Abstract

Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease is an autosomal dominant hereditary tumour susceptibility disease caused by germline pathogenic variation of the VHL tumour suppressor gene. Affected individuals are at risk of developing multiple malignant and benign tumours in a number of organs.

In this report, a male patient in his 20s who presented to the Urologic Oncology Branch at the National Cancer Institute with a clinical diagnosis of VHL was found to have multiple cerebellar haemangioblastomas, bilateral epididymal cysts, multiple pancreatic cysts, and multiple, bilateral renal tumours and cysts. The patient had no family history of VHL and was negative for germline VHL mutation by standard genetic testing. Further genetic analysis demonstrated a germline balanced translocation between chromosomes 1 and 3, t(1;3)(p36.3;p25) with a breakpoint on chromosome 3 within the second intron of the VHL gene. This created a pathogenic germline alteration in VHL by a novel mechanism that was not detectable by standard genetic testing.

Karyotype analysis is not commonly performed in existing genetic screening protocols for patients with VHL. Based on this case, protocols should be updated to include karyotype analysis in patients who are clinically diagnosed with VHL but demonstrate no detectable mutation by existing genetic testing.

Keywords: urology, human genetics, genetic testing, cytogenetic analysis, chromosome aberrations

Introduction

Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease is an autosomal-dominant hereditary tumour susceptibility disease where patients are at increased risk of developing multiple malignant and benign tumours in a number of organs. Patients affected with VHL are at risk for the development retinal haemangiomas, central nervous system (CNS) haemangioblastomas, clear cell renal cell carcinomas (ccRCC) and renal cysts, pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours, endolymphatic sac tumours, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours and epididymal and broad ligament cystadenomas.1 The genetic cause of VHL was identified as germline mutation of the VHL tumour suppressor gene.2

An individual with a family history of VHL can be diagnosed if they present with a single VHL-associated tumour, such as a retinal or cerebellar haemangioblastoma or a renal cell carcinoma (RCC). To receive a positive diagnosis, individuals with no family history of VHL must present with two or more retinal or cerebellar haemangioblastomas, or a single haemangioblastoma and a visceral tumour.3–5 Mutational analysis of the VHL gene is important for diagnosis of VHL as it allows for presymptomatic identification of mutation-positive at-risk individuals. This enables optimal surveillance of these patients allowing for the early detection of tumours and timely surgical or therapeutic intervention.

Germline VHL mutations have been identified in over 900 families worldwide. Numerous mutation types have been observed including single nucleotide substitutions, small insertion–deletion mutations, splice site mutations and larger deletions resulting in partial or complete loss of the VHL gene and these data can be found in the UMD-VHL mutations database (http://www.umd.be/VHL/).6–10 Current Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA)-based genetic testing has a very high detection rate of germline VHL sequence alterations in patients with VHL, but to date, germline chromosomal translocation has not been reported in association with VHL.11 12 Germline translocations involving chromosome 3 have been reported that occur away from the VHL locus, but these patients present with bilateral and multifocal ccRCC and show no evidence of susceptibility to other VHL-associated tumours.13–16

This report presents a patient with no family history of VHL, who had multiple VHL-associated phenotypic features consistent with a clinical diagnosis of VHL, but who had no discernable germline sequence alteration of the VHL gene detected by standard genetic testing. Further in-depth genomic analysis demonstrated the first example of a germline-balanced chromosomal translocation of chromosomes 1 and 3 in which the breakpoint occurred within the VHL gene, resulting in a novel genetic mechanism for VHL.

Materials and methods

Patient material procurement and consent

This patient was seen at the Urologic Oncology Branch (UOB) of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institutes of Health (NIH) for clinical assessment.

CLIA evaluation of VHL mutation and patient karyotype

Patient blood DNA was evaluated for VHL gene mutation or deletion/duplication by GeneDx (GeneDx, Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA), a CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments) approved facility, and the CLIA karyotype analysis was performed by Quest Diagnostics (Quest Diagnostics, Chantilly, Virginia, USA).

