Abstract

Introduction

Given the pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19), persistent pulmonary abnormalities are likely.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study in severe COVID-19 patients who had oxygen saturation < 94% and were primarily admitted to hospital. We aimed to describe persistent gas exchange abnormalities at 4 months, defined as decreased diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLco) and/or desaturation on the 6-minute walk test (6MWT), along with associated mechanisms and risk factors.

Results

Of the 72 patients included, 76.1% required admission to an intensive care unit (ICU), while 68.5% required invasive mechanical ventilation (MV). A total of 39.1% developed venous thromboembolism (VTE). After 4 months, 61.4% were still symptomatic. Functionally, 39.1% had abnormal carbon monoxide test results and/or desaturation on 6MWT; high-flow oxygen, MV, and VTE during the acute phase were significantly associated. Restrictive lung disease was observed in 23.6% of cases, obstructive lung disease in 16.7%, and respiratory muscle dysfunction in 18.1%. A severe initial presentation with admission to ICU (P = 0.0181), and VTE occurrence during the acute phase (P = 0.0089) were associated with these abnormalities. 41% had interstitial lung disease in computed tomography (CT) of the chest. Four patients (5.5%) displayed residual defects on lung scintigraphy, only one of whom had developed VTE during the acute phase (5.5%). The main functional respiratory abnormality (31.9%) was reduced capillary volume (Vc < 70%).

Conclusion

Among patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia who were admitted to hospital, 61% were still symptomatic, 39% of patients had persistent functional abnormalities and 41% radiological abnormalities after 4 months. Embolic sequelae were rare but the main functional respiratory abnormality was reduced capillary volume. A respiratory check-up after severe COVID-19 pneumonia may be relevant to improve future management of these patients.

Keywords: COVID-19, Follow-up, Sequelae: Pulmonary embolism, Fibrosis

Take-home message.

Among patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia who were admitted to hospital, 61% were still symptomatic after 4 months. Moreover, 39% of patients had persistent functional abnormalities and 41% radiological abnormalities. Embolic sequelae were rare but the main functional respiratory abnormality was reduced capillary volume.

Abbreviations

- 6MWT

6-minute walk test

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CO/NO

carbon monoxide/nitric oxide

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 19

- CPET

cardiopulmonary exercise testing

- CT

computed tomography

- DLco

diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide

- HRCT

high-resolution computed tomography

- ICU

intensive care unit

- ILD

interstitial lung disease

- Kco

carbon monoxide transfer coefficient

- MERS-CoV

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- MV

mechanical ventilation

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- SARS-CoV-2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- Vc

capillary volume

- VTE

venous thromboembolism

1. Introduction

SARS-CoV-2, or severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, is a virus of the Coronaviridae family, like SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV (Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus). Viral pneumonia may cause acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) with direct implications for prognosis. Six percent of patients with coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) are admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) [1], and 2% require mechanical ventilation (MV). Patients with severe lung disease receive standard intensive care and corticosteroids [2] based on evidence from the randomised trial RECOVERY, which shows that the use of dexamethasone reduces 28-day mortality in patients requiring respiratory support, particularly in those on MV [3].

ARDS damages the alveoli by mechanisms which depend on the aetiology, and increases the risk of progression to pulmonary fibrosis. Meduri et al. [4] described fibrotic lesions in the lungs in half of patients who died from ARDS. It has been reported that post-ARDS fibrotic lesions lead to decreased diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLco) 3 months after extubation; and that 80% of patients recovered normal respiratory function within a year [3], [5], [6].

Besides parenchymal pulmonary lesions, COVID-19 patients are also more prone to pulmonary thromboembolism. A severe hypercoagulable state has been demonstrated in patients admitted to ICU, which makes the case for uncontrolled hyper-inflammatory phase as mentioned above [7]. In a recent cohort of 184 critical COVID-19 patients admitted to ICU, 31% developed venous or arterial thrombotic complications, 80% of which involved pulmonary embolism [8], [9]. The long-term impact of such thromboembolic complications is uncertain.

There are suggested follow-up protocols for patients after COVID-19 pneumonia, particularly for respiratory function [10]. The respiratory repercussions of such pneumonia on lung parenchyma and vascularisation are unclear. Georges et al. [10] suggested screening for interstitial and pulmonary vascular disease, particularly if embolism occurred during the acute phase.

