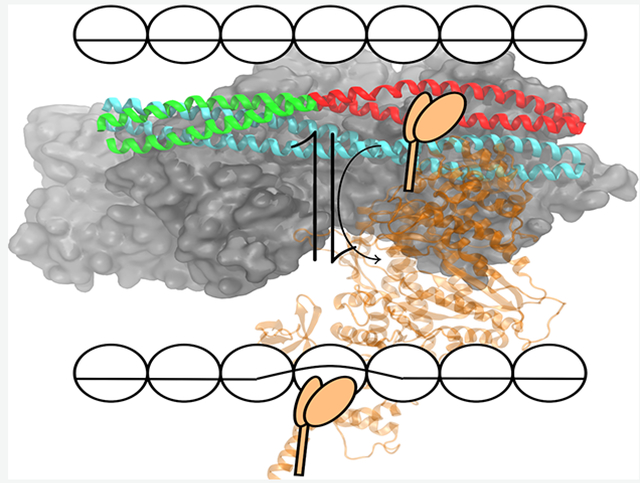

Graphical Abstract

The cardiac thin filament (CTF) is a multisubunit protein complex that acts as an important allosteric regulator for muscle contraction.1 Conformational changes within the protein complex initiated through allosteric pathways are crucial for association with the thick filament, composed of myosin, and subsequent movement between the two filaments. The thin filament is composed of three subunits: actin, tropomyosin (Tm), and the troponin (Tn) complex. Preceding muscle contraction, the troponin complex favors the placement of tropomyosin in a conformation with respect to the actin surface2 that helps prevent myosin association. An increase in cytoplasmic calcium concentration causes calcium to bind to troponin C (TnC) within the troponin complex, resulting in conformational changes within the complex that modulates the interactions between Tm and actin. The movement of Tm over the actin surface of the cardiac thin filament regulates the cross-bridge cycle by alternately blocking and revealing myosin binding sites on the surface of the actin filament.

During the transition, tropomyosin has been shown to exist in three distinct, equilibrium states: blocked, closed, and open positions. First described in the three-state model3 as the dominant equilibrium states of the thin filament, multiple cryoelectron microscopy4,5 (CEM) images have allowed visualization of tropomyosin-actin interactions in these positions, but little is known about the mechanism of the transition between these states. Tm translation has also been explored previously utilizing computational methods, but only the actin-Tm complex was considered.6,7 Understanding this process to the level of single myosin head binding is vital to discovering the underlying recruitment involved in thick filament binding and the eventual generation of force.

We have previously utilized our atomistic structure of the CTF to visualize Tm transitioning over the actin surface to determine the most probable path for traversing.8 Steered molecular dynamics (SMD) simulations were utilized to determine relative free energy changes for the entire Tm coiled coil to move along longitudinal and azimuthal paths with respect to the major axis of the actin filament as well as a third path intermediate to the two previous paths in the direction of the blocked position → closed → open. It was concluded that the most direct path, the azimuthal direction, was the likely candidate with an initially large amount of work required because of the landscape of the actin surface, but overall this was the lowest free energy path. In this study, we further expand the examination to study the effect of single or multiple myosin binding events. With respect to the thin filament, it has been shown that myosin, when it is strongly bound, largely interacts with a single actin monomer but does contain contacts with the adjacent monomer.9,10 Also because of tropomyosin having a pseudorepeating structure, there seems to be little variation in the available binding sites in the Tm-actin complex. If preferential binding sites are available to enhance binding, the effect of the troponin complex must be considered. In particular, the effect of cardiac troponin T (cTnT), a protein of the troponin complex that connects the allosteric core of the complex with tropomyosin, must be taken into account. Recent studies have illuminated the orientation of the troponin complex within the thin filament and have provided greater insight into the structure of the thin filament,11–13 with the study by Yamada et al.13 illustrating calcium depleted and calcium abundant states of the thin filament.