Germline nucleic acid extraction

Germline DNA from the patient’s blood, saliva and skin samples were extracted using a Promega Maxwell 16 Blood DNA Purification Kit or Tissue DNA Purification Kit following manufacturer’s protocol (Promega, Wisconsin, USA). DNA concentration and purity were evaluated using a NanoDrop 2000 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA).

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS)

The DNA from the patient was pooled with 11 other WGS samples and sequenced on HiSeq4000 using Illumina TruSeq Nano DNA Library Prep and paired-end sequencing for three runs. The HiSeq Real Time Analysis software (RTA 1.18) was used for processing image files, and the Illumina bcl2fastq v1.8.4 was used to demultiplex and convert binary base calls and qualities to fastq format. The samples had 513 to 948 million pass filter reads with base call quality above 77% of bases having Q30 and above. Adapters and low-quality bases in raw reads were trimmed using Cutadapt v1.18 before alignment with the reference genome (Human—hg19) using BWA v0.7.10. The average mapping rate of all samples was approximately 98% and the average sequencing genome coverage was 30×. The samples had 89%–93% non-duplicate reads and the GC content of mapped reads ranged from 39% to 40%.

WGS analysis

Germline variants were called using GATK’s HaplotypeCaller in joint genotyping mode. Variants were then filtered for quality with the following criteria: QD (quality by depth) <2.0, FS (Fisher strand) >60.0, MQ (mapping quality) <40.0, MQRankSum <−12.5, ReadPosRankSum <−8.0 for SNPs; QD <2.0, FS >200.0, ReadPosRankSum <−20.0 for INDELs (insertions or deletions of bases in the DNA). To prioritise cancer-related germline variants, we used the Cancer Predisposition Sequencing Reporter (version 0.5.1) to analyse the 218 manually curated cancer predisposition genes (Panel 0) for known or predicted pathogenic variants. Structural variants were called using Manta in paired germline mode and annotated using AnnotSV. Alignments around candidate translocation events were further reviewed using IGV (Integrative Genomics Viewer).

PCR and Sanger DNA sequencing

PCR primers were designed on either side of the two potential breakpoint regions on the derivative versions of chromosomes 1 and 3 identified by WGS. The primer pairs used to amplify and sequence the translocation breakpoints were the following: chr1F (GAGTCATACATCAACCTCTAG)/chr3R (TGAGAATGAGACACTTTGAAAC), and chr3F (CTCAGCTAGGCAGTTACTCT)/chr1R (CAAGGATTCTTTTCAGCCTTC). DNA sequencing was performed by PCR using a Qiagen Taq PCR Core Kit (Qiagen, Maryland, USA) according to the manufacturer’s specifications, followed by bidirectional sequencing using the Big Dye Terminator v.1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, California, USA) according to the manufacturer’s specifications and run on an ABI 3130xl or 3730 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The three VHL coding exons were also amplified and sequenced using conventional methods. Sanger sequencing was conducted at the CCR Genomics Core at the NCI, NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. Forward and reverse sequences were evaluated using Sequencher 5.0.1 (Genecodes, Michigan, USA).

Results

A male patient in his 20s initially presented to the UOB at the NCI with several clinical phenotypic manifestations consistent with a diagnosis of VHL. At an outside institution, the patient had previously had multiple resections of CNS haemangioblastomas, a left robotic partial nephrectomy for multifocal ccRCC (five tumours ranging from 1.3 cm to 4.6 cm in largest dimension) and a right ablation of a central renal tumour. Previous germline mutation testing had been negative for VHL mutation and the patient reported no family history of kidney cancer or any other clinical manifestations consistent with VHL.

