CRISPR screening identifies RNA m6A modification as negative regulator of TLR signaling pathway for proper innate immune response.

Abstract

m6A RNA modification is implicated in multiple cellular responses. However, its function in the innate immune cells is poorly understood. Here, we identified major m6A “writers” as the top candidate genes regulating macrophage activation by LPS in an RNA binding protein focused CRISPR screening. We have confirmed that Mettl3-deficient macrophages exhibited reduced TNF-α production upon LPS stimulation in vitro. Consistently, Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice displayed increased susceptibility to bacterial infection and showed faster tumor growth. Mechanistically, the transcripts of the Irakm gene encoding a negative regulator of TLR4 signaling were highly decorated by m6A modification. METTL3 deficiency led to the loss of m6A modification on Irakm mRNA and slowed down its degradation, resulting in a higher level of IRAKM, which ultimately suppressed TLR signaling–mediated macrophage activation. Our findings demonstrate a previously unknown role for METTL3-mediated m6A modification in innate immune responses and implicate the m6A machinery as a potential cancer immunotherapy target.

INTRODUCTION

Macrophages, serving as the first line of host defense, recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) of invading pathogens and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) from stressed or injured cells. These processes involve pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (1). Depending on their genetic background and environmental stimuli, macrophages can be polarized to either an M1-like proinflammatory or tumoricidal phenotype with high capacity for antigen presentation and T cell activation or to an M2-like anti-inflammatory or protumoral phenotype with immunosuppressive function (2–4). Activated macrophages produce large numbers of chemokines and proinflammatory cytokines that attract and activate T cells to eliminate the invading pathogens. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) within the tumor microenvironment represent a functional heterogeneous cell population that has a critical role in orchestrating tumor initiation and progression (3, 5, 6). Macrophage-centered strategies, including macrophage-targeting and TAM tumor-promoting blockade, began to enter clinical trials and show great potential for macrophage-based immunotherapy (3, 6, 7). Therefore, understanding the signaling involved in the activation and plasticity of TAMs will help develop better strategies for cancer immunotherapy.

The discovery of the components of the TLR signaling pathways has significantly advanced our knowledge of innate immune responses, which represent one of the most important evolutionarily conserved innate mechanisms for sensing invading pathogens. One of the most studied TLRs, TLR4, stimulates the myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (MyD88)- and TIR domain-containing adapter protein-inducing interferon β (TRIF)–dependent pathways, activating the transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and consequently inducing type I interferons and inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (8, 9). It has been demonstrated that negative regulation of the TLR signaling is strongly associated with the pathogenesis of inflammation and autoimmune diseases (10–13). We and others have shown that IL-1 receptor–associated kinase 3 (IRAK3), also known as IRAKM, is an essential negative regulator of TLR signaling pathways (14–17). The expression of IRAKM induced by the activation of macrophages prevents the dissociation of IRAK and IRAK4 from MyD88 and inhibits the formation of IRAK-TRAF6 (TNF receptor–associated factor 6) complexes. These effects of IRAKM suppress NF-κB activation and the expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in macrophages, preventing the development of pathologic immune reactions (10, 14). However, it remains unknown whether the posttranscriptional regulation, particularly the epigenetic modification of RNA, is involved in the control of innate immune responses in macrophages.

RNA modifications, especially the formation of N6-methyladenosine (m6A), represent one of the most delicate posttranscriptional mechanisms regulating gene expression (18). m6A, the most abundant mRNA modification, is modulated by m6A “writer,” “eraser,” and “reader.” The m6A writer complex comprises the catalytic core consisting of methyltransferase like 3 (METTL3) and methyltransferase like 14 (METTL14) and the adapter proteins Wilms tumor 1 associated protein (WTAP), RNA binding motif protein 15 (RBM15), vir like m6A methyltransferase associated (VIRMA), zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13 (ZC3H13), and Cbl proto-oncogene like 1 (CBLL1) (19, 20). It has been extensively documented that m6A is involved in pre-mRNA splicing, mRNA export, initiation, translation, and, predominantly, mRNA degradation (21, 22). m6A methylation has been regarded as a key regulator in various biological and pathological processes (19, 21), but its function in the immune system has not been recognized until recently (23). Our previous studies demonstrated that silencing the m6A methyltransferase METTL3 disrupts T cell homeostasis by targeting the IL-7/signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5)/suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) pathway and causes a systemic loss of the suppressive function of regulatory T cells (Tregs) (24, 25). The METTL3-mediated m6A modification on Cd40, Cd80, and TIR domain containing adaptor protein (Tirap) transcripts enhances their translation in dendritic cells, promoting dendritic cell activation (26). Together, these studies indicate that m6A methylation plays an essential role in the maintenance of immune cell homeostasis and function. In addition, the deletion of m6A demethylase alkB homolog 5, RNA demethylase (ALKBH5) in macrophages has been recently demonstrated to inhibit viral replication in vivo and in vitro (27, 28). The m6A reader YTH N6-methyladenosine RNA binding protein 3 (YTHDF3) suppresses interferon-dependent antiviral responses by promoting forkhead box O3 (FOXO3) translation (29). In addition, the loss of YTHDF1 in classical dendritic cells enhances the cross-presentation of tumor antigen and the cross-priming of CD8+ T cells in vivo (30). These findings, which highlight the significance of m6A modification in the immune response, prompted us to explore further the function of METTL3-mediated m6A modification in macrophage activation and polarization and the role of TAMs during tumorigenesis.

Here, we have identified METTL3 as a positive regulator of the innate response of macrophages by pooled RNA binding protein (RBP) CRISPR-Cas9 screening. We have demonstrated that Mettl3 deficiency in macrophages attenuates their ability to fight against pathogens and eliminate tumors in vivo, suggesting that METTL3-mediated m6A modification is required for proper activation of macrophages. We have shown that Mettl3 deficiency impairs the TLR4 signaling pathway in macrophages by inhibiting the degradation of Irakm transcripts. Thus, the present work uncovers the epitranscriptional control of the innate immune response of macrophages, providing a novel strategy to target the m6A machinery for macrophage-based cancer immunotherapy.

RESULTS

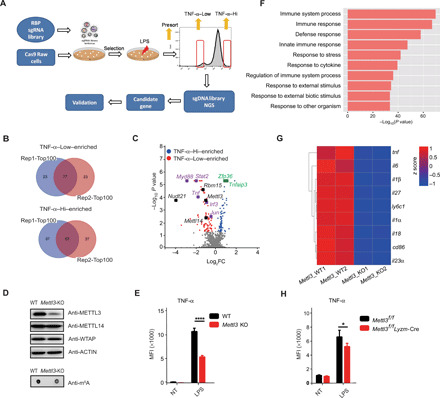

Pooled CRISPR-Cas9 screen identified m6A modification that promotes macrophage activation by lipopolysaccharide treatment

