Abstract

Age-related hearing loss (ARHL) is a very common sensory disability, affecting one in three older adults. Establishing a link between anatomical, physiological, and behavioral markers of presbycusis in a mouse model can improve the understanding of this disorder in humans. We measured ARHL for a variety of acoustic signals in quiet and noisy environments using an operant conditioning procedure, and investigated the status of peripheral structures in CBA/CaJ mice. Mice showed the greatest degree of hearing loss in the last third of their lifespan, with higher thresholds in noisy than in quiet conditions. Changes in auditory brainstem response thresholds and waveform morphology preceded behavioral hearing loss onset. Loss of hair cells, auditory nerve fibers, and signs of stria vascularis degeneration were observed in old mice. The present work underscores the difficulty in ascribing the primary cause of age-related hearing loss to any particular type of cellular degeneration. Revealing these complex structure-function relationships is critical for establishing successful intervention strategies to restore hearing or prevent presbycusis.

Keywords: ARHL, auditory brainstem response, cochlear degeneration, cochlear nucleus, olivocochlear, animal psychoacoustics

1. Introduction

Age-related hearing loss (ARHL), or presbycusis, is one of the most common conditions affecting the older population (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, 2016). It is characterized by a decrease in auditory sensitivity beginning with higher and then extending to lower frequencies (Gates and Mills, 2005). Once hearing loss progresses to the 2-4 kHz region, the ability to detect and identify voiceless consonants (e.g. ch), and words that contain them, deteriorates (reviewed by Huang and Tang, 2010). Frequency selectivity, or the ability of the auditory system to separate frequency components of a complex sound, also declines with ARHL, which leads to an increased susceptibility to masking noise, and a reduced or absent spatial masking release (Bacon et al., 1998; Balakrishnan and Freyman, 2008; Florentine et al., 1980; Helfer and Freyman, 2005). In humans, the onset and progression of ARHL varies widely across individuals and likely reflects the interaction of environmental insults, genetics, and ototoxic drug exposures. Animal studies offer the possibility of examining behavioral, physiological, and cognitive markers associated with ARHL while controlling for these variables. However, one major barrier to translating animal studies to humans is that hearing loss is typically assessed behaviorally in humans, whereas it is usually measured using electrophysiological proxies for behavior in animal models.

Age-related hearing deficits have been attributed to both peripheral and central mechanisms of the auditory system (Quaranta et al., 2014). Numerous studies in humans and in animal models have attempted to link peripheral degeneration patterns to pure tone threshold shifts with varying results (Henry, 2004; Ohlemiller, 2009; Ohlemiller et al., 2010). Degeneration of the cochlear sensory receptors, auditory nerve cells, and stria vascularis are the most commonly and consistently reported contributors to ARHL, but there is not always a clear correlation between cell-type-specific degeneration patterns and behaviorally measured audiometric performance (Bredberg, 1967; Crowe and Guild, 1938; Engström et al., 1987; Landegger et al., 2016; Nelson and Hinojosa, 2006; Suga and Lindsay, 1976). Central compensation may support behavioral hearing thresholds in cases of peripheral degeneration (Chambers et al., 2016; Schrode et al., 2018); however, central gain compensation may be limited in the aging auditory pathways due to loss of inhibition (Caspary et al., 2008).

One of the most common complaints in the older adult population is difficulty in detecting, discriminating, and understanding speech in noisy listening environments (Abel et al., 1990; The Committee on Hearing, Bioacoustics & Biomechanics, 1988; Dubno et al., 1984; Pichora-Fuller et al., 2006). However, most experiments demonstrating degeneration of specific structures in the auditory pathway are necessarily performed in animal models in which behavioral changes in hearing thresholds in quiet and noise are not typically evaluated. Thus, the link between sensorineural changes observed in animal studies and the behavioral outcomes observed in aging human listeners is uncertain. Furthermore, changes to olivocochlear pathways that provide anti-masking inhibitory feedback to the cochlea are rarely considered.

In the present study, we investigated the link between age-related behavioral deficits for a variety of acoustic signals in quiet and noise and the status of peripheral structures in CBA/CaJ mice. The CBA/CaJ mouse strain retains normal auditory sensitivity for pure tones and ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs) into middle adulthood (Kobrina and Dent, 2016, 2019; Prosen et al., 2003), and has been studied extensively using auditory brainstem response (ABR) measurements, and cochlear histological techniques (Henry, 2004; Ohlemiller et al., 2010; Ohlemiller et al., 2016). Recent reports that CBA/CaJ mice show a decline in the central innervation of the brain by the auditory nerve in middle age raise the possibility of age-related deficits in more complex aspects of hearing in this strain which have not been assessed (Muniak et al., 2018). In addition, behavioral studies show that CBA/CaJ mice exhibit an onset of hearing loss much later in the lifespan (after 592 days of age) than was previously measured using electrophysiological techniques (Henry, 2004; Kobrina and Dent, 2019). Using behavioral techniques, we tracked the trajectory of hearing in quiet and noise, since aging humans often complain of hearing in noise deficits before they complain about issues with hearing in quiet environments (Dubno et al., 1984; Gates and Mills, 2005). We compared these perceptual assessments to more commonly used ABR measurements and performed quantitative anatomical assessments of the cochlea to relate functional deficits to structural changes.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

A total of 48 (22 M, 26 F) adult CBA/CaJ mice were used in the behavioral portion of this study. CBA/CaJ mice live up to 3 years of age, or 1095 days old (d.o. hereafter), and can retain hearing ability late into their lifespans (Kobrina and Dent, 2016, 2019; Ohlemiller et al., 2010). In this experiment adult mice ranging from 60 d.o. through 996 d.o. were studied. The original breeding pairs were acquired from The Jackson Laboratory. Half of the experimental animals were trained for these behavioral tasks exclusively, while others were obtained after participating in other behavioral studies in our laboratory. There were no differences in duration of training or maximum performance (hit and false alarm rates) observed in the previously trained mice.

Behavioral subjects were bred in a low-traffic vivarium at the University at Buffalo, SUNY, individually housed, and kept on a reversed 12:12 day/night cycle. Thirty-four subjects (13 M, 21 F) began training and testing when they were 60 to 90 days old. An additional 14 mice (9 M, 5 F) were trained between 180 d.o. and 365 d.o.. During testing, the mice were water restricted to approximately 90% of their free-watering weights. The animals had unrestricted access to food, except while participating in the experiment. All procedures were approved by the University at Buffalo, SUNY’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and complied with the ARRIVE guidelines and the associated NIH guide for the care and use of laboratory animals.

A total of 99 adult male and female CBA/CaJ mice bred and housed in a low traffic vivarium at Johns Hopkins University (Lauer et al., 2009) were used for the ABR and anatomical experiments. Mice were housed in groups or individually with ad libitum access to food and water and kept on a 12:12 hr light cycle. ABRs were measured at 40-139 d.o. and 606-788 d.o., just prior to tissue harvest. This age range for older mice was chosen because behavioral deficits are observable, but not severe, while previous studies have shown a sharp decline in ABR thresholds after 550 d.o. (18 months) in this strain (Li and Borg, 1991; Zheng et al., 1999). All procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and complied with the ARRIVE guidelines and the associated NIH guide for the care and use of laboratory animals.

2.2. Behavioral experiment

Behavioral thresholds were calculated to determine the auditory acuity of awake and motivated mice. Procedures were similar to those described by Radziwon et al. (2009) and Kobrina and Dent (2016, 2019).

2.2.1. Testing apparatus

The mice were tested in a wire cage (23 x 39 x 15.5 cm, see Figure 1) placed in a sound-attenuated chamber (53.5 x 54.5 x 57 cm) lined with 4-cm thick Sonex sound attenuating foam (Illbruck Inc., Minneapolis, MN). The chamber was illuminated at all times by a small lamp with an 8-W white light bulb and the behavior of the animals during test sessions was monitored by an overhead web camera (Logitech QuickCam Pro, Model 4000). The test cage contained an electrostatic speaker for tone stimulus presentation (Tucker-Davis Technologies (TDT), Gainesville, FL, Model ES1), a dome tweeter located adjacent to the ES1 speaker for noise presentation (Fostex, Model FT28D), a dipper (Med Associated Model ENV-302M-UP), and two nose poke holes surrounded by infrared sensors (Med Associates Model ENV-254).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the operant conditioning setup used in the behavioral sound detection experiments. Mice were trained to nose-poke in an observation hole in quiet or background noise conditions. Detection of a target sound was indicated by nose-poking in a report hole. Correct detection of the target sounds was reinforced with chocolate Ensure from a dipper. False alarms were punished with a 3-5 s time out period.

The experiments were controlled by Dell Optiplex 580 computers operating TDT modules and software. Stimuli were sent through an RP2 signal processor, a PA5 programmable attenuator, an ED1 electrostatic speaker driver, and finally to the speaker. Inputs to and outputs from the testing cage were controlled via RP2 and RX6 processors. Power supplies were used to drive the dipper (Elenco Precision, Wheeling, IL, Model XP-603) and infrared sensors (Elenco Precision, Model XP-650). Custom Matlab and TDT RPvds software programs were used to control the hardware. White noise was generated using a 1.6 Hz to 39 kHz noise generator (ACO Pacific Inc., Belmont, CA, Model 3025).

