Abstract

Objectives:

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the Function Focused Care for Assisted Living Using the Evidence Integration Triangle (FFC-AL-EIT) intervention.

Design:

FFC-AL-EIT was a randomized controlled pragmatic trial including 85 sites and 794 residents.

Intervention:

FFC-AL-EIT was implemented by a Research Nurse Facilitator working with a facility champion and stakeholder team for 12 months to increase function and physical activity among residents. FFC-AL-EIT included: (Step I) Environment and Policy Assessments; (Step II) Edusscation; (Step III) Establishing Resident Function Focused Care Service Plans; and (Step IV) Mentoring and Motivating.

Setting and Participants:

The age of participants was 89.48 (SD=7.43), the majority was female (N=561, 71%) and white (N=771, 97%).

Methods:

Resident measures, obtained at baseline, four and 12 months, included function, physical activity, and performance of function focused care. Setting outcomes, obtained at baseline and 12 months, included environment and policy assessments and service plans.

Results:

Reach was based on 85 of 90 sites that volunteered (94%) participating. Effectiveness was based on less decline in function (p<.001), more function focused care (p=.012) and better environment (p=.032) and policy (p=.003) support for function focused care in treatment sites. Adoption was supported with 10.00 (SD=2.00) monthly meetings held, 77% of settings engaged in study activities as or more than expected, and direct care workers providing function focused care (63% to 68% at 4 months and 90% at 12 months). The intervention was implemented as intended and education was received based on a mean knowledge test score of 88% correct. Evidence of maintenance from 12 to 18 months was noted in treatment site environments (p=.35) and policies continuing to support function focused care (p=.28)].

Conclusions and Implications:

The Evidence Integration Triangle is an effective implementation approach for assisted living. Future work should continue to consider innovative approaches for measuring RE-AIM outcomes.

Keywords: Function, Physical Activity, Implementation, Assisted Living

Summary:

Implementation of Function Focused Care was facilitated by use of the Evidence Integration Triangle with regard to Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance.

Residents in assisted living settings engage in limited amounts of physical activity 1–3 and decline functionally more rapidly than their peers in nursing homes 4. At the resident level factors that influence function include cognition, comorbidities, motivation, self-efficacy, fear of falling, pain and mood 5–7. At the setting level, size, ownership (profit versus not-for-profit), policies, philosophy and culture of care, staffing ratios, staff turnover, and physical environment can influence physical activity among residents 1–3.

To address the persistent functional decline and increased time spent in sedentary activity among assisted living residents, Function Focused Care was developed. Function Focused Care is a philosophy of care that involves teaching direct care workers to evaluate older adults’ underlying capability with regard to function and physical activity and optimize their participation in all activities 8. Examples of function focused care include: modeling behavior for residents (e.g.,oral care, bathing); providing verbal cues during dressing; walking a resident to the dining room rather than transporting via wheelchair; doing resistance exercises with residents prior to meals; and/or providing recreational physical activity (e.g., Physical Activity Bingo). Benefits include improving or maintaining function and increasing physical activity 8–10, improving mood and decreasing behavioral symptoms associated with dementia 11,12.

Dissemination and Implementation of Function Focused Care

Changing care behavior among staff is challenging in any long term care setting 13,14. To optimize dissemination and implementation of Function Focused Care a theoretically based implementation strategy, Function Focused Care for Assisted Living Using the Evidence Integration Triangle (FFC-AL-EIT), was developed. FFC-AL-EIT combines the social ecological model15, social cognitive theory16 and the Evidence Integration Triangle17,18. The social ecological model includes intrapersonal (e.g., physical capability), interpersonal (e.g., direct care worker and resident interactions), environmental (e.g., clear pathways for walking), and policy factors (e.g., falls policies that encourage physical activity) that influence behavior related to function. Social cognitive theory guides the interpersonal interactions that motivate direct care workers and residents to engage in function focused care 19–21. Lastly, the Evidence Integration Triangle was used to facilitate systemic implementation of function focused care 17,18. The Evidence Integration Triangle process begins and ends with engagement of local stakeholders and focuses on setting specific challenges and goals. In prior function focused care work a Research Nurse Facilitator worked with a staff nurse champion in the setting21. Guided by the Evidence Integration Triangle, stakeholders, defined as individuals that could affect or be affected by the intervention being implement (e.g., the assisted living manager, owner, director of nursing, delegating nurse, staff nurse, social worker, activities director, direct care worker), were included in FFC-AL-EIT to identify setting specific goals, provide positive reinforcement and support the staff implementing the intervention and/or intervene when champions or staff were not engaged in intervention activities. Ongoing participation of the stakeholder team occurred through monthly meetings. Practical progress measures were used focusing on setting level findings and resident level findings. The purpose of this study was to evaluate implementation of function focused care into assisted living using the FFC-AL-EIT intervention. Evaluation of implementation was based on the Reach Effectiveness Approach Implementation and Maintenance (RE-AIM) Model (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description and Findings for Reach Effectiveness Approach Implementation Maintenance Outcomes

| Construct | Definition and Outcome Evaluated | Results |

|---|---|---|

| REACH | The absolute number, proportion and representativeness of individuals who are willing to participate in a given initiative. | |

| Participation | Percentage of ALs that volunteered and participated in study activities; number of residents recruited per setting. | 300 sites invited, 90 volunteered (28%) 90 volunteered and 85 participated (94%) Mean of 10.00 residents (SD =2.00) recruited per setting. |