The posttranscriptional regulation of TLR signaling and proinflammatory cytokines is fine-controlled during macrophage activation. However, these processes have not been adequately studied. Therefore, we have investigated the posttranscriptional events in mRNA metabolism that are tightly regulated by RBPs to orchestrate fundamental cellular processes. To screen RBPs critical for macrophage activation, we prepared customized pooled RBP CRISPR-Cas9 screens. TNF-α was selected as the readout for the targeted RBP CRISPR screening since this cytokine represents the primary response during macrophage activation and can be easily detected by flow cytometry. Moreover, TNF-α has also been shown to act as a “master regulator” of inflammatory cytokine synthesis, and its aberrant production is associated with the pathogenesis of several inflammatory diseases (31, 32). We have compiled and synthesized a targeted lentivirus mini-library with 7272 single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting 782 genes coding for classical RBPs known in the mouse genome, as well as positive and negative controls with 10 gRNAs for each gene (listed in the Supplementary Materials). We have also generated a Raw 264.7 macrophage cell line stably expressing Cas9 and validated its functionality and effectiveness (fig. S1A). In each of the two replicate screens, 109 Cas9-expressing Raw 264.7 cells were infected with a lentivirus library at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.3. After selection with puromycin for 7 days, cells were stimulated with LPS and sorted on the basis of TNF-α expression (Fig. 1A and fig. S1B). sgRNAs from cells with high (TNF-α–Hi) and low (TNF-α–Low) TNF-α expression and from cells harvested on the last day of selection before sorting (presort) were amplified and sequenced. The top-ranked sgRNA enriched in TNF-α–Hi or TNF-α–Low cells showed high concordance between biological screen replicates (Fig. 1B). As expected, sgRNAs targeting known positive regulators (e.g., Myd88 and Irf3) and negative regulators (e.g., Zfp36 and Tnfaip3) of the LPS response were enriched in TNF-α–Low and TNF-α–Hi cells, respectively, demonstrating the success and high quality of the screens (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1. CRISPR screening identifies METTL3 as a regulator of TNF-α production in macrophages.

(A) Scheme of pooled CRISPR-Cas9 screening of RBPs playing critical roles in macrophage activation. Briefly, Cas9-expressing Raw 264.7 cells were infected with lentivirus library containing sgRNAs targeting RBP genes in the mouse genome. After selection with puromycin for 7 days, the cells were stimulated with LPS and sorted by flow cytometry on the basis of the expression levels of TNF-α. (B) Venn diagrams showing the overlap between the top 100 ranked candidate genes enriched in TNF-α–Low and TNF-α–Hi populations in two replicate screens. (C) Volcano plot showing sgRNA-targeted genes enriched in the TNF-α–Hi (blue) and TNF-α–Low (red) populations. Known positive regulators (purple), negative regulators (green), and m6A modulators (black) of TNF-α production in macrophages are highlighted. (D) Protein level of METTL3 and the overall RNA m6A methylation levels in WT and Mettl3-KO Raw 264.7 cells were measured by Western blotting and m6A dot blot assay. (E) Expression of TNF-α in METTL3-depleted and control Raw 264.7 cells after LPS stimulation measured by flow cytometry. MFI, median fluorescence intensity; NT, not treated. (F) GO enrichment analysis of down-regulated transcripts in Mettl3-KO Raw 264.7 cells compared to WT control cells. (G) Heatmap illustrating the expression of transcripts downstream of the TLR4 signaling pathway in Mettl3-deficient and WT Raw 264.7 cells. (H) Expression of TNF-α in bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre and Mettl3flox/flox control mice upon LPS stimulation measured by flow cytometry. Data are shown from two experiments (B and C), as a representative result of three independent experiments (D), or as means ± SEM (E and H).*P < 0.05 and ****P < 0.0001 (unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test).

Besides the known regulators, we have also found that sgRNAs targeting the components of the m6A writer complex—Mettl3, Mettl14, Rbm15, and Nudt21—were highly enriched in the top-ranked hits in TNF-α–Low cells. These results indicate important functions and a general role of m6A modification in the activation of macrophages (Fig. 1C). To validate the involvement of m6A in macrophage activation, Mettl3 was knocked out in Raw 264.7 cells using CRISPR with new sgRNAs, and the deficiency of Mettl3 and the substantial decrease in the overall RNA m6A methylation level were confirmed (Fig. 1D). Consistent with the CRISPR screen results, the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in Mettl3-depleted Raw 264.7 cells stimulated with LPS was markedly reduced in comparison to control cells (Fig. 1E and fig. S1, C to H). To further explore the biological effects of m6A deficiency on macrophages, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis on Mettl3 knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) control Raw 264.7 cells. The Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis documented that the down-regulated transcripts in Mettl3-KO Raw 264.7 cells were enriched in innate immune response related to defense and external stimulus (Fig. 1F). Notably, in both replicates of RNA-seq, transcripts of the downstream components of the TLR4 signaling pathway, such as proinflammatory cytokines (Tnf-α, Il-6, Il-1β, Il-18, and Il-23) and costimulation molecules (Cd86), were down-regulated in Mettl3-deficient cells (Fig. 1G), suggesting that METTL3 has a critical function in controlling the innate immune response of Raw 264.7 macrophages.

To further confirm the biological role of the m6A modification in macrophages, Mettl3 conditional KO (CKO) mice were generated by crossing Mettl3flox/flox mice with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of lysozyme 2 promoter (Lyzm-Cre). We have documented the loss of both the METTL3 protein and the overall m6A modification in bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice (fig. S1I). No differences in the frequency of major immune cell populations were observed between Mettl3flox/flox mice and Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice in steady state, indicating that the depletion of Mettl3 did not affect the development and maturation of macrophages (fig. S1J). Next, we examined whether METTL3 affects macrophage activation. Consistent with the results obtained in Raw 264.7 cells, BMDMs from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice showed significantly decreased expression of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-12, upon LPS stimulation (Fig. 1H and fig. S1K). Together, these results demonstrate that METTL3 promotes the activation of macrophages.

Notably, the m6A readers, including YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, YTHDC1, YTHDC2, IGF2BP1, IGF2BP2, IGF2BP3, HNRNPC, and HNRNPA2B1, did not reach significance in either TNF-α–Low or TNF-α–High population (fig. S2A and table S1), indicating that these genes either play a minimal role or have redundant functions in regulating the LPS-induced Tnf-α production. To further assess the functional role of m6A readers in macrophages, small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were used to knock down the expression of Ythdf2 and other readers, including Ythdf1, Ythdf3, and Ythdc1 in bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) (fig. S2B). As shown in fig. S2C, we found that knocking down Ythdf2, Ythdf3, or Ythdc1 individually had a minor impact on Tnf-α expression upon LPS stimulation, whereas knocking down Ythdf1 decreased the expression of Tnf-α, and markedly higher down-regulation of Tnf-α was seen when knocking down the expression of Ythdf1, Ythdf2, and Ythdf3 simultaneously. These results suggested the functional redundancy of YTHDF proteins in the innate immune response of macrophages (33, 34). In addition to the involvement of m6A modification in the activation of macrophages by LPS, other pathways associated with the mRNA metabolic process have also been found by GO and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses of the top 100 ranked hits in TNF-α–Hi and TNF-α–Low cells (fig. S2, D to G), which merits further exploration.

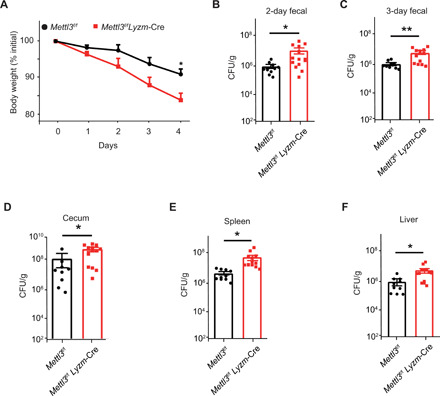

Mettl3-deficient mice are more susceptible to Salmonella typhimurium infection

Upon recognizing invading pathogens, macrophages are activated to produce proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, that enhance the defense response of the host, facilitating pathogen clearance. To test the screen results in vivo, we investigated the physiological role of m6A modification in the macrophage-mediated defense against LPS-producing Gram-negative bacteria. For this purpose, Mettl3flox/flox; Lyzm-Cre mice and Mettl3flox/flox littermates were infected orally with S. typhimurium and sacrificed 4 days after infection to assess the inflammation and bacterial load in the intestine and other organs. Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice showed significantly lower body weight than Mettl3flox/flox littermates (Fig. 2A) and had a higher bacterial load in the feces and cecum (Fig. 2, B to D). Furthermore, Mettl3flox/flox; Lyzm-Cre mice had a higher bacterial burden in the spleen and liver than Mettl3flox/flox littermates (Fig. 2, E and F). Together, these data suggest that METTL3 promotes the antibacterial activity of macrophages in vivo.

