Abstract

Stem cells hold indefinite self-renewable capability that can be differentiated into all desired cell types. Based on their plasticity potential, they are divided into totipotent (morula stage cells), pluripotent (embryonic stem cells), multipotent (hematopoietic stem cells, multipotent adult progenitor stem cells, and mesenchymal stem cells [MSCs]), and unipotent (progenitor cells that differentiate into a single lineage) cells. Though bone marrow is the primary source of multipotent stem cells in adults, other tissues such as adipose tissues, placenta, amniotic fluid, umbilical cord blood, periodontal ligament, and dental pulp also harbor stem cells that can be used for regenerative therapy. In addition, induced pluripotent stem cells also exhibit fundamental properties of self-renewal and differentiation into specialized cells, and thus could be another source for regenerative medicine. Several diseases including neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular diseases, autoimmune diseases, virus infection (also coronavirus disease 2019) have limited success with conventional medicine, and stem cell transplantation is assumed to be the best therapy to treat these disorders. Importantly, MSCs, are by far the best for regenerative medicine due to their limited immune modulation and adequate tissue repair. Moreover, MSCs have the potential to migrate towards the damaged area, which is regulated by various factors and signaling processes. Recent studies have shown that extracellular calcium (Ca2+) promotes the proliferation of MSCs, and thus can assist in transplantation therapy. Ca2+ signaling is a highly adaptable intracellular signal that contains several components such as cell-surface receptors, Ca2+ channels/pumps/exchangers, Ca2+ buffers, and Ca2+ sensors, which together are essential for the appropriate functioning of stem cells and thus modulate their proliferative and regenerative capacity, which will be discussed in this review.

Keywords: Ca2+ signaling, Ca2+ channels, Transient receptor potential channel 1/Orai1 stem cells, Regenerative medicine, Stem cells

Core Tip: Regenerative medicine has the potential to replace damaged tissues. Stem cells provide new hope for regenerative therapy as they have indefinite self-renewable capability and can differentiate into all cell types. Stem cells can be obtained from both exogenous and endogenous sources. Moreover, stem cells migrate towards the damaged organs; however, signaling molecules/factors that allow them to move to damaged organs and facilitate repair have not been fully identified. Ca2+ signaling is critical for appropriate functioning of stem cells. Importantly, Ca2+ signaling is highly adaptable, and how it modulates stem cell function and its regenerative capacity is discussed in this article.

INTRODUCTION

Stem cells are unique, undifferentiated cells that possess two fundamental properties, indefinite self-renewable capability and differentiation capability into all types of cell lineages. These two stem cell traits make them special, and thus, they can be used for organ development or tissue therapy[1,2]. Self-renewal capability primarily means that cells have the ability to maintain an undifferentiated state, while undergoing multiple cell divisions. Similarly, differentiation capability or plasticity/potency of stem cells means that the cells have the capability to differentiate into different cell lineages. Thus, understanding the factors that make them proliferative as well identifying the niches/signaling events that allow them to develop into unique cell lineages is essential for their use in regenerative therapy. Based on their source, stem cells can be broadly divided into two types: “embryonic stem cells” (ESCs) and “non-embryonic adult/somatic stem cells”[3]. However, stem cells can also be named according to their origin and plasticity such as embryonic, germinal, and somatic (fetal or adult) stem cells. Furthermore, based on their differentiating potential, stem cells are also classified into totipotent, pluripotent, and multipotent cell types[4].

ESCs

After fertilization, the zygote divides into multiple cells, which are called the morula stage, and these individual cells are named totipotent cells. Totipotent cells exhibit a very high self-renewal capacity along with a similarly high differentiation potential into multiple lineages. These cells further grow, mature, divide, and develop into a blastocyst. Cells of the blastocyst’s inner cell mass are more specialized cells and thus are referred to as ESCs or pluripotent stem cells. ESCs have a unique property and can differentiate into all three germ layers that develop all potential organs with endless dividing potential, which makes them perfect for regenerative therapy. Although ethical concerns prevent them from being used for regenerative therapy, extraembryonic tissues or placental cells also have self-renewing capacity that maintains an undifferentiated state similar to that observed in ESCs, and thus are also a great source of non-ESCs[3,5-7]. However, these cells are in limited quantity and are sometimes contaminated with other cells, making them hard to be used for regenerative therapy.

Non-embryonic adult/somatic cells

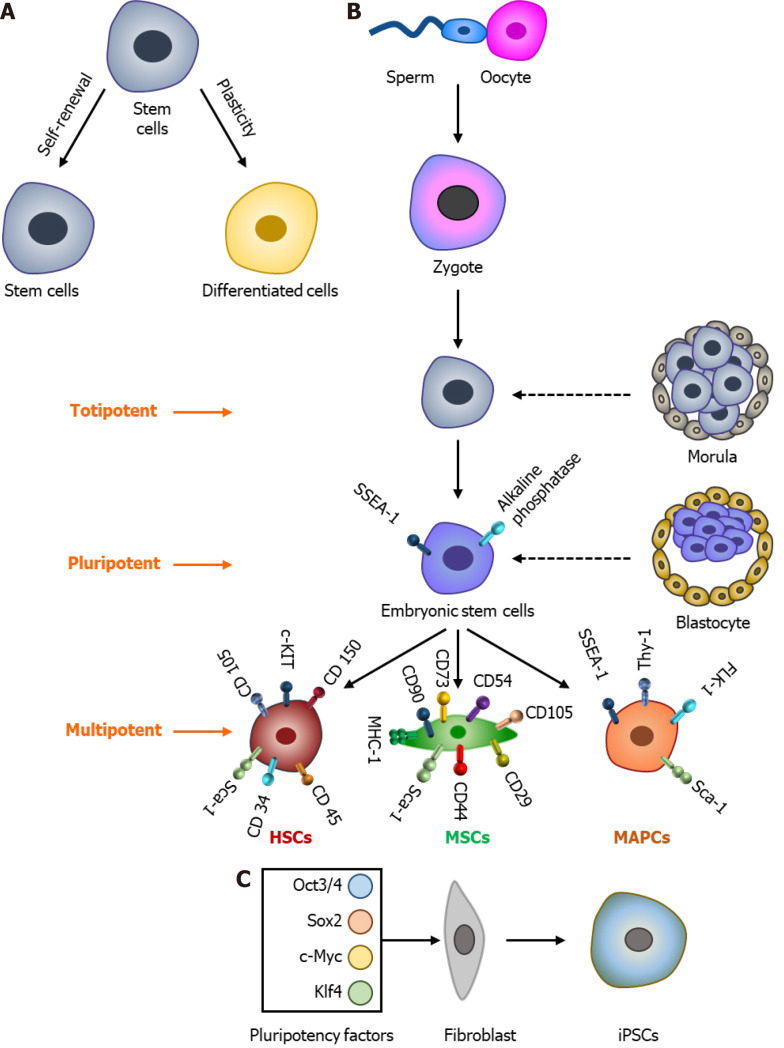

Pluripotent stem cells can generate into multipotent stem cells, which are more “mature” cells but have restricted ability to differentiate into specialized cells. Multipotent stem cells are already committed to lineage-specific differentiation, and thus have minimal plasticity potential. These can be isolated from a variety of tissue sources[3,6] as described below and shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Stem cell properties and their types. A: Stem cells have two unique fundamental properties, self-renewal, and differentiation potential; B: Showing the development of different stem cells such as embryonic stem cells, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and multipotent adult progenitor stem cells (MAPCs); C: Showing the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from mouse fibroblast cells using four factors (octamer-binding transcription factor 3/4, SRY-box transcription factor 2, c-Myc, Kruppel-like factor 4). SSEAs: Stage-specific embryonic antigens.

Bone marrow and bone marrow stem cells: Bone marrow niches are structurally organized in the medullary cavity and are protected within the bones. Importantly, bone cells serve as skeletal support for hematopoietic cells (HPCs) along with serving as calcium (Ca2+) reservoirs. The mammalian bone marrow is an organ of the immune system, which is the largest semisolid organ of the human body. Bone marrow exists in the medullary cavity and epiphysis of the long bones such as humeri, ribs, femora, tibia, pelvis, and skull. It constitutes a soft gelatinous and dynamic tissue, which varies from person to person in its structure, quantity, and quality[8-10]. Bone marrow contains both soluble and cellular parts that change within the person over time. The soluble part is made up of cytokines, growth factors, chemokines, hormones, and various ions. The cellular portion comprises different cell types such as adipocyte, macrophage, fibroblast, osteoblast, and stem cells[11]. Importantly, bone marrow is the largest reservoir of non-ESCs that contains hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and multipotent adult progenitor stem cells (MAPCs). The hematopoietic region of the bone marrow contains HSCs and HPCs, whereas the vascular component contains non-HPCs such as MSCs and MAPCs[12]. Stem cells are not distributed randomly within the bone marrow; instead, they are highly organized and constitute the bone marrow microenvironment or niche where cells are protected and work in a synchronized manner[10,11].

HSCs

HSCs are essential for making different types of blood cells and are present in specialized areas of bone marrow referred to as the “the primary hematopoiesis site"[13]. Hematopoiesis is a dynamic process that maintains homeostasis between the production and consumption of all terminally differentiated blood cells[14]. HSCs produce myeloid progenitor cells, which can be differentiated into granulocytes, monocytes, erythrocytes, platelets, and lymphoid progenitor cells, which further differentiate into lymphocytes and plasma cells. HSCs express specific surface markers such as stem cell antigen-1 (Sca-1), c-kit, cluster of differentiation 34 (CD34), Thy-1, CD201, and CD105/endoglin, whereas human HSCs express c-Kit, Sca-1, Thy-1, and CD133. Additional markers for individual cells are indicated in Table 1[15].