The work described here measures the free energy difference of tropomyosin’s transition from the blocked state to a myosin bound state using metadynamics.14,15 Both SMD and metadynamics are enhanced sampling methods to sample transitions that take place at time scales longer than can be observed computationally with conventional molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and from which relative free energies can be computed. The major difference between the two methods and other types of enhanced sampling methods is the type of bias that is employed, with SMD utilizing a harmonic bias and Jarzynski’s equality16 to determine free energies and metadynamics using a history-dependent Gaussian bias to directly sample the potential energy surface along a reaction coordinate. If similar reaction coordinates are chosen with SMD and metadynamics to study long time scale phenomena, one would expect to get equivalent results. However, we have found the limitations of SMD require infinitely slow pulling and infinite computed trajectories, and we have found the method overestimates barriers for the tropomyosin movement process with realistically accessible pulling parameters.

In order to mimic myosin binding to the CTF in this work, small segments of the tropomyosin chain, approximately 40 residues in length, were moved via metadynamics from an initial blocked position to a myosin bound (M) state in two locations on actin: the linker region and overlap region of the CTF. These two sites were chosen because of the differing secondary structure of cTnT in these regions and can be visualized in Figure 1. In the overlap region, where two Tm dimers meet in a head-to-tail fashion, cTnT takes on an α-helical structure. However, in the linker region cTnT is highly flexible and unstructured and turns away from tropomyosin. The differences in the structure (chemical and physical) of cTnT might play a differential role in stabilizing Tm on the actin surface and affect the required work that must be exerted to transition from one position to another.

