Abstract

Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT2) is a member of the STAT family that plays an essential role in immune responses to extracellular and intracellular stimuli, including inflammatory reactions, invasion of foreign materials, and cancer initiation. Although the majority of STAT2 studies in the last few decades have focused on interferon (IFN)-α/β (IFNα/β) signaling pathway-mediated host defense against viral infections, recent studies have revealed that STAT2 also plays an important role in human cancer development. Notably, strategic research on STAT2 function has provided evidence that transient regulatory activity by homo- or heterodimerization induces its nuclear localization where it to forms a ternary IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) complex, which is composed of STAT1 and/or STAT2 and IFN regulatory factor 9 (IEF9). The molecular mechanisms of ISGF3-mediated ISG gene expression provide the basic foundation for the regulation of STAT2 protein activity but not protein quality control. Recently, previously unknown molecular mechanisms of STAT2-mediated cell proliferation via STAT2 protein quality control were elucidated. In this review, we briefly summarize the role of STAT2 in immune responses and carcinogenesis with respect to the molecular mechanisms of STAT2 stability regulation via the proteasomal degradation pathway.

Subject terms: Melanoma, Protein-protein interaction networks

Cancer: Significance of stability of regulatory protein

The activity of STAT2, a protein stimulated by molecular signalling systems to activate selected genes in ways that can lead to cancer, is regulated by factors controlling its rate of degradation. Yong-Yeon Cho and colleagues at The Catholic University of Korea in South Korea review the role of STAT2 in links between molecular signals of the immune response and the onset of cancer. They focus on the significance of factors that regulate the stability of STAT2. One key factor appears to be the molecular mechanisms controlling the degradation of STAT2 by cellular structures called proteasomes. These structures break down proteins as part of routine cell maintenance. Deeper understanding of the stimulation, action and degradation of STAT2 will assist efforts to treat the many cancers in which STAT2 activity is involved.

Introduction

Our recent studies have demonstrated that signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 (STAT2) stability regulation plays an important role in melanoma formation. Serine/threonine phosphorylation of STAT2 by glycogen synthase kinase 3 α/β (GSK3α/β) enhances the recruitment of the S-phase kinase-associated protein 1 (SKP1)-cullin 1 (CUL1)-F-box protein-FBXW7 (SCFFBXW7) complex, resulting in STAT2 destabilization by ubiquitination-mediated degradation. There are several phosphorylation sites on the STAT2 protein. The ultimate fate of STAT2 protein, such as dimerization-mediated nuclear localization and activation, enhancement of transactivation activity, or destabilization, is dependent on its phosphorylation status at specific amino acid residues and the cellular context. Although the phosphorylation of a STAT protein is a predominant mechanism for regulating its activity, accumulating evidence indicates that regulation of the STAT protein level modulates STAT activity by ubiquitination and destabilization via the proteasomal degradation pathway1. The stability regulation of STAT proteins has been analyzed, and the recently published results focused on STAT1 and STAT3. The specific ubiquitin ligase for STAT1 and STAT4, known as STAT-interacting LIM protein (SLIM), was previously discovered2. SLIM was shown to contain the PSD95/Dlg/ZO-1 and LIM domains. The LIM domain, which forms a zinc-finger structure related to the really interesting new gene finger and plant homeodomain structures, exhibits E3 ligase activity. Thus, SLIM promotes both the ubiquitination and degradation of STAT1 and STAT42. Moreover, SLIM-knockout mice show enhanced STAT1 and STAT4 protein levels, resulting in increased interferon (INF)-γ (IFNγ) production in type 1T helper (Th1) cells. These findings show SLIM to be the first known cellular ubiquitin ligase with specificity for STAT proteins2. Since INF imposes restrictions against viral infection, virus-mediated destabilization of STAT proteins, which involves hijacking cellular factors that target STAT proteins, is an important molecular mechanism for viral evasion. A shorter protein half-life of STAT1 was shown to be triggered by infection with paramyxoviruses3, mumps virus4, and Sendai virus5. The ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of STAT2 was shown to be caused by stimulation with paramyxoviruses3, cytomegalovirus6, and dengue virus7. These viral infections seem to recruit STAT1/2 proteins to the CUL4A-based ubiquitination complex for the proteasomal degradation of STAT1/28. The data indicate that STAT protein activity can be modulated through protein stability regulation. The biological processes of the ubiquitin-proteasome system are mediated by three enzymatic reactions involving ubiquitin-activating E1 enzyme, ubiquitin-conjugating E2 enzyme, and ubiquitin–protein E3 enzyme. Thus, E3 ligases play a crucial role in determining target proteins for ubiquitination and degradation by E1–E3 enzymes9. Functional analysis of the F-box protein has demonstrated that the C-terminal domain (CTD) and F-box domain (FD) contribute to the selection of specific substrates for degradation. The CTD is involved in binding to specific substrates, while the FD acts as a protein–protein interaction domain by directly binding with adaptor protein SKP1 and recruiting F-box protein to the SCF complex10 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Basic molecular structure of the SCF complex.

The SCF (SKP1-CUL1-F-box protein) ubiquitin ligase complex is the most well-characterized cullin RING ubiquitin ligase (CRL). Since the F-box proteins contain approximately 69 different components that bind to SKP1, many different combination of specific SCF complex formation are possible with a selective substrate and depending on the cellular context. Moreover, eight cullin proteins add a more complicated combinational probability for tissue, developmental, and stimuli specificities. Finally, the ubiquitination in mono-, multi-, single-chain, poly-chain, and branched-chain patterns might indicate precise regulation of the cellular functions of proteins by reflecting diverse cell conditions.

Since STAT2 plays an important role in host defense against viral infection and carcinogenesis, we provide a brief review of STAT2 activity regulation and discuss the novel role of STAT2 activity regulation in carcinogenesis, especially melanoma.

STAT2 among STAT proteins in carcinogenesis

The Janus kinase (JAK)–STAT pathway plays a crucial role in signal transduction and cellular responses to various cytokines. Immediately after the first direct linkage between STAT protein and carcinoma in humans was discovered, based on the constitutive activation of STAT3 playing a key role in the carcinogenesis of head and neck cancer and in multiple myeloma cells11,12, research on the involvement of STAT proteins in human cancers has been logarithmically expanded in recent decades. Subsequent research has revealed that several types of solid tumors, including leukemia and lymphomas, are linked with the constitutive activation of STAT3. Interleukin (IL)-6 (IL-6) autocrine or paracrine loops have been recognized inducers of constitutive STAT3 activity in myeloma and prostate malignant cell lines13. Moreover, the role of STAT proteins is not limited to cytokines. For example, transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α)-mediated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling was shown to play a vital role in the activation of STAT3 in certain head and neck cancer cell lines12, and growth factor-mediated receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathways such as that of the hepatocyte growth factor signaling via receptor c-MET were shown to be related to the transformation of leiomyosarcoma cells, breast carcinoma cells, melanoma cells, and lung cancer cells in conjunction with SRC kinase, which stimulates the expression of STAT314–17. On the other hand, evidence indicating that the antagonization of STAT3 signaling induces cell death in human U266 myeloma cells11 provides a good reason to develop STAT inhibitors as key tools to treat human cancers. Although STAT proteins play an essential role in cancer, research in the fields of immunology and oncology has mainly focused on STAT1/3.

