Abstract

COVID-19 not only threatens people’s physical health, but also creates disruption in work and social relationships. Parents may even experience additional strain resulting from childcare responsibilities. A total of 129 parents participated in this study. Parents of children with developmental disorders showed higher levels of parenting stress, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms than did parents of children with typical development. Parenting stress and health worries were positively related to mental health symptoms. The association between having a child with developmental disorders and mental health symptoms was mediated by parenting stress. This study provides a timely investigation into the stress and mental health of parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Implications on web-based parenting skills interventions, online psychological support services, and family-friendly policy initiatives are discussed.

Keywords: COVID-19, Health worries, Work and social disruption, Parenting stress, Mental health, Parents of children with developmental disorders

Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a global pandemic that has tremendously affected billions of people’s lives and livelihoods around the world (Nicola et al., 2020; Pfefferbaum & North, 2020). While the increase in the number of people infected with COVID-19 has been steady, the stress and pressure imposed by the pandemic continue to spread. The stress comes from not only the risk of infection and death, but also the disruption in daily routine and social connection (Palgi et al., 2020). Accumulating evidence indicates that there is a heightened risk of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic (Liu et al., 2020; Ran et al., 2020; Suen et al., 2020). Parents even experience additional strain resulting from childcare responsibilities (Spinelli et al., 2020). Nevertheless, there is a paucity of research examining how the lives and mental health of parents are affected by the pandemic, especially for those who have a child with developmental disorders (Ersoy et al., 2020; Stankovic et al., 2020).

Family Adjustment and Adaptation Response Model

The family adjustment and adaptation response (FAAR) model provides a framework for understanding the experience of distress in families in response to stressful life circumstances such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Patterson, 1988). The model posits that families engage in processes of adjustment and adaptation to balance the demands they face with their existing capabilities in order to maintain equilibrium in the family system. Demands are comprised of (1) stressors (i.e., discrete events of change due to normative developmental tasks and nonnormative events), (2) strains (i.e., ongoing tensions from hardship of unresolved/unresolvable prior stressors), and (3) daily hassles (i.e., minor disruptions of daily life) that interrupt normal family equilibrium (Patterson, 1988). Capabilities refers to the resources and behaviors utilized to cope with family demands. Both demands and capabilities can emerge from individual family members, a family unit, and/or community sources external to the family system (Patterson, 2002).

The FAAR model asserts that family functioning is at an optimal level when there is equilibrium between demands and capabilities (Patterson, 1988). Nevertheless, there are times when existing capabilities are inadequate to meet family demands (e.g., stressors, strains, and daily hassles). When this imbalance persists, a crisis may emerge in the family system, resulting in “an acute disruption of psychological homeostasis in which one’s usual coping mechanisms fail and there exists evidence of distress and functional impairment” (Roberts, 2005, p. 778). Family maladaptation can be manifested in poor health outcomes and impaired role functioning among family members (Patterson & Garwick, 1994).

Stressors Arising from the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Health-related concerns and worries are highly prevalent during the COVID-19 pandemic (Wright et al., 2020). People are preoccupied with beliefs about the dangerousness of COVID-19 and worries about their physical health (Taylor et al., 2020). Due to continuously growing infection rates across the world, people also express concern that they might be infected with COVID-19 (Suen et al., 2020). Recent studies indicated that parents experienced health worries regarding the need to protect their child and family from infection (Ersoy et al., 2020; Spinelli et al., 2020). Repeated exposure to the news about COVID-19 may also enhance health anxiety and concerns about being exposed to a potentially infectious environment, which can be a significant source of stress (Asmundson & Taylor, 2020).

In addition, there has been a considerable disturbance in work and social life during the COVID-19 pandemic (Nicola et al., 2020). With the introduction of social distancing measures, many people were required to work remotely from home. To minimize the risk of infection, they were expected to reduce social contact with friends and refrain from engaging in outdoor leisure activities and public gatherings (Courtemanche et al., 2020). In countries with high infection rates, a stay-at-home mandate was also issued during the lockdown period. People have suffered from not only abrupt disruption to their daily routine, but also loss of social support and recreational opportunities during the pandemic (Palgi et al., 2020).

The COVID-19 outbreak also exacerbates caregiving demands on parents. Since the outbreak, schools in many countries have been closed and face-to-face classes suspended in order to reduce social contact between students and interrupt the transmission of the coronavirus (Courtemanche et al., 2020). While school closures may reduce the risk of children contracting COVID-19, they pose tremendous stress and challenges for parents because the burden of childcare has shifted from teachers to parents. It was found that family disputes and parent–child conflict have escalated due to social distancing and home confinement during the pandemic (Chung et al., 2020). Working parents might even experience greater strain as they must balance work and childcare responsibilities. This not only puts parents at a higher risk of experiencing distress, but also hinders their ability to support their children (Spinelli et al., 2020).

Rearing a Child with Developmental Disorders as an Ongoing Family Strain

Developmental disorders are a heterogenous group of conditions with onset in infancy or childhood that affect single or multiple areas of development in children (including cognition, learning, speech and language, communication, and motor function) (World Health Organization, 2013). Examples of developmental disorders include autism spectrum disorders (ASD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), learning disorders, and language and speech disorders. As shown in previous studies (Chan et al. 2020; Hayes & Watson, 2013; Yorke et al., 2018), children with developmental disorders are likely to exhibit more emotional and behavioral problems (e.g., tantrums, aggression, and emotional outbursts) than those with typical development. They also exhibit deficits and delays in multiple domains of development, which contribute to a high degree of caregiving demands and require more intensive daily support.