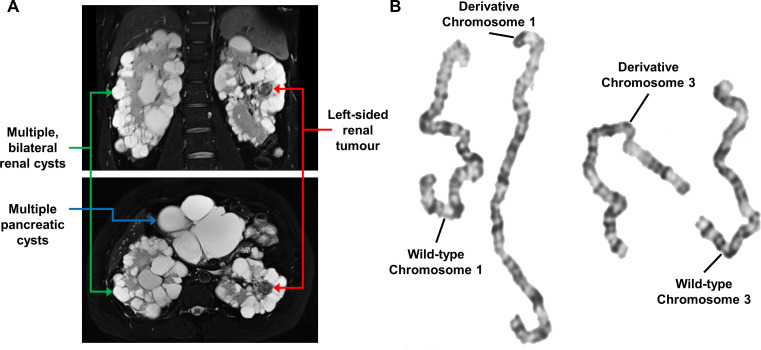

Further evaluation and imaging at the UOB revealed that the patient had bilateral epididymal cysts, numerous pancreatic cysts and numerous bilateral renal cysts with two solid lesions in the left kidney (2.3 cm and 1.7 cm) and one solid lesion in the right kidney (2.1 cm) (figure 1A). Currently, the adrenal glands appear unaffected. These clinical manifestations were consistent with a diagnosis of VHL. Germline genetic analysis was repeated using DNA derived from peripheral blood leucocytes to evaluate for point mutations, insertions, deletions or duplications in VHL and was negative. To assess the possibility of mosaicism, germline genetic testing was additionally performed on DNA derived from saliva containing buccal epithelial cells and from fibroblasts acquired via a skin punch biopsy. No alterations of the VHL gene were detected.

Figure 1.

Imaging and karyotype analysis of patient with von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease. (A) Coronal (upper) and axial (lower) MRI images of the abdomen of the patient with VHL showing multiple bilateral renal cysts (green arrows), one of the left-sided solid lesions (red arrows) and multiple pancreatic cysts (blue arrow). (B) Karyotype analysis of the germline DNA of the patient with VHL demonstrating a translocation between chromosomes 1 and 3.

Germline translocations involving chromosome 3 have been reported and shown to result in an increased risk of kidney cancer, but to date no other VHL-associated clinical manifestations have been seen.13–16 To investigate whether a translocation could cause these clinical features, a karyotype analysis was performed. The patient was shown to have a germline translocation between chromosomes 1 and 3, 46, XY, t(1;3)(p36.3;p25). The predicted breakpoint at chromosome 3p25 was in the same region as the VHL gene, potentially directly disrupting the VHL gene (figure 1B).