STAT2, another member of the STAT family, is considered a hallmark of INF-I (IFNα/β) IFN-III (IFNλ1)/IL-29, IFNλ2/IL-28A, and IFNλ3/IL-28B activation18. The responsiveness of immune and nonimmune cells to INF-I and -III is known as the classic trigger for the formation of a heterotrimer complex known as ISGF3, comprising STAT2, STAT1, and interferon regulatory factor 9 (IRF9). Since STAT2 is distinct from other members of the STAT family in that it does not form a homodimer to recognize a DNA target, the formation of the heterotrimeric ISGF3 complex is a unique characteristic among STAT-dependent pathways. However, alternative STAT complexes composed of homo- and heterodimers of other STAT family members are known to form upon IFN-I stimulation in a cell-specific fashion19,20. Since keratinocytes are not only a mechanical barrier to outside invaders but also immunocompetent cells that can produce various inflammatory cytokines, ultraviolet irradiation has been used to shown a dramatically increased production of IL-1, -3, and -6, tumor necrosis factor, and granulocyte/macrophage-colony stimulating factor by these epidermal cells21. Our research group reported that STAT2 protein levels are higher in melanoma tissues than in normal skin tissues. Melanoma cell proliferation is also correlated with STAT2 protein levels, indicating that STAT2 activity plays an essential role in melanoma promotion. In summary, the important finding is that STAT2 stability regulation is directly involved in melanoma cell proliferation22. Moreover, the interaction of STAT2 with FBXW7 is stimulated by ultraviolet B (UVB) irradiation, resulting in a reduction in STAT2 protein. Notably, genetic deprivation induced by sh-RNA STAT2 suppressed SK-MEL-28 cell proliferation, whereas ectopic overexpression of STAT2 enhanced SK-MEL-2 cell proliferation. These results also support our conclusion that STAT2 is a key player in the regulation of melanoma promotion.

Functional anatomy of STAT2

Roles of STAT2 domains

The STAT family consists of seven transcription factors, each of which contains seven structurally and functionally conserved domains: N-terminal domain (NTD), coiled-coil domain (CCD), DNA-binding domain (DBD), linker domain (LD), Src-homology 2 domain (SH2D), tyrosine-phosphorylation site (pY), and transcriptional activation domain (TAD)23. Among these domains several regions have highly homologous amino acid sequences, including SH2D, which is involved in the activation and dimerization of STAT proteins24,25, DBD26, and a transactivation domain located in the carboxyl terminus27,28.

In terms of amino acid alignment, STAT2 is the longest and largest isotype among human STAT family members, with a molecular weight of 113 kDa consisting of 851 amino acid residues, whereas mouse STAT2 is even longer and larger, consisting of 923 amino acid residues and with a molecular weight of 130 kDa29. Despite the structural differences between humans and mouse STAT2, responsiveness to IFNα stimulation was fully restored in human STAT2-knockout cells by the introduction of mouse STAT230. This functional compensation provided by mouse STAT2 is also corroborated by a report indicating that the overexpression of human STAT2 in STAT2-deficient mouse fibroblasts was shown to complement defects in IFN-I signaling31. These results indicate that the role of STAT2 in physiological conditions is functionally unique and well conserved.

Scientists initially believed that STAT proteins were monomers prior to their activation by tyrosine phosphorylation. However, accumulating structural and functional evidence indicates that multiple unphosphorylated STAT proteins (U-STATs) already exist as dimers in living cells. The NTD (1–130 amino acid residues) of STAT2 consists of eight short α-helices and is involved in the formation of U-STAT dimers with anti-parallel conformations (Fig. 2)32. As SH2Ds of STAT proteins have been shown to interact upon tyrosine phosphorylation33, it is generally well accepted that tyrosine phosphorylation of SH2D is indispensable for homo- or heterodimerization, nuclear localization and DNA binding. Importantly, STAT1/2 proteins lacking tyrosine phosphorylation are still able to combine with IRF9 to form unphosphorylated ISGF3 (U-ISGF3), which sustains the transcription of approximately one-quarter of the initially induced ISGs during the late phase response to IFN-I34. Moreover, STAT activity is generally regulated at the N-terminal region by the formation of STAT tetramers35 and tyrosine dephosphorylation36. Thus, the literature strongly suggests that the NTD of STAT2 plays a role in the basal transcriptional expression of ISG.

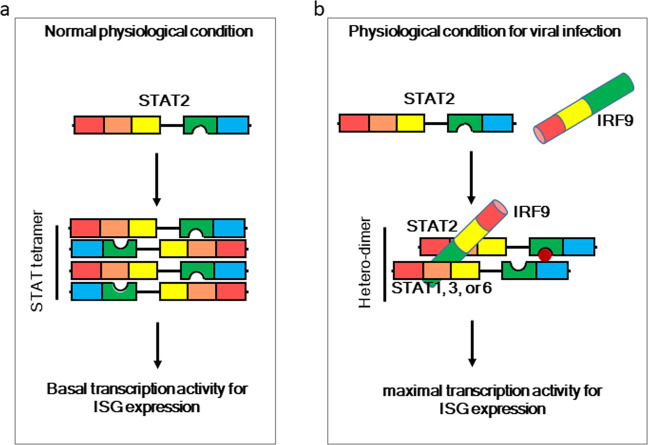

Fig. 2. Representative regulatory mechanisms of STAT2-mediated ISG expression.

a ISG expression under normal physiological conditions. Without stimulation, STAT2 forms a tetramer complex with other STAT family members, including STAT1, 3, and 6, through their N-terminal domains, resulting in an anti-parallel structure. The complex induces basal expression of target genes. b ISG expression under physiological conditions after viral infection. When cells are infected with viruses, activated JAK1- and TYK2-mediated phosphorylation of STAT2 at tyrosine residues triggers the formation of a SH2–pTyr interaction-mediated homo- or heterodimer complex, which associates with IRF9 and results in the formation of the ISGF3 complex. The ISGF3 complex plays a key role in target gene expression in response to viral infection.