Fig. 2. Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice are more susceptible to S. typhimurium infection.

(A) Body weight of Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre (n = 14) and their Mettl3flox/flox littermates (n = 10) measured 2 and 3 days after S. typhimurium infection. (B to F) Bacteria load of the feces (B and C), cecum (D), spleen (E), and liver (F) of infected Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre (n = 14) and Mettl3flox/flox littermates (n = 10) measured by counting colony-forming units (CFU) in cultures of serially diluted homogenates of organs on MacConkey agar plates. Data are shown as representative results of three independent experiments (A to F) or as means ± SD of indicated determinants (B to F). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test).

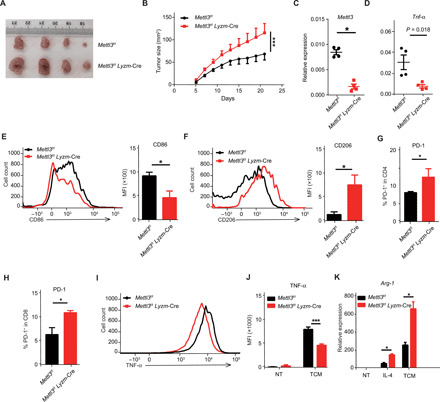

Loss of METTL3 in macrophages promotes tumor growth in vivo

Given the function of m6A in promoting macrophage activation, we next sought to determine the role of METTL3 in macrophage-mediated antitumor immunity. Therefore, MC38 murine colon adenocarcinoma cells were subcutaneously implanted into the flanks of Mettl3flox/flox; Lyzm-Cre mice and their Mettl3flox/flox littermates. The growth of tumors was significantly faster in Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice (Fig. 3, A and B, and fig. S3A). The mice were sacrificed 3 weeks after injection, and tumor-infiltrating immune cells were characterized by flow cytometry and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). There was no significant difference in the percentage of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes between Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice and Mettl3flox/flox littermates (fig. S3B). Notably, TAMs from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice exhibited reduced M1-like markers, such as the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α and the costimulatory protein CD86 (Fig. 3, C to E, and fig. S3C), while the expression of the mannose receptor CD206, a well-established M2-like marker, was increased in comparison with TAMs from Mettl3flox/flox mice (Fig. 3F and fig. S3C). These differences indicate that Mettl3 deficiency promotes the immunosuppressive function of TAMs. In addition, the expression of major histocompatibility complex II (MHC II) was comparable in TAMs from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice and Mettl3flox/flox littermates (fig. S3C). Consistent with these observations, both tumor-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice displayed a more exhausted phenotype, as evidenced by the elevated expression of the immune checkpoint receptor programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) (Fig. 3, G and H, and fig. S3D). Furthermore, in comparison with Mettl3flox/flox mice, BMDMs from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice were characterized by blunted TNF-α production after the stimulation with MC38 tumor culture medium (TCM) (Fig. 3, I and J) and increased formation of the M2-like marker Arg-1 after either TCM or IL-4 stimulation (Fig. 3K and fig. S3E). Collectively, these data demonstrate that METTL3 promotes the tumoricidal ability of macrophages by facilitating the polarization bias of TAMs toward the M1 type macrophages.

Fig. 3. Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice exhibit faster tumor growth and a lower level of macrophage-derived TNF-α than WT littermates.

MC38 cells were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice and their Mettl3flox/flox littermates. The tumor was excised, and tumor-infiltrating cells were characterized by flow cytometry and real-time qPCR. (A) Representative images of tumors excised from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice (n = 10) and Mettl3flox/flox littermates (n = 10) 21 days after cell injection. Photo credit: Jiyu Tong, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. (B) Tumor growth in Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice (n = 10) and Mettl3flox/flox littermates (n = 10). (C and D) Relative expression of Mettl3 (C) and Tnf-α (D) in TAMs from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice (n = 4) and Mettl3flox/flox littermates (n = 4) measured by real-time qPCR. (E and F) Flow cytometry profile and MFI of CD86-positive (E) and CD206-positive (F) TAMs from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice (n = 4) and Mettl3flox/flox littermates (n = 4). (G and H) Fractions of intratumoral PD-1–positive CD4+ T cells (G) and PD-1–positive CD8+ T cells (H) measured by flow cytometry (n = 3). (I and J) BMDMs from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice and Mettl3flox/flox littermates were stimulated with medium conditioned by MC38 tumor cells in vitro. The expression of TNF-α was measured by flow cytometry and shown as a histogram (I) and MFI (J). Arg-1 expression in TAMs from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice and Mettl3flox/flox littermates measured by real-time qPCR after TCM or IL-4 treatment. Data are shown as representative results of three independent experiments (A, E, F, and I), as means ± SD (B, G, and H), or as means ± SEM (C to F, J, and K). *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 (unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test).

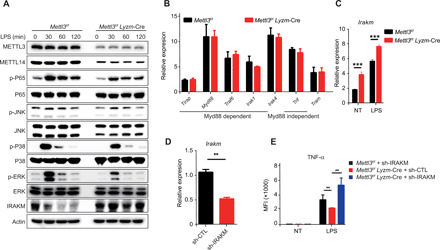

METTL3 deficiency inhibits macrophage activation by inducing a negative regulator of the TLR signaling pathway

To distinguish whether macrophage activation was impeded by the disruption of m6A modification rather than an m6A-independent activity of METTL3, we performed rescue experiments by overexpressing WT METTL3 (METTL3-WT) or catalytic mutant METTL3 (METTL3-MUT) in BMDMs from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice and Mettl3flox/flox littermate controls. The expression of TNF-α in BMDMs from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre animals could only be restored by the Mettl3-WT, but not Mettl3-MUT constructs (fig. S4A). Since Tnf-α mRNA can also be m6A-modified according to the m6AVar database, we hypothesized that Tnf-α might be directly regulated by m6A. First, the degradation rate of Tnf-α mRNAs was measured using RNA decay assays. Both Mettl3-depleted and WT Raw 264.7 cells were treated with the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D, and the changes in the abundance of Tnf-α transcripts over time were measured by qPCR. The degradation of Tnf-α mRNAs was similar in Mettl3-depleted Raw 264.7 cells and WT control cells (fig. S4B). Next, a mutagenesis assay was performed to directly assess the effect of m6A modification on TNF-α expression. The assay used a WT Tnf-α construct in which WT Tnf-α 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) and WT Tnf-α 3′UTR were replaced with either Tnf-α 5′UTR-MUT or Tnf-α 3′UTR-MUT harboring a point mutation in m6A sites predicted according to the m6AVar database (fig. S4C). The coding region of Tnf-α was substituted with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) coding region to allow direct measurement of TNF-α expression. A similar level of GFP expression was observed when human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were transfected with the same amount of each construct (fig. S4D). Therefore, these experiments demonstrated that although macrophage activation was indeed regulated by the m6A catalytic activity of METTL3, Tnf-α mRNA was not the direct target of the m6A modification.

