Abstract

The term ‘hip–spine syndrome’ was introduced in recognition of the frequent occurrence of concomitant symptoms at the hip and lumbar spine. Limitations in hip range of motion can result in abnormal lumbopelvic mechanics. Ischiofemoral impingement, femoroacetabular impingement and abnormal femoral torsion are increasingly linked to abnormal hip and spinopelvic biomechanics. The purpose of this narrative review is to explain the mechanism by which these three abnormal hip pathologies contribute to increased low back pain in patients without hip osteoarthritis. This paper presents a thorough rationale of the anatomical and biomechanical characteristics of the aforementioned hip pathologies, and how each contributes to premature coupling and limited hip flexion/extension. The future of hip and spine conservative and surgical management requires the implementation of a global hip–spine–pelvis-core approach to improve patient function and satisfaction.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of chronic low back pain in individuals aged between 20 and 69 years old is estimated at 13.1% in the United States [1]. Failure to improve after treatment for low back pain is a frequent clinical observation. Total expenditures in the United States with spine problems increased 65% (adjusted for inflation) from 1997 to 2005, raising more rapidly than the overall health expenditures [2]. The growth in cost to treat chronic spine conditions has not resulted in improved function or quality of life. The estimated proportion of persons with spine problems who self-reported physical functioning limitations increased from 20.7% to 24.7% between 1997 and 2005 [2]. Therefore, there is a need to better understand the potential sources of low back pain not located at the lumbar spine, particularly abnormal hip biomechanics [3].

The term hip–spine syndrome was first described by Offierski in 1983 [3]. The classical definition of hip–spine syndrome considers a concomitant hip and spine pathology and differentiates presentation as ‘simple’, ‘complex’ and ‘secondary’. The classification ‘simple’ hip–spine syndrome considers either the hip or spine as the source of pain, whereas the ‘complex’ classification does not have clear pathologic hip or spine source. The ‘secondary’ classification refers to an inter-related coexistence of hip and spine pathology [3]. This rudimentary classification requires updating based on current understanding of biomechanics. Hip abnormalities limiting hip flexion and/or extension require compensation from the pelvis and lumbar spine for the lack of sagittal movement at the hip [4]. Between 13.1% and 37.5% of the total hip flexion is provided by the pelvis through sagittal movement at the lumbopelvic area [4]. Abnormalities at the hip joint contributing to low back pain include flexion deformities [3], osteoarthritis [5], developmental dysplasia [6] and limited hip range of motion (ROM) [3, 7–12]. The restoration of the hip ROM has been associated with improvement in lumbar spine function following total hip arthroplasty in individuals with hip osteoarthritis [13–18]. A study reported complete resolution of low back pain in 66% of the patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty for hip osteoarthritis and had lumbar symptoms before surgery [14].

Current diagnostic and treatment methods for hip and lumbar spine pathologies have largely focused on individual components without accounting for secondary effects in adjacent anatomical areas. Abnormal femoral torsion, femoroacetabular impingement and ischiofemoral impingement (IFI) can have secondary effects on the lumbar spine. The purpose of this narrative review is to explain the mechanism by which these three hip abnormalities contribute to increased low back pain in patients without hip osteoarthritis.

ISCHIOFEMORAL IMPINGEMENT

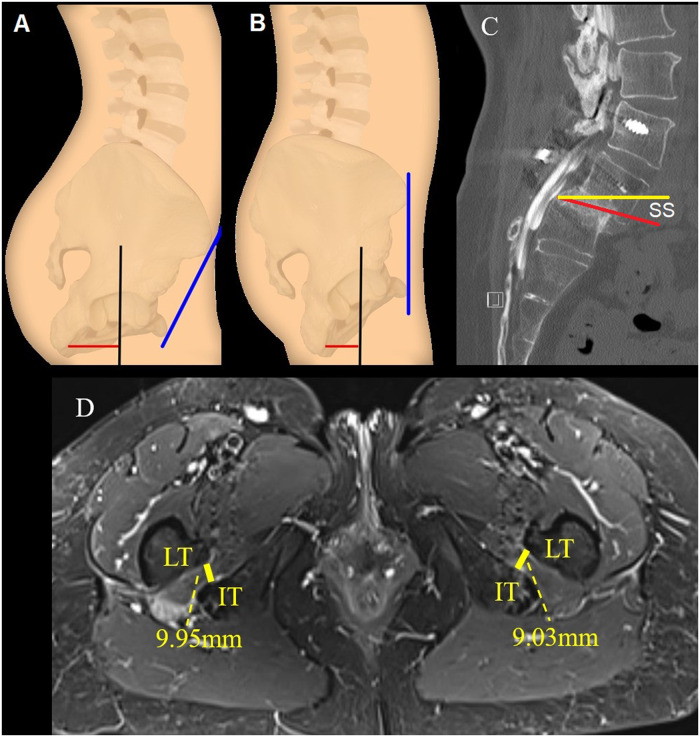

Ischiofemoral impingement is characterized by conflict between the ischium and the lesser trochanter (Fig. 1). The smallest distance between these two osseous structures is traditionally defined on magnetic resonance studies obtained supine. An ischiofemoral space smaller than 17 mm has been utilized for the imaging diagnosis of IFI [19, 20]. Atkins et al. reported that the ischiofemoral space decreases 8 mm or more along the different phases of the gait cycle [21]. The ischiofemoral space measure in magnetic resonance studies obtained supine overestimates the space along the gait cycle, and is dependent on the positioning of the lower limbs. The dynamic relationship between the ischium and lesser trochanter makes the physical examination fundamental for the diagnosis of IFI. Extension and adduction beyond zero degrees should be added during physical exam testing for IFI to reproduce the dynamic space between the lesser trochanter and the ischium [21].

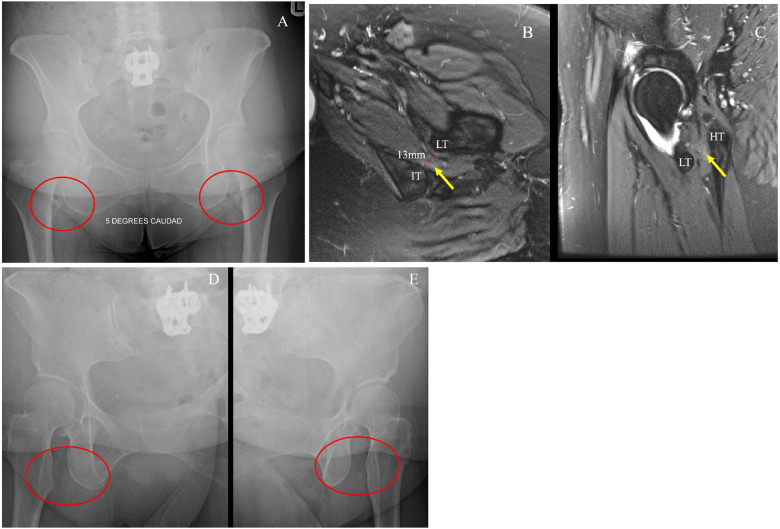

Fig. 1.

Ischiofemoral impingement diagnosed following unsuccessful spinal fusion procedure. (A) Patient presenting with bilateral ischiofemoral impingement, diagnosed following an unsuccessful L5–S1 spine fusion procedure. (B) Axial MRI of left hip. Yellow arrow pointing to quadratus femoris edema associated with decreased ischiofemoral space (13 mm) (LT: lesser trochanter; IT: ischial tuberosity). (C) Sagittal MRI of left hip. Yellow arrow pointing to quadratus femoris edema between the LT and HT (HT: hamstrings tendon). (D and E) Radiographies taken 1 year after lesser trochanterplasty.

Gómez-Hoyos et al. simulated an IFI model to evaluate the effects at the lumbar spine resulting from limited hip extension [22]. Significant increase in lumbar facet joint loading was observed for the L3–L4 and L4–L5 segments in the IFI state. An average 30.81% increase in facet joint overload was observed between IFI state and non-IFI state. Finite element analysis data reflected similar trends of increased loading in lumbar facet joints during terminal hip extension with IFI, compared with a non-IFI condition (Fig. 2). The result of the limitation in hip extension on the lumbar spine is partially explained by the difference between the length of the lower limb compared with the short lever arm of the hip joint.

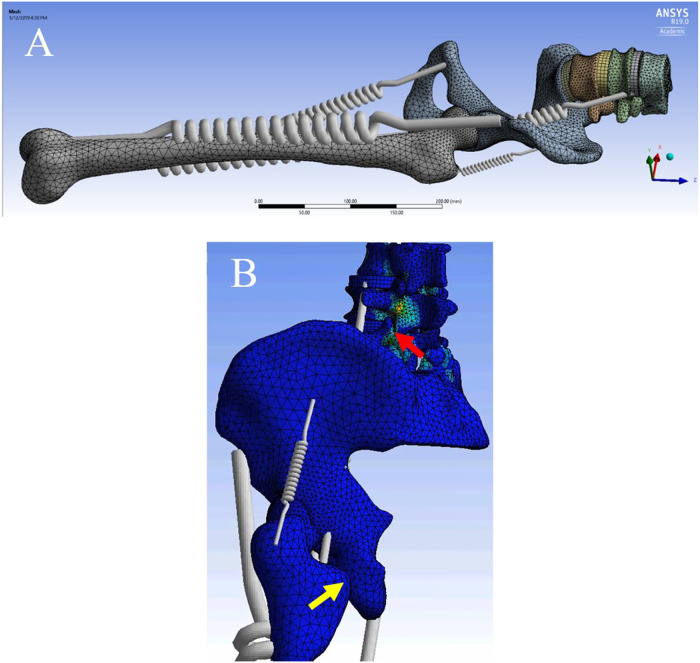

Fig. 2.

Finite element analysis in an ischiofemoral impingement model derived from cadaveric specimens. (A) The soft tissues are modeled as springs to simulate kinematic chain effects. (B) Lumbar facet joint loading observed (red arrow) during hip extension with ischiofemoral impingement (yellow arrow).

FEMOROACETABULAR IMPINGEMENT

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is increasingly recognized as a cause of abnormal hip biomechanics [23, 24]. Cam impingement is characterized by a bony overgrowth resulting in an increased radius of the femoral neck at the femoral head–neck junction [25]. This overgrowth produces shear forces resulting in an ‘outside-in’ acetabular cartilage damage and labral tears. Presence of a cam-type impingement amplifies the damage as the femoral head–neck junction rolls into the acetabulum (Fig. 3) [24]. Pincer impingement is abnormal acetabular coverage. Cam and pincer deformities cause premature femoroacetabular coupling in flexion and affect the lumbopelvic structures: pubic symphysis, sacroiliac joint, and lumbar spine, in addition to muscular structures across the pelvis [26–32]. The abnormal bony hip anatomy alters normal lumbopelvic function and increases mechanotransduction to the lumbar spine. Kim et al. reported decreased hip flexion and increased pelvic tilt in the seated position in subjects with low back pain [33]. Birmingham et al. reported a 35% increase in pubic symphysis rotation provoked by cam impingement [32].

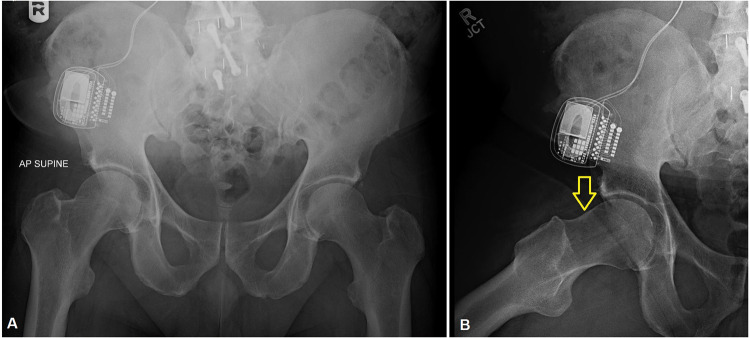

Fig. 3.

Hip–spine syndrome. (A) Anteroposterior radiograph of pelvis demonstrating spine fusion (green arrow) and a pain neurostimulator to treat low back pain in a patient with cam-type femoroacetabular impingement. (B) Dunn view demonstrating cam deformity (yellow arrow).

Lamontagne et al. studied pelvic motion during maximal squat in subjects with cam impingement [31]. A decrease of 9.5° in sagittal pelvic range of motion was observed in the FAI group compared to the control group. The authors proposed premature contact between the femur and acetabulum may occur due to decreased pelvic motion in patients with FAI [31]. Fader et al. compared the spinopelvic mechanics from standing and sitting positions in subjects with and without FAI [34]. Compared with non-FAI controls, symptomatic patients with FAI had less flexion at the spine (mean 22° versus mean 35°) and more at the hip (mean 72° versus mean 62°) [34]. The authors concluded that limited spine mobility is present in symptomatic patients with FAI, requiring more flexion at the hip to achieve sitting position, which may lead to impingement between the acetabulum and proximal femur [34]. Weinberg et al reported the association between radiographic signs of FAI and decreased pelvic incidence [35]. In a cadaveric study, Gebhart et al. also reported association between decreased pelvic incidence and cam and pincer deformities [36]. Gebhart et al. theorized that the restriction of range of motion and biomechanical adaptations of the pelvis around the hip joints resulting from a smaller PI may affect hip development and FAI. A major limitation of the abovementioned studies on the effects of FAI on the sagittal spinopelvic is the lack of femoral torsion assessment.

Decreased hip range of motion is associated with low back pain [9, 37–41]. Cam and pincer impingements have been described to increase sacroiliac and lumbar spine stresses [10, 12, 42–44]. Khoury et al. conducted a study to investigate the effect of cam-type impingement on lumbar spine loading [45] (Fig. 4). Those authors inserted force transduction sensors into the lumbar intervertebral discs through an anterior approach, and measured the forces before and after a cam-type morphology was artificially created at the femoral head–neck junction [45]. Increased peak intradiscal loading was observed in the L5–S1 intervertebral disk compared to L4–L5 and L3–L4 (P < 0.001). Hip flexion at 120° with neutral rotation and hip flexion with internal rotation resulted in the largest intradiscal pressure. A finite element analysis model confirmed the cadaveric findings and displayed an increase in intervertebral disk loading during terminal hip flexion with a cam-type impingement, compared to a native control. A finite element study confirmed a direct kinematic chain relationship between simulated anterior hip impingement and lumbar intradiscal pressure during hip flexion with internal rotation [45].

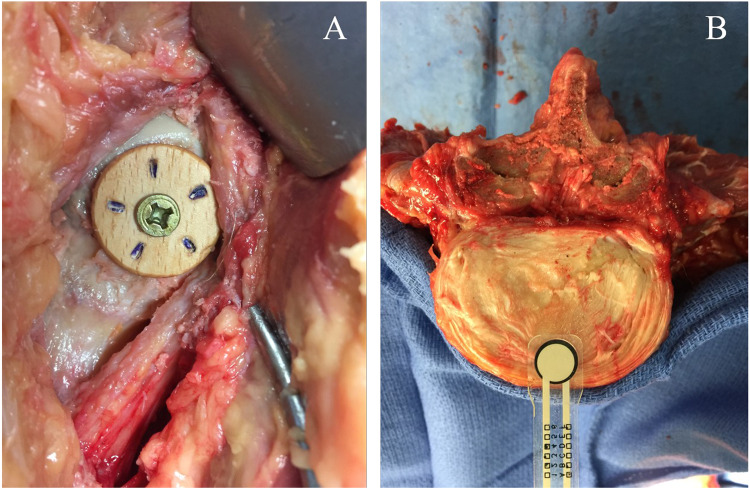

Fig. 4.

Simulated cam-type femoroacetabular impingement. (A) Anterior view of the right hip of a cadaveric specimen demonstrating simulated cam-type femoroacetabular impingement, utilizing a wooden knob placed at the femoral head-neck transition. (B) Piezoresistive force sensors placed in the antero-medial section of a lumbar intervertebral disk.

FEMORAL TORSION AND LIGAMENTOUS FUNCTION

Femoral torsion (FT) is the axial orientation of the femoral neck in relation to the horizontal axis of the posterior femoral condyles [46–48]. Abnormal FT is traditionally classified as increased femoral torsion (>20°) or decreased femoral torsion (<15°) [47]. The cutoff values reported by Tönnis and Heinecke [47] are not unanimous among different authors. The main reason for the lack of broadly accepted values for normal femoral torsion is the utilization of multiple methods to measure femoral torsion among the authors [49–51]. Increasing values for femoral torsion are observed by measuring the femoral neck orientation more distally, and differences of 10° or more among the methods are particularly frequent in patients with excessive femoral torsion [49].

Patients with abnormal FT may complain of hip pain and display abnormal gait as a result of the rotational misalignment of the lower extremities. Abnormal FT affects the capsulolabral and musculotendinous structures of the hip and lumbar spine, and may contribute to increased lumbopelvic pain. Abnormal FT may also be observed following total hip arthroplasty, potentially resulting in hip–spine–pelvis-CORE symptoms (Fig. 5).

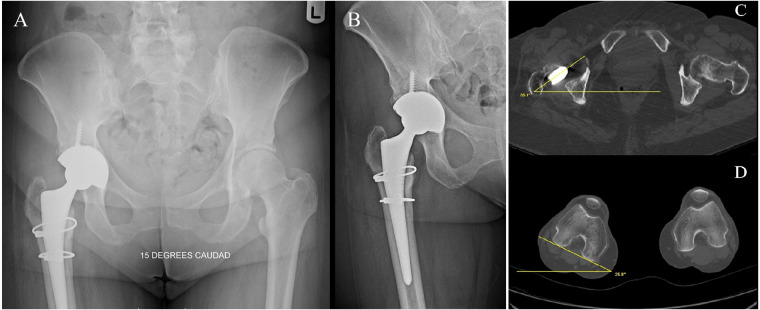

Fig. 5.

Patient presenting with hip–spine syndrome following inadequate positioning of femoral component in a revision hip arthroplasty of the right hip. The femoral component is in excessive antetorsion of 61°. (A) Anteroposterior pelvis radiograph. (B) Anteroposterior right hip radiograph. (C) Axial CT demonstrating anterior orientation of the femoral neck at 35.1°. (D) Axial CT at the posterior femoral condyle level demonstrating 25.8° of internal rotation.

The effect of abnormal FT and the iliofemoral ligament on lumbar spine biomechanics was investigated by Khoury et al. in a cadaveric model [52]. Increased FT (+30°) and decreased FT (−10°) models were developed to investigate lumbar facet joint loading during hip extension (Fig. 6). Increased FT resulted in the largest mechanotransduction to the facet joints. Iliofemoral ligament release in the −10 degrees FT state resulted in a 245.7% decrease in L3–L4 loading and 257.3% decrease in L4–L5 loading in the facet joints. The facet joint loading trends were also observed in finite element experiments, suggesting a critical contribution of the capsular ligaments to the understanding of the secondary effects of abnormal FT on the lumbar spine.

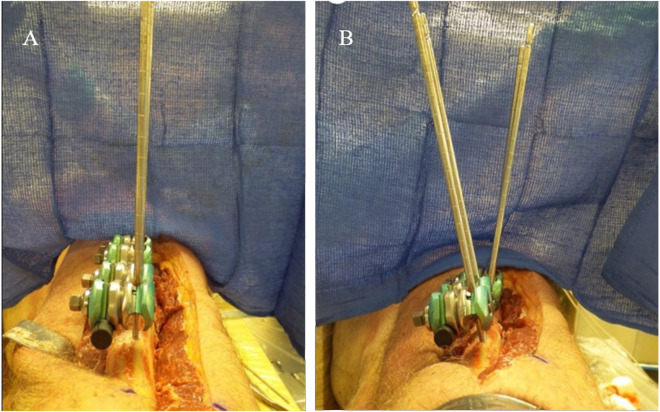

Fig. 6.

Simulated abnormal femoral torsion (FT) in a cadaveric model. (A) An external fixator was placed distal to the lesser trochanter and a transverse femoral osteotomy was performed. (B) The limb segment distal to the osteotomy was internally and externally rotated to achieve, respectively, the intended +30° of FT or −10° of decreased FT.

The hip capsular ligaments function to restrict internal rotation, followed by extension, abduction, and finally external rotation [53]. The presence of abnormal FT amplifies the capsular restrictions to hip extension and internal rotation of the leg. Lumbar spine rotation may be a compensatory mechanism during the gait cycle resulting from these restrictions in patients with decreased FT. Schröder et al. utilized gait analysis to compare individuals with decreased FT to individuals with normal FT [54]. Decrease in terminal hip extension and increase in pelvic tilt was observed in individuals with decreased FT throughout the gait cycle. Additionally, L5 markers demonstrated increased contralateral rotation during the gait cycle. Increased and decreased FT are recognized through the combination of physical examination maneuvers, including: gait, hip rotation range of motion in the seated position, hip spine extension test [55] and the prone femoral anteversion test (Craig’s test). Physical examination findings should be correlated with standardized Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or Computed tomography (CT) axial assessment. Restoration of hip range of motion through proximal femoral derotation osteotomy has the potential to improve the lumbar spine function in individuals with increased or decreased FT. Improvement of the lumbar function above the minimum clinically important difference for lumbar fusion has been reported in 64% of the individuals with low back pain following proximal femoral derotation osteotomy [56].

DISCUSSION

The present manuscript introduces the rationale linking low back pain to ischiofemoral impingement, femoroacetabular impingement and abnormal femoral torsion. The understanding of the link between hip abnormalities and low back pain is still evolving, and other conditions limiting hip mobility should be considered in the differential diagnosis of hip–spine syndrome. In order to classify the hip abnormalities causing low back pain based on the biomechanics, the authors propose a unique categorization of flexion, extension, combined types of hip–spine effect (Table I).

Table I.

Hip abnormalities leading to hip–spine syndrome classified according to the biomechanics

|

|

|

The dynamic relationship between the lesser trochanter and the ischium should be considered in a clinical scenario. The distance between the lesser trochanter and the ischium decreases in the terminal stance of the single support phase in comparison to the double support phase [22]. This decrease is amplified in individuals with abductor weakness, representing the dynamic ischiofemoral impingement [57]. In addition, the ischiofemoral space is decreased in the longer side of individuals with leg length inequality. The dynamic relationship between the lesser trochanter and ischium demands a critical interpretation of static imaging studies used to measure the ischiofemoral space. The positioning of the patient when acquiring the magnetic resonance studies should aim to reproduce the lower limb positioning during the gait. The physical examination is fundamental to dynamically test the relationship between the lesser trochanter and ischium [55, 58, 59].

The limitation in hip extension in individuals with increased femoral torsion is caused by contact between the femoral neck and acetabulum, or between the lesser trochanter and ischium [60]. The mechanism by which decreased femoral torsion limits hip extension is not well understood. The ligamentous structures are the likely responsible for limiting hip extension in individuals with decreased femoral torsion [56]. When the hip is extended and in neutral rotation/abduction, the femoral head is protuberant posteriorly in patients with decreased femoral torsion, tightening the ischiofemoral ligament, which runs from the posterior acetabular margin to insert more proximal and anteriorly to the femoral neck axis and zona orbicularis. In patients with decreased femoral torsion, the tension in the ischiofemoral ligament decreases by externally rotating the hip. This mechanism may explain the increased hip extension by adding external rotation in individuals with decreased femoral torsion. The migration of the medial arm of the iliofemoral ligament superolaterally to the femoral head may also play a role on allowing further extension of the hip with external rotation in patients with decreased femoral torsion. This effect would depend on the degree of hip abduction, the femoral neck shaft angle, and on the relationship between the origin and insertion of the medial arm of the iliofemoral ligament in the coronal plane. Hips with decreased femoral torsion may not present limitation in extension due to lax pubofemoral, iliofemoral and ischiofemoral ligaments. Therefore, the femoral torsion and ligamentous structures have a complex and close relationship to influence the hip extension [56]. The authors of the present manuscript utilize the head–neck superimposition method of Reikeråls to measure the FT in axial magnetic resonance image [61]. Utilizing Reikeråls’ method, we consider clinically significant decreased FT as <5° for males and <10° for females, and clinically significant increased FT for both males and females as >25°. These numbers must not be interpreted alone, as compensation or reinforcement of the abnormal mechanics can be observed according to the femoral morphology, acetabular morphology and ligamentous flexibility.

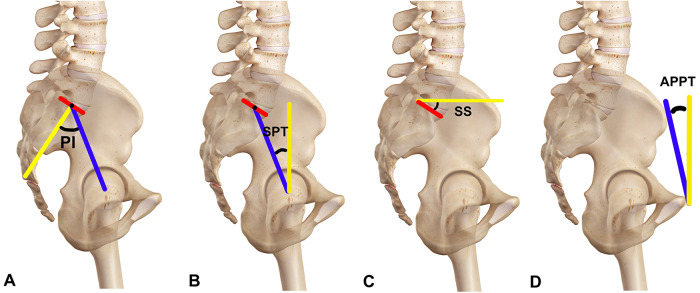

Bony abnormalities affecting the mechanotransduction of load through the spine do so by influencing pelvic planes. The sagittal orientation of the pelvis and lumbar spine are related, and three radiological parameters are utilized to assess the sagittal spinopelvic balance: pelvic incidence, spinopelvic tilt [62] and sacral slope [63] (Fig. 7A–C). The pelvic incidence is the sum of two complementary angles: pelvic tilt and sacral slope [62]. Pelvic incidence, which is the sum of pelvic tilt and sacral slope, is a constant value for any given patient: when the pelvic tilt increases, the sacral slope decreases, and when the pelvic tilt decreases, the sacral slope increases [64]. Changing from a supine or standing position to a sitting position decreases the sacral slope and increases the spinopelvic tilt in about 50% and 200%, respectively [65, 66]. The spinopelvic tilt and anterior pelvic plane tilt have different meanings, however, these terms have been used interchangeably [67, 68] (Fig. 7D). The sagittal orientation of the pelvis can also affect the ischiofemoral space. Figure 8 depicts an induced IFI associated to increased pelvic tilt secondary to lumbar spine deformity. The reduction of sacral slope and increase in pelvic tilt shifts the ischial tuberosity anteriorly, therefore narrowing the space between the ischium and lesser trochanter.

Fig. 7.

Spinopelvic parameters. (A) Pelvic incidence (PI) is represented by the angle between the perpendicular (yellow line) to the sacral plate at its midpoint, and the line (blue line) connecting this point to the bicoxofemoral axis. (B) Spinopelvic tilt (SPT) is represented by the angle between the vertical line (yellow line) and the line joining the middle of the sacral plate and the bicoxofemoral axis. (C) Sacral slope (SS) is represented by the angle between a horizontal line (yellow line) and a line tangent to the superior endplate of S1 (red line). (D) Anterior pelvic plane tilt (APPT) is the angle between the plane created by the bilateral anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic symphysis (blue line) and the coronal plane (yellow line).

Fig. 8.

Ischiofemoral impingement in association with lumbar spine deformity. (A and B) Illustration demonstrating the influence of pelvic tilt (blue line) on the ischiofemoral space (red line). (C) Sagittal computed tomography of the lumbo-sacral spine demonstrating the verticalization of the sacrum with decreased sacral slope (SS), secondary to L5–S1 spondylolisthesis. (D) Axial magnetic resonance imaging of the patient presented in figure C, demonstrating decreased ischiofemoral space associated with the anteriorization of the ischial tuberosity.

Assessment of the entire lumbopelvic complex is essential for diagnosing the primary hip abnormality producing low back and pelvic complaints. Diagnosis begins with a comprehensive clinical assessment including dedicated hip and spine functional scoring. The physical examination must include gait evaluation, hip internal and external rotation in the sitting position, and the hip–spine extension and flexion test. The clinical findings must be supported by three-planar imaging assessment.

In summary, evaluation of the anatomy and biomechanics through clinical, functional and imaging assessments is essential for successful non-operative and surgical treatment of hip pathologies causing secondary lumbar complaint. The future of hip–spine–pelvis-core pathology management requires the implementation of a global hip and spine approach to improve patient function and satisfaction.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

H.D.M. has received research support and faculty/speaking fees from Smith & Nephew.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shmagel A, Foley R, Ibrahim H.. Epidemiology of chronic low back pain in US adults: data from the 2009–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Care Res 2016; 68: 1688–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martin BI, Deyo RA, Mirza SK. et al. Expenditures and health status among adults with back and neck problems. JAMA 2008; 299: 656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Offierski CMM, MacNab I.. Hip-spine syndrome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1983; 8: 316–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bohannon RW, Bass A.. Research describing pelvifemoral rhythm: a systematic review. J Phys Ther Sci 2017; 29: 2039–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fogel GR, Esses SI.. Hip spine syndrome: management of coexisting radiculopathy and arthritis of the lower extremity. Spine J 2003; 3:238–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matsuyama Y, Hasegawa Y, Yoshihara H. et al. Hip-spine syndrome: total sagittal alignment of the spine and clinical symptoms in patients with bilateral congenital hip dislocation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004; 29: 2432–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rivière C, Lazennec J-Y, Van Der Straeten C. et al. The influence of spine-hip relations on total hip replacement: a systematic review. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2017; 103: 559–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lazennec JY, Brusson A, Folinais D. et al. Measuring extension of the lumbar–pelvic–femoral complex with the EOS® system. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2015; 25: 1061–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mellin G. Correlations of hip mobility with degree of back pain and lumbar spinal mobility in chronic low-back pain patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1988; 13: 668–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ellison JB, Rose SJ, Sahrmann SA.. Patterns of hip rotation range of motion: a comparison between healthy subjects and patients with low back pain. Phys Ther 1990; 70: 537–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cibulka MT, Sinacore DR, Cromer GS. et al. Unilateral hip rotation range of motion asymmetry in patients with sacroiliac joint regional pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998; 23: 1009–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vad VB, Bhat AL, Basrai D. et al. Low back pain in professional golfers: the role of associated hip and low back range-of-motion deficits. Am J Sports Med 2004; 32: 494–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ben-Galim P, Ben-Galim T, Rand N. et al. Hip-spine syndrome: the effect of total hip replacement surgery on low back pain in severe osteoarthritis of the hip. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007; 32: 2099–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parvizi J, Pour AE, Hillibrand A. et al. Back pain and total hip arthroplasty: a prospective natural history study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468: 1325–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Staibano P, Winemaker M, Petruccelli D. et al. Total joint arthroplasty and preoperative low back pain. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29: 867–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chimenti PC, Drinkwater CJ, Li W. et al. factors associated with early improvement in low back pain after total hip arthroplasty: a multi-center prospective cohort analyses. J Arthroplasty 2016; 31: 176–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Piazzolla A, Solarino G, Bizzoca D. et al. Spinopelvic parameter changes and low back pain improvement due to femoral neck anteversion in patients with severe unilateral primary hip osteoarthritis undergoing total hip replacement. Eur Spine J 2018; 27: 125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weng W, Wu H, Wu M. et al. The effect of total hip arthroplasty on sagittal spinal–pelvic–leg alignment and low back pain in patients with severe hip osteoarthritis. Eur Spine J 2016; 25: 3608–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schröder RG, Reddy M, Hatem MA. et al. A MRI study of the lesser trochanteric version and its relationship to proximal femoral osseous anatomy. J Hip Preserv Surg 2015; 2: 410–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Torriani M, Souto SCL, Thomas BJ. et al. Ischiofemoral impingement syndrome: an entity with hip pain and abnormalities of the quadratus femoris muscle. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009; 193: 186–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Atkins PR, Fiorentino NM, Aoki SK. et al. In vivo measurements of the ischiofemoral space in recreationally active participants during dynamic activities: a high-speed dual fluoroscopy study. Am J Sports Med 2017; 45: 2901–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gómez-Hoyos J, Khoury A, Schröder R. et al. The hip-spine effect: a biomechanical study of ischiofemoral impingement effect on lumbar facet joints. Arthroscopy 2017; 33: 101–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Birmingham P, Kelly B, Jacobs R. et al. The effect of femoroacetabular impingement on sacroiliac joint motion. Arthroscopy 2012; 28: e47–e48. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M. et al. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003; 417: 112–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Packer JD, Safran MR.. The etiology of primary femoroacetabular impingement: genetics or acquired deformity? J Hip Preserv Surg 2015; 2: 249–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Feingold JD, Heaps B, Turcan S. et al. A history of spine surgery predicts a poor outcome after hip arthroscopy. J Hip Preserv Surg 2019; 6: 227–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moley PJ, Gribbin CK, Vargas E. et al. Co-diagnoses of spondylolysis and femoroacetabular impingement: a case series of adolescent athletes. J Hip Preserv Surg 2018; 5: 393–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bedi A, Dolan M, Leunig M. et al. Static and dynamic mechanical causes of hip pain. Arthroscopy 2011; 27: 235–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hammoud S, Bedi A, Magennis E. et al. High incidence of athletic pubalgia symptoms in professional athletes with symptomatic femoroacetabular impingement. Arthroscopy 2012; 28: 1388–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kubiak-Langer M, Tannast M, Murphy SB. et al. Range of motion in anterior femoroacetabular impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007; 458: 117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lamontagne M, Kennedy MJ, Beaulé PE.. The effect of cam FAI on hip and pelvic motion during maximum squat. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467: 645–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Birmingham PM, Kelly BT, Jacobs R. et al. The effect of dynamic femoroacetabular impingement on pubic symphysis motion: a cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med 2012; 40: 1113–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim SH, Kwon OY, Yi CH. et al. Lumbopelvic motion during seated hip flexion in subjects with low-back pain accompanying limited hip flexion. Eur Spine J 2014; 23: 142–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fader RR, Tao MA, Gaudiani MA. et al. The role of lumbar lordosis and pelvic sagittal balance in femoroacetabular impingement. Bone Jt J 2018; 100-B: 1275–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weinberg DS, Gebhart JJ, Liu RW. et al. Radiographic signs of femoroacetabular impingement are associated with decreased pelvic incidence. Arthroscopy 2016; 32: 806–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gebhart JJ, Streit JJ, Bedi A. et al. Correlation of pelvic incidence with cam and pincer lesions. Am J Sports Med 2014; 42: 2649–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Prather H, Cheng A, Steger-May K. et al. Association of hip radiograph findings with pain and function in patients presenting with low back pain. Pm&R 2018; 10:11–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Verrall GM, Slavotinek JP, Barnes PG. et al. Hip joint range of motion restriction precedes athletic chronic groin injury. J Sci Med Sport 2007; 10: 463–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roach SM, San Juan JG, Suprak DN. et al. Passive hip range of motion is reduced in active subjects with chronic low back pain compared to controls. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2015; 10: 13–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim S-B, You JSH, Kwon O-Y. et al. Lumbopelvic kinematic characteristics of golfers with limited hip rotation. Am J Sports Med 2015; 43: 113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee RY, Wong TK.. Relationship between the movements of the lumbar spine and hip. Hum Mov Sci 2002; 21: 481–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Esola MA, McClure PW, Fitzgerald GK. et al. Analysis of lumbar spine and hip motion during forward bending in subjects with and without a history of low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996; 21:71–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sung PS. A compensation of angular displacements of the hip joints and lumbosacral spine between subjects with and without idiopathic low back pain during squatting. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2013; 23: 741–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gebhart JJ, Weinberg DS, Conry KT. et al. Hip-spine syndrome: is there an association between markers for cam deformity and osteoarthritis of the lumbar spine? Arthroscopy 2016; 32: 2243–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Khoury A, Gomez-Hoyos J, Yeramaneni S. et al. Biomechanical effect of anterior hip impingement on lumbar intradiscal pressure. J Orthop Res 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Miller F, Merlo M, Liang Y. et al. Femoral version and neck shaft angle. J Pediatr Orthop 1993; 12: 382–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tönnis D, Heinecke A, BY D. et al. Acetabular and femoral anteversion: relationship with osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Jt Surg 1999; 81: 1747–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khoury A, Gómez-Hoyos J, Martin and HD. Hip-spine effect: hip pathology contributing to lower back, posterior hip, and pelvic pain. In: Posterior Hip Disorders. Springer. 2018, 29-40 et al. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schmaranzer F, Lerch TD, Siebenrock KA. et al. Differences in femoral torsion among various measurement methods increase in hips with excessive femoral torsion. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2019; 477: 1073–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kaiser P, Attal R, Kammerer M. et al. Significant differences in femoral torsion values depending on the CT measurement technique. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2016; 136: 1259–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sugano N, Noble PC, Kamaric E.. A comparison of alternative methods of measuring femoral anteversion. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1998; 22: 610–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Khoury AN, Gomez-Hoyos J, Martin HD.. Hip-spine effect: hip pathology contributing to lower back, posterior hip and pelvic pain. In: Martin HD, Gomez-Hoyos J (eds). Posterior Hip Disorders: Clinical Evaluation and Management, 1st edn. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Martin HD, Savage A, Braly BA. et al. The function of the hip capsular ligaments: a quantitative report. Arthroscopy 2008; 24: 188–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schröder R, Gomez-Hoyos J, Martin R. et al. The influence of decreased femoral anteversion on pelvic and lumbar spine kinematics during gait. J Orthop Sports Med 2016; 180: A134. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hatem M, Martin HD, Safran MR. Snapping of the sciatic nerve and sciatica provoked by impingement between the greater trochanter and ischium: a case report. JBJS Case Connect 2020; 10: e2000014 et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hatem M, Khoury AN, Erickson L. et al. Femoral derotation osteotomy improves hip and spine function in patients with increased or decreased femoral torsion. Arthroscopy, in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. DiSciullo AA, Stelzer JW, Martin SD.. Dynamic ischiofemoral impingement: case-based evidence of progressive pathophysiology from hip abductor insufficiency: a report of two cases. JBJS Case Connect 2018; 8: e107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hatem MA, Palmer IJ, Martin HD.. Diagnosis and 2-year outcomes of endoscopic treatment for ischiofemoral impingement. Arthroscopy 2015; 31: 239–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gómez-Hoyos J, Martin RL, Schröder R. et al. Accuracy of 2 clinical tests for ischiofemoral impingement in patients with posterior hip pain and endoscopically confirmed diagnosis. Arthroscopy 2016; 32: 1279–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Morris WZ, Fowers CA, Weinberg DS. et al. Hip morphology predicts posterior hip impingement in a cadaveric model. HIP Int 2019; 29: 322–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Reikeråls O, Bjerkreim I, Kolbenstvedt A.. Anteversion of the acetabulum and femoral neck in normals and in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip. Acta Orthop Scand 1983; 54: 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Legaye J, Duval-Beaupère G, Marty C, Hecquet J.. Pelvic incidence: a fundamental pelvic parameter for three-dimensional regulation of spinal sagittal curves. Eur Spine J 1998; 7: 99–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vialle R, Levassor N, Rillardon L.. Radiographic analysis of the sagittal alignment and balance of the spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Jt Surg 2005; 87-A: 260–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Huec JC, Aunoble S, Philippe L. et al. Pelvic parameters: origin and significance. Eur Spine J 2011; 20: 564–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Endo K, Suzuki H, Nishimura H. et al. Sagittal lumbar and pelvic alignment in the standing and sitting positions. J Orthop Sci 2012; 17: 682–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Loppini M, Longo UG, Ragucci P. et al. analysis of the pelvic functional orientation in the sagittal plane: a radiographic study with EOS 2D/3D technology. J Arthroplasty 2017; 32: 1027–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Feng JE, Anoushiravani AA, Eftekhary N. et al. Techniques for optimizing acetabular component positioning in total hip arthroplasty. JBJS Rev 2019; 7: e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Buckland A, DelSole E, George S. et al. Sagittal pelvic orientation a comparison of two methods of measurement. Bull Hosp Jt Dis 2017; 75: 234–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]