The burden of childhood illnesses has dramatically shifted from communicable to noncommunicable diseases in Peru, with a total estimated population of 32.5 million inhabitants, where cancer is estimated to develop in at least 1800 children and adolescents (0-19 years of age) each year.1 Up to 70% will present with advanced disease, often metastatic, due to delayed diagnoses. Consequently, nearly half of these patients die.2 In 2018, the WHO, together with St Jude Children's Research Hospital (St Jude) and the International Society of Pediatric Oncology, launched the Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer (GICC) with the aim to achieve at least a 60% global survival rate for children with cancer by 2030, and, together with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), Peru was designated as the first index country for the Region of the Americas.3

The first steps to improve the care of Peruvian children with cancer were taken in 2016 when Peruvian experts in childhood cancer reviewed the rates of treatment abandonment and delayed diagnoses, and described the poor conditions of care for children with cancer nationwide.2,4,5 Subsequently, in January 2017, Peruvian pediatric hematologists and oncologists jointly formed the national association for Hemato-Oncología Pediátrica del Peru (HOPPE) to improve conditions encountered by children with cancer through pediatric cancer training and research establishing a plan of action in the short and medium term.

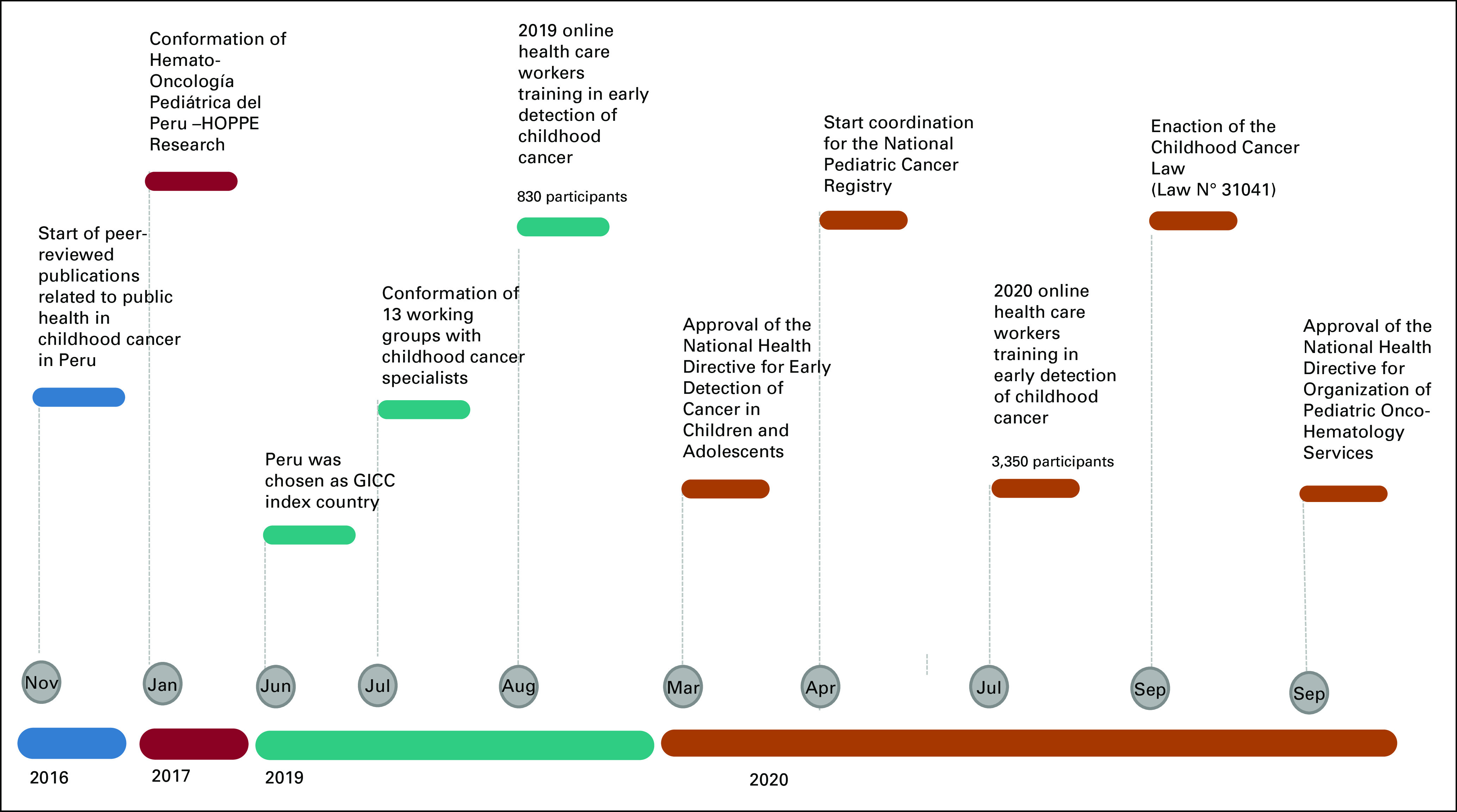

In June 2019, PAHO, St Jude, and the Ministry of Health of Peru convened the leading national stakeholders to launch the GICC in Lima. High-level authorities of the state ministries, social security of Peru (EsSalud), national hospitals, academic societies, international partners, and nonprofit organizations contributed to the GICC. Multidisciplinary GICC members formed 10 general working groups (ie, early diagnosis, abandonment, health services, professional education, registry, nursing, psychosocial, infection control, oncologic surgery, and palliative care) and three clinical groups (leukemia, retinoblastoma, and brain tumors, which are three of the six priority malignancies targeted by the WHO GICC to start with) assigned to develop clinical practice guidelines and strategic activities.6 These working groups generated two official documents approved by the Ministry of Health that have become the cornerstone for childhood cancer care in Peru: the National Health Directive for Early Detection of Cancer in Children and Adolescents and the National Health Directive for the organization of pediatric hematology and oncology services (Fig 1).7,8

FIG 1.

