Abstract

Gastric cancer (GC) patients develop malignant ascites as the disease progresses owing to peritoneal metastasis. GC patients with malignant ascites have a rapidly deteriorating clinical course with short survival following the onset of malignant ascites. Better optimized treatment strategies for this subset of patients are needed. To define the cellular characteristics of malignant ascites of GC, we used single-cell RNA sequencing to characterize tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) from four samples of malignant ascites and one sample of cerebrospinal fluid. Reference transcriptomes for M1 and M2 macrophages were generated by in vitro differentiation of healthy blood-derived monocytes and applied to assess the inflammatory properties of TAMs. We analyzed 180 cells, including tumor cells, macrophages, and mesothelial cells. Dynamic exchange of tumor-promoting signals, including the CCL3–CCR1 or IL1B–IL1R2 interactions, suggests macrophage recruitment and anti-inflammatory tuning by tumor cells. By comparing these data with reference transcriptomes for M1-type and M2-type macrophages, we found noninflammatory characteristics in macrophages recovered from the malignant ascites of GC. Using public datasets, we demonstrated that the single-cell transcriptome-driven M2-specific signature was associated with poor prognosis in GC. Our data indicate that the anti-inflammatory characteristics of TAMs are controlled by tumor cells and present implications for treatment strategies for GC patients in which combination treatment targeting cancer cells and macrophages may have a reciprocal synergistic effect.

Subject terms: Gastric cancer, RNA sequencing, Cancer genomics

Gastric cancer: Understanding cellular interactions suggests potential treatments

New strategies for treating advanced gastric cancer could emerge from insights into the interactions between white blood cells called macrophages and tumor cells in fluid known as malignant ascites that accumulates in the abdomen. Researchers in Seoul, South Korea, led by Hae-Ock Lee at The Catholic University of Korea and Woong-Yang Park at the Samsung Medical Center compared macrophages from healthy subjects with those from gastric cancer ascites. They identified molecular signaling interactions between tumor cells and macrophages that recruited macrophages into the ascites and converted them into more anti-inflammatory forms. The macrophages were then able to promote the activities of the cancer cells. The results suggest that chemicals able to inhibit or deplete proteins now identified as involved in controlling these synergistic interactions could become a new class of therapeutic agents.

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is a highly heterogeneous disease in histopathological, molecular and clinical aspects. To uncover the heterogeneity and to broaden the molecular understanding of cancers, comprehensive genomic characterizations have been performed throughout various cancers. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) analysis reported four molecular subtypes of GC: chromosomal instability (CIN), microsatellite instability-high (MSI), genomically stable (GS), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)1. However, the clinical significance of these subtypes needs to be elucidated.

The Asian Cancer Research Group (ACRG) reported four GC molecular subtypes that are associated with recurrence pattern and prognosis: microsatellite-stable (MSS)/TP53−, MSS/TP53+, MSI, and MSS/epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). GC patients with the MSS/EMT subtype showed significantly more frequent recurrence, a higher rate of peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) at recurrence, a younger age at presentation, and poorer survival than patients in other subtypes2. The response to systemic chemotherapy in GC patients with PC is poor, and the presence of PC is an independent poor prognostic factor in advanced GC (AGC)3.

While immune checkpoint blockade showed excellent clinical response in MSI and EBV subtypes, GC patients with the EMT subtype did not benefit from immune checkpoint blockade4,5. We reported that GC patients with the mesenchymal subtype showed a poor response to pembrolizumab despite an increased immune signature4. EMT mediates resistance to immunotherapies by recruiting immunosuppressive macrophages and neutrophils (M2 macrophages and myeloid-derived suppressor cells) such that blocking the immune checkpoint axis is not sufficient to restore antitumor immunity6.

Recent studies investigating the tumor microenvironment with single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technology identified that macrophages in tumors exhibited a distinct state or spectrum, which is more complex than the classical binary M1/M2 model7–9. Comprehensive intercellular interactions between tumor cells and immune cells were investigated by analyzing receptor and ligand expression through scRNA-seq10. However, few studies have characterized the immunosuppressive niche in the ascites of GC patients.

In the current study, we used scRNA-seq to explore heterogeneity and functional interactions in both immune cells and tumor cells in ascites of GC patients. Using the microfluidic C1 system, we captured tumor cells and macrophages in malignant ascites. Tumor-specific gene expression profiling revealed patient-specific as well as heterogeneous gene expression signatures for stemness, EMT, and molecular-targeted therapies. Most macrophages manifested an alternatively activated ‘M2’ phenotype, which seems to be influenced by the metastatic sites as well as associated tumor types. Overall, our data demonstrate the aggressive characteristics of peritoneal GC cells in terms of their potential for stimulating growth and shaping a tumorigenic microenvironment.

Materials and methods

Preparation of cells from patient-derived specimens

All patients and healthy donors in this study agreed to provide biospecimens through a consent form approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center (ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier: NCT#0229964811 and Institutional Review Board nos. 2016-04-107 and 2017-04-038).

Five samples were collected from four patients diagnosed with metastatic GC. We obtained four peritoneal ascites samples and one cerebrospinal fluid (AGC04CSF) sample aspirated for treatment purposes. Normal peritoneal cells were collected from peritoneal dialysates of three donors free of cancer, peritonitis, bacterial infection, and hepatitis B/C virus. Suspended cells were collected by centrifugation, and cell debris was removed by Ficoll-PaqueTM PLUS (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) separation.

In vitro differentiation of M1-type or M2-type macrophages

Fresh PBMCs from two healthy donors were separated from whole blood samples using Ficoll-PaqueTM. CD14+ monocytes were selected using MACS human CD14 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), pre-separation filters (Miltenyi), and LS columns (Miltenyi) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. To induce M0 macrophages, isolated CD14+ monocytes were seeded onto FBS-coated 24-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells/cm2. Seeded cells were cultured for 7 days in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 20% FBS and 100 ng/ml M-CSF (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). On day 7, M-CSF-containing medium was removed, and appropriate stimulating media containing 100 ng/ml LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 20 ng/ml IFN-γ (BioLegend) for M1 induction or 20 ng/ml IL-4 (BioLegend) and 20 ng/ml IL-10 (BioLegend) for M2 induction were supplied. After an additional 48 h of culture, cells were collected by gentle scraping and then taken for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis or scRNA-seq. The morphological changes that occurred during differentiation were observed every 2 days under a microscope. A fraction of the cells was triple-stained with PE/Cy7 anti-human CD14 antibody (BioLegend), FITC anti-human CD80 antibody (BioLegend), and PE anti-human CD163 antibody (BioLegend) and analyzed by FACSVerse and FACSuite v1.2 (BD Biosciences).