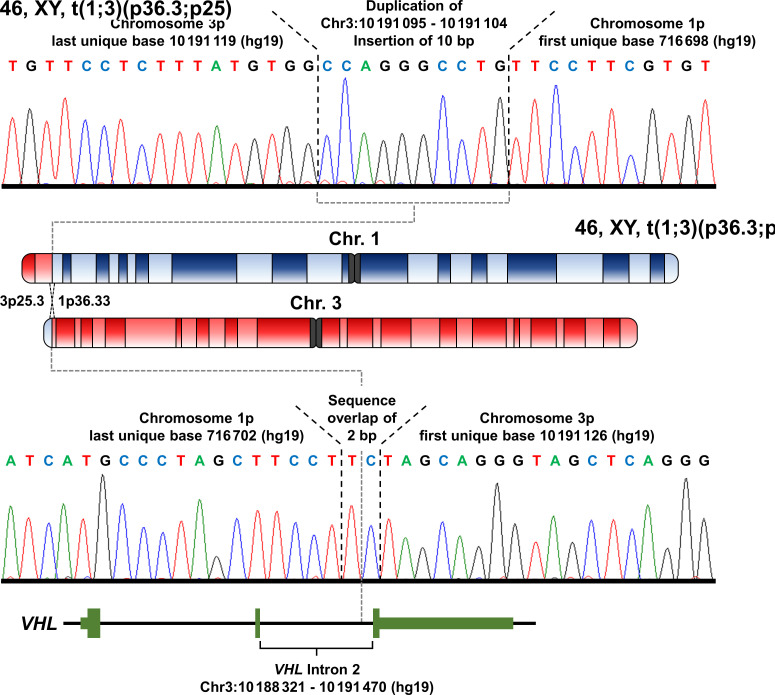

Paired-end WGS was performed on the DNA derived from peripheral blood leucocytes and several paired reads were found with one pair mate on chromosome 1 and the other within intron 2 of the VHL gene on chromosome 3. To confirm the breakpoints, primers were designed to amplify and Sanger sequence the breakpoint regions in both derivative chromosomes. The breakpoint on the derivative chromosome 3 had a 2 bp sequence present in both the wild-type sequences for chromosomes 1 and 3 with the last unique base of chromosome 1p at 716 702 bp (hg19) and the first unique base of chromosome 3p at 10 191 126 bp (hg19) (figure 2). The breakpoint on the derivative chromosome 1 had an insertion of 10 bp which was a duplication of an upstream region of chromosome 3, with the last unique base of chromosome 3p at 10,191,119 bp (hg19) and the first unique base of chromosome 1p at 716 698 bp (hg19) (figure 2). This results in a few base pairs being lost from wild-type sequence of chromosome 3 but no loss of sequence compared with wild-type chromosome 1. The break on chromosome 3p was confirmed to be within the second intron of the VHL gene creating a germline alteration that would result in either a truncated VHL protein or no protein being produced by this allele. However, the break on chromosome 1p did not occur within a gene, and the nearest telomeric gene, LOC100288069, was ~2.6 kb away and the nearest centromeric gene, FAM87B, was ~36 kb away. Neither of these genes were mutated in any of the 426 sporadic ccRCCs analysed by the Cancer Genome Atlas suggesting that alterations in either of these genes is unlikely to influence the risk of kidney cancer in this patient.

Figure 2.

Breakpoint mapping of germline translocation between chromosomes 1 and 3. Whole-genome sequencing identified the potential breakpoints on the derivative chromosomes resulting from the t(1;3)(p36.3;p25) translocation, and PCR primers were designed to amplify both breakpoint regions. Sanger sequencing of the resulting PCR products demonstrated the exact breakpoints on both derivative chromosomes. The breakpoint on the derivative chromosome 1 had an inserted 10 bp duplication of upstream chromosome 3 sequence, with the last unique base of chromosome 3p at 10 191 119 bp (hg19) and the first unique base of chromosome 1p at 716 698 bp (hg19). The breakpoint on the derivative chromosome 3 had a 2 bp sequence overlap with the last unique base of chromosome 1p at 716 702 bp and the first unique base of chromosome 3p at 10 191 126 bp (hg19). The breakpoint on chromosome 3p occurred within intron 2 of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene.

Discussion

The identification of patients with a clinical diagnosis of a disease, such as VHL, but no alteration in the known gene after standard genetic testing raises two questions. Are the current genetic tests unable to detect all the possible genetic abnormalities in the known gene or is there an alternative gene in which germline mutation produces the same clinical phenotype? An example of the first scenario would be a mutation within the intronic sequence that is not evaluated or detected by existing genetic tests and results in an aberrant splice event that inactivates the gene. This has previously been observed in patients with VHL from two separate studies in which a germline mutation was identified within the intron 1 of the VHL gene that created a cryptic exon.17 18 This cryptic exon (termed E1’) dysregulated VHL splicing and resulted in loss of protein expression and the germline mutation would not have been detected by standard genetic testing.17 18 Whereas, an example of the second scenario would be mutation of the TCEB1 gene which is another component of the VHL E3 ligase complex and has been reported as a potential mimic for VHL loss in sporadic ccRCC.19 20 This report identifies a germline translocation that disrupts the VHL gene as a novel mechanism of gene loss in VHL that would not be detected by standard genetic testing.