Milestones of the WHO Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer in Peru. HOPPE, Hemato-Oncología Pediátrica del Peru; GICC, Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer.

Despite these advances, the COVID-19 pandemic has posed significant challenges to sustain the working groups and their activities, but it has also created an opportunity to develop legislation for childhood cancer services. During the COVID-19 pandemic, a survey published by the PAHO and Latin American Society for Pediatric Oncology described the experiences and opinions of childhood cancer specialists from cancer centers throughout Latin America, including Peru. The survey revealed that many services (30%-80%) such as radiotherapy and surgeries were suspended because of the pandemic. Moreover, potentially harmful chemotherapy modifications (35%) were implemented because of difficulties in acquiring medications.9 Nevertheless, the pandemic increased the visibility of the disparity of childhood cancer deaths in Peru, leading the Peruvian legislature to propose the Childhood Cancer Law in April 2020. On September 2, 2020, President Martin Vizcarra and the Peruvian Parliament enacted the Childhood Cancer Law.10 This represents an important step for the country, recognizing for the first time the importance of cancer in children as a public health priority in Peru.

The Childhood Cancer Law has three primary objectives: (1) universal health coverage for early diagnoses and cancer-related treatments for all children and adolescents, (2) paid parental leave for caregivers of children and adolescents with cancer (a bonus equivalent of two minimum-wage salaries is to be granted to unemployed parents) while their child is hospitalized for treatment, and (3) creation of the National Program for Cancer in Children and Adolescents and a national pediatric cancer registry.5

During the Childhood Cancer Law proposal process, a social movement called the Colectivo Cancer Infantil YA or Childhood Cancer Law NOW was born. This movement was championed chiefly by pediatric oncologists and parents of children with cancer. Among the achievements of the movement was the formation of a cohesive group of health professionals, volunteers, and parents (up to 150). This group harnessed the power of social networks, newspapers, television, radio, and other media to disseminate their message. PAHO has given its full support and provided advocacy for this purpose.11 Finally, several stakeholders fully supported the Childhood Cancer Law through written and/or public statements. These stakeholders included the state ministries, EsSalud, physicians, politicians, foundations, and international partners (primarily St Jude and the Latin American Society for Pediatric Oncology).