Full-length single-cell RNA sequencing and data processing

Single-cell transcriptome data for GC, M1/M2 macrophages, and normal peritoneal cells were prepared using the C1TM Single-Cell AutoPrep System (Fluidigm, San Francisco, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Freshly prepared cell suspensions were loaded onto the C1 system, and amplified cDNAs were obtained. The type of microfluidic chip used in the C1 system was determined by the size distribution and average cell size of each sample. We quantified the amount of amplified cDNA using a Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and then assessed the quality using 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Successfully amplified cDNA from single cells (180 GC cells, 97 M1 cells, 45 M2 cells, and 25 normal peritoneal cells) were subjected to RNA sequencing.

Sequencing libraries were constructed with the Nextera XT DNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina) and sequenced with the HiSeq 2500 system in 100-bp paired-end mode using the TruSeq Rapid PE Cluster kit and the TruSeq Rapid SBS kit. The sequence reads were aligned to the UCSC hg19 human reference genome using the two-pass mode of STAR_2.4.0b (default parameters)12, and the transcript per million (TPM) value of each gene was quantified using RSEM v1.2.17 with default parameters13. The TPMij value for gene I in cell j was derived by summing the TPM values of the isoforms of gene i. To reduce the inflation effect of the TPM calculations on gene expression levels (Es), we defined Eij = log2(TPMij/10 + 1) as the gene expression value, as described previously14.

Unreliable cells expressing fewer than 1000 genes and unreliable genes expressed in fewer than 10 cells were excluded from further analysis. When filtering cells or genes, Eij > 1 was considered confident expression. Finally, 162 cells from GC patients, 97 M1 cells, 45 M2 cells, and 25 cells from normal peritoneum (peritoneal dialysate) were used. For normal peritoneal data, we counted unreliable genes as being expressed in fewer than 2 cells instead of 10 due to the small sample size. Based on marker gene expression, nine of the 25 normal peritoneal cells were considered macrophages (Ej for CD86 > 2, MUC16 < 1.1, EPCAM = 0, and CD3D = 0) and used for further analysis.

Batch correction using Harmony

Batch correction was performed using the RunHarmony function of the R package ‘harmony (v1.0)’15 (Supplementary Fig. 1c). To compare the effect of batch correction on cell type identification, the Jaccard index was calculated using the ‘jaccard’ function of the R package ‘jaccard (v0.1.0)’, and Fisher’s exact test was performed using the ‘fisher.test’ function of the R package ‘stat’.

Droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing and data processing

Massively parallel droplet-based data from malignant ascites of AGC04 patient was generated to target 5000 cells using the Chromium System (10× Genomics, Pleasanton, CA, USA) with the Single Cell 3′ Reagent Kit (v2) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were sequenced on the HiSeq 2500 system, and reads were aligned to the GRCh38 human reference genome using Cell Ranger v2.1 software with default options.

Expression matrix processing, cell clustering, and dimensionality reduction were performed using Seurat v3.0. The gene Es for gene i in cell j was defined as Eij = log2(pseudoTPMij + 1), where pseudoTPMij = UMIij/sum[UMItotal,j] * 10,000. Cells were clustered by the graph-based shared nearest-neighbor (SNN) method, and cells in cluster 0 and 4 that exhibited differentially expressing macrophage markers (such as CD68) were defined as macrophages. Low-quality cells that did not meet any of the following criteria were excluded from the macrophage analysis: (1) 1000 ≤ nCounts ≤ 150,000, (2) 200 ≤ nFeatures ≤ 10,000, and (3) percent of mitochondrial genes ≤ 20.

Processing of public dataset

Full-length data for breast cancer16 and colorectal cancer17 were processed as described above using raw fastq files, and then the macrophages identified in the original study were used after removing unreliable cells. Cell clustering and dimensionality reduction analysis were performed using Seurat v3.018. Public 10× data for primary GC19 and antral mucosa biopsies20 were subjected to data processing and unreliable cell removal as described in the original study, and macrophage clusters were identified based on marker gene expression. For the ovarian cancer ascites dataset21, the macrophages identified in the original study were used.

Chromosomal expression pattern (CEP) of single-cell RNA-seq data

The CEP reflecting copy number variation (CNV)14,22,23 was estimated from single-cell RNA-seq data. First, we performed Z-normalization on the expression values of autosomal genes and limited the Z-score range to [−3, 3]. After sorting the genes by their genomic positions (from chromosome 1 to chromosome 22), moving average values were calculated with a sliding window of 150 genes within each chromosome and then adjusted by centering. To estimate the CNV instability in each cell, we calculated the mean of squares (MS) of the CEP values. The mean difference in the MS values between epithelial cells and macrophages was determined by t-test, and mesothelial cells were excluded from statistical analysis because there were too few of this group (n = 5).

Cell–cell interaction analysis

Based on the Es of ligand–receptor pairs listed in the FANTOM5 database24, cellular interactions were inferred by assuming crosstalk between cells expressing the ligand and cells expressing the counterpart receptor. The ligand–receptor interaction was inferred from the binary expression of the ligand or receptor genes, with an expression value (Eij) threshold of 1. If one cell expresses ligand (Eij > 1) and another cell expresses the counterpart receptor (Eij > 1), we counted this ‘expression pair’ as the ‘intercellular interaction’. If one cell expressed both ligand and receptor genes (Eij > 1), we counted this expression pair as ‘self-sufficient signaling’. Additional ligand–receptor pairs for cytokine/chemokine signaling were collected from previous studies (listed in Supplementary Table 1).

Extraction of M1/M2-specific signatures

The M1-specific or M2-specific signature gene sets were constructed afresh using robust genes at single-cell resolution. First, we compared M1 and M2 cells in each donor. Expected counts from the RSEM of M1 and M2 cells were compared by LRT using edgeR25 and DESeq226. Both edgeR and DESeq2 recommend expected counts as input and provide LRT functions to extract differentially expressed genes from single-cell data. Normalization by the trimmed mean of the M-values (TMM) was performed before the LRT test when using edgeR. Thereafter, we filtered for markers for M1 and M2 macrophages. Genes with logFC > 2 (edgeR) or log2FoldChange > 2 (DESeq2) and FDR < 0.05 were obtained from each method. Finally, common markers from the two methods (Supplementary Fig. 4c) and from the two donors were selected. A total of 155 and 43 genes configured M1 and M2 signature gene sets, respectively.

Pathway analysis

To assess gene expression signatures and pathway activation, the signature Es was evaluated as Esj(S) = average [E1…n, j], where S is a gene set consisting of n genes. Public gene sets used for pathway analyses were collected from either the Molecular Signature Database (MSigDB) v6.127 or previous research papers (bulk-derived M1/M2 gene sets28 and curated M1/M2 gene sets7). The signature Es for gene set S was rescaled to [−1, 1] in Fig. 1e. The simple linear regression model was created by the ‘lm’ function of the R package ‘stat’ to show inclination toward the M2 axis (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs. 5–7).

