Abstract

Background: Voluntary therapeutic interventions to reduce unwanted same-sex sexuality are collectively known as sexual orientation change efforts (SOCE). To date almost all evidence addressing the contested question whether SOCE is effective or safe has consisted of anecdotes or very small sample qualitative studies of persons who currently identify as sexual minority and thus by definition failed to change. We conducted this study to examine the efficacy and risk outcomes for a group of SOCE participants unbiased by current sexual orientation.

Methods: We examined a convenience sample of 125 men who had undergone SOCE for homosexual-to-heterosexual change in sexual attraction, identity and behavior, and for positive and negative changes in psychosocial problem domains (depression, suicidality, self-harm, self-esteem, social function, and alcohol or substance abuse). Mean change was assessed by parametric (t-test) and nonparametric (Wilcoxon sign rank test) significance tests.

Results: Exposure to SOCE was associated with significant declines in same-sex attraction (from 5.7 to 4.1 on the Kinsey scale, p <.000), identification (4.8 to 3.6, p < .000), and sexual activity (2.4 to 1.5 on a 4-point scale of frequency, p < .000). Over 42.7% of SOCE participants achieved at least partial remission of unwanted same-sex sexuality; full remission was achieved by 14% for sexual attraction and identification, and 26% for sexual behavior. Rates were higher among married men, but 4-10% of participants experienced increased same-sex orientation after SOCE. From 0.8% to 4.8% of participants reported marked or severe negative psychosocial change following SOCE, but 12.1% to 61.3% reported marked or severe positive psychosocial change. Net change was significantly positive for all problem domains.

Conclusion: SOCE was perceived as an effective and safe therapeutic practice by this sample of participants. We close by offering a unifying understanding of discrepant findings within this literature and caution against broad generalizations of our results.

Keywords: sexual orientation change, psychosocial health, marriage, ex-gay

Introduction

In 2009 the American Psychological Association released its report on Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation ( APA, 2009, hereafter referred to as the Report), which attempted to summarize what could be definitively concluded from the existent scientific literature at that time. The Report concluded, “Thus, we cannot conclude how likely it is that harm will occur from sexual orientation change efforts (SOCE) (p. 42) and “Given the limited amount of methodologically sound research, we cannot draw a conclusion regarding whether recent forms of SOCE are or are not effective” (p. 83). The Report discouraged practices designed to facilitate change but fell short of recommending ethical or legal bans on any professional practices. Despite this internal restraint and external criticisms of the Report at the time ( Jones et al., 2010), this document has weighed heavily in the escalating legal efforts to ban SOCE that have been waged in the past decade. Currently SOCE provided by licensed therapists have been legally prohibited for minors in 20 states and numerous municipalities in the United States ( Movement Advancement Project, 2020). Efforts to expand the scope of these bans to include adult consumers and non-licensed religious providers are currently underway ( Ashley, 2019; Gamboni et al., 2018).

As recommended by the Report, further research has been undertaken in the intervening decade to accompany this regulatory and legal advocacy. The bulk of this literature has focused on potential harms from SOCE exposure, which has formed the basis for all legal prohibitions to date. Dehlin and colleagues reported a low likelihood of SOCE success and concluded that sexual orientation is highly resistant to purposeful attempts at modification ( Bradshaw et al., 2015; Dehlin et al., 2015). They did find, however, that SOCE in the context of psychiatry and psychotherapy was reported to be moderately to highly effective by 48% and 44% of sample consumers, respectively, although this effectiveness did not seem to be based on experiences of actual change. More recent studies have reported SOCE exposure to be associated with poorer mental health indicators among sexual minority youth (Ryan et al., 2020), adults ( Blosnich et al., 2020; Salway et al., 2020), and midlife and older adults ( Meanley et al., 2020).

Given the opposition to SOCE from professional and funding organizations, it is not surprising very few studies since the time of the APA Report have been conducted offering even modest support for change efforts. In fact, Spitzer’s reinterpretation of his earlier landmark study of consumer reported largely successful SOCE was a blow to proponents of therapy-assisted change ( Spitzer, 2003, 2012), even though several of his original study participants challenged the implied impugning of their integrity (Armelli et al., 2012). A longitudinal study of religiously mediated SOCE followed 63 participants over a seven-year period and reported modest decreases in same-sex attractions, infatuations, and fantasies, with a slim majority of participants indicating shifts toward heterosexual experience ( Jones & Yarhouse, 2011). They further found SOCE did not appear to be harmful on average for their sample. Karten and Wade (2010) found that men conflicted about their same-sex attractions who pursued SOCE reported, on average, a decrease in same-sex feelings and behavior, an increase in heterosexual feelings, and a positive change in their psychological functioning.

In the present study, we intend to add to this literature by examining the SOCE experience of 125 religiously active men, an understudied subgroup of those exposed to SOCE.

We sought to examine two questions: 1) Was participation in SOCE perceived by these consumers to be helpful in alleviating unwanted same-sex attraction, identification and behavior? 2) To what degree was SOCE exposure perceived to be psychologically harmful or beneficial?

Methods

Participants

This study presents a secondary analysis of an online survey previously administered to a convenience sample of adults who had undergone therapeutic intervention to alleviate unwanted same-sex attraction. The survey was administered pursuant to the Doctor of Psychology dissertation of Paul Santero (now Psy.D.) at Southern California Seminary ( Santero, 2011), which contains a more complete description of the survey methods, administration, and question wording. Pertinent to the present study, a major goal of the original survey data collection was to indicate “if the participants’ same sex attractions, thoughts and actions were diminished or changed to thoughts, feelings and behaviors towards the opposite sex”, and “if there were any helpful (or harmful) effects experienced due to therapy” ( Santero, 2011, p. vii). Participants were contacted through religious organizations and therapist networks who offered services including talk therapy, retreats, and support groups that serve this population. Usable surveys were completed by 158 respondents, consisting of 8 females and 150 males. Due to the sparse cell size, females could not be included in the present study. Of the 150 males, 125 responded from the United States, with an additional 25 responding from the United Kingdom, Brazil, Canada, Israel and other countries. Since the questions of interest in this study pertain to SOCE effects in U.S. culture, the present analysis was confined to the 125 male US cases. Demographic information on the study sample is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample characteristics (N=125).

| Variable | Percent | Variable | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Married | 51 (41%) | Highest Education | |

| 1-5 years | 17.65% | High school | 2.4% |

| 6-10 | 7.84% | Some college or AA degree | 24.2% |

| 11-25 | 39.22% | Bachelors Degree | 36.3% |

| 26-50 | 35.29% | Masters Degree | 28.2% |

| Age | Doctoral Degree | 8.9% | |

| 18-25 years | 14.4% | Church attendance | |

| 26-35 | 28% | Daily | 8% |

| 36-45 | 18.4% | Few times a week | 24.8% |

| 46-55 | 23.2% | Once a week | 55.2% |

| 56-65 | 15.2% | A few times a month | 8% |

| 66+ | 0.8% | Major holidays | 1.6% |

| Ethnicity | Rarely or never | 2.4% | |

| African American/Black | 1.6% | Religious Affiliation | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.8 % | Unspecified Christian | 35.0% |

| Caucasian/White | 91.1 % | Mormon (LDS) | 28.5% |

| Hispanic | 4.9 % | Non-Denominational Christian | 13.8% |

| Multi-racial | 1.6% | Jewish | 9.8% |

| Household Income | Roman Catholic | 6.5% | |

| $0-10,000 | 6.6% | Baptist | 4.1% |

| $10,001-$25,000 | 15.7% | Episcopalian | 0.8% |

| $25,001-$50,000 | 19.8% | Methodist | 1.6% |

| $50,001-$75,000 | 17.4% | Region of residence | (n=106) |

| $75,001-$100,000 | 16.5% | West | 54.7% |

| $100,001-$150,000 | 14.1% | Central | 9.43% |

| $150,000+ | 9.9% | South | 13.2% |

| East | 22.64% |

The original survey study and protocols were approved by the Southern California Seminary Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all study subjects prior to participation ( Santero, 2011, p. 154). As a secondary analysis of pre-existing public data, the Catholic University of America Institutional Review Board has certified this study as exempt from human subject ethical review under 45 CFR 46.101.