2.2.2. Testing stimuli

The stimuli for the behavioral experiments were four USVs (30 kHz harmonic, downsweep, multijump, and upsweep) (Figure 2) and 42 and 56 kHz 100-ms pure tones (0.01-s rise/fall cosine ramps). All six stimuli were presented in two listening conditions: quiet and a continuous white noise background, yielding a total of 12 testing conditions. Only one testing condition was presented per session. A random order of testing conditions was generated for each animal. If the mouse completed testing on all stimuli, a new random order of the same stimuli was generated and they were tested again. Testing continued until the subject was unable to perform the detection task due to hearing loss and/or age-related health decline. Six animals that participated in this study were able to go through 2 to 4 separate random orders, completing 30 to 52 testing conditions each across their entire lifespan. In total, all mice completed between 2 and 52 conditions.

Figure 2.

Spectrograms of the four ultrasonic vocalizations used as stimuli in the behavioral detection experiments.

The USVs were chosen based on their spectral and temporal characteristics and frequency of production (Burke et al., 2018; Grimsley et al., 2011; Portfors, 2007). The ultrasonic vocalizations were recorded from an adult male CBA/CaJ mouse (not a subject in this experiment) responding to female urine in dirty bedding, using a condenser microphone (UltraSoundGate CM16/CMPA, flat frequency response (±6 dB) between 25 and 140 kHz) attached to a laptop computer (HP Pavilion dv5) using an Avisoft recorder (UltraSoundGate 416H) at a 300 kHz sampling rate with a 16-bit format. Stimuli were edited using a band-pass filter (25–90 kHz) in Adobe Audition (v. 5.0) to eliminate noise. The pure tones were generated and edited in Adobe Audition. Sound pressure levels for stimuli and background white noise were calibrated using an ultrasound recording system (Avisoft, Model USG 116-200) and a custom Matlab script, with the microphone (Avisoft Bioacoustics Ultra Sound Gate CM116) placed at the approximate location where the animal’s head would be during testing. Calibrations were conducted weekly.

The USVs had diverse spectrotemporal characteristics. The 30 kHz harmonic USV had a frequency range of 27–75 kHz and was 0.121 s in duration (Figure 2A). The downsweep USV ranged from 47–64 kHz and was 0.070 s in duration (Figure 2B). The multijump USV ranged from 42–61 kHz and was 0.083 s in duration (Figure 2C). The upsweep USV ranged from 38–60 kHz and had a duration of 0.045 s (Figure 2D).

The background listening conditions in the operant experiments were either quiet (30 dB SPL ambient background noise) or a continuous white noise background presented on average at 55 dB SPL. The calibration values for quiet and continuous white noise backgrounds varied by +/− 3 dB SPL between calibration sessions. The spectrum levels of the white noise peaked at an intensity of 66.7 dB SPL at 800 Hz, and had a minimum intensity of 35.4 dB SPL at 315 Hz. At 20 kHz, the intensity of the white noise was 53.2 dB SPL. Spectrum levels could not be calculated above 20 kHz due to the limitations of the sound level meter used to measure 1/3 octave bands and pressure levels used in the calculations. Broadband noise with similar spectrum levels have previously been used in animal models tested on behavioral hearing in noise psychoacoustic tasks (Okanoya and Dooling, 1985; Lauer et al., 2007).

2.2.3. Behavioral training and testing procedures

Mice were trained using a Go/No-go operant conditioning procedure on a detection task. They were trained to poke to the left observation hole twice to initiate the trial, wait for the stimulus, and then poke to the right report hole once when the stimulus was detected. The first stage in the training process was to shape the mice to nose poke to the observation hole and then approach the dipper for the 0.01 ml of chocolate Ensure® reinforcement. The mice were then trained to repeatedly poke to the observation hole until they heard a pure tone, after which they would nose poke to the report hole for the reinforcement. The training stimulus varied in frequency across mice. Next, catch trials were phased into the training and the variable waiting interval between the second nose poke and the stimulus presentation was systematically increased.

Once fully trained to perform the operant response, the mouse began a trial by nose poking through the observation hole, which initiated a variable waiting interval ranging from 1 to 4 s. After the waiting interval, a single test stimulus was presented. This constitutes the “Go” portion of the “Go/No-go” procedure. If the mouse detected the stimulus, it was required to nose poke through the report hole within 2 s of the onset of the target. In this trial type, a “hit” was recorded if the mouse correctly responded within the response window and the animal received the Ensure® reinforcement. A “miss” was recorded if the mouse failed to nose poke through the report nose-poke hole during the waiting interval. When a “miss” occurred, the trial was aborted, and the mouse could initiate the next trial right away. Sessions with total hit rates of at least 80% were included in data analysis. Animals obtained a hit rate of less than 80% approximately 1% of the time, thus very few sessions were excluded for this reason.

Thirty percent of all trials were “No-go” or sham trials. No stimulus was presented during the sham trials. These trials were required to measure the false alarm rate and calculate the animal’s response bias. If the subject nose poked to the report hole during a sham trial, a “false alarm” was recorded and the mouse was punished with a 3 to 5 s timeout interval. However, if the mouse continued to nose poke to the observation hole, a “correct rejection” was recorded and the next trial would begin immediately. In either case, no reinforcement was given. Chance performance was represented by the animal’s false alarm rate. Testing sessions with false alarm rates greater than 20% were excluded from final data analysis, and approximately 3% of all sessions were discarded for this reason. Mice typically completed between 50 and 400 trials per testing session. Once performance stabilized for loud sounds, a range of quieter sound levels was introduced in order to calculate thresholds.

A pure tone of only one frequency or only one USV was tested per session, with stimulus amplitude varying from trial to trial. Within a session, all of the stimulus levels were presented to the subjects in randomized blocks of 10 (7 targets (“Go”) and 3 shams (“No-go”) per block) according to the Method of Constant Stimuli (MOCS). Two out of the seven “Go” targets were attenuated in steps of 5 dB for animals under 800 d.o., or 10 dB for 800 d.o. animals and older, until performance consistently dropped below 50% for the quietest stimulus. Four hundred trials were then collected and thresholds were calculated from the final 200 trials. Once a threshold was calculated for that stimulus, subjects were moved on to the next stimulus type. Data collection continued throughout the subjects’ lifespan and was terminated when mice responded less than 50% of time to the loudest target of any frequency, or upon deterioration of the subject’s health.

A subset of 18 mice (7 M, 11 F) was also used to collect thresholds for one stimulus type continuously for 30-60 days. These mice were trained to detect 42 or 56 kHz pure tones in quiet or in noise background conditions. Once a threshold was calculated for that stimulus, subjects remained on their assigned condition for 30-60 days. One to two hundred trials (hit rate: > 80%, false alarm: < 20%) were collected each day and used to calculate daily performance. These data were used to measure threshold stability as a function of age, sex, stimulus type, and background listening condition.

2.3. ABR experiment

ABRs were recorded to evaluate the status of the auditory nerve and brainstem response to sounds in young and old mice. Procedures were similar to those described by Lauer (2017), McGuire et al. (2015), and Schrode et al. (2018). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with an injection of 100 mg/kg ketamine and 20 mg/kg xylazine (IP), and body temperature at 36°C ±1° was maintained throughout the procedure. For recording, mice were placed inside a small sound-attenuating chamber (IAC) lined with Sonex Acoustic foam, 30 cm from a speaker (FT28D; Fostex, Tokyo, Japan). We placed subcutaneous platinum needle electrodes over the left bulla, at the vertex of the skull, and in the leg muscle. The electrodes were attached to a preamplifier leading to an amplifier (ISO-80; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL).

Stimulus generation, presentation, and response acquisition were controlled using custom Matlab-based software, a TDT RX6, and a PC. We presented clicks (0.1 ms square wave pulse of alternating polarity) and 5-ms tones at frequencies of 6, 8, 12, 16, 24, and 32 kHz (0.5 ms onset/offset) at a rate of 20/s and averaged the response over 300 stimulus repetitions. Each stimulus was presented at descending levels starting at 85-105 dB (depending on frequency) until a threshold was reached. Step sizes were 10 dB at suprathreshold levels, then decreased to 5 dB bracketing the threshold. Threshold was defined as the sound level at which the ABR waveform’s peak-to-peak amplitude was two standard deviations above the average baseline amplitude during the period of the recording when no sound stimulus was present, a common method for identifying threshold (Cediel et al., 2006; Ngan and May, 2001; McGuire et al. 2015; Lauer, 2017; Schrode et al., 2018). It should be noted that thresholds from different animals may have been based on different peaks, and that there may be a systematic difference in the peaks present at different ages. Thus, thresholds at different ages could be based on different peaks. However, this calculation method was used to establish the functional response of the auditory system because previous studies showed that central ABR waves can be present even with a drastically diminished wave 1 (Buran et al., 2010). The age-related trends in our ABR thresholds were consistent with previous literature, regardless of the threshold determination method (Li et al., 1993; Sergeyenko et al., 2013; Sha et al., 2008; Varghese et al., 2005). Stimuli were calibrated using a ¼” free-field microphone (Type 4939; Brüel and Kjær, Nærum, Denmark) and custom Matlab-based software. Testing lasted approximately 40-60 minutes; mice were returned to their home cages following testing and monitored until recovered. ABRs were not recorded in noise because the waveforms were already severely diminished in old mice without the addition of masking sounds. We manually measured amplitudes and latencies of waves 1 through 4 for responses to 70 dB pSPL clicks offline using a custom JAVA-based program to mark positive and negative peaks. Wave 5 was not reliably detected in our recordings, consistent with reports for mice from others (Zheng et al., 1999), so we did not measure or analyze it further.