Children with developmental disorders and their parents might be even more vulnerable to the impact of COVID-19 (Ersoy et al., 2020; Stankovic et al., 2020). A study on parents of children with special educational needs and disabilities showed that parents experienced worry about their own health and that of their children and observed extreme anxiety reactions in their children (e.g., irrational thinking, compulsive hand-washing, and sleep disturbance) (Asbury et al., 2020). Some also worried about who would look after their children if they were infected with COVID-19 themselves. In a qualitative study by Bent et al. (2020), parents of children with ASD expressed concerns about their children’s inability to adhere to social distancing practices because their children were less likely to be aware of personal space to minimize infections of COVID-19. Behavioral challenges of children with ADHD such as hyperactivity and fidgetiness, also reduced their compliance with hygiene procedures due to their impatience to complete or perform the procedures (Mutluer et al., 2020). In addition, other children with ASD might experience sensory sensitivity and more specifically tactile defensiveness, which could cause them discomfort in wearing masks over their faces and increase their risk of contracting COVID-19. This is evidenced by Stankovic et al. (2020) who found that 40% of parents of children with ASD indicated that their children had difficulties wearing protective masks or gloves. Some parents also found it difficult to explain the pandemic and safety precautions to their children with ASD, as their children’s receptive and expressive language skills were weaker than those of other children with typical development (Bent et al., 2020).

In addition, children with ASD and ADHD, who usually thrive with predictability and routine, were severely affected by school closures and the subsequent loss of structure and routine during the pandemic (Serlachius et al., 2020). A recent study by Stankovic et al. (2020) revealed that children with ASD showed worsening of autism symptoms and behavioral problems because their previously established routines were disrupted by the pandemic. The imposition of lockdown and the resulting uncertainty and instability also made children feel more anxious, agitated, and restless (Asbury et al., 2020). Their emotional and behavioral upheaval might place further strain on their parents, which was reflected by Colizzi et al. (2020) who noted that three-fourth of parents of children with ASD reported difficulties in managing their child’s daily activities, particularly free-time and structured activities. Although online classes were available in some regions, parents reported that their children with developmental disorders felt frustrated around adapting to online learning settings and required direct parental supervision (Bent et al., 2020). Based on the extant literature, it is possible that having a child with developmental disorders may confer a higher risk of COVID-19-related stress, including health worries, work and social disruption, and parenting stress.

Loss of Family Capabilities During the COVID-19 Pandemic

There was a severe interruption of care and support services for children with special needs during the pandemic, which further limited the resources available for families of children with developmental disorders and hindered parents’ ability to cope with COVID-19-related stress and ongoing family strains (Aishworiya & Kang, 2020; Serlachius et al., 2020). With the implementation of social distancing measures, special childcare centers were closed. In-person behavioral and therapeutic programs were also halted, which left parents with little external support and assistance (Lee et al., 2020). In a recent study by Pavlopoulou et al. (2020), 86% of 449 family caregivers of children with ASD in the UK reported that the needs of their children have not been addressed during the pandemic. Only half of the respondents had access to at least one type of specialist support and they indicated the services were neither timely nor sufficient (Pavlopoulou et al., 2020). It was also reported that children with ASD lost skills that were previously acquired or learned because of the discontinuation of behavioral intervention support and social distancing during the pandemic (Stankovic et al., 2020).

Prolonged home confinement, with consequent loss of instrumental support and companionship from extended family members, may also contribute to the erosion of family capabilities in supporting children with developmental disorders (Aishworiya & Kang, 2020). As there has been a lack of respite care, parents of children with developmental disorders often have to spend a substantial amount of time and effort meeting the demands of their children, for example by offering around-the-clock care and managing their children’s difficult behavior (Lee et al., 2020). Without access to support services and networks, parents might struggle to effectively fulfill their caregiving, educational, and therapeutic roles. Asbury et al. (2020) also noted that some parents of children with developmental disorders became overwhelmed by the new demands placed on them, including addressing their child’s learning and development needs, often alongside responding to the changes brought by the pandemic (e.g., alternate work arrangements, lockdown measures, and financial loss).

Effects of COVID-19 on Parent Mental Health

Chronic exposure to stressors and the lack of resources during the pandemic period can lead to disequilibrium and maladaptation in the family system, resulting in mental health problems among family members (Pfefferbaum & North, 2020; Wright et al., 2020). Research by Huang and Zhao (2020) indicated that the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep problems was higher among individuals who are preoccupied with thoughts related to the COVID-19 outbreak. In addition, social distancing measures were associated with heightened levels of psychological distress (Galea et al., 2020). This was also evident in the study by Spinelli et al. (2020), who found that parents who perceived more difficulties in dealing with quarantine showed higher levels of stress.

The mental health status and experience of parents of children with developmental disorders are of particular concern during the COVID-19 outbreak (Lee et al., 2020; Stankovic et al., 2020). There is ample empirical evidence showing that parents of children with developmental disorders experience significantly more stress and mental health problems than do those of children with typical development (Siu et al., 2019). Particularly, in a study by Masi et al. (2020), 76.1% of the parents of children with developmental disorders reported COVID‐19 had impacted their well-being. Ersoy et al. (2020) also showed that mothers of children with ASD reported higher levels of health anxiety as well as lower levels of dispositional hope and psychological well-being than those of children without ASD during the pandemic. It is plausible that the elevated levels of COVID-19-related stress would lead to poor mental health among parents of children with developmental disorders.