Measures

The questionnaire (see Extended data ( Sullins, 2021)) included 77 items about issues relating to SOCE exposure. Batteries of items gathered detailed information on the efficacy of different therapeutic interventions, techniques, and even theoretical orientation (e.g., cognitive behavioral, Rogerian, psychoanalytic, gestalt, humanistic or existential). The present study examines a limited set of questions that relate directly to the extent of perceived change in sexual orientation and any related psychological benefit or harm. Several of the items selected for this study were taken from previously published studies ( Shidlo and Schroeder 2002; Spitzer 2003; Karten and Wade 2010).

To measure perceived change or stability in sexual orientation, respondents were asked to indicate both at “six months before getting help” and “currently” how often they: 1) had homosexual sex; 2) experienced homosexual passionate kissing; 3) looked with lust or daydreamed about having homosexual sex; 4) desired romantic, emotional, homosexual intimacy; 5) had heterosexual sex; 6) experienced heterosexual passionate kissing; 7) looked with lust or daydreamed about having heterosexual sex; or 8) desired romantic, emotional, heterosexual intimacy. For these eight items “sex” was defined as “touching genitals, oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse”. Response options, coded 1-5 for analysis, were “almost never”, “yearly”, “monthly”, “weekly”, and “almost daily”. At the time of survey administration, 42% of participants were still pursuing SOCE and 58% had concluded their SOCE. Median time post-SOCE was approximately three years, a conservative estimate due to the highest response category being “more than five years.”

Respondents were also asked to rate both their sexual attraction and sexual identity, six months before getting help and currently, on a modified Kinsey scale (Kinsey, Pomeroy, and Martin 1948) with response options, coded 1-7 for analysis, of “heterosexual”, “almost entirely heterosexual”, “more heterosexual than homosexual”, “bi-sexual”, “more homosexual than heterosexual”, “almost entirely homosexual”, and “homosexual”.

Another series of items related to emotional health asked respondents “As a result of your change efforts, [indicate] the positive (negative) changes you have noticed in the following areas”. The areas were 1) self-esteem, 2) depression, 3) self-harmful behavior, 4) thoughts/attempts of suicide, 5) social functioning, and 6) alcohol and substance abuse. Response options were “none”, “slightly”, “moderately”, “markedly”, and “extremely so”, which were numbered 1-5 on the survey instrument. An additional option of “not applicable” was numbered 0. For analysis the “none” and “not applicable” responses were combined into a base category coded 0, with the remaining options coded 1-4.

Analyses

Self-reported change before and after SOCE was assessed by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, which tests the null hypothesis of no difference between matched nonparametric distributions. Effect sizes for nonparametric contrasts were estimated from the Wilcoxon z-statistic, which is normally distributed, following Lenhard and Lenhard (2016). Effect sizes correspond to the average change or difference in standard deviation, and thus provide a standardized indication of the magnitude of change or contrast which is comparable across differently-scaled variables. The substantive interpretation of effect sizes is a matter of some disagreement and varies according to the variables being considered, however an effect size below .2 is generally interpreted as small, .3-.6 moderate, and above .8 as indicating a large effect.

The Wilcoxon tests reported in Table 2 test the null hypothesis that the distribution of each set of paired before-and-after variables is the same. This test is conservative with regard to the positive hypothesis being considered, which is not just that SOCE exposure alters the components of sexual orientation, but that it alters them in a particular direction, i.e. toward greater heterosexual orientation. One-sided binomial tests resulted in slightly smaller p-values; however, these tests were only sensitive to the median, whereas the Wilcoxon statistic tested the symmetry of the entire distribution. Since significance was so strong for all comparisons tested, and the tests are only illustrative, we opted to report the more precise but also more conservative Wilcoxon tests. It should be borne in mind, however, that the significance of the imputed SOCE effectiveness is probably slightly stronger than that shown in the table.

Table 2. Change in Attraction, Identification and Four Aspects of Behavior following SOCE (N=125).

| Prior to SOCE | Following SOCE | Difference (Wilcoxon) | Effect size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | P | Eta-squared | |

| Attraction | 5.7 (.10) | 4.1 (.16) | .000 | -.56 |

| Identification | 4.8 (.18) | 3.6 (.17) | .000 | -.31 |

| Homosexual Sex | 2.4 (.14) | 1.5 (.09) | .000 | -.26 |

| Homosexual sex ideation | 4.5 (.08) | 3.2 (.12) | .000 | -.53 |

| Desire for Homosexual intimacy | 4.0 (.13) | 3.0 (.13) | .000 | -.33 |

| Homosexual Kissing | 1.8 (.11) | 1.4 (.08) | .001 | -.09 |

| Heterosexual Sex | 1.7 (.11) | 2.0 (.12) | .009 | .06 |

| Heterosexual sex ideation | 1.8 (.10) | 2.8 (.13) | .000 | .41 |

| Desire for Heterosexual intimacy | 2.5 (.13) | 3.4 (.14) | .000 | .37 |

| Heterosexual Kissing | 1.8 (.11) | 2.2 (.13) | .002 | .08 |

SOCE, sexual orientation change efforts. S.E., standard error. Effect size, eta-squared statistic, which expresses the difference in standard deviation between the distributions prior to SOCE and following SOCE.

Numbers in parentheses report the standard error; “P”, p-value for the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for difference of two paired ordinal distributions, which expresses the probability of obtaining test results at least as extreme as the results actually observed if there was no difference between the distributions prior to SOCE and following SOCE.

The results concerning changes in emotional health are presented in Table 9 and described in the results section. Correcting the response option grammar, the “slight” and “moderate” categories were combined, as well as the “marked” and “extreme” categories, to comprise three categories showing no change, slight or moderate change, and marked or extreme change. The measure of negative change was then subtracted from positive change, to produce a single statistic indicating net change for each area, which could be positive or negative. Since 0 indicates “none”, the presence of net positive or negative change due to SOCE was assessed by F-test for the null hypothesis that net change was equal to 0. Analyses for the present study made use of SPSS 25 and Stata 13.

Table 8. Correlation of sexual attraction, identification and behavior prior to and following SOCE (n=125).

| Correlation | Attraction and

identification |

Attraction and

behavior |

Identification and

behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to SOCE | .63 *** | .11 n.s. | .14 n.s. |

| Following SOCE | .83 *** | .38 *** | .36 *** |

SOCE, sexual orientation change efforts. Shown are Spearman rank-order correlations.

p < .000; n.s., not significant.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the sample. Compared to the U.S. population of men, the survey respondents were disproportionately white, Western, highly educated, affluent, and Mormon. Almost all (91%) of the sample was white. Over half (55%) lived in the Western United States. Fully 73% of respondents, or about twice the proportion of all Americans, reported having attained a Bachelor’s degree or higher education. About 58% reported a household income above $50,000, which was just above the national median income ($49,445) in 2011.