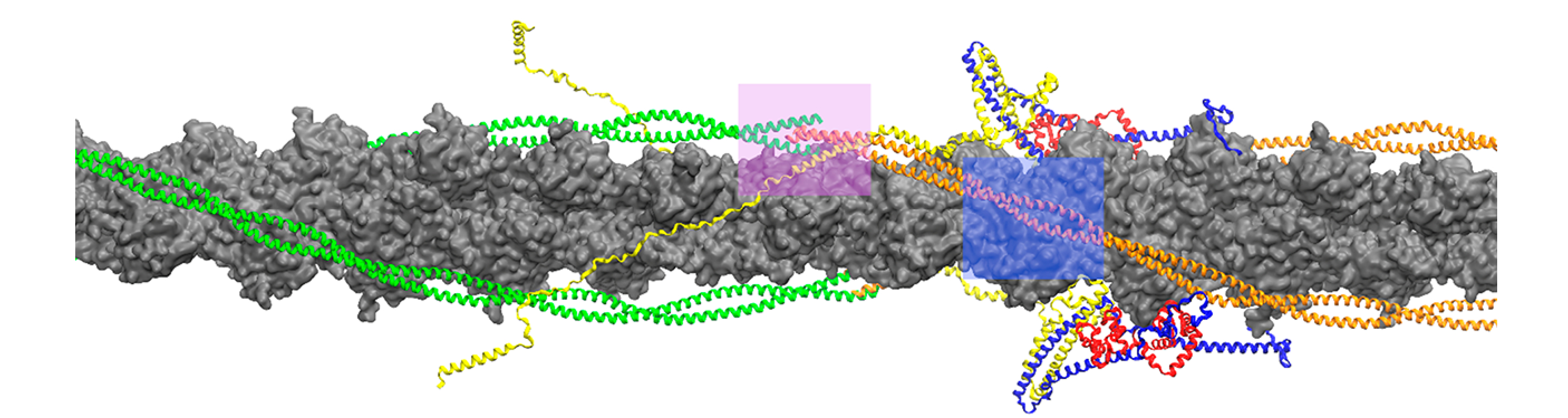

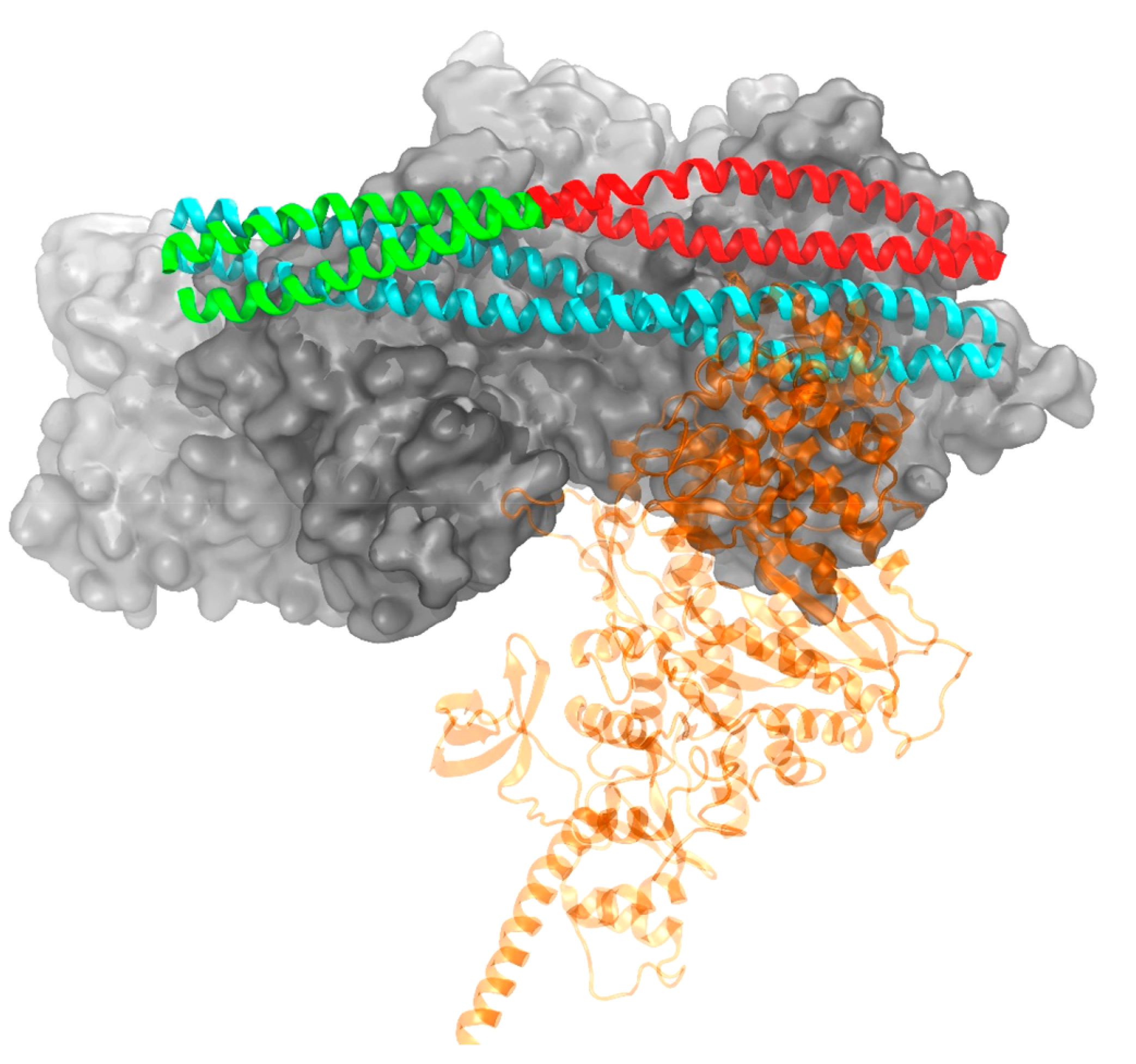

Figure 1.

Organization of tropomyosin (orange/green), troponin complex (yellow, red, and blue) and actin (gray) in the cardiac thin filament. Overlap and linker regions where tropomyosin and troponin T (yellow) interact are highlighted in pink and blue, respectively.

Additionally, we mimicked a second myosin head binding in a second site after the initial binding event in the linker position to determine to what degree successive myosin binding events are performed cooperatively. The free energy profiles (FEP) for the single myosin binding event can be split into three regions: an initial traverse away from its initial position, a plateau region, and a final hill to the M-state. The collective variable (CV) for the metadynamics simulations was defined as the center of mass (COM) distance of tropomyosin from its respective final position. A CV value of zero denotes the final position.

Though they provided additional insight, the atomic coordinates of Tm utilized by Yamada et al.13 in their determination of the thin filament has been shown to be over compressed12 and therefore does not accurately represent the canonical structure of Tm. Additionally, large segments of cTnT remain unresolved and therefore are excluded from their structure. Rightfully, we updated our previous atomic model17 to reorient the troponin core, as demonstrated by the aforementioned previous studies,11,13 and created a complete calcium-depleted model of the thin filament with the canonical structure of Tm as observed by Li et al.18 while using previous actin-myosin-tropomyosin19 (ATM) structures as targets for the Tm pulling.