| EFFECTIVENESS | The impact of an intervention on outcomes. | |

| Facility Outcomes | Hypothesis: FFC-AL-EIT settings will demonstrate improvements in environment and policies supporting function focused care and service plans will reflect a greater number of function focused care activities at 12 months post-implementation compared to FFC-EO settings. | |

| Environmental modifications | Improvement in Environment Assessments. | Treatment group improved from a mean of 15.13 (SD=1.86) to 16.63 (SD=1.64) versus control which only increased from 15.06 (SD=2.79) to 15.90 (SD=1.58), p=.032. |

| Policy modifications | Improvement in Policy Assessments. | Treatment group improved from mean 9.44(SD=4.04) to 11.95 (SD=3.01), while control only increased from 10.18 (SD=3.66) to 11.95 (SD=2.92), p=.003. |

| Service plans | Increase in number of Function Focused Care approaches used in service plans. | No significant difference in Service Plans between groups over time (p=.102 at 4 months and p=.431 at 12 months). |

| Resident Outcomes | Hypothesis: Residents in FFC-AL-EIT settings will maintain, decline less, or improve function and physical activity compared to residents in settings exposed to FFC-AL-EO at 4 and 12 months post implementation of the intervention. | |

| Function and performance of function focused care by residents | The control group declined from baseline to 12 months from 82.60 (SD=22.40) to 73.60 (SD= 24.00) while the treatment group declined less from 80.20 (SD=21.20) at baseline to 78.10 (SD=22.50) at 12 months, p<.001. The treatment group residents increased function focused care behaviors from 77% (SD=17%) to 81% (SD=18%) while the control group decreased from 82% (SD=15%) to 81% (SD=16%), p=.012. At 12 months the treatment group remained at 81 %(SD=15%) while the control group declined to 79% (SD=18%), p = .001. |

|

| ADOPTION | The absolute number, proportion and representativeness of settings and intervention agents who are willing to initiate a program. | |

| Participation in the first stakeholder meeting. | Attendance at the face-to-face meeting | 85 out of 90 (94%) sites that volunteered participated in the first meeting. |

| Participation in the remaining 11 stakeholder meetings. | Meeting held with the stakeholder team | Mean of 10.00 (SD= 2.00) out of the 11 additional meetings held. |

| Goal Attainment | Evidence of participation/goal attainment as expected or more than expected. | 77% of sites achieved their goals as expected or more than expected. |

| The direct care workers implementation of function focused care. | Performance of function focused care by the direct care workers over the 12 month intervention period. | Function focused care was provided in 63% of interventions at baseline, 68% at four months and 90% at 12 months. |

| IMPLEMENTATION/ FIDELITY | ||

| The intervention fidelity to the various elements of the protocol. | ||

| Delivery of monthly stakeholder meetings | Evidence that the majority of the monthly stakeholder team meetings were provided to the 48 FFC-AL-EIT settings. | A mean of 11.00 (SD=2.13) meetings delivered. |

| Delivery of the four steps of FFC-AL-EIT | Completion of assessments of environment and policies; Education provided to nurses; Review and development of service plans for residents; and Motivation and mentoring of staff provided. | Completed based on field notes by Research Nurse Facilitator; postings on the functionfocusedcare.org webpage of Tidbits. |

| Receipt of Education | Based on a mean of 80% or greater correct on the Knowledge Test for Function Focused Care completed by staff attending education sessions. | Mean of 88% correct across both treatment and control groups. |

| MAINTENANCE | The extent to which the intervention becomes institutionalized or part of the routine organization practices and policies. | |

| Environment and Policy | Maintenance or improvement in Environments and Policies to optimize function focused care in the treatment groups at 18 months. | Maintenance of environment assessments with a mean at 12 months of 16.63 (SD=1.64) and a mean of 16.55 (SD=1.40) at 18 months (p=.35) and policy assessment was maintained with a mean of 11.95 (SD=3.01) at 12 months to 11.66 (SD=3.06) at 18 months (p=.28). |