It is well established that the engagement of PAMPs or DAMPs with TLR4 receptors activates MyD88- and TRIF-dependent pathways and ultimately induces the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines required for pathogen clearance or the destruction of tumor cells (6, 35). Since a defective expression of a broad range of cytokines was observed (Fig. 1G and fig. S1K), we hypothesized that the TLR4 receptor and its downstream pathway were compromised in Mettl3-deficient macrophages and could represent the direct m6A targets. Upon LPS stimulation, the phosphorylation of p65, p38, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK) in Mettl3-deficient BMDMs was markedly decreased, but the total levels of these proteins were comparable between BMDMs from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice and their Mettl3flox/flox littermates (Fig. 4A). These data indicate that the Mettl3 deficiency probably affects molecules upstream of the NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPKs) pathways. Therefore, we examined the expression levels of essential upstream adaptors in the TLR4 pathway, including Tirap, Myd88, Traf6, Irak1, Irak4, Trif, and Tram, using real-time qPCR. The expression of these key adaptors was similar in WT and Mettl3-deficient BMDMs (Fig. 4B). However, we have noted that the mRNA and protein levels of Irakm, a well-established negative regulator of the TLR signaling pathway, were remarkably increased in Mettl3-deficient BMDMs in either steady-state or upon LPS stimulation (Fig. 4, A and C). The expression of IRAKM in WT macrophages was reduced immediately after LPS stimulation and began to recover 2 hours after TLR4 activation. This phenomenon was strongly inhibited in Mettl3-KO macrophages, resulting in a sustained overexpression of IRAKM (Fig. 4A and fig. S4E). Thus, we have raised the possibility that the overexpression of IRAKM caused by Mettl3 deficiency is responsible for the inhibition of TLR4 activation. To test this hypothesis, rescue experiments were performed by introducing either Irakm small hairpin RNA (shRNAs) (sh-Irakm) or control shRNAs (sh-CTL) into Mettl3-deficient BMDMs (Fig. 4D). Consistent with our prediction, the decrease in TNF-α production in Mettl3-deficient BMDMs was largely reversed by the shRNA-mediated knockdown of Irakm (Fig. 4E). Together, these data indicate that the overexpression of Irakm in Mettl3-deficient macrophages suppresses the TLR4 signaling and consequently inhibits macrophage activation.

Fig. 4. METTL3 deficiency impairs the TLR4 signaling pathway by modulating IRAKM expression.

(A) Activation of the TLR4 signaling pathway in Mettl3-KO and Mettl3-WT BMDMs upon LPS stimulation was analyzed by Western blotting of p65, JNK, p38, ERK, and IRAKM. (B) Relative expression of Tirap, Myd88, Traf6, Irak, Irak4, Trif, and Tram in Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice and Mettl3flox/flox littermates measured by real-time qPCR. (C) Relative expression of Irakm in control (NT) and LPS-treated Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre and Mettl3flox/flox littermates measured by real-time qPCR. (D) Knockdown efficiency of shRNA targeting Irakm in BMDMs measured by real-time qPCR (n = 3). (E) TNF-α synthesis in WT BMDMs transfected with control shRNA (sh-CTL) and Mettl3-deficient BMDMs transfected with sh-CTL or IRAKM shRNA (sh-IRAKM) measured by flow cytometry (n = 3). Data are shown as representative results of three independent experiments (A) or as means ± SEM (B to E). **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 (unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test).

In addition, we tested other TLR pathways known to be regulated through IRAKM, especially TLR3 and TLR9. Similarly, TNF-α production of BMDMs from Mettl3flox/flox; Lyzm-Cre mice was significantly decreased upon poly (I:C) or CpG stimulation (fig. S5A and S5B). Thus, m6A regulates TLR-mediated macrophage activation through Irakm.

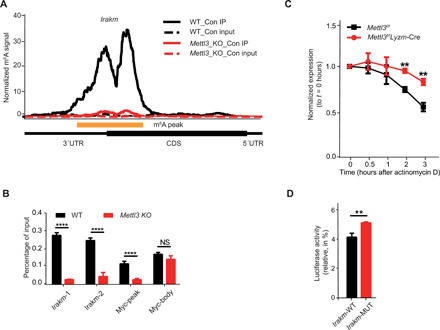

METTL3 installs m6A modifications on Irakm mRNA, promoting its degradation

RNA m6A methylation is involved in multiple aspects of RNA metabolism (36), predominantly affecting RNA stability. Mettl3 deficiency results in a significantly decreased m6A marker and, in turn, retards RNA decay of m6A target transcripts (37, 38). To assess whether the deletion of Mettl3 can decrease m6A methylation of Irakm mRNA, we profiled the transcriptome-wide m6A modification in WT and Mettl3-deficient Raw 264.7 cells using m6A immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing (MeRIP-seq). Specific m6A peaks were clearly enriched in the 3′UTR of Irakm mRNAs in WT cells, but the deletion of Mettl3 eliminated the Irakm m6A peaks completely (Fig. 5A). Notably, we did not detect significant m6A peak reduction in the Tnf-α transcript (fig. S6A) and did not observe any significant m6A peaks throughout Il-6 transcript (fig. S6B), indicating that Tnf-α and Il-6 are not direct m6A targets in macrophages. In agreement with the sequencing data, MeRIP-qPCR demonstrated that Irakm mRNA from WT but not Mettl3-deficient macrophages was immunoprecipitated by m6A-specific antibody (Fig. 5B). Together, these findings document that Irakm transcripts are bona fide m6A targets in macrophages.

Fig. 5. IRAKM expression is down-regulated by m6A modification.

(A) Specific m6A peaks enriched in the 3′UTR of Irakm mRNAs in Raw 264.7 macrophages profiled using MeRIP-seq. CDS, coding sequences. (B) m6A peaks enriched in the 3′UTR of Irakm mRNAs in WT cells were lost in Mettl3-KO Raw 264.7 cells. (C) WT or Mettl3-deficient BMDMs were treated with the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D, and the level of Irakm transcripts was measured over time. (D) Relative luciferase activity of pGL4-luc2 with WT-3′UTR (IRAKM-WT) or with IRAKM-3′UTR containing mutated m6A sites (IRAKM-MUT) transfected into HEK293T cells was measured. The firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. Data are shown as representative results of three independent experiments (A) or as means ± SEM (B to D). **P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant (unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test).

To further test whether the up-regulation of IRAKM resulted from the decreased degradation of m6A-deficient Irakm transcripts, we have performed RNA decay assays by treating either WT or Mettl3-deficient BMDMs and Raw 264.7 cells with actinomycin D and measured the abundance of Irakm transcripts over time (Fig. 5C and fig. S6C). At 3 hours after actinomycin D treatment, Irakm mRNA level was significantly higher in Mettl3-deficient BMDMs and Raw 264.7 cells than in the WT control cells (Fig. 5C and fig. S6C). To directly evaluate the role of m6A in modulating the stability of Irakm mRNA, luciferase reporter assays were conducted. In comparison with WT Irakm-3′UTR (Irakm-WT) constructs, the ectopically expressed constructs harboring m6A mutant Irakm-3′UTR (Irakm-MUT) showed substantially increased luciferase activity (Fig. 5D). We also constructed a plasmid harboring IRAKM with either WT-3′UTR or m6A–mut-3′UTR. Consistent with our previous results, we found that the transcription level of Irakm with m6A–mut-3′UTR was notably higher than that of Irakm with WT 3′UTR (fig. S6D). In addition, we also tested the effect of METTL3 deficiency on transcription of Irakm mRNA. As shown in the fig. S6E, we found that the transcription rate of Irakm mRNA only slightly increased upon Mettl3 KO. Therefore, the effect of METTL3 deficiency on Irakm expression was a combination of both transcription and decay but mainly due to decelerated degradation of Irakm mRNAs. Collectively, these data demonstrate that METTL3-mediated m6A modification promotes the TLR4 signaling mainly by accelerating the degradation of Irakm mRNAs.