The sample participants were much more likely to be unmarried but less likely to be divorced than U.S. men on average. Over half (53%) reported having never been married, about 20 percentage points higher than in the general population (not shown). At the same time, less than 5% were divorced or separated, only about a third the rate for the general population (not shown). Of the 41% of respondents who indicated that they were currently married, 35% had been married more than 25 years, about the same proportion as in the population at large.

The largest identified religious group was “Mormon” or “LDS” (Latter-Day Saints), which was indicated by just under a third (29%) of respondents. However, these were all write- in responses, as the response categories provided did not include “Mormon” or “LDS”. It is likely that many of the respondents who checked “Unspecified Christian”, which at 35% was much larger than this category usually is on such surveys, were also Mormon. If all or even a large proportion of those who indicated “Unspecified Christian” were Mormon, then Mormons comprised over half of the survey sample. The next most common religious group was “Non-denominational Christian” at 14%. Smaller proportions of respondents identified as Roman Catholic, Baptist, Methodist and Episcopalian. Notably, a tenth (9.8%) of the sample identified as Jewish, which is over four times the concentration of Jews in the general population.

Regardless of affiliation, the members of the sample indicated a very high level of religious observance. Almost all of them (88%) reported attending religious services at least once a week, a proportion at least four times higher than the national average. One in twelve (8%) reported attending church every day; only 2% responded that they never or rarely went to church. Other demographic features also suggested a very high level of observance of religious norms regarding marriage and sexuality in the sample. As previously mentioned, despite a low rate of marriage, divorce was relatively rare in this group. Not a single unmarried sample member reported having any children, and only four of the 51 married persons in the sample did not have any children. The parents reported having an average of three children each, almost one child higher than the U.S. average. These characteristics correspond to a group that strictly observes religious norms regarding worship, marriage and fertility within marriage.

Participants reported seeking various kinds of help for their conflicted sexuality. The most frequently used resources were religious support groups (81.5%) and pastoral counselors (70.2%), followed by same-sex retreats (62.1%), marriage or family counselors (61.3%), psychologists (57.3%), non-religious support groups (51.6%), psychiatrist (25.8%) and social workers (21.8%). Most participants utilized more than one of these means. As previously noted, 42% reported that they were still currently in therapy of some sort for same-sex attraction.

SOCE efficacy

To determine the effectiveness of SOCE we compared the respondents’ ratings on each of the dimensions of sexual orientation before and after SOCE intervention. Table 2 presents the summary results. For all three components of sexual orientation—attraction, identification and behavior—average same-sex orientation in the sample significantly declined following SOCE intervention. Mean sexual attraction dropped over half a standard deviation (-.56), from 5.7 to 4.1 on the Kinsey scale. Same-sex identification dropped almost a third (-.31) of a standard deviation. Homosexual sex behavior dropped by a quarter (-.26) of a standard deviation. Effect sizes in this range are considered modest or moderate.

Other aspects of sexual desire, including kissing, ideation, and a desire for romantic intimacy, decreased significantly with regard to homosexual partners but increased with regard to heterosexual partners following exposure to SOCE. Heterosexual sex behavior also increased slightly. Unlike decreased homosexual sex, increased heterosexual sex is not necessarily a goal of SOCE intervention.

Table 3 decomposes the overall change in the components of sexual orientation into four distinct outcomes for participants: negative change, meaning that same-sex attractions, etc., were increased following SOCE; no change; partial remission, which indicates movement toward the heterosexual end of the scale after SOCE; and full remission, which indicates that the respondent rated his attraction, etc., as “heterosexual” or “almost entirely heterosexual” following but not prior to SOCE.

Table 3. Change in Attraction, Identification and Behavior following SOCE (n=125).

| Attraction | Identification | Behavior

(Homosexual Sex) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| % (S.E.) | % (S.E) | % (S.E) | |

| Initial Mean | 5.7 | 4.8 | 2.4 |

| Negative change | 4.0 (1.8) | 9.6 (2.6) | 8.1 (2.5) |

| No change | 27.4 (4.0) | 36.0 (4.3) | 47.2 (4.5) |

| Partial remission | 54.8 (4.5) | 40.0 (4.4) | 18.7 (3.5) |

| Full remission | 13.7 (3.1) | 14.4 (3.2) | 26.0 (4.0) |

| Current Mean | 4.1 | 3.6 | 1.5 |

| Initial to Current Difference | -1.6 | -1.2 | -.9 |

| P: Difference t-test | .000 | .000 | .000 |

SOCE, sexual orientation change efforts. S.E., Standard Error. P, P-value, which expresses the probability of obtaining test results at least as extreme as the results actually observed if there was no difference between the initial and current means.

This range of outcomes allows a closer interpretation of SOCE efficacy. A substantial proportion of participants reported achieving some remission, either partial or full, of unwanted same-sex attraction (69%), identification (54%) and behavior (45%). If efficacy means full remission, only about one in seven SOCE participants (13.7-14.4%) achieved full remission of unwanted attraction or identification, and one in four (26%) experienced full remission of unwanted homosexual sex behavior. For a substantial proportion of respondents, however, SOCE exposure was associated with no effect (27-47%) or even a negative effect (4-10%) on unwanted same-sex orientation.

Interactions with marriage and ongoing therapy

Another measure of perceived efficacy in this sample of highly religious men may be the extent to which sexual activity is conditioned on marriage. For heterosexual sex, this is true for them almost without qualification, although it improves following SOCE: 95% of unmarried respondents reported no heterosexual sex activity prior to SOCE; after SOCE this proportion rose to 99%. The same is not true for homosexual sex. Table 4 presents the numbers.

Table 4. Percent engaging in homosexual sex before and after SOCE, by marriage (n=125).

| Unmarried | Married | |

|---|---|---|

| Prior to SOCE | 47.7 | 70.6 |

| Following SOCE | 27.4 | 13.7 |

| P: Difference t-test | .000 | .000 |

SOCE, sexual orientation change efforts. P, P-value, which expresses the probability of obtaining test results at least as extreme as the results actually observed if there was no difference between percent prior to SOCE and following SOCE.

Prior to SOCE participation, the large majority of married men (71%) engaged in homosexual sex. After SOCE, that proportion plummeted to only 14%, and was only about half as prevalent among the married men as among unmarried men. From the standpoint of the men in the sample, one of the most important indications of perceived SOCE efficacy may be its association with drastically reduced unwanted same-sex activity which conflicts with the religious norms of their marriages.

Table 5 tests this effect, showing the same range of change outcomes as presented in Table 3, but only for the minority of men who were continuously married both prior to and following SOCE. This presentation removes any interaction of sexual activity with marital status and isolates the men in the sample who were most likely to have the reduction or elimination of same-sex activity as a goal of SOCE.