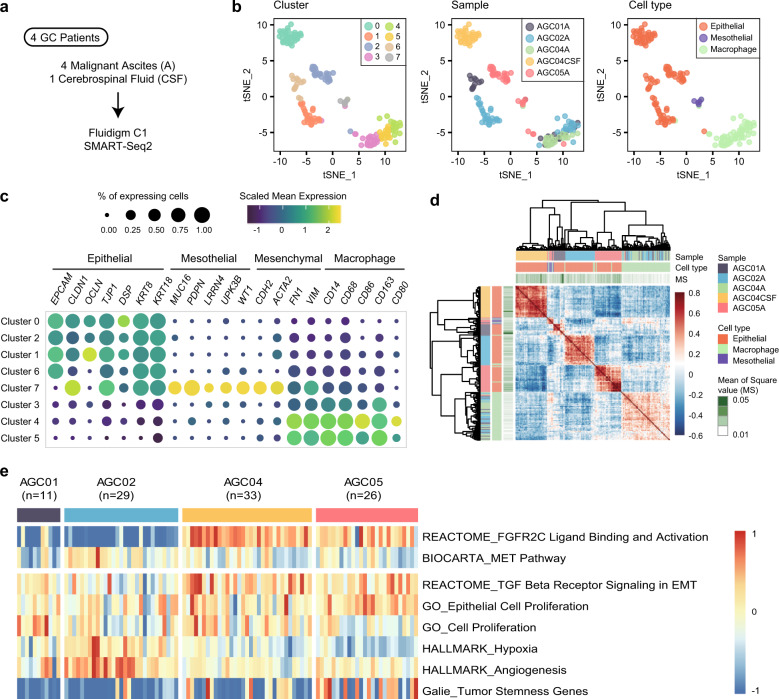

Fig. 1. Characterization of tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages in malignant ascites.

a Scheme of data generation in the study. b Dimension reduction using t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) separates noncancerous cell clusters and patient-specific cancer cell clusters. Each dot represents a cell, and each cell is colored by its SNN cluster (left), sample origin (middle), or cell type (right). c The expression of marker genes for epithelial cells, peritoneal mesothelial cells, mesenchymal cells, and macrophages clarified the cell type of the clusters. d Pearson’s correlation coefficient matrix of the CEP values. e Heatmap of tumor characteristics in the tumor cells. Each column represents a single cell.

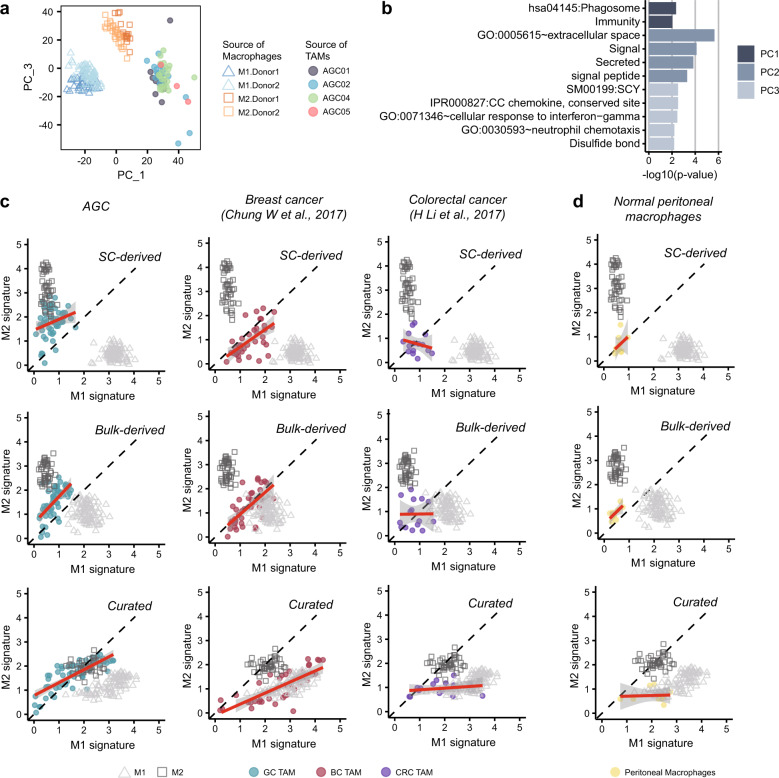

Fig. 4. In vitro differentiated M1 and M2 transcriptomes show the M1-like and M2-like features of TAMs.

a PCA grouped TAMs into a separate cluster from the reference M1 or M2 cells. Cells were colored based on the origin of the sample. b The GO terms describing each principal component show the functional difference between macrophage types (Bonferroni corrected p-value < 0.01). The top 50 genes on each principal component were analyzed by DAVID 6.853. c Two-dimensional dot plots for M1 and M2 signature evaluation were constructed for three cancer types using three different gene sets: single-cell transcriptome-derived signatures (top), bulk transcriptome-derived signatures (middle), and curated signatures (bottom). The x-axis indicates expression in the M1 signature, and the y-axis indicates expression in the M2 signature. The red line represents the simple linear regression line, and the gray area represents the confidence interval. d The M1–M2 signature 2-D plot estimates the M1-like and M2-like phenotypes of normal peritoneal macrophages.

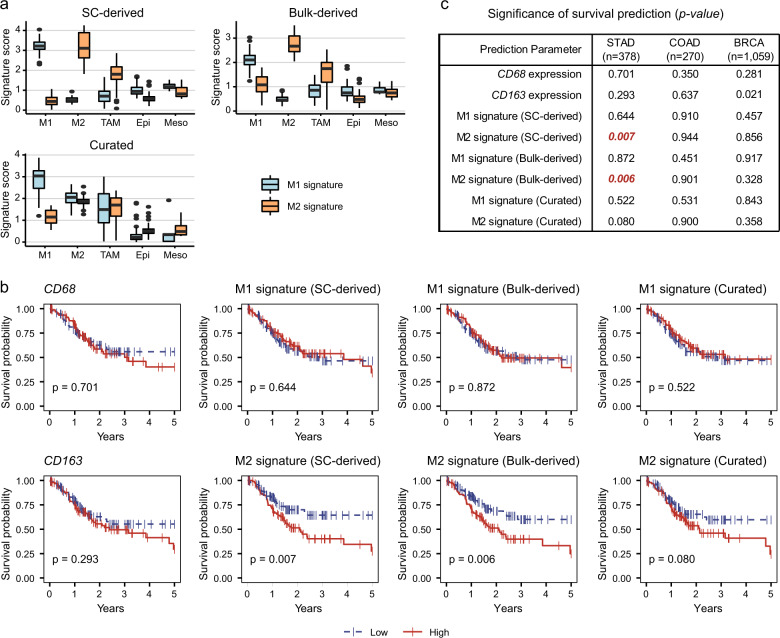

Survival analyses with the macrophage-specific gene signature

For the survival analysis, the expression data (RNA sequencing, level 3) of stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), colorectal adenocarcinoma (COAD), and breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA) datasets were obtained from TCGA (updated in 2017). Only samples with clinical information on pathological stage and survival information were used for further analysis (STAD, n = 378; COAD, n = 270; BRCA, n = 1059). The Es for gene i in sample l was defined as Eil = log2 (TPMil/10 + 1). For gene set S consisting of n genes, the signature Es was evaluated as Esl(S) = average[E1…n, l] only for the genes detected in the bulk RNA-seq data. The ‘high’ group and ‘low’ group for Kaplan–Meier analysis were determined by the 25th and 75th percentiles. Survival curves and significance were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier formula of the R packages ‘survival’ and ‘survminer’.