2.4. Cochlear anatomy experiment

We performed cochlear histology to evaluate the status of hair cells and afferent and efferent synapses. Mice were deeply anesthetized with a 0.3-0.5 mg/g dose of sodium pentobarbital (i.p.), transcardially perfused with 60 ml of a 4% paraformaldehyde fixative solution, and decapitated. We collected the cochleas, re-perfused them with 4% paraformaldehyde through the round and oval windows, and let them post-fix for 1 hour. Cochleas were then moved to 1% EDTA for decalcification for 1-4 weeks until they were dissected.

After decalcification, we dissected the organ of Corti into 5-6 flat turns following methods described by Eaton Peabody Laboratories (https://www.masseyeandear.org/research/otolaryngology/investigators/laboratories/eaton-peabody-laboratories/epl-histology-resources/cochlear-dissection-summary). Cochlear pieces were placed in a blocking buffer of 5% normal goat serum, 10% bovine serum albumen, and 0.5% triton X-100 (Electron Microscopy Services) for one hour and then incubated overnight in primary antibodies. For afferent synapse labeling, primary antibodies consisted of mouse monoclonal anti-CTBP2 (1:200, BD Biosciences, Cat# 612044, RRID:AB_399431), rabbit polyclonal anti-myosin 6 (1:500, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# M5187, RRID:AB_260563), and chicken polyclonal anti-neurofilament (1:1000, Millipore, Cat# AB5539, RRID:AB_11212161) in half-concentration blocking buffer. For efferent synapse labeling, primary antibodies consisted of mouse anti-SV2 (1:500, DSHB Cat# SV2, RRID:AB_2315387) and rabbit polyclonal anti-myosin 6 (1:500, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# M5187, RRID:AB_260563). The next day, cochlear pieces were incubated in secondary antibodies in half-concentration blocking buffer for two hours at room temperature, and then were mounted in Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) and cover-slipped. Secondary antibodies were goat anti-mouse AF488 (1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# A-10667, RRID:AB_2534057), goat anti-rabbit AF568 (1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# A-11036, RRID:AB_10563566), and (for cochleas labeled with anti_CTBP2) goat anti-chicken AF647 (1:1000, Invitrogen, Cat# A21449, RRID:AB_1500594).

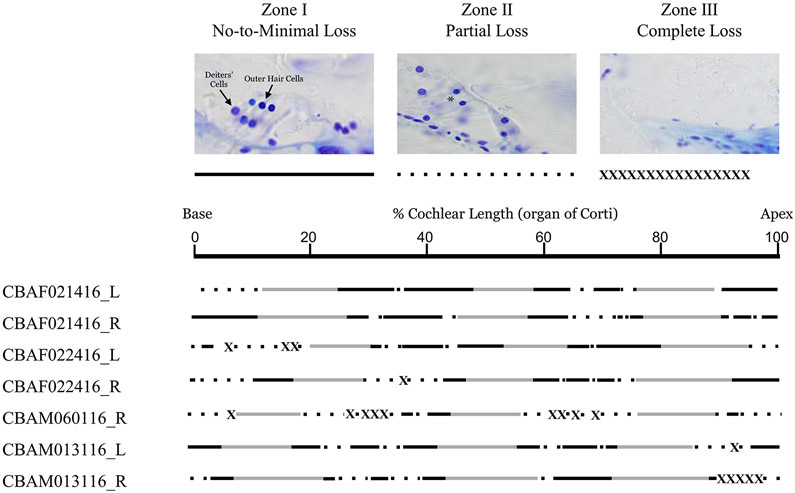

Cochleas from a subset of behaviorally trained mice were evaluated for degeneration at the conclusion of behavioral testing. Hair cell and neural loss was expected to be substantial in mice approaching 3 years of age, thus we did not perform immunolabeling after preliminary experiments failed to reveal enough surviving organ of Corti for quantitative analysis of synapses. Instead, inner ears were prepared for light microscopy to examine degeneration patterns. Cochleas were embedded in Araldite and sectioned parallel to the modiolus following the methods used by Schrode et al. (2018). For analyses of organ of Corti, spiral ganglion neurons, and stria vascularis in cochlear cross sections, we dehydrated and embedded decalcified cochleas in araldite. The cochleas were sectioned into 30 μm serial sections through the modiolus with a rotary microtome. The sections were mounted on subbed slides, stained with toluidine blue, and cover-slipped. 2.5x images were taken of each section using a digital camera mounted on a microscope with image acquisition software (Jenoptik ProgResCF). We made observations of outer hair cell (OHC) loss under 20x and 40x magnification. OHC loss was defined by a 1:1 loss of OHCs and Deiter’s cells, and categorized as No-to-Minimal Loss, Partial Loss, or Complete Loss. We also made observations about spiral ganglion survival by looking at the population of spiral ganglion neurons in mid-modiolar sections under 20x and 40x magnification. Analysis of spiral ganglion neurons was limited to qualitative assessments because cell survival was too sparse to perform meaningful counts.

We imported the images into the Reconstruct software and used them to create a 3-D image of the organ of Corti (Fiala, 2005). To do this, the sections were aligned by marking 3 or more fiducial points on each section. A marker was placed on each observable portion of the organ of Corti in each section and degeneration observations were marked. The length of each turn of the cochlea and the relative position of OHC loss was measured using the Z-trace tool on Reconstruct. We then imported the image into the Image-J software, and used the Bezier curve tool to fill in the gaps of the coil, which are a byproduct of the orientation in which the cochlea was sectioned. The length of each Bezier curve was measured using the segmented line tool. Each segment of degeneration was mapped along a line by percentage of cochlear length from base to apex (Stamataki et al., 2006). Frequency was not used as a reference for the cross-sections of cochleas from mice approaching 3 years of age, because frequency maps shift in degenerated cochleae (Müller et al., 2005).

We assessed stria vascularis health by creating a 3-D image of the stria vascularis and measuring the areas of melanin and lipofuscin. We captured 20x images of the sections in the mid-modiolar portion of the cochlea and imported them into Image-J. The stria vascularis was outlined in each section (see Figure 9). We then outlined the regions with pigment, including melanin and lipofuscin, and calculated the summed cross-sectional area using ImageJ (Sun et al. 2014). We assessed stria vascularis thickness by drawing a line horizontally across the stria vascularis at the apical, middle, and basal turns of the cochlea and making a calibrated measurement of the line.

Figure 9.

Cochlear histology in old (900-975 d.o.) female (F, 1-4) and male (M, 5-7) mice for left (L) and right (R) cochlea. The lines represent the percentage of degeneration along the length of the organ of Corti from base to apex. The solid black lines represent areas with no-to-minimal hair cell loss, the areas with dashed lines represent areas with partial hair cell loss, and the crossed out portions of the line represent areas with complete hair cell loss. The blank areas represent areas where the hair cell loss could not be determined due to mechanical damage from the plastic embedding process or the angle at which the cochlea was sectioned.

2.5. Data analysis

2.5.1. Behavioral experiment

Signal detection analysis was performed to factor out the animals’ motivational biases since bias is independent of sensitivity (Steckler, 2001). Mean hit and false alarm rates were used to calculate thresholds using signal detection theory with a threshold criterion of d’= 1.5. We chose this conservative d′ value in order to compare these results with other findings for this and other mouse strains (e.g., CBA/CaJ mice, Kobrina and Dent, 2016, 2019; NMRI mice, Klink et al., 2006) and due to its correspondence to a low false alarm rate.

This longitudinal data set contained an unequal number of observations from every mouse due to differences in lifespan and productivity. Every independent variable category (sex, stimulus type, and background condition) contained a different number of data points that were obtained at varying intervals between observations from mice. Some mice contributed multiple observations per stimulus type and background condition, while others were only able to complete one set of stimuli during testing. We chose to analyze this data set using mixed-effects linear modeling, a statistical analysis method used for studying ARHL in humans and mice (Kobrina and Dent, 2019; Laird and Ware, 1982; Lin et al., 2011; Pearson et al., 1995). This statistical methodology is widely used for longitudinal data sets that contain fixed and random effects, missing data points, unbalanced experimental design, repeated measures, and covariance in the data (reviewed by Pearson et al., 1995).