Table 5. Change in Attraction, Identification and Behavior following SOCE, continuously married only (n=32).

| Attraction | Identification | Behavior

(Homosexual Sex) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | |

| Initial Mean | 5.1 | 4.1 | 2.9 |

| Negative change | 0 | 6.1 (4.2) | 0 |

| No change | 39.4 (8.6) | 45.5 (8.8) | 37.5 (8.7) |

| Partial remission | 36.4 (8.5) | 27.3 (7.9) | 18.8 (7.0) |

| Full remission | 24.2 (7.6) | 21.2 (7.2) | 43.8 (8.9) |

| Current Mean | 3.8 | 3.1 | 1.5 |

| -1.3 | -1.0 | -1.4 | |

| P: Difference t-test | .000 | .001 | .000 |

SOCE, sexual orientation change efforts. S.E., Standard Error. P, P-value, which expresses the probability of obtaining test results at least as extreme as the results actually observed if there was no difference between the initial and current means.

Comparing Table 5 with Table 3, it can be seen that for all three components of sexual orientation the percent of continuously married men ( Table 5) who achieved full remission was higher than was true for the full sample ( Table 3). Compared to only 14% of the entire sample, a quarter (24%) of married men reported full remission of attraction and a fifth (21%) full remission of identification. A total of 44% of the married men, but only 26% of the entire sample, reported full remission of homosexual sex following SOCE. Negative change was also reduced among the married men for all three components, being eliminated entirely for attraction and homosexual sex. By these measures, participants reported SOCE to have been somewhat more efficacious among married men.

Not surprisingly, duration of therapy also interacted with SOCE efficacy in the sample. Just under forty-two percent (41.9%) of the respondents indicated that they were still in therapy for unwanted same-sex attraction. These men, in effect, were still undergoing SOCE, a tacit acknowledgement that in many cases their therapeutic goals had not yet been achieved, and at any rate SOCE was incomplete. Table 6 compares outcomes for these men with their counterparts who were no longer in SOCE therapy.

Table 6. Change in Attraction, Identification and Behavior following SOCE by current therapy participation (n=52) or not (n=72).

| Attraction | Identification | Behavior

(Homosexual Sex) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Still currently in therapy? | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | |

| Initial mean | 5.9 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 2.5 | 2.3 |

| Negative change | 2.0 (2.0) | 5.6 (2.7) | 9.6 (4.1) | 9.7 (3.5) | 7.7 (3.7) | 8.6 (3.4) |

| No change | 33.3 (6.7) | 22.2 (4.9) | 30.8 (6.5) | 38.9 (5.8) | 46.2 (7.0) | 47.1 (6.0) |

| Partial remission | 52.9 (7.1) | 56.9 (5.9) | 48.1 (7.0) | 34.7 (5.7) | 25.0 (6.1) | 14.3 (4.2) |

| Full remission | 11.8 (4.6) | 15.3 (4.3) | 11.5 (4.5) | 16.7 (4.4) | 21.2 (5.7) | 30.0 (5.5) |

| Current mean | 4.3 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| Mean change | -1.6 | -1.6 | -1.3 | -1.2 | -0.9 | -0.9 |

| P: Difference t-test | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | . 000 |

SOCE, sexual orientation change efforts. S.E., Standard Error. P, P-value, which expresses the probability of obtaining test results at least as extreme as the results actually observed if there was no difference between the initial and current means.

Column percentages may not total exactly 100 due to rounding.

Overall mean change for those still undergoing therapy was no different than for those who had completed or otherwise discontinued therapy. Both those still in therapy and those not currently in therapy reported a mean reduction following SOCE of 1.6 in same-sex attraction, of 1.2-1.3 in identification, and of.9 in homosexual sex. Those still in therapy, however, began with a higher mean score on each of these dimensions, meaning that their current level of homosexual orientation was still higher than those who are no longer in therapy. On all three dimensions, a smaller proportion of the men still in therapy had achieved full remission. On all three dimensions, for the men who were no longer in therapy the rate of full remission was higher than that shown in Table 3.

Table 7 combines the marriage and continuing therapy interactions, showing the effectiveness of SOCE among the 32 married men in the sample distinguished by whether they were still in therapy. Despite the smaller cell sizes, all groups still experienced significant reduction in all three elements of same-sex orientation. For all three elements, full remission was more frequent for the continuously married men who had completed therapy than for either all married men regardless of therapy status ( Table 5) or all men who had completed therapy regardless of marital status ( Table 6), indicating that the two interactions were independent and additive. For this group, over a quarter achieved full remission of attraction and identity, and over half achieved full remission of unwanted same-sex behavior. At least half attained full or partial remission of all three elements.

Table 7. Change in Homosexual and Heterosexual Behavior following SOCE by current therapy participation, continuously married only (n = therapy 14, not in therapy 18).

| Attraction | Identification | Behavior

(Homosexual Sex) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Still in therapy? | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | |

| Initial mean | 5.1 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 3.2 |

| Negative change | 0 | 0 | 7.1 (7.1) | 5.6 (5.6) | 0 | 0 |

| No change | 57.1 (13.7) | 22.2 (10.0) | 42.9 (13.7) | 44.4 (12.1) | 50.0 (13.9) | 23.5 (10.6) |

| Partial remission | 21.4 (11.4) | 50.0 (12.1) | 35.7 (13.3) | 22.2 (10.1) | 21.4 (11.4) | 17.6 (9.5) |

| Full remission | 21.4 (11.4) | 27.8 (10.9) | 14.3 (9.7) | 27.8 (10.9) | 28.6 (12.5) | 58.8 (12.3) |

| Current mean | 4.2 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 1.4 |

| Mean change | -.9 | -1.8 | -.8 | -1.2 | -0.8 | -1.8 |

| P: Difference t-test | .015 | .000 | .027 | .008 | .01 | . 000 |

SOCE, sexual orientation change efforts. S.E., Standard Error.. P, P-value, which expresses the probability of obtaining test results at least as extreme as the results actually observed if there was no difference between the initial and current means.

Column percentages may not total exactly 100 due to rounding.

Integration of sexuality

Another method of assessing therapeutic efficacy is by the integration of psychological characteristics in the self. Unlike the heterosexual majority, for sexual minorities the spheres of sexual attraction (who one desires to have sex with), sexual identity (how one defines their sexual orientation) and sexual behavior (who one actually has sex with) are often incongruent. Michael et al., in a large representative study of the U.S. sexual minority population, reported that among sexual minority men who reported either same-sex desire, behavior or identification, only 24% incorporated all three aspects in their identity (Michael et al., 1994, p. 42).

As Table 8 shows, exposure to SOCE was associated with improved correlation among attraction, identification and behavior for the men in the sample. Prior to SOCE, attraction and identification were correlated at .63, and behavior was uncorrelated with both identification and attraction. Following SOCE, all three elements were significantly correlated, and the correlation of attraction and identification had increased to .83.

