Abstract

Endemic plants of the Khorassan-Kopet Dagh (KK) floristic province in northeastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan, and northwestern Afghanistan are often rare and range-restricted. Because of these ranges, plants in the KK are vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Species distribution modelling (SDM) can be used to assess the vulnerability of species under climate change. Here, we evaluated range size changes for three (critically) endangered endemic species that grow at various elevations (Nepeta binaloudensis, Phlomoides binaludensis, and Euphorbia ferdowsiana) using species distribution modelling. Using the HadGEM2-ES general circulation model and two Representative Concentration Pathways Scenarios (RCP 2.6 and RCP 8.5), we predicted potential current and future (2050 and 2070) suitable habitats for each species. The ensemble model of nine algorithms was used to perform this prediction. Our results indicate that while two of species investigated would benefit from range expansion in the future, P. binaludensis will experience range contraction. The range of E. ferdowsiana will remain limited to the Binalood mountains, but the other species will have suitable habitats in mountain ranges across the KK. Using management efforts (such as fencing) with a focus on providing elevational migration routes at local scales in the KK is necessary to conserve these species. Additionally, assisted migration among different mountains in the KK would be beneficial to conserve these plants. For E. ferdowsiana, genetic diversity storage employing seed banks and botanical garden preservation should be considered.

Subject terms: Climate-change ecology, Biogeography

Introduction

Climate is one of the main determinants delimiting geographical distribution of plant species on large scale1. There is a considerable amount of research declaring climate change lead to the range expansion or retraction in plant species ranges (e.g. Refs.2–5). To assess the vulnerability of plant species under a rapidly changing climate, we can use species distribution modelling (SDM) to predict species climate niches and project their potential future range shifts4,6–8. The SDM results can be used to develop adaptive management strategies, including assisted migration, to mitigate the effects of climate change1,2,9.

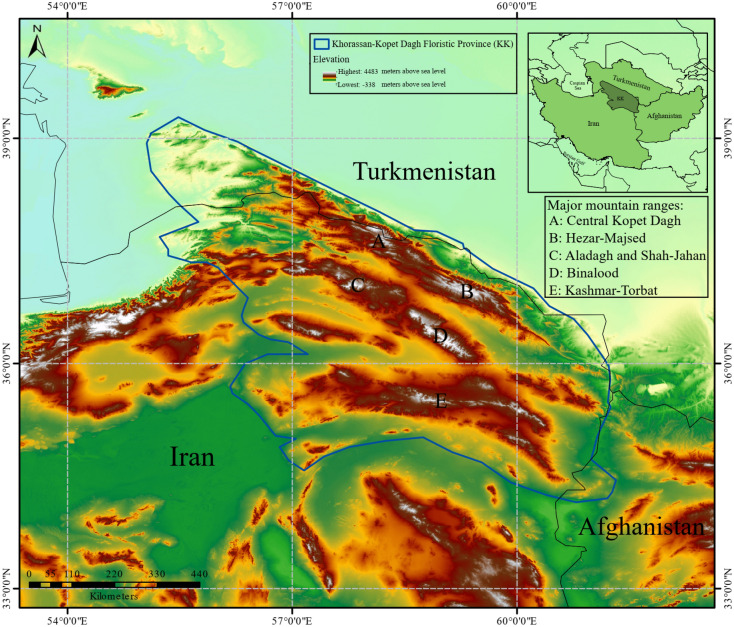

The Khorassan-Kopet Dagh (KK) floristic province is located mainly in northeastern Iran, and partially in southern Turkmenistan and northwestern Afghanistan (Fig. 1)10–12. This region is an under-studied biogeographic entity. A total number of 2576 vascular plant species have been recorded from this region. Among these, 356 species are endemics13. Except for a recent study on Dianthus polylepis14, no studies have been conducted to investigate the effects of climate change on endemic plants in the KK. Nepeta binaloudensis Jamzad (Lamiaceae) is a perennial species endemic to the KK. This plant grows in the elevation range of 2300–3000 m.a.s.l. in the Binalood Mountains. It has recently been recorded from the Hezar-Masjed Mountains15–17. N. binaloudensis is used in traditional medicine in northeastern Iran18,19. Antispasmodic, anti-allergic, and antidepressant effects have been reported for this plant. As a result, local people collect N. binaloudensis from the Binalood Mountain Range17,19. This species has been categorized as an endangered plant int the KK20. Phlomoides binaludensis Salmaki & Joharchi (Lamiaceae) is another endemic species to the KK. Hitherto, P. binaludensis has only been recorded from the Binalood Mountains. This perennial plant grows in the elevation range of 1350–2000 m.a.s.l.21. P. binaludensis has been categorized as an endangered plant20. Euphorbia ferdowsiana Pahlevani (Euphorbiaceae) is an endemic perennial growing in the Binalood Mountains. It has a narrow distribution range in the eastern slopes of this mountain range and has been recorded from the elevation range of 2100–2700 m.a.s.l.22. Due to its limited records, this plant has been categorized as a critically endangered species20.

Figure 1.

Study area—the Khorassan-Kopet Dagh floristic province (KK). The elevation range reported in the legend is for the entire map and not corresponds to the elevation range of KK. The original figure was adopted from Ref.14.

Here, considering three [critically] endangered endemics that grow in the elevation range of 1350–3000 m.a.s.l. in the KK, we aimed to evaluate how climate change affects their potential distribution range. Specifically, our goals were to (a) model the current potential suitable habitats of these species; (b) study the effects of climate change on their current range size by using an ensemble model of nine modelling algorithms for 2050 and 2070 under the most optimistic and pessimistic climate change scenarios; (c) evaluate the future elevation shifts of these plants. We conducted this study to provide management guidance to protect endangered endemic plants from the effects of climate change in this poorly studied region.