We first used linear mixed-effects model to explore whether linear (age), quadratic (age2), cubic (age3), and quartic (age4) polynomials could explain the variability in hearing in mice (Thresholds (dB SPL) = lmer (threshold (dB) ~ poly (age, 4) + (1∣ Id), LMM, lmer in the lme4 R package) (Bates et al., 2015; R Core Team, 2017). The goodness of fit for different functions was assessed using a correlation coefficient comparison tool in R (cocor.dep.groups.() in the cocor R package) (Diedenhofen and Musch, 2015). Linear, quadratic, and cubic data fittings could be used to explain changes in thresholds due to hearing loss (p < 0.001). Second (threshold (dB) = y0 + a*x + bx2) and third order functions (threshold (dB) = y0 + a*x + bx3) explained the greatest amount of variability in the threshold data due to aging, although there were no significant differences between quadratic and cubic polynomials (p > 0.05). Previous research in humans (Lin et al., 2011; Pearson et al., 1995) and mice (Kobrina and Dent, 2019; Ohlemiller et al., 2010) showed that the decrease in hearing sensitivity occurs in quadratic and cubic patterns, thus age2 and age3 were included as predictor variables in the main analyses.

We used a linear mixed-effects model to examine whether age can predict hearing loss in male and female mice across stimuli and listening conditions (LMM, lmer in the lme4 R package). The model in this analysis was significantly different from the intercept only model, which contains no predictor variables (p < 0.001), and was chosen due to the best quality estimator compared to other possible models as assessed via Akaike Information Criterion (AIC = 3636.8). In this model, we examined if thresholds (dB SPL) were affected by fixed factors of age, age2, and age3 (continuous), sex (male and female), stimulus (USVs, and 42 and 56 kHz tones), background listening condition (quiet and white noise), and by interactions between sex and condition, stimulus and condition, stimulus and age1,2,3, as well as three-way interactions between stimulus, age1,2,3, and condition, and between sex, age1,2,3, and condition. To control for dependencies within our data from sampling each mouse repeatedly, we included a random intercept for mouse identity across age. Planned contrasts were performed using Tukey’s method to establish hearing loss onset in white noise and quiet conditions by comparing hearing between 300 and 900 d.o. using 50 day intervals, with p values being automatically adjusted for family-based comparisons. Post-hoc comparisons using Tukey’s method were performed to assess significance in the relationship between sex, condition, and stimulus type (emmeans R package).

In order to examine the stability of detection thresholds in CBA/CaJ mice, thresholds for 42 and 56 kHz were collected daily over the course of 30–60 days in quiet and in white noise in a subset of subjects (n = 18). Average sensitivity, average age, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation (CV) were computed for every subject in this subsample (Table 3). CV is the proportion of mean thresholds to standard deviations that can be used to examine the variability in detection performance within and between mice and conditions. Linear regression analysis was then used to examine whether age predicts variability (CV) in mice across stimuli and listening conditions. A separate regression analysis was performed in order to assess the relationship between hearing sensitivity and variability in performance (CV).

Table 3.

Mean age, mean thresholds, and the coefficient of variation (CV) for male and female mice across pure tones and background conditions1.

| Sex | Frequency (kHz) |

Background Condition |

Age Range (d.o.) |

Mean Age (d.o.) |

Mean Threshold (dB) |

CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 56 | Quiet | 436 - 472 | 454.0 | 43.92 | 0.08 |

| Female | 56 | Quiet | 489 - 534 | 511.5 | 33.37 | 0.10 |

| Female | 56 | Quiet | 936 - 996 | 966.0 | 86.12 | 0.03 |

| Female | 42 | Noise | 389 - 435 | 412.0 | 32.13 | 0.17 |

| Female | 56 | Noise | 420 - 450 | 435.0 | 35.98 | 0.08 |

| Female | 56 | Noise | 420 - 455 | 437.5 | 45.64 | 0.09 |

| Female | 42 | Noise | 436 - 455 | 445.5 | 32.12 | 0.08 |

| Female | 42 | Noise | 451 - 493 | 471.5 | 21.89 | 0.17 |

| Female | 56 | Noise | 439 - 483 | 461.0 | 38.76 | 0.08 |

| Female | 56 | Noise | 645 - 686 | 665.5 | 46.79 | 0.11 |

| Female | 56 | Noise | 889 - 928 | 908.5 | 48.88 | 0.07 |

| Male | 56 | Quiet | 460 - 503 | 481.5 | 41.76 | 0.15 |

| Male | 56 | Quiet | 521 - 553 | 537.0 | 49.28 | 0.11 |

| Male | 42 | Quiet | 613 - 656 | 634.5 | 13.38 | 0.19 |

| Male | 56 | Quiet | 967 - 989 | 978.0 | 92.75 | 0.05 |

| Male | 42 | Noise | 393 - 433 | 413.0 | 37.69 | 0.08 |

| Male | 56 | Noise | 429 - 452 | 440.5 | 39.5 | 0.10 |

| Male | 42 | Noise | 740 - 766 | 753.0 | 45.63 | 0.04 |

CV = coefficient of variation.

2.5.2. ABR experiment

A separate set of statistical models was used to assess whether hearing loss in mice could predict changes in ABR thresholds and changes in ABR wave morphology across stimuli. The ABR data set contains two longitudinal subsamples for young and old mice, and the data were analyzed assuming changes across the lifespan were monotonic. Similar to the behavioral analysis, we used a linear mixed-effects model to explore and compare various models of data fitting, and to test whether our model is consistent with previously established hearing loss trends in CBA/CaJ mice. Similar to previous findings in this mouse strain, linear and quadratic polynomials could explain changes in ABR thresholds due to hearing loss (p < 0.01), although there were no significant differences between these functions (p > 0.05) (Henry, 2004; Li and Borg, 1991; Zheng et al. 1999). Age and age2 were chosen as main predictor variables for these analyses. Then, we constructed a linear mixed-effects model to examine whether age (x) and age2 (x2) predict change in ABRs in male and female mice across stimuli (AIC = 3568.6) (LMM, lmer in the lme4 R package) (Bates et al., 2015; R Core Team, 2017). In this model, we examined if thresholds (dB) were affected by fixed factors of age and age2 (continuous), sex (male and female), stimulus (click, 6, 8, 12, 16, 24, and 32 kHz tones), and by interactions between sex, age, and stimulus. To control for dependencies within our data from sampling each mouse repeatedly, we included a random intercept for mouse identity across age. Planned contrasts were performed using Tukey’s method to establish hearing loss onset in white noise and quiet conditions by comparing hearing between 300 and 900 d.o. using 50 day intervals, with p values being automatically adjusted for family-based comparisons. Post-hoc comparisons using Tukey’s method were performed to assess the relationship between age, age2, sex, condition, and stimulus type (emmeans R package), with p values being adjusted for the number of models to reduce type 1 errors (p = 0.0125).

Separate linear mixed-effects models were constructed to examine whether age (x) and age2 (x2) predict changes in amplitude, latency, and inter-peak intervals (IPIs) in male and female mice across stimuli (LMM, lmer in the lme4 R package) (Bates et al., 2015; R Core Team, 2017). In these models, we examined if amplitude, latency, and IPIs (dependent variables, DVs) were affected by fixed factors of age and age2 (continuous), sex (male and female), stimulus (clicks and 6, 8, 12, 16, 24, and 32 kHz tones), peak, and by interactions between sex, age, and stimulus (general formula: DVs = lmer (DVs ~ sex * poly (age, 2) * stimulus + peak + (1∣ Id)). We controlled for dependencies in our data by including a random intercept for mouse identity across age. Planned contrasts using the same methodology as described in this section were performed on amplitude, latency, and IPIs. Tukey’s post-hoc analyses were performed to assess the relationship between age, age2, sex, condition, and stimulus type (emmeans R package), with p values being adjusted for the number of models to reduce type 1 errors (p = 0.0125).

2.5.3. Cochlear anatomy experiment

We quantified terminals and hair cells at 9 frequency locations along the cochlea, at half-octave intervals between 4 and 64 kHz. Locations were identified using low magnification ~5x photographs and the Image-J plugin Measure_line, also developed by the Eaton Peabody Laboratories. We collected z-stacks at 63x magnification using a confocal microscope (LSM 700 Axio Imager 2; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Care was taken to ensure that terminals at all depths were captured. In FIJI software, we counted the number of hair cells and associated afferent ribbons and efferent terminals within a 100 μm window corresponding to each frequency specific point. Cells and their ribbons were only included if the entire cell was visible in the image frame. For efferent terminals, we counted the terminals and also calculated the area labeled in the inner hair cell region and in the outer hair cell region using custom scripts and automated thresholding in Image-J. While several thresholding algorithms accurately identify labeling in tissue from young animals, background labeling tended to be higher in old animals. We found that the intermodes thresholding algorithm identified labeling in a manner that was somewhat conservative for young animals but effectively excluded background labeling in old animals. Hair cell and presynaptic ribbon survival data from young animals are replotted from Schrode et al. (2018).