This study aims to describe the characteristics of persistent gas exchange abnormalities 4 months after severe COVID-19 pneumonia, in patients without prior cardiopulmonary disease.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study design

This prospective cohort study was conducted in Toulouse University Hospital, France, between April and September 2020.

The inclusion criteria were COVID-19 pneumonia diagnosed by positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay using a respiratory sample from the saliva, nasopharynx, bronchi, tracheal aspirate or bronchoalveolar lavage. The patient's condition had to require hospitalization, with clinical and radiological lung involvement: saturation below 94% without respiratory support and computed tomography (CT) of the chest, presenting common features of COVID-19 pneumonia. Patients had to be 18 years old or more, and give a written informed consent.

The exclusion criteria were lung disease not documented on CT of the chest, negative COVID-19 PCR, and prior cardiopulmonary disease that could itself provoke abnormal gas exchange.

This study was approved by “Le Comité de Protection des Personnes”, the institutional review board of Brest University Hospital, as an interventional study involving human subjects that presents minimal risks and constraints for patients (RIPH 20.05.07.57618).

2.2. Methods

The primary objective was to describe persistent gas exchange abnormalities at 4 months, defined by abnormal pulmonary diffusing capacity and oxygen desaturation during a 6MWT.

The secondary objectives were to identify the mechanisms of persistent gas exchange abnormalities and their severity; determine the prevalence of persistent respiratory symptoms; determine the nature of persistent bronchial and ventilatory abnormalities; describe the persistent pulmonary abnormalities on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) and lung scintigraphy; compare symptomatic and asymptomatic patients after 4 months to identify the pathophysiological mechanisms of persistent symptoms; and identify risk factors for persistent respiratory abnormalities in clinical, laboratory and imaging assessments or related to initial patient management.

To determine the mechanism of gas exchange abnormalities, several parameters were analysed: (I) other values from the carbon monoxide/nitric oxide (CO/NO) test, specifically Krogh's diffusion coefficient, capillary volume, and membrane diffusion capacity; (II) plethysmography and respiratory muscle evaluation (sniff nasal inspiratory pressure, maximal inspiratory pressure); (III) HRCT findings; and (IV) lung scintigraphy findings. NO was measured with CO to screen for abnormalities of the pulmonary capillaries.

Patients were considered symptomatic at 4 months if the following criteria were reported:

-

•

dyspnoea on the modified Medical Research Council scale, cough on the Leicester Cough Questionnaire, expectoration, haemoptysis, chest pain, evidence of right ventricular failure, or sleeping disorders;

-

•

and/or distance covered on the 6-minute walk test (6MWT) < 80% of predicted distance.

Persistent ventilatory or bronchial abnormalities at 4 months were defined from plethysmography, forced oscillation technique, diaphragmatic examination or exhaled NO, by:

-

•

obstructive lung disorder (ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second to forced vital capacity < 70%);

-

•

restrictive lung disorder (total lung capacity < 80% of predicted value);

-

•

impairment of respiratory muscles consistent with diaphragmatic dysfunction (maximum inspiratory pressure and/or sniff nasal inspiratory pressure < 60% of predicted value, or decrease in vital capacity when lying down compared with sitting > 15%);

-

•

eosinophilic bronchial inflammation (increased fractional exhaled NO);

-

•

suggestive of proximal or distal airway obstruction with a decrease in impedance measurements on the forced oscillation technique [11].

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is defined as a heterogeneous group of non-neoplastic disorders resulting from damage to the lung parenchyma by varying patterns of inflammation and fibrosis [12]. Radiological elementary lesions of ILD (ground-glass opacities, alveolar and reticular opacities, micronodules) [13] and bronchiectasis were determined during a multidisciplinary meeting with specialised thoracic radiologists who analysed HRCT. Ventilation/perfusion scintigraphy was also analysed for perfusion defects with normal ventilation.

The check-up was completed with laboratory tests: ionogram, urea, creatinine, creatinine clearance, liver function test, Nt-proBNP, D-Dimers, cardiolipid antibodies, anti-Beta-2 GP1 antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, complete blood count, CRP, ferritin, CPK, LDH, coagulant test, fibrinogen, SARS-CoV-2 serology, and Beta-HCG in women of childbearing age.

The second-line assessment was left to investigator's judgement depending on respiratory abnormalities: bronchoalveolar lavage for interstitial disease; thoracic CT angiography, echocardiography, right catheterism, cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) for vascular abnormalities; methacholine testing, diaphragmatic echography in the event of respiratory muscle impairment; hyperventilation testing, CPET and echocardiography for dyspnoea of undetermined cause.