Materials and methods

Study area

Our study area was the KK floristic province (Fig. 1). This region is a transitional zone connecting different phytogeographical units of the Middle East (i.e., Irano-Turanian region)11. According to Olson et al.23, six ecoregions (namely the Badghyz and Karabil semi-desert, Central persian desert basins, Elburz range forest steppe, Kopet Dag semi-desert, Kopet Dag woodlands and forest steppe, and Kuh Rud and Eastern Iran montane woodlands) are completely or partially located in the study area. The KK occupies an area of around 165,000 km2 and has a complex topography ranging from approximately 250 m.a.s.l. in the lower foothills to the elevations higher than 3000 m.a.s.l. in the Shirbad (3319 m.a.s.l.), Hezar-Masjed (3128 m.a.s.l.), and Shah-Jahan (3032 m.a.s.l.) Mountains11,13. The KK has a continental climate. Mountain ranges in KK have a Mediterranean or Irano-Turanian xeric-continental bioclimate with an average annual precipitation of 300–380 mm. The mean annual temperature in the area shows elevation-dependent values and ranges between 12–19 °C11,24. The KK is home to diverse vegetation types. Among these types, the montane steppes and grasslands are the most abundant. Furthermore, it is an important hotspot for other species groups12,25,26. The area is hosting 2576 species or infraspecific vascular plant taxa. Among these species, 356 (13.8 percent of the total species pool) are endemic to this region11,13,20. Most of the endemic species of the KK are range-restricted and rare27. The mountainous habitats in the KK are threatened by various disturbances (e.g. overgrazing, land use change, and recreation activities)28,29. Approximately, eight percent of the KK habitats are protected and managed with different protection guidelines11,13,28–32.

Species data

Occurrence records for the studied species were obtained from botanical surveys, including the records from Ferdowsi University of Mashhad Herbarium (FUMH). These surveys were mostly one-time botanical surveys to collect plant specimens from different parts in the KK. Data collection were mainly carried out from 2002 to 2018. The occurrence points that entered in the analysis included all possible environmental conditions in that the studied species have been recorded from the KK. True absence points were collected from plot sampling and botanical surveys. Plot samplings have been conducted in some parts of the study region. Nevertheless, botanical surveys have been conducted in the entire area. For N. binaloudensis, we opted to use absence points from plots that were sampled from the Binalood and Hezar-Masjed Mountain Ranges. For the other two that are exclusive to the Binalood Mountains, we included the absence points from botanical surveys across mountain ranges outside of the Binalood Mountains. Furthermore, for these two species, true absences from the Binalood Mountains were obtained from plot data. Species occurrence points are included in Supplementary Information. Nevertheless, we included pseudoabsence (i.e., background) points in our modelling because the number of true absence points was low. The study area was defined based on biogeographical boundaries and absence points were randomly selected from all points within geographic range of the species. Three sets of background points (n = 10,000) were generated using the biomod2 package33. All calculations were performed in R ver. 3.634.

We filtered occurrence data by randomly selecting a presence point within a single grid cell (i.e., 1 × 1 km) using the spThin package35. Finally, for N. binaloudensis, 13 occurrence points + 36 true absence points + three sets of 10,000 background points; for P. binaludensis, 11 occurrence points + 569 true absence points + three sets of 10,000 background points; and for E. ferdowsiana, 5 occurrence points + 580 true absence points + three sets of 10,000 background points were used for the modelling.

Environmental data

We used physiographic maps and bioclimatic variables in SDM. Physiographic maps were: elevation, slope, and aspect with a 1-km2 resolution. In this study, 19 bioclimatic layers (Table 1), which are reliable in defining the physio-ecological tolerances of a species were used. These layers were downloaded from Worldclim36. Future layers for 2050 and 2070 were also downloaded. To download future layers, the Hadley Centre Global Environmental Model version 2‐Earth System (HadGEM2-ES) general circulation model (GCM) and two Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) scenarios [i.e., RCP 2.6 (most optimistic) and RCP 8.5 (most pessimistic)] were selected. We used the HadGEM2-ES model because it showed appropriate temperature forecasting when compared with the real data obtained from different synoptic stations in Iran37. The resolution of the current and future layers was 1-km2.

Table 1.

Nineteen bioclimatic variables that were used to model the suitable habitats for the studied species in the present study.

| Bioclimatic variable | Name |

|---|---|

| Mean annual temperature | BIO1 |

| Mean Diurnal range | BIO2 |

| Isothermality | BIO3 |

| Temperature seasonality | BIO4 |

| Maximum temperature of warmest month | BIO5 |

| Minimum temperature of coldest month | BIO6 |

| The annual temperature range (BIO5–BIO6) | BIO7 |

| the mean temperature of wettest quarter | BIO8 |

| the mean temperature of the driest quarter | BIO9 |

| Mean temperature of warmest quarter | BIO10 |

| Mean temperature of coldest quarter | BIO11 |

| Annual precipitation | BIO12 |

| Precipitation of wettest month | BIO13 |

| Precipitation of driest month | BIO14 |

| Precipitation seasonality (standard deviation/mean) | BIO15 |

| Precipitation of wettest quarter | BIO16 |

| Precipitation of driest quarter | BIO17 |

| Precipitation of warmest quarter | BIO18 |

| Precipitation of coldest quarter | BIO19 |

To select layers (i.e., physiographic and bioclimatic layers), we performed a principal component analysis (PCA) and visualized the correlation between the environmental layers. PCAs were performed in the ade4 package by using the dudi.pca function38. Layers with the most contribution in explaining the variation of the species occurrence points space were selected. As suggested by Guisan et al.39, this analysis was performed. To remove collinear layers, we calculated variance inflation factor (VIF) for the selected layers. VIFs were calculated by performing a step-by-step process using the usdm package40. We selected those variables with VIF below ten, because VIF above ten shows a serious collinearity problem41. A list of the selected variables for each species is presented in Supplementary Table S1 of supplementary data.

Modelling settings

Nine modelling algorithms—including the Generalised Linear Model (GLM), Generalized Additive Model (GAM), Generalized Boosting Model (GBM), Classification Tree Analysis (CTA), Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Surface Range Envelop (SRE, also known as BIOCLIM), Multiple Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS), Random Forest (RF), and Maximum Entropy (MAXENT)—were used in this study. These nine algorithms are available in the biomod2 package. We randomly split the occurrence data into two subsets, 70 percent of the data were used for the model calibration. The remaining 30 percent was used for model evaluation. We split data because we did not have independent data for model evaluation. The number of replications was set to ten to calculate each model.

To measure SDM performance, we employed the True Skill Statistic (TSS) and Area Under Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operation Curves. TSS is a threshold-dependent measure, ranges between − 1 and + 1, where + 1 indicates perfect agreement between predictions and observations, and values of 0 or less indicate agreement no better than random partitioning42. AUC is widely used to determine the predictive accuracy of SDMs. Generally, AUC ranges between 0.5 to 1.0 and models with AUC > 0.9 are categorized as very good5. For the binary transformation, we employed the threshold maximizes TSS to convert the occurrence probability values into presence/absence predictions. The thresholding approach that maximizes TSS is well suited because it produces the same threshold using either presence-absence or presence-only data39. These calculations were performed by using the biomod2 package33.