To determine the effect of age on cochlear anatomy, we used linear mixed models (lmer in the lme4 R package and the afex package) (R Core Team, 2017) to assess the effects of age, frequency, and sex on CTBP2 counts per IHC, SV2 counts per OHC, and area labelled per IHC and OHC at each frequency location. The models included the interaction between age and frequency, as well as the main effects of age, frequency, and sex. Frequency was treated as a categorical variable because the relationship between the anatomical variables and frequency did not clearly follow a linear or quadratic relationship. We controlled for repeated measures dependencies in our data by including a random intercept for mouse identity. We present the results for the analysis of variance (ANOVA) based on each model, as well as posthoc tests controlling for multiple comparisons using the mvt adjustment (emmeans), and we include partial η2 and Cohen’s d as standardized measures of effect size. A separate linear mixed-effects model (lmer in the lme4 R package) (R Core Team, 2017) was used to assess the effects of age, ear (left, right), location (apex, mid, base), and the interaction between age and location on thickness of stria vascularis (μm) in mice. In addition, we also used linear mixed-effects model to examine the effects of age on percent of pigmented cross-sectional area of stria vascularis. We controlled for repeated measures dependencies in our data by including a random intercept for mouse identity. Tukey’s post-hoc analyses were performed to assess significance (emmeans R).

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral hearing assessments

In general, hearing declined differently across stimuli and background conditions (Figures 3-4). Mice had worse hearing sensitivity for USVs and pure tones in white noise than in the quiet condition (p < 0.001), with earlier onset of hearing loss for USVs and 56 kHz tones in white noise than in the quiet background. Presbycusis progressed differently in mice for USVs and 42 kHz tones than for 56 kHz pure tones (p < 0.001). Hearing loss onset for USVs and 42 kHz tones occurred in the last third of the CBA/CaJ mouse’s lifespan across listening backgrounds. However, hearing loss for 56 kHz tones occurred in the first and last third of mouse’s lifespan in quiet, and progressed linearly in the white noise background.

Figure 3.

Age-related deterioration of behavioral detection of sounds in quiet. Performance becomes especially poor after 650 d.o. for USVs (A), and after 700 d.o. for 42 kHz tones (B). Age-related hearing loss occurs progressively up to 450 d.o. and after 650 d.o. for 56 kHz pure tones, with a stable plateau between those ages (C). Each plot depicts thresholds from multiple mice across their lifespans (males = filled blue symbols, females = open symbols). Lines represent the best cubic data fits. The amount of variability in the data explained by aging is expressed in the form of r2 for males and females separately. Dashed lines indicate the onset of hearing loss for USVs and 42 kHz tones, and plateau boundaries for 56 kHz tones.

Figure 4.

Age-related deterioration of behavioral detection of sounds in white noise. Performance becomes especially poor after about 600 d.o. for USVs (A), and after 700 d.o. for 42 kHz tones (B). Age-related hearing loss progressed continuously for 56 kHz tones up to 750 d.o., with a ceiling boundary late in life (C). Each plot depicts thresholds from multiple mice across their lifespans (males = filled blue symbols, females = open symbols). Lines represent the best cubic data fits. The amount of variability in the data explained by aging is expressed in the form of r2 for males and females separately. Dashed lines indicate the onset of hearing loss for UVSs (A), and 42 kHz tones (B), and a ceiling boundary for 56 kHz tones (C).

Mice were able to detect pure tones and USVs across their lifespan for the two background conditions (Table 1). A cubic regression analysis revealed that age served as a significant predictor of hearing loss for USVs and pure tones in male and female mice in the quiet condition (p < 0.001) (Figure 3). Age served as a predictor of hearing loss in male mice, accounting for 66% of the variability in USV thresholds, and for 46% of the variability in 42 kHz thresholds. Lastly, aging accounted for 77% of the variability in the data for 56 kHz tones in males. In females, aging accounted for 62% of the variability in USV thresholds, 47% of variability in thresholds for 42 kHz tones, and for 84% of the variability for 56 kHz tones. Age also served as a significant predictor of hearing loss in the white noise background condition (p < 0.001) (Figure 4). In males, aging accounted for 37% of the variability in USV thresholds, 69% of the variability in 42 kHz thresholds, and for 66% of the variability for 56 kHz pure tone thresholds. In females, aging accounted for 66% of the variability in USV thresholds, 77% of the variability in thresholds for 42 kHz tones, and for 48% of the variability for 56 kHz tones.

Table 1.

Mixed-effects model analysis and significance testing comparing hearing loss in male (N = 22, Nobservations = 246) and female (N = 25, Nobservations = 262) mice across the lifespan for two pure tones and USVs in silence and in white noise listening conditions.1

| Fixed Effects | B | SE | t-value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (Id) | 30.59 | 1.80 | 17.02 | <0.000 |

| Age | 157.10 | 27.44 | 5.73 | <0.000 |

| Background Condition | 10.55 | 1.82 | 5.81 | <0.000 |

| 56 kHz Tone | 14.56 | 1.59 | 9.14 | <0.000 |

| Sex * Age2 | 46.72 | 23.40 | 2.00 | 0.046 |

| Sex * Background Condition | −3.40 | 1.67 | −2.04 | 0.042 |

| 56 kHz Tone * Age | 138.35 | 34.06 | 4.06 | <0.000 |

| USVs * Age | 89.75 | 26.79 | 3.35 | 0.001 |

| USVs * Age2 | 64.68 | 25.44 | 2.54 | 0.011 |

| 56 kHz Tone * Background Condition | −7.81 | 2.38 | −3.29 | 0.001 |

| Random Effects | σ2 | |||

| Mouse Id | 6.53 | |||

| Residual | 7.63 |

For simplicity, only significant values are reported. The LMM formula in R was lmer (threshold ~ sex * poly (age, 2) * background condition + poly (age, 2) * background condition * stimulus + (1∣ Id)). B = model estimate, SE = standard error, σ2 = standard deviation. Fixed effects for background condition are compared to quiet. Fixed effects for the 56 kHz stimulus are compared to 42 kHz tone. The fixed effects for the sex * age2 interaction are compared to sex (female) * age interaction; fixed effects for the sex * background condition interaction are compared to sex (female) * background condition (quiet). Fixed effects for the stimulus * age interaction as well as stimulus * age2 interaction are compared to 42 kHz tone * age and 42 kHz tone * age2. Lastly, fixed effects for the stimulus * background condition interaction are compared to 42 kHz tone * background condition (quiet).

The mixed-effects model (Thresholds (dB SPL) = lmer (threshold (dB) ~ sex * poly (age, 3) * background condition + poly (age, 3) * background condition * stimulus + (1∣ Id)) revealed that age, age2, background condition, and stimulus type, but not sex, were significant predictors of rates of hearing loss in mice (Table 2). In addition, the model revealed significant sex by age3, sex by background condition, stimulus by age, stimulus by age3, and stimulus by background condition by age3 interactions.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for male and female mice in the behavioral study1.

| Males | Females | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background Condition |

Stim. | Age Range (days) |

Thresh. Range (dB) |

N | N (obs.) |

Age Range (days) |

Thresh. Range (dB) |

N | N (obs.) |

| USVs | 233 – 950 | 7 – 76 | 14 | 66 | 195 – 956 | 8 – 70 | 15 | 73 | |

| Quiet | 42 kHz | 171 – 969 | 12 – 66 | 10 | 37 | 169 – 944 | 13 – 65 | 8 | 32 |

| 56 kHz | 310 – 989 | 27 – 97 | 11 | 31 | 168 – 996 | 8 – 94 | 11 | 35 | |

| USVs | 300 – 964 | 15 – 70 | 6 | 57 | 186 – 953 | 12 – 64 | 7 | 58 | |

| White Noise | 42 kHz | 349 – 948 | 33 – 75 | 6 | 24 | 258 – 950 | 20 – 66 | 10 | 28 |

| 56 kHz | 310 – 989 | 27 – 97 | 7 | 18 | 231 – 928 | 21 – 84 | 10 | 31 | |

N = number of subjects, N (obs.) = number of observations.

Overall, male (p = 0.032) and female mice (p < 0.001) had poorer hearing sensitivity for USVs and pure tones in white noise than in the quiet background (Figures 3-4). Thresholds for USVs and 42 kHz tones were significantly lower in the quiet condition than in the white noise background (p < 0.001), while 56 kHz tones were detected similarly across listening environments (p = 0.351). In quiet, mice experienced hearing loss onset by 650 d.o. for USVs (p < 0.001) and by 700 d.o. for 42 kHz tones (p = 0.027) (Figure 3A-B). Interestingly, in quiet, mice experienced an increase in hearing thresholds for 56 kHz tones up to 450 d.o. (p = 0.040), plateauing between 450 and 650 d.o., with rapid progressive hearing loss after that point (p < 0.001) (Figure 3C). In the white noise background, mice experienced a hearing loss onset by 600 d.o. for USVs (p = 0.026) and by 700 d.o. for 42 kHz tones (p = 0.007) (Figure 4A-B). Hearing sensitivity for the 56 kHz tones decreased progressively in mice in the white noise condition (p < 0.032), reaching its maximum plateau by 750 d.o. (p > 0.05) (Figure 3C). Lastly, the sex by age3 interaction revealed that female mice lost hearing across quiet and white noise background conditions in a more linear pattern with hearing-loss onset as early as 300 d.o. (p = 0.026), whereas male mice lost their hearing abilities in a second and third order polynomial patterns across stimuli and conditions, with an overall change in hearing abilities emerging after 650 d.o. (p < 0.001).