A novel mechanism has recently been revealed by which m6A methylation facilitates the decay of the chromosome-associated regulatory RNAs (carRNAs), including promoter-associated RNAs (paRNAs), enhancer RNAs (eRNAs), and repeat RNAs, affecting local chromatin state and downstream transcription (39). To assess the potential function of Mettl3 on chromatin openness and nascent transcripts synthesis in BMDMs, we performed deoxyribonuclease I (DNase I)–terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL) and 5-ethynyl uridine (EU) labeling assays in BMDMs from Mettl3flox/flox and Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice (fig. S7, A and B). Similar chromatin accessibility and nascent transcripts synthesis were observed between WT and Mettl3-deficient BMDMs (fig. S7, A and B). Furthermore, by analyzing the m6A-modified carRNAs in macrophages based on our MeRIP-seq data, we did not identify any significant m6A peaks on paRNA and eRNA upstream of Tnf-α and Irakm (fig. S7, C and D), under the conditions that successfully called significant m6A-marked carRNAs for genes such as Vars (fig. S8A). In addition, no significant carRNAs were identified in BMDMs for TLR-related genes, including TRIAP, MyD88, TRAF6, IRAK4, and TRAM (fig. S8, B to E). Further, although carRNAs of Irakm were observed in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) (table S4), no significant Irakm carRNAs were identified in BMDMs of our MeRIP-seq data. In addition, our MeRIP-qPCR results showed that the levels of Irakm carRNAs were largely unchanged with knockout of METTL3 in BMDMs, except for a slight decrease in Irakm eRNA(+), which may account for the slightly increased transcription of Irakm in METTL3-KO BMDMs. Therefore, in contrast to the findings in mESCs, our results demonstrated that in macrophages, m6A regulates TNF-a production by targeting the degradation of Irakm mRNA.

DISCUSSION

RBPs play a vital role in RNA metabolism, which is tightly connected to all aspects of cellular functions. However, the mechanisms by which RBP-mediated RNA regulation affects the activation of innate immune cells are largely unknown. Here, we have identified METTL3 as a positive regulator of the innate response of macrophages by using pooled RBP CRISPR-Cas9 screens. Specifically, we have demonstrated that METTL3-mediated m6A modification of Irakm mRNA accelerates its degradation, resulting in reprogramming macrophages for activation. These findings provide a previously unappreciated mechanism for epitranscriptional control of innate response in macrophages. Nevertheless, we have not observed high-ranked individual m6A readers in either TNF-α–Low or TNF-α–Hi cell population in our pooled RBP CRISPR-Cas9 screening. The functional redundancy of YTHDF proteins appears to exist in the innate immune response of macrophages (33, 34), and our data show that the simultaneous knockdown of Ythdf1, Ythdf2, and Ythdf3, in contrast to knocking down each of these readers individually, can significantly reduce Tnf-α expression upon LPS stimulation.

Recent studies have shown that transcripts of key genes of the innate immune signaling pathway are marked by m6A modifications, which are required for the maintenance of proper innate antiviral responses (27, 28, 40, 41) or are essential for dendritic cell activation (26), indicating that the m6A modification is implicated in innate immune responses. Our data document that Mettl3 deficiency in macrophages reduces their proinflammatory cytokine production and thus suppresses their ability to defend against pathogens and eliminate tumors. Thus, the METTL3/m6A modification appears to be required for macrophage activation–mediated innate immunity.

Activation of the TLR4 signaling and subsequent induction of effective positive feedback to augment immune response by proinflammatory cytokines has a pivotal role in eliminating invading pathogens. However, the magnitude of the immune response must be tightly regulated to avoid pathologic immune reactions. A previous study has shown that TLR4 activation could negatively regulate the stimulation of macrophages by inducing the expression of Irakm (14). Our data document that Mettl3-KO macrophages have a higher level of IRAKM expression than their WT counterparts, resulting in reduced TLR4 signaling. Except for TLR4 signaling, we observed that Mettl3 deficiency could decrease TNF-α expression upon the activation of TLR3 or TLR9 signaling individually. These data support our previously proposed m6A working model in which m6A acts as a “gas pedal” specifically targeting immediate-early response genes, such as Socs in T cells and Irakm in macrophages, to trigger their rapid degradation and to ensure that the immune cells can quickly respond to the external stimuli and adapt to the environment (24). Later on, these cells increase the expression levels of Socs or Irakm genes to “brake” the signaling by a feedback mechanism, thus preventing its overactivation.

The MeRIP-seq data demonstrated that Irakm transcripts were marked by m6A modifications, removal of which retarded the degradation of Irakm mRNA, and the resulting excess of IRAKM protein blocked the TLR4 signaling. Thus, Irakm mRNA decay controlled by m6A modification represents a novel mechanism of releasing the brake from the TLR4 signaling pathway. Consistently, our previous study showed that m6A modification selectively targets the transcripts of the SOCS family genes, the “gatekeeper” of the IL-7/STAT5 signaling pathway, accelerating their degradation necessary to reprogram naive T cells for differentiation and proliferation (24). It was also demonstrated that IRAKM promotes lung tumor growth (42) and fibrosis in multiple organs (15, 43) by skewing macrophage toward an alternative activated phenotype. Mettl3-deficient mice displayed enhanced tumor growth. TAMs and BMDMs from Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice polarized with either TCM or IL-4 exhibited elevated M2-related markers, suggesting that the balance of macrophage polarization was modulated at an epitranscriptional level by the m6A modification of Irakm mRNA.

A recent study reported that the m6A modification promotes dendritic cell activation by enhancing the translation of target transcripts, CD40, CD80, and Tirap (26). However, our MeRIP-seq data documented that CD40 transcripts were not m6A-marked, indicating that the targets of m6A modification may be cell type specific. Moreover, the m6A peaks of CD80 and Tirap mRNA were not affected in Mettl3-deficient macrophages, suggesting the presence of additional unidentified m6A writer (s) catalyzing the m6A modification of CD80 and Tirap transcripts in macrophages; such a possibility warrants further investigation.

The high ranking of m6A writer genes in our CRISPR screening indicates the fundamental importance of m6A regulation in macrophage activation. It has been recently reported that m6A on carRNAs can globally tune chromatin state and transcription (39). However, neither did we observe a difference in chromatin openness and nascent RNA synthesis between BMDMs from Mettl3flox/flox mice and Mettl3flox/flox;Lyzm-Cre mice, nor did we identify a significant m6A peak on paRNA and eRNA upstream of Tnf-α and Irakm. Moreover, no significant carRNAs from TLR-related genes were identified. Therefore, in contrast to the observations in mESCs, our results demonstrated that in macrophages, m6A regulates the levels of TNF-α posttranscriptionally, mostly by targeting the degradation of Irakm mRNA. In addition, we found that the m6A levels of carRNAs for Esrrb, Kmt2d, and LINE, which have been proven to be decreased in Mettl3-KO mESCs, were not totally decreased in Mettl3-KO BMDMs (fig. S9). The difference in m6A effects on chromatin status between METTL3-KO mESCs and METTL3-KO BMDMs may reflect differences in cellular contents and environmental context of stimuli-sensitive immune cells versus pluripotent ESCs (21, 34).