Ensemble forecasting

We used the ensemble forecasting procedure to obtain final models in order to reduce the uncertainty among the species distribution algorithms. To combine models, we selected those with TSS > 0.9. Ensemble models were predicted for current and future conditions at a 1-km2 resolution. The ensemble models were converted into binary presence-absence predictions using the threshold that maximizes TSS. The ensemble forecasting was performed in the biomod2 package.

Range and elevational shifts

To evaluate the range size changes of the studied species, we compared the predicted models for the future distribution of the species to that of their current distribution. Then, we distinguished four distinct habitat types; (a) stable habitats: habitats that are suitable in current and future climatic conditions; (b) lost habitats: currently suitable habitats that will not remain suitable in future; (c) gained habitats: currently unsuitable habitats that will become suitable in future; (d) unsuitable habitats: habitats that are unsuitable for species both in the current and future climatic conditions. Range size changes were predicted by using the biomod2 package33.

The predictive ensemble maps for the current and future (i.e., 2050 and 2070) were related with elevation classes. We extracted the elevation of the grids correspond to species presence from the current and future ensemble maps. Then, bar plots were drawn in R to compare the elevational range of the potential current and future habitats.

Results

Modelling evaluation

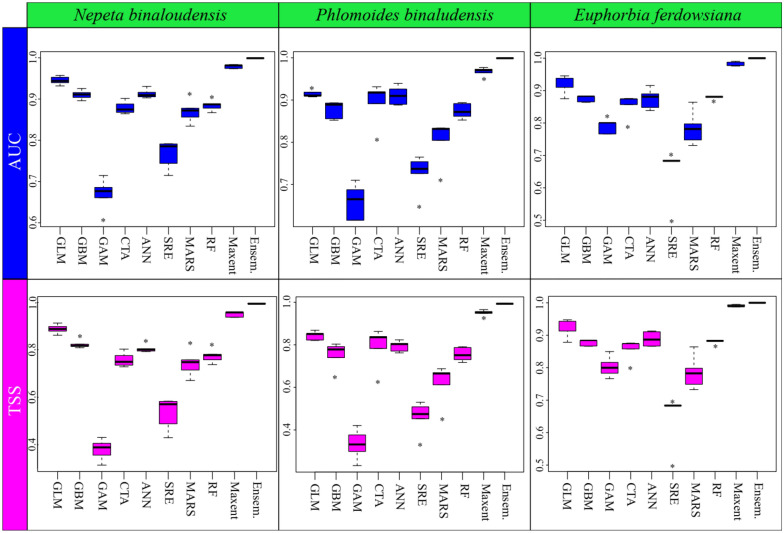

The MAXENT and GLM algorithms performed better than the other algorithms. In the studied species, the ensemble models had the best overall performance with both TSS and ROC values above 0.99. Figure 2 presents the predictive performance of the nine modelling algorithms for studied species showing inter-model variability.

Figure 2.

Boxplots showing the AUC and TSS scores for model evaluation from ten cross‐validation runs on test data for the nine SDM algorithms that were used for the prediction of three species distribution in the Khorassan-Kopet Dagh floristic province. For comparison, the evaluation scores for the ensemble model are shown. The ensemble model does not include those models with a TSS < 0.9. See the text for model abbreviations.

Nepeta binaloudensis

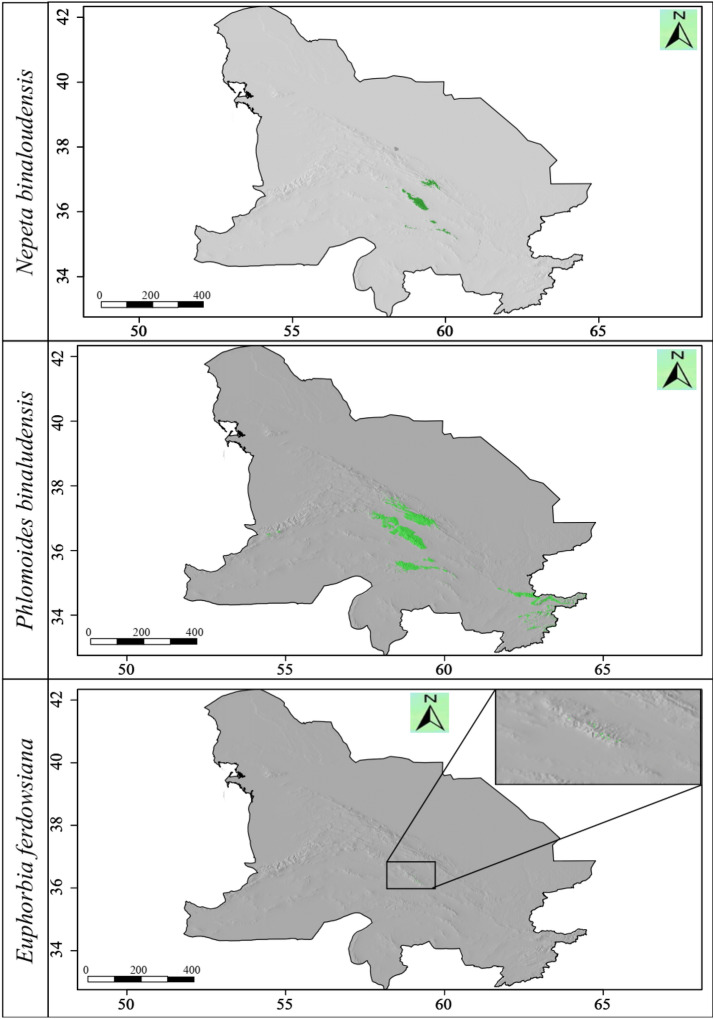

The ensemble habitat suitability map showed that the area of the currently suitable habitats for N. binaloudensis was 3407 km2 (Fig. 3). The base map that was used to show SDM results does not match that of the KK boundaries. This map also covers peripheral areas. The range size analysis showed that in 2050 and under RCP 2.6 (the most optimistic) scenario, 708 km2 of the currently suitable habitats will be lost, which is approximately 21 percent of the current habitats. Nevertheless, 3408 km2 would become newly suitable habitats that is equal to approximately 100 percent increase in the current range size. Finally, 2699 km2 of the current habitats will remain suitable for this species. The range size change for this species will be 79 percent. In 2050 and under RCP 8.5 (the most pessimistic) scenario, 963 km2 (28 percent) of the currently suitable habitats will become unsuitable; on the other hand, 2947 km2 will become suitable—86 percent increase of the current range size. Finally, 2444 km2 (72 percent) of the current habitats will remain suitable. As a result, the changes in the range size for this species will be 58 percent (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

The habitat suitability maps of Nepeta binaloudensis, Phlomoides binaludensis, and Euphorbia ferdowsiana under the current climate conditions in the Khorassan-Kopet Dagh floristic province. Green areas indicate suitable habitats. The base map does not match that of KK boundaries and covers peripheral areas. The following maps have been generated in R ver. 3.6 (https://www.r-project.org).