A previous study tracking early-onset progressive hereditary hearing loss in C57BL6 mice identified a period of instability in behavioral tone-in-noise detection thresholds prior to the onset of permanent threshold shifts (Prosen et al., 2003). To assess behavioral stability in CBA/CaJ mice, mean thresholds and CV were calculated for male and female mice for 42 and 56 kHz tones across test days and listening conditions (Table 3). Differences in day to day thresholds varied from 0.1 to 10 dB across conditions, subjects, and ages. In general, detection performance became more stable with age (Figure 5). Regression analyses performed on average age and CVs revealed that age was a predictor for the decrease in variability in hearing in mice (r2 = 0.231, p = 0.044). The regression analysis on average hearing sensitivity and variability in performance (CV) revealed an inverse relationship between hearing sensitivity and CVs (r2 = 0.491, p = 0.001), with higher thresholds being associated with lower CVs. These results indicate that threshold stability emerges as a function of a ceiling effect in detection performance.

Figure 5.

Threshold stability across multiple days of testing as a function of age for A) four mice 425-550 d.o. or B) three mice 875-1000 d.o.. Each line depicts thresholds for one subject in quiet (open symbols) or in white noise (filled symbols).

3.2. ABR thresholds and waveform morphology

ABR waveform morphology (Figures 6A-B) and sensitivity (Figures 6C-F) were affected by aging in CBA/CaJ mice. ABR thresholds increased with age of the subject as expected based on previous studies (e.g., Henry, 2004) (Figure 6C-F). Hearing loss onset varied by sex. Male mice had lower ABR thresholds for 16 and 32 kHz tones early in life, while females had better ABR sensitivity for 32 kHz tones at older ages. ABR waveforms showed a number of age-related changes in amplitude, latency, and inter-peak intervals (Figure 6G-Q).

Figure 6.

Auditory brainstem responses in young and old mice show substantial deficits in function by 600 d.o.. Average waveforms in response to 90 dB (A) and 50 dB (B) clicks in young (60-90 d.o.; black) and old (600-800 d.o.; red) mice, respectively. Standard error is depicted in gray and pink shading for young and old mice, respectively. Legend in A applies to panel B. Thresholds in response to clicks (C), and 8 kHz, 16 kHz, and 32 kHz tones (D-F) in female (red) and male (blue) mice. Amplitudes for peak 1 (p1), peak 2 (p2), peak 3 (p3), and peak 4 (p4) (G-J) and corresponding latencies for p1, p2, p3, and p4 of responses to 70 dB pSPL clicks plotted as a function of age (K-N). Inter-peak intervals for responses to 70 dB pSPL clicks are plotted as a function of age (O-Q). Legend in panel C applies to panels D-Q. In panels C-Q, data points for 60-90 d.o. mice depict means, error bars depict standard errors. Note that error bars in panels K-Q are obscured by the markers.

The mixed effect model (Threshold (dB SPL) = lmer (threshold (dB) ~ sex * poly (age, 2) *stimulus + (1∣ Id)) revealed that age, age2, and stimulus were significant predictors of increases in ABR thresholds in mice (Table 4). In addition, the model revealed significant age by stimulus, age2 by stimulus, stimulus by sex, and age by stimulus by sex interactions. It is important to note that posthoc analyses in this section were performed on predicted values for 300-600 d.o. mice based on model parameters and calculations.

Table 4.

Mixed-effects model analysis and significance testing comparing changes in ABRs due to aging in male (N = 35, Nobservations = 245) and female (N = 40, Nobservations = 255) mice across the lifespan for clicks and pure tones.1

| Fixed Effects | B | SE | t-value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (Id) | 33.57 | 1.62 | 20.79 | <0.000 |

| Age | 237.57 | 36.35 | 6.52 | <0.000 |

| Age2 | 77.12 | 36.45 | 2.12 | 0.036 |

| 6 kHz Tone | 24.27 | 1.75 | 13.85 | <0.000 |

| 8 kHz Tone | 12.47 | 1.49 | 8.39 | <0.000 |

| 16 kHz Tone | 5.13 | 1.49 | 3.45 | 0.001 |

| 24 kHz Tone | 13.32 | 1.55 | 8.60 | <0.000 |

| 32 kHz Tone | 34.44 | 1.53 | 22.47 | <0.000 |

| Age * 6 kHz Tone | 182.92 | 39.04 | 4.69 | <0.000 |

| Age * 8 kHz Tone | 102.12 | 33.45 | 3.05 | 0.002 |

| Age2 * 8 kHz Tone | −103.31 | 33.54 | −3.08 | 0.002 |

| Age * 12 kHz Tone | 106.64 | 34.97 | 3.05 | 0.002 |

| Age * 16 kHz Tone | 122.72 | 33.45 | 3.67 | 0.001 |

| Age * 24 kHz Tone | 145.57 | 34.50 | 4.22 | <0.000 |

| Age2 * 32 kHz Tone | −136.05 | 37.07 | −3.67 | 0.001 |

| Sex * 16 kHz Tone | −4.40 | 2.17 | −2.02 | 0.044 |

| Age * Sex * 16 kHz Tone | −160.00 | 49.25 | 3.25 | 0.001 |

| Age2 * Sex * 16 kHz Tone | 117.46 | 49.50 | 2.37 | 0.018 |

| Age2 * Sex * 24 kHz Tone | 127.90 | 49.50 | 2.58 | 0.010 |

| Age2 * Sex * 32 kHz Tone | 150.52 | 51.98 | 2.90 | 0.004 |

| Random Effects | σ2 | |||

| Mouse Id | 7.74 | |||

| Residual | 6.63 |

For simplicity, only significant findings are reported. The LMM formula in R was lmer (threshold ~ sex * poly (age, 2) *frequency + (1∣ Id)). B = model estimate, SE = standard error, σ2 = standard deviation. Fixed effects for pure tones are compared to clicks. Fixed effects for the age * pure tones and age2 * pure tones interactions are compared to age * click and age2 * click interactions. Fixed effects for the sex * pure tone interaction are compared to the sex (female) * click. Lastly, fixed effects for the age * sex * pure tone and age2 * sex * pure tone interactions are compared to the age * sex (female) * click and to age2 * sex (female) * click.

A Tukey’s posthoc analysis revealed that ABR thresholds increased for all stimuli across the lifespan. In general, ABR thresholds for 6, 8, and 32 kHz tones were significantly higher than thresholds for all other stimuli (p < 0.001). Thresholds for clicks, 12, 16, and 24 kHz tones were not significantly different from each other (p > 0.0125). The age by stimulus interaction revealed that changes in ABR responses due to hearing loss progressed linearly for clicks, 12, 16, and 24 kHz (p < 0.001), with hearing loss onset between 300 and 350 d.o.. The responses to clicks and 12 kHz tones reached maximum plateaus by 800 d.o. and did not increase after that point (p > 0.0125). The ABR thresholds in response to 6, 8, and 32 kHz tones increased progressively as well, plateauing by 600 d.o. for 6 kHz tones, and 500 d.o. for 8 and 32 kHz tones (p > 0.0125). Lastly, the post-hoc analysis of sex by age by stimulus interactions revealed that female and male mice had different ABR thresholds in response to 16 and 32 kHz tones. Female mice had significantly higher ABR thresholds for 16 kHz tones at 600-650 d.o. (p < 0.009), and significantly higher ABR thresholds for 32 kHz tones at 300 d.o. (p = 0.012). Interestingly, female mice had significantly lower ABR thresholds than males after 800 d.o., but only for 32 kHz tones (p = 0.007).

ABR waveform morphology showed a number of age-related changes (Figure 6G-Q). Overall, the largest peak-to-peak amplitudes occurred for p1-n1 and n1-p2 in young and old mice. Amplitudes continuously decreased with age across stimuli (p < 0.001). Amplitudes for 6, 8, and 32 kHz tones reached their minimum plateaus by 450 d.o. and did not change after that point (p < 0.011). Amplitudes for 16 and 24 kHz reached their minimum plateaus by 500 d.o. (p < 0.004), while amplitudes for 12 kHz plateaued by 550 d.o.. Lastly, mice had progressive decreases in amplitude for click stimuli up to 700 d.o. (p < 0.003). In general, latencies increased with age, with male mice exhibiting longer latencies than females across stimuli after 700 days of age (p < 0.006). Since we did not correct for sensation level, the increase in latencies could be related to threshold changes.

IPIs increased with frequency of the stimulus and age for both sexes (p < 0.001). Male mice had lower IPIs than females for 12 kHz tones between 500 and 700 d.o. (p < 0.010), for 16 kHz tones up to 500 d.o. (p < 0.010), and for 24 kHz up to 400 d.o. (p < 0.012). Female mice had lower IPIs after 750 d.o., but only for 24 kHz tones. IPIs between peaks 1 (auditory nerve) and 2 (globular bushy cells in ventral cochlear nucleus) increased with age, reaching a maximum plateau by 400 d.o. (p < 0.001). IPIs between brainstem-generated waves (p2 and later) were longer and more variable in older mice (p < 0.001), indicating abnormal brainstem transmission time.