Characteristics of symptomatic patients were compared to asymptomatic. Symptoms were correlated to findings from additional examinations.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The required sample size was defined by the expected accuracy in estimating the prevalence of these abnormalities: with at least 60 patients and a prevalence of 50%, the 95% confidence interval (CI) was ± 13% (37%, 63%).

The primary composite endpoint was an adjusted decreased diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLco) < 70% of predicted value on the CO test and/or decrease of 4% or more in oxygen saturation on the 6MWT.

Exchange abnormalities at 4 months were described by estimating their prevalence with a 95% CI. Regarding second endpoints, prevalence of symptoms and pulmonary complications were estimated with a 95% CI.

Missing data were described, and aberrant data were screened using logical checks. Patient characteristics at inclusion were described as number and percentage for qualitative variables, and as mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum and quartiles for quantitative variables. The distribution of potential risk factors at inclusion were described and compared between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, as well as between patients with and without pulmonary complications. Comparisons were adjusted for the type of variable and conditions under which the tests were applied–i.e. Chi2 or Fisher's exact test, and Student's t-test or the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to evaluate associations between the risk factors and the two secondary endpoints of being symptomatic at 4 months and developing respiratory complications.

3. Results

3.1. Population characteristics

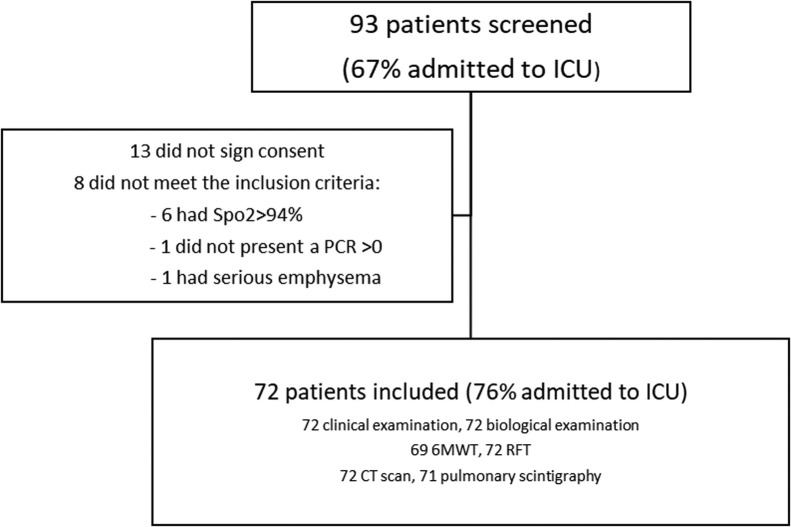

93 patients were selected, 72 of whom were retained for analysis (Fig. 1 ) (Table 1 ). Their respiratory function was assessed 4.3 months after PCR diagnosis on average.

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart. ICU: intensive care unit; SpO2: oxygen saturation; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; 6MWT: 6-minute walk test; RFT: respiratory function tests; CT: computed tomography.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study patients.

| Number of patients (%) | |

|---|---|

| Characteristics on inclusion | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 55 (76) |

| Female | 17 (24) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never a smoker | 36 (56) |

| Former smoker | 21 (32) |

| Currently a smoker | 8 (12) |

| Acute phase management | |

| Intensive care unit | 54 (76) |

| Intensive care unit admission | |

| PaO2/FiO2 (mmHg/FiO2) | 109 [88; 148] |

| HFO | 18 (34) |

| Non-invasive ventilation | 13 (24) |

| Use of curare | 33 (65) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 37 (68) |

| Prone positioning | 29 (54) |

| Use of nitric oxide | 5 (9) |

| ECMO | 3 (6) |

| Extrarenal purification | 4 (7) |

| Drug therapies | |

| Corticosteroids | 26 (36) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 38 (53) |

| Azithromycin | 1 (1) |

| Ritonavir/lopinavir | 8 (11) |

| Remdesivir | 8 (11) |

| Antibiotics | 68 (94) |

| Curative anticoagulation | 27 (37) |

| Complications | |

| Bacterial pneumonia | 36 (51) |

| Fungal infection | 3 (4) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 23 (32) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 18 (25) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 9 (12) |

| ARDS | 41 (57) |

| Myocarditis | 1 (1) |

| Post-intensive care tetraparesis | 16 (22) |

| Baseline CT abnormalities | |

| Mild (< 10%) | 6 (9) |

| Moderate (10–25%) | 16 (25) |

| Extensive (25–50%) | 20 (31) |

| Severe (50–75%) | 17 (26) |

| Critical (> 75%) | 6 (9) |

PaO2/FiO2: ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen; HFO: high-flow oxygen; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome.