The patient reported here demonstrated a relatively typical presentation of the clinical features of VHL with no additional phenotypic features. The break on chromosome 3p obviously disrupted the VHL gene, but the break at the end of chromosome 1p did not occur within a gene. A significant number of germline VHL deletions have been reported in patients with VHL and the position of the breakpoints for these deletions frequently occur within DNA repeats, specifically Alu repeat regions.21 In our patient, the translocation breakpoint in the second intron of VHL on chromosome 3 occurred within an MLT1H long terminal repeat region (chr3:10 191 097-10 191 334) and ~30 bp upstream of an AluJo repeat (chr3:10 190 785-10 191 096), but the breakpoint on chromosome 1 was not near any DNA repeat region.

The patient had no family history of VHL suggesting than the germline translocation was a de novo event, but knowledge of this novel alteration will allow for screening of any subsequent offspring of the patient and confirmation of this de novo status. The patient can be managed by the current protocols for patients with VHL and counselled on the likelihood of any offspring inheriting VHL. In this specific case, the patient should also be counselled that a higher rate of miscarriage is associated with inheritance of a balanced translocations from either parent.22

Previous reports have identified patients with RCC with germline translocations involving chromosome 3 that occur away from the VHL locus and in these cases a three-hit model of carcinogenesis has been proposed.13–16 23 24 The first hit is the translocation and the second hit is loss of the derivative chromosome containing 3p and the VHL gene. The cells would then require a third hit to the remaining wild-type version of VHL.23 24 These patients tend to present with later onset of disease, due to the increased number of genetic events required, and only demonstrate bilateral and multifocal ccRCC with no evidence of the other VHL-associated tumours.13–16 23 24 The patient in this study would not require the loss of the derivative chromosome as the translocation through the gene is analogous to deletion of the VHL gene and the normal two-hit hypothesis would apply. Thus, the patient shows the expected early age of onset for ccRCC and a full spectrum of additional VHL-associated tumours.

The discovery of this novel mechanism for germline VHL gene inactivation highlights the importance of continual refinement of mutational screening protocols. The existing screening protocols for patients with VHL do not include a karyotype analysis, but this should now be considered in patients who are clinically diagnosed with VHL but demonstrate no detectable germline mutation by current genetic testing protocols.

Footnotes

Contributors: CJR, CDV and WML planed and coordinated the study. CJR, CDV, ML, XC, YZ, BT, MT, LSS, MWB and WML were involved in sequence data collection and interpretation. CJR, CDV, MWB and WML involved in clinical data collection. CJR, CDV, ML, BT, MT, LSS, MWB and WML wrote and edited the manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Programme of the NIH, NCI, Centre for Cancer Research, including grants ZIA BC011028, ZIA BC011038, ZIA BC011089 and ZIC BC011044. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the NCI, NIH, under contract HHSN261200800001E.

Disclaimer: The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organisations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

Ethics approval

The patient’s recruitment and tissue procurement and use were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer InstituteNCI on the NCI-97-C-0147 or NCI-89-C-0086 protocols.