Results

Identification of cell types in malignant ascites of GC

For cellular characterization of malignant ascites, we obtained full-length scRNA-seq data for 180 cells from four patients by the SMART-Seq2 method in the C1 microfluidic system (Table 1)29. For one patient, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) metastasis was analyzed in parallel (Fig. 1a). Unsupervised clustering using a SNN algorithm was used for cell classification after principal component analysis (PCA), and the SNN graph was projected using t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE)30. Five patient-specific clusters (0, 1, 2, 6, and 7) and three multipatient clusters (3, 4, and 5) were classified (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1a). From the literature review, we expected a collection of GC cells, tumor-associated immune cells, and peritoneum-derived mesothelial cells as the main cell types31,32. Indeed, marker genes indicated the cluster identities (Fig. 1b right); four (clusters 0, 1, 2, and 6) were epithelial cancer cells, one (cluster 7) was mesothelial cells, and three (clusters 3, 4, and 5) were macrophages (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1b)33–36.

Table 1.

Clinical information of specimen donors.

| Patient | AGC01 | AGC02 | AGC04 | AGC05 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Adenocarcinoma, poorly differentiated | Signet ring cell carcinoma | Adenocarcinoma, poorly differentiated | Signet ring cell carcinoma |

| Metastases | Ascites | Ascites | Ascites, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) | Ascites |

| Stage | IV | IV | IV | IV |

| Age | 51 | 78 | 45 | 42 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Female | Female |

| MSI type | MSS | n/c | MSS | MSS |

| Genomic aberrations | PIC3CA mutation | – | FGFR2 amplification | FGFR2 amplification |

Considering the potential batch effect derived from samples, the cell types identified with or without sample batch correction were compared. The odds ratio was 140.81 for epithelial cells, 77.61 for mesothelial cells, and 393.24 for macrophages (p-value < 0.001), suggesting no significant batch effect in our data analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1c). In ascites of AGC04 (AGC04A), we failed to find any epithelial cells. To investigate whether the absence of epithelial cells in AGC04A is real or sampling bias, we generated large-scale data for AGC04A via a massively parallel droplet-based single-cell RNA-seq method and analyzed the transcriptomes of 1768 cells. As a result, we recovered a small number of epithelial tumor cells along with large numbers of macrophages and T cells (Supplementary Fig. 2). These results demonstrate the limitation of the C1 platform in capturing the comprehensive cellular landscape of the tumor microenvironment. Therefore, we focused on the specific molecular features of two major populations in GC ascites in the downstream analysis: tumor cells and macrophages.

Most cells from cluster 7 expressed both epithelial and mesenchymal markers, including KRT8, KRT18, CLDN1, TJP1, CDH2, and ACTA2. These gene expression features suggest EMT of mesothelial cells and consequent damage to the peritoneal membrane when GC spreads to the peritoneum37. Mesothelial cells, despite their small numbers, were separately clustered from the epithelial cells in the global (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2a) and CEPs (Supplementary Fig. 3a). We used CEP to infer CNVs as a hallmark of malignant cells. The epithelial cell clusters demonstrated patient-specific CEP, with higher copy number fluctuations than the mesothelial cell or macrophage cell clusters (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Hierarchical clustering using Pearson’s correlation coefficient of CEPs distinguished four epithelial tumor groups, one mesothelial group, and one macrophage group, thus recapitulating the clusters in global gene expression (Fig. 1d). The four epithelial tumor clusters showed patient-specific tumor characteristics (high FGFR2 or MET) and intratumoral heterogeneity in gene expression signatures of cancer-related processes, such as cell proliferation, stemness, TGF-β signaling in EMT, hypoxia, and angiogenesis (Fig. 1e).

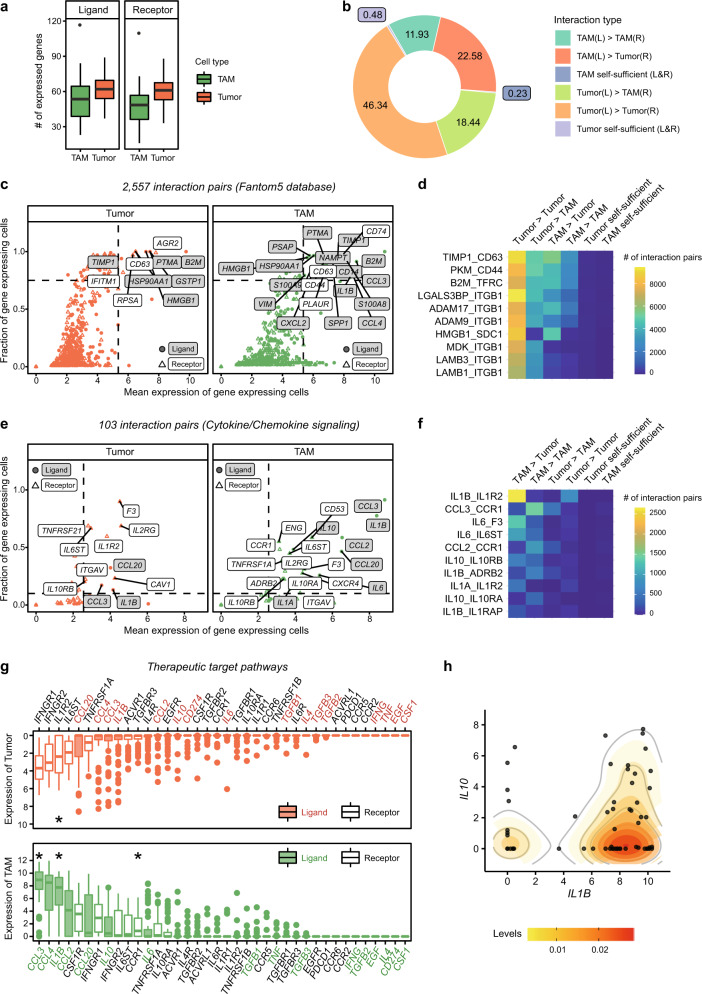

Interaction between tumor cells and macrophages in malignant ascites

The concerted action of the tumor and the associated microenvironment generates a unique ecosystem promoting tumor growth and invasion in a metastatic setting. To delineate the cellular interplay in malignant ascites, we inferred the molecular interactions by quantifying the expression of ligand–receptor pairs listed in the FANTOM5 database24. When we enumerated the expression of ligands and receptors in tumor cells and macrophages (Fig. 2a), the paired expression trended more toward intercellular interactions than self-sufficient signaling (Fig. 2b). The most common interaction pairs were composed of adhesion molecules with a wide range of specificity (Fig. 2c and d). Among them, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1) can promote cell proliferation38 and protect cells from hypoxia-induced apoptosis via TIMP1-CD63 signaling39. Integrin beta 1 subunit (ITGB1), together with multiple integrin alpha subunits, can interact with pleiotropic ligands and promote cancer cell proliferation and metastasis40,41.