To model myosin-induced Tm translation along the thin filament, we created a hybrid model in which Tm exists in its blocked, calcium-depleted state, but the troponin core is in its calcium-abundant conformation. This represents a state of the thin filament in which calcium binding has occurred in the troponin core and the subsequent conformational changes within the core have taken place, but Tm has not shifted. Therefore, tropomyosin sits in its blocked, calcium-depleted state, but without specific interactions from the C-terminal end of cardiac troponin I (cTnI), another protein of the troponin complex, keeping it constrained in this position, Tm can quickly move away from this initial state. The free energy profile for both Tm movement in the linker and overlap positions decreases from the blocked state, suggesting a destabilization at the blocked state as shown in Figure 2.

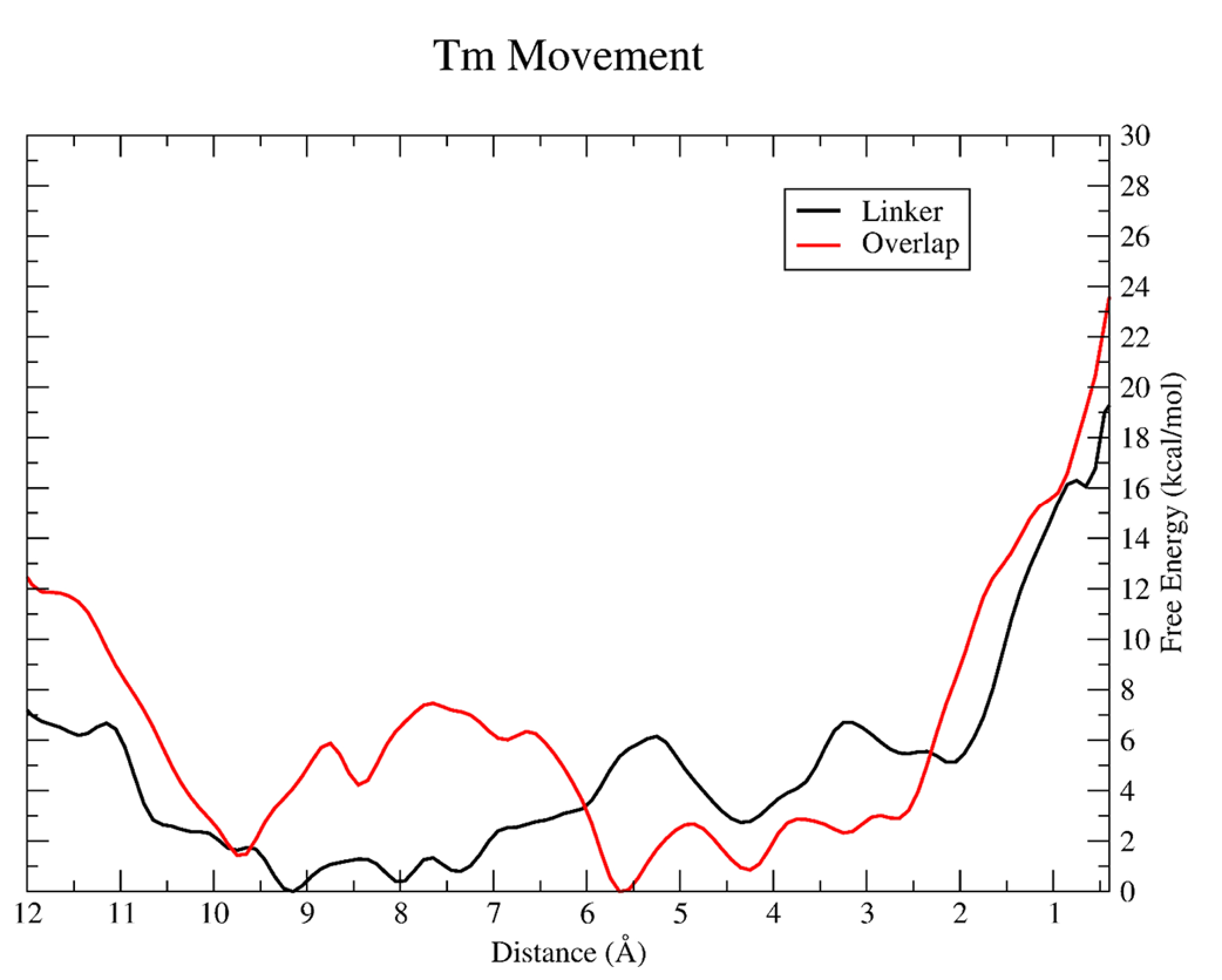

Figure 2.

Resulting PMF for tropomyosin segment pulling in the linker (black) and overlap (red). The CV defined in both simulations is the center of mass of a subset of α carbons from the Tm chain (linker: Tm residues 180 to 220; overlap: Tm residues 266 to 284 from the C-terminal chain and residues 1 to 35 from the N-terminal chain) shown here as a distance in angstroms. A CV value of zero denotes the final M-state. The free energy (ΔG) is given in units of kcal/mol.

As tropomyosin moves along the actin surface after being shifted from the blocked state, little work is exerted on the chains within the range of 3–10 Å from the M-state. In both the overlap and linker positions, the FEP slightly increases between 4 and 6 kcal/mol respectively, which accounts for 20% and 25% of the total free energy change. This relatively little work exerted on tropomyosin during this 7 Å region of the transition might allow the myosin head to efficiently search for contacts along the actin surface in its weak binding state that has been categorized previously.20,21 The features in the FEPs within this region are likely due to the actin-Tm contacts that are made and overcome as Tm moves across the actin surface. Specifically, actin residues Glu326 and Glu328 were observed coming in close contact with Tm side chains. Pavadai et al.12 noted as well the orientation and proximity of these residues within the actin-Tm interface when comparing the blocked and closed states of Tm.