Table 1.

Stem cells and their phenotypic markers and transcription factors

|

Embryonic stem cells (expression of SM/TF)

| ||

| Human | Positive SM | SSEA-3, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), CD9, Thy1, HLA-I CD133, and CD326[92-94] |

| Negative SM | SSEA-1[92-94] | |

| TF | Oct 3/4, Sox2, Nanog, activin/nodal, FGF, Esrrb, and Tfcp2l1, Klf4, Klf2, Tbx3, and Gbx2[92,94,95] | |

| Mouse | Positive SM | SSEA-1 and alkaline phosphatase[92,94] |

| Negative SM | SSEA-3, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, and TRA-1-81[92,94] | |

| TF | Oct-3/4, Sox2, Nanog, LIF, BMP, genesis, germ cell nuclear factor, GDF-3, FGF-4, UTF1, Fbx15, and Sall4[92,94,96] | |

| Hematopoietic stem cells (expression of SM/TF) | ||

| Human | Positive SM | CD34, CD90, CD49R, and CD133[7,97,98] |

| Negative SM | Lin, CD38, and CD45RA[7,97,98] | |

| TF | AHR, BMI1, GFI1, HES1, HLF, Runx-1, Scl/tal-1, Lmo-2, MII, Tel, and GATA-2[97,99] | |

| Mouse | Positive SM | Sca-1, c-kit, CD49b, CD150, (endoglin), and Slamf1[7,97,100] |

| Negative SM | Lin, FLT3, CD34, CD41, Flk2, and CD48[7,97,100] | |

| TF | Runx-1, Scl/tal-1, Lmo-2, MII, Tel, Bmi-1, Gfi-1, and GATA-2[99,101] | |

| Multipotent stem cells (expression of SM/TF) | ||

| Human | Positive SM | CD146, CD44, CD13, CD73, CD90, CD105, and MHC class I[18,102] |

| Negative SM | CD34, CD45, c-kit, KDR, CD56, CD271, CD140a, CD140b, and ALP[18,102] | |

| TF | Oct-4 Rex-1, Nanog, and BmI-1[102,103] | |

| Mouse | Positive SM | c-Kit, CD9, CD13, CD31, SSEA-1, and Sca-1[17,104] |

| Negative SM | CD3, CD19, CD34, CD44, CD45, c-Kit Thy1, Flk-1MHC-I, MHC class II, Gr-1, and Mac-1[17,104] | |

| TF | Oct-4, Rex-1, and Nanog[16,102] | |

| Mesenchymal stem cells (expression of SM/TF) | ||

| Human | Positive SM | CD10, CD13, CD29, CD44, CD49e (a5-integrin), CD54 (intercellular adhesion molecule [ICAM]-1), CD58, CD71, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD140a, CD140b, CD146, CD166 (activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule), CD271, Sca-1, ALP MHC class I, vimentin, cytokeratin (CK) 8, CK-18, and nestin[18,27-29] |

| Negative SM | CD4, CD8, CD11a, CD11b, CD14, CD15, CD16, CD19, CD25, CD31, CD33, CD34, CD45, CD49b, CD49d, CD49f, CD50, CD56, CD62E, CD62L, CD62P, CD79a, CD80, CD86, CD106 (vascular cell adhesion molecule [VCAM]-1), CD117, CD271, c-kit, KDR, HLA-DR, cadherin V, and glycophorin A[18,27-29] | |

| TF | Oct-4, Rex-1, and Sox-2[105] | |

| Mouse | Positive SM | CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, and Sca-1, Thy1.2, and CD135[10,23,24,26,28] |

| Negative SM | CD11b, CD14, CD31, CD34, CD45, and CD86, CD135, c-Kit, and VCAM-1[10,23,24,26,28] | |

| TF | HOX, stage-specific embryonic antigen 1 (SSEA-1), Nanog, Oct-4, Rex-1, and GATA-4[25] | |

SM: Surface marker; TF: Transcription factor.

MAPCs

MAPCs were first isolated from rat bone marrow by Dr. Verfaillie’s group in 2002. Rodent bone marrow-derived MAPCs can differentiate into endothelial cells, adipocytes, chondrocytes, and osteocytes[16]. Rat MAPCs express c-Kit+, CD9+, CD13+, CD31+ but are negative for CD44, major histocompatibility complex class I, CD45, and Thy1 surface markers[17], while human MAPCs exhibit higher expression of CD44, CD13, CD73, and CD90. MAPCs also have immunomodulatory properties and show higher expression of pluripotency factors such as octamer-binding transcription protein 4 (Oct4), SRY-box transcription factor 7 (Sox7), Sox17, Rex-1, GATA binding protein 4 (GATA4), and GATA6 and thus are used for tissue regeneration (Table 1)[18].

MSCs

Friedenstein’s group first discovered adult bone marrow-derived MSCs in 1968[19] but Caplan gave the term ‘mesenchymal stem cell’[20]. Bone marrow is considered the primary source of MSCs; however, MSCs have extensive localization such as in adipose tissue, placenta, amniotic fluid, umbilical cord blood, umbilical cord, periodontal ligament, and dental pulp[19,21,22]. MSCs regulate and maintain stemness, proliferation, and differentiation (such as into adipocytes, osteocytes, chondrocytes, and other cells), and are essential for the self-renewal of HSCs and their progenitor cells[11]. As per the Mesenchymal and Tissue Stem Cell Committee of the International Society of Cellular Therapy guideline, the minimal criteria for MSC characterization include plastic adherent property and spindle-shaped morphology, along with the expression of MSC-positive markers such as CD29 (b1-integrin), CD44, and Sca-1, and negative for markers such as CD11b, CD34, and CD45 (Table 1). In addition, they should have a tri-lineage differentiation such as adipocytes, osteocytes, and chondrocytes and cells, those satisfy these criteria are thus called “MSCs,” and those that do not, are termed “multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells”[10,11,23-28]. Human MSCs must also be positive for certain surface markers and must be negative for specific surface markers as indicated in Table 1[29].

Very small embryonic-like stem cells

Another type of pluripotent stem cell that is present in multiple tissues, including bone marrow, cord blood, and gonads, are proposed as very small embryonic-like (VSEL) stem cells[30]. Kucia et al[31] in Ratajczak et al[32] first reported VSEL stem cells in adult mice bone marrow. Later, VSELs were found in various organs such as the human cord and peripheral blood. VSEL stem cells show multiple characteristics of ESCs, including differentiating ability into all three germ layers[30]. In addition, VSEL stem cells are the most primitive stem cells that migrate to the gonadal ridges during development and further relocate to all developing organs and survive throughout life[33].

Induced pluripotent stem cells

Although different types of stem cells are used in biomedical and clinical research, one of the challenges that remain is that they are not in sufficient quantity. In addition, they are not from the same individual and are thus considered foreign, thereby having immunological issues[34]. To overcome these issues, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have come to light in recent years that can not only solve the ethical issues related to the use of ESCs but can also be developed from the same individual and thus can be a safer alternative. In 2006, Takahashi and Yamanaka[35] were able to generate iPSCs directly from mouse fibroblast using four critical factors, Oct3/4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Kruppel-like factor 4 (Klf4)[35,36]. Similarly, another group showed that four factors that include Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, and Lin28 were also essential to generate iPSCs from human somatic cells. Importantly, generated iPSCs exhibited essential characteristics like ESCs such as normal karyotypes, telomerase activity, cell surface markers, and maintaining the developmental potential that also has differentiation potential[36,37]. Importantly, as a proof of concept, iPSCs are used to treat sickle cell anemia using mouse models that show its importance for therapeutic usage. However, more research is needed to understand the key signaling changes due to overexpression of these transcription factors as they can lead to uncontrolled growth. Cost as well as time to develop these stem cells are also issues and moreover, as several factors and animal products are used to grow these cells, they hinder its use for regenerative medicine.

Stem cells and issues for using them for regenerative medicine: Stem cells are critical for the repair, replacement, and regeneration of damaged tissues that are able to restore organ function. Stem cells can act as regenerative medicine as they are valuable sources of new cells to treat various degenerative/aging, autoimmune and genetic disorders[38]. The rapid expansion of stem cell research and stem cell product commercialization has also created numerous ethical issues. The killing of embryos to obtain stem cells or create human ESC lines is considered the primary cause of controversy[39-41]. iPSCs provide an essential tool for stem cell therapy, but they are not ideal. Although the destruction of embryos is not required to generate iPSCs as they are obtained from somatic cells' reprogramming, they come with their own issues. Insertion of multiple copies of the retroviral vectors is needed to generate iPSCs from skin fibroblast cells, which can easily cause mutations and thus could be harmful. In addition, one of the four genes, c-Myc, is a proto-oncogene and can be oncogenic based on certain conditions and can induce tumors. Also, studies have revealed that 1 in 5000-10000 transfected cells became iPSCs, i.e. only specific cells have the potential to be reprogrammed into iPSCs. Thus, iPSCs may not be the ultimate candidate for transplantation therapy[42]. Also, other ethical concerns remain if human iPSCs could be used in the generation of the embryo, germ cells, human clones[43]. Thus, in spite of the recent development, additional research is needed to overcome some of these issues. Although various factors and signaling mechanisms are required for self-renewal and differentiation of stem cells, explaining all of them is beyond this review. Therefore, in this review, we will focus on essential and significantly less noticed factors, such as Ca2+ and other divalent cations Ca2+ signaling, and Ca2+ channels in stem cell functions and regulation.