In summary, our study demonstrates that m6A modification represents a novel mechanism controlling the innate immune response of macrophages against environmental stimuli. In addition, the obtained results suggest that targeting m6A modulators might be an effective therapeutic approach for inflammatory diseases and cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Mettl3flox/flox mice were generated as previously described (24) and crossed with Lyzm-Cre mice (the Jackson laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) to obtain CKO mice. The animals were maintained in specific pathogen–free facilities and used according to protocols approved by Animal Care and Use Committees of the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine.

Infection

Age- and sex-matched Mettl3-WT and Mettl3-KO mice were infected orally with S. typhimurium strain ATCC 14028 at 108 bacteria per mouse. Body weights were monitored daily. Four days after infection, the bacterial burden in the spleen, liver, colon, and feces was determined by counting the colony-forming units (CFU) of the homogenized tissue on MacConkey agar plates.

Tumor model

MC38 murine colon adenocarcinoma cells were provided by Q. Zou, Shanghai Institute of Immunology of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai. MC38 cancer cells were injected subcutaneously into 8-week-old female mice (5 × 105 cells per mouse). Tumor growth was measured as the tumor area.

Pooled CRISPR screening

For the pooled CRISPR screen, we designed 7272 sgRNAs targeting 782 RBPs using CRISPR-FOCUS (http://cistrome.org/crispr-focus/), listed in table S2. sgRNAs were cloned into lenti-puro-guide plasmid following an established protocol (31). Lenti-sgRNA constructs and packaging vectors (pMD2.G and psPAX2) were cotransfected into HEK293T cells, and virus-containing supernatant was collected. Cas9-expressing Raw 264.7 cells were infected with the lentiviral library at an infection rate of 30% and selected with puromycin. Seven days after selection, the infected cells were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) plus brefeldin A for 6 hours and fixed and stained with phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated TNF-α antibody for fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

High-throughput sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

The genomic DNA of cells collected just before sorting or sorted on the basis of TNF-α expression was isolated. The sgRNA library was barcoded and amplified with primers listed in table S3 for two rounds of PCR. Amplicons were purified and quantified for sequencing on Illumina HiSeq. The sequencing data generated from the screen and raw sgRNA counts have been submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Database of Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) Dataset under accession number GSE162469.

Dot blot assay

Total RNA from Raw 264.7 cells or BMDMs was extracted and enriched in mRNA with Dynabeads mRNA Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Ambion, 61006). mRNAs were then denatured at 95°C for 3 min and chilled on ice immediately. A 2-μl drop of mRNA was applied directly onto Amersham Hybond-N+ membrane (GE Healthcare, RPN203B) and cross-linked to the membrane by Stratalinker 2400 UV Crosslinker. Unbounded mRNA was washed off with TBST [1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 0.02% Tween 20] for 5 min at room temperature and blocked with 5% nonfat milk in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature. The m6A level was determined with an anti-m6A antibody (Synaptic Systems, 202003).

Western blotting

Cells were collected and lysed on ice for 30 min in radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer containing cocktails of protease and phosphatase inhibitors, and the supernatants were subject to Western blot analysis.

Flow cytometry

BMDMs and Raw 264.7 cells were stimulated with LPS, IL-4, or TCM along with Golgi inhibitor for the indicated time. Then, single-cell suspensions were prepared from either cultured cells or tumor samples and incubated with antibody cocktails for 15 min at 4°C for cell surface staining. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were fixed with BD Fixation/Permeabilization buffer (BD 554714) for 30 min at 4°C and subsequently stained with antibodies for 30 min at 4°C. Data were recorded on BD LSRFortessa X-20 and analyzed with FlowJo software.

Tumor-conditioned medium

MC38 cancer cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 72 hours. The supernatant was collected, centrifuged, and stored at −80°C for further use.

Isolation and differentiation of BMDMs

Bone marrow cells were isolated from the hind leg femur of mice and differentiated into macrophages in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco) and 20% L929 cell culture supernatant for 7 days. Differentiated BMDMs were collected and replated in DMEM without the L929 cell culture supernatant for 12 hours and then stimulated with LPS (Sigma-Aldrich L2880, 10 ng/ml) and IL-4 (PeproTech 214-14-20, 25 ng/ml) for M1 and M2 polarization, respectively.

Plasmid construction and mutagenesis assays

pLVX-IRES-ZsGreen lentiviral vectors were a gift from Q. Zou (Shanghai Institute of Immunology, China). Lentiviruses encoding Mettl3 and their mutants in pLVX-IRES-ZsGreen plasmids were produced in 293T cells, then collected, filtered through a 0.22-μm MCE membrane (Millipore), and used to infect BMDMs. MG-guide retrovirus vectors were a gift from R.A.F. (Department of Immunobiology, Yale University School of Medicine, USA). Retroviruses expressing specific shRNA targeting Irakm in MG-guide plasmids were produced and used to infect BMDMs as described above. The shRNA target Irakm transcripts are listed in table S3. The WT and m6A motif disrupted 3′UTRs of Irakm were synthesized and cloned into MG-guide plasmids.

RNA interference

siRNAs targeting Ythdf1, Ythdf2, Ythdf3, and Ythdc1 were transfected into BMDMs using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were analyzed 48 to 72 hours later. The siRNA sequences are listed in table S3.

DNase I–TUNEL experiment

The analysis of chromatin openness with DNase I–TUNEL assay was performed according to the method of Liu et al. (39). Briefly, BMDMs were permeabilized by 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min before digesting with DNase I (0.2 U/ml; New England Biolabs) and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Subsequently, the TUNEL assay (DeadEnd Fluorometric TUNEL System, Promega) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions and followed by DAPI staining. Images were captured with an Olympus FV3000 confocal microscope, and the intensity of the nuclear TUNEL signal was quantified using ImageJ software.

Nascent RNA labeling assay

Nascent transcripts synthesis was analyzed according to the method of Liu et al. (39). Briefly, BMDMs were cultured on precoated cover glasses. A nascent RNA synthesis assay was conducted 24 hours later using the Click-iT RNA Imaging Kit (Invitrogen, C10329) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Images were captured with an Olympus FV3000 confocal microscope, and the intensity of the signal was quantified using ImageJ software.

Nascent RNA transcription rate measurement by qPCR

Nascent transcription rate was analyzed according to the method of Liu et al. (39). Briefly, BMDMs were seeded to the same amount of cells. After 48 hours, EU was added to 0.5 mM at 60, 30, 20, and 10 min before trypsinization collection. Total RNA was purified by TRIzol, and nascent RNA was captured by using Cell-Light EU Nascent RNA Capture Kit (RiboBio). RNA amount and EU adding time were fitted to a linear equation, and the slope was estimated as transcription rate of RNA.

Chromosome-associated RNA MeRIP-qPCR

The m6A level of chromosome-associated RNAs was analyzed according to the method of Liu et al. (39). Briefly, total RNA was isolated from the chromosome-associated fraction of BMDMs, and nonribosomal RNA was further enriched by using Ribo-off rRNA Depletion Kit (human/mouse/rat; Vazyme). Fragmentation and MeRIP-qPCR were performed following the protocol in this paper.