Fig. 2. Tumor-promoting interactions of cancer cells and macrophages in malignant ascites.

a The number of expressed ligand (left) or receptor (right) genes from the FANTOM5 database in each cell. b Putative intercellular interactions between two other cells are much more prominent than was putative self-sufficient signaling. Intercellular interaction types were indicated by ‘ligand-expressing cell (L)>receptor-expressing cell (R)’. c Strongly and commonly expressed interacting genes in tumors (left) or TAMs (right). The genes with average expression over quantile 0.95 and a fraction of expressing cells over 0.75 were labeled. d Top 10 abundant interaction pairs (>10,224 pairs in each interaction) related to c. e Strongly and commonly expressed interacting genes among the chemokine-related interactions (Supplementary Table 1a). Genes with average expression over quantile 0.5 and a fraction of expressing cells over 0.1 were labeled. f Top 10 abundant interaction pairs (>406 pairs in each interaction) related to e. g Expression level of the genes associated with macrophage function (Supplementary Table 1b) indicates high expression of CCL3, IL1B, and CCR1 in macrophages and IL1R2 in tumor cells (marked with a star). h Coexpression of IL1B and IL10 in TAMs. The x and y-axes show the expression levels of IL1B and IL10, respectively. Each dot represents a cell, and each cell was colored based on the sample origin. Expressed genes were evaluated based on threshold 1 in a–f.

Next, we focused on more specific interactions that mediate cytokine or chemokine signaling (Supplementary Table 1)42,43. The majority of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) expressed proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine genes, such as IL1B, CCL2, CCL3, and CCL20 (Fig. 2e). Interestingly, the most abundant cytokine–receptor pair interaction between TAMs and tumor cells was predicted for IL1B and its decoy receptor IL1R2 (Fig. 2f and g), suggesting the inhibition of IL1B-mediated proinflammatory signaling by tumor cells. In addition, the IL10–IL10RA interaction within TAM populations also limits inflammatory immune responses. Indeed, many TAMs coexpress IL1B and IL10 (Fig. 2h). The CCL2/CCL3–CCR1 interaction within TAM populations may represent a distal loop for macrophage recruitment (Fig. 2f and g). Altogether, these results provide a systemic view of the molecular and cellular network in malignant ascites, fostering an anti-inflammatory microenvironment and supporting tumor growth and invasion.

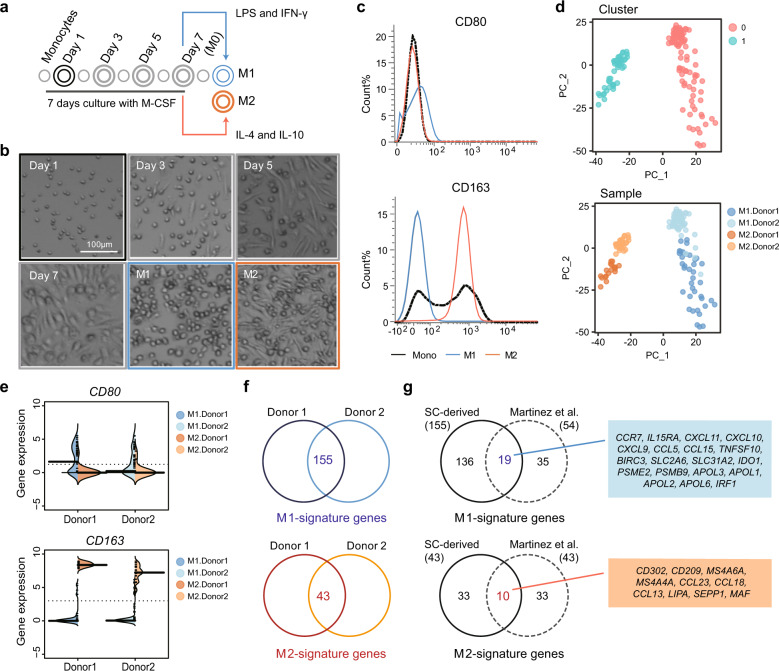

Construction of the reference macrophage transcriptome at single-cell resolution

In different tissues and disease conditions, macrophages show a broad phenotypic spectrum in their inflammatory nature, ranging from the proinflammatory M1 type to the anti-inflammatory M2 type. Although studies have shown that macrophages have various states beyond the dichotomous definition of M1 and M2, extremely differentiated proinflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages are still valuable as reference points for determining the characteristics of macrophages. M2-like macrophages show tumor-promoting activity in vitro, and a high M2/M1 macrophage ratio is associated with poor prognosis in GC44. To provide quantifiable gene expression criteria for M1 or M2 characteristics, we generated a single-cell transcriptome reference for these macrophage populations (Fig. 3a). Briefly, we isolated monocytes from the blood of two healthy donors, cultured them with M-CSF, and then induced differentiation to the M1 or M2 type with LPS/IFN-gamma or IL-4/IL-10, respectively. Cellular morphology and surface marker expression confirmed successful induction of M1 and M2 macrophages (Fig. 3b, c). Finally, 97 M1 and 45 M2 cells were captured and subjected to full-length mRNA sequencing in the C1 platform. PCA demonstrated that M1-type and M2-type macrophages have highly variable transcription features and can be separated by the first principal component (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Fig. 4a and b). The second principal component separated the two donors, indicating donor-specific gene expression variability (Fig. 3d). However, differential gene expression pattern between the M1-type and M2-type macrophages was similar for the two donors (Fig. 3e).