CA2+ AND INTRACELLULAR CA2+ STORAGE

Ca2+ is the most crucial element in cells as it is an important intracellular secondary messenger. Evolution has utilized Ca2+ to bind to various biological macromolecules, which makes it unique that is able to effectively regulate the concentration of free Ca2+[44]. Ca2+ modulates a diversity of cellular functions such as transcription, apoptosis, cytoskeletal rearrangement, immune response, growth, proliferation and differentiation, maintenance of pluripotency, and self-renewal of stem cells[45]. Ca2+ is a highly adaptable intracellular signal, and depending on the source, a Ca2+ signal may lead to opposing functions such as proliferation and cell death. Another important aspect of Ca2+ signaling is that it can trigger the response in microseconds (exocytosis at synaptic endings), to milliseconds (as observed in muscle contraction), and in minutes to hours (gene transcription and cell proliferation)[46]. One way it can control such diverse function is by modulating the spatial and temporal Ca2+ signals, which could be highly localized or widespread. Cells store intracellular Ca2+ in various organelles such as the Golgi apparatus, mitochondria, nucleus, lysosomes, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER). These individual Ca2+ stores are essential in modulating different functions, mechanism(s), and for the exchange of ions with other Ca2+ pools. For example, Ca2+ in the sarcoplasmic reticulum act as a rapidly mobilizable reservoir, mitochondrial Ca2+ is a crucial dynamic regulator of metabolism, and trans-Golgi network Ca2+ store is involved in the formation of secretory granules[47]. Furthermore, different intracellular organelles release sequestered Ca2+ using various Ca2+ mobilizing messengers and receptors such as ER use inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)-IP3 receptor and cADPR-ryanodine receptors (RyRs) while acidic endosomes and lysosomes use nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) and two-pore channels (TPCs) channels[48] that modulate various cellular functions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Calcium signaling toolkit

|

Component of toolkit

|

Name of calcium signaling toolkit components

|

| Cell-surface receptors | G protein-coupled receptors and protein tyrosine kinase receptors such as muscarinic, bradykinin B2, cholecystokinin, α, β-adrenergic, P2X and P2Y, angiotensin II, Ca2+-sensing receptor, chemokine, metabotrophic glutamate, serotonin, oxytocin, epidermal growth factor receptor, and platelet-derived growth factor[46,106,107] |

| Calcium channels | Voltage-gated channels (Cav1.1 to 1.4 [L-type], Cav2.1 to 2.3 [N-, P/Q- and R-type] and Cav3.1 to 3.3 [T-type]) and two-pore channels (TPCs)[46], voltage-gated K+ channel, Ca2+-activated K+ channel, ATP-sensitive K+ channels, TRPC1-7 ORAI1-3, IP3R, and RyR2[108-110] |

| Calcium pumps and exchangers | Na+/Ca2+ exchangers, Na+/Ca2+-K+ exchangers, plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) and sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) pumps[46,111] |

| Calcium buffers (Ca2+-binding proteins) | Cytoplasmic buffers (PV [parvalbumin], CB [calbindin D-28k], and calretinin)[112] and buffers in lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (calsequestrin, calreticulin, glucose-regulated protein [GRP] 78 and GRP94), ERp72, and mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU), Golgi buffers (Cab45, CALNUC P54/NEFA[46,113], troponin C, myosin, calmodulin, and sarcolemma (cellular buffers in myocytes)[114] |

| Calcium sensors | EF-hand (CaM, TnC, calpains, miro1-2, S100A1-14, S100B, S100C, S100P, NCS-1, hippocalcin, neurocalcin, recoverin, VILIP1-3, GCAP1-3, MICU1 etc.) or C2 Ca2+-binding domains (annexin 1-13, otoferin, protein kinase C, RASAL etc.)[46], ER Ca2+ sensors STIM1 and STIM2[115] |

Ca2+ signaling and Ca2+ channel in stem cells/MSCs

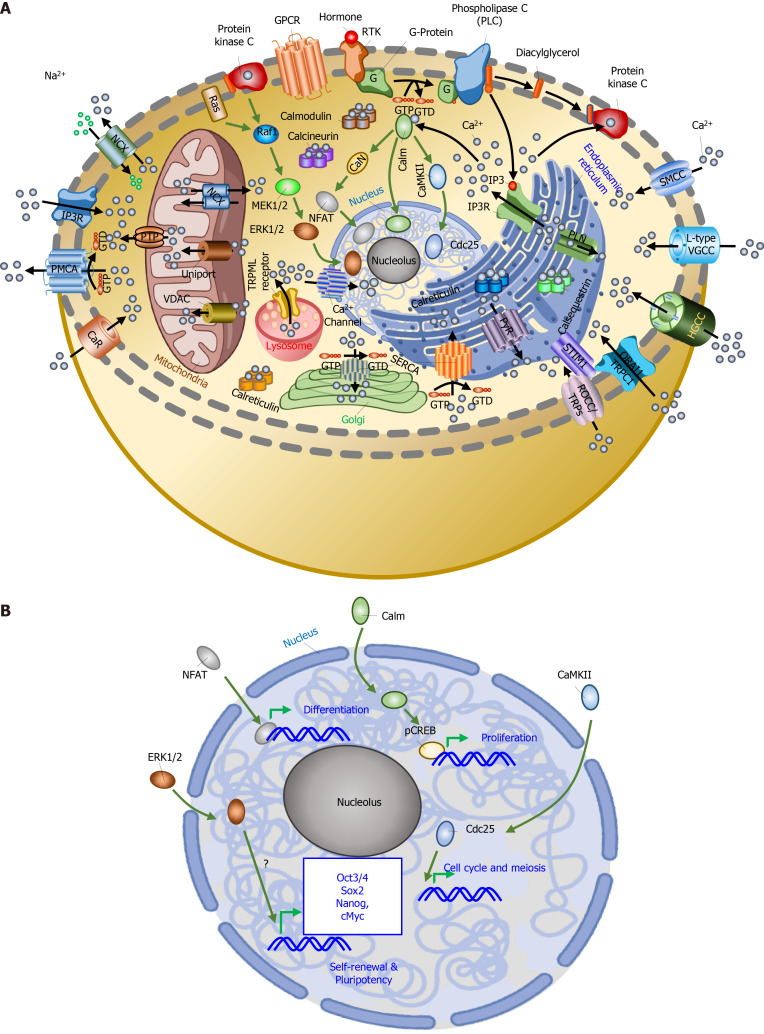

Ca2+ signaling is associated with several components. In a typical Ca2+ signaling process, changes in the intracellular Ca2+ stores start several counteracting processes, which may be “on” or “off”, which depends on if the intracellular Ca2+ concentration is increasing or decreasing. At physiological or “resting” state, cytosolic Ca2+ concentration is maintained between 100 and 300 nmol/L range, which favors the “off” processes. However, when the cells are stimulated by different stimuli such as hormonal and mechanical forces, cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration is increased to 50-100 µmol/L that represents the “on” processes[49]. Binding of the agonist activates the cell surface receptor that generates downstream signals to activate the phospholipase C (PLC)-IP3 signal transduction cascade, which begins by the opening of intracellular receptors, IP3 receptors (IP3Rs) for the cytoplasmic influx of Ca2+. Increased intracellular Ca2+ binds to different cytoplasmic proteins such as calmodulin, protein kinase C (PKC), 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), calcineurin, and others that participate in Ca2+ signaling pathways. At the cellular level, cells use two crucial Ca2+ sources for generating intracellular downstream signals. First is the internal reservoir, where Ca2+ is released and second is the external sources, that includes the entry of extracellular Ca2+ into the cells through various plasma membrane channels (Table 2 and Figure 2A)[50,51].

Figure 2.

Calcium toolkit and calcium signaling. A: Calcium (Ca2+) signaling toolkit components include cell-surface receptors (G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and protein tyrosine kinase receptors), Ca2+ channels (voltage-gated channels and two-pore channels, voltage-gated K+ channel, Ca2+-activated K+ channel, ATP-sensitive K+ channels, TRPC1-7 ORAI1-3, IP3R, RyR2), Ca2+ pumps and exchangers (Na+/Ca2+ exchangers (NCX), Na+/Ca2+-K+ exchangers, plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA) and sarco-endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ ATPase), Ca2+ buffers (parvalbumin, calbindin, and calretinin [cytoplasmic buffers] and Ca2+ buffers of the ER lumen, calsequestrin, calreticulin, glucose-regulated protein [GRP] 78 and GRP94), Ca2+ sensors (EF-hand [CaM, TnC, calpains, NCS-1, hippocalcin, neurocalcin, recoverin, MICU1, etc.] or C2 Ca2+-binding domains [annexin 1-13, otoferin, protein kinase C, RASAL, etc.], ER Ca2+ sensors STIM1 and STIM2), and Ca2+-sensitive cellular process. In a typical Ca2+-sensitive cellular process, the hormone binds to a specific receptor. This binding causes GDP-GTP exchange on the G protein. G protein (GTP-bound) activates phospholipase C (PLC). Activated PLC breaks phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol. IP3 moves to a specific receptor on the ER, binds with the receptor, and triggers the release of sequestered Ca2+. Released Ca2+ and diacylglycerol activate protein kinase C enzyme. Activated protein kinase C phosphorylates cellular proteins and activates downstream proteins (Raf1 and other proteins). Activated Raf1 binds and activates MEK1/2 and MEK1/2, which phosphorylate extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2. ERK1/2 enters the nucleus and on/off the genes against the hormone response. The released Ca2+ decreases ER calcium level. Low Ca2+ of ER sense by ER Ca2+ sensor (STIM) and activate it. An activated Ca2+ sensor binds the Ca2+ channel protein (ORAI) on the plasma membrane, opens the Ca2+ channel, and allows the Ca2+ entry into the cytoplasm from extracellular space. This process is called store-operated Ca2+ entry; B: Activated transcription factors and other proteins bind to DNA and increase the gene expression for self-renewal, proliferation, and differentiation processes in the stem cells. CaR: Ca2+ receptor; CREB: cAMP response element-binding protein; IP3R: Inositol trisphosphate receptor; NFAT: Nuclear factor of activated T-cells; VDAC: Voltage-dependent anion channel; VGCC: Voltage-gated Ca2+ channel.