The Present Study

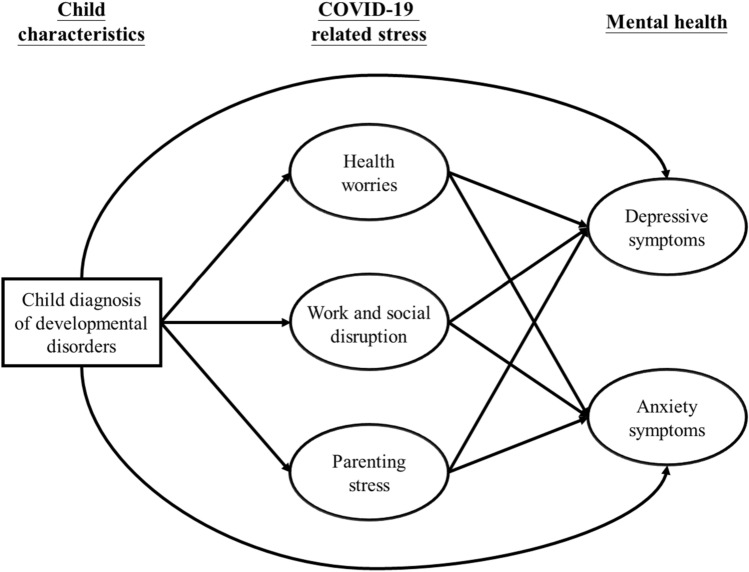

Based on the family adjustment and adaptation response model, this study aimed to (1) investigate and compare the prevalence of COVID-19-related stress and mental health problems (i.e., depressive and anxiety symptoms) between parents of children with developmental disorders and those of children with typical development, (2) examine the association of COVID-19-related stress with mental health problems, (3) propose and test a mediation model (see Fig. 1) in which the mental health disparities between parents of children with developmental disorders and those of children with typical development are explained by the greater levels of COVID-19 related stress experienced by parents of children with developmental disorders. It was hypothesized that parents of children with developmental disorders would show higher levels of COVID-19-related stress (i.e., health worries, work and social disruption, and parenting stress) than do parents of children with typical development. We also hypothesized that COVID-19-related stress would be positively associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms.

Fig. 1.

A hypothesized model of COVID-19-related stress and mental health in parents

Method

Sampling and Procedure

The present study was part of a larger study of mental health among parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Inclusion criteria for participants were (1) being parents and primary caregivers of children who were in late childhood (i.e., 8–10 years), (2) living in Hong Kong currently and over the past 6 months (during the COVID-19 pandemic), and (3) being able to read and understand Chinese. Parents of children with developmental disorders and parents of children with typical development were recruited from 12 mainstream primary schools in Hong Kong in May 2020. Integrated education (i.e., integrating children with special needs into ordinary schools) has been an official policy in Hong Kong since 1997. Children with mild-to-moderate developmental disabilities may attend ordinary schools where they can receive education with their peers with typical development in mainstream classrooms. Special education programs are provided to children with developmental disabilities in ordinary schools so that they can receive supplementary education and support services. Only when the nature or severity of the disability prevents the children from learning in regular education settings are they referred to special schools for intensive support services. As the present study was conducted in mainstream primary schools, it involved parents of children with mild-to-moderate developmental disabilities as well as parents of children with typical development.

Participants who met the inclusion criteria and expressed interest in the study were instructed to visit the study website. They first read the consent form that outlines the research background and design. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured for all participants. After providing informed consent, they were asked to complete the online questionnaire on the study website. The study was approved by the human research ethics committee of the first author’s institution.

Measures

COVID-19-related stress was assessed in three dimensions: (1) health worries, (2) work and social disruption, and (3) parenting stress. Since measures have not been developed and validated for assessing COVID-19-related stress in parents, we created nine items to capture the three dimensions of stressors. Health worries reflect the extent to which one is worried about COVID-19 infection. Items for health worries include “I am worried that I might be infected with COVID-19”, “I am worried that my family members and friends might be infected with COVID-19”, and “I am worried about being exposed to a potentially infectious environment”. Work and social disruption measures the extent to which participants’ daily life is affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Items include “My daily routine has been disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic”, “My work has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic”, and “I have reduced social contact with my friends during the COVID-19 pandemic”. In addition, three items were developed to assess parenting stress due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The items include “I have difficulty in taking care of my child”, “I have disputes with my child”, and “I experience strain in balancing work and childcare responsibilities”. The responses were ranked on 5-point Likert scale where 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, and 5 = almost always. Higher scores indicate more frequent exposure to COVID-19-related stressors. To provide a descriptive overview of COVID-19-related stress faced by parents, those who scored 3 or above were considered as having health worries, work and social disruption, and parenting stress. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89, 0.57, and 0.81 for health worries, work and social disruption, and parenting stress subscales, respectively. To examine the goodness-of-fit of the proposed factor structure, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using the full information maximum likelihood estimation. The results showed that the three-factor model had a good fit to the data, χ2 (24) = 501.85, p = .02, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.06. All items were significantly loaded on their respective factors (p < .001), with standardized factor loadings ranging from 0.46 to 0.94.