References

- 1. Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M, Chew EY, Libutti SK, Linehan WM, Oldfield EH. Von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet 2003;361:2059–67. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13643-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Latif F, Tory K, Gnarra J, Yao M, Duh FM, Orcutt ML, Stackhouse T, Kuzmin I, Modi W, Geil L. Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science 1993;260:1317–20. 10.1126/science.8493574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Melmon KL, Rosen SW, Disease Lindau’s. Lindau's disease. review of the literature and study of a large kindred. Am J Med 1964;36:595–617. 10.1016/0002-9343(64)90107-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nielsen SM, Rhodes L, Blanco I, Chung WK, Eng C, Maher ER, Richard S, Giles RH. Von Hippel-Lindau disease: genetics and role of genetic counseling in a multiple neoplasia syndrome. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2172–81. 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.6140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choyke PL, Glenn GM, Walther MM, Patronas NJ, Linehan WM, Zbar B. Von Hippel-Lindau disease: genetic, clinical, and imaging features. Radiology 1995;194:629–42. 10.1148/radiology.194.3.7862955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen F, Kishida T, Yao M, Hustad T, Glavac D, Dean M, Gnarra JR, Orcutt ML, Duh FM, Glenn G. Germline mutations in the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene: correlations with phenotype. Hum Mutat 1995;5:66–75. 10.1002/humu.1380050109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zbar B, Kishida T, Chen F, Schmidt L, Maher ER, Richards FM, Crossey PA, Webster AR, Affara NA, Ferguson-Smith MA, Brauch H, Glavac D, Neumann HP, Tisherman S, Mulvihill JJ, Gross DJ, Shuin T, Whaley J, Seizinger B, Kley N, Olschwang S, Boisson C, Richard S, Lips CH, Lerman M. Germline mutations in the von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) gene in families from North America, Europe, and Japan. Hum Mutat 1996;8:348–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Béroud C, Joly D, Gallou C, Staroz F, Orfanelli MT, Junien C. Software and database for the analysis of mutations in the VHL gene. Nucleic Acids Res 1998;26:256–8. 10.1093/nar/26.1.256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maranchie JK, Afonso A, Albert PS, Kalyandrug S, Phillips JL, Zhou S, Peterson J, Ghadimi BM, Hurley K, Riss J, Vasselli JR, Ried T, Zbar B, Choyke P, Walther MM, Klausner RD, Linehan WM. Solid renal tumor severity in von Hippel Lindau disease is related to germline deletion length and location. Hum Mutat 2004;23:40–6. 10.1002/humu.10302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nordstrom-O'Brien M, van der Luijt RB, van Rooijen E, van den Ouweland AM, Majoor-Krakauer DF, Lolkema MP, van Brussel A, Voest EE, Giles RH. Genetic analysis of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Hum Mutat 2010;31:n/a–37. 10.1002/humu.21219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stolle C, Glenn G, Zbar B, Humphrey JS, Choyke P, Walther M, Pack S, Hurley K, Andrey C, Klausner R, Linehan WM. Improved detection of germline mutations in the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Hum Mutat 1998;12:417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hes FJ, van der Luijt RB, Janssen ALW, Zewald RA, de Jong GJ, Lenders JW, Links TP, Luyten GPM, Sijmons RH, Eussen HJ, Halley DJJ, Lips CJM, Pearson PL, van den Ouweland AMW, Majoor-Krakauer DF. Frequency of von Hippel-Lindau germline mutations in classic and non-classic von Hippel-Lindau disease identified by DNA sequencing, southern blot analysis and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Clin Genet 2007;72:122–9. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00827.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cohen AJ, Li FP, Berg S, Marchetto DJ, Tsai S, Jacobs SC, Brown RS. Hereditary renal-cell carcinoma associated with a chromosomal translocation. N Engl J Med 1979;301:592–5. 10.1056/NEJM197909133011107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Kessel AG, Wijnhoven H, Bodmer D, Eleveld M, Kiemeney L, Mulders P, Weterman M, Ligtenberg M, Smeets D, Smits A. Renal cell cancer: chromosome 3 translocations as risk factors. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:1159–60. 