In stem cells, extracellular Ca2+ influx into the cytoplasm is mediated mainly by store-operated Ca2+ channels (SOCCs) rather than the voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) or by the Na+/Ca2+ exchangers. Also, ER Ca2+ release is mediated by IP3Rs rather than the RyRs and Ca2+ is moved back by sarco-ER Ca2+ ATPase, which is located on the ER membrane in mouse pluripotent stem cells[52]. Like embryonic stems, human MSCs also showed that discharge of Ca2+ was mediated by IP3Rs, and extracellular Ca2+ entry through the plasma membrane was mainly mediated by the SOCCs. This study showed that store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) is the leading player in stem cell proliferation instead of VGCCs[53]; however, the molecular identity of the SOCE channel is still not clear. Stimuli activated cells use different Ca2+ channels such as VGCCs, SOCE via the transient receptor potential (TRP) channels (TRPCs)/Orai’s, and purinergic receptors that are essential for Ca2+ diffusion. Several studies showed an essential role for VGCCs in tissue development, such as cartilage development and inactivation or inhibition of VGCCs in stem cells resulted in imperfect chondrogenesis, suggesting that VGCC might have a critical role in differentiation. Moreover, Members of the TRP channel superfamily also showed their involvement in chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs by activating the Sox9 pathway[51].

MSCs do express the L-type VGCCs and decreases in Cav1.1 expression are able to lower the immune response[54]. Blocking VGCCs by dihydropyridines (DHPs) can suppress the proliferation of immune cells and both DHPs and cyclosporine are frequently used in transplantation patients. Another investigation confirmed that L-type VGCCs of skin-derived MSCs are involved in autocrine interleukin (IL)-6-mediated cell migration. Importantly, patch-clamp experiments showed that 15% of human undifferentiated bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) express functional L-type VGCCs. Moreover, blockade of L-type VGCCs by nifedipine suppressed the proliferation of rat BMSCs by downregulating bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-2 expression, which is an essential inducer of osteoblast differentiation[55]. Furthermore, Ca2+ also plays an essential role in osteoclast formation. HSCs lineage-generated osteoclasts possess different types of Ca2+ channels and receptors. Osteoclast precursors express IP3R2, while mature osteoclasts express the IP3R1 isoform and cytokine stimulation promotes osteoclast differentiation. Accumulated activities of these receptors initiate intracellular Ca2+ signals and modulate bone turnover[56]. Thus, Ca2+ channels are involved in the differentiation of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Differentiated osteoblasts and osteoclasts are involved in the modeling and remodeling process resulting in new bone tissue regeneration or bone formation[13]. Moreover, considering the potential role of Ca2+ channels in stem cell function, it offers the hope of tissue engineering and tissue regeneration in the future. However, one of the main caveats that remains is that these stem cells are not excitable and thus it is not clear how these VGCCs are activated; therefore, more research is needed to fully establish their role.

ROLE OF CA2+ AND CA2+ CHANNELS IN THE VARIOUS CELLULAR PROCESS OF STEM CELLS/MSCS

Proliferation and self-renewal of stem cells

Studies have shown that Ca2+ mobilization plays a crucial role in the self-renewal and proliferation of stem cells by activating or inhibiting different Ca2+ channels. Previous studies on the cell cycle of progenitor and undifferentiated cells have shown that transient Ca2+ oscillation, maintained by Ca2+ stores, increases the levels of cell cycle regulators such as cyclins A and E and plays a crucial role during the G1 to S transition. IP3Rs and L-type channels (in differentiated cells) and ryanodine-sensitive stores (in neural progenitor cells) maintain the Ca2+ oscillations. This study suggests that Ca2+ oscillation is involved in cell cycle progression and proliferation[57]. Also, mouse ESC (mESC) proliferation is stimulated by epidermal growth factor via the phosphorylation of connexin 43 (involved in the influx of Ca2+ and translocation of PKC) and downstream activation of p44/42, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (Figure 2B). Moreover, gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptors can modulate the proliferation of mESCs by regulating intracellular Ca2+. Furthermore, the expansion of ESCs is also regulated by ligands such as ATP (adenosine triphosphate) and lysophosphatidic acid, which activate the PLC/PKC/IP3 pathway by triggering a release of Ca2+[52].

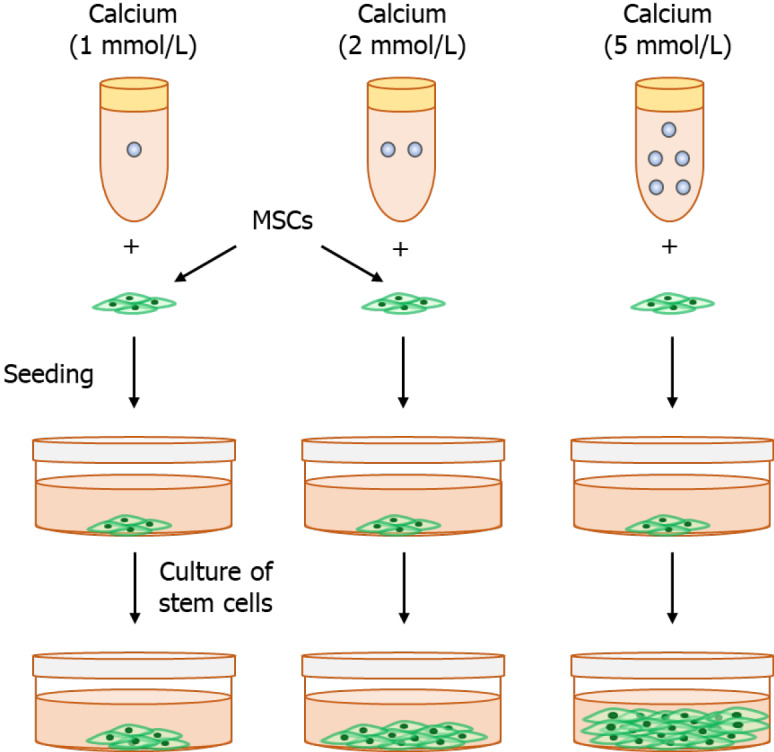

Previous research has shown that SOCCs are important for Ca2+ influx in mESCs. SOCCs blockers (e.g., 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate [2-APB] and SKF-96365) reduce mESC proliferation, suggesting that SOCE is essential for ESC proliferation[58]. Similarly, SKF-96365 and 2-APB (SOCE inhibitors) treatment decreases the expansion of murine bone marrow-HSCs, human bone marrow, and umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells[59]. Moreover, 2-APB downregulates pluripotent markers (Sox-2, Klf-4, and Nanog), which suggests that SOCE is associated with the self-renewal property of mESCs (Figure 2B). Furthermore, estrogen enhances the proliferation of stem cells via enhancing SOCE; however, the molecular identity of the channel has not yet been identified. The nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) is involved in estrogen-stimulated proliferation, indicating that NFAT is the downstream target of estrogen-induced SOCE. This study showed how estrogen (a female sex hormone) affects ESC proliferation[58] (Figure 3). Another study showed that extracellular Ca2+ promotes the proliferation and migration of MSCs[60]. Our unpublished research on MSCs also shows that extracellular Ca2+ promotes proliferation and SOCE blockers (e.g., 2-APB and SKF-96365) reduce MSC proliferation, suggesting that SOCE is essential for MSC proliferation.

Figure 3.

Calcium-dependent stem cell proliferation. Stem cells cultured in 1, 2, and 5 mmol/L calcium. Our results (not published) reveal that higher calcium-treated stem cells show a high proliferation rate. MSCs: Mesenchymal stem cells.

Differentiation: Stem cells can generate any tissue cells by modulating the differentiation process. Previous research has shown that Ca2+ directly upregulates the catalytic activity of protein arginine methyltransferase 1 and enhances methylation. Increased methylation stimulates differentiation suggesting that Ca2+ plays a crucial role during erythroid differentiation[61]. Ca2+ provokes a signaling cascade in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells and promotes MSC osteogenic differentiation[62]. Also, physical stimuli activates the Ca2+ channel that results in increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration, leading to the chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs[51]. Ca2+-activated potassium channels also play a crucial role in MSC differentiation[63]. Similarly, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in mESCs plays a crucial role during ESC differentiation into cardiomyocytes[64]. Studies have shown that L-VGCCs play an essential role in maintaining intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in differentiating cells[65]. Ca2+ also plays a significant role in the neuronal differentiation process. A previous study suggested that the TPCs and NAADP-regulated Ca2+ channels play an essential role in the neural differentiation of mESCs. mESCs showed decreased expression of TPC2 during differentiation into neural progenitors at an early stage while gradually increasing again during the late stages of neural differentiation. TPC2 knockdown disrupts Ca2+ signaling and inhibits differentiation[48,66]. Another study suggested that TPCs and NAADP-regulated Ca2+ channels play essential roles in myogenesis differentiation. Ca2+ is critical in regulating the transcription factors that promote differentiation. For instance, Ca2+ signal transducer such as Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase and calcineurin regulate transcription factors, such as cAMP response element binding protein and NFAT, which activate the transcription of myogenin, a key regulator of muscle cell differentiation. Impairment of intracellular Ca2+ signaling inhibits muscle differentiation. These studies suggest the critical role of Ca2+ signaling and Ca2+ channels in cellular differentiation. Furthermore, the HPC and osteoclast differentiation process involves ADP-ribosyl cyclase CD38, which is associated with the generation of NAADP and cADPR. Thus, these studies suggest the critical role of Ca2+ signaling and Ca2+ channels in cellular differentiation[48].