Depressive symptoms were measured by the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., 2001). The scale was used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms in the past two weeks. A sample item includes “feeling tired or having little energy”. Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The scale has been translated into Chinese and showed good psychometric properties (Wang et al., 2014). The continuous score of the PHQ-9 reflects the severity of the depressive symptoms, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. The scale can also be scored to provide a dichotomous diagnosis of probable clinical depression (Kroenke et al., 2001). A total score of 10 or above was used to indicate a probable diagnosis of clinical depression. Using the cutoff score of 10, the scale has a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 88% for detecting major depressive disorder (Kroenke et al., 2001). The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale in this study was 0.87.

Anxiety symptoms were assessed by the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire (GAD-7) (Spitzer et al., 2006). The scale measures the severity of anxiety symptoms in the past two weeks. A sample item includes “being so restless that it’s hard to sit still”. Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The scale has been translated into Chinese and validated for use with Chinese participants (He et al., 2010). The continuous score of the GAD-7 reflects the severity of the anxiety symptoms, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety symptoms. In addition, the scale can be scored to provide a dichotomous diagnosis of probable generalized anxiety disorder (Spitzer et al., 2006). A total score of 10 or above was used to determine probable generalized anxiety disorder. Using the cutoff score of 10, the scale has a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 82% for detecting generalized anxiety disorder (Swinson, 2006). The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale in this study was 0.91.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the demographics, COVID-19-related stress level, and mental health problems among parents. Skewness and kurtosis were calculated to check the normality of the study variables, following the criteria proposed by Weston and Gore (2006) (i.e., skewness ≤ ± 3.0 and kurtosis ≤ ± 10.0). The values of skewness and kurtosis for the study variables were all within acceptable ranges, indicating that the data were close to normal distribution.

Independent-sample t-tests and chi-square tests were conducted to examine differences in COVID-19-related stress (i.e., health worries, work and social disruption, and parenting stress) and mental health (i.e., depressive and anxiety symptoms) between parents of children with developmental disorders and parents of children with typical development. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to estimate the association between COVID-19-related stress and mental health. The analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted to test the hypothesized relationships between having a child with developmental disorders (as compared to having a child with typical development), COVID-19-related stress, and mental health, after controlling for parent demographics (i.e., gender, age, education level, monthly household income level, and number of children). In modeling the latent variables for COVID-19-related stress, we used the items from the respective subscales as indicators. The item parceling method was used to create three parcels for each of the latent mental health variables (i.e., depressive and anxiety symptoms). A measurement model was first tested to assess the degree to which the observed variables represented the latent variable in the hypothesized model (see Fig. 1). Then, we examined the hypothesized relationships among the latent variables in the structural model. The parameters of the model were estimated using the maximum likelihood estimation method. A number of fit indices were used to determine the fit of the model, including (1) the comparative fit index (CFI), (2) Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), (3) the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and (4) the standardized root-mean square residual (SRMR). CFI and TLI values of ≥ 0.90 indicate an acceptable model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). A RMSEA value of ≤ 0.06 is considered a close model fit, and a SRMR value of ≤ 0.08 indicates an excellent model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

The bootstrapping analysis was conducted using 1000 bootstrap samples to examine the indirect effects of having a child with developmental disorders (as compared to having a child with typical development) on depressive and anxiety symptoms among parents via the three COVID-19-related stress variables. To examine the significance of the indirect effects, bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. An effect was considered significant when the 95% CI did not contain zero. The above analyses were conducted with Mplus version 7.1.

Results

Participant Demographics

A total of 129 parents participated and completed the study. Most of them were female (92.2%, n = 119) and 7.8% (n = 10) were male. They had a mean age of 41.2 years (S.D. = 6.56). Slightly more than half of the parents (52.7%, n = 68) had secondary school or below as their highest level of education attainment, whereas 47.3% (n = 61) had completed post-secondary or tertiary education. About 29.5% (n = 38) had a monthly household income of HK$20,000 (US$2,580) or below, half (48.1%, n = 62) had an income of HK$20,000–HK$50,000 (US$2,580–US$6,450), and 22.5% (n = 29) had an income of more than HK$50,000 (US$6,50). One-third of the parents (34.9%, n = 45) had one child, and the remaining had two or more children (65.1%, n = 84).

About 39.5% (n = 51) of the parents indicated that their child had one or more developmental disorder(s). Most of the children had attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (28.7%, n = 37), followed by learning disorders (15.5%, n = 20), language and speech disorders (12.4%, n = 16), autism spectrum disorders (11.6%, n = 15), intellectual disabilities (3.1%, n = 4), visual impairment (2.3%, n = 3), hearing impairment (1.6%, n = 2), and physical disabilities (1.6%, n = 2).

COVID-19-Related Stress and Mental Health

More than half of the respondents showed health-related concerns, worrying that they (52.7%, n = 68) or their family members and friends (65.1%, n = 84) might be infected with COVID-19. Many of them (68.2%, n = 88) were also concerned that they might be exposed to a potentially infectious environment. The majority of the parents indicated that their daily routine (82.9%, n = 107) and work (72.1%, n = 93) have been disrupted or affected by the pandemic. About 93.0% (n = 120) reported that they have reduced social contact with their friends during the pandemic period. Most of the parents showed difficulty in taking care of their child (70.5%, n = 91) and even had disputes with their child (50.4%, n = 65) due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Two-thirds of them experienced strain in balancing work and childcare responsibilities (66.7%, n = 86).