The CCD spanning amino acids (aa) 135–315 in STAT2 has a superhelical structure consisting of four α-helices wrapped around each other. The CCD mediates protein–protein interactions with IRF9, which is a member of the IRF family. The IRF family generally shares amino acid homology in the N-terminal DBD, which is characterized by a tryptophan repeat37. Moreover, a bipartite basic nuclear localization signal (NLS) in the DBD of IRF9 is recognized by importin-α adapter family proteins, including importins-α3, -α5, and -α738. CRM1/exportin 1-dependent nuclear export of various STAT proteins has been shown to be mediated through the CCD39. Thus, the CCD of STAT2 in conjunction with the carboxyl terminus of IRF9 plays a key role in the formation of the ISGF3 complex, resulting in the regulation of nuclear import and export by the formation of the importin-α:importin β1 complex38. Based on these data, the CCD of STAT2 plays a key role in ISGF3 complex formation and subcellular distribution by protein–protein interactions (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Characteristics and roles of STAT2 domains.

Each STAT2 domain plays a specific role in homo- or heterodimerization and ISG expression. The diverse stimuli from outside or inside cells induce posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination to induce structural changes, parallel or anti-parallel oriented homo- or heterodimers, nuclear or cytosolic localization, and DNA binding.

The STAT protein family consists of transcription factors that regulate target gene expression by recognizing and binding to promoter regions. The β-barrel structure of the DBD spanning aa 320–480 is a highly conserved structure among all STAT family members and is critical for binding to the regulatory γ-activated sequence (GAS) element in STAT-target genes. Since the STAT2 homodimer is unable to bind to GAS sites, alternative STAT2-containing ISRE- or GAS-binding complexes involved in IFN-I signaling are composed of STAT2-containing heterodimers, namely, STAT1/240, STAT2/341, and STAT2/642. The DBD domain of STAT2 contains a combined NLS/NES (nuclear export signal) that becomes active only upon phosphorylation-induced dimer formation43,44. Both CCD and DBD are also implicated in the interaction between U-STATs45. This collective evidence suggests that STAT proteins have functional diversity and are regulated by diverse intrinsic and extrinsic stimuli (Fig. 3).

The LD spanning aa 480–580 harbors mostly an α-helical structure and distinguishes the DBD from the SH2D that follows it. The relationship of LD with DBD and SH2D was recently investigated in terms of structural change, and the transcriptional activity of STAT proteins was found to be altered46. Recent studies have indicated that mutations of highly conserved residues in the LD of STAT1, such as K544A/E545A, fail to stimulate transcription because they release DNA more quickly than the tyrosine-phosphorylated dimer47,48. Based on these results, communication between the DBD and LD, as well as between the LD and SH2D, affects STAT functions such as DNA binding and transcriptional activation46. However, no evidence has been provided regarding the role of the LD in STAT2 (Fig. 3).

The STAT2 SH2D spanning aa 580–680 consists of a β-sheet surrounded by two α-helices and participates in STAT dimerization and receptor association by binding to phosphorylated tyrosine residues at a conserved arginine residue. The tyrosine residue of STAT2, Tyr690, located directly adjacent to SH2D plays an essential role in domain interactions with other STAT proteins, especially STAT127. IFN-II induces the activation of STAT1 through phosphorylation of Y701 by IFN receptor-associated JAK1 and JAK2, leading to dimerization and nuclear accumulation of STAT149. To interact with importin-5α50, the specific surface area produced by the newly formed and activated STAT1 dimer includes regions of the NTD51 and DBD52. Since tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT1 homodimers and STAT1–STAT2 heterodimers are rapidly imported to the nucleus, nuclear export is important in regulating the cellular localization of signaling proteins such as STAT proteins38. The DBD of STAT1 contains an NES that can function autonomously and appears to be masked when STAT1 dimers are bound to DNA38. Dephosphorylation in the nucleus releases STAT1 from DNA and exposes the NES to CRM1, resulting in the redistribution of STAT1 back to the cytoplasm38. Moreover, STAT2 is critical to the nuclear export of STAT2–IRF9 and ISGF3. Although STAT2 has been observed in the nucleus, we confirmed that STAT2 is predominantly located in the cytoplasm22. The other domain contained in IRF9 essential for interplay with the CCD of STAT2 is the IRF-association domain (Fig. 3).

The transcriptional activation domain (TAD), accounting for the unique transcriptional activity of STAT dimers upon binding to DNA, is located at the C-terminal end53,54. STAT2 together with STAT1 and IRF9 forms the ISGF3 complex in which TAD of STAT2 contributes without directly contacting DNA, whereas STAT1 stabilizes the complex by providing additional DNA contacts55. STAT2–TAD is required for ISGF3-directed activation of transcription56,57 and has been shown to bind and recruit transcriptional coactivators such as p300/CBP, GCN5, DRIP150, and pp3228,56. Moreover, a dominant NES in the C-terminus of STAT2 was shown to play a critical role in returning the STAT2–IRF9 complex back to the cytoplasm38. Although STAT2/IRF9 continually shuttles in and out of the nucleus, the U-STAT2 NES leads to its prominence in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3). Thus, the cytoplasmic localization of STAT2 dramatically changes following IFN-I and -III stimulation.

General activation mechanism of STAT2

IFNs are comprised of three main subfamilies designated type I, type II, and type III. Type I interferon (IFN-I) consists of IFNβ, IFNκ, IFNω, IFNε, and 13 subtypes of IFNα; type II interferon (IFN-II) consists of single IFNγ; and type III interferon (IFN-III) comprises IFNλ1, IFNλ2, IFNλ332,58, and IFNλ425. IFNs are mainly produced by plasmacytoid dendritic cells in response to stimulation of pattern recognition receptors, which are located on the cell surface, in the cytosol, and/or in endosomal compartments59, by microbial products or by foreign nucleic acids60.

The recognition and binding of IFNβ and all IFNα subtypes by a heterodimeric transmembrane receptor composed of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 subunits initiate a signaling cascade mediated through the JAK–STAT pathway. Binding of INF-I to its cognitive IFN receptor that is preassociated with receptor-associated kinases, TYK2 and JAK1, results in activation by transphosphorylation61. This signaling pathway is a canonical cascade that transduces many cytokine and growth factor activation signals to the nucleus to activate transcription factors to enhance the expression of target genes. JAKs are defined by seven Janus homology (JH) domains, termed JH1–7. JH1 is a kinase domain that plays an important function in JAK enzymatic activity and the phosphorylation of STAT proteins, and JH3–JH4 of JAKs share homology with SH2Ds29. Although many publications initially reported that STAT proteins are monomers prior to their activation by tyrosine phosphorylation, accumulating evidence supported by structural and functional analyses indicates the existence of U-STATs as dimers in living cells29. These conclusions are based on findings that SH2Ds do not participate in this type of dimerization; both ends of the dimer structure are distinct, with STAT dimers adopting an anti-parallel conformation through the NTD32,58.