The differentiation process is regulated by several biological and chemical factors, including steroid hormones, BMPs, BMP-2, BMP-4, BMP-7, (crucial for chondrogenesis differentiation and synthesis of aggrecan, collagen type 2, and other extracellular matrices proteins) and tumor growth factors-β (TGF-β), TGF-β1, and TGF-β3[67]. In many of these processes, Ca2+ plays a crucial role, e.g., the higher intracellular Ca2+ influx through Ca2+ channels and modulates the cell differentiation process. Several studies have shown that the inhibition of Ca2+ channels, VGCCs in stem cells, inhibits chondrogenesis. Therefore, activation of these Ca2+ channels in the stem cells opens a new research area, leading to innovative approaches to improve MSC self-renewal and differentiation potentials such as chondrogenic differentiation and cartilage repair of MSCs[51].

Adhesion, migration, and homing: Cytosolic Ca2+, a primary second messenger, regulates various cellular functions including cell migration. Temporal cytosolic Ca2+ is mediated by receptors such as G protein-coupled P2Y receptors and ligand-gated ion channel P2X receptors. P2X receptors mediate extracellular Ca2+ influx while P2Y receptors trigger the release of intracellular Ca2+ from the ER and reduce the ER Ca2+ level, which activates SOCE. These receptors perform an essential role in the migration process via ATP-induced regulation[68]. MSCs are found in the connective tissue that surrounds other tissues and organs. During injury and damage, MSCs migrate or homing to the damaged tissues or lesions, differentiation into desired cell types, and play a crucial role in normal tissue morphogenesis, homeostasis, and repair. The homing process begins with the interactions between MSCs and the vascular endothelium at the target tissue[25]. Adhesive MSCs migrate in the mesenchymal mode from the healthy tissue area to the damaged area. MSC migration, a complex and highly coordinated process, has several steps (e.g., rear-to-front polarization, protrusion, adhesion formation, and rear retraction) managed by various proteins as integrin, tensin, paxillin, actin, and myosin. Furthermore, these proteins are controlled by multiple signaling molecules, such as Rho GTPase, Rho kinase, focal adhesion kinase (FAK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), PKC, MAPK, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)[68]. A previous study showed that electromagnetic fields exposure increases intracellular Ca2+, which in turn initiates migratory signaling (FAK/Rho GTPase). Increasing MSC migration towards injury or diseases might be a novel way to improve the efficiency of MSC engraftment in clinical applications[69].

CA2+ AND CA2+ CHANNEL-ASSOCIATED DISEASES

Spatial and temporal Ca2+ concentrations are necessary for various Ca2+ signaling systems for the specific cellular functions of different cell types. The ER releases Ca2+ through IP3Rs, which activate various Ca2+ signaling systems. Ca2+ signaling systems are highly controlled and regulated for normal function. Dysregulation of Ca2+ signaling is linked to significant human diseases such as bipolar disorder, cardiac disease, and Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer's disease (AD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Mucolipidosis type IV, Niemann-Pick disease, and bone disease[46,70-72]. Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space, maintained by Ca2+ release-activated channels (CRAC), also participates in various cellular functions. CRAC channels are composed of two components: ORAI1 proteins (ion-conducting pore-forming component) located in the plasma membrane, and stromal interaction molecule (STIM) 1 and 2 (Ca2+ sensor and activator of ORAI1 channels) located in the ER. Alteration of ORAI1 and STIM1 function abolish CRAC channel function and SOCE, resulting in several diseases such as severe combined immunodeficiency-like disease, autoimmunity, muscular hypotonia, and ectodermal dysplasia. In addition, deformity in dental enamel formation and tooth development have been observed[73].

Ca2+ channels are the main signaling elements in neurons and interact with other modulatory proteins, resulting in modulation of Ca2+-sensing. Ca2+ channels regulate the release of bioactive molecules such as proteins, hormones, and neurotransmitters. Such Ca2+-sensing is required for many biophysical and pharmacological properties in neurons. Deformed Ca2+ channel activity contributes to disease progression[74]. Studies have shown that Ca2+ channels such as voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and glutamate receptor channels are mainly responsible for Ca2+ influx into the neuron. SOCE, a Ca2+ flow into cells mediated by depleted ER Ca2+ stores, with the help of STIM protein such as STIM1 and STIM2. Dysregulation of neuronal SOCE and glutamate receptors promotes acute neurodegenerative diseases such as traumatic brain injury and cerebral ischemia, and chronic neurodegenerative disorders such as AD and Huntington's disease[75,76].

STEM CELLS IN DISEASE CONDITIONS

Preclinical studies have shown the great potential of stem cells for tissue engineering and considerable promise to rebuild damaged tissue such as bone, cartilage, marrow stroma, muscle, fat, and other connective tissues, which mark them an attractive option in tissue engineering, disease, cell therapy, and regenerative medicine[77,78]. Autologous and allogeneic transplantations of stem cells have shown promise for the treatment of various diseases such as Crohn’s disease, graft vs host disease, refractory systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, and systemic sclerosis, etc. (Table 3)[79].

Table 3.

Stem cell transplantation therapy in disease

|

SCT

|

SCT therapy in preclinical condition

|

| BMCs | Myelofibrosis[116] |

| HSCs | Fanconi anemia[117], chronic granulomatous disease[118], and Friedreich's ataxia[119] |

| MAPCs | Myocardial infarction[120], and neonatal hypoxic-ischemic injury[121] |

| MSCs | Musculoskeletal disease[122], spinal cord injury[123], liver fibrosis[124], idiopathic pneumonia syndrome[125], Alzheimer’s disease[126], and Parkinson's disease[127] |

| SCT therapy in clinical condition | |

| BMCs | Post-myocardial infarction[128], and sickle cell diseases[129] |

| HSCs | Sickle cell disease[130], human cytomegalovirus infection[131], childhood acute t-lymphoblastic leukemia[132], ankylosing spondylitis autoimmune disease[133], Crohn's disease[134], SARS-CoV-2[135], refractory lupus nephritis[136], Pemphigus disease[137], Richter syndrome[138] |

| MAPCs | Parkinson’s disease[139] |

| MSCs | Graft vs host disease[140], diabetes mellitus type 2[86], spinal cord injury[141], SARS-CoV-2[142], multiple sclerosis[143], systemic lupus erythematous[144] |

BMCs: Bone marrow cells; HSCs: Hematopoietic stem cells; MAPCs: Multipotent adult progenitor stem cells; MSCs: Mesenchymal stem cells; SARS-CoV-2: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SCT: Stem cell transplantation.

Stem cells and their progeny cells secrete soluble factors including cytokines, growth factors, hormones, Ca2+, and chemokines. These factors are required for the proper functioning of bone marrow. For instance, MSCs and other cells such as osteoblasts and CAR cells secret stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), a critical chemokine necessary for the supporting and homing of HSCs in the HSC niche[11]. Moreover, stem cells generated growth factors, recruit MSCs for lineage-specific differentiation, ensure proper modeling and remodeling, and promote bone tissue regeneration[80]. MSCs also produce other important secretory trophic factors such as angiopoietin-1, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, erythropoietin, fibroblast growth factor (FGF-1/2/4/7/9), glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor, granulocyte/ macrophage-colony stimulating factor (G/M-CSF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1/2), leukemia inhibitory factor, nerve growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, SDF-1, secreted frizzled-related protein 2, stanniocalcin 1, TGF-β1/2/3, and vascular endothelial growth factor. These factors support engraftment and modulate tissue development, maintenance, repair of diseased tissues, and self-healing and exert regenerative effects. Interestingly, studies showed that MSCs secrete different trophic factors that modulate their function[81].

The fundamental immunomodulatory mechanisms of MSCs and how MSCs modulate the immune response remains to be fully investigated. However, some research has noted that the immunomodulatory capacity of MSCs is of two types: first, cell-to-cell contact-dependent, and second is an independent mechanism that do not involve contact. In cell-to-cell contact-dependent mechanisms, MSCs directly suppress and modulate the generation of various pro-inflammatory immune cells such as inhibition of natural killer (NK) cells, activated B cell, and dendritic cells and strongly suppress CD4+ T helper cells and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. On the other hand, MSCs promote the production of immune-suppressive regulatory cells such as dendritic regulatory cells, B regulatory cells, CD4+ regulatory cells (Tregs), and NK regulatory cells. These regulatory cells actively suppress the immune response in the repair area and build a favorable and tolerogenic microenvironment for tissue repair and regeneration[11,28]. Importantly, Ca2+ especially Orai1/STIM1 plays a critical role in modulating the immune response and although it is not clear if they also contribute towards the immunomodulatory mechanism of stem cells, more research is needed to fully establish this.