Methods

Design

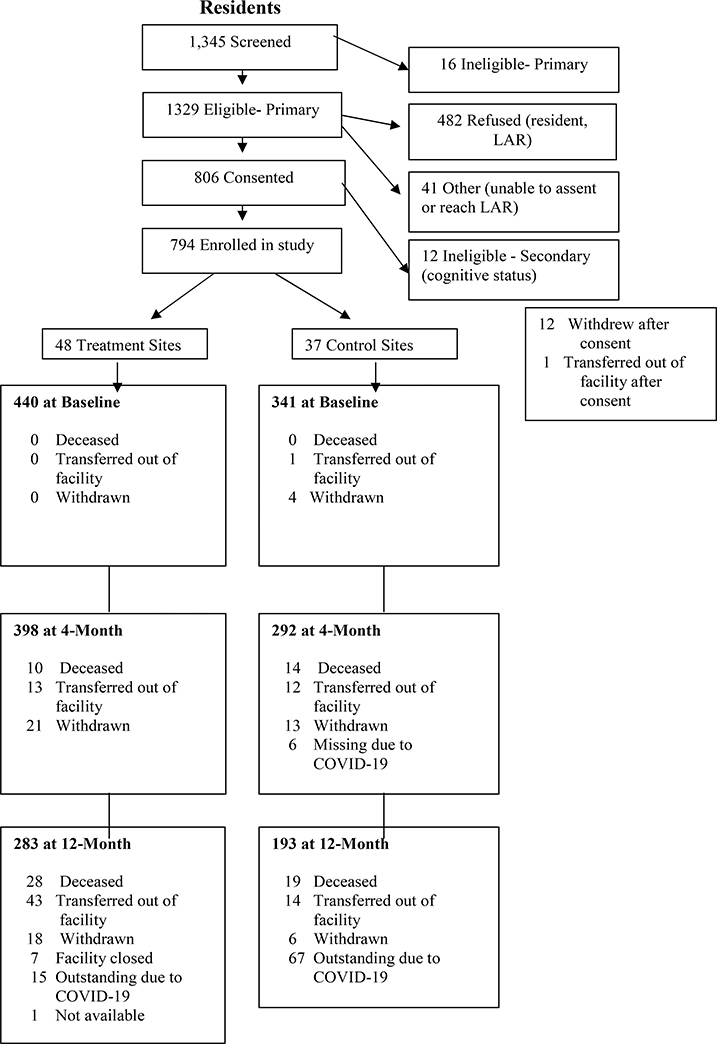

This was a randomized controlled pragmatic implementation trial. The study was approved by a University based Institutional Review Board and all participants (or the Legally Authorized Representative) provided written or verbal assent and/or consent to participate. A description of resident recruitment is provided in Appendix 1.

Implementation of FFC-AL-EIT

The goal of implementation was to reach 90 settings and enroll 10 residents per setting. Invitation letters were sent to 300 settings (100 per state), 90 (33%) expressed interest in participating and 85 (28%) actually participated (defined as participating in stakeholder meetings, staff education, and recruitment of residents). Resident recruitment averaged 9.34 (SD= 1.48) residents per setting.

FFC-AL-EIT is a four step approach that is implemented by a Research Nurse Facilitator working with a facility identified champion and stakeholder team for approximately two hours monthly for a total of 12 months. Table 2 provides an overview of the first stakeholder team meeting and description of the four step intervention. During this meeting an overview of the intervention is provided and the Research Nurse Facilitator uses a brainstorming approach to help the stakeholder team develop setting specific goals.

Table 2:

Descriptions of the Intervention Activities for FFC-AL-EIT

| Stakeholder Team Meeting (typically included: an administrator, resident services director, activities director and direct care worker). | a. Welcome and overview of the project. b. Roles and responsibilities of all members of the research team. c. Roles and responsibilities of the champion and stakeholder team. d. Overview of Function Focused Care: 1. Review of current care practices/philosophies of care; 2. Task focused versus resident outcome focused care; 3. Definition and description of function focused care; 4. Examples of function focused care interactions. e. Explanation of the Participatory Implementation and Evaluation Process; completion of Brainstorming activities (i.e., identification of challenges and solutions to implementation of FFC-AL-EIT, development of Affinity Diagrams and Interrelationship Diagraphs and identification of the best drivers for the implementation process). f. Establish goal(s) based on Brainstorming activity; g. Set regular time for monthly meetings. |

| Implementation of Step I Environment and Policy Assessments | Research Nurse Facilitator completes the Function Focused Environment Assessment and the Function Focused Policy Assessment in Assisted Living 22 with the nurse champion and provides examples of effective environmental interventions and policies to optimize function and physical activity relevant to the setting. Settings were provided with fifty dollars worth of activity resources for residents (e.g., horseshoe games; Activity Bingo). |

| Step II Education of Direct Care Workers |

Education of direct care workers, families and residents with standardized PowerPoint. Education timing and location is coordinated with the individual setting. |

| Step III Establishing Function Focused Care Service Plans for Residents | Working with the champions, the Research Nurse Facilitator teaches the champion and helps him or her to evaluate and match residents’ underlying physical capability and preferences with service plan goals. These are developed to engage the resident in function and physical activity rather than just state what the direct care workers will do for the residents (e.g., resident will complete upper body bathing). |

| Step IV Mentoring and Motivating; | The Research Nurse Facilitator works with the champion to implement techniques that motivate direct care workers, residents, and families to engage in function focused care activities. NASCO resources (up to a value of 50 dollars including such things as horseshoes; age appropriate weights) are provided to each setting to help engage residents in function and physical activity. In addition, the champions completed observations of direct care workers and resident care interactions to assure that function focused care activities were implemented. The direct care workers were provided with positive reinforcement and encouragement by champions related to implementation of function focused care. Use of contests within and between settings was encouraged as a way to engage residents in physical activity. For example, prizes were provided for innovative ways to engage residents in physical activity during a holiday. Lastly, weekly Tidbits were provided to all champions and stakeholder team members with innovative approaches to engage residents in physical activity (Tidbits available at www.functionfocusedcare.org) |

During Step I the Research Nurse Facilitator and the champion evaluated the environment and policies within the settings to consider how they supported implementing a function focused care philosophy or were barriers to this approach. Findings from these assessments were reviewed with the stakeholder team and changes discussed. Each site was given activity resources (fifty dollar value) to use with residents (e.g., ring toss; physical activity Bingo). Step II was the education of staff which was provided as per site preference with most sites preferring a traditional in-service approach. The same PowerPoint was used and is available at functionfocusedcare.org. All participants completed a paper and pencil multiple choice knowledge test following education to assure receipt of the information. Step III involved the Research Nurse Facilitator working with the champion and staff to show them how to evaluate residents’ for underlying capability and use that information to establish service plans that incorporated functional and physical activities (e.g., part of the service plan would be to remind the resident to go to daily exercise class). Practical ways to share service plans using snapshot approaches (available at Functionfocusedcare.org) were provided. Lastly, Step IV of implementation involved the ongoing and participatory implementation process between the champions, stakeholders and Research Nurse Facilitator to provide mentoring and motivating of the staff to provide function focused care (Table 2).