10.1093/jnci/91.13.1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Foster RE, Abdulrahman M, Morris MR, Prigmore E, Gribble S, Ng B, Gentle D, Ready S, Weston PMT, Wiesener MS, Kishida T, Yao M, Davison V, Barbero JL, Chu C, Carter NP, Latif F, Maher ER. Characterization of a 3;6 translocation associated with renal cell carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2007;46:311–7. 10.1002/gcc.20403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Takahashi M, Kahnoski R, Gross D, Nicol D, Teh BT. Familial adult renal neoplasia. J Med Genet 2002;39:1–5. 10.1136/jmg.39.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buffet A, Calsina B, Flores S, Giraud S, Lenglet M, Romanet P, Deflorenne E, Aller J, Bourdeau I, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Calatayud M, Dehais C, De Mones Del Pujol E, Elenkova A, Herman P, Kamenický P, Lejeune S, Sadoul JL, Barlier A, Richard S, Favier J, Burnichon N, Gardie B, Dahia PL, Robledo M, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P. Germline mutations in the new E1’ cryptic exon of the VHL gene in patients with tumours of von Hippel-Lindau disease spectrum or with paraganglioma. J Med Genet 2020;57:752–9. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2019-106519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lenglet M, Robriquet F, Schwarz K, Camps C, Couturier A, Hoogewijs D, Buffet A, Knight SJL, Gad S, Couvé S, Chesnel F, Pacault M, Lindenbaum P, Job S, Dumont S, Besnard T, Cornec M, Dreau H, Pentony M, Kvikstad E, Deveaux S, Burnichon N, Ferlicot S, Vilaine M, Mazzella J-M, Airaud F, Garrec C, Heidet L, Irtan S, Mantadakis E, Bouchireb K, Debatin K-M, Redon R, Bezieau S, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Teh BT, Girodon F, Randi M-L, Putti MC, Bours V, Van Wijk R, Göthert JR, Kattamis A, Janin N, Bento C, Taylor JC, Arlot-Bonnemains Y, Richard S, Gimenez-Roqueplo A-P, Cario H, Gardie B. Identification of a new VHL exon and complex splicing alterations in familial erythrocytosis or von Hippel-Lindau disease. Blood 2018;132:469–83. 10.1182/blood-2018-03-838235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sato Y, Yoshizato T, Shiraishi Y, Maekawa S, Okuno Y, Kamura T, Shimamura T, Sato-Otsubo A, Nagae G, Suzuki H, Nagata Y, Yoshida K, Kon A, Suzuki Y, Chiba K, Tanaka H, Niida A, Fujimoto A, Tsunoda T, Morikawa T, Maeda D, Kume H, Sugano S, Fukayama M, Aburatani H, Sanada M, Miyano S, Homma Y, Ogawa S. Integrated molecular analysis of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet 2013;45:860–7. 10.1038/ng.2699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ricketts CJ, De Cubas AA, Fan H, Smith CC, Lang M, Reznik E, Bowlby R, Gibb EA, Akbani R, Beroukhim R, Bottaro DP, Choueiri TK, Gibbs RA, Godwin AK, Haake S, Hakimi AA, Henske EP, Hsieh JJ, Ho TH, Kanchi RS, Krishnan B, Kwiatkowski DJ, Lui W, Merino MJ, Mills GB, Myers J, Nickerson ML, Reuter VE, Schmidt LS, Shelley CS, Shen H, Shuch B, Signoretti S, Srinivasan R, Tamboli P, Thomas G, Vincent BG, Vocke CD, Wheeler DA, Yang L, Kim WY, Robertson AG, Spellman PT, Rathmell WK, Linehan WM, Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network . The cancer genome atlas comprehensive molecular characterization of renal cell carcinoma. Cell Rep 2018;23:313–26. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Franke G, Bausch B, Hoffmann MM, Cybulla M, Wilhelm C, Kohlhase J, Scherer G, Neumann HPH. Alu-Alu recombination underlies the vast majority of large VHL germline deletions: molecular characterization and genotype-phenotype correlations in VHL patients. Hum Mutat 2009;30:776–86. 10.1002/humu.20948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kavalier F. Investigation of recurrent miscarriages. BMJ 2005;331:121–2. 10.1136/bmj.331.7509.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yusenko MV, Nagy A, Kovacs G. Molecular analysis of germline t(3;6) and t(3;12) associated with conventional renal cell carcinomas indicates their rate-limiting role and supports the three-hit model of carcinogenesis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2010;201:15–23. 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2010.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bodmer D, Eleveld MJ, Ligtenberg MJ, Weterman MA, Janssen BA, Smeets DF, de Wit PE, van den Berg A, van den Berg E, Koolen MI, Geurts van Kessel A. An alternative route for multistep tumorigenesis in a novel case of hereditary renal cell cancer and a t(2;3)(q35;q21) chromosome translocation. Am J Hum Genet 1998;62:1475–83. 10.1086/301888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]