Independent mechanisms on the other hand involve MSCs secretome. MSCs secrete both the soluble anti-inflammatory factors and pro-inflammatory factors[19]. Anti-inflammatory factors including chemokines, cytokines, and hormones such as M-CSF, monocyte chemotactic protein 1, ILs (IL1, IL2, IL6, IL10, and IL13), HGF, intracellular adhesion molecule 1 indoleamine, 2,3-dioxygenase, human leukocyte antigen, prostaglandin E2, and TGF-β[11,19,25,82] are secreted from MSCs. Although pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL1β, IL6, IL8, and IL9 are also secreted by MSCs, the balance between these anti- and pro-inflammatory cytokines are essential for regeneration of the damaged tissue area[19]. MSCs differentiate themselves to provide the comprehensive types of the body cells such as cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes, fibroblasts, and neural cells, chondroblasts, chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and osteocytes and have shown their potential in bone regeneration and other tissue regeneration[78,83]. Although bone has the unique capacity to regenerate and repair itself, bone regeneration is improved when stem cells are used. Although osteoblasts and multipotent cells are available as sources of bone regeneration, exogenous stem cells secrete bioactive molecules that regulate the behavior of osteoblasts and resident MSCs. Importantly, for large and significant skeletal defects, stem cell/MSCs are cultured or seeded on a suitable scaffold/carrier that modulate bone growth. Thus, bone tissue engineering is significant for bone regeneration, especially with trauma or tumor resection defect[84]. Implants (stem cell/scaffold) used in bone tissue engineering have shown good implant integration results, no late fractures, and long-term durability. Successful tissue engineering depends on several important factors including biocompatibility, scaffold chemistry/ surface properties, porosity, pore size, scaffold surface architecture, osteoinductivity of scaffold and cell number, passage of cells, physiological and developmental “state” of seeded MSCs[85]. Osteoblasts are already committed to bone lineage with a limited number of divisions and differentiate into osteocytes that maintain structural bone integrity. Importantly, osteoclasts can also be generated from monocytes and macrophage lineage of HSCs[13]. Osteoblasts communicate with HSCs through various signaling, including Notch signaling, Bmp-1/Bmp-1 receptor signaling, parathyroid/parathyroid receptor signaling, and Wnt-catenin signaling that has Ca2+ signaling as the few determinants. Osteoblasts secrete various factors, including G-CSF, angiopoietin, and osteopontin. These factors involve regulating HSC activity and expansion and maintenance of the microenvironment for specific functioning of stem cells. HSC and osteoblast cell populations constitute the osteohematopoietic niche, also known as the osteoblastic niche or endosteal nice, which maintains the proliferation, migration, quiescence, and specific functioning of HSCs[11]. MSC characteristics, comprising self-renewal, multipotency, differentiation properties, availability, immunomodulatory properties, and little ethical concern make them a potential candidate for regenerative medicine[21,78,86].

CONCLUSION

Future aspect (MSCs and coronavirus disease 2019)

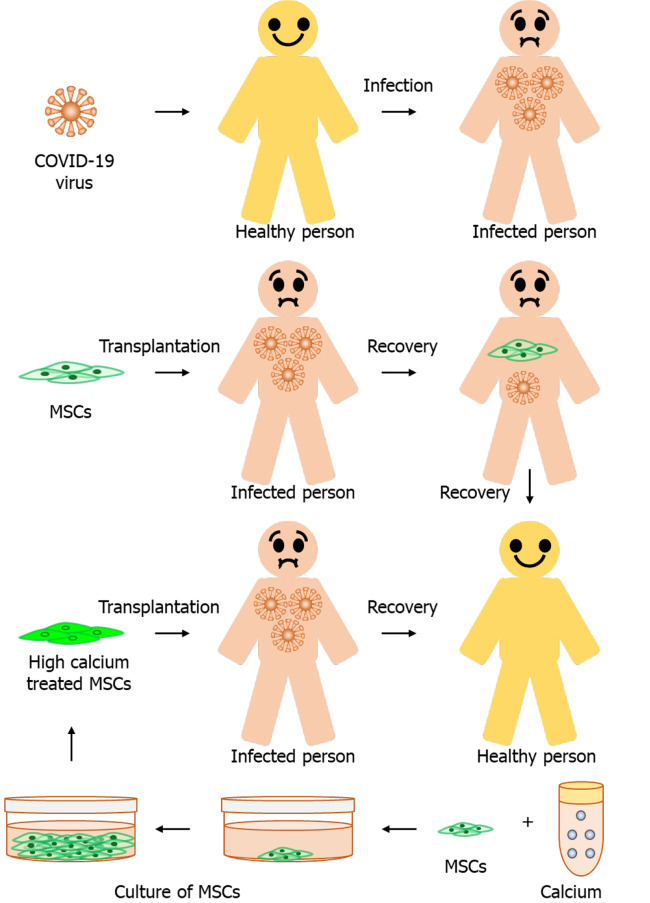

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a new global public health concern. This disease is caused by the novel coronavirus or severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)[87]. Coronavirus, a positive-stranded RNA virus, uses surface spike protein (has two important subunit S1 and S2) for binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors on the host cell surface and mediate its entry into the host cells. S1 subunit mediates the attachment, and the S2 subunit is responsible for membrane fusion and internalization of the virus. Lungs, having alveolar epithelial cells, are most affected by the SARS-CoV-2 infection because these cells have a high propensity of ACE2 receptors. The SARS-CoV-2 disease generates pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines storm, which cause severe inflammation. Inflammation is the driving power that leads to coronavirus infections such as severe shock, and multiple organ failure results in acute respiratory distress syndrome[88,89]. Another study showed that COVID-19 patients (mild to severe) showed low serum Ca2+. Low serum Ca2+ indicates that Ca2+-balance is the primary target of COVID-19. Ca2+ balance, a biomarker of clinical severity, is associated with virus-associated multiple organ injuries, and an increase in inflammatory cytokines[90]. Ca2+ channel blockers, also called antihypertensive drugs such as ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers, inhibited the post-entry replication events of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. In clinics, antihypertensive medications (along with chloroquine) are widely used to treat the Coronavirus disease. This study showed that Ca2+ is very crucial for the Coronavirus infection[87].

MSCs could be a solution for COVID-19 because MSCs transplantation generates tissue regenerative favorable microenvironment and inhibits the immune response activated by virus infection by modulating immune cells and the production of regulatory cells. MSCs also express several interferon-stimulated genes, ISGs (interferon induced transmembrane family), SAT1, IFI6, PMAIP1, ISG15, CCL2, p21/CDKN1) against viral infection. Apart from immunomodulatory properties, MSCs can be isolated from various sources, stored for future use, and have a less ethical concern. Since MSCs did not show any adverse side effects on the patient. Thus, MSCs could be a regenerative medicine for life-threatening diseases. Transplantation of MSCs into COVID-19 patients was studied in China that showed some promise in the treatment of COVID-19, but it is not recommended in other countries. Moreover, to date, MSCs used in 17 clinical studies and 70 trials have shown positive results in treating respiratory disorders. Since MSCs did not show any adverse side effects on the patient. Thus, MSCs could be a regenerative medicine for life-threatening diseases[88,91] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 patient. We hypothesize that calcium-treated mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a better option to counter the coronavirus’s inflammatory storm response, treat the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patient, and other deadly diseases.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: January 19, 2021

First decision: February 13, 2021

Article in press: March 29, 2021

Specialty type: Cell and tissue engineering

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Goswami C, Yue J S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

Contributor Information

Nassem Ahamad, School of Dentistry, UT Health Science Center San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78257, United States.

Brij B Singh, School of Dentistry, UT Health Science Center San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78257, United States. singhbb@uthscsa.edu.