Fig. 3. M1- and M2-signature genes at single-cell resolution.

a Scheme of the in vitro differentiation of M1-type and M2-type macrophages. b Morphological changes during differentiation. c FACS analysis of the M1-specific marker CD80 and the M2-specific marker CD163 in differentiated M1 and M2 cells. The examined samples are colored with borders in a (black for monocytes, blue for M1 macrophages, and orange for M2 macrophages). d Unsupervised PCA primarily separated M1 and M2 macrophages by the first principal component. Cells are colored by cluster (upper) or sample origin (lower). e Gene expression levels of CD80 and CD163 in single-cell RNA-seq data confirmed M1 and M2 polarization. The thick black line indicates the median value of each sample. f M1-specific or M2-specific signature genes were extracted by overlapping differentially expressed genes from both donors. g Comparison with published gene sets derived from bulk M1 and M2 signatures28. Only 29 genes were repeatedly extracted from single-cell and bulk signatures.

To extract differentially expressed genes from M1 and M2 macrophages, we used the likelihood ratio test (LRT) on zero-inflated data for each donor (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Fig. 4c, and Supplementary Table 2). A total of 155 and 43 genes were concurrently extracted from two donors as M1-specific and M2-specific signatures, respectively. Among these, 29 genes overlapped with the M1-specific or M2-specific gene sets generated from pooled cells using microarray data (Fig. 3g)28. These 29 overlapping genes showed high levels of differential expression between M1 and M2 (Student’s t-test p-value < 1e5) (Supplementary Fig. 4d) and may be used as platform-independent gene expression markers for distinguishing the two macrophage types at both bulk and single-cell levels.

M1–M2 polarization map of TAMs

Using the single-cell transcriptome as a reference, we assessed the M1/M2 polarization status of TAMs in malignant ascites of GC. PCA distinguished global transcriptomic profiles of TAMs from M1 or M2 reference cells, which is consistent with previous findings that distinctive macrophage states exist in tumors (Fig. 4a)7–9. Gene ontology analysis for each PC suggests that TAMs differ from M1 or M2 macrophages in phagocytic activity but are similar to M1 macrophages in chemokine secretion and response to external stimuli such as IFN-γ (Fig. 4b). Consistently, we have shown via cellular interaction analysis that TAMs abundantly express proinflammatory cytokines (Fig. 2). However, the M1 versus M2 polarization map suggests that TAMs from GC ascites are more like M2 macrophages than M1 macrophages. In a comparative analysis of M1 vs. M2 polarization, our single cell-derived signatures separated the reference cells well and positioned the GC ascites TAMs toward the M2 axis (Fig. 4c, top left). These separation patterns were similarly repeated in the bulk microarray-derived signatures (Fig. 4c middle left)28. The curated signatures (Fig. 4c bottom left)7 failed to position reference cells in the M2 axis but endowed similar polarization status for the M2 reference cells and GC ascites TAMs. Thus, all three methods ascertained that TAMs from the malignant ascites of GC resemble M2 reference cells more than M1 reference cells. The 10× data for AGC04A consistently show the M2-like characteristics and patterns of GC ascites TAMs when accounting for all three gene sets (Supplementary Fig. 5). Application of M1 vs. M2 scoring of TAMs from breast or colorectal cancer tissues demonstrated less inclination toward the M2 axis, indicating a strong M2-like polarization status of GC ascites TAMs (Fig. 4c).

The M2 polarization states for different TAMs might have been influenced by tissue origin and the cell isolation process. Some studies have shown that peritoneal macrophages have an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype45, and enzymatic dissociation of solid tumor tissues may induce inflammatory gene expression46. To address the first issue, we compared the M1 and M2 scores in normal peritoneal macrophages (Fig. 4d). Macrophages released from the normal peritoneum show a slight M2-like phenotype but a nearly balanced polarization state, indicating that the strong M2 polarization of GC macrophages is not the sole representation of tissue origin. In addition, the TAMs of primary GC show only a modest inclination toward M2 macrophages in the curated gene set, while there were no inclinations for normal tissues, peripheral blood, or early GC19 (Supplementary Fig. 6a). The independent data repeatedly show a balanced state of macrophages in nontumor stomach or early GC20 (Supplementary Fig. 6b). In malignant ascites of ovarian cancer21, TAMs show a pattern trending toward M2 (Supplementary Fig. 7). We addressed the second issue by comparing a list of dissociation-induced gene (such as EGR1, FOS, FOSB, JUN, JUNB, SOCS3, HSP90AA1, HSPA1A, HSPA1B, and HSPA8)46 and our M1/M2-specific genes. None of these genes were included in the M1 or M2 signature gene lists.

These data suggest that the experimentally derived single cell-level gene sets provide an objective reference for macrophage polarization and that using a reference transcriptome would prevent incorrect conclusions from being made due to internal comparison.

Prediction of overall survival using M2-specific signature genes in GC

When characterizing TAMs from the bulk tissue expression data, non-macrophage cells expressing macrophage signature genes may interfere with TAM profiling. To test the exclusive expression of macrophage signature genes, we compared single-cell transcriptome profiles of M1 and M2 reference cells with those of TAMs, epithelial cells, and mesothelial cells from malignant ascites of GC (Figs. 1 and 5a). In the evaluation of M1 and M2 reference cells, our single-cell-derived or bulk microarray-derived gene sets showed good performance in the distinction of reference cells. Importantly, both M2 signatures maintained exclusivity in TAMs, showing much higher expression than that in epithelial and mesothelial cells. However, the level of M1 signature gene expression was comparable or higher in the non-macrophage populations. These results imply that the single-cell-derived and bulk microarray-derived M2 signature can be used to evaluate TAMs in bulk tissue data, whereas the M1 signature is not appropriate for evaluating the characteristics of macrophages in bulk tissue data. By comparison, the curated gene sets and M2 signature in particular showed a poor performance in representing reference cells.

Fig. 5. The M2 phenotype of TAMs can be applied to predict the prognosis in gastric cancer.

a Transcriptome-driven M2 signatures, not curated signatures, are high exclusively in M2-type cells. M1 reference M1 cells, M2 reference M2 cells, TAM macrophages from GC, Epi epithelial cells from GC, Meso mesothelial cells from GC. b Overall survival prediction was performed using the TCGA STAD dataset (n = 378) and either signature gene sets or canonical macrophage markers, such as CD68 and CD163. The ‘high’ group (red) and ‘low’ group (blue) were determined by the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. p indicates the p-value of log-rank test. c Summary table of p-values for overall survival using the TCGA dataset for the three cancer types (STAD, n = 378; COAD, n = 270; and BRCA, n = 1059).

To investigate the prognostic value of macrophage-specific signatures, we performed survival analysis on the TCGA bulk RNA-seq dataset (STAD, n = 378) (Fig. 5b). GC patients with a ‘high’ M2 signature had considerably worse survival than did the patients with a ‘low’ M2 signature (p-value 0.007 for the SC-derived M2 signature; 0.006 for the bulk-derived M2 signature). In the TCGA STAD set, the M1 signature and canonical macrophage markers, such as CD68 and CD163, showed no prognostic association (p-value > 0.05, Fig. 5b). As no M2 inclination was observed in breast cancer and colorectal cancer (Fig. 4c), we expected that the M2 signature could not predict survival in breast cancer and colorectal cancer. Indeed, none of the M1 or M2 signatures were associated with survival in COAD (n = 270) or BRCA (n = 1059) (Fig. 5c). Only CD163, not M2-signature, showed an association with poor prognosis in breast cancer (p-value = 0.021).