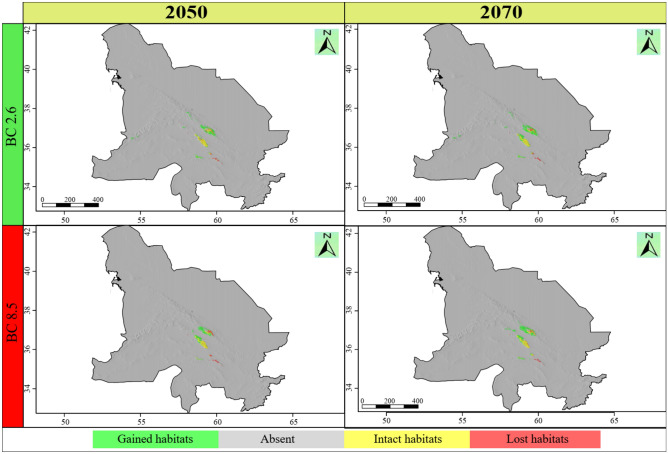

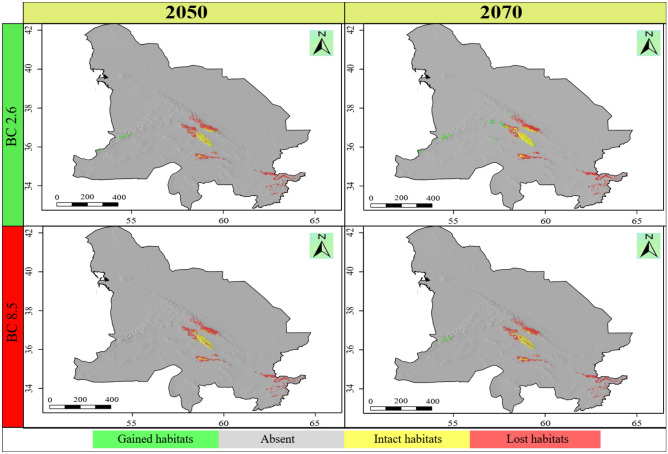

Figure 4.

Range size changes of Nepeta binaloudensis in the future years (2050 and 2070) under the most optimistic (RCP 2.6) and pessimistic (RCP 8.5) scenarios. The base map does not match that of KK boundaries and covers peripheral areas. The following maps have been generated in R ver. 3.6 (https://www.r-project.org).

In 2070 and under RCP 2.6 scenario, 771 km2 (23 percent) of the currently suitable habitats will become unsuitable, 2636 km2 (77 percent) will remain suitable, and 4333 km2 will be newly suitable habitats indicating 127 percent increase. The range size changes for this plant will be 104 percent. Under RCP 8.5 scenario in 2070, 680 km2 (20 percent) will be lost. The stable area covers 2727 km2 (80 percent), and 4096 km2 will become suitable for this species growth (i.e., 120 percent habitat gain) (Fig. 4). Therefore, the range size change will be 100 percent for this year and under this scenario (Table 2).

Table 2.

The range changes for the studied species under climate change conditions in KK.

| Species | Climate scenario | Total range size (km2) | Stable habitats | Lost habitats | Gained habitats | Range size change | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | % | km2 | % | km2 | % | km2 | % | |||

| Nepeta binaloudensis | Current | 3407 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 2050—RCP 2.6 | 6107 | 2699 | 79 | 708 | 21 | 3408 | 100 | 2700 | 79 | |

| 2050—RCP 8.5 | 5391 | 2444 | 72 | 963 | 28 | 2947 | 86 | 1984 | 58 | |

| 2070—RCP 2.6 | 6969 | 2636 | 77 | 771 | 23 | 4333 | 127 | 3562 | 104 | |

| 2070—RCP 8.5 | 6823 | 2727 | 80 | 680 | 20 | 4096 | 120 | 3416 | 100 | |

| Phlomoides binaludensis | Current | 19,311 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 2050—RCP 2.6 | 7019 | 5578 | 29 | 13,733 | 71 | 1441 | 7 | 12,292 | − 64 | |

| 2050—RCP 8.5 | 5388 | 5185 | 27 | 14,126 | 73 | 203 | 1 | 13,923 | − 72 | |

| 2070—RCP 2.6 | 9615 | 6738 | 35 | 12,573 | 65 | 2877 | 15 | 9696 | − 50 | |

| 2070—RCP 8.5 | 6489 | 5419 | 28 | 13,892 | 72 | 1070 | 6 | 12,822 | − 66 | |

| Euphorbia ferdowsiana | Current | 0 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 2050—RCP 2.6 | 42 | 13 | 22 | 47 | 78 | 29 | 48 | 18 | − 30 | |