References

- 1.Bishop AE, Buttery LD, Polak JM. Embryonic stem cells. J Pathol. 2002;197:424–429. doi: 10.1002/path.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lerou PH, Daley GQ. Therapeutic potential of embryonic stem cells. Blood Rev. 2005;19:321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menon S, Shailendra S, Renda A, Longaker M, Quarto N. An Overview of Direct Somatic Reprogramming: The Ins and Outs of iPSCs. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17 doi: 10.3390/ijms17010141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choumerianou DM, Dimitriou H, Kalmanti M. Stem cells: promises vs limitations. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14:53–60. doi: 10.1089/teb.2007.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nichols J. Introducing embryonic stem cells. Curr Biol. 2001;11:R503–R505. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagers AJ, Weissman IL. Plasticity of adult stem cells. Cell. 2004;116:639–648. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seita J, Weissman IL. Hematopoietic stem cell: self-renewal vs differentiation. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2010;2:640–653. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Travlos GS. Normal structure, function, and histology of the bone marrow. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34:548–565. doi: 10.1080/01926230600939856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy DT, Moynagh MR, Eustace SJ, Kavanagh EC. Bone marrow. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2010;18:727–735. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahamad N, Rath PC. Expression of interferon regulatory factors (IRF-1 and IRF-2) during radiation-induced damage and regeneration of bone marrow by transplantation in mouse. Mol Biol Rep. 2019;46:551–567. doi: 10.1007/s11033-018-4508-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pleyer L, Valent P, Greil R. Mesenchymal Stem and Progenitor Cells in Normal and Dysplastic Hematopoiesis-Masters of Survival and Clonality? Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17 doi: 10.3390/ijms17071009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao E, Xu H, Wang L, Kryczek I, Wu K, Hu Y, Wang G, Zou W. Bone marrow and the control of immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2012;9:11–19. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2011.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao X, Zhang C, Cui X, Liang Y. Interactions of Hematopoietic Stem Cells with Bone Marrow Niche. Methods Mol Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/7651_2020_298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovtonyuk LV, Fritsch K, Feng X, Manz MG, Takizawa H. Inflamm-Aging of Hematopoiesis, Hematopoietic Stem Cells, and the Bone Marrow Microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2016;7:502. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wognum AW, Eaves AC, Thomas TE. Identification and isolation of hematopoietic stem cells. Arch Med Res. 2003;34:461–475. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reyes M, Li S, Foraker J, Kimura E, Chamberlain JS. Donor origin of multipotent adult progenitor cells in radiation chimeras. Blood. 2005;106:3646–3649. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sohni A, Verfaillie CM. Multipotent adult progenitor cells. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2011;24:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs SA, Roobrouck VD, Verfaillie CM, Van Gool SW. Immunological characteristics of human mesenchymal stem cells and multipotent adult progenitor cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2013;91:32–39. doi: 10.1038/icb.2012.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vizoso FJ, Eiro N, Cid S, Schneider J, Perez-Fernandez R. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome: Toward Cell-Free Therapeutic Strategies in Regenerative Medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18 doi: 10.3390/ijms18091852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson A, Webster A, Genever P. Nomenclature and heterogeneity: consequences for the use of mesenchymal stem cells in regenerative medicine. Regen Med. 2019;14:595–611. doi: 10.2217/rme-2018-0145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding DC, Shyu WC, Lin SZ. Mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:5–14. doi: 10.3727/096368910X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trohatou O, Roubelakis MG. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells in Regenerative Medicine: Past, Present, and Future. Cell Reprogram. 2017;19:217–224. doi: 10.1089/cell.2016.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soleimani M, Nadri S. A protocol for isolation and culture of mesenchymal stem cells from mouse bone marrow. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu H, Guo ZK, Jiang XX, Li H, Wang XY, Yao HY, Zhang Y, Mao N. A protocol for isolation and culture of mesenchymal stem cells from mouse compact bone. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:550–560. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kariminekoo S, Movassaghpour A, Rahimzadeh A, Talebi M, Shamsasenjan K, Akbarzadeh A. Implications of mesenchymal stem cells in regenerative medicine. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2016;44:749–757. doi: 10.3109/21691401.2015.1129620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, Deans R, Keating A, Prockop Dj, Horwitz E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruedigam C, Driel Mv, Koedam M, Peppel Jv, van der Eerden BC, Eijken M, van Leeuwen JP. Basic techniques in human mesenchymal stem cell cultures: differentiation into osteogenic and adipogenic lineages, genetic perturbations, and phenotypic analyses. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol 2011; Chapter 1: Unit1H. 3 doi: 10.1002/9780470151808.sc01h03s17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han Y, Li X, Zhang Y, Han Y, Chang F, Ding J. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Regenerative Medicine. Cells. 2019;8 doi: 10.3390/cells8080886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel DM, Shah J, Srivastava AS. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells in regenerative medicine. Stem Cells Int. 2013;2013:496218. doi: 10.1155/2013/496218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Helw M, Chelvarajan L, Abo-Aly M, Soliman M, Milburn G, Conger AL, Campbell K, Ratajczak MZ, Abdel-Latif A. Identification of Human Very Small Embryonic like Stem Cells (VSELS) in Human Heart Tissue Among Young and Old Individuals. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2020;16:181–185. doi: 10.1007/s12015-019-09923-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kucia MJ, Wysoczynski M, Wu W, Zuba-Surma EK, Ratajczak J, Ratajczak MZ. Evidence that very small embryonic-like stem cells are mobilized into peripheral blood. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2083–2092. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ratajczak MZ, Zuba-Surma EK, Machalinski B, Ratajczak J, Kucia M. Very small embryonic-like (VSEL) stem cells: purification from adult organs, characterization, and biological significance. Stem Cell Rev. 2008;4:89–99. doi: 10.1007/s12015-008-9018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhartiya D, Shaikh A, Anand S, Patel H, Kapoor S, Sriraman K, Parte S, Unni S. Endogenous, very small embryonic-like stem cells: critical review, therapeutic potential and a look ahead. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;23:41–76. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmw030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanley J, Rastegarlari G, Nathwani AC. An introduction to induced pluripotent stem cells. Br J Haematol. 2010;151:16–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seki T, Fukuda K. Methods of induced pluripotent stem cells for clinical application. World J Stem Cells. 2015;7:116–125. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v7.i1.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Volarevic V, Markovic BS, Gazdic M, Volarevic A, Jovicic N, Arsenijevic N, Armstrong L, Djonov V, Lako M, Stojkovic M. Ethical and Safety Issues of Stem Cell-Based Therapy. Int J Med Sci. 2018;15:36–45. doi: 10.7150/ijms.21666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caulfield T, Kamenova K, Ogbogu U, Zarzeczny A, Baltz J, Benjaminy S, Cassar PA, Clark M, Isasi R, Knoppers B, Knowles L, Korbutt G, Lavery JV, Lomax GP, Master Z, McDonald M, Preto N, Toews M. Research ethics and stem cells: Is it time to re-think current approaches to oversight? EMBO Rep. 2015;16:2–6. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kastenberg ZJ, Odorico JS. Alternative sources of pluripotency: science, ethics, and stem cells. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 2008;22:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson RE. Ethics of embryonic stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1687–90; author reply 1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Solomon LM, Brockman-Lee SA. Embryonic stem cells in science and medicine, part II: law, ethics, and the continuing need for dialogue. Gend Med. 2008;5:3–9. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(08)80003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng YL. Some Ethical Concerns About Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Sci Eng Ethics. 2016;22:1277–1284. doi: 10.1007/s11948-015-9693-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brini M, Ottolini D, Calì T, Carafoli E. Calcium in health and disease. Met Ions Life Sci. 2013;13:81–137. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ermakov A, Daks A, Fedorova O, Shuvalov O, Barlev NA. Ca2+ -depended signaling pathways regulate self-renewal and pluripotency of stem cells. Cell Biol Int. 2018;42:1086–1096. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berridge MJ. Calcium signalling remodelling and disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40:297–309. doi: 10.1042/BST20110766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pozzan T, Rizzuto R, Volpe P, Meldolesi J. Molecular and cellular physiology of intracellular calcium stores. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:595–636. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.3.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parrington J, Tunn R. Ca(2+) signals, NAADP and two-pore channels: role in cellular differentiation. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2014;211:285–296. doi: 10.1111/apha.12298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dutta D. Mechanism of store-operated calcium entry. J Biosci. 2000;25:397–404. doi: 10.1007/BF02703793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uzieliene I, Bernotas P, Mobasheri A, Bernotiene E. The Role of Physical Stimuli on Calcium Channels in Chondrogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19 doi: 10.3390/ijms19102998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hao B, Webb SE, Miller AL, Yue J. The role of Ca(2+) signaling on the self-renewal and neural differentiation of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) Cell Calcium. 2016;59:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kawano S, Shoji S, Ichinose S, Yamagata K, Tagami M, Hiraoka M. Characterization of Ca(2+) signaling pathways in human mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Calcium. 2002;32:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0143416002001240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davenport B, Li Y, Heizer JW, Schmitz C, Perraud AL. Signature Channels of Excitability no More: L-Type Channels in Immune Cells. Front Immunol. 2015;6:375. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tan YZ, Fei DD, He XN, Dai JM, Xu RC, Xu XY, Wu JJ, Li B. L-type voltage-gated calcium channels in stem cells and tissue engineering. Cell Prolif. 2019;52:e12623. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robinson LJ, Blair HC, Barnett JB, Zaidi M, Huang CL. Regulation of bone turnover by calcium-regulated calcium channels. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1192:351–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Resende RR, Adhikari A, da Costa JL, Lorençon E, Ladeira MS, Guatimosim S, Kihara AH, Ladeira LO. Influence of spontaneous calcium events on cell-cycle progression in embryonal carcinoma and adult stem cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:246–260. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wong CK, So WY, Law SK, Leung FP, Yau KL, Yao X, Huang Y, Li X, Tsang SY. Estrogen controls embryonic stem cell proliferation via store-operated calcium entry and the nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:2519–2530. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Uslu M, Albayrak E, Kocabaş F. Temporal modulation of calcium sensing in hematopoietic stem cells is crucial for proper stem cell expansion and engraftment. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:9644–9666. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee MN, Hwang HS, Oh SH, Roshanzadeh A, Kim JW, Song JH, Kim ES, Koh JT. Elevated extracellular calcium ions promote proliferation and migration of mesenchymal stem cells via increasing osteopontin expression. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50:1–16. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0170-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu MY, Hua WK, Chiou YY, Chen CJ, Yao CL, Lai YT, Lin CH, Lin WJ. Calcium-dependent methylation by PRMT1 promotes erythroid differentiation through the p38α MAPK pathway. FEBS Lett. 2020;594:301–316. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barradas AM, Fernandes HA, Groen N, Chai YC, Schrooten J, van de Peppel J, van Leeuwen JP, van Blitterswijk CA, de Boer J. A calcium-induced signaling cascade leading to osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3205–3215. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pchelintseva E, Djamgoz MBA. Mesenchymal stem cell differentiation: Control by calcium-activated potassium channels. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:3755–3768. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Otsu K, Kuruma A, Yanagida E, Shoji S, Inoue T, Hirayama Y, Uematsu H, Hara Y, Kawano S. Na+/K+ ATPase and its functional coupling with Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in mouse embryonic stem cells during differentiation into cardiomyocytes. Cell Calcium. 2005;37:137–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wen L, Wang Y, Wang H, Kong L, Zhang L, Chen X, Ding Y. L-type calcium channels play a crucial role in the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;424:439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.06.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang ZH, Lu YY, Yue J. Two pore channel 2 differentially modulates neural differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Danišovič L, Varga I, Polák S. Growth factors and chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Cell. 2012;44:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jiang LH, Mousawi F, Yang X, Roger S. ATP-induced Ca2+-signalling mechanisms in the regulation of mesenchymal stem cell migration. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74:3697–3710. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2545-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang Y, Yan J, Xu H, Yang Y, Li W, Wu H, Liu C. Extremely low frequency electromagnetic fields promote mesenchymal stem cell migration by increasing intracellular Ca2+ and activating the FAK/Rho GTPases signaling pathways in vitro. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:143. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0883-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Santoni G, Maggi F, Amantini C, Marinelli O, Nabissi M, Morelli MB. Pathophysiological Role of Transient Receptor Potential Mucolipin Channel 1 in Calcium-Mediated Stress-Induced Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Physiol. 2020;11:251. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schrank S, Barrington N, Stutzmann GE. Calcium-Handling Defects and Neurodegenerative Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2020;12 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a035212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Blair HC, Schlesinger PH, Huang CL, Zaidi M. Calcium signalling and calcium transport in bone disease. Subcell Biochem. 2007;45:539–562. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6191-2_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lacruz RS, Feske S. Diseases caused by mutations in ORAI1 and STIM1. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1356:45–79. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leandrou E, Emmanouilidou E, Vekrellis K. Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels and α-Synuclein: Implications in Parkinson's Disease. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:237. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Singh BB, Liu X, Ambudkar IS. Expression of truncated transient receptor potential protein 1alpha (Trp1alpha): evidence that the Trp1 C terminus modulates store-operated Ca2+ entry. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36483–36486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000529200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Serwach K, Gruszczynska-Biegala J. STIM Proteins and Glutamate Receptors in Neurons: Role in Neuronal Physiology and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20 doi: 10.3390/ijms20092289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang J, Chen Z, Sun M, Xu H, Gao Y, Liu J, Li M. Characterization and therapeutic applications of mesenchymal stem cells for regenerative medicine. Tissue Cell. 2020;64:101330. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2020.101330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tavakoli S, Ghaderi Jafarbeigloo HR, Shariati A, Jahangiryan A, Jadidi F, Jadidi Kouhbanani MA, Hassanzadeh A, Zamani M, Javidi K, Naimi A. Mesenchymal stromal cells; a new horizon in regenerative medicine. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:9185–9210. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Figueroa FE, Carrión F, Villanueva S, Khoury M. Mesenchymal stem cell treatment for autoimmune diseases: a critical review. Biol Res. 2012;45:269–277. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602012000300008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gordeladze JO, Reseland JE, Duroux-Richard I, Apparailly F, Jorgensen C. From stem cells to bone: phenotype acquisition, stabilization, and tissue engineering in animal models. ILAR J. 2009;51:42–61. doi: 10.1093/ilar.51.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schäfer R, Spohn G, Baer PC. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells in Regenerative Medicine: Can Preconditioning Strategies Improve Therapeutic Efficacy? Transfus Med Hemother. 2016;43:256–267. doi: 10.1159/000447458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shammaa R, El-Kadiry AE, Abusarah J, Rafei M. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Beyond Regenerative Medicine. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:72. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pipino C, Pandolfi A. Osteogenic differentiation of amniotic fluid mesenchymal stromal cells and their bone regeneration potential. World J Stem Cells. 2015;7:681–690. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v7.i4.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rose FR, Oreffo RO. Bone tissue engineering: hope vs hype. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;292:1–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Salgado AJ, Coutinho OP, Reis RL. Bone tissue engineering: state of the art and future trends. Macromol Biosci. 2004;4:743–765. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200400026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moreira A, Kahlenberg S, Hornsby P. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells for diabetes. J Mol Endocrinol. 2017;59:R109–R120. doi: 10.1530/JME-17-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang LK, Sun Y, Zeng H, Wang Q, Jiang X, Shang WJ, Wu Y, Li S, Zhang YL, Hao ZN, Chen H, Jin R, Liu W, Li H, Peng K, Xiao G. Calcium channel blocker amlodipine besylate therapy is associated with reduced case fatality rate of COVID-19 patients with hypertension. Cell Discov. 2020;6:96. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-00235-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rajarshi K, Chatterjee A, Ray S. Combating COVID-19 with mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Biotechnol Rep (Amst) 2020;26:e00467. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2020.e00467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shafiee A, Moradi L, Lim M, Brown J. Coronavirus disease 2019: A tissue engineering and regenerative medicine perspective. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2021;10:27–38. doi: 10.1002/sctm.20-0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhou X, Chen D, Wang L, Zhao Y, Wei L, Chen Z, Yang B. Low serum calcium: a new, important indicator of COVID-19 patients from mild/moderate to severe/critical. Biosci Rep. 2020 doi: 10.1042/BSR20202690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yao D, Ye H, Huo Z, Wu L, Wei S. Mesenchymal stem cell research progress for the treatment of COVID-19. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520955063. doi: 10.1177/0300060520955063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nagano K, Yoshida Y, Isobe T. Cell surface biomarkers of embryonic stem cells. Proteomics. 2008;8:4025–4035. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sundberg M, Jansson L, Ketolainen J, Pihlajamäki H, Suuronen R, Skottman H, Inzunza J, Hovatta O, Narkilahti S. CD marker expression profiles of human embryonic stem cells and their neural derivatives, determined using flow-cytometric analysis, reveal a novel CD marker for exclusion of pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 2009;2:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pera MF, Reubinoff B, Trounson A. Human embryonic stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2000;113 (Pt1):5–10. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Deb KD, Jayaprakash AD, Sharma V, Totey S. Embryonic stem cells: from markers to market. Rejuvenation Res. 2008;11:19–37. doi: 10.1089/rej.2007.0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Martello G, Smith A. The nature of embryonic stem cells. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:647–675. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Doulatov S, Notta F, Laurenti E, Dick JE. Hematopoiesis: a human perspective. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:120–136. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Attar A. Changes in the cell surface markers during normal hematopoiesis: A guide to cell isolation. Biology . 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 99.Orkin SH, Zon LI. Hematopoiesis: an evolving paradigm for stem cell biology. Cell. 2008;132:631–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ema H, Morita Y, Yamazaki S, Matsubara A, Seita J, Tadokoro Y, Kondo H, Takano H, Nakauchi H. Adult mouse hematopoietic stem cells: purification and single-cell assays. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2979–2987. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cheng H, Zheng Z, Cheng T. New paradigms on hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Protein Cell. 2020;11:34–44. doi: 10.1007/s13238-019-0633-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Roobrouck VD, Vanuytsel K, Verfaillie CM. Concise review: culture mediated changes in fate and/or potency of stem cells. Stem Cells. 2011;29:583–589. doi: 10.1002/stem.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sagrinati C, Netti GS, Mazzinghi B, Lazzeri E, Liotta F, Frosali F, Ronconi E, Meini C, Gacci M, Squecco R, Carini M, Gesualdo L, Francini F, Maggi E, Annunziato F, Lasagni L, Serio M, Romagnani S, Romagnani P. Isolation and characterization of multipotent progenitor cells from the Bowman's capsule of adult human kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2443–2456. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, Schwartz RE, Keene CD, Ortiz-Gonzalez XR, Reyes M, Lenvik T, Lund T, Blackstad M, Du J, Aldrich S, Lisberg A, Low WC, Largaespada DA, Verfaillie CM. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 2002;418:41–49. doi: 10.1038/nature00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Izadpanah R, Trygg C, Patel B, Kriedt C, Dufour J, Gimble JM, Bunnell BA. Biologic properties of mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow and adipose tissue. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:1285–1297. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kroeze WK, Sheffler DJ, Roth BL. G-protein-coupled receptors at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4867–4869. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2010;141:1117–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bollimuntha S, Selvaraj S, Singh BB. Emerging roles of canonical TRP channels in neuronal function. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;704:573–593. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0265-3_31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pani B, Bollimuntha S, Singh BB. The TR (i)P to Ca²⁺ signaling just got STIMy: an update on STIM1 activated TRPC channels. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012;17:805–823. doi: 10.2741/3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Karlstad J, Sun Y, Singh BB. Ca(2+) signaling: an outlook on the characterization of Ca(2+) channels and their importance in cellular functions. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;740:143–157. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-2888-2_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Guerini D. The Ca2+ pumps and the Na+/Ca2+ exchangers. Biometals. 1998;11:319–330. doi: 10.1023/a:1009210001608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fairless R, Williams SK, Diem R. Calcium-Binding Proteins as Determinants of Central Nervous System Neuronal Vulnerability to Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20 doi: 10.3390/ijms20092146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Prins D, Michalak M. Organellar calcium buffers. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Smith GL, Eisner DA. Calcium Buffering in the Heart in Health and Disease. Circulation. 2019;139:2358–2371. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.039329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sun Y, Da Conceicao VN, Ahamad N, Madesh M, Singh BB. Spatial localization of soce channels and its modulators regulate neuronal physiology and contributes to pathology. Curr Opin Physiol . 2020;17:50–62. [Google Scholar]