3.3. Cochlear degeneration patterns

Immunolabeling revealed some loss of inner hair cells in aging animals (Figure 7A). For most frequency regions, the loss was small, with about 80% of cells surviving. Hair cell loss at the extreme base was substantial, with about 50% loss of inner hair cells. There were no sex differences in inner hair cell loss patterns (p>0.05), though the sample sizes may have been too small to detect subtle differences. Outer hair cell loss in aging animals was more drastic than inner hair cell loss (Figure 7A). Outer hair cell loss was observed primarily for frequency regions below 16 kHz and in the extreme base. Outer hair cells were mostly intact in the mid- to high frequency regions. It should be noted that these results are reported using the cochlear place-frequency map that was established for young, healthy ears. It is unclear how age affects the cochlear place-frequency map in aging specimens, although shifts in frequency representation have been reported in noise-exposed mouse cochleas.

Figure 7.

Percent surviving outer hair cells (OHC) and inner hair cells (IHC) in 600-800 d.o. mice (9 female; 6 male) relative to 60-90 d.o. mice (7 female; 5 male) (A). Representative maximum-intensity projections of confocal z-stacks of young (120 d.o.) and old (751 d.o.) female mouse organ of Corti labeled with antibodies against myosin 6 (hair cells), CTBP2 (presynaptic ribbons), and neurofilament (nerve fibers) (B). Number of surviving presynaptic ribbons per IHC in young (1 female; 2 male) and old (3 female; 4 male) mice (C). Data points in (C) depict means, error bars depict standard errors. Stars indicate significant differences.

Loss of approximately 30-50% of presynaptic ribbon numbers along the length of the cochlea in aging animals was observed (Figure 7B-C). However, there was a significant interaction between age and frequency (F = 2.2, p = 0.043, partial η2 = 0.23). Posthoc tests revealed significant effects of age at 11 kHz (t = 3.3, p = 0.018, d = 2.99), 16 kHz (t = 3.9, p = 0.004, d = 3.45) and 22 kHz (t = 3.7, p = 0.007, d = 3.27).

Individual lateral efferent synapses could not be resolved, but the total labeled area per inner hair cell was only substantially reduced in the 8 kHz region (Figure 8A-B). The mixed model and posthoc tests confirmed this observation with a significant effect of the interaction of age and frequency (F = 5.8, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.38) and of the effect of age at 8 kHz in the posthoc tests (t = 3.9, p = 0.015, d = 2.90). In contrast, the total labeled area for lateral efferent synapses was increased in the extreme base, at 64 kHz (t = 3.0, p = 0.030, d = 2.77). For surviving outer hair cells, there were fewer individual medial efferent synapses per hair cell, particularly for regions below 16 kHz and in the extreme base (Figure 8C). There was a significant effect of the age by frequency interaction in the mixed model (F = 3.1, p = 0.004, partial η2 = 0.20), and posthoc tests revealed a significant effect of age at all frequencies below 16 kHz and at 64 kHz (all t ≥ 4.1, all p = 0.008, d ≥ 2.41). Despite loss of the number of individual synapses, the total labeled area per surviving outer hair cell was unaffected in all but the most apical regions, where area increased (Figure 8D). There was a significant effect of age by frequency interaction (F = 3.9, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.28), and the posthoc tests indicated that the effect of age only had a significant effect at 4 kHz (t = 3.1, p = 0.023, d = 2.69) and 5 kHz (t = 4.2, p = 0.008, d = 3.23). Efferent synapses were never observed in the absence of a hair cell.

Figure 8.

Quantification of efferent synapses labeled with antibodies against synaptic vesicle protein (SV2) in young (60-90 d.o.) and old (600-800 d.o.) mice (A-D). Representative maximum-intensity projections of confocal z-stacks of young (120 d.o.) and old (751 d.o.) mouse organ of Corti labeled with antibodies against myosin 6 (hair cells) and SV2 (efferent synapses) (A). Total area of labeling per IHC in young (black) and old (red) mice (B). Number of efferent terminals (C) and total area of labeling per OHC (D). For all panels, young mice consist of 5 females and 3 males; old mice consist of 6 females and 2 males. All points depict means, error bars depict standard errors. Stars indicate significant differences.

Analysis of cochlear cross sections in very old mice revealed patchy hair cell loss throughout the cochlea, with complete loss in some areas (Figure 9). Stria vascularis pathology, as indicated by reduced cross-sectional thickness and increased pigmentation, was observed in old mice (Figure 10). Stria vascularis was significantly thinner in older mice, but only at the apical turn (t = 3.2, p = 0.003, d = 2.69) (Figure 10A-B). Pigmentation of stria vascularis was significantly higher in older mice (t = −9.3, p = 0.001, d = 21.84), in part due to lack of observations of lipofuscin granules in cochleas from young mice. The large pigment granules observed in older mice are consistent with observations in the stria vascularis of aging mice, rats, and humans (Keithley et al. 1992; Ohlemiller et al. 2006; Takahashi, 1971). The reduced thickness of stria vascularis observed in older CBA/CaJ mice is consistent with previous observations in the apical turn of aged rats and humans (Keithley et al. 1992; Takahashi, 1971). Spiral ganglion neuron survival was sparse in very old behaviorally tested mice (Figure 10C-D).

Figure 10.

Examination of stria vascularis (A-B) and spiral ganglion neurons (C-D) in young male (A, C) and old female (B, D) mice. The stria vascularis in old mice contained more melanin and lipofusin granules, indicating degeneration (B). Stria vascularis is thinner at the apical turn in the aged mouse cochlea (B) than in the young mouse cochlea (A). Spiral ganglion in young mouse appears intact (C), while holes are present in the spiral ganglion of the aged cochlea (D). The population of spiral ganglion neurons in the aged cochlea (D) is diminished compared to that of the young cochlea (C), which is another visible indication of degeneration.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we show that the decline for behavioral measures of hearing begins earlier for vocalizations and tones presented in noise compared to sounds presented in quiet. Onset of behavioral hearing deficits differed for vocalizations and tones, with hearing deteriorating most rapidly in the last third of the CBA/CaJ mouse’s lifespan. ABR measurements suggest greater and more variable deterioration than indicated by behavior, and that is linked to substantial peripheral auditory system deterioration.

Consistent with previous studies, old mice showed loss of hair cells along with signs of stria vascularis degeneration. Not surprisingly, mice at the end of their lifespan showed substantial cochlear degeneration and very poor detection of high frequency sounds. The concurrent degeneration of hair cells, neurons, stria vascularis, and auditory synapses confirm that it is difficult, if not impossible, to separate the effects of strial and sensorineural degeneration on ARHL. These factors should be considered in tandem when attempting to make structure-function correlations in aging models. While ABRs do not represent age-related behavioral hearing deficits, they may be more sensitive for detecting peripheral dysfunction, at least at low frequencies (Dallos et al., 1978).

4.1. Deficits in sound detection in quiet and noise

Behavioral sound detection began to deteriorate in middle age, and the onset of threshold elevation occurred earlier for USVs presented in noise compared to quiet. Hearing loss was most severe during the last third of the mouse’s lifespan (650 d.o. and older), and progressed more rapidly for very high frequency tones. Interactions between age, stimulus, sex, and background conditions were observed, indicating that the progression of behavioral hearing deficits cannot be simply predicted by any one variable.

Several parallels can be drawn in comparing presbycusis in humans and mice. Similar to humans, CBA/CaJ mice showed behavioral onset of hearing loss in late adulthood, and lost hearing at a faster rate later in life (Kobrina and Dent, 2016; 2019; Pearson et al., 1995). Humans and mice experience difficulties in detecting simple and complex sounds in noise across the lifespan (Dubno et al., 1984; Zadeh et al., 2019). This is especially interesting because humans experience a rapid decline in understanding speech in noisy conditions with the onset of ARHL. A recent study showed that the understanding and detection of meaningful signals is affected by diminished hearing sensitivity for high frequencies in humans (Zadeh et al., 2019). In mice, high frequency hearing loss also paralleled poor performance for USV detection in noise, suggesting that aging affects USVs and speech processing in similar ways (Anderson et al., 2011). Together, these results suggest that CBA/CaJ mice may serve as a model for studying the interaction of hearing loss and deterioration of speech perception in humans.

Sex as a biological factor has been underrepresented in basic and pre-clinical research on ARHL (Villavisanis et al., 2018; 2019). Nonetheless, several previous studies have established differences in ARHL between males and females, with females exhibiting a later onset of hearing loss (e.g. mice: Kobrina and Dent, 2016; 2019). In this study, female mice showed an overall linear pattern of hearing loss across stimuli and conditions, whereas males exhibited the greatest degree of hearing deterioration in the last third of their lifespan. These findings can likely be explained by the duration of stimuli. Kobrina and Dent (2019) showed that CBA/CaJ female mice had an earlier hearing loss onset for tones of different duration than males. These results highlight the importance of studying a variety of signals in both male and female mice.