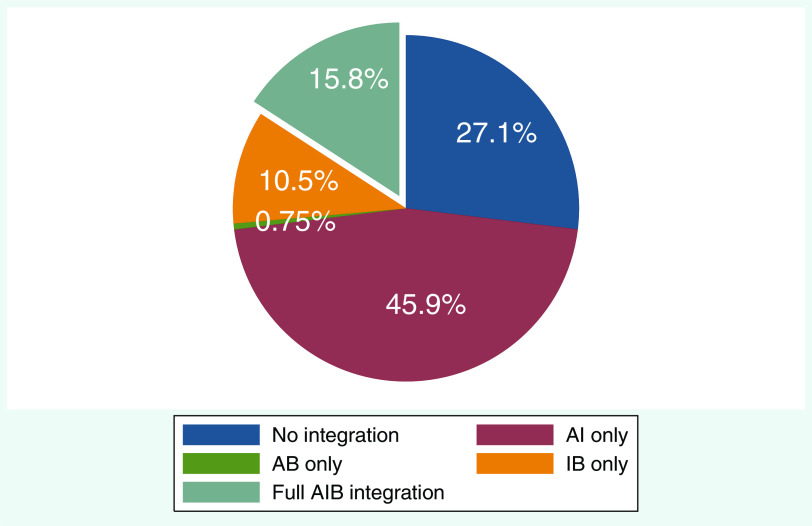

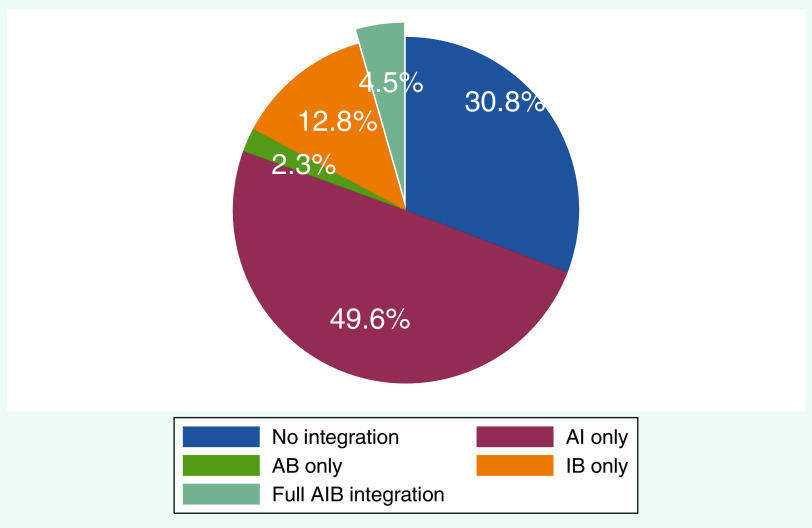

Figures 1 and 2 report the integration of all three aspects of sexual identity prior to and following SOCE exposure in percentage terms for the participants in the current study. Only 4.8% of participants reported the full integration of all three aspects of sexual identity prior to SOCE. Following SOCE this proportion had increased to 15.8%, or 3 times higher. The percentage of participants who reported congruence for only two aspects declined by 7.5% and those reporting no integration at all dropped by 3.7%. In addition to change efficacy, undergoing SOCE is followed by more persons experiencing greater integration of their sexual orientation identity.

Figure 1. Integration of the three aspects of sexual identity prior to SOCE exposure.

A, Attraction. I, Identification. B, Behavior. SOCE, sexual orientation change efforts.

Figure 2. Integration of the three aspects of sexual identity following SOCE exposure.

A, Attraction. I, Identification. B, Behavior. SOCE, sexual orientation change efforts.

Positive and negative psychosocial change

Table 9 presents the participants’ reports of positive and negative changes they experienced as a result of SOCE related to six psychosocial areas: self-esteem, social functioning, depression, self-harm, suicidality, and alcohol or substance abuse. For all six areas the participants experienced both positive and negative changes, however the positive changes were stronger and more widely distributed than the negative changes. The positive changes affected from 17% (for alcohol abuse) to 94% (for self-esteem) of participants, whereas the negative changes were reported by only 5% (for alcohol abuse) to 33% (for depression) of participants. The experience of marked or extreme positive changes ranged from 12% to 61%, while equally strong negative changes only ranged from 1% to 5%. For all six areas the net change, which is the summative index of both positive and negative changes, was a positive number greater than zero. This indicates that, considering both positive and negative changes, the net effect of SOCE for each area was positive. The strongest net positive effect was for depression. Almost three-fourths (73.2%) of respondents reported positive changes in depression due to SOCE, while two-thirds (66.1%) reported no negative changes in depression. The smallest net positive effect was for alcohol or substance abuse. Only 16.9% of participants reported positive changes in this area due to SOCE, although less than 5% (4.8%) experienced corresponding negative changes. Only 2.4% of participants experienced marked or extreme negative changes in suicidal thoughts or attempts as a result of SOCE, while nine times that number (21.8%) experienced similarly strong positive changes in suicidality.

Table 9. Summary of positive and negative changes in six other areas of psychosocial function as a result of SOCE (in percent).

| Self-esteem | Social functioning | Depression | Self-harm | Suicidality | Alcohol/

substance abuse |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | % (S.E.) | |

| Positive changes | ||||||

| None/Not

applicable |

5.6 (2.1) | 9.7 (2.7) | 26.8 (4.0) | 53.2 (4.5) | 62.1 (4.3) | 83.1 (3.4) |

| Slight or

Moderate |

33.1 (4.2) | 39.5 (4.4) | 38.2 (4.4) | 20.2 (3.6) | 16.1 (3.3) | 4.8 (1.9) |

| Marked or

Extreme |

61.3 (4.4) | 50.8 (4.5) | 35.0 (4.3) | 26.6 (4.0) | 21.8 (3.7) | 12.1 (2.9) |

| Negative changes | ||||||

| None/Not

applicable |

77.4 (3.8) | 79.0 (3.7) | 66.1 (4.3) | 88.0 (2.9) | 83.1 (3.4) | 95.2 (1.9) |

| Slight or

Moderate |

21.0 (3.7) | 16.9 (3.4) | 29.0 (4.1) | 8.9 (2.6) | 14.5 (3.2) | 4.0 (1.8) |

| Marked or

Extreme |

1.6 (.01) | 4.0 (1.8) | 4.8 (1.9) | 3.2 (1.6) | 2.4 (1.4) | 0.8 (0.8) |

| Net Change

(95% C.I.) |

2.4(2.14-2.69) | 2.0

(1.74-2.26) |

1.26(.95-1.57) | 1.03(.73-1.33) | 0.76(.46-1.05) | 0.43(.20-.66) |

| P: Net Change

not = 0 |

.0000 | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | .0000 | .0004 |

The question asked, “As a result of your change efforts, indicate the positive (negative) changes you have noticed in the following areas.” Response options were “None”, “Not applicable”, “Slightly”, “Moderately”, “Markedly”, or “Extremely so” [sic].

SOCE, sexual orientation change efforts. S.E., Standard Error; C.I., Confidence Interval; P, P-value, which expresses the probability of obtaining test results at least as extreme as the results actually observed if there was no Net Change.

Discussion

We analyzed data from 125 U.S. men who experienced SOCE to determine the extent to which they reported shifts in their unwanted same-sex attractions, behaviors, and identities as well as how psychologically harmful or helpful they perceived their SOCE to have been. We discuss our findings in terms of changes in sexuality, effects of heterosexual marriage, and impact on psychological well-being.