In addition to monthly meetings, to continually engage the stakeholders in the implementation process, weekly Tidbits (resources and strategies to increase physical activity among residents such as holiday activities that required physical activity and fun contests between units or sites) were provided via email and posted on the Functionfocusedcare.org webpage. Settings that were randomized to control were exposed to FFC-AL-Education Only which involved providing the same education as described in Step II (Table 2).

Measures

Based on study design Reach, as defined in RE-AIM, was not evaluated as we included a set number of sites and residents based on numbers needed to establish effectiveness. Rather Reach was considered by comparing the proposed goal of engaging 90 sites and 10 enrolled and eligible residents per site to actual numbers participating in the study.

Effectiveness was evaluated at the level of settings and residents. Setting level effectiveness considered the environment, policies and service plans. To evaluate the environment and policies, The Function Focused Environment Assessment and the Function Focused Policy Assessment in Assisted Living22 were completed by research evaluators at baseline, 12 and 18 months post implementation (18 months was only evaluated in treatment sites) of the intervention. Examples of environmental items include “evidence of an area for walking that is clear of clutter;” or “access to age appropriate exercise equipment”. The Function Focused Policy Assessment in Assisted Living is a 15 item measure that reflects policies that encourage function and physical activity among residents. Examples of policy items include “Evidence of policy related to use of free space (corridors, kitchens) that optimizes function and physical activity”, and “Evidence of policy associated with falls prevention that optimizes function and physical activity”. For both measures, items are scored as present or not present and a total score is summed. Prior testing provided reliability and validity of these measures 22.

The Evidence of Function Focused Care in the Service Plan checklist was used to determine if service plans, which all sites are required to have on every resident, included a function focused care approach. Four care activities were evaluated: Bathing, dressing, ambulation and physical activity. A score of present or not present was noted and scores ranged from 0–4. Testing of this measure provided evidence of inter-rater reliability and validity based on an association with functional performance 23.

All resident level effectiveness measures were completed by research evaluators at baseline, four and 12 months post implementation of the intervention. Descriptive information included age, gender, race, cognition, comorbidities, cognition based on a single item from the Mini-Cog which tested the residents’ ability to recall three out of three words24, comorbidities based on the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics 25 using a sum of the 13 organs or systems included in the measure. Function was evaluated with the Barthel Index 26, a 10 item measure that considers basic activities of daily living (e.g., bathing, dressing). The measure was completed based on input from the direct care worker providing care to the resident on the day of testing. The MotionWatch 8 was used as the objective measure of physical activity. Reliability and validity of this measure has been described in detail previously 27. The Function Focused Care Behavioral Checklist for Residents was used to evaluate the residents’ performance of function focused care activities during caregiver-resident interactions. This reliable and valid 19-item observation measure was completed over 15–30 minutes by a research evaluator who recorded whether or not the resident engaged in the care activity when encouraged to do so (e.g., walking to the bathroom) 28,29.

Adoption was considered based on the number and proportion of settings (stakeholder teams, champions and direct care workers) engaged in the intervention activities. Specifically this included: (1) participating in the first stakeholder meeting; (2) participating in the remaining 11 stakeholder meetings; (3) the level of participation (less than expected, as expected, or more than expected); and (4) the direct care workers implementation of function focused care with residents based on the Function Focused Care Behavior Checklist for Direct Care Workers30

Implementation was evaluated based on delivery of the stakeholder meetings, assessments of the environment and policies, education of direct care workers provided in treatment and control sites, champions taught to assess residents and develop service plans, and ongoing motivation and mentoring of staff and residents provided. Receipt or understanding of function focused care after education was based on mean scores of 80% or greater on the Knowledge of Function Focused Care, a 12-item multiple choice test31. Maintenance referred to the extent to which the intervention was incorporated into routine care and was based on evidence of maintenance or improvement in the environments and policies that helped optimize function focused care in treatment sites at 18 months.

Data Analysis

Descriptive information of facilities and residents were compared between intervention and control groups to check randomization. Descriptive statistics were done to describe RE-AIM outcomes and to check the assumptions of the models for hypothesis testing. Resident effectiveness outcomes were evaluated using linear mixed models (LMMs) to assess the intervention effects on continuous outcomes, accounting for clustering of residents within the same facility and for correlations between repeated measurements of each resident. A repeated measures analysis of variance was done to evaluate baseline to 12 month changes in environments and policies between treatment groups and maintenance of changes was evaluated between 12 and 18 months in treatment sites. A p< .05 was used for all analyses. All analyses were done following an intent-to-treat philosophy.

Results

RE-AIM results are shown in Table 1. With regard to Reach, from the 300 sites invited, 90 volunteered to participate and 85 (28% of those invited and 94% of those that volunteered) participated in the first stakeholder team meeting (48 randomized to treatment and 37 control). From these settings, as proposed, there was a mean recruitment rate of 10 (SD=2) residents per setting.