Around 16.3% (n = 21) of the parents met the criteria for probable clinical depression, and 8.5% (n = 11) of them met the criteria for probable generalized anxiety disorder. The results of chi-square tests revealed that a significantly greater proportion of parents of children with developmental disorders (25.5%, n = 13) met the criteria for probable clinical depression (x2 = 5.25, p = .02), compared with parents of children with typical development (10.3%, n = 8). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of probable generalized anxiety disorder between parents of children with developmental disorders (13.7%, n = 7) and those of children with typical development (5.1%, n = 4) (x2 = 2.92, p = .09).

Independent-sample t-tests were conducted to examine differences in COVID-19-related stress and mental health between parents of children with developmental disorders and those of children with typical development. The results indicated that parents of children with developmental disorders showed significantly higher levels of parenting stress (t = 4.54, p < .001), depressive symptoms (t = 3.84, p < .001), and anxiety symptoms (t = 3.62, p < .001) than did their counterparts. No significant differences were observed in the levels of health worries and work and social disruption between the two groups of parents (ps > .05). Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations of study variables (N = 129)

| Health worries | Work and social disruption | Parenting stress | Depressive symptoms | Anxiety symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health worries | – | ||||

| Work and social disruption | 0.26** | – | |||

| Parenting stress | 0.19* | 0.42*** | – | ||

| Depressive symptoms | 0.11 | 0.18* | 0.45*** | – | |

| Anxiety symptoms | 0.28** | 0.18* | 0.50*** | 0.77*** | – |

| Skewness | 0.06 | − 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.96 | 1.22 |

| Kurtosis | 0.01 | − 0.34 | − 0.08 | 0.49 | 1.57 |

| Cronbach’s α | 0.89 | 0.57 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.91 |

| Parents of children with developmental disorders—mean (SD) | 7.92 (2.67) | 11.12 (2.47) | 9.63 (2.54) | 6.82 (4.66) | 5.86 (4.58) |

| Parents of children with typical development—mean (SD) | 8.44 (2.20) | 10.36 (2.15) | 7.56 (2.52) | 3.90 (3.92) | 3.24 (3.61) |

| Group difference—t-value | − 1.19 | 1.85 | 4.54*** | 3.84*** | 3.62*** |

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Health worries were positively associated with anxiety symptoms (r = 0.28, p = .001) but not depressive symptoms (r = 0.11, p = .22). Work and social disruption was positively related to both depressive symptoms (r = 0.18, p = .04) and anxiety symptoms (r = 0.18, p = .04). Parenting stress was also positively related to depressive symptoms (r = 0.45, p < .001) and anxiety symptoms (r = 0.50, p < .001). As shown in Table 1, there were also positive associations between health worries, work and social disruption, and parenting stress (ps < .05).

A Mediation Model of COVID-19-Related Stress and Mental Health

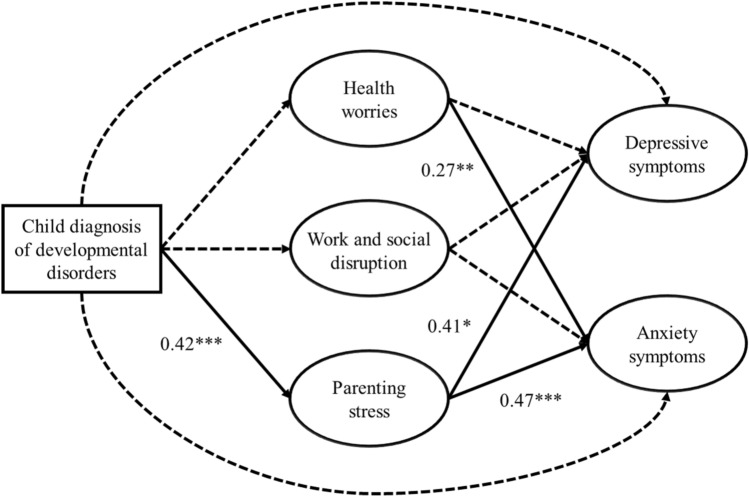

The results indicated that the measurement model provided an acceptable fit to the data, χ2 = 110.69 (df = 90, p = .07), CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.04, SRMR = 0.05. All loadings of the items or scales on their latent constructs (β = 0.45 to 0.93) were statistically significant (ps < .05). The structural model also showed an acceptable model fit: χ2 = 199.36 (df = 153, p < .001), CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.08. Table 2 presents the unstandardized and standardized path coefficients for the hypothesized model. Compared with parents of children with typical development, parents of children with developmental disorders showed higher levels of parenting stress (β = 0.42, p < .001). Child diagnosis of developmental disorders was not significantly related to health worries (β = − 0.19, p = .06) and work and social disruption (β = 0.41, p = .13). Parenting stress was related to higher levels of depressive symptoms (β = 0.19, p = .03) and anxiety symptoms (β = 0.47, p = .002). Health worries were positively related to anxiety symptoms (β = 0.27, p = .007) but not depressive symptoms (β = 0.06, p = .64). Work and social disruption were not significantly related to depressive symptoms (β = − 0.04, p = .83) and anxiety symptoms (β = − 0.18, p = .31) (see Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Unstandardized and standardized path coefficients for the hypothesized model