Changes in sexuality

Participants on average reported significant reductions in all three components of same-sex sexual orientation in line with their SOCE goals. Same-sex sex, sexual ideation, desire for same-sex intimacy, and homosexual kissing all decreased significantly following SOCE, while the heterosexual counterparts of these measures all increased significantly. While the overall change in each dimension of sexuality was small to modest, together they resulted in a three-fold increase in congruence among all three components of sexual orientation, from 5% to 17%, following SOCE ( Figures 1 and 2). The increased pairwise correlations among the components of sexual orientation also suggest greater integration among them. Virtually all of the increased integration was around increased heterosexual behavior, identity and attraction. Significantly for the question of self-report bias, although the underlying changes were self-reported, the increased congruence among the components of sexual orientation was not itself reported by participants. It is a collective change in the sample population that could not have been generally recognized by the sample participants. One of the major distinctions between the heterosexual majority and the non-heterosexual minority population is that for the former the components of sexual identity are far more commonly congruent (Michael et al., 1994). For this minority of our participants, it appears that an effect of SOCE participation may be not only to increase one or more aspects of heterosexual affect but also to organize the sexual self more fully around heterosexual desire and expression.

These results support a middle position between the opposing extremes that therapy-assisted change in sexual orientation is never possible or that such change is readily or widely accessible to sexual minority persons. On the one hand, our findings are consistent with converging evidence from twin, genome-wide association studies, population studies and narrative reports that sexual orientation 1) is not an immutable genetic trait, influenced approximately twice as much by environment as by genetic inheritance ( Diamond & Rosky, 2016; Ganna et al., 2019; Polderman et al., 2015); 2) is observed to be changeable, even fluid, for some over the life course (Diamond, 2016); and 3) is reported to change under strong religious influence (Lopez & Edelman, 2015; Williams & Woning, 2018). On the other hand, our findings support prior evidence that sexual orientation is not usually or easily changeable. Although about 14% of the sample indicated a complete diminishing of same-sex attractions and identification, and 26% reported they no longer engaged in same-sex sexual behavior, larger proportions indicated “No change” on all of these dimensions, and the most common change overall was to a state of bisexuality, not heterosexuality.

Moreover, if genetic evidence that the Kinsey scale improperly imposes a homosexual-to-heterosexual range on what is a more complex phenomenon is accurate (Ganna et al., 2019), then interpreting a transition from homosexuality to bisexuality as a move toward “greater heterosexuality” may not be appropriate. It is possible, as Bailey has suggested, that for men sexual attraction may be much less susceptible to change, if at all, than are sexual identity and behavior ( Bailey et al., 2016), though our findings of increased congruence following SOCE may suggest otherwise. Genetic complexity also suggests the possibility of multiple aetiologies or subtypes of non-heterosexual orientation, in which case it is quite possible that some persons may be able to transition from one sexual orientation to another without much difficulty, but that for other sexual minority persons, whether for innate or psychological reasons, change is difficult to impossible. If persons who seek therapy to help change are more likely to be in the latter group, as seems plausible, then the clinical population is self-selected for resistance to change. This may explain why research based on clinical samples has generally concluded that change is unlikely, if possible at all, while population studies have documented a relatively large amount of desistance from minority sexual orientation over the life course.

Effects of marriage

When we examined these overall findings through the lens of participants’ marital status, some important results emerged. Heterosexually married sexual minority men reported engaging in more same-sex behavior prior to SOCE and less same-sex behavior subsequent to SOCE than their unmarried counterparts. This may suggest that maintaining and strengthening their heterosexual marriage was a significant motivating factor in our participants’ decision to pursue SOCE. We additionally discovered that continuously married participants who were no longer engaged in SOCE reported greater reductions in their same-sex attractions and more heterosexual identification than their married counterparts who were still pursuing SOCE. This may indicate that the married participants no longer involved in SOCE felt they had sufficiently met their goals for change and therefore had ended their purposeful efforts.

We also found that the post-SOCE correlations between attractions, behavior, and identification were significantly higher than the pre-SOCE associations between these variables. For married participants, this may reflect their perception of an improved ability to function within their traditional marriage. In their study of mixed orientation marriages (MOMs), Yarhouse, Pawlowski, and Tan (2003) reported that the sexual minority spouses experienced notable shifting toward less same-sex attractions and greater opposite sex-attractions. Although heterosexual marriage should not be recommended as a solution to same-sex attractions, for some sexual minorities in MOMs, their marriage may provide an avenue for exploring the degree to which their sexuality is fluid and subject to movement toward a greater degree of heterosexuality. In general, our results are in line with such findings and speak to the particular benefit the married men in our sample reportedly derived from their SOCE experience.

Psychological well-being

Unlike most studies in this literature, the survey utilized in our study assessed for both positive and negative changes related to SOCE exposure in several indices of psychological well-being. This meant that participants were encouraged to acknowledge the full spectrum of potential mental health outcomes. Overall, we found that a large majority of these sexual minority men perceived their engagement in SOCE to enhance their well-being. Less than 5% of participants reported experiencing negative changes. Reports of positive change were stronger and more widely distributed than those of negative change, most strongly for depression, but also for self-esteem, social functioning, self-harm, suicidality, and alcohol/substance abuse. Of note given accounts of increased suicidality due to SOCE exposure ( Meanley et al., 2020; Salway et al., 2020), participants in this study reported nine times more (21.8%) marked or extreme positive effects of SOCE on suicidal thoughts or attempts than they reported a similar degree of negative effects (2.4%).

Our findings concur with those of Jones and Yarhouse (2011), who reported the SOCE experience of their sample over time led to modestly improved distress levels and countered “… any absolute claim that attempted change is likely to be harmful in and of itself” (p. 425). The results pertaining to depression also approximate the reports of participants in Spitzer’s (2003) study. The occurrence of such discrepant findings regarding SOCE exposure deserves a more plausible explanation than that of the universal self-deception or falsification of SOCE benefits among sexual minorities who report them ( Spitzer, 2012). We turn to the consideration of this issue now.

Harmonizing the SOCE literature

The somewhat striking bifurcation in findings pertaining to SOCE has received minimal attention within the literature. Most common are attempts by opponents and proponents of change-oriented goals to ignore or invalidate consumer accounts that are not in keeping with their experiences of SOCE or the experiences of sexual minorities within their social networks. It is important to develop testable explanations for the apparent divergence in SOCE reports, particularly as findings purporting SOCE harms are currently being utilized to legally restrict therapeutic options. Should there be credibility to reports of significant SOCE benefits and negligible harms, then the legitimacy of broad bans on professional and religious practice and speech could be brought into question. In light of this need, we propose a plausible explanation to harmonize this literature: Researchers are studying very different subpopulations of sexual minorities, distinguished in large part by their different experiences of contemporary, speech-based forms of SOCE, which should not be generalized to all sexual minorities.

As early as 2002, Shidlo and Schroeder observed a fundamental truth about many consumers of SOCE, stating, “… we have found that conversion therapists and many clients of conversion therapy steadfastly reject the use of lesbian and gay” (p. 249, authors’ emphases). In fact, an emerging literature now suggests this rejection of an LGBT identity may be a marker for a constellation of characteristics this sexual minority subgroup often report. These individuals appear to be more active in conservative religious settings, full members of their church, less sexually active, more likely to be single and celibate or in mixed orientation relationships, less accepting of their same-sex attractions, experience greater opposite sex attractions, and place more importance on a family and child centered life ( Lefevor et al., 2020). They also report modest to moderate helpfulness of change-oriented psychotherapy goals compared to LGB identified individuals, who report modest to moderate harmfulness (Rosik et al., 2020). However, contrary to conventional wisdom, sexual minorities who rejected an LGB identity did not appear to report more adverse psychosocial health than those who had adopted an LGB identity ( Lefevor et al., 2020). These subgroups also reported similar degrees of resolution of any conflict between their religious and sexual identities.