Library preparation and Illumina HiSeq sequencing

RNA purification, reverse transcription, library construction, and sequencing were performed at WuXi NextCODE (Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina). Briefly, polyadenylated mRNA was purified from total RNA using oligo-dT–attached magnetic beads and fragmented by the fragmentation buffer. Taking these short fragments as templates, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized using reverse transcriptase and random primers, followed by the second-strand cDNA synthesis. The synthesized cDNA was subjected to end repair, phosphorylation, and “A” base addition, according to Illumina’s library construction protocol. Next, Illumina sequencing adapters were added to both sides of the cDNA fragments. After PCR amplification for DNA enrichment, the target fragments of 200 to 300 base pairs (bp) were cleaned up.

After library construction, Qubit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to quantify the concentration of the resulting sequencing libraries, while the size distribution was determined using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent). Then, the Illumina cBot cluster generation system with HiSeq PE Cluster Kits (Illumina) was used to generate clusters. Paired-end sequencing was performed at WuXi NextCODE (Shanghai, China) using an Illumina HiSeq system following the manufacturer’s protocols for 2 × 150 paired-end sequencing. These RNA-seq data have been deposited on GEO public database under the accession number GSE162248.

MeRIP-qPCR and MeRIP-seq

Total RNA from WT or Mettl3-KO Raw 264.7 cells (with or without LPS stimulation) was extracted with the TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15596018), and approximately 100 μg of total RNA for each condition was fragmented to ~100 bp in length with fragmentation buffer (10 mM tris-HCl and 10 mM ZnCl2). The RNA size after the fragmentation was validated by 2200 TapeStation detection (Agilent). A sample of 100 ng of the fragmented RNA was saved as the input control, while the remaining RNA was mixed with 50 μl of protein A magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 10002D) and 50 μl of protein G magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 10004D) premixed with 10 μg of anti-m6A antibody (Merck Millipore, ABE572). The samples were incubated for 4 hours at 4°C in IP buffer [10 mM tris-HCl, 30 mM NaCl, and 0.1% (v/v) IGEPAL CA-630 supplemented with ribonuclease (RNase) inhibitor]. The beads were washed twice with 1× IP buffer, twice with low-salt IP buffer [50 mM NaCl, 10 mM tris-HCl (pH7.5), and 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630], and twice in 1000 μl of high-salt IP buffer [500 mM NaCl, 10 mM tris-HCl (pH7.5), and 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630]. RNA was eluted and purified with the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN) and eluted with 15-μl RNase-free water. Both input and enriched RNA samples were used for library preparation with TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Human/Mouse/Rat (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For MeRIP-qPCR, approximately 1 μg of total RNA from WT or Mettl3-KO BMDMs was used. The input and enriched RNA were prepared using the same protocol as described above, but with scaled-down reagents, and dissolved in 10 μl of RNase-free water. The enrichment of m6A was analyzed using the LightCycler 480. Myc peak and Myc body were used, respectively, as a positive and negative control for MeRIP-qPCR.

Analysis of m6A RIP-seq

The raw reads were mapped to mouse ribosomal RNA sequences using bowtie2 to remove the reads that came from ribosomal RNA. The unmapped reads were then mapped to the mouse genome (GRCm38.p6 and gencode.vM20) using STAR. The potential bias caused by PCR amplification was removed using the Picard Mark Duplicates command. For m6A-seq data, the fragment coverage of each base of all transcripts was calculated using custom script. The peak calling algorithm was modified from Ma et al. (44). To calculate the enrichment score, the average fragment coverage of the window was used instead of the read count. The m6A level on carRNAs upstream of indicated genes was analyzed according to the method from Liu et al. (39). The m6A RIP-seq data from this study have been deposited to GEO series GSE162254.

RNA degradation assay

BMDMs were seeded on 24-well plates with 1 million cells per well. Actinomycin D was added at a final concentration of 5 μM. Cells were collected (after 0, 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 hours), and total RNA was extracted for real-time qPCR. Data were normalized to the t = 0 time point.

Dual-luciferase assay

pGL4-luc2 (Firefly luciferase) vector of the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, E1910) was used to determine the function of m6A modification within the 3′UTR of Irakm transcripts. The assay was performed according to the manufacture’s instruction: Briefly, 100 ng of WT or m6A-mutant IRAKM-3′UTR and 25 ng of pRL-TK (Renilla luciferase) control vector were cotransfected into HEK293T cells in triplicates. The relative luciferase activity was accessed 24 to 48 hours after transfection.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as means ± SEM. Comparisons between groups were analyzed by the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 6 (GraphPad).