The population was 76.4% men, and the mean age was 60.5 years (± 12.8). Their comorbidities were overweight (42.6%), obesity (40%), hypertension (38.5%), diabetes (23%), coronary artery disease (8%) and cancer (12%). 76.1% were admitted to ICU for a mean of 21.1 days, 68.5% required MV for a mean of 19.4 days, and 53.7% were placed in a prone position, with three of those patients receiving high-flow oxygen (HFO). A total of 36.1% patients were treated with corticosteroids started 13 days after diagnosis and for a mean duration of 25 days. 56.9% of patients developed ARDS, and 22.2% post-intensive care tetraparesis. Additionally, 50.7% developed secondary bacterial infections and 31.9% venous thromboembolism (VTE), with 78.3% of these cases involving pulmonary embolism.

3.2. 4-month assessment: symptoms and respiratory function

The 4-month clinical and paraclinical check-up presented normal results in 30.6% of patients, whereas 10% exhibited deconditioning; 44.4% had interstitial lung disease (ILD), with architectural distortion in 56% of cases; 7% had bronchial hyper-reactivity; and 18.1% diaphragmatic muscle dysfunction (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Respiratory workup at 4 months.

| Number of patients (%) | |

|---|---|

| Primary endpoint–DLco < 70% or decrease of 4% or more in oxygen saturation in the 6MWT | 27 (39) |

| Clinical examination | |

| Symptoms | 43 (61) |

| Dyspnoea | 32 (44) |

| mMRC 0–2 | 28 (88) |

| mMRC 3–4 | 4 (12) |

| Asthenia | 22 (31) |

| Cough | 12 (17) |

| Thoracic pain | 5 (7) |

| Pulmonary function testing | |

| Decrease of > 4% in SpO2 in the 6MWT | 15 (22) |

| Corrected DLco < 70% | 18 (25) |

| KCO < 70% | 0 |

| VC < 70% | 22 (32) |

| Dm < 70% | 3 (4) |

| TLC < 80% | 20 (28) |

| FEV1 < 80% | 9 (12) |

| FEV1/FVC < 70% | 12 (17) |

| Impaired respiratory muscles | 13 (18) |

| 6MWT % pred | 92.6 [79–108] |

| TLC % pred | 88.4 [79-99.5] |

| RV % pred | 88.4 [73–108] |

| KCO % pred | 106.2 [97–115] |

| DLCO % pred | 83.7 [67–98] |

| Vc % pred | 75.7 [62–89] |

| Dm % pred | 111.8 [89–131] |

| FEV 1% pred | 97.9 [87–106] |

| FVC % pred | 94.6 [83–104] |

| Pi % pred | 103.3 [82–127] |

| SNIP % pred | 94 [65–96] |

| Lung scintigraphy | |

| Perfusion defect | 4 (6) |

| Computed tomography of the chest | |

| Normal | 22 (31) |

| Interstitial lung disease | 32 (44) |

| Bronchial distortion | 18 (25) |

DLco: diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide; 6MWT: 6-minute walk test; mMRC: modified Medical Research Council scale; SpO2: oxygen saturation; KCO: carbon monoxide transfer coefficient; Vc: pulmonary capillary blood volume; Dm: membrane conductance; TLC: total lung capacity; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC: forced vital capacity.

A total of 61.4% of patients described themselves as symptomatic. Although their symptoms varied, most (44.4%) had dyspnoea, 10.3% of whom were 3 to 4 on the mMRC scale, 30.6% had asthenia and 16.7% coughing (Table 2).

Regarding the primary endpoint, 39.1% had abnormal CO test results while 22.1% presented desaturation on the 6MWT. A total of 26.4% had abnormal gas exchange function in the CO/NO test, with a median pulmonary capillary blood volume (Vc) of 77% of predicted value (58; 91) and 31.9% of Vc < 70% which was the most frequent abnormal finding. The carbon monoxide transfer coefficient (Kco) was normal in all cases with a median of 105% (96; 116). 23.6% had restrictive lung disorders and 16.7% obstructive disorders, with 40% partially reversible. Mean fractional exhaled NO was 16.1 parts per billion. Furthermore, 18.1% had respiratory muscle dysfunction (Table 2), leading to a diagnosis of diaphragmatic paralysis in 7% of them. This was mostly linked to neuromuscular abnormalities acquired in ICU, but in one case the multidisciplinary diagnosis was Parsonage-Turner syndrome.