| 2050—RCP 8.5 | 129 | 21 | 35 | 39 | 65 | 108 | 180 | 69 | 115 | |

| 2070—RCP 2.6 | 117 | 24 | 40 | 36 | 60 | 93 | 155 | 57 | 95 | |

| 2070—RCP 8.5 | 91 | 16 | 27 | 44 | 73 | 75 | 125 | 31 | 52 | |

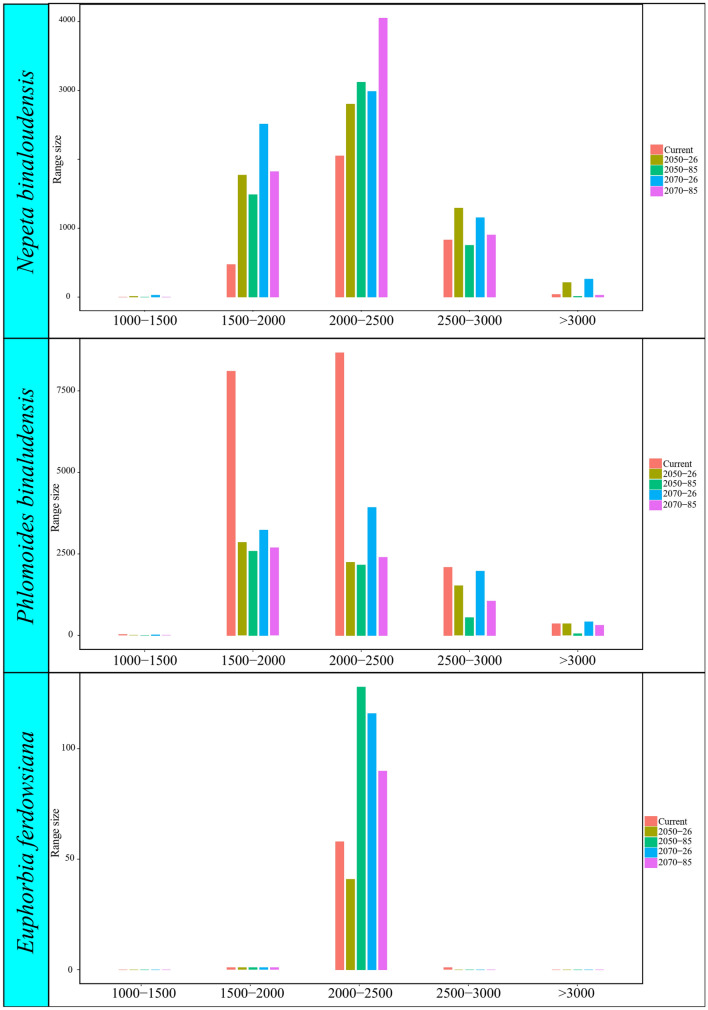

The comparison of ensemble maps along elevation classes indicated that N. binaloudensis, during both climate change scenarios, would expand its range in sites located between 1500–3000 m.a.s.l. In sites above 3000 m.a.s.l. depending on climate change scenario this plant would experience range expansion or contraction (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Range size of the studied species in relation to elevation classes under current and future climate change scenarios.

Phlomoides binaludensis

The ensemble habitat suitability map showed that the current range size (i.e., potential current suitable habitats) for P. binaludensis was 19,311 km2 (Fig. 3). In 2050 and under RCP 2.6 scenario, 13,733 km2 (71 percent) of the currently suitable habitats will become unsuitable, 5578 km2 (29 percent) will remain suitable, and 1441 km2 will be newly suitable areas for this species—7 percent increase in distribution. The range size changes for this plant will be − 64 percent. Under RCP 8.5 scenario in 2050, 14,126 km2 (73 percent) will become unsuitable. The stable habitats cover 5185 km2 (27 percent), and 203 km2 will become suitable for this species growth—1 percent habitat gain. As a result, the range size changes for this species will be − 72 percent (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Range size changes of Phlomoides binaludensis in the future years (2050 and 2070) under most optimistic (RCP 2.6) and pessimistic (RCP 8.5) scenarios. The base map does not match that of KK boundaries and covers peripheral areas. The following maps have been generated in R ver. 3.6 (https://www.r-project.org).

In 2070, under RCP 2.6 scenario, 12,573 km2 (65 percent) of the current habitats will become unsuitable, on the other hand, 2877 km2 will become suitable for this species growth—15 percent habitat gain. Also, 6738 km2 (35 percent) of the current habitat size will remain suitable. As a result, changes in the range size for this species will be − 50 percent. In this year and under RCP 8.5 scenario, 13,892 km2 (72 percent) of the currently suitable habitats will become unsuitable, 5419 km2 (28 percent) will remain suitable, and 1070 km2 (i.e., 6 percent habitat gain) will be newly suitable habitats for this species (Fig. 6). The range size changes for this species will be − 66 percent (Table 2).

The comparison of ensemble maps along elevation classes revealed that P. binaludensis would contract in sites that located above 1500 m.a.s.l. during future climate change scenarios. Depending on climate change scenario the amount of range contraction will vary (Fig. 5).

Euphorbia ferdowsiana

The ensemble habitat suitability map showed that the current range size of E. ferdowsiana was 60 km2 (Fig. 3). In 2050 and under RCP 2.6 scenario, 47 km2 (78 percent) of the current suitable habitats will become unsuitable, 13 km2 (22 percent) will remain suitable, and 29 km2 (48 percent) will be newly suitable habitats for this species. Therefore, the range size changes for this species will be − 30 percent. Under RCP 8.5 scenario in 2050, 39 km2 (65 percent) will become unsuitable. The stable habitats will cover 21 km2 (35 percent), and 108 km2 will become suitable for this species growth—180 percent increase in distribution. As a result, the range size changes for this species will be 115 percent (Fig. 7).

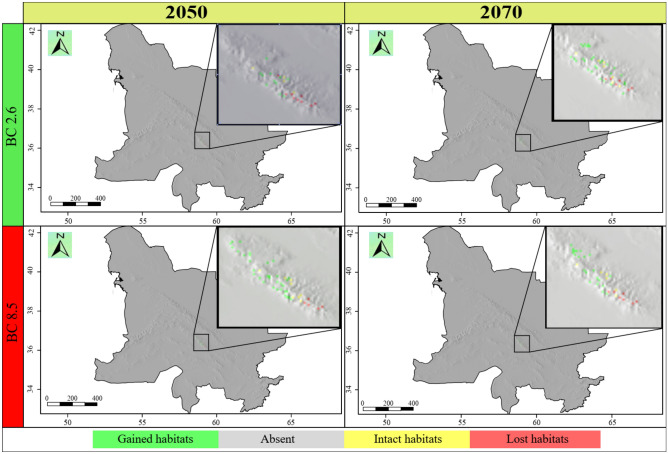

Figure 7.

Range size changes of Euphorbia ferdowsiana in the future years (2050 and 2070) under most optimistic (RCP 2.6) and pessimistic (RCP 8.5) scenarios. The base map does not match that of KK boundaries and covers peripheral areas. The following maps have been generated in R ver. 3.6 (https://www.r-project.org).

In 2070, under RCP 2.6 scenario, 36 km2 (60 percent) of the current habitats will become unsuitable, on the other hand, 93 km2 (155 percent) will become suitable. Also, 24 km2 (40 percent) of the current suitable habitats will remain suitable. As a result, changes in the range size for this species will be 95 percent. In this year and under RCP 8.5 scenario, 44 km2 (73 percent) of the currently suitable habitats will be lost, 16 km2 (27 percent) will remain suitable, and 75 km2 will be newly suitable areas for this species (i.e., 125 percent habitat gain) (Fig. 7). The range size changes for E. ferdowsiana will be 52 percent (Table 2).