We further tested the prognostic value of individual genes comprising the M2-specific signature gene set to verify the effect of a single gene on the M2 signature and found that six genes (CITED2, DACT1, CCDC152, DAB2, SEPP1, and THBD) retained statistical significance for predicting survival (p-value < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 8a–c). Nevertheless, five of these six genes had limited power in representing the TAM population in vivo. DACT1 and CCDC152 showed low expression in GC TAMs, and DAB2, SEPP1, and THBD were abundantly expressed in non-macrophage populations as well as in macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 8a and d). Gene expression in non-macrophage populations indicates contributions from these cells. By contrast, CITED2 (CBP/p300-interacting transactivator with glutamic acid/aspartic acid-rich carboxyl-terminal domain 2) was expressed exclusively in TAMs or M2-type macrophages, suggesting a more specific role of this gene in the anti-inflammatory polarization of macrophages. Excluding each gene from the single-cell-derived M2 signature maintained a negative association with the survival rate (Supplementary Fig. 9). These results suggest that a single-cell-derived M2 signature can be used as a robust predictive parameter for survival.

Taken together, these data support the use of an M2-specific 43-gene expression signature for assessing the anti-inflammatory features of TAMs and predicting prognosis in GC with minimal interference from non-macrophage cells.

Discussion

We showed that TAMs from malignant ascites in GC have strong M2-like characteristics and that this M2-like phenotype of TAMs is associated with poor prognosis in GC. Based on the intercellular interactions between tumor cells and macrophages, we speculated on the recruitment of macrophages and their transition to TAMs with anti-inflammatory properties. Since macrophages manifest a wide range of phenotypic and functional flexibility in vivo, we first dichotomized macrophage references as pro-inflammatory M1 or anti-inflammatory M2 cells and then systemically ordered TAMs based on their inflammatory states47. Thus, we generated a single-cell transcriptome reference for explicit M1 and M2 cells, which would allow us to evaluate the inflammatory or anti-inflammatory status of TAMs in a systemic manner. By establishing a reference transcriptome, we confirmed that TAMs in the malignant ascites of GC reflected the features of M2-type macrophages.

In GC patients with ascites, blocking Rho-GTPases RhoA (RhoA) can be an applicable strategy to overcome the poor prognosis conferred by M2-like macrophages. RhoA regulates the migration and invasion of cancer cells induced by M2-like macrophages, and these effects can be attenuated by Rho-associated protein kinase inhibitors48. Intriguingly, RHOA mutations were enriched in the GS subtype of TCGA1. In preclinical studies, RhoA inhibition successfully overcame chemotherapy resistance in both diffuse-type GC stem-like cell models and diffuse GC xenograft models49. More research is needed to investigate the effectiveness of RhoA inhibitors in GC, and the modulation of the M2-like phenotype of TAMs by RhoA inhibitors is a potential strategy targeting PC in GC.

Remarkably, we also identified that macrophages collected from metastatic fluid of GC showed the most M2-like features compared to macrophages from other cancer types, such as breast cancer and colorectal cancer (Fig. 4). The reason for the distinct M2-like characteristics in GC ascites is unclear. It is possible that GC has unique tumor characteristics or that they are in the most malignant state, and tumor progression in other cancer types may eventually induce a strong M2 phenotype. To investigate these possibilities, a large-scale study using various cancer types at diverse stages is needed. Moreover, expanding the scope of research to multiomics would reveal the precise tumor-associated mechanisms of M2-like TAMs in various conditions.

In GC, a large number of TAMs could be isolated from late-stage specimens with peritoneal dissemination, which express CD163 and CD20450. Late-stage TAMs expressed higher mRNA levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 but lower levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-alpha than do early-stage GC TAMs. Importantly, the pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory state of macrophages could be converted by different in vitro culture conditions51, suggesting that reciprocal M2 to M1 conversion may be achieved in vivo by altering the tumor microenvironment.

After constructing the M2-specific signature gene set from single-cell reference transcriptomes, the prognostic power of the M2 signature was evaluated. In addition, we found that CITED2 alone has prognostic value in predicting overall survival in GC by representing macrophage M2 properties (Supplementary Fig. 8). CITED2 is a negative regulator of proinflammatory macrophages and promotes anti-inflammatory functions52. Depletion of CITED2 in myeloid cells inhibits PPARγ activation and induces HIF1α stabilization, leading to a proinflammatory response. Our results support the notion that myeloid-specific depletion of CITED2 could be used as a new immunotherapeutic strategy.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank all the donors. We also thank Jung Eun Lee from the Division of Nephrology and Dong Hyun Shin from the Department of Internal Medicine at Samsung Medical Center for coordinating the peritoneal dialysis samples. We acknowledge the KREONET/GLORIAD service provided by the Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information. All sequencing was performed at Samsung Genome Institute. This study was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science & ICT (MSIT) (NRF-2017M3A9A7050803 to W.-Y.P. and 2019M3A9B6064691 to H.-O.L.) and the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) (NRF-2018R1A6A3A11045761 to HHE).

Author contributions

H.-O.L. and W.-Y.P. conceived and designed the study. H.H.E. and A.J. performed the experiments with guidance from H.-O.L. H.H.E. and D.R. performed the computational analyses with input from W.C., N.K., Y.H., and H.-O.L. D.-S.S. provided critical statistic guidance. M.K., S.T.K., and J.L. contributed to the clinical interpretation of the data. H.H.E., M.K., H.-O.L., and W.-Y.P. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

All raw sequencing data and the filtered, processed data generated in this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus repository under the accession number GSE140182 (private access token: wlofwecmprwtfst). The accession numbers of public datasets are as follows: breast cancer16 (GSE75688), colorectal cancer17 (EGAS00001001945), primary gastric cancer19 (phs001818), antral mucosa biopsies20 (GSE134520), and ovarian cancer ascites21 (GSE146026).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Hye Hyeon Eum, Minsuk Kwon

Contributor Information

Hae-Ock Lee, Email: haeocklee@catholic.ac.kr.

Woong-Yang Park, Email: woongyang.park@samsung.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s12276-020-00538-y.