Tyrosine-phosphorylation results in the reciprocal binding of one phosphorylated STAT to another, forming either a homo- or heterodimer. INF-I-induced phosphorylation of STAT proteins at tyrosine residues leads to the dimerization of STAT proteins via a mutual SH2–pTyr interaction-mediated parallel dimer conformation25,33. However, in this case, the NTD is dispensable. In the canonical pathway of IFN-I-induced signaling, the phosphorylation of STAT1 at Tyr701 and STAT2 at Tyr690 induces heterodimerization in the parallel conformation and the interaction with IRF9 to form the ISGF3 complex62. On the other hand, the ISRE sequence is recognized by a cellular factor in response to IFNα treatment63. Subsequent studies have revealed that this cellular factor (ISGF3 complex) consists of four existing peptides, three of which have molecular weights of 84, 91, and 113 kDa and are currently known as STAT1β, STAT1α, and STAT2, respectively64,65. Dimer formation is the critical step in nuclear translocation since the NLS is formed by parts of the dimerized STAT DBDs66. The ISGF3 complex is translocated into the nucleus, whereupon the ISGF3-containing STAT dimer binds to gene promoters, specifically the IFN-I-stimulated response element (ISRE), which harbors the consensus sequence AGTTTCN2TTTCN, leading to the activation of transcription of over 300 interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs)62.

Tyrosine phosphorylation

Upon the binding of INF-I to IFNARs, activated TYK2- and JAK1-mediated transphosphorylation of INFARs in the intracellular region create docking sites for STAT1 and STAT2. Docked STAT1 and STAT2 are then phosphorylated by JAK1 and TYK2 at tyrosine residues, which can trigger the formation of homo- or heterodimers mediated by the SH2–pTyr interaction, especially the phosphorylation of STAT1 at Tyr701 and STAT2 at Tyr690. The association of the STAT1–STAT2 heterodimer with IRF9 results in the formation of the ISGF3 complex62, which plays a key role in target gene expression in response to viral infection29 and cancer cell growth. On the other hand, an important role for tyrosine phosphorylation was observed upon the partial deletion of the TAD, harboring aa 800–832, in STAT2, as deletion of this region was found to abolish the transcriptional activity of ISGF356. Another study corroborates the possible phosphorylation of Thr800 and Tyr833 by STAT2-mediated ISGF3 activity67–69. Currently, although a mutation of Y833 to a phenylalanine residue was shown to impair the dimerization of STAT2–STAT4 induced by IFN-I68,69, the biological significance of Thr800 and Tyr833 in their phosphorylated states has not been elucidated.

Ser/Thr phosphorylation

In eukaryotes, serine and threonine phosphorylation is more common than tyrosine phosphorylation. Although tyrosine phosphorylation at the TAD of STAT proteins is a well-known event that plays an essential role in STAT localization and activity, serine phosphorylation also plays a key role in modulating the transcription factor function of STAT proteins. The mutation of Ser727 in STAT3 to alanine (STAT3–S727A) abrogates the DNA-binding ability of STAT3. S727–STAT1 phosphorylation is necessary for STAT1 homodimerization to induce a strong transcriptional response during IFN signaling70. Importantly, STAT1β, an alternative splicing product of STAT1, does not harbor Ser727 and is interchangeable with STAT1α for target gene expression. These results provide a key explanation for the role of STAT1 phosphorylation at Ser727, indicating that it is not involved in ISGF3-mediated ISG expression28. More recently, STAT2 phosphorylation at Ser595 was identified in a phosphoproteomic screening performed to identify the phosphorylation events in Jurkat cells responding to T-cell receptor activation71,72. Importantly, STAT2 Ser595 phosphorylation was not uniquely induced by T-cell receptor activation, indicating that other signaling pathways induce Ser595 phosphorylation, depending on the cellular context. Another phosphoproteomic study identified additional phosphorylation sites in STAT2, including Thr800 in human colorectal cancer tissues69. Computational prediction grafting revealed STAT2 phosphorylation sites at Thr597 and Tyr833, which are located in the C-terminus and are involved in heterodimerization with STAT4 by IFN-I stimulation67. The phosphorylation of another serine residue in STAT2 was identified by mass spectrometry, indicating that Ser287 phosphorylation of STAT2 is induced in response to IFNα treatment73. The mutation of STAT2-S287A enhances IFNα-mediated cell responsiveness, including cell growth inhibition, prolonged protection against vesicular stomatitis viral infection, and IFN-induced ISG expression73. Notably, the phosphomimetic mutation of STAT2-S287D results in opposite responsiveness, likely due to loss of function73. Three years later, the same research group found that STAT2 is phosphorylated at Ser734, resulting in a reduction in the IFNα-induced antiviral response74. The mutation of STAT2 at Ser734 was shown to enhance IFNα-driven antiviral responses compared to those driven by wild-type STAT2. Moreover, a small subset of IFN-I-stimulated genes was shown to be upregulated by IFNα to a greater degree in cells expressing S734A–STAT2 than in cells expressing wild-type STAT274. More recently, phosphorylation was found in the DBD of STAT2. The phosphorylation sites Ser381, Thr385, and S393 of STAT2 were confirmed by an in vitro kinase assay using wild-type and alanine-mutated STAT2 proteins, [γ-32p]ATP, and active GSK3α/β22. Importantly, GSK3α and GSK3β were found to phosphorylate STAT2 equally, resulting in the destabilization of STAT2 by ubiquitination22. These results suggest that the phosphorylation status of STAT2 is differentially regulated depending on the cellular context. Moreover, the kinases that phosphorylate serine and/or threonine residues in STAT2 have not been clearly elucidated.