Considering distribution of E. ferdowsiana across elevation classes, a narrow elevation range of this plant was found. We compared future distribution across elevation classes and found that E. ferdowsiana would experience range contraction in sites between 2500 and 3000 m.a.s.l. Also, it would contract between 2000 and 2500 m.a.s.l. under RCP 2.6 in 2050 or it would experience range expansion considering the other studied climate change scenarios (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Model performance

In the current study, we showed that climate change will lead to species specific range expansion/contraction and elevational shifts. Our results revealed the variability among different SDM algorithms. Since there is no best algorithm for species distribution modelling, we used an ensemble model of the nine different algorithms. The ensemble model outperformed the other models. The efficiency of ensemble models was also reported by the other studies6,43–45. However, Hao et al.46 found no particular benefit in using ensembles over individual algorithms. Considering single algorithms, the MaxEnt showed the highest predictive performance. Kaky et al.45 suggested using the MaxEnt when computational power and knowledge is limited.

Climate change impacts on Nepeta binaloudensis

The current potential suitable habitats of N. binaloudensis is largely located in the Binalood Mountains along with two patches in the Hezar-Masjed and Kashmar-Torbat Mountains. Ensemble map shows topographic-climatically suitable habitats in the Kashmar-Torbat Mountains. Hitherto, no literature data indicates the occurrence of this plant in this mountain range. Also, N. binaloudensis has not been found in floristic surveys in this area in the past ten years. This indicating a possible local extinction or lack of comprehensive floristic knowledge of the KK. A similar problem was reported for Rosa arabica in Egypt47. In 2050 and 2070 under the most optimistic scenario (RCP 2.6), a large part of the current suitable habitats that are located in the Binalood Mountains will remain unaffected. While range expansion will happen in the Hezar-Masjed Mountains in 2050 and 2070, the current suitable habitats in this mountain will become unsuitable. Translocation from lost habitats to gained habitats is necessary to ensure this species survival in the Hezar-Masjed Mountain Range. In 2050 and 2070, a northwestern migration trend will be observed for this species. As a result, new habitats will become suitable in the Central Kopet Dagh and Aladagh and Shah-Jahan Mountains. Under the most pessimistic scenario (RCP 8.5) in 2050 and 2070, a similar migration trend of RCP 2.6 will be detected. However, the Central Kopet Dagh Mountains will not become suitable habitat for this plant. As a result of climate change, a range expansion will be observed for this species. Range expansion as a result of climate change was reported for endemic herbs of Namibia48, some endemic plants of biodiversity hotspots in India49, plant species in Sardinia (Italy)50, various Larix species51, and some of European plant species52. While range expansion is supported by all scenarios in the lower elevation classes, in the higher elevations, this amplitude is not supported by all climate change scenarios (Fig. 5). Hitherto, there is no record of N. binaloudensis at elevations below 2000 m.a.s.l.16,17,53, the current distribution map indicated a possible local extinction in habitats located in this elevation range. This extinction can be due to extensive collecting of this medicinal plant17 or the long history of disturbances (e.g., land use changes and grazing) in the study area28,29.

Climate change impacts on Phlomoides binaludensis

The potential current suitable habitats of this species are the Binalood Mountains, Hezar-Masjed, Aladagh and Shah-Jahan, Kashmar-Torbat, and some parts of northwestern Afghanistan mountains. Thus far, this species has only been recorded from the Binalood Mountains. This possible local extinction of potential suitable habitats might be due to the anthropogenic disturbances. Moreover, distribution range of this species might be limited by factors that were not included in this study (e.g., soil). We recommend further studies aiming to record P. binaludensis presence or investigate reasons for its absence in the potential suitable habitats of this plant that located outside the Binalood Mountain Range. Our results showed (Fig. 3), in the Binalood Mountains, this species has a broad distribution range that suggests its least vulnerability.

Due to the climate change, considering either scenarios or years, range contraction would be observed for this species. According to future distribution projections, a possible northwestern migration might occur. This could be a reason for confirming local extinction in its southern habitats—habitats that are climatically suitable without any recorded P. binaludensis occurrence. In the future, this plant will probably be less observed for the southern parts of the Binalood Mountain Range. Compared with N. binaloudensis, this species prefers cooler habitats. Due to climate change, suitable habitats for P. binaludensis will decrease, while N. binaloudensis experiences range expansion. Naturally, this plant will not migrate to the predicated gained habitats across the KK because of its limited range. Consequently, assisted migration should be used to introduce it to newly suitable habitats.

Phlomoides binaludensis has been recorded from elevation range of 1500–2500 m.a.s.l.21. Our results indicated massive range contraction in this elevation range (Fig. 5). However, range contraction at the upper elevations was not supported by all scenarios. Range contraction has been reported for many species in mountainous regions (e.g., Refs.6,54–59). As suggested by Abdelaal et al.47, the reason for range contraction is changing in the climatic envelope (precipitation and temperature).

Climate change impacts on Euphorbia ferdowsiana

The current potential suitable habitats of E. ferdowsiana are restricted to the Binalood Mountain Range. The southern parts of this mountain range are the favourable habitats for this species. In 2050 and 2070, under either BC 2.6 or BC 8.5 current suitable habitats would become unfavourable. As a result, this species should migrate to the northwestern parts of the Binalood Mountain Range to ensure its survival. This critically endangered species will experience a limited range expansion within the Binalood Mountains. The results of the present study showed that this species has a narrow optimum elevational range (i.e., 2000–2500 m.a.s.l.). Due to climate change, no major elevation shift would occur for this plant.

Limitations

We could not include soil, land use, and land cover variables for this study in the KK due to the fact that we did not have available data on a scale similar to bioclimatic variable (i.e., 1-km2). Successful migration of a species to potential future suitable habitats depends on climatic conditions, land use, biotic interactions, and the effects of microfugia4. Except for climatic conditions, we had no data on the other factors to assess the rate of successful future migrations. Adding seed dispersal ability as a variable in modelling plant range shifts resulted in a reduced number of possible future suitable habitats60, and this factor should be considered in interpreting the range expansion reported in this study.

Conclusions

Here, we have determined three habitat types for the studied species. Proper conservation of these endangered species can be done based on what has been suggested by Fois et al.61. Monitoring, fencing, and reinforcement of the current populations are essential for intact habitats. For future suitable habitats (i.e., gained habitats), seeds and other propagules can be translocated from population in lost habitats. In the present study, the Dowlat Abad area located in central parts of the Binalood Mountain Range is a suitable area in order to protect the intact habitats. All studied plants have been recorded from the Dowlat Abad. For E. ferdowsiana, genetic diversity storage employing seed banks and botanical garden preservation should be considered.