Within the last few angstroms from tropomyosin’s M-state, the change in free energy increases sharply for both Tm movement events, accounting for the remaining 75%-80% of the required work. Within this region, strong tensile forces from the other regions of the Tm chain still near the blocked position restrain further movement, therefore requiring more work to overcome. As similarly observed for the initial Tm movement, this final change in free energy is greater for the overlap transition. This leads to an overall free energy change of ~24 kcal/mol for Tm displacement from a blocked state to an M-state in the overlap, while the barrier for the linker is closer to ~19 kcal/mol. Because the portion of the Tm chain near the linker region is nearly devoid of troponin T, while TnT is more closely associated within the overlap, it can stabilize Tm on the actin surface and therefore lead to greater work required to move Tm along the thin filament during muscle contraction regulation.

However, because of the large free energy barrier for tropomyosin movement, the process of Tm translocation along the actin surface from the blocked state to the M-state cannot proceed purely thermally. The formation of specific myosin-thin filament interactions offset the initial high energetic cost of moving Tm for the process to occur. Measured interaction energies between rigor myosin and the CTF showed the inclusion of these myosin-CTF interactions stabilizes the system by a factor of approximately −1100 kcal/mol, with myosin-actin interactions accounting for ~80% of this total contribution. Though not directly comparable to the computed FEPs, the interaction energies illustrate how the large barriers for tropomyosin movement may be offset by the formation of strong myosin-thin filament interactions, leading to engagement between the two filaments and subsequent muscle contraction.

Finally, we were able to observe a mechanism of additional myosin binding recruitment. With an initial myosin docked explicitly in the linker position, we studied the transition of a second segment of tropomyosin, termed the cooperative transition, directly between the linker and overlap segments toward the M-state. As Figure 3 reveals, the kinetics of the cooperative Tm movement is different from the initial transition with the overall change in free energy across the mechanism coordinate steadily increasing. There is no longer a ~7 kcal/mol decrease over the first few angstroms of the transition, but instead the cooperative FEP begins near the free energy minimum. From there, the FEP oscillates from 4 to 10 Å from the M-state, but with a slightly positive ΔG over this region. From 4 Å onward, there is a steady increase in the FEP to the final M-state.