Physiological roles of STAT2 in human cancer

Not all malignant cells manifest as fully fledged tumors, and not all tumors metastasize. The general consensus is that these outcomes are due to the activity of immune cells and immune-regulatory factors driven mainly by JAK–STAT signaling75. Nonspecific responses to tumor cells are thought to be mitigated by natural killer (NK) cells. Thus, the JAK–STAT pathway has been hypothesized to tightly regulate the development, maturation, activation, and function of NK cells75. Moreover, the cytotoxic and lytic functions of activated CD8+ T cells and NK cells are triggered and enhanced by IFNγ, indicating that INF-II plays a more direct role in tumor cell killing. However, the roles of interferons in cancer development remain controversial. In addition, since interleukins such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, tumor necrosis factors, and IFNs secreted by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are able to stimulate tumor cell proliferation, protect tumor cells from apoptosis, or promote angiogenesis and metastasis, the molecular mechanisms of these diverse effects of cytokines on cancer development and chemoresistance still need to be elucidated. For example, lung metastasis of melanoma and peritoneal dissemination of ovarian cancer are facilitated by IFNγ76,77. Furthermore, IFNγ promotes the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by IFIT5-mediated microRNA processing, resulting in renal cancer invasion78. Moreover, significant upregulation of several key effectors, including IFNGR1, IFNGR2, STAT1, and STAT2, in the IFNγ signaling pathway has been observed in metastatic renal cell carcinoma79. IL-6 is known to act as a protumorigenic cytokine by facilitating cell growth and anti-apoptosis in multiple myeloma80. As described above, STAT2 plays a fundamental role in ISGF3; the STAT2 homodimer can induce IL-6 gene expression either directly or as a part of the ISGF3 complex81. Several studies have shown that during the tumor initiation process, IL-6 is required in response to activated EGFR and K-RAS signaling82. In a STAT2-knockout mouse experiment, STAT2 deficiency was shown to inhibit colorectal carcinogenesis because of lower levels of inflammatory cytokines83,84, and mice lacking STAT2 but not STAT1 or IFNARs were found to be hypersensitive to LPS84. Moreover, the STAT2-mediated NF-κB signaling pathway additively supports carcinogenesis and cancer therapeutic drug resistance. For example, cells expressing the transactivation-deficient triple mutant p53-D281G (L22Q/W23S) were shown to exhibit enhanced cell growth, survival, and adhesion. Although a p53 mutant did not bind to the NF-κB2 promoter, STAT2 and CBP were found to be enriched at this promoter in p53-mutant H1299 cells but were not enriched in cells expressing wild-type p5385. In addition, some p53-mutant phenotypes show increased NF-κB2 expression86. The molecular mechanisms driving STAT2 participation in inflammatory responses were recently elucidated, and it was shown that the cooperation of IRF6-unphopshorylated STAT2-mediated NF-κB signaling drives IL-6 expression87. In addition, both IL-1α and IL-1β aggravate tumor angiogenesis and invasiveness via the induction of vascular endothelial cell growth factor and tumor necrosis factor88. However, the role of the STAT2-mediated signaling pathway in carcinogenesis has not been clearly defined. A recent publication provided further understanding of the physiological relevance of STAT2 protein levels in human cancers, especially melanoma proliferation22. The discovery of FBXW7 as a STAT2 stability regulator has deepened our understanding of the role of FBXW7 in human cancers. Approximately, 6% of all primary human cancers contain FBXW7 mutations, indicating that FBXW7 plays a tumor suppressive role89. When only melanoma cases are observed, the mutation rate of FBXW7 is increased to 8.1%90. Our study demonstrated that FBXW7 protein levels were significantly lower in melanoma tissues than in normal skin tissues22. In contrast, STAT2 protein levels were significantly elevated in melanoma tissues compared to normal skin tissues in humans22. This phenomenon was also observed when tissue array samples were expanded to include 10 normal skin tissues and 70 skin cancer tissues, including squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Importantly, a Kaplan–Meier analysis indicated that high levels of STAT2 protein may reduce the 5-year survival probability for melanoma patients22. Thus, the FBXW7–STAT2 metabolic axis might be a potential target for melanoma treatment.

STAT2 ubiquitination

Among posttranslational modifications, protein ubiquitination plays a key role in regulating diverse intracellular signaling pathways and biological processes91–93, including the mediation of host protection and cell growth, proliferation, and viability. While signaling to STAT1 and STAT2 is initiated and regulated through the transient activity induced by IFN stimulation, the extent of IFN signaling is tightly regulated at many levels to limit detrimental effects. Notably, ubiquitination is important in modulating IFN signaling94. The IFNAR1 chain of the IFN-I receptor is a key signaling mediator. The ubiquitination and degradation of IFNAR1 is mediated by a cullin-based E3 ubiquitin ligase95 via interactions with substrate-recognizing F-box proteins, such as βTrcP96. βTrcP tethering to the IFNAR1-SCFSKP1/Cullin1/Rbx1 complex facilitates the polyubiquitination of IFNAR1 predominantly within a cluster of three lysine residues97,98. In brief, a highly conserved Pro470 residue of human IFNAR1 following the endocytic motif induces a turn that orients the polypeptide chain of IFNAR1 in a position parallel to the membrane. This conformational change is induced by ubiquitination, resulting in the exposure, enhanced recognition and subsequent binding by AP50, which is a clathrin adaptor protein. Based on these observations, both Lys48- and Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains contribute significantly to IFNAR1 endocytosis and subsequent degradation98. Polyubiquitination-mediated internalized IFNAR1 might be degraded through the lysosomal degradation pathway98. In the absence of ubiquitination, this motif is masked by associated TYK2, thereby preventing basal endocytosis and degradation of IFNAR199,100. A key event in regulating IFNAR1 ubiquitination is its phosphorylation at specific serine residues following IFN-I engagement. One important clue to phosphorylation-mediated ubiquitination was found to be the recruitment of βTrcP and the remaining components of the E3 ubiquitin ligase, resulting in the ubiquitination at Lys501, Lys525, and Lys526 located proximal to the destruction motif97. The consequent increase in IFNAR1 ubiquitination and destabilization limits any further IFN responses.

The ubiquitination of STAT proteins was first reported by Kim et al.101, who found that IFN-γ-activated STAT1 regulates STAT1 protein levels via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Although it was reported that βTrcP-based E3 ubiquitin ligase may also be involved in the ubiquitination and degradation of STAT1 phosphorylated by extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) at Ser727102, the identities of the cellular E3 ubiquitin ligases that target STAT1 and STAT2 for ubiquitination, as well as the mechanisms regulating these events, remain poorly understood. Moreover, the extent of STAT2 stability regulation is not well defined, especially in relation to immune responses and carcinogenesis. Recently, understanding of the role of STAT2 in skin carcinogenesis was profoundly advanced. Specifically, a study found that an environmental stimulus, UVB, modulated STAT2 stability22. This is the first result showing that UVB stimulation induces protein–protein interactions between STAT2 and FBXW7, a member of the F-box protein family selectively recognizing target substrates. This mechanistic molecular study was able to demonstrate that GSK3β-induced phosphorylation of the DBD of STAT2, especially at residues Ser381, Thr385, and Ser393, created a recognition degron motif for FBXW7 by forming hydrogen bonds22. The physiological relevance of the UVB–STAT2–FBXW7 signaling axis in melanoma formation was investigated, and STAT2 and FBXW7 protein levels showed an inverse correlation in normal and skin cancer tissues (n = 77)22 (Fig. 4). Since most studies investigating the role of STAT2 have focused only on skin cancer, the various underlying roles of STAT2 in different cellular contexts have been easy to overlook. Moreover, protein–protein interactions induce dramatic conformational changes. Since JAK activation promotes subsequent tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT proteins that form transcriptionally active STAT1 homodimers or STAT1/STAT2/IRF9 complexes20, the importance of protein ubiquitination in regulating cytokine signaling and IFN-mediated STAT signaling is underscored by the propensity of tumor cells and viruses to hijack this mode of regulation to evade IFN control and interfere with the ability of a host to suppress malignant growth and viral replication103,104.