We have studied three endangered plants that grow in different elevational ranges of KK mountains. The studied species will migrate to northwestern parts of the KK. Our results have showed that beside range contraction endangered species could also gain suitable future habitats. Our results can be used to propose proper management and conservation of the endangered species in the under-studied KK region. To decrease the risk of extinction in the wild, ex-situ and in-situ conservation activities for studied species are urgent. We suggest reinforcements of the existing populations in the Binalood Mountains and fencing different parts of this relatively disturbed mountain range. Also, programs of assisted migrations for P. binaludensis and E. ferdowsiana should be planned in the wild. No conservation program will be successful without increasing of public awareness and reducing the anthropogenic disturbances.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Ferdowsi University of Mashhad for the financial support of this research.

Author contributions

M.B.E., H.E., and M.S. designed the study. F.M. and M.S. provided the data. M.B.E. analysed the data and prepared figures and tables. M.B.E. and M.S. write the first draft. The final draft was approved by all of the authors.

Data availability

The data regarding this study are presented in Supplementary Information.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-88577-x.

References

- 1.Ferrarini A, Dai J, Bai Y, Alatalo JM. Redefining the climate niche of plant species: A novel approach for realistic predictions of species distribution under climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;671:1086–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrarini A, Alsafran MHSA, Dai J, Alatalo JM. Improving niche projections of plant species under climate change: Silene acaulis on the British Isles as a case study. Clim. Dyn. 2019;52:1413–1423. doi: 10.1007/s00382-018-4200-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walther G-R, et al. Ecological responses to recent climate change. Nature. 2002;416:389–395. doi: 10.1038/416389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thuiller W, Lavorel S, Araujo MB, Sykes MT, Prentice IC. Climate change threats to plant diversity in Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:8245–8250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409902102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mousavi Kouhi SM, Erfanian MB. Predicting the present and future distribution of medusahead and barbed goatgrass in Iran. Ecopersia. 2020;8:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alavi SJ, Ahmadi K, Hosseini SM, Tabari M, Nouri Z. The response of English yew (Taxus baccata L.) to climate change in the Caspian Hyrcanian Mixed Forest ecoregion. Reg. Environ. Change. 2019;19:1495–1506. doi: 10.1007/s10113-019-01483-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huntley B, Berry PM, Cramer W, McDonald AP. Special paper: Modelling present and potential future ranges of some European higher plants using climate response surfaces. J. Biogeogr. 1995;22:967. doi: 10.2307/2845830. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearson RG, Dawson TP. Predicting the impacts of climate change on the distribution of species: Are bioclimate envelope models useful?: Evaluating bioclimate envelope models. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003;12:361–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1466-822X.2003.00042.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hällfors MH, et al. Assessing the need and potential of assisted migration using species distribution models. Biol. Conserv. 2016;196:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.01.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamakhina, G. L. Kopetdagh-Khorassan Flora: Regional Features of Central Kopetdagh. In Biogeography and Ecology of Turkmenistan (eds. Fet, V. & Atamuradov, K. I.) Vol. 72 129–148 (Springer Netherlands, 1994).

- 11.Memariani F, Zarrinpour V, Akhani H. A review of plant diversity, vegetation, and phytogeography of the Khorassan-Kopet Dagh floristic province in the Irano-Turanian region (northeastern Iran–southern Turkmenistan) Phytotaxa. 2016;249:8. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.249.1.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fet, V. Biogeographic Position of the Khorassan-Kopetdagh. In Biogeography and Ecology of Turkmenistan (eds. Fet, V. & Atamuradov, K. I.) Vol. 72 197–204 (Springer Netherlands, 1994).

- 13.Memariani, F. Khorassan-Kopet Dagh mountains. In Plant Biogeography and Vegetation of High Mountains of Central and South-West Asia (ed. Noroozi, J.) (Springer, 2020). https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.4sb6383

- 14.Behroozian M, Ejtehadi H, Peterson AT, Memariani F, Mesdaghi M. Climate change influences on the potential distribution of Dianthus polylepis Bien. ex Boiss. (Caryophyllaceae), an endemic species in the Irano-Turanian region. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0237527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erfanian, M. B. et al. Data from: Plant community responses to environmentally-friendly piste management in northeast Iran. Dryad Dataset.https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.4sb6383 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Jamzad, Z. Flora of Iran vol. 76 Lamiaceae. (Research Institute of Forests & Rangelands, 2012).

- 17.Sagharyan M, Ganjeali A, Cheniany M. Investigating the effect of antioxidant compounds and various concentrations of BAP and NAA on the improvement of in vitro stem and root formation of Nepeta binaloudensis Jamzad. NBR. 2019;6:198–205. doi: 10.29252/nbr.6.2.198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nadjafi F, Koocheki A, Moghaddam PR, Rastgoo M. Ethnopharmacology of Nepeta binaludensis Jamzad a highly threatened medicinal plant of Iran. J. Med. Plants. 2009;8:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadjafi F, Koocheki A, Honermeier B, Asili J. Autecology, ethnomedicinal and phytochemical studies of Nepeta binaludensis Jamzad a highly endangered medicinal plant of Iran. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants. 2009;12:97–110. doi: 10.1080/0972060X.2009.10643699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Memariani F, Akhani H, Joharchi MR. Endemic plants of Khorassan-Kopet Dagh floristic province in Irano-Turanian region: Diversity, distribution patterns and conservation status. Phytotaxa. 2016;249:31. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.249.1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salmaki Y, Joharchi MR. Phlomoides binaludensis (Phlomideae, Lamioideae, Lamiaceae), a new species from northeastern Iran. Phytotaxa. 2014;172:265. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.172.3.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pahlevani AH, Liede-Schumann S, Akhani H. Seed and capsule morphology of Iranian perennial species of Euphorbia (Euphorbiaceae) and its phylogenetic application: Perennial Species of Euphorbia in Iran. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2015;177:335–377. doi: 10.1111/boj.12245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olson DM, et al. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: A new map of life on earth. Bioscience. 2001;51:933. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:TEOTWA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Djamali M, et al. Application of the global bioclimatic classification to Iran: Implications for understanding the modern vegetation and biogeography. Ecol. Mediterr. 2011;37:91–114. doi: 10.3406/ecmed.2011.1350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farashi A, Shariati M, Hosseini M. Identifying biodiversity hotspots for threatened mammal species in Iran. Mamm. Biol. 2017;87:71–88. doi: 10.1016/j.mambio.2017.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosseinzadeh MS, Fois M, Zangi B, Kazemi SM. Predicting past, current and future habitat suitability and geographic distribution of the Iranian endemic species Microgecko latifi (Sauria: Gekkonidae) J. Arid Environ. 2020;183:104283. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2020.104283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noroozi J, et al. Endemic diversity and distribution of the Iranian vascular flora across phytogeographical regions, biodiversity hotspots and areas of endemism. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:12991. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49417-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erfanian MB, Ejtehadi H, Vaezi J, Moazzeni H. Plant community responses to multiple disturbances in an arid region of northeast Iran. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019;30:1554–1563. doi: 10.1002/ldr.3341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erfanian MB, et al. Plant community responses to environmentally friendly piste management in northeast Iran. Ecol. Evol. 2019;9:8193–8200. doi: 10.1002/ece3.5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Memariani, F. et al. Plant diversity of the Khorassan-Kopet Dagh Floristic Province (Irano-Turanian Region). (Magnolia Press, 2016)