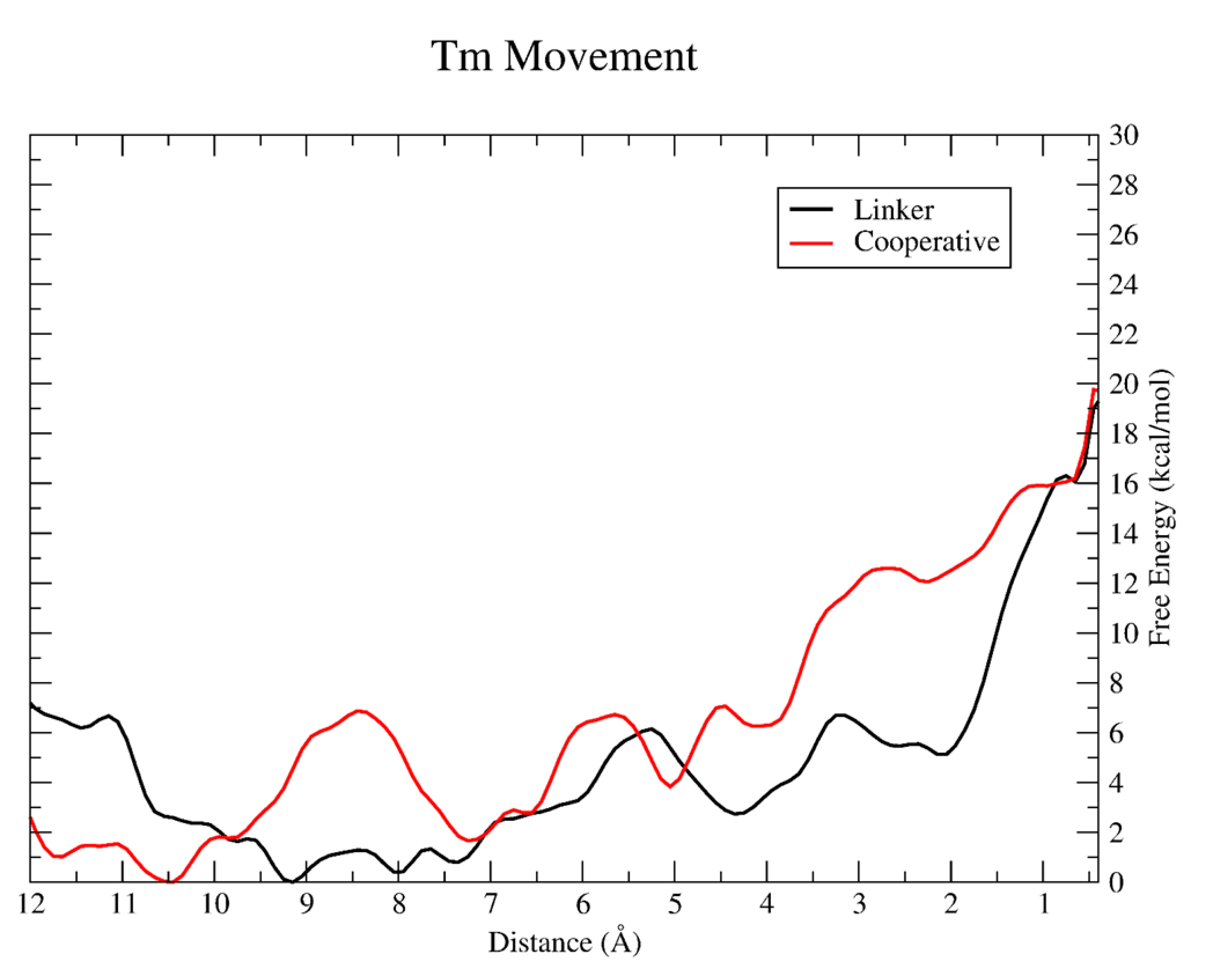

Figure 3.

Resulting PMF for tropomyosin pulling in the linker (black) and cooperative (red) simulation.