ABR measurements confirmed a reduced physiological response to sound with age and revealed delayed central transmission of sound. These results are generally consistent with patterns of ABR changes in aging humans, although results across studies in humans are more variable than in mouse models with more controlled genetic factors and life experiences (Boettcher, 2002). One possible explanation of a delay in the central transmission of sound is deterioration of bushy cell synapses in the ventral cochlear nucleus. When electrically stimulated, aged auditory nerve endbulb-to-bushy cell synapses show asynchronous neurotransmitter release, a higher spike failure rate, and decreased temporal precision (Xie, 2016). These synapses are also unable to sustain activity during prolonged periods of stimulation, which is likely to impair processing in response to sounds in vivo. Interestingly, day-to-day behavioral threshold stability was not adversely affected by age, indicating that central processes may compensate for some aspects of diminished physiological responses.

4.2. Cochlear degeneration in aging mice

The overall pattern of hair cell loss, neural degeneration, and strial degeneration observed in the present study is similar to previous reports in CBA/CaJ mice (Heeringa and Koppl, 2019; Ohlemiller et al., 2010). Mixed cochlear pathology has commonly been reported in humans with ARHL (reviewed by Nelson and Hinojosa, 2006). Outer hair cell and stria vascularis degeneration almost certainly contribute to the age-related hearing deficits observed in CBA/CaJ mice (Ohlemiller et al., 2010). The functional effects of inner hair cell and presynaptic ribbon loss may be more apparent in the ABR deficits than in the behavioral hearing loss. A previous study showed minimal behavioral threshold shifts despite substantial inner hair cell damage (Lobarinas et al., 2013), and 30-50% loss of presynaptic ribbons is associated with suprathreshold ABR deficits in mice (Kujawa and Liberman, 2009; Mehraei et al., 2016).

Our results extend these previous findings by reporting the status of olivocochlear efferent neurons in the aging mouse cochlea. Normal efferent synapse area was observed for surviving outer hair cells except in the extreme cochlear apex, although overall the number of synaptic terminals was reduced. The reduction occurred primarily in basal and apical frequency regions where significant outer hair cell loss was also observed. It is unclear why some terminals may be more vulnerable to loss than others.

Lateral efferent innervation also remained intact for most cochlear regions. Increased efferent innervation in the vicinity of inner hair cells was observed in the extreme base. A similar increase in olivocochlear innervation has been reported in C57BL6 mice, a model of accelerated ARHL due to a mutation of the cadherin 23 gene (Lauer et al., 2012; Zachary and Fuchs, 2015). In the hearing-impaired C57BL6 mouse, olivocochlear efferents form large, inhibitory synapses directly with the inner hair cells, leading to reduced hair cell activity. The increased efferent innervation of inner hair cells may serve to protect the hair cell and remaining presynaptic ribbons against degeneration, but it also may worsen high frequency hearing deficits by further reducing sound-induced afferent activation.

Deficits in the strength of the olivocochlear reflex have been reported in aging humans, but it is difficult to distinguish from these data how much of the reduced activation is due to reduced afferent activation of the system by the eliciting stimulus (Abdala et al., 2014; Jacobson et al., 2003; Keppler et al., 2010; Lauer, 2017; Parthasarathy, 2001). A recent study of postmortem temporal bone specimens identified an age-related loss of medial olivocochlear neurons with mostly intact lateral olivocochlear neurons, similar to what we observed in the present study (Liberman and Liberman, 2019). The peripheral loss of the medial olivocochlear neurons is much greater than the degree of central loss of medial olivocochlear cell bodies reported in gerbils (Radtke-Schuller et al., 2015). Thus, medial olivocochlear peripheral processes may degenerate more quickly than central neural components as is known to occur with the auditory nerve (McGuire et al., 2015). An overall loss of medial olivocochlear synapses may contribute to the behavioral detection in noise deficits observed in aging mice.

5. Conclusions

The present study highlights the need to consider a constellation of simultaneously occurring degeneration and compensatory mechanisms in auditory structures when trying to understand structure-function relationships in age-related behavioral hearing deficits. Behavioral characterization of hearing in addition to the more commonly performed ABR estimates of hearing loss are paramount to drawing similarities between human auditory deficits and animal models. This is especially important for optimizing the success of pharmaceutical interventions, regenerative therapies, and assistive devices, since human patients seek treatment for hearing loss primarily because of behavioral, not physiological or anatomical, complaints. Future studies linking behavioral outcomes with individual patterns of degeneration and central compensation can inform the development of more precise diagnostic tools and contribute to more personalized treatment strategies.

6. Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIDCD grants R01-DC012302 to MLD, R01-DC016641 to MLD and AML, R01 DC017620 to AML, F31-DC016545 to AK, T32-DC000023 to LAS, Acoustical Society of America James E. West Fellowship to DFV, and the David M. Rubenstein Fund for Hearing Research to AML.

We thank James Engel and Lauren Brewster for assistance with imaging the anatomical specimens. We would also like to thank Ethan Gorman and Jack Kiesow, as well as numerous graduate and undergraduate assistants in the Dent Lab for their help with behavioral data collection.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

8. References

- Abdala C, Dhar S, Ahmadi M, Luo P. Aging of the medial olivocochlear reflex and associations with speech perception. J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 135 (2014), pp. 754–765. doi: 10.1121/1.4861841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel SM, Krever EM, Alberti PW. Auditory detection, discrimination and speech processing in ageing, noise-sensitive and hearing-impaired listeners. Scand. Audiol, 19 (1990), pp. 43–54. doi: 10.3109/01050399009070751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado JC, Fuentes-Santamaría V, Gabaldón-Ull MC, Blanco JL, Juiz JM. Wistar rats: a forgotten model of age-related hearing loss. Front. Aging Neurosci, 6 (2014), pp. 29. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S, Parbery-Clark A, Yi HG, Kraus N. A neural basis of speech-in-noise perception in older adults. Ear Hear., 32 (2011), pp. 750–757. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31822229d3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon SP, Opie JM, Montoya DY. The effects of hearing loss and noise masking on the masking release for speech in temporally complex backgrounds. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res, 41 (1998), pp. 549–563. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4103.549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan U, Freyman RL. Speech detection in spatial and nonspatial speech maskers. J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 123 (2008), pp. 2680–2691. doi: 10.1121/1.2902176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banay-Schwartz M, Lajtha A, Palkovits M. Changes with aging in the levels of amino acids in rat CNS structural elements II. Taurine and small neutral amino acids. Neurochem. Res 14 (1989), pp.563–570. doi: 10.1007/bf00964919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao J, Ohlemiller KK. Age-related loss of spiral ganglion neurons. Hear. Res, 264 (2010), pp. 93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw, (2014), arXivpreprint arXiv:1406.5823 [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher FA. Presbyacusis and the auditory brainstem response. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res, 45 (2002), pp. 1249–1261. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/100) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredberg G. The human cochlea during development and ageing. J. Laryngol. Otol, 81 (1967), pp. 739–58. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100067670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buran BN, Strenzke N, Neef A, Gundelfinger ED, Moser T, Liberman MC. Onset coding is degraded in auditory nerve fibers from mutant mice lacking synaptic ribbons. J. Neurosci, 30(22) (2010), pp. 7587–97. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0389-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke K, Screven LA, Dent ML. CBA/CaJ mouse ultrasonic vocalizations depend on prior social experience. PloS one, 13(6) (2018), pp. e0197774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspary DM, Ling L, Turner JG, Hughes LF. Inhibitory neurotransmission, plasticity and aging in the mammalian central auditory system. J. Exp. Biol, 211 (2008), pp. 1781–1791. doi: 10.1242/jeb.013581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers AR, Resnik J, Yuan Y, Whitton JP, Edge AS, Liberman MC, Polley DB. Central gain restores auditory processing following near-complete cochlear denervation. Neuron, 89 (2016), pp. 867–879. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.12.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cediel R, Riquelme R, Contreras J, Díaz A, Varela-Nieto I. Sensorineural hearing loss in insulin-like growth factor I-null mice: A new model of human deafness. European Journal of Neuroscience, 23(2), (2006), pp. 587–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04584.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Committee on Hearing, Bioacoustics and Biomechanics. Speech understanding and aging. J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 83 (1988), pp. 859–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe SJ, Guild SR. Impaired hearing for high tones. Acta Otolaryngol., 26 (1938), pp. 138–144. doi: 10.3109/00016483809118435 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, Harris D, Özdamar Ö, Ryan A. Behavioral, compound action potential, and single unit thresholds: relationship in normal and abnormal ears. J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 64(1) (1978), pp. 151–157. doi: 10.1121/1.381980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diedenhofen B, Musch J, cocor: A comprehensive solution for the statistical comparison of correlations. PloS one, 10 (2015), pp. e0121945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubno JR, Dirks DD, Morgan DE. Effects of age and mild hearing loss on speech recognition in noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 76(1984), pp. 87–96. doi: 10.1121/1.391011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engström B, Hillerdal M, Laurell G, Bagger-Sjöbäck D. Selected pathological findings in the human cochlea. Acta Otolaryngol., 104 (1987), pp. 110–116. doi: 10.3109/00016488709124983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldblum S, Erlander MG, Tobin AJ. Different distributions of GAD65 and GAD67 mRNAS suggest that the two glutamate decarboxylases play distinctive functional roles. J. Neurosci. Res, 34 (1993), pp. 689–706. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490340612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]