- 31.Memariani F, Joharchi MR, Ejtehadi H, Emadzade K. A contribution to the flora and vegetation of Binalood mountain range, NE Iran: Floristic and chorological studies in Fereizi region. Ferdowsi Univ. Int. J. Biol. Sci. J. Cell Mol. Res. 2009;1:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Memariani F, Joharchi MR. Iris ferdowsii (Iridaceae), a new species of section Regelia from northeast of Iran. Phytotaxa. 2017;291:192. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.291.3.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thuiller, W., Georges, D., Engler, R. & Breiner, F. biomod2: Ensemble Platform for Species Distribution Modeling. R Package. https://cran.r-project.org/package=biomod2 (2019).

- 34.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020).

- 35.Aiello-Lammens ME, Boria RA, Radosavljevic A, Vilela B, Anderson RP. spThin: An R package for spatial thinning of species occurrence records for use in ecological niche models. Ecography. 2015;38:541–545. doi: 10.1111/ecog.01132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fick SE, Hijmans RJ. WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017;37:4302–4315. doi: 10.1002/joc.5086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmadi M, Dadashi Roudbari AA, Akbari Azirani T, Karami J. The performance of the HadGEM2-ES model in the evaluation of seasonal temperature anomaly of Iran under RCP scenarios. J. Earth Space Phys. 2019;45:625–644. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dray S, Dufour A-B. The ade4 Package: Implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. J. Stat. Softw. 2007;22:1–20. doi: 10.18637/jss.v022.i04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guisan, A., Thuiller, W. & Zimmermann, N. E. Habitat Suitability and Distribution Models: With Applications in R. (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

- 40.Naimi B, Hamm NAS, Groen TA, Skidmore AK, Toxopeus AG. Where is positional uncertainty a problem for species distribution modelling. Ecography. 2014;37:191–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2013.00205.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menard SW. Applied Logistic Regression Analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159. doi: 10.2307/2529310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Araujo M, New M. Ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007;22:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Breiner FT, Guisan A, Bergamini A, Nobis MP. Overcoming limitations of modelling rare species by using ensembles of small models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015;6:1210–1218. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaky E, Nolan V, Alatawi A, Gilbert F. A comparison between Ensemble and MaxEnt species distribution modelling approaches for conservation: A case study with Egyptian medicinal plants. Ecol. Inform. 2020;60:101150. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2020.101150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hao T, Elith J, Lahoz-Monfort JJ, Guillera-Arroita G. Testing whether ensemble modelling is advantageous for maximising predictive performance of species distribution models. Ecography. 2020;43:549–558. doi: 10.1111/ecog.04890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abdelaal M, Fois M, Fenu G, Bacchetta G. Using MaxEnt modeling to predict the potential distribution of the endemic plant Rosa arabica Crép, Egypt. Ecol. Inform. 2019;50:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2019.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thuiller W, et al. Endemic species and ecosystem sensitivity to climate change in Namibia. Glob. Change Biol. 2006;12:759–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01140.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chitale VS, Behera MD, Roy PS. Future of endemic flora of biodiversity hotspots in India. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e115264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fois M, Bacchetta G, Cogoni D, Fenu G. Current and future effectiveness of the Natura 2000 network for protecting plant species in Sardinia: A nice and complex strategy in its raw state? J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018;61:332–347. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2017.1306496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mamet SD, Brown CD, Trant AJ, Laroque CP. Shifting global Larix distributions: Northern expansion and southern retraction as species respond to changing climate. J. Biogeogr. 2019;46:30–44. doi: 10.1111/jbi.13465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thuiller W, Lavorel S, Araújo MB. Niche properties and geographical extent as predictors of species sensitivity to climate change: Predicting species sensitivity to climate change. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2005;14:347–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-822X.2005.00162.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hosseini, S. S., Ejtehadi, H. & Memariani, F. The first report Nepeta binaloudensis Jamzad in Hezar masjed mountains of Khorasan Razavi province. In Proceedings of the 9th National Congress and 7th International Congrees of Bilogy of Iran (2016).

- 54.Dullinger S, et al. Extinction debt of high-mountain plants under twenty-first-century climate change. Nat. Clim. Change. 2012;2:619–622. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wiens JJ. Climate-related local extinctions are already widespread among plant and animal species. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e2001104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2001104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Casazza G, et al. Climate change hastens the urgency of conservation for range-restricted plant species in the central-northern Mediterranean region. Biol. Conserv. 2014;179:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.09.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang M-G, et al. Major declines of woody plant species ranges under climate change in Yunnan, China. Divers. Distrib. 2014;20:405–415. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanjerehei MM, Rundel PW. The impact of climate change on habitat suitability for Artemisia sieberi and Artemisia aucheri (Asteraceae)—A modeling approach. Pol. J. Ecol. 2017;65:97–109. doi: 10.3161/15052249PJE2017.65.1.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abolmaali SM-R, Tarkesh M, Bashari H. MaxEnt modeling for predicting suitable habitats and identifying the effects of climate change on a threatened species, Daphne mucronata, in central Iran. Ecol. Inform. 2018;43:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2017.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Di Musciano M, et al. Dispersal ability of threatened species affects future distributions. Plant Ecol. 2020;221:265–281. doi: 10.1007/s11258-020-01009-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fois M, Cuena-Lombraña A, Fenu G, Cogoni D, Bacchetta G. The reliability of conservation status assessments at regional level: Past, present and future perspectives on Gentiana lutea L. ssp. lutea in Sardinia. J. Nat. Conserv. 2016;33:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2016.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data regarding this study are presented in Supplementary Information.