The overall change in free energy for cooperative Tm movement is nearly identical to the initial Tm movement in the linker region, approximately 20 kcal/mol. However, what we would expect to occur is that further myosin binding would decrease the overall barrier for Tm binding as more of the Tm chain is displaced from its initial position. This can at least be seen visually from the structure of the thin filament when myosin is explicitly docked after the linker segment of Tm is shifted. Figure 4 shows the segment of Tm that is biased for the cooperative movement is slightly displaced because of the previous segment of Tm movement and subsequent myosin binding in the linker. This displacement is minimal, with overall the center of mass of this segment of Tm still remaining near the blocked state, and therefore, it still traverses the same distance as the initial Tm movement in the linker. This observation agrees with previous studies that have shown single myosin head binding is insufficient for cooperative recruitment of thick filament to the thin filament and most likely occurs after two heads are bound.22,23 As additional Tm movement and myosin binding occurs, this initial displacement grows larger for each new binding site, requiring the overall distance required to move each Tm segment to reveal the actin binding surface for additional myosin binding to decrease, therefore decreasing the required work to move Tm.

Figure 4.

Conformations of tropomyosin in a blocked (cyan) position and at the end of a metadynamics simulation (green/red) mimicking a single myosin head (transparent for clarity) binding. The green portion of Tm illustrates the segment biased in the cooperative simulation, while red was biased in the linker simulation. Troponin not shown for clarity.

The work described herein further illuminates the importance of the troponin complex to the overall function of the CTF as well as how it can influence myosin’s behavior. For myosin to bind to the CTF, tropomyosin must be moved out of the way and residue-residue contacts must be made between myosin and the CTF to further hold tropomyosin in its M-state. This displacement of Tm proceeds azimuthally with respect to the actin surface, observed in this study and previously.8 Once myosin binds, the power stroke of the crossbridge cycle may proceed and lead to an overall contraction of the sarcomere. The troponin complex, largely through TnT, plays an active role in both of these processes. In the overlap region of the thin filament, where the C-terminal end of one Tm dimer intersects with the N-terminal end of the next dimer and with TnT in close association, the overall work to move tropomyosin to expose the actin surface for myosin binding is larger than a few positions down near the linker of the thin filament. Therefore, TnT provides preferential binding locations for myosin on the actin surface, and this becomes part of the modulation of myosin binding and eventually of cardiac muscle contraction.

We also observed a mechanism for additional myosin binding recruitment to the CTF. After a single myosin head interacts with the thin filament, not only is the segment of tropomyosin where the binding event occurs displaced, but also the segment in the next available myosin binding position is slightly displaced as well. In this case, we observed a similar barrier to move a second segment of Tm after an initial myosin head is bound to the thin filament, but it is clear that subsequent binding will become cooperative, thereby decreasing the overall work required to move Tm to the M-state.

Recent work has further illuminated how the structure of the thin filament has been discussed and observed in the past.11,13 Though providing additional insight into the structure and function of the thin filament, large sections of TnT remain unresolved and therefore are left out of other models. TnT is a remarkable protein in that large portions of it are completely unstructured and therefore escape structural determination from traditional methods. These regions additionally provide great flexibility to TnT that is puzzling in how these portions may contribute to its function. TnI also plays an important role in the Tm translocation process. How the energetics of TnI and its movement are coupled to the conformational changes within the troponin core and therefore allow for Tm’s movement also requires further investigation to develop a “start-to-finish” understanding of thin filament activation. The explicit inclusion of the unstructured portions of the thin filament as well as the representation of the myosin S1 unit expands the model to observe not only the native function of the CTF but also the overall behavior of the cross-bridged complex. This takes a step closer to observing the proteins of the sarcomere together in atomistic detail, as a complete representation of each individual protein chain is necessary to develop a molecular understanding of muscle function.

Supplementary Material

■. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the support of the NIH through Grant R01HL107046.

Footnotes

COMPUTATIONAL METHODS

Detailed methods on structure preparations, refinement, and metadynamics parameters are included in the Supporting Information.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c00223. Detailed computational methods, additional structural comparisons, and further discussion of tropomyosin movement (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c00223

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Jil C. Tardiff, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, United States

Steven D. Schwartz, Department of Biomedical Engineering, The University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85724, United States.