3.3. 4-month assessment: chest imaging

Only four patients (5.5%) displayed residual defects on ventilation/perfusion scintigraphy at 4 months. All four had normal scintigraphy after three months of anticoagulation.

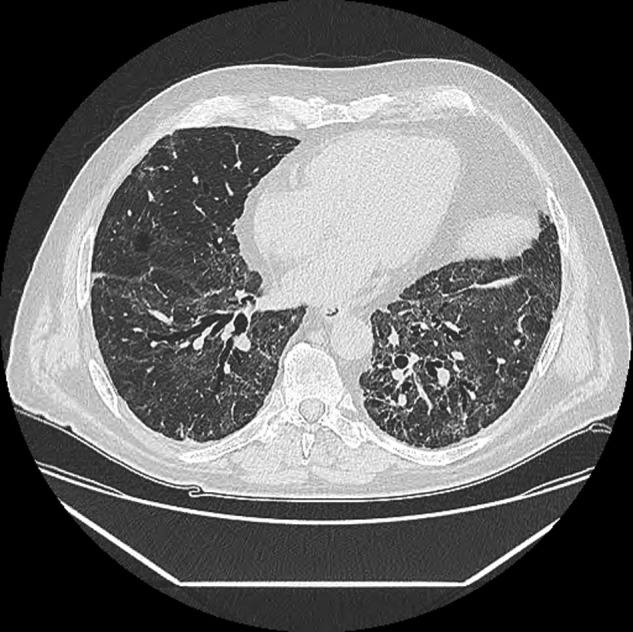

Thirty one percent of HRCT were normal, 46% presented ground-glass opacities, 25% reticular opacities, 6% alveolar opacities, 7% micronodules, 23% bronchiectasis and no honeycombing. After a multidisciplinary meeting, it was concluded that 44.4% of patients had persistent ILD at 4 months, 56% of them with architectural distortion (Fig. 2 ). This distortion was peripheral in 55.5% of cases, central in 33.3%, and mixed in 11%, and affected a mean of 3 lobes (1–6), the lingula being the most frequently involved (67%).

Fig. 2.

Chest computed tomography at 4 months.

3.4. Factors associated with gas exchange abnormalities

Admission to ICU, invasive MV and its duration, and prone position were associated with abnormal gas exchange, as were complications such as VTE, ARDS and tetraparesis (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Risk factors for respiratory abnormalities and persistent interstitial lung disease after 4 months.

| Primary endpoint–DLco < 70% or decrease of 4% or more in oxygen saturation in the 6MWT |

Secondary endpoint–persistent ILD |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 42) | Yes (n = 27) | P-value | No (n = 42) | Yes (n = 27) | P-value | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 30 (71) | 23 (85) | 0.1864 | 29 (72) | 26 (81) | 0.385 |