There was no difference between the sites in any of the descriptive measures. The mean number of residents per site was 70.78 (SD= 27.65), the majority were for profit (N=62, 73%) and the mean possible occupancy was 89.24 (SD=43.77, range 25–300). Effectiveness at the setting level (Table 3) was based on improvements in policy assessments supporting function focused care with the treatment group showing improvement from a baseline mean of 9.44 (SD=4.04) to a mean of 11.95 (SD=3.01) at 12 months versus control with a baseline mean of 10.18 (SD=3.66) that increased to 11.56 (SD=2.92) (p=.003). Environments supporting function focused care increased significantly in treatment versus control sites with a baseline treatment mean of 15.13 (SD=1.86) increasing to 16.63 (SD=1.64) at 12 months versus control with a baseline of 15.06 (SD=2.79) increasing to 15.90 (SD=1.58, p =.032). There was no significant difference between groups for service plans.

Table 3.

Facility Outcomes at Baseline, 4 and 12 months and Effectiveness Between Treatment (FFC-AL-EIT) and Control (FFC- AL-Education Only) over Time

| Outcomes | Baseline Mean (SD) | Month 4 Mean (SD) | Month 12 Mean (SD) | Month 18 Mean (SD) | Effects baseline to M4 (p-value) | Effects baseline to M12 (p-value) | Effects baseline to M18 (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment Assessment | - | .032 | .35 | ||||

| Control | 15.06(2.79) | - | 15.90(1.58) | - | - | ||

| Intervention | 15.13(1.86) | - | 16.63(1.64) | 16.55(1.40) | |||

| Policy Assessment | 0.003 | .28 | |||||

| Control | 10.18 (3.66) | - | 11.56 (1.86) | ||||

| Intervention | 9.44(4.04) | - | 11.95(3.01) | 11.66(3.06) | |||

| Service Plans | 102 | 0.413 | |||||

| Control | 2.16(1.59) | 1.93(1.62) | 2.55(1.47) | ||||

| Intervention | 1.91(1.65) | 1.86(1.55) | 2.06(1.59) |

A description of the resident sample used to evaluate effectiveness is provided in Table 4. The mean age of participants was 89.48 (SD=7.43) and the majority was female (N=561, 71%) and white (N=771, 97%). As shown in Table 5, at 12 months the intervention group showed less decline in function than those in the control group (the control group declined 9 points and the treatment group declined 2.1 points, p<.001). There was also a significant improvement in percentage of function focused care behaviors performed by residents in the treatment group at four months increasing from 77% (SD=17%) to 81% (SD=18%) of activities while the control group decreased in performance of function focused care from 82% (SD=15%) to 81% (SD=16%), p=.012. At 12 months the treatment group remained at the improved 81% (SD=14%) of function focused care activities and the control group declined to 79% (SD=18%), p=.001. Actigraphy findings did not support the effectiveness of the intervention. At baseline the intervention group had significantly higher levels of activity than those in control and the control group consistently increased over time more than those in the treatment group. With regard to sedentary activity, residents in the intervention group increased minutes of sedentary activities from baseline to four months while the control group showed a small decline (p=.017). There was no noted differences between groups from baseline to 12 months in time spent in sedentary activity (p=.074).

Table 4.

Baseline Description of Residents (N=781)

| Variable | Mean | Std. Deviation |

| Age | 89.48 | 7.43 |

| Comorbidities | 5.08 | 1.95 |

| Three Out of Three Recall Item on the MiniCog | 2.39 | .76 |

| N | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 233 | 29% |

| Female | 561 | 71% |

| Race | ||

| White | 771 | 97% |

| Black | 23 | 3% |

| Word Recall | ||

| One out of three recall | 137 | 17% |

| Two out of three recall | 214 | 27% |

| Three out of three recall | 443 | 56% |

Table 5.

Resident Outcomes at Baseline, 4 and 12 Months Post Intervention and Effectiveness Between Treatment (FFC-AL-EIT) and Control (FFC-AL-Education Only) over Time

| Outcomes | Baseline Mean (SD) | Month 4 Mean (SD) | Month 12 Mean (SD) | Effects baseline to M4 (p-value) | Effects baseline to M12 (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function (Barthel Index) | 0.963 | 0.001 | |||

| Control | 82.6 (22.4) | 83.1 (21.5) | 73.6 (24.0) | ||

| Intervention | 80.2 (21.2) | 81.1 (21.3) | 78.1 (22.5) | ||

| Counts of Activity | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Control | 102833 (85797) | 117503 (99815) | 124962 (120504) | ||