| Unstandardized | Standardized | |

|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | β | |

| Direct effect | ||

| Child diagnosis of developmental disorders → health worries | − 0.30 (0.16) | − 0.19 |

| Child diagnosis of developmental disorders → work and social disruption | 0.26 (0.17) | 0.17 |

| Child diagnosis of developmental disorders → parenting stress | 0.86 (0.19)*** | 0.42*** |

| Child diagnosis of developmental disorders → depressive symptoms | 0.15 (0.12) | 0.16 |

| Child diagnosis of developmental disorders → anxiety symptoms | 0.19 (0.13) | 0.16 |

| Health worries → depressive symptoms | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.06 |

| Health worries → anxiety symptoms | 0.20 (0.07)** | 0.27** |

| Work and social disruption → depressive symptoms | − 0.03 (0.12) | − 0.04 |

| Work and social disruption → anxiety symptoms | − 0.14 (0.13) | − 0.18 |

| Parenting stress → depressive symptoms | 0.19 (0.08)* | 0.41* |

| Parenting stress → anxiety symptoms | 0.28 (0.09)** | 0.47** |

| Depressive symptoms ↔ anxiety symptoms | 0.14 (0.03)*** | 0.87*** |

| Standardized | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Indirect effect | ||

| Child diagnosis of developmental disorders → health worries → depressive symptoms | − 0.01 | − 0.06, 0.04 |

| Child diagnosis of developmental disorders → work and social disruption → depressive symptoms | − 0.01 | − 0.08, 0.07 |

| Child diagnosis of developmental disorders → parenting stress → depressive symptoms | 0.17* | 0.02, 0.33 |

| Child diagnosis of developmental disorders → health worries → anxiety symptoms | − 0.05 | − 0.11, 0.01 |

| Child diagnosis of developmental disorders → work and social disruption → anxiety symptoms | − 0.03 | − 0.10, 0.05 |

| Child diagnosis of developmental disorders → parenting stress → anxiety symptoms | 0.20** | 0.05, 0.34 |

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Fig. 2.

Standardized path coefficients of the hypothesized model. Solid lines represent significant paths, dashed lines represent non-significant paths; controlling for gender, age, education level, monthly household income level, and number of children; *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Indirect effects of having a child with developmental disorders (as compared to having a child with typical development) on mental health were examined using bootstrapping analysis. The results indicated that the effects of having a child with developmental disorders on depressive symptoms were significantly mediated by parenting stress (β = 0.16, 95% CI 0.05, 0.34). A significant indirect effect of having a child with developmental disorders on anxiety symptoms via parenting stress was also observed (β = 0.24, 95% CI 0.10, 0.47). The results of mediation analyses revealed that parenting stress during the COVID-19 pandemic explained the differences in mental health status between parents of children with developmental disorders and those of children with typical development (see Table 2).

Discussion

The present study investigated the stress and mental health problems of parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Three dimensions of COVID-19-related stress in particular were examined: health worries, work and social disruption, and parenting stress. The findings showed that more than half of the parents experienced health-related concerns, worrying that they and their children might be infected with COVID-19 (Ersoy et al., 2020; Spinelli et al., 2020). With the introduction of population-wide social distancing measures in Hong Kong (e.g., work-from-home arrangements, restrictions on outdoor gatherings, closure of non-essential public services), close to three-fourths of them indicated that their work and social lives were significantly disrupted. Given the closure of schools during the pandemic, children were expected to stay at home, which has increased the caregiving burden among their parents (Spinelli et al., 2020). As revealed in the present study, nearly two-thirds of the parents reported significant difficulty in taking care of their child and experienced strain in balancing the demands of childcare and other work responsibilities.

To our knowledge, this is among the first published studies to investigate how parents of children with developmental disorders were affected by the COVID-19 outbreak (Lee et al., 2020; Pavlopoulou et al., 2020). Consistent with previous studies (Chan et al., 2020), our results clearly show that parents of children with developmental disorders were at greater risk of parenting stress, as compared to parents of children with typical development. The differences might be even more obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic. As their primary caregivers, parents may find it difficult to manage their children’s problem behavior and face increased pressures regarding meeting the needs of children because of the absence of school support during the COVID-19 pandemic (Stankovic et al., 2020).

In addition, parents of children with developmental disorders showed more severe levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms than do their counterparts. One-fourth of parents of children with developmental disorders (25.5%) met the criteria for clinical depression, and 13.7% met the criteria for generalized anxiety disorder. The prevalence of depression and anxiety was even higher than that observed among the general population in China during the peak of its COVID-19 pandemic (depression: 18.2%; anxiety: 8.8%) (Ran et al., 2020). Not only did the parents suffer from significantly higher levels of psychological distress due to the COVID-19 outbreak, having a child with developmental disorders also placed them at elevated risk of mental health problems. In line with the FAAR model, the findings showed that parenting stress arising from the pandemic significantly contributed to depressive and anxiety symptoms among parents, whereas health worries were positively predictive of their anxiety symptoms. Parents who were worried that they and their family members might be infected with COVID-19 were more vigilant to being exposed to potentially infectious environments, which could explain their heightened levels of anxiety symptoms (Ersoy et al., 2020).