| Female | 12 (29) | 4 (15) | 11 (28) | 6 (19) | ||

| Intensive care unit admission | ||||||

| HFO | ||||||

| No | 33 (80) | 16 (61) | 0.0882 | 33 (85) | 19 (61) | 0.0266a |

| Yes | 8 (20) | 10 (39) | 6 (15) | 12 (39) | ||

| Non-invasive ventilation | ||||||

| No | 38 (93) | 16 (62) | 0.0017a | 35 (90) | 22 (71) | 0.0448a |

| Yes | 3 (7) | 10 (38) | 4 (10) | 9 (29) | ||

| Mechanical ventilation | ||||||

| No | 26 (63) | 5 (18) | 0.0003a | 25 (64) | 9 (28) | 0.0025a |

| Yes | 13 (37) | 22 (82) | 14 (36) | 23 (72) | ||

| Prone positioning | ||||||

| No | 30 (73) | 9 (33) | 0.0012a | 32 (82) | 10 (31) | 0.0a |

| Yes | 11 (27) | 18 (67) | 7 (18) | 22 (69) | ||

| Complications and severity | ||||||

| VTE | 1 | |||||

| No | 33 (79) | 13 (48) | 0.0089a | 35 (87) | 4 (44) | 0.0001a |

| Yes | 7 (17) | 14 (52) | 5 (13) | 18 (56) | ||

| ARDS | ||||||

| No | 24 (57) | 4 (15) | 0.0005a | 24 (60) | 7 (22) | 0.0012a |

| Yes | 18 (43) | 23 (85) | 16 (40) | 25 (78) | ||

| Tetraparesis | ||||||

| No | 38 (91) | 15 (56) | 0.0008a | 38 (95) | 18 (56) | 0.0001a |

| Yes | 4 (9) | 12 (44) | 2 (5) | 14 (44) | ||

| Baseline CT abnormalities | ||||||

| Mild < 10% | 5 (13) | 0 | 0.0166b | 5 (14) | 1 (3) | 0.2566 |

| Moderate 10–25% | 12 (30) | 4 (17) | 11 (31) | 5 (17) | ||

| Extensive 25–50% | 14 (35) | 5 (22) | 11 (31) | 9 (31) | ||

| Severe 50–75% | 8 (20) | 9 (39) | 7 (19) | 10 (35) | ||

| Critical > 75% | 1 (2) | 5 (22) | 2 (5) | 4 (14) | ||

DLco: diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide; 6MWT: 6-minute walk test; ILD: interstitial lung disease; HFO: high-flow oxygen; VTE: venous thromboembolism; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; CT: computed tomography.

P-value <0.05 (Chi2).

P-value < 0.05 (Exact).

Patients presenting abnormal gas exchange tended to have received corticosteroids later, specifically 15.3 days versus 10 days after PCR diagnosis. This effect was adjusted for initial severity of the disease.

Initial CT severity was also associated with abnormal gas exchange (P = 0.01).

3.5. Factors associated with persistent interstitial lung disease

Admission to ICU was generally associated with an increased risk of persistent ILD (P = 0.001), as were MV, HFO and prone position (Table 3).

Most patients with ILD at 4 months were admitted to ICU (6.3% vs. 93.8%, P = 0.001) and treated with MV, HFO and prone position. They also had significantly more complications including VTE, ARDS and tetraparesis.

It seems that persistence of ILD was influenced by time delays from diagnosis to commencement of treatment with steroids. In patients presenting ILD, steroids were started 15.3 days after PCR diagnosis, but 8.6 days in those who did not (non-significant result, P = 0.0726), regardless of the severity of the initial disease.

However, patients with ILD were not more symptomatic nor dyspnoeic than others.

Patients presenting ILD with distortion seemed to have displayed more severe forms than those without, required MV and the drug curare more frequently, and developed more VTE. They may have received less corticosteroid medication than ILD patients without distortion (50% vs. 57.1%, non-significant result).

3.6. Comparison of symptomatic and asymptomatic patients

Persistent symptoms did not significantly correlate with any of the risk factors assessed.

4. Discussion

Four months after a moderate to severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, less than half the patients had persistent diffusion abnormalities. The main predictive factors for this respiratory impairment were disease severity during initial presentation and VTE occurrence during the acute phase.

Nearly half the patients displayed ILD on HRCT at 4 months. Bronchial distortion was frequently observed, even in those not treated with MV. These pulmonary lesions may partly explain why gas exchange abnormalities persisted at 4 months. In this study, corticosteroids were mostly initiated in severe cases, remotely after initial diagnosis. Patients who received corticosteroids earlier tended to present fewer functional and radiographic sequelae at 4 months. Guidance on steroids in COVID-19 pneumonia has been provided by the World Health Organisation [5] although dedicated studies may help determine the appropriate delay and duration of this treatment.