| Intervention | 147701 (118186) | 106126 (83489) | 132784 (115050) | ||

| Minutes in Sedentary Activity | 0.017 | 0.074 | |||

| Control | 1235(188) | 1228(216) | 1203(237) | ||

| Intervention | 1177(190) | 1237(195) | 1173(245) | ||

| Minutes in Moderate Activity | 0.053† | <0.001 † | |||

| Control | 35.0(61.5) | 38.4(68.3) | 41.3(79.3) | ||

| Intervention | 69.4(95.9) | 36.5(58.7) | 55.6(82.8) | ||

| Minutes in Vigorous Activity | <.001† | 0.001 † | |||

| Control | 5.7(14.9) | 10.8(44.9) | 9.5(31.3) | ||

| Intervention | 16.6(33.8) | 6.9(22.3) | 12.6(29.9) | ||

| Percent Function Focused Care | 0.012 | 0.001 | |||

| Control | 0.82 (0.15) | 0.81 (0.18) | 0.79 (0.18) | ||

| Intervention | 0.77 (0.17) | 0.81 (0.16) | 0.81 (0.14) | ||

| Service Plans | 0.102 | 0.413 | |||

| Control | 2.16(1.59) | 1.93(1.62) | 2.55(1.47) | ||

| Intervention | 1.91(1.65) | 1.86(1.55) | 2.06(1.59) |

Note: p-values were from the group-by-time interaction term

: based on log transformed data

Evidence of adoption was supported based on participation of 85 out of the 90 sites in the first stakeholder meeting (94%), and a mean rate of participation in 10.00 (SD=2.00) out of a possible 11 additional stakeholder meetings. A total of 30 (57%) sites participated in the full additional 11 meetings, 6 (11%) participated in an additional 10 meetings, 7 (13%) participated in an additional 9 meetings and the remaining 5 sites (9%) participated in an additional 8 or fewer meetings (1 site participated in 3 meetings). Thirty seven out of the 48 treatment sites (77%) engaged in the study activities to achieve their goals as expected or more than expected. Based on observations of the direct care workers, there was an increase in adoption and use of function focused care interventions in the treatment sites from 63% at baseline to 68% at four months and 90% at 12 months.

There was evidence of implementation (i.e., treatment fidelity) based on delivery with a mean total of 11.00 (SD = 2.13) stakeholder meetings delivered to each treatment site. All treatment and control facilities were exposed to education, which included 965 staff. There was evidence of receipt of knowledge of function focused with an overall mean of 88% correct, 89% in the treatment groups and 86% in the control groups, on the Knowledge of Function Focused Care test. Policy and environment assessments were done in all the FFC-AL-EIT settings and interventions were implemented as appropriate to change environments and policies. All aspects of mentoring and motivation activities were provided by the interventionists (e.g., observation of caregivers; weekly Tidbits were provided and posted on the Functionfocusedcare.org webpage). Maintenance in the treatment groups was demonstrated based on maintaining a mean environment assessment score of 16.55 (SD=1.40) at 18 months (F=.95, p=.35) and a policy assessment score maintained at 11.66 (SD=3.06) at 18 months (F=1.20, p=.28). This suggested ongoing support for function focused care activities.

Discussion

The findings from this study provide support for implementation of function focused care into assisted living using the Evidence Integration Triangle. The three components of this framework that facilitated implementation included: (1) the use of an established four step approach for integrating function focused care; (2) the ongoing engagement of a stakeholder team to adapt the four steps into the setting and to identify and work on setting specific goals; and (3) the use of practical measures. In addition to the Evidence Integration Triangle there are other theories to facilitate dissemination and implementation of evidence based approaches to care including the Precede/Proceed model 32, Diffusion of Innovation theory 33, Greenhalgh’s framework 34, the ADAPTS (Assessment, Deliverables, Activate, Pre-training, Training, Sustainability) model 35 and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) 36, among others. In contrast to the Evidence Integration Triangle, these models are more complex and more difficult to implement and be understood by stakeholders in real world long term care settings.

There was evidence of engagement of the stakeholders and that the four steps of FFC-AL-EIT were delivered and received and that the settings adopted and integrated function focused care into daily care interactions. Evidence of implementation is of little value without simultaneous evidence of effectiveness37 which was likewise supported based on facility and resident outcomes. Changes in the environment and policy are important to establishing the infrastructure needed to engage residents in physical activity 38,39. The value of changing environments and policies and impact it has on function, physical activity and falls has been reinforced by the pandemic. There have been reports of a decrease in physical activity and an increase in falls in long term care environments due to restrictions related to Coronavirus 23,40. Future research will need to focus on engaging residents in physical activity while maintaining safe distancing and other infection precautions. Effectiveness at the resident level was based on less functional decline in treatment group residents versus control. The difference of a 7 point decline between treatment groups is clinically significant in that it could assure that the resident was able to perform an activity with minimal assistance versus being totally dependent. This can impact quality of life and caregiving needs 41,42.

Effectiveness of resident outcomes related to physical activity based on actigraphy was not supported in this study. Using cut off scores established for older adults43 the participants engaged in more than the recommended 30 minutes daily of moderate level physical activity and approximately 6 to 17 minutes of vigorous physical activity daily. This is much higher than is generally seen in assisted living residents when using the more conservative cut off scores established by other investigators 44–46 and when using devices placed on the waist or ankle versus the wrist 44–47. Moreover, the treatment group had higher levels of physical activity at baseline than the control sites and thus less likelihood of increasing these levels when compared to the control group. Based on prior research 47 a cut off of at least 1,000 counts per day was used as evidence of wearing the MotionWatch 8 for the full day. Diary reports related to wear time were not obtained and therefore it is impossible to know for sure if the MotionWatch 8 was worn for the full 24 hours. Further, there was a large percentage of missing data (29% at baseline; 32% at 4 months, and 47% at 12 months). Future use of the MotionWatch 8 should include a diary for wear time and periods in which the MotionWatch 8 may have been removed, utilize individualized cut off scores for physical activity 48, and allow for more flexibility for when the MotionWatch 8 is initially placed on the residents to decrease missing data.

Adoption of the intervention was based on evidence that the settings participated in the intervention activities. Rates of participation in this study were higher than have been reported in prior interventions implemented in nursing homes or community settings 49–51. Further other implementation studies done in nursing homes not only had lower adoption rates but also had no evidence of effectiveness 49.