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Yang, S. Hu, Y. Zhou, and all other members of the Hua-Bing Li laboratory for discussions and comments. Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91753141/82030042/32070917 to H.-B.L., 81822021/91842105 to S.Z., 81801550 to J.T., and 81901580 to Y.L.), the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (grant no. 20JC1417400/201409005500/20JC1410100 to H.-B.L.), the Program for Professor of Special Appointment (Eastern Scholar) at Shanghai Institutions of Higher Learning (to H.-B.L.), the start-up fund from the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (to H.-B.L.), the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFA0508000) (to S.Z.), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB29030101) (to S.Z.), and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to R.A.F.). Author contributions: H.-B.L. conceived the project and designed the research. J.T., X.W., and Y.L. designed and performed the murine portion of the study. H.-B.L., J.T., and X.W. analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. X.R., A.W., and S.Z. performed and analyzed the bacterial infection model. Y.L. and J.Y. generated Mettl3-deficient Raw 264.7 cells, and Y.L., J.Y., and K.M. helped with experiments involving Raw 264.7 cells. Q.Z. provided MC38 cells. Z.C. and Y.Z. helped with analyzing RNA-seq data. W.P., Q.Z., Y.Z., Q.X., J.L., S.Z., R.A.F., and H.-B.L. discussed the projects. This study was supervised by H.-B.L. and R.A.F. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Competing interests: R.A.F. is a consultant for GSK and Zai Lab Ltd. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Sequenced reads have been deposited in the NCBI GEO database (accession nos. GSE162254, GSE162248, and GSE162469). Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/7/18/eabd4742/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Kawai T., Akira S., Toll-like receptors and their crosstalk with other innate receptors in infection and immunity. Immunity 34, 637–650 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray P. J., Macrophage polarization. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 79, 541–566 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noy R., Pollard J. W., Tumor-associated macrophages: From mechanisms to therapy. Immunity 41, 49–61 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vitale I., Manic G., Coussens L. M., Kroemer G., Galluzzi L., Macrophages and metabolism in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Metab. 30, 36–50 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeNardo D. G., Ruffell B., Macrophages as regulators of tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 19, 369–382 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mantovani A., Marchesi F., Malesci A., Laghi L., Allavena P., Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 14, 399–416 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassetta L., Pollard J. W., Targeting macrophages: Therapeutic approaches in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17, 887–904 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawai T., Akira S., The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: Update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 11, 373–384 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook D. N., Pisetsky D. S., Schwartz D. A., Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of human disease. Nat. Immunol. 5, 975–979 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su J., Zhang T., Tyson J., Li L., The interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase M selectively inhibits the alternative, instead of the classical NFκB pathway. J. Innate Immun. 1, 164–174 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu D., Zhang H., Wang X., Chen Y., Expression of IRAK-3 is associated with colitis-associated tumorigenesis in mice. Mol. Med. Rep. 16, 3415–3420 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandes P., MacSharry J., Darby T., Fanning A., Shanahan F., Houston A., Brint E., Differential expression of key regulators of Toll-like receptors in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: A role for Tollip and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma? Clin. Exp. Immunol. 183, 358–368 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunaltay S., Nyhlin N., Kumawat A. K., Tysk C., Bohr J., Hultgren O., Hultgren Hornquist E., Differential expression of interleukin-1/Toll-like receptor signaling regulators in microscopic and ulcerative colitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 12249–12259 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi K., Hernandez L. D., Galan J. E., Janeway C. A. Jr., Medzhitov R., Flavell R. A., IRAK-M is a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell 110, 191–202 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ballinger M. N., Newstead M. W., Zeng X., Bhan U., Mo X. M., Kunkel S. L., Moore B. B., Flavell R., Christman J. W., Standiford T. J., IRAK-M promotes alternative macrophage activation and fibroproliferation in bleomycin-induced lung injury. J. Immunol. 194, 1894–1904 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou H., Yu M., Fukuda K., Im J., Yao P., Cui W., Bulek K., Zepp J., Wan Y., Kim T. W., Yin W., Ma V., Thomas J., Gu J., Wang J. A., DiCorleto P. E., Fox P. L., Qin J., Li X., IRAK-M mediates Toll-like receptor/IL-1R-induced NFκB activation and cytokine production. EMBO J. 32, 583–596 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng J. C., Cheng G., Newstead M. W., Zeng X., Kobayashi K., Flavell R. A., Standiford T. J., Sepsis-induced suppression of lung innate immunity is mediated by IRAK-M. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 2532–2542 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong J., Flavell R. A., Li H. B., RNA m6A modification and its function in diseases. Front. Med. 12, 481–489 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaccara S., Ries R. J., Jaffrey S. R., Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 608–624 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Y., Hsu P. J., Chen Y. S., Yang Y. G., Dynamic transcriptomic m6A decoration: Writers, erasers, readers and functions in RNA metabolism. Cell Res. 28, 616–624 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi H., Wei J., He C., Where, when, and how: Context-dependent functions of RNA methylation writers, readers, and erasers. Mol. Cell 74, 640–650 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao G., Li H. B., Yin Z., Flavell R. A., Recent advances in dynamic m6A RNA modification. Open Biol. 6, 160003 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shulman Z., Stern-Ginossar N., The RNA modification N6-methyladenosine as a novel regulator of the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 21, 501–512 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H. B., Tong J., Zhu S., Batista P. J., Duffy E. E., Zhao J., Bailis W., Cao G., Kroehling L., Chen Y., Wang G., Broughton J. P., Chen Y. G., Kluger Y., Simon M. D., Chang H. Y., Yin Z., Flavell R. A., m6A mRNA methylation controls T cell homeostasis by targeting the IL-7/STAT5/SOCS pathways. Nature 548, 338–342 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong J., Cao G., Zhang T., Sefik E., Amezcua Vesely M. C., Broughton J. P., Zhu S., Li H., Li B., Chen L., Chang H. Y., Su B., Flavell R. A., Li H. B., m6A mRNA methylation sustains Treg suppressive functions. Cell Res. 28, 253–256 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H., Hu X., Huang M., Liu J., Gu Y., Ma L., Zhou Q., Cao X., Mettl3-mediated mRNA m6A methylation promotes dendritic cell activation. Nat. Commun. 10, 1898 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y., You Y., Lu Z., Yang J., Li P., Liu L., Xu H., Niu Y., Cao X., N6-methyladenosine RNA modification-mediated cellular metabolism rewiring inhibits viral replication. Science 365, 1171–1176 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng Q., Hou J., Zhou Y., Li Z., Cao X., The RNA helicase DDX46 inhibits innate immunity by entrapping m6A-demethylated antiviral transcripts in the nucleus. Nat. Immunol. 18, 1094–1103 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y., Wang X., Zhang X., Wang J., Ma Y., Zhang L., Cao X., RNA-binding protein YTHDF3 suppresses interferon-dependent antiviral responses by promoting FOXO3 translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 976–981 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han D., Liu J., Chen C., Dong L., Liu Y., Chang R., Huang X., Liu Y., Wang J., Dougherty U., Bissonnette M. B., Shen B., Weichselbaum R. R., Xu M. M., He C., Anti-tumour immunity controlled through mRNA m6A methylation and YTHDF1 in dendritic cells. Nature 566, 270–274 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joung J., Konermann S., Gootenberg J. S., Abudayyeh O. O., Platt R. J., Brigham M. D., Sanjana N. E., Zhang F., Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout and transcriptional activation screening. Nat. Protoc. 12, 828–863 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parnas O., Jovanovic M., Eisenhaure T. M., Herbst R. H., Dixit A., Ye C. J., Przybylski D., Platt R. J., Tirosh I., Sanjana N. E., Shalem O., Satija R., Raychowdhury R., Mertins P., Carr S. A., Zhang F., Hacohen N., Regev A., A genome-wide CRISPR screen in primary immune cells to dissect regulatory networks. Cell 162, 675–686 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaccara S., Jaffrey S. R., A unified model for the function of YTHDF proteins in regulating m6A-modified mRNA. Cell 181, 1582–1595.e18 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lasman L., Krupalnik V., Viukov S., Mor N., Aguilera-Castrejon A., Schneir D., Bayerl J., Mizrahi O., Peles S., Tawil S., Sathe S., Nachshon A., Shani T., Zerbib M., Kilimnik I., Aigner S., Shankar A., Mueller J. R., Schwartz S., Stern-Ginossar N., Yeo G. W., Geula S., Novershtern N., Hanna J. H., Context-dependent functional compensation between Ythdf m6A reader proteins. Genes Dev. 34, 1373–1391 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.West A. P., Koblansky A. A., Ghosh S., Recognition and signaling by Toll-like receptors. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 409–437 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao B. S., Roundtree I. A., He C., Post-transcriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 31–42 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roignant J. Y., Soller M., m6A in mRNA: An ancient mechanism for fine-tuning gene expression. Trends Gen. 33, 380–390 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee Y., Choe J., Park O. H., Kim Y. K., Molecular mechanisms driving mRNA degradation by m6A modification. Trends Gen. 36, 177–188 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu J., Dou X., Chen C., Chen C., Liu C., Xu M. M., Zhao S., Shen B., Gao Y., Han D., He C., N6-methyladenosine of chromosome-associated regulatory RNA regulates chromatin state and transcription. Science 367, 580–586 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang L., Wen M., Cao X., Nuclear hnRNPA2B1 initiates and amplifies the innate immune response to DNA viruses. Science 365, eaav0758 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winkler R., Gillis E., Lasman L., Safra M., Geula S., Soyris C., Nachshon A., Tai-Schmiedel J., Friedman N., Le-Trilling V. T. K., Trilling M., Mandelboim M., Hanna J. H., Schwartz S., Stern-Ginossar N., m6A modification controls the innate immune response to infection by targeting type I interferons. Nat. Immunol. 20, 173–182 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Standiford T. J., Kuick R., Bhan U., Chen J., Newstead M., Keshamouni V. G., TGF-β-induced IRAK-M expression in tumor-associated macrophages regulates lung tumor growth. Oncogene 30, 2475–2484 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steiger S., Kumar S. V., Honarpisheh M., Lorenz G., Gunthner R., Romoli S., Grobmayr R., Susanti H. E., Potempa J., Koziel J., Lech M., Immunomodulatory molecule IRAK-M balances macrophage polarization and determines macrophage responses during renal fibrosis. J. Immunol. 199, 1440–1452 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma L. J., Zhao B. X., Chen K., Thomas A., Tuteja J. H., He X., He C., White K. P., Evolution of transcript modification by N6-methyladenosine in primates. Genome Res. 27, 385–392 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/7/18/eabd4742/DC1