References

- 1.Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202–209. doi: 10.1038/nature13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cristescu R, et al. Molecular analysis of gastric cancer identifies subtypes associated with distinct clinical outcomes. Nat. Med. 2015;21:449–456. doi: 10.1038/nm.3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chau I, et al. Multivariate prognostic factor analysis in locally advanced and metastatic esophago-gastric cancer-pooled analysis from three multicenter, randomized, controlled trials using individual patient data. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22:2395–2403. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim ST, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clinical responses to PD-1 inhibition in metastatic gastric cancer. Nat. Med. 2018;24:1449–1458. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0101-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee J, et al. Development of mesenchymal subtype gene signature for clinical application in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:66305–66315. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soundararajan, R. et al. Targeting the Interplay between epithelial-to-mesenchymal-transition and the immune system for effective immunotherapy. Cancers11, 10.3390/cancers11050714 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Azizi E, et al. Single-cell map of diverse immune phenotypes in the breast tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2018;174:1293–1308.e1236. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Q, et al. Landscape and dynamics of single immune. Cells Hepatocell. Carcinoma Cell. 2019;179:829–845.e820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller S, et al. Single-cell profiling of human gliomas reveals macrophage ontogeny as a basis for regional differences in macrophage activation in the tumor microenvironment. Genome Biol. 2017;18:234. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1362-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song Q, et al. Dissecting intratumoral myeloid cell plasticity by single cell RNA-seq. Cancer Med. 2019;8:3072–3085. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee J, et al. Tumor genomic profiling guides patients with metastatic gastric cancer to targeted treatment: the VIKTORY Umbrella Trial. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:1388–1405. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobin A, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinforma. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tirosh I, et al. Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science. 2016;352:189–196. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korsunsky I, et al. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat. Methods. 2019;16:1289–1296. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0619-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung W, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq enables comprehensive tumour and immune cell profiling in primary breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15081. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, et al. Reference component analysis of single-cell transcriptomes elucidates cellular heterogeneity in human colorectal tumors. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:708–718. doi: 10.1038/ng.3818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stuart T, et al. Comprehensive Integration of Single-cell data. Cell. 2019;177:1888–1902. e1821. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sathe A, et al. Single-cell genomic characterization reveals the cellular reprogramming of the gastric tumor microenvironment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;26:2640–2653. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang P, et al. Dissecting the single-cell transcriptome network underlying gastric premalignant lesions and early gastric cancer. Cell Rep. 2019;27:1934–1947.e1935. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Izar B, et al. A single-cell landscape of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1271–1279. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0926-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel AP, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science. 2014;344:1396–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1254257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puram SV, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of primary and metastatic tumor ecosystems in head and neck cancer. Cell. 2017;171:1611–1624 e1624. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramilowski JA, et al. A draft network of ligand–receptor-mediated multicellular signalling in human. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7866. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Smyth GK. Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4288–4297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez FO, Gordon S, Locati M, Mantovani A. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: new molecules and patterns of gene expression. J. Immunol. 2006;177:7303–7311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Picelli S, et al. Smart-seq2 for sensitive full-length transcriptome profiling in single cells. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:1096–1098. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amir el AD, et al. viSNE enables visualization of high dimensional single-cell data and reveals phenotypic heterogeneity of leukemia. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:545–552. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kipps E, Tan DS, Kaye SB. Meeting the challenge of ascites in ovarian cancer: new avenues for therapy and research. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2013;13:273–282. doi: 10.1038/nrc3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li J, et al. The impact of inflammatory cells in malignant ascites on small intestinal ICCs’ morphology and function. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2015;19:2118–2127. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Epiney M, Bertossa C, Weil A, Campana A, Bischof P. CA125 production by the peritoneum: in-vitro and in-vivo studies. Hum. Reprod. 2000;15:1261–1265. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.6.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashimoto K, Honda K, Matsui H, Nagashima Y, Oda H. Flow cytometric analysis of ovarian cancer ascites: response of mesothelial cells and macrophages to cancer. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:3579–3584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanamori-Katayama M, et al. LRRN4 and UPK3B are markers of primary mesothelial cells. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e25391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kienzle A, et al. Free-floating mesothelial cells in pleural fluid after lung surgery. Front. Med. 2018;5:89. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aroeira LS, et al. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition and peritoneal membrane failure in peritoneal dialysis patients: pathologic significance and potential therapeutic interventions. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007;18:2004–2013. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006111292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gong Y, et al. TIMP-1 promotes accumulation of cancer associated fibroblasts and cancer progression. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e77366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toricelli M, Melo FH, Peres GB, Silva DC, Jasiulionis MG. Timp1 interacts with beta-1 integrin and CD63 along melanoma genesis and confers anoikis resistance by activating PI3-K signaling pathway independently of Akt phosphorylation. Mol. Cancer. 2013;12:22. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen MB, Lamar JM, Li R, Hynes RO, Kamm RD. Elucidation of the roles of tumor integrin beta1 in the extravasation stage of the metastasis cascade. Cancer Res. 2016;76:2513–2524. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat. Med. 2013;19:1423–1437. doi: 10.1038/nm.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang L, Zhang Y. Tumor-associated macrophages: from basic research to clinical application. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017;10:58. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0430-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raiha MR, Puolakkainen PA. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) as biomarkers for gastric cancer: a review. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 2018;4:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cdtm.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu W, et al. Human peritoneal macrophages show functional characteristics of M-CSF-driven anti-inflammatory type 2 macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007;37:1594–1599. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van den Brink SC, et al. Single-cell sequencing reveals dissociation-induced gene expression in tissue subpopulations. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:935–936. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Italiani P, Boraschi D. From monocytes to M1/M2 macrophages: phenotypical vs. functional differentiation. Front Immunol. 2014;5:514. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Little AC, et al. IL-4/IL-13 stimulated macrophages enhance breast cancer invasion via Rho-GTPase regulation of synergistic VEGF/CCL-18 signaling. Front. Oncol. 2019;9:456. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoon C, et al. Chemotherapy resistance in diffuse-type gastric adenocarcinoma is mediated by rhoa activation in cancer stem-like cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;22:971–983. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 50.Yamaguchi T, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages of the M2 phenotype contribute to progression in gastric cancer with peritoneal dissemination. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:1052–1065. doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0579-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davis MJ, et al. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization dynamically adapts to changes in cytokine microenvironments in Cryptococcus neoformans infection. MBio. 2013;4:e00264–00213. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00264-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim, G. D. et al. CITED2 Restrains proinflammatory macrophage activation and response. Mol. Cell. Biol. 38, 10.1128/MCB.00452-17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Dennis, G. Jr. et al. DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol.4, P3 (2003). [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All raw sequencing data and the filtered, processed data generated in this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus repository under the accession number GSE140182 (private access token: wlofwecmprwtfst). The accession numbers of public datasets are as follows: breast cancer16 (GSE75688), colorectal cancer17 (EGAS00001001945), primary gastric cancer19 (phs001818), antral mucosa biopsies20 (GSE134520), and ovarian cancer ascites21 (GSE146026).