Maintenance of any intervention is challenging to evaluate in assisted living as turnover of staff is approximately 50% 52 and the length of stay of residents is approximate two years 53,54. The findings from this study suggest that at least environments and policies supporting function focused care remained in place for up to 18 months post implementation of the intervention. Although not considered a priori as a measure of maintenance, all of the settings requested to continue to receive the weekly Tidbits and participated in contests provided through the Tidbits even after the 12 month intervention period.

Study Strengths and Limitations

This study was limited in that the sample was homogeneous including mostly white women from just three states and there may have been some bias in recruitment based on interest in engaging in physical activity. There were many contextual factors that would have helped to more accurately evaluate RE-AIM outcomes such as the total number of staff in settings, staff turnover, state survey issues during the study, or differences across sites related to payment (e.g., the amount of personal care covered by monthly rent versus additional costs for such care). Future work would benefit from gaining a better understanding of these factors. We deliberately did not recruit direct care workers as the intention of this implementation work was to engage all staff in providing function focused care to all residents. Consequently, there is no demographic or work related data about the direct care workers. As with other pragmatic trials, we deliberately limited the number of outcomes and did not measure additional aspects of function or physical activity among residents (e.g., the six minute walk).

Conclusion and Implications

Despite limitations, this study provides some value for the use of the Evidence Integration Triangle to help implement function focused care into assisted living settings and engage residents in function and physical activity. Evaluation of implementation is challenging and needs to be specific to the intervention being implemented. Future implementation research should focus on practical and innovative ways in which to comprehensively address Reach, Adoption and Maintenance components of RE-AIM which are generally not comprehensively or accurately addressed.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Flow of Subjects Through Dissemination and Implementation of FFC for AL

Acknowledgements:

We thank the many research evaluators and Nurse Research Facilitators for their dedication to this study and the residents and settings that worked with us.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Aging (Grant R01AG050516).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Barbara Resnick, University of Maryland School of Nursing, 655 West Lombard St, Baltimore MD 21218.

Marie Boltz, Pennsylvania State University, College of Nursing, 306 Nursing Sciences Building, University Park, PA 16802.

Elizabeth Galik, University of Maryland School of Nursing, 655 West Lombard St, Baltimore MD 21218.

Steven Fix, University of Maryland School of Nursing, 655 West Lombard St, Baltimore MD 21218.

Sarah Holmes, University of Maryland, Baltimore, Lamy Center.

Shijun Zhu, University of Maryland School of Nursing, 655 West Lombard St, Baltimore MD 21218.

Eric Barr, University of Maryland School of Nursing, 655 West Lombard St, Baltimore MD 21218.