Most importantly, the results showed that parenting stress mediated the effect of child diagnosis of developmental disorders on depressive and anxiety symptoms among parents. Compared with parents of children with typical development, parents of children with developmental disorders experienced greater levels of parenting stress due to the COVID-19 pandemic. During this critical period, parents assumed the primary responsibility for managing their child’s condition and needs, resulting in burnout and fatigue (Lee et al., 2020; Pavlopoulou et al., 2020). It was found that parenting stress was related to higher levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms. The findings clearly indicated that careful clinical attention should be paid to the mental health of parents, especially those who have children with developmental disorders.

Practical Implications

Given the elevated risk of parenting stress and mental health problems observed among parents of children with developmental disorders, timely positive parenting support is necessary to reinforce parent–child relationships and alleviate parents’ psychological distress. Parenting programs—for example the Positive Parenting Program (Wiggins et al., 2009) and the Parent–Child Interaction Therapy (Eyberg, 1988)—were shown as evidence-based interventions for enhancing parenting competence and efficacy. With the current implementation of social distancing practices, web-based parenting skills programs can be offered to parents who are in need of professional support and guidance during the COVID-19 pandemic (James Riegler et al., 2020). For those who are emotionally disturbed by their relationships with their children and/or family, online counseling and support group services should be made available to facilitate their coping with health worries and parenting stress.

Due to the additional parenting stress brought by the COVID-19 pandemic, family-friendly policy initiatives are needed to reconcile work and family responsibilities for working parents (Jang, 2009). Workplace policies such as flexible work schedules and work-from-home arrangements can be considered to minimize the impact of the pandemic on employees. On the one hand, this kind of workplace policy complies with the requirement of social distancing, which reduces the risk of transmission of COVID-19. On the other hand, family-friendly policies can help parents have a more balanced life during the pandemic, which may improve not only their parenting and mental health, but also their morale and commitment to the organizations in the long run (Grover & Crooker, 1995).

Limitations

Despite the timeliness and relevance of the present study, a few limitations should be noted when considering the findings. First, this study focused on a group of parents whose children were in late childhood (aged 8–10) to ensure that the respondents shared similar caregiving and parenting expectations. Future studies should examine whether the proposed model applies to parents of children at other developmental stages because they might be differentially affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the data prevents causal inferences from being drawn. Longitudinal research is needed to determine the directionality of the association between COVID-19 stress and mental health among parents. Third, there may have been a possibility of selection bias, as parents who were more concerned about and/or severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic were more likely to respond to the survey. This may limit the generalizability of the results. Fourth, the present study focused only on experience of COVID-19-related stress and psychological distress among parents. To develop a more thorough understanding of family adjustment to the COVID-19 pandemic, future work should consider examining access to formal and informal support networks, coping behavior, and meaning-making processes. Fifth, this study included a newly developed measure to assess COVID-19-related stress due to the lack of validated scales. Although our measure demonstrated good construct validity of three dimensions of COVID-19-related stress (i.e., health worries, work and social disruption, and parenting stress), further validation work is needed to establish the convergent and discriminant validity of the measure.

Conclusions

This study provides a timely and important investigation into the stress and mental health difficulties of parents during the COVID-19 crisis. The findings illustrated how the parents, particularly those who had children with developmental disorders, were affected by the pandemic. It was clearly evident that health worries and parenting stress were two significant COVID-19 stressors contributing to poor mental health among parents in Hong Kong. Compared with parents of children with typical development, parents of children with developmental disorders were at increased risk of parenting stress, which was associated with heightened levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms. To mitigate their stress and mental health problems, it is essential to implement parenting skills interventions, online psychological support services, and family-friendly policy initiatives during this critical period of time.

Author’s Contribution

Randolph C. H. Chan was primarily responsible for study conceptualization and design, data collection, statistical analysis, and the writing of the manuscript. Suk Chun Fung was responsible for study design, data collection, and the review of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the Focused Knowledge Transfer Grant, Faculty of Education and Human Development, The Education University of Hong Kong (Ref. No.: #02145).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aishworiya R, Kang YQ. Including children with developmental disabilities in the equation during this COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04670-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asbury K, Fox L, Deniz E, Code A, Toseeb U. How is COVID-19 affecting the mental health of children with special educational needs and disabilities and their families? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04577-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmundson GJG, Taylor S. How health anxiety influences responses to viral outbreaks like COVID-19: What all decision-makers, health authorities, and health care professionals need to know. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2020;71:102211. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bent, S., Hossain, B., Chen, Y., Widjaja, F., Breard, M., & Hendren, R. (2020). The experience of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative analysis. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-46426/v1