A study characterising respiratory function 3 and 6 months after SARS infection [14] revealed that 15% of survivors had reduced surface area for gas exchange, while DLco was significantly lower at 6 months in the subgroup of patients admitted to ICU. These abnormalities were partly due to lung injury, since other factors such as effort deconditioning and respiratory muscle dysfunction were also involved, as in the present study. In the study by Luyt et al. [15] on 1-year sequelae in survivors of H1N1-related ARDS, impaired gas exchange and persistent dyspnoea were found in 64% and 56% of patients who did not require extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Sonnweber et al. [16] described in a prospective study, 3 months after mild to severe SARS-Cov-2 infection: 36% dyspnoea, 21% restrictive ventilatory disorder, 11% impaired DLco, with ILD pattern in 63% of 145 individuals, 50% of whom required oxygen supply and 22% of whom were admitted to ICU. Arnold et al. [17] described at 3 months: of 110 COVID-19 survivors, 39% had dyspnoea, 11% restrictive ventilatory disorder, and 14% desaturation in a 6-minute walk test (6MWT). Shah et al. [18] described, 3 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection, without specifying severity in their population: 20% dyspnoea, 7% SpO2 ≤ 88% at the end of the 6MWT, 52% DLCO < 80% with 45% concurrent restrictive ventilatory deficit, and 11% airflow obstruction. In the HRCT assessment, 83% of patients had ground glass, 65% reticulation and only 12% with neither imaging abnormality. Chest CT sequelae and DLco impairment were significantly associated with numerous days on oxygen supplementation, used as a proxy for acute phase severity.

Besides post-ARDS sequelae, COVID-19 lung disease patients also displayed persistent reticulation at HRCT assessment 4 weeks after the onset of symptoms [19]. Prospective studies would therefore be useful to determine the risk of pulmonary fibrosis after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The abnormalities described in this cohort are comparable to those reported in the literature. Although the COVID-19 pandemic involves more patients than other epidemics, the prevalence of ILD with architectural distortion was substantial, and it would be useful to assess long-term sequelae.

Based on data from literature on other viruses and ARDS, Ojo et al. [20] suggest that certain factors may predict the risk of developing pulmonary fibrosis, including age, duration of ICU hospitalisation and MV, smoking, and alcoholism. These parameters were also identified as risk factors in this cohort, with the exception of smoking and alcoholism.

The main functional respiratory abnormality in this study was reduced Vc. However, the reduction was moderate and not associated with radiographic abnormalities or the persistence of symptoms, including dyspnoea. It may have resulted from capillary inflammation during the acute phase of COVID-19.

The current available data about the risk of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease following COVID-19 infection are reassuring. Georges et al. [10] suggested assessing scintigraphy and echocardiography at 3 months for all patients who develop pulmonary embolism during a SARS-CoV-2 infection. A 46 to 66% prevalence of persistent pulmonary scintigraphy abnormalities 3 months after acute idiopathic pulmonary embolism in non-infectious diseases has been reported [21], [22], which is higher than the results found in this study. Three patients had scintigraphy defects at 4 months, probably due to undiagnosed pulmonary embolism during the acute phase or subsequent rehabilitation. After 3 months of anticoagulation all the scintigraphy defects disappeared.

Persistent symptoms at 4 months, particularly dyspnoea and asthenia, were common in this study, as in recent prospective studies [16], [17], [23]. However, no predictive factor was found, not even initial severity or management, implying a multifactorial process.

This study was limited by its single-centre design. It should be mentioned that transthoracic echocardiography was not always performed to assess the risk of pulmonary arterial hypertension. The examination was conducted later if the respiratory check-up revealed isolated dyspnoea and/or reduced DLco.

5. Conclusion

Among patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia who were admitted to hospital, 61% were still symptomatic after 4 months but no predicting factor was found. Moreover, 39% of patients had persistent functional abnormalities and 41% radiological abnormalities. Embolic sequelae were rare but the main functional respiratory abnormality was reduced capillary volume, probably as a result of capillary inflammation. A respiratory check-up after severe COVID-19 pneumonia may be useful to improve future management of patients: physical examination, 6 MWT, diffusion capacity test and chest CT.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Support statement

The study was supported by the institution: Toulouse University Hospital.