■ REFERENCES

- (1).Tobacman LS Thin Filament-Mediated Regulation of Cardiac Contraction. Annu. Rev. Physiol 1996, 58, 447–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Gordon AM; Homsher E; Regnier M Regulation of Contraction in Striated Muscle. Physiol. Rev 2000, 80, 853–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).McKillop DF; Geeves MA Regulation of the Interaction between Actin and Myosin Subfragment 1: Evidence for Three States of the Thin Filament. Biophys. J 1993, 65, 693–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Li X; Tobacman LS; Mun JY; Craig R; Fischer S; Lehman W Tropomyosin Position on F-Actin Revealed by EM Reconstruction and Computational Chemistry. Biophys. J 2011, 100, 1005–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Risi C; Eisner J; Belknap B; Heeley DH; White HD; Schröder GF; Galkin VE Ca2+-Induced Movem Tropomyosin on Native Cardiac Thin Filaments Revealed by Cryoelectron Microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2017, 114, 6782–6787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Orzechowski M; Moore JR; Fischer S; Lehman W Tropomyosin Movement on F-Actin during Muscle Activation Explained by Energy Landscapes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 2014, 545, 63–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kiani FA; Lehman W; Fischer S; Rynkiewicz MJ Spontaneous Transitions of Actin-Bound Tropomyosin toward Blocked and Closed States. J. Gen. Physiol 2019, 151, 4–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Williams MR; Tardiff JC; Schwartz SD Mechanism of Cardiac Tropomyosin Transitions on Filamentous Actin As Revealed by All-Atom Steered Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Phys. Chem Lett. 2018, 9, 3301–3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Von Der Ecken J; Müller M; Lehman W, Manstein DJ; Penczek PA; Raunser S Structure of the F-Actin-Tropomyosin Complex. Nature 2015, 519, 114–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Fujii T; Namba K Structure of Actomyosin Rigour Complex at 5.2 Å Resolution and Insights into the ATPase Cycle Mechanism. Nat. Commun 2017, 8, 13969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Pavadai E; Rynkiewicz MJ; Ghosh A; Lehman W Docking Troponin T onto the Tropomyosin Overlapping Domain of Thin Filaments. Biophys. J 2020, 118, 325–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Pavadai E; Lehman W; Rynkiewicz MJ Protein-Protein Docking Reveals Dynamic Interactions of Tropomyosin on Actin Filaments. Biophys. J 2020, 119, 75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Yamada Y; Namba K; Fujii T Cardiac Muscle Thin Filament Structures Reveal Calcium Regulatory Mechanism. Nat. Commun 2020, 11, 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Laio A; Gervasio FL Metadynamics: A Method to Simulate Rare Events and Reconstruct the Free Energy in Biophysics, Chemistry and Material Science. Rep. Prog. Phys 2008, 71, 126601. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Laio A; Parrinello M Escaping Free-Energy Minima. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2002, 99, 12562–12566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Jarzynski C Nonequilibrium Equality for Free Energy Differences. Phys. Rev. Lett 1997, 78, 2690–2693. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Williams MR; Lehman SJ; Tardiff JC; Schwartz SD Atomic Resolution Probe for Allostery in the Regulatory Thin Filament. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2016, 113, 3257–3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Li XE; Orzechowski M; Lehman W; Fischer S Structure and Flexibility of the Tropomyosin Overlap Junction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2014, 446, 304–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Behrmann E; Müller M; Penczek PA; Mannherz HG; Manstein DJ; Raunser S Structure of the R Tropomyosin-Myosin Complex. Cell 2012, 150, 327–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Huxley HE; Kress M Crossbridge Behaviour during Muscle Contraction. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil 1985, 6, 153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Cecchi G; Griffiths PJ; Taylor S Muscular Contraction: Kinetics of Crossbridge Attachment Studied by High-Frequency Stiffness Measurements. Science 1982, 217, 70–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Kad NM; Kim S; Warshaw DM; VanBuren P; Baker JE Single-Myosin Crossbridge Interactions with Actin Filaments Regulated by Troponin-Tropomyosin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2005, 102, 16990–16995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Trybus KM; Taylor EW Kinetic Studies of the Cooperative Binding of Subfragment 1 to Regulated Actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1980, 77, 7209–7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.