Fig. 4. New paradigm for the regulation of STAT2 protein in melanoma formation.

In normal cells, STAT2 protein levels are maintained at low levels. When cells are stimulated by UV, especially UVB, GSK3α/β phosphorylates STAT2 at the DBD, which recruits the SCFFBXW7 complex to form the SCFFBXW7–STAT2 complex. FBXW7 catalyzes K48 STAT2 polyubiquitination, resulting in a reduction in STAT2 protein levels via the proteasomal degradation pathway. Thus, cell proliferation at the acute stage is initially suppressed after UVB irradiation. However, in cancer cells with FBXW7 mutation(s), higher STAT2 protein levels are sustained compared to that of normal cells, resulting in the induction of cell proliferation.

Conclusion

The data indicate that STAT2 is a key player in ISG expression in response to IFN stimulation. The molecular mechanisms that modulate ISG expression have been continuously studied by focusing on host defense against foreign invaders such as viruses, and it has been shown that STAT2-associating ISGF3 complexes play essential roles in immune responses, including the activation of immune cells, immune cell propagation, and inflammatory cytokine production. Interestingly, the signaling pathway mediated by STAT2 has also been shown to participate in carcinogenesis, metastasis, and anticancer drug resistance. Moreover, several experimental data have strongly suggested that STAT2 is involved in carcinogenesis, including prostate cancer, renal cancer, leukemia, lymphomas, skin cancer, and melanoma. Regarding molecular mechanisms, although the regulation of STAT2 activity by posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation is a key event in the formation of the ISGF3 complex and its subcellular localization, a recent publication suggests that STAT2 protein regulation by ubiquitination-mediated proteasomal degradation is another way to elucidate STAT2 involvement in carcinogenesis. Finally, the identification of the extrinsic and intrinsic stimuli that induce STAT2-mediated carcinogenesis is important for understanding STAT2-mediated signaling in carcinogenesis.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Research Fund of The Catholic University of Korea (M-2020-B0002–00048) and the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning (NRF-2020R1A2B5B02001804 and NRF-2020R1A4A2002894).