References

- 1.Resnick B, Galik E, Gruber-Baldini A, Zimmerman S. Perceptions and Performance of Function and Physical Activity in AL Communities. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2010;11(6):406–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Król-Zielińska M, Kusy K, Zieliński J, Osiński W. Physical activity and functional fitness in institutionalized vs. independently living elderly: A comparison of 70–80-year-old city-dwellers. Archives of Gerontology & Geriatrics. 2011;53(1):e10–e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung G Understanding nursing home worker conceptualizations about good care. The Gerontologist. 2013; 53(2): 246–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Resnick B, Galik E. Impact of care settings on residents’ functional and psychosocial status, physical activity and adverse events. International Journal of Older People Nursing. 2015; 10 (4), 273–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Resnick B, Boltz M, Galik E, et al. The Impact of function focused care and physical activity on falls in assisted living residents. The Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benjamin K, Edwards N, Caswell W. Factors influencing the physical activity of older adults in long term care: Administrators perspectives. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2009;17(2):181–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buttery A, Martin F. Knowledge, attitudes and intentions about participation in physical activity of older post acute hospital inpatients. Physiotherapy.2009;95(3):192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Resnick B, Galik E, Boltz M, Pretzer-Aboff I, eds. Implementing Restorative Care Nursing in All Setting, 2nd Edition. 2011. Springer. New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonanni DR, Devers G, Dezzi K, et al. A Dedicated approach to restorative nursing. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2009;35(1):37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S, Kim M, Jung Y, Chang S. The Effectiveness of Function-Focused Care Interventions in nursing homes: A systematic review. The Journal of Nursing Research 2020;27(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galik EM, Resnick B, Gruber-Baldini A, Nahm ES, Pearson K, Pretzer-Aboff I. Pilot testing of the restorative care intervention for the cognitively impaired. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2008;9(7):516–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wells KL, Dawson P, Sidani S. Effects of an abilities focused program of morning care residents who have dementia and on caregivers. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2000;48(442–449). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dharmarajan T, Choi H, Hossain N, et al. Deprescribing as a clinical improvement focus. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2020;21(3):355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Resnick B, Galik E, Vigne E. Translation of Function Focused Care to assisted living facilities. Family and Community Health. 2014;37(2):101–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green L, Richard L, Potvin L. Ecological foundations of health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1996;10:270–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandura A Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. 1997. W.H. Freeman and Company. New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glasgow R, Green L, Taylor M, Stange K. An evidence integration traingle for aligning science with poliy and practice. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;42:646–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazenby M The international endorsement of US Distress Screening and Psychosocial Guidelines in Oncology: A model for dissemination. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2014;12:221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irvine A, Billow M, McMahon E, Eberhage M, Seeley J, Bourgeois M. Mental illness training on the Internet for nurse aides: A replication study. Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing. 2013;20(10):902–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang S, Gamaldo A, Neupert S, Allaire J. Predicting control beliefs in older adults: A micro-longitudinal study. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences. 2020;75(5):e1–e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Resnick B, Galik E, Gruber-Baldini A, Zimmerman S. Testing the impact of Function Focused Care in Assisted Living. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011;59(12):2233–2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Resnick B, Galik E, Boltz M, et al. Psychometric testing of the Function Focused Environment Assessment and the Function Focused Policy Assessment in Assisted Living. Journal of Housing for the Elderly. 2019;33(2):153–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Resnick B, Galik E, Boltz M, et al. Reliability and validity of the Checklist for Function Focused Care in Service Plans. Clinical Nursing Research. 2020;29(1):21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borson S, Scanlan J, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: Validation in a population-based sample. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51:1451–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linn B, Linn M, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1968;16(5):622–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahoney F, Barthel D. Functional evaluation: The Barthel Index. Maryland State Medical Journal. 1965;14(2):61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Resnick B, Boltz M, Galik E, Fix S, Zhu S. Feasibility, reliability and validity of the motionwatch 8 to evaluate physical activity among older adults in assisted living settings with and without cognitive impairment. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Resnick Simpson M. Restorative care nursing activities: Pilot testing self efficacy and outcome expectation measures. Geriatric Nursing. 2003;24(2):83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Resnick B, Boltz M, Galik E. Reliability and validity of the Function Focused Care Checklist for Caregivers Measure. Manuscript submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Resnick B, Simpson M, Bercovitz A, Galik E, Gruber-Baldini A, Zimmerman S, Magaziner J. Testing of the Res-Care pilot intervention: Impact on nursing assistants. Geriatric Nursing. 2004; 25(5): 292–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Resnick B, Rogers V, Galik B, Aboff I, Gruber-Baldini A. Reliability and validity of Knowledge and Self-efficacy and Outcome Expectation for Restorative Care Activities Measures. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2008;23(2):162–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green L, Kreuter M, Deeds S, Partridge K. Health education planning: A diagnostic approach (1st ed). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogers E Diffusion of Innovations, 5th Edition. New York: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, MacFarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review of recommendations. Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82:581–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knapp H, Anaya H. Implementation science in the real world: A streamlined model. Journal of Healthcare Quality. 2012;34(6):27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Damschroder L, Aron D, Keith R, Kirsh S, Alexander J, Lowery J. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4(1):50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementaiton research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adminstration Policy and Mental Health. 2011;38:65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phillips L, Petroski G, Conn V, et al. Exploring path models of disablement in residential care and assisted living residents. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2018;37(12):1490–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holmes S, Galik E, Resnick B. Factors that influence physical activity among residents in assisted living. Journal of Housing for the Elderly. 2017;60(2):120–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christey G, Amey J, Campbell A, Smith A. Variation in volumes and characteristics of trauma patients admitted to a level one trauma centre during national level 4 lockdown for COVID-19 in New Zealand. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2020;133(1513):81–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naylor M, Hirschman K, Hanlon A, et al. Factors associated with changes in perceived quality of life among elderly recipients of long-term services and supports. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2016;17(1):44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.LaCroix A, Bellettiere J, Rillamas-Sun E, et al. Nutrition, obesity, and exercise association of light physical activity measured by accelerometry and incidence of coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease in older women. Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open. 2019;2(3):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Landry G, Falck R, Beets M, Liu-Ambrose T. Measuring physical activity in older adults: Calibrating cut-points for the MotionWatch 8((c)). Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2015;7–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Medical Science Sports and Exercise. 1998;30(5):777–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Troiano R, Berrigan D, Dodd K, Masse L, Tilert T, McDoweell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Medical Science Sports and Exercise.2008;40(1):181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corcoran M, Chuf K, white D, et al. Accelerometer assessment of physical activity and its association with physical function in older adults residing at assisted care facilities. Journal of Nutrition Health and Aging 2016;20(7):752–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chakravarthy A, Resnick B. Reliability and validity testing of the MotionWatch 8 in older adults. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2017;25(3):7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.CamNtech. MotionWatch 8 Overview. Retrieved from https://www.camntech.com/products/motionwatch/motionwatch-8-overview. Last accessed August, 2020.

- 49.Lichtwarck B, Selbaek G, Kirkevold Ø, Rokstad A, Benth J, Bergh S. TIME to reduce agitation in persons with dementia in nursing homes. A process evaluation of a complex intervention. BMC Health Services Research. 2019;19(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santos S, Tagai E, Scheirer M, et al. Adoption, reach, and implementation of a cancer education intervention in African American churches. Implementation Science. 2017;12:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Folta S, Seguin R, Chui K, et al. National dissemination of StrongWomen-Healthy Hearts: A community-based program to reduce risk of cardiovascular disease among midlife and older women. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(12):2578–2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chou R Resident-centered job satisfaction and turnover intent among direct care workers in assisted living:a mixed-methods study. Research on Aging. 2012;34(3):337–364. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hyde J, Perez R, Doyle P, Forester B, Whitfield T. The impact of enhanced programming on aging in place for people with dementia in assisted living. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias. 2015;30(8):733–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caffrey C, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Moss A, Rosenoff E, Harris-Kojetin L. Residents living in reidential care facilities: United States, 2010 National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No. 91, pp1–6. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gaglio B, Shoup J, Glasgow R. The RE-AIM Framwork: A systematic review of use over time. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103 (6):e38–e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.