- Chan RCH, Yi H, Siu QKY. Polymorbidity of developmental disabilities: Additive effects on child psychosocial functioning and parental distress. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2020;99:103579. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung G, Lanier P, Ju PWY. Mediating effects of parental stress on harsh parenting and parent-child relationship during coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Singapore. Open Science Framework; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colizzi M, Sironi E, Antonini F, Ciceri ML, Bovo C, Zoccante L. Psychosocial and behavioral impact of COVID-19 in Autism spectrum disorder: An online parent survey. Brain Sciences. 2020;10(6):341. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10060341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtemanche C, Garuccio J, Le A, Pinkston J, Yelowitz A. Strong social distancing measures in the United States reduced the COVID-19 growth rate: Study evaluates the impact of social distancing measures on the growth rate of confirmed COVID-19 cases across the United States. Health Affairs. 2020;39(7):1237–1246. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersoy K, Altin B, Sarikaya B, Ozkardas O. The comparison of impact of health anxiety on dispositional hope and psychological well-being of mothers who have children diagnosed with autism and mothers who have normal children, in Covid-19 Pandemic. Social Sciences Research Journal. 2020;9(2):117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg S. Parent–child interaction therapy: Integration of traditional and behavioral concerns. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 1988;10(1):33–46. doi: 10.1300/J019v10n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2020;180(6):817–818. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover SL, Crooker KJ. Who appreciates family-responsive human resource policies: The impact of family-friendly policies on the organizational attachment of parents and non-parents. Personnel Psychology. 1995;48(2):271–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1995.tb01757.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SA, Watson SL. The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(3):629–642. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1604-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He XY, Li C, Qian J, Cui HS, Wu W. Reliability and validity of a generalized anxiety disorder scale in general hospital outpatients. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry. 2010;22(4):200–203. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research. 2020;288:112954. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James Riegler L, Raj SP, Moscato EL, Narad ME, Kincaid A, Wade SL. Pilot trial of a telepsychotherapy parenting skills intervention for veteran families: Implications for managing parenting stress during COVID-19. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. 2020;30(2):290–303. doi: 10.1037/int0000220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SJ. The relationships of flexible work schedules, workplace support, supervisory support, work-life balance, and the well-being of working parents. Journal of Social Service Research. 2009;35(2):93–104. doi: 10.1080/01488370802678561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee V, Albaum C, Tablon Modica P, Ahmad F, Gorter JW, Khanlou N, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health and wellbeing of caregivers and families of autistic people: A rapid synthesis review. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2020. p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Liu CH, Zhang E, Wong GTF, Hyun S, Hahm H. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Research. 2020;290:113172. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi A, Mendoza Diaz A, Tully L, Azim SI, Woolfenden S, Efron D, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the well-being of children with neurodevelopmental disabilities and their parents. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jpc.15285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutluer T, Doenyas C, Genc HA. Behavioral implications of the COVID-19 process for autism spectrum disorder, and individuals' comprehension of and reactions to the pandemic conditions. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11:561882. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.561882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. International Journal of Surgery. 2020;78:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palgi Y, Shrira A, Ring L, Bodner E, Avidor S, Bergman Y, et al. The loneliness pandemic: Loneliness and other concomitants of depression, anxiety and their comorbidity during the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;275:109–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JM. Families experiencing stress: I. The family adjustment and adaptation response model: II. Applying the FAAR model to health-related issues for intervention and research. Family Systems Medicine. 1988;6(2):202–237. doi: 10.1037/h0089739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JM. Integrating family resilience and family stress theory. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64(2):349–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00349.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JM, Garwick AW. The impact of chronic illness on families: A family systems perspective. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;16(2):131–142. doi: 10.1093/abm/16.2.131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlopoulou G, Wood R, Papadopoulos C. Impact of Covid-19 on the experiences of parents and family carers of autistic children and young people in the UK. UCL Institute of Education; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383(6):510–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran L, Wang W, Ai M, Kong Y, Chen J, Kuang L. Psychological resilience, depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms in response to COVID-19: A study of the general population in China at the peak of its epidemic. Social Science & Medicine. 2020;262:113261. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AR. Crisis intervention handbook: Assessment, treatment, and research. Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Serlachius A, Badawy SM, Thabrew H. Psychosocial challenges and opportunities for youth with chronic health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting. 2020;3(2):e23057. doi: 10.2196/23057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu QKY, Yi H, Chan RCH, Chio FHN, Chan DFY, Mak WWS. The role of child problem behaviors in autism spectrum symptoms and parenting stress: A primary school-based study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2019;49(3):857–870. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3791-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli M, Lionetti F, Pastore M, Fasolo M. Parents’ stress and children’s psychological problems in families facing the covid-19 outbreak in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11:1713. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankovic M, Jelena S, Stankovic M, Shih A, Stojanovic A, Stankovic S. The Serbian experience of challenges of parenting children with autism spectrum disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and the state of emergency with the police lockdown. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3582788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suen Y, Chan RCH, Wong EMY. Effects of general and sexual minority-specific COVID-19-related stressors on the mental health of lesbian, gay and bisexual people in Hong Kong. Psychiatry Research. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinson RP. The GAD-7 scale was accurate for diagnosing generalised anxiety disorder. Evidence-Based Medicine. 2006;11(6):184. doi: 10.1136/ebm.11.6.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Landry CA, Paluszek MM, Asmundson GJG. Reactions to COVID-19: Differential predictors of distress, avoidance, and disregard for social distancing. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;277:94–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Bian Q, Zhao Y, Li X, Wang W, Du J, et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2014;36(5):539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston R, Gore PA. A brief guide to structural equation modeling. The Counseling Psychologist. 2006;34(5):719–751. doi: 10.1177/0011000006286345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins TL, Sofronoff K, Sanders MR. Pathways triple P-positive parenting program: Effects on parent-child relationships and child behavior problems. Family Process. 2009;48(4):517–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Meeting report: Autism spectrum disorders and other developmental disorders: From raising awareness to building capacity: World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland 16–18 September 2013. World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wright L, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. How are adversities during COVID-19 affecting mental health? Differential associations for worries and experiences and implications for policy. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.14.20101717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yorke I, White P, Weston A, Rafla M, Charman T, Simonoff E. The association between emotional and behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorder and psychological distress in their parents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2018;48(10):3416–3416. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3656-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]