Examining the recruitment methods and sample characteristics of the aforementioned SOCE studies supports the hypothesis that researchers have likely investigated only one of these sexual minority subgroups at the expense of the other. Samples are often exclusively or mostly dominated by LGB identified participants ( Blosnich et al., 2020; Bradshaw et al., 2015; Flentje et al., 2014; Meanley et al., 2020; Ryan et al., 2020; Salway et al., 2020) or by participants with a likelihood of much lower levels of LGB identification given recruitment venues ( Jones & Yarhouse, 2011; Karten & Wade, 2010; Spitzer, 2003). SOCE researchers tend to recruit participants through the venues and networks most easily accessible to them; hence, samples usually reflect this selection bias. Several studies have recruited most if not all of their participants via LGB identified networks and venues (Flentje et al., 2014; Ryan et al., 2020) or networks and venues inhabited by those pursuing change ( Jones & Yarhouse, 2011; Karten & Wade, 2010; Spitzer, 2003). Some studies have attempted to recruit participants from both change-oriented and gay-affirming networks (Shildo & Schroeder, 2002; Bradshaw et al., 2015; Dehlin et al., 2015), but these efforts may have been hampered by the lack of an ideologically diverse research team that would generate trust and improve participation among sexual minorities in change-oriented networks, leading to samples with large numbers of participants who are alienated from their religious communities. Relatedly, Meanley et al. (2020) noted that those participants who did not complete survey responding and hence were excluded from their analyses were disproportionally non-LGB identified.

Our findings correspond with results reported from similar studies involving less prevalent LGB-identified participants recruited through change-oriented networks. We acknowledge our results do not provide a complete understanding of SOCE experiences among sexual minorities. Professional and social polarization around SOCE currently interfere with the production of ideologically diverse scholarship on this topic that might enable the identification and dissemination of areas of consensus across sociopolitical perspectives. Examples of likely candidates for consensus agreement regarding SOCE might include the avoidance of aversive techniques, promises of change, and coercive processes. Until this ideological and political divide is overcome, the current state of SOCE research may be compared to two groups who study marital counseling, one of which investigates consumers who have maintained their marriage and the other who examines persons who have since divorced. Neither group is likely to possess the whole truth about the relative benefits and risks of the treatment in focus.

Perhaps the clearest indicator of this divide is the sharply divergent religiosity reported by change-oriented and LGB-identified samples. Fully 88% of our participants reported attendance at religious services weekly or more often, and only 2.4% reported attending rarely or never. By contrast, in a recent population sample of LGB-identified sexual minorities only 9% reported at least weekly religious service attendance and 69% reported attending seldom or never (Meyer, 2020, p. 324). The former are far more religiously active and the latter far less religiously active than are Americans in general, of whom 33% reported attending religious services at least weekly and 31% seldom or never in 2016 ( Pew Research Center, 2019). It is possible that the prospect of change or stability in sexual orientation is linked to the notably high religiousness of the change-oriented sample and the notably low religiousness of the LGB-identified sample. Future research that incorporates both populations could help to clarify this possibility.

Ideally, future SOCE research will consider this current division in the field and pursue ways to mitigate the limitations this imposes on the science, including the formation of ideologically diverse research teams (e.g., Lefevor et al., 2019). Also recommended are recruitment strategies that either employ population-based samples able to identify sexual minorities who reject LGB identities or purposefully seek out sexual minorities not LGB identified for sample inclusion. In general, the integrity of science and the welfare of all sexual minorities will be better served by greater communication and collaboration among opponents and proponents of SOCE.

Limitations

Interpretation of our findings must be placed within the context of the study’s limitations. Our sample consisted entirely of men, most of whom were white, affluent, well-educated, highly religious, and overrepresented the Mormon faith, as is common to this literature (e.g., Karten & Wade, 2010). This sample is clearly not statistically representative of the general sexual minority population. The sample was not randomly drawn, therefore inferential tests cannot indicate quantitative representativeness of any population. They may indicate substantive representativeness to the extent that the sample of this study is plausibly characteristic of the general group of persons seeking SOCE intervention. As such, our findings should not be generalized, especially in reference to sexual minority women and those who are not highly religious.

The self-report nature of our data means that there is the possibility of an unknown degree of recall bias in favor of positive SOCE accounts. In addition, the single-item nature of many of our variables, common for exploratory studies, precludes our ability to establish their psychometric properties. These measurement limitations also suggest caution in interpreting our findings, although they are nearly ubiquitous in the SOCE literature and have not prevented other studies from being widely cited (e.g., Ryan et al., 2020; Shildo & Schroeder, 2002; Bradshaw et al., 2015). Some of our analyses (i.e., regarding marriage) utilized small sample sizes that may have been underpowered and placed limits on the reliability of these results.

Our findings cannot be definitive regarding any assertion that sexual orientation can change, only that some highly religious men report such changes, the pursuit of which they generally do not perceive to have been harmful. Since just under 42% of our sample was still pursing SOCE at the time of the survey, it is possible that some of these men may have later given up their pursuit of change and came to feel differently about their SOCE experience. Critiques of positive SOCE accounts often express concerns about later changes in perceptions of SOCE among consumers who are still pursuing or recently completed SOCE. Alternatively, they express concerns about recall bias with beneficial claims from consumers whose experiences of SOCE occurred years ago ( APA, 2009). This may betray a general unwillingness to consider the possibility some sexual minorities could actually have lasting positive SOCE experiences. In this regard, we note that most of our participants reported similar levels of desired change from their SOCE whether they were still pursuing change or had completed their pursuit of change several years earlier. Still, we do not have a complete picture of what characteristics may be associated with reported change via SOCE, so it cannot be assumed that most highly religious and motivated men who seek SOCE will perceive an experience of change. Clinicians who work with clients having similar backgrounds and motivations should neither create expectations of complete (categorical) change nor of the strict immutability of same-sex sexuality.

Conclusion

We analyzed a sample of 125 men exposed to SOCE to investigate the perceived efficacy and safety of such change efforts in modifying unwanted same-sex attractions, behaviors, and identities. On average, participants reported significant changes in their sexuality in line with their SOCE goals, possibly contributing to an enhanced integration or congruence among these dimensions. The maintenance of religious norms of sexual fidelity within and abstinence without heterosexual marriage appeared to be an important motivating factor for many in our sample, and our findings are consistent with the inference that most participants found SOCE beneficial in this regard. We also found pursuit of SOCE to be associated with enhanced psychological well-being for a large majority of participants, with negative effects being reported by less than 1 in 20 consumers. While our findings preclude strong assertions that therapy-assisted change in sexual orientation is never possible, they also do not support strong assurances that therapy-assisted change is generally achievable in the sexual minority population. The polarization within organized psychology over SOCE appears to have led to insular research that treats one subgroup of sexual minorities as representative of the whole population, with detrimental consequences for accurately comprehending the complexities of sexual orientation change among these individuals.

Data availability

Underlying data

Harvard Dataverse: Replication Data for: Efficacy and Risk of Sexual Orientation Change Efforts (SOCE) in a U.S. Sample of 125 Sexual Minority Men, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RGNGNH ( Sullins, 2021).

The project contains the following underlying data:

-

•

PLS2011 Codebook.rtf. Word-compatible codebook generated from SPSS file documentation.