Author contributions

C.J.L., H.J.A., H.C.K., J.Y.L., and H.S.L. primarily wrote the paper. E.S.C. performed the English editing. Y.Y.C. organized and supervised the paper writing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lawrence DW, Kornbluth J. E3 ubiquitin ligase NKLAM ubiquitinates STAT1 and positively regulates STAT1-mediated transcriptional activity. Cell Signal. 2016;28:1833–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka T, Soriano MA, Grusby MJ. SLIM is a nuclear ubiquitin E3 ligase that negatively regulates STAT signaling. Immunity. 2005;22:729–736. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ulane CM, Horvath CM. Paramyxoviruses SV5 and HPIV2 assemble STAT protein ubiquitin ligase complexes from cellular components. Virology. 2002;304:160–166. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulane CM, Rodriguez JJ, Parisien JP, Horvath CM. STAT3 ubiquitylation and degradation by mumps virus suppress cytokine and oncogene signaling. J. Virol. 2003;77:6385–6393. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.11.6385-6393.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcin D, Marq JB, Strahle L, le Mercier P, Kolakofsky D. All four Sendai Virus C proteins bind Stat1, but only the larger forms also induce its mono-ubiquitination and degradation. Virology. 2002;295:256–265. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le VTK, Trilling M, Wilborn M, Hengel H, Zimmermann A. Human cytomegalovirus interferes with signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 2 protein stability and tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Gen. Virol. 2008;89:2416–2426. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/001669-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashour J, Laurent-Rolle M, Shi PY, Garcia-Sastre A. NS5 of dengue virus mediates STAT2 binding and degradation. J. Virol. 2009;83:5408–5418. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02188-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramachandran A, Horvath CM. Paramyxovirus disruption of interferon signal transduction: STATus report. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29:531–537. doi: 10.1089/jir.2009.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pickart CM. Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:503–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bai C, et al. SKP1 connects cell cycle regulators to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through a novel motif, the F-box. Cell. 1996;86:263–274. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Catlett-Falcone R, et al. Constitutive activation of Stat3 signaling confers resistance to apoptosis in human U266 myeloma cells. Immunity. 1999;10:105–115. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grandis JR, et al. Requirement of Stat3 but not Stat1 activation for epidermal growth factor receptor- mediated cell growth In vitro. J. Clin. Investig. 1998;102:1385–1392. doi: 10.1172/JCI3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lou W, Ni Z, Dyer K, Tweardy DJ, Gao AC. Interleukin-6 induces prostate cancer cell growth accompanied by activation of stat3 signaling pathway. Prostate. 2000;42:239–242. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(20000215)42:3<239::aid-pros10>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang YW, Wang LM, Jove R, Vande Woude GF. Requirement of Stat3 signaling for HGF/SF-Met mediated tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2002;21:217–226. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaido T, Oe H, Imamura M. Interleukin-6 augments hepatocyte growth factor-induced liver regeneration; involvement of STAT3 activation. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1667–1670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hung W, Elliott B. Co-operative effect of c-Src tyrosine kinase and Stat3 in activation of hepatocyte growth factor expression in mammary carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:12395–12403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia R, et al. Constitutive activation of Stat3 by the Src and JAK tyrosine kinases participates in growth regulation of human breast carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2001;20:2499–2513. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fink K, Grandvaux N. STAT2 and IRF9: beyond ISGF3. JAKSTAT. 2013;2:e27521. doi: 10.4161/jkst.27521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delgoffe GM, Vignali DA. STAT heterodimers in immunity: a mixed message or a unique signal? JAKSTAT. 2013;2:e23060. doi: 10.4161/jkst.23060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Platanias LC. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:375–386. doi: 10.1038/nri1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarz T, Luger TA. Effect of UV irradiation on epidermal cell cytokine production. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 1989;4:1–13. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(89)80097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee CJ, et al. FBXW7-mediated stability regulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 in melanoma formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:584–594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1909879116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kisseleva T, Bhattacharya S, Braunstein J, Schindler CW. Signaling through the JAK/STAT pathway, recent advances and future challenges. Gene. 2002;285:1–24. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu XY, Zhang JJ. Transcription factor p91 interacts with the epidermal growth factor receptor and mediates activation of the c-fos gene promoter. Cell. 1993;74:1135–1145. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90734-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shuai K, et al. Interferon activation of the transcription factor Stat91 involves dimerization through SH2-phosphotyrosyl peptide interactions. Cell. 1994;76:821–828. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bluyssen HA, Levy DE. Stat2 is a transcriptional activator that requires sequence-specific contacts provided by stat1 and p48 for stable interaction with DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:4600–4605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shuai K, Stark GR, Kerr IM, Darnell JE., Jr. A single phosphotyrosine residue of Stat91 required for gene activation by interferon-gamma. Science. 1993;261:1744–1746. doi: 10.1126/science.7690989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muller M, et al. Complementation of a mutant cell line: central role of the 91 kDa polypeptide of ISGF3 in the interferon-alpha and -gamma signal transduction pathways. EMBO J. 1993;12:4221–4228. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blaszczyk K, et al. The unique role of STAT2 in constitutive and IFN-induced transcription and antiviral responses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016;29:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paulson M, et al. Stat protein transactivation domains recruit p300/CBP through widely divergent sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:25343–25349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen LS, et al. STAT2 hypomorphic mutant mice display impaired dendritic cell development and antiviral response. J. Biomed. Sci. 2009;16:22. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luker KE, et al. Kinetics of regulated protein-protein interactions revealed with firefly luciferase complementation imaging in cells and living animals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12288–12293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404041101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levy DE, Darnell JE., Jr. Stats: transcriptional control and biological impact. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:651–662. doi: 10.1038/nrm909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheon H, et al. IFNbeta-dependent increases in STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9 mediate resistance to viruses and DNA damage. EMBO J. 2013;32:2751–2763. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu X, Sun YL, Hoey T. Cooperative DNA binding and sequence-selective recognition conferred by the STAT amino-terminal domain. Science. 1996;273:794–797. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shuai K, Liao J, Song MM. Enhancement of antiproliferative activity of gamma interferon by the specific inhibition of tyrosine dephosphorylation of Stat1. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996;16:4932–4941. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamura T, Yanai H, Savitsky D, Taniguchi T. The IRF family transcription factors in immunity and oncogenesis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008;26:535–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banninger G, Reich NC. STAT2 nuclear trafficking. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:39199–39206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Begitt A, Meyer T, van Rossum M, Vinkemeier U. Nucleocytoplasmic translocation of Stat1 is regulated by a leucine-rich export signal in the coiled-coil domain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:10418–10423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190318397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brierley MM, Fish EN. Functional relevance of the conserved DNA-binding domain of STAT2. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:13029–13036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500426200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghislain JJ, Wong T, Nguyen M, Fish EN. The interferon-inducible Stat2:Stat1 heterodimer preferentially binds in vitro to a consensus element found in the promoters of a subset of interferon-stimulated genes. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2001;21:379–388. doi: 10.1089/107999001750277853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta S, Jiang M, Pernis AB. IFN-alpha activates Stat6 and leads to the formation of Stat2:Stat6 complexes in B cells. J. Immunol. 1999;163:3834–3841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melen K, Kinnunen L, Julkunen I. Arginine/lysine-rich structural element is involved in interferon-induced nuclear import of STATs. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:16447–16455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fagerlund R, Melen K, Kinnunen L, Julkunen I. Arginine/lysine-rich nuclear localization signals mediate interactions between dimeric STATs and importin alpha 5. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:30072–30078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202943200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mertens C, et al. Dephosphorylation of phosphotyrosine on STAT1 dimers requires extensive spatial reorientation of the monomers facilitated by the N-terminal domain. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3372–3381. doi: 10.1101/gad.1485406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mertens C, Haripal B, Klinge S, Darnell JE. Mutations in the linker domain affect phospho-STAT3 function and suggest targets for interrupting STAT3 activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:14811–14816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515876112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang E, Wen Z, Haspel RL, Zhang JJ, Darnell JE., Jr. The linker domain of Stat1 is required for gamma interferon-driven transcription. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999;19:5106–5112. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.5106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang E, Henriksen MA, Schaefer O, Zakharova N, Darnell JE., Jr. Dissociation time from DNA determines transcriptional function in a STAT1 linker mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:13455–13462. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Green DS, Young HA, Valencia JC. Current prospects of type II interferon gamma signaling and autoimmunity. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:13925–13933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.774745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sekimoto T, Imamoto N, Nakajima K, Hirano T, Yoneda Y. Extracellular signal-dependent nuclear import of Stat1 is mediated by nuclear pore-targeting complex formation with NPI-1, but not Rch1. EMBO J. 1997;16:7067–7077. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meissner T, Krause E, Lodige I, Vinkemeier U. Arginine methylation of STAT1: a reassessment. Cell. 2004;119:587–589. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meyer T, Begitt A, Lodige I, van Rossum M, Vinkemeier U. Constitutive and IFN-gamma-induced nuclear import of STAT1 proceed through independent pathways. EMBO J. 2002;21:344–354. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.3.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horvath CM, Wen Z, Darnell JE., Jr A STAT protein domain that determines DNA sequence recognition suggests a novel DNA-binding domain. Genes Dev. 1995;9:984–994. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schindler C, Levy DE, Decker T. JAK-STAT signaling: from interferons to cytokines. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:20059–20063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martinez-Moczygemba M, Gutch MJ, French DL, Reich NC. Distinct STAT structure promotes interaction of STAT2 with the p48 subunit of the interferon-alpha-stimulated transcription factor ISGF3. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:20070–20076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qureshi SA, Leung S, Kerr IM, Stark GR, Darnell JE., Jr. Function of Stat2 protein in transcriptional activation by alpha interferon. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996;16:288–293. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park C, Lecomte MJ, Schindler C. Murine Stat2 is uncharacteristically divergent. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4191–4199. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.21.4191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Neculai D, et al. Structure of the unphosphorylated STAT5a dimer. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:40782–40787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pichlmair A, Reis e Sousa C. Innate recognition of viruses. Immunity. 2007;27:370–383. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koyama S, Ishii KJ, Coban C, Akira S. Innate immune response to viral infection. Cytokine. 2008;43:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steen HC, Gamero AM. STAT2 phosphorylation and signaling. JAKSTAT. 2013;2:e25790. doi: 10.4161/jkst.25790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haque SJ, Williams BR. Identification and characterization of an interferon (IFN)-stimulated response element-IFN-stimulated gene factor 3-independent signaling pathway for IFN-alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:19523–19529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Levy DE, Kessler DS, Pine R, Reich N, Darnell JE., Jr Interferon-induced nuclear factors that bind a shared promoter element correlate with positive and negative transcriptional control. Genes Dev. 1988;2:383–393. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schindler C, Fu XY, Improta T, Aebersold R, Darnell JE., Jr Proteins of transcription factor ISGF-3: one gene encodes the 91-and 84-kDa ISGF-3 proteins that are activated by interferon alpha. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:7836–7839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fu XY, Schindler C, Improta T, Aebersold R, Darnell JE., Jr. The proteins of ISGF-3, the interferon alpha-induced transcriptional activator, define a gene family involved in signal transduction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:7840–7843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meyer T, Vinkemeier U. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of STAT transcription factors. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271:4606–4612. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Farrar JD, et al. Selective loss of type I interferon-induced STAT4 activation caused by a minisatellite insertion in mouse Stat2. Nat. Immunol. 2000;1:65–69. doi: 10.1038/76932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hornbeck PV, et al. PhosphoSitePlus: a comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D261–D270. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shiromizu T, et al. Identification of missing proteins in the neXtProt database and unregistered phosphopeptides in the PhosphoSitePlus database as part of the Chromosome-centric Human Proteome Project. J. Proteome Res. 2013;12:2414–2421. doi: 10.1021/pr300825v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wen Z, Zhong Z, Darnell JE., Jr Maximal activation of transcription by Stat1 and Stat3 requires both tyrosine and serine phosphorylation. Cell. 1995;82:241–250. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ng SL, et al. IkappaB kinase epsilon (IKK(epsilon)) regulates the balance between type I and type II interferon responses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:21170–21175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119137109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mayya V, et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of T cell receptor signaling reveals system-wide modulation of protein-protein interactions. Sci. Signal. 2009;2:ra46. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Steen HC, et al. Identification of STAT2 serine 287 as a novel regulatory phosphorylation site in type I interferon-induced cellular responses. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:747–758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.402529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Steen HC, et al. Phosphorylation of STAT2 on serine-734 negatively regulates the IFN-alpha-induced antiviral response. J. Cell Sci. 2016;129:4190–4199. doi: 10.1242/jcs.185421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Owen KL, Brockwell NK, Parker BS. JAK-STAT Signaling: A Double-Edged Sword of Immune Regulation and Cancer Progression. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:2002. doi: 10.3390/cancers11122002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Taniguchi K, et al. Interferon gamma induces lung colonization by intravenously inoculated B16 melanoma cells in parallel with enhanced expression of class I major histocompatibility complex antigens. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:3405–3409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abiko K, et al. IFN-gamma from lymphocytes induces PD-L1 expression and promotes progression of ovarian cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2015;112:1501–1509. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lo UG, et al. IFNgamma-induced IFIT5 promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in prostate cancer via miRNA processing. Cancer Res. 2019;79:1098–1112. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Au-Yeung N, Mandhana R, Horvath CM. Transcriptional regulation by STAT1 and STAT2 in the interferon JAK-STAT pathway. JAKSTAT. 2013;2:e23931. doi: 10.4161/jkst.23931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Harmer D, Falank C, Reagan MR. Interleukin-6 interweaves the bone marrow microenvironment, bone loss, and multiple myeloma. Front. Endocrinol. 2018;9:788. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Blaszczyk K, et al. STAT2/IRF9 directs a prolonged ISGF3-like transcriptional response and antiviral activity in the absence of STAT1. Biochem. J. 2015;466:511–524. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ancrile B, Lim KH, Counter CM. Oncogenic Ras-induced secretion of IL6 is required for tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1714–1719. doi: 10.1101/gad.1549407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gamero AM, et al. STAT2 contributes to promotion of colorectal and skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Prev. Res. 2010;3:495–504. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Alazawi W, et al. Stat2 loss leads to cytokine-independent, cell-mediated lethality in LPS-induced sepsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:8656–8661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221652110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Scian MJ, et al. Tumor-derived p53 mutants induce NF-kappaB2 gene expression. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:10097–10110. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.22.10097-10110.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vaughan CA, et al. p53 mutants induce transcription of NF-kappaB2 in H1299 cells through CBP and STAT binding on the NF-kappaB2 promoter and gain of function activity. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012;518:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nan J, Wang Y, Yang J, Stark GR. IRF9 and unphosphorylated STAT2 cooperate with NF-kappaB to drive IL6 expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:3906–3911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1714102115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Voronov E, et al. IL-1 is required for tumor invasiveness and angiogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:2645–2650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437939100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Akhoondi S, et al. FBXW7/hCDC4 is a general tumor suppressor in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9006–9012. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Aydin IT, et al. FBXW7 mutations in melanoma and a new therapeutic paradigm. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju107. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen ZJ. Ubiquitin signalling in the NF-kappaB pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:758–765. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.de Bie P, Ciechanover A. Ubiquitination of E3 ligases: self-regulation of the ubiquitin system via proteolytic and non-proteolytic mechanisms. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:1393–1402. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kirkin V, Dikic I. Ubiquitin networks in cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2011;21:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huangfu WC, Fuchs SY. Ubiquitination-dependent regulation of signaling receptors in cancer. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:725–734. doi: 10.1177/1947601910382901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kumar KG, et al. SCF(HOS) ubiquitin ligase mediates the ligand-induced down-regulation of the interferon-alpha receptor. EMBO J. 2003;22:5480–5490. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fuchs SY, Spiegelman VS, Kumar KG. The many faces of beta-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligases: reflections in the magic mirror of cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:2028–2036. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kumar KG, Krolewski JJ, Fuchs SY. Phosphorylation and specific ubiquitin acceptor sites are required for ubiquitination and degradation of the IFNAR1 subunit of type I interferon receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:46614–46620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407082200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kumar KG, et al. Site-specific ubiquitination exposes a linear motif to promote interferon-alpha receptor endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 2007;179:935–950. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kumar KG, et al. Basal ubiquitin-independent internalization of interferon alpha receptor is prevented by Tyk2-mediated masking of a linear endocytic motif. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:18566–18572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800991200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ragimbeau J, et al. The tyrosine kinase Tyk2 controls IFNAR1 cell surface expression. EMBO J. 2003;22:537–547. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kim TK, Maniatis T. Regulation of interferon-gamma-activated STAT1 by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Science. 1996;273:1717–1719. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5282.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Soond SM, et al. ERK and the F-box protein betaTRCP target STAT1 for degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:16077–16083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800384200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 103.Fuchs SY. The role of ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in oncogenic signaling. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2002;1:337–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Viswanathan K, Fruh K, DeFilippis V. Viral hijacking of the host ubiquitin system to evade interferon responses. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2010;13:517–523. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]