Funding

Toulouse Hospital

References

- 1.Guan W.-J., Ni Z.-Y., Hu Y., Liang W.-H., Ou C.-Q., He J.-X., et al. Clinical characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . 2020. Corticosteroids for COVID-19 Living guidance. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McHugh L.G., Milberg J.A., Whitcomb M.E., Schoene R.B., Maunder R.J., Hudson L.D. Recovery of function in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:90–94. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.1.8025779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meduri G.U. Late adult respiratory distress syndrome. New Horiz Baltim Md. 1993;1:563–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suchyta M.R., Elliott C.G., Colby T., Rasmusson B.Y., Morris A.H., Jensen R.L. Open lung biopsy does not correlate with pulmonary function after the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Chest. 1991;99:1232–1237. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.5.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassenstein J., Riede U.N., Mittermayer C., Sandritter W. Reversibility of shock-induced pulmonary fibrosis (author's transl) Anasth Intensivther Notf Med. 1980;15:340–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spiezia L., Boscolo A., Poletto F., Cerruti L., Tiberio I., Campello E., et al. COVID-19-related severe hypercoagulability in patients admitted to intensive care unit for acute respiratory failure. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120:998–1000. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., Meer van der N.J.M.V., Arbous M.S., Gommers D.A. M.P.J., Kant K.M., et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res Elsevier. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cui S., Chen S., Li X., Liu S., Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1421–1424. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George P.M., Barratt S.L., Condliffe R., Desai S.R., Devaraj A., Forrest I., et al. Thorax [Internet] BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2020. Respiratory follow-up of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. [cited 2020 Aug 29]; Available from: https://thorax.bmj.com/content/early/2020/08/24/thoraxjnl-2020-215314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oostveen E., MacLeod D., Lorino H., Farré R., Hantos Z., Desager K., et al. The forced oscillation technique in clinical practice: methodology, recommendations and future developments. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:1026–1041. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00089403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias This Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, June 2001 and by The ERS Executive Committee, June 2001. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:277–304. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.2.ats01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imaging of interstitial lung disease. Clin Chest Med Elsevier. 2004;25:455–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hui D.S., Joynt G.M., Wong K.T., Gomersall C.D., Li T.S., Antonio G., et al. Impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) on pulmonary function, functional capacity and quality of life in a cohort of survivors. Thorax. 2005;60:401–409. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.030205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luyt C.-E., Combes A., Becquemin M.-H., Beigelman-Aubry C., Hatem S., Brun A.-L., et al. Long-term outcomes of pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1)-associated severe ARDS. Chest. 2012;142:583–592. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sonnweber T, Sahanic S, Pizzini A, Luger A, Schwabl C, Sonnweber B, Kurz K, Koppelstätter S, Haschka D, Petzer V, Boehm A, Aichner M, Tymoszuk P, Lener D, Theurl M, Tancevski A, Schapfl A, Schaber M, Hilbe R, Puchner B, Hüttenberger D, Tschurtschenthaler C, Aßhoff M, Peer A, Hartig F, Bellmann R, Joannidis M, Gollmann C, Holfeld J, Feuchtner G, et al. Cardiopulmonary recovery after COVID-19–an observational prospective multi-center trial. Dyspnoea and asthenia are the most frequent symptoms: 40.

- 17.Arnold D.T., Hamilton F.W., Milne A., Morley A.J., Viner J., Attwood M., et al. Thorax [Internet] BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2020. Patient outcomes after hospitalisation with COVID-19 and implications for follow-up: results from a prospective UK cohort. [cited 2020 Dec 23]; Available from: https://thorax.bmj.com/content/early/2020/12/02/thoraxjnl-2020-216086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah A.S., Wong A.W., Hague C.J., Murphy D.T., Johnston J.C., Ryerson C.J., et al. A prospective study of 12-week respiratory outcomes in COVID-19-related hospitalisations. Thorax. 2020 doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216308. thoraxjnl-2020-216308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu Q., Guan H., Sun Z., Huang L., Chen C., Ai T., et al. features and temporal lung changes in COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Eur J Radiol. 2020;128:109017. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.109017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ojo A.S., Balogun S.A., Williams O.T., Ojo O.S. Pulmonary Fibrosis in COVID-19 Survivors: predictive factors and risk reduction strategies. Pulm Med. 2020;2020:6175964. doi: 10.1155/2020/6175964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonnefoy P.B., Margelidon-Cozzolino V., Catella-Chatron J., Ayoub E., Guichard J.B., Murgier M., et al. What's next after the clot? Residual pulmonary vascular obstruction after pulmonary embolism: from imaging finding to clinical consequences. Thromb Res. 2019;184:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2019.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wartski M., Collignon M.-A. Incomplete recovery of lung perfusion after 3 months in patients with acute pulmonary embolism treated with antithrombotic agents. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1043–1048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goërtz Y.M.J., Herck M.V., Delbressine J.M., Vaes A.W., Meys R., Machado F.V.C., et al. Persistent symptoms 3 months after a SARS-CoV-2 infection: the post-COVID-19 syndrome? ERJ Open Res [Internet] European Respiratory Society. 2020 doi: 10.1183/23120541.00542-2020. [cited 2020 Sep 26] Available from: https://openres.ersjournals.com/content/early/2020/09/01/23120541.00542-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]