-

•

PLS2011 Data USOnly.sav. Electronic data file in SPSS Format.

Extended data

Harvard Dataverse: Replication Data for: Efficacy and Risk of Sexual Orientation Change Efforts (SOCE) in a U.S. Sample of 125 Sexual Minority Men, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RGNGNH ( Sullins, 2021).

The project contains the following extended data:

-

•

PLS Questionnaire 2011.pdf. Survey questionnaire.

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero “No rights reserved” data waiver (CC0 1.0 Public domain dedication).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Neil E. Whitehead, Ph.D., for helpful preliminary analyses and review comments.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

[version 1; peer review: 2 approved]

References

- American Psychological Association: Report of the Task Force on Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation. 2009. Reference Source

- Armelli JA, Moose EL, Paulk A, et al. : A response to Spitzer’s (2012) reassessment of his 2003 study of reparative therapy of homosexuality. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;41:1335–1336. 10.1007/s10508-012-0032-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley F: Model Law – Prohibiting Conversion Practices. 2019a, May 28. Reference Source 10.2139/ssrn.3398402 [DOI]

- Bradshaw K, Dehlin JP, Crowell K, et al. : Sexual orientation change efforts through psychotherapy for LGBQ individuals affiliated with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. J Sex Marital Ther. 2015;41(4):391–412. 10.1080/0092623X.2014.915907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich JR, Henderson ER, Coulter RWS, et al. : Sexual orientation change efforts, adverse childhood experiences, and suicide ideation and attempt among sexual minority adults, United States, 2016-2018. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(7):1024–1030. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehlin JP, Galliher RV, Bradshaw WS, et al. : Sexual orientation change efforts among current or former LDS church members. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62(2):95–105. 10.1037/cou0000011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flentje A, Heck NC, Cochran BN: Sexual reorientation therapy interventions: Perspectives of ex-ex-gay individuals. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health. 2013;17(3):256–277. 10.1080/19359705.2013.773268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gamboni C, Gutierrez D, Morgan-Sowada H: Prohibiting versus discouraging: Exploring mental health organizations varied stances on sexual orientation change efforts (SOCE). Am J Fam Ther. 2018;46(1):96–105. 10.1080/01926187.2018.1437572 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ganna A, Verweij KJH, Nivard MG, et al. : Large-scale GWAS reveals insights into the genetic architecture of same-sex sexual behavior. Science. 2019a;365(6456):eaat7693. 10.1126/science.aat7693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SL, Rosik CH, Williams RN, et al. : A Scientific, Conceptual, and Ethical Critique of the Report of the APA Task Force on Sexual Orientation. General Psychol. 2010;45(2):7–18. Retrieved May 31, 2011. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- Jones SL, Yarhouse MA: A longitudinal study of attempted religiously mediated sexual orientation change. J Sex Marital Ther. 2011;37(5):404–427. 10.1080/0092623X.2011.607052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karten EY, Wade JC: Sexual orientation change efforts in men: A client perspective. J Men Stu. 2010;18(1):84–102. 10.3149/jms.1801.84 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey AC, Pomeroy WR, Martin CE: Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. 1948; Philadelphia, Pa: W.B. Saunders. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefevor GT, Beckstead LA, Schow RL, et al. : Satisfaction and health with four sexual identity relationship options. J Sex Marital Ther. 2019;45:355–369. 10.1080/0092623X.2018.1531333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefevor GT, Sorell SA, Kappers G, et al. : Same-sex attracted, not LGBQ: The associations of sexual identity labeling on religiousness, sexuality, and health among Mormons. J Homosex. 2020;67(7):940–964 10.1080/00918369.2018.1564006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhard W, Lenhard A: Calculation of Effect Sizes. 2016a; Dettelbach (Germany): Psychometrica. 10.13140/RG.2.2.17823.92329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meanley S, Haberlen SA, Okafor CN, et al. : Lifetime exposure to conversion therapy and psychosocial health among midlife and older adult men who have sex with men. Gerontologist. 2020;60(7):1291–1302. 10.1093/geront/gnaa069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH: Generations: A Study of the Life and Health of LGB People in a Changing Society, United States, 2016-2019: Version 1 (Version v1) [Data set]. Inter-University Consortium Political Social Res. 2020a. 10.3886/ICPSR37166.V1 [DOI]

- Michael RT, Gagnon JH, Kolata GB, et al. : Sex in America: A Definitive Survey. 1994a; New York: Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Movement Advancement Project: Conversion “therapy” laws. Reference Source

- Bailey JM, Vasey PL, Diamond LM, et al. : Sexual Orientation, Controversy, and Science. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2016;17(2):45–101. 10.1177/1529100616637616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM: Sexual fluidity in male and females. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2016;8(4):249–256. 10.1007/s11930-016-0092-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM, Rosky CJ: Scrutinizing immutability: Research on sexual orientation and US legal advocacy for sexual minorities. J Sex Res. 2016;53(4–5):363–391. 10.1080/00224499.2016.1139665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganna A, Verweij KJH, Nivard MG, et al. : Large-scale GWAS reveals insights into the genetic architecture of same-sex sexual behavior. Science. 2019b;365(6456):eaat7693. 10.1126/science.aat7693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhard W, Lenhard A: Calculation of Effect Sizes. 2016b; Dettelbach (Germany): Psychometrica. 10.13140/RG.2.2.17823.92329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez R, Edelman R, (Eds.) Jephthah’s Daughters 2015; International Children’s Rights Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH: Generations: A Study of the Life and Health of LGB People in a Changing Society, United States, 2016-2019: Version 1 (Version v1) [Data set]. Inter-University Consortium Political Soc Res. 2020b. 10.3886/ICPSR37166.V1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michael RT, Gagnon JH, Kolata GB, et al. : Sex in America: A Definitive Survey. 1994b; Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center: In U.S., church attendance is declining: Detailed Tables. 2019. Reference Source

- Polderman TJC, Benyamin B, de Leeuw CA, et al. : Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat Genet. 2015;47(7):702–709. 10.1038/ng.3285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santero P: Change Effects in U.S. Men with Unwanted Same Sex Attraction after Therapy. [Psy.D. Dissertation]. 2011; Southern California Seminary. [Google Scholar]

- Williams K, Woning E, (Eds.) CHANGED: #Oncegay Stories. Equipped to Love. 2018. Reference Source

- Shidlo A, Schroeder M: Changing sexual orientation: A consumer’s report. Prof Psychol Res Prac. 2002;33(3):249–259. 10.1037/0735-7028.33.3.249 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL: Can some gay men and lesbians change their sexual orientation? 200 participants reporting a change from homosexual to heterosexual orientation. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32:403–417. 10.1023/A:1025647527010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL: Spitzer reassess his 2003 study of reparative therapy of homosexuality [Letter to the editor]. Arch Sex Behav. 2012. 10.1007/s10508-012-9966-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarhouse MA, Pawlowski LM, Tan ESN: Intact Marriages in Which One Partner Dis-identifies with Experiences of Same-Sex Attraction. Am J Family Therapy. 2003;31(5):375–394. 10.1080/01926180390223996 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sullins DP: Replication Data for: Efficacy and Risk of Sexual Orientation Change Efforts (SOCE) in a U.S. Sample of 125 Sexual Minority Men. Harvard Dataverse. 2021;V1. 10.7910/DVN/RGNGNH [DOI] [Google Scholar]