The estimated impact of the law is vast. It aims to save at least 650 lives per year, summing up to 169,000 healthy life years for children who receive successful treatment and survive to adulthood in Peru, and to prevent avoidable suffering among children and their families. Therefore, the Childhood Cancer Law will have great impact in the fight against childhood cancer in Peru, despite a global pandemic. This childhood cancer law is an example of successful collaboration of different stakeholders and can serve as a model for other countries as they become part of the GICC.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Liliana Vasquez, Jacqueline Montoya, Cecilia Ugaz, Claudia Pascual, Edinho Celis, Jonathan Rossi, Vivian Perez, Monika L. Metzger, Silvana Luciani

Financial support: Liliana Vasquez, Edinho Celis

Administrative support: Liliana Vasquez, Cecilia Ugaz, Edinho Celis, Vivian Perez

Provision of study materials or patients: Liliana Vasquez, Edinho Celis, Jonathan Rossi, Lily Saldaña

Collection and assembly of data: Liliana Vasquez, Essy Maradiegue, Ninoska Rojas, Arturo Zapata, Cecilia Ugaz, Claudia Pascual, Carlos Santillán, Edinho Celis, Hernan Bernedo, Lily Saldaña, Rosdali Diaz, Roxana Morales

Data analysis and interpretation: Liliana Vasquez, Essy Maradiegue, Cecilia Ugaz, Claudia Pascual, Antonio Wachtel, Edinho Celis, Hernan Bernedo, Rosdali Diaz, Silvana Luciani

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Liliana Vasquez, Essy Maradiegue, Ninoska Rojas, Jacqueline Montoya, Arturo Zapata, Cecilia Ugaz, Claudia Pascual, Carlos Santillán, Antonio Wachtel, Edinho Celis, Hernan Bernedo, Jonathan Rossi, Lily Saldaña, Rosdali Diaz, Roxana Morales, Vivian Perez, Monika L. Metzger, Silvana Luciani

Rosdali Diaz

Honoraria: Merck Sharp & Dohme

Monika L. Metzger

Research Funding: Seattle Genetics

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. : Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68:394-424, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasquez L, Oscanoa M, Tello M, et al. : Factors associated with the latency to diagnosis of childhood cancer in Peru. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63:1959-1965, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization : https://www.who.int/cancer/childhood-cancer/en/

- 4.Vasquez L, Diaz R, Chavez S, et al. : Factors associated with abandonment of therapy by children diagnosed with solid tumors in Peru. Pediatr Blood Cancer 65:e27007, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasquez L, Silva J, Chavez S, et al. : Prognostic impact of diagnostic and treatment delays in children with osteosarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 67:e28180, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Organización Panamericana de la Salud : Iniciativa Mundial para el Cáncer Infantil de la OMS en Perú. https://www.paho.org/es/iniciativa-mundial-para-cancer-infantil-oms-peru [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gobierno del Perú : Resolución Ministerial N° 149-2020-MINSA. https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/normas-legales/466089-149-2020-minsa [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gobierno del Perú : Resolución Ministerial N° 802-2020-MINSA. https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/normas-legales/1240029-802-2020-minsa [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasquez L, Sampor C, Villanueva G, et al. : Early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on paediatric cancer care in Latin America. Lancet Oncol 21:753-755, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Normas Legales : ley-de-urgencia-medica-para-la-deteccion-oportuna-y-atencion-ley-n-31041-1881519-1. https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/download/url/ley-de-urgencia-medica-para-la-deteccion-oportuna-y-atencion-ley-n-31041-1881519-1#:∼:text=La%20presente%20ley%20tiene%20por,abandono%20de%20tratamiento%20y%20morbimortalidad [Google Scholar]

- 11.Organización Panamericana de la Salud : Ley de Cáncer Infantil en Perú: una historia de impacto positivo de la Iniciativa Global de Cáncer Infantil—OPS/OMS. https://www.paho.org/es/noticias/10-9-2020-ley-cancer-infantil-peru-historia-impacto-positivo-iniciativa-